Abstract

The purpose of this work was a comparative metabolomic study of extracts of from Siberian breeds of the Solanum tuberosum L.: Tuleevsky, Kuznechanka, Memory of Antoshkina, Tomichka, Hybrid 15/F-2-13, Hybrid 22103-10, Hybrid 17-5/6-11, and Sinilga from the collection of Siberian Federal Scientific Centre of Agrobiotechnology of the Russian Academy of Sciences. HPLC was used in combination with ion trap to identify target analytes in extracts of tuber part of a potato. The results showed the presence of 87 target analytes corresponding to S. tuberosum. In addition to the reported metabolites, a number of metabolites were newly annotated in S. tuberosum. There were essential amino acid L-Tryptophan, L-glutamate, L-lysine, Nordenine; flavones Ampelopsin; Chrysoeriol, Diosmetin, Diosmin, Myricetin; flavanones Naringenin and Eriodictyol-7-O-glucoside; dihydrochalcone Phlorizin; oligomeric proanthocyanidin (Epi)afzelechin-(epi)afzelechin; Shikimic acid; Hydroxyphenyllactic acid; Fraxidin; Myristoleic acid; flavan-3-ols Epicatechin, Gallocatechin, Gibberellic acid, etc.

1. Introduction

Extensive genetic diversity exists among potato germplasm, which includes around 200 wild species found in extremely varied habitats throughout the Americas []. However, only a small portion of this genetic diversity has been incorporated into modern cultivars, resulting in a narrow genetic pool. Consequently, wild species are a largely untapped resource that likely contain many novel genes useful for trait enhancement of domesticated potatoes. Relatively little is known about the extent of metabolite diversity present among potato germplasm. Metabolomics holds promise toward understanding metabolite abundance and diversity in plants. GC-MS and HPLC MS/MS metabolic profiling of a few potato cultivars has been shown to be an effective tool [,,,].

Preliminary LC-MS analysis of the seven genotypes in this study suggested glycoalkaloids were a large source of metabolite diversity. Glycoalkaloids are plant metabolites containing an oligosaccharide, a C27 steroid and a heterocyclic nitrogen component. Solanine and chaconine are thought to comprise upward of 90% of the total glycoalkaloid complement of domesticated potatoes, with chaconine often more abundant than solanine [].

The glycoalkaloid biosynthetic pathway is not fully delineated, even for the major potato glycoalkaloids, solanine and chaconine. Glycoalkaloids, derived from the mevalonate path-way via cholesterol, occur throughout the tuber but are primarily synthesized in the phelloderm []. Surprisingly little has been elucidated about the genes and enzymology involved in conversion of cholesterol into the various glycoalkaloids. Identification of glycoalkaloid biosynthesis genes has enabled transgenic approaches to decrease potato glycoalkaloid content, because glycoalkaloids are typically regarded as antinutritive compounds capable of causing vomiting and other ill effects if ingested in high enough amounts []. Potatoes overexpressing a soybean sterol methyltransferase exhibited decreased amounts of both cholesterol and glycoalkaloids [].

Initial LC-MS screening suggested that among the hundreds of compounds detected in tubers, glycoalkaloid composition was particularly diverse. Potato glycoalkaloids can be divided into two general classes, those with solanidane or spirosolane aglycones, and this study focused on solanidine or solanidane-like glycoalkaloids []. Therefore, tandem mass spectrometry was used in this study for comparative small molecule profiling of eight potato varieties cultivated in the Siberian Federal Scientific Center of Agrobiotechnology of Russian Academy of Sciences.

Selection of Siberian potatoes is carried out in the conditions of a sharply continental climate of the West Siberian region of the Russian Federation and is carried out in the following areas:

- •

- Early ripeness, varieties of early and mid-early ripeness groups, because the growing season is 90–100 days;

- •

- Resistance to the most common fungal and viral diseases inherent in the region—late blight (Phytophthora infestans (Mont.) de Bary), Alternaria blight (Alternaria solani (Ell.Et Matr) Sor), Fusarium blight (Fusarium oxysporum Schlecht.), Rhizoctonia blight (Rhizoctonia solani J.G. Kühn) and viruses;

- •

- Stably high productivity;

- •

- High consumer and culinary qualities;

- •

- Suitability for mechanized cultivation;

- •

- Keeping quality of tubers during storage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The object of the study was the eight varieties of Siberian S. tuberosum of breeding varieties obtained as a result of many years of research from the collection of Siberian Federal Scientific Centre of Agrobiotechnology (Krasnoobsk) of Russian Academia of Science. There were varieties: Tuleevsky, Kuznechanka, Memory of Antoshkina, Tomichka, Hybrid 15/F-2-13, Hybrid 22103-10, Hybrid 17-5/6-11, Sinilga. The varieties of studied potatoes from Siberian Federal Scientific Centre of Agrobiotechnology are presented on the Table 1.

Table 1.

The description of potato varieties from Siberian Federal Scientific Centre of Agrobiotechnology.

The potato tubers were harvested at the end of September 2021. All samples morphologically corresponded to the pharmacopoeial standards of the State Pharmacopoeia of the Russian Federation [].

2.2. Chemicals and Reagents

HPLC-grade acetonitrile C2H3N was used as a mobile phase for HPLC process (Fisher Scientific, Southborough, UK), MS-grade formic acid CH2O2 used for liquid chromatography process (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany).

Ultrapure water was produced using SIEMENS ULTRA clear equipment (SIEMENS water technologies, Germany), all reagents used in chemical research were also of analytical purity.

2.3. Fractional Maceration

Fractional maceration technique was applied to obtain highly concentrated extracts []. Maceration for small scale extraction usually consists of several steps. Grinding plant materials (500 g of tuber part of a potato) to very small particles (3 × 3 mm) is used to increase the surface area for proper mixing with the solvent. Also, during the maceration process, an appropriate solvent is added to the extraction vessel (methyl alcohol of reagent grade).

Next, the liquid is filtered and the remaining pomace, which is the solid residue of this extraction process, is squeezed out to extract a large amount of occluded solutions. The resulting filtered and squeezed liquid is also later mixed and filtered from impurities.

The solid–solvent ratio was 1:20. The infusion of each part of the extractant lasted 7 days at room temperature.

2.4. Liquid Chromatography

Shimadzu LC-20 Prominence HPLC (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a UV sensor and C18 silica reverse phase column, 4.6 × 150 mm, particle size: 2.7 μm (Ascentis Express C18, Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich Tokyo, Japan) used to do high performance liquid chromatography analysis. The gradient elution program with two mobile phases (H2O, deionized water; C2H3N, acetonitrile with formic acid CH2O2 0.1% v/v) was as follows: 0–2 min, 0% C2H3N; 2–50 min, 0–100% C2H3N; control washing 50–60 min 100% C2H3N. Formic acid in this case was used as a mobile phase component in high performance liquid chromatography analysis to separate hydrophobic macromolecules such as peptides, proteins and more complex structures. The entire HPLC analysis was performed with a UV–vis detector SPD- 20A (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) at a wavelength of 230 nm for identification compounds; the temperature was 50 °C, and the total flow rate 0.25 mL min−1. The injection volume was 10 μL. In this study, liquid chromatography was combined into one analytical unit with a mass spectrometric ion trap for the identification of chemical compounds.

2.5. Mass Spectrometry

MS analysis was performed on an ion trap amaZon SL (Bruker Daltoniks, Bremen, Germany) equipped with an ESI source in negative ion mode. The optimized parameters were obtained as follows: ionization source temperature: 70 °C, gas flow: 4 l/min, nebulizer gas (atomizer): 7.3 psi, capillary voltage: 4500 V, end plate bend voltage: 1500 V, fragmentary: 280 V, collision energy: 60 eV. An ion trap was used in the scan range m/z 100 −1.700 for MS and four-stage ion separation mode (MS/MS mode). Data collection was controlled by Windows software for Bruker Daltoniks. All experiments were repeated four times.

