Abstract

How is the circular economy policy utilised to transform mining facilities? This paper analyses projects undertaken under increasing pressure for economic and energy transformation (transitioning away from coal), using the example of the municipality of Brzeszcze in Poland. These projects highlight the planned key spatial initiatives deemed feasible for implementation in the area, emphasising mining facilities and waste management (including waste from outgoing industries) that can break or speed transformation. The article aims to analyse solutions considered viable for implementation in mining towns, which can contribute to a better understanding of transformations in other monofunctional industrial centres in Europe. Data were collected using the research by design method. It is concluded that stakeholders perceive the development of peripheral mining areas as an action that can significantly impact the conduct and perception of activities related to the circular economy while also promoting a gradual transition away from coal mining. The article highlights the role of initiatives enabling the combination of transformations with a slowdown in the pace of mining activity cessation, considering the need for waste management, energy transformation, and the financial and energy stability of urban centres that have long relied on coal.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Problem of Mining and Waste in Poland

How are locally degraded areas perceived by municipalities and enterprises grappling with the need for economic transformation: transitioning from coal to a circular economy? How is the need to manage the mining legacy reflected in the concepts for revitalising these spaces? This article presents arguments that the public accessibility of areas for waste collection and processing (i.e., substances or objects that the owner is disposing of, intends to dispose of, or is obligated to dispose of [1]), as well as “green” infrastructure, are being utilised to construct symbols of industrial change. Mining enterprises and municipalities, under political pressure, seek to demonstrate that they are implementing (or intend to implement) changes in line with EU directives. However, this does not necessarily entail reducing waste disposal or complete land remediation. What is being planned shapes societal perceptions of waste, degraded areas, and industrial infrastructure (existing and planned) through landscape formation. The article will illustrate how ideas of sustainable development, the circular economy, and the Green Deal are translated into plans for socially recognised, more sustainable, competitive, and resilient initiatives in a Polish mining town, which aims to secure funds from the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) and the Just Transition Fund (JTF).

Polish mining areas should be transformed into areas for obtaining energy from renewable sources and waste management (following the guidelines of the NRRP [2]). With the launch of financial resources from the NRRP and the Just Transition Fund, investors have increased interest in former mining areas for constructing photovoltaic and wind farms in recent years. The possibilities of building hydropower projects are also being analysed. Legal regulations allow land reclamation in mining areas using waste materials as a recovery process outside installations [3]. Based on Local Land Use Plans, areas abandoned by mining can be used for waste disposal and processing, such as in sand and gravel quarries or calamine, where waste rock or municipal waste is stored. However, waste management in Poland remains a problem, not only for the mining industry, but it is particularly significant, as mining waste accounts for over 50% of the waste generated in Poland [4]. Furthermore, managers of mining areas (as inferred from the authors’ experience) commonly struggle with the issue of waste deposited within their boundaries, whether legally or illegally, and determining who and when to supply them is often impossible.

What effects can we expect in the urban space when circular economy projects are undertaken in countries that are not very affluent, like Poland? The transition from a linear economy to a circular economy and energy transformation, according to EU guidelines [2], is intended to serve, among other things, the “recovery and resilience” of cities. Therefore, the focus is not on constructing new spatial-economic structures but on recovering existing ones to make them more resilient (see also [5]). This suggests that investments in “resilient” (sustainable, circular, low emission) projects addressing waste management issues will become increasingly common, even in mining cities with low resilience to economic and climate changes.

1.2. Managing Mining Areas as a Part of the “Green” Transformation

The International Council for Local Environmental Issues highlighted the necessity of striving for resilience in 2010 [6] and parameterised by Arup and The Rockefeller Foundation [7] as the City Resilience Index. The EU decision on energy transformation and “green” changes poses new challenges for policymakers, residents, and professionals involved in spatial planning (including mining-related areas, which is particularly relevant in this article). Within the National Reconstruction and Resilience Plan (NRRP) framework and the Just Transition Fund (JTF), mining regions will receive exceptional support to be transformed into sustainable areas based on a circular economy, low-emission—those perceived as resilient. Efforts to minimise the amount of waste generated are a business challenge, increasingly pressing in light of political decisions, urban sprawl, and environmental degradation. They go hand in hand with changes in the urban structure of existing centres and the acquisition of large areas for the production of energy (e.g., wind energy, photovoltaics), places for depositing and processing redundant materials, which will not be perceived as waste but as resources, as well as those aimed at ensuring better living conditions for residents.

Creating areas for renewable energy production and repurposing redundant facilities and waste in the environment to avoid opposition from residents is also an aesthetic issue. Areas abandoned by mining and industrial waste sites are perceived negatively by local communities as places where “nothing exists”, unattractive, and lacking (e.g., [8]), but also as liminal landscapes bearing witness to culture [9].

The planning approach where the waste heritage of former generations is visible in the landscape as part of culture is exemplified by the case of :metabolon in Lindlar by FSW Landschaftsarchitekten+Pier 7 Architekten (Figure 1). Located near Cologne, this facility indicates that the presence of waste and the need for its disposal can serve as a source of inspiration for the design of research, educational, and recreational landscapes. Considered an exemplary implementation of the Circular Economy principles [10], this site also serves as a platform where engineering knowledge in mining, still present in the region with active mining traditions, can be leveraged to develop landfill mining. Forms of waste storage and processing (landfills, recycling halls) were integrated into the project, aiming to change their societal perception [11]. This was achieved through the construction of undistinctive, unobtrusive educational and research buildings and relatively minor landscape interventions, including the construction of a viewpoint and sports-recreational facilities (trampolines, slides, pump track), pathways, and terraced stairs—within the landfill area.

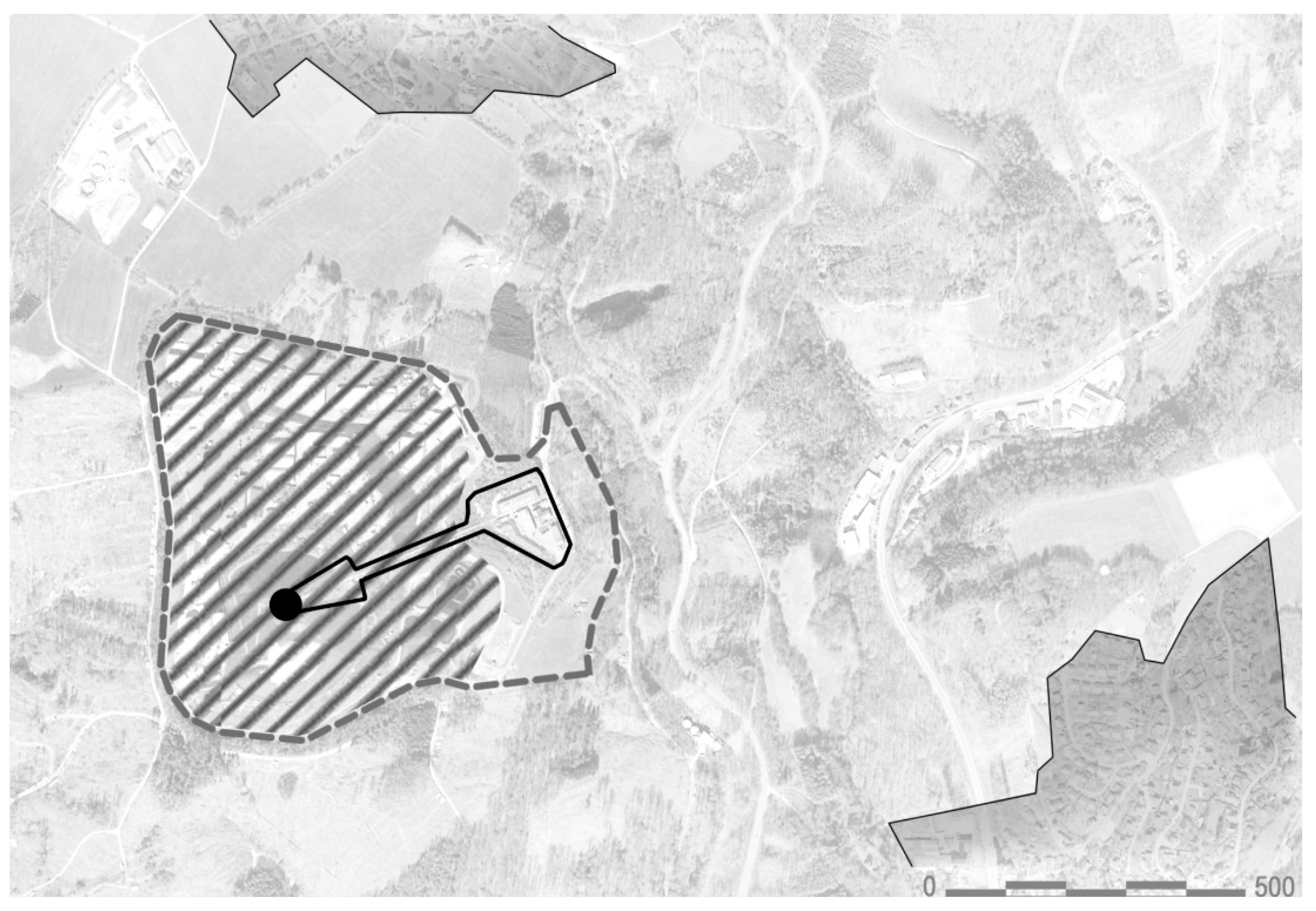

Figure 1.

