Simple Summary

Invasive species are considered a threat to the conservation of different environments. Annotating the numbers and species of these invasive organisms is critical to developing conservation strategies. This research gives background information on the types and possible origins of invasive species from the arthropod and chordate groups in Panama. The results indicated that approximately 141 exotic arthropod and chordate species have been reported as invasive species in Panama. Most of these species are believed to have been introduced via the Panama Canal Zone or accidentally. With the information compiled, this study will serve as preliminary data on the sources of introduction and will provide information for future research and plans to prevent the impact of those species.

Abstract

Invasive species are one of the five main causes of biodiversity loss, along with habitat destruction, overexploitation, pollution, and climate change. Numbers and species of invasive organisms represent one of the first barriers to overcome in ecological conservation programs since they are difficult to control and eradicate. Due to the lack of records of invasive exotic species in Panama, this study was necessary for identifying and registering the documented groups of invasive species of the Chordates and Arthropod groups in Panama. This exhaustive search for invasive species was carried out in different bibliographic databases, electronic portals, and scientific journals which addressed the topic at a global level. The results show that approximately 141 invasive exotic species of the Arthropoda and Chordata phyla have been reported in Panama. Of the 141 species, 50 species belonged to the Arthropoda phylum and 91 species belonged to the Chordate phylum. Panamanian economic activity could facilitate the introduction of alien species into the country. This study provides the first list of invasive exotic chordate and arthropod species reported for the Republic of Panama.

Keywords:

invasive species; introduced species; biodiversity; Central America; tropical forest; pest 1. Introduction

Invasive species are one of the five main causes of biodiversity loss, along with habitat destruction, overexploitation, pollution, and climate change [1,2]. An invasive species is understood to be an exotic species that establishes itself in a natural or semi-natural ecosystem or habitat and is an agent inducing changes that affect native biodiversity [1]. The process of invasion is a progressive phenomenon that does not have to be unidirectional [3]. This means that not all introduced species (exotic) will become naturalized, nor will all naturalized ones become invasive. Additionally, there is not a consistent number of species that goes from one phase to another [3].

The problems associated with invasive species are summarized in three main aspects [2]: (1) big economic losses and ecological impacts caused by many invasive species; (2) the increase in the number of introduced species that become invasive and the problems associated with these species; and (3) the need to include invasive species in any ecological study, keeping in mind that these organisms are able to alter an ecosystem in which they are introduced [2].

Invasive species are one of the first challenges to overcome in ecological conservation programs since they are difficult to control and eradicate, mainly due to their reproductive strategies combined with their dispersal, establishment, and persistence [2]. Invasive alien species can be found in all groups of organisms [4]. Globally, 90% of vertebrate and plant introductions are intentional, and the remaining 10% are accidental [5]. After plants, arthropods and chordates include the largest number of invasive exotic species reported for Latin America and the Caribbean [4]. The animal groups which pertain to the Phylum Arthropoda contain the largest number of species known today [6]. Some species transmit diseases or are vectors of them, and some can affect crops, and many serve as natural indicators and pollinators. In addition, a few of these species play the role of primary, secondary consumers or decomposers [6]. Organisms found in the Chordate phylum have high diversities of ecological niches, with notable terrestrial and aquatic environment adaptations [7]. In terms of ecosystemic level, the introduction of mammals can affect food chain functioning, generating a cascade effect on the composition and abundance of invasive predator, herbivore, and plant species as well as nutrient cycles [7].

Panama has the highest number of known vertebrate animals of any country in Central America or the Caribbean and more bird species than the United States and Canada together [8]. In addition, it has 3.5% of flowering plants and 7.3% of fern and related species in the world [9]. Panama is the twenty-eighth country in the world with the greatest biological diversity [8]. However, in proportion to its size, it ranks tenth [8].

Panama’s location and geography have facilitated the introduction of alien species [9]. Its geographical position, high land elevation, and maritime connectivity, as well as the existence of the Panama Canal, has helped biological invasions in Panama [9]. According to [10], the new locks used in the expansion of the Panama Canal allow the passage of ships that are 366 m longer and 49 m wider, facilitating higher transportation of exotic species through either the ship ballast or attachment to the ship’s hull [9].

According to the IV Panama National Biodiversity Report, an estimate of approximately 324 exotic species have been introduced into Panama, the majority of which are plants. In addition, the introduction of exotic pet species has increased. Among the exotic species used as pets are birds, reptiles, and mammals [9]; however, it is not known how many of these exotic species have become invasive species. Due to the lack of records of invasive exotic species in Panama, this study is necessary to help answer how many invasive species of the group of chordates and arthropods have been registered in Panama.

This study provides the first list of invasive species in the Panamanian territory of two important groups of organisms: arthropods and chordates. This study also serves as preliminary data on the sources of introduction and provides information for future research and plans to prevent the negative impact of those species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Panama is geographically located at 7°12′07″ and 9°38′46″ north latitude and 77°09′24″ and 83°03′07″ west Neotropical Region longitude. Panama has a land area of 75,416.6 km2 and is divided into ten provinces. Panama is in the central part of the American continent, in the most eastern and south part of Central America. It is bordered by the Caribbean Sea in the north, the Pacific Ocean in the south, Colombia in the east, and Costa Rica in the west [8].

