Abstract

Background: Two major bacterial pathogens, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes, are becoming increasingly antibiotic-resistant. Despite the urgency, only a few new antibiotics have been approved to address these infections. Although cannabinoids have been noted for their antibacterial properties, a comprehensive review of their effects on these bacteria has been lacking. Objective: This systematic review examines the antibacterial activity of cannabinoids against S. aureus, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) strains, and S. pyogenes. Methods: Databases, including CINAHL, Cochrane, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science, and LILACS, were searched. Of 3510 records, 24 studies met the inclusion criteria, reporting on the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration of cannabinoids. Results: Cannabidiol (CBD) emerged as the most effective cannabinoid, with MICs ranging from 0.65 to 32 mg/L against S. aureus, 0.5 to 4 mg/L for MRSA, and 1 to 2 mg/L for VRSA. Other cannabinoids, such as cannabichromene, cannabigerol (CBG), and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC), also exhibited significant antistaphylococcal activity. CBD, CBG, and Δ9-THC also showed efficacy against S. pyogenes, with MICs between 0.6 and 50 mg/L. Synergistic effects were observed when CBD and essential oils from Cannabis sativa when combined with other antibacterial agents. Conclusion: Cannabinoids’ antibacterial potency is closely linked to their structure–activity relationships, with features like the monoterpene region, aromatic alkyl side chain, and aromatic carboxylic groups enhancing efficacy, particularly in CBD and its cyclic forms. These results highlight the potential of cannabinoids in developing therapies for resistant strains, though further research is needed to confirm their clinical effectiveness.

1. Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A Streptococcus, GAS) are two of the most dangerous and lethal Gram-positive pathogens globally, responsible for a wide range of infections [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. In 2019, S. aureus was linked to approximately 1.1 million deaths, while GAS caused 0.2 million [2]. While these bacteria have distinct pathogenic characteristics, they are frequently discussed together due to their significant roles as the primary causes of bacterial skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), where they often co-infect [8,9].

The management of SSTIs is becoming increasingly complicated by antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which poses a significant challenge for both S. aureus and S. pyogenes [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. S. aureus is increasingly developing resistance to multiple frontline antibiotics, including amoxicillin–clavulanate, cephalexin, cephalosporins, clindamycin, dicloxacillin, flucloxacillin, and penicillin, which are commonly recommended for the treatment of SSTIs [10,17,18,19,20,21,22]. In 2019, antibiotic-resistant S. aureus was responsible for an estimated 178,000 deaths globally, with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) accounting for approximately 100,000 of these fatalities [21]. Alarmingly, MRSA is progressively acquiring multi-drug resistance, including resistance to several commonly used anti-MRSA antibiotics, such as vancomycin, daptomycin, ceftaroline, and linezolid [23,24,25,26,27,28]. Similarly, GAS has exhibited rising resistance to a range of antibiotics, including penicillin (0–4.2%), clindamycin (0.8–19%), macrolides (0.5–95%), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (1.4–83%), and tetracyclines (14–61%), over the past decade [11,12,19,29,30,31,32]. In 2019, drug-resistant GAS was attributed with 3630 deaths worldwide [21]. Although GAS is generally susceptible to beta-lactam antibiotics, alternative treatments are needed for penicillin-allergic patients and for when resistance is reported [19,29,30].

Given the rise in AMR, co-infection of SSTIs by S. aureus and GAS, and the limited efficacy of conventional treatments, there is an urgent and critical need to explore alternative therapeutic options that can target both S. aureus and S. pyogenes effectively [33]. Recent reviews have highlighted the potential of cannabinoids, particularly cannabidiol (CBD), as promising alternatives due to their antibacterial properties [34,35,36]. Pre-clinical studies prove the antibacterial efficacy of cannabinoids, especially against S. aureus [37,38,39,40]. In addition to their antibacterial properties, cannabinoids possess therapeutic attributes such as anti-pruritic, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and wound-healing effects, which enhance their potential in treating SSTIs [41,42,43]. Notably, a phase II clinical trial of CBD as a topical agent for treating S. aureus nasal colonization has been completed, further supporting its significance [44]. A recent systematic review of preclinical and clinical studies further underscored the wound-healing and antimicrobial benefits of cannabinoids in SSTIs, highlighting their potential as both standalone and synergistic agents [45]. With over 4000 years of documented human use and therapeutic versatility, cannabinoids present a promising avenue for the development of novel treatments for infections caused by S. aureus and GAS [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54].

This systematic and critical review aims to evaluate the antibacterial efficacy of medicinal cannabis against S. aureus and S. pyogenes, including resistant strains. It will also explore potential synergistic applications of cannabinoids and examine the structure–activity relationships of active compounds to understand their therapeutic mechanisms better.

2. Results

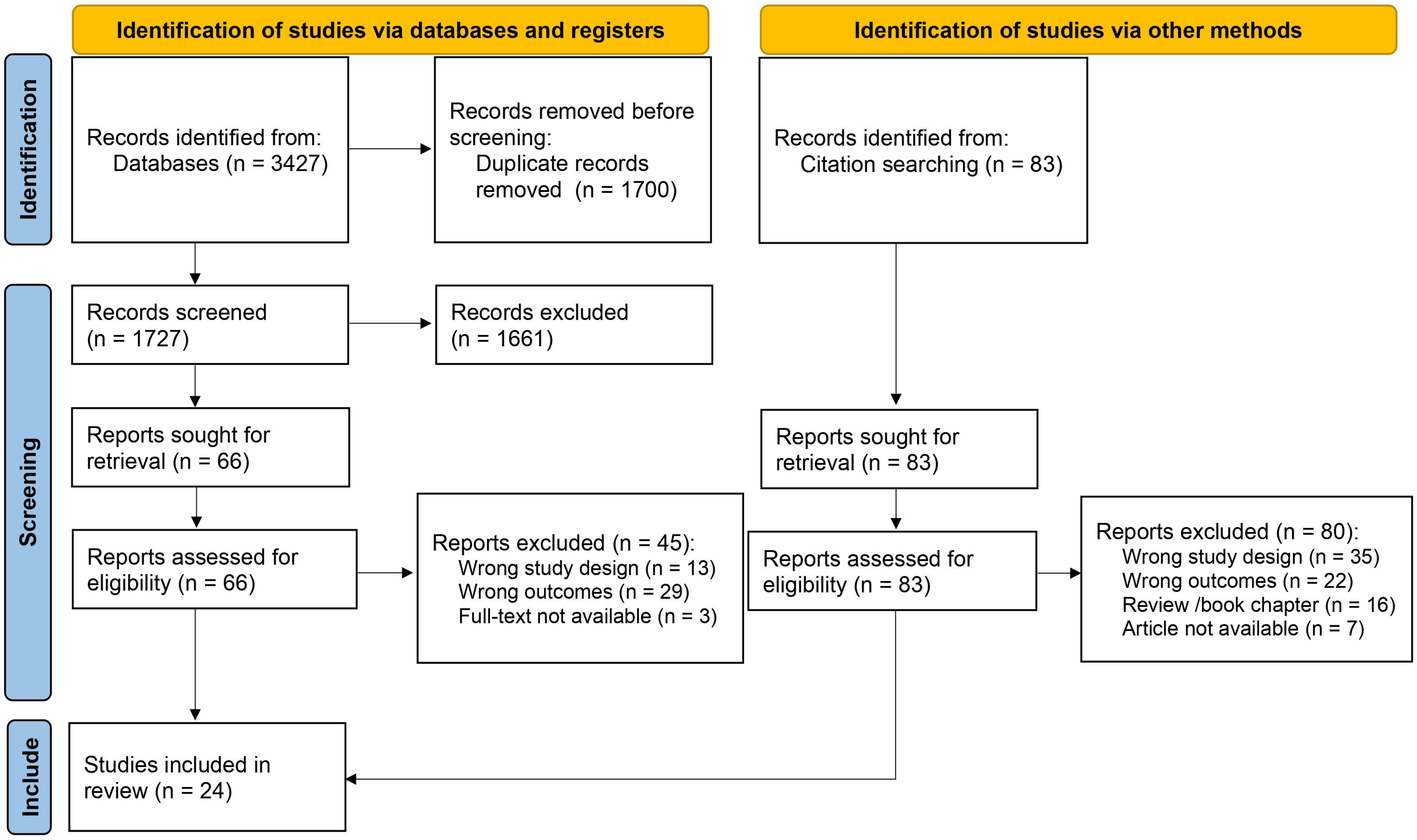

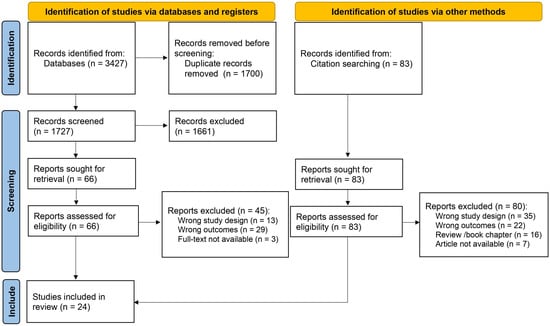

Our initial search identified 3427 reports (Supplementary Material S1). Following duplicate removal (n = 1700), we screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 1727 records, excluding 1661 reports. After a detailed full-text review of the 66 remaining studies, we found 21 that met the final inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Citation searches of these articles and relevant reviews yielded 83 reports, of which three fulfilled the inclusion criteria. In total, 24 articles were extracted. The list of abbreviations used in this review are given at the end of this article.

Figure 1.

Study selection flow diagram.

2.1. Characteristics and Quality of the Selected Studies

The studies included in our review were published between 1976 [55] and 2022 [56] and consisted of one abstract (accompanied by a poster) [57], one letter [39], and 22 peer-reviewed research publications [40,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76]. All studies reported minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs), with six studies [67,68,70,71,74,76] providing data on minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs). Twenty articles presented MICs and/or MBCs against S. aureus or methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) [40,55,56,57,58,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,76], while eleven publications reported these outcomes against MRSA and/or vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) [39,56,57,59,63,66,67,68,72,75]. Four articles detailed MICs and/or MBCs against S. pyogenes [40,55,56,57]. The substances investigated ranged from cannabis extracts and essential oils to isolated, semi-synthetic, or fully synthetic compounds, some of which were procured from vendors or produced via fermentation.

Risk of Bias (RoB) scores for the selected studies primarily fell into categories 1 and 3. Both Ali et al. (2012) [58] and Schuetz et al. (2021) [57] were assigned a score of 3 due to the complete absence of a methodology description for the MIC. Several other studies scored 3 because they failed to report the CBD concentrations tested against the bacteria during the MIC determination [39,60,62,68,69,71,75] or neglected to mention the inclusion of negative control [63,65]. If these essential aspects were reported, these studies would primarily be included under RoB category 1 [39,60,62,63,65,68,69,71,75]. Two studies, Turner and Elsohly (1981) [73] and van Klingeren and Ten (1976) [55], lacked tested concentrations and negative control documentation. If this information was provided, their respective RoB scores would be adjusted to categories 2 [73] and 1 [55], respectively. The omission of test concentrations and negative controls greatly influences the RoB scores, as these are mandatory reporting details according to the Toxicological Data Reliability Assessment Tool (ToxRTool 2009, European Commission’s Joint Research Centre, Ispra, Italy). The absence of these data significantly lowers the reliability score of the study.

The MIC determination in the reviewed studies employed a range of assays, including broth macrodilution, broth microdilution, agar plate dilution, and agar well diffusion assays, with broth microdilution being the most frequently utilised. The researchers either adhered to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), International Standards Organisation (ISO) standards, or to guidelines from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), previously known as the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). However, most researchers did not indicate whether they followed specific guidelines. The studies utilising the broth microdilution method displayed considerable variability regarding their final bacterial inoculum (ranging from 103 to 1.5 × 108 CFU/mL), culture medium (using cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth, Mueller–Hinton broth, Brain Heart Infusion, nutrient broth, or Luria–Bertani broth), incubation time (ranging from 3 to 48 h), type of plate, and choice of solvent for stock solution preparation (with options including methanol, dimethyl sulfoxide, sterile water, ethyl acetate, phosphate-buffered saline with a pH of 7.0, Tween 80, or ethanol). Notably, some studies failed to report these specific details, especially regarding the type of 96-well plate employed. A comprehensive overview of these study characteristics, including study objectives, a detailed examination of cannabinoids, the method employed for MIC and MBC determination, study limitations, and overall study quality, is provided in Supplementary Table S1. It should be noted that information about purity is included only when specified in the original publication.

2.2. The Antistaphylococcal Effects of Cannabinoids

Based on the reviewed literature, CBD was the most frequently studied and potent cannabinoid against S. aureus [40,55,56,57,64,66]. Table 1 summarises the in vitro effects of cannabinoids on S. aureus. The observed MIC for CBD ranged between 0.65 and 32 mg/L against S. aureus [40,55,56,57,64,66].

Table 1.

A summary of the in vitro activity of cannabinoids (MIC and MBC data) against Staphylococcus aureus.

