Abstract

Phytochemicals are essential raw materials for the production of formulations that can be helpful in crop protection. In particular, Hibiscus spp., which are often used in traditional medicine, are rich in potential bioactive molecules. This study presents an analysis of the thermal, vibrational, and phytochemical characteristics of a light purple variety of Hibiscus syriacus, using thermal gravimetric and differential scanning calorimetry, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, and gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy techniques. Further, with a view to its valorization, the antimicrobial activity of its extracts has been investigated in vitro against Erwinia amylovora (the phytopathogen responsible for fire blight in apples, pears, and some other members of the family Rosaceae), Erwinia vitivora (the causal agent of the “maladie d’Oléron” in grapevines), and Diplodia seriata (responsible for “Bot canker”). Higher heating values and thermal features showed similarities with kenaf biomass. The main compounds identified in the hydro-methanolic extracts were: in flowers, 1-heptacosanol, heptacosane, 1-tetracosanol, hexadecenoic acid, 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid, and 9,12-octadecadienoic acid; and in leaves, the coumarin derivative 4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-2-chromanone, vitamin E, phytol, and sitosterol. MIC values of 500 and 375 μg·mL−1 were obtained against E. amylovora for flower and leaf extracts, respectively, upon conjugation with chitosan oligomers (to improve solubility and bioavailability). In the case of E. vitivora, MIC values of 250 and 500 μg·mL−1, respectively, were registered. Regarding the antifungal activity, EC90 values of 975.8 and 603.5 μg·mL−1, respectively, were found. These findings suggest that H. syriacus (cv. ‘Mathilde’) may be a promising source of antimicrobials for agriculture.

1. Introduction

Crop protection is key to global food sustainability and security (in line with Sustainable Development Goal 2 in the 2030 Agenda). Synthetic pesticides have traditionally been used by farmers to control and eradicate pests, but they have detrimental effects on the health of consumers and the environment. To ensure sustainable production patters (SDG Target 12.4) and increase food security, current legislative frameworks promote the use of integrated pest management. In particular, the use of plant extracts as “green agrochemicals” should be intensified. Plants produce a wide range of primary and secondary metabolites (carbohydrates, cyanogenic glycosides, amino acids, lipids, phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, alkaloids, and terpenoids, among others) that have bactericidal, fungicidal, virucidal, insecticidal, acaricidal, and nematicidal activities. These phytochemicals are essential raw materials for the production of formulations that can be helpful in crop protection and preservation. However, in spite of the increasing demand for ecofriendly options to manage agricultural pests, the number of botanical-based products remains restricted. The identification of bioactive phytoconstituents in plant extracts thus forms a critical step in the development of commercial biocontrol products, and there is a need for screening promising candidate biorationals.

The genus Hibiscus (subkingdom Magnoliophyta, class Magnoliopsida, family Malvaceae), which contains 300 species distributed around the world, constitutes an interesting source of potential bioactive molecules with diverse biological activities, as discussed in the review papers by Vasudeva et al. [1] and Maganha et al. [2]. In fact, a wide range of bioactive phytochemicals have been reported for H. sabdariffa, H. tiliaceus, H. rosa-sinensis, and H. mutabilis extracts in the literature [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

In the case of H. syriacus, the species studied herein, there is less available information. Nonetheless, the presence of nonanedioic acid, suberic acid, 1-octacosanol, β-sitosterol, 1,22-docosanediol, betulin, and erythrotriol [15] has been reported for its bark. Methanolic–formic acid extraction of its petals yielded 3-O-malonylglucosides of delphinidin, cyanidin, petunidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and malvidin [16]. A study of its leaves led to the identification of β-sitosterol, β-daucosterol, β-amyrin, oleanolic acid, stigmast-4-en-3-one, friedelin, syriacusin A, kaempferol, isovitexin, vitexin, apigenin, apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, vitexin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, and rutin [17]. More recently, five polyphenols (hydroquinone, naringeninic acid, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde, vanillic acid, and fumalic acid) and five fatty acids ((2E)-2,6-dimethyl-6-hydroxy-2,7-octadienoic acid, palmitic acid, butyl linoleate, linoleic acid, and stearic acid) were identified in the ethanol extract of the flowers [18]. Hibispeptins A and B [19], triterpene caffeates [20], and syriacusins A-C [21] as antioxidants have been found in the roots, and triterpenoids such as 3β-acetoxy-olean-11-en,28,13β-olide, 3β-acetoxy-11α,12α-epoxy-olean-28,13β-olide, 19α-epi-betulin, and 20,28-epoxy-17β,19β-lupan-3β-ol have been identified in the root bark [22].

With regard to the applicability of aforementioned phytoconstituents, studies on the antimicrobial properties of H. syriacus extracts have been mostly restricted to human pathogens: for instance, extracts from the whole plant were assessed by Punasiya et al. [23] against Bacillus cereus, Staphylococcus aureus, and Klebsiella pneumoniae, and its seed oil showed activity against Escherichia coli, Salmonella newport, S. aureus, S. albus, B. subtilis, and B. anthracis [24].

Concerning potential applications in crop protection, the fungicidal activity of its seed oil was explored against Alternaria solani, Aspergillus niger, Colletotrichum dematium, and Fusarium oxysporum [24]; its bark showed antifungal activity against Trichophyton interdigitale [25]; and—in a study of a methanolic extract of roots—activity against T. mentagrophytes was reported, which was attributed to nonanoic acid [8]. However, no studies on flower and leaf extracts as biorationals in agriculture have been found after a thorough bibliographical survey.