The economy of Panama is based on four activities, one of them being the logistics industry, which is fundamentally based on the movement of cargo from all over the world [11]. This movement that takes place through ports, airports, railways, and the Panama Canal is one of the main activities that facilitates the introduction of invasive species [12].

2.2. Study Selection

The study was carried out through an exhaustive information review of the following sources:—Global Invasive Species Database: http://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/species.php?sc=965, accessed on 20 January 2023; Invasive Species Specialist Group IUCN/SSC; Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG); and Invasive Species Compendium (CABI): https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/108530#tolistOfSpecies (accessed on 20 January 2023)—from bibliographic databases such as Web of Science (WOS), Science Direct, Scielo, PubMed, Redalyc, Dimensions, and Google Scholar. Using the Publish or Perish software version 8, the URLs resulting from the searches were downloaded in csv format, which was worked in Excel to filter those records that contained a mixture of words (invasive species, Panama alien species, invasive species in Panama, invasive exotic species in Panama, Panama invasive species). Additionally, a thorough search was carried out in specialized journals on the subject, such as BioInvasions Records (Reabic); Biological Invasions (Springer); Revista Bioinvasiones; Check List—The Journal of Biodiversity Data (PENSOFT); as well as the journals published in Panama that are found on the ABC Platforms (SENACYT), such as National Resources and SIBIUP of the University of Panama.

The search was done using the keywords invasive species, exotic species, invasive species in Panama, invasive exotic species in Central America, invasive species of insects in Panama, invasive species in America, new records + Panamá, pest + Panama, introduced species + Panamá, and “alien species” and filtered by the words Panama, new records + Panama, pest + Panama, and introduced species + Panama.

Due to the limited literature published on the subject for Panama, the country’s specialists from the different groups under study were asked for a list of the species considered invasive in the country. We visited the following organizations and reviewed their bibliographies on the subject: Environment Ministry, the Aquatic Resources Authority of Panama, the Panama Canal Authority, the Herbarium of the Panama University, and the Directorate of Plant Health of the Ministry of Agricultural Development.

Other sources of information used were Fifth National Report of Panama to the Convention on Biological Diversity [13]; Invasives in Mesoamerica and the Caribbean [14]; National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2018–2050 [15], and the Ministerio de Desarrollo Agropecuario database of invasive species 2019.

The information obtained was organized in tables for easier understanding. A database of the species was created (in cases where the information was obtained) with the following variables: report date (year), province, altitude, place of origin. This allowed us to answer the research question and achieve one of the objectives. Also, to make easy the access to information on invasive species of the phyla Arthropoda and Chordate, another two tables were created, one including the taxonomic identification of the groups and the reference according to the article or database that was obtained for the species and the other containing limitations on the distribution of pets under official control in the Panama Republic.

3. Results

Through the collection of information, the results indicated that approximately 141 invasive exotic species of the Arthropoda and Chordata phyla have been reported in Panama. Of the 141 species, 50 species belonged to the Arthropoda phylum and 91 species belong to the Chordate phylum, as indicated in taxonomy Table 1.

Table 1.

A taxonomic list of invasive species recorded for the Panama Republic.

Of the 50 species belonging to the Arthropoda phylum, 37 species belonged to the Insecta class, three to the Arachnida class, nine to the Malacostraca class, and one to the Maxillopoda class. Of the 91 species of the Chordate phylum, 49 belonged to the Actinopterygii class, 20 to the Ascidiacea class, eight species to the Reptilia class, five to the bird class, and four to the Amphibia and Mammalia class.

In the Arthropoda Phylum, 18 species belonged to the Coleoptera order, being the most abundant of the groups in this phylum, followed by Decapoda with nine species; Hymenoptera with six species; Diptera and Hemiptera with five each; Acarida with two species; and one species each in the Thysanoptera, Lepidoptera, Blattodea, Mesostigmata, and Cephalobaenida orders.

In the Chordate phylum, 24 species belonged to the Perciforme order; 11 belonged to the Stolidobranchia order; seven species each belonged to the Squamata and Cypriniformes orders; six species each belonged to the Cyprinodontiformes and Aplousobranchia orders; four to the Anura order; three each to the Passeriformes, Characiformes, and Phlebobranchia orders; two each to the Rodentia, Carnivora, Salmoniformes, and Gobiiformes orders; and one species each to the Columbiformes, Pelecaniformes, Carangiformes, Acanthuriformes, Scorpaeniformes, Elopiformes, Clupeiformes, Syngnathiformes, Siluriformes, and Testudines orders.

The three most abundant families of the Arthropoda phylum were Curculionidae (14 spp.), Formicidae (4 spp.), and Tephritidae (3 spp.). For the Chordata phylum, the three most abundant families were Cichlidae (11 spp.); Styelidae (8 spp.); and Cyprinidae, Poeciliidae, and Centrarchidae (6 spp.).

We labeled one case, Rachycentron canadum (Linnaeus, 1766) [9,13], as “under scrutiny”, as the data located it in the Pacific zone of the Panama Republic, but it has never been seen in other Panamanian aquatic ecosystems.

