Abstract

The question of what motivates entrepreneurs to maintain and grow their ventures beyond the startup phase remains an underexplored aspect of entrepreneurship research. Using data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, GEM (2023), this study examines four key entrepreneurial motivations among 103 established Croatian entrepreneurs who are making a difference in the world, building great wealth or a very high income, continuing a family tradition, and earning a living. Employing a multivariate multiple regression approach, we analyze how sociodemographic factors, opportunity perception, fear of failure, media influences, and sustainability-oriented mindsets (e.g., UN SDG awareness) influence these diverse motivations. Findings reveal distinct motivational patterns: socially responsible mindsets and awareness of the SDGs primarily drive the aspiration to “make a difference”, while age, perceived opportunities, and fear of failure reinforce the pursuit of wealth. Media narratives uniquely influence the intent to “continue a family tradition”, while necessity-driven motives—linked to fear of failure and lower growth ambitions—predominate among those aiming simply to “earn a living”. By applying a systems thinking approach, this research illustrates how interdependent factors create distinct motivational clusters, and it highlights the importance of tailored policies and support programs for established entrepreneurs seeking sustainable growth. It contributes to the interdisciplinary discourse on entrepreneurship, offering insights for policymakers, educators, and advisors working to foster resilient and innovative entrepreneurial ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship has long been recognized as a critical driver of economic growth, innovation, and societal advancement [1,2]. While extensive research has explored the motivations behind new venture creation, less is known about how these motivations evolve once businesses become established. This knowledge gap is critical, as understanding long-term entrepreneurial motivation is essential for designing policies and support mechanisms that foster sustained growth, resilience, and responsible business practices [3,4].

Foundational theories have laid the groundwork for understanding entrepreneurship within dynamic and interdependent contexts [5,6]. Entrepreneurial decision-making occurs within dynamic and interdependent systems shaped by socioeconomic conditions, institutional structures, and cultural norms. Rather than viewing entrepreneurial behavior as the outcome of isolated individual traits, this study adopts a systems perspective that emphasizes contextual dependencies, and the co-evolution of personal and environmental factors. While early-stage entrepreneurship is often studied through individual traits or external constraints, established entrepreneurs face dynamic feedback loops, where prior success, market conditions, and personal aspirations continuously reshape their motivations. Recognizing these interdependencies is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of entrepreneurial motivation [7]. Against this backdrop, this study investigates the motivations of established entrepreneurs—defined as those who have continuously paid salaries or financial compensation to owners for more than 42 months. Using data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey for Croatia (2023), we employ a multivariate multiple regression approach to explore four key motivational orientations: (1) making a difference in the world, (2) building great wealth or high income, (3) continuing a family tradition, and (4) earning a living.

Our findings contribute to entrepreneurial motivation scholarship by expanding the focus beyond new venture creation to the long-term strategic and personal goals of established entrepreneurs [8]. We explore the role of media exposure, perceived opportunities, and awareness of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in shaping different motivational pathways. These insights align with a systems-thinking perspective, emphasizing the interconnected nature of entrepreneurial motivations, where considerations about societal impact, financial gain, and risk management form a complex web of influences.

The purpose of this study is to investigate how sociodemographic characteristics, entrepreneurial attitudes, and sustainability-related factors jointly shape the key motivational orientations of established entrepreneurs. By applying a systems-thinking lens, we aim to uncover how these interdependent influences contribute to the long-term evolution of entrepreneurial motivation.

Building on this foundation, our study aims to address the following questions:

- How do personal, social, and contextual factors determine the long-term motivations of established entrepreneurs?

- What role do perceptions of opportunity, risk, and external validation (e.g., media exposure) play in determining entrepreneurial aspirations beyond the startup phase?

- To what extent do sustainability awareness and social-responsibility considerations influence the strategic direction of established businesses?

- How do family business legacies and intergenerational dynamics contribute to entrepreneurial motivation in mature ventures?

By addressing these questions, this study seeks to contribute to a more context-sensitive understanding of how entrepreneurial motivation develops over time, which may inform future work by policymakers, entrepreneurship educators, and business support organizations. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the theoretical background on entrepreneurial motivation, sustainability, and systems thinking. Section 3 outlines our methodology, including data sources, sample selection, and analytical approach. Section 4 presents the results of our multivariate multiple regression analysis. Finally, Section 5 and Section 6 discuss the findings; their theoretical and practical implications; their limitations; and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Underpinnings

2.1. A Systems Perspective on Entrepreneurial Motivations

Entrepreneurial motivation is shaped by a dynamic interplay of economic conditions, institutional frameworks, social norms, and individual aspirations. While early-stage entrepreneurship research often focuses on the initial decision to start a business—driven by necessity, opportunity recognition, or innovation incentives—less attention has been paid to how motivations evolve as ventures mature. Established entrepreneurs navigate complex environments where strategic goals are influenced by both personal ambitions and systemic factors, such as regulatory pressures, industry expectations, and broader socioeconomic shifts [9,10,11].

A systems perspective provides a useful framework for understanding how entrepreneurial motivations emerge and adapt over time. General Systems Theory (GST) [5] highlights that motivations are not formed in isolation but rather through feedback loops within interconnected ecosystems. Entrepreneurs continuously interact with external conditions—such as market fluctuations, policy changes, and shifting consumer values—which, in turn, determine their strategic orientations [7]. This contextualized approach moves beyond trait-based explanations, emphasizing the interconnection of economic, social, and institutional factors [12,13].

Furthermore, entrepreneurial motivations are not static but adaptive, responding to both external disruptions and internal business milestones [14]. Senge [6] describes this dynamic process as one of continuous learning and strategic recalibration, where entrepreneurs refine their objectives based on accumulated experience, competitive pressures, and emerging opportunities [15]. Success in one phase of the business cycle may reinforce expansionary ambitions, while external shocks—such as economic crises or technological disruptions—may prompt a shift toward risk-averse strategies [16].

2.1.1. Motivational Pathways in Entrepreneurial Systems

From a systems perspective, entrepreneurial motivations can be categorized into several interdependent pathways, each determined by external influences and internal priorities. Prior research suggests that established entrepreneurs often fall into one of the following broad motivational orientations:

- Social-impact orientation—Entrepreneurs who seek to integrate ethical considerations, sustainability goals, and social change into their business models. These individuals are often influenced by institutional pressures; stakeholder expectations; and awareness of sustainability frameworks, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [17,18].

