Abstract

Evidence supports the presence of comorbid conditions, e.g., irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), in individuals with fibromyalgia (FM). Physical therapy plays an essential role in the treatment of FM; however, it is not currently known whether the IBS comorbidity is considered in the selection criteria for clinical trials evaluating physiotherapy in FM. Thus, the aim of the review was to identify whether the presence of IBS was considered in the selection criteria for study subjects for those clinical trials that have been highly cited or published in the high-impact journals investigating the effects of physical therapy in FM. A literature search in the Web of Science database for clinical trials that were highly cited or published in high-impact journals, i.e., first second quartile (Q1) of any category of the Journal Citation Report (JCR), investigating the effects of physical therapy in FM was conducted. The methodological quality of the selected trials was assessed with the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale. Authors, affiliations, number of citations, objectives, sex/gender, age, and eligibility criteria of each article were extracted and analyzed independently by two authors. From a total of the 412 identified articles, 20 and 61 clinical trials were included according to the citation criterion or JCR criterion, respectively. The PEDro score ranged from 2 to 8 (mean: 5.9, SD: 0.1). The comorbidity between FM and IBS was not considered within the eligibility criteria of the participants in any of the clinical trials. The improvement of the eligibility criteria is required in clinical trials on physical therapy that include FM patients to avoid selection bias.

1. Introduction

According to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR), fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic condition associated with widespread pain, fatigue, sleep problems and tenderness [1]. With a worldwide prevalence of 2–3% [2], its prevalence in Spain is 2.4% [3]. Although the diagnostic criteria have evolved from the exclusive presence of generalized pain and pain on palpation at specific locations [4] to the inclusion of questionnaires on pain perception and distress [5], its prevalence has increased as diagnostic criteria evolved [6]. Nonetheless, this pain condition is under-, over-, or misdiagnosed [7]. Regarding the distribution by sex, FM is more frequent in women than in men (female: male ratio 9:1) [8]. Although FM is considered a noninflammatory generalized musculoskeletal pain condition associated with fatigue and sleep disturbances, many patients also exhibit cognitive dysfunction (e.g., brain fog), mood disorders, or intestinal comorbidities, e.g., irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [9].

The etiology and pathophysiology of FM are not well understood [2]. Current theories describe a potential disorder of nociceptive pain processing and central sensitization as the main pathophysiological mechanism [10]. Current evidence shows that individuals with FM usually exhibit several medical comorbidities, e.g., diabetes mellitus, IBS, or mood disorders [11]. Clinicians routinely overlook somatic symptoms, however, if comorbidities are taken into account and treated appropriately, the severity of the symptoms in patients with FM would be reduced [12].

Specifically, IBS is present in 46.2% of people with FM [13], whereas FM occurs in 12.9% to 31.6% of patients with IBS [14]. Both conditions share a wide variety of symptoms such as fatigue, insomnia, anxiety or depression, as well as a predilection for the female gender. As in FM, the pathophysiology of IBS is not understood. There is a hypothesis suggesting a dysregulation of the brain−gut axis resulting in a state of generalized hyperalgesia (also known as central sensitivity disorders) leading to increased excitability of central nociceptive pathways and inhibition of descending pain modulation [15]. This hypothesis could explain the comorbidity presentation between FM and IBS and also the presence of common symptoms.

This similarity between both syndromes should create the need to more exhaustively define the selection of participants with FM in clinical trials [12,13]. Treatment of FM is clearly multifactorial, but it seems that physical therapy has shown to be beneficial for these patients. Several meta-analyses support that physical therapy interventions are effective for reducing symptoms and for improving health-related quality of life in individuals with FM, exercise probably being the most effective [16,17,18]. The main target of physical therapy interventions is the musculoskeletal system, the presence of a comorbid visceral disorder, e.g., IBS, could lead to the necessity of different therapeutic strategies.

Meta-analyses represent the highest level of evidence supporting or refuting a therapeutic intervention, but they are based on randomized clinical trials. The influence of relationships between FM with psychological and somatic-visceral conditions could lead to uncertainty regarding the etiology of symptoms and may influence those clinical outcomes. If medical comorbidities are ignored in the selection criteria of clinical trials, this may limit the potential benefits of physical therapy, which mainly targets musculoskeletal symptomatology. In fact, it has already been identified that the comorbid relationship of IBS with temporomandibular disorders [19,20] is underreported when designing clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of physical therapy [21]. It is, therefore, reasonable to consider that the relationship of FM with IBS could also influence clinical outcomes. No study has previously investigated this topic in clinical trials including individuals with FM. The objective of this scoping review was to identify whether the presence of IBS has been considered in the participating selection criteria of “relevant” clinical trials evaluating the effects of physical therapy in individuals with FM.

2. Methods

This scoping review was conducted following the methodological framework suggested by Arksey and O’Malley [22] consisting of: 1, identify the research question; 2, identify relevant studies; 3, study selection; 4, data extraction; 5, compiling, summarizing, and reporting results. Additionally, it also adheres to the adjusted items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis extension for scoping reviews (Prisma-ScR) and it has been registered in The Open Science Framework Registry (https://osf.io/ns35d (accessed on 20 December 2020)).

2.1. Research Question

The research question of the current scoping review was: has the presence of visceral disorders, e.g., IBS, been considered within the selection criteria of “relevant” clinical trials investigating physical therapy interventions in individuals with FM?

2.2. Identifying Relevant Studies

The literature search was conducted in the Web of Science (WOS) database from the inception of the database to 22 December 2020. The search was conducted by two different assessors and was limited to high-quality clinical trials including humans. No language restriction was applied. A combination of the following terms employing Boolean operators was used for the search: “fibromyalgia” AND, “physical therapy” OR “physiotherapy” OR “exercise” OR “manual therapy”.

2.3. Study Selection

In this review, the PCC (Population, Concept and Context) mnemonic rule was used to define the inclusion criteria.

Population: Men or women diagnosed with FM according to 1900 ACR diagnostic criteria [4], 2010 ACR diagnostic criteria [23] or modified 2010 ACR classification criteria [5]. Alternative diagnostic criteria for FM were also accepted if properly described in the paper.

Concept: Randomized clinical trials evaluating any type of physical therapy intervention, alone or in combination with others, in individuals with FM.

Context: Articles that met one of the following criteria were considered “relevant”: 1, most cited clinical trials from the selection; or, 2, clinical trials published in high impact journals, e.g., of the first quartile (Q1) of any category of the Journal Citation Reports (JCR) evaluated in the year of publication of the study, according to WOS (JCR criterion−impact factor).

The selected studies were identified independently by two investigators considering the title and abstract. For potentially eligible articles, the full text of the article was read. If both researchers disagreed on the inclusion/exclusion of any of the articles, a third researcher decided whether to include/exclude it. All data were saved and managed through Microsoft Office.

2.4. Data Extraction

From selected studies, the following information was extracted following a standardized form: number of authors affiliated with a clinical institution (e.g., hospital, private clinic, or health center), number of authors affiliated with a nonclinical institution (e.g., university or research center), total number of citations in WOS, PEDro score, study objectives, sample size, characteristics of participants (sex distribution, mean age), and inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants selection.

2.5. Methodological Quality

The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale score was used to determine the methodological quality of clinical trials. This scale contains 11 items, which can be scored as absent (0) or present (1), except for the first item that refers to the external validity of the study. Each item is scored from 0 to 10 points. The PEDro scale is a valid, reliable and widely used tool for rating the methodological quality of clinical trials [24]. Studies were considered to be of high quality if they obtained at least 5 points on this scale. The score for each article was extracted from the PEDro database, except for those that were not evaluated by the database. In this case, they were evaluated by two researchers following the guidelines established by the PEDro scale [25].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

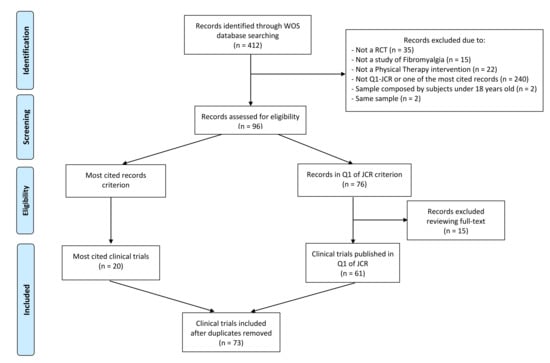

The search identified a total of 412 articles. Of these, 316 were excluded because they did not meet any of the criteria. Of the remaining 96, the full text was accessed, after which 15 articles were excluded. Finally, 20 trials according to the citation criteria and another 61 published in Q1 JCR journals were included. Eight of the selected articles met both criteria; accordingly, a total of 73 different clinical trials were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram. WOS: Web of Science; RCT: randomized clinical trial; JCR: Journal Citation Reports.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Data extracted from the most cited trials are shown in Table 1, data from trials published in Q1 of any category of the JCR are summarized in Table 2, and those fulfilling both criteria are described in Table 3. The total number of citations from those trials included in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 was 3502 (mean citations 175.1, SD: 53.7 per trial). It should be noted that three clinical trials were based on the same sample population [26,27,28]; therefore, the first published one was considered since the inclusion/exclusion criteria are the same [27].

Table 1.

Clinical trials evaluating the effects of physical therapy in FM fulfilling the most-cited criterion only (n = 12).

Table 2.

Clinical trials evaluating the effects of physical therapy in FM fulfilled the Q1-JCR criterion only (n = 53).

Table 3.

Clinical trials evaluating the effects of physical therapy in FM fulfilling both criteria (n = 8).

Authors from non-clinical institutions were part of all trials except one [92], whereas authors from clinical institutions were present in 45.1% of the studies (n = 32/73). The total number of participants in the clinical trials were 6688 (279 men and 6409 women). Sixty-one percent of the trials (n = 45/73) just recruited women, and the remaining studies presented a higher number of women than men in their sample. One study failed to specify the sex [51], and another did not detail either sex or mean age [78]. Another trial did not specify the mean age [36], which ranged from 38 to 59 years for the trial.

3.3. Methodological Quality

According to the PEDro scale, the methodological quality scores ranged from 2 to 8 points (mean: 5.9, SD: 0.1) out of a maximum of 10 points. From the 20 articles included by citation criteria (mean: 5.6, SD: 0.1), all were rated ≥5 points, except one with a score of 4 [35]. In addition, 53 out of 61 of those published in Q1 JCR journal achieved ≥5 points (mean score: 6, SD: 0.14), while the remaining 8 trials received <5 points. There were four clinical trials without evaluation in the PEDro database. According to researchers evaluation, three obtained a good methodological quality [48,56,63].

3.4. Inclusion Criteria in Clinical Trials

After examining the inclusion criteria of all trials, none considered comorbidity from a visceral origin. Only two trials included the absence of concomitant somatic disorders but without any other specification [48,84]. Generally, the common criterion for most clinical trials was “Patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia according to ACR criteria”. Three clinical trials presented diagnostic criteria that differed from the ACR, such as the criteria proposed by Yunus [91], Smythe [95], or both authors [40]. In addition, five studies did not specify which criteria they used for diagnosis of FM [34,51,52,56,62].

3.5. Exclusion Criteria in Clinical Trials

The exclusion criteria were heterogeneous and included pregnancy [27,46,47,53,59,60,61,63,71,74,82,83,86,88,98], neurological diseases [29,35,37,39,41,44,62,65,77,81,82,84,97], rheumatic diseases [29,32,33,39,41,42,43,44,47,55,57,58,59,60,65,74,77,79,80,83,88,91,94,98], psychological/psychiatric conditions [27,32,38,42,45,46,49,50,55,59,60,61,63,64,66,69,70,73,74,75,79,80,81,82,83,89,91,94], intake medication [32,35,41,44,49,54,57,58,64,66,75,95], diabetes mellitus [32,43,44,55,57,58,65,85], cancer [32,34,46,58,64,67,82,89], skin disorders [29,50,51,52,92], trauma [59,60,61,65,83,92], hypertension [32,42,43,44,57,58,65,66,72], migraine [59,60,61,83], osteoarthritis [30,43,66,85,91], peripheral nerve entrapment [59,60,61,83], obesity [29,39,74], substance abuse [64,73,77], and hypotension [50,51,65]. It is important to mention that in 54.7% (n = 40/73) of clinical trials, people with cardiac, pulmonary or kidney diseases were excluded since these “visceral” conditions could limit the therapeutic intervention used in these trials (exercise). Further, seven clinical trials excluded subjects with some visceral pathologies, but not IBS [41,51,64,77,81,82,89]. Four clinical trials did not define any exclusion criteria [40,78,87,93].

4. Discussion

4.1. Findings

The current scoping review has observed that the presence of IBS, a common medical comorbidity, is not consistently considered for the selection of participants in highly cited or published in high-impact journal clinical trials investigating the effects of physical therapy in FM, which could lead to a selection bias.

All clinical trials included individuals with a diagnosis of FM according to ACR criteria, except Buckelew et al. [91], McCain et al. [95] and Wigers et al. [40] that used other criteria. In addition, five studies [34,51,52,56,62] failed to specify the criteria by which the diagnosis of FM was made. The exclusion criteria were generally more heterogeneous, including psychological/psychiatric diseases, neurological diseases, rheumatic diseases, medication, or diabetes mellitus, among the most common. In general, the presence of visceral pathology was not summarized as an exclusion criterion. Four studies considered the possible comorbid conditions that may worsen FM symptomatology without specifying any particular visceral pathology [50,64,89,90]. In addition to IBS, it is important to highlight that other pathologies of visceral origin are also highly comorbid in FMS, and, again, they were not considered in the included trials. This should prompt us to consider the current diagnosis of FM, since it is mainly based on the presence of pain symptoms, considering these comorbidities into this complex spectrum could help to improve the quality of life and management of these patients. Interestingly, albeit the high comorbidity between IBS and FM [12,99], no clinical trial included in this scoping review commented anything on this relationship.

4.2. Why IBS Can Be Relevant for FMS Clinical Outcomes?

Current hypotheses support that IBS ad FMS share common underlying mechanisms leading to increased excitability of central nociceptive pathways [15]. In fact, the presence of previous IBS has been found to be the strongest predictor for new-onset FM development [100]. The presence of comorbid visceral conditions, e.g., IBS, in a musculoskeletal pain condition such as FM, should be considered in clinical practice since visceral pain enhances sensitization [101]. An exacerbation of the symptoms when two comorbid conditions exist is labeled as functional somatic syndrome [102], a situation which should be carefully explored and considered in the management of chronic pain conditions exhibiting manifestations at different levels such as those occurring in individuals with FM. In such a scenario, early recognition of comorbid syndromes of different etiology, but exhibiting a common mechanism, may identify subgroups of patients with different etiologies and different needs of treatment [103].