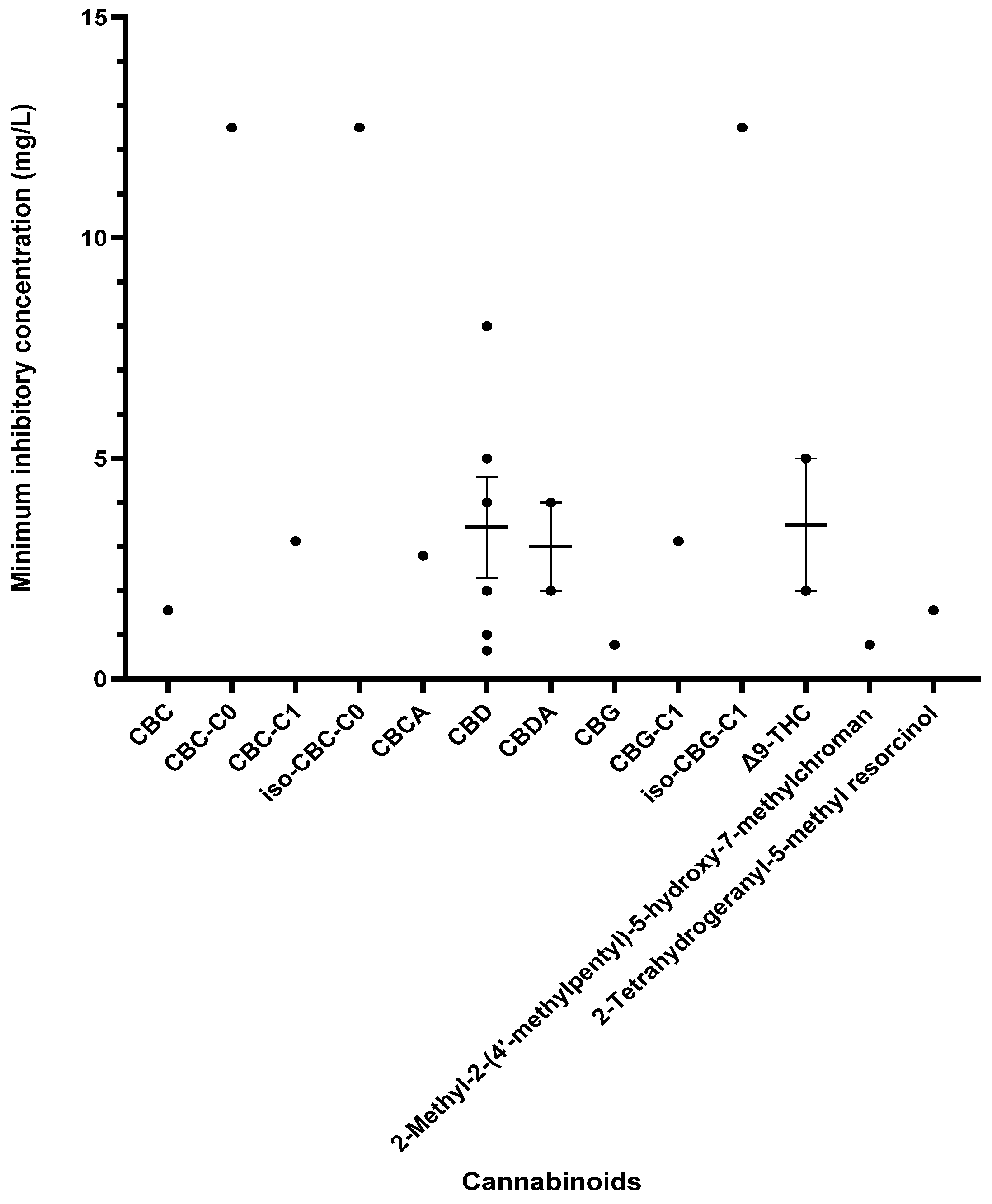

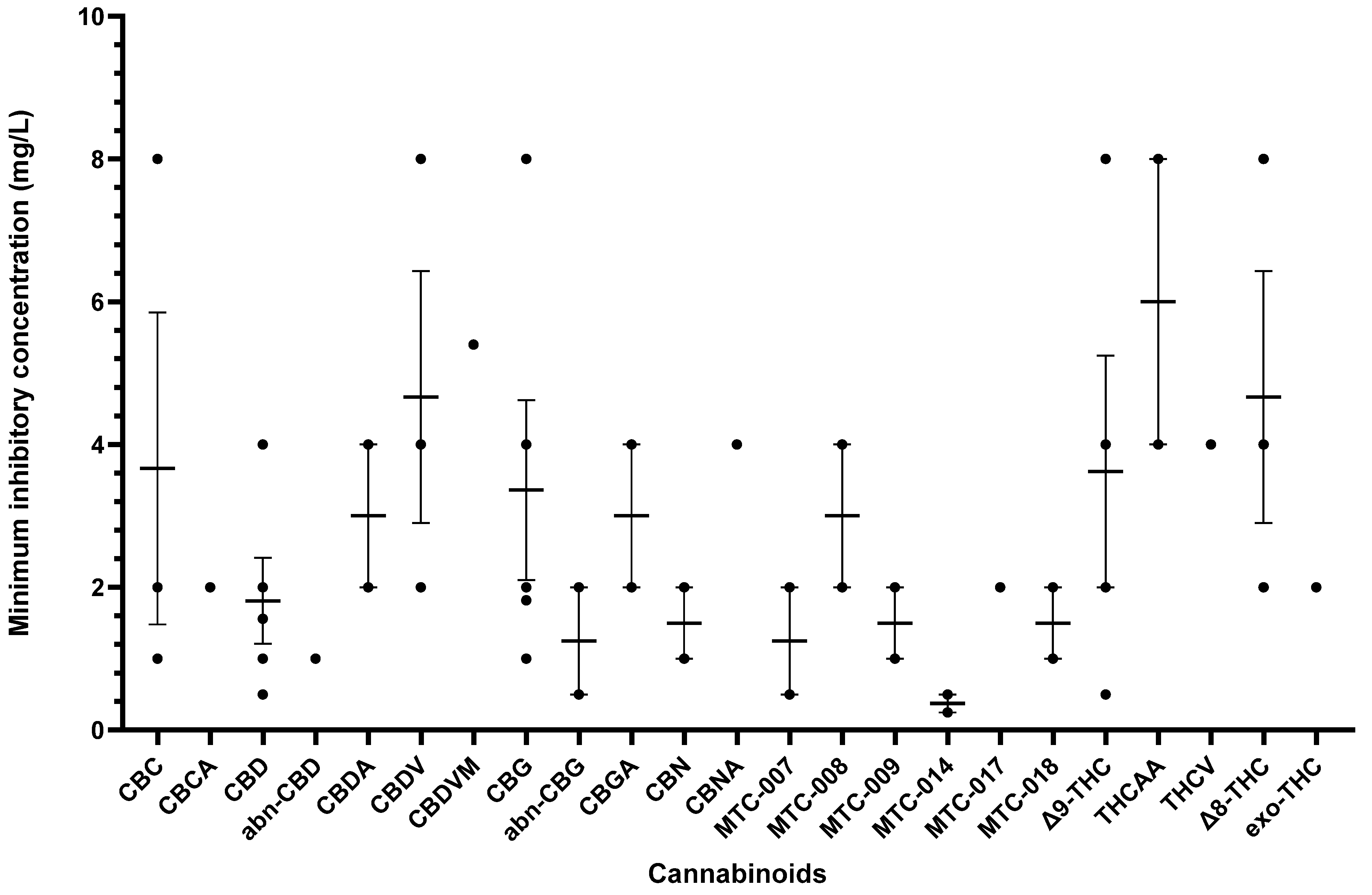

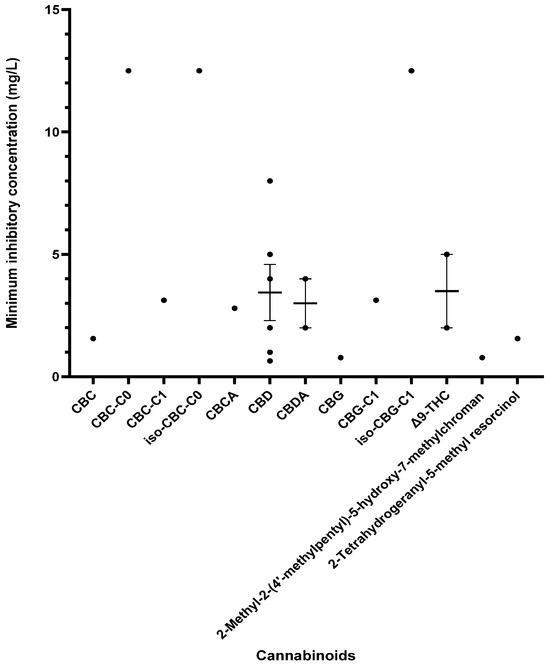

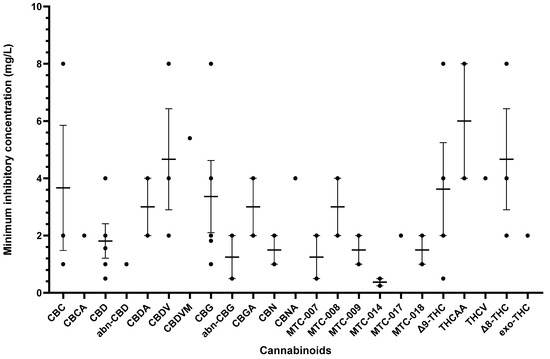

Other cannabinoids showing significant antibacterial activity included CBC, CBC-C0, CBC-C1, iso-CBC-C0, CBCA, CBDA, CBG, CBG-C1, iso-CBG-C1, Δ9-THC, and several other specialised derivatives [55,57,61,63,66,70,73]. The clinical potential of crucial cannabinoids with noteworthy activity (MIC < 16 mg/L) against S. aureus is illustrated in Figure 2. Of these, the majority showed MIC ≤ 4 mg/L (CBC, CBC-C1, CBCA, CBD, CBDA, CBG, CBG-C1, Δ9-THC, and other specialised derivatives), suggesting susceptibility of S. aureus to these agents [79]. The compounds with MICs of 8–16 mg/L show dose-dependent susceptibility, which can be considered when the causative bacteria is resistant to other drugs [79]. It was observed that the derivatives of parent compounds (CBC, CBG) exhibited higher MICs compared to the parent compounds. Table 2 offers an all-inclusive overview of the in vitro antibacterial capabilities of cannabinoids against MRSA and VRSA, along with the specifics of the susceptibility assays employed. The most effective cannabinoids against MRSA comprised CBC, CBCA, CBD, abn-CBD, CBDA, CBG, abn-CBG, CBGA, CBN, CBNA, Δ9-THC, THCV, exo-THC, and some synthetic derivatives as shown in Figure 3 [39,40,56,57,59,63,66,75]. Against VRSA, only CBD was evaluated, and it exhibited good activity with an MIC of 1–2 mg/L [40].

Figure 2.

A comparison of cannabinoids demonstrating in vitro activity against S. aureus (MIC values < 16 mg/L) in a blood-free medium. Cannabidiol (CBD) also reported an MIC of 32 mg/L [64]. The mean and standard error of the mean (excluding outliers) are shown for compounds with multiple MIC values. Abbreviations used in this Figure are listed at the end of this article.

Figure 3.

A comparison of cannabinoids with in vitro MIC values (<16 mg/L) against MRSA. Compounds such as CBDA, CBNA, and THCV with MIC values ≥ 16 mg/L were excluded from the graph. Mean MIC and standard error are shown for compounds with multiple values. Abbreviations are listed at the end of the article.

A few studies have provided data on the MBC for cannabis extracts or cannabinoids against S. aureus [67,68,71,74,76]. Notably, the MBC values were either equivalent to or slightly higher (by one dilution in two-fold dilution increment) than the corresponding MICs against S. aureus [67,68,71,76]. However, only a pair of studies reported MBC values for cannabis extracts in relation to MRSA [67,68], while one study [70] reported MBC for cannabinoids against S. aureus.

Table 2.

A summary of the in vitro activity of cannabinoids (MIC and MBC data) against MRSA and VRSA.

Table 2.

A summary of the in vitro activity of cannabinoids (MIC and MBC data) against MRSA and VRSA.

| Reference | Compound/Extract/EO | Bacteria (Type/Source) | Antimicrobial Outcome (MIC, MBC) | Reference Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscara et al., 2021 [68] | 0.1% acetic acid/hexane extract of dried flowering tops of C. sativa Chinese accession (G-309) as such and after hydrodistillation of the essential oil | MRSA (n = 19) (clinical isolates) | MBC (mg/L) = 39.06–78.13 (both extracts) | MBC (mg/L) VAN = 0.31–0.62 |

| Sarmadyan et al., 2014 [72] | Hydro-alcoholic extract of C. sativa | MRSA | MIC (mg/L) = 50 | |

| Muscara et al., 2021 [67] | 0.1% acetic acid/hexane extract of dried flowering tops C. sativa L. var. fibrante as such and after hydrodistillation of the essential oil | MRSA (n = 19) (clinical isolates) | MBC (mg/L) = 4.88–78.13 | MBC (mg/L) VAN = 0.32–0.64 |

| Abichabki et al., 2022 [56] | CBD | MRSA (ATCC 43300, N315, ATCC 700698 [Mu3], ATCC 700699 [Mu50]) | MIC (mg/L) = 4 | PMB (MIC not given) |

| Wassmann et al., 2020 [75] | CBD | MRSA (USA300 FPR3757) | MIC (mg/L) = 4 | - |

| Schuetz et al., 2021 [57] | CBD, CBG | MRSA (ATCC 33591) | MIC (mg/L) CBD = 1.56 CBG = 1.82 | MIC (mg/L) DOX = 20.83 |