3. Results

Eight of the extracts of tuber part of a potato have been selected. All of them have a rich bioactive composition, characterized by a large presence of a complex of flavonoids, steroidal alkaloids, phenolic amines, oxylipins, etc. There were eight extracts from Siberian S. tuberosum L.: Tuleevsky, Kuznechanka, Memory of Antoshkina, Tomichka, Hybrid 15/F-2-13, Hybrid 22103-10, Hybrid 17-5/6-11, and Sinilga from the collection of Siberian Federal Scientific Centre of Agrobiotechnology of the Russian Academy of Science.

High accuracy mass spectrometric data were recorded on an ion trap amaZon SL BRUKER DALTONIKS equipped with an ESI source in the mode of negative-positive ions. The combination of both ionization modes (positive and negative) in MS full scan mode gave extra certainly to the molecular mass determination (Figure 1). The positive and negative ion modes provide the highest sensitivity and results in limited fragmentation, making it most suited to infer the molecular mass of the separated polyphenols, especially in cases where concentration is low. By comparing the m/z values, the RT and the fragmentation patterns with the MS2 spectral data taken from the literature or to search the data bases (MS2T, MassBank, HMDB). A unifying system table was compiled of the molecular masses of the target analytes isolated from the MeOH-extract of S. tuberosum for ease of identification (Appendix A Table A1). The 87 target analytes shown in Table 1 belong to different polyphenolic families: flavones, flavonols, flavan-3-ols, flavanones, hydroxycinnamic acids, hydroxybenzoic acids, stilbenes, tannins and belong to glycoalkaloids.

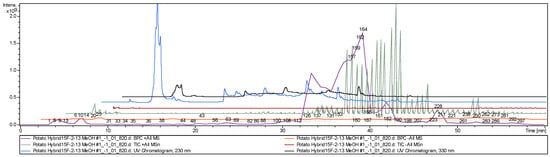

Figure 1.

Chemical profiles of the S. tuberosum L. (variety Hybrid 15/F-2-13) sample represented total ion chromatogram from MeOH-extract.

In addition to the reported metabolites, a number of metabolites were newly annotated in Siberian S. tuberosum L. There were essential amino acid L-Tryptophan; stilbene Oxyresveratrol; flavones Chrysoeriol, Diosmetin, Diosmin, Myricetin, Ampelopsin; dihydrochalcone Phlorizin; Shikimic acid; Hydroxyphenyllactic acid; Fraxidin; Myristoleic acid; flavanone Naringenin; flavan-3-ols Epicatechin, Gallocatechin, Gibberellic acid, etc.

The total ion chromatogram of tandem mass spectrometry of the S. tuberosum L. (variety Hybrid 15/F-2-13) sample is represented on Figure 1. Purple line—base peek chromatogram of positive ion signal intensity; red line—base peek chromatogram of negative ion signal intensity; light green line—total intensity of positive ions; brown line—total intensity of negative ions; blue line—UV chromatogram (wavelength 230 ηm); black line—UV chromatogram (wavelength 330 ηm). The obtained mass spectrometric data make it possible to compile a detailed table of the presence of identified compounds in different varieties of the Siberian S. tuberosum, which further makes it possible to construct comparative Venn diagrams. (Appendix A Table A2).

4. Discussion

The results presented in Table A2 (Appendix A) clearly show that the variety Hybrid 22103-10 provided the highest polyphenol content, the variety Memory of Antoshkina, Hybrid 15/F-2-13, and Hybrid 17-5/6-11 provided the lowest polyphenol content. In turn, analyzing Table A2 (Appendix A), the highest content of steroidal alkaloids was shown by potato tubers of the variety Hybrid 22103-10, and the lowest content was shown by the varieties Hybrid 15/F-2-13, Hybrid 17-5/6-11, and Tomichka.

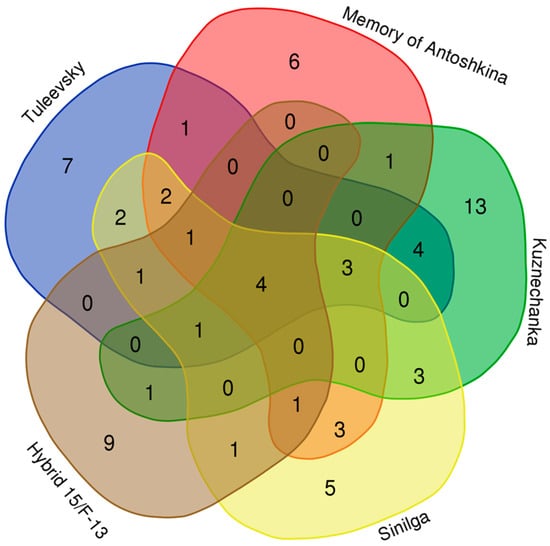

The results of studies for all bioactive substances, identified from MeOH extracts of S. tuberosum are presented in the Venn diagram (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram comparing the composition of isolated bioactive components in potato samples “Tuleevsky”, “Memory of Antoshkina”, “Kuznechanka’’, “Sinilga”, “Hybrid 15/F-2-13”.

The detailed interpretation of the identified compounds in potato varieties is presented in Table 2. Also in this table, repeated matches for identified substances in different varieties of potatoes are well traced.

Table 2.

The detailed interpretation of the identified bioactive compounds in potato varieties.

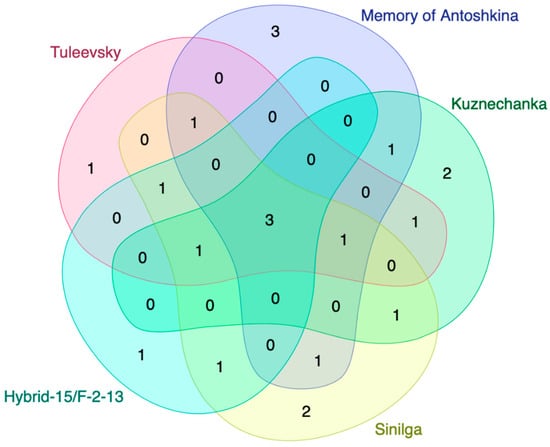

The results of studies for all steroidal alkaloids are presented in the Venn diagram (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Venn diagram comparing the composition of isolated steroid alkaloids in potato samples “Tuleevsky”, “Memory of Antoshkina”, “Kuznechanka’’, “Sinilga”, “Hybrid 15/F-2-13”.

The detailed interpretation of the identified steroidal alkaloids in potato varieties is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Detailed interpretation of the identified steroidal alkaloids in potato varieties.

The applied LC gradient of acetonitrile in water permitted to resolve all steroid alkaloid glycosides N° 70–87 (Appendix A Table A2) during reasonable short time.

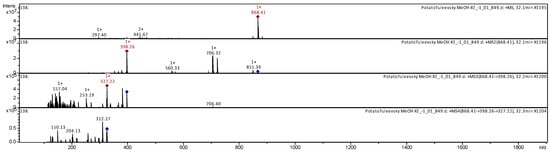

Monitoring the elution profile of the compounds N° 70–87 was much more easier from single ion chromatograms of protonated molecules [M + H]+, than in total ion chromatogram (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). The resolution of the particular peaks of steroid alkaloid glycosides was satisfactory in the applied LC gradient and identification of the compounds on the basis of the registered mass spectra was unambiguous. In the extracts α-chaconine and α-solanine were identified as major glycoalkaloid components, their peaks were easily recognized in the total ion current (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

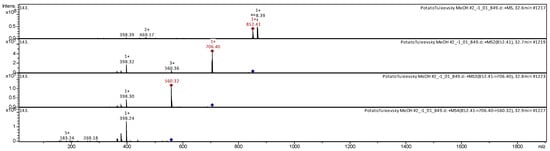

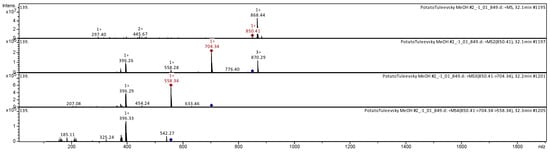

Figure 4.