In view of this research gap, the work presented herein aims to: (i) identify the specific phytochemicals present in the flower and leaf hydromethanolic extracts of H. syriacus cv. ‘Mathilde’; and (ii) investigate their antimicrobial activity against apple tree and grapevine pathogens. In particular, against two bacteria—catalogued as quarantine organisms—and a fungus: Erwinia amylovora (Burrill) Winslow, Broadhurst, Buchanan, Krumwiede, Rogers and Smith; Erwinia vitivora Du Plessis (syn. Xylophilus ampelinus (Panagopoulos) Willems, Gillis, Kersters, van den Broeke & De Ley); and Diplodia seriata De Not., respectively. Up-to-date information on E. amylovora, the causal agent of fire blight—a devastating disease of apples and pears—may be found in the review by Zhao et al. [26]. E. vitivora, which causes bacterial blight of grapevine (the “maladie d’Oléron” or “mal nero”), results in over 70% harvest losses [27], and its symptoms are often confused with those of “black dead arm” (BDA), caused by Botryosphaeriaceae fungi. Among the latter, D. seriata is one of the most abundant, and affects a wide range of woody hosts, including not only grapevine [28,29], but also apples, causing “Bot canker”, frog-eye leaf spot, and black rot [30,31,32].

2. Results

2.1. Physico-Chemical Characterization

2.1.1. Elemental Analysis and Calorific Values Calculation

The C, H, N, and S percentages of Hibiscus syriacus components (wt.% of dry material) were in the 34.4–42.8%, 6.3–6.4%, 2.2–2.8%, and 0.1–0.2% ranges, respectively (Table 1). The distribution of nitrogen content showed maximum values in the flowers and slightly lower in the leaves and stems.

Table 1.

Elemental (CHNS) composition (wt.%) of flowers and leaves of Hibiscus syriacus.

The calculated (from elemental analysis data) higher heating values (HHV) for flowers and leaves were 16.98 and 12.96 kJ·g−1, respectively, with a mean value of 14.97 kJ·g−1.

2.1.2. Thermal Characterization

The DSC curve for H. syriacus flowers (Figure S1) showed exothermal effects at 315, 425, and 443–450–470 °C. The ash content at 550 °C, according to the TG curve, was 6.3%. In turn, the DSC curve of H. syriacus leaves showed exothermal effects at 325 and 445 °C. The ash content at 500 °C was 20.6% (Figure S2).

2.1.3. Vibrational Characterization

An inspection of the absorption bands, summarized in Table 2, revealed a composition rich in fatty alcohols, fatty acids, and esters. The broad band at around 3300 cm−1 is assigned to the OH stretching vibration, and indicates the presence of primary alcohols. The two intense bands at 2920 and 2850 cm−1 are due to CH2 asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations, respectively. The band at 1734 cm−1 is assigned to the C=O stretching vibration of the carboxylic groups in esters. At 1441 cm−1, there is a band that can be ascribed to CH2 bend (scissors) deformation vibration. Several bands also attributed to CH2 vibrations (wagging and twisting) are observed in the 800–1400 cm−1 range. The band at 719 cm−1, assigned to the CH2 rocking mode, is indicative (when it appears together with the other CH2 vibrations) of the presence of long-chain linear aliphatic molecules. In the spectrum of leaves, the C=C vibration at 1634 cm−1 points to the presence of coumarin derivatives, as discussed below.

Table 2.

Main bands in the ATR-FTIR spectra of Hibiscus syriacus flowers and leaves and their assignments. Peak positions are expressed in cm−1.

2.1.4. Identification of Active Components in the Flower and Leaf Extracts by GC–MS

Among the 43 compounds identified in H. syriacus flower hydromethanolic extract (Figure S3, Table 3), the principal constituents were: 1-heptacosanol (m/z = 57 and 83) (15.3%) and heptacosane (7%); 1-tetracosanol or lignoceryl alcohol (11%); hexadecanoic acid and its esters (9.6%); 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid and its esters (3.5%); 9,12-octadecadienoic acid and its esters (5.2%); 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one or DDMP-4-one (4%); Z-12-pentacosene (2.5%); and 5-HMF (2.5%). It is worth noting that the methyl esters may be artifacts associated with the use of methanol as the extractive solvent [33].

Table 3.

Main compounds identified in Hibiscus syriacus flower hydromethanolic extract by GC–MS.

Concerning the leaf hydromethanolic extracts, in which 27 compounds were identified, the main constituents were: the coumarin derivative 4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-3H-chromen-2-one (m/z = 162, 189 and 204) (23%); vitamin E homologues (17%); diterpenoid phytol and this acetate (12%); phytosterols as campesterol, stigmasterol, and sitosterol (9%); selinenes (3.5%); squalene (3%); and the methyl esters of 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic acid (2.5%) and 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (2.5%) (Figure S4, Table 4).

Table 4.

Main compounds identified in Hibiscus syriacus leaf hydromethanolic extract by GC–MS.

2.1.5. Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Contents

The evaluation of TPC and TFC in the hydromethanolic extracts from H. syriacus flowers resulted in 800 mg GAE/100 mg and 315 mg CE/100 mg contents, respectively. As regards the leaf extracts, the TPC and TFC contents were 425 mg GAE/100 mg and 280 mg CE/100 mg, respectively.

2.2. Antimicrobial Activity of H. syriacus Extracts and their Phytochemicals

2.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

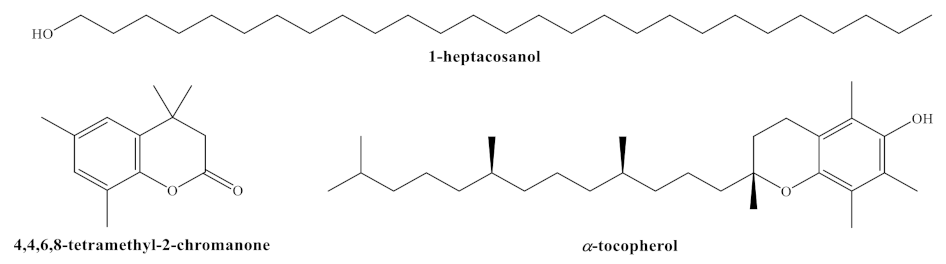

The antibacterial activity against E. amylovora and E. vitivora of chitosan oligomers (COS), H. syriacus flower and leaf hydromethanolic extracts, their main constituents (heptacosanol, DHTMC and vitamin E, Figure 1), and their corresponding conjugate complexes with COS are summarized in Table 5.

