Bis-Bibenzyls from the Liverwort Pellia endiviifolia and Their Biological Activity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

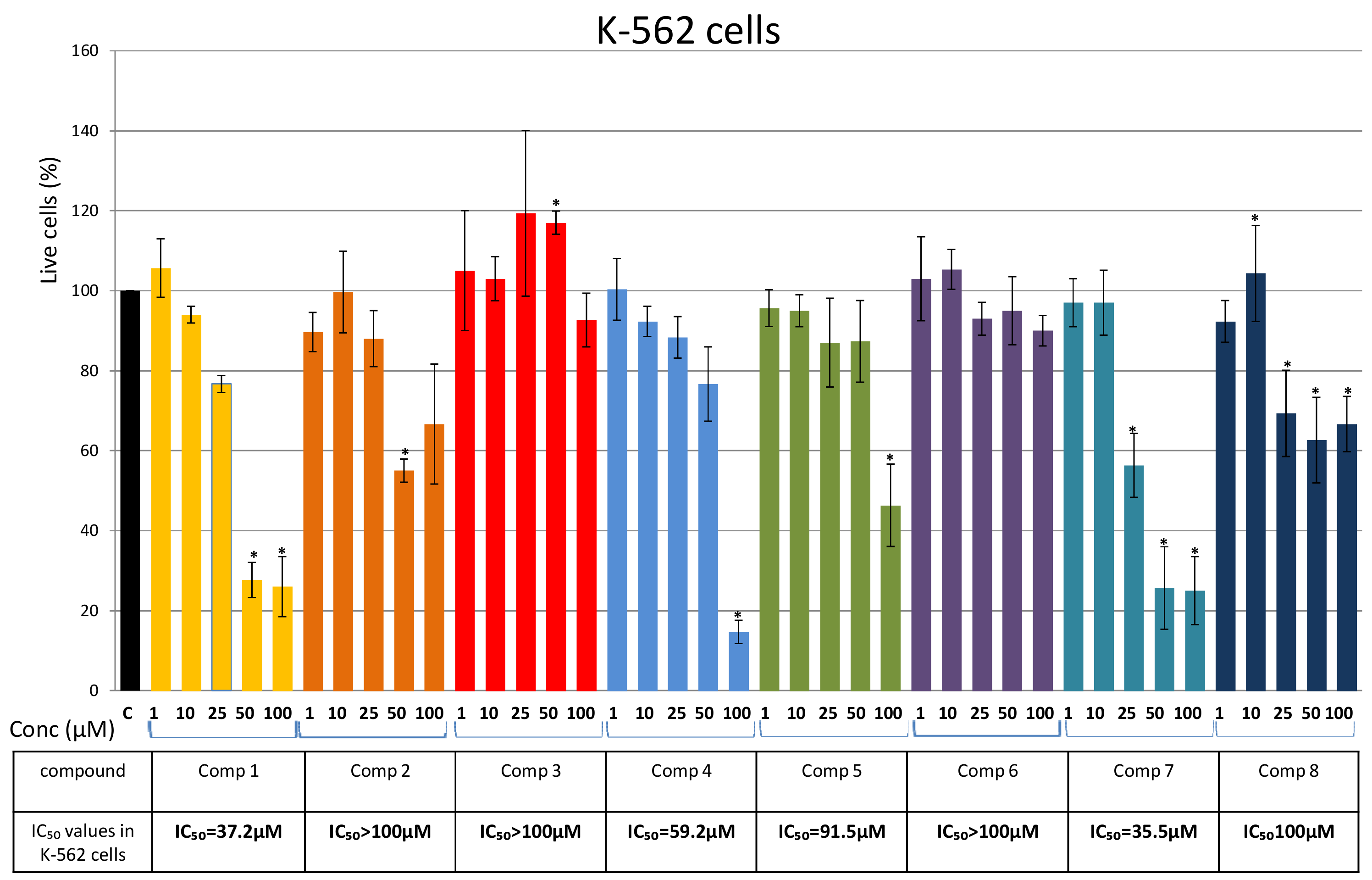