CID-spectrum of α-solanine from extracts of S. tuberosum (variety Tuleevsky), m/z 868.41.

Figure 5.

CID-spectrum of α-chaconine from extracts of S. tuberosum (variety Tuleevsky), m/z 852.41.

Figure 6.

CID-spectrum of Dehydrochaconine [Solanidine dehydrodimer conjugated with chacotriose] from extracts of S. tuberosum (variety Tuleevsky), m/z 850.41.

Figure 7.

CID-spectrum of Leptinine II from extracts of S. tuberosum (variety Tuleevsky), m/z 884.34.

Figure 4 shows an example of decoding the spectrum of the steroidal alkaloid α-solanine from an ion chromatogram obtained by tandem mass spectrometry. The [M + H]+ ion produces four product ions at m/z 398.26, m/z 560.33, m/z 706.32, and at m/z 851.39 (Figure 4). A fragment ion at m/z 398.26 gives rise to three daughter ions at m/z 327.22, m/z 253.19, and m/z 157.04. A fragment ion at m/z 327.22 gives rise to three daughter ions at m/z 312.27, m/z 204.13, and m/z 150.13. This compound is identified in scientific articles as α-solanine, for example in S. tuberosum [,,,].

Figure 5 shows an example of decoding the spectrum of the steroidal alkaloid α-chaconine from an ion chromatogram obtained by tandem mass spectrometry. The [M + H]+ ion produces three product ions at m/z 706.4, m/z 560.36, and at m/z 398.32 (Figure 5). A fragment ion at m/z 706.4 gives rise to two daughter ions at m/z 560.32, and m/z 398.3. A fragment ion at m/z 560.32 gives rise to three daughter ions at m/z 398.24, m/z 269.18, and m/z 183.24. This compound is identified in scientific articles as α-chaconine, for example in S. tuberosum [,,,].

In the mass spectra [M + H]+ ions at m/z 868 and 884 were observed. Four additional peaks of triglycosides described by us, as glycosidic conjugates of dehydrosolanidine were also identified, their protonated molecular ions [M + H]+ were detected at m/z 850 and m/z 866, respectively (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7).

In the mass spectra of all triglycosides [M + H]+ ions and fragments were observed, formed after consecutive cleavage of glycosidic bonds between sugars and sugar and aglycone. In the first step of the fragmentation pathway of studied compounds (Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7) cleavage of both sugar rings on the nonreducing end was observed. In the mass spectra of steroid alkaloid glycosides linked with solatriose in the first step of fragmentation elimination of glucose ([M + H]+ − 162) or rhamnose ([M + H]+ − 146) was recorded. Due to simultaneous co-elution from LC column more than one secondary metabolite in the mass spectra were present but verification of the steroid alkaloid glycosides presence in the analyzed samples was possible. On the basis of single ion chromatograms for [M + H]+ and fragment ions unambiguous identification of compounds of interest was achieved.

5. Conclusions

Scientific studies in this work have clearly shown the presence of a large number of putative target analytes from extracts of from Siberian S. tuberosum L.: Tuleevsky, Kuznechanka, Memory of Antoshkina, Tomichka, Hybrid 15/F-2-13, Hybrid 22103-10, Hybrid 17-5/6-11, and Sinilga from the collection of Siberian Federal Scientific Centre of Agrobiotechnology of Russian Academia of Science. HPLC in combination with a BRUKER DALTONIKS ion trap was used to identify target analytes in extracts of tuber part of a potato. The results showed the presence of 87 target analytes corresponding to S. tuberosum. In addition to the reported metabolites, a number of metabolites were newly annotated in S. tuberosum. There were essential amino acid L-Tryptophan, L-glutamate, L-lysine, Nordenine; flavones Ampelopsin; Chrysoeriol, Diosmetin, Diosmin, Myricetin; flavanones Naringenin and Eriodictyol-7-O-glucoside; dihydrochalcone Phlorizin; oligomeric proanthocyanidin (Epi)afzelechin-(epi)afzelechin; Shikimic acid; Hydroxyphenyllactic acid; Fraxidin; Myristoleic acid; flavan-3-ols Epicatechin, Gallocatechin, Gibberellic acid, etc.

This study will help to further constructively navigate the introduction of new potato varieties and hybrids in order to obtain certain consumer qualities. In particular, it is now quite clear that in the breeding of new varieties of potatoes, it is necessary to focus on reducing the total proportion of steroidal alkaloids, since they worsen the quality of the product. In turn, the extended presence of compounds of the polyphenol group improves the taste and useful properties of experimental potato samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and A.Z.; methodology V.K. (Valentina Kulikova) and K.G.; validation, A.Z. and K.G.; formal analysis, L.B., T.B. and M.R.; investigation, N.P. and V.K. (Vera Khodaeva); resources, K.G.; data curation; writing—original draft preparation—M.R.; writing—review and editing M.R. and K.G.; visualization, M.R.; supervision, K.G.; project administration, K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Decree No. 220 by the Government of the Russian Federation (Mega-grant No. 220-2961-3099).

Institutional Review Board Statement

No applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The target analytes isolated from the MeOH-extract of S. tuberosum L.

Table A1.

The target analytes isolated from the MeOH-extract of S. tuberosum L.

| No | Class of Compounds | Identification | Formula | Calculated Mass | Observed Mass [M − H]− | Observed Mass [M + H]+ | MS/MS Stage 1 Fragmentation | MS/MS Stage 2 Fragmentation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POLYPHENOLS | |||||||||

| 1 | Flavone | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 270.2369 | 271 | 243 | 230 | Hedyotis diffusa []; Cirsium japonicum []; Triticum aestivum L. [] | |

| 2 | Flavone | Chrysoeriol [Chryseriol] | C16H12O6 | 300.2629 | 301 | 269; 169 | 241 | Triticum aestivum L. []; Rice []; Mentha [] | |

| 3 | Flavone | Diosmetin | C16H12O6 | 300.2629 | 301 | 273; 169 | 241 | Cirsium japonicum []; Mentha [] | |

| 4 | Flavone | Myricetin | C15H10O8 | 318.2351 | 319 | 289; 260; 219; 173 | 261; 191 | Vitis vinifera []; Vaccinium macrocarpon []; F. glaucescens [] | |

| 5 | Flavone | Ampelopsin | C15H12O8 | 320.251 | 321 | 304; 287; 247; 129 | 193; 113 | Impatients glandulifera Royle []; Rhus coriaria [] | |

| 6 | Flavone | 5,6-Dihydroxy-7,8,3’,4’-tetramethoxyflavone | C19H18O8 | 374.3414 | 375 | 345; 297; 275; 257; 245; 217 | 315; 257; 245 | Mentha [] | |

| 7 | Flavone | Dihydroxy tetramethoxyflavanone | C19H20O8 | 376.3573 | 377 | 345; 275 | 245 | G. linguiforme [] | |

| 8 | Flavone | Diosmin [Diosmetin-7-O-rutinoside; Barosmin; Diosimin] | C28H32O15 | 608.5447 | 609 | 591; 531 | 531 | Mentha []; F. glaucescens [] | |

| 9 | Flavonol | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 286.2363 | 287 | 278; 241; 185 | 206 | Potato leaves []; Potato []; Vitis vinifera []; Ocimum [] | |

