Featured Application

This study integrates VR into special education, combines behavioral experiments and physiological responses, and explores the impact of VR teaching on students’ social skills.

Abstract

This study explored the effectiveness of VR-based social skills training for students with autism and typically developing students with social difficulties. Six autistic students and five typically developing students from upper elementary grades participated in the study. Participants were recruited based on their willingness to participate, ability to follow instructions, and absence of other significant learning or behavioral disorders. Five VR modules were developed, covering scenarios like classrooms, ticket booths, exhibitions, restaurants, and parks. These modules incorporated foundational social settings and more complex scenarios to enhance emotional regulation and adaptive responses, aligned with the 12-year Basic Education Curriculum Guidelines. The intervention took place from May to July 2023, with participants attending six 30–40 min VR sessions once or twice a week. Various assessment tools measured the impact, focusing on social responses, emotion recognition, and reactions to unexpected situations. Results indicated consistent improvements in conversation speed, expression effectiveness, and environmental adaptation. Social Skills Behavior Checklist scores showed significant differences between pre- and post-tests, while EEG data revealed enhanced empathetic responses among autistic students. Typically, developing students shifted from independent problem-solving to seeking social support. This study highlights the potential of VR as an effective tool for social skills development in both groups.

1. Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a lifelong, intricate neurodevelopmental condition that greatly affects a person’s ability to communicate both verbally and non-verbally, engage in social interactions, and exhibit typical behaviors. Individuals with ASD often show restricted interests and repetitive or unusual sensory-motor behaviors [1]. The estimated prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has risen over the years. A recent systematic review found that the median global prevalence is 100 per 10,000 people, with variations across different regions. Notably, ASD shows a significant gender disparity, with males being three times more likely to be affected than females [2]. According to the latest data from the Special Education Network of the Ministry of Education in Taiwan, the number of students with autism in Taiwan reached 25,929 in 2024, with the highest number at the elementary school level [3]. Therefore, it is crucial and meaningful to study autistic students aged 7 to 14.

1.1. Teaching and Application of Autism Through Virtual Reality (VR)

Numerous studies have indicated that VR is widely used in education, particularly in special education. Lorenzo et al. [4] have established an Emotional Script (ES) as a social script or behavior guideline in which they introduced ten social situations. These social situations are designed based on real situations where the students have shown difficulties. Parsons et al. [5] used a VR cafe with 12 adolescents with ASD between the ages of 13–18 to teach social awareness and then conducted a follow-up study with six adolescents between the ages of 14–15. Parsons et al. [6], through the VR cafe and bus scene, allowed two well-characterized autistic adolescents to practice in VR, including responding to emergencies, answering questions correctly, and complying with social norms. Didehbani et al. [7] conducted research on thirty children between the ages of 7–16 diagnosed with ASD by completing 10 one-hour sessions across five weeks. These preliminary findings suggest that the use of a VR platform offers an effective treatment option for improving social impairments commonly found in ASD. Matsentidou et al. [8] and Tzanavari et al. [9] hope to create a safe road space for children; therefore, they presented a scene of a road in VR, allowing children learn how to cross the road. DiGennaro Reed et al. [10] composed 40 articles on VR technology applications to improve the social skills of autistic patients. The findings can be divided into “social skills training format”, “training technology application”, and “experimental setting location”, which consisted of nine categories, eight types, and six areas. Horace et al. [11] trained 94 children between the ages of 6 and 12 by simulating six virtual scenes and related events, teaching emotional expression and control, and their interaction and emotional communication with others. It was found that after 28 weeks, children showed significant improvement and progress in emotional and human interaction.

1.2. The Advantages of Virtual Reality (VR) Teaching for Social Skills Training in Students with Autism

Virtual reality (VR) training has become an increasingly important tool for promoting social interaction and communication learning in students with autism [12]. Studies highlight its numerous benefits for special needs students, particularly in facilitating skill transfer from virtual environments to real-life interactions [13]. The effectiveness of immersive VR as a training tool stems from its ability to simulate real-world characteristics, incorporating seven key features: controllable input stimuli, modification for generalization, safer learning situations, a primarily visual/auditory world, individualized treatment, preferred computer interactions, and trackers [14]. These attributes make VR an effective method for improving both verbal and non-verbal communication skills while fostering social interaction.

Research has provided compelling evidence of VR training effectiveness. Manju et al. [15] conducted a study comparing a VR-based program to traditional methodologies such as Discrete Trials Instruction (DTI), Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), and Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBIs). Their findings confirmed that the VR program not only enhanced social interactions, but also improved communication and behavioral outcomes, demonstrating its superiority over conventional approaches.

Beyond general social interaction, VR-based interventions have also contributed to notable advancements in specific aspects of social behavior. Studies have reported improvements in emotion recognition, collaborative activities, and turn-taking skills among participants [16,17,18]. These interventions have proven effective in helping individuals understand and respond to social cues more naturally. Additionally, desktop VR systems have gained popularity due to their user-friendly interfaces and ability to provide accessible social skills training without specialized equipment [19,20]. These features make desktop VR systems an ideal, scalable, and flexible solution for autism education.

Overall, the growing body of research underscores the potential of VR in enhancing social skills and emotional intelligence in individuals with autism. By offering diverse tools and techniques, VR-based interventions continue to support social development, providing an immersive and structured learning environment that caters to individual needs.

1.2.1. Improvement in Self-Emotion Regulation and Emotional Communication

This study focuses on emotional regulation and communication as the primary improvement goals. The literature also clearly indicates that setting up virtual reality scenarios and incorporating instructional methods effectively enhance students’ emotional control and regulation abilities.

Emotional communication and interaction in students with autism can be trained through VR scenarios constructed using social stories. These scenarios simulate ten types of interaction difficulties that students might encounter, including the following: 1. Attending a birthday party, 2. Playing with some children in the park, 3. Waiting to enter the classroom daily, 4. Listening to the teacher’s lecture, 5. Approaching children who are playing soccer, 6. Cooperating with classmates to perform fieldwork, 7. Undergoing a physical examination, 8. Actively seeking protection and assistance, 9. Attempting to integrate with a group of children who are talking in the courtyard, 10. Asking for help during class [4].

1.2.2. Improvement in Cooperation Skills

Cooperative behavior is a specific type of social behavior that involves sharing goals, attention, and action plans (intentions) with others. Children with autism have a lower success rate in cooperative tasks compared to children with developmental delays and show fewer partner-oriented behaviors. Battocchi et al. studied the effect of using cooperative puzzle games to cultivate the cooperative skills of children with autism [21]. The results showed that enforced cooperation rules can effectively improve the cooperative abilities of typically developing children and significantly enhance the communication and coordination behaviors of children with autism. In 2017, Lindeman et al. [22] researched the use of activity schedules to improve the cooperative skills of children with autism.

1.2.3. Improvement in Empathetic Responses

Empathetic response is a critical aspect of social interaction, allowing individuals to understand and share the feelings of others. The research pointed out that most past research has used face-to-face (F2F-SST) interactions to enhance the social skills of students with autism and effectively improve empathy [23]. In recent years, social skills courses have been conducted using Behavioral Intervention Technologies (BITs-SST), and it was found that the learning outcomes of social skills did not significantly differ from those of traditional F2F-SST. This indicates that achieving face-to-face interaction effects through digital technology is similar to actual face-to-face interactions, both of which enhance social skills and empathetic responses.

Research has shown that these programs can significantly improve the empathetic behaviors of children with autism, helping them to better connect with their peers and improve their social relationships.