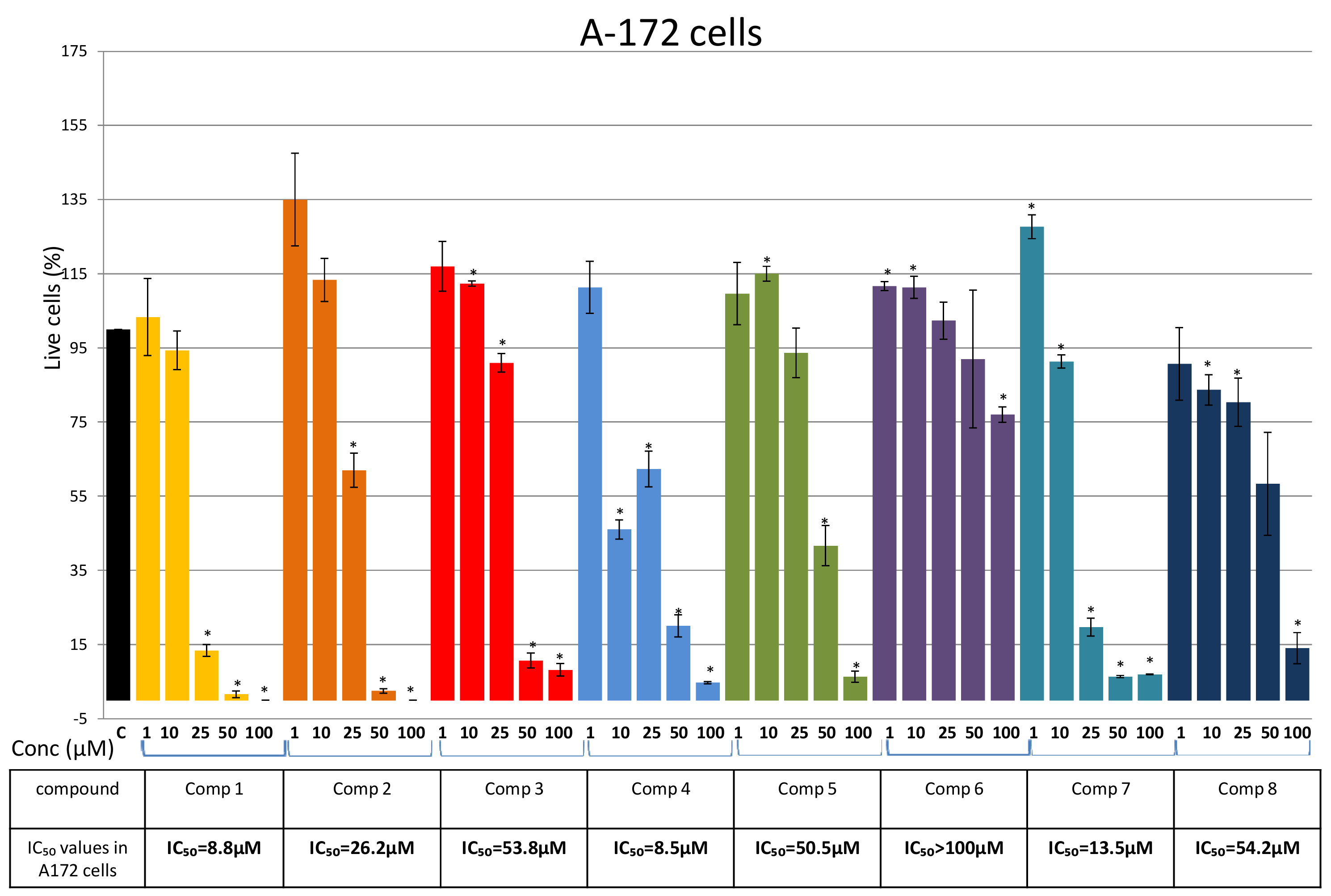

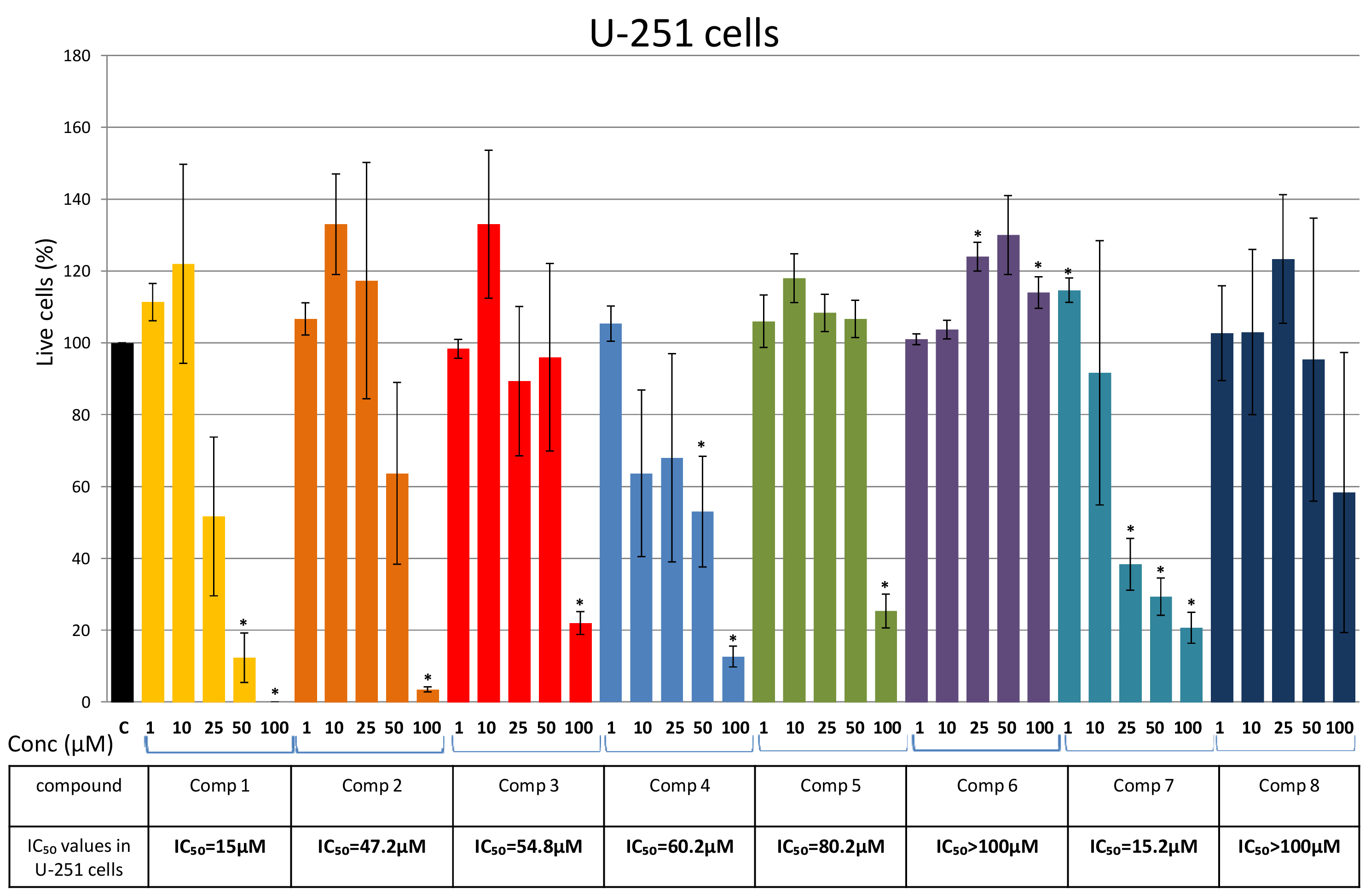