| 10 | Flavonol | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 302.2357 | 303 | 275; 203; 163 | 245; 175 | Potato leaves []; Eucalyptus []; Triticum []; Vitis vinifera []; Tomato []; Vaccinium macrocarpon [,] | |

| 11 | Flavonol | Herbacetin | C15H10O7 | 302.2357 | 303 | 275; 203 | 245; 175 | Ocimum []; Rhodiola rosea [] | |

| 12 | Flavonol | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 316.2623 | 317 | 256 | 228; 116 | Vaccinium macrocarpon []; Eucalyptus [] | |

| 13 | Flavonol | Quercetin 3-O- glucoside | C21H20O12 | 464.3763 | 465 | 447; 279; 136 | 429; 279; 201 | Potato [,]; Vitis vinifera []; Rhus coriaria []; Lonicera japonica []; Solanaceae [] | |

| 14 | Flavonol | Myricetin-3-O-galactoside | C21H20O13 | 480.3757 | 481 | 299; 174 | 271 | Vitis vinifera []; Vaccinium macrocarpon [,]; Impatients glandulifera Royle [] | |

| 15 | Flavonol | Kaempferol diacetyl hexoside | C25H24O13 | 532.4503 | 533 | 415 | 385; 315 | A. cordifolia [] | |

| 16 | Flavonol | Quercetin glucuronide sulfate | C21H18O16S | 558.4230 | 559 | 412; 299; 186 | 394; 299; 186 | F. herrerae [] | |

| 17 | Flavonol | Quercetin malonyl dihexoside | C30H32O20 | 712.5631 | 711 | 303; 279 | 259; 205 | F. glaucescens; F. herrerae [] | |

| 18 | Flavanone | Naringenin [Naringetol; Naringenine] | C15H12O5 | 272.5228 | 273 | 255; 213; 161 | 226 | Vitis vinifera []; G. linguiforme []; Tomato [] | |

| 19 | Flavanone | Eriodictyol-7-O-glucoside | C21H22O11 | 450.3928 | 449 | 431; 413; 333; 267; 233; 140 | 356; 290; 227; 150 | Vitis vinifera []; Impatients glandulifera Royle [] | |

| 20 | Flavan-3-ol | Catechin [D-Catechol] | C15H14O6 | 290.2681 | 291 | 273; 261; 243; 231; 213; 191; 175 | 202; 157 | Eucalyptus []; Triticum []; Vaccinium macrocarpon []; Potato [] | |

| 21 | Flavan-3-ol | Epicatechin | C15H14O6 | 290.2681 | 291 | 261; 175 | 175; 157 | Vitis vinifera []; C. edulis []; Eucalyptus []; Vaccinium macrocarpon []; Rubus occidentalis [] | |

| 22 | Flavan-3-ol | Gallocatechin | C15H14O7 | 306.2675 | 307 | 277; 207 | 247; 159 | G. linguiforme []; Solanaceae [] | |

| 23 | Oligomeric proanthocyanidin | Epiafzelechin [(epi)Afzelechin] | C15H14O5 | 274.2687 | 275 | 245; 175 | 175; 127 | A. cordifolia; F. glaucescens; F. herrerae [] | |

| 24 | Oligomeric proanthocyanidin | (Epi)Afzelechin-(epi)afzelechin | C30H24O10 | 544.5056 | 545 | 535; 362; 301 | 359; 227 | A. cordifolia, C. edulis [] | |

| 25 | Anthocyanin | Petunidin | C16H13O7+ | 317.2702 | 318 | 300; 256 | 212; 112 | A. cordifolia; C. edulis [] | |

| 26 | Dihydrochalcone | Phlorizin [Phloridzin; Phlorizoside] | C21H24O10 | 436.4093 | 437 | 275; 329 | 245; 176 | Potato []; Vitis vinifera []; A.cordifolia []; Eucalyptus [] | |

| 27 | Hydroxycinammic acid | p-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 164.16 | 165 | 147 | 119 | Potato []; Tomato []; Vaccinium macrocarpon []; Rubus occidentalis [] | |

| 28 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Chlorogenic acid [3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid] | C16H18O9 | 354.3087 | 353 | 191 | 127; 171 | Potato leaves []; Vaccinium macrocarpon []; tomato []; Potato [,,,] | |

| 29 | Hydroxybenzoic acid (Phenolic acid) | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid [PHBA; Benzoic acid; p-Hydroxybenzoic acid] | C7H6O3 | 138.1207 | 139 | 137 | 129 | Potato []; Vitis vinifera []; Triticum []; Vigna unguiculata []; Mentha [] | |

| 30 | Hydroxybenzoic acid (Phenolic acid) | Salvianolic acid G | C18H12O7 | 340.2837 | 341 | 323; 273; 137 | 275; 176 | Mentha [] | |

| 31 | Hydroxycoumarin | Fraxidin | C11H10O5 | 222.1941 | 208; 135 | 189 | Rat plasma [] | ||

| OTHERS | |||||||||

| 32 | L-alpha amino acid | L-Pyroglutamic acid [Pidolic acid; 5-Oxo-L-Proline] | C5H7NO3 | 129.1140 | 130 | 112 | Potato leaves [] | ||

| 33 | Amino acid | Leucine [(S)-2-Amino-Methylpentanoic acid] | C6H13NO2 | 131.1729 | 132 | 129 | Potato leaves []; Vigna unguiculata [] | ||

| 34 | Amino acid | L-Glutamate | C5H7NO4 | 145.1134 | 146 | Lonicera japonica [] | |||

| 35 | Amino acid | L-Lysine | C6H14N2O2 | 146.1876 | 147 | 130 | Lonicera japonica [] | ||

| 36 | Amino acid | Phenylalanine [L-Phenylalanine] | C9H11NO2 | 165.1891 | 166 | 120 | Potato leaves []; G. linguiforme []; Vigna unguiculata []; Passiflora incarnata [] | ||

| 37 | Amino acid | Nordenine | C10H15NO | 165.2322 | 166 | 149; 120 | 139; 120 | A. cordifolia [] | |

| 38 | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Shikimic acid [L-Schikimic acid] | C7H10O5 | 174.1513 | 175 | 157; 130; 112 | 140; 126; 112 | A. cordifolia []; Red wines [] | |

| 39 | Monobasic carboxylic acid | Hydroxyphenyllactic acid | C9H10O4 | 182.1733 | 182 | 165; 136 | 147 | Mentha [] | |

| 40 | Polyhydroxycarboxylic acid | Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 192.1666 | 191 | 173; 129; 111 | Potato leaves []; Potato [] | ||

| 41 | Tricarboxylic acid | Citric acid [Anhydrous; Citrate] | C6H8O7 | 192.1235 | 191 | 111; 173 | Potato leaves []; Vigna unguiculata [] | ||

| 42 | Trans-cinnamic acid | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 194.184 | 195 | 193; 112 | Potato [,]; Vaccinium macrocarpon [] | ||

| 43 | Essential amino acid | L-Tryptophan [Tryptophan; (S)-Tryptophan] | C11H12N2O2 | 204.2252 | 205 | 188 | 146; 170 | Vigna unguiculata []; Passiflora incarnata []; Strawberry [] | |

| 44 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Dodecatetraenedioic acid [2,4,8,10-Dodecateraenedioic acid] | C12H14O4 | 222.2372 | 223 | 208; 163; 135 | 190 | F. herrerae [] | |

| 45 | Carboxylic acid | Myristoleic acid [Cis-9-Tetradecanoic acid] | C14H26O2 | 226.3550 | 227 | 209; | 138; 127 | F. glaucescens [] | |