:metabolon in Lindlar, where research–educational–recreational areas (outline) with a viewpoint (black dot) surrounded by waste management areas (hatched area) adjacent to settlements (grey outlined areas) were accepted by the community (Szewczyk-Świątek A., 2024).

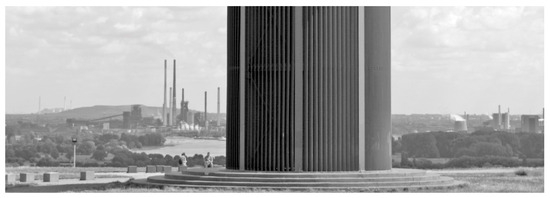

Over twenty years into the Ruhr Area’s transformation process, mining heaps and hazardous waste landfills are well-known examples of their conversion into public green areas through minimal interventions. Areas altered by spontaneous and assisted natural succession, equipped with relatively small architectural structures, serve as sites for landscape observation and evidence of the region’s transformation (e.g., [12]). This region is still transforming—nature is reclaiming industrial abandoned areas, yet many heavy industry enterprises continue to operate, generating waste (Figure 2). The “leaving everything alone” approach was adopted as a rule of the IBA-Emscher Park structural change program [13]. In other words, the shaping of the landscape was based on the assumption that in a region stimulated for years by heavy industry, a large portion of waste cannot be hidden or economically reused. However, time and the forces of nature can help shape more favourable opinions about them, limiting the extent of intervention (e.g., natural succession makes the area look green and socially acceptable, even though it may hide hazardous waste).

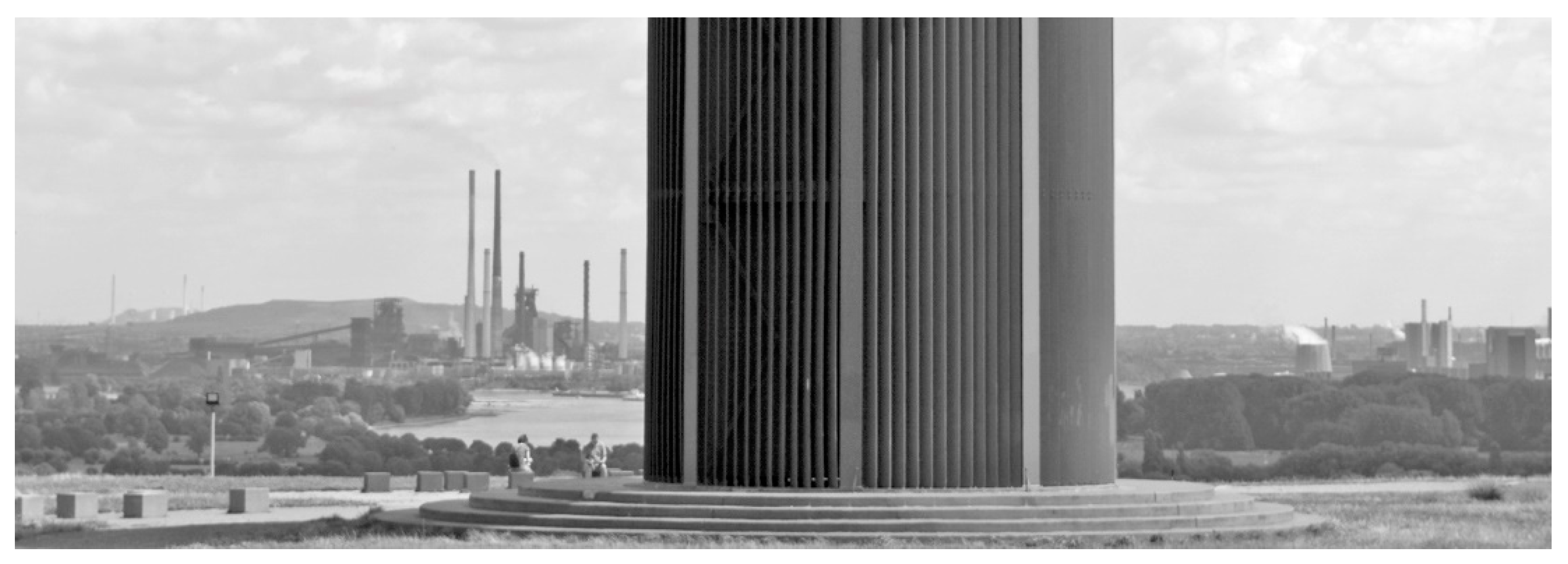

Figure 2.

The Rheinpreußen heap in Moers, Ruhr region, view of the surrounding areas, a quarter century after the start of transformation (photo by Szewczyk-Świątek A., 2015).

Wolfgang Wackerl, one of the planners responsible for transforming the Rhenish region, spoke [14] similarly about creating public spaces in areas abandoned by mining, which were undergoing structural changes. The minor design interventions undertaken “were meant to break the isolation [of this area] they were tools to focus attention (…), [indicating] that although it is not beautiful, it is interesting”. The Terranova project, described by Wackerl, carried out as part of Regionale 2010, as a “garden of technology”, is not aimed at comprehensively changing the environment’s appearance but rather drawing users’ attention to the aesthetics of slowly changing areas moving away from mining. The :metabolon was also part of the “garden of technology” and Regionale 2010.

What connects the described initiatives is the absence of camouflage, emphasising the visibility of active industry, waste, and nature’s actions. It is not an argument that waste has aesthetic value but rather that its impact on the environment is significant and that mining and nature play an essential role in shaping the landscape. By exposing waste, they highlight the processes of environmental exploitation and reclaiming degraded areas by nature.

Highlighting natural succession and ruderal greenery connects the well-known ideas regarding the role of nature in industrial areas in a particular way. On the one hand, natural areas are seen as a resource that should be consciously exploited economically, following the example of Hans Carl von Carlowitz (an economist and creator of sustainable development). On the other hand, natural areas are a tool for resolving conflicts between space users, as envisioned by Robert Schmidt, the first planner of the Ruhr Area. Schmidt aimed to conserve natural areas adjacent to industrial areas for recreation and the exploitation of shallow mineral deposits. In contemporary initiatives, reclaimed waste undergoing natural succession is showcased and made accessible for recreational purposes, and ruderal greenery is often a carefully conserved element of landscapes left by industry. There is no shortage of examples indicating the exceptional natural values and the need for species and area protection in post-mining areas [15].

Carefully designed green spaces accompanying industrial centres are characteristic of industrial-era urban planning. This paper’s thesis is that showcasing waste can be considered a distinctive element in designing post-industrial, circular environments. Nevertheless, the vital scientific problem is the lack of anticipating scientific ways to access and judge the impact of planning circular economy activities. The cases analysed in the paper show nothing is obvious if we consider transforming mining areas into circular economy areas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mining Town Brzeszcze

The previously posed questions are analysed in the context of preparations for Poland’s energy and economic transformation. The article examines initiatives to secure EU funds to transform the city of Brzeszcze into a hub for circular economy and green energy. Brzeszcze is a monofunctional city built around a hard coal mine (established in the early 20th century) in western Małopolska, Poland, with a population slightly exceeding 10,000 (2023 data). The local hard coal mine, PKW Mining Plant Brzeszcze, is still operating. However, since the 1990s (the time of Poland’s political and economic transformation), the issue of its closure has been consistently raised in public debate. The problem of the town’s financial future is becoming more pressing due to the need to reduce CO2 emissions, the policy of phasing out coal, and the ratified Paris Agreement. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan and Just Transition Fund (the establishment of which was one of the main goals of the UN climate summit COP24 held in nearby Katowice, Poland, 2018) are seen by local governments as sources of funding for transformative processes, which over the past 35 years have been perceived as threats for local emission-based economies.

However, the closure of the mine, which employs around 1600 relatively well-paid workers, does not have many supporters. Despite top-down support, the economic transformation of the 1990s was a period of complex changes for the region’s residents. Socialism was seen by many as a period of greater financial security. The housing stock and existing public facilities were mainly built thanks to the mine operation, which the residents have not forgotten. Dilapidated buildings and infrastructure indicate how much a large enterprise (the mine) could finance and build “before the transformation”. On the other hand, the facilities abandoned by the industry, judging from conversations held with residents, have become synonymous with the consequences of poor management since the 1990s when mining restructuring began. Today’s leaders are determined to obtain funds for a “green” transformation. Still, at least in Brzeszcze, there is little consensus on allocating them [16]. There is agreement on one thing: areas and facilities deemed unnecessary (waste) should be utilised—through demolitions and the recovery of materials with market value (e.g., scraps) or adaptations—to attract new investors. In this context, reusing industrial heritage can be utilised as tangible proof of the possibilities of commercialising areas inspired by industry. The implementation of the principles of the circular economy and the Green Deal is understood by residents as an economic action, unlike the uneconomical restriction of industrial activity, which leads to waste generation. However, a problem that needs to be addressed in Brzeszcze is that for residents and authorities alike, demolitions and the possibility of quick monetisation of industrial heritage, which can be attributed to waste-like characteristics, are more desirable than their adaptations [16].

