Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels drive the rising phase of the action potential, essential for electrical signalling in nerves and muscles. The Nav channel α-subunit contains the ion-selective pore. In the cardiomyocyte, Nav1.5 is the main Nav channel α-subunit isoform, with a smaller expression of neuronal Nav channels. Four distinct regulatory β-subunits (β1–4) bind to the Nav channel α-subunits. Previous work has emphasised the β-subunits as direct Nav channel gating modulators. However, there is now increasing appreciation of additional roles played by these subunits. In this review, we focus on β-subunits as homophilic and heterophilic cell-adhesion molecules and the implications for cardiomyocyte function. Based on recent cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) data, we suggest that the β-subunits interact with Nav1.5 in a different way from their binding to other Nav channel isoforms. We believe this feature may facilitate trans-cell-adhesion between β1-associated Nav1.5 subunits on the intercalated disc and promote ephaptic conduction between cardiomyocytes.

1. Introduction

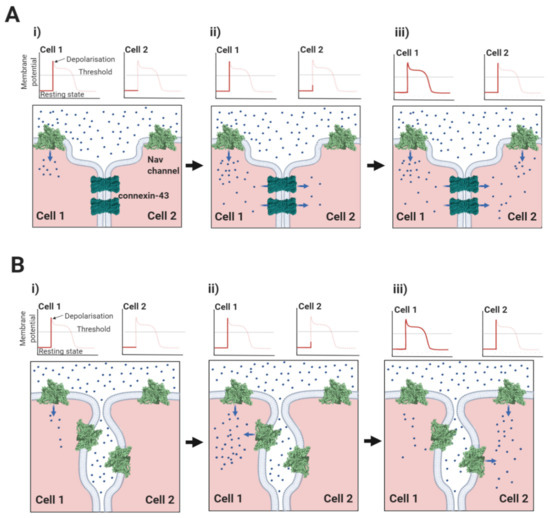

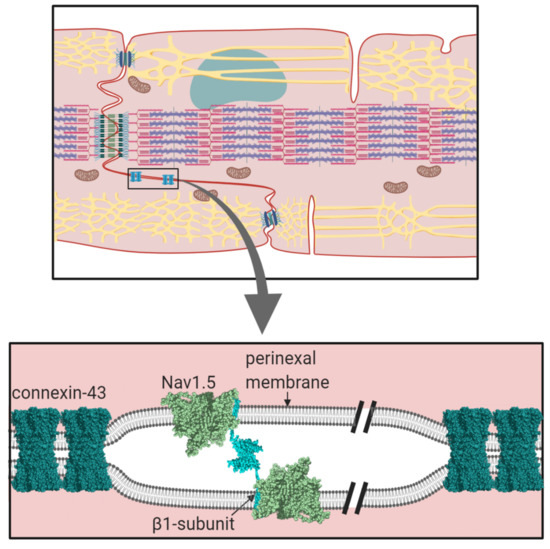

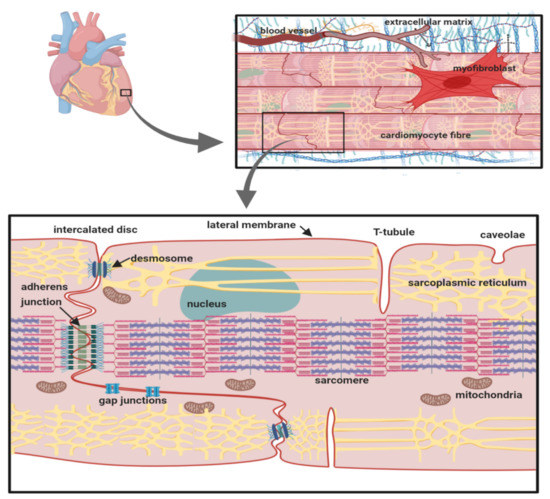

Cardiomyocytes within cardiac muscle bundles perform the involuntary contraction and relaxation cycle that is the cellular basis of the heartbeat. Cardiomyocytes possess unique adaptations to ensure this process is tightly synchronised between individual cells. In particular, the cardiomyocytes are both physically and electrically connected to each other via their intercalated discs. On the lateral membrane, T-tubules facilitate the transmission of the electrical signal from the cell surface, to deeper within the cell. This stimulates the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the initiation of sarcomere contraction (Figure 1) [1].

Figure 1.

The cardiomyocyte: its anatomical and cellular context. The location of key organelles, membrane compartments and molecular components mentioned in the text are indicated.

The cardiac action potential underlies electrical signalling and is initiated by the transient depolarisation of voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels (for further details, see Ref. [2], this volume). The Nav channel α-subunit (Mwt ~220–250 kDa) contains the ion-selective pore. In the human genome, there are nine different functional Nav channel α-subunit genes encoding proteins Nav1.1-1.9. Different Nav channel α-subunit isoforms are expressed in a tissue-specific manner and exhibit distinct gating behaviour, presumably tailored to their physiological context. In the cardiomyocyte, Nav channels with different gating properties can also be correlated with their differing sub-cellular localisation. The major Nav channel isoform expressed in the heart is Nav1.5. It is mainly localised at the intercalated disc and within caveolae on the sarcolemmal lateral membrane [3]. Cardiomyocytes also express smaller amounts of the neuronal channels Nav1.1, Nav1.3 and Nav1.6, which are predominantly localised in the T-tubules [4,5]. This pattern is striking and is likely to be functionally significant. For example, on a given cardiomyocyte, all Nav channels will experience the same resting potential. However, Nav1.5 activates at more negative potentials and more slowly compared to neuronal Nav channels. Thus, Nav1.5 at the intercalated disc and on the sarcolemma may initiate the cardiac action potential as it propagates from one cardiomyocyte to another within the muscle fibre [5,6]. By contrast, a delayed T-tubular excitation of the neuronal Nav channels will be matched by their more negative threshold for excitation and the more rapid kinetics of activation. This, combined with the close structural association between the neuronal Nav channels, the sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) and the voltage-gated calcium channels on the T-tubular membrane and with the ryanodine receptors (RyR) on the adjacent sarcoplasmic reticulum, permits T-tubular activation that is synchronous with the surface action potential and that optimally initiates excitation-contraction coupling [4,7].