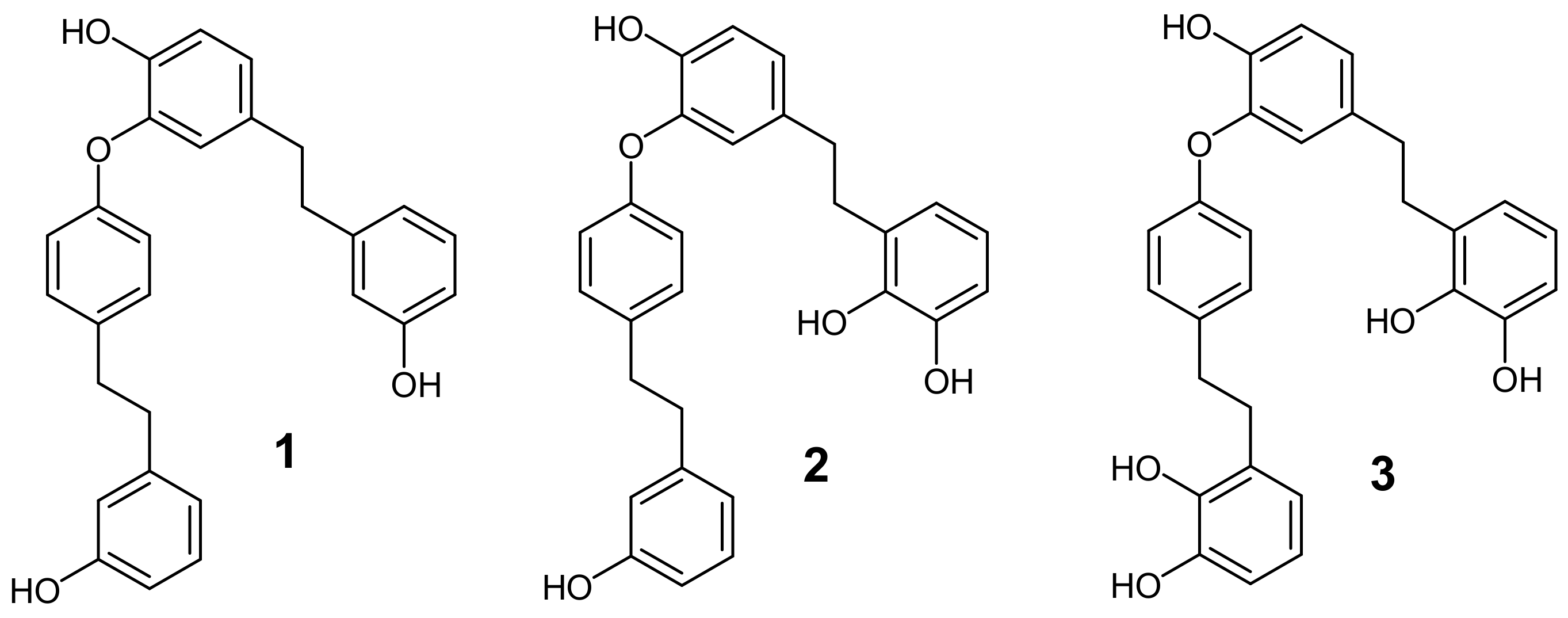

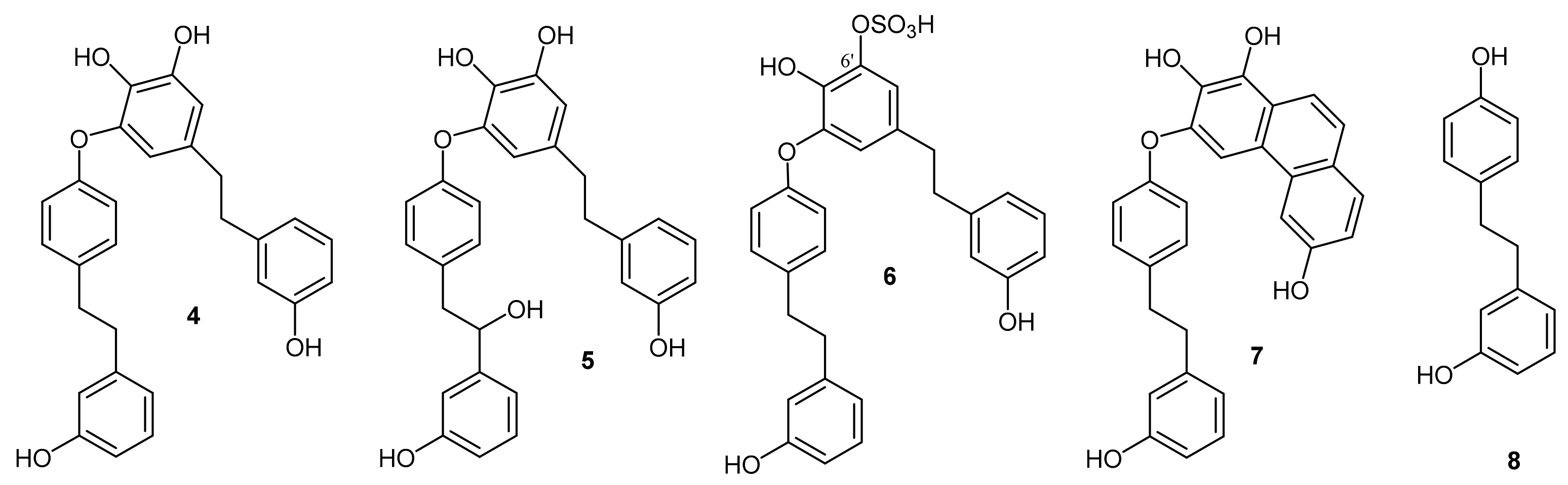

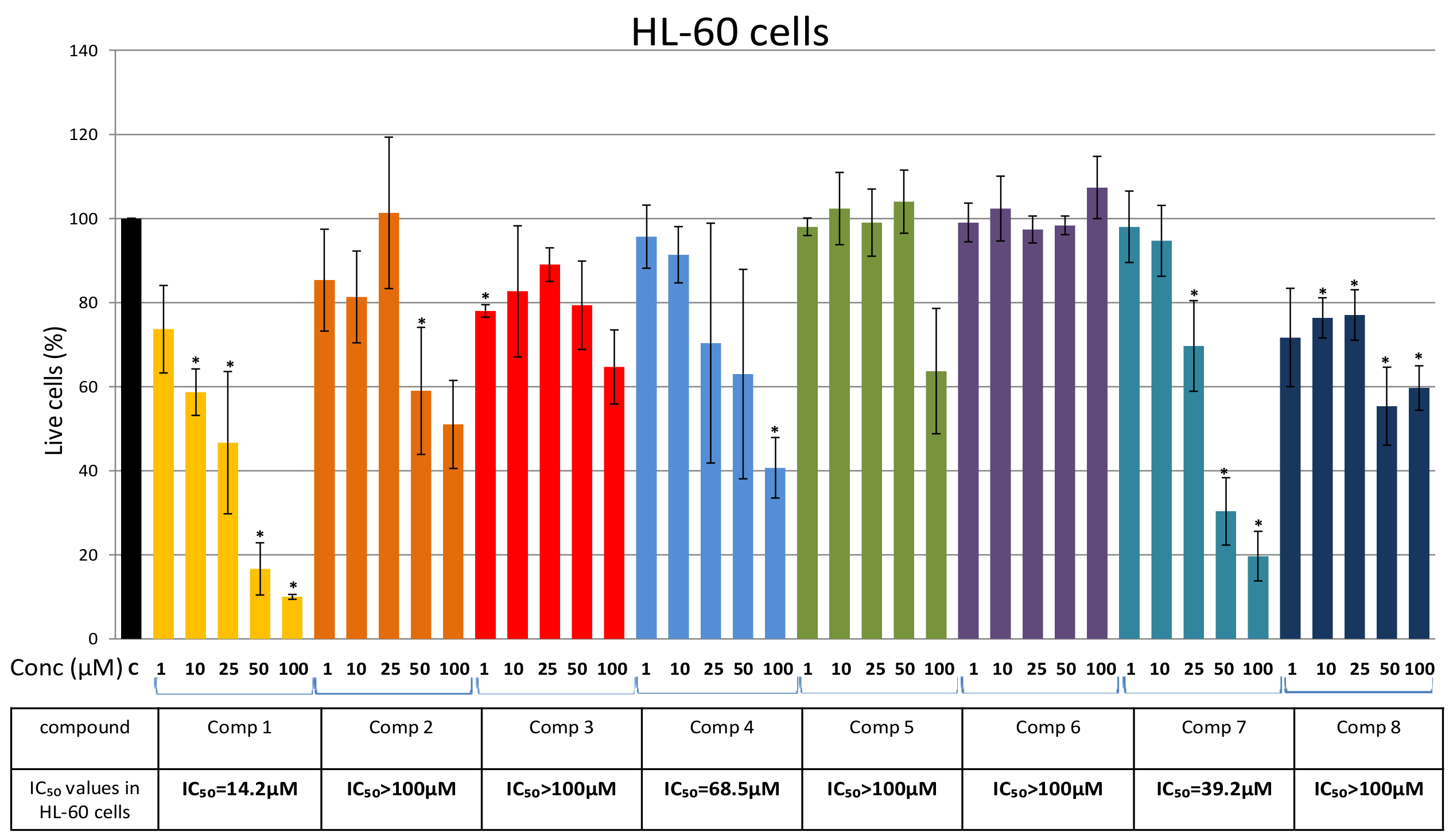

