Effects of High Temperature and Water Re-Curing on the Flexural Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Steel–Basalt Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Design and Curing

2.3. Heating Process and Testing Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. UPV and Damage Degree (DD)

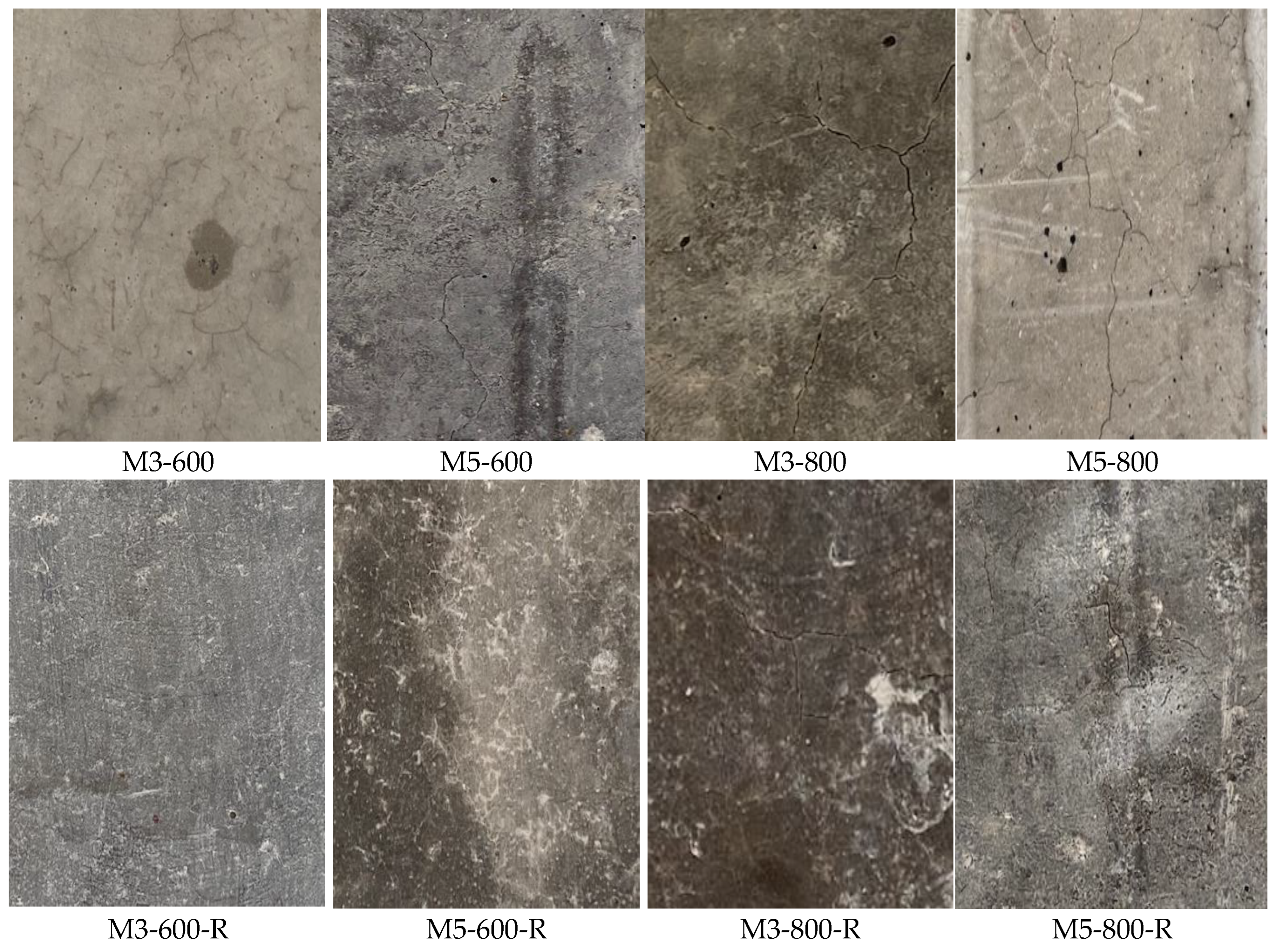

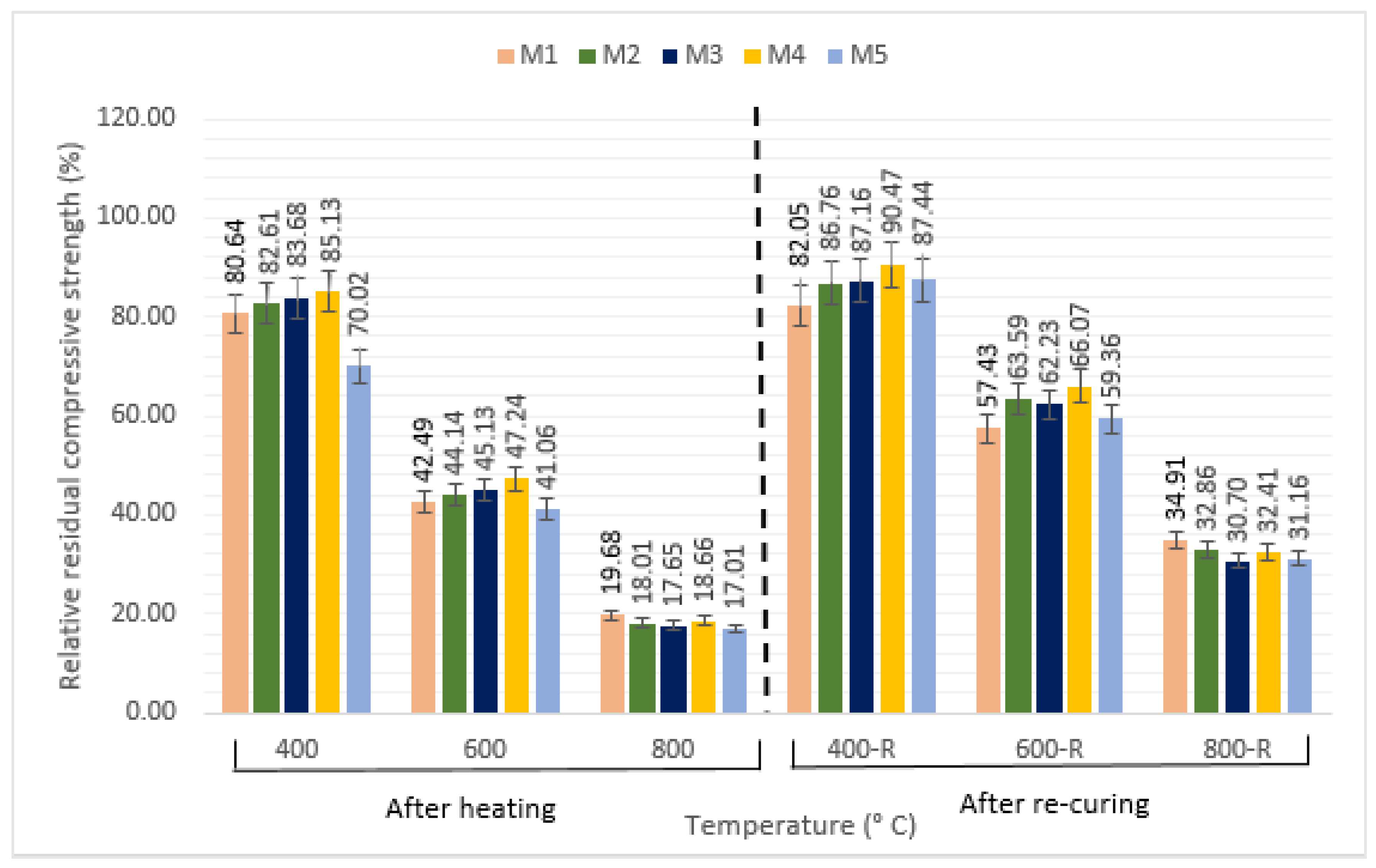

3.2. Compressive Strength