1.1. The Nav Channel α-Subunit

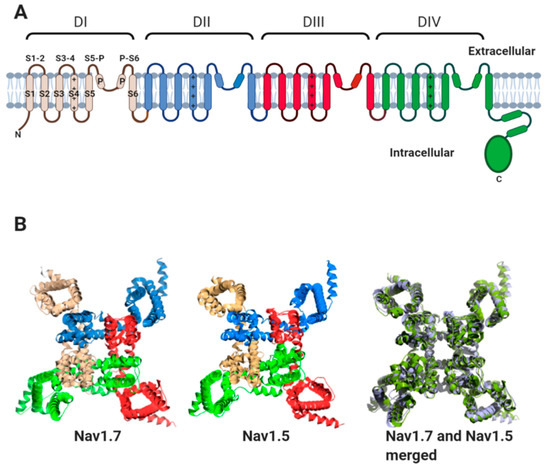

All Nav channel α-subunits contain four internally homologous domains (DI-IV). Each domain contains six transmembrane alpha helices (S1–S6) (Figure 2A). Helix S4 of each domain contains positively charged amino acid residues along one face of the helix. The movement of the S4 helices in response to changes in membrane potential is transmitted to helices S5 and S6 of each domain. This leads to the transient opening and subsequent inactivation of the channel pore [8,9]. High-resolution structures obtained by cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), for the heart-specific Nav1.5 α-subunit, the skeletal muscle channel Nav1.4 and the neuronal channels Nav1.2 and Nav1.7 show that the four domains surround the central pore with four-fold pseudosymmetry. Helices S1–S4 lie on the outer rim of the channel, with helices S5 and S6 from each domain forming the channel pore region [10,11,12,13,14]. This topology is highly conserved between Nav α-subunit isoforms, as illustrated by comparison of the Nav1.7 and Nav1.5 structures (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

The Nav channel α-subunit. (A) Cartoon representation showing internally homologous domains DI-DIV. In DI, the location of transmembrane alpha-helices, S1–S6, the extracellular loops (S1-2; S3-4; S5-P and P-S6) and the re-entrant P helices are indicated. The positive charges on the S4 helices of each domain are indicated. (B) Three-dimensional structures of human Nav1.7 (PDB: 6JH8I), rat Nav1.5 (PDB: 6UZ3), and their aligned structures. The channels are viewed from above the plane of the plasma membrane. For Nav1.5 and Nav1.7, the domains DI-DIV are coloured as in (A). For aligned structures, Nav1.7 is coloured blue–white and Nav1.5 is coloured pale green.

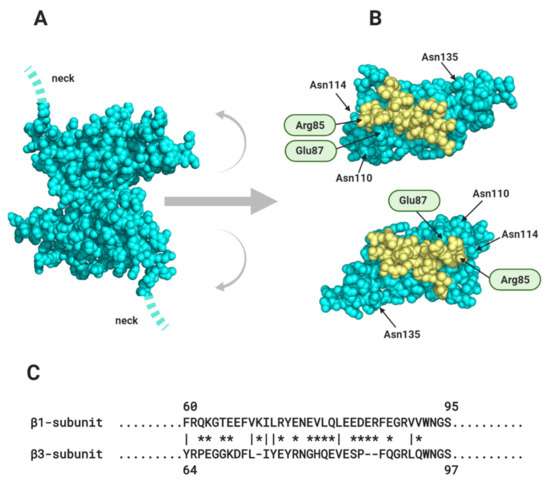

1.2. The Nav Channel β-Subunits and Their Binding Sites on the α-Subunits

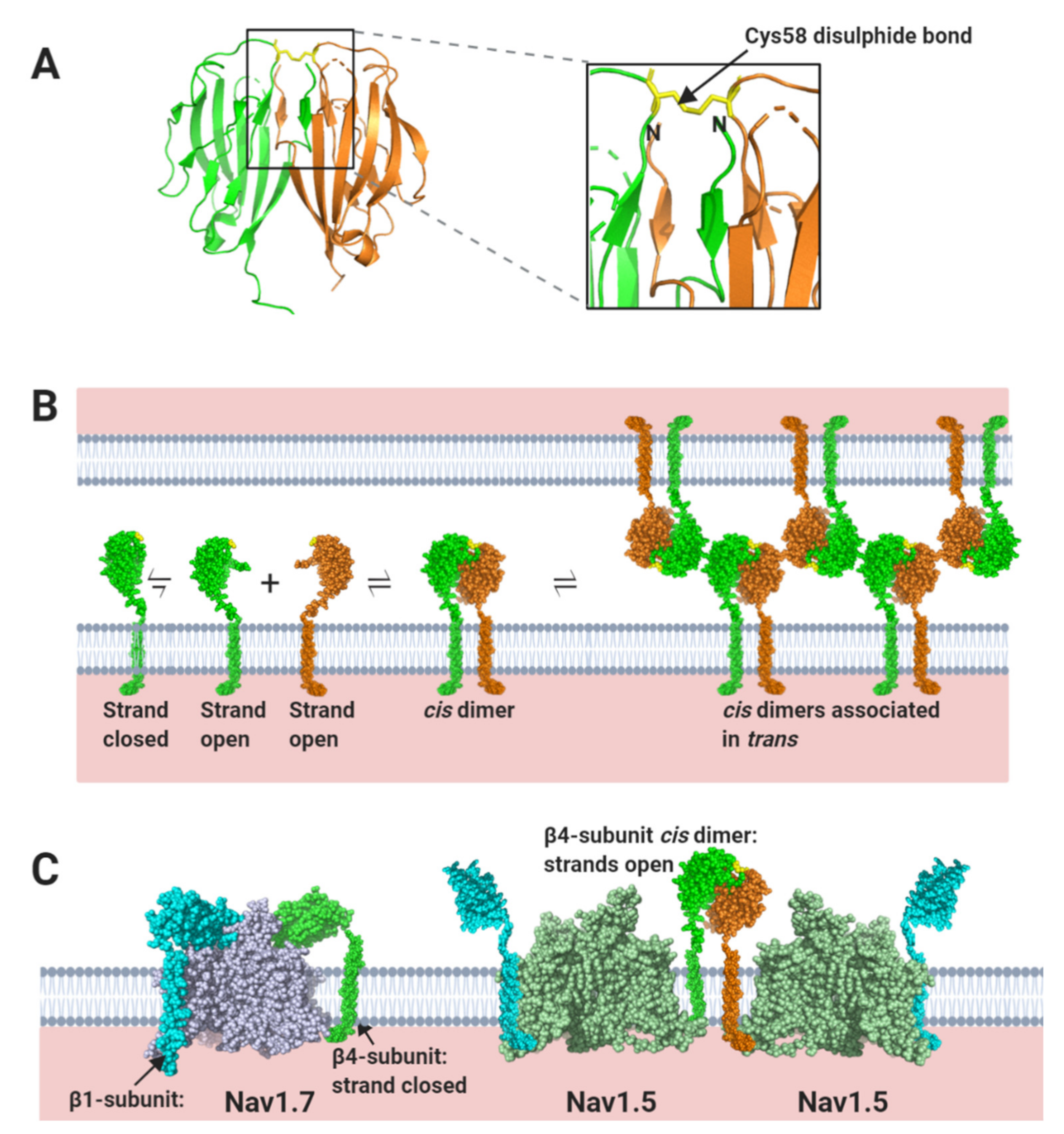

Vertebrate Nav channels are typically associated with one or more β-subunits (Mwt ~30–40 kDa). There are four homologous β-subunit genes (SCN1b-4b) encoding subunit proteins β1-β4 respectively. The β-subunits are type I transmembrane proteins consisting of a single extracellular N-terminal V-type immunoglobulin (Ig) domain, connected to a transmembrane alpha-helix by a flexible neck and terminating in a largely disordered intracellular C-terminal region (Figure 3A,B). An alternatively spliced form of β1, known as β1B, is also expressed in the heart. It consists of an Ig domain identical to that of β1, but lacks the transmembrane alpha-helix and is therefore secreted (Figure 3A) [15]. The β1- and β3-subunits show the closest sequence similarity to each other and are more distantly related to β2 and β4 (Figure 3C) [16,17]. The β-subunits have multiple effects on Nav channel gating behaviour that vary between individual β-subunit isoforms. In general terms however, they can increase the peak current density of Nav channels, probably by enhancing trafficking to the plasma membrane [2]. They also shift the voltage ranges over which Nav channel steady-state activation and/or inactivation occur, and in some cases enhance the rates of inactivation and recovery from inactivation [18]. As an illustrative example, the β3-subunit shifts the V½ for inactivation of Nav1.5 in a depolarising direction: i.e., the voltage at which half the channels are inactivated is displaced to a more positive value compared to the α-subunit alone (Figure 3D) [19,20,21,22]. For a cardiomyocyte with a resting potential of about -90 mV [2], this would act to increase the fraction of functional Nav1.5 channels available in the membrane [17].