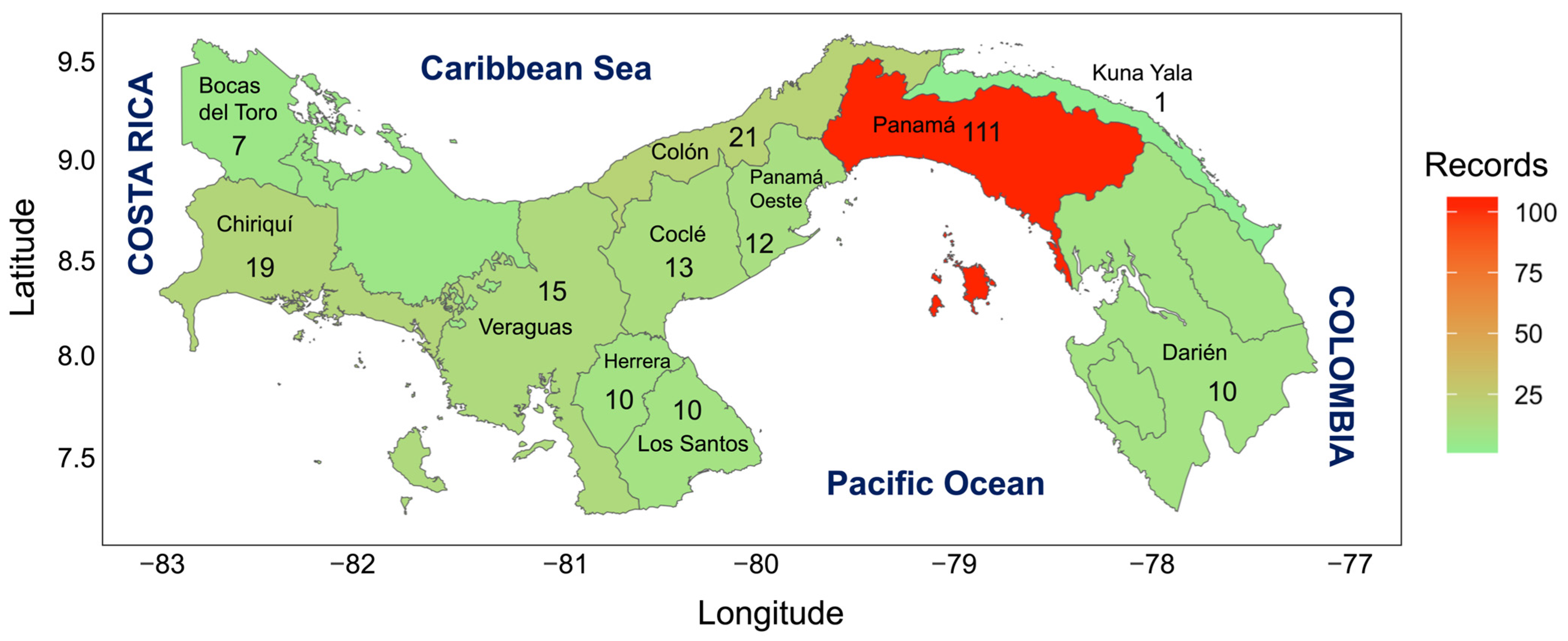

Based on the information obtained, we can say that the province with the highest record of invasive species introduced in the Panama Republic is the Panama province (111 records), followed by Colon (21 records), Chiriqui province (19 records), Veraguas (15 records), Cocle province (13 records), West Panama (12 records), Herrera (10 records), Bocas del Toro (7 records), Los Santos and Darien (10 records), and Kuna Yala (1 record) (Table 2 & Figure 1).

Table 2.

Bionomic data about the invasive species recorded for the Panama Republic.

Figure 1.

Map of the Republic of Panama indicating the number of invasive species by province.

The four continents with the most record of invasive species origins that have been reported in Panama were Asia (22 records), South America (21 records), Africa (15 records), and North America (14 records) (Table 2). The results indicate that the majority of registered invasive species in Panamá are global invasive species (Table 2).

Among the species reported as invasive for the Panama Republic, nine species are under official control, all belonging to the insect class, for causing damage to cucurbit crops, tomato, citrus, coffee, and species of the Arecaceae family (Table 3).

Table 3.

The invasive species recorded for the Panama Republic for the first time (class Insecta).

4. Discussion

Since its emergence and closure, Panama’s Isthmus has been a transit node in global invasion flows. Due to the closure of Panama’s Isthmus, natural events such as the great American biotic exchange [8] have developed, and later during Panamá’s colonial times, due to its geographical position, Panama’s Isthmus was used to transfer merchandise that promoted accidental or intentional species exchange. Later, with the construction of the Panama Canal Railway, the movement of all types of cargo from all over the world increased, making Panama one of the countries with the most species movement globally. Likewise, the presence for almost 100 years of the so-called Panama Canal Zone (area around the Panama Canal under the jurisdiction of the United States) led to the introduction of exotic species to the country without any type of control, many of which became invasive [64].

The results indicate that the main Panamanian ecosystem occupied by invasive exotic species is the aquatic ecosystem, with fish being the most dominant. Most of these species were introduced intentionally and, in many cases, are used as a food source in both farming systems and reservoirs. In terrestrial ecosystems, insects are the largest recorded group of invasive species. The invasive species of this group have become pests in agricultural crops or forest plantations, reducing crop yields and affecting wood commercialization (Table 3). Other species of insects affect ornamental plants, in which case, the damage has been less quantified. In this group, important vectors of human viral diseases (dengue, zika, and chikungunya) are also registered.