| Blaskovich et al., 2021 [40] | CBD, CBDA, CBDV, 7-hydroxycannabidiol, MTC-002, MTC-005, MTC-007, MTC-008, MTC-009, MTC-011, MTC-012, MTC-013, MTC-014, MTC-017, MTC-018, 7-nor-7-carboxycannabidiol, 7-nor-7-hydroxymethyl-cannabidivarin, 7-nor-7-carboxy-cannabidivarin, Δ9-THC [80,81], THCV, THCVA, THCA-A, Δ8-THC, CBG, CBGA, CBNA | Aerobic assay MRSA (n ≥ 4) (ATCC 43300, ATCC 700699:NRS-1, ATCC 33591, clinical isolates) VRSA (n ≥ 4) (VRS1) Anaerobic assay MRSA (n ≥ 4) (ATCC 43300) | Aerobic assay MIC (mg/L) against MRSA (ATCC 43300) CBD = 1–2 CBDA = 16–32 CBDV = 2–4 7-hydroxycannabidiol = 16 MTC-002 = 16 MTC-005 = 16 MTC-007 = 0.5–2 MTC-008 = 2–4 MTC-009 = 1–2 MTC-011 ≥ 64 MTC-012 > 64 MTC-013 > 64 MTC-014 = 0.25–0.5 MTC-017 = 2 MTC-018 = 1–2 7-nor-7-carboxycannabidiol ≥ 64 7-nor-7-hydroxymethyl-cannabidivarin = 64 7-nor-7-carboxy-cannabidivarin >64 Δ9-THC = 4–8 THCV = 64 THCVA = 32–64 THCA-A = 8 Δ8-THC = 4–8 CBG = 4–8 CBGA = 2–4 CBNA = 4–16 MIC (mg/L) against MRSA (NRS1) CBD = 1–4 MIC (mg/L) against VRSA CBD = 1–2 Anaerobic assay MIC (mg/L) against MRSA CBD = 1–2 | Aerobic assay MIC (mg/L) against MRSA VAN = 0.5–4 DAP = 0.5–8 TMP = 2–4 Mupirocin = 0.125–0.5 CLI ≥ 64 MIC (mg/L) against VRSA VAN > 64 DAP = 1–4 TMP >64 Mupirocin = 32–64 CLI >64 Anaerobic assay MIC (mg/L) against MRSA VAN = 05–1 ERY > 32 TET = 0.06–0.25 Mupirocin = 0.03–0.06 CLI > 32 |

| Farha et al., 2020 [39] | CBC, CBCA, CBD, CBDA, CBDV, CBDVA, CBG, CBGA, CBL, CBN, (−)Δ8-THC, (−)Δ9-THC, exo-THC, THCAA, THCV, THCVA, (±)11-nor-9-carboxy- Δ9-THC, (±)11-hydroxy- Δ9-THC | MRSA (n = 1) (USA300) | MIC (mg/L) CBC = 8 CBCA = 2 CBD = 2 CBDA = 16 CBDV = 8 CBDVA = 32 CBG = 2 CBGA = 4 CBL > 32 CBN = 2 Δ9-THC = 2 Δ8-THC = 2 exo-THC = 2 THCAA = 4 THCV = 4 THCVA = 16 (±)11-nor-9-carboxy- Δ9-THC > 32 (±)11-hydroxy Δ9-THC > 32 | |

| Appendino et al., 2008 [59] | Δ9-THC, 3′-bis-prenyl CBD, abn-CBD, carmagerol, CBC, CBD, CBD-di-Ac [82], CBDA [83], CBDM [84], CBD dimethyl ether [84], CBDA methyl ester [85], CBG, CBGA [86], CBGA methyl ester, CBG-di-Ac, CBG monomethyl ether, CBG dimethyl ether, CBN, phenethyl ester of CBDA, phenethyl ester of CBGA, THCAA [39] | MRSA (n = 6) (SA-1199B, RN-4220, XU212, ATCC25923, EMRSA-15, EMRSA-16) | MIC (mg/L) CBDA = 2 CBD = 0.5–1 CBC = 1–2 CBGA = 2–4 CBG = 1–2 CBGA methyl ester (tested against SA-1199B and XU212): 64 THCAA = 4–8 Δ9-THC = 0.5–2 CBN (tested against SA-1199B, RN-4220, XU212, ATCC25923, EMRSA-15) = 1 abn-CBD = 1 abn-CBG (tested against SA-1199B, RN-4220, XU212, ATCC25923, EMRSA-15) = 0.5–2 carmagerol = 16–32 CBD-di-Ac > 128 CBDM > 128 CBD dimethyl ether > 128 CBDA methyl ester > 128 phenethyl ester of CBDA > 128 CBG-di-Ac > 128 CBG monomethyl ether > 128 CBG dimethyl ether > 128 phenethyl ester of CBGA > 128 3′-bis-prenyl CBD > 128 | Norfloxacin = 0.5–128 ERY = 0.25–>128 TET = 0.125–128 OXA = 0.125–>128 |

| Galletta et al., 2020 [63] | CBCA, CBCM, CBCTFA, CBDVM, CBLM | MRSA (n = 1) (Clinical isolate) | MIC (µM) CBCA = 3.9 (1.4 mg/L) CBCTFA > 250 CBLM > 250 CBCM > 250 CBDVM = 15.6 (5.4 mg/L) | - |

| Martinenghi et al., 2020 [66] | CBD, CBDA | MRSA (n = 1) (USA300) | MIC (mg/L) CBD = 1 CBDA = 4 | MIC (mg/L) CLI = 128 TOB = 1 MEM = 16 OFX = 64 |

The list of abbreviations used in this Table are given at the end of this article. Number of tested bacteria and source are given only when reported in the respective articles.

CBD exhibited concentration-dependent rapid bactericidal activity, with a bactericidal effect observed within 2–3 h at a concentration of 2 mg/L [40,66]. Similarly, cannabidiolic acid (CBDA) showed rapid bactericidal action at a concentration of 40 µM (14.3 mg/L), albeit with bacterial regrowth observed after eight hours [63]. These findings are encapsulated in Table 3 for ease of reference.

Table 3.

Time-kill test results.

2.3. The Synergistic and Additive Effects of Cannabinoids

The synergistic effects of CBD and essential oils of C. sativa with antibacterial agents like bacitracin (BAC) and ciprofloxacin were studied against S. aureus and MRSA [66,69,75]. Pairing of CBD and BAC resulted in synergistic bactericidal action against MRSA (USA300) [75]. In contrast, CBD did not exhibit any synergy when combined with antibiotics like dicloxacillin, daptomycin, nisin, or tetracycline against MRSA USA300 [75], as detailed in Table 4. The synergistic analysis of cannabinoids against S. pyogenes was not explored in the studies examined.

Table 4.

In vitro interactions of cannabinoids in combination with other compounds or other cannabinoids against S. aureus and MRSA.

2.4. Antibiofilm Effects

Compounds such as CBC, CBCA, CBD, CBG, CBGA, THCV, Δ8-THC, and exo-THC showed promise against S. aureus and/or MRSA [39,40,62,76]. Interestingly, these activities were present at concentrations equal to or slightly above the corresponding MIC values, making the clinical usefulness of cannabinoids particularly beneficial [62]. For instance, the MICs of CBC, CBCA, CBD, CBG, CBGA, Δ8-THC, exo-THC, and THCV ranged from 0.5 to 8 mg/L, whereas MBECs of respective compounds ranged from 2 to 8 mg/L. A comprehensive summary of these outcomes is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Antibiofilm effects.

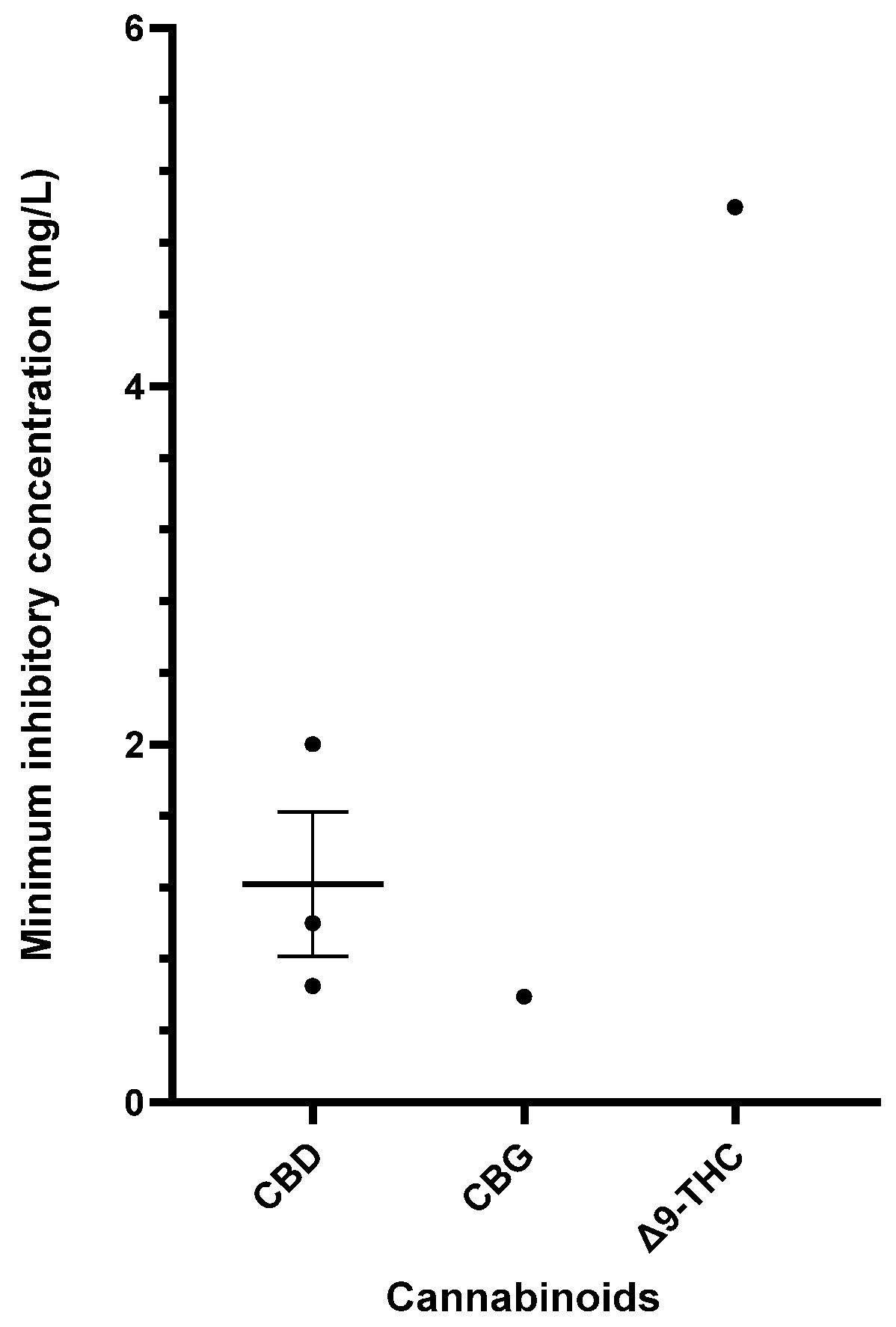

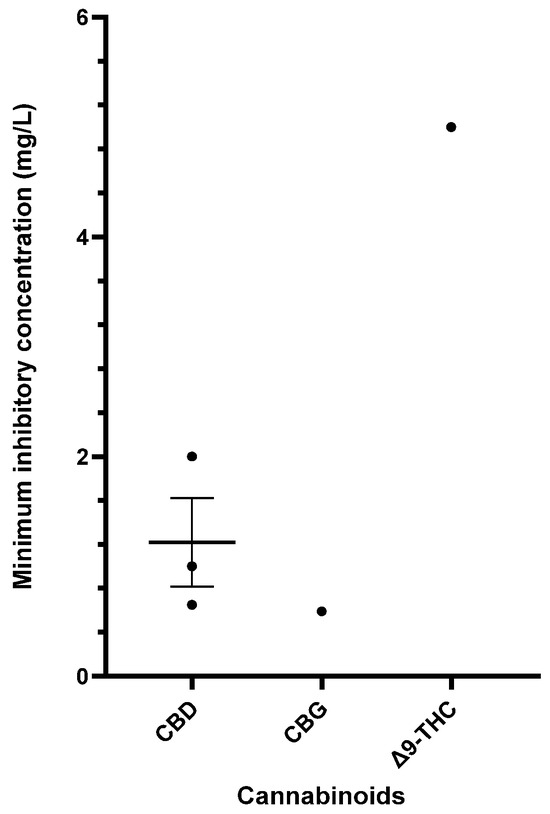

2.5. The Antistreptococcal Effects of Cannabinoids

Table 6 provides a comprehensive summary of the in vitro antibacterial effects of cannabinoids on S. pyogenes, detailing the MICs and MBCs and relevant specifics of the susceptibility assays. Exploration of cannabinoids against S. pyogenes remains limited, but CBD, CBG, and Δ9-THC have demonstrated significant antibacterial results [40,55,56,57]. Figure 4 furnishes a side-by-side comparison of different cannabinoids showing promising MIC data (<16 mg/L) against S. pyogenes.

Table 6.

A summary of the in vitro activity of cannabinoids (MIC and MBC data) against Streptococcus pyogenes.

Figure 4.

Comparison of cannabinoids demonstrating in vitro activity against S. pyogenes (CBD MIC: 32–50 mg/L; THC MIC: 50 mg/L). The mean and standard error are presented for compounds with multiple MIC values, excluding outliers. Abbreviations used in this Figure are provided at the end of the article.