Figure 3.

The Nav channel β-subunits. (A) Cartoon showing the common structural features of the β-subunits, including the alternatively spliced β1B isoform. (B) Atomic-resolution structures for the Ig domains of: β1 (PDB: 6JHI); β2, (PDB: 5FEB); β3 (PDB: 4L1D) and β4 (PDB: 5XAX). The separate disulphide bonds stabilising the N-terminal strands of β1 and β3 are labelled by hashtags and the free, exposed Cys residue on β2 (Cys55) and β4 (Cys58) are as indicated. (C) Phylogenetic analysis of Nav channel β-subunits, showing their relationship to members of the Ig domain-containing CAM protein family. PDCD1: programmed cell death protein 1 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q15116); CXAR: Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P78310); JAM: junctional adhesion molecule 2 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P57087); MYP0: myelin protein P0 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P25189); MPZL1: myelin protein zero-like protein (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O95297); MPZL2: myelin protein zero-like protein 2 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/O60487) and MPZL3: myelin protein zero-like protein 3 (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q6UWV2). The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the ClustalW2 package (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/phylogeny/simple_phylogeny/). (D) Idealised inactivation curves of the Nav1.5 channel in the absence (blue) and the presence (red) of the β3-subunit. The β3-subunit induces a depolarising (rightward) shift of the V½ of inactivation, as indicated on the diagram by the dotted lines.

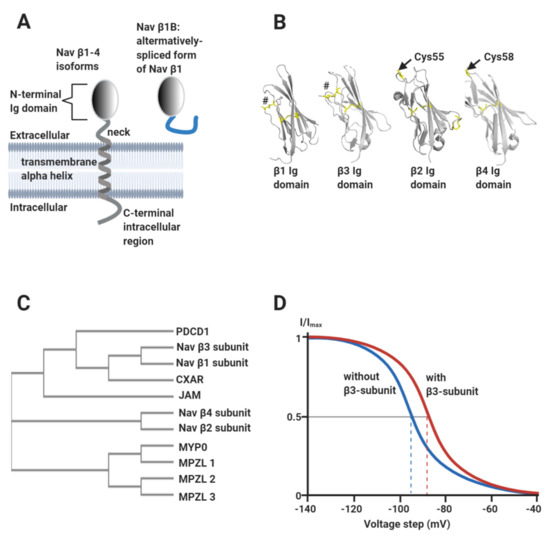

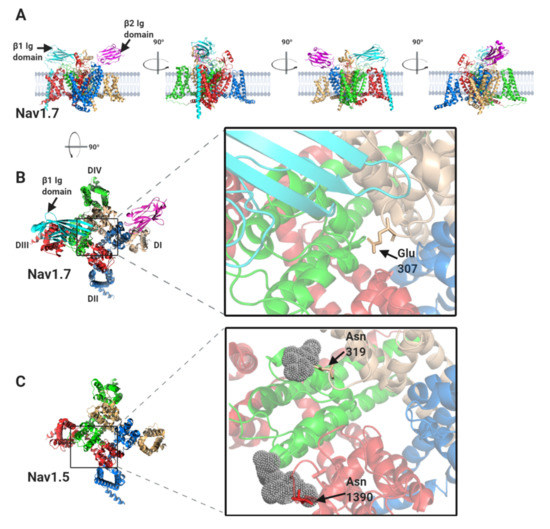

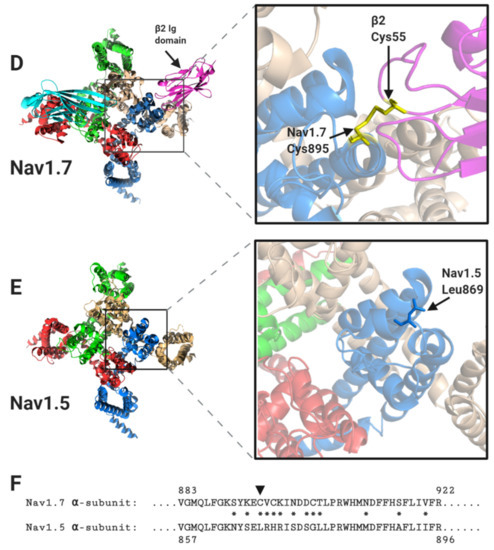

The β1-subunit interaction site has been resolved at high resolution for Nav1.2, Nav1.4 and Nav1.7 α-subunits [10,11,12,13] and is illustrated for the case of Nav1.7 in Figure 4A,B. The β1-subunit Ig domain makes ionic and hydrogen-bond contacts with the DI, S5-P extracellular loop, the DIII, S1–S2 extracellular loop and the DIV, P-S6 extracellular loop regions (Figure 2 and Figure 4B). Surprisingly however, the Nav1.5 α-subunit structure has revealed some localised, but structurally significant differences between Nav1.5 and the other studied Nav channels [14]. In particular, the Nav1.7 Glu307 residue in the DI, S5-P extracellular loop, is changed in Nav1.5 to an asparagine residue, Asn319. This creates an N-linked glycosylation site that is not present in any other Nav channel isoform. In the Nav1.5 cryo-EM structure, there is electron density around Asn319 that is consistent with a complex N-linked glycan (Figure 4C). It should be noted that the electron density detected in the cryo-EM data only corresponds with two N-acetyl glucosamine residues of the core glycan. The remaining, diverse sugar moieties of the terminal branches are not resolved, presumably due to their inherent flexibility. Thus the N-linked glycan attached to Nav1.5, Asn319 extends further than the resolved electron density and would certainly be bulky enough to occlude the binding site for the β1 Ig domain [12]. Moreover, the specific orientation of a second N-linked glycan attached to Nav1.5 residue Asn1390 will probably also interfere with the binding of the β1 Ig domain (Figure 4C). Hence, it seems likely that in vivo, although β1 may still be associated with the Nav1.5 DIII voltage sensing domain via its transmembrane alpha-helix, its Ig domain will not be able to bind to the Nav1.5 α-subunit.

Figure 4.

The binding sites for β1 and β2 on the Nav1.7 α-subunit and its comparison with Nav1.5. (A) Side views, each with 90° rotation, of the Nav1.7 α-subunit, with associated β1 and β2 -subunits. (B) Top view of the Nav1.7 α-subunit, with the β1 Ig domain binding site on the DI, DIII and DIV extracellular loops highlighted. (C) Top view of the equivalent region of Nav1.5 α-subunit. Resolved electron density corresponding to the N-linked sugar residues mentioned in the text are shown in grey dots. (D) Top view of the Nav1.7 α-subunit with the β2 Ig domain binding-site on DII extracellular loop highlighted. (E) Top view of the equivalent region of the Nav1.5 α-subunit. (F) Sequence alignment of human Nav1.7 and Nav1.5 α-subunits around the DII β2 binding-site. Amino acid differences between the two sequences are indicated by asterisks. The position of the Cys895 residue in Nav1.7, noted in the text, is indicated with an arrowhead.