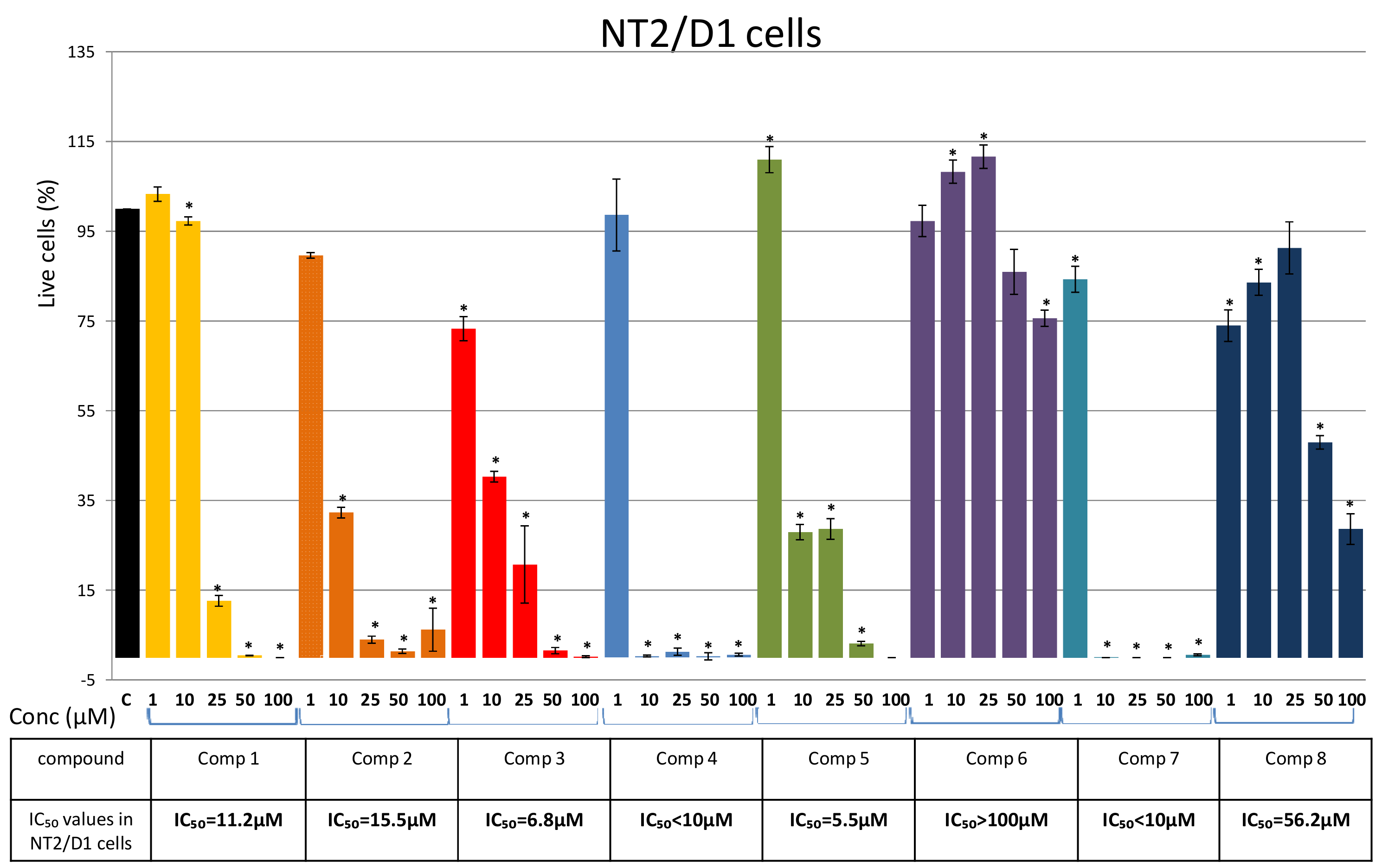

Isolation of Bis-Bibenzyls and Cytotoxic Activity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Extract Preparation