2.2. Two Cases of Areas Redundant for Mining in Brzeszcze

Further analysis concerns projects developed for Brzeszcze, a municipality replete with buildings, structures, and infrastructure abandoned by industry and waste generated from current mining operations. Of the areas that were the subject of in-depth studies, two were selected, one of which serves as a storage site for waste aggregates that have not yet found commercial application (“G” Flooded Land in Przecieszyn), and the other (Brzeszcze-East Hard Coal Mine (HCM)—a branch of the still-functioning mine (2024), excluded from exploitation in 1995. ”G” Flooded Land in Przecieszyn is a depression area formed as a result of underground coal mining and the closure of workings by the caving method, from which natural aggregates were subsequently extracted and ultimately selected for the storage of waste aggregates from the Brzeszcze mining plant. After the cessation of mining, the Brzeszcze-East HCM area was partially designated as a municipal waste storage site and an extractive waste facility (later subjected to re-exploitation). Part of the area was divided among private, small-scale investors. Most of the areas were left without assigned functional purposes. Within their boundaries lies an area covered by industrial heritage buildings, whose architectural-urbanistic value is highly regarded by experts (e.g., [17]). Nevertheless, these structures are gradually being dismantled (at times legally, at times unlawfully). Architectural-urban revitalisation concepts were developed between 2017 and 2021 for both areas (”G” Flooded Land and Brzeszcze-East HCM), involving the authors of the present article. The mining company commissioned the first project, while the city authorities commissioned the second. Both were prepared as operational ventures in the industrial and municipal transformation process.

2.3. Method: Research by Design for Mining Company and Municipality

The analysed design concepts aim to facilitate economic transformation and create tangible evidence of architectural-urban environmental changes. The initial proposals underwent discussion and assessment of implementation possibilities by investors and engineers’ interdisciplinary teams. The final shape of the projects is the result of negotiations. More than the final architectural forms (from the perspective of the considerations presented in this article), what deserves attention is the fact that research conducted through the “research by design” method [18] allowed for the determination of conditions and characteristic elements of solutions, deemed acceptable for the Polish transition to a circular economy and the Green Deal. Conversations with residents, authorities, and entrepreneurs conducted on-site and during online meetings, design discussions held during working meetings on project progress meetings, and investor opinions on transitional phases of the project (leading to the recognition of solutions as feasible or unfeasible for implementation)—provided valuable sources of information. Social research (AHP questionnaires, anonymous questionnaires, personal semi-structured telephone interviews, and discussion forums) was conducted in 2013, 2020, 2021–2022 (accordingly) and covered 140 people. Working with project drawings and expert opinions helped uncover the motivations and plans of the involved parties, which could remain hidden if meetings were not based on emerging documentation. The authors’ spatial-visual analyses of final solutions allow for verifying drawn conclusions. The three-year period between the development of the first and second concepts highlights the increasing tendency to recognise the role of the circular economy and greenery in mining exploitation planning. Today (2024), two years after the investors adopted the documentation, information about the further lot of these projects prompted us to analyse the realities of transformation in Poland, which can help analyse other locations around Europe with similar conditions.

3. “Green” Transformation of Polish Coal Mining—Current Experiences

The issue of sustainable transformation of Polish coal mining is extensively discussed in the literature. In 2019, the European Commission adopted a decarbonisation plan (European Green Deal), setting the pace for changes, the speed of which, due to a series of specific events (the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the war in Ukraine), became the subject of ongoing discussions again (e.g., [19]). Research indicates that among the groups shaping the discourse on transformation, the dominant ones are those interested in extending the period of transformation [20]. Directly interested parties, without questioning the necessity of transformation, attempt (effectively) to slow down its pace, gaining public opinion for this strategy (e.g., [21]). Researchers of Polish realities point out that mining companies support efforts toward sustainable development, and revenues from royalties can and are being used for their implementation. They conclude [22] that even designating new mining areas can facilitate transformation, understood as actions related to environmental protection and energy acquisition carried out concurrently with coal mining. It is argued that the slow pace of transformations and even planning new coal mines may fit into decarbonisation policy from a broader perspective. However, few studies address material actions in space that could contribute to achieving this compromise. Reports are limited to emphasising the role of spatial planning and protecting areas from development (e.g., [23]). Although tools for predicting spatial conflicts are undoubtedly becoming more advanced, e.g., thanks to the development of digital technologies [22], the principle of operation itself is based on a concept that has been implemented since the early 20th century in mining areas [24]. As mentioned earlier, the discourse on transformation is shaped today not only by the media. The fact that mining companies attempt to shape public opinion and media messages through material initiatives in space deserves examination.

It is well known that mining companies are active players striving to implement their land management strategies for post-mining areas. Negotiating reclamation conditions or changes and obtaining social licenses to operate and social licenses for closure require consensus building that combines sustainable development and profitable operations [25]. It is worth emphasising that the research indicates that mining companies can block or favour transformation directions in areas neighbouring mining activities that they consider unfavourable or indifferent to their core business [26]. There are reports that among space users, the prevailing belief is that fair transformation is unfair [27]. It is argued that negative social opinions are significantly influenced by the problem of the lack of creating a new identity and a new shared vision of the post-mining era—one that will not be based solely on technical innovations [27]. An overlooked research thread is the analysis of actions undertaken by mining facilities in spaces aimed at supporting core activities, combining economic and social needs—based on technical innovations attempting to create a new spatial identity.

Undoubtedly, industrial waste management (especially mining and extraction waste, as well as from energy production and supply) in Poland requires improvement, as a large portion of it is still disposed of through landfilling [28]. However, it is worth noting that the landscape values of mining heaps and flooded pits are not commonly questioned and are even treated as diversifying the appearance of the lowland environment of Poland (reflected, for example, in advertising campaigns by Polish non-renewable energy producers). The mining landscape, especially for small towns, represents the potential for shaping green and renewable energy areas and tourist products [29].

The article fills a research gap by highlighting initiatives combining social and economic needs. These initiatives can be implemented within (post)mining areas, aligning with the principles of the circular economy and the European Green Deal. They slow down the pace of transformation and shape the landscape through technical innovations that build identity.

4. Results: Research (of Mining Waste Areas) by (Landscape) Design

4.1. The Decommissioned “G” Flooded Land in Przecieszyn

In Poland, hard coal mining is accompanied by approximately 150 spoil heaps [30], which do not serve public functions. Some post-mining areas store waste of unknown origin and natural succession occurs in them. Greenery and diverse terrain divert attention from the negative aspects of industrial activities. For instance, the Matylda Spoil Heap in Chrzanów is a popular spot among young people for sports despite soil contamination and access prohibition.

Often, mining companies willingly transfer extensive open post-mining spaces to public entities as settlements or to avoid tax burdens. Contributing to the standard land bank, they can be considered valued resources in times of sprawling urbanisation and rising property prices. Increasing the standard bank of resources meets the needs of residents, especially after the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, when outdoor activities and access to open areas are valued by people more than before [31].

An example of such action is the project involving the decommissioning of the depression area and construction of a spoil heap in Przecieszyn (plot size c. 43 ha), 1.5 km from the operating Brzeszcze Mining Plant, which lacks space for depositing waste aggregates. Plans for storing unburned waste rock arose strictly from the company’s economic needs. The depression area in Przecieszyn was filled with material that had no market demand, reaching the level of the surrounding areas. In the second stage, the construction of an above-ground facility was planned at the exact location. The structure was estimated to accommodate 500,000 tons of waste aggregate and be built by 2040. By that time, the mining plant holds a concession for the extraction of thermal coal (currently, 45% of energy in Poland comes from coal, and its extraction is expected to continue until 2049 [32]).

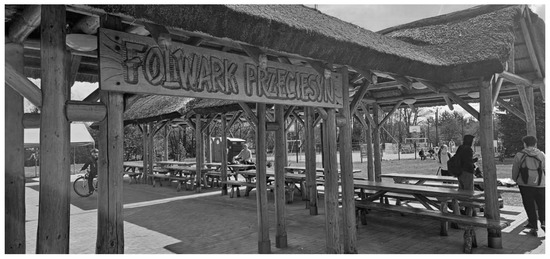

Numerous post-mining depression areas and flooded excavations (after the aggregate extraction) create recreational and sports potential for the Przecieszyn village, which has been closely associated with the mine for years. Despite its proximity, plans to allow an increase in the amount of waste aggregate deposited in the village, and industrialisation of the area (which has displaced agriculture), Przecieszyn strives to build its image as a traditional village, attached to folk building customs. Evidence of the effectiveness of these efforts is the distinction of Przecieszyn in the competition for the Most Beautiful Village in Małopolska in 2022. The leading argument for such an assessment was constructing a communal revelry place (Figure 3).