Based on biochemical and electrophysiological data, it is probable that the β3-subunit transmembrane alpha-helix also binds to Nav1.5 DIII voltage sensing domain [19,20,21]. Yet, there is evidence that it may bind closer to Nav1.5 DIII helix S3 rather than to the binding site for the β1 transmembrane region on the DIII helix S2 [19,21]. If so, then a given Nav1.5 α-subunit may be able to bind simultaneously to β1 and β3-subunits and there is indeed electrophysiological evidence to support this idea [21,23].

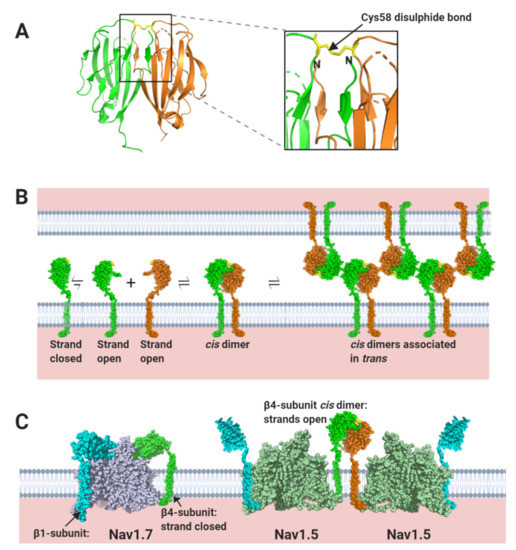

In contrast to β1 and β3, which bind to the α-subunit non-covalently, the β2-subunit binds to Nav1.7 covalently via a disulphide bond between a cysteine on the Ig domain (Cys55) and a corresponding cysteine (Cys895) on the α-subunit DII S5-P extracellular loop (Figure 4D) [12,24]. Neither the transmembrane alpha-helix nor the intracellular region of β2 is resolved in the published structure, indicating that both must be unconstrained in this purified complex [12]. As with β2, the β4-subunit Ig domain also contains a cysteine (Cys58) that can form a disulphide bond to the free cysteine on the α-subunit DII, S5-P site [25]. It is therefore presumed that the β2 and β4-subunit Ig domains covalently bind to the same or largely overlapping site on most Nav channel α-subunits [26,27]. Oddly however, the putative β2- and β4- subunit binding-site in Nav1.5 again shows important sequence differences from that on other Nav channels. Most notably, the residue equivalent to Cys895 of Nav1.7 is changed to leucine in Nav1.5 (Leu869) (Figure 4D–F). Since there are no other accessible free cysteines on the Nav1.5 extracellular surface, it will be impossible for either the β2- or the β4-subunit Ig domains to covalently bind Nav1.5 as they do to Nav1.7. Furthermore, the amino acid residues clustered around Nav1.7 Cys895 and which, in Nav1.7 provide additional contacts with the β2 Ig domain, are substantially different in Nav1.5 (Figure 4F).

Taken together, this evidence suggests that the Ig domains of all four β-subunits will be unable to bind to Nav1.5 directly, although the β-subunit transmembrane and intracellular regions may still do so. As a result, the Ig domains will be free to explore a greatly extended volume space above and around the Nav1.5 channel than β-subunits attached to most other Nav channels. What then are the likely functional consequences of this difference?

3. Conclusions and Unsolved Problems

On the cardiomyocyte membranes, the Nav channels form heterogeneous, multi-component macromolecular clusters, rather than remain as isolated molecules [111]. There is no necessary requirement for every Nav α-subunit to have an identical stoichiometry with any associated β-subunit [17]. Examples from other ion-channels show that the behaviour of membrane-bound clusters can change depending on variations in subunit ratios [112]. In such assemblies, individual protein components can have more than one function, depending on the physiological context. Although originally identified by their direct effects on channel gating, it is now clear that the Nav β-subunits extend their functions to include cell-adhesion and mechano-sensing and in doing so, raise further questions:

3.1. Evolutionary Relationship between Nav β-Subunits and Other CAMs

The Ig domain superfamily has deep evolutionary roots that pre-date the divergence of vertebrate and invertebrate lineages [113]. Yet the Nav channel β-subunits have only been discovered in vertebrate genomes, where they cluster together with members of the Ig domain-containing CAM family [30]. This close evolutionary relationship raises the intriguing possibility that homologues such as the MPZL1-3 group of proteins (Figure 3C), might act as additional Nav channel modulators. At least some of these proteins are expressed in heart tissue [114].

Although lacking β-subunits, invertebrate Nav channels do possess associated proteins that modulate gating and trafficking behaviour of their Nav channels. The best characterised are members of the TipE family [115]. However, these proteins show no sequence or structural similarity to vertebrate β-subunits and must have independently evolved their Nav channel-modulating behaviour. It will be interesting to see whether the TipE proteins can act as CAMs, or whether cell-adhesion is a unique feature of the vertebrate β-subunits.

3.2. The Biophysics of Nav β-Subunit Cell-Adhesion

We currently lack a quantitative understanding of the trans-mediated binding events facilitated by the β-subunits. For example, it would be interesting to know if the contacts between individual β1 Ig domains at the perinexus are strong and stable or individually weak enough to dissociate and rebind rapidly. The latter case might be more likely given the dynamic nature of membrane movements at the intercalated disc during the contraction, relaxation cycle [71]. The application of new biophysical techniques such as atomic force microscopy and traction force microscopy [116], combined with more traditional biochemical and molecular genetic techniques will be needed to address these questions.

3.3. The Role of N-Linked Glycosylation

Membrane proteins are generally N-linked glycosylated, with complex, branching sugar residues, often tipped with sialic acid moieties [117]. The role of N-linked glycosylation in the trafficking of Nav channels, including Nav1.5 - is well-established [118]. There is also evidence that the negatively charged sialic acids on N-linked glycans of Nav channel α and β-subunits can modulate channel gating [119]. In addition, the relatively large and bulky N-linked glycans can potentially modulate the strength and even the possibility of protein-protein interactions occurring. A good example is described above for the case of the β1 Ig domain binding to Nav1.5, and the likely role of the glycosylated Asn319 residue in preventing binding of the β1 Ig domain (Section 1.2, Figure 4C). Another example is in the model proposed for β1- trans cell-adhesion. Here, the putative trans-binding motif on the β1 Ig domain surface is surrounded by four of its five potential N-linked glycosylation sites (Section 2.1, Figure 7B). Could the strength of this interaction be fine-tuned by for example, developmentally regulated changes in the nature and extent of N-linked glycosylation?