4.3. Dry Column Flash Chromatography

4.4. Isolation of Bis-Bibenzyls

4.5. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity Test

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chandra, S.; Chandra, D.; Barh, A.; Pankaj, R.; Pandey, K.; Sharma, I.P. Bryophytes: Hoard of remedies, an ethno-medicinal review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2016, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asakawa, Y. Biologically active compounds from Bryophytes. Pure App. Chem. 2007, 79, 557–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwizuk, A.; Nagashima, F. Phytochemical and biological studies of Bryophytes. Phytochemistry 2012, 91, 52–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speicher, A.; Groh, M.; Hennrich, M.; Huyhn, A.M. Syntheses of macrocyclic bis(bibenzyl) compounds derived from perrottetin E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 35, 6760–6778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Singh, K.K.; Asthana, A.K.; Nath, V. Ethnoterapeutics of bryophyte Plagiochasma appendiculatum among the Gaddi tribes of Kangra Valley, Himachal Pradesh, India. Pharm. Biol. 2000, 38, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Matsuo, A. Applied Bryology. In Advances in Bryology; Schultze Motel, W., Ed.; Cramer: Vaduz, Liechtenstein, 1984; Volume 2, pp. 133–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwizuk, A. Chemical Constituents of Bryophytes: Structures and Biological Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwizuk, A.; Nagashima, F.; Toyota, M.; Hashimoto, T.; Tori, M.; Fukuyama, Y.; Harinantenaina, L. Bryophytes: Bio- and Chemical Diversity, Bioactivity and Chemosystematics. Heterocycles 2009, 77, 99–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y. The Isolation, Structure Elucidation, and Bio- and Total Synthesis of Bis-bibenzyls from Liverworts and Their Biological Activity. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 1335–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parzych, A.; Jonczak, J.; Sobisz, Z. Pellia endiviifolia (Dicks.) Dumort. Liverwort with a Potential for Water Purification. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 12, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hashimoto, T.; Suzuki, H.; Tori, M.; Asakawa, Y. Bis(bibenzyl) Ethers from Pellia endiviifolia. Phytochemistry 1991, 5, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y.; Ludwizuk, A.; Nagashima, F. Chemical Constituents of Bryophytes, Bio- and Chemical Diversity, Biological Activity, and Chemosystematics. In Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2013; Volume 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y. Chemical Constituents of the Hepaticae. In Fortschritte der Chemie Organischer Naturstoffe/Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products; Herz, W., Grisebach, H., Kirby, G.W., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1982; Volume 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, F.; Momosaki, S.; Watanabe, Y.; Toyota, M.; Huneck, S.; Asakawa, Y. Terpenoids and Aromatic Compounds from six liverworts. Phytochemistry 1996, 41, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y. Recent advances in phytochemistry of Bryophytes-acetogenins, terpenoids and bis(bibenzyls) from selected Japanese, Taiwanese, New Zealand, Argentinean and European liverworts. Phytochemistry 2001, 56, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, Y. Highlights in phytochemistry of Hepaticae-biologically active terpenoids and aromatic compounds. Pure Appl. Chem. 1994, 66, 2193–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakovic, M.; Bukvicki, D.; Andjelkovic, B.; Ilic-Tomic, T.; Veljic, M.; Tesevic, V.; Asakawa, Y. Cytotoxic Activity of Riccardin and Perrottetin Derivatives from the Liverwort Lunularia cruciata. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 694–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukvicki, D.; Novakovic, M.; Ilic-Tomic, T.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; Todorovic, N.; Veljic, M.; Asakawa, Y. Biotransformation of Perrottetin F by Aspergillus niger: New Bioactive Secondary Metabolites. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullmann, F.; Becker, H.; Pandolfi, E.; Roeckner, E.; Eicher, T. Bibenzyl derivatives from, Pellia epiphylla. Phytochemistry 1997, 45, 1234–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, R.A.; Romero-Steiner, S.; Nahm, M.H. Use of HL-60 cell line to measure opsonic capacity of pneumococcal antibodies. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2005, 12, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Langlois, A.; Duval, D. Differentiation of NTERA-2 of human NT2 cells into neurons and glia Meth. Cell Sci. 1997, 19, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xie, R.; Wan, F.; Ye, F.; Guo, D.; Lei, T. Identification of U251 glioma stem cells and their heterogeneous stem-like phenotypes. Oncol. Lett. 2013, 6, 1649–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Guo, D.X.