Comorbid visceral conditions should not be ignored when a physical therapy intervention is tested, as potentially occurred in the identified trials in the current scoping review. We do not know if considering comorbid visceral conditions in people with musculoskeletal pain conditions participating in physical therapy clinical trials could lead to potentially different clinical outcomes. This is relevant, considering that visceral pain shares several features with musculoskeletal pain but clearly requires different therapeutic strategies. For instance, the current understanding of the neurosciences is continuously evolving for better adaptation of exercise programs in individuals with nociplastic pain, a category where FM could be included [104]. It is possible that individuals with FM and comorbid IBS need different exercise programs to those with other comorbidities or without IBS. Future clinical trials should investigate the effects of multimodal therapeutic approaches considering the presence of these visceral comorbidities, e.g., IBS, in patients with a primary musculoskeletal complaint, e.g., FM.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

Findings from the current scoping review should be considered according to its strengths and limitations. Strengths include a comprehensive literature search, methodological data extraction, and the inclusion of highly cited and published clinical trials in high-impact journals investigating physical therapy for FM. Among the limitations, first, the search was conducted on a single database, the WOS, because it is the only database presenting the index classification by JCR. Second, physical therapy interventions were heterogeneous, ranging from manual therapy to exercise alone or combined with physical agents. Third, 95% of the patients included in the clinical trials were female; nonetheless, this is related to the fact that FM is more prevalent in females and also that a greater frequency of comorbidity in pain syndromes is present in females [105].

5. Conclusions

This scoping review found that highly cited clinical trials or those published in high impact journals investigating the effects of physical therapy interventions in individuals with FM did not consider the presence of comorbid IBS in their eligibility criteria. In turn, other pathologies were sometimes considered, mostly linked to exercise, e.g., cardiac or kidney diseases. Current results highlight that the presence of intestinal pathology is underestimated when treating a musculoskeletal pain condition. Based on our results, stricter inclusion and exclusion criteria would be required in clinical trials involving patients with FM to avoid possible subject selection biases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F.-d.-l.-P., F.A.-S. and D.P.R.-d.-S.; methodology, C.F.-d.-l.-P., F.A.-S. and D.P.R.-d.-S.; formal analysis, P.M.R.-C., C.F.-d.-l.-P., F.A.-S. and D.P.R.-d.-S.; investigation, P.M.R.-C., C.F.-d.-l.-P., F.A.-S. and D.P.R.-d.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M.R.-C., C.F.-d.-l.-P., F.A.-S. and D.P.R.-d.-S.; writing—review and editing, P.M.R.-C., C.F.-d.-l.-P., F.A.-S. and D.P.R.-d.-S.; supervision, P.M.R.-C., C.F.-d.-l.-P., F.A.-S. and D.P.R.-d.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amigues, I. Fibromyalgia. Available online: https://www.rheumatology.org/I-Am-A/Patient-Caregiver/Diseases-Conditions/Fibromyalgia (accessed on 9 August 2021).

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Giorgi, V.; Marotto, D.; Atzeni, F. Fibromyalgia: An Update on Clinical Characteristics, Aetiopathogenesis and Treatment. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020, 16, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laffón, A.; Carmona, L.; Ballina, F.J.; Gabriel, R.; Garrido, G. Prevalencia e Impacto de Las Enfermedades Reumáticas En La Población Adulta Española. Soc. Esp. Reumatol. 2001, 1, 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, F.; Smythe, H.A.; Yunus, M.B.; Bennett, R.M.; Bombardier, C.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Tugwell, P.; Campbell, S.M.; Abeles, M.; Clark, P.; et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1990, 33, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Häuser, W.; Katz, R.L.; Mease, P.J.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Walitt, B. 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2016, 46, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.T.; Atzeni, F.; Beasley, M.; Flüß, E.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Macfarlane, G.J. The Prevalence of Fibromyalgia in the General Population: A Comparison of the American College of Rheumatology 1990, 2010, and Modified 2010 Classification Criteria. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015, 67, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Fitzcharles, M.A. Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Under-, over- and Misdiagnosis. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37, S90–S97. [Google Scholar]

- Miró, E.; Diener, F.N.; Martínez, P.; Sánchez, A.I.; Valenza, M.C. La Fibromialgia En Hombres y Mujeres: Comparación de Los Principales Síntomas Clínicos. Psicothema 2012, 24, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Üçüncü, M.Z.; Çoruh Akyol, B.; Toprak, D. The Early Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia in Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients. Med. Hypotheses 2020, 143, 110119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bair, M.J.; Krebs, E.E. Fibromyalgia. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, ITC33–ITC48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleykamp, B.A.; Ferguson, M.C.; McNicol, E.; Bixho, I.; Arnold, L.M.; Edwards, R.R.; Fillingim, R.; Grol-Prokopczyk, H.; Turk, D.C.; Dworkin, R.H. The Prevalence of Psychiatric and Chronic Pain Comorbidities in Fibromyalgia: An Acttion Systematic Review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2021, 51, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein, A.; Tiosano, S.; Amital, H. The Complexities of Fibromyalgia and Its Comorbidities. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2017, 29, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdrich, S.; Hawrelak, J.A.; Myers, S.P.; Harnett, J.E. A Systematic Review of the Association between Fibromyalgia and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2020, 13, 1756284820977402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, F.; Afshari, M.; Moosazadeh, M. Prevalence of Fibromyalgia in General Population and Patients, a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rheumatol. Int. 2017, 37, 1527–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, C.; Sayuk, G.S. The Brain-Gut-Microbiotal Axis: A Framework for Understanding Functional GI Illness and Their Therapeutic Interventions. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 84, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, N.B.; Salemi, M.d.M.; de Alencar, G.G.; Moreira, M.C.; de Siqueira, G.R. Efficacy of Manual Therapy on Pain, Impact of Disease, and Quality of Life in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review. Pain Physician 2020, 23, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão-Moreira, L.V.; de Castro, L.O.; Moura, E.C.R.; de Oliveira, C.M.B.; Nogueira Neto, J.; Gomes, L.M.R.D.S.; Leal, P.D.C. Pool-Based Exercise for Amelioration of Pain in Adults with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2021, 31, 904–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.L.K.; Matsutani, L.A.; Marques, A.P. Effectiveness of Different Styles of Massage Therapy in Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Man. Ther. 2015, 20, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallotta, S.; Bruno, V.; Catapano, S.; Mobilio, N.; Ciacci, C.; Iovino, P. High Risk of Temporomandibular Disorder in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Is There a Correlation with Greater Illness Severity? World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobilio, N.; Iovino, P.; Bruno, V.; Catapano, S. Severity of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Patients with Temporomandibular Disorders: A Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2019, 11, e802–e806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-De-souza, D.P.; Paz-Vega, J.; Fernández-De-las-peñas, C.; Cleland, J.A.; Alburquerque-Sendín, F. Is Irritable Bowel Syndrome Considered in Clinical Trials on Physical Therapy Applied to Patients with Temporo-Mandibular Disorders? A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashin, A.G.; McAuley, J.H. Clinimetrics: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale. J. Physiother. 2020, 66, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physiotherapy Evidence Database PEDro. Physiotherapy Evidence Database. Available online: https://pedro.org.au/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Van Koulil, S.; Kraaimaat, F.W.; Van Lankveld, W.; Van Helmond, T.; Vedder, A.; Van Hoorn, H.; Donders, A.R.T.; Thieme, K.; Cats, H.; Van Riel, P.L.C.M.; et al. Cognitive-Behavioral Mechanisms in a Pain-Avoidance and a Pain-Persistence Treatment for High-Risk Fibromyalgia Patients. Arthritis Care Res. 2011, 63, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Koulil, S.; Van Lankveld, W.; Kraaimaat, F.W.; Van Helmond, T.; Vedder, A.; Van Hoorn, H.; Donders, R.; De Jong, A.J.L.; Haverman, J.F.; Korff, K.J.; et al. Tailored Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy and Exercise Training for High-Risk Patients with Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Koulil, S.; Van Lankveld, W.; Kraaimaat, F.W.; Van Helmond, T.; Vedder, A.; Van Hoorn, H.; Donders, A.R.T.; Wirken, L.; Cats, H.; Van Riel, P.L.C.M.; et al. Tailored Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy and Exercise Training Improves the Physical Fitness of Patients with Fibromyalgia. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 70, 2131–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, M.R.; Silva, L.E.; Barros Alves, A.M.; Pessanha, A.P.; Valim, V.; Feldman, D.; De Barros Neto, T.L.; Natour, J. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Deep Water Running: Clinical Effectiveness of Aquatic Exercise to Treat Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2006, 55, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burckhardt, C.S.; Mannerkorpi, K.; Hedenberg, L.; Bjelle, A. A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial of Education and Physical Training for Women with Fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 1994, 21, 714–720. [Google Scholar]

- Gowans, S.E.; DeHueck, A.; Voss, S.; Richardson, M. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Exercise and Education for Individuals with Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 1999, 12, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowans, S.E.; Dehueck, A.; Voss, S.; Silaj, A.; Abbey, S.E.; Reynolds, W.J. Effect of a Randomized, Controlled Trial of Exercise on Mood and Physical Function in Individuals with Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2001, 45, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.J.; Wessel, J.; Bhambhani, Y.; Sholter, D.; Maksymowych, W. The Effects of Exercise and Education, Individually or Combined, in Women with Fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 2002, 29, 2620–2627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K.R.; Ritter, P.L.; Laurent, D.D.; Plant, K. The Internet-Based Arthritis Self-Management Program: A One-Year Randomized Trial for Patients with Arthritis or Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2008, 59, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Nutting, A.; Macintosh, B.R.; Edworthy, S.M.; Butterwick, D.; Cook, J. An Exercise Program in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 1996, 23, 1050–1053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Redondo, J.R.; Justo, C.M.; Moraleda, F.V.; Velayos, Y.G.; Puche, J.J.O.; Zubero, J.R.; Hernández, T.G.; Ortells, L.C.; Pareja, M.Á.V. Long-Term Efficacy of Therapy in Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Physical Exercise-Based Program and a Cognitive-Behavioral Approach. Arthritis Care Res. 2004, 51, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.C.M.; Scott, D.L. Prescribed Exercise in People with Fibromyalgia: Parallel Group Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2002, 325, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sephton, S.E.; Salmon, P.; Weissbecker, I.; Ulmer, C.; Floyd, A.; Hoover, K.; Studts, J.L. Mindfulness Meditation Alleviates Depressive Symptoms in Women with Fibromyalgia: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2007, 57, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valim, V.; Oliveira, L.; Suda, A.; Silva, L.; De Assis, M.; Neto, T.B.; Feldman, D.; Natour, J. Aerobic Fitness Effects in Fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 2003, 30, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Wigers, S.H.; Stiles, T.C.; Vogel, P.A. Effects of Aerobic Exercise versus Stress Management Treatment in Fibromyalgia: A 4.5 Year Prospective Study. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 1996, 25, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.F.; Roizenblatt, S.; Benedito-Silva, A.A.; Tufik, S. The Effect of Combined Therapy (Ultrasound and Interferential Current) on Pain and Sleep in Fibromyalgia. Pain 2003, 104, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altan, L.; Korkmaz, N.; Bingol, Ü.; Gunay, B. Effect of Pilates Training on People with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.P.; Zamunér, A.R.; Forti, M.; França, T.F.; Tamburús, N.Y.; Silva, E. Oxygen Uptake and Body Composition after Aquatic Physical Training in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2017, 53, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.P.; Zamunér, A.R.; Forti, M.; Tamburús, N.Y.; Silva, E. Effects of Aquatic Training and Detraining on Women with Fibromyalgia: Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 55, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjersing, J.L.; Dehlin, M.; Erlandsson, M.; Bokarewa, M.I.; Mannerkorpi, K. Changes in Pain and Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 in Fibromyalgia during Exercise: The Involvement of Cerebrospinal Inflammatory Factors and Neuropeptides. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgault, P.; Lacasse, A.; Marchand, S.; Courtemanche-Harel, R.; Charest, J.; Gaumond, I.; De Souza, J.B.; Choinière, M. Multicomponent Interdisciplinary Group Intervention for Self-Management of Fibromyalgia: A Mixed-Methods Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonario, F.; Matsutani, L.A.; Yuan, S.L.K.; Marques, A.P. Effectiveness of High-Frequency Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation at Tender Points as Adjuvant Therapy for Patients with Fibromyalgia. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2013, 49, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Carbonell-Baeza, A.; Aparicio, V.A.; Ortega, F.B.; Cuevas, A.M.; Alvarez, I.C.; Ruiz, J.R.; Delgado-Fernandez, M. Does a 3-Month Multidisciplinary Intervention Improve Pain, Body Composition and Physical Fitness in Women with Fibromyalgia? Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 1189–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, J.W.; Carson, K.M.; Jones, K.D.; Bennett, R.M.; Wright, C.L.; Mist, S.D. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of the Yoga of Awareness Program in the Management of Fibromyalgia. Pain 2010, 151, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Sánchez, A.M.; Lopez, H.G.; Sanchez, M.F.; Marmol, J.M.P.; Aguilar-Ferrandiz, M.E.; Suarez, A.L.; Penarrocha, G.A.M. Improvement in Clinical Outcomes after Dry Needling versus Myofascial Release on Pain Pressure Thresholds, Quality of Life, Fatigue, Pain Intensity, Quality of Sleep, Anxiety, and Depression in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Disabil. Rehabil. 2018, 41, 2235–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Sánchez, A.M.; Matarán-Peñarrocha, G.A.; Arroyo-Morales, M.; Saavedra-Hernández, M.; Fernández-Sola, C.; Moreno-Lorenzo, C. Effects of Myofascial Release Techniques on Pain, Physical Function, and Postural Stability in Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Sánchez, A.M.; Matarán-Peñarrocha, G.A.; Sánchez-Labraca, N.; Quesada-Rubio, J.M.; Granero-Molina, J.; Moreno-Lorenzo, C. A Randomized Controlled Trial Investigating the Effects of Craniosacral Therapy on Pain and Heart Rate Variability in Fibromyalgia Patients. Clin. Rehabil. 2011, 25, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Mateo, D.; Dominguez-Muñoz, F.J.; Adsuar, J.C.; Garcia-Gordillo, M.A.; Gusi, N. Effects of Exergames on Quality of Life, Pain, and Disease Effect in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 98, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, D.; Abrahamowicz, M.; Lowensteyn, I.; Bernatsky, S.; Dritsa, M.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Dobkin, P.L. A Randomized Clinical Trial of an Individualized Home-Based Exercise Programme for Women with Fibromyalgia. Rheumatology 2005, 44, 1422–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, G.; Jennings, F.; Nery Cabral, M.V.; Pirozzi Buosi, A.L.; Natour, J. Swimming Improves Pain and Functional Capacity of Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2016, 97, 1269–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Ardila, E.M.; González-López-Arza, M.V.; Jiménez-Palomares, M.; García-Nogales, A.; Rodríguez-Mansilla, J. Effectiveness of Acupuncture vs. Core Stability Training in Balance and Functional Capacity of Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 34, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavi, M.B.R.O.; Vassalo, D.V.; Amaral, F.T.; Macedo, D.C.F.; Gava, P.L.; Dantas, E.M.; Valim, V. Strengthening Exercises Improve Symptoms and Quality of Life but Do Not Change Autonomic Modulation in Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowans, S.E.; DeHueck, A.; Abbey, S.E. Measuring Exercise-Induced Mood Changes in Fibromyalgia: A Comparison of Several Measures. Arthritis Care Res. 2002, 47, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusi, N.; Tomas-Carus, P. Cost-Utility of an 8-Month Aquatic Training for Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2008, 10, R24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusi, N.; Tomas-Carus, P.; Häkkinen, A.; Häkkinen, K.; Ortega-Alonso, A. Exercise in Waist-High Warm Water Decreases Pain and Improves Health-Related Quality of Life and Strength in the Lower Extremities in Women with Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 2006, 55, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusi, N.; Parraca, J.A.; Olivares, P.R.; Leal, A.; Adsuar, J.C. Tilt Vibratory Exercise and the Dynamic Balance in Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeger Bement, M.K.; Weyer, A.; Hartley, S.; Drewek, B.; Harkins, A.L.; Hunter, S.K. Pain Perception after Isometric Exercise in Women with Fibromyalgia. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooten, W.M.; Qu, W.; Townsend, C.O.; Judd, J.W. Effects of Strength vs Aerobic Exercise on Pain Severity in Adults with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Equivalence Trial. Pain 2012, 153, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.C.; Schubiner, H.; Lumley, M.A.; Stracks, J.S.; Clauw, D.J.; Williams, D.A. Sustained Pain Reduction through Affective Self-Awareness in Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibar, S.; Ecem Yildiz, H.; Ay, S.; Evcik, D.; Süreyya Ergin, E. New Approach in Fibromyalgia Exercise Program: A Preliminary Study Regarding the Effectiveness of Balance Training. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, A.; Palstam, A.; Löfgren, M.; Ernberg, M.; Bjersing, J.; Bileviciute-Ljungar, I.; Gerdle, B.; Kosek, E.; Mannerkorpi, K. Resistance Exercise Improves Muscle Strength, Health Status and Pain Intensity in Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2015, 17, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemstra, M.; Olszynski, W.P. The Effectiveness of Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation in the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. Clin. J. Pain 2005, 21, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Sawynok, J.; Hiew, C.; Marcon, D. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Qigong for Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.; Torre, F.; Aguirre, U.; González, N.; Padierna, A.; Matellanes, B.; Quintana, J.M.S.O.S.C. Evaluation of the Interdisciplinary PSYMEPHY Treatment on Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Control Trial. Pain Med. 2014, 15, 682–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.; Torre, F.; Padierna, A.; Aguirre, U.; González, N.; Matellanes, B.; Quintana, J.M. Impact of Interdisciplinary Treatment on Physical and Psychosocial Parameters in Patients with Fibromyalgia: Results of a Randomised Trial. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2014, 68, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martínez, J.P.; Villafaina, S.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Pérez-Gómez, J.; Gusi, N. Effects of 24-Week Exergame Intervention on Physical Function under Single- and Dual-Task Conditions in Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2019, 29, 1610–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.B.; Lemley, K.J. Utilizing Exercise to Affect the Symptomology of Fibromyalgia: A Pilot Study. J. Am. Coll. Sport. Med. 2000, 32, 1691–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, G.; García-Palacios, A.; Enrique, Á.; Roca, P.; Comella, N.F.L.; Botella, C. The Power of Visualization: Back to the Future for Pain Management in Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain Med. 2018, 19, 1451–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munguía-Izquierdo, D.; Legaz-Arrese, A. Assessment of the Effects of Aquatic Therapy on Global Symptomatology in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 2250–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, L.W.; Koltyn, K.F.; Morgan, W.P.; Cook, D.B. Influence of Preferred versus Prescribed Exercise on Pain in Fibromyalgia. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.; Cronan, T.A.; Walen, H.R.; Tomita, M. Effects of Social Support and Education on Health Care Costs for Patients with Fibromyalgia. J. Rheumatol. 2001, 28, 2711–2719. [Google Scholar]

- Pujol, J.; Ramos-López, D.; Blanco-Hinojo, L.; Pujol, G.; Ortiz, H.; Martínez-Vilavella, G.; Blanch, J.; Monfort, J.; Deus, J. Testing the Effects of Gentle Vibrotactile Stimulation on Symptom Relief in Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2019, 21, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, C.; Moreland, J.; Ho, M.; Joyce, S.; Walker, S.; Pullar, T. An Observer-Blinded Comparison of Supervised and Unsupervised Aerobic Exercise Regimens in Fibromyalgia. Rheumatology 2000, 39, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo, B.; Galiano, D.; Carrasco, L.; Blagojevic, M.; De Hoyo, M.; Saxton, J. Aerobic Exercise versus Combined Exercise Therapy in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010, 91, 1838–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sañudo Corrales, B.; Galiano, D.; Carrasco, L.; De Hoyo, M.; McVeigh, J.G. Effects of a Prolonged Exercise Programme on Key Health Outcomes in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 43, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targino, R.A.; Imamura, M.; Kaziyama, H.H.S.; Souza, L.P.M.; Hsing, W.T.; Furlan, A.D.; Imamura, S.T.; Neto, R.S.A. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Acupuncture Added to Usual Treatment for Fibromyalgia. J. Rehabil. Med. 2008, 40, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thieme, K.; Gromnica-Ihle, E.; Flor, H. Operant Behavioral Treatment of Fibromyalgia: A Controlled Study. Arthritis Care Res. 2003, 49, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas-Carus, P.; Häkkinen, A.; Gusi, N.; Leal, A.; Häkkinen, K.; Ortega-Alonso, A. Aquatic Training and Detraining on Fitness and Quality of Life in Fibromyalgia. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, J.R.; Martos, I.C.; Sánchez, I.T.; Rubio, A.O.; Pelegrina, A.D.; Valenza, M.C. Results of an Active Neurodynamic Mobilization Program in Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2015, 96, 1771–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valkeinen, H.; Alén, M.; Häkkinen, A.; Hannonen, P.; Kukkonen-Harjula, K.; Häkkinen, K. Effects of Concurrent Strength and Endurance Training on Physical Fitness and Symptoms in Postmenopausal Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 1660–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villafaina, S.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Domínguez-Muñoz, F.J.; Fuentes-García, J.P.; Gusi, N. Benefits of 24-Week Exergame Intervention on Health-Related Quality of Life and Pain in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Games Health J. 2019, 8, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo Vitorino, D.F.; de Carvalho, L.B.C.; do Prado, G.F. Hydrotherapy and Conventional Physiotherapy Improve Total Sleep Time and Quality of Life of Fibromyalgia Patients: Randomized Clinical Trial. Sleep Med. 2006, 7, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Schmid, C.H.; Fielding, R.A.; Harvey, W.F.; Reid, K.F.; Price, L.L.; Driban, J.B.; Kalish, R.; Rones, R.; McAlindon, T. Effect of Tai Chi versus Aerobic Exercise for Fibromyalgia: Comparative Effectiveness Randomized Controlled Trial. BMJ 2018, 360, k851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.A.; Kuper, D.; Segar, M.; Mohan, N.; Sheth, M.; Clauw, D.J. Internet-Enhanced Management of Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain 2010, 151, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zijlstra, T.R.; van de Laar, M.A.F.J.; Bernelot Moens, H.J.; Taal, E.; Zakraoui, L.; Rasker, J.J. Spa Treatment for Primary Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Combination of Thalassotherapy, Exercise and Patient Education Improves Symptoms and Quality of Life. Rheumatology 2005, 44, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckelew, S.P.; Conway, R.; Parker, J.; Deuser, W.E.; Read, J.; Witty, T.E.; Hewett, J.E.; Minor, M.; Johnson, J.C.; Van Male, L.; et al. Biofeedback/Relaxation Training and Exercise Interventions for Fibromyalgia: A Prospective Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1998, 11, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedraschi, C.; Desmeules, J.; Rapiti, E.; Baumgartner, E.; Cohen, P.; Finckh, A.; Allaz, A.F.; Vischer, T.L. Fibromyalgia: A Randomised, Controlled Trial of a Treatment Programme Based on Self Management. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2004, 63, 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häkkinen, A.; Häkkinen, K.; Hannonen, P.; Alen, M. Strength Training Induced Adaptations in Neuromuscular Function of Premenopausal Women with Fibromyalgia: Comparison with Healthy Women. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2001, 60, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannerkorpi, K.; Nyberg, B.; Ahlmen, M.; Ekdahl, C. Pool Exercise Combined with an Education Program for Patients with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. A Prospective, Randomized Study. J. Rheumatol. 2000, 27, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar]

- Mccain, G.A.; Bell, D.A.; Mai, F.M.; Halliday, P.D. A Controlled Study of the Effects of a Supervised Cardiovascular Fitness Training Program on the Manifestations of Primary Fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1988, 31, 1135–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooks, D.S.; Gautam, S.; Romeling, M.; Cross, M.L.; Stratigakis, D.; Evans, B.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Iversen, M.D.; Katz, J.N. Group Exercise, Education, and Combination Self-Management in Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, C.L.; Busch, A.J.; Peloso, P.M.; Sheppard, M.S. Effects of Short versus Long Bouts of Aerobic Exercise in Sedentary Women with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Schmid, C.H.; Rones, R.; Kalish, R.; Yinh, J.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Lee, Y.; McAlindon, T. A Randomized Trial of Tai Chi for Fibromyalgia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilge, U.; Sari, Y.E.; Balcioglu, H.; Bilge, N.S.Y.; Kasifoglu, T.; Kayhan, M.; Ünlüoglu, I. Prevalence of Comorbid Diseases in Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2018, 68, 729–732. [Google Scholar]

- Monden, R.; Rosmalen, J.G.M.; Wardenaar, K.J.; Creed, F. Predictors of New Onsets of Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Fibromyalgia: The Lifelines Study. Psychol. Med. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verne, G.N.; Price, D.D. Irritable Bowel Syndrome As a Common Precipitant of Central Sensitization. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2002, 4, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorduy, K.M.; Liegey-Dougall, A.; Haggard, R.; Sanders, C.; Gatchel, R.J. The Prevalence of Comorbid Symptoms of Central Sensitization Syndrome among Three Different. Pain Pract. 2013, 13, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandvik, P.O.; Wilhelmsen, I.; Ihlebæk, C.; Farup, P.G. Comorbidity of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in General Practice: A Striking Feature with Clinical Implications. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 20, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro Moura Franco, K.; Lenoir, D.; dos Santos Franco, Y.R.; Jandre Reis, F.J.; Nunes Cabral, C.M.; Meeus, M. Prescription of Exercises for the Treatment of Chronic Pain along the Continuum of Nociplastic Pain: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Pain 2021, 25, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, V.R.; McBeth, J.; Zakrzewska, J.M.; Lunt, M.; Macfarlane, G.J. The Epidemiology of Chronic Syndromes That Are Frequently Unexplained: Do They Have Common Associated Factors? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 35, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).