3.4. Ephaptic Conduction in the Heart and Elsewhere

In cardiomyocytes, ephaptic conduction occurs in close association with gap junction structures mediating electrotonic conduction (Section 2.1, Figure 5), suggesting that both processes occur to relative extents, that might vary under different conditions [120]. It is likely that there are other biological situations where the necessary conditions for ephaptic conduction apply. Potential examples include the repetitive firing that occur in neuroendocrine supraoptic nucleus neurones [121,122] and the escape reflex triggered by activation of the goldfish Mauthner neurone [123]. Interestingly, the R85H mutation in the β1 Ig domain, that compromises ephaptic conduction between cardiomyocytes [66] (Section 2.1, Figure 7B), also predisposes to epilepsy [124], perhaps hinting at a similar role in neurones.

3.5. Clinical Implications

Assuming that electrical signalling between cardiomyocytes occurs both by electrotonic and ephaptic mechanisms, then a drug that inhibits the trans-mediated cell-adhesion between perinexal β1-subunits might reduce the signal propagation through cardiac muscle, whilst not completely preventing it. This could potentially reduce triggering of post-infarct arrythmias [125]. Conversely, drugs that stabilise these interactions could be useful as a treatment for other forms of arrythmias such as Brugada syndrome in which re-entrant arrhythmia results from a conduction slowing substrate [66]. It might also be possible to target specific β-subunit signalling pathways, for example the phosphorylation of the β1-subunit cytoplasmic region [126]. These are quite speculative, yet potentially attractive hypotheses that require further investigations. More broadly, the increasing emphasis on the cell-adhesion roles of Nav β-subunits in both healthy and pathological states, offers a more balanced perspective on these proteins and could open completely new avenues for therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation and writing, S.C.S., C.L.-H.H. and A.P.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

S.C.S was supported by British Heart Foundation project grants PG/14/79/31102 and PG/19/59/34582 (to S.C.S., C.L.-H.H., and A.P.J.) and by Isaac Newton Trust Grant G101770.