In the case of amphibians and reptiles, documentation of the ecological importance of invasive species is scarce. Most records are associated with urban areas, and the extent of their distribution depends greatly on anthropogenic activities [62,63,64,65]. For example, Eleutherodactylus johnstonei uses the vegetation associated with the herbaceous substrate as places to vocalize or perch [66]. Eleutherodactylus planirostris [62] is an introduced frog that has most likely moved to disturbed locations, such as forest edges and outside of residential home gardens, that represent its known habitat [65]. On the other hand, Trachemys scripta elegans is a species introduced for the pet trade [44], and it prefers calm waters with soft and muddy bottoms, aquatic vegetation, and suitable places for sunbathing. Within their native range, red-eared sliders occupy an ecological niche as predators and prey. They are resistant and, outside their native area, they occupy the same ecological niche with great adaptability [67]. A. sagrei, for its part, mainly occupies open areas, is highly territorial, and can ecologically displace native species. It is well adapted to finding food and avoiding predators in newly colonized habitats. Therefore, its capacity to displace other native species may be high [59]. Some species have only been reported, but no studies have been carried out on their current status and ecological impact. Some examples are Rana catesbeiana [44], Sphaerodactylus argus [68], and Eleutherodactylus antillensis [44]. Authors have suggested that some of these invasive amphibians and reptiles can be categorized as pests [44]; however, there is no evidence to support this, so we prefer to categorize them as “Species with potential to displace native species” or “Scarcely documented species”.

In the case of mammals, despite being from only a few species, the effect on public health is immense, as is the case of Mus musculus and Rattus norvegicus. For their part, the two species of the Herpestes genus are aggressive predators that cause imbalances in the local fauna.

According to our results from the Arthropoda and Chordate phyla, there are an estimated 141 invasive species for the Panama Republic. Compared with the information from other Iberoamerican countries, we found that for the countries that are part of the Andean Community (Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru, and Bolivia), 227 invasive exotic species have been identified, mostly plants (92 species), insect pests (61 species), and vertebrates (30 species) [48]. In Costa Rica, 235 invasive species have been reported from all groups of organisms [69]. For the Dominican Republic, 192 species have been reported, of which 38 species were fish, 4 were amphibians, 8 were reptiles, 13 were birds, and 13 were mammals [70]. While in other latitudes, such as the Iberian Peninsula (Spain, Portugal, and Andora), 100 invasive species have been recorded [71].

When comparing the number of invasive species based on the surface area of each country (Andean Community and Dominican Republic) where the study was conducted, we found that the number is higher for the Panama Republic (141 species) compared to the Andean Community (166 species) and Dominican Republic (138 species).

In the Andean Community, the area of Panama is 75,416.6 km2; the area of Colombia is 1142 million km2; the area of Ecuador is 256,370 km2; the area of Venezuela is 916,445 km2; the area of Peru is 1285 million km2; the area of Bolivia is 1099 million km2; and the area of the Dominican Republic is 48,442 km2. This indicates that the Panama Republic, even though it is a small country compared to those previously mentioned, has quite a considerable number of invasive species in the territory.

The economic activity of the Dominican Republic is based on beaches and tourism [72]; Colombia on the free market (exchange of goods and services between people and companies through monetary transactions) [73]; Ecuador and Venezuela on oil revenues [74,75]; Peru on the exploitation, processing, and export of natural resources, mainly mining, agriculture, and fishing [76]; and Bolivia on natural gas [77]. Since the Panama Republic is a country that bases its economy on logistics and transportation, commerce, and finance, we can assume that this is the reason why the constant influx of invasive species is so high compared to the others countries.

The results clearly indicate that the Panama Province is where the greatest number of exotic invasive species have been recorded. This is because the Panama Province is where the largest movement of merchandise operations takes place through the Panama Canal, the Panama Railway, and two of the main seaports.

Invasive exotic species are one of the main threats to countries’ economies and local diversity [1,2]. In Panama, in the case of species that cause economic activity damage, the state permanently monitors the containers of fresh products that enter through different ports and airports of the country [78]. The surveillance programs of the Ministry of Agricultural Development include a list of quarantine species that are monitored for detention in customs facilities. This surveillance is carried out by highly qualified personnel to diagnose species considered of quarantine interest that may affect different crops [78]. Once the invasive exotic species evades the detection line and is introduced into the country, the state develops constant sampling programs in the different provinces to restrict the local distribution of the species (Table 3). An example of this is the Fruit Fly Monitoring Program, which through maximum trapping, has prevented species such as Anastrepha grandis or Ceratitis capitata from spreading throughout the country. The Panamanian state also invests resources in the control and monitoring of exotic species that are vectors of viral diseases such as dengue, zika, and chikungunya. In recent times, these public health programs developed by the Ministry of Health have extended to the border with the Colombian Republic due mainly to the massive migratory phenomenon across the Colombian–Panamanian border in recent years.