| 46 | Benzoic acid | 3,4-Diacetoxybenzoic acid | C10H11O6 | 238.1935 | 239 | 222; 151 | 123 | Potato leaves []; Triticum aestivum L. [] | |

| 47 | Phenolic amine | N-Caffeoylputrescine | C13H18N2O3 | 250.2936 | 251 | 223; 151 | 177 | Potato leaves []; Potato [] | |

| 48 | Phenolic amine | N-feruloylputrescine | C14H20N2O3 | 264.3202 | 265 | 248; 177; 114 | 177; 145 | Potato [] | |

| 49 | Omega-3 fatty acid | Stearidonic acid | C18H28O2 | 276.4137 | 277 | 248; 201; 132 | 218; 189 | Salviae Miltiorrhizae [] | |

| 50 | Phenylpropanoid | Triandrin [Sachaliside] | C15H20O7 | 312.3151 | 311 | 293; 201; 171 | 265; 185 | Potato leaves [] | |

| 51 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Octadecanedioic acid [1,16-Hexadecanedicarboxylic acid] | C18H34O4 | 314.4602 | 315 | 280; 199; 127 | 135 | F. glaucescens [] | |

| 52 | Unsaturated essential fatty acid | Oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid | C20H30O3 | 318.4504 | 319 | 277 | 259; 165 | F. potsii [] | |

| 53 | Fructose-phenylalanine | C15H21NO7 | 327.3297 | 328 | 169; 291 | 140 | Potato leaves [] | ||

| 54 | Higher-molecular-weight carboxylic acid | 9,10-Dihydroxy-8-oxooctadec-12-enoic acid | C18H32O5 | 328.4437 | 327 | 229; 171; 127 | 153 | Bituminaria []; Broccoli []; Phyllostachys nigra [] | |

| 55 | Oxylipin | Epoxyoctadecane-dioic acid | C18H32O5 | 328.4437 | 327 | 171; 201; 125 | 153 | Potato leaves [] | |

| 56 | Phenolic amine | N-feruloyloctopamine | C18H19NO5 | 329.3472 | 328 | 310 | 295; 161; 135 | Potato [] | |

| 57 | Oxylipin | 13- Trihydroxy-Octadecenoic acid [THODE] | C18H34O5 | 330.4596 | 329 | 309; 229; 171; 127 | 153 | Bituminaria []; Broccoli []; Phyllostachys nigra [] | |

| 58 | Oxylipin | 9,12,13- Trihydroxy-trans-10-octadecenoic acid | C18H34O5 | 330.4596 | 329 | 171; 201; 311 | 153 | Potato leaves [] | |

| 59 | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | 3-O-caffeoylshikimic acid [3-Csa] | C16H16O8 | 336.2934 | 337 | 319; 257; 175; 112 | 257; 175 | Grataegi Fructus []; Zostera marina [] | |

| 60 | Pentacyclic diterpenoid | Gibberellic acid | C19H22O6 | 346.3744 | 347 | 284; 154 | 256 | Triticum aestivum [] | |

| 61 | Higher-molecular-weight carboxylic acid | Pentacosenoic acid | C25H48O2 | 380.6474 | 381 | 363; 263; 180 | 275; 247; 207 | F. glaucescens [] | |

| 62 | Steroidal alkaloid | Solanidine | C27H43NO | 397.6364 | 399 | 157; 383; 327; 253 | 142 | Potato [,] | |

| 63 | Sterol | Stigmasterol [Stigmasterin; Beta-Stigmasterol] | C29H48O | 412.6908 | 413 | 301 | 189 | Hedyotis diffusa []; A.cordifolia; F. pottsii []; Salvia hypargeia [] | |

| 64 | Steroidal alkaloid | Tomatidinol | C27H43NO2 | 413.6358 | 414 | 394; 272; 204 | 256; 204 | Potato []; Lucopersicon esculentum, Solanum nigrum [] | |

| 65 | Anabolic steroid | Vebonol | C30H44O3 | 452.6686 | 453 | 435; 336; 209 | 336; 226 | Rhus coriaria [] | |

| 66 | Phenolic amine | N1,N8-bis(dihydrocaffeoyl) spermidine | C25H35N3O6 | 473.5619 | 474 | 343 | 228; 315 | Potato [] | |

| 67 | Polyhydroxycarboxylic acid | 1-O-caffeoyl-5-O-feruloylquinic acid | C26H26O12 | 530.4774 | 531 | 353; 303; 230 | 337; 280; 143 | Lemon []; Senecio clivicolus [] | |

| 68 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C32H33NO8 | 559.6063 | 560 | 398; 183 | 383; 253; 213; 159; 125 | ||

| 69 | Glycoalkaloid | β-chaconine | C39H63NO10 | 705.9182 | 706 | 560; 493; 398; 307; 214 | 398; 196 | Passiflora incarnata [] | |

| 70 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C39H63NO11 | 721.9176 | 722 | 704; 560 | 396 | ||

| 71 | Glycoalkaloid | Dehydrochaconine | C45H71NO14 | 850.0435 | 850 | 704; 558; 396 | 558; 396; 272 | Potato [,] | |

| 72 | Glycoalkaloid | α-chaconine | C45H73NO14 | 852.0594 | 852 | 706; 560; 398; 253 | 560; 398 | Potato [,,,] | |

| 73 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadienol chacotriose | C45H71NO15 | 866.0429 | 866 | 720; 574; 412; 850 | 574; 412 | Potato [] | |

| 74 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadiene solatriose | C45H71NO15 | 866.0429 | 866 | 396; 558; 704 | 396; 325; 199; 166 | Potato [] | |

| 75 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidenone chacotriose | C45H71NO15 | 866.0429 | 866 | 720 | 574; 412; 254 | Potato [] | |

| 76 | Glycoalkaloid | α-solanine | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | 868 | 398; 706; 560 | 383; 327; 253; 157 | Potato [,,,] | |

| 77 | Glycoalkaloid | Leptinine I | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | 868 | 850; 704; 396 | 704; 558; 396 | Potato [] | |

| 78 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidenol chacotriose | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | 868 | 722; 560; 398 | 560; 398; 326 | Potato [] | |

| 79 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadiene solatriose | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | 868 | 706; 560; 486; 398; 327 | 560; 398; | Potato [] | |

| 80 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadienol solatriose | C45H71NO16 | 882.0423 | 882 | 412; 736; 574 | 182; 394; 341; 251 | Potato [] | |

| 81 | Glycoalkaloid | Leptinine II | C45H73NO16 | 884.0582 | 884 | 866; 704; 396 | 396; 558; 720 | Potato [] | |

| 82 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidenol solatriose | C45H73NO16 | 884.0582 | 884 | 866; 722; 396 | 396; 558; 704 | Potato [] | |

| 83 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C45H75NO16 | 886.0741 | 886 | 850; 704 | 704; 558 | ||

| 84 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C45H77NO16 | 888.0900 | 888 | 870 | 852 | ||

| 85 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C46H75NO16 | 898.0848 | 897 | 850; 704 | 704; 246 | ||

| 86 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C45H76NO17 | 903.0814 | 902 | 866; 704 | 704; 558 | ||

| 87 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C49H79NO18 | 970.1475 | 969 | 850; 704 | 704; 558; 492 |

Table A2.

The presence of identified compounds in different varieties of Siberian S. tuberosum (Variety Tuleevsky—light green; variety Memory of Antoshkina—brown; variety Kuznechanka—red; variety Sinilga—violet; variety Hybrid 15/F-2-13—rose; variety Hybrid 22103-10—green; variety Hybrid 17-5/6-11—blue; variety Tomichka—light blue).

Table A2.

