Abstract

This article attempts to shed light on the challenges confronting relevant actors (state and non-state) in countering the threat of terrorism recruitment by focusing on the Boko Haram terrorist organization, whose presence and activities threaten the security of the Lake Chad region. The article uses a qualitative research technique combining key informant interviews with stakeholders familiar with the conflict, academic and non-academic documents, reports, and policy briefs. The findings of the article suggest that despite the various initiatives by stakeholders aimed at containing the strategies of recruitment, the group continues to expand its base by launching coordinated attacks that further destabilize the region. These challenges stem from a lack of a clear-cut counterterrorism strategy, a dearth in technological and mutual trust between actors and locals in the management and utilization of intelligence, and the inability of state institutions to ‘coerce and convince’ citizens in terms of its capacity to counter the danger of terrorism recruitment and expansion. The article, amongst other things, recommends a community policing model similar to the ‘Nyumba-Kumi security initiative’ adopted by most countries in East Africa for the effective assessment and detection of threat forces; the state and its agencies should show the capacity to coerce and convince in dealing with the (ideological, religious, social, and economic) conditions, drivers, and factors promoting the spread of terrorism as well as other forms of violent extremism in the society; furthermore, there is a need for stakeholders to adopt a comprehensive and holistic counterterrorism/violent extremism strategy to reflect present-day security challenges as well as to guarantee sustainable peace.

1. Introduction

Countering the recruitment, expansion, and activities of terrorist organizations is one of the major challenges confronting actors in combating terrorism (Weeraratne 2017). This is because terrorism remains a major threat to the stability of the international system, given that its impacts whenever such attacks take place leave a long-lasting emotional, physical, and psychological trauma on the targets and victims (Bergesen and Lizardo 2004; Ranstorp 2006; Cannon and Iyekekpolo 2018). This assertion also relates to the Boko Haram1 terrorist group operating in the northeastern2 part of Nigeria and the Lake Chad Region in West Africa.3 Several studies have suggested that after the death of its founding leader, Mohammed Yusuf, in 20094, the organization regrouped and resurfaced in 2010 and began carrying out a series of coordinated attacks on civilians, places of religious worship, as well as private, public, and state institutions (Maiangwa et al. 2012; Onuoha 2012; Oyewole 2015; Umukoro 2016; Tukur 2017; Felter 2018). These attacks ranged from suicide raids, kidnapping, to the use and deployment of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The impact of these attacks led to over 100,000 documented deaths, the destruction of properties amounting to over nine billion US dollars, and the displacement of over 2,400,000 persons across the Lake Chad Basin. This has led to the group being regarded as one of the most dangerous terrorist organizations around the world (China Global Television Network 2017; Matfess 2017; Premium Times 2017a, 2017b; Institute for Economics and Peace 2015, 2017, 2018).

It should be noted that for terrorist organizations to stay relevant and operate effectively, the need for regular recruitment of members is an existential reality to ensure their survival (Ranstorp 2006). Campbell (2013), Zenn (2013a, 2013b), Voll (2015), and the UNODC (2017), highlighted four fundamental conditions most terrorist organizations employ to recruit members. These reasons include Financial Incentives to lure individuals affected by negative structural conditions such as poverty, unemployment, and poor welfare services as easy targets for terrorist organizations. The societal influence of Kinship, where individuals who are biologically and socially related with persons affiliated to terrorist organizations are conscripted by these groups. The long history of inter-religious and politically motivated violence influenced by the elites has not only divided most societies along religious lines, but has also created a level of mutual suspicion across the various religious divides, as witnessed in Nigeria, which makes it easy for groups such as Boko Haram to recruit members. The negative use of religion as a tool for radicalization and preaching of violent and extreme views by rogue clerics to indoctrinate individuals into these terrorist organizations. These reasons serve as the optics and framework most studies coalesce around when looking at the strategies used by violent extremist groups to recruit members (Combs 2017; Iyekekpolo 2018).

Although several studies have focused on terrorism and Boko Haram, the understanding of strategies used by terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram to recruit members remains largely under-researched. It is in this context that this article seeks to examine the strategies used by this group to recruit members and also the challenges confronting stakeholders in combating them. It adopts a qualitative research technique through the use of academic, non-academic documents, reports, and personal interviews in the form of key informant interviews (KIIs), with community and religious leaders, academic and policy experts, and individuals affected by the activities of Boko Haram. The article seeks to contribute to the growing literature on terrorist recruitment strategy, the role of actors and other relevant stakeholders5 in combating these strategies and the challenges confronting stakeholders in countering them. In this context, the article asks the following research questions: What are the various Boko Haram recruitment strategies? What are the measures taken by stakeholders to combat Boko Haram’s recruitment strategy? What are the challenges confronting stakeholders in confronting them?

The article is structured and organized under the following sub-headings. Following the introduction, the second part of the article clearly outlines the methodology as well as the questions required by the key informants as it pertains Boko Haram recruitment strategies, the contributions by relevant actors in countering these strategies and also the challenges in combating Boko Haram recruitment strategies across Lake Chad. The third section, clarifies and theorizes the concept of terrorist recruitment, reviews the various studies on terrorist recruitment, the methods and strategies used by Boko Haram to recruit members. Measures taken by relevant stakeholders at the national, sub-regional, and regional levels to confront the recruitment and expansion of this terrorist organization forms the fourth part of the study. The fifth part of the article focuses on the challenges confronting actors in combating Boko Haram’s recruitment. The sixth part concludes the findings, recommendations, and avenues for further research.

2. Methodology

As stated in the introduction, this article, adopts the qualitative research approach through the use of academic, non-academic documents, reports, and personal interviews in the form of key informant interviews, with community and religious leaders, academic and policy experts, and individuals affected by the activities of Boko Haram. These key informants represent individuals from academia, members of the security sector, civil societies, faith-based organizations, community and opinion leaders, and also some residents of the affected areas by the activities of Boko Haram (Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states).

The selection of this group of informants was informed by their expertise and contribution to the subject. They represent targeted groups with primary or first-hand experience on the Boko Haram challenge and its implication on peace, security, stability, and development of the northeast and the Lake Chad region. In specific terms, these informants were asked questions related to the various Boko Haram recruitment strategies (BHRS), the measures taken by relevant stakeholders (national governments, sub-regional, and regional actors like the Economic Community of West African States, the Lake Chad Basin Commission, and the contribution of civil society groups and faith-based institutions) in addressing these BHRS, and the challenges confronting these actors in combating BHRS across Lake Chad. The interviews and research process were conducted from the period starting 1 June, 2018 to December, 2019. While the study respects and maintains the anonymity of these key informants (respondents), their areas of expertise, affiliations, and initials were used sparingly for better clarity.

3. Terrorism Recruitment (TR) and Boko Haram’s Recruitment Strategy: What Does the Literature Say?

3.1. Terrorist Recruitment: Conceptual Clarification and Theoretical Discussions

As suggested by Forest (2006), there is no universally accepted definition for the concept of terrorism recruitment (TR). However, most studies on terrorism are of the opinion that terrorism recruitment refers to the various sociological, political, economic, ideological, religious, and psychological strategies and tactics used by terrorist organizations to enlist members (Faria and Arce M. 2005; Neumann 2012; Özeren et al. 2014; Klein 2016; Bloom 2017). These strategies could be violent or non-violent as well as the integration of the various socio-cultural, economic, ideological, psychological, and political conditions that motivate individuals into joining terror groups (Post et al. 2002; Forest 2006; Knapton 2014; Jones 2017).

Most theoretical discussions on terrorist recruitment situate their narratives on the basis of the Social Movement Approach (Gentry 2004). This is because the theory places emphasis on the narrative that most terrorist organizations started as informal and semi-structured groups focusing on certain societal issues and challenges affecting societies (Beck 2008). These challenges enabled them to create the false perception among individuals and targeted groups leading them to believe that they can provide a better alternative. These movements are predominantly anti-establishment, anti-status quo, and anti-elitist, seeing them as the reasons for creating the conditions for the social problems affecting societies (Shannon 2011; Prud’homme 2019). These movements create the opportunity and space for terrorist organizations to mobilize and recruit members given that their messages resonate some level of social consciousness that appeals to individuals and groups with grievances against the establishment (Kruglanski and Fishman 2009; Newton 2011; Ortbals and Poloni-Staudinger 2014; Özeren et al. 2014; Del Vecchio 2016; Klein 2016). Consequently, these terror groups continue to use the platform they have under the pretext of social movements as a strategy for not only recruitment; these recruits are continuously engaged by these violent extremist groups to ensure the sustainability and survival of such movements (Pieri and Zenn 2018). The emphasis on ensuring the group’s survival is an important component through which relevant stakeholders involved in countering the threat posed by terror groups and their expansionist agenda should explore and address. This is because any process of disengagement and counter-terrorist recruitment requires a high level of effort by these actors to limit the influence of some of these negative social movements (ibid).