In reference to invasive exotic species that affect natural ecosystems, the situation is different. Due to its variety of natural ecosystems, Panama offers an innumerable number of habitats that invasive exotic species can occupy. According to our results, Panama City is the main gateway for invasive exotic species to enter the country. Panama City is surrounded by urban forests with different states of conservation and management, which offers habitats that are highly degraded or contaminated by exotic species. Likewise, the Panama Province and the Colon Province, which is where the Panama Canal is located and which separate the Pacific Ocean from the Caribbean Sea by only 82 km, offer a variety of aquatic habitats for the species that come on ships from different parts of the world. To address this situation and lack of information, the Panamanian state, through the Ministry of the Environment, has established the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2018–2030, which addresses the problem of invasive species in the country [15].

5. Conclusions

The Panama Republic, due to its geographical position and commercial activity, is an important point of global biological invasion. Panamanian aquatic ecosystems are those that have been the most occupied by invasive species. However, invasive species of the insect group quantitatively cause the most damage to humans and the environment.

When comparing the number of invasive species based on the surface area of each country in which this study was conducted, we found that the number was highest for the Panama Republic.

Due to the limitations of this work, it is possible that some species were not included due to a scarcity of information, or that they have not been considered invasive for some researchers because they may correspond to natural distribution patterns, like the case of the coyote.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and D.R.-G.; methodology, E.M. and D.R.-G.; research, E.M., H.A.G.B., R.F., L.R.-S., Y.A., O.G.L.-C. and D.R.-G.; Writing—preparation of original draft, E.M. and D.R.-G.; Writing-revisions and editing, E.M., H.A.G.B., R.F., L.R.-S., Y.A., O.G.L.-C. and D.R.-G.; acquisition of funds, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Panama, the Panamanian National Research System (SNI), and through SENACYT DDCCT economic subsidy contract No. 004-2023.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are included in the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Darío Luque, who provided us with the database of invasive exotic species of MIAMBIENTE; Mgtr. Mirna Samaniego from STRI, who looked for information in the Web of Science; Pedro Méndez, Ricardo Moreno, Jorge García, and Chelina Bastista for assisting with the names of the invasive species for their respective groups; Digna in the MIAMBIENTE documentation section for providing books on invasive species; and the Marine Resources Authority of Panama for offering information on fish introduced in Panama.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Capdevila-Argüelles, L.; Zilletti, B.; Suárez Álvarez, V.Á. Causas de La Pérdida de Biodiversidad: Especies Exóticas Invasoras. Mem. Real Soc. Española Hist. Nat. 2013, 2, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Carballo, G.O. Invasiones Biológicas. In Ecosistemas; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 2009; p. 215. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, J.; Hoopes, M.; Marchetti, M. Invasion Ecology. In Invasion Ecology; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2007; p. 304. [Google Scholar]

- Pauchard, A.; Quiroz, C.; Garcia, R.; Anderson, C.; Arroyo, M. Invasiones Biológicas en América Latina y el Caribe: Tendencias en Investigación para la Conservac. In Conservación Biológica: Perspectivas desde América Latina; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2011; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Waits, L.P.; Paetkau, D. Noninvasive Genetic Sampling Tools for Wildlife Biologists: A Review of Applications and Recommendations for Accurate Data Collection. J. Wildl. Soc. 2005, 69, 1419–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribera, I.; Melic, A.; Torralba, A. Introducción y guía visual de los artrópodos. IDE@. 2015, pp. 1–30. Available online: http://sea-entomologia.org/IDE@/revista_2.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Parques Naturales de la Comunitat Valenciana. PHYLUM CHORDATA. 2023. Available online: https://parquesnaturales.gva.es/es/web/acuarium-virtual-ifac/phylum-chordata (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Autoridad Nacnional del Ambiente (ANAM). Atlas Ambiental de la República de Panamá; Novo Art, S.A., Ed.; Autoridad Nacnional del Ambiente (ANAM): Ancón, Panama, 2012.

- Autoridad Nacional de Ambiente. Informe Sobre Especies Exóticas de Panamá; Autoridad Nacional de Ambiente de Panamá: Ancón, Panama, 2010.

- Muirhead, J.R.; Minton, M.S.; Miller, W.A.; Ruiz, G.M. Projected Effects of the Panama Canal Expansion on Shipping Traffic and Biological Invasions. Divers. Distrib. 2014, 21, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundial, B. Panamá, Panorama General. Available online: https://www.bancomundial.org/es/country/panama/overview (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- European Environment Agency. Pathways of Introduction of Invasive Species, Their Prioritization and Management; Convention on Biological Diversity: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Autoridad Nacional de Ambiente. Quinto Informe Nacional de Biodiversidad de Panamá Ante el Convenio Sobre Diversidad Biológica; Autoridad Nacional de Ambiente: Ancón, Panama, 2014.

- Hernández, G.; Lahmann, E.J.; Pérez-Gil, R. Invasores en Mesoamérica y el Caribe: Resultados del Taller Sobre Especies Invasoras: Ante los Retos de su Presencia en Mesoamérica y el Caribe; IUCN: San José, Costa Rica, 2002; p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Ambiente. Estrategia y Plan de Acción Nacional de Biodiversidad (EPANB) (2018–2050); Ministerio de Ambiente: Panama City, Panama, 2018.