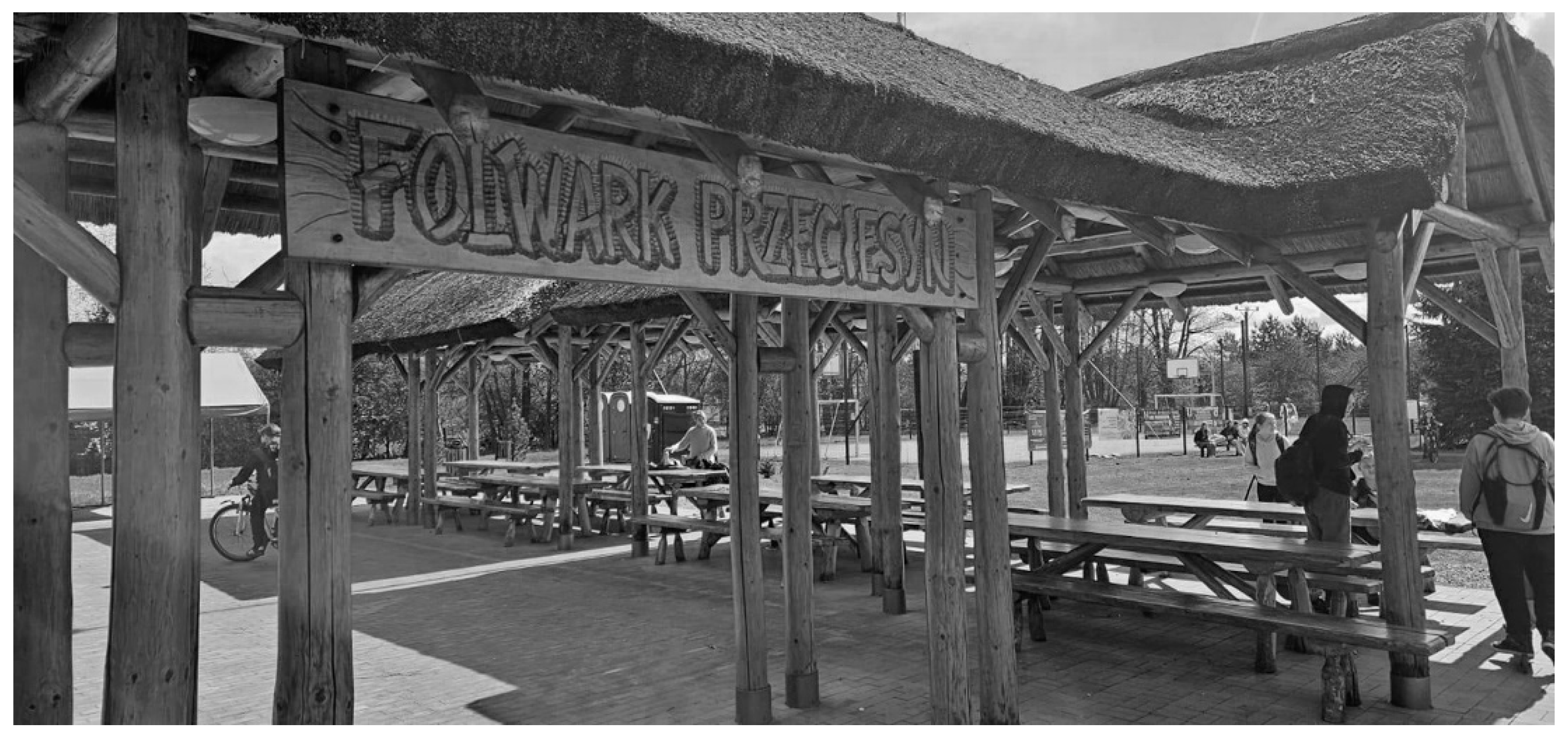

Figure 3.

An essential investment in Przecieszyn realised as part of the “Renewal and Development of Villages” program is Folwark Przecieszyn, whose form and building materials (wood and thatch) evoke popular imagery of folk architecture. The name of the place is an example of “mazurzenie” (a folk pronunciation phenomenon replacing the “sz” sound in the name of the locality with “s”) (we obtained photo permission from Żak Z., 2024).

Engaging in the development of the concept for the infrastructure facility (above-ground storage of surplus waste aggregates; ref. [33], a team of experts (AGH University of Krakow and 55Architekci architectural company) observed a tendency towards constructing landmark structures to signify Przecieszyn’s distancing from mining, through the creation of identity-shaping forms unrelated to it. In 2017, the Brzeszcze Mining Plant and municipal authorities agreed that the area affected by mining damages would be suitable for assuming the desired economic function. However, constructing the waste facility on the designated site would entail environmental fees for the mine. To mitigate the fiscal burden on the company, it was agreed that the municipality could take over the facility, even before its completion, if it served functions desired by the community (beyond economic ones). Consequently, it was established that the facility should be designed to serve as a public space from the initial stage of construction. Its location in mining areas served as evidence of the potential utilisation of the effects of current (and past) industrial activities and rational space management linking exploitation with revitalisation.