Acknowledgments

The figures were created with BioRender.com.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sweeney, H.L.; Hammers, D.W. Muscle Contraction. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortada, E.; Brugada, R.; Verges, M. Trafficking and Function of the Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel beta2 Subunit. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeMarco, K.R.; Clancy, C.E. Cardiac Na Channels: Structure to Function. Curr. Top. Membr. 2016, 78, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeraraghavan, R.; Gyorke, S.; Radwanski, P.B. Neuronal sodium channels: Emerging components of the nano-machinery of cardiac calcium cycling. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 3823–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, S.K.; Westenbroek, R.E.; McCormick, K.A.; Curtis, R.; Scheuer, T.; Catterall, W.A. Distinct subcellular localization of different sodium channel alpha and beta subunits in single ventricular myocytes from mouse heart. Circulation 2004, 109, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.A.; Huang, C.L.; Pedersen, T.H. Relationships between resting conductances, excitability, and t-system ionic homeostasis in skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2011, 138, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, T.H.; Huang, C.L.-H.; Fraser, J.A. An analysis of the relationships between subthreshold electrical properties and excitability in skeletal muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 2011, 138, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, C.A.; Payandeh, J.; Bosmans, F.; Chanda, B. The hitchhiker’s guide to the voltage-gated sodium channel galaxy. J. Gen. Physiol. 2016, 147, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, A.; Okamura, Y. Evolutionary History of Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2018, 246, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, L.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, G.; Peng, W.; Shen, H.; Lei, J.; Yan, N. Structure of the Nav1.4-beta1 Complex from Electric Eel. Cell 2017, 170, 470–482.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Shen, H.; Wu, K.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, X.; Lei, J.; et al. Structure of the human voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.4 in complex with beta1. Science 2018, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H.; Liu, D.; Wu, K.; Lei, J.; Yan, N. Structures of human Nav1.7 channel in complex with auxiliary subunits and animal toxins. Science 2019, 363, 1303–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Huang, G.; Gao, S.; Shen, H.; Liu, L.; Lei, J.; Yan, N. Molecular basis for pore blockade of human Na(+) channel Nav1.2 by the mu-conotoxin KIIIA. Science 2019, 363, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; Shi, H.; Tonggu, L.; Gamal El-Din, T.M.; Lenaeus, M.J.; Zhao, Y.; Yoshioka, C.; Zheng, N.; Catterall, W.A. Structure of the Cardiac Sodium Channel. Cell 2020, 180, 122–134.e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edokobi, N.; Isom, L.L. Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel beta1/beta1B Subunits Regulate Cardiac Physiology and Pathophysiology. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackenbury, W.J.; Isom, L.L. Na Channel beta Subunits: Overachievers of the Ion Channel Family. Front. Pharmacol. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namadurai, S.; Yereddi, N.R.; Cusdin, F.S.; Huang, C.L.; Chirgadze, D.Y.; Jackson, A.P. A new look at sodium channel beta subunits. Open Biol. 2015, 5, 140192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino, G.A.; Isom, L.L. Electrophysiology and beyond: Multiple roles of Na+ channel beta subunits in development and disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 486, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvage, S.C.; Zhu, W.; Habib, Z.F.; Hwang, S.S.; Irons, J.R.; Huang, C.L.H.; Silva, J.R.; Jackson, A.P. Gating control of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by its beta3-subunit involves distinct roles for a transmembrane glutamic acid and the extracellular domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvage, S.C.; Rees, J.S.; McStea, A.; Hirsch, M.; Wang, L.; Tynan, C.J.; Reed, M.W.; Irons, J.R.; Butler, R.; Thompson, A.J.; et al. Supramolecular clustering of the cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 in HEK293F cells, with and without the auxiliary beta3-subunit. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 3537–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Voelker, T.L.; Varga, Z.; Schubert, A.R.; Nerbonne, J.M.; Silva, J.R. Mechanisms of noncovalent beta subunit regulation of NaV channel gating. J. Gen. Physiol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim, P.; Gurung, I.S.; Pedersen, T.H.; Thresher, R.; Brice, N.; Lawrence, J.; Grace, A.A.; Huang, C.L. Scn3b knockout mice exhibit abnormal ventricular electrophysiological properties. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2008, 98, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.H.; Lenkowski, P.W.; Lee, H.C.; Mounsey, J.P.; Patel, M.K. Modulation of Na(v)1.5 by beta1- and beta3-subunit co-expression in mammalian cells. Pflug. Arch. 2005, 449, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Calhoun, J.D.; Zhang, Y.; Lopez-Santiago, L.; Zhou, N.; Davis, T.H.; Salzer, J.L.; Isom, L.L. Identification of the cysteine residue responsible for disulfide linkage of Na+ channel alpha and beta2 subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 39061–39069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.H.; Westenbroek, R.E.; Silos-Santiago, I.; McCormick, K.A.; Lawson, D.; Ge, P.; Ferriera, H.; Lilly, J.; DiStefano, P.S.; Catterall, W.A.; et al. Sodium channel beta4, a new disulfide-linked auxiliary subunit with similarity to beta2. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 7577–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, J.; Das, S.; Van Petegem, F.; Bosmans, F. Crystallographic insights into sodium-channel modulation by the beta4 subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E5016–E5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Gilchrist, J.; Bosmans, F.; Van Petegem, F. Binary architecture of the Nav1.2-beta2 signaling complex. eLife 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinarolo, S.; Granata, D.; Carnevale, V.; Ahern, C.A. Mining Protein Evolution for Insights into Mechanisms of Voltage-Dependent Sodium Channel Auxiliary Subunits. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2018, 246, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusano, K.; Thomas, T.N.; Fujiwara, K. Phosphorylation and localization of protein-zero related (PZR) in cultured endothelial cells. Endothelium 2008, 15, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.S.; Watanabe, H.; Zhong, T.P.; Roden, D.M. Molecular cloning and analysis of zebrafish voltage-gated sodium channel beta subunit genes: Implications for the evolution of electrical signaling in vertebrates. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007, 7, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, D.P.; Isom, L.L. Heterophilic interactions of sodium channel beta1 subunits with axonal and glial cell adhesion molecules. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 52744–52752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, K.H.; Castillo, D.G.; Morris, J.W.; Boggs, M.E.; Czymmek, K.J.; Adams, E.L.; Schramm, L.P.; Sikes, R.A. Identification of beta-2 as a key cell adhesion molecule in PCa cell neurotropic behavior: A novel ex vivo and biophysical approach. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namadurai, S.; Balasuriya, D.; Rajappa, R.; Wiemhofer, M.; Stott, K.; Klingauf, J.; Edwardson, J.M.; Chirgadze, D.Y.; Jackson, A.P. Crystal structure and molecular imaging of the Nav channel beta3 subunit indicates a trimeric assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 10797–10811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratcliffe, C.F.; Westenbroek, R.E.; Curtis, R.; Catterall, W.A. Sodium channel beta1 and beta3 subunits associate with neurofascin through their extracellular immunoglobulin-like domain. J. Cell Biol. 2001, 154, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Miyazaki, H.; Ohsawa, N.; Shoji, S.; Ishizuka-Katsura, Y.; Tosaki, A.; Oyama, F.; Terada, T.; Sakamoto, K.; Shirouzu, M.; et al. Structure-based site-directed photo-crosslinking analyses of multimeric cell-adhesive interactions of voltage-gated sodium channel beta subunits. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isom, L.L. The role of sodium channels in cell adhesion. Front. Biosci. 2002, 7, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manring, H.R.; Dorn, L.E.; Ex-Willey, A.; Accornero, F.; Ackermann, M.A. At the heart of inter- and intracellular signaling: The intercalated disc. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Merkel, C.D.; Zeng, X.; Heier, J.A.; Cantrell, P.S.; Sun, M.; Stolz, D.B.; Watkins, S.C.; Yates, N.A.; Kwiatkowski, A.V. The N-cadherin interactome in primary cardiomyocytes as defined using quantitative proximity proteomics. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinner, C.; Erber, B.M.; Yeruva, S.; Waschke, J. Regulation of cardiac myocyte cohesion and gap junctions via desmosomal adhesion. Acta Physiol. 2019, 226, e13242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, A.G.; Saffitz, J.E. Role of the intercalated disc in cardiac propagation and arrhythmogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vozzi, C.; Dupont, E.; Coppen, S.R.; Yeh, H.I.; Severs, N.J. Chamber-related differences in connexin expression in the human heart. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 1999, 31, 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodenough, D.A.; Goliger, J.A.; Paul, D.L. Connexins, connexons, and intercellular communication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996, 65, 475–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldberg, G.S.; Valiunas, V.; Brink, P.R. Selective permeability of gap junction channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1662, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Bai, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K.; Shen, B.; Sun, X. Current Concepts and Perspectives on Connexin43: A Mini Review. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2018, 19, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, A.G.; Rudy, Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 431–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohr, S. Role of gap junctions in the propagation of the cardiac action potential. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004, 62, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhett, J.M.; Veeraraghavan, R.; Poelzing, S.; Gourdie, R.G. The perinexus: Sign-post on the path to a new model of cardiac conduction? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2013, 23, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhett, J.M.; Gourdie, R.G. The perinexus: A new feature of Cx43 gap junction organization. Heart Rhythm. 2012, 9, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhett, J.M.; Ongstad, E.L.; Jourdan, J.; Gourdie, R.G. Cx43 associates with Na(v)1.5 in the cardiomyocyte perinexus. J. Membr. Biol. 2012, 245, 411–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, A.W.; Barker, R.J.; Zhu, C.; Gourdie, R.G. Zonula occludens-1 alters connexin43 gap junction size and organization by influencing channel accretion. Mol. Biol. Cell 2005, 16, 5686–5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, L.S.; Isom, L.L. Sodium channels as macromolecular complexes: Implications for inherited arrhythmia syndromes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005, 67, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorgen, P.L.; Trease, A.J.; Spagnol, G.; Delmar, M.; Nielsen, M.S. Protein(-)Protein Interactions with Connexin 43: Regulation and Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makara, M.A.; Curran, J.; Little, S.C.; Musa, H.; Polina, I.; Smith, S.A.; Wright, P.J.; Unudurthi, S.D.; Snyder, J.; Bennett, V.; et al. Ankyrin-G coordinates intercalated disc signaling platform to regulate cardiac excitability In Vivo. Circ. Res. 2014, 115, 929–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clatot, J.; Hoshi, M.; Wan, X.; Liu, H.; Jain, A.; Shinlapawittayatorn, K.; Marionneau, C.; Ficker, E.; Ha, T.; Deschenes, I. Voltage-gated sodium channels assemble and gate as dimers. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Fishman, G.I.; Peskin, C.S. Ephaptic conduction in a cardiac strand model with 3D electrodiffusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6463–6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Keener, J.P. Modeling electrical activity of myocardial cells incorporating the effects of ephaptic coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 20935–20940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hichri, E.; Abriel, H.; Kucera, J.P. Distribution of cardiac sodium channels in clusters potentiates ephaptic interactions in the intercalated disc. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 563–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperelakis, N. An electric field mechanism for transmission of excitation between myocardial cells. Circ. Res. 2002, 91, 985–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeraraghavan, R.; Lin, J.; Keener, J.P.; Gourdie, R.; Poelzing, S. Potassium channels in the Cx43 gap junction perinexus modulate ephaptic coupling: An experimental and modeling study. Pflug. Arch. 2016, 468, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, B.C.; Ponce-Balbuena, D.; Jalife, J. Protein assemblies of sodium and inward rectifier potassium channels control cardiac excitability and arrhythmogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H1463–H1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abriel, H.; Rougier, J.S.; Jalife, J. Ion channel macromolecular complexes in cardiomyocytes: Roles in sudden cardiac death. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1971–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milstein, M.L.; Musa, H.; Balbuena, D.P.; Anumonwo, J.M.; Auerbach, D.S.; Furspan, P.B.; Hou, L.; Hu, B.; Schumacher, S.M.; Vaidyanathan, R.; et al. Dynamic reciprocity of sodium and potassium channel expression in a macromolecular complex controls cardiac excitability and arrhythmia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2134–E2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopatin, A.N.; Nichols, C.G. Inward rectifiers in the heart: An update on I(K1). J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2001, 33, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burstein, B.; Nattel, S. Atrial fibrosis: Mechanisms and clinical relevance in atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 51, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeevaratnam, K.; Poh Tee, S.; Zhang, Y.; Rewbury, R.; Guzadhur, L.; Duehmke, R.; Grace, A.A.; Lei, M.; Huang, C.L. Delayed conduction and its implications in murine Scn5a(+/−) hearts: Independent and interacting effects of genotype, age, and sex. Pflug. Arch. 2011, 461, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, R.; Hoeker, G.S.; Alvarez-Laviada, A.; Hoagland, D.; Wan, X.; King, D.R.; Sanchez-Alonso, J.; Chen, C.; Jourdan, J.; Isom, L.L.; et al. The adhesion function of the sodium channel beta subunit (beta1) contributes to cardiac action potential propagation. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, J.D.; Kazen-Gillespie, K.; Hortsch, M.; Isom, L.L. Sodium channel beta subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell-cell contact. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 11383–11388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisch, T.B.; Yanoff, M.S.; Larsen, T.R.; Farooqui, M.A.; King, D.R.; Veeraraghavan, R.; Gourdie, R.G.; Baker, J.W.; Arnold, W.S.; AlMahameed, S.T.; et al. Intercalated Disk Extracellular Nanodomain Expansion in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Koopmann, T.T.; Le Scouarnec, S.; Yang, T.; Ingram, C.R.; Schott, J.J.; Demolombe, S.; Probst, V.; Anselme, F.; Escande, D.; et al. Sodium channel beta1 subunit mutations associated with Brugada syndrome and cardiac conduction disease in humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 2260–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Darbar, D.; Kaiser, D.W.; Jiramongkolchai, K.; Chopra, S.; Donahue, B.S.; Kannankeril, P.J.; Roden, D.M. Mutations in sodium channel beta1- and beta2-subunits associated with atrial fibrillation. Circ. Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009, 2, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobirumaki-Shimozawa, F.; Nakanishi, T.; Shimozawa, T.; Terui, T.; Oyama, K.; Li, J.; Louch, W.E.; Ishiwata, S.; Fukuda, N. Real-Time In Vivo Imaging of Mouse Left Ventricle Reveals Fluctuating Movements of the Intercalated Discs. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, J.D.; Koopmann, M.C.; Kazen-Gillespie, K.A.; Fettman, N.; Hortsch, M.; Isom, L.L. Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel beta 1 subunits with ankyrin. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 26681–26688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackenbury, W.J.; Djamgoz, M.B.; Isom, L.L. An emerging role for voltage-gated Na+ channels in cellular migration: Regulation of central nervous system development and potentiation of invasive cancers. Neuroscientist 2008, 14, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, J.D.; Thyagarajan, V.; Chen, C.; Isom, L.L. Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated sodium channel beta1 subunits are differentially localized in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 40748–40754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Barajas-Martinez, H.; Medeiros-Domingo, A.; Crotti, L.; Veltmann, C.; Schimpf, R.; Urrutia, J.; Alday, A.; Casis, O.; Pfeiffer, R.; et al. A novel rare variant in SCN1Bb linked to Brugada syndrome and SIDS by combined modulation of Na(v)1.5 and K(v)4.3 channel currents. Heart Rhythm. 2012, 9, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yereddi, N.R.; Cusdin, F.S.; Namadurai, S.; Packman, L.C.; Monie, T.P.; Slavny, P.; Clare, J.J.; Powell, A.J.; Jackson, A.P. The immunoglobulin domain of the sodium channel beta3 subunit contains a surface-localized disulfide bond that is required for homophilic binding. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 568–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, D.P.; Chen, C.; Meadows, L.S.; Lopez-Santiago, L.; Isom, L.L. The voltage-gated Na+ channel beta3 subunit does not mediate trans homophilic cell adhesion or associate with the cell adhesion molecule contactin. Neurosci. Lett. 2009, 462, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dhar Malhotra, J.; Chen, C.; Rivolta, I.; Abriel, H.; Malhotra, R.; Mattei, L.N.; Brosius, F.C.; Kass, R.S.; Isom, L.L. Characterization of sodium channel alpha- and beta-subunits in rat and mouse cardiac myocytes. Circulation 2001, 103, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, H.; Tosaki, A.; Ohsawa, N.; Ishizuka-Katsura, Y.; Shoji, S.; Miyazaki, H.; Oyama, F.; Terada, T.; Shirouzu, M.; Sekine, S.I.; et al. Parallel homodimer structures of the extracellular domains of the voltage-gated sodium channel beta4 subunit explain its role in cell-cell adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13428–13440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L.; Fannon, A.M.; Kwong, P.D.; Thompson, A.; Lehmann, M.S.; Grubel, G.; Legrand, J.F.; Als-Nielsen, J.; Colman, D.R.; Hendrickson, W.A. Structural basis of cell-cell adhesion by cadherins. Nature 1995, 374, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, O.J.; Brasch, J.; Lasso, G.; Katsamba, P.S.; Ahlsen, G.; Honig, B.; Shapiro, L. Structural basis of adhesive binding by desmocollins and desmogleins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7160–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasch, J.; Harrison, O.J.; Honig, B.; Shapiro, L. Thinking outside the cell: How cadherins drive adhesion. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros-Domingo, A.; Kaku, T.; Tester, D.J.; Iturralde-Torres, P.; Itty, A.; Ye, B.; Valdivia, C.; Ueda, K.; Canizales-Quinteros, S.; Tusie-Luna, M.T.; et al. SCN4B-encoded sodium channel beta4 subunit in congenital long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2007, 116, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarbrough, T.L.; Lu, T.; Lee, H.C.; Shibata, E.F. Localization of cardiac sodium channels in caveolin-rich membrane domains: Regulation of sodium current amplitude. Circ. Res. 2002, 90, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maguy, A.; Hebert, T.E.; Nattel, S. Involvement of lipid rafts and caveolae in cardiac ion channel function. Cardiovasc. Res. 2006, 69, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanon, V.P.; Sawaki, D.; Mjaatvedt, C.H.; Jourdan-Le Saux, C. Myocardial tissue caveolae. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 5, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aicart-Ramos, C.; Valero, R.A.; Rodriguez-Crespo, I. Protein palmitoylation and subcellular trafficking. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1808, 2981–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouza, A.A.; Philippe, J.M.; Edokobi, N.; Pinsky, A.M.; Offord, J.; Calhoun, J.D.; Lopez-Floran, M.; Lopez-Santiago, L.F.; Jenkins, P.M.; Isom, L.L. Sodium channel beta1 subunits are post-translationally modified by tyrosine phosphorylation, S-palmitoylation, and regulated intramembrane proteolysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alday, A.; Urrutia, J.; Gallego, M.; Casis, O. alpha1-adrenoceptors regulate only the caveolae-located subpopulation of cardiac K(V)4 channels. Channels (Austin) 2010, 4, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vaidyanathan, R.; Reilly, L.; Eckhardt, L.L. Caveolin-3 Microdomain: Arrhythmia Implications for Potassium Inward Rectifier and Cardiac Sodium Channel. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marionneau, C.; Carrasquillo, Y.; Norris, A.J.; Townsend, R.R.; Isom, L.L.; Link, A.J.; Nerbonne, J.M. The sodium channel accessory subunit Navbeta1 regulates neuronal excitability through modulation of repolarizing voltage-gated K(+) channels. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 5716–5727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabiri, B.E.; Lee, H.; Parker, K.K. A potential role for integrin signaling in mechanoelectrical feedback. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2012, 110, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabe, J.; Okumura, S.; Lee, M.C.; Sadoshima, J.; Ishikawa, Y. Translocation of caveolin regulates stretch-induced ERK activity in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H1845–H1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israeli-Rosenberg, S.; Chen, C.; Li, R.; Deussen, D.N.; Niesman, I.R.; Okada, H.; Patel, H.H.; Roth, D.M.; Ross, R.S. Caveolin modulates integrin function and mechanical activation in the cardiomyocyte. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M.J.; Wu, X.; Nurkiewicz, T.R.; Kawasaki, J.; Gui, P.; Hill, M.A.; Wilson, E. Regulation of ion channels by integrins. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2002, 36, 41–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyan, L.; Foell, J.D.; Vincent, K.P.; Woon, M.T.; Mesquitta, W.T.; Lang, D.; Best, J.M.; Ackerman, M.J.; McCulloch, A.D.; Glukhov, A.V.; et al. Long QT syndrome caveolin-3 mutations differentially modulate Kv 4 and Cav 1.2 channels to contribute to action potential prolongation. J. Physiol. 2019, 597, 1531–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vatta, M.; Ackerman, M.J.; Ye, B.; Makielski, J.C.; Ughanze, E.E.; Taylor, E.W.; Tester, D.J.; Balijepalli, R.C.; Foell, J.D.; Li, Z.; et al. Mutant caveolin-3 induces persistent late sodium current and is associated with long-QT syndrome. Circulation 2006, 114, 2104–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echarri, A.; Del Pozo, M.A. Caveolae—mechanosensitive membrane invaginations linked to actin filaments. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 2747–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, P.; Cooper, P.J.; Holloway, H. Effects of acute ventricular volume manipulation on In Situ cardiomyocyte cell membrane configuration. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2003, 82, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, B.; Koster, D.; Ruez, R.; Gonnord, P.; Bastiani, M.; Abankwa, D.; Stan, R.V.; Butler-Browne, G.; Vedie, B.; Johannes, L.; et al. Cells respond to mechanical stress by rapid disassembly of caveolae. Cell 2011, 144, 402–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wary, K.K.; Mariotti, A.; Zurzolo, C.; Giancotti, F.G. A requirement for caveolin-1 and associated kinase Fyn in integrin signaling and anchorage-dependent cell growth. Cell 1998, 94, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, C.A.; Zhang, J.F.; Wookalis, M.J.; Horn, R. Modulation of the cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5 by Fyn, a Src family tyrosine kinase. Circ. Res. 2005, 96, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyder, A.; Rae, J.L.; Bernard, C.; Strege, P.R.; Sachs, F.; Farrugia, G. Mechanosensitivity of Nav1.5, a voltage-sensitive sodium channel. J. Physiol. 2010, 588, 4969–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.E.; Juranka, P.F. Nav channel mechanosensitivity: Activation and inactivation accelerate reversibly with stretch. Biophys. J. 2007, 93, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroni, M.; Korner, J.; Schuttler, J.; Winner, B.; Lampert, A.; Eberhardt, E. beta1 and beta3 subunits amplify mechanosensitivity of the cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.5. Pflug. Arch. 2019, 471, 1481–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivumaki, J.T.; Clark, R.B.; Belke, D.; Kondo, C.; Fedak, P.W.; Maleckar, M.M.; Giles, W.R. Na(+) current expression in human atrial myofibroblasts: Identity and functional roles. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nattel, S. Electrical coupling between cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts: Experimental testing of a challenging and important concept. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rog-Zielinska, E.A.; Kong, C.H.T.; Zgierski-Johnston, C.M.; Verkade, P.; Mantell, J.; Cannell, M.B.; Kohl, P. Species differences in the morphology of transverse tubule openings in cardiomyocytes. Europace 2018, 20, iii120–iii124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostin, S.; Scholz, D.; Shimada, T.; Maeno, Y.; Mollnau, H.; Hein, S.; Schaper, J. The internal and external protein scaffold of the T-tubular system in cardiomyocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 1998, 294, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; O’Malley, H.; Chen, C.; Auerbach, D.; Foster, M.; Shekhar, A.; Zhang, M.; Coetzee, W.; Jalife, J.; Fishman, G.I.; et al. Scn1b deletion leads to increased tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium current, altered intracellular calcium homeostasis and arrhythmias in murine hearts. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 1389–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abriel, H. Cardiac sodium channel Na(v)1.5 and interacting proteins: Physiology and pathophysiology. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2010, 48, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitazawa, M.; Kubo, Y.; Nakajo, K. The stoichiometry and biophysical properties of the Kv4 potassium channel complex with K+ channel-interacting protein (KChIP) subunits are variable, depending on the relative expression level. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 17597–17609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doolittle, R.F. The multiplicity of domains in proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 287–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.J.; Zhao, R. Purification and cloning of PZR, a binding protein and putative physiological substrate of tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 29367–29372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Nomura, Y.; Du, Y.; Dong, K. Differential effects of TipE and a TipE-homologous protein on modulation of gating properties of sodium channels from Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamed, I.; Chowdhury, F.; Maruthamuthu, V. Biophysical Tools to Study Cellular Mechanotransduction. Bioengineering 2017, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsubo, K.; Marth, J.D. Glycosylation in cellular mechanisms of health and disease. Cell 2006, 126, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortada, E.; Brugada, R.; Verges, M. N-Glycosylation of the voltage-gated sodium channel beta2 subunit is required for efficient trafficking of NaV1.5/beta2 to the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 16123–16140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Montpetit, M.L.; Stocker, P.J.; Bennett, E.S. The sialic acid component of the beta1 subunit modulates voltage-gated sodium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 44303–44310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, R.; Gourdie, R.G.; Poelzing, S. Mechanisms of cardiac conduction: A history of revisions. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014, 306, H619–H627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, I.E.; Harkin, L.A.; Grinton, B.E.; Dibbens, L.M.; Turner, S.J.; Zielinski, M.A.; Xu, R.; Jackson, G.; Adams, J.; Connellan, M.; et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy and GEFS+ phenotypes associated with SCN1B mutations. Brain 2007, 130, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, S.C.; Li, D.; Li, T.; Yang, H.P.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.F.; Parpura, V. Role of Connexin 36 in Autoregulation of Oxytocin Neuronal Activity in Rat Supraoptic Nucleus. ASN Neuro. 2019, 11, 1759091419843762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micevych, P.E.; Popper, P.; Hatton, G.I. Connexin 32 mRNA levels in the rat supraoptic nucleus: Up-regulation prior to parturition and during lactation. Neuroendocrinology 1996, 63, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furshpan, E.J.; Furukawa, T. Intracellular and extracellular responses of the several regions of the Mauthner cell of the goldfish. J. Neurophysiol. 1962, 25, 732–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Keurs, H.E.; Zhang, Y.M.; Davidoff, A.W.; Boyden, P.A.; Wakayama, Y.; Miura, M. Damage induced arrhythmias: Mechanisms and implications. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2001, 79, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackenbury, W.J.; Isom, L.L. Voltage-gated Na+ channels: Potential for beta subunits as therapeutic targets. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2008, 12, 1191–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).