Figure 1.

Structures of main phytochemicals found in H. syriacus cv. Mathilde: 1-heptacosanol; 4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-2-chromanone (or 3,4-dihydro-4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-coumarin, DHTMC); and α-tocopherol or vitamin E.

Table 5.

Antibacterial activity of chitosan oligomers (COS), H. syriacus flower and leaf hydromethanolic extracts, their main constituents (heptacosanol, DHTMC, and vitamin E), and their corresponding conjugate complexes (COS–flower extract, COS–leaf extract, COS–heptacosanol, COS–DHTMC, and COS–vitamin E) against the two phytopathogenic bacteria under study at different concentrations (expressed in μg·mL−1).

Both the flower and leaf extracts showed an antimicrobial activity higher than (or comparable to, in the case of E. vitivora for the leaf extract) that of chitosan. Moreover, the flower extract resulted in lower MIC values than those attained with the leaf extract against both pathogens (750 vs. 1000 μg·mL−1 against E. amylovora, and 500 vs. 1500 μg·mL−1 against E. vitivora). This is an unexpected result, given that the main constituent of the flower extract (heptacosanol) showed a lower efficacy than the two main compounds present in the leaf extract (DHTMC and vitamin E) in the case of E. amylovora, and comparable to that of vitamin E in the case of E. vitivora. Hence, other constituents of the flower extract must contribute to its activity, as discussed below.

Upon conjugation with COS, a noticeable enhancement in the antibacterial activity was attained for all the assayed products. In particular, MIC values of 500 and 375 μg·mL−1 were obtained against E. amylovora for flower and leaf extracts, respectively. In the case of E. vitivora, MIC values of 250 and 500 μg·mL−1, respectively, were registered. Concerning the main constituents, the best results against E. amylovora (MIC = 250 μg·mL−1) were registered for COS–vitamin E, while COS–heptacosanol and COS–DHTMC led to the lowest MIC values against E. vitivora (187.5 μg·mL−1).

2.2.2. Antifungal Activity

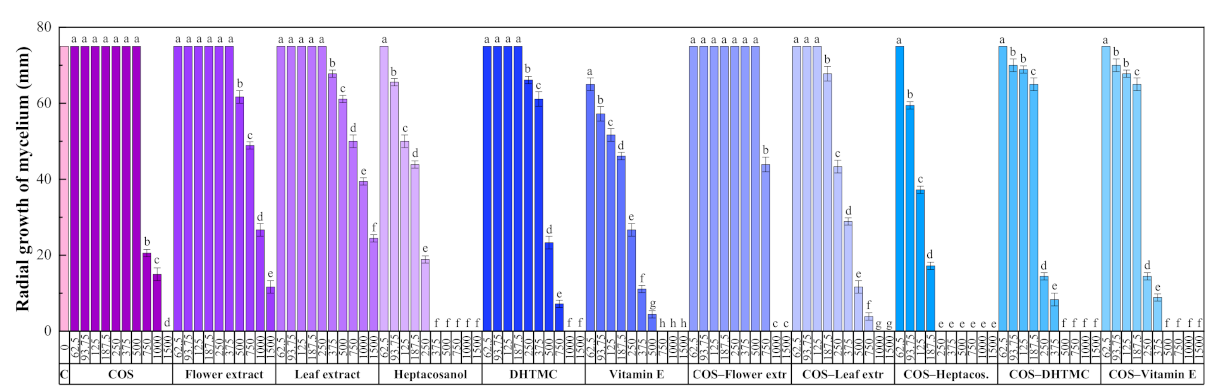

The results of the antifungal susceptibility test (mycelial growth inhibition using the agar dilution method) are summarized in Figure 2. For all the assayed products, an increase in the concentration led to a decrease in the radial growth of the mycelium, resulting in statistically significant differences.

Figure 2.

Radial growth of the mycelium for D. seriata in in vitro tests conducted in PDA medium with different concentrations (in the 62.5–1500 µg·mL−1 range) of chitosan oligomers (COS), H. syriacus flower and leaf extracts, their main phytochemical constituents, and their respective conjugate complexes. The same letters above concentrations mean that they are not significantly different at p < 0.05. Error bars represent standard deviations.

The two H. syriacus extracts showed a lower antifungal activity than COS, for which full inhibition was attained at 1500 μg·mL−1. Nonetheless, the main constituents of the extracts, viz. heptacosanol, DHTMC, and vitamin E, showed a stronger antifungal action (reaching full inhibition at 375, 1000, and 750 μg·mL−1, respectively).

The formation of conjugate complexes again led to an improvement in terms of antifungal activity: full inhibition was attained at 1000 μg·mL−1 for both COS–flower and COS–leaf extracts conjugates (a value lower than that obtained with COS alone), and at 250, 500, and 500 μg·mL−1 for COS–heptacosanol, COS–DHTMC, and COS–vitamin E, respectively (Figure S5). This enhancement is clearly observed in the effective concentration values summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

EC50 and EC90 effective concentrations of H. syriacus flower and leaf extracts and their phytochemicals against D. seriata, alone and upon conjugation with chitosan oligomers (COS).

Calculation of synergy factors, presented in Table 7, confirmed the aforementioned strong synergistic behavior for COS–heptacosanol and COS–vitamin E (with SFs of 2.59 and 3.14 for the EC90, respectively). Nonetheless, SFs > 1 were obtained in all cases.

Table 7.

Synergy factors, estimated according to Wadley’s method, for the conjugate complexes under study.