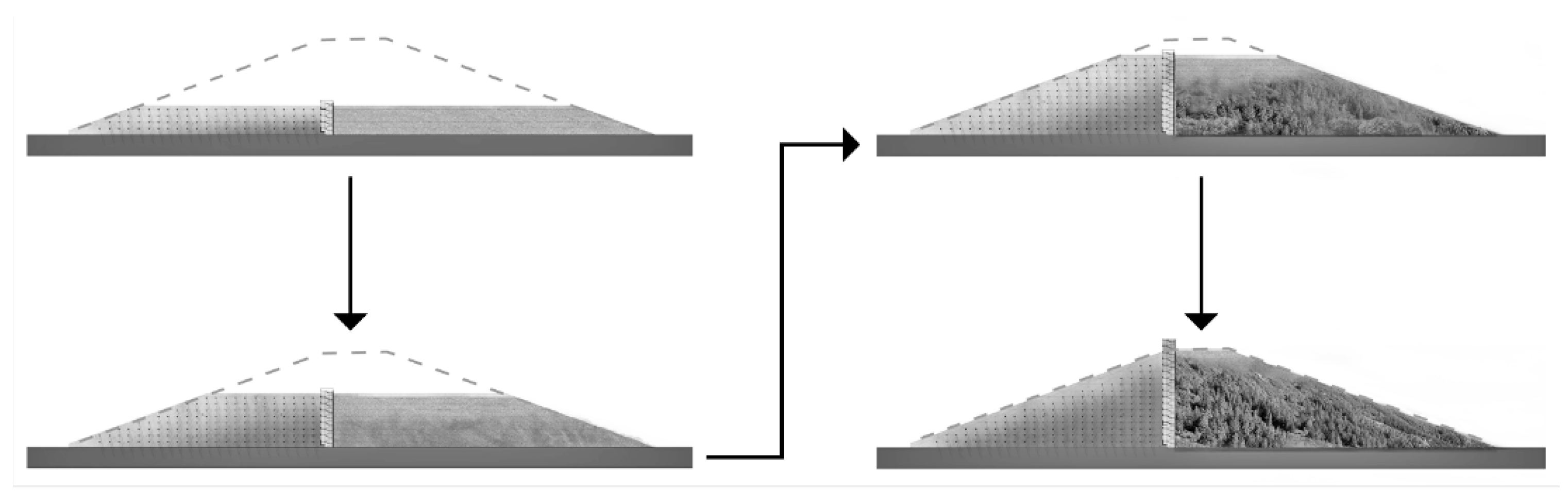

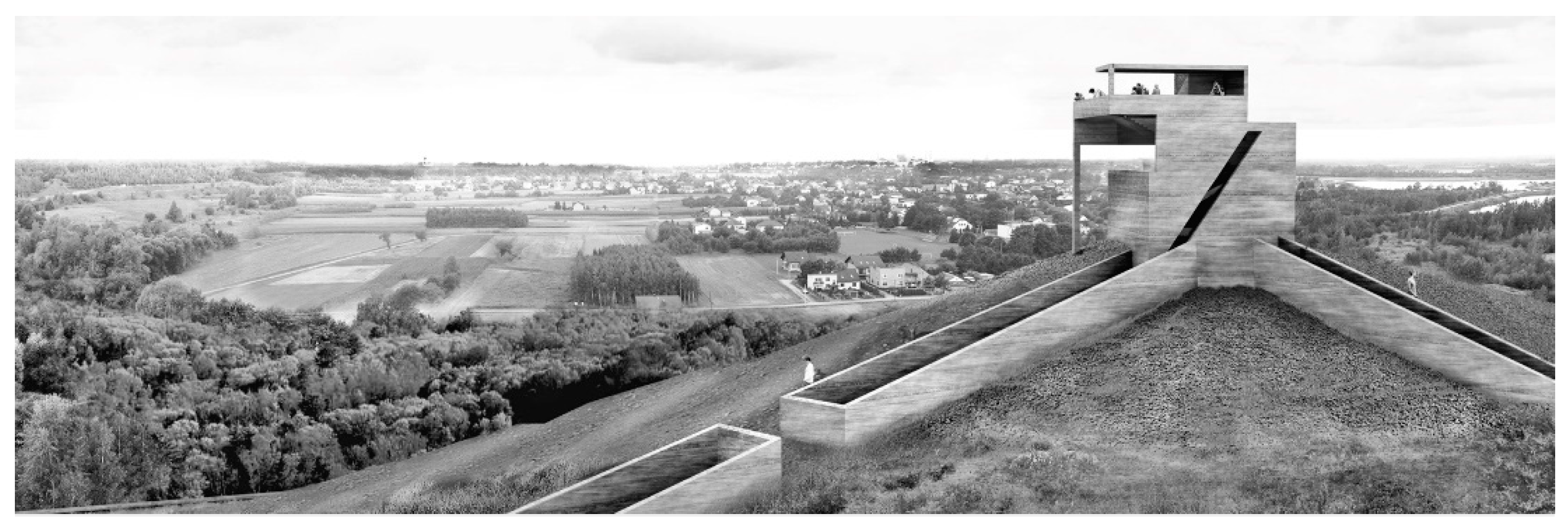

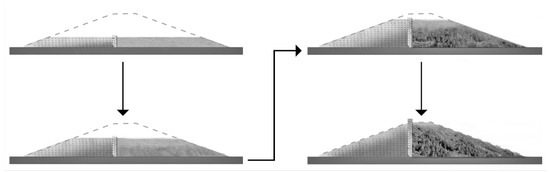

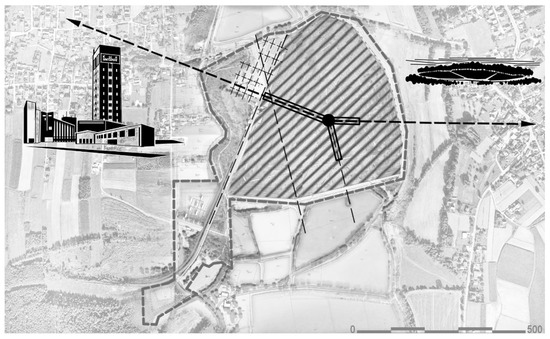

Initial design proposals for this area disguised the construction material, concealing it behind a greening project and a vision of numerous sports and recreational attractions on the site. However, this idea (costly and challenging to implement and maintain) was quickly abandoned in favour of a project that revealed the building material and transformation stages. It was assumed that “adits”, corridors incorporated into retaining walls leading into the interior of the “mountain”, would be incorporated into the technical infrastructure facility, implemented concurrently with the dumping of subsequent levels of the structure—allowing public access to the area. The central, expanding staircase, surpassing the summit of the mass at each stage, was designed to create a viewpoint (Figure 4). Due to natural ecological succession, the facility’s lower levels would become green faster than the higher parts, highlighting the technological process and the action of natural forces. By linking the form of the facility with the pace of filling the mass with waste aggregates, the coal market situation (influencing the number of surplus aggregates) would be reflected in the material form. Combining technical needs with the need to shape the place’s identity, the facility’s form was planned to emphasise the visibility of the building material of the mass and its compositional and visual connection with neighbouring industrial objects and industrial heritage (Figure 5 and Figure 6). The facility was designed by outlining the target form at the initial stage. Still, the construction method allows for flexibility in the erection process (without limiting the company or the possibilities of public use). The landscape object was planned to be constructed and gradually opened to the public in stages (the final relative height was planned as c. 150 m). The speed at which these stages would be realised and when the entirety would be completed was not specified. The aim was to ensure the attractiveness of the undertaking for both social and economic parties and to promote industrial activity as part of the local culture. The landscape form can be understood as a mediator that helps facilitate slowing down the process of transformation—in favour of the mining enterprise, as well as the community (by offering a vision of open public space created by the mining enterprise that the community can use as part of strategic piggybacking).

Figure 4.

The construction staging plan (we obtained drawing permission from 55Architekci, 2017).

Figure 5.

The facility’s form emphasises the character of its building material, giving it sports and recreational functions (we obtained drawing permission from 55Architekci, 2017).

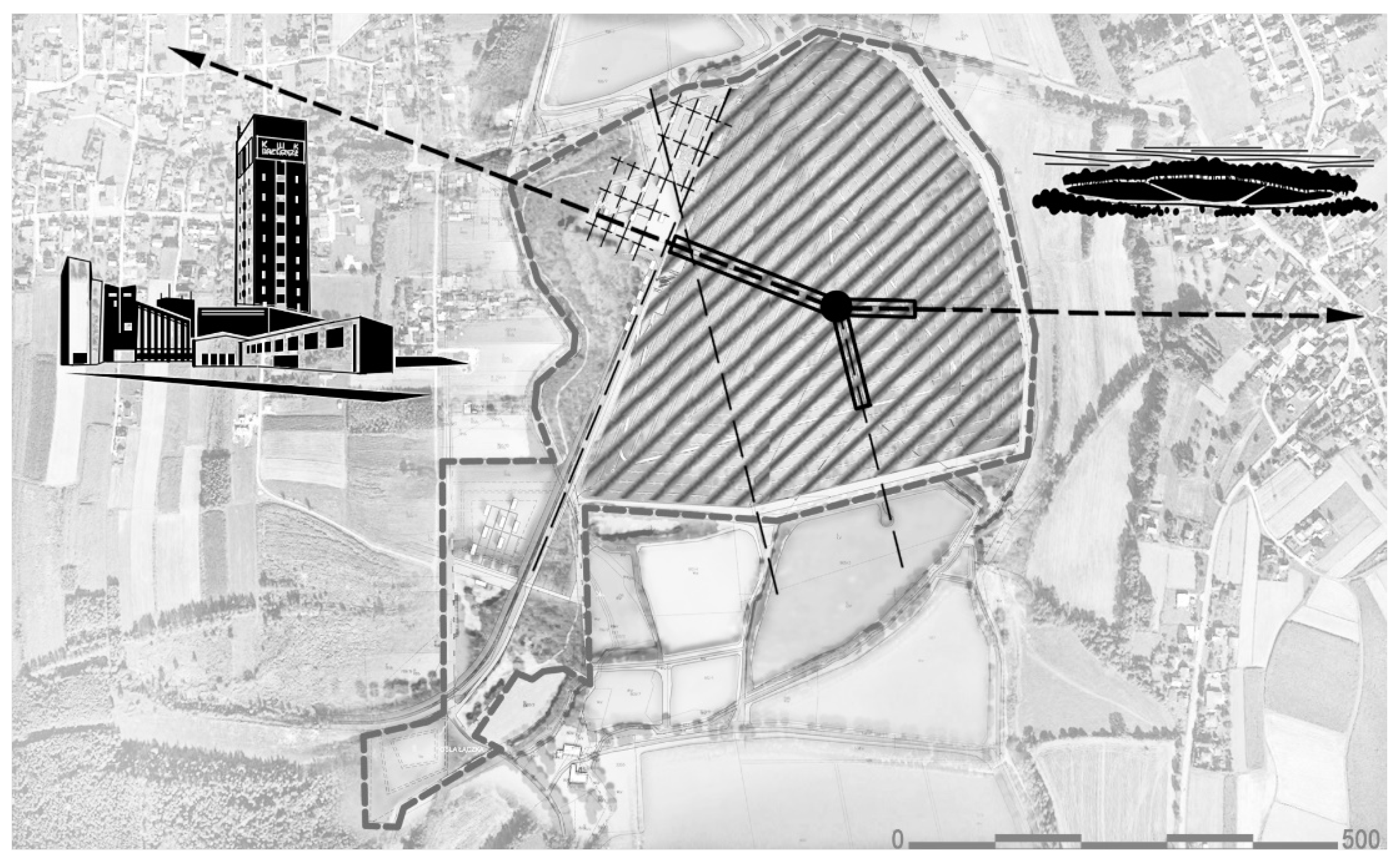

Figure 6.

“Adits” (rectangular outlines) anchored in a watchtower (dot) are surrounded by waste storage areas (hatched area). Architectural objects on the waste heap are visually (thick dashed lines) and compositionally (thin dashed lines) linked to post-industrial objects (e.g., post-mining reservoirs Skorzec—right icon) and industrial ones (Brzeszcze Mining Plant—left icon) (Szewczyk-Świątek A., 2024).

The above-ground facility was designed at the request of the Brzeszcze Mining Plant but was not realised. The local government approved the facility’s construction after reviewing the design proposals. Still, logistical problems related to transporting waste aggregates led to a change in the investment location to one not of interest to the community (storage within a flooded mine workings). Despite the lack of realisation of the project in the described form, the local government recognised the potential of a creative approach to the problem of using post-industrial areas—as industrial ones. As a result, the same team (previously working on behalf of the mining company) was commissioned to develop a programmatic-spatial concept for the area closed in 1995—the Brzeszcze-East HCM [34]. During the initial work, it became clear that the work was commissioned because officials saw a chance to implement projects that combine economic and social needs in mining areas—using funds to implement the European Green Deal and the Just Transition Fund.

4.2. Brzeszcze-East Hard Coal Mine

Defining the requirements for the revitalisation project of the inactive Brzeszcze-East HCM, the investor aimed for a flexible development plan that would attract new industrial investors to the municipality [34]. For the designers, it was essential to preserve the industrial heritage and to demonstrate that mining is part of the local culture, and the remnants of it (21 buildings and structures) should be renovated and adapted. Five buildings on the surface of the mine were included in the Regional Heritage Register, which theoretically made a strong argument for their conservation. Still, only two were conserved in their original form until now. For the local government nor the Mine Restructuring Company (Polish abbreviation SRK), which took over the area’s management after the mine’s closure, conserving the heritage was high on the priority list. At the last moment, the design team convinced the municipal council that conserving the structures and adapting them aligns with the principles of a circular economy and could facilitate obtaining EU funds for Brzeszcze. As a result, the municipal council decided to take over the areas occupied by the buildings from the SRK, and demolition projects were abandoned [35]. It can be seen as short-term proof of the effectiveness of planning spatial initiatives—the act of regaining agency and empowerment. Along with the acquisition of the buildings, land covering an area of over six hectares was also acquired from the entire area of the Brzeszcze-East HCM, covering approx. 86 hectares.