- Pérez, H. Manejo de la Broca del Café en la República de Panamá; Sociedad Mexicana de Entomología, A.C.: Texcoco, Mexico, 2007; pp. 33–36. Available online: https://www.cabi.org/wp-content/uploads/Perez-2006-Coffee-berry-borer.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Salgado Lizardo, C. Especies de Scolytinae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) asociados a puertos y recintos aduaneros en las provincias de Panamá y Colón. Scientia 2022, 32, 64–86. Available online: http://up-rid.up.ac.pa/6129/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Department for Enviroment Food & Rural Affairs. Rapid Pest Risk Analysis for: Xylosandrus crassiusculus. 2015, pp. 1–3. Available online: https://efsa.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.2903/sp.efsa.2020.EN-1903 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- FAO. Declara de Control Oficial la Enfermedad Conocida Como Anillo Rojo de las Palmáceas. 2009. Nº 26.213: Resuelto Nº 71. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/fr/c/LEX-FAOC086829/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Solís, A.; Cambra, R.A.; Gonzales, M. Primer registro para Panamá de la especie invasiva Euoniticellus intermedius. Tecnociencia 2015, 17, 39–43. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/306291580_PRIMER_REGISTRO_PARA_PANAMA_DE_LA_ESPECIE_INVASIVA_Euoniticellus_intermedius_Reiche_1849_COLEOPTERA_SCARABAEIDAE_SCARABAEINAE (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Thomas, H.; Haelewaters, D. A case of silent invasion: Citizen science confirms the presence of Harmonia axyridis (Coleoptera, Coccinellide) in Central America. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrego, J.; Santos-Murgas, A.; Rivera, J.; Vargas, C. Primer Reporte de Eupelmus pulchriceps (Hymenoptera: Eupelmidae) parasitando Callosobruchus phaseoli (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) plaga de Cajanus cajan en Panamá. La Técnica Rev. De Agrocienc. 2022, 12, 1–9. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366055332_Primer_reporte_de_Eupelmus_pulchriceps_HymenopteraEupelmidae_parasitando_Callosobruchus_phaseoli_ColeopteraChrysomelidae_plaga_de_Cajanus_cajan_en_Panama (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Global Invasive Database. Available online: https://www.iucngisd.org/gisd/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Gálvez, D.; Murcia-Moreno, D.; Añino, Y.; Ramos, C. The Asian heminopteran Brachyplatys subaeneus (Westwood, 1837) (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Plataspidae) in Protected are in Panama. BioInvasions Rec. 2022, 11, 95–100. Available online: https://www.reabic.net/journals/bir/2022/1/BIR_2022_Galvez_etal.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Atencio-Valdespino, R. Distribución de Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Liviidae) en zonas de producción citrícola de Panamá. Agron. Mesoam. 2023, 34, 51106. Available online: https://www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?pid=S1659-13212023000200018&script=sci_abstract&tlng=es (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Anovel, C.; Aguilera, V.; Herrera, J.A. Presencia de Pseudacysta perseae (Heidemann, 1908) (Insecta: Hemiptera: Tingidae) en Panamá. IDESIA 2020, 38, 123–127. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-34292020000300123 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Castillo-Gómez, M.; Chang-Pérez, R.; Jiménez-Puello, J.; Santos Murgas, A.; Medianero, E. Knowledge of cycad Aulacaspis scale (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) in Panama. BioInvasion Rec. 2021, 10, 1015–1021. Available online: https://www.reabic.net/journals/bir/2021/4/BIR_2021_Castillo-Gomez_etal.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Emmen, D.; Quiros, D.; Vargas, A. Enemigos naturales de áfidos (Hemiptera: Aphididae) en plantaciones de cítricos de la provincia de Coclé, Panamá. Tecnociencia 2012, 14, 133–148. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328841685_ENEMIGOS_NATURALES_DE_AFIDOS_HEMIPTERA_APHIDIDAE_EN_PLANTACIONES_DE_CITRICOS_DE_LA_PROVINCIA_DE_COCLE_PANAMA (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- José-Ángel, H.V.; Anovel-Amet, B.A. Identificación de Thrips palmi Karny (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) en cultivos de cucurbitáceas en Panamá. Agron. Mesoam. 2013, 24, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, R.F.A.; Härtel, S.; Neumann, P. Global invasions of the western honeybee (Apis mellifera) and the consequences for biodiversity. Écoscience 2005, 12, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medianero, E.; Zachrisson, B. Erythrina gall wasp, Quadrastichus erythrinae (Kim, 2004) (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae: Tetrastichinae): A new pest in Central America. BioInvasions Rec. 2019, 8, 452–456. Available online: https://www.reabic.net/journals/bir/2019/2/BIR_2019_Medianero_Zachrisson.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Murgas, I.; Pitti, C.; Cambra, M.; Cambra, R. First report of the invasive ant Nylanderia fulva (Mayr, 1862) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Panama. BioInvsion Rec. 2022, 12, 78–85. Available online: https://www.reabic.net/journals/Bir/2023/1/BIR_2023_Murgas_etal.