3. Discussion

3.1. On the Elemental Analysis Results, Calorific Values, and Ash Contents

Regarding the elemental analysis results, upon comparison with those reported for H. rosa-sinensis leaves by Subramanian et al. [34] (C, 40.8%; H, 4.7%; N, 4.9%), significant differences in the C/N ratio could be observed (15.6 in this work vs. 8.4 for H. rosa-sinensis). In turn, such differences in C and N contents explain the differences in the calorific values: 13 vs. 23.2 kJ·g−1. As for the ash content in leaves, the reported content (20.6%) is substantially higher than that found in H. rosa-sinensis (12%). Nonetheless, a comparison with H. cannabinus (C, 38.3%; H, 5.8%; N; 1.7%) [35] results in a closer match, with a C/N ratio of 22.5, a calorific value of 16.68 kJ·g−1 and an ash content of 6.1% (the latter two values are very close to the ones reported for flowers in this work: 16.98 kJ·g−1 and 6.3%, respectively). In view of these similarities with H. cannabinus, a possible valorization for biofuel production may be explored [36,37].

3.2. On the Total Phenol and Flavonoid Contents

The TPC results obtained for H. syriacus flower and leaf extracts (800 and 425 mg GAE/100 mg) are within the ranges reported by Wong et al. [38] for the methanolic extracts of other Hibiscus species: 264‒2420 mg GAE/100 mg for flowers and 301‒2080 mg GAE/100 mg for leaves, respectively, being close to those found for H. rosa-sinensis. The TFC results (315 and 280 mg CE/100 mg for flower and leaf extracts, respectively) were similar to those found after pulsed ultrasonic assisted extraction in methanol of H. cannabinus leaves (290 mg CE/100 mg) [39].

3.3. On the Composition of H. syriacus Extracts

To date, the only analyses available on H. syriacus flower or leaf extracts are those reported by Kim et al. [16] (methanolic formic acid extract of petals, analyzed by 1H-NMR and fast atom bombardment mass spectroscopy, FABMS); by Wei et al. [17] (leaf extract, analyzed by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR); and by Zhang et al. [18] (ethanolic flower extract, analyzed by 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR). However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, no studies based on GC–MS or HPLC are available for H. syriacus, so comparisons with other Hibiscus spp. extracts are provided instead.

Regarding the main identified flower extract phytoconstituents, 1-heptacosanol has also reported in the essential oil of H. sabdariffa flowers by Inikpi et al. [3]. The presence of hexadecanoic and 9,12-octadecadienoic acids and their esters has also been referred in the essential oil of H. sabdariffa by Inikpi et al. [3] and in the flowers of H. tiliaceus by Melecchi et al. [4]. Concerning the presence of 9,12-octadecadienoic acid (in a 4.4%), it is worth noting that it has also been found by Dingjian et al. [5] in the essential oil of H. syriacus. Regarding DDMP-4-one, a principal reducing Maillard compound [40], it has been identified in H. tiliaceus [6] and in H. rosa-sinensis flowers [7]. In relation to nonanoic acid, albeit present in small amounts (0.82%), it had been previously found in the root of H. syriacus [8].

With reference to the phytochemicals found in the leaf extract, coumarin derivatives have been reported in H. rosa-sinensis leaf ethanol and water extracts [9]. α-tocopherol (vitamin E) has been identified in the ethanolic leaf extract of H. sabdariffa by Subhaswaraj et al. [10]. Phytol has been reported in the essential oil of kenaf (H. cannabinus) by Kobaisy et al. [11], in the ethanolic leaf extract of H. sabdariffa [10], and in the aqueous methanol fraction of H. asper leaves by Olivia et al. [12]. In the latter two works, 9,12,15-octadecatrienoic, 9,12-octadecadienoic, and hexadecanoic acids were also found (as in the GC–MS analyses reported herein). β-sitosterol has been identified in H. sabdariffa and H. mutabilis leaves [13,14].

3.4. On the Antimicrobial Activity of H. syriacus Extracts

The antibacterial activity of H. syriacus extracts has been studied by Punasiya et al. [23] against B. cereus, S. aureus, and K. pneumonia; by Mak et al. [41] against S. typhimurium and S. aureus; and by Seyyednejad et al. [42] against B. anthracis, B. cereus, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, L. monocytogenes, S. pyogenes, E. coli, S. typhy, K. pneumonia, and P. aeruginosa, but no assays against E. amylovora and E. vitivora pathogens have been carried out. Regarding the antifungal activity, it has been assayed against C. albicans and S. cerevisiae by Liu et al. [43], and against T. mentagrophytes [8], but no data on Diplodia spp. (or other Botryosphaeriaceae) is available. Hence, a tentative explanation for the observed activity on the basis of the phytoconstituents identified in the extracts is presented.

With respect to the flower extract, 1-heptacosanol has been reported to have antimicrobial and antioxidant activity [44], putative antibacterial activity [45], and significant antifungal activity against all Candida spp. [46]. Nonetheless, its efficacy against the phytopathogens referred herein was variable: moderate against E. amylovora, and high against E. vitivora and D. seriata. As regards other constituents that were not assayed in vitro, hexadecanoic acid and its esters are considered antifungals and antioxidants [47]. The same applies to 1-tetracosanol [48,49], and to the unsaturated linolenic and linoleic fatty acids [50,51]. Moreover, according to Čechovská et al. [40], part of the antioxidant activity of H. syriacus flowers can be ascribed to 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one or DDMP-4-one, and such antioxidant activity is generally associated with antibacterial, antifungal, and antimycotoxigenic biological activities [52].

As for the leaf extract, the neoflavonoid 4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-2-chromanone (or 3,4-dihydro-4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-coumarin), although not included among the coumarins screened by Souza et al. [53] against B. cereus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and S. aureus, nor among those tested by Montagner et al. [54] against C. albicans, A. fumigatus, and F. solani, has shown comparable MIC values to those reported in those works. The lowest efficacy (MIC = 1000 μg·mL−1), observed against E. amylovora, may still be regarded as moderate, and would support the observations of Halbwirth et al. [55] on the antimicrobial activity of flavonoids in pome fruit trees for fire blight control (contrary to the opinion of Flachowsky et al. [56], who considered that the accumulation of flavanones did not appear to reduce fire blight susceptibility in apple). As a potential explanation behind such activity, the efficacy of phytoalexins and flavonoids may be connected to their capability to elude the outer membrane protein TolC and the AcrAB transport system in E. amylovora [57,58].