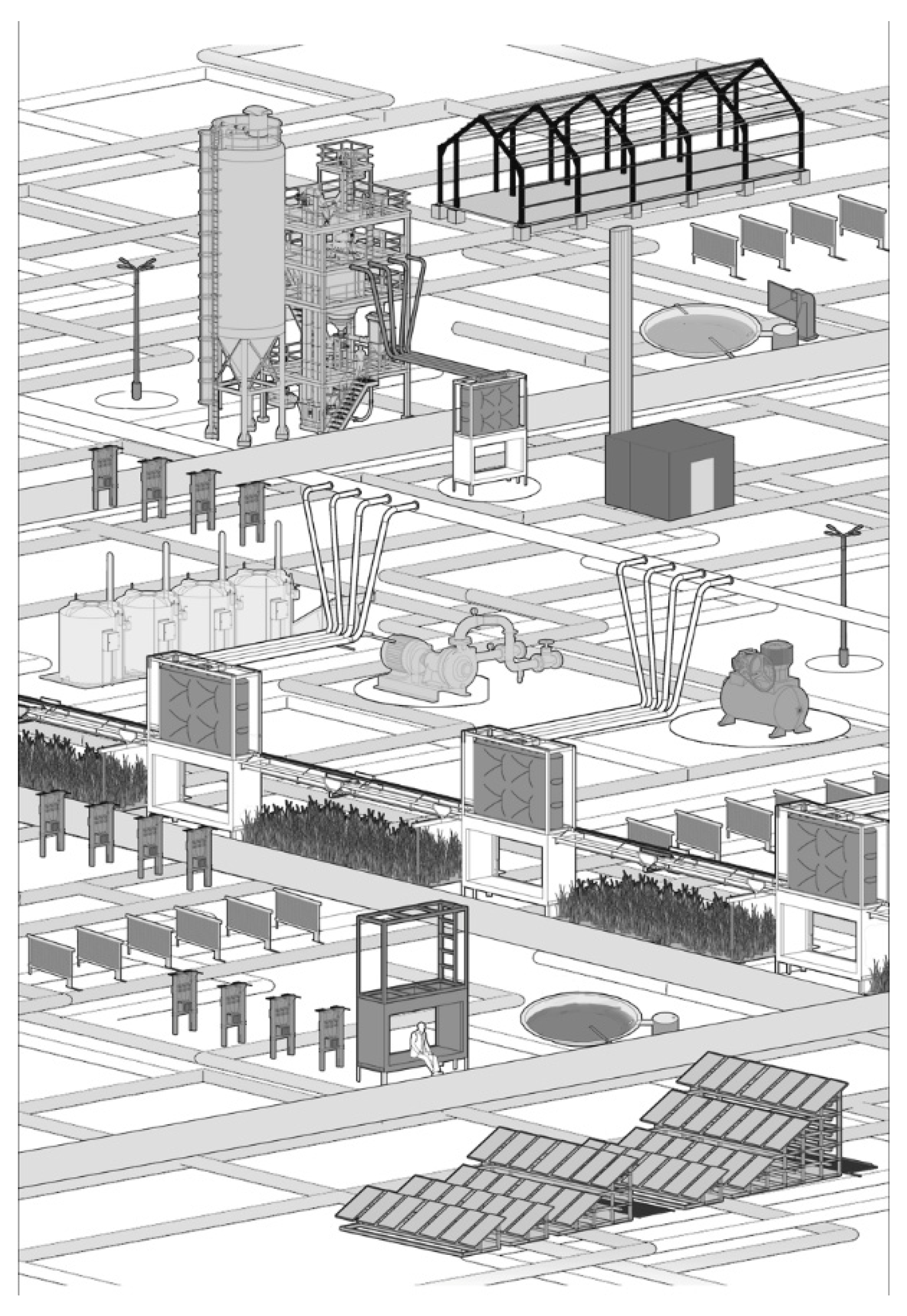

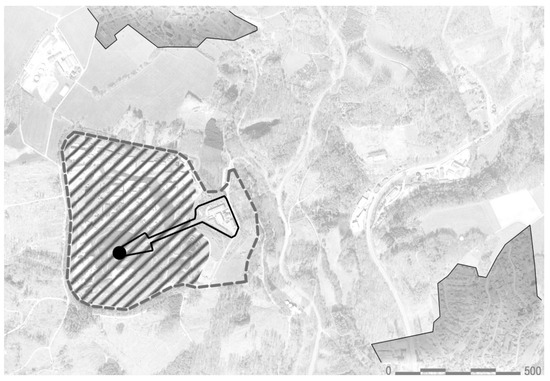

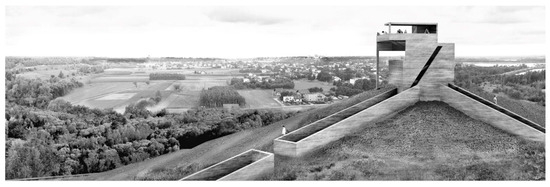

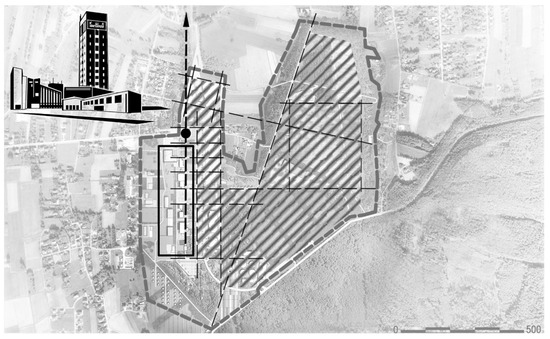

The programmatic-spatial concept covered the entire area of the Brzeszcze-East HCM. It included adaptations of surface mine facilities for service, commercial, and residential functions. Due to the topic discussed in this article, particular attention is paid to the proposal for using the part of the land not occupied by historical buildings, including undeveloped areas. Buffer storage—formerly considered non-buildable areas to avoid blocking the functioning of the mining plant, its transportation infrastructure, warehousing, reloading areas, and waste heaps—also represents essential traces of the activity there. Leaving undeveloped areas of such significant parameters resulted in sacrificing them for the possibility of industrial activity, but their image is not characteristic of the residents. Popular conviction is that there is nothing there (which was severally repeated in interviews). Currently degraded, uninhabited, unincorporated into the urban structure, housing a landfill and municipal waste sorting facility, this area lacks characteristic landmarks yet is changing through spontaneous natural succession. In the transformation project, these waste-filled areas, hidden behind heritage structures made of red, unpainted brick, are planned to be publicly accessible before they are fully restored before the presence of waste is hidden under overgrown greenery. Minimal architectural interventions were intended to define the available spaces, those not planned to be fully repaired yet (where investment from the renewable energy production, recovery, processing, and waste storage industry is desired). In other words, a circular landscape was planned (Figure 7), and the most characteristic elements in the environment’s appearance are waste deposition and processing sites, industry-abandoned structures adapted with the preservation of entropy traces, and phytoremediation plantings, as well as facilities for renewable energy production.

Figure 7.

Emphasising the visibility of industrial heritage, waste, and active industrial facilities has inspired the creation of an urban grid (dashed lines) defining the appearance of the environment responding to the Green Deal policy guidelines—a circular landscape at the site of the inactive Brzeszcze-East HCM. Beyond the belt delineated by historical buildings (rectangular outline) and the new methane cogeneration installation (black dot), circular industrial areas (processing, recovery, and waste storage, renewable energy production—hatched area) were designed (Szewczyk-Świątek A., 2024).

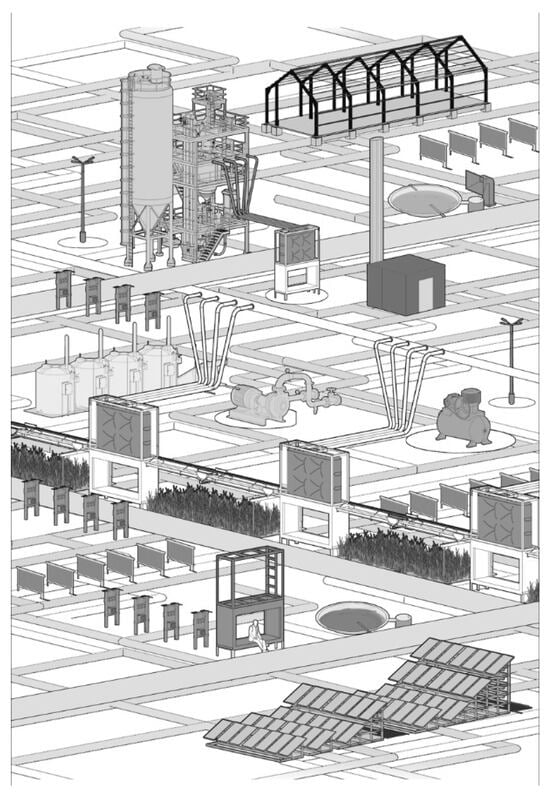

Similarly to the project for the ”G” Flooded Land in Przecieszyn, in Brzeszcze-East HCM, industrial facilities (both old and new industry) in the vicinity were highlighted by the urban grid as necessary for the area’s identity. During the work, a “toolbox” (Figure 8) with elements of installations (pipelines, intakes, rainwater tanks, boilers, biofuel silos, pumps, compressors, transformers, capacitors, collectors, etc.) was created, which could be used to delineate the designed urban grid in the terrain and ensure the creation of public spaces adjacent to circular industrial areas, allowing access to them. These were the only elements the design team considered feasible for implementation at the preliminary stage of transformation, along with those whose construction is possible with public funds. Furthermore, their implementation does not require the municipality to agree with a specific investor or define the eventual land use. The city considered these arguments sufficient to accept this course of action. When designing the “toolbox”, efforts were made to give the installation elements an attractive appearance of forms, as they could promote public and recreational use of the terrain—pipelines were assigned a colour code, rainwater tanks were connected to resting places, photovoltaic panels can serve as rain covers, etc. Attention was paid to the solution’s aesthetics, and efforts were made to combine landscape design with circular economy signs.

Figure 8.

Toolbox of installation forms that can help define the urban grid (we obtained drawing permission from 55Architekci, 2021).