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, L.N.; Ji, M.; Lou, H.X. Aromatic compounds from the liverwort Conocephalum japonicum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2011, 6, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.Q.; Liao, Y.X.; Qu, X.J.; Yuan, H.Q.; Li, S.; Qu, J.B.; Lou, H.X. Marchantin C, a macrocyclic bisbibenzyl, induces apoptosis of human glioma A172 cells. Cancer Lett. 2008, 262, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Li, G.; Liu, Q.; He, Q.; Gu, J.; Shi, Y.; Lou, H. Marchantin C: A potential anti-invasion agent in glioma cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010, 9, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiang, J.; Sun, B.; Wang, Y.Y.; Cui, M.; Zhang, L.; Cui, C.Z.; Wang, Y.F.; Liu, X.G.; Lou, H.X. Synthesis of macrocyclic bisbibenzyl derivatives and their anticancer effects as anti-tubulin agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 2382–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.Q.; Fan, P.H.; Ji, M.; Lou, H.X. Terpenoids and bisbibenzyls from Chinese liverworts Conocephalum conicum and Dumortiera hirsuta. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2006, 8, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Hu, Z.M.; Qu, J.B.; Liu, S.M.; Syed, A.K.; Yuan, H.Q.; Lou, H.X. Cyclic bisbibenzyls induce growth arrest and apoptosis of human prostate PC3 cells. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2010, 31, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dey, A.; Mukherjee, A. Therapeutic potential of bryophytes and derived compounds against cancer. J. Acute Dis. 2015, 4, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xue, X.; Qu, X.-J.; Gao, Z.-H.; Sun, C.-C.; Liu, H.-P.; Zhao, C.-R.; Cheng, Y.-N.; Lou, H.-X. Riccardin D, a novel macrocyclic bisbibenzyl, induces apoptosis of human leukemia cells by targeting DNA topoisomerase II. Invest. New Drugs 2012, 30, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Q.; Qu, X.J.; Liao, Y.X.; Xie, C.F.; Cheng, Y.N.; Li, S.; Lou, H.X. Reversal effect of a macrocyclic bisbibenzyl plagiochin E on multidrug resistance in adriamycin-resistant K562/A02 cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 584, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, B.; Zhu, C.J.; Yuan, H.Q.; Shi, Y.Q.; Gao, J.; Li, S.J.; Lou, H.X. Reversal of p-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by macrocyclic bisbibenzyl derivatives in adriamycin-resistant human myelogenous leukemia (K562/A02) cells. Toxicol. In Vitro 2008, 23, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Yuan, H.-G.; Xi, G.-M.; Ma, Y.-D.; Lou, H.-X. Synthesis and multidrug resistance reversal activity of dihydroptychantol A and its novel derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 4981–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peral, M.F.; Koberle, B.; Masters, J.R.W. Exceptional sensitivity of testicular germ cell tumour cell lines to the new anti-cancer agent, temozolomide. Br. J. Cancer 1995, 71, 904–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zheng, G.Q.; Ho, D.K.; Elder, P.J.; Stephens, R.E.; Cottrell, C.E.; Cassady, J.M. Ohioensins and pallidisetins: Novel cytotoxic agents from the moss Polytrichum pallidisetum. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.Q.; Zhu, C.J.; Yuan, H.Q.; Li, B.Q.; Gao, J.; Qu, X.J.; Sun, B.; Cheng, Y.-N.; Li, S.; Li, X.; et al. Marchantin C, a novel microtubule inhibitor from liverwort with anti-tumor activity both in vivo and in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2009, 276, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivković, I.; Novaković, M.; Veljić, M.; Mojsin, M.; Stevanović, M.; Marin, P.D.; Bukvički, D. Bis-Bibenzyls from the Liverwort Pellia endiviifolia and Their Biological Activity. Plants 2021, 10, 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10061063

Ivković I, Novaković M, Veljić M, Mojsin M, Stevanović M, Marin PD, Bukvički D. Bis-Bibenzyls from the Liverwort Pellia endiviifolia and Their Biological Activity. Plants. 2021; 10(6):1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10061063

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvković, Ivana, Miroslav Novaković, Milan Veljić, Marija Mojsin, Milena Stevanović, Petar D. Marin, and Danka Bukvički. 2021. "Bis-Bibenzyls from the Liverwort Pellia endiviifolia and Their Biological Activity" Plants 10, no. 6: 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10061063

APA StyleIvković, I., Novaković, M., Veljić, M., Mojsin, M., Stevanović, M., Marin, P. D., & Bukvički, D. (2021). Bis-Bibenzyls from the Liverwort Pellia endiviifolia and Their Biological Activity. Plants, 10(6), 1063. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10061063