Compounded Effects of Multiple Global Crises on Mental Health: A Longitudinal Study of East German Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Climate Change

1.2. The COVID-19 Pandemic

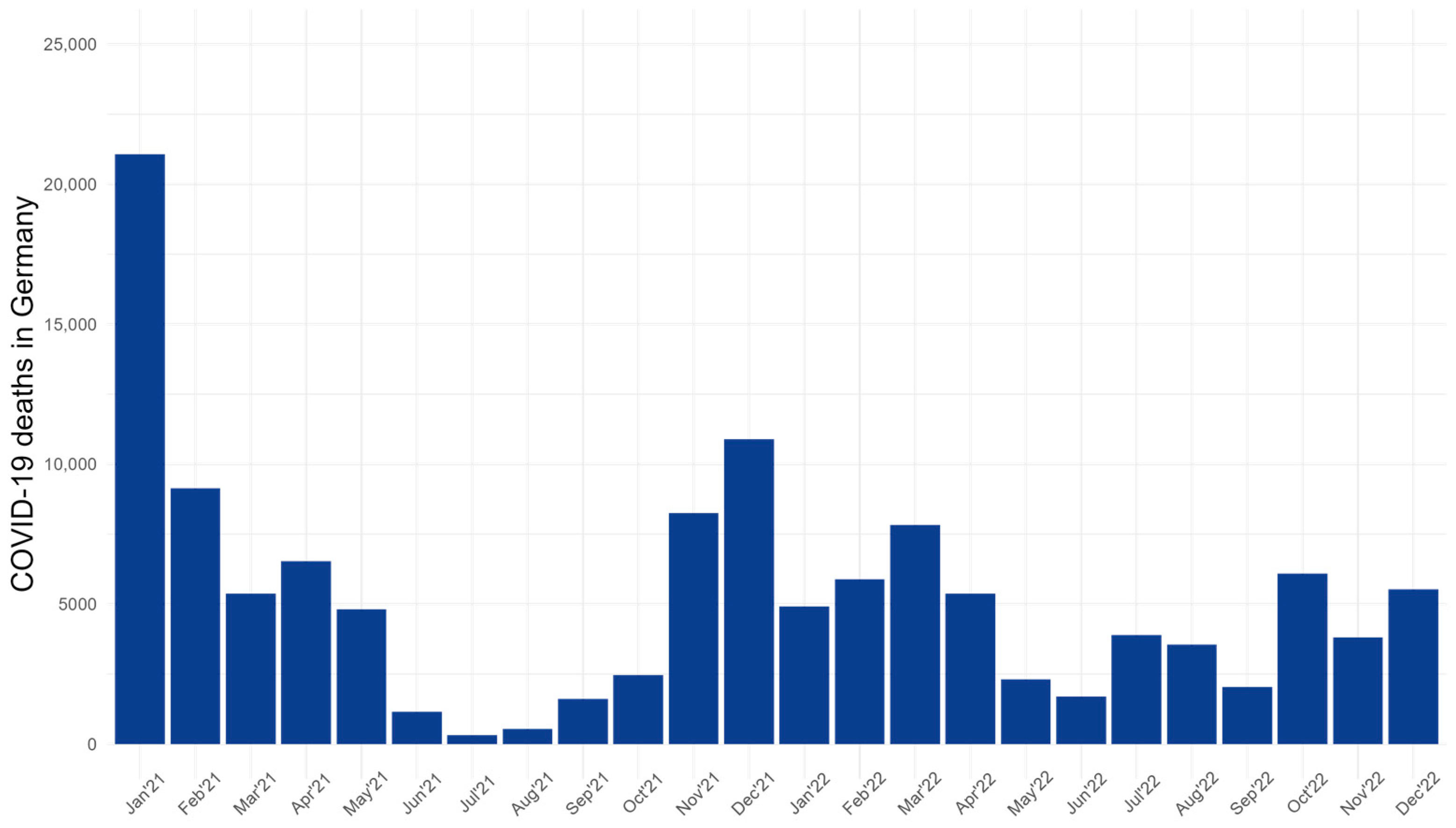

1.3. Russia–Ukraine War (RUW)

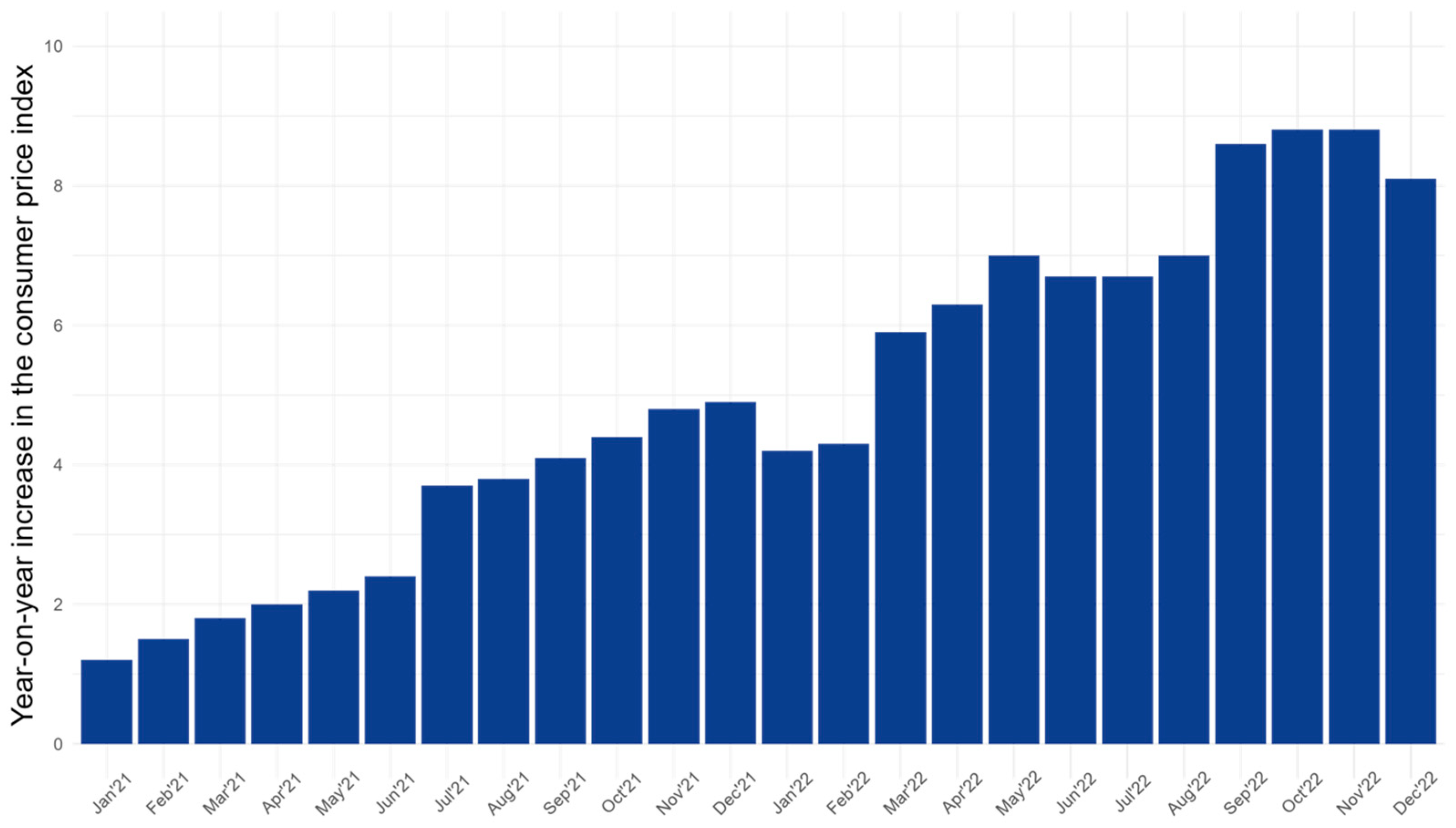

1.4. Rising Costs of Living Crisis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Measures

2.2.2. Covariates—Perceived Threat from Crisis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Unadjusted Analysis

2.3.2. Adjusted Analysis

2.3.3. Variance Explanation and Hierarchical Partitioning Derived from Adjusted Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Unadjusted Analysis: General Trend of Mental Health over Time