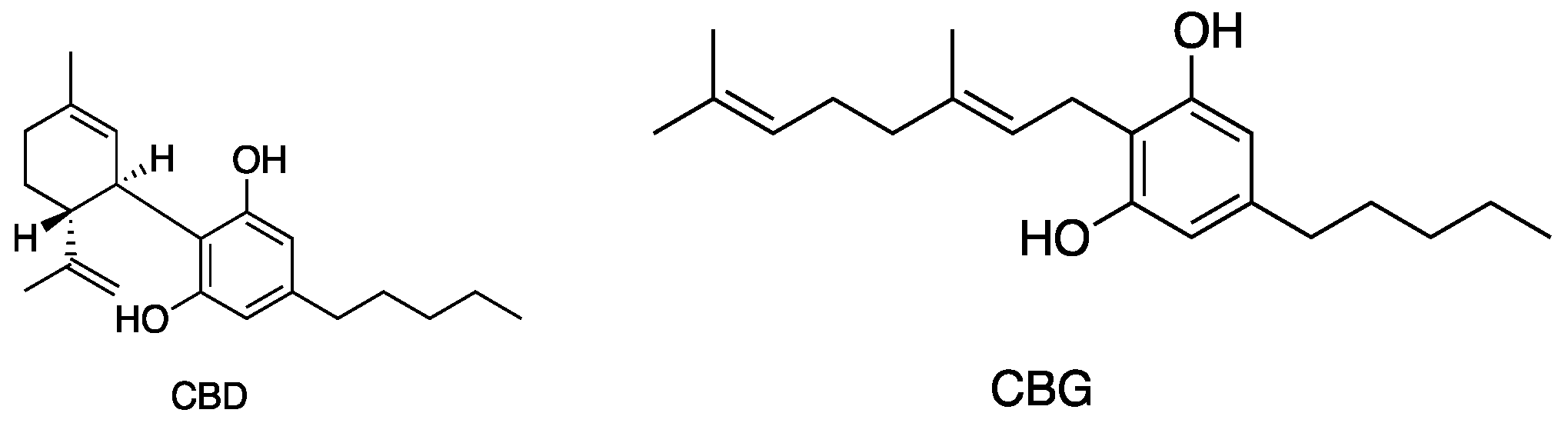

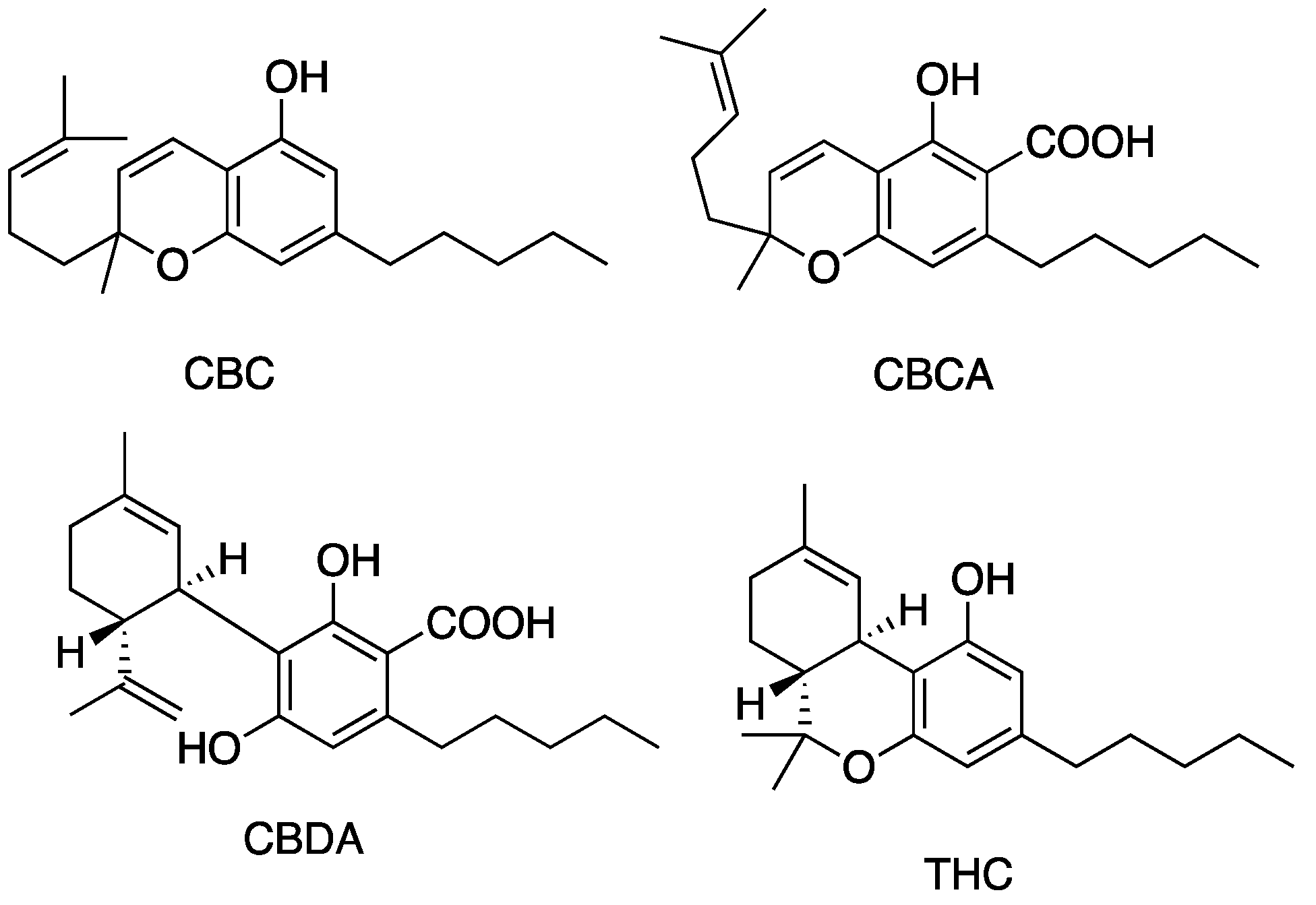

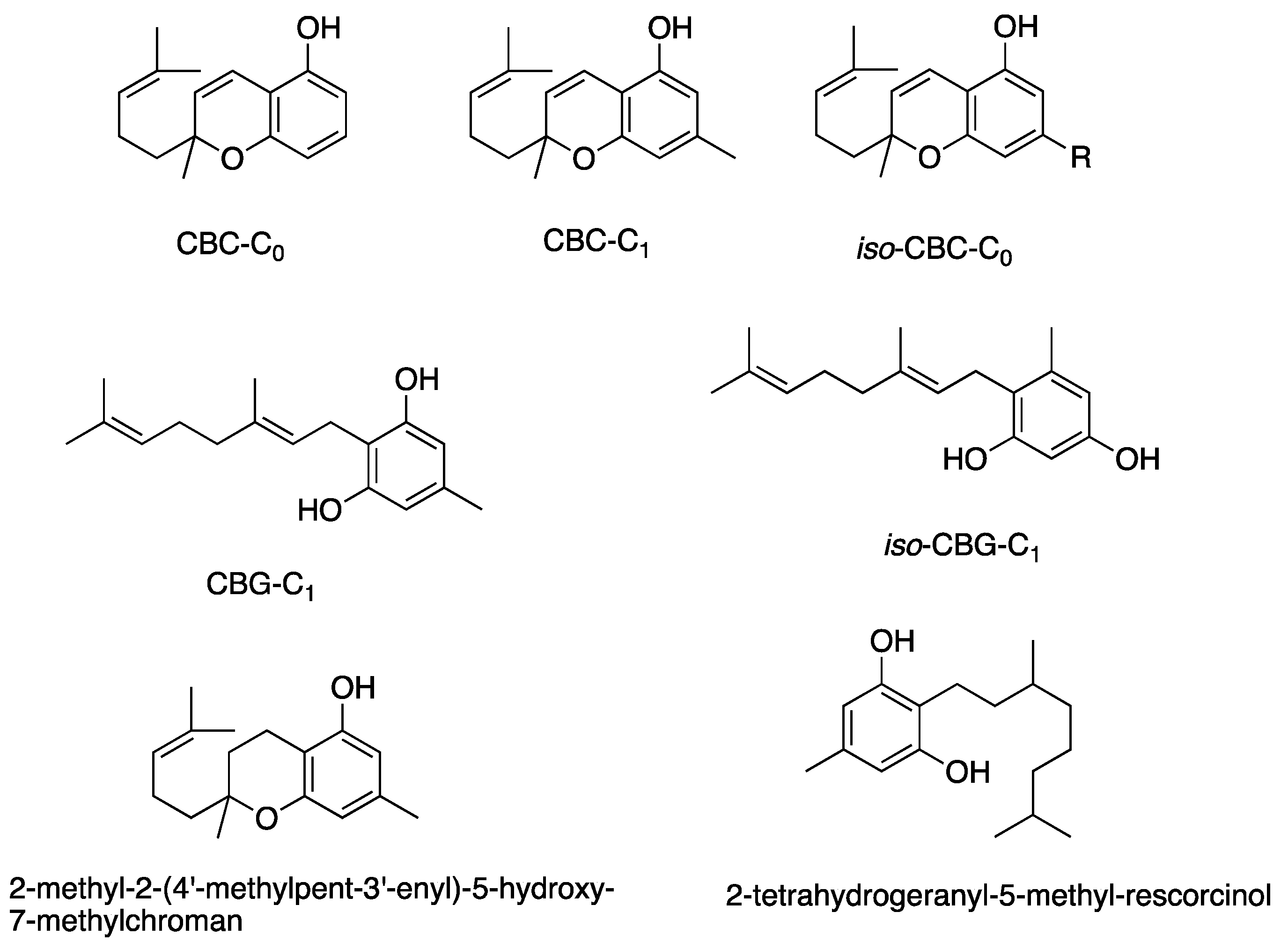

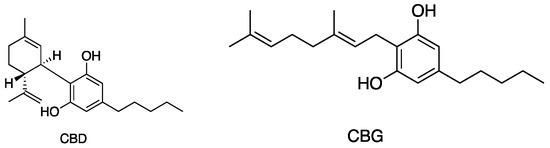

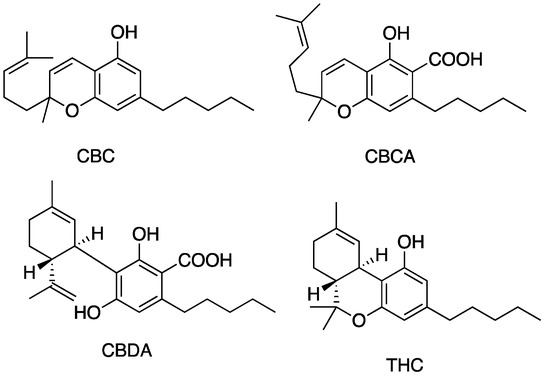

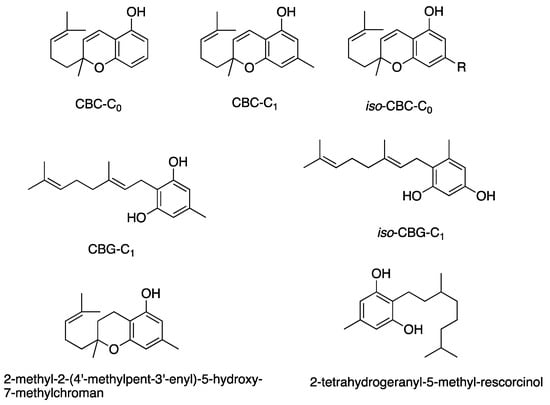

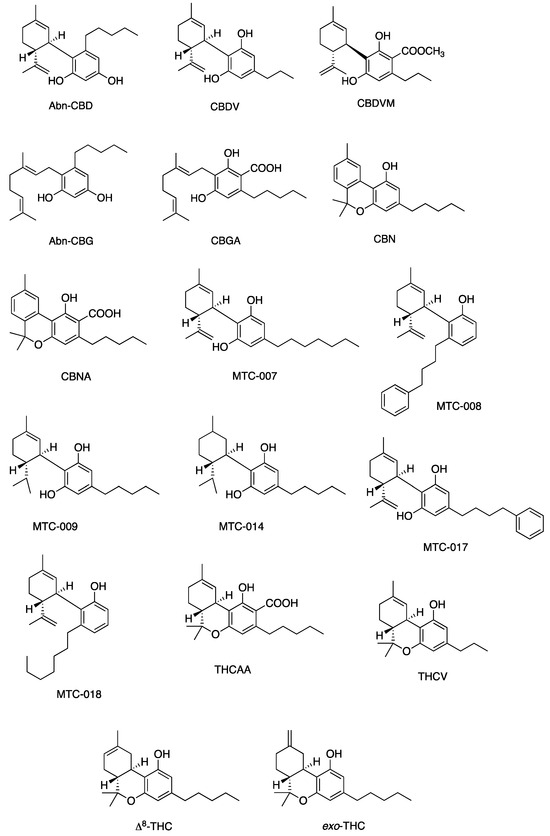

Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8 describe the chemical structures of the cannabinoids most effective against distinct bacterial strains. Figure 5 includes those active against S. aureus, MRSA, and S. pyogenes; Figure 6 shows those active against both S. aureus and MRSA; Figure 7 highlights those effective against S. aureus exclusively; and Figure 8 focuses on those specific to MRSA. All depicted compounds were identified as having MIC values of less than 16 mg/L.

Figure 5.

Structures of cannabinoids active against S. aureus, MRSA, and S. pyogenes; CBD is also active against VRSA. The list of abbreviations used in this Figure are given at the end of this article.

Figure 6.

Structures of cannabinoids active against both S. aureus and MRSA (but not S. pyogenes). The list of abbreviations used in this Figure are given at the end of this article.

Figure 7.

Structures of cannabinoids active against S. aureus. The list of abbreviations used in this Figure are given at the end of this article.

Figure 8.

Structures of cannabinoids active against MRSA only. The list of abbreviations used in this Figure are given at the end of this article.