1.3. The Relationship Between Social Skills Training and Brain Waves

Currently, many studies have found a significant relationship between brain neurons and human social skills [24,25,26]. In particular, when autistic patients imitate others’ actions, the signal processing speed of their mirror neuron system is slower. Electroencephalography (EEG) examinations also found that when autism patients perform actions themselves, the mu rhythm, which represents the activation of the primary motor cortex, is similar to that of typical individuals. However, when observing others’ actions, the primary motor cortex activity of the mirror neuron system in autism patients is much weaker. This indicates that autism patients are less able to predict others’ imminent emotions or actions subconsciously, making it difficult for them to understand and judge others’ intentions, which is closely related to their social skill deficits. Regarding empathy, we usually experience a sense of empathy when we see others sad or happy, which is highly related to the aforementioned mirror neurons and mu rhythm [27]. However, autism patients show relatively weaker signals in this regard compared to typical individuals, suggesting potential difficulties in exhibiting empathy in social contexts.

Perry et al. also explored social interactions and the mu and alpha waves of the brain, identifying potential differences in the mirror motor system and perception-deep learning mechanisms. The findings support previous research hypotheses, namely, that more active participation in social games triggers greater mu wave responses. This explanation is consistent with past research results, which showed that in tasks involving social interactions between self and others [28] and understanding the anticipated movement direction of others, the mu wave response is greater [29].

In summary, most literature indicates that social skills and empathy have a significant relationship with the mirror neuron system and brain waves, specifically the mu and alpha waves. EEG measurements can also be applied in VR execution processes. Thus, to evaluate empathetic responses to pain in the context of VR system teaching effectiveness, the mu wave, from adjacent frequencies (±2 Hz), shows personalized maximum power at approximately 6–10 Hz for children and 8–12 Hz for adults. These data are obtained from the average values at electrode positions C3, Cz, and C4 [30].

2. Materials and Methods

In the first phase of this study, we will integrate the expertise from information technology and special education. We will set educational goals and strategies using VR technology based on its limitations and relevant literature. We will develop scripts for advanced application VR education systems, create scenario themes, and integrate educational goals through sub-scenarios. Additionally, we will develop system environments, create characters, and devise self-compiled scenario questionnaires.

In the second phase, we will recruit middle to upper-grade elementary school students, selecting six autistic students and five typical students, for a total of eleven students. Using a quasi-experimental mixed design method with pre- and post-tests for unequal groups, we will implement the social skills scenario courses in this teaching system and observe the student’s performance during the learning process and the changes in effectiveness from the pre-test to the post-test.

2.1. Research Tools

2.1.1. Virtual Reality (VR) Social Skills Course System

Primarily through the establishment of various scenarios and corresponding emotions, the VR teaching system allows autistic students to practice how to handle the emotional changes in characters in the scenario, think calmly, and even further resolve sudden situations. It provides opportunities for repeated practice, allowing students to try to face various events with the most appropriate attitudes and emotions and further generalize this improvement to their daily lives to address social difficulties. Additionally, this study strengthens social skills based on the subjects’ individual weaknesses and levels of social skills, aiming to enhance their social abilities.

This study developed the system scene according to the predetermined “Art Tour with Classmate”. Four scenarios were developed according to the original goal, including the 1st situation—Classroom: Pre-departure discussion with the class before the tour, 2nd situation—Exhibition: Arriving at the venue with the students to see the exhibition (including ticket booths, lighting exhibitions, and cultural relics exhibitions), 3rd situation—Restaurants: dining with the students in the restaurant (including Western restaurants and fast-food restaurants), 4th situation—Park: Saying goodbye to classmates and ending the journey. Each task will present unexpected situations according to the student’s learning progress, training the student’s ability to respond in real-time.

This experiment is guided by a simple picture book and relative activities to enter VR teaching. The general process includes 5 min for the course content, 10 min for the picture book, and 10 min for the formal activity before the VR situation. The VR teaching lasts for 10 min, and the classroom test takes 5 min. This article will illustrate the trigger mode and execution screen (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Explanation of the tasks and levels in the VR course.

2.1.2. Behavioral Experiment Materials

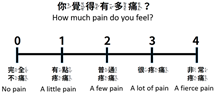

This section involves conducting pre- and post-tests on the students before and after the VR course to observe whether their social skills have improved or have been enhanced through the VR course. The materials collection and creation will be analyzed based on the items organized from the previous literature review, including the level of pain perception, emotion recognition, and responses to unexpected situations (communication and adaptability skills); see Table 2.

Table 2.

The situation pictures execution and level tasks.

2.2. Analysis Tools

2.2.1. Instruments and Equipment

- Electroencephalography (EEG)

This study uses Neuroscan experimental EEG recording equipment, a 64-conductor electrode cap (for SynAmps2), Quik-Cap 64 channels—Ag/AgCl Sintered (medium), Quik-Insert Electrode for Cap, Sintered, 1.5 m, Quik-Cap Kit, Hangdown electrode, Sintered, and an EEG amplifier. These devices are used to examine the changes in students’ brain waves before and after VR teaching. Empathy-related images are used as the primary EEG response materials, allowing participants to view facial expression/scenario images. The study observes changes in students’ brain wave patterns related to empathy before and after taking the VR course (pre- and post-test EEG responses).

- E-Prime 3.0 (Psychology Software Tools)

This software is used to record students’ response time when viewing image materials, which is then further analyzed in conjunction with their EEG responses. E-Prime is a stimulus presentation software designed specifically for psychological and behavioral research, widely used for experiment design, data collection, and analysis.

2.2.2. Questionnaires and Scales

- Elementary and Junior High School Students Social Skills Behavior Scale (version used by teachers)

The teachers of the school class fill this part. Before students participate in the virtual reality social course, their teacher needs to complete a pre-test assessment specifically for each student. The parents pass the scale to the teacher and remind the parents not to tell the teacher about society. For interactive courses, the second time to fill out the scale is after the students have completed 6 VR courses so that the teacher can score the social performance of the students in the school.

This scale was evaluated by a tutor familiar with the subject. There are 56 questions on the topic. The answers to each question include “always”, “often”, “sometimes”, “seldom”, and “never”. The five items are divided into one, two, three, four, and five points (the higher the score, the more frequent the behavior).

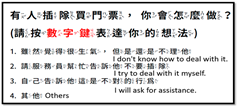

- Descriptive Statistics for Self-Developed Social Skills Performance Rating Scale

This study uses the “Descriptive Statistics for Self-Developed Social Skills Performance Rating Scale” (self-made sheet) to reflect the real situation at the time of the test and allows the case to fully demonstrate the ability at that time; the self-made social skills performance score sheet of this study is based on the familiar interpersonal communication 7/38/55 rule. The concept is proposed by Albert Mehrabian, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Total Liking = 7% Verbal Liking + 38% Vocal Liking + 55% Facial Liking”, which means that when you need to convey a message that is “good intentions, but the content may cause negative emotions to the listener”, you can use “sincere and positive attitudes” (reactive in tone, expression, and physical) to express favorable results for the listener; refer to Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Interpersonal communication concept proposed by Albert Mehrabian. Taken from http://wfhstudy.blogspot.tw/2013/01/blog-post_29.html (accessed on 8 February 2025).

The main scoring project in this study contains” Response Speed in Conversation”, “Effectiveness of Conversation Expression”, “Sentence Structure Integrity”, and “Conversation Etiquette”. The scoring method for each item is as follows:

- Response Speed in Conversation: The time needed for thinking and answering after the students hear the questions raised by the avatars. The time calculation starts from the time the avatar finishes asking the question and ends with the subject articulating the first word of his/her response. Five points in 0~3 s, four points in 3–5 s (more than 3 s, including 5 s), three points in 5–8 s (more than 5 s, including 8 s), and two points for more than 8 s. Those who did not answer the questions obtained one point. The faster the students answer, the higher their score.

- Effectiveness of Conversation Expression: This project includes volume control, the appropriateness of the tone, the manner of speaking, speaking speed, the expression of body language, etc.

- Sentence Structure Integrity: This project considers whether each sentence answered by the student contains a subject, a verb, an adjective, a noun, an adverb, or even an active invitation or courage to ask a question through a complete sentence. The basic score of this project is 3 points. If the structure of the sentence answered by the subject is more complete, he/she can obtain a higher score.