The presence of identified compounds in different varieties of Siberian S. tuberosum (Variety Tuleevsky—light green; variety Memory of Antoshkina—brown; variety Kuznechanka—red; variety Sinilga—violet; variety Hybrid 15/F-2-13—rose; variety Hybrid 22103-10—green; variety Hybrid 17-5/6-11—blue; variety Tomichka—light blue).

| No | Identified Compounds | Identification | Formula | Calculated Mass | Tuleevsky | Memory of Antoshkina | Kuznechanka | Sinilga | Hybrid 15/F-2-13 | Hybrid 22103-10 | Hybrid 17-5/6-11 | Tomichka |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyphenols | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Flavone | Apigenin | C15H10O5 | 270.2369 | ||||||||

| 2 | Flavone | Chrysoeriol | C16H12O6 | 300.2629 | ||||||||

| 3 | Flavone | Diosmetin | C16H12O6 | 300.2629 | ||||||||

| 4 | Flavone | Myricetin | C15H10O8 | 318.2351 | ||||||||

| 5 | Flavone | Ampelopsin | C15H12O8 | 320.251 | ||||||||

| 6 | Flavone | 5,6-Dihydroxy-7,8,3’,4’tetramethoxyflavone | C19H18O8 | 374.3414 | ||||||||

| 7 | Flavone | Dihydroxy tetramethoxyflavanone | C19H20O8 | 376.3573 | ||||||||

| 8 | Flavone | Diosmin | C28H32O15 | 608.5447 | ||||||||

| 9 | Flavonol | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 286.2363 | ||||||||

| 10 | Flavonol | Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 302.2357 | ||||||||

| 11 | Flavonol | Herbacetin | C15H10O7 | 302.2357 | ||||||||

| 12 | Flavonol | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 316.2623 | ||||||||

| 13 | Flavonol | Quercetin 3-O- glucoside | C21H20O12 | 464.3763 | ||||||||

| 14 | Flavonol | Myricetin-3-O-galactoside | C21H20O13 | 480.3757 | ||||||||

| 15 | Flavonol | Kaempferol diacetyl hexoside | C25H24O13 | 532.4503 | ||||||||

| 16 | Flavonol | Quercetin glucuronide sulfate | C21H18O16S | 558.4230 | ||||||||

| 17 | Flavonol | Quercetin malonyl dihexoside | C30H32O20 | 712.5631 | ||||||||

| 18 | Flavan-3-ol | Catechin | C15H14O6 | 290.2681 | ||||||||

| 19 | Flavan-3-ol | Epicatechin | C15H14O6 | 290.2681 | ||||||||

| 20 | Flavan-3-ol | Gallocatechin | C15H14O7 | 306.2675 | ||||||||

| 21 | Flavanone | Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 272.5228 | ||||||||

| 22 | Flavanone | Eriodictyol-7-O-glucoside | C21H22O11 | 450.3928 | ||||||||

| 23 | Oligomeric proanthocyanidin | Epiafzelechin | C15H14O5 | 274.2687 | ||||||||

| 24 | Oligomeric proanthocyanidin | Epiafzelechin-epiafzelechin | C30H24O10 | 544.5056 | ||||||||

| 25 | Hydroxybenzoic acid | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | 138.1207 | ||||||||

| 26 | Hydroxycinammic acid | p-Coumaric acid | C9H8O3 | 164.16 | ||||||||

| 27 | Trans-cinnamic acid | Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 194.184 | ||||||||

| 28 | Benzoic acid | 3,4-Diacetoxybenzoic acid | C10H11O6 | 238.1935 | ||||||||

| 29 | Hydroxybenzoic acid (Phenolic acid) | Salvianolic acid G | C18H12O7 | 340.2837 | ||||||||

| 30 | Hydroxycinnamic acid | Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | 354.3087 | ||||||||

| 31 | Anthocyanin | Petunidin | C16H13O7+ | 317.2702 | ||||||||

| 32 | Hydroxycoumarin | Fraxidin | C11H10O5 | 222.1941 | ||||||||

| 33 | Dihydrochalcone | Phlorizin | C21H24O10 | 436.4093 | ||||||||

| Others | ||||||||||||

| 34 | L-alpha amino acid | L-Pyroglutamic acid | C5H7NO3 | 129.1140 | ||||||||

| 35 | Amino acid | Leucine | C6H13NO2 | 131.1729 | ||||||||

| 36 | Amino acid | L-Glutamate | C5H7NO4 | 145.1134 | ||||||||

| 37 | Amino acid | L-Lysine | C6H14N2O2 | 146.1876 | ||||||||

| 38 | Amino acid | Phenylalanine [L-Phenylalanine] | C9H11NO2 | 165.1891 | ||||||||

| 39 | Amino acid | Nordenine | C10H15NO | 165.2322 | ||||||||

| 40 | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | Schikimic acid | C7H10O5 | 174.1513 | ||||||||

| 41 | Monobasic carboxylic acid | Hydroxyphenyllactic acid | C9H10O4 | 182.1733 | ||||||||

| 42 | Polyhydroxycarboxylic acid | Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 192.1666 | ||||||||

| 43 | Tricarboxylic acid | Citric acid | C6H8O7 | 192.1235 | ||||||||

| 44 | Essential amino acid | L-Tryptophan | C11H12N2O2 | 204.2252 | ||||||||

| 45 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Dodecatetraenedioic acid | C12H14O4 | 222.2372 | ||||||||

| 46 | Carboxylic acid | Myristoleic acid | C14H26O2 | 226.3550 | ||||||||

| 47 | Phenolic amine | N-Caffeoylputrescine | C13H18N2O3 | 250.2936 | ||||||||

| 48 | Phenolic amine | N-feruloylputrescine | C14H20N2O3 | 264.3202 | ||||||||

| 49 | Omega-3 fatty acid | Stearidonic acid | C18H28O2 | 276.4137 | ||||||||

| 50 | Phenylpropanoid | Triandrin | C15H20O7 | 312.3151 | ||||||||

| 51 | Unsaturated fatty acid | Octadecanedioic acid | C18H34O4 | 314.4602 | ||||||||

| 52 | Unsaturated essential fatty acid | Oxo-eicosatetraenoic acid | C20H30O3 | 318.4504 | ||||||||

| 53 | Fructose-phenylalanine | C15H21NO7 | 327.3297 | |||||||||

| 54 | Higher-molecular-weight carboxylic acid | 9,10-Dihydroxy-8-oxooctadec-12-enoic acid | C18H32O5 | 328.4437 | ||||||||

| 55 | Oxylipin | Epoxyoctadecane-dioic acid | C18H32O5 | 328.4437 | ||||||||

| 56 | Phenolic amine | N-feruloyloctopamine | C18H19NO5 | 329.3472 | ||||||||

| 57 | Oxylipin | 13- Trihydroxy-Octadecenoic acid | C18H34O5 | 330.4596 | ||||||||

| 58 | Oxylipin | 9,12,13- Trihydroxy-trans-10-octadecenoic acid | C18H34O5 | 330.4596 | ||||||||

| 59 | Cyclohexenecarboxylic acid | 3-O-caffeoylshikimic acid [3-Csa] | C16H16O8 | 336.2934 | ||||||||

| 60 | Pentacyclic diterpenoid | Gibberellic acid | C19H22O6 | 346.3744 | ||||||||

| 61 | Higher-molecular-weight carboxylic acid | Pentacosenoic acid | C25H48O2 | 380.6474 | ||||||||

| 62 | Steroidal alkaloid | Solanidine | C27H43NO | 397.6364 | ||||||||

| 63 | Sterol | Stigmasterol | C29H48O | 412.6908 | ||||||||

| 64 | Steroidal alkaloid | Tomatidinol | C27H43NO2 | 413.6358 | ||||||||

| 65 | Anabolic steroid | Vebonol | C30H44O3 | 452.6686 | ||||||||

| 66 | Phenolic amine | N1,N8-bis(dihydrocaffeoyl) spermidine | C25H35N3O6 | 473.5619 | ||||||||