2.6. Structure–Activity Relationships in Cannabinoids and Antibacterial Implication

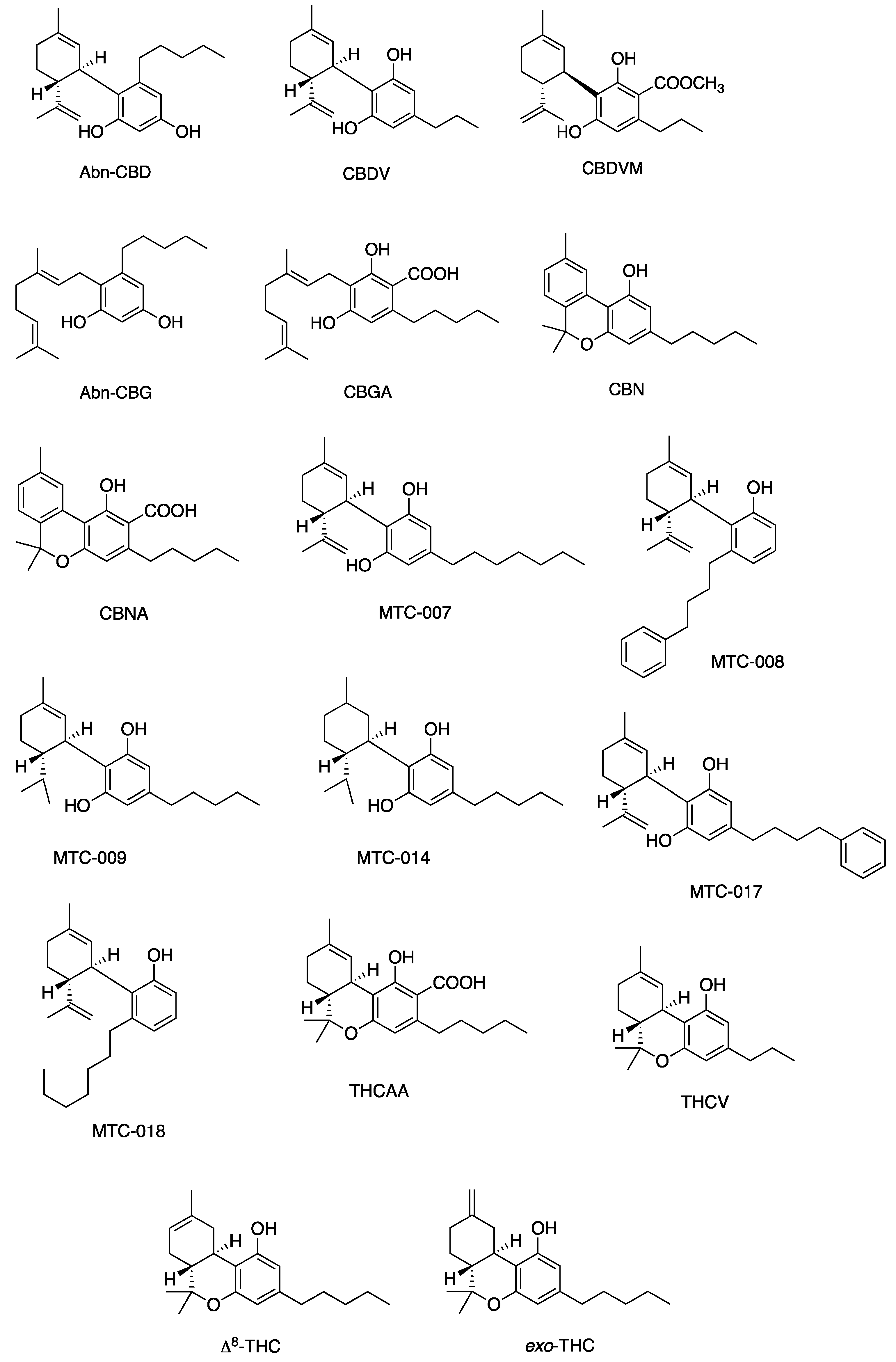

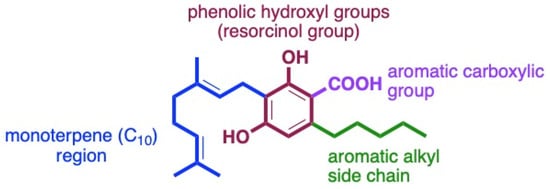

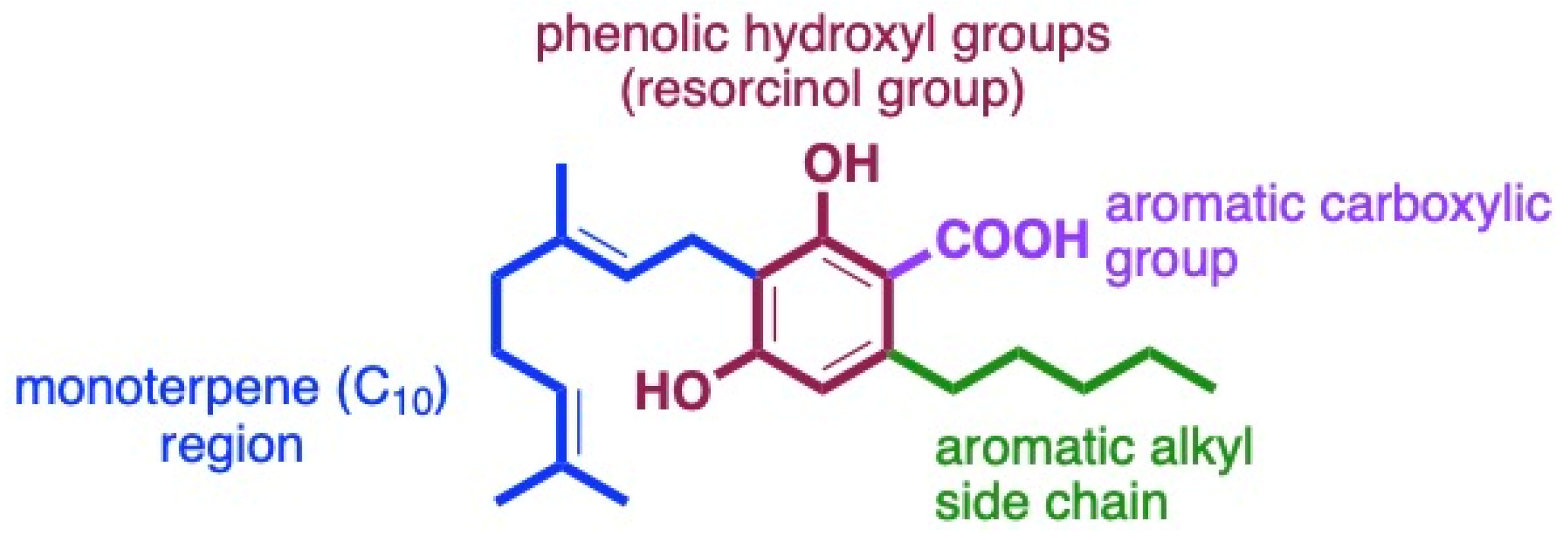

The structural features of cannabinoids can be divided into four main categories (Figure 9), each having specific structure–activity relationships (SARs):

- Monoterpene Region (C10): This region is crucial for synthesising THC-type tricyclic cannabinoids through rearrangements and cyclisation.

- Aromatic Alkyl Side Chain: Usually consisting of a 5xC chain in cannabinoids, called olivetoids, variations include 3xC varinoids (e.g., CBDV, CBDVM), 1xC orcoids (CBC-C1), and resorcinoids without side chains (e.g., CBC-C0).

- Resorcinol Group: Comprised of two phenolic hydroxyl groups, this part can form cannabinoids like Δ9-THC through cyclisation with monoterpenes. These groups may also be subject to O-methylation and O-acetylation reactions.

- Aromatic Carboxylic (COOH) Groups: Found in cannabinoids, these groups are essential in biosynthesis. CBGA, with its aromatic COOH group, is a precursor for other cannabinoids like Δ9-THC, CBD, CBG, and CBN, undergoing decarboxylation, rearrangements, and other modifications [35,59,78,86,88].

Figure 9.

Four main sites for structurally and biologically diverse cannabinoids.

Figure 9.

Four main sites for structurally and biologically diverse cannabinoids.

The study of the SARs of natural cannabinoids is well established [35,59,88]. The summarised antibacterial activity and SAR reveal essential features for antibacterial efficacy, particularly against Gram-positive pathogenic bacteria such as S. aureus, MRSA, and S. pyogenes [35,40].

The monoterpene region within cannabinoids significantly influences both biosynthesis and antibacterial effectiveness. During biosynthesis, a C10-monoterpene moiety is inserted at the 2-resorcinol position through the action of the enzyme aromatic prenyltransferase. This prenyl group can exist in several forms, including an acyclic structure in CBG and CBGA. Compared to its cyclic counterpart, the acyclic form reduces antibacterial activity by 2- to 4-fold. In CBD, a cyclohexene structure increases potency, but extending the ring, as in Δ9-THC, halves the activity against S. aureus. As in CBN, incorporating an extra aromatic ring does not alter antibacterial function. Conversely, transforming alkenes into alkanes (seen in MTC-014) enhances activity 2- to 4-fold relative to CBD. Any hydroxylation or oxidation that diminishes the lipophilicity of the prenyl group, such as in the tail of CBG or the cyclohexene ring, negates this activity, making it less effective than CBD. Therefore, maintaining the lipophilic nature of the prenyl group is vital for effective antibacterial function. The variations within the monoterpene region are pivotal, leading to nuanced differences in the efficacy of cannabinoids against bacterial strains [35,39,40,55,59,66,73,80,86].

The aromatic alkyl side chain, originating from hexanoyl-CoA, plays a crucial role in the antibacterial properties of cannabinoids, as introduced during the early stages of biosynthesis. The position of this chain—specifically at the third position (meta) to the phenolic hydroxyl group—appears vital for antibacterial activity. Its length, ranging from C-0 to C-7, produces distinct activity profiles. For example, lengthening CBD’s aromatic alkyl chain from C-5 to C-7, as in the compound MTC-007, results in similar or doubled antibacterial effectiveness. In contrast, a reduction to C-3, as in CBDV, causes a 2-fold decrease in activity. The Turner group’s study on cannabichromene (CBC) derivatives revealed a similar trend. The C-5 chain configuration exhibits the highest potency among CBC types, while deviations from this length lead to progressively reduced activity. Shortening to C-1 (CBC-C1) or C-0 (CBC-C0) reduces antimicrobial strength by 8- and 16-fold, respectively. Conversely, extending the chain up to C15, as seen in 2-methyl-2-(4′-methylpent-3′-enyl)-5-hydroxy-7-pentadec-8″-enylchromene, substantially diminishes the activity. Overall, these findings highlight the sensitivity of cannabinoids’ antibacterial performance to the aromatic alkyl side chain length [35,39,40,55,59,66,73,80,86].

The presence of an aromatic carboxylic acid group, along with two phenolic hydroxyl groups in cannabinoids, results from the polyketide pathway. The initial stages of this pathway involve the enzymatic fusion of malonyl-CoA with hexanoyl-CoA, leading to a series of reactions that create CBGA. This compound serves as a precursor for various cannabinoids. Removing the COOH group is a non-enzymatic process that can occur spontaneously. Factors such as temperature, light exposure, storage conditions, and specific cofactors can facilitate this removal. Consequently, isolating carboxylate analogues is often challenging. In examining the SAR of cannabinoids, the presence or absence of the aromatic COOH group has a profound impact. Specifically, CBDA, the carboxylated form of CBD, exhibits a 16- to 32-fold reduction in antibacterial activity compared to CBD. This decrease in activity suggests that eliminating the COOH group can increase the antibacterial potency, possibly by making the compound less hydrophilic, thereby affecting membrane permeability. Conversely, when the COOH group is esterified, as in CBG–methyl ester or CBG–ethyl phenyl ester, the antibacterial activity is eradicated (>64 mg/L) in comparison to the parent CBGA molecule (2–4 mg/L). This activity loss may stem from the increased hydrophobicity introduced by these substitutions, which further diminishes the compound’s hydrophilicity [35,39,40,55,59,66,73,80,86,88].

Phenolic Hydroxyl Groups in Cannabinoids: Derived at the onset of biosynthesis, the two phenolic hydroxyl groups are pivotal for preserving the biological functions of cannabinoids. These can be either free (as in CBD) or involved in prenyl group cyclisation (as in Δ9-THC). Regardless of being free or cyclised, these groups enhance activity. However, altering these groups through acetylation or methylation significantly impacts the antibacterial properties. Specifically, in compounds MTC-012 and MTC-013—both derived from CBD—the methylation of one or both hydroxyl groups leads to a loss in antibacterial activity. Likewise, removing one hydroxyl group in MTC-011 decreases efficacy against bacteria such as S. aureus. The significance of the aromatic hydroxyl groups lies in their role in stabilising hydrophilicity, thereby contributing to antibacterial properties. For instance, the interchange of the OH at C1 with the pentyl group at C3 in CBD and CBG leaves the antibacterial activity intact. The crucial requirement is the presence of these groups at specific positions (C1 and C3) on the aromatic ring. It is important to note that the resorcinol molecule lacks antibacterial activity without supporting other structural elements, such as monoterpene and aromatic alkyl groups [35,39,40,55,59,66,73,80,86].

In a broader context, the structural elements contributing to potent antibacterial activity include a decarboxylated aromatic ring with phenolic hydroxyl groups at the 1,3 positions, an aromatic alkyl chain meta to the hydroxyl groups, and a non-polar lipophilic prenyl group.

3. Discussion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this systematic and critical review represents the first comprehensive examination of the antistaphylococcal and antistreptococcal properties of cannabinoids. Various cannabinoids have demonstrated significant antibacterial efficacy against S. aureus, including MRSA. Although studies on the antibiotic capabilities of cannabinoids against VRSA and S. pyogenes are limited, initial results appear encouraging. The alignment of MBCs and MBECs with respective MICs highlights cannabinoids as a noteworthy option amidst the growing concerns over AMR.

With the escalating challenge of AMR, exploring alternative antibacterial agents has become a pressing need [89,90], and C. sativa emerges as a plant source of untapped potential. Cannabinoids are increasingly recognised for their therapeutic roles in pain management, acne vulgaris, dermatitis, pruritus, wound healing, and scleroderma, with recent studies pointing to potential benefits in paediatric dermatology [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,91,92,93,94].

3.1. Safety Profile of Cannabinoids

The safety profile of cannabinoids further underscores their viability. For instance, acute oral administration of cannabis or THC has been found to be non-lethal in dogs and monkeys, with single doses revealing no acute toxicity [95,96]. Low doses of Δ9-THC cause decreased locomotion and sedative and stimulant effects in animals [96]. Escalated CBD doses of up to 62 mg/kg were well tolerated in dogs, showing only minor, placebo-comparable side effects [97]. In rodents, single doses of oral or intraperitoneal cannabinoids (CBD and CBG at 120 mg/kg; 60 mg/kg CBDV and 30 mg/kg Δ9-THC) resulted in piloerection and drowsiness [95]. Chronic CBD administration in humans up to 1500 mg/day was well tolerated [98,99]. Short-term topical and transdermal applications in humans have shown no sensitizing or irritating effects [99,100]. Short-term oral CBD + THC administration (16 days) was well tolerated in human studies, with no notable differences in blood and liver tests and no significant dermatological side effects [101]. Topical 1% CBD cream was tested in a mouse model of autoimmune encephalomyelitis [102]. However, the authors had not reported on the presence or absence of side effects [102]. A case series revealed that topical cannabinoids (THC and/or CBD) caused no side effects in patients with chemotherapy-induced neuropathy, except for one instance where discontinuation led to transient worsening neuropathy [103]. These suggest that cannabinoids exert only minor adverse effects.