- Conversation Etiquette: There are five items in this section, including the participant’s attention during the dialogue process (eye focus/behavioral performance), whether the conversion process has been interrupted or given an irrelevant answer, meaningless vocabulary or soliloquizing in the conversation, reiteration of the answer, etc. If all five of the above projects have been performed well, the subject obtains five points. Poor performances in one of the items result in four points, three points for poor performances in two items, two points for poor performances in three items, and one point for poor performances in four or more items. If no response was made to any items, the subject also obtains one point for this project.

The Likert Scale scored all items in this study. This assessment form is filled in by the researcher (also the examiner). Since teaching style and personal teaching methods could easily affect the accuracy of the research process and results, all teaching was performed by one researcher. The researcher observed each student’s performance in six lessons and rated them on the same criteria.

- Social Skills Effectiveness Survey

The questionnaire is mainly based on the training objectives set in this study. The questionnaire is designed through the social skills curriculum in special education for 12 years. The content of the social skills course is divided into three aspects, including “accommodating with oneself”, “communicating with others”, “accommodating the environment”, and sorting out the first level as situation 1—discussing with the classmates before embarking on the trip, with the main instruction being courage to express and accept meaning; the second level is situation 2—helping classmates buy tickets and seeing the exhibition together with him, with the main training focused on learning to manage advance and retreat, and speaking at appropriate times; the third level is situation 3—with the classmates to the restaurant, with the main training being flow waiting and self-choice; the fourth level is situation 4—saying goodbye to the classmates and ending the journey, which is mainly to teach emotional management and situational transformation. The Likert Scale scored all items in this study. The choice is Strongly Disagree to obtain 1 point, Disagree to obtain 2 points, Neutral to obtain 3 points, Agree to obtain 4 points, or Strongly Agree to obtain 5 points; the answers are collected from the parents after the student completes the 6 weeks course. At this stage, the parents spend most of the time with the students. Therefore, the parents observe the students and assist in the completion of this questionnaire.

2.3. Participants

The main participants in this study were recruited through announcements and promotions on various online social networks, public and private schools, and early intervention service medical clinics. The participants include autistic students and typical students with social difficulties.

- Typical Students (TD): Must be identified by teachers or parents as having social difficulties at school or in daily life, and must pass the Autism Student Social Function Checklist (designed by [32] as a self-assessment scale for students with social function disorders).

- Autistic Students (ASD): 1. Diagnosed by public or private hospitals as having mild autism and possessing a disability certificate. 2. Identified and approved by the Special Education Student Identification and Placement Counseling Committee as autistic students. 3. The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) score must be 70 or above.

2.4. Experiment and Teaching Locations and Testing Times

Students’ participation in this study includes VR teaching and behavioral experiments before and after the tests. Additionally, parents and teachers will observe the students’ performance and assist in completing the pre-test and post-test questionnaires.

2.4.1. Virtual Reality Course

The teaching took place in the special education counseling room on the 5th floor of the administrative building at the National Tsing Hua University’s Nanda Campus. The space plan includes a table, chairs, a desktop computer (including the host, screen, and mouse), a set of head-mounted stereo display HTC VIVE, a set of controllers, a pair of base stations, a headset microphone, two digital videos, and a code table. Field personnel include a researcher, a camera operator, and a subject.

2.4.2. Behavioral Experiment and Electroencephalography (EEG) Testing

The experiment will take place at the EEG research laboratory on the 4th floor of the Administration Building, Nanda Campus, National Tsing Hua University.

2.4.3. Experiment Schedule

The experiment was conducted from May 2023 to July 2023, and the students completed six courses and pre-tests and post-tests for the behavioral experiment and EEG.

2.5. Statistics and Analysis Methods

This study conducted experiments with students with autism (6 individuals) and typical students with social difficulties (5 individuals), collecting a total sample size of 11. A quasi-experimental mixed design was used, employing a two-factor mixed design: social curriculum as the within-subject factor with pre-test and post-test levels, and student characteristics as the between-subject factor, divided into two levels: the autism group and the group of students with social difficulties. The study utilized five methods for statistical analysis, including the following:

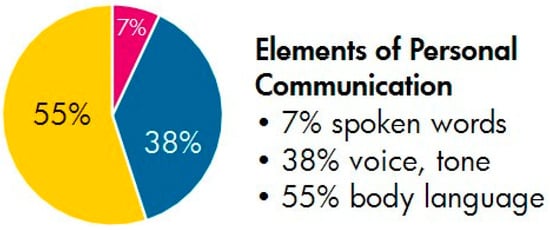

- Distribution of the Data and Test for Normality

This study utilizes the Normal Q-Q Plot, the Shapiro-Wilk test (which is suitable for small samples), and the widely used Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to ensure that the sampled participants’ test scores conform to a normal distribution.

- Descriptive Statistics

This is primarily used to analyze preliminary data from the “Social Skills Effectiveness Opinion Survey”, “Social Skills Performance Rating Scale”, and the “Social Skills Behavior Checklist for Elementary and Middle School Students (Teacher Version)”.

- Two-Way ANOVA (Mixed Design)

It's mainly used to clarify whether “this curriculum is suitable for typical students with social difficulties and students with autism”

- Paired Sample t-test

This test is primarily used to analyze the “Social Skills Behavior Checklist for Elementary and Middle School Students (Teacher Version)” and “Students’ EEG data output comparison”.

- Chi-Squared Test

This test is mainly used to analyze changes in students’ responses to unexpected situations in the “Behavioral Experiment of Unexpected Situations” between the pre-test and post-test.

- Wilcoxon Sign Rank

This analysis is used for the EEG experiment results. The final data analysis in this study was conducted using the EEG Analysis module in Matlab 2021b.

3. Results

This section will first explain the basic information of the subjects and further interpret the learning outcomes, behavioral responses, and EEG changes to present the most complete experimental results.

3.1. The Normal Distribution of Participants’ Test Results

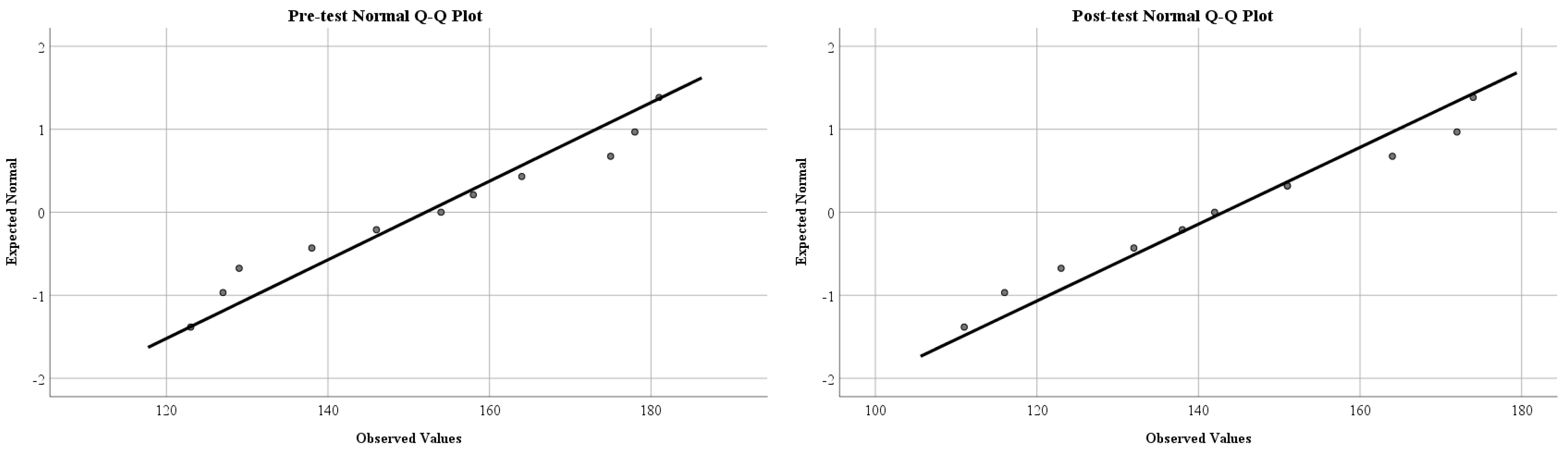

In the Shapiro-Wilk test, the p-value was greater than 0.05, with a pre-test value of 0.401. Therefore, it is reasonable to infer that the data do not significantly deviate from a normal distribution, meaning it meets the assumption of normality. Although the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test has lower sensitivity for small samples, it still indicates no significant deviation from a normal distribution, confirming normality (as shown in Table 3).