The project introduces investments from the waste management sector into the mining area, but is this a project aiming to move away from mining? Instead of planning to move away from mining, the project aimed to consider the uncertainty regarding the direction and pace of Brzeszcze’s transformation. The goal was to create material frameworks organising the landscape rather than striving for a final image of the environment. Within these frameworks, areas were designated for investors in waste management (the only ones seemingly interested in this area), and spaces were reserved for investments requiring continuing coal seam exploitation. A prime example illustrating this approach is the inclusion of a methane cogeneration installation, carried out in the northern part of the area by a mining company, as one of the essential undertakings of the project. This installation, completed in 2021, is located at the visual termination of the main access road to the historical part of the Brzeszcze-East Coal Mine complex, by the most valuable building in the area listed in the monument registry (the Andrzej III headframe building). The installation allows for methane recovery, which is a waste product, and its functioning and economic viability are tied to the need for continued mining activity. By designing new communication and public green areas adjacent to the installation (connecting it with the heritage site), the potential for synergistic functioning of old and new industries, historic buildings, and modern facilities is promoted. Similarly, when planning a photovoltaic farm on a re-exploited spoil heap, it was “cut” by public recreational and sports areas (e.g., pump tracks, bike paths, and running trails). Phytoenergic crops enabling land reclamation and energy production were combined with commercial and social spaces. The plasma waste disposal facility (including mining waste) and upcycling centre were surrounded by services, climbing facilities, and viewpoints. These actions attempt to break stereotypes and negative perceptions of areas associated with heavy industry, waste, and energy production. Since the project has not yet been realised, it is difficult to determine whether this goal will be achieved. At this stage, the possibility of integrating objects related to active mining activity and those associated with the circular economy into a common spatial framework at the preliminary stage of transformation is clear. The concept combines the need for a gradual transition from mining and the possibility of obtaining funding from sources for heavy industry transformation. It thus differs from transformation concepts implemented in places like the German Ruhr Area, where transformation occurs without the active involvement of coal mining companies.

5. Discussion: Circular Transformation of Mining—Not an Obvious Task

5.1. Project Design and after

An interdisciplinary team of specialists and stakeholders consulted both previously described projects. The clients thoroughly analysed both forms, consulted, and deemed them implementable. The project development for Przecieszyn lasted five months, during which three meetings with representatives of the mine took place, followed by discussions with the local government. The Brzeszcze-East HCM project, which emerged as an extension of the research conducted in Przecieszyn, can be seen as an expression of a broader tendency towards more significant consideration of waste management in areas related to mining. It required 14 months of work, during which interviews with residents were additionally conducted. The concept was consulted several times informally, with two consultations of the project being organised as part of online meetings of the City Council. After completing the design phase, the designers were asked to consult changes to the Local Land Use Plan and proposals for changes to the transportation layout—as declared by local government representatives—to ensure their alignment with the concept. The official transfer of the Brzeszcze-East HCM areas from the Mines Restructuring Company to the Brzeszcze municipality occurred in June 2022. On this occasion, the mayor of Brzeszcze stated: “We are making every effort to prepare the municipality to access support under the European Just Transition Fund. Signing the donation transfer agreement is another step bringing us closer to the comprehensive revitalisation of the former Brzeszcze-East HCM areas, considering the principles of the circular economy and climate neutrality” [36]. However, neither of the projects has been realised yet. Since the acquisition of the land, little has been done to implement any element of the revitalisation project. There is still (in 2024) the only one initiative in this area that can be considered in line with the principles of the Green Deal and circular economy (methane cogeneration installation), which, as previously mentioned, does not limit coal exploitation but instead assumes its maintenance. The Nearby Places of Memory Foundation (which commemorates the work of prisoners in the Nazi labour camp in the mine during World War II), already interested in these areas, has taken the historical buildings under its care, initiating their initial securing and organising of equipment. The remaining plots remain undeveloped. Some conclusions can be drawn from the conducted research by design.

5.2. Mining in the Initial Stage of Circular Transition

The circular economy policy is a crucial reference point for the mining company and the Brzeszcze municipality. Stakeholders declare their willingness to implement EU guidelines. Still, at the same time, they have not undertaken (and probably will not undertake) tangible investments until the funds from the Just Transition Fund (JTF) are transferred to them. Previous studies indicate that after receiving a financial boost, the most excellent chances of implementation lie with those initiatives that align with the principles of circular economy and enable a gradual transition away from mining—these are considered feasible. Local authorities see them as an opportunity to obtain funding for functional diversification. On the other hand, the mine sees them as actions that, without burdening the enterprise’s budget, will allow for shaping positive community relations towards ongoing exploitation and reducing the burdens associated with the need for sustainable waste management. The circular economy policy is treated and promoted among the community as an opportunity to address local economic issues at a supra-local level. The desire to slow down the pace of transformation goes hand in hand with avoiding tangible actions by both sides until decisions at higher levels of authority are made (and funds for their implementation are released). The municipality’s acquisition of the land and the lack of actions that would definitively define their purpose are deemed sufficient by the community as long as funds are lacking. The primary goal is not to redevelop the areas but to obtain funds for this purpose (as evidenced by the mayor’s quoted words). All visions, projects, and plans are developed. Still, the aim is not to make them binding but to “bring us closer to comprehensive revitalisation” [36]. Although negotiating the understanding of the concept of “comprehensive revitalisation” has only begun, it can be assumed that releasing funds from the JTF will give it momentum and encourage binding determination of directions. The study has shown that the supra-local policy and the objectives for which financial resources from the JTF will be allocated are crucial for the forms of space considered feasible by the Brzeszcze mining enterprise and the local government. Initiatives enabling the resolution of current exploitation problems (such as depositing waste aggregates and emission reduction) allow for its continuation and demonstrate that actions in line with the closed-loop economy are most desirable.

5.3. Aesthetic of Circular Environment

The transformation vision, aimed at aiding in the efforts to secure EU funding and meeting stakeholders’ expectations, included, in addition to functional guidelines, determinations regarding the environment’s appearance. The final images and descriptions of the concept resulting from month-long consultations indicate that the initial decision to refrain from deliberately concealing the presence of waste was maintained. Waste processing facilities were identified as critical investments, with landfills and spoil heaps serving as facilities enabling the functioning of new installations. The nature of extensive green areas—ruderal, successional, bioenergetic, and phytoremediative—underscores that the area is a consequence of mining activity, with waste being present and not constantly subjected to remediation (though gradually obscured by vegetation over time).

During the work, it was observed that investors interested in expanding business activities in Brzeszcze are primarily interested in waste collection and processing in mining areas (both the mining company itself and external investors). The municipality was willing to grant permissions to operate to these companies, but it was noted that community opposition to this industry discouraged investors. Opposition to the development of the waste sector was not diminished by the fact that the areas within the orbit of interested firms are mining areas—degraded ones where waste had already been managed. The decommissioned flooded land in Przecieszyn, like Brzeszcze-East HCM, are areas where extractive waste and waste aggregates, and even municipal waste (on the premises of Brzeszcze-East HCM), were stored openly and with public consent.

It was decided that Brzeszcze, wishing to develop the mining legacy, “will stick with waste,” which will gradually be transformed into areas for renewable energy production and recreational regions, promoting the desired image of these industries. The planned landscape was, therefore, meant to emphasise the presence of waste and the potential for using waste-related areas rather than concealing them. To achieve this goal, it was planned that key features shaping the physiognomy should be those related to waste management. It was also anticipated that new waste would be deposited (or processed) within the designated areas, and the landscape would be defined by characteristic forms, which, thanks to external funds, would not only be utilitarian but also representative of the circular economy. It is worth emphasising that such an assumption potentially increases the total amount of waste in a given area. Overgrown and greened areas (successional, phytoremediative, and economic greenery) play a unique role in such a scenario—improving the environment and the quality of life for residents, despite the potential increase in environmental burden.

Circular infrastructure facilities were planned to be prominently featured in the landscape, as well as active mining facilities and historic mining sites. Promoting them as elements of local technical culture, which can (and should) be a source of pride for residents, can be seen as an attempt to maintain the tradition of the industrial town and as a way to manage community opinions. Material forms in space can become tools for setting norms for thinking—determining what can be thought of and what forms and functions of the environment can be accepted. Currently, what has been received by the community is an attempt to expand on themes important to local identity, primarily mining-related ones, with initiatives combining mining with waste management.

5.4. Pseudo-Circular Economy in Mining Areas

To provide a comprehensive picture of the changes in Brzeszcze, it is necessary to mention an event during the project work on redeveloping the Brzeszcze-East HCM area into a circular economy hub. What happened before the municipality took over the lands from the Mine Restructuring Company indicates the need for a broader discussion regarding the nuances of understanding transformation goals and perceptions of waste issues in mining (and industrial) areas. Under the guise of increasing the attractiveness of the post-industrial area for investors, actions were taken at the Brzeszcze-East HCM site to dismantle the unused railway tracks for scrap metal. Despite protests from the project team and arguments about the merits of the railway, including its historical and touristic value and role in industrial development possibilities, it could not be saved. Local authorities and the Mine Restructuring Company were fully aligned in favour of demolition, which was promptly executed.

This event warrants criticism, highlighting how waste management practices can easily undermine cultural efforts. It raises questions about how projects like those examined in this article can serve a pseudo-waste management agenda and whether architectural frameworks inadvertently facilitate this. The question of how the rapid phasing out of mining can serve a pseudo-waste management agenda, with political decisions setting the pace, is equally important. This event underscores how redundant assets for mining companies are readily seen as possible to be monetised under the guise of efficiency.

6. Conclusions: Local Idea of Combining Waste, Circular Economy and Mining

- Architectural design of mining-related areas is a tool for testing the effectiveness of solutions for exercising power over the public perceptions of these areas.In the context of the European Green Deal and the circular economy, creating architectural frameworks, plans for constructing facilities, and recreational infrastructure in mining-related areas may seem insignificant. However, the deliberate emphasis on the visibility and purposefulness of building objects related to mining on par with waste management facilities in the project is not coincidental. This action is intended to draw attention to space as a medium for communicating specific messages, mediating social conflicts, and enabling architectural actions to test decisions at the initial stage of transformation in every place. The mining infrastructure and obsolete mining buildings can be used to disseminate representative images of circular economy landscapes.

- Transforming degraded land into public spaces can be a tool for manipulation.Green areas, installations, infrastructure objects, pump trucks, climbing spots, and recreational paths symbolise change. Still, scepticism arises from the observation that degraded, non-building, waste-filled areas, previously unattractive to investors, are now willingly visualised as public spaces. From the presented research, it can be concluded that exposing waste is characteristic of circular landscapes and can be designed in other countries (even in those not very affluent). However, determining whether these are examples of a broader tendency requires further study. It is also unknown whether highlighting waste in the designed landscape will be an effective persuasive action for communities to agree to the location of waste management facilities in their areas. Does transparent development and securing public insight into industrial and waste areas offer the chance that post-heavy industry areas will provide better living conditions and be more resilient? The :metabolon waste facility described in the introduction offers hope for a positive answer to this question. This waste hub gained acceptance from the local community shortly after its implementation.

- Paradoxically, mining waste can be used to raise EU funds for transformation, slowing the pace of change.So far, circular economy projects have been planned as replacements for coal mining. The research indicates that advocating for rapidly transforming mining areas into circular economy zones may be problematic. The cases from Brzeszcze demonstrate a local strategy for creating solutions with the ambition to influence political decisions. Combining transformation and circular economy with mining has gained project representation in this mining town. However, it has not yet reached a spatial realisation. Applying for EU funds requires lobbying for the project. The competitive mode encourages demonstrating that the adopted solutions offer a chance for policy-compliant, optimal use of funds for which the entity is applying. By seeking to align with the guidelines of the European Green Deal policy, Brzeszcze uses waste to raise awareness of the gradual, slower transition away from mining—at the European level—where it is in Poland’s interest (and in countries in similar economic situations) to have this issue discussed more prominently.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.-Ś.; methodology, A.S.-Ś.; validation, A.S.-Ś. and A.O.; formal analysis, A.S.-Ś. and A.O.; investigation, A.S.-Ś. and A.O.; resources, A.S.-Ś., A.O., M.C. and P.B-V.; data curation, A.O. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.-Ś.; writing—review and editing, A.O., M.C. and P.B.-V.; visualisation, A.S.-Ś.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, A.O., funding acquisition, M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Initiative for Excellence—Research University under the university grant “Models of transition to a climate-neutral, circular economy for mining regions in transformation”. Project contract number: 501.696.7995.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

References

- Act of 14 December 2012 on Waste, J.L. 2013, Item 21, with Amendment. (In Polish). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20130000021/T/D20130021L.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- National Recovery and Resilience Plan, 2022, Warsaw. (In Polish). Available online: https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/media/109762/KPO.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 11 May 2015 on Recovery of Waste Outside Installations and Devices, J.L. 2015, item 796 (in Polish). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20150000796/O/D20150796.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Environmental Protection 2019. Statistical Analyses. Warsaw: Central Statistical Office (in Polish). Available online: http://stat.gov.pl (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Wille, E.; Sinnett, D.; Baranyi, G.; Braubach, M.; Netanyahu, S. Protecting Health through Urban Redevelopment of Contaminated Sites: Planning Brief. World Health Organisation Regional Office for Europe, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289056342 (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- ICLEI. Resilient Cities, Thriving Cities: The Evolution of Urban Resilience. 2019. Available online: https://e-lib.iclei.org/publications/Resilient-Cities-Thriving-Cities_The-Evolution-of-Urban-Resilience.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- The Rockefeller Foundation, Arup. City Resilience Framework. 2014. Available online: https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/city-resilience-framework/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Solả-Morales, R.I. Terrain Vague. In Anyplace; Davidson, C., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen, B. Revisiting liminality. The danger of empty space. In Liminal landscapes: Travel, Experience and Spaces in Between; Adrews, H., Roberts, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 21–35. [Google Scholar]

- European Circular Economy Stakeholder Platform: Metabolon—Climb a Landfill and Enjoy a Circular Experience. 2019. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/education/metabolon-climb-landfill-and-enjoy-circular-experience (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Bongards, M. Zirkuläre Wertschöpfung in bewegten Zeiten. In Kompendium der Forschungsgemeinschaft: Metabolon 2015–2018; Ley, N., Ed.; TU Köln: Köln, Germany, 2018; pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rossmann, A. Exclamation Points of Structural Change to Be Seen and To See: The Landmarks of the Ruhr Area. In Tiger & Turtle—Magic Mountain: A Landmark in Duisburg by Heike Mutter and Ulrich Genth; Dinkla, S., Greulich, P., Janssen, K., Eds.; Hatje Cantz: Duisburg, Germany, 2012; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Ganser, K. Eine Baustellungim in hübsch-hässlicher Umgebung. Forum Ind. Geschichtskultur 2009, 1, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wackerl, W.; (Elsdorf, Germany). Personal communication, 2015.

- Turnau, K.; Mleczko, P.; Blaudez, D.; Chalot, M.; Botton, B. Heavy metal blinding properties of Pinus sylvestris mycorhizas drom industrial wastes. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2002, 3, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Cała, M.; Szewczyk-Swiątek, A.; Ostręga, A. Challenges of Coal Mining Regions and Municipalities in the Face of Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenartowicz, J.K. The Potential of the State-Owned Jawiszowice Hard Coal Mine as a Heritage of Technology and a Strategic Hub of Intervention in the Brzeszcze Municipality: Preliminary Considerations for the Revitalization Project. Czas. Tech. 2011, 108, 49–58. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Frayling, C. Research in Art and Design. R. Coll. Arts Pap. 2014, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M. Challenges of the Polish coal mining industry on its way to innovative and sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 375, 134061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywda, J.; Krzywda, D.; Androniceanu, A. Managing the Energy Transition through Discourse. The Case of Poland. Energie 2021, 14, 6471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielemann, N.; Berrocal, M. Framing the Energy Transition: The Case of Poland’s Turów Lignite Mine. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2024, 18, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pactwa, K.; Woźniak, J.; Strempski, A. Sustainable mining—Challenge of Polish mines. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasztelewicz, Z.; Ptak, M. Selected problems of securing brown coal deposits in Poland for opencast mining activity. Polityka Energetyczna 2009, 12, 263–276. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, R. Denkschrift Betreffend Grundsätze zur Aufstellung eines General-Siedelungsplanes für den Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf (Rechtsrheinisch); Fredebeul & Koenen: Essen, Germany, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska-Woszczycka, A.; Pactwa, K. Social License for Closure—A Participatory Approach to the Management of the Mine Closure Process. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk-Światek, A. Architecture and Active Heavy Industry: On Initiatives Influencing the Social Perception of Industry in Light of German and Polish Experiences with the Revitalization of Mining-Related Areas. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Cracow Technical University, Krakow, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resources/47693 (accessed on 18 August 2024). (In Polish).

- Schuster, A.; Zoll, M.; Otto, I.M.; Stölzel, F. The unjust just transition? Exploring different dimensions of justice in the lignite regions of Lusatia, Eastern Greater Poland, and Gorj. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2023, 104, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOZ Road Map (in Polish). 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj-technologia/rada-ministrow-przyjela-projekt-mapy-drogowej-goz (accessed on 11 March 2024).

- Marot, N.; Harfst, J. Post-mining landscapes and their endogenous development potential for small- and medium-sized towns: Examples from Central Europe. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łączny, J.; Bondaruk, J.; Janik, A. (Eds.) The Issue of Restoring Areas of Coal Waste Heaps to Socio-Economic Circulation; GIG: Katowice, Poland, 2012; pp. 13–32. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kercher, V.K.; Kercher, K.; Levy, P.; Trevor Bennion, T. Fitness Trends from Around the Globe. ACSM’s Health Fit. J. 2022, 26, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusidło, M. Energy Transformation in Poland (in Polish). 2023. Available online: https://www.cire.pl/files/portal/186/news/332418/d6e83ec558e69cc4c8e518a9e4f79696c49daf9e7de2b152793fcc65d24ce4d7.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Ostręga, A.; Szewczyk-Świątek, A.; Świątek, W.; Caban, M.; Jańczy, L.; Pawełczyk, K. Concept for the Development of the “G" Waste Heap along with a Connector to a Public Utility Facility; AGH University of Science of Technology: Kraków, Poland, 2017; Unpublished work. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ostręga, A.; Szewczyk-Świątek, A.; Świątek, W.; Caban, M. Concept of Revitalising the Decommisioned Brzeszcze-East HCM in Brzeszcze, Considering the Transition to a Climate-Neutral Circular Economy; AGH University of Science and Technology: Kraków, Poland, 2021; Unpublished work. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Resolution No. XXX/306/2021 of the Municipal Council in Brzeszcze (in Polish). 2021. Available online: https://prawomiejscowe.pl/urzadgminywbrzeszczach/document/741249/uchwala-xxx_306_2021 (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Press Office of the Malopolska Voivodeship Marshal’s Office. Another Step towards the Revitalization of Post-Mining Areas in Brzeszcze (in Polish). 2022. Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/aktualnosci/srodowisko/kolejny-krok-na-drodze-do-rewitalizacji-terenow-pogorniczych-w-brzeszczach? (accessed on 25 April 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).