3.3. Adjusted Analysis: Individual and General Trends in Mental Health

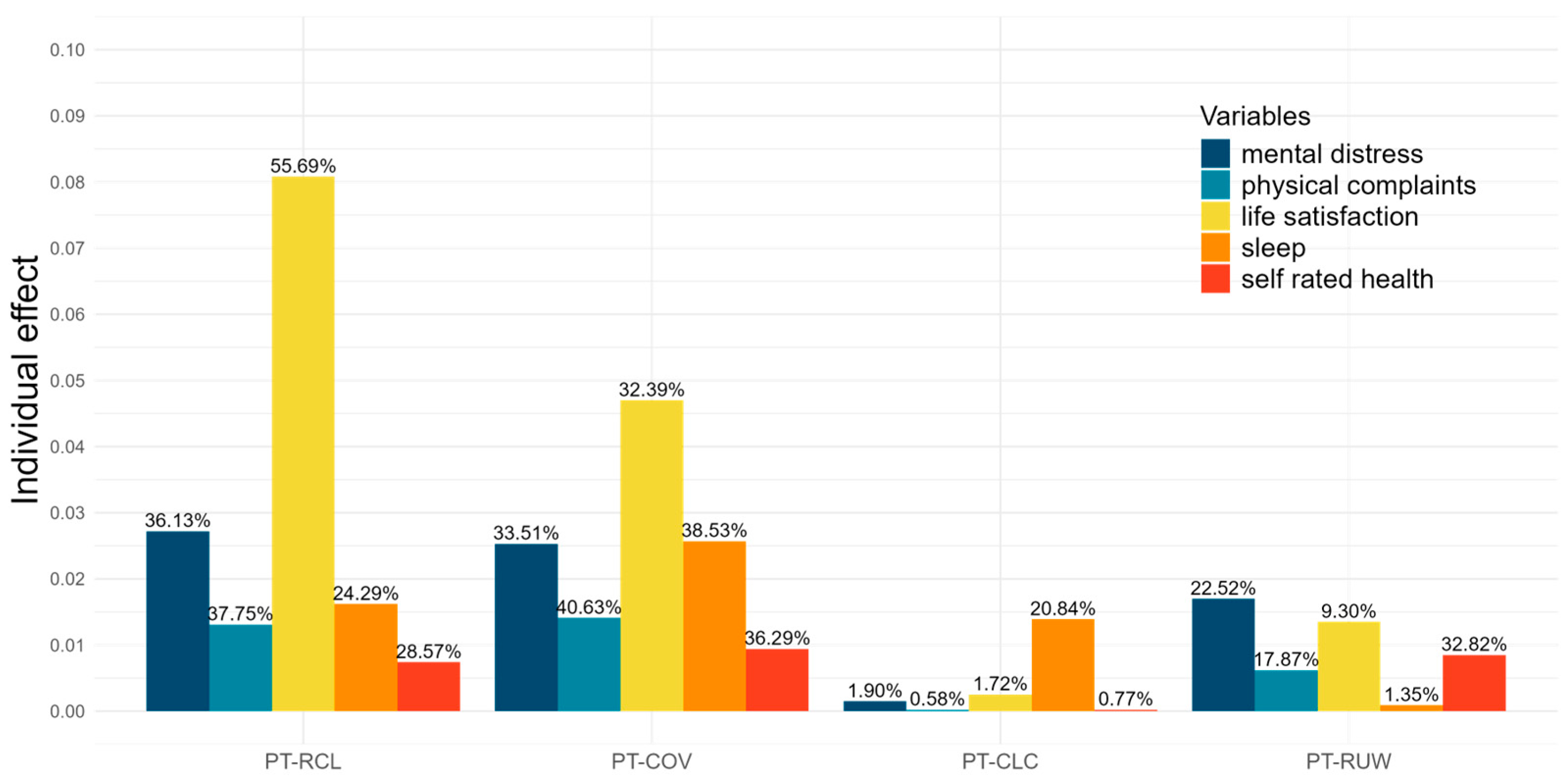

3.4. Total Variance Explained and Decomposition of Explained Variance with Hierarchical Partitioning

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yen, V.Y.-C.; Salmon, C.T. Further explication of mega-crisis concept and feasible responses. SHS Web Conf. 2017, 33, 00034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, R. The Mental Health Consequences of the 1985 Earthquakes in Mexico. Int. J. Ment. Health 1990, 19, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbay, F.; Auf der Heyde, T.; Reissman, D.; Sharma, V. The Enduring Mental Health Impact of the September 11th Terrorist Attacks. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 36, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, W.M.; Davey, G.C.L. The psychological impact of negative TV news bulletins: The catastrophizing of personal worries. Br. J. Psychol. 1997, 88, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uvais, N.A. Disaster-related media exposure and its impact on mental health. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 448–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozenova, M.I.; Ekimova, V.I.; Ognev, A.S.; Likhacheva, E.V. Fear as a mental health crisis in the context of global risks and changes. J. Mod. Foreign Psychol. 2021, 10, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A. Sustaining Good Mental Health in the Face of Health and Political Crisis. Int. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 9, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Strategy and Higher Leadership. The 12th Security Report. A Study on Internal and External Security in Germany in 2021. Unpublished Data. 2021. Available online: https://www.sicherheitsreport.net/sicherheitsreport-2021/ (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Centre for Strategy and Higher Leadership. The 14th Security Report. A Study on Internal and External Security in Germany in 2023. Unpublished Data. Available online: https://www.sicherheitsreport.net/sicherheitsreport-2023/ (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The Impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: A Systematic Descriptive Review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H.; White, P.; Cotton, J.; McManus, S. Flood- and Weather-Damaged Homes and Mental Health: An Analysis Using England’s Mental Health Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.J.; Clayton, S. The Psychological Impacts of Global Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogunbode, C.A.; Pallesen, S.; Böhm, G.; Doran, R.; Bhullar, N.; Aquino, S.; Marot, T.; Schermer, J.A.; Wlodarczyk, A.; Lu, S.; et al. Negative emotions about climate change are related to insomnia symptoms and mental health: Cross-sectional evidence from 25 countries. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bonanno, G.A. Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S51–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shevlin, M.; Butter, S.; McBride, O.; Murphy, J.; Gibson-Miller, J.; Hartman, T.K.; Levita, L.; Mason, L.; Martinez, A.P.; McKay, R.; et al. Refuting the myth of a ‘tsunami’ of mental ill-health in populations affected by COVID-19: Evidence that response to the pandemic is heterogeneous, not homogeneous. Psychol. Med. 2021, 53, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chudzicka-Czupała, A.; Tee, M.L.; Núñez, M.I.L.; Tripp, C.; Fardin, M.A.; Habib, H.A.; Tran, B.X.; Adamus, K.; Anlacan, J.; et al. A chain mediation model on COVID-19 symptoms and mental health outcomes in Americans, Asians and Europeans. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DESTATIS. Monthly Reports on Cause of Death Statistics with a Focus on COVID-19 Deaths; DESTATIS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, K.R.; Bhui, K.; Katona, C. Mental health responses in countries hosting refugees from Ukraine. BJPsych Open 2022, 8, e87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottschick, C.; Diexer, S.; Massag, J.; Klee, B.; Broda, A.; Purschke, O.; Binder, M.; Sedding, D.; Frese, T.; Girndt, M.; et al. Mental health in Germany in the first weeks of the Russo-Ukrainian war. BJPsych Open 2023, 9, e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massag, J.; Diexer, S.; Klee, B.; Costa, D.; Gottschick, C.; Broda, A.; Purschke, O.; Opel, N.; Binder, M.; Sedding, D.; et al. Anxiety, depressive symptoms, and distress over the course of the war in Ukraine in three federal states in Germany. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1167615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharbert, J.; Humberg, S.; Kroencke, L.; Reiter, T.; Sakel, S.; ter Horst, J.; Utesch, K.; Gosling, S.D.; Harari, G.; Matz, S.C.; et al. Psychological well-being in Europe after the outbreak of war in Ukraine. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liadze, I.; Macchiarelli, C.; Mortimer-Lee, P.; Sanchez Juanino, P. Economic costs of the Russia-Ukraine war. World Econ. 2023, 46, 874–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DESTATIS. Price Statistics—Consumer Price Index in Germany; DESTATIS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman, A. Reconsidering the Relationship between Age and Financial Strain among Older Adults. Soc. Ment. Health 2014, 4, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, N.; Guariglia, A.; Moore, P.; Xu, F.; Al-Janabi, H. Financial stress and depression in adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierman, A.; Upenieks, L.; Lee, Y. Perceptions of Increases in Cost of Living and Psychological Distress Among Older Adults. J. Aging Health 2023, 36, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimt, F.; Jacobi, C.; Brähler, E.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Zenger, M.; Berth, H. Insomnia symptoms in adulthood. Prevalence and incidence over 25 years. Sleep Med. 2023, 109, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalbach, B.; Schmalbach, I.; Kasinger, C.; Petrowski, K.; Brähler, E.; Zenger, M.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Richter, E.P.; Berth, H. Psychological and Socio-Economical Determinants of Health: The Case of Inner German Migration. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 691680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, J.; Zenger, M.; Brähler, E.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Berth, H. Der G-Score—Ein Screeninginstrument zur Erfassung der subjektiven körperlichen Gesundheit. PPmP Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2018, 68, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berth, H.; Förster, P.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Balck, F.; Brähler, E. Arbeitslosigkeit und psychische Belastung. Ergebnisse einer Längsschnittstudie 1991 bis 2004. Z. Med. Psychol. 2006, 15, 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, C.D.; Stanton, B.-A.; Niemcryk, S.J.; Rose, R.M. A scale for the estimation of sleep problems in clinical research. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1988, 41, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, E.P.; Brähler, E.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Zenger, M.; Berth, H. The long-lasting impact of unemployment on life satisfaction: Results of a longitudinal study over 20 years in East Germany. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierlein, C.; Kovaleva, A.; László, Z.; Kemper, C.; Rammstedt, B. Eine Single-Item-Skala zur Erfassung der Allgemeinen Lebenszufriedenheit: Die Kurzskala Lebenszufriedenheit-1 (L-1); GESIS: Mannheim, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Helmert, U. Subjektive Einschätzung der Gesundheit und Mortalitätsentwicklung. Das Gesundheitswesen 2003, 65, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, X.; Wu, M.; Yan, X.; He, J. The relationship between self-rated health and objective health status: A population-based study. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorem, G.; Cook, S.; Leon, D.A.; Emaus, N.; Schirmer, H. Self-reported health as a predictor of mortality: A cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and observation time. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idler, E.L.; Benyamini, Y. Self-Rated Health and Mortality: A Review of Twenty-Seven Community Studies. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1997, 38, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Edwards, L.J.; Maldonado-Molina, M.M.; Komro, K.A.; Muller, K.E. Real longitudinal data analysis for real people: Building a good enough mixed model. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J.D.; Willett, J.B. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; ISBN 0195152964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, R.; Preez, P.D.; Stuart-Hill, G.; Chris Weaver, L.; Jago, M.; Wegmann, M. Factors affecting intraspecific variation in home range size of a large African herbivore. Landsc. Ecol. 2012, 27, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, T.M.; Yates, C.J.; Byrne, M.; Nistelberger, H.M.; Williams, M.R.; Coates, D.J. Complex interactions between remnant shape and the mating system strongly influence reproductive output and progeny performance in fragmented populations of a bird-pollinated shrub. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 164, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.; Haßler, J.; Jost, P. Die Qualität der Medienberichterstattung über den Ukraine-Krieg; Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz: Mainz, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koivumaa-Honkanen, H.; Kaprio, J.; Honkanen, R.J.; Viinamäki, H.; Koskenvuo, M. The stability of life satisfaction in a 15-year follow-up of adult Finns healthy at baseline. BMC Psychiatry 2005, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ghose, B.; Tang, S. Effect of financial stress on self-rereported health and quality of life among older adults in five developing countries: A cross sectional analysis of WHO-SAGE survey. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mărcău, F.C.; Peptan, C.; Gorun, H.T.; Băleanu, V.D.; Gheorman, V. Analysis of the impact of the armed conflict in Ukraine on the population of Romania. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 964576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Lu, Y. Model selection in linear mixed effect models. J. Multivar. Anal. 2012, 109, 109–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B.; Beierlein, C. Can’t we make it any shorter? The limits of personality assessment and ways to overcome them. J. Individ. Differ. 2014, 35, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; ISBN 978-3-662-64761-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Gender (in %) | |

| Male | 45.5 |

| Female | 54.5 |

| Age (mean) | 49.9 |

| Children (in %) | 80.4 |

| Number of children (mean) | 1.8 |

| Family status (in %) | |

| Married, living together | 57.0 |

| Married, living separately | 3.5 |

| Single | 27.2 |

| Divorced | 10.1 |

| Widowed | 2.2 |

| Steady Partner | 81.8 |

| Occupational Status (in %) | |

| Worker | 18.8 |

| Employee | 62.1 |

| Self-employed | 9.4 |

| Housewife/Househusband | 0.6 |

| Civil servant | 5.0 |

| Unemployed | 1.9 |

| Other | 2.2 |

| Net household Income in € (median) | 3500 to 3999 |

| Current Residence (in %) | |

| Lives in West Germany | 21.3 |

| Lives abroad | 2.8 |

| Lives in East Germany | 75.8 |

| Variable | W32 (2021) | W33 (2022) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| physical complaints, mean, (0–12) | 3.56 | 3.76 | 1.47 | 0.143 |

| mental distress, mean, (0–8) | 1.07 | 1.29 | 3.22 | 0.001 ** |

| sleep problems, mean, (0–20) | 4.87 | 6.27 | 3.91 | <0.001 *** |

| Life Satisfaction, mean, (0–4) | 1.28 | 1.34 | 1.16 | 0.249 |

| Self-rated health, mean, (0–4) | 1.42 | 1.47 | 0.78 | 0.436 |

| PT-RCL, mean, (0–3) | 1.95 | 2.44 | 12.49 | <0.001 *** |

| PT-COV, mean, (0–3) | 1.86 | 1.46 | −6.44 | <0.001 *** |

| PT-CLC, mean, (0–3) | 1.77 | 1.71 | −1.55 | 0.123 |

| PT-RUW, mean, (0–3) | 2.09 |

| Estimates | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical complaints | time | 0.212 | 0.135 | 1.571 | 0.117 |

| covariate PT-RCL | 0.308 | 0.155 | 1.983 | 0.048 * | |

| covariate PT-COV | 0.308 | 0.119 | 2.589 | 0.010 ** | |

| covariate PT-CLC | 0.038 | 0.133 | 0.289 | 0.773 | |

| covariate PT-RUW | 0.137 | 0.201 | 0.684 | 0.495 | |

| marginal R2 | 0.035 | ||||

| conditional R2 | 0.681 | ||||

| Mental distress | time | 0.294 | 0.086 | 3.410 | <0.001 *** |

| covariate PT-RCL | 0.284 | 0.010 | 2.844 | 0.005 ** | |

| covariate PT-COV | 0.269 | 0.076 | 3.530 | <0.001 *** | |

| covariate PT-CLC | 0.030 | 0.086 | 0.352 | 0.725 | |

| covariate PT-RUW | 0.180 | 0.130 | 1.389 | 0.165 | |

| marginal R2 | 0.075 | ||||

| conditional R2 | 0.703 | ||||

| Sleep problems | time | 1.172 | 0.288 | 4.074 | <0.001 *** |

| covariate PT-RCL | 0.631 | 0.319 | 1.976 | 0.049 * | |

| covariate PT-COV | 0.818 | 0.243 | 3.361 | <0.001 *** | |

| covariate PT-CLC | 0.651 | 0.270 | 2.412 | 0.016 * | |

| covariate PT-RUW | −0.132 | 0.387 | −0.341 | 0.733 | |

| marginal R2 | 0.067 | ||||

| conditional R2 | 0.691 | ||||

| Life satisfaction | time | −0.079 | 0.005 | −1.551 | 0.122 |

| covariate PT-RCL | −0.298 | 0.051 | −5.882 | <0.001 *** | |

| covariate PT-COV | −0.170 | 0.041 | −4.182 | <0.001 *** | |

| covariate PT-CLC | 0.041 | 0.041 | 0.993 | 0.321 | |

| covariate PT-RUW | 0.001 | 0.056 | 0.011 | 0.991 | |

| marginal R2 | 0.145 | ||||

| conditional R2 | 0.522 | ||||

| Self-rated health | time | −0.038 | 0.046 | −0.820 | 0.413 |

| covariate PT-RCL | −0.059 | 0.057 | −1.163 | 0.245 | |

| covariate PT-COV | −0.082 | 0.039 | −2.072 | 0.039 * | |

| covariate PT-CLC | 0.012 | 0.043 | 0.244 | 0.807 | |

| covariate PT-RUW | −0.074 | 0.063 | −1.187 | 0.236 | |

| marginal R2 | 0.026 | ||||

| conditional R2 | 0.622 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Richter, E.P.; Brähler, E.; Zenger, M.; Stöbel-Richter, Y.; Emmerich, F.; Junghans, J.; Krause, J.; Irmscher, L.; Berth, H. Compounded Effects of Multiple Global Crises on Mental Health: A Longitudinal Study of East German Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164754

Richter EP, Brähler E, Zenger M, Stöbel-Richter Y, Emmerich F, Junghans J, Krause J, Irmscher L, Berth H. Compounded Effects of Multiple Global Crises on Mental Health: A Longitudinal Study of East German Adults. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(16):4754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164754

Chicago/Turabian StyleRichter, Ernst Peter, Elmar Brähler, Markus Zenger, Yve Stöbel-Richter, Franziska Emmerich, Julia Junghans, Juliana Krause, Lisa Irmscher, and Hendrik Berth. 2024. "Compounded Effects of Multiple Global Crises on Mental Health: A Longitudinal Study of East German Adults" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 16: 4754. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13164754