Regarding other leaf extract constituents, vitamin E is also known to have antimicrobial activity [59,60]. In the present study, vitamin E showed a higher efficacy against E. vitivora (MIC = 500 μg·mL−1) than against E. amylovora and D. seriata (MIC = 750 μg·mL−1). It should also be taken into consideration that the third main compound, phytol, although not assayed in vitro, may also contribute to the observed antimicrobial activity [61].

In relation to the improved antimicrobial activity of the constituents of H. syriacus extracts observed upon conjugation with COS, it may be ascribed to solubility and bioavailability enhancement, as result of an enhanced linkage to negatively charged site-specific binding receptors on the bacterial/fungal membranes. Nevertheless, further research is needed on this specific point, given that no convincing mechanism to explain the synergistic action of above (and other previously reported [62,63]) COS-phytochemical conjugates has been reported to date.

3.5. Limitations of the Study

With regard to the evolution of this work, it should be taken into consideration that—even though the in vitro results are promising—in vivo tests are required in order to evaluate the actual field applicability. While no restrictions apply to ex situ and in vivo tests involving Botryosphaeriaceae fungi (which may be conducted on autoclaved grapevine wood or on grafted grapevine plants artificially inoculated with the fungal pathogen), bioassays with highly virulent Erwinia spp. (for which the best MIC values have been attained and which would be most interesting, given that effective and sustainable control measures are lacking) can only be conducted on suitable host materials under carefully controlled laboratory conditions, given that field studies require authorization, especially in protected zones (according to EU Commission Directive 2003/116/EC of 4 December 2003). Further, even if assays were conducted on artificially inoculated seedlings, it is known that there are sensitivity differences depending on whether it is a natural infection or an artificial inoculation, and also depending on the affected organ (flowers, shoots, unripe fruits, etc.). In addition, comparisons with currently allowed chemical and biological treatment products (viz. Fosetyl-aluminium, laminarin, prohexadione calcium and copper-derivatives; and Aureobasidium pullulans and B. subtilis) would be needed for the cost-effectiveness analysis.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Reagents

Chitosan (CAS 9012-76-4; high MW: 310,000–375,000 Da) was purchased from Hangzhou Simit Chem. & Tech. Co. (Hangzhou, China). NeutraseTM 0.8 L enzyme was supplied by Novozymes A/S (Bagsværd, Denmark). Chitosan oligomers (COS) with a molecular weight of < 2000 Da were prepared according to the procedure reported by Santos-Moriano et al. [64], with the modifications indicated in [65].

1-heptacosanol (CAS 2004-39-9, 98%), 4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-2-chromanone (AldrichCPR T313513), vitamin E (α-tocopherol, CAS 10191-41-0, analytical standard), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH, CAS 1898-66-4), 6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox, CAS 53188-07-1), methanol (CAS 67-56-1, UHPLC, suitable for MS), TSA (tryptic soy agar, CAS 91079-40-2) and TSB (tryptic soy broth, CAS 8013-01-2) were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich Química (Madrid, Spain). PDA (potato dextrose agar) was supplied by Becton Dickinson (Bergen County, NJ, USA). All reagents were used as supplied, without further purification.

4.2. Studied Species

Hibiscus syriacus, colloquially known as ‘Rose of Sharon’ (or ‘Korean Rose’), is one of the 300 species of the genus Hibiscus. Although it was first identified in Syria (as indicated by its name), it is mainly found in south-central and southeast China, India, and much of east Asia. This deciduous shrub grows up to 3 m tall and has flowers with attractive white, pink, purple, lavender, or blue color over a long blooming period, though individual flowers last only a day. The leaves are glabrous, triangular-ovate to rhombic, often 3-lobed (Figure 3, top-center).

Figure 3.

(Top) Leaves and flowers of Hibiscus syriacus; (Bottom) three light purple/purplish white H. syriacus cultivars: ‘Mathilde’, ‘Marina’, and ‘Oiseau Blue’ (from left to right).

About 40 different H. syriacus cultivars, with varying flower color and shape, are commonly cultivated, and many more genotypes exist in different collections [66]. Among the light purple/purplish white cultivars, ‘Mathilde’ (or Blush Satin®), from nursery M. Verweij & Zonen (Boskoop, The Netherlands), released in 1995, is one of the most popular, together with ‘Marina’ cultivar (or Blue Satin®), which looks similar to ‘Oiseau Bleu’, but is said to have a stronger growth (Figure 3, bottom). The purple color has been referred to anthocyanin pigments [67].

A pharmacognostic and pharmacological overview of H. syriacus is provided in the review paper by Punasiya et al. [68].

4.3. Plant Material and Extraction Procedure

Hibiscus syriacus cv. ‘Mathilde’ samples (PP12660, Satin® series) were collected in the full flowering stage, in September 2020, in Llanes (Asturias, Spain). A voucher specimen, identified and authenticated by Prof. J. Ascaso, has been deposited at the herbarium of the Escuela Politécnica Superior de Huesca, Universidad de Zaragoza. Aerial parts from different specimens (n = 20) were thoroughly mixed to obtain (separate) flowers and leaves composite samples. The composite samples were shade-dried, pulverized to fine powder in a mechanical grinder, homogenized, and sieved (1 mm mesh).

The flower samples were mixed (1:20 w/v) with a methanol/water solution (1:1 v/v) and heated in a water bath at 50 °C for 30 min, followed by sonication for 5 min in pulse mode with a 1 min stop for each 2.5 min, using a probe-type ultrasonicator (model UIP1000 hdT; 1000 W, 20 kHz; Hielscher Ultrasonics, Teltow, Germany). The solution was then centrifuged at 9000 rpm for 15 min and the supernatant was filtered through Whatman No. 1 paper. Aliquots were lyophilized for CHNS and FTIR analyses. The extraction procedure for leaf samples was identical.