| 67 | Polyhydroxycarboxylic acid | 1-O-caffeoyl-5-O-feruloylquinic acid | C26H26O12 | 530.4774 | ||||||||

| 68 | Steroidal alkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C32H33NO8 | 559.6063 | ||||||||

| 69 | Glycoalkaloid | Beta-chaconine | C39H63NO10 | 705.9182 | ||||||||

| 70 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C39H63NO11 | 721.9176 | ||||||||

| 71 | Glycoalkaloid | Dehydrochaconine | C45H71NO14 | 850.0435 | ||||||||

| 72 | Glycoalkaloid | Alpha-chaconine | C45H73NO14 | 852.0594 | ||||||||

| 73 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadienol chacotriose | C45H71NO15 | 866.0429 | ||||||||

| 74 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadiene solatriose | C45H71NO15 | 866.0429 | ||||||||

| 75 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidenone chacotriose | C45H71NO15 | 866.0429 | ||||||||

| 76 | Glycoalkaloid | Alpha-solanine | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | ||||||||

| 77 | Glycoalkaloid | Leptinine I | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | ||||||||

| 78 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidenol chacotriose | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | ||||||||

| 79 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadiene solatriose | C45H73NO15 | 868.9588 | ||||||||

| 80 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidadienol solatriose | C45H71NO16 | 882.0423 | ||||||||

| 81 | Glycoalkaloid | Leptinine II | C45H73NO16 | 884.0582 | ||||||||

| 82 | Glycoalkaloid | Solanidenol solatriose | C45H73NO16 | 884.0582 | ||||||||

| 83 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C45H75NO16 | 886.0741 | ||||||||

| 84 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C45H77NO16 | 888.0900 | ||||||||

| 85 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C46H75NO16 | 898.0848 | ||||||||

| 86 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C45H76NO17 | 903.0814 | ||||||||