3.2. Pre-Clinical Effectiveness

A 5% CBD topical formulation was effective against a mouse model of S. aureus skin infection [40]. Topical CBD, either alone or incorporated in nanoparticles, accelerated the healing of both acute and chronic MRSA-infected wounds in a murine model [104]. Tetrahydrocannabidiol ointment reduced the bacterial load to a minimum level on day 5, comparable with that of mupirocin on dermal MRSA infections on a murine model [105]. However, systemic administration of CBD (100 mg/kg subcutaneously, 200 mg/kg intraperitoneally, or 250 mg/kg orally) was ineffective in an immunocompromised mouse model with MRSA thigh infection [40]. These findings led to phase II clinical trials investigating topical CBD for S. aureus nasal colonization, which is now completed [40,44,106]. The non-lethal nature and favourable safety record of cannabinoids underscore their potential suitability as promising alternatives to antibacterials [95,96,97,98,100,107]. Moreover, a recent systematic review on pre-clinical and clinical effectiveness of cannabinoids in skin wound healing and antibacterial potential summarised the potential of CBD and tetrahydrocannabidiol in reducing bacterial loads in SSTIs [45].

3.3. Efficacy of Cannabinoids Against S. aureus, MRSA and VRSA

MICs of cannabinoids against S. aureus range from 0.78 to 32 mg/L in media without blood, with most values below 4 mg/L. In comparison, existing antibiotics exhibit varying levels of activity against different S. aureus strains, such as fusidic acid (MICs ≤ 0.06 to ≥32 mg/L), mupirocin (0.03 to ≥1024 mg/L), retapamulin (0.03 to 128 mg/L), ozenoxacin (≤0.001 to 2 mg/L), ampicillin (0.125–32 mg/L), cefoxitin (2–64 mg/L), cefuroxime (0.094–512 mg/L), cephalexin (8–16 mg/L), chloramphenicol (0.2–256 mg/L), clindamycin (0.5–250 mg/L), gentamicin (0.016–512 mg/L), oxacillin (0.125–8 mg/L), penicillin (0.016–48 mg/L), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (0.25–8 mg/L), and vancomycin (0.25–12 mg/L) [40,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124]. Against MRSA, cannabinoid MICs range from 0.25 to >128 mg/L, predominantly below 4 mg/L without blood in the media [39,40,56,57,59,63,66,75]. Conventional treatments like cefazolin (MICs: 0.5–≥128 mg/L), cephalexin (0.5–128 mg/L), cephalothin (0.5–512 mg/L), ciprofloxacin (0.125–≥ 16 mg/L), dalbavancin (≤0.03–>0.25 mg/L), daptomycin, fusidic acid (0.12–1024 mg/L), mupirocin (0.125–≥1024 mg/L), linezolid (≤0.25–>8 mg/L), retapamulin (0.06–8 mg/L), ozenoxacin (≤0.001–4 mg/L), trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (≤0.5–≥8 mg/L), vancomycin (≤0.12–64 mg/L), and other antibiotics exhibit a broad range of efficacy [108,110,111,114,115,116,119,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138]. Naturally occurring cannabinoids often show promising activity against MRSA strains, whereas many synthetic derivatives exhibit diminished or no activity with MICs greater than 64 mg/L [40,59]. These comparative data highlight the potential of cannabinoids as alternatives to existing antibacterials with competitive MICs. Moreover, the MBCs of specific cannabis extracts, essential oils, and CBD against S. aureus and MRSA align with their MICs, indicating a bactericidal effect [40,68,74,76]. Interestingly, rapid bactericidal activity within 2–3 h was observed for 2 mg/L CBD and 14.3 mg/L CBCA [40,63,66]. However, regrowth of MRSA was seen after 8 h with CBCA and certain combinations (1.5 mg/L CBD with 20 mg/L bacitracin), possibly due to cannabinoid degradation or oxidation at lower concentrations and the use of a lower concentration of the cannabinoid compared to their MBCs [63,75]. At physiological pH (~7.4), cannabinoids are protonated, preventing oxidative degradation [139,140]. In stability studies at pH 7.4 in aqueous medium at room temperature, CBD remained stable for up to 24 h, whereas the stability of CBN, CBG, and CBGA decreased at 24 h [139]. The thermal instability of CBDA allows for slow decarboxylation [66]. Moreover, CBDA presents more instability than CBD since the carboxylic acid group interacts strongly with methanol and water molecules in the solvent [66]. No regrowth was observed with higher CBD and bacitracin concentrations (2 + 16 mg/L) against MRSA [75]. Moreover, CBDA reduced the MRSA load up to 8 h at higher bacterial loads where vancomycin failed [63]. Only CBD is tested against VRSA. These findings underscore the potential of cannabinoids in S. aureus infections.

3.4. Synergistic and Antibiofilm Properties of Cannabinoids

Cannabinoids enhanced the antibacterial activity of conventional antibiotics against resistant bacteria [69,75]. For instance, CBD combined with bacitracin reduced the MIC against MRSA by 32- to 64-fold [75]. CBD’s synergy with ciprofloxacin against S. aureus further emphasises its potential to act as a synergistic antibacterial agent [69]. Due to CBD’s low oral bioavailability, different formulations, oil-based excipients, routes of administration, and postprandial administration could enhance the clinical utility of these combinations [141,142]. These findings suggest testing CBD with existing antibiotics to prolong their effectiveness through antibiotic adjuvants [143,144,145]. Cannabinoids are also well suited for treating bacterial skin infections and wounds due to their antibacterial, wound-healing, and skin-moisturizing properties [40,104,105,146,147,148,149,150]. Additional therapeutic attributes, such as anti-pruritic and anti-inflammatory effects, may further enhance their success in these applications [42,43].

Although, CBDA exhibited re-growth of exponentially growing MRSA after 8 h, it reduced the MRSA load to undetectable limits at 4 h with no re-growth at 24 h when cell growth was arrested at the same concentration suggesting the ability to eradicate biofilms [63]. Vancomycin was effective against exponentially growing MRSA yet failed against arrested cell growth suggesting the ineffectiveness in biofilms [63]. However, not all studies have yielded positive results. Wassmann et al. (2020) [75] reported no antibiofilm effects with a CBD/bacitracin combination against MRSA, whereas essential oils and C. sativa extracts showed promising antibiofilm activity [62,76]. Cannabinoids’ MBECs align with their respective MICs against MSSA and MRSA, indicating their ability to kill biofilm-forming bacteria at clinically effective concentrations [39,40,151]. This makes cannabinoids able to resolve clinically challenging infections since the formation of bacterial persisters represents a significant obstacle to successful antibiotic treatment and is often implicated in recurrent infections [39,151,152]. Certain cannabinoids, like CBCA, CBGA, CBDV, and CBC, showed concentration-dependent rapid bactericidal effects on MRSA persisters, even in the stationary phase [39,63]. However, other cannabinoids (CBDA, THCVA, CBDVA, (±)11-nor-9-carboxy- Δ9-THC, (±)11-hydroxy-delta-9-THC, CBL) and vancomycin did not exhibit bactericidal activity against MRSA persisters [39]. These findings highlight the substantial potential of cannabinoids in antibacterial treatment, providing avenues for synergistic approaches, biofilm eradication, and effective action against bacterial persisters.

3.5. Potential of Cannabinoids Against S. pyogenes

Few studies have investigated the MICs of cannabinoids against S. pyogenes [40,55,56,57]. The studied cannabinoids—CBD, CBG, and delta-9-trans-THC—showed promising activity [40,55,56,57]. Van Klingeren and Ten (1976) [55] reported lower MICs for THC and CBD in media without blood than those with horse blood. However, the recommended method includes blood in the culturing medium for S. pyogenes [153]. Recent studies have highlighted the efficacy of CBD and CBG against S. pyogenes, with MICs below 1 mg/L, underscoring their therapeutic potential [40,57]. Cannabinoids’ activity against S. pyogenes is comparable to established antibacterials, such as fusidic acid (MICs 1–>16 mg/L), mupirocin (0.06–6.25 mg/L), retapamulin (0.016–0.25 mg/L), ozenoxacin (≤0.004–2 mg/L), amoxicillin (≤0.063–>2 mg/L), benzylpenicillin (0.023–256 mg/L), erythromycin (≤0.063–>256 mg/L), levofloxacin (0.38–1024 mg/L), penicillin (0.004–0.25 mg/L), rifampicin (64–>1024 mg/L), tetracycline (1–≥16 mg/L), trimethoprim (8–>512 mg/L), and others [110,113,114,115,116,119,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163]. However, further research on cannabinoids’ MBC, synergistic interactions, and antibiofilm effects against S. pyogenes is needed.

3.6. Quality of Evidence

A review of existing studies reveals that most were of high quality, with the majority receiving a score of one. However, some studies were rated lower due to missing critical information, such as negative controls or specific concentrations tested. Methodological discrepancies, such as inoculum size variations, affect MIC comparisons across studies [164]. The impact of 96-well plate types on cannabinoid MICs, with polystyrene being most appropriate for CBD and its derivatives is a noteworthy observation [40]. Culture medium also significantly affected CBD MICs; shifting from CAMHB to MH-F altered CBD MICs from 4 to 64 mg/L against S. aureus [56]. In addition, switching from nutrient broth to horse blood agar increased MICs for CBD and THC against S. aureus tenfold [55]. These variations might be due to CBD’s high protein binding (≥88% in patients with hepatic impairment, 93–99% in those with normal hepatic function), impacting testing against S. pyogenes, where blood is required in the culturing medium [165,166]. Adhering to established guidelines (EUCAST or CLSI) would standardise experimental parameters, such as inoculum size, incubation conditions, and culture medium, and improve the understanding the full antibacterial potential of cannabinoids.

The limitations of our review include the qualitative evaluation of the data due to methodological heterogeneity and the small number of studies for a particular cannabinoid.

In summarising the existing research, various cannabinoids—including THC derivatives, CBN-type, CBD-type, CBC-type, and CBG-type—have been demonstrated to have robust antibacterial activity against S. aureus and MRSA. Among these, the non-psychotropic and non-sedative CBN-type, CBD-type, CBC-type, and CBG-type cannabinoids appear particularly promising for further studies [36]. To date, CBD is the only cannabinoid that has been studied against all relevant organisms of interest, including S. pyogenes and VRSA. This body of evidence emphasises the need for comprehensive research to deepen our understanding and realise the full antibacterial potential of cannabinoids.

4. Materials and Methods

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis guidelines (PRISMA) 2020 [167] (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3) and was registered at OSF registries [168].

4.1. Eligibility Criteria

This review incorporated in vitro studies examining the antibacterial effects of extracts from Cannabis sativa, synthetic or isolated cannabinoids, or essential oils from C. sativa against S. aureus, including MRSA and VRSA, and S. pyogenes. Studies merely stating the presence or absence of antibacterial properties were not considered. Studies reporting the MIC—the least concentration of an antibacterial agent that inhibits visible bacterial growth [153]—or the MBC—the smallest concentration required to kill 99.9% of the final bacterial inoculum after 24 h incubation under standard conditions [169,170]—of any form of treatment involving C. sativa extracts and/or cannabinoids, individually or in combination, were eligible for inclusion. These interventions were compared with either an untreated control, standard treatment, or no treatment. Studies were excluded if they failed to report either MIC or MBC against the designated bacteria or if they examined other bacterial species.

We also evaluated studies for antibiofilm activity and the antimicrobial effect of cannabinoids when combined with other agents. The minimum biofilm eradication concentration (MBEC) is the least concentration that fully eradicates bacterial biofilm [76]. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC), calculated from the checkerboard assay for drug combinations, measures the MIC of a drug when combined as a ratio to its standalone MIC [171]. The interaction between two drugs (A and B) in combination is indicated by the FIC index (FICI), which is the sum of their FICs (FICI = FICA + FICB) [172]. FICI interpretations are ≤0.5 for synergism, 0.5–0.75 for partial synergy, 0.76–1.0 for additive effects, 1.0–4.0 for indifference, and >4.0 for antagonism [172].

4.2. Search Strategy

The search was conducted from the inception of each database to 24 August 2022. The search was performed using the electronic medical databases, including Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and Latin America and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS). The comprehensive search strategy is given in Supplementary Material S1. Reference lists of all included studies and existing review articles were examined to identify additional studies. The search had no restrictions concerning the publication date, but non-English studies were not considered for data extraction. The following search query was adapted for each information source: (cannabis OR cannabinoid*) AND antibacterial*.

4.3. Study Selection

All articles identified during the search were transferred into EndNote 20.4.1 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and then into Covidence systematic review software (2024 Covidence, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia). Two independent reviewers (MA, DN) carried out the study selection, data extraction, and quality assessment. Disagreements at each stage of the study selection and data extraction processes were resolved via consultation with a third reviewer (JT). The search outcome and the inclusion process are comprehensively reported in this systematic review and visualised via a PRISMA-2020 flow diagram [167]. The heterogeneity in the study methodologies precluded a meta-analysis. Rejected articles are listed in Supplementary Material S2.