3.3. Flexural Strength

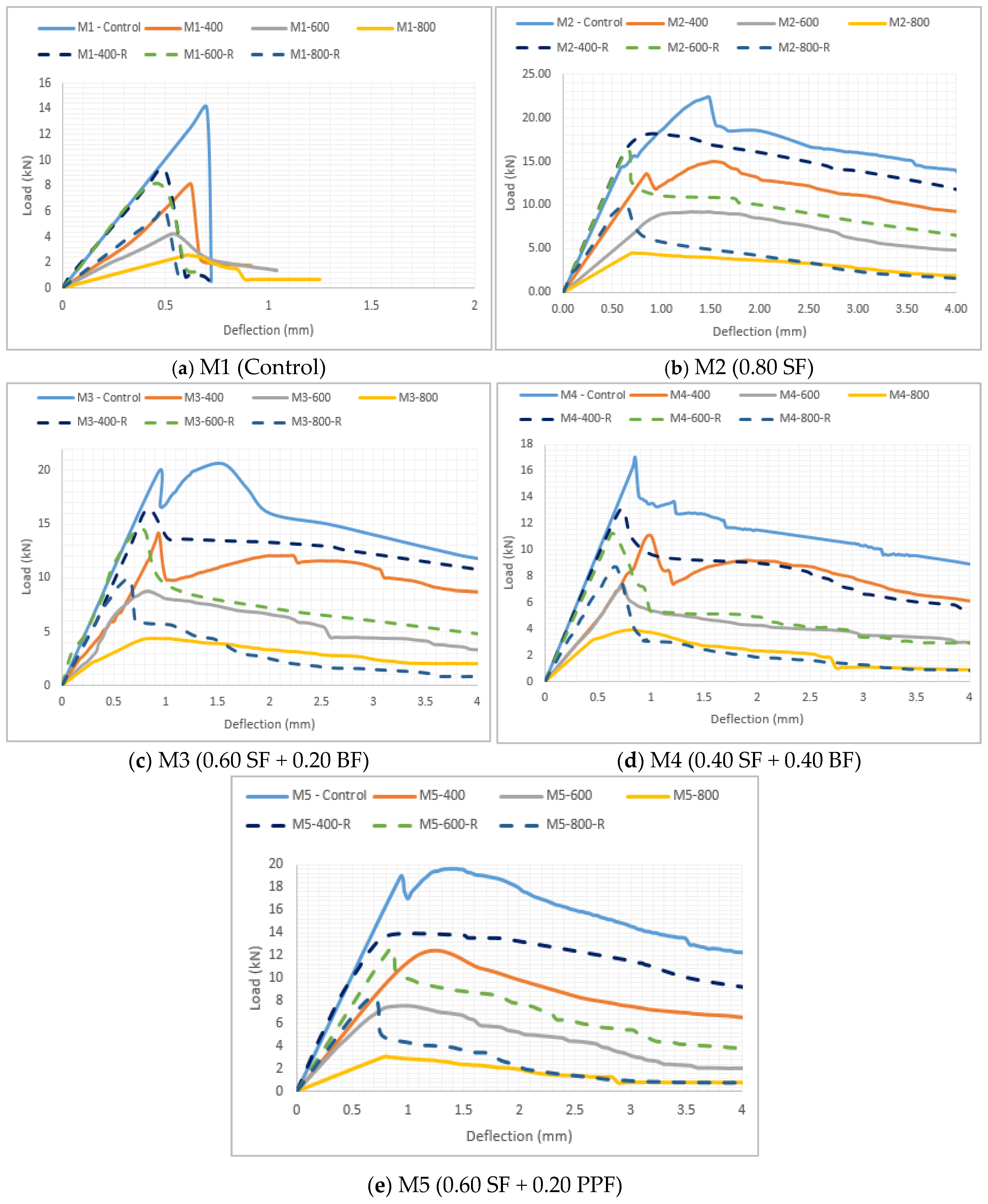

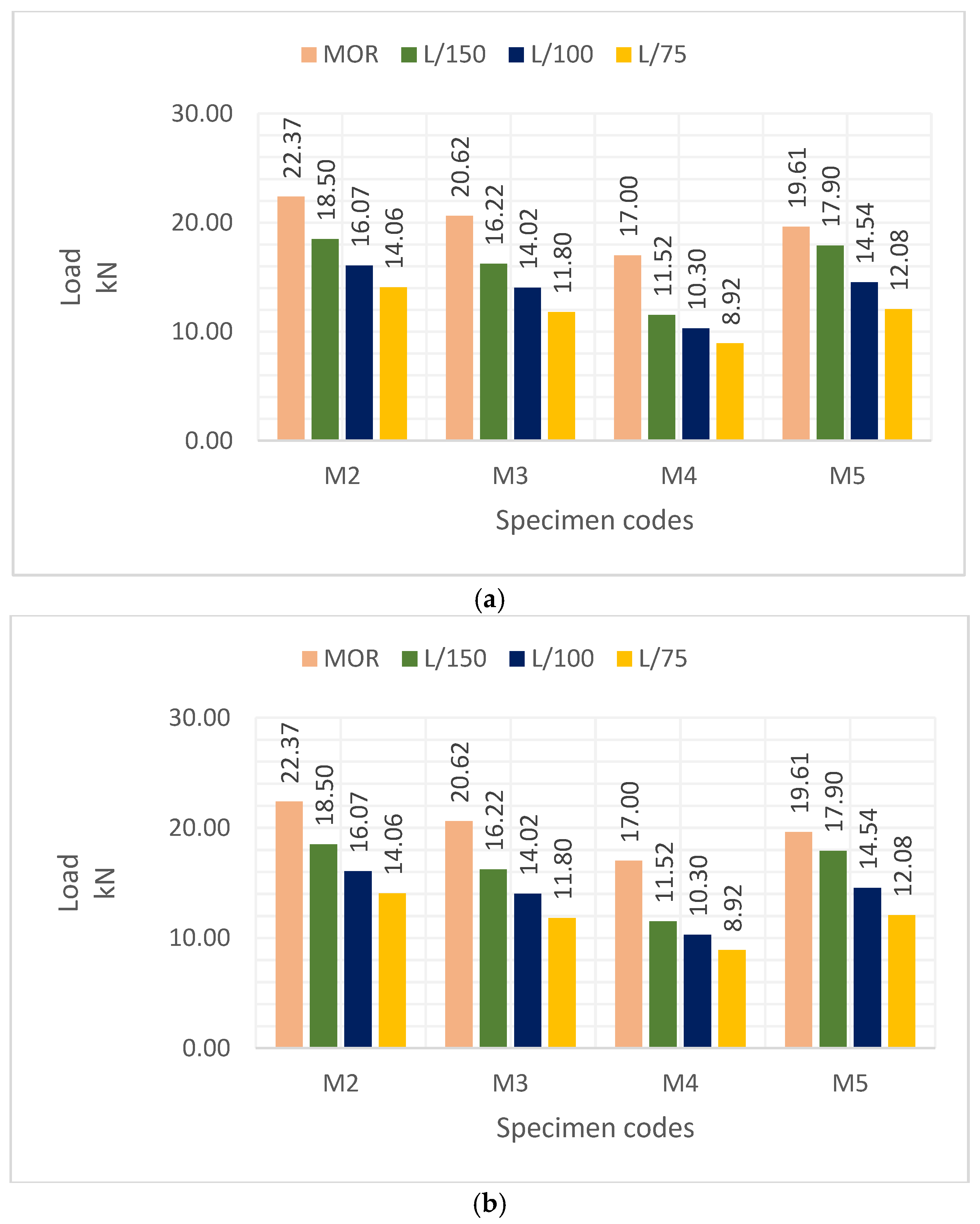

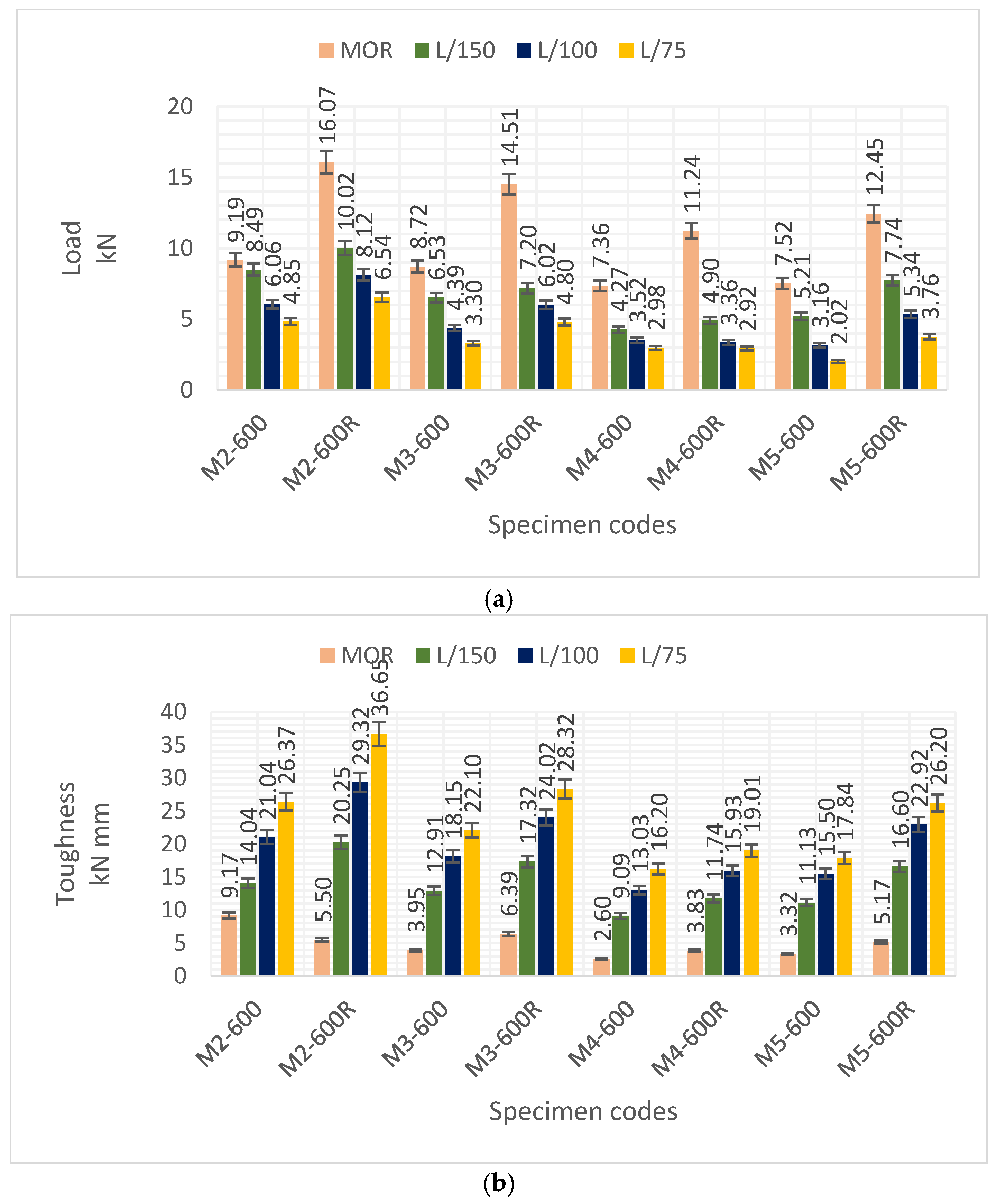

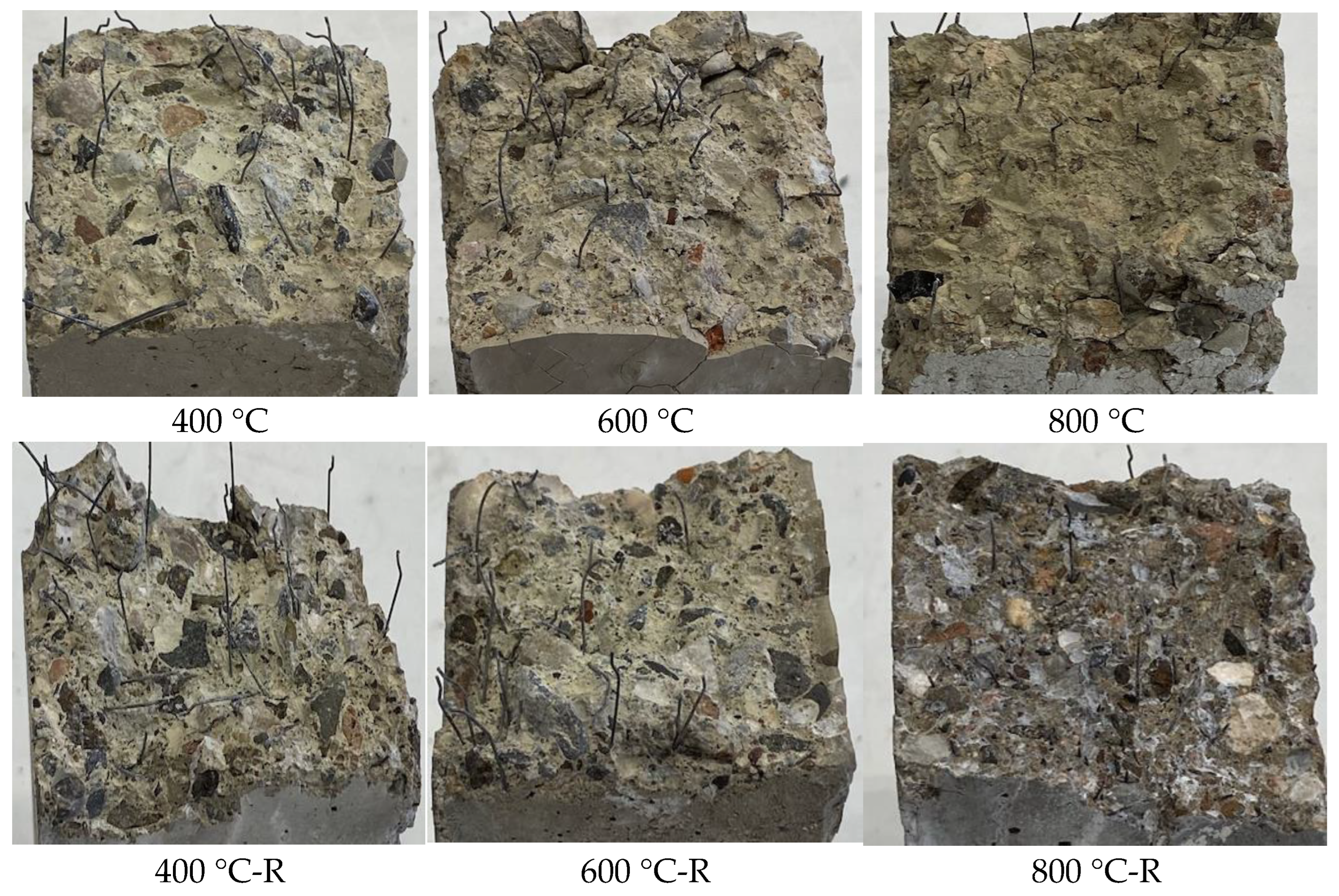

3.4. Flexural Behavior and Toughness

4. Conclusions

- At ambient temperature, fiber content slightly decreased the UPV values of the specimens compared to the reference mixture. As the specimens were exposed to temperature, remarkable decreases in the UPV results were observed, especially at 600 °C and above.

- An increase in compressive strength was obtained in all series except for the M4 mixture with 0.40% basalt fiber content at room temperature. This situation shows the negative effect of increasing basalt fiber content on compressive strength. The use of fibers caused significant improvements, especially in terms of flexural strength. Decreases in the strength of all series were observed with increasing temperatures. However, especially at temperatures above 600 °C, basalt fiber contributed to reducing the residual flexural strength loss. In mixtures where the same proportion of basalt and polypropylene fiber was used, basalt fiber gave better results in residual flexural strength.

- In contrast to flexural strength, polypropylene fiber gave better results than basalt fiber in terms of load carrying and toughness after the peak of the load–deflection curve at room temperature. This situation can be attributed to the weak response of basalt fiber specimens after peak load and fiber breakage.

- Water re-curing had a significant effect in recovering the performance of thermally damaged fibrous and non-fibrous concretes after heating. This recovery was especially evident at 600 °C and above.