| 87 | Glycoalkaloid | Unknown glycoalkaloid | C49H79NO18 | 970.1475 |

References

- Spooner, D.M.; Hijmans, R.J. Potato systematics and germplasm collecting, 1989–2000. Am. J. Potato Res. 2001, 78, 237–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessner, U.; Willmitzer, L.; Fernie, A.R. High-resolution metabolic phenotyping of genetically and environmentally diverse potato tuber systems. Identification of phenocopies. Plant Physiol. 2001, 127, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stobiecki, M.; Matysiak-Kata, I.; Franski, R.; Skala, J.; Szopa, J. Monitoring changes in anthocyanin and steroid alkaloid glycoside content in lines of transgenic potato plants using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Perez, C.; Gomez-Caravaca, A.M.; Guerra-Hernandez, E.; Cerretani, L.; Garcia-Villanova, B.; Verardo, V. Comprehensive metabolite profiling of Solanum tuberosum L. (potato) leaves T by HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. Molecules 2018, 112, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oertel, A.; Matros, A.; Hartmann, A.; Arapitsas, P.; Dehmer, K.J.; Martens, S.; Mock, H.P. Metabolite profiling of red and blue potatoes revealed cultivar and tissue specific patterns for anthocyanins and other polyphenols. Planta 2017, 246, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.W.; Bain, H.; Dale, M.F.B. The effect of low-temperature storage on the glycoalkaloid content of potato (Solanum tuberosum) tubers. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1997, 74, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krits, P.; Fogelman, E.; Ginzberg, I. Potato steroidal glycoalkaloid levels and the expression of key isoprenoid metabolic genes. Planta 2007, 227, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, R.; Navarre, D.A. LC-MS Analysis of Solanidane Glycoalkaloid Diversity among Tubers of Four Wild Potato Species and Three Cultivars (Solanum tuberosum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 6949–6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnqvist, L.; Dutta, P.C.; Jonsson, L.; Sitbon, F. Reduction of cholesterol and glycoalkaloid levels in transgenic potato plants by overexpression of a type 1 sterol methyltransferase cDNA. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 1792–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; McDonald, G.M. Potato glycoalkaloids: Chemistry, analysis, safety, and plant physiology. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1997, 16, 55–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmacopoeia of the Eurasian Economic Union. Approved by Decision of the Board of Eurasian Economic Commission No. 100. 2020. Available online: http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/texnreg/deptexreg/LSMI/Documents/Фармакoпея%20Сoюза%2011%2008.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sharif, K.; Mohamed, A.; Sahena, F.; Jahurul, M.; Ghafoor, K.; Norulaini, N.; Omar, A. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuber, H.; Guignard, C.; Hoffmann, L.; Evers, D. Polyphenol and glycoalkaloid contents in potato cultivars grown in Luxembourg. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 2814–2824. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Serra, O.; Dastmalchi, K.; Jin, L.; Yang, L.; Stark, R.E. Comprehensive MS and Solid-state NMR Metabolomic Profiling Reveals Molecular Variations in Native Periderms from Four Solanum tuberosum Potato Cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 2258–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Brunton, N.P.; Rai, D.K. Effect of Drying Methods on the Steroidal Alkaloid Content of Potato Peels, Shoots and Berries. Molecules 2016, 21, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, P.; Liu, B.; Ge, D.; Wei, L.; Xu, Y. Simultaneous determination of fourteen compounds of Hedyotis diffusa Willd extract in rats by UHPLC–MS/MS method: Application to pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution study. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 159, 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Jia, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Shi, H.; Zhang, L. LC-MS/MS determination and pharmacokinetic study of seven flavonoids in rat plasma after oral administration of Cirsium japonicum DC. extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 158, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojakowska, A.; Perkowski, J.; Goral, T.; Stobiecki, M. Structural characterization of flavonoid glycosides from leaves of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using LC/MS/MS profiling of the target compounds. J. Mass. Spectrom. 2013, 48, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gong, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Yu, S.; Xiong, L.; Luo, J. A Novel Integrated Method for Large-Scale Detection, Identification, and Quantification of Widely Targeted Metabolites: Application in the Study of Rice Metabolomics. Mol. Plant. 2013, 6, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.L.; Xu, J.J.; Zhong, K.R.; Shang, Z.P.; Wang, F.; Wang, R.F.; Liu, B. Analysis of non-volatile chemical constituents of Menthae haplocalycis herba by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography–high resolution mass spectrometry. Molecules 2017, 22, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goufo, P.; Singh, R.K.; Cortez, I. Phytochemical A Reference List of Phenolic Compounds (Including Stilbenes) in Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Roots, Woods, Canes, Stems, and Leaves. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafsanjany, N.; Senker, J.; Brandt, S.; Dobrindt, U.; Hensel, A. In Vivo Consumption of Cranberry Exerts ex Vivo Antiadhesive Activity against FimH-Dominated Uropathogenic Escherichia coli: A Combined in Vivo, ex Vivo, and in Vitro Study of an Extract from Vaccinium macrocarpon. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 8804–8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamed, A.R.; El-Hawary, S.S.; Ibrahim, R.M.; Abdelmohsen, U.R.; El-Halawany, A.M. Identification of Chemopreventive Components from Halophytes Belonging to Aizoaceae and Cactaceae Through LC/MS–Bioassay Guided Approach. J. Chrom. Sci. 2021, 59, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, M.N.; Winterhalter, P.; Jerz, G. Flavonoids from the flowers of Impatients glandulifera Royle isolated by high performance countercurrent chromatography. Phytochem. Anal. 2016, 27, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Jamous, R.M.; Arraes-Roman, D.; Segura-Carretero, A. HPLC–DAD–ESI-MS/MS screening of bioactive components from Rhus coriaria L. (Sumac) fruits. Food Chem. 2015, 166, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Kumar, B. HPLC–QTOF–MS/MS-based rapid screening of phenolics and triterpenic acids in leaf extracts of Ocimum species and their interspecies variation. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2016, 39, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.O.; Vilela, C.; Freire, C.S.R.; Neto, C.P.; Silvestre, A.J.D. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry applied to the identification of valuable phenolic compounds from Eucalyptus wood. J. Chromatogr. B 2013, 938, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, M.; Sandhir, R.; Singh, A.; Kumar, P.; Mishra, A.; Jachak, S.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, J.; Roy, J. Comparison analysis of phenolic compound characterization and their biosynthesis genes between two diverse bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) varieties differing for chapatti (unleavened flat bread) quality. Front. Plant. Sci. 2016, 7, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallverdu-Queralt, A.; Jauregui, O.; Medina-Remon, A.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Evaluation of a Method to Characterize the Phenolic Profile of Organic and Conventional Tomatoes. Agricult. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 3373–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeywickrama, G.; Debnath, S.C.; Ambigaipalan, P.; Shahidi, F. Phenolics of selected cranberry genotypes (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) and their antioxidant efficacy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 9342–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsalo, A.; Jalonen, J.; Tolonen, A. Identification of flavonoids of Rhodiola rosea by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr. A. 2006, 1112, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Wang, C.; Zou, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Tan, M.; Mei, Y.; Wei, L. Comparison of Multiple Bioactive Constituents in the Flower and the Caulis of Lonicera japonica Based on UFLC-QTRAP-MS/MS Combined with Multivariate Statistical Analysis. Molecules 2019, 24, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasir, M.; Sultana, B.; Anwar, F. LC–ESI–MS/MS based characterization of phenolic components in fruits of two species of Solanaceae. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2370–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paudel, L.; Wyzgovski, F.J.; Scheerens, J.C.; Chanon, A.M.; Reese, R.N.; Smiljanic, D.; Wesdemiotis, C.; Blakeslee, J.J.; Riedl, K.M.; Rinaldi, P.L. Nonanthocyanin Secondary Metabolites of Black Raspberry (Rubus occidentalis L.) Fruits: Identification by HPLC-DAD, NMR, HPLC-ESI-MS, and ESI-MS/MS Analyses. J. Agricult. Food. Chem. 2013, 61, 12032–12043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perchuk, I.; Shelenga, T.; Gurkina, M.; Miroshnichenko, E.; Burlyaeva, M. Composition of Primary and Secondary Metabolite Compounds in Seeds and Pods of Asparagus Bean (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) from China. Molecules 2020, 25, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Masi, L.; Bontempo, P.; Rigano, D.; Stiuso, P.; Carafa, V.; Nebbioso, A.; Piacente, S.; Montoro, P.; Aversano, R.; D’Amelia, V.; et al. Comparative Phytochemical Characterization, Genetic Profile, and Antiproliferative Activity of Polyphenol-Rich Extracts from Pigmented Tubers of Different Solanum tuberosum Varieties. Molecules 2020, 25, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirlini, M.; Mena, P.; Tassotti, M.; Herrlinger, K.A.; Nieman, K.M.; Dall’Asta, C.; Del Rio, D. Phenolic and volatile composition of a dry spearmint (Mentha spicata L.). Molecules 2016, 21, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, T.; Fukui, M.; Nakazawa, T.; Hoshikawa, A.; Ohsawa, K. Metabolic Fate of Fraxin Administrated Orally to Rats. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 755–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozarowski, M.; Piasecka, A.; Paszel-Jaworska, A.; de Chaves, D.S.A.; Romaniuk, A.; Rybczynska, M.; Gryszczynska, A.; Sawikowska, A.; Kachlicki, P.; Mikolajczak, P.L.; et al. Comparison of bioactive compounds content in leaf extracts of Passiflora incarnata, P. caerulea and P. alata and in vitro cytotoxic potential on leukemia cell lines. Braz. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 28, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova-Petropulos, V.; Naceva, Z.; Sandor, V.; Makszin, L.; Deutsch-Nagy, L.; Berkics, B.; Stafilov, T.; Kilar, F. Fast determination of lactic, succinic, malic, tartaric, shikimic, and citric acids in red Vranec wines by CZE-ESI-QTOF-MS. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, T.; Slovin, J.; Chen, P. Profiling polyphenols of two diploid strawberry (Fragaria vesca) inbred lines using UHPLC-HRMSn. Food Chem. 2014, 146, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallmann, J.; Schweiger, R.; Pons, C.A.A.; Muller, C. Wheat growth, applied water use efficiency and flag leaf metabolome under continuous and pulsed deficit irrigation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.T.; Wu, X.; Rui, W.; Guo, J.; Feng, Y.F. UPLC/Q-TOF-MS analysis for identification of hydrophilic phenolics and lipophilic diterpenoids from Radix Salviae miltiorrhizae. Acta Chromatogr. 2015, 27, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorent-Martinez, E.J.; Spinola, V.; Gouveia, S.; Castilho, P.C. HPLC-ESI-MSn characterization of phenolic compounds, terpenoid saponins, and other minor compounds in Bituminaria bituminosa. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 69, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Ha, J.S.; Kim, J.M.; Kang, J.Y.; Lee, D.S.; Guo, T.J.; Lee, U.; Kim, D.-O.; Heo, H.J. Antiamnesic Effect of Broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) Leaves on Amyloid Beta (Aβ)1-42-Induced Learning and Memory Impairment. J. Agricult. Food. Chem. 2016, 64, 3353–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hoyweghen, L.; De Bosscher, K.; Haegeman, G.; Deforce, D.; Heyerick, A. In Vitro Inhibition of the Transcription Factor NF-kB and Cyclooxygenase by Bamboo Extracts. Phytother. Res. 2013, 28, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yao, P.; Leung, K.W.; Wang, H.; Kong, X.P.; Wang, L.; Dong, T.T.X.; Chen, Y.; Tsim, K.W.K. The Yin-Yang Property of Chinese Medicinal Herbs Relates to Chemical Composition but Not Anti-Oxidative Activity: An Illustration Using Spleen-Meridian Herbs. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M.P.; Tekutyeva, L.A.; Podvolotskaya, A.B.; Stepochkina, V.D.; Zakharenko, A.M.; Golokhvast, K. Zostera marina L. Supercritical CO2-Extraction and Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Chemical Constituents Recovered from Seagrass. Separations 2022, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Zhu, J.; Ding, M.; Lv, G. Simultaneous determination of gibberellic acid, indole-3-acetic acid and abscisic acid in wheat extracts by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 2008, 76, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, G.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; De Benedetto, G.; Kettrup, A.; Cataldi, T.R.I. Determination of glycoalkaloids and relative aglycones by nonaqueous capillary electrophoresis coupled with electrospray ionization-ion trap mass spectrometry. Electrophoresis 2002, 23, 2904–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, D.; Akdeniz, M.; Ertas, A.; Yilmaz, M.A.; Yener, I.; Firat, M.; Kolak, U. A GC–MS method validation for quantitative investigation of some chemical markers in Salvia hypargeia Fisch. & C.A. Mey. of Turkey: Enzyme inhibitory potential of ferruginol. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarz, H.; Roloff, N.; Niehaus, K. Mass Spectrometry Imaging of the Spatial and Temporal Localization of Alkaloids in Nightshades. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13470–13477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spinola, V.; Pinto, J.; Castilho, P.C. Identification and quantification of phenolic compounds of selected fruits from Madeira Island by HPLC-DAD-ESI-MSn and screening for their antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraone, I.; Rai, D.K.; Chiummiento, L.; Fernandez, E.; Choudhary, A.; Prinzo, F.; Milella, L. Antioxidant Activity and Phytochemical Characterization of Senecio clivicolus Wedd. Crit. Mol. 2018, 23, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).