- Wealth accumulation and financial growth—Entrepreneurs who prioritize financial success, market expansion, and long-term wealth-building. This motivation is frequently reinforced by media narratives, cultural norms surrounding success, and perceived business opportunities [19,20,21].

- Family business continuity and legacy-building—Entrepreneurs embedded in family enterprises often prioritize intergenerational succession, socioemotional wealth, and reputation preservation. Their motivations are determined by family governance structures, societal expectations, and exposure to successful multigenerational firms [22,23].

- Necessity-driven entrepreneurship and financial security—Entrepreneurs who maintain their ventures primarily to ensure stable income and financial resilience rather than expansion or innovation. This motivation is particularly pronounced in contexts of economic uncertainty, limited institutional support, and heightened fear of failure [24,25,26].

Rather than viewing these as mutually exclusive categories, a systems perspective suggests that entrepreneurs often navigate multiple motivations simultaneously. For example, an entrepreneur may initially be driven by financial goals but later transition toward social-impact or family-legacy concerns, depending on the evolving business context [27]. This is further supported by recent findings that emphasize the dual influence of motivation and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on business success in emerging markets [3].

2.1.2. Transition to Specific Motivational Constructs

While many economic theories emphasize rational choice and profit maximization, psychological perspectives highlight identity, self-actualization, and personal fulfillment as core entrepreneurial drivers [28]. At the same time, institutional theory suggests that regulatory environments, social norms, and cultural expectations determine entrepreneurial motivation by influencing perceived feasibility and desirability [10].

Against this backdrop, we examine how four key motivational orientations emerge from these systemic interactions. Specifically, we analyze how social and sustainability-driven motivations, financial aspirations, family business continuity, and necessity-driven entrepreneurship evolve in response to economic, cultural, and institutional forces. These motivations—while distinct—are deeply embedded in the entrepreneurial ecosystem, where overlapping factors such as opportunity perception, sustainability awareness, media exposure, and business networks interact to shape long-term entrepreneurial trajectories. In the following sections, we explore each motivational dimension in greater depth, integrating insights from existing research to develop hypotheses that link entrepreneurial motivations to broader systemic factors.

2.2. Motivational Drivers of Established Entrepreneurs

2.2.1. Social Impact, Sustainability, and Prosocial Aspirations

The notion of “making a difference” in entrepreneurship reflects a shift toward the integration ethical considerations, sustainability principles, and social impact into business strategies. Entrepreneurial motivations emerge from interdependent economic, social, and environmental systems. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) serve as a globally recognized benchmark for responsible business practices, reinforcing the systemic nature of sustainability-driven entrepreneurship [18]. Entrepreneurs aware of these frameworks tend to broaden their motivational scope beyond profit maximization, particularly once they achieve financial stability [17]. These individuals perceive entrepreneurship as an opportunity to address global challenges—such as climate change, inequality, or health crises—through innovative solutions or products [29,30]. This shift aligns with self-determination theory, which suggests that once extrinsic needs (e.g., financial security) are met, individuals become more inclined toward intrinsic goals, such as prosocial engagement and ethical leadership [31,32]. Sustainability practices eventually become integral to long-term strategies for socially conscious entrepreneurs. For established entrepreneurs, intrinsic drivers such as personal fulfillment, social responsibility, and legacy-building often gain prominence as ventures mature [28]. With increased financial security and strategic experience, business owners may pivot from short-term survival concerns to broader societal objectives [33].

Moreover, media coverage plays a crucial role in shaping entrepreneurial motivations by showcasing role models who successfully integrate social impact into profitable ventures [34,35]. Exposure to sustainability-driven entrepreneurial narratives reinforces the belief that financial success and social impact are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary [36]. Entrepreneurs embedded in ecosystems that encourage responsible business conduct are therefore more likely to develop long-term commitments to sustainability and ethical leadership [37].

These considerations lead to the following hypothesis:

H1:

The motivation “to make a difference in the world” is stronger among entrepreneurs who are aware of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and who demonstrate social sensitivity in their business decision-making and have reached a level of financial stability.

This hypothesis aligns with systems theory, where socially responsible decision-making emerges as an outcome of interdependent market forces, regulatory frameworks, and ethical imperatives. Established entrepreneurs who recognize the systemic repercussions of their business decisions are thus expected to place greater emphasis on creating positive societal change through their ventures. In line with this, research also shows that proactive traits such as initiative can enhance the impact of intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy on entrepreneurial orientation [38].

2.2.2. Financial Motivation and Economic Opportunity

Financial success is a central entrepreneurial driver, influencing decision-making, risk-taking, and long-term strategy. Although often seen as an individual goal, financial aspirations are determined by systemic factors, such as economic conditions, institutional environments, and cultural narratives [19,20]. Entrepreneurs navigate a complex interplay of opportunity recognition, risk perception, and societal expectations that informs the desirability of wealth accumulation.

From a systems perspective, financial goals result from interactions between market dynamics, perceived risks, and sociocultural influences. Favorable economic conditions and resource access promote financial ambition, while uncertainty and fear of failure reinforce wealth-seeking as a protective strategy [25,26]. These motivations evolve with external circumstances and entrepreneurial experience.

Established entrepreneurs tend to balance ambition with caution, adopting financial strategies that promote long-term resilience.

Beyond direct economic considerations, external societal narratives—particularly media portrayals of entrepreneurial success—play a significant role in shaping financial aspirations. The glorification of wealth accumulation in entrepreneurial culture often frames financial success as a key indicator of legitimacy and professional achievement [39]. High-profile success stories of rapid scaling, venture capital investments, and lucrative acquisitions reinforce the perception that wealth accumulation is both desirable and attainable [35].

Entrepreneurs exposed to such narratives are more likely to align their own goals with dominant financial success models, internalizing media-driven expectations of what defines a “successful entrepreneur”. This social validation effect can reinforce aggressive financial strategies, high-risk investments, and expansionist business models that align with culturally endorsed success patterns [36]. In this way, entrepreneurial wealth-building motivations are not just a product of individual ambition but are actively shaped by societal expectations and external validation mechanisms.

In line with the theoretical framework presented, we propose the next hypothesis:

H2:

The motivation “to build great wealth or a very high income” is stronger among entrepreneurs who perceive greater business opportunities, are aware of the risks of failure, are influenced by positive entrepreneurial narratives in the media, and differ across age groups.

This hypothesis aligns with systems theory, in which financial motivation is viewed as an outcome of interconnected economic conditions, risk considerations, and societal narratives. Rather than being a fixed personal trait, financial ambition emerges in response to external stimuli, shaping entrepreneurial strategies in dynamic ways.