- In terms of flexural strength, after exposure to 600 °C, the reference specimen reached 58.32% of its initial strength, while the M2 mixture reached 71.86%. These values were 30.11% and 41.08%, respectively, before re-curing. Re-curing after 800 °C brought the recovery rates of the mixtures closer to each other.

- Significant increases were obtained in the toughness properties of the specimens as a result of re-curing. However, although re-curing at temperatures of 600 °C and above caused a significant increase in the load carrying capacity at the MOR, there were sudden decreases in the load values at the L/100 and L/75 deflection points and even lower than the before-re-curing temperature at some points. This situation can be attributed to the fact that despite the improvement in the matrix, the fibers could not accommodate the sudden stress increase in the concrete due to the deterioration of the fibers at high temperatures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kodur, V.K.R.; Raut, N.K.; Mao, X.Y.; Khaliq, W. Simplified approach for evaluating residual strength of fire-exposed reinforced concrete columns. Mater. Struct. 2013, 46, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.E.; Awoyera, P.O.; Le, D.H.; Romero, L.B. A review of residual strength properties of normal and high strength concrete exposed to elevated temperatures: Impact of materials modification on behaviour of concrete composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 296, 123448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Shah SF, A.; Khushnood, R.A.; Baloch, W.L. Durability of sustainable concrete subjected to elevated temperature—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 199, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Lin, X.; Zhou, A. A review of mechanical properties of fibre reinforced concrete at elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 135, 106117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branston, J.; Das, S.; Kenno, S.Y.; Taylor, C. Mechanical behaviour of basalt fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.T.; Choi, J.I.; Koh, K.T.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, B.Y. Hybrid effects of steel fiber and microfiber on the tensile behavior of ultra-high performance concrete. Compos. Struct. 2016, 145, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhmirzaei, R.; Kodur, V.K.R. Modeling the response of ultra high performance fiber reinforced concrete beams. Procedia Eng. 2017, 210, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Z.; Bingöl, A.F. Fracture properties and impact resistance of self-compacting fiber reinforced concrete (SCFRC). Mater. Struct. 2020, 53, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, J. Residual strength of hybrid-fiber-reinforced high-strength concrete after exposure to high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.F.; Wang, Q.Y.; Guan, Z.W.; Chai, H.K. High-temperature behaviour of basalt fibre reinforced concrete made with recycled aggregates from earthquake waste. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choumanidis, D.; Badogiannis, E.; Nomikos, P.; Sofianos, A. The effect of different fibres on the flexural behaviour of concrete exposed to normal and elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 129, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukontasukkul, P.; Pomchiengpin, W.; Songpiriyakij, S. Post-crack (or post-peak) flexural response and toughness of fiber reinforced concrete after exposure to high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1967–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.M.A.; Lachemi, M.; Sammour, M.; Sonebi, M. Strength and fracture energy characteristics of self-consolidating concrete incorporating polyvinyl alcohol, steel and hybrid fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 45, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Biolzi, L.; Carvelli, V. Effects of elevated temperature and water re-curing on the compression behavior of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 67, 106034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Anson, M. Effect of high temperatures on high performance steel fibre reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1698–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhaendi, S.L.; Horiguchi, T. Effect of short fibers on residual permeability and mechanical properties of hybrid fibre reinforced high strength concrete after heat exposition. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1672–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agra, R.R.; Serafini, R.; de Figueiredo, A.D. Effect of high temperature on the mechanical properties of concrete reinforced with different fiber contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 301, 124242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanvitaya, P.; Chotickai, P. Effect of elevated temperature exposure on the flexural behavior of steel–polypropylene hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzal, S.K.; Al-Azzawi, Z.; Najim, K.B. Effect of discarded steel fibers on impact resistance, flexural toughness and fracture energy of high-strength self-compacting concrete exposed to elevated temperatures. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 121, 103271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.M.; Yang, H.; Lin, C.J.; Chen, J.F.; He, Y.H.; Zhang, H.Z. Fracture behaviour of steel fibre reinforced recycled aggregate concrete after exposure to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 128, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Liu, G.; Li, H.; Huang, Z. Mechanical properties and microstructures of Steel-basalt hybrid fibers reinforced Cement-based composites exposed to high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaskar, A.; Albidah, A.; Alqarni, A.S.; Alyousef, R.; Mohammadhosseini, H. Performance evaluation of high-strength concrete reinforced with basalt fibers exposed to elevated temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Xian, G.; Li, H. Effects of elevated temperatures on the mechanical properties of basalt fibers and BFRP plates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 127, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Han, F.; Wu, S.; Qin, Y.; Yuan, G.; Doh, J.H. Experimental study on durability of basalt fiber concrete after elevated temperature. Struct. Concr. 2022, 23, 682–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cai, Z.; Xie, Q.; Chai, X.; Yu, K.; Chen, W. Tensile behavior of high-performance hybrid steel-basalt fibers reinforced cementitious composites after high-temperature exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Cao, M.; Chaopeng, X.; Ali, M. Experimental and analytical study of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete prepared with basalt fiber under high temperature. Fire Mater. 2022, 46, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, G. A review on the recovery of fire-damaged concrete with post-fire-curing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lyu, H.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.; Tan, K.H. Effect of post-fire curing on compressive strength of ultra-high performance concrete and mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 346, 128447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Effect of post-fire curing and silica fume on permeability of ultra-high performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 290, 123175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhafs, F.; Ezziane, M.; Ayed, K.; Leklou, N.; Mouli, M. Effect of water re-curing on the physico-mechanical and microstructural properties of self-compacting concrete reinforced with steel fibers after exposure to high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 413, 134805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Azhar, S.; Anson, M.; Wong, Y.L. Strength and durability recovery of fire-damaged concrete after post-fire-curing. Cem. Concr. Res. 2001, 31, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akca, A.H.; Özyurt, N. Effects of re-curing on microstructure of concrete after high temperature exposure. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 168, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X.; Cao, M.; Lv, X.; Yin, H.; Li, L.; Liu, Z. Effects of high temperature and post-fire-curing on compressive strength and microstructure of calcium carbonate whisker-fly ash-cement system. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 244, 118333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, C.S.; Azhar, S. Deterioration and recovery of metakaolin blended concrete subjected to high temperature. Fire Technol. 2003, 39, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Biolzi, L.; Carvelli, V. Effects of elevated temperature and water re-curing on fracture process of hybrid fiber reinforced concretes. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 276, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C143-12; Standard test method for slump of hydraulic-cement concrete. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012.

- Jiang, C.; Fan, K.; Wu, F.; Chen, D. Experimental study on the mechanical properties and microstructure of chopped basalt fibre reinforced concrete. Mater. Des. 2014, 58, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C 597; Standard test method for pulse velocity through concrete. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016.

- Knab, L.I.; Blessing, G.V.; Clifton, J.R. Laboratory evaluation of ultrasonics for crack detection in concrete. J. Proc. 1983, 80, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- BS EN, 12390–12393; Testing hardened concrete. Compressive strength of test specimens. British Standard Institution: London, UK, 2009.

- ASTM C1609; Standard test method for flexural performance of fiber reinforced concrete (using beam with third-point loading). American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011.

- Nematzadeh, M.; Tayebi, M.; Samadvand, H. Prediction of ultrasonic pulse velocity in steel fiber-reinforced concrete containing nylon granule and natural zeolite after exposure to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Moura, M.A.; Leal, C.E.F.; Júnior, A.L.M.; dos Santos Ferreira, G.C.; Parsekian, G.A. Post-fire prediction of residual compressive strength of mortars using ultrasonic testing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 416, 135273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpalaskas, A.C.; Kytinou, V.K.; Zapris, A.G.; Matikas, T.E. Optimizing building rehabilitation through nondestructive evaluation of fire-damaged steel-fiber-reinforced concrete. Sensors 2024, 24, 5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, F.; Kocabeyoglu, E.T.; Gencel, O.; Benli, A. The effects of high temperature and cooling regimes on the mechanical and durability properties of basalt fiber reinforced mortars with silica fume. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 121, 104107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boğa, A.R.; Karakurt, C.; Şenol, A.F. The effect of elevated temperature on the properties of SCC’s produced with different types of fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 340, 127803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savva, A.; Manita, P.; Sideris, K.K. Influence of elevated temperatures on the mechanical properties of blended cement concretes prepared with limestone and siliceous aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrmomtazi, A.; Gashti, S.H.; Tahmouresi, B. Residual strength and microstructure of fiber reinforced self-compacting concrete exposed to high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 116969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afroughsabet, V.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Mechanical and durability properties of high-strength concrete containing steel and polypropylene fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Sun, W.; Chen, H. The effect of silica fume and steel fiber on the dynamic mechanical performance of high-strength concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ju, Y.; Shen, H.; Xu, L. Mechanical properties of high performance concrete reinforced with basalt fiber and polypropylene fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhuge, Y.; Huang, Z. Properties of hybrid basalt-polypropylene fiber reinforced mortar at different temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 346, 128433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, Z.; Bingöl, A.F. Effect of basalt, polypropylene and macro-synthetic fibres on workability and mechanical properties of self-compacting concrete. Chall. J. Struct. Mech 2019, 5, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Geng, S.; Mao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X. Investigation on cracking resistance mechanism of basalt-polypropylene fiber reinforced concrete based on SEM test. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Guo, R.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, Z.; He, K. Mechanical properties of concrete at high temperature—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.F.; Yang, W.W.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Bian, S.H.; Zhao, L.H. Explosive spalling and residual mechanical properties of fiber-toughened high-performance concrete subjected to high temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 723–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Lee, T.G.; Kim, G.Y. An experimental study on the residual mechanical properties of fiber reinforced concrete with high temperature and load. Mater. Struct. 2013, 46, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, G.F.; Huang, Z.S. Change in microstructure of hardened cement paste subjected to elevated temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Yoon, Y.S.; Banthia, N. Predicting the post-cracking behavior of normal-and high-strength steel-fiber-reinforced concrete beams. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skazlić, M.; Bjegović, D. Toughness testing of ultra high performance fibre reinforced concrete. Mater. Struct. 2009, 42, 1025–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.Y.; Kang, S.T.; Yoon, Y.S. Enhancing the flexural performance of ultra-high-performance concrete using long steel fibers. Compos. Struct. 2016, 147, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Compositions | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | CaO | MgO | K2O | SO3 | LOI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.73 | 4.56 | 3.07 | 62.80 | 2.07 | 0.62 | 2.90 | 2.05 | |

| Physical properties | Specific gravity | Insoluble residue (%) | Fineness (cm2/g) | |||||

| 3.15 | 0.66 | 3450 | ||||||

| Steel Fiber (SF) | Basalt Fiber (BF) | Polypropylene Fiber (PPF) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length (mm) | 35 | 24 | 12 |

| Diameter (mm) | 0.55 | 0.009–0.023 | 0.018–0.020 |

| Density (g/cm3) | 7.85 | 2.60–2.80 | 0.91 |

| Tensile strength (MPa) | 1345 | 4840 | 350 |

| Modulus of elasticity (GPa) | 210 | 89 | 3.50 |

| Mixture Code | Cement (kg/m3) | W/C | Fine Agg. (kg/m3) | Coarse Agg. (kg/m3) | Super Plasticizer (kg/m3) | SF (%) | BF (%) | PPF (%) | Slump (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 450 | 0.42 | 934 | 754 | 6.75 | - | - | - | 150 |

| M2 | 8.00 | 0.80 | 140 | ||||||

| M3 | 8.75 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 125 | |||||

| M4 | 9.00 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 115 | |||||

| M5 | 9.00 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 110 |

| Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity (m/s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperatures | ||||

| Mixtures | 23 °C | 400 °C | 600 °C | 800 °C |

| M1 | 4717 | 4292 | 2840 | 1220 |

| M1-R | 4546 | 4357 | 2621 | |

| M2 | 4651 | 4288 | 2780 | 1377 |

| M2-R | 4511 | 4435 | 2508 | |

| M3 | 4648 | 4230 | 2745 | 1369 |

| M3-R | 4478 | 4348 | 2482 | |

| M4 | 4642 | 4167 | 2814 | 1315 |

| M4-R | 4458 | 4357 | 2434 | |

| M5 | 4608 | 4082 | 2690 | 1267 |

| M5-R | 4595 | 4445 | 2671 | |

| Compressive Strength (MPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperatures | ||||

| Mixtures | 23 °C | 400 °C | 600 °C | 800 °C |

| M1 | 52.53 | 42.36 | 21.54 | 10.34 |

| M1-R | 45.10 | 31.77 | 18.34 | |

| M2 | 59.52 | 49.17 | 26.27 | 10.72 |

| M2-R | 51.64 | 37.85 | 19.56 | |

| M3 | 57.79 | 48.36 | 26.08 | 10.20 |

| M3-R | 50.37 | 35.96 | 17.74 | |

| M4 | 51.44 | 43.79 | 24.30 | 9.60 |

| M4-R | 46.54 | 33.98 | 16.67 | |

| M5 | 54.84 | 38.40 | 22.52 | 9.33 |

| M5-R | 47.95 | 32.55 | 17.09 | |

| Flexural Strength (MPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperatures | ||||

| Mixtures | 23 °C | 400 °C | 600 °C | 800 °C |

| M1 | 6.34 | 3.61 | 1.91 | 1.18 |

| M1-R | 4.07 | 3.70 | 2.74 | |

| M2 | 10.07 | 6.75 | 4.14 | 2.02 |

| M2-R | 8.12 | 7.23 | 4.39 | |

| M3 | 9.28 | 6.34 | 3.92 | 1.97 |

| M3-R | 7.39 | 6.53 | 4.37 | |

| M4 | 7.65 | 4.99 | 3.31 | 1.79 |

| M4-R | 5.82 | 5.06 | 3.89 | |

| M5 | 8.82 | 4.97 | 3.38 | 1.36 |

| M5-R | 6.22 | 5.61 | 3.72 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çelik, Z.; Urtekin, Y. Effects of High Temperature and Water Re-Curing on the Flexural Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Steel–Basalt Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031587

Çelik Z, Urtekin Y. Effects of High Temperature and Water Re-Curing on the Flexural Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Steel–Basalt Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(3):1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031587

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇelik, Zinnur, and Yunus Urtekin. 2025. "Effects of High Temperature and Water Re-Curing on the Flexural Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Steel–Basalt Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete" Applied Sciences 15, no. 3: 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031587

APA StyleÇelik, Z., & Urtekin, Y. (2025). Effects of High Temperature and Water Re-Curing on the Flexural Behavior and Mechanical Properties of Steel–Basalt Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. Applied Sciences, 15(3), 1587. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15031587