It is important to note that despite the advantage of social movements as instruments of social change in societies, where they serve as a vehicle for easy mobilization (Hairgrove and Mcleod 2008), they also offer some level of legitimacy for individuals and groups aggrieved by certain societal dysfunctions to express their resentments against the current social order by effecting positive change (Joosse et al. 2015). With the ability to mobilize and a wider reach to a targeted population to disseminate their messages, terrorist groups easily exploit these avenues and opportunities provided by these movements to recruit individuals and groups who share similar radical religious and ideological beliefs (Sarjoon et al. 2016; Smith et al. 2018; Madonia and Planet Contreras 2019).

As put forward by Loimeier (2012), Adegbulu (2013), and Murtada (2013), Boko Haram emerged from the various social movements that existed in the northern part of Nigeria, including Mohammed Marwa’s Maitatsine6 movement of the 1980s to the Sahaba Muslim Youth Organization, Abubakah Lawan’s Ahlulsunnawal Jama’ah, and the Yobe Taliban, which existed from the 1990s to the early 2000s (Aghedo 2014; Olojo 2015; Azumah 2015; Chiluwa 2015; Gray and Adeakin 2015; Voll 2015; Iyekekpolo 2016; Pieri and Zenn 2016; Amaechi 2017; Magrin and De Montclos 2018; Rasak 2018). These organizations later evolved to what is today known as Boko Haram. These movements not only have a massive following in northern Nigeria, but their extreme views against secularism, and the modern state system have endeared them to many who believe they serve as an instrument for social change in Nigeria.7

Besides the social movement theoretical stance that explains the various strategies used by terror groups and other violent extremist groups, to recruit fighters, another theory that seeks to explain the paradigm of terrorist recruitment is the anthropological emphasis on culture as an avenue these terror groups used to attract and enlist recruits into their folds (Pieri and Zenn 2018). This theory extends the narrative by studies that situate their focus and emphasis on the daily ideological and operational drivers used by these groups to recruit fighters. This approach focused on the level of social engagements, inter-group relations, solidarity, and bonds created by this jihadi culture (Pieri and Zenn 2018). To sum up, this approach explains this paradox of terrorist recruitment as a lifestyle through which people learn over time (Pieri 2019).

Relating this to the Boko Haram recruitment strategy, studies revealed that beyond the public propaganda and instrumentalization of violence by this terror group, Boko Haram has interacted and built inter-group relations, strong communal bonds, loyalty, and solidarity (MacEachern 2018; Agbiboa 2019; Pieri 2019). This form of loyalty, social cohesion, and culture enabled the group to not only attract naïve individuals into joining them (Boko Haram), but also making it possible for the group to ensure that these recruits see the “jihadist culture” as nothing but a way of life (Pieri and Zenn 2018). It reflects this pattern of lifestyle in its members engaging in the popular motor-cycle transportation business popularly called ‘achaba’ in communities they control (Agbiboa 2019). Members of the group are also said to regularly interface and interact with the locals in communities they control. They also engage in preaching their jihadist messages, expressing themselves in comedy, music, drama, dance, and other forms of entertainment in the Arabic, Kanuri, and Hausa8 languages (Pieri and Zenn 2018). Therefore, it is said that the group adopts this tactic as a strategy to attract individuals into joining them. This is because these locals see them as ordinary people, interacting with ordinary locals regardless of the popular narrative that the group (Boko Haram) uses violence to propagate its messages to the public.

Studies by other scholars (Adegbulu 2013; Hill 2013; Zenn et al. 2013; Aghedo 2014; Olojo 2015; Chiluwa 2015; Gray and Adeakin 2015; Pham 2016; Pieri and Zenn 2016), focused on the negative misrepresentation of ideology and the weaponization of religion by terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram to recruit members. This could be seen through the negative teachings given by Mohammed Yusuf to his followers that Islam abhors ‘Western civilization’ and all its imprints (see Umar 2012, p. 144). Such messages increasingly created the false perception that Western civilization is anti-Islamic and most of the problems affecting the society are linked with the saturation of Western values in Nigerian society (Hansen 2017; Zenn 2018). These negative misrepresentations and the instrumentalization of religion encouraged individuals to join Boko Haram. Olojo (2017), Magrin and De Montclos (2018), were of the view that despite the negative use of religion as a tool for terrorist recruitment, it also plays a vital role in deradicalization and also dissuading individuals from becoming members of terrorist organizations. According to their analysis, religious leaders and clerics have a role in changing the narrative and negative representation of religion used by terror groups to recruit members.

Further studies (Ayegba 2015; Eke 2015; Dowd and Drury 2017; Oriola 2017; Rufai 2017; Ajala 2018; Babatunde 2018; Hentz 2018) focused on the multidimensional challenges confronting Nigeria, which enabled Boko Haram to exploit and lure individuals into joining their crusade. These challenges ranged from the long history of conflict in the country, the inability of the government to address the problems of bad governance, corruption, poverty, unemployment, provision of social services to citizens, marginalization, and inequality, which paved the way for alienation and a lack of trust between citizens and their leaders. These conditions of social exclusion and disillusionment, especially in the northern part of Nigeria, created an avenue for radical groups to conscript individuals to their groups, like in the case of Boko Haram.

3.2. Boko Haram’s Recruitment Strategy

Before delving into the various strategies used by Boko Haram to recruit members, it is important to note that as an organization with over 6000 active fighters and transnational reach, Boko Haram has recruited individuals from Cameroun, Chad, Niger, Mali, and Libya (The Guardian News 2015; Walker 2016; Sampson 2016; Adelani et al. 2017; Mentan 2017; Rufai 2017). A discussion with an informant agreed with the position put forward by (David et al. 2015), that revealed three factors which contributed to the transnational reach of the organization to recruit foreign fighters. First, the poor state of Nigeria’s border enabled people to illegally migrate into the country with no form of border checks by immigration officers. Second, the abuse of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) policy on the free movement of persons across the sub-region created the avenue for criminals and mercenaries to easily move around. Third, the societal, cultural, and religious ties of Nigerians in the northeast with citizens of countries in the Lake Chad and the Sahel regions, especially Chadians, Nigeriens, and Malians, allowed people to easily integrate with little difficulty. These three factors have made Boko Haram more ambitious in increasing its membership and attracting fighters from these countries.9 Therefore, the international composition of Boko Haram has downplayed the stereotype and negative perception that members of this organization are Nigerians, illiterates, and poor.10 This is because various studies have revealed that Boko Haram attracts and recruits individuals from diverse socio-economic, educational, cultural, religious, and ideological backgrounds (Umar 2013; Mercy Corps 2016). Because of this, it would be wrong to claim that recruitment into Boko Haram is restricted to a certain group of people in society.

Terrorist organizations rely on people and manpower to carry out their activities (Asal et al. 2012; Clauset and Gleditsch 2012). Boko Haram, like most terrorist organizations, deploys several strategies for recruiting individuals. These strategies involve techniques such as coercion, consent, hypnosis, and the promise of financial incentives (see Campbell 2013; Torbjornsson and Michael 2017).

The alleged false promise of better welfare and improved economic conditions is identified as a strategy used by Boko Haram to recruit their members. Studies have shown that most individuals cite the lack of economic opportunities, poverty, unemployment, and access to better welfare as reasons for joining Boko Haram (Onapajo and Uzodike 2012; Zenn 2013b; Umar 2013; Fessy 2016; Mercy Corps 2016). Terrorist groups like Boko Haram capitalized on the inability of the Nigerian government to provide these services and opportunities to its people by promising them these financial incentives if they are recruited (Fessy 2016). The narrative that Boko Haram pay as much as $3000 daily to its fighters has further attracted and motivated individuals to join this organization, driven by the desire for better economic welfare (Nduka 2019).

Forceful conscription is another strategy used by Boko Haram to recruit members into the organization (Ajayi 2014; Walker 2016; Oriola 2017; Markovic 2019). Increasingly, research and reports have shown that since the activities of this terrorist group became manifest in 2009, the organization has enlisted over 8000 children who perform combat and non-combatant activities for the terrorist group (See Adnan 2019; BBC News 2019; Human Rights Watch 2019). It has kidnapped girls and women who have been forced into carrying out suicide attacks, while others serve as cooks and wives for members of the terrorist group (Brock 2013; Ameh 2014; Dixon 2014; Swails and David 2016; Nwaubani 2017, 2019). A report published by the Global Terrorism Database revealed that over 150 incidents of suicide attacks carried out by the group across Lake Chad were committed by children and women, making it the terrorist organization that recruits the highest proportion of women, as they constitute fifty percent (50%) of their suicide bombers (START 2018). In a conversation with one of the authors, an informant from Maiduguri further revealed that “it is no longer news that Boko Haram is forcing and using their women as suicide bombers; they constantly rape, and impregnate them, which they claim to be preparing the next generation of terrorists to continue their ideology”11 This strategy of forceful conscription adopted by Boko Haram for recruitment supports the narrative that it reduces the financial burden on the organization to spend resources on paying for fighters. It further helps in projecting their publicity and propaganda, and justifies the perception that children and women can easily infiltrate their targets with little suspicion (Galehan 2019).

Using cash loans traps is another method employed for recruitment by Boko Haram (Zenn 2013a; Abrak 2016; Guilberto 2016). Boko Haram uses this as a business model to assist the youths that are not employed and traders struggling to sustain their businesses to start new ventures and also to sustain their ailing businesses (Sigelmann 2019). Those unable to pay back the loans are coerced into joining the organization or volunteer by providing sensitive information on the movements and activities of the Multinational Joint Taskforce (MNJTF), who are responsible for combating the activities of the group in Lake Chad (Abrak 2016; Gaffey 2016; Magrin and De Montclos 2018). A transnational threats expert admitted when being interviewed that even though loan-traps is a strategy for recruitment by Boko Haram, the control of fishing activities in the Lake Chad area by the terrorist group allows them to recruit individuals who are unable to pay back their debts by employing them in this fish farms as a precondition for paying back their loans.12 That has not only increased the organization’s capacity to raise funds, but has also enabled it to increase its membership base.13

Recent studies on terrorist recruitment shows the transnational effect of advancements in information and technology, where the internet and its tools, especially social media, has become a recruitment hub for terrorist organizations to recruit fighters (Guadagno et al. 2010; Archetti 2013; Gates and Podder 2015; Weimann 2016; Ette and Joe 2018). This assertion has been supported by the statement credited to His Royal Highness Sanusi Lamido Sanusi the Emir of Kano, who said that the increasing exposure to and obsession with social media among youths and children, especially Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and WhatsApp, has had a negative impact on entrenching ethical values (Madugba 2015). This is because through personal networks and friendships developed in this virtual space, children are sometimes exposed to this negative indoctrination and manipulation of ideas by these extremist groups (Ibid). In a conversation with the author, a community leader in Angwan Rimi in Jos shared a sad experience that involved his niece who left home in November 2015 and travelled to Maiduguri (Borno State) to meet a Saurayi (Boyfriend) whom she supposedly met on Facebook. Unfortunately, this was the last time that she was seen as she disappeared and several searches produced no successful results. The last news the family received regarding her was that she had been married to a unit commander of Boko Haram. This story is one of many in which young people are deceived by strangers they meet online who have the ulterior motive of recruiting them into violent extremism. He concluded that it is the responsibility of parents to carefully monitor what children do with their phones.14 Therefore, it is important to note that terrorist groups such as Boko Haram increasingly use such platforms to share their videos, promote their ideology and propaganda, and transnationally appeal to individuals sympathetic to their cause to motivate them to join the group in their aim of eradicating the supposed moral decay in northern-Nigeria because of the influence of Western civilization (UNDP 2017; Ette and Joe 2018; Slutzker 2018).

Instrumentalizing Religion negatively is another strategy and instrument used by Boko Haram to recruit members (Onapajo and Uzodike 2012; Voll 2015). Most studies on terrorism and Boko Haram have cited radicalization, false teachings, and misrepresentation of religion by rogue clerics to hypnotize, and recruit unsuspecting individuals into joining terrorist organizations.15 Studies by Onuoha (2014a, 2014b; Olojo 2017) revealed that these radical clerics capitalized on the socio-economic and cultural challenges facing the northeast region to indoctrinate people into believing that their problems resulted from Western civilization. This negative sentiment about western civilization was re-echoed by a journalist who conducted a series of studies on the insecurity in the northeast16 and a former commander17 of the MNJTF, who maintained that since ‘Boko Haram’ is against ‘Western education and civilization’, which it perceives to be anti-Islam, it should not surprise people that the organization uses the false narrative to appeal to the hearts and minds of people. This is because Muhammed Yusuf, the founding leader of Boko Haram, attracted followers because of his anti-Western sentiments and teachings, who were largely uneducated, unschooled, impressionable, poor, and frustrated by the status quo.18 This is a strategy the organization continues to use to recruit and expand its base across the Lake Chad region (See Sigelmann 2019).

The negligence and inability of the government to address certain basic fundamental issues affecting the northeast region contribute to increasing the space for Boko Haram to thrive and expand its activities (Sigelmann 2019). The inability of the Nigerian government to address the problems of unemployment, human rights abuses, poverty, social exclusion, radicalization, illiteracy, inequality, and the provision of basic social services to its citizens created the opportunity for radical, violent extremist, and terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram to not only assume the place of the government, but also expand its membership (Campbell 2013, 2018a, 2018b; Matfess 2016, 2017; Magrin and De Montclos 2018). The abdication of responsibility by the government in the northeast resulted in people resorting to seek help from Boko Haram to provide basic services such as water, food, and medical supplies (Sahara Reporters 2019). A former resident of Bama in Maiduguri revealed that Boko Haram not only supply food in some of these villages, but they also collect taxes and provide security for members of such communities. Through that, members of such villages not only see an alternative government in Boko Haram, but it motivates them to join the organization.19 Therefore, so long as the government continues to show this level of negligence and failure in addressing the issues and challenges affecting the people of the northeast and the Lake Chad region, Boko Haram will continue to exploit these lapses and attract more fighters into its ranks.

These tactics reflect why and how the terrorist group continues to expand and consolidate its base across the Lake Chad despite the various measures countering it.

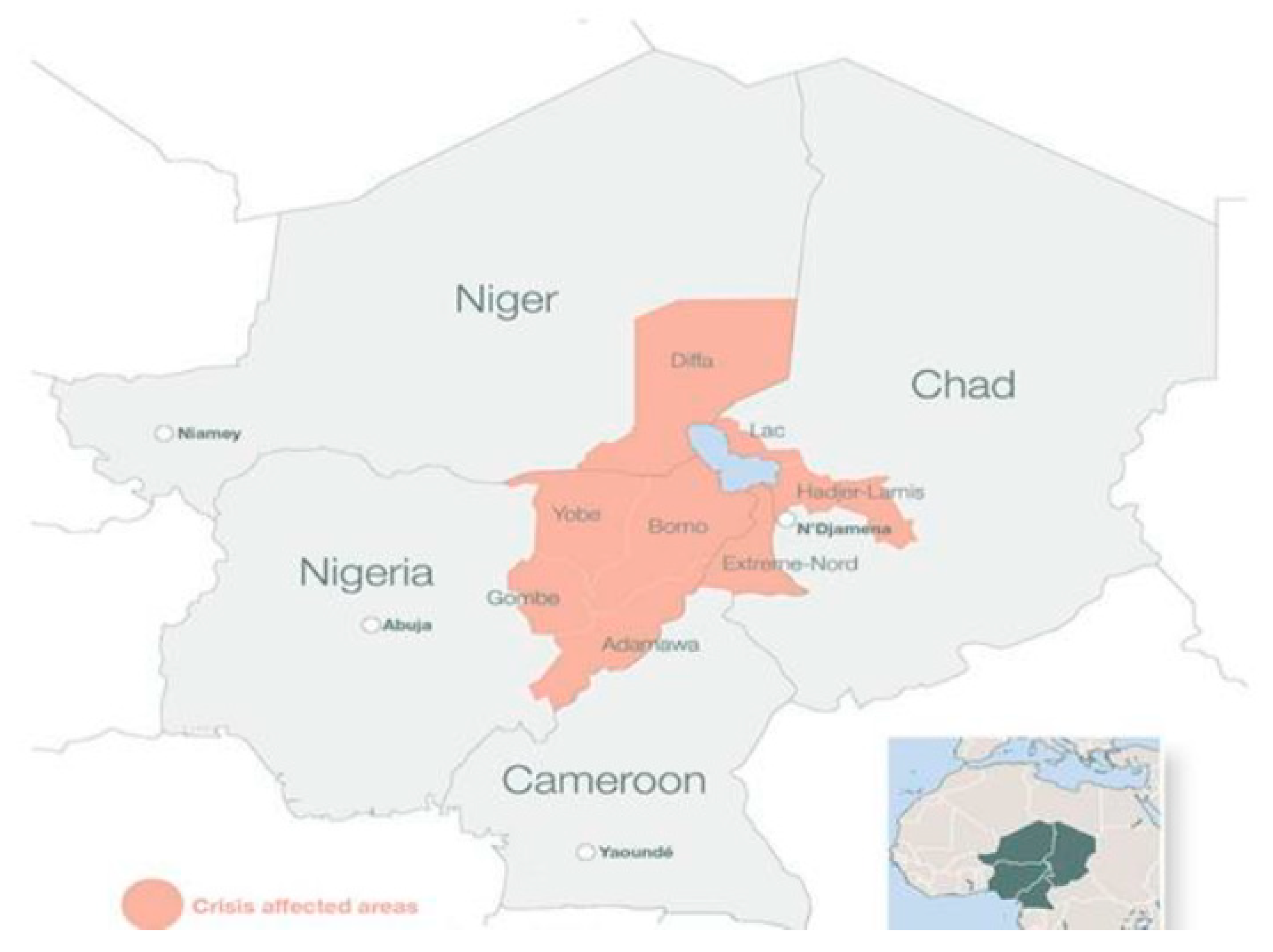

The figure below (Figure 1) presents a pictogram map of the four countries of the Lake Chad region affected by the activities of Boko Haram.

Figure 1.

The affected countries of the Lake Chad region. Source: Smith 2016. “The Lake Chad crisis explained”.

4. What Are the Efforts and Strategies towards Preventing Boko Haram’s Recruitment: National, Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and Faith-Based Organizations (FBOs), Sub-Regional and Regional Responses?

This part of the article is categorized into three sub-sections. The first section examines the response at the national level, where the emphasis was on the administrative and legislative roles initiated by the Nigerian government to counter Boko Haram’s recruitment. Also, the analysis goes further to examine the roles played by religious groups (faith-based organizations) and civil society organizations in stemming the recruitment strategy deployed by Boko Haram. The third sub-section examines the role of sub-regional and regional actors such as the Lake Chad Basin Commission (LCBC), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the African Union (AU) in countering the recruitment ability of Boko Haram operating in the Lake Chad area.

4.1. National Response

The statement made by President Muhammadu Buhari of Nigeria at the 73rd session of the United Nations General Assembly that “the terrorist insurgencies we face, particularly in the Sahel and Lake Chad Basin, are partly fueled by local factors and dynamics, but now increasingly by the international jihadi movement, runaway fighters from Iraq and Syria and arms from the disintegration of Libya,” and called for global action to counter the threats of terrorism (United Nations News 2018). This statement not only further explains the changing tides of insecurity in Lake Chad, but also the capacity of terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram and its splinter group, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), to recruit, expand, and continue to carry out several attacks across the northeast and Lake Chad region (Salkida 2019).

Various studies (Agbiboa 2015; Oyewole 2015; Assanvo et al. 2016; Bappah 2016) have reflected on several efforts by states and non-state actors at the national, sub-regional, and regional levels to counter the operational capacity of Boko Haram to recruit and carry out attacks. At the national level, the Nigerian government has engaged in a series of administrative, legislative, and inter-agency collaboration efforts between local institutions and international agencies to counter the activities of Boko Haram.

Some of the administrative measures adopted by the Nigerian government included: the multi-track approach, which involved persuasion, dialogue, and consultation with political, religious, and community leaders in the states and communities affected by activities of the terrorist group to counter the narratives of radicalization and other negative doctrinal elements (Olojo 2017, 2019); the declaration of a state of emergency in Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states accompanied by the five-year trade embargo placed along ‘Dikwa-Maiduguri-Gamboru-Ngala routes’ to interdict the transnational crime activities by Boko Haram (Sahara Reporters 2013; Samuel 2019); and the launch of the National Action Plan for Preventing and Countering Extremism in 2017 to strengthen the capacity of agencies to tackle violent extremism, enforce the rule of the law and human rights, enhance effective community engagement, capacity building and resilience to counter violent extremism, resilience, and strategic communication by various stakeholders and actors in the society (Ogunmade and Olugbode 2017).

Furthermore, other initiatives were launched such as the ‘Buhari Plan of 2016’ for effective and transformative engagement between the government, religious organizations, and communities affected by the activities of Boko Haram in the northeast (see African Union 2018, p. 17). The newly established ‘Presidential Committee on the North-East Initiative’ was saddled with the responsibility of developing a comprehensive strategy towards rehabilitating, reintegrating communities, rebuilding and reconstructing the northeast (Punch News 2016). The launching of the ‘Operation Safe Corridor’ was aimed at addressing challenges associated with terrorist recruitment, violent extremism, deradicalization, rehabilitating and reintegrating repentant Boko Haram terrorists back to society after undergoing various stages of thorough psycho-spiritual therapy and evaluations by religious clerics and psychology experts (DW News 2019).

Due to the fact that terrorist recruitment is connected to the capacity of terror groups to fund their operations (Clarke 2015), the Nigerian government is a member of the Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa in line with the mandate of the Financial Action Taskforce on Counter-Terrorism Financing (See GIABA Report 2015; Financial Action Task Force 2016). At the legislative level, the National Assembly comprising the Senate and the House of Representatives amended the 2011 Terrorism (Prevention) Act. The amended law was expected to support inter-agency counterterrorism collaboration between various actors to combat terrorism. It strengthened the capacity of law enforcement officers to detain and prosecute individuals suspected to be sponsors and members of terrorist organizations (see Federal Government Nigeria 2011). It also boosted the capacity of institutions to deal with the sponsors of terror-related activities. The amendment further allowed for the death penalty to be given as punishment for individuals and groups found guilty of committing and facilitating acts of terror in the country (See Federal Government Nigeria 2011, 2013). This legislation further strengthened the Money Laundering Prohibition Act of 2011 and also led to the establishment of the National Financial Intelligence Unit (NFIU) by financial institutions to prevent terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram from not only funding their operations, but also expanding their activities by recruiting fighters (see Nigerian Financial Intelligence Unit 2018).

4.2. Response from Faith-Based Organizations and Civil Society Organizations

Studies have shown that the Muslim and Christian communities and places of worship constitute the sectors that are mostly affected by the attacks carried out by Boko Haram across Lake Chad with over 2134 fatalities recorded across both communities in 2018 (see Nigeria Watch 2019). These attacks further affected the already deplorable and tense Christian–Muslim relations that have characterized most of the conflicts and tensions between these two religions in recent years (Michael Kpughe 2017; Faseke 2019; Nche et al. 2019).

Despite the attacks on religious institutions by Boko Haram, under the broader Coalition of Civil Societies with over 5000 registered agencies, the two dominant religions have engaged in various ‘non-violent’ engagements to fight against the forces of violent extremisms, radicalization, and terrorist recruitment across the Lake Chad region (See Mahmood and Ani 2018). Religious leaders also use their understanding of the true doctrinal principles to discourage the narrative and ideological propaganda employed by Boko Haram to recruit fighters (Olojo 2017, 2019). An example can be seen in Sokoto State where the Muslim Umma (Muslim Community) stopped and chased Kabiru Sokoto20 out of the state in order to prevent the indoctrination of people through his radical ideology (Adamu 2012).

Furthermore, through effective collaboration between these religious bodies and civil society organizations, several initiatives, peace concerts, and peacebuilding outreaches were implemented in various areas affected by the threat of Boko Haram.21 As informed by one interviewee, one of such initiative was the Hadin Kan Mu Karfin Mu (Our Unity, Our Strength) and the Ido da Ido (Face to Face) project organized by International Alert Nigeria (IAN)22 in July 2019, with the support of religious groups and the communities of Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states23 considered to be the three states most affected by the activities of the insurgents (See Zirima 2018). This initiative was aimed at “Reinforcing the Resilience and Re-integration of Women and Children, Promoting Peacebuilding in Communities affected by Boko Haram and strengthening effective engagement between community vigilantes and security officers across affected areas.”24 It was expected that this project would help targeted groups address the problems of radicalization, lack of diversity management, mutual coexistence, and intolerance, and help strengthen mutual trust amongst communities irrespective of their religious beliefs for sustainable peace.25 Also, a decision was made by the Borno State government and the Borno State Islamic Association to establish peace clubs, as well as to design the curriculum used by educators for the teaching of peace studies for children attending the Western schools at both the primary and secondary level, and also those children attending religious schools or Madrasas (See TRT World News 2018). The adoption and establishment of peace studies and peace clubs will help inculcate sound doctrinal teachings in line with the dictates of the holy books (Bible and Quran) and also counter the negative narratives and ideologies used by extremist groups to recruit children.26

These initiatives contributed to raising awareness on the dangers of extremism, promoted social cohesion and mutual trust amongst various communities and groups affected by the activities of the terrorists.27 This sentiment was also shared by Nigeria’s Chief of Army Staff Major General Tukur Buratai in a seminar organized by the Nigerian Army Directorate of Chaplain Services, and Directorate of Islamic Affairs with the theme “Countering Insurgency and Violent Extremism in Nigeria through Spiritual Warfare”, where he called on religious groups and leaders to support the state in eradicating the negative use of religion and ideology to fuel insurgency in the country (Nigerian Tribune 2019). He argued that “defeating the ideologies of Boko Haram and ISWAP requires actors to first realize that it was this negative use of ideologies that enhanced the resource base and ability of these terror groups to recruit fighters to join their crusade” (see Premium Times 2019). Therefore, terrorism will wither if these negative forces of radicalization are eradicated. This can only be achieved through concerted efforts and the continuous interface between religious leaders, groups, communities, and the military in countering these radical ideologies and protecting vulnerable groups from falling victim to extremists’ beliefs and doctrines (Premium Times 2019).

Therefore, it is important to note that continuous emphasis on inter-faith dialogue and cross-cultural engagements between locals, religious and civil societies on peaceful coexistence, tolerance, and deconstructing the narrative that no religion supports violence can contribute to curbing the threat of terrorism, including its efforts to recruit and expand (Michael Kpughe 2017; Olojo 2017; Salifu and Ewi 2017; Brechenmacher 2019).

4.3. Sub-Regional and Regional Response

As a member of the Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership (TSCTP)’ and the Islamic Military Alliance (IMA)’, Nigeria continue to engage with states and non-state actors at the international level to counter extremist messaging, narratives, and ideologies used by Boko Haram and other terrorist organizations to recruit members (Agence France Presse 2016; Martin 2018; United Nations 2018). The Regional Strategy for the Stabilization, Recovery, and Resilience (RSSRR) was launched in the areas affected by the activities of the Boko Haram terrorists by the Lake Chad Basin Commission, with support from the African Union, United Nations, and other non-state actors. The RSSRR strategy offers a multidimensional approach that allows governments, civil societies, religious organizations, and communities to strengthen the institutional capacity to combat terrorism and all its imprints in the region (see African Union 2018). These engagements, partnerships, and initiatives established by states and non-state actors in stemming the recruitment capacity of Boko Haram in the Lake Chad region were expected to not only identify the key drivers of public support for terrorist organizations, but also counter the negative ideologies and the various methods used by terrorist groups to consolidate and expand their operations through recruitment.28

The joint military coalition between member states of the Lake Chad Basin Commission under the Multinational Joint Taskforce (MNJTF) achieved some success by limiting the territorial expansion of the terrorist organization to other parts of the continent and degrading its capacity to carry out coordinated attacks (Iwuoha 2019). The recapturing of Baga and other communities previously controlled by the terrorists affected their ability to recruit and fund their operations.29

To conclude this section, it has been argued that the measures and initiatives taken by stakeholders at the national, sub-regional, and regional levels achieved some success in preventing the recruitment ability and territorial expansion of Boko Haram from spreading to other parts of the continent by limiting their presence to the Lake Chad region (see News Express 2015; Lake Chad Basin Commission News 2019). The trade blockade along Dikwa–Maiduguri–Gamboru–Ngala trading routes impacted the illicit funding of activities by this group, thus hindering its capacity to attract further fighters (Omenma 2019; Samuel 2019). The continuous engagement and the role played by faith-based organizations and clerics across the northeast and Lake Chad in deconstructing the negative narratives and propaganda used by Boko Haram to project their religious and ideological sentiments affected their expansion and recruitment capacity (Olojo 2017; Michael Kpughe 2017; ACN News 2018).

5. What Are the Challenges Facing Stakeholders in Combating Boko Haram’s Recruitment?

The various initiatives designed to counter the operational capacity of Boko Haram to recruit and expand its activities face a series of challenges. This is because, despite these measures, the group continues to thrive by attracting fighters across Lake Chad (Punch News 2017; Sigelmann 2019). During one interview, one informant expressed the opinion that one challenge confronting actors in countering the recruitment of individuals into extremist and terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram, is “the ignorance and belief by actors that there is a universal solution to counterterrorism without clearly understanding the context, local dynamics, and situations that allows terrorism to thrive. This is because, individuals are motivated and driven by several reasons to join terrorist groups”.30 Therefore, the inability of actors to understand and identify reasons individuals join terrorist organizations impedes any counterterrorism strategy designed to combat terrorist recruitment by actors.31 This narrative is supported in several studies, which suggest that the complexity of the conflict in the Lake Chad where multiple terror groups like Boko Haram and its factional group Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP) are involved in the conflict, with each group having its separate rules of engagement and modus operandi (Bappah 2016; Anyadike 2018). This makes it difficult for actors to defeat them using the current state-centric or military strategy (Munshi 2018; Mentone 2018; Salkida 2019). This is because the current approach is not only reductive, but also fails to involve all relevant stakeholders in countering terrorist threats (see International Crisis Group 2016; Salkida 2019). It also does not identify the drivers of the conflict, guarantee stability of the region, enhance social cohesion, and seek sustainable solutions that will stem violent extremism, terrorist recruitment, and terrorism across the Lake Chad region (Sigelmann 2019; Zenn 2019). That explains the recent calls by actors and stakeholders to change the strategy by incorporating a multidimensional approach that will incorporate all relevant actors when tackling terrorism in the Lake Chad region to reflect the current realities and dynamics of the conflict (Olojo 2019).

Another challenge confronting actors is the technological deficit and lack of trust among actors involved in managing the conflict and communities affected by Boko Haram to identify threat forces affecting the fight against terrorism recruitment.32 The accusation and perception that members of the MNJTF and individuals in the host communities act as double agents and informants for the terrorists affects any approach to counter and limit the activities of Boko Haram across the northeast and Lake Chad region (Agbiboa 2018). This is because increasingly, soldiers and officers of the MNJTF are accused of divulging sensitive operational and tactical information to the insurgents, supplying them with weapons and aiding their illicit trafficking of stolen goods and other contraband products across Lake Chad (Dietrich 2015; Solomon 2017; Premium Times 2018). That has impacted negatively on the image of members of the security sector, where several reports and commissions of inquiries have accused the military of committing a series of human rights violations such as rape, extortion, extra-judicial killings, looting of properties, arresting innocent locals, and branding other communities as suspect areas (See Galtimari 2011; Abbah 2012; Amnesty International 2018). This has negatively impacted the civil-–military relations amongst communities and soldiers across Lake Chad, as locals often clash with soldiers accusing them of collaborating with Boko Haram for financial settlements (Agbiboa 2018). This negative perception complicates any avenue for effective civil–military engagement, support, and trust between the military institutions and communities affected by the terror acts committed by Boko Haram. This high level of mistrust affects any response towards preventing Boko Haram’s recruitment capacity as well as stopping them from carrying out various acts of barbarity.33

The lack of trust in the management and utilization of intelligence amongst actors has been revealed by various studies, which highlighted the importance of having an effective surveillance and intelligence system to assess, monitor and report threats of terror-related activities (Donovan et al. 2016; Göpfert 2016; Agbiboa 2014, 2018). This level of mistrust affects any effort by relevant actors to combat the activities of terrorist organizations such as Boko Haram to recruit and carry out attacks across the northeast (Brechenmacher 2019). This position also reflects the eyes on the street analogy put forward by Agbiboa34, which points out the failure of relevant actors to combat Boko Haram’s recruitment strategy and terrorism in the northeast. Despite its effectiveness in managing threats and threats perceptions, this approach could not yield the desired result due to levels of mutual suspicion between security forces and members of community continuing to grow, the non-involvement of locals in counterterrorism efforts, and the fear of being branded as an informant for or against Boko Haram (Reuters 2011; Nnodim and Olaleye 2017; Brown 2018). Consequently, individuals are reluctant to report on the workings of the terrorist group and persons suspected to be affiliated to Boko Haram due to fear of reprisals. Additionally, the fact that Boko Haram predominantly uses non-formal financial institutions to control its finances also makes it difficult for banks and other financial regulators to report any suspicious activities that facilitate acts of terror (see Financial Action Task Force 2016). This is because Boko Haram relies on non-formal channels to fund its activities, such as the collection of tax from locals, robberies, proceeds from kidnapping, and other transnational criminal activities, which makes it difficult for banks to track and report funds suspected to be for terror-related activities.35 Therefore, the inability of the relevant actors to stem the flow of cash by Boko Haram to stop their ability to recruit also presents certain challenges.36

Combating terrorist recruitment and elements of terrorism in society require the state and its various agencies to show the capacity to coerce and convince citizens it has the ability to end it.37 As the state has not been able to demonstrate that commitment, questions regarding its commitment and legitimacy have arisen.38 Contextualizing this narrative in combating Boko Haram recruitment strategy as well as the conflict, the Nigerian government and other multilateral agencies have not demonstrated that they have the ability to confront this challenge.

Several factors contribute to the inability of the state and its agencies to coerce and convince citizens that it has the ability to prevent the recruitment and expansion of Boko Haram across the Lake Chad region. In the aspect of policy operationalization, examples of initiatives such as the National Counter Terrorism Strategy (NACTEST); the National Action Plan for Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (PCVE); the Regional Strategy for the Stabilization, Recovery, and Resilience; National Counter-Terrorism Strategy (NCTS); amongst other laudable strategies designed by the government and other multilateral institutions in the region to tackle radicalization and other conditions leading to violent extremism are yet to make any significant impact in addressing the security challenges in the Lake Chad region39 (See also European Commission 2017; African Union 2018; Mentone 2018; Innocent 2018). The influx of foreign terrorist fighters accompanied by the illicit trafficking of arms, drugs, and other transnational criminal activities across the Lake Chad region also highlight the failure of the governments across the region to control and secure their borders against external threats (Oyewole 2015; Obamamoye 2019). The poor attitude of the leaders of member countries of the Lake Chad Basin Commission towards the deteriorating effect of climate change is a factor in creating the preconditions for Boko Haram to recruit, thrive, and expand its activities across Lake Chad (Gulland 2019). The effect of this further led to the displacement, instability, and inter-group relations of communities inhabiting the Lake Chad region (Doherty 2017; See Vivekananda et al. 2019). The negligence by the political actors allowed Boko Haram to have control of resources across Lake Chad (United Nations 2018). This has not only enabled them to recruit fighters, but also to gain ammunition for its operations (Gerretsen 2019). There has been a lack of unison in inter-agency collaboration in combating the threat of this terrorist group (United Nations 2018). The endemic corruption and lack of accountability by actors involved in combating the threat by Boko Haram has contributed to fueling the conflict (Hashimu and James 2017; Searcey and Emmanuel 2019). This is because stakeholders involved in stemming the activities of Boko Haram converted the conflict into an avenue for ‘rent-seeking’ and a ‘cash-cow’ business (BBC News 2016). This explains why despite the huge budgetary allocations, the architects of the security sector cannot address the insecurity in Lake Chad.40 Many were of the view that the fact that a ‘ragtag army’ such as Boko Haram could overcome a trained army demonstrates the high level and depth of corruption in the counterterrorism efforts in the northeast and Lake Chad region.41 These factors show the failure and inability of the state and its agencies to show its capacity to coerce and convince citizens that it has the ability to tackle the challenges of terrorism and insecurity across the Lake Chad region.

6. Conclusions

This article aimed to examine the challenges confronting stakeholders in addressing the various strategies and methods of recruitment used by the Boko Haram terrorist group across the Lake Chad region. To do that, the article focused on understanding the recruitment strategies of terrorist organizations within the context of Boko Haram, assessed the various countermeasures by relevant stakeholders at the national, sub-regional, and regional levels and the challenges confronting them in curbing the threat of terrorist recruitment across the Lake Chad region.

The findings of the article suggest that Boko Haram, like most terrorist organizations, sustains itself by recruiting individuals and groups to carry out its attacks. It achieves that by applying various methods and tactics such as the false of promise of better welfare and economic condition in a society characterized by unemployment, poverty, and the absence of basic services for the people. Through abductions, kidnappings, and threats, individuals and groups are forcefully conscripted into joining Boko Haram. Using cash loans as a means to trap unsuspecting struggling traders by being willing to support their businesses is another strategy used by the terrorist group to recruit people. Finally, the instrumentalization of religion and advancement in information technology, particularly the internet and its social media tools, by the terrorists as a vehicle and a tool to radicalize individuals constitutes another strategy used by Boko Haram for recruitment. They brainwash unsuspecting individuals into believing that Western civilization is not only haram (forbidden), but underscores the essence of traditional family, religious, and societal values exhorted by Islam. Rogue clerics use this negative narrative to attract individuals into joining the movement into believing they are contributing to effecting meaningful social change in society.

The response by stakeholders to counter these strategies included various initiatives, policies, and legislation such as the National Action Plan for Countering Violent Extremism, the Regional Strategy for the Stabilization, Recovery, and Resilience among other multilateral engagements, which yielded minimal results. This is because stakeholders involved in combating the threat of Boko Haram are grappling with challenges relating to the inability to contextually identify the best strategy or approach to confront terrorism recruitment and terrorism in the region. As most terrorist organizations use violence to achieve their aims, countering their threat requires actors to understand the context and local dynamics that drive each terrorist group to determine the right strategy to prevent such groups. Another challenge identified in countering Boko Haram’s recruitment strategy is centered on the gap or deficit in technology and the lack of trust among actors to identify, share, and report threat forces. For example, the lack of trust between officers of the MNJTF and members of affected communities has led to them accusing each other as acting as informants for the terrorists. This affects the efforts to counter the activities of Boko Haram across Lake Chad. The third challenge is related to the inability of the state and its various agencies to show the capacity to coerce and convince citizens that it has the ability to address the threat of insecurity across the Lake Chad region. This is due to different factors such as the failure of the state to implement various counterterrorism policies and initiatives, and the failure to secure and protect national and regional borders, thus creating an avenue for terrorist organizations to recruit and carry out various crimes. There is a lack of inter-agency collaboration to limit the activities of Boko Haram across Lake Chad, thus leading to a failure to address the endemic corruption of stakeholders involved in containing Boko Haram’s presence in the northeast and Lake Chad.

Therefore, the article offers its recommendations and also suggests avenues for further studies as it relates to the measures to be taken by these actors in countering the challenges associated with counter-terrorist recruitment across the Lake Chad region:

- A new counterterrorism strategy should be adopted that is comprehensive, multidimensional, and involves both state and non-state actors (religious institutions, civil societies, non-governmental organizations) to reflect the current realities and challenges of the 21st century.

- Relevant stakeholders should facilitate the implementation of various initiatives such as the National Action Plan for the Prevention of Violent Extremism and other measures designed to curb the activities of terrorist organizations at the local, national, sub-regional, regional, and global levels.

- The sociological, economic, ideological, and religious forces and drivers promoting radicalization and violent extremism across the region should be addressed.

- Religious leaders (clerics) and faith-based organizations across the two dominant religious divides have a role to play in countering the negative ideological and doctrinal teachings used in promoting hate, violent extremism, and tensions in their localities. This can be achieved through emphasis on inter-group relations, cross-cultural engagements, and inter-faith dialogue to foster trust, mutual coexistence, tolerance, and confidence building.

- Actors should engage in capacity-building initiatives that promote technical and vocational training for young people as a source of employment, and a process to grow resilience and prevent them from being easy targets for terrorist recruiters.

- Policies and programs that offer rehabilitation, reintegration, and guarantee the sustainable development of individuals affected by terrorism in the region will be implemented.

- The state and its agencies should convince citizens it has the capacity to address the threat of terrorism by providing effective services and welfare to citizens, and addressing challenges associated with poverty, unemployment, inequality, bad governance, corruption, border porosity, poor education, lack of tolerance, management of diversities, mutual coexistence, bad governance, and corruption amongst others.

- The government and other relevant stakeholders should ensure strict compliance and regulations regarding the activities of Madrasas (religious schools) by ensuring these religious schools are fully licensed, registered, and their teachings are strictly in line with true doctrinal principles and ideals to prevent the exposure of children to negative and extremist religious doctrines.

- Within the context of Boko Haram and the insecurity in Lake Chad, relevant stakeholders should ensure that the channels used by this terrorist group to fund its activities are blocked. First, this involves the use of formal and informal institutions (banks, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission) to effectively monitor and track their source of funding. Secondly, stakeholders should reclaim the control of resources (fishing and agricultural products) taking place in the Lake Chad region from the hands of Boko Haram. Finally, stakeholders should stem the illicit movements of contraband products across Lake Chad by the insurgents. These measures will prevent them from recruiting fighters if their sources of funding are stopped.

- The criminal justice system should be strengthened to investigate cases and incidences of human rights violations by actors involved in the counterterrorism effort against Boko Haram, and persons and groups associated with facilitating and supporting the activities of terrorism should be prosecuted.

- Parents have a role to play in ensuring that the negative forces of change and modernization do not in any way affect their children by instilling strict ethical virtues and discipline. Children should be encouraged to understand the value of hard work, honesty, and integrity.

- A community policing model similar to the Nyumba Kumi (Ten Household and Know your Neighbor)42 security initiative should be adopted. This model of community policing has been successful in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda in identifying threat forces and also complements the state security agencies in combating crime and mitigates the strategies used by terrorist groups to recruit and expand their activities (Ndono et al. 2019). This security initiative has been effective in strengthening the relationship and trust between locals and law enforcement officers in addressing the challenges of insecurity in East Africa (Ibid). It also contributes to promoting social cohesion, accountability, inter-religious and communal trust among groups in the society as witnessed in Nakuru County in Kenya (Andhoga and Mavole 2017). In a phone interview, an informant revealed that this initiative is an important tool in combating crime, insecurity, and terrorism in the Horn of Africa.43 This is because most societies in East Africa have a 1 to 1000 ratio of security officers to civilians; therefore, the adoption of the Nyumba Kumi can help to bridge the gap between locals and the police by acting as their ‘ears to the ground and eyes on the street’ on threat assessment and intelligence44. This makes it difficult for criminals and terrorist organizations to exploit any avenue to radicalize, recruit, plan, and organize attacks (Ibid). This security initiative has been successful, as witnessed in Tanzania (Sambaiga 2018). The initiative was said to have achieved some level of success in the Kayole and Eastleigh communities in Nairobi, Isiolo County, the coast of Mombasa in Kenya, and some parts of Adjumani District in Uganda by neutralizing the activities of bandits and persons suspected to be associated with Al-Shabaab and the Allied Democratic Forces terrorist groups (Kenya News Agency 2019; IOM UN Migration News 2019). With the successes recorded by this security initiative, the application of a similar model in the Lake Chad region by relevant stakeholders will help to address the challenges of insecurity as well as prevent terrorist groups such as Boko Haram from expanding their activities in the region.

- Although this study focused on Boko Haram’s recruitment across the Lake Chad region, we believe there is connection between the recruitment strategies of Boko Haram and other radical extremist groups such as Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM), the Movement for the Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) operating across the Lake Chad and Sahel region in West Africa, which other studies can explore.

- A comparative approach to available data is also recommended, as it is likely to present the various operational levels of the terrorist groups across the Lake Chad region in order to fully understand their strategies for recruitment as well as the push and pull factors motivating individuals to joint these terrorist groups.

- In addition to areas for further research, future researchers should try to explore issues related to the current figure of Boko Haram recruits, whether they are rising or falling across Lake Chad, what happens to the repentant and rehabilitated Boko Haram fighters, and how they are integrated back to society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.D.M. and U.K.; methodology, K.D.M., U.K. and S.A.; formal analysis, K.D.M., U.K. and S.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D.M.; writing—review and editing, K.D.M., U.K. and S.A.; supervision, U.K. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbah, Theophilus. 2012. White Paper on Insecurity: Report Links Boko Haram with London Scholar. Daily Trust, June 3. [Google Scholar]

- Abrak, Isaac. 2016. Boko Haram Using Loans to Recruit Members in Face of Crackdown. The Guardian, May 9. [Google Scholar]

- ACN News. 2018. Nigeria: In the face of ongoing Islamist attacks, the faith is growing. ACN News. February 12. Available online: https://www.churchinneed.org/nigeria-face-ongoing-islamist-attacks-faith-growing/ (accessed on 13 September 2019).

- Adamu, Lawan Danjuma. 2012. Nigeria: The Untold Story of Kabiru Sokoto. Daily Trust. February 12. Available online: https://allafrica.com/stories/201202130754.html (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Adegbulu, Femi. 2013. Boko Haram: The emergence of a terrorist sect in Nigeria 2009–13. African Identities 11: 2602–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelani, Adepegba, Gbenro Adeoye, Jesusegun Alagbe, and Tunde Ajaja. 2017. 6000 ISIS fighters may join forces with Boko Haram–Experts. Punch News. December 16. Available online: https://punchng.com/6000-isis-fighters-may-join-forces-with-bharam-experts/ (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- Adnan, Abu. 2019. 8000 children recruited by Boko Haram: UN. Anadolu Agency, July 8. [Google Scholar]

- African Union. 2018. Regional Strategy: For the Stabilization, Recovery & Resilience of the Boko Haram affected Areas of the Lake Chad Basin Region. Available online: http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/rss-ab-vers-en..pdf (accessed on 19 August 2019).

- Agbiboa, Daniel E. 2014. Peace at Daggers Drawn? Boko Haram and the state of emergency in Nigeria. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 37: 41–67. [Google Scholar]

- Agbiboa, Daniel E. 2015. Resistance to Boko Haram: Civilian Joint Task Forces in North-Eastern Nigeria. Conflict Studies Quarterly. Special Issue 1–20. Available online: http://www.csq.ro/wp-content/uploads/1-Daniel-AGBIBOA.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- Agbiboa, Daniel E. 2018. Eyes on the street: Civilian Joint Task Force and the surveillance of Boko Haram in northeastern Nigeria. Intelligence and National Security 33: 1022–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbiboa, Daniel E. 2019. Ten years of Boko Haram: How transporation drives Africa’s deadliest insurgency. Cultural Studies, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agence France Presse. 2016. Army chiefs of ‘anti-terror’ coalition meet in Saudi. Agence France Presse. March 27. Available online: https://www.yahoo.com/news/army-chiefs-anti-terror-coalition-meet-saudi-173438249.html (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Aghedo, Iro. 2014. Old wine in a new bottle: ideological and operational linkages between Maitatsine and Boko Haram revolts in Nigeria. African Security 7: 229–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala, Olayinka. 2018. Formation of Insurgent Groups: MEND and Boko Haram in Nigeria. Small Wars & Insurgencies 29: 112–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, Omeiza. 2014. Boko Haram Begins Forced Recruitment. National Mirror, July 22. [Google Scholar]

- Amaechi, Kingsley Ekene. 2017. From non-violent protests to suicide bombing: social movement theory reflections on the use of suicide violence in the Nigerian Boko Haram. Journal for the Study of Religion 30: 52–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ameh, Comrade Godwin. 2014. Some Chibok Girls are Pregnant, Others May Never Return–Obasanjo. Daily Post, June 13. [Google Scholar]

- Amnesty International. 2018. ‘They Betrayed Us’: Women Who Survived Boko Haram Raped, Starved and Detained in Nigeria. Amnesty International Report. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/AFR4484152018ENGLISH.PDF (accessed on 30 April 2019).

- Andhoga, Walter Otieno, and Johnson Mavole. 2017. Influence of Nyumba Kumi Community Policing Initiative on Social Cohesion among Cosmopolitan Sub Locations in Nakuru County. International Journal of Social and Development Concerns 1: 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Anyadike, Obi. 2018. Year of Debacle: How Nigeria lost its way in the War against Boko Haram. World Politics Review, October 30. [Google Scholar]

- Archetti, Cristina. 2013. Terrorism, Communication, and the Media. In Understanding Terrorism in the Age of Global Media: A Communication Approach. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 32–59. [Google Scholar]

- Asal, Victor, Luis De la Calle, Michael Findley, and Joseph Young. 2012. Killing civilians or holding territory? How to think about terrorism. International Studies Review 14: 475–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assanvo, William, Jeannine Abatan, and Wendyam Aristide Sawadogo. 2016. West Africa Report: Assessing the Multinational Joint Task Force against Boko Haram. Institute for Security Studies. West Africa Report. Available online: https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/war19.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Ayegba, Usman Solomon. 2015. Unemployment and Poverty as Sources and Consequence of Insecurity in Nigeria: The Boko Haram insurgency revisited. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations 9: 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Azumah, John. 2015. Boko Haram in Retrospect. Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 26: 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, Olalekan A. 2018. The Recruitment Mode of the Boko Haram Terrorist Group in Nigeria. Peace Review 30: 382–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bappah, Habibu Yaya. 2016. Nigeria’s military failure against the Boko Haram insurgency. African Security Review 25: 146–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. 2016. Nigeria officials ‘stole $15bn from anti-Boko Haram Fight. BBC News. May 3. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-36192390 (accessed on 9 August 2019).

- BBC News. 2019. Nigeria: ‘Children used’ as suicide bombers in Borno attack. BBC News, June 18. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Collin J. 2008. The contribution of social movement theory to understanding terrorism. Sociology Compass 2: 1565–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergesen, Albert J., and Omar Lizardo. 2004. International terrorism and the world-system. Sociological Theory 22: 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Mia. 2017. Constructing expertise: Terrorist recruitment and “talent spotting” in the PIRA, Al Qaeda, and ISIS. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 40: 603–23. [Google Scholar]

- Brechenmacher, Saskia. 2019. Stabilizing Northeast Nigeria after Boko Haram”. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, May 3. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, Joe. 2013. Insight: Boko Haram, Taking to Hills, Seize Slave ‘Brides’. Reuters, November 17. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Velbab F. 2018. Nigeria’s troubling counterinsurgency strategy against Boko Haram: How the military and militias are fueling insecurity. Foreign Affairs, March 30. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, John. 2013. Should US fear Boko Haram. CNN, October 1. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, John. 2018a. Boko Haram Faction Reportedly Collecting Taxes in Northeast Nigeria. Council on Foreign Relations, May 24. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, John. 2018b. Boko Haram overruns Nigerian Military base. Council on Foreign Relations, November 27. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, Brendon, and Wisdom Iyekekpolo. 2018. Explaining Transborder Terrorist Attacks: The Cases of Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab. African Security 11: 370–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiluwa, Innocent. 2015. Radicalist discourse: A study of the stances of Nigeria’s Boko Haram and Somalia’s Al Shabaab on Twitter. Journal of Multicultural Discourses 10: 214–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Global Television Network. 2017. New Figures put Boko Haram Death Toll at 100,000, China Global Television Network. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2uM9ppHmpk8 (accessed on 13 December 2018).

- Clarke, Collin P. 2015. Terrorism, Inc.: The Financing of Terrorism, Insurgency, and Irregular Warfare: The Financing of Terrorism, Insurgency, and Irregular Warfare. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Clauset, Aaron, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. 2012. The Developmental Dynamics of Terrorist Organizations. PLoS ONE 7: e48633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, Cynthia C. 2017. Terrorism in the Twenty-First Century. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- David, Ojochenemi J., Lucky E. Asuelime, and Hakeem Onapajo. 2015. Boko Haram: the socio-economic drivers. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Del Vecchio, Giorgio. 2016. Political violence as shared terrain of militancy: Red Brigades, social movements and the discourse on arms in the early Seventies. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 8: 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, Kyle. 2015. When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy: Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency. Center for Civilians in Conflict. Available online: https://civiliansinconflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NigeriaReport_Web.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Dixon, Robyn. 2014. Young Women Used in Nigerian Suicide Bombings. Los Angeles Times, July 30. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, Ben. 2017. Climate Change will fuel Terrorism recruitment: Report for German Foreign Office says. The Guardian, April 19. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, Kevin P., Philippe M. Frowd, and Aaron K. Martin. 2016. ASR Forum on surveillance in Africa: Politics, histories, techniques. African Studies Review 59: 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowd, Caitriona, and Adam Drury. 2017. Marginalisation, insurgency and civilian insecurity: Boko Haram and the Lord’s Resistance Army. Peacebuilding 5: 136–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- DW News. 2019. Boko Haram: Nigeria Moves to Deradicalize Former Fighters. DW News. August 8. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/boko-haram-nigeria-moves-to-deradicalize-former-fighters/a-49950707 (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Eke, Surulola James. 2015. How and why Boko Haram blossomed: Examining the fatal consequences of treating a purposive terrorist organisation as less so. Defense & Security Analysis 31: 319–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ette, Mercy, and Sarah Joe. 2018. ‘Rival visions of reality’: An analysis of the framing of Boko Haram in Nigerian newspapers and Twitter. Media, War & Conflict 11: 392–406. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2017. European Commission. 2017. Preventing Violent Extremism in Nigeria: Effective Narratives and Messaging. National Workshop Report. Available online: http://www.clubmadrid.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2.-Nigeria_Report.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Faria, João Ricardo, and Daniel G. Arce M. 2005. Terror support and recruitment. Defence and Peace Economics 16: 263–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faseke, Babajimi Oladipo. 2019. Nigeria and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation: A Discourse in Identity, Faith and Development, 1969–2016. Religions 10: 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Government Nigeria. 2011. Money Laundering (Prohibition) Act, 2011 (As Amended), Harmonized Act No. 11, 2011; Abuja: Federal Ministry of Justice.

- Federal Government Nigeria. 2013. Central Bank of Nigeria (Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism in Banks and other Financial Institutions in Nigeria) Regulations; Lagos: Federal Government Printer.

- Felter, Claire. 2018. Nigeria’s battle with Boko Haram. Council on Foreign Relations. August 8. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/nigerias-battle-boko-haram (accessed on 17 September 2019).

- Fessy, Thomas. 2016. Boko Haram Recruits Were Promised Lots of Money. BBC News. March 25. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-35898319/boko-haram-recruits-were-promised-lots-of-money (accessed on 5 July 2019).

- Financial Action Task Force. 2016. Terrorist Financing in West Africa and Central Nigeria. FATF Report. Available online: https://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Terrorist-Financing-West-Central-Africa.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Forest, James J. F., ed. 2006. The Making of a Terrorist: Recruitment, Training, and Root Causes. Santa Barbara: Praeger Security International. [Google Scholar]

- Gaffey, Connor. 2016. Boko Haram’s Business Model: Poor Nigerian Youths given Loans to join militant group. Newsweek, April 13. [Google Scholar]

- Galehan, Jordan N. 2019. Boko Haram deploys lots of women suicide bombers. I found out why. The Conversation, June 13. [Google Scholar]

- Galtimari, Usman Gaji. 2011. Final Report of the Presidential Committee on Security Challenges in the North-East Zone of Nigeria. Abuja: Federal Government of Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, Scott, and Sukanya Podder. 2015. Social media, recruitment, allegiance and the Islamic State. Perspectives on Terrorism 9: 107–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, Caron. 2004. The Relationship between New Social Movement Theory and Terrorism Studies: The Role of Leadership, Membership, Ideology and Gender. Terrorism and Political Violence 16: 274–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerretsen, Isabelle. 2019. How Climate Change is fueling extremism. CNN News, March 10. [Google Scholar]

- GIABA. 2015. Seventh Follow Up Report Mutual Evaluation: Nigeria. Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa. Available online: https://www.giaba.org/media/f/932_7th%20FUR%20Nigeria%20-%20English.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2019).

- Göpfert, Mirco. 2016. Surveillance in Niger: Gendarmes and the Problem of “Seeing Things”. African Studies Review 59: 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gray, Simon, and Ibikunle Adeakin. 2015. The evolution of Boko Haram: From missionary activism to transnational jihad and the failure of the Nigerian security intelligence agencies. African Security 8: 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadagno, Rosanna E., Adam Lankford, Nicole L. Muscanell, Bradley M. Okdie, and Debra M. McCallum. 2010. Social influence in the online recruitment of terrorists and terrorist sympathizers: Implications for social psychology research. Revue Internationale de Psychologie Sociale 23: 25–56. [Google Scholar]

- Guilberto, Kieran. 2016. Boko Haram Lures, Traps Young Nigerian Entrepreneurs with Business Loans. Reuters, April 11. [Google Scholar]