2.2.3. Family Legacy and Business Continuity

Family businesses hold a distinctive position within the entrepreneurial ecosystem, where motivations extend beyond profit to include legacy, stability, and socioemotional wealth [40]. Family firms operate within interdependent systems where governance, ownership, and succession structures determine entrepreneurial motives [41]. These firms place high value on socioemotional wealth—non-financial benefits, such as family control and reputation—which reinforces the desire to preserve legacy [23,42].

While formal mechanisms like succession planning support generational transitions, informal dynamics—such as patriarchal expectations—still limit gender equality in leadership [43]. However, growing emphasis on inclusivity, sustainability, and professionalization is transforming family firm continuity [44].

Media narratives play a key role in legitimizing the continuation of family businesses. Positive portrayals of multigenerational firms frame legacy as both respectable and viable [45], encouraging younger generations to participate [46]. Evolving representations now highlight diverse leadership, reinforcing that entrepreneurial tradition is shaped by social validation and not only inherited [36].

While the broader socioemotional wealth perspective emphasizes multiple drivers of family business continuity—such as succession planning, emotional attachment, and identity—this study focuses specifically on the influence of media portrayals. This focus is theoretically grounded in the increasing role of societal narratives and cultural validation in shaping entrepreneurial motives, especially among younger generations. Media representations offer a tangible and externally driven mechanism through which the value of family legacy is reinforced, making them particularly relevant within a systems-thinking framework. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3:

The motivation “to continue family tradition” is stronger among entrepreneurs who are exposed to positive media portrayals of successful family businesses.

This hypothesis aligns with the socioemotional wealth framework, particularly in how family business continuity is shaped not only by internal family dynamics but also by broader cultural and social-validation mechanisms. In this context, media portrayals represent an important channel through which the value of entrepreneurial legacy is legitimized and reinforced.

2.2.4. Necessity-Driven Entrepreneurship and Risk Perception

Although entrepreneurship is often associated with opportunity and innovation, many established entrepreneurs continue to be driven by necessity. Economic uncertainty, limited resources, and systemic barriers frequently reinforce motivations focused on stability rather than growth. Unlike their opportunity-driven counterparts, these entrepreneurs prioritize consistent income over expansion or innovation.

From a systems perspective, necessity-driven entrepreneurship emerges in response to external constraints. Risk aversion, fear of failure, and low proactivity sustain a survival-oriented mindset, determined by broader economic and institutional factors.

Even after overcoming early-stage barriers, entrepreneurs in unstable contexts often remain necessity-oriented [25]. Persistent fear of failure—fueled by financial insecurity and market volatility—limits willingness to invest in growth [24,26]. Limited confidence and proactivity further reinforce this defensive approach [47,48], resulting in reduced growth aspirations and innovation engagement [49]. Entrepreneurs’ strategies are also shaped by systemic factors, such as policy frameworks, risk culture, and market structures [50]. In contexts where failure is stigmatized or safety nets are weak, cautious, incremental strategies prevail [25]. Even socially oriented entrepreneurs tend to prioritize financial security over innovation [27], especially when institutional support is lacking [51]. Recent data from the COVID-19 period further show how crises can shift motivations and reinforce risk-averse behaviors [35]. Based on these insights, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4:

The motivation “to earn a living” is stronger among entrepreneurs who experience fear of failure, show lower entrepreneurial proactivity, and perceive greater external constraints.

This hypothesis highlights the interplay between structural barriers and individual risk perceptions in shaping long-term entrepreneurial strategies. Drawing on prior research, H4 focuses on three key drivers of necessity-driven motivation—fear of failure, low proactivity, and perceived external constraints—as core psychological and contextual barriers to opportunity-oriented entrepreneurship.

2.3. Summary and Theoretical Integration

In light of the four motivational dimensions—to make a difference, to build great wealth, to continue a family tradition, and to earn a living—we see how each one emerges from a confluence of interdependent factors. Entrepreneurs operate within sociocultural contexts that shape their risk perceptions and opportunity recognition [25,50], engage with media narratives that legitimize certain aspirations (e.g., wealth-building or family continuity) while marginalizing others [39], and exist within family governance structures that can foster legacy preservation or open the door to new innovations [22,40]. At the same time, personal attitudes—such as fear of failure or sustainability awareness—interact with these broader systems to determine whether entrepreneurs lean toward growth, social impact, or stable income objectives [24,26,27,37].

By focusing on the post-startup stage, our study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature, which frequently concentrates on nascent or early-stage ventures [52]. Exploring how motivations evolve—and interact—once businesses have reached a measure of stability addresses a significant gap in understanding later-stage entrepreneurial behavior.

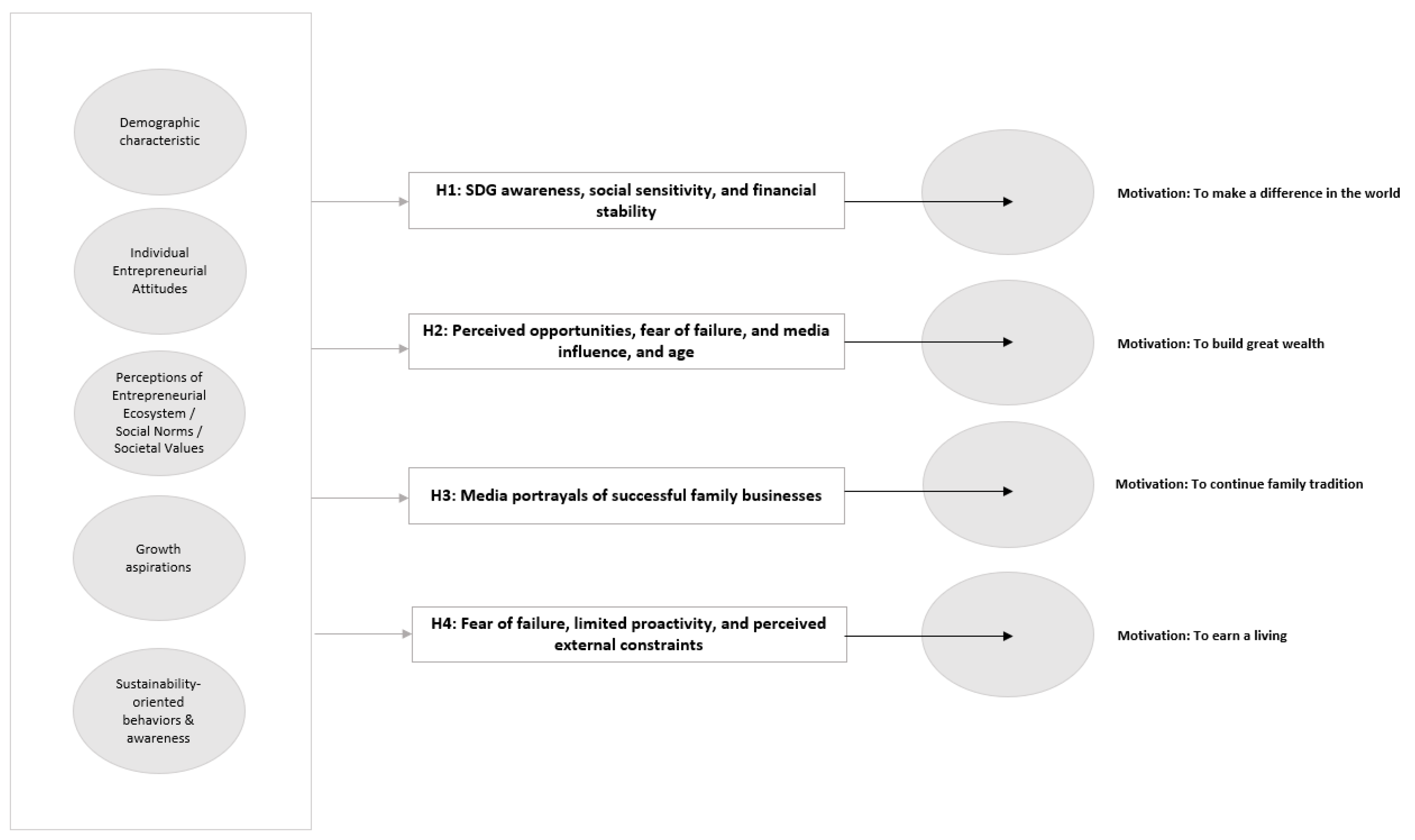

The four hypotheses advanced in the previous subsections (H1 through H4) reflect this systemic view. Each hypothesis positions a unique set of factors as key predictors of a respective motivation. Our research model, as illustrated in Figure 1, will be further examined in the forthcoming Methodology and Results sections. We employ a multivariate multiple regression framework to test research hypotheses, providing insights into how system elements, in tandem, influence established entrepreneurs’ motivation profiles. These findings offer nuanced perspectives for policymakers, educators, and advisors aiming to support the long-term sustainability and innovation of mature ventures.

Figure 1.

Research model: motivational drivers of established entrepreneurs. Source: own research.

3. Methodology

This section describes the data source, sample selection, operationalization of variables, and analytical procedures employed in this study. Our investigation is based on the 2023 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey (APS) data for Croatia.

3.1. Data Source and Sample

The GEM APS methodology involves a standardized procedure of household selection and face-to-face (or telephone/online, depending on the national survey design) interviews with randomly sampled adults. In Croatia, the 2023 APS data collection yielded responses from 2000 individual representative of the adult population aged 18–64.

From the full sample, 103 respondents qualified as established entrepreneurs. These entrepreneurs have successfully moved beyond the initial startup phase and have continuously paid themselves and/or other employees for at least 42 months. Focusing on this specific subgroup allows us to investigate the factors shaping entrepreneurs’ motivations once their ventures have reached a degree of stability. Prior research suggests that motivations at business inception may differ substantially from those operating in later stages of growth and development.

3.2. Description of Variables

The entrepreneurial motivation variables analyzed in this study were sourced directly from the standardized Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey (APS) questionnaire. These items are part of the core GEM instrument and have been consistently used across participating countries to ensure measurement validity and international comparability.

This study examines four dependent variables (i.e., entrepreneurial motivations), each assessed on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”):

- To make a difference in the world → motivated by social responsibility, sustainability, and societal impact.

- To build great wealth or a very high income → motivated by financial success and wealth accumulation.

- To continue a family tradition → motivated by family business continuity and legacy

- To earn a living → motivated by financial necessity, risk aversion, and security-seeking behavior.

These four motivational orientations correspond directly to the research hypotheses (H1–H4), which examine the systemic influences that shape entrepreneurial motivations in later-stage ventures. We include a set of independent variables that capture (1) demographic characteristics (e.g., age and education); (2) entrepreneurial attitudes (e.g., perceived opportunities and risk perception); (3) perceptions of the entrepreneurial ecosystem (e.g., ease of starting a business and social norms); (4) growth aspirations (e.g., job creation expectations); and (5) sustainability-oriented behaviors and awareness (e.g., SDG awareness and social/environmental considerations). By integrating these diverse factors, our model seeks to uncover both direct and systemic influences on entrepreneurial motivation beyond the startup phase. The specific groups of predictors included are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Groups of predictors variables.

Our overarching goal is to understand how each of these factors shapes the four core motivations among established entrepreneurs, highlighting both shared and unique influences. While all independent variables were tested for their impact on entrepreneurial motivations, the study particularly focuses on the relationships hypothesized based on prior research (H1–H4).

3.3. Analytical Approach

To capture the simultaneous effects of the various predictors on the four distinct entrepreneurial motivations, we employ multivariate multiple regression (MMR). This approach extends ordinary multiple regression by allowing multiple dependent variables to be modeled concurrently. It is particularly useful when the dependent variables may be correlated or when researchers wish to examine whether independent variables exert different magnitudes and directions of influence across multiple outcomes [53,54].

Formally, the MMR model can be expressed as follows:

where

Y = Xβ + ε

Y is the matrix of dependent variables (in this study, the four entrepreneurial motivations);

X is the matrix of independent variables (sociodemographic characteristics, attitudes, sustainability-related factors, etc.);

β is the matrix of coefficients to be estimated, representing the effect of each independent variable on each motivation dimension;

ε is the matrix of error terms.

Prior to estimation, we conducted checks for missing data, outliers, and multicollinearity. Observations with missing values on key predictors were excluded to ensure consistent sample sizes across the models. Given that this subsample consists of established entrepreneurs, weighting adjustments beyond the standard GEM procedures were not applied.

The use of multivariate multiple regression is particularly appropriate for this study, as the four motivational orientations are conceptually interrelated and empirically likely to be correlated. Estimating separate regression models for each motivation would overlook this interdependence and potentially produce biased or inefficient estimates. By jointly modeling the four outcomes, the MMR approach takes into account the covariance structure among the motivations, providing a more comprehensive view of how sociodemographic, attitudinal, and contextual factors shape the entrepreneurial motivation landscape. Instead of running separate regressions for each outcome—which can overlook potential correlations among the motivations—this integrative approach offers richer insights into the complexity of entrepreneurial behavior in later stages of venture development.

4. Results

This section presents the findings of the multivariate multiple regression (MMR) analysis, organized by the four primary motivational dimensions. Each subsection aligns with the overarching hypotheses derived from the literature review, allowing for a coherent narrative linking theoretical expectations with empirical evidence. Table 2 displays only those variables that exhibit a statistically significant association (at p < 0.10) with at least one of the four dependent variables.

Table 2.

Regression analysis of predictors for different entrepreneurial motivations.

4.1. Hypothesis Testing

Hypothesis 1 (H1) proposed that the motivation “to make a difference in the world” is stronger among entrepreneurs who are aware of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), demonstrate social sensitivity in their business decision-making, and have reached a level of financial stability. This hypothesis is grounded in systems theory, which suggests that entrepreneurial motivations emerge from the dynamic interplay of ethical imperatives, societal norms, and contextual forces. In this view, prosocial and impact-driven objectives are not isolated values but develop through sustained exposure to responsibility-oriented ecosystems—particularly once entrepreneurs move beyond short-term survival concerns. The MMR analysis supports this hypothesis. Social considerations (SOC_HI) merged as a positive and statistically significant predictor of this motivation (B = 1.1581, SE = 0.427, p = 0.008). This finding indicates that entrepreneurs who actively consider social implications in their decision-making are more likely to be motivated by the desire “to make a difference in the world”—as framed in GEM terminology—and to integrate prosocial and impact-driven objectives into their long-term business strategies. Additionally, SDG awareness (SDG_AWARE1) also shows a positive and significant effect (B = 0.8991, SE = 0.331, p = 0.008), suggesting that familiarity with international sustainability frameworks strengthens entrepreneurs’ aspiration to create positive societal change. These findings reinforce the systems perspective, demonstrating that sustainability awareness and ethical decision-making are not isolated individual traits but emerge from a broader interaction between institutional pressures, regulatory expectations, and personal values. While financial stability was not directly measured in this study, the absence of necessity-driven variables (e.g., fear of failure) as significant predictors, combined with strong effects of SDG awareness and social prioritization, may suggest that entrepreneurs motivated “to make a difference” tend to operate beyond basic survival concerns. Nevertheless, future studies should explicitly measure financial security to better assess its role as a precondition for intrinsic, prosocial motivation.

Hypothesis 2 (H2) posited that the motivation “to build great wealth or a very high income” is stronger among entrepreneurs who perceive greater business opportunities, experience a heightened fear of failure, are influenced by positive media portrayals of entrepreneurial success, and differ across age groups. This hypothesis aligns with the systems perspective, which views financial motivation not merely as an internal disposition but as a response shaped by contextual forces—including opportunity perception, individual risk aversion, and cultural narratives that valorize wealth accumulation. Age was included as a potential demographic moderator reflecting life-stage and experience-based variation in financial ambition. The MMR analysis supports this hypothesis. Age (AGE) exhibits a significant negative relationship with wealth motivation (B = −0.0377, SE = 0.013, p = 0.0065), indicating that younger entrepreneurs are more inclined to pursue substantial financial gains. This aligns with the notion that younger cohorts have longer time horizons and greater risk tolerance, enhancing growth ambitions. Opportunity perception (OPPORT) shows a significant positive effect (B = 0.2103, SE = 0.097, p = 0.0331), confirming that perceived market opportunities stimulate wealth-oriented motivations. Additionally, fear of failure (FEARFAIL) is also positively associated with this motivation (B = 0.1788, SE = 0.089, p = 0.0482), suggesting financial goals may function not only as aspirational targets but also as strategic responses to perceived insecurity. Finally, media exposure (NBMEDIA) is a positive and significant predictor of wealth accumulation motivation (B = 0.2351, SE = 0.105, p = 0.0275), indicating that cultural validation through entrepreneurial success stories may reinforce the desirability of wealth accumulation. Together, these findings confirm that financial motivation is shaped by both individual perceptions and broader sociocultural narratives.

Hypothesis 3 (H3) proposed the motivation “to continue a family tradition” is stronger among entrepreneurs who are exposed to positive media portrayals of successful family businesses. This hypothesis is grounded in the systems perspective, which suggests that entrepreneurial motivations are shaped not only by internal family dynamics but also by external validation mechanisms. Media representations serve as powerful cultural signals that legitimize the continuity of family firms and reinforce the value of entrepreneurial legacy, particularly among newer generations of business owners. The MMR analysis supports this hypothesis. Media exposure (NBMEDIA) emerged as the only significant predictor of the motivation “to continue a family tradition” (B = 0.4257, SE = 0.137, p = 0.0026), highlighting the influential role of external narratives in reinforcing family business continuity. Entrepreneurs who frequently encounter media portrayals of successful family firms may perceive their own business legacy as more socially and economically valuable, thereby strengthening their commitment to sustaining the enterprise across generations. Notably, other sociodemographic and attitudinal variables did not show significant effects, suggesting a relatively homogeneous motivational pattern among entrepreneurs embedded in family businesses. This may reflect shared characteristics such as inherited resources, established governance structures, and deeply ingrained cultural values, which inherently support the continuity of family enterprises. Unlike entrepreneurs motivated by financial gain or social impact, those driven by legacy appear to be less responsive to external economic incentives or individual risk factors, instead anchoring their motivation in familial expectations and intergenerational identity.

Hypothesis 4 (H4) proposed that the motivation “to earn a living” is stronger among entrepreneurs who experience fear of failure, exhibit lower levels of entrepreneurial proactivity, and perceive greater external constraints. This hypothesis is grounded in the systemic perspective of necessity-driven entrepreneurship, which posits that concerns over financial security, structural barriers, and risk aversion continue to shape entrepreneurial behavior even beyond the startup phase. Rather than being driven by growth or innovation, such entrepreneurs may adopt survival-oriented strategies that prioritize stability and income maintenance in response to persistent uncertainty or limited institutional support. The MMR analysis partially supports this hypothesis. Fear of failure (FEARFAIL) emerged as a positive and statistically significant predictor of this motivation (B = 0.2700, SE = 0.096, p = 0.0063), indicating that entrepreneurs who are more risk-averse tend to prioritize financial stability over opportunity-driven expansion. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that fear of failure can drive individuals to pursue self-employment primarily as a survival strategy rather than as a growth-oriented endeavor. In contexts of economic uncertainty, stable income generation may function as a protective mechanism against financial insecurity. Entrepreneurial proactivity (PROACT) also showed a positive but only marginally significant relationship with this motivation (B = 0.1861, SE = 0.102, p = 0.0716). This suggests that even necessity-driven entrepreneurs may demonstrate initiative —though not necessarily in pursuit of growth, but rather to secure continuity and resilience. Such findings highlight the adaptive nature of necessity-based entrepreneurship, where limited risk-taking is accompanied by active effort to maintain business operations. Moreover, job growth expectations (JOBS) exhibited a marginally significant negative effect (B = −0.0018, SE = 0.001, p = 0.0935), indicating that entrepreneurs motivated by financial necessity are less likely to plan for expansion or hiring. This supports the view that necessity-driven businesses are typically subsistence-oriented rather than growth-oriented. Interestingly, SDG awareness (SDG_AWARE1) shows a weak but positive significant effect (B = 0.5070, SE = 0.316, p = 0.098), suggesting that some necessity-driven entrepreneurs may still integrate sustainability considerations into their strategies—particularly when such actions offer cost-saving or risk-mitigation benefits. While financial stability remains their primary driver, these entrepreneurs may align with broader social and environmental objectives under certain conditions.

4.2. Summary of Key Findings

The MMR analysis confirms the four overarching hypotheses, revealing distinct motivational patterns shaped by a complex web of sociodemographic, attitudinal, and contextual factors. Entrepreneurs motivated “to make a difference in the world” tend to integrate social responsibility and sustainability awareness into their decision-making, pointing to the prominence of values-based and prosocial orientations in shaping long-term goals. Financial ambition, expressed through the motivation “to build great wealth or a very high income”, is more prevalent among younger entrepreneurs and is significantly associated with perceived opportunities, fear of failure, and exposure to media narratives that glorify entrepreneurial success. These findings reflect a multifaceted blend of extrinsic incentives and contextual validation. In contrast, the motivation “to continue a family tradition” stands out as uniquely tied to positive media portrayals of family businesses. The absence of significant sociodemographic or attitudinal predictors suggests that family legacy is embedded in deeply rooted cultural norms and socially reinforced identities. Finally, the motivation “to earn a living” reflects a necessity-oriented profile, primarily shaped by fear of failure and low growth aspirations. However, the marginally significant role of entrepreneurial proactivity suggests that even under conditions of constraint, entrepreneurs may actively pursue stability and continuity. Interestingly, a weak association with SDG awareness hints that necessity-driven business models may still align—perhaps pragmatically—with sustainability goals when these offer risk-mitigating or cost-saving benefits.

These findings underscore the complexity of entrepreneurial motivations among established entrepreneurs, illustrating how systemic influences, cognitive drivers, and sociocultural narratives interact to shape diverse motivational pathways. They also reinforce the value of a systems-based perspective, providing a nuanced understanding of how established entrepreneurs navigate and balance financial ambition, social impact, family continuity, and survival-oriented needs within an evolving entrepreneurial ecosystem.

5. Discussion

This study provides novel insights into the motivational dynamics of established entrepreneurs by applying a systems-thinking perspective. Rather than treating motivations as isolated drivers, our findings demonstrate how financial goals, prosocial values, family legacies, and survival needs are shaped through the interplay of individual traits, social expectations, and broader contextual influences. By employing a multivariate multiple regression approach, we capture the interdependencies among multiple predictors and motivational outcomes—an important methodological contribution, given the often overlapping and multidimensional nature of entrepreneurial decision-making. The results reveal distinct yet interconnected motivational pathways, reflecting the complexity of entrepreneurship beyond the startup phase.

Our findings support the hypothesis that established entrepreneurs who prioritize social responsibility (SOC_HI) and are aware of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG_AWARE1) are significantly more likely to be motivated “to make a difference in the world”. This result aligns with the systems perspective, which suggests that motivations are co-constructed by a dynamic interplay of personal values, societal expectations, and sustainability frameworks [37,55]. These findings reinforce prior research emphasizing the growing importance of prosocial and sustainability-driven motivations in entrepreneurship [8]. Notably, the results suggest that once financial stability is achieved, entrepreneurs may shift focus from economic survival to impact-oriented goals [28]. Our contribution extends this insight by demonstrating that such motivations are not purely altruistic; instead, they are embedded within a systemic context in which social considerations and SDG awareness jointly shape purpose-driven entrepreneurship. The significance of SDG awareness also suggests that exposure to global sustainability frameworks can actively shift entrepreneurial mindsets toward long-term societal contributions [33]. This aligns with studies that highlight the role of global awareness in fostering ethical business practices and social responsibility [8]. Consequently, policymakers and entrepreneurial support programs should leverage SDG frameworks to promote sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship among established business owners.

Our results reveal a multifaceted motivational pathway for wealth-building, driven by age, perceived opportunities, fear of failure, and media exposure. Specifically, younger entrepreneurs are more likely to prioritize financial gains, consistent with the literature on generational differences in growth aspirations and risk tolerance [21]. This demographic influence underscores the importance of life-cycle considerations in entrepreneurial motivation [19]. Both opportunity perception (OPPORT) and fear of failure (FEARFAIL) emerged as significant predictors, suggesting that pull factors (e.g., perceived market potential) and push factors (e.g., risk aversion) interact to reinforce wealth-seeking behaviors. This finding supports the push–pull framework, where financial security is pursued as a buffer against perceived risks [25]. It also resonates with opportunity-recognition theory, emphasizing the cognitive link between opportunity perception and growth-oriented motives [26]. In addition, media exposure (NBMEDIA) positively influences wealth-building motivation, reinforcing the role of societal narratives in shaping entrepreneurial aspirations [39]. This aligns with social learning perspectives, where success stories provide cognitive scripts for financial achievement [56]. Given the symbolic prestige often associated with entrepreneurial success, policymakers and support organizations could leverage media narratives strategically to promote growth-oriented entrepreneurship and reinforce positive entrepreneurial role models.

This study reveals that exposure to positive media narratives is the sole significant predictor of the motivation “to continue a family tradition”. This underscores the influential role of societal narratives in legitimizing family business continuity, consistent with socioemotional wealth theory [22]. Positive media portrayals serve as cultural validators, reinforcing the perceived legitimacy and prestige of sustaining family legacies [57]. Unlike other motivational pathways, this form of legacy-driven entrepreneurship does not appear to be influenced by sociodemographic or attitudinal variables, suggesting that family continuity is deeply embedded in cultural norms and socially reinforced expectations. This could be attributed to shared values and cultural norms within family business ecosystems, where continuity and legacy are deeply ingrained [40]. Our findings contribute to the literature on family entrepreneurship by illustrating how external narratives—particularly media portrayals—can shape internal motivational structures. This validates the systemic influence of cultural contexts on entrepreneurial behavior. The results emphasize that motivations to continue a family tradition are less about individual choice and more about navigating cultural expectations and societal legitimacy. This insight is particularly relevant for policymakers and advisors seeking to support family-business succession, suggesting that strategic communication and public narratives could play a vital role in fostering generational continuity.

The analysis also indicates that necessity-driven motivations, including “to earn a living”, are significantly influenced by fear of failure and modest growth aspirations. This supports the push-factor framework, where risk aversion and financial insecurity reinforce subsistence-oriented behavior [26]. Our findings resonate with the literature linking fear of failure with conservative strategic choices, emphasizing risk minimization and income stability [25]. The observed negative relationship between growth aspirations (JOBS) and necessity-driven motivation further illustrates the tension between opportunity/pull and necessity/push dynamics. Entrepreneurs projecting significant growth are less focused on subsistence income, supporting the notion that growth ambitions and necessity motivations operate on opposite ends of the entrepreneurial spectrum [19]. Interestingly, SDG awareness (SDG_AWARE1) demonstrated a marginally positive effect, suggesting that even necessity-driven entrepreneurs may integrate elements of social responsibility into their strategies—particularly when sustainability efforts align with cost-saving or risk-mitigation goals. This finding extends prior research by revealing the nuanced interplay between necessity-based motives and sustainability awareness [27]. Moreover, the data suggest that necessity-driven entrepreneurs are not purely reactive. Despite prioritizing income stability, some necessity-driven entrepreneurs still exhibit initiative and agency in their business activities. This challenges the traditional view of necessity-based entrepreneurship as purely reactive, as studies show that even in resource-constrained environments, entrepreneurs engage in adaptive strategies, leverage social networks, and implement incremental innovations to optimize their business outcomes [58,59].

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Key Findings and Implications

This study advances entrepreneurship theory by integrating systems thinking with motivational research, demonstrating that entrepreneurial motivations among established entrepreneurs are not static but rather co-constructed by interdependent personal values, societal norms, and cognitive drivers. By adopting a systems perspective, we challenge reductionist views of entrepreneurial motivation and emphasize the need for holistic, multivariate analyses that capture the dynamic interplay of systemic influences.

Our findings reveal four distinct motivational pathways: financial ambition, social impact, family business continuity, and necessity-driven entrepreneurship. Importantly, these motivations often coexist and interact, shaping entrepreneurial behavior as a result of the combined influence of individual traits, social expectations, and perceived opportunities. This interaction reinforces the importance of integrative frameworks for understanding entrepreneurial decision-making and calls for future research that further explores causal and synergistic effects between motivational orientations.

These insights offer significant implications for policy and practice. Effective support programs should not only be tailored to entrepreneurs’ specific drivers but also foster a deeper awareness of how motivations intersect with broader societal goals. For example, promoting awareness of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can encourage prosocial and sustainability-oriented entrepreneurship, while carefully crafted media narratives may inspire both financial ambition and continuity in family businesses. At the same time, entrepreneurship education should move beyond technical skills to incorporate systems thinking, helping entrepreneurs understand the complex interplay between personal motivations, societal values, and long-term strategic decisions.

This systems-based approach offers a richer understanding of how entrepreneurial motivations persist, adapt, and combine across the lifespan of a venture—providing actionable knowledge for scholars, educators, and policymakers committed to fostering resilient and impactful entrepreneurial ecosystems.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the research is based on data from a single geographical context (Croatia), which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should explore cross-cultural comparisons to assess whether the identified motivational pathways hold across diverse institutional and cultural environments.

Second, while the multivariate multiple regression model allows for the simultaneous analysis of multiple motivations and predictors, it does not capture the interactive or causal relationships between motivational orientations themselves. For example, the study does not examine how the desire for financial success might amplify or inhibit the pursuit of social impact. Future research should explore these potential interaction effects, possibly using structural equation modeling or longitudinal data to assess causal trajectories. Third, the cross-sectional nature of the data prevents the analysis of motivational change over time. Longitudinal studies would be valuable in capturing how motivations shift in response to systemic changes, such as economic crises, technological disruption, or policy reform. Fourth, the relatively small size of the subgroup of established entrepreneurs (N = 103) represents a further limitation. However, this number reflects the total number of respondents who met the definition of an established entrepreneur within the representative sample of 2000 adults, rather than being the result of additional sampling. While this ensures full coverage of the target subpopulation, it also naturally constrains the statistical power and generalizability of the findings for this specific group.

By addressing these limitations, future research can deepen our understanding of the complexity and evolution of entrepreneurial motivation in mature ventures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Š. and K.C.; methodology, N.Š.; validation, K.Š., K.C. and N.Š.; formal analysis, N.Š.; investigation, K.Š., K.C. and N.Š.; resources, K.Š., K.C. and N.Š.; data curation, N.Š.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Š., K.C. and N.Š.; writing—review and editing, K.Š., K.C. and N.Š.; visualization, K.Š., K.C. and N.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Authors acknowledge the financial support from the Ministry of Economy, Republic of Croatia (research project Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Croatia); and the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P5–0023, “Entrepreneurship for Innovative Society”).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data comes from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) global study and will not be available for another three years. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Global Entrepreneurship Monitor global study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, S.; Venkataraman, S. The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarman, R.; Affandi, A.; Priadana, S.; Djulius, H.; Alghifari, E.S.; Setia, B.I. Business Success in Emerging Markets: Entrepreneurial Motivation and Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2025, 35, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, S.; Amorós, J.E.; Arreola, D.M. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2014 Global Report; Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA): London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L.V. General System Theory: Essays on Its Foundation and Development; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D. The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economy Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship; Babson Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Project; Babson College: Babson Park, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, A. The Social and Institutional Context of Entrepreneurship. In Crossroads of Entrepreneurship; Corbetta, G., Huse, M., Ravasi, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Steyaert, C.; Katz, J. Reclaiming the Space for Entrepreneurship in Society: Geographical, Discursive, and Social Dimensions. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2004, 16, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Kenney, M.; Mustar, P.; Siegel, D.; Wright, M. Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. Entrepreneurial Cognition: Exploring the Mindset of Entrepreneurs; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, S.; Šarlija, N. Social and Environmental Commitment Across the Early and Established Stages of Entrepreneurial Activity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics and Social Sciences, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania, 13–14 June 2024; Volume 6, pp. 537–546. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, E.; Spigel, B. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems; USE Discussion Paper Series; Tjalling C. Koopmans Research Institute: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 16, pp. 1–15. Available online: https://www.uu.nl/sites/default/files/rebo_use_dp_2016_1613.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Aldrich, H.E.; Ruef, M.; Lippmann, S. Organizations Evolving, 3rd ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chenavaz, R.Y.; Couston, A.; Heichelbech, S.; Pignatel, I.; Dimitrov, S. Corporate social responsibility and entrepreneurial ventures: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorio, A.M.; Puumalainen, K.; Fellnhofer, K. Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions in sustainable entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 359–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.; Koellinger, P. I can’t get no satisfaction—Necessity entrepreneurship and procedural utility. Kyklos 2009, 62, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Fernández-Serrano, J.; Romero, I. Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: The mediating effect of culture. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2013, 33, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Wang, T. Analysis of entrepreneurial motivation on entrepreneurial psychology in the context of transition economy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 680296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirico, F.; Sirmon, D.G.; Sciascia, S.; Mazzola, P. Resource orchestration in family firms: Investigating how entrepreneurial orientation, generational involvement, and participative strategy affect performance. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2011, 5, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Romero, M.J.; Martínez-Alonso, R.; Casado-Belmonte, M.P. The influence of socio-emotional wealth on firm financial performance: Evidence from small and medium privately held family businesses. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2020, 40, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cacciotti, G.; Hayton, J.C. Fear and entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C.; Henley, A. “Push” versus “pull” entrepreneurship: An ambiguous distinction? Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N.F., Jr.; Reilly, M.D.; Carsrud, A.L. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2000, 15, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murnieks, C.Y.; Klotz, A.C.; Shepherd, D.A. Entrepreneurial motivation: A review of the literature and an agenda for future research. J. Organ. Behav. 2020, 41, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsrud, A.; Brännback, M. Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2011, 49, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirzaker, R.; Galloway, L.; Muhonen, J.; Christopoulos, D. The drivers of social entrepreneurship: Agency, context, compassion and opportunism. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2021, 27, 1381–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamini, R.; Soloveva, D.; Peng, X. What inspires social entrepreneurship? The role of prosocial motivation, intrinsic motivation, and gender in forming social entrepreneurial intention. Entrep. Res. J. 2022, 12, 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J. Sustainability through People, Mindset, and Culture. Soc. Dev. Issues 2024, 46, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, N.; Hessels, J.; Schutjens, V.; Van Praag, M.; Verheul, I. Entrepreneurship and role models. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N.; Neira, I.; Atrio, Y. Analysis of Entrepreneurs’ Motivations and Role Models for Growth Expectations in the Time of Coronavirus. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2024, 20, 841–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U.; Folmer, E. Context and Social Enterprises: Which Environments Enable Social Entrepreneurship? Economics, Finance and Entrepreneurship; Aston Business School: Birmingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Patzelt, H. The new field of sustainable entrepreneurship: Studying entrepreneurial action linking “what is to be sustained” with “what is to be developed”. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogba, F.N.; Ogba, K.T.; Ugwu, L.E.; Emma-Echiegu, N.; Eze, A.; Agu, S.A.; Aneke, B.A. Moderating Role of Initiative on the Relationship between Intrinsic Motivation, and Self-Efficacy on Entrepreneurial Intention. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 866869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shi, L. Relationship between entrepreneurial motivation and crowdfunding success based on qualitative analysis-based on kickstarer website data. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2018, 102, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monticelli, J.M.; Bernardon, R.; Trez, G. Family as an institution: The influence of institutional forces in transgenerational family businesses. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, I.C.P.; Leitão, J.; Ferreira, J.; Cavalcanti, A. The socioemotional wealth of leaders in family firm succession and corporate governance processes: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023, 29, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mejía, L.R.; Haynes, K.T.; Núñez-Nickel, M.; Jacobson, K.J.; Moyano-Fuentes, J. Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Adm. Sci. Q. 2007, 52, 106–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L.A.; Ruel, S.; Thomas, J.L. Prim‘A’geniture: Gender bias and daughter successors of entrepreneurial family businesses. Fem. Encount. J. Crit. Stud. Cult. Politics 2021, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domańska, A.; Hernández-Linares, R.; Zajkowski, R.; Żukowska, B. Family firm entrepreneurship and sustainability initiatives: Women as corporate change agents. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2024, 33, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, D.M.; Daniels, G.L.; Tait, G.B. The Family Factor: Earl G. Graves Sr.’s Legacy as Publisher of Black Enterprise. J. Mag. Media 2022, 23, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L.A.C.; Rodríguez, Y.E.; Sánchez, C. Women in the family business: Self and family’s influence on their perceptions of financial performance. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2023, 15, 341–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Wagner, M. Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs in Germany: Characteristics and earning s differentials. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2010, 62, 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnogaj, K.; Rebernik, M.; Hojnik, B.B. Supporting economic growth with innovation-oriented entrepreneurship. Ekon. Časopis/J. Econ. 2015, 63, 395–409. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M.; Bansal, S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Nangia, P. Necessity entrepreneurship: A journey from unemployment to self-employment. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2024, 43, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, F.A.M.C. Entrepreneurship and institutional uncertainty. J. Entrep. Public Policy 2023, 12, 10–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, E.; Jenkins, A.; Mark-Herbert, C. When fear of failure leads to intentions to act entrepreneurially: Insights from threat appraisals and coping efficacy. Int. Small Bus. J. 2021, 39, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, K.; Aranyossy, M. Nascent entrepreneurship–A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. Vez.-Bp. Manag. Rev. 2022, 53, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Pearson: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- York, J.G.; Venkataraman, S. The entrepreneur-environment nexus: Uncertainty, innovation and allocation. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ginesti, G.; Ossorio, M. The Impact of Family Determinants on the Media Coverage of Family Business Activism in Sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 2835–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Toyama, K.; Pal, J.; Dillahunt, T. Making a Living My Way: Necessity-driven Entrepreneurship in Resource-Constrained Communities. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2018, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantai, T.; Hauge, A.; Mei, X.Y. Unravelling the Dynamics of Necessity-Driven Entrepreneurs (NDEs) and Opportunity-Driven Entrepreneurs (ODEs): A Study of Immigrant Micro Enterprises (IMEs) in the Hospitality Industry. Tour. Hosp. 2024, 5, 1083–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).