4.4. Bacterial and Fungal Isolates

The E. amylovora and E. vitivora bacterial isolates were supplied by CECT (Valencia, Spain), with NCPPB 595 and CCUG 21,976 strain designations, respectively. The former was isolated from pear (Pyrus communis L.) in the UK, and the latter from Vitis vinifera var. ‘Sultana’ in Greece. D. seriata (code ITACYL_F098, isolate Y-084-01-01a) was isolated from ‘Tempranillo’ diseased grapevine plants from protected designation of origin (PDO) Toro (Spain) and supplied as lyophilized vials (later reconstituted and refreshed as PDA subcultures) by ITACYL (Valladolid, Spain) [69].

4.5. Physicochemical Characterization

Elemental analyses of dry ground samples were performed with a LECO (St. Joseph, MI, USA) CHNS-932 apparatus (model No. 601-800-500).

The calculation of calorific values from elemental analysis data was carried out according to the following equation [70]: HHV = (0.341 × %C) + (1.322 × %H) − 0.12(%O + %N), where HHV is the heating value for the dry material, expressed in kJ·g−1; and %C, %H, %O, and %N are the mass fractions, expressed in wt.% of dry material.

Thermal gravimetric (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analyses were conducted with a simultaneous TG-DSC2 apparatus (Mettler Toledo; Columbus, OH, USA). Samples were heated from 30 to 600 °C under N2:O2 (4:1) flow (20 cm3·min−1), at a heating rate of 20 °C·min−1.

The infrared vibrational spectra were collected using a Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) Nicolet iS50 Fourier-transform infrared spectrometer, equipped with an in-built diamond attenuated total reflection (ATR) system. A spectral resolution of 1 cm−1 over the 400–4000 cm−1 range was used, taking the interferograms that resulted from co-adding 64 scans.

The hydromethanolic plant extracts were studied by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) at the Research Support Services (STI) at Universidad de Alicante (Alicante, Spain), using a gas chromatograph model 7890A coupled to a quadrupole mass spectrometer model 5975C (both from Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The chromatographic conditions were: 3 injections/vial, injection volume = 1 µL; injector temperature = 280 °C, in splitless mode; and initial oven temperature = 60 °C, 2 min, followed by ramp of 10 °C/min up to a final temperature of 300 °C, 15 min. The chromatographic column used for the separation of the compounds was an Agilent Technologies HP-5MS UI of 30 m length, 0.250 mm diameter, and 0.25 µm film. The mass spectrometer conditions were: temperature of the electron impact source of the mass spectrometer = 230 °C and of the quadrupole = 150 °C; and ionization energy = 70 eV. Test mixture 2 for apolar capillary columns according to Grob (Supelco 86501, Sigma Aldrich Química, Madrid, Spain) and PFTBA tuning standards were used for equipment calibration. NIST11 library was used for compound identification.

Total phenolic content, expressed in gallic acid equivalents (GAE), was determined by using the Folin–Ciocalteau method as described by Dudonné et al. [71], and the total flavonoid content, expressed in catechin equivalents (CE), was evaluated according to Mak et al. [42] through the use of the aluminum chloride method. An Agilent UV-Vis Cary 100 spectrometer was used for the colorimetric quantification.

4.6. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity Assessment

The antibacterial activity was assessed according to CLSI standard M07-11 [72], using the agar dilution method to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). An isolated colony of E. amylovora in TSB liquid medium was incubated at 30 °C for 18 h. Serial dilutions were then conducted, starting from a 108 CFU·mL−1 concentration, to obtain a final inoculum of ~104 CFU·mL−1. Bacterial suspensions were then delivered to the surface of TSA plates, to which the bioactive products had previously been added at concentrations in the 62.5–1500 μg·mL−1 range. Plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. In the case of E. vitivora, the same procedure was followed, albeit at 26 °C. Readings were taken after 24 h. MICs were visually determined in the agar dilutions as the lowest concentrations of the bioactive products at which no bacterial growth was visible. All experiments were run in triplicate, with each replicate consisting of 3 plates per treatment/concentration.

4.7. In Vitro Antifungal Activity Assessment

The antifungal activity of the different treatments was determined using the agar dilution method according to EUCAST standard antifungal susceptibility testing procedures [73], by incorporating aliquots of stock solutions onto the PDA medium to obtain concentrations ranging from 62.5 to 1500 μg·mL−1 range. Mycelial plugs (⌀ = 5 mm), from the margin of 1-week-old PDA cultures of D. seriata, were transferred to plates incorporating the above-mentioned concentrations for each treatment (3 plates per treatment/concentration, with 2 replicates). Plates were incubated at 25 °C in the dark for a week. PDA medium without any amendment was used as the control. Mycelial growth inhibition was estimated according to the formula: ((dc − dt)/dc) × 100, where dc and dt represent the average diameters of the fungal colony of the control and of the treated fungal colony, respectively. Effective concentrations (EC50 and EC90) were estimated using PROBIT analysis in IBM SPSS Statistics v.25 (IBM; Armonk, NY, USA) software.

The level of interaction was determined according to Wadley’s method [74], which is based on the assumption that one component of the mixture can substitute at a constant proportion for the other. The expected effectiveness of the mixture is then directly predictable from the effectiveness of the constituents if the relative proportions are known (as it is in this case). The synergy factor (SF) is estimated as:

where a and b are the proportions of the products A and B in the mixture, respectively, and a + b = 1; EDA and EDB are their equally effective doses; ED(exp) is the expected equally effective dose; and ED(obs) is the equally effective dose observed in the experiment. If SF = 1, the hypothesis of similar joint action (i.e., additivity) can be accepted; if SF > 1, there is synergistic action; and if SF < 1, there is antagonistic action between the two fungicide products.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Given that the homogeneity and homoscedasticity requirements were satisfied (according to Shapiro–Wilk and Levene tests, respectively), the mycelial growth inhibition results for D. seriata were statistically analyzed in IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM, New York, NY, USA) v.25 software using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc comparison of means through Tukey’s test at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