Table 3.

Normality test.

Additionally, the Normal Q-Q Plot from both the pre-test and post-test clearly shows that the data follow a normal distribution (as shown in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pre- and post-test normal Q-Q plot.

3.2. Basic Information of Virtual Reality (VR) Teaching Subjects

The main subjects of this study were recruited through announcements and promotions on various online social networking sites, public and private schools, and early intervention service medical clinics. The study recruited six students with autism and five typical students with social function difficulties. Detailed basic information of the subjects can be found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Basic information of participants.

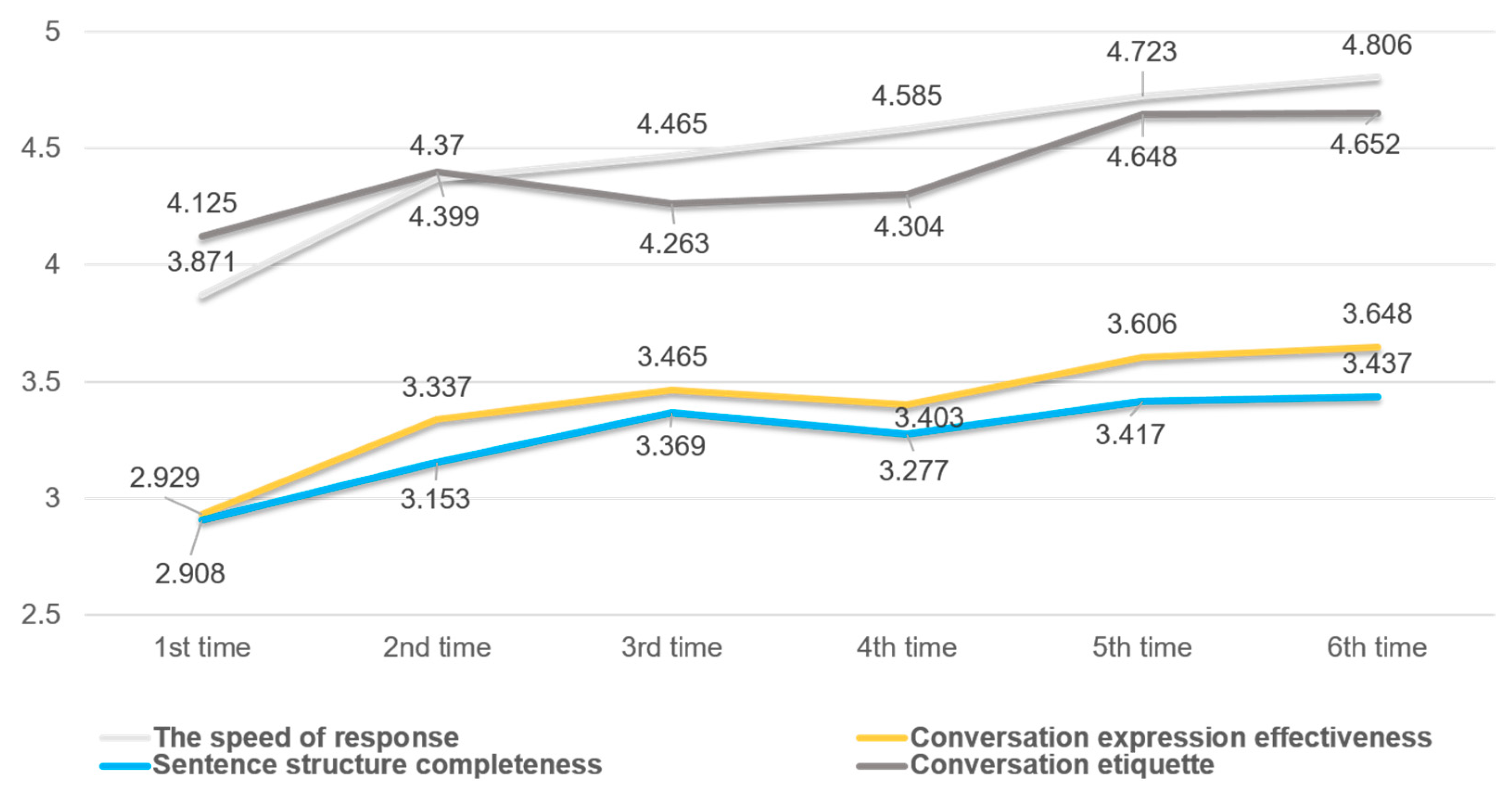

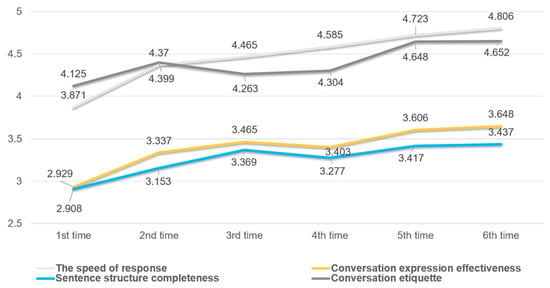

3.3. Descriptive Statistics for Self-Developed Social Skills Performance Rating Scale

In the Descriptive Statistics for the Self-Developed Social Skills Performance Rating Scale, we can observe that all students’ “response speed in conversation” and “effectiveness of conversation expression” have steadily increased over time. “Sentence Structure Integrity” slightly declined during the fourth lesson, and “Conversation Etiquette” regressed somewhat during the third lesson but gradually improved again (as shown in Table 5).

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for self-developed social skills performance rating scale in VR social skills advanced course (sessions 1–6).

3.4. Social Skills Effectiveness Survey

This section is filled out by parents to complete the Social Skills Effectiveness Survey, mainly observing the changes in students’ daily lives after receiving six sessions of VR teaching. This part is presented through descriptive statistics, indicating that parents perceive the greatest change in students to be in their ability to adapt to the environment, with an average score of 4.11. This shows that the students have significantly improved their adaptability to the environment in the VR course; see Table 6.

Table 6.

Social skills effectiveness survey (descriptive statistics).

3.5. Elementary and Junior High School Students Social Skills Behavior Scale (Version Used by Teachers)

The average scores for all students (without grouping) showed higher pre-test scores than post-test scores, with an average total score of 152 for the pre-test and 143 for the post-test. This indicates that school teachers believe that the inappropriate social behaviors of the autistic students have decreased after participating in the VR social skills program (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Comparison of pre- and post-test scores for elementary and junior high school students social skills behavior scale.

3.5.1. Paired Sample t-Test

Further examination of the t-test shows that there has been a significant improvement in the students’ inappropriate behaviors, with the overall effectiveness being significant, and the two-tailed t-test value being significant at 0.022 * (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Elementary and junior high school students social skills behavior scale t-test.

3.5.2. Two-Way ANOVA, Mixed Design

This analysis reveals that there is no score difference between the autism group and the typical students with social difficulties in the Social Skills Checklist. This indicates that the primary effect of the VR social course is effective for both autistic students and typical students with social difficulties (see Table 9 and Table 10).

Table 9.

Tests of between-subjects effects (dependent variable: teaching effectiveness).

Table 10.

Effect of course intervention and grouping.

3.6. Reactions and Changes in Viewing Image Materials Before and After Virtual Reality (VR) Teaching

3.6.1. Chi-Square Test

This study uses situational images to allow students to choose their reactions when encountering unexpected situations: 1. Not knowing how to handle it, 2. Trying to handle it themselves, 3. Actively seeking help. After undergoing the VR social course, typical students with social difficulties shifted from mostly choosing “2. Trying to handle it themselves” to more frequently choosing “3. Actively seeking help”. The chi-square test showed a significant difference, as detailed in Table 11.

Table 11.

Chi-square goodness-of-fit test for social difficulties in the general student group before and after the VR course.

3.6.2. Wilcoxon Sign Rank

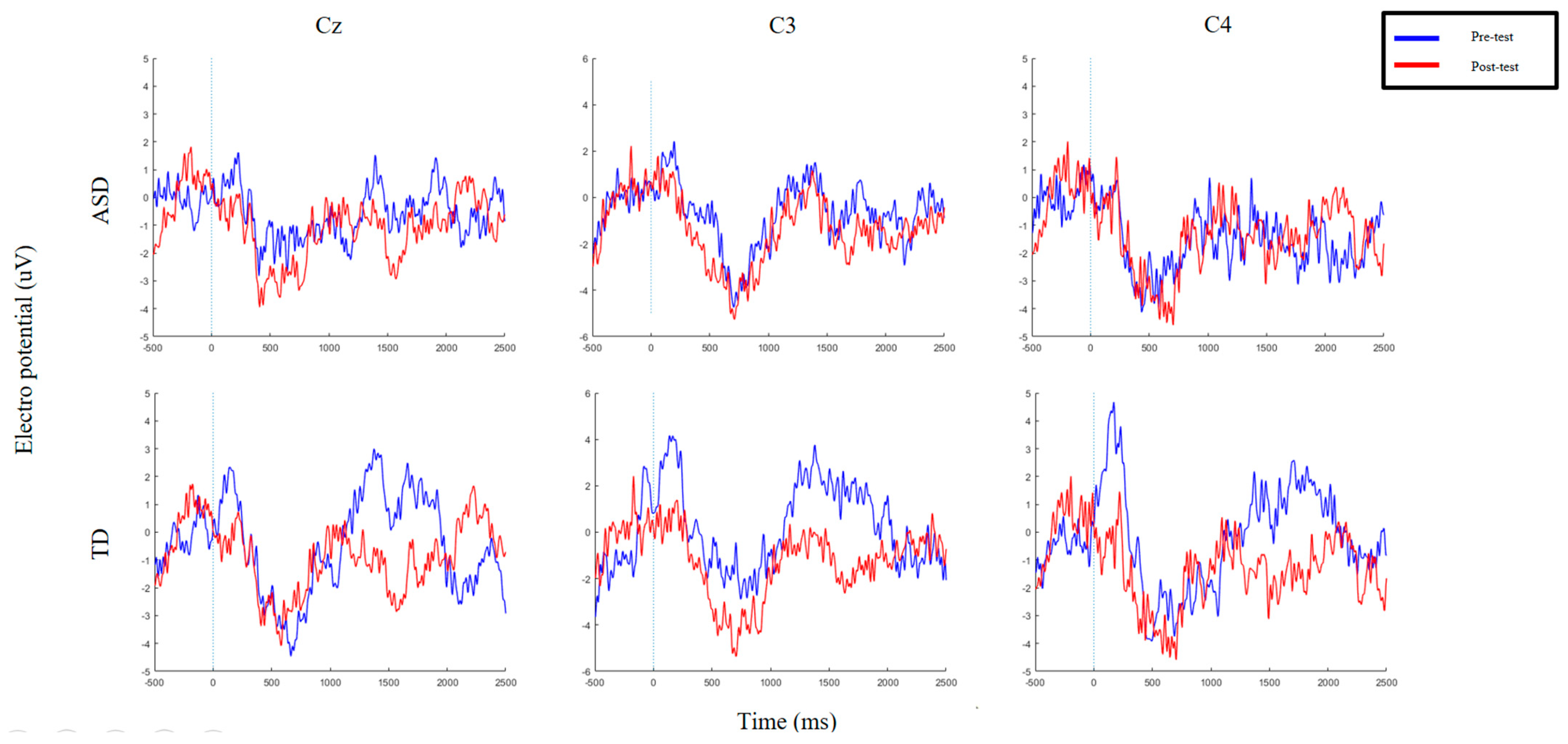

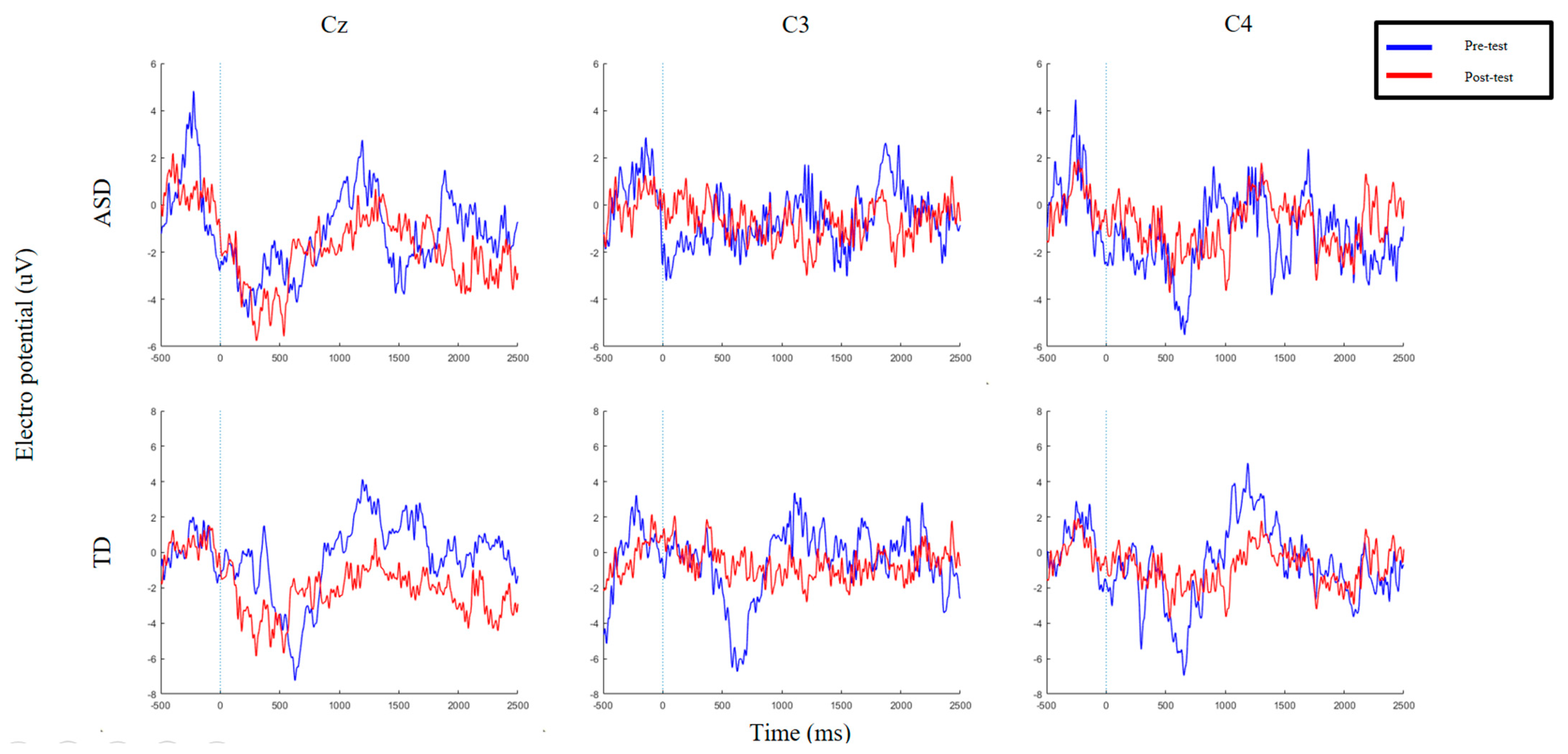

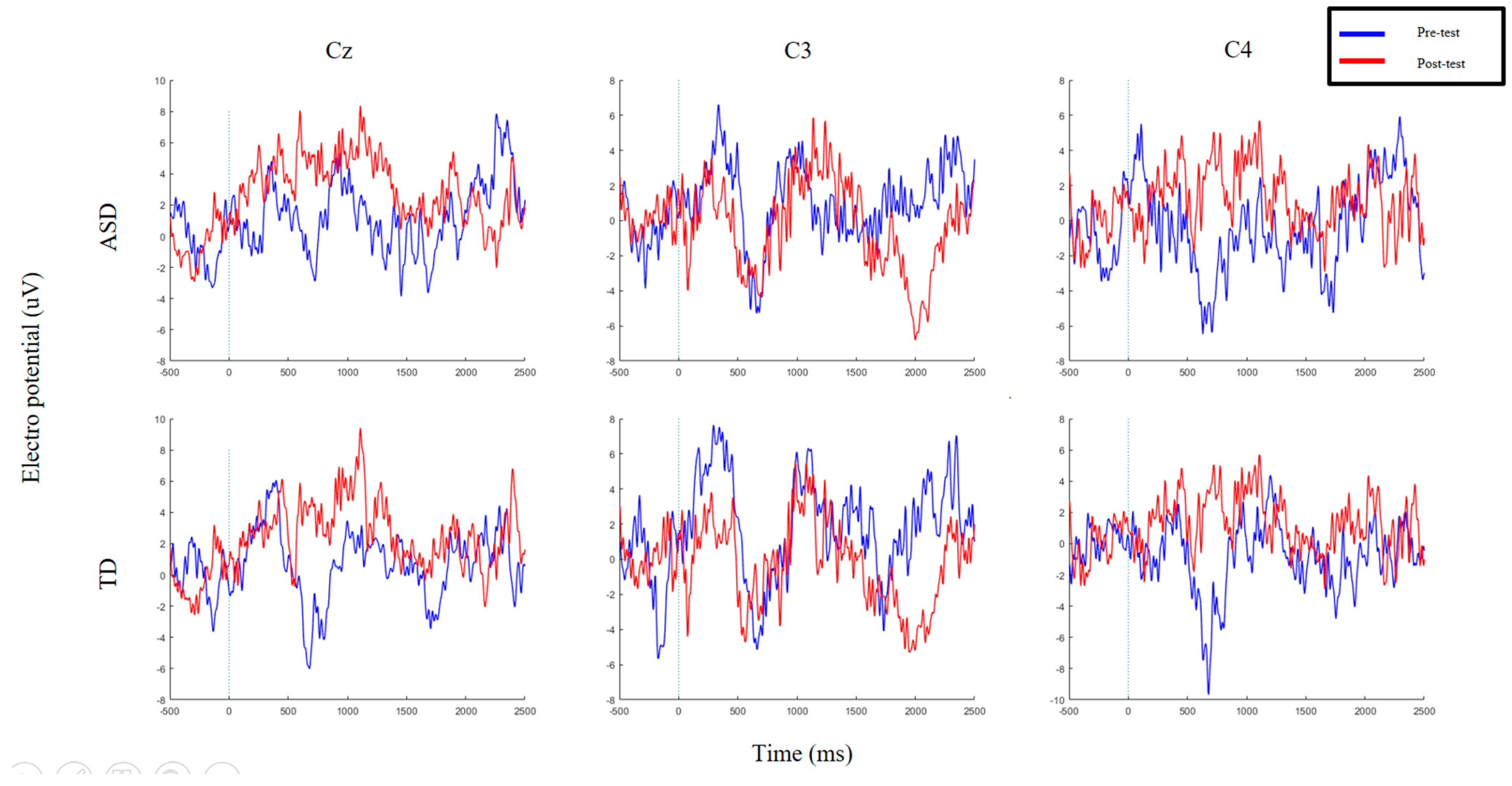

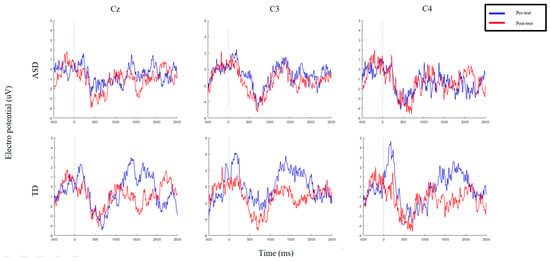

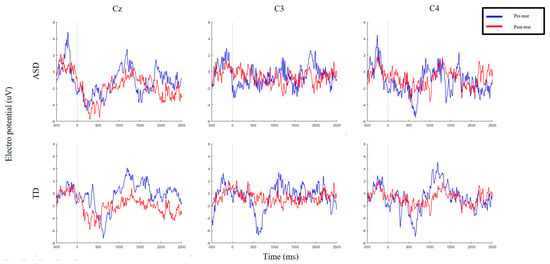

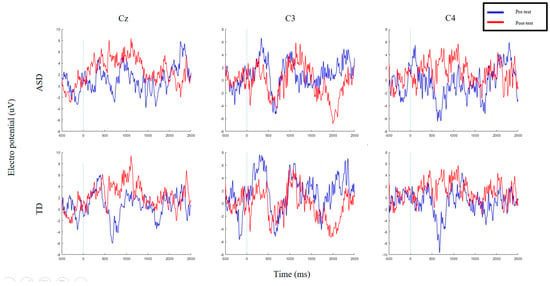

This study observes the brainwave changes through pre-tests and post-tests related to pain perception (Figure 3), emotion recognition (Figure 4), and immediate response (unexpected situations) (Figure 5). The main measured EEG potentials include Cz, C3, and C4.

Figure 3.

Pre- and post-test EEG of general students with social difficulties and autistic students in response to pain.

Figure 4.

Pre- and post-test EEG of general students with social difficulties and autistic students in emotion recognition.

Figure 5.

Pre- and post-test EEG of general students with social difficulties and autistic students in response to an unexpected situation.

4. Discussion

4.1. After Teaching Social Skills Through Virtual Reality (VR), Students’ Overall Performance Scores in the Social Skills Course Significantly Improved

In the Descriptive Statistics for Self-Developed Social Skills Performance Rating Scale, we can observe that although overall performance is generally improved, some courses might require external reminders to maintain focus and perform tasks as students become more familiar with the environment. Not all items show continuous and stable improvement in learning performance. Please refer to Figure 6 for the performance in various aspects. Below, the results for each item are explained one by one.

Figure 6.

Average scores of overall students’ performance in social skills from sessions 1 to 6.

The “integrity of sentence structure” also showed a trend of initially rising and then declining, which is similarly speculated to be due to students responding in a more relaxed and casual manner as they become familiar with the testers and the virtual characters on screen. This is somewhat similar to the common progression of social interactions. As we become familiar with friends or classmates, we tend to use less formal language, which aligns with typical social norms.

“The speed of response” in conversations indeed increased due to repeated practice. However, during the process, students took more time to think as they tried to present sentences or feelings more completely. Overall, by the later stages of practice, students had almost all developed their own complete conversation content, resulting in an overall increase in speed (This course will appropriately review the previous lesson progress based on students’ learning status, thereby providing opportunities for repeated practice). The process of vocabulary generation can be regarded as a mechanism for transferring short-term memory to long-term memory. In the initial stage, when individuals lack sufficient conversational experience in similar contexts, they may struggle to efficiently process language comprehension and produce appropriate responses. However, through repeated practice and refinement, language users gradually accumulate contextual knowledge and store it in their long-term memory system, thereby enhancing their linguistic processing capabilities. This process not only facilitates the development of more automated response patterns, but also improves the efficiency of language selection, enabling individuals to more rapidly determine suitable expressions.

In terms of “conversation expression effectiveness”, there was also improvement after teaching. This includes students’ control over volume and speed during conversations, body language expression, and adjustments in tone and intonation. This result aligns with the discussions in Pragmatics regarding the social and cultural influences on language use, including tone, implicature, and the appropriateness of discourse. It also relates to non-verbal communication and social psychology, particularly in terms of interpersonal behavior patterns and the impact of interactions. Furthermore, it is closely associated with Howard Giles’ Communication Accommodation Theory and Judith Butler’s Performative Theory [33].

The improvement in “sentence structure completeness” indicates that students were able to enhance the completeness of sentence content in conversations through multiple practices. This includes the ability to use subjects, verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs, etc., to narrate an event or express feelings completely, as well as learning to initiate invitations or other questions and conversations proactively. The results also show that students made considerable progress in this ability after training.

4.2. After the Experimental Teaching of Social Skills Through Virtual Reality (VR), Students’ Social Skills Performance in School Life Improved

This section analyzes the performance of students’ social skills in school using the Social Skills Behavior Checklist for Elementary and Junior High School Students (Teacher Version). First, the performance of students’ social skills in school is explained based on the ratings given by school teachers as the basis for effectiveness judgment. As shown in Table 7, the 11 students scored an average of 152 points in the pre-test. After completing six VR teaching sessions, the total score was 143 points, indicating a significant decrease in social interference (the higher the score, the more frequent the inappropriate social skills behaviors). Additionally, through the t-test, as shown in Table 8, it can be seen that all participating students showed significant improvement in social skills performance, indicating that experiencing six VR social interaction courses has a significant benefit on social behavior. The t-value is 2.72, with a significance of 0.022 *.

4.3. Students’ Adaptability to Specific Environments and Self-Care Behaviors Significantly Improved After the Experimental Teaching of Social Skills Through Virtual Reality (VR)

After the experimental teaching of social skills through VR, students’ adaptability to specific environments and self-care behavior improved. This section is based on the Social Skills Effectiveness Opinion Survey filled out by parents, mainly observing changes in students’ daily lives after completing six VR teaching sessions. This part is presented using descriptive statistics. Parents observed that the most significant change in students was their adaptability to the environment, with an average score of 4.106. This indicates that through this teaching course, students were better able to learn to adapt and manage their lives in unfamiliar environments. This includes following the rules of the environment, engaging in appropriate activities in suitable settings (such as adhering to classroom rules during discussions, ordering and paying for meals in restaurants, buying tickets for themselves or others at ticket counters, maintaining silence in exhibition spaces, and freely engaging in activities and recreation in parks). This aligns with the immersive nature of the VR environments used in the teaching.

Additionally, although there was progress in “Accommodating with oneself” and “Communicating with others”, the improvement was not significant. This may be because parents are not fully aware of how students manage themselves and interact with others outside the home. Therefore, it is recommended that the Social Skills Behavior Checklist for Elementary and Junior High School Students mentioned earlier should be used to observe these aspects. This will help to better understand students’ social skills in both home and school settings, gradually piecing together a complete picture of their social interactions. For more details, please refer to Table 6.

4.4. The Content and Teaching Process of This Virtual Reality (VR) Course Is Suitable for Students with Autism as Well as for Typical Students with Social Difficulties

This section uses a two-way ANOVA mixed design for data analysis. First, the “social course” is the within-subjects factor with two levels: “pre-test and post-test”. The “student characteristics” is the between-subjects factor, divided into two levels: “autism group and typical students with social difficulties group”.

Through the univariate analysis of variance with repeated measures of the two factors, the sphericity assumption was first tested, showing a correlation between the two factors. Therefore, the sphericity test could not be performed, and there was no need to adjust the F-value. Then, the variance analysis was conducted, and the results showed a main effect of the social course (F = 6.519, p < 0.05) but no interaction effect between student characteristics and the social course (F = 0.137, p = 0.72). This indicates that the VR course content designed in this study improved social skills to a certain extent for both students with autism and typical students with social difficulties. For more details, please refer to Table 10.

4.5. After Learning Through the Virtual Reality (VR) Course, Typical Students with Social Difficulties Shifted from Independently Solving Problems to Understanding Their Limitations and Seeking Help from Others

After the VR social skills course, the typical students with social difficulties group shifted from mostly choosing “2. Trying to handle it themselves” to more frequently choosing “3. Actively seeking help”. The chi-square test showed a significant difference (0.04*), as shown in Table 10. This indicates that initially, students insisted on facing and handling all problems alone, regardless of their abilities. After the VR teaching, students began to seek help from others, engage in interactions, and assess and understand their problem-solving abilities.

4.6. After the Virtual Reality (VR) Course, Students with Autism Showed Improved Empathetic Responses

In terms of emotion recognition, both students with autism and typical students with social difficulties showed progress, reducing cognitive resource consumption: their on-the-spot response abilities also appeared more efficient after the course, as indicated by the curve changes. This study observed pre-test and post-test brainwave changes in response to pain, emotion recognition, and on-the-spot reactions (unexpected situations).

- Pain Perception: For “pain”, it was found that students with autism had a less noticeable response to pain. It was found that autistic students have a less noticeable response to pain. After the course, their response to the same set of pain perception images remained similar to the pre-test, indicating that short-term course benefits may not directly alter instinctive empathetic reactions. Typical students with social difficulties showed a significant response to pain in the pre-test. However, in the post-test, using the same set of pain perception images, their response gradually became less intense, indicating adaptation to the stimuli (see Figure 2).

- Emotion Recognition: Autistic students showed less noticeable responses to emotions, while typical students with social difficulties exhibited greater fluctuations. After the course, the fluctuations in both autistic students and typical students with social difficulties slightly decreased, suggesting that typical students have improved in emotion recognition and do not need to expend as many cognitive resources (see Figure 3).

- Immediate Response (Unexpected Situations): Both autistic students and typical students with social difficulties showed significant responses when facing unexpected situations. After the social course, the post-test responses at Cz and C4 for autistic students were more active. Typical students with social difficulties also showed brainwave responses at Cz and C4, indicating that both groups of students are able to think about how to address problems in situational contexts (see Figure 5).

The analysis of electroencephalographic (EEG) data reveals substantial differences between the pre-test and post-test waveforms of students with autism. Notably, in the post-test results—following virtual reality (VR)-based social skills training—the EEG waveforms of autistic students demonstrated a notable convergence with those of students experiencing social difficulties. This suggests that participation in structured social skills instruction may induce measurable changes in neural responses to visual stimuli.

Furthermore, these findings support a potential hierarchical model of social competency, wherein typically developing students exhibit advanced social processing abilities, students with social difficulties display intermediate proficiency, and autistic students initially present with the most pronounced deficits in social interaction. However, after engaging in VR-mediated interventions, autistic students demonstrated significant neurophysiological adaptations, with their response patterns becoming more comparable to those of students with social difficulties. This shift underscores the potential of immersive technology as a mechanism for facilitating improvements in social cognition and behavioral regulation in individuals with autism.

5. Conclusions

This study observed the psychological and physiological responses of autistic students and students with social difficulties after participating in VR social skills courses. It was found that both autistic students and general students with social difficulties showed improvements in conversational responses and emotional recognition. They also effectively reduced cognitive resource consumption and increased situational adaptability, demonstrating the effectiveness of using real-world applications in education.

General students with social difficulties often find it hard to express themselves and may easily experience social anxiety, leading them to face problems or setbacks alone and find it difficult to seek help from others. The study results showed that, after VR training, most general students with social difficulties began to seek help from others, which not only increased their social interaction abilities and opportunities, but also suggested that sharing troubles and seeking assistance and cooperation in real-life environments could effectively reduce student stress and expand their interpersonal relationships.

Additionally, the VR social skills scenario courses developed in this study are suitable for both autistic students and students with social difficulties. In inclusive education, which emphasizes mutual learning and tolerance among students, it is recommended that future teachers consider the individual circumstances of their classes when planning courses and provide appropriate materials to increase student interaction.

Finally, the use of VR equipment in education in our country is still relatively lacking. It is recommended to more actively promote VR teaching or use educational apps to make student learning more digital and individualized, keeping pace with the current AI era.