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, R. Demografia de Moscas del Género Anastrepha (Diptera: Tephritidae), e Identificación de Poblaciones Ocasionales o Establecidas de Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae), en la Zona Media-Alta de Chicá y el Parque Nacional Campana, Distrito de Chame, Provincia de Panamá. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Panamá, Panama City, Panama, 2004. Available online: http://up-rid.up.ac.pa/4678/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Weems, H.V.; Heppner, J.B.; Steck, G.J. West Indian Fruit Fly Scientific Name: Anasthrepha obliqua (Macquart) (Insecta: Diptera: Tephritidae); DPI Entomology: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2001; EENY-198; Available online: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/IN355 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- FAO. Introduced Species Fact Sheets-2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/introsp/3993/en (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Eskildsen, G.A.; Rovira, J.R.; Smith, O.; Miller, M.J.; Bennett, K.L.; McMillan, W.O.; Loaiza, J. Maternal invasion history of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus into the Isthmus of Panama: Implications for the control of emergent viral disease agents. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iturralde, D. Diversidad y Distribución de Cucarachas (Insecta: Blatodea: Blattaria) en la República de Panamá. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Panamá, Panama City, Panama, 2023. Available online: http://up-rid.up.ac.pa/6357/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Saavedra-Dominguez, F.; Bernal, A.; Childers, C.C.; Kitajima, E.W. First report of Citrus leprosis in Panamá. Pant Dis. 2001, 85, 228. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240595025_First_Report_of_Citrus_leprosis_virus_in_Panama (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Rujano, R.E. Demografía de Ácaros en los Cítricos. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Panamá, Panama City, Panama, 2002; 108p. Available online: http://up–rid.up.ac.pa/4370/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- González, M.; Jiménez, Y.; Marín, J.; Tuñon, Y.; Him, J. Presencia del Dermanyssus gallinae en aves de corral en Las Guabas de Ocú, Panamá. Guacamaya 2018, 3, 25–29. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328615585_Presencia_del_Dermanyssus_gallinae_en_aves_de_corral_en_Las_Guabas_de_Ocu_Herrera_Panama (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Dominique, R.; Mark, T. Established population of the North America Harris mud crab, Rhithropanopeus harrisii (Gould 1841) (Crustacea: Brachyura: Xanthidae) in the Panama Canal. Aquat. Invasions 2007, 2, 155–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kam, Y.; Schloder, C.; Roche, D.; Torchin, M. The Iraqi crab, Elamenopsis kempi in the Panama Canal: Distribution, abundance and interactions with the exotic Noth America crab, Rhithropanopeus harrisii. Aquat. Invasions 2011, 6, 439–445. Available online: http://www.aquaticinvasions.net/2011/AI_2011_6_3_Kam_etal.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Available online: https://serc.si.edu/labs/marine-invasions-research (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Valdés, V.V. Impactos positivos y negativos de la introducción de animales exóticos en Panamá. Tecnol. Marcha 2009, 22, 91–97. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279640630_Impactos_positivos_y_negativos_de_la_introduccion_de_animales_exoticos_en_Panama (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Kelehear, C.; Saltonstall, K.; Torchin, M. An introduced pentastomid parasite (Raillietiella frenata) infects native cane toads (Rhinella marina) in Panama. Parasitology 2015, 142, 675–679. Available online: https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/22662/stri_Kelehear_etal_2014_introduced_pentastomes_in_native_cane_toads.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biota Panamá. Base de Datos de Aves de Panamá-2007. Available online: https://biota.wordpress.com/2007/12/24/base-de-datos-de-aves-de-panama/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Vega, A.; Vergara, Y.; Robles, Y.A. Primer registro de la cobia, Rachycentron canadum Linnaeus (Pisces: RACHYCENTRIDAE) en el Pacífico panameño. Tecnociencia 2016, 18, 13–19. Available online: http://up-rid.up.ac.pa/188/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Gutiérrez Bonilla, F.d.P. Estado de Conocimiento de Especies Invasoras: Propuesta de Lineamientos Para El Control de Los Impactos; Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander Von Humboldt: Bogotá, Colombia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Ferguson, E. Tras la Pista de las especies invasoras. Imagina-SENACYT 2022, 13, 51–53. Available online: https://imagina.senacyt.gob.pa/wp–content/uploads/2021/10/IMAGINA-13-print.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- González-Gutiérrez, R. Los Principales Peces de los Lagos y Embalses Panameños, 7th ed.; Smithsonian Libraries: Panama City, Panama, 2016; pp. 56–114. [Google Scholar]

- Autoridad de los Recursos Acuáticos de Panamá. Available online: https://arap.gob.pa/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- FishBase. List of Freshwater Fishes Reported from Panama. Available online: https://www.fishbase.se/country/CountryChecklist.php?resultPage=2&what=list&trpp=50&c_code=591&cpresence=Reported&sortby=alpha2&ext_CL=on&ext_pic=on&vhabitat=fresh (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Welcomme, R.L. International Introductions of Inland Aquatic Species; FAO Fisheries Technical Paper 294; FAO Fisheries Department: Rome, Italy, 1988; pp. 294–318. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, P.J. Update on geographic spread of invasive lionsfishes (Pterois volitans Linnaeus, 1758 and P. miles Bennett, 1828) in the western North Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico. Aquat. Invasions 2010, 5, S117–S122. Available online: http://www.aquaticinvasions.net/2010/Supplement/AI_2010_5_S1_Schofield.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Díaz, S. Parivivos de la familia Poeciliidae de Panamá Guia de Identificación, 1st ed.; Parque Recreativo Omar: Panamá City, Panama, 2021; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Auth, D.L. Checklist and Bibliography of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Panama; Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 2–98. [Google Scholar]

- Farallo, V.; Swanson, R.; Hood, G.; Troy, J.; Forstner, M. New county records for the Mediterranean house gecko (Hemidactylus turcicus) in Central Texas with comments on human-mediated dispersal. Appl. Herpetol. 2009, 6, 196–198. Available online: https://brill.com/view/journals/ah/6/2/article-p196.xml?ebody=previewpdf-96220 (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Díaz-Pérez, J. Primer registro de Lepidodactylus lugubris (Sauria: Gekkonidae) para el departamento de Sucre, Colombia. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Anim. RECIA 2012, 4, 163–167. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323916731_Primer_registro_de_Lepidodactylus_lugubris_Sauria_Gekkonidae_para_el_departamento_de_Sucre_Colombia (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Batista, A.; Ponce, M.; Garcés, O.; Lassitier, E.; Miranda, M. Silent pirates: Anolis sagrei Duméril & Bibron, 1837 (Squamata, Dactyloidae) taking over Panama City, Panama. Check List 2019, 15, 455–459. Available online: https://checklist.pensoft.net/article/34178/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Ibáñez, D.; Roberto, R. Los Anfibios del Monumento Natural Barro Colorado, Parque Nacional Soberanía y Áreas Adyacentes; Fundación Natura, Círculo Herpetológico de Panamá; Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute: Panama City, Panama, 1999; p. 192. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo, A.C.; Wilson, L.D.; Ibáñez, R.; Jaramillo, F. The herpetofauna of Panama: Distribution and conservation status. In Conservation of Mesoamerican Amphibians and Reptiles; Wilson, L.D., Townsend, J.H., Johnson, J.D., Eds.; Eagle Mountain Publishing: Eagle Mountain, UT, USA, 2010; pp. 604–671. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, A.; Alonso, R.; Jaramillo, C.; Sucre, S.; Ibañez, R. Los códigos de barras de ADN identifican una tercera especie invasora de Eleutherodactylus (Anura: Eleutherodactylidae) en la Ciudad de Panamá, Panamá. Zootaxa 2011, 2890, 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, M.; Bullard, S.; Rocha, R.; Lambert, G. Ascidians at the Pacific and Atlantic entrances to the Panama Canal. Aquat. Invasions 2011, 6, 371–380. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228491724_Ascidians_at_the_Pacific_and_Atlantic_entrances_to_the_Panama_Canal (accessed on 15 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Digna, R.G. Una Aproximación por Metaanálisis al Número de Especies Exóticas Invasoras y sus Áreas Más Frecuentes de Introducción en la República de Panamá. Bachelor’s Thesis, The Panama University, Panama City, Panama, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Antúnez-Fonseca, C.; Juarez-Peña, C.; Sosa-Bartuano, Á.; Alvarado-Larios, R.; Sánchez-Trejo, L.; Vega-Rodriguez, H. First records in El Salvador and new distribution records in Honduras for Eleutherodactylus planirostris Cope, 1862 (Anura, Eleutherodactylidae), with comments on its dispersal and natural history. Caribb. J. Sci. 2021, 51, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.E.; Serrano-Cardozo, V.H.; Pinilla, M.P.R. Diet composition and microhabitat of Eleutherodactylus johnstonei in an introduced population at Bucaramanga City, Colombia. Herpetol. Rev. 2005, 36, 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Burger, J. Red-Eared Slider Turtles (Trachemys scripta elegans); Freshwater Ecology and Conservation Lab, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D.M.; Kluge, A.G. The Sphaerodactylus (Sauria: Gekkonidae) of Middle America; University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad del Atlántico. Especies Invasoras Acuáticas y Salud. In Proceedings of the Memorias II Seminario de La Red Temática InvaWet, Barranquilla, Colombia, 27–28 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. Especies Invasoras en República Dominicana; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2023.

- Casals, F.; Sánchez-González, J. Guía de Las Especies Exóticas e Invasoras de Los Ríos, Lagos y Estuarios de La Península Ibérica; Proyecto LIFE INVASAQUA; Sociedad Ibérica de Ictiología: Navarra, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dominican Republic Economy. Economy 2020. Available online: https://www.republicadominicana.org.br/rp/economia/ (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Cámara de Comercio de Colombia. Available online: https://www.ccb.org.co/blog/colombia-un-pais-de-regiones-e-industrias-que-impulsan-la-economia-nacional (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Instituto de Investigación Económicas y Sociales-Universidad Católica Andrés Bello. Informe de Coyuntura Venezuela; Instituto de Investigación Económicas y Sociales-Universidad Católica Andrés Bello: Caracas, Venezuela, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos. Clasificación Nacional de Actividades Económicas (CIIU Rev. 4.0); Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos: Quito, Ecuador, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Varona-Castillo, L.; Gonzales-Castillo, J.R. Crecimiento Económico y Distribución Del Ingreso En Perú. Problemas Del Desarrollo. Rev. Latinoam. Econ. 2021, 52, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Clasificación de Actividades Económicas de Bolivia; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Janeth, S.; Nicolás, P.H.; Enrique, M. Áfidos (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Aphididae) interceptados en vegetales frescos en los puertos de Manzanillo International Terminal y Panama Ports Company (Colón Panamá). IDESIA (Chile) 2022, 40, 137–143. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).