Elemental and thermal analysis data of H. syriacus biomass showed similarities with kenaf, a suitable lignocellulosic feedstock for bioenergy production. The GC–MS analysis of H. syriacus extracts revealed that, apart from fatty alcohols and fatty acids, 4,4,6,8-tetramethyl-3H-chromen-2-one, vitamin E (and its precursor phytol), phytosterols, selinenes, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one, Z-12-pentacosene, and 5-HMF were also present. The antimicrobial activity of H. syriacus extracts was then assayed in vitro. Upon conjugation with COS, flower and leaf extracts led to MIC values of 500 and 375 μg·mL−1, respectively, against E. amylovora; to MIC values of 250 and 500 μg·mL−1, respectively, against E. vitivora; and to EC90 values of 976 and 604 μg·mL−1, respectively, against D. seriata. The strong synergistic behavior observed upon conjugation with COS may be ascribed to solubility and bioavailability enhancement. In view of the observed activity, an alternative valorization approach as a source of bioactive products may be envisaged, although in vivo assays are required to determine the actual operational efficacy.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants10091876/s1, Figure S1: DSC and TG curves of Hibiscus syriacus flowers. Figure S2: DSC and TG curves of Hibiscus syriacus leaves. Figure S3: GC–MS chromatogram of Hibiscus syriacus flower hydromethanolic extract. Figure S4: GC–MS chromatogram of Hibiscus syriacus leaf hydromethanolic extract. Figure S5: Growth inhibition of D. seriata for the conjugate complexes under study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-G. and P.M.-R.; methodology, B.L.-V.; validation, B.L.-V., J.M.-G. and P.M.-R.; formal analysis, P.M.-R.; investigation, E.S.-H., L.B.-D., B.L.-V., J.M.-G. and P.M.-R.; resources, J.M.-G. and P.M.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.-H., L.B.-D., B.L.-V., J.M.-G. and P.M.-R.; writing—review and editing, P.M.-R.; visualization, E.S.-H.; supervision, P.M.-R.; project administration, J.M.-G. and P.M.-R.; and funding acquisition, J.M.-G. and P.M.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Junta de Castilla y León under project VA258P18, with FEDER co-funding; by Cátedra Agrobank under “IV Convocatoria de Ayudas de la Cátedra AgroBank para la transferencia del conocimiento al sector agroalimentario” program; and by Fundación Ibercaja-Universidad de Zaragoza under “Convocatoria Fundación Ibercaja-Universidad de Zaragoza de proyectos de investigación, desarrollo e innovación para jóvenes investigadores” program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to their relevance to be part of an ongoing PhD Thesis.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Pilar Blasco and Pablo Candela at the Servicios Técnicos de Investigación, Universidad de Alicante, for conducting the GC–MS analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Vasudeva, N.; Sharma, S. Biologically active compounds from the genus Hibiscus. Pharm. Biol. 2008, 46, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maganha, E.G.; Halmenschlager, R.D.C.; Rosa, R.M.; Henriques, J.A.P.; Ramos, A.L.L.D.P.; Saffi, J. Pharmacological evidences for the extracts and secondary metabolites from plants of the genus Hibiscus. Food Chem. 2010, 118, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inikpi, E.; Lawal, O.A.; Ogunmoye, A.; Ogunwande, I.A. Volatile composition of the floral essential oil of Hibiscus sabdariffa L. from Nigeria. Am. J. Essent. Oils Nat. Prod. 2014, 2, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Melecchi, M.I.S.; Martinez, M.M.; Abad, F.C.; Zini, P.P.; do Nascimento Filho, I.; Caramão, E.B. Chemical composition of Hibiscus tiliaceus L. flowers: A study of extraction methods. J. Sep. Sci. 2002, 25, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingjian, C.; Dare, Y.; Qingxiu, J.; Hongming, Z.; Hui, L. GC/MS analysis on composition of the essential oil from Hibiscus syriacus L. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2009, 25, 93–96. [Google Scholar]