6. Study Limitations

6.1. Source of Subject Recruitment

This study recruited students with high-functioning autism and typical development with social difficulties through announcements on the national autism association’s website and related pages, with the help of special education teachers from various schools. Regional, cultural, and individual differences may affect the results, preventing generalization to all related groups.

6.2. Storytelling and Social Skills

This study focused on a VR teaching theme titled “Art Tour with Classmates” to develop social skills. The content of this theme only includes certain aspects of social skills and does not cover all social skill items, which limits the interpretative power of the final results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-C.Y. and Y.-R.M.; methodology, C.-C.Y.; software, C.-C.Y.; validation, C.-C.Y. and Y.-R.M.; formal analysis, C.-C.Y.; investigation, C.-C.Y.; resources, C.-C.Y.; data curation, C.-C.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-C.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.-C.Y.; visualization, C.-C.Y.; supervision, Y.-R.M.; project administration, Y.-R.M.; funding acquisition, Y.-R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science and Technology Council, grant numbers MOST 111-2410-H-007-016 & NSTC 113-2410-H-007-084.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The subjects of this study belong to a vulnerable group. Therefore, ethical review was applied before the experiment and approval was obtained from the National Tsing Hua University Research Ethics Committee, approval number 11105HT036 (Approved on 15 June 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the involvement of a special population in this study, the related research data will not be made public to protect privacy. However, it can be requested via email by signing a confidentiality agreement.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by funding from the National Science and Technology Council, project number MOST 111-2410-H-007-016/NSTC 113-2410-H-007-084. We also thank the National Tsing Hua University Research Center for Education and Mind Sciences—Brainwave Laboratory for providing space for behavioral experiments, and the National Tsing Hua University Special Education Center for providing space for VR teaching.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| ASD | Autism Students |

| TD | Typical Students with Social Difficulties |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res. 2022, 15, 778–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Special Education Information Network, Special Education Statistics Inquiry. Available online: https://www.set.edu.tw/actclass/fileshare/default.asp (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Lorenzo, G.; Lledó, A.; Pomares, J.; Roig, R. Design and application of an immersive virtual system to enhance emotional skills for children with Autism spectrum disorders. Comput. Educ. 2016, 98, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, S.; Mitchell, P.; Leonard, A. The use and understanding of virtual environments by adolescents with autistic spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 449–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, S.; Leonard, A.; Mitchell, P. Virtual environments for social skills training: Comments from two adolescents with autistic spectrum disorder. Comput. Educ. 2006, 47, 186–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didehbani, N.; Allen, T.; Kandalaft, M.; Krawczyk, D.; Chapman, S. Virtual Reality Social Cognition Training for children with high functioning autism. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsentidou, S.; Poullis, C. Immersive visualizations in a VR cave environment for the training and enhancement of social skills for children with autism. In 9th International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Tzanavari, A.; Charalambous-Darden, N.; Herakleous, K.; Poullis, C. Effectiveness of an Immersive Virtual Environment (CAVE) for Teaching Pedestrian Crossing to Children with PDD-NOS. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, Hualien, Taiwan, 6–9 July 2015; pp. 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGennaro Reed, F.D.; Hyman, S.R.; Hirst, J.M. Applications of technology to teach social skills to children with autism. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 2011, 5, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, H.H.S.; Wong, S.W.L.; Chan, D.F.Y.; Byrne, J.; Li, C.; Yuan, V.S.N.; Lau, K.S.Y.; Wong, J.Y.W. Enhance emotional and social adaptation skills for children with autism spectrum disorder: A VR enabled approach. Comput. Educ. 2018, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesis, P.; Kouklari, E.-C.; Roussos, P.; Mantas, V.; Papanikolaou, K.; Skaloumbakas, C.; Pehlivanidis, A. Virtual Reality Training of Social Skills in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: An Examination of Acceptability, Usability, User Experience, Social Skills, and Executive Functions. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, B.; Evren, B.; Andrew, R. Vocational training with immersive VR for individuals with autism: Towards better design practices. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd Workshop on Everyday Virtual Reality (WEVR), Greenville, SC, USA, 20 March 2016; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.B.; Sherman, W.R.; Will, J.D. Developing Virtual Reality Applications: Foundations of Effective Design; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Manju, T.; Magesh Padmavathi, S. Durairaj Increasing the social interaction of autism child using VR intervention (VRI). In ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjorlu, A.; Hussain, A.; Mødekjær, C.; Austad, N.W. Head-mounted display-based VR social story as a tool to teach social skills to children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. In 2017 IEEE Virtual Reality Workshop on K-12 Embodied Learning through Virtual & Augmented Reality (KELVAR); Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE): Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Amat, A.Z.; Zhao, H.; Swanson, A.; Weitlauf, A.S.; Warren, Z.; Sarkar, N. Design of an interactive VR system, In ViRS, for joint attention practice in autistic children. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2021, 29, 1866–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, Q.; Swanson, A.; Weitlauf, A.; Warren, Z.; Sarkar, N. Design and evaluation of a collaborative virtual environment (CoMove) for autism spectrum disorder intervention. ACM Trans. Access. Comput. 2018, 11, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Lee, S. Virtual reality based collaborative design by children with high-functioning autism: Design-based flexibility, identity, and norm construction. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2016, 24, 1511–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, F.; Moon, J.; Sokolikj, Z. Designing and deploying a virtual social sandbox for autistic children. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2022, 19, 1178–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battocchi, A.; Pianesi, F.; Tomasini, D.; Zancanaro, M.; Esposito, G.; Venuti, P.; Weiss, P.L. Collaborative Puzzle Game: A tabletop interactive game for fostering collaboration in children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Tabletops and Surfaces; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindeman, K.; McDonald, M.E.; Lee, R.; Gehshan, S.; Hoch, H. The Effects of Visual Cues, Prompting, and Feedback within Activity Schedules on Increasing Cooperation Between Pairs of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Spec. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2017, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, E.E.; Bausback, K.; Beard, C.L.; Higinbotham, M.; Bunge, E.L.; Gengoux, G.W. Social Skills Training for Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Meta-analysis of In-person and Technological Interventions. J. Technol. Behav. Sci. 2021, 6, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolphs, R. Cognitive neuroscience of human social behavior. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, M.D. Social cognitive neuroscience: A review of core processes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, J.H.; Lieberman, M.D.; Dapretto, M. “I know you are but what am I?!”: Neural bases of self- and social knowledge retrieval in children and adults. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007, 19, 1323–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, B.; Keysers, C.; Plailly, J.; Royet, J.P.; Gallese, V.; Rizzolatti, G. Both of us disgusted in my insula: The common neural basis of seeing and feeling disgust. Neuron 2003, 40, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberman, L.M.; Pineda, J.A.; Ramachandran, V.S. The human mirror neuron system: A link between action observation and social skills. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2007, 2, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.; Stein, L.; Bentin, S. Motor and attentional mechanisms involved in social interaction–evidence from mu and alpha EEG suppression. Neuroimage 2011, 58, 895–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berchicci, M.; Zhang, T.; Romero, L.; Peters, A.; Annett, R.; Teuscher, U.; Bertollo, M.; Okada, Y.; Stephen, J.; Comani, S. Development of mu rhythm in infants and preschool children. Dev. Neurosci. 2011, 33, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrão, J.G.; Osorio, A.A.C.; Siciliano, R.F.; Lederman, V.R.G.; Kozasa, E.H.; D’Antino, M.E.F.; Tamborim, A.; Santos, V.; de Leucas, D.L.B.; Camargo, P.S.; et al. The Child Emotion Facial Expression Set: A Database for Emotion Recognition in Children. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 666245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Chen, G. High-Functioning Autism/Asperger Syndrome Behavior Checklist. Available online: http://spec.ntct.edu.tw/FileDownLoad/FileUpload/20190328192855968900.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Singh, M. Judith Butler’s Theory of Performativity. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2022, 3, 1981–1984. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).