4.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

The ToxRTool was employed to evaluate the risk of bias of in vitro studies [173]. All studies were included irrespective of their risk of bias. A reliability category 1 implies studies are reliable without restrictions, category 2 implies studies are reliable with restrictions, and category 3 indicates studies are not reliable. In contrast, category 4 suggests the score cannot be assigned.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This review evaluates the in vitro antibacterial activity of medicinal cannabis, focusing on cannabinoids and C. sativa extracts against S. aureus, MRSA, VRSA, and S. pyogenes. Among these, CBD exhibited marked antibacterial effects, with MICs ranging from 0.65 to 32 mg/L for S. aureus, 0.5–4 mg/L for MRSA, 1–2 mg/L for VRSA, and 0.6–50 mg/L for S. pyogenes. MBCs of CBD aligned with MIC against MRSA, suggesting the bactericidal activity at therapeutic concentrations. Cannabinoids, such as CBC, CBCA, CBD, CBG, CBGA, THCV, Δ8-THC and exo-THC, demonstrated promising antibiofilm activity against MRSA, with MBECs closely aligned to their MICs. CBD combined with bacitracin reduced the MIC for MRSA by up to 64-fold. These promising results highlight the potential of cannabinoids in overcoming bacterial resistance mechanisms.

The structure–activity relationship of cannabinoids is central to their antibacterial efficacy. The monoterpene region influences potency, as cyclic forms such as CBD are more effective than acyclic forms like CBGA. The aromatic alkyl side chain length and decarboxylation of the aromatic COOH groups enhance antibacterial properties, highlighting that maintaining the lipophilic prenyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups is essential for activity against Gram-positive bacteria.

Despite these promising results, cannabinoid research remains in its early stages, with only one clinical study on antibacterial effects to date. Further research should explore the additive and synergistic potential of cannabinoids with conventional antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents, optimise their structure–activity relationships, refine cannabinoid formulations, and enhance delivery systems to harness their therapeutic potential in clinical settings fully.

In conclusion, cannabinoids such as CBD, CBG, and Δ9-THC offer significant promise as alternatives or adjuncts to traditional antibiotics, particularly for targeting S. aureus, MRSA, and S. pyogenes. Their favourable safety profile positions them as potential candidates for antibacterial therapies, though rigorous clinical trials, standardised testing, and long-term safety studies are crucial to fully unlock their potential in combating AMR.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/antibiotics13111023/s1, Supplementary material S1: Search strategies; Supplementary material S2: Details of rejected articles; Supplementary Table S1: Descriptive characteristics of the included studies; Supplementary Table S2: PRISMA 2020 checklist; Supplementary Table S3: PRISMA 2020 for abstracts checklist.

Author Contributions

D.N. and J.T. collaboratively conceived the initial idea, which led to the project’s conceptualization. J.T. further provided oversight, supervising and directing the project’s development. A search was conducted by D.N. Screening, data extraction, and risk-of-bias assessment were independently performed by D.N. and M.L.A. The manuscript was written by D.N., M.L.A. and M.Q. D.N., M.L.A., M.Q., J.T., W.T., M.B., F.C., D.T., D.A., M.S. and I.S. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

D.N. was supported by the PhD scholarship from the Accelerating Higher Education Expansion and Development Operation (AHEAD), Sri Lanka (AHEAD/PhD/R3/AH/369).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Indira Samarawickrema is employed by the company Strategy Coaching and Research Consulting Pty Ltd. Author Mahipal Sinnollareddy is employed by the company AbbVie Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

(−)-Δ8-THC, delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol; (±)-CBCA, cannabichromenic acid; (±)-CBCM, cannabichromene methyl ester; (±)-CBCTFA, cannabichromene methyl ester trifluoroacetate; (±)-CBLM, cannabicyclol methyl ester; Δ8-THC, delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol; Δ9-THC, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, (−)-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol; abn-CBD, abnormal-cannabidiol; abn-CBG, abnormal-cannabigerol; AMR, Antimicrobial resistance; ATCC, American type culture collection; BAC, Bacitracin; BHI, Brain Heart Infusion; C. sativa, Cannabis sativa; CAMHB, Cation-Adjusted Mueller–Hinton Broth; CBC, Cannabichromene; CBC-C0, Cannabichromene-C0; CBC-C1, Cannabichromene-C1; CBCA, cannabichromenic acid; CBCM, cannabichromene methyl ester; CBCTFA, cannabichromene methyl ester trifluoroacetate; CBD, Cannabidiol; CBD-di-Ac, cannabidiol-diacetyl; CBDA, Cannabidiolic Acid; CBDM, cannabidiol monomethyl ether; CBDV, Cannabidivarin; CBDVA, cannabidivarinic acid; CBDVM, cannabidivarin methyl ester; CBG, Cannabigerol; CBG-C1, cannabigerol-C1; CBG-di-Ac, cannabigerol-diacetyl; CBGA, cannabigerolic acid; CBL, Cannabicyclol; CBLM, cannabicyclol methyl ester; CBN, Cannabinol; CBNA, cannabinolic acid A; CFU, colony forming units; CHL, Chloramphenicol; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CIP, Ciprofloxacin; CLI, Clindamycin; CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; CO2, carbon dioxide; COVID-19, coronavirus disease; DAP, Daptomycin; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; DOX, Doxycycline; ED, emergency department; EO, essential oil; ERY, Erythromycin; EtOAc, ethyl acetate; EtOH, Ethanol; EUCAST, European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; exo-THC, exo-tetrahydrocannabinol; FIC, fractional inhibitory concentration; FICI, fractional inhibitory concentration index; GEN, Gentamycin; H2, Hydrogen; ICU, intensive care unit; ISO, International Standards Organisation; iso-CBC, Isocannabichromene; iso-CBC-C0, isocannabichromene-C0; iso-CBG-C1, isocannabigerol-C1; LB, Luria–Bertani; LHB, lysed horse blood; LILACS, Latin America and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature; NCCLS, National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; MBC, Minimum Bactericidal Concentration; MBEC, minimum biofilm eradication concentration; MEM, Meropenem; MeOH, Methanol; MET, Methicillin; MH, Mueller–Hinton; MH-F, Cation-Adjusted Mueller–Hinton II Broth (CAMHB) supplemented with defbrinated horse blood and β-NAD; MHA, Mueller–Hinton Agar; MHB, Mueller–Hinton Broth; MIC, Minimum Inhibitory Concentration; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MTC, name given by authors to synthetic cannabinoids; MTCC, microbial type culture collection; n, number, NA, nutrient agar; NB, nutrient broth; NCCLS, national committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; OFX, Ofloxacin; PMB, Polymyxin B; RoB, Risk of Bias; rpm, rounds per minute; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; S. pyogenes, Streptococcus pyogenes; SSTIs, Skin and soft tissue infections; TEC, Teicoplanin; TET, Tetracycline; THCA-A, THCAA, Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid A; THCV, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin; THCVA, tetrahydrocannabivarinic acid; TMP, Trimethoprim; TOB, Tobramycin; ToxRTool, Toxicological data reliability assessment tool; TSA, Tryptone Soy agar; TSB, Tryptone Soy broth; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States; VAN, Vancomycin; VRSA, vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

References

- Janik, E.; Ceremuga, M.; Niemcewicz, M.; Bijak, M. Dangerous Pathogens as a Potential Problem for Public Health. Medicina 2020, 56, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Aguilar, G.R.; Sharara, F.; Mestrovic, T.; Gray, A.P.; Weaver, N.D.; E Wool, E.; Han, C.; Hayoon, A.G.; et al. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022, 400, 2221–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, A.D.; Lo, C.K.; Komorowski, A.S.; Suresh, M.; Guo, K.; Garg, A.; Tandon, P.; Senecal, J.; Del Corpo, O.; Stefanova, I.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1076–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, A.D.; Lo, C.K.; Komorowski, A.S.; Suresh, M.; Guo, K.; Garg, A.; Tandon, P.; Senecal, J.; Del Corpo, O.; Stefanova, I.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia mortality across country income groups: A secondary analysis of a systematic review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 122, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, M.G.; Lacey, J.A.; Tong, S.Y.; Davies, M.R. Global genomic epidemiology of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 86, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, J.W.; Cannon, J.W.; Bennett, J.; Bennett, J.; Baker, M.G.; Baker, M.G.; Carapetis, J.R.; Carapetis, J.R. Time to address the neglected burden of group A Streptococcus. Med. J. Aust. 2021, 215, 94.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.M.; Sterkel, A.K.; McBride, J.A.; Corliss, R.F. The Shock of Strep: Rapid Deaths Due to Group a Streptococcus. Acad. Forensic Pathol. 2018, 8, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, V.; Rotstein, C. Bacterial Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in Adults: A Review of Their Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Treatment and Site of Care. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 19, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.; Price, J.; Llewelyn, M. Staphylococcal and streptococcal infections. Medicine 2017, 45, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.J. Antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Current status and future prospects. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 430–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khademi, F.; Vaez, H.; Sahebkar, A.; Taheri, R.A. Group A Streptococcus Antibiotic Resistance in Iranian Children: A Meta-analysis. Oman Med. J. 2021, 36, e222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meletis, G.; Ketikidis, A.L.S.; Floropoulou, N.; Tychala, A.; Kagkalou, G.; Vasilaki, O.; Mantzana, P.; Skoura, L.; Protonotariou, E. Antimicrobial resistance rates of Streptococcus pyogenes in a Greek tertiary care hospital: 6-year data and literature review. New Microbiol. 2023, 46, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial resistance: A global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flynn, C.E.; Guarner, J. Emerging Antimicrobial Resistance. Mod. Pathol. 2023, 36, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tärnberg, M.; Nilsson, L.E.; Dowzicky, M.J. Antimicrobial activity against a global collection of skin and skin structure pathogens: Results from the Tigecycline Evaluation and Surveillance Trial (T.E.S.T.), 2010–2014. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 49, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.C.; Mahé, A.; Hay, R.J.; Andrews, R.M.; Steer, A.C.; Tong, S.Y.C.; Carapetis, J.R. The Global Epidemiology of Impetigo: A Systematic Review of the Population Prevalence of Impetigo and Pyoderma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, D.L.; Bisno, A.L.; Chambers, H.F.; Dellinger, E.P.; Goldstein, E.J.C.; Gorbach, S.L.; Hirschmann, J.V.; Kaplan, S.L.; Montoya, J.G.; Wade, J.C. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, e10–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartelli, M.; Coccolini, F.; Kluger, Y.; Agastra, E.; Abu-Zidan, F.M.; Abbas, A.E.S.; Ansaloni, L.; Adesunkanmi, A.K.; Augustin, G.; Bala, M.; et al. WSES/GAIS/WSIS/SIS-E/AAST global clinical pathways for patients with skin and soft tissue infections. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2022, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. AURA 2021: Fourth Australian Report on Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Human Health; ACSQHC: Sydney, Australia, 2021.

- Therapeutic Guidelines, Australia. Available online: https://www.tg.org.au/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, C.K.; Eze, C.N.; Dibua, M.E.U.; Emencheta, S.C. A meta-analysis on the prevalence of resistance of Staphylococcus aureus to different antibiotics in Nigeria. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2023, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswihi, S.S.; Udo, E.E. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An update on the epidemiology, treatment options and infection control. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2018, 8, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.-T.; Chen, E.-Z.; Yang, L.; Peng, C.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Chen, D.-Q. Emerging resistance mechanisms for 4 types of common anti-MRSA antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus: A comprehensive review. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 156, 104915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, R.X.; Tong, S.Y. The epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infection in the southern Barkly region of Australia’s Northern Territory in 2017. Pathology 2019, 51, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, R.R.; Holubar, M.; David, M.Z. Antimicrobial Resistance in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus to Newer Antimicrobial Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, B.A.; Al-Johani, I.; Al-Shamrani, J.M.; Alshamrani, H.M.; Al-Otaibi, B.G.; Almazmomi, K.; Yusof, N.Y. Antimicrobial resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, A.; Dadashi, M.; Moghadam, M.T.; van Belkum, A.; Yaslianifard, S.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Global prevalence and distribution of vancomycin resistant, vancomycin intermediate and heterogeneously vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doern, C.D. Group A Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes): The Most Interesting Pathogen in the World. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 2023, 45, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.F.; LaRock, C.N. Antibiotic Treatment, Mechanisms for Failure, and Adjunctive Therapies for Infections by Group A Streptococcus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 760255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, R.R. Antimicrobial Resistance among Beta-Hemolytic Streptococcus in Brazil: An Overview. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Costa, C.; Friães, A.; Ramirez, M.; Melo-Cristino, J. Macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes: Prevalence and treatment strategies. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, A.C.; Tong, S.Y.; Chatfield, M.D.; Carapetis, J.R. The microbiology of impetigo in Indigenous children: Associations between Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, scabies, and nasal carriage. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmud, S.; Hossain, M.S.; Ahmed, A.T.M.F.; Islam, Z.; Sarker, E.; Islam, R. Antimicrobial and Antiviral (SARS-CoV-2) Potential of Cannabinoids and Cannabis sativa: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 7216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karas, J.A.; Wong, L.J.M.; Paulin, O.K.A.; Mazeh, A.C.; Hussein, M.H.; Li, J.; Velkov, T. The Antimicrobial Activity of Cannabinoids. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klahn, P. Cannabinoids-Promising Antimicrobial Drugs or Intoxicants with Benefits? Antibiotics 2020, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.; Nagarkatti, P.S.; Nagarkatti, M. Δ9Tetrahydrocannabinol attenuates Staphylococcal enterotoxin B-induced inflammatory lung injury and prevents mortality in mice by modulation of miR-17-92 cluster and induction of T-regulatory cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 172, 1792–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.L.; Pochay, V.E.; Pereira, W.; Shea, J.W.; Hinds, W.C.; First, M.W.; Sornberger, G.C. Marijuana, Tetrahydrocannabinol, and Pulmonary Antibacterial Defenses. Chest 1980, 77, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, M.A.; El-Halfawy, O.M.; Gale, R.T.; MacNair, C.R.; Carfrae, L.A.; Zhang, X.; Jentsch, N.G.; Magolan, J.; Brown, E.D. Uncovering the Hidden Antibiotic Potential of Cannabis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Elliott, A.G.; Zhang, B.; Ramu, S.; Amado, M.; Lowe, G.J.; Hinton, A.O.; Pham, D.M.T.; Zuegg, J.; et al. The antimicrobial potential of cannabidiol. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarenus, C.; Cox, J. The Discovery of the Endocannabinoid System. In Medical Cannabis Handbook for Healthcare Professionals; Nazarenus, C., Ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, M.; de Quadros De Bortolli, J.; Guimarães, F.S.; Salum, F.G.; Cherubini, K.; de Figueiredo, M.A.Z. Effects of cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, on oral wound healing process in rats: Clinical and histological evaluation. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2275–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangiovanni, E.; Fumagalli, M.; Pacchetti, B.; Piazza, S.; Magnavacca, A.; Khalilpour, S.; Melzi, G.; Martinelli, G.; Dell’Agli, M. Cannabis sativa L. extract and cannabidiol inhibit in vitro mediators of skin inflammation and wound injury. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2083–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACTRN12620000456954. A Randomised, Double-Blind, Vehicle-Controlled Study to Evaluate Safety, Tolerability, and Efficacy of Two Dosage Forms of BTX 1801 Applied Twice Daily for Five Days to the Anterior Nares of Healthy Adults Nasally Colonised with Staphylococcus aureus. 2020. Available online: https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ACTRN12620000456954 (accessed on 28 May 2024).

- Niyangoda, D.; Muayad, M.; Tesfaye, W.; Bushell, M.; Ahmad, D.; Samarawickrema, I.; Sinclair, J.; Kebriti, S.; Maida, V.; Thomas, J. Cannabinoids in Integumentary Wound Care: A Systematic Review of Emerging Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeroushalmi, S.; Nelson, K.; Sparks, A.; Friedman, A. Perceptions and recommendation behaviors of dermatologists for medical cannabis: A pilot survey. Complement. Ther. Med. 2020, 55, 102552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagleston, L.R.M.; Kalani, N.K.; Patel, R.R.; Flaten, H.K.; Dunnick, C.A.; Dellavalle, R.P. Cannabinoids in dermatology: A scoping review. Dermatol. Online J. 2018, 24, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounessa, J.S.; Siegel, J.A.; Dunnick, C.A.; Dellavalle, R.P. The role of cannabinoids in dermatology. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 188–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccarrone, M.; Di Rienzo, M.; Battista, N.; Gasperi, V.; Guerrieri, P.; Rossi, A.; Finazzi-Agrò, A. The Endocannabinoid System in Human Keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 33896–33903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caterina, M.J. TRP Channel Cannabinoid Receptors in Skin Sensation, Homeostasis, and Inflammation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupczyk, P.; Reich, A.; Szepietowski, J.C. Cannabinoid system in the skin—A possible target for future therapies in dermatology. Exp. Dermatol. 2009, 18, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheau, C.; Badarau, I.A.; Mihai, L.-G.; Scheau, A.-E.; Costache, D.O.; Constantin, C.; Calina, D.; Caruntu, C.; Costache, R.S.; Caruntu, A. Cannabinoids in the Pathophysiology of Skin Inflammation. Molecules 2020, 25, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, K.F.; Ádám, D.; Bíró, T.; Oláh, A. Cannabinoid Signaling in the Skin: Therapeutic Potential of the “C(ut)annabinoid” System. Molecules 2019, 24, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigelt, M.A.; Sivamani, R.; Lev-Tov, H. The therapeutic potential of cannabinoids for integumentary wound management. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 30, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Klingeren, B.; Ham, M.T. Antibacterial activity of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 1976, 42, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abichabki, N.; Zacharias, L.V.; Moreira, N.C.; Bellissimo-Rodrigues, F.; Moreira, F.L.; Benzi, J.R.L.; Ogasawara, T.M.C.; Ferreira, J.C.; Ribeiro, C.M.; Pavan, F.R.; et al. Potential cannabidiol (CBD) repurposing as antibacterial and promising therapy of CBD plus polymyxin B (PB) against PB-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuetz, M.; Savile, C.; Webb, C.; Rouzard, K.; Fernandez, J.; Perez, E. 480 Cannabigerol: The mother of cannabinoids demonstrates a broad spectrum of anti-inflammatory and anti-microbial properties important for skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 141, S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.M.M.; Almagboul, A.Z.I.; Khogali, S.M.E.; Gergeir, U.M.A. Antimicrobial Activity of Cannabis sativa L. Chin. Med. 2012, 03, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appendino, G.; Gibbons, S.; Giana, A.; Pagani, A.; Grassi, G.; Stavri, M.; Smith, E.; Rahman, M.M. Antibacterial Cannabinoids from Cannabis sativa: A Structure−Activity Study. J. Nat. Prod. 2008, 71, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, N.; Farooq, U.; Khan, M.A. Efficacy of Medicinal Plants Against Human Pathogens Isolated from Western Himalayas of Himachal Pradesh. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsohly, H.N.; Turner, C.E.; Clark, A.M.; Elsohly, M.A. Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activities of Certain Cannabichromene and Cannabigerol Related Compounds. J. Pharm. Sci. 1982, 71, 1319–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frassinetti, S.; Gabriele, M.; Moccia, E.; Longo, V.; Di Gioia, D. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity of Cannabis sativa L. seeds extract against Staphylococcus aureus and growth effects on probiotic Lactobacillus spp. LWT 2020, 124, 109149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletta, M.; Reekie, T.A.; Nagalingam, G.; Bottomley, A.L.; Harry, E.J.; Kassiou, M.; Triccas, J.A. Rapid Antibacterial Activity of Cannabichromenic Acid against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseppi, R.; Brighenti, V.; Licata, M.; Lambertini, A.; Sabia, C.; Messi, P.; Pellati, F.; Benvenuti, S. Chemical Characterization and Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils from Fibre-Type Cannabis sativa L. (Hemp). Molecules 2019, 24, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Sharma, C.; Chaudhry, S.; Aman, R. Antimicrobial Potential of Three Common Weeds of Kurukshetra: An in vitro Study. Res. J. Microbiol. 2015, 10, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinenghi, L.D.; Jønsson, R.; Lund, T.; Jenssen, H. Isolation, Purification, and Antimicrobial Characterization of Cannabidiolic Acid and Cannabidiol from Cannabis sativa L. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscarà, C.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Mandalari, G.; La Camera, E.; Grassi, G.; Circosta, C. Phytochemical characterization and biological properties of two standardized extracts from a non-psychotropic Cannabis sativa L. cannabidiol (CBD)-chemotype. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 5269–5281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscarà, C.; Smeriglio, A.; Trombetta, D.; Mandalari, G.; La Camera, E.; Occhiuto, C.; Grassi, G.; Circosta, C. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of two standardized extracts from a new Chinese accession of non-psychotropic Cannabis sativa L. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafis, A.; Kasrati, A.; Jamali, C.A.; Mezrioui, N.; Setzer, W.; Abbad, A.; Hassani, L. Antioxidant activity and evidence for synergism of Cannabis sativa (L.) essential oil with antimicrobial standards. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 137, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, E.; Pecoraro, M.T.; Formato, M.; Piccolella, S.; Ragucci, S.; Mallardo, M.; Russo, R.; Di Maro, A.; Daniele, A.; Pacifico, S. Cannabidiolic acid in Hemp Seed Oil Table Spoon and Beyond. Molecules 2022, 27, 2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Palmieri, S.; Ricci, A.; Serio, A.; Paparella, A.; Sterzo, C.L. In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Cannabis sativa L. cv ‘Futura 75’ essential oil. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 35, 6020–6024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmadyan, H.; Solhi, H.; Hajimir, T.; Najarian-Araghi, N.; Ghaznavi-Rad, E. Determination of the antimicrobial effects of hydro-alcoholic extract of Cannabis sativa on multiple drug resistant bacteria isolated from nosocomial infections. Iran. J. Toxicol. 2014, 7, 967–972. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, C.E.; Elsohly, M.A. Biological Activity of Cannabichromene, its Homologs and Isomers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1981, 21, 283S–291S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.T.; Kim, H.; Tran, V.K.; Le Dang, Q.; Nguyen, H.T.; Kim, H.; Kim, I.S.; Choi, G.J.; Kim, J.-C. In vitro antibacterial activity of selected medicinal plants traditionally used in Vietnam against human pathogenic bacteria. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassmann, C.S.; Højrup, P.; Klitgaard, J.K. Cannabidiol is an effective helper compound in combination with bacitracin to kill Gram-positive bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zengin, G.; Menghini, L.; Di Sotto, A.; Mancinelli, R.; Sisto, F.; Carradori, S.; Cesa, S.; Fraschetti, C.; Filippi, A.; Angiolella, L.; et al. Chromatographic Analyses, In Vitro Biological Activities, and Cytotoxicity of Cannabis sativa L. Essential Oil: A Multidisciplinary Study. Molecules 2018, 23, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.L.; Ametovski, A.; Luo, J.L.; Everett-Morgan, D.; McGregor, I.S.; Banister, S.D.; Arnold, J.C. Cannabichromene, Related Phytocannabinoids, and 5-Fluoro-cannabichromene Have Anticonvulsant Properties in a Mouse Model of Dravet Syndrome. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.-N.; Jordan, E.N.; Kayser, O. Synthetic Strategies for Rare Cannabinoids Derived from Cannabis sativa. J. Nat. Prod. 2022, 85, 1555–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020; CLSI Supplement M100. [Google Scholar]

- Hanuš, L.O.; Meyer, S.M.; Muñoz, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Appendino, G. Phytocannabinoids: A unified critical inventory. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2016, 33, 1357–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, R.; Brunk, S.F.; Avery, D.H.; Canter, A. The analgesic properties of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and codeine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1975, 18, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Typek, R.; Holowinski, P.; Dawidowicz, A.L.; Dybowski, M.P.; Rombel, M. Chromatographic analysis of CBD and THC after their acylation with blockade of compound transformation. Talanta 2022, 251, 123777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujváry, I.; Hanuš, L. Human Metabolites of Cannabidiol: A Review on Their Formation, Biological Activity, and Relevance in Therapy. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consroe, P.; Martin, A.; Singh, V. Antiepileptic Potential of Cannabidiol Analogs. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1981, 21, 428S–436S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, R.G.; Rock, E.M.; Guenther, K.; Limebeer, C.L.; A Stevenson, L.; Haj, C.; Smoum, R.; A Parker, L.; Mechoulam, R. Cannabidiolic acid methyl ester, a stable synthetic analogue of cannabidiolic acid, can produce 5-HT1A receptor-mediated suppression of nausea and anxiety in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 175, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, M.N.; Shahbazi, F.; Rondeau-Gagné, S.; Trant, J.F. The biosynthesis of the cannabinoids. J. Cannabis Res. 2021, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faleiro, M.L.; Miguel, M.G. Chapter 6—Use of Essential Oils and Their Components against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria. In Fighting Multidrug Resistance with Herbal Extracts, Essential Oils and Their Components; Rai, M.K., Kon, K.V., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Appendino, G.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O. Cannabinoids: Chemistry and medicine. In Natural Products: Phytochemistry, Botany and Metabolism of Alkaloids, Phenolics and Terpenes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 3415–3435. [Google Scholar]

- Ferri, M.; Ranucci, E.; Romagnoli, P.; Giaccone, V. Antimicrobial resistance: A global emerging threat to public health systems. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 57, 2857–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paphitou, N.I. Antimicrobial resistance: Action to combat the rising microbial challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 42, S25–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, I. The Therapeutic Use of Cannabis sativa (L.) in Arabic Medicine. J. Cannabis Ther. 2001, 1, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.A.; Premoli, M.; Tambaro, S.; Kumar, A.; Maccarinelli, G.; Memo, M.; Mastinu, A. Cannabis sativa: A comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long history. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 227, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, S.R.; Romero-Sandoval, A.; Schatman, M.; Wallace, M.; Fanciullo, G.; McCarberg, B.; Ware, M. Cannabis in Pain Treatment: Clinical and Research Considerations. J. Pain 2016, 17, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Kirkorian, A.Y.; Friedman, A.J. Evaluating provider knowledge, perception, and concerns about cannabinoid use in pediatric dermatology. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2021, 38, 694–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiana, S.; Watanabe, A.; Yamasaki, Y.; Amada, N.; Arthur, M.; Fleming, S.; Woodcock, H.; Dorward, P.; Pigliacampo, B.; Close, S.; et al. Plasma and brain pharmacokinetic profile of cannabidiol (CBD), cannabidivarine (CBDV), Δ9-tetrahydrocannabivarin (THCV) and cannabigerol (CBG) in rats and mice following oral and intraperitoneal administration and CBD action on obsessive–compulsive behaviour. Psychopharmacology 2011, 219, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaulieu, P. Toxic Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Animal Data. Pain Res. Manag. 2005, 10, 23A–26A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, D.; Kulpa, J.; Paulionis, L. Preliminary Investigation of the Safety of Escalating Cannabinoid Doses in Healthy Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, M.M.; Queiroz, R.H.C.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.S. Safety and Side Effects of Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa Constituent. Curr. Drug Saf. 2011, 6, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholfield, C.; Waranuch, N.; Kongkaew, C. Systematic Review on Transdermal/Topical Cannabidiol Trials: A Reconsidered Way Forward. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2023, 8, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghfour, J.; Rietcheck, H.; Szeto, M.D.; Rundle, C.W.; Sivesind, T.E.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Lio, P.; Dunnick, C.A.; Fernandez, J.; Yardley, H. Tolerability profile of topical cannabidiol and palmitoylethanolamide: A compilation of single-centre randomized evaluator-blinded clinical and in vitro studies in normal skin. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 46, 1518–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, I.; Zagona-Prizio, C.; E Sivesind, T.; Adelman, M.; Szeto, M.D.; Wallace, E.; Liu, Y.; Sillau, S.H.; Bainbridge, J.; Klawitter, J.; et al. Oral cannabidiol for seborrheic dermatitis in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized clinical trial (Preprint). JMIR Dermatol. 2023, 7, e49965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacoppo, S.; Galuppo, M.; Pollastro, F.; Grassi, G.; Bramanti, P.; Mazzon, E. A new formulation of cannabidiol in cream shows therapeutic effects in a mouse model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. DARU J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]