- Nandagopalan, V.; Gritto, M.J.; Doss, A. GC-MS analysis of bioactive components of the methanol extract of Hibiscus tiliaceus Linn. Asian J. Plant Sci. Res. 2015, 5, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rassem, H.; Nour, A.H.; Yunus, R.M. GC-MS analysis of bioactive constituents of Hibiscus flower. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2017, 11, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, Y.-W.; Jung, J.-Y.; Lee, I.-K.; Kang, S.-Y.; Yun, B.-S. Nonanoic acid, an antifungal compound from Hibiscus syriacus Ggoma. Mycobiology 2012, 40, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rao, K.; Geetha, K.; Banji, D. Quality control study and standardization of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L. flowers and leaves as per WHO guidelines. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2014, 3, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Subhaswaraj, P.; Sowmya, M.; Bhavana, V.; Dyavaiah, M.; Siddhardha, B. Determination of antioxidant activity of Hibiscus sabdariffa and Croton caudatus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae model system. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2728–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobaisy, M.; Tellez, M.R.; Webber, C.L.; Dayan, F.E.; Schrader, K.K.; Wedge, D.E. Phytotoxic and fungitoxic activities of the essential oil of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) leaves and its composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 3768–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivia, N.U.; Goodness, U.C.; Obinna, O.M. Phytochemical profiling and GC-MS analysis of aqueous methanol fraction of Hibiscus asper leaves. Future J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, N.; Kamboj, P. Hibiscus sabdariffa Linn.—An overview. Nat. Prod. Radiance 2009, 8, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Ishikura, N. Anthocyanins and flavonols in the flowers of Hibiscus mutabilis F. versicolor. Kumamoto J. Sci. Biol. 1973, 11, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, E.; Kang, Q.; Zhang, Z. Chemical constituents from the bark of Hibiscus syriacus L. China J. Chin. Mater. Med. 1993, 18, 37–38, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Nonaka, G.-I.; Fujieda, K.; Uemoto, S. Anthocyanidin malonylglucosides in flowers of Hibiscus syriacus. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1503–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.; Ji, X.; Xu, F.; Li, Q.; Yin, H. Chemical constituents from leaves of Hibiscus syriacus and their α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. J. Chin. Med. Mater. 2015, 38, 975–979. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.-R.; Hu, R.-D.; Lu, X.-Y.; Ding, X.-Y.; Huang, G.-Y.; Duan, L.-X.; Zhang, S.-J. Polyphenols from the flower of Hibiscus syriacus Linn ameliorate neuroinflammation in LPS-treated SH-SY5Y cell. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 130, 110517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, B.-S.; Ryoo, I.-J.; Lee, I.-K.; Yoo, I.-D. Hibispeptin B, a novel cyclic peptide from Hibiscus syriacus. Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 15155–15160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, B.-S.; Ryoo, I.-J.; Lee, I.-K.; Park, K.-H.; Choung, D.-H.; Han, K.-H.; Yoo, I.-D. Two bioactive pentacyclic triterpene esters from the root bark of Hibiscus syriacus. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, I.-D.; Yun, B.-S.; Lee, I.-K.; Ryoo, I.-J.; Choung, D.-H.; Han, K.-H. Three naphthalenes from root bark of Hibiscus syriacus. Phytochemistry 1998, 47, 799–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.-S.; Wu, C.-H.; Yang, T.-C.; Yao, C.-W.; Lin, H.-C.; Chang, W.-L. Cytotoxic effect of triterpenoids from the root bark of Hibiscus syriacus. Fitoterapia 2014, 97, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punasiya, R.; Joshi, A.; Sainkediya, K.; Tirole, S.; Joshi, P.; Das, A.; Yadav, R. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of various extracts of Hibiscus syriacus. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2011, 4, 819–822. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, M.; Bokadia, M.; Mehta, B.; Jain, S. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of some seed oils. Fitoterapia 1988, 59, 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- Yokota, M.; Zenda, H.; Kosuge, T.; Yamamoto, T. Studies on isolation of naturally occurring biologically active principles. IV. Antifungal constituents in the bark of Hibiscus syriacus L. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1978, 98, 1508–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.-Q.; Tian, Y.-L.; Wang, L.-M.; Geng, G.-M.; Zhao, W.-J.; Hu, B.-S.; Zhao, Y.-F. Fire blight disease, a fast-approaching threat to apple and pear production in China. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szegedi, E.; Civerolo, E.L. Bacterial diseases of grapevine. Int. J. Hortic. Sci. 2011, 17, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larignon, P.; Fulchic, R.; Cere, L.; Dubos, B. Observation on black dead arm in French vineyards. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2001, 40, 336–342. [Google Scholar]

- Mondello, V.; Songy, A.; Battiston, E.; Pinto, C.; Coppin, C.; Trotel-Aziz, P.; Clement, C.; Mugnai, L.; Fontaine, F. Grapevine trunk diseases: A review of fifteen years of trials for their control with chemicals and biocontrol agents. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1189–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stevens, N.E. Two apple black rot fungi in the United States. Mycologia 2018, 25, 536–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown-Rytlewski, D.E.; McManus, P.S. Virulence of Botryosphaeria dothidea and Botryosphaeria obtusa on apple and management of stem cankers with fungicides. Plant Dis. 2000, 84, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brown, E.A. Botryosphaeria diseases of apple and peach in the Southeastern Unites States. Plant Dis. 1986, 70, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venditti, A. What is and what should never be: Artifacts, improbable phytochemicals, contaminants and natural products. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 34, 1014–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Reddy Ragula, U.B. Pyrolysis kinetics of Hibiscus rosa sinensis and Nerium oleander. Biofuels 2018, 11, 903–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghetti, P.; Ricca, L.; Angelini, L. Thermal analysis of biomass and corresponding pyrolysis products. Fuel 1996, 75, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meryemoğlu, B.; Hasanoğlu, A.; Irmak, S.; Erbatur, O. Biofuel production by liquefaction of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 151, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saba, N.; Jawaid, M.; Hakeem, K.R.; Paridah, M.T.; Khalina, A.; Alothman, O.Y. Potential of bioenergy production from industrial kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) based on Malaysian perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 446–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Lim, Y.; Chan, E. Evaluation of antioxidant, anti-tyrosinase and antibacterial activities of selected Hibiscus species. Ethnobot. Leafl. 2010, 14, 781–796. [Google Scholar]

- Sim, Y.Y.; Jess Ong, W.T.; Nyam, K.L. Effect of various solvents on the pulsed ultrasonic assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from Hibiscus cannabinus L. leaves. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2019, 140, 111708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čechovská, L.; Cejpek, K.; Konečný, M.; Velíšek, J. On the role of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-(4H)-pyran-4-one in antioxidant capacity of prunes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 233, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, Y.W.; Chuah, L.O.; Ahmad, R.; Bhat, R. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis L.) and Cassia (Senna bicapsularis L.) flower extracts. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2013, 25, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seyyednejad, S.M.; Koochak, H.; Darabpour, E.; Motamedi, H. A survey on Hibiscus rosa—Sinensis, Alcea rosea L. and Malva neglecta Wallr as antibacterial agents. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2010, 3, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.; Luyten, W.; Pellens, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Thevissen, K.; Liang, Q.; Cammue, B.P.A.; Schoofs, L.; Luo, G. Antifungal activity in plants from Chinese traditional and folk medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2012, 143, 772–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imada, C. Enzyme inhibitors and other bioactive compounds from marine actinomycetes. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2005, 87, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vambe, M.; Aremu, A.O.; Chukwujekwu, J.C.; Gruz, J.; Luterová, A.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Antibacterial, mutagenic properties and chemical characterisation of sugar Bush (Protea caffra Meisn.): A South African native shrub species. Plants 2020, 9, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarger, M.S.S.; Akhtar, N.; Shreaz, S.; Bhatia, R.; Khatoon, F. Phytochemical analysis and growth inhibiting effects of Salix viminalis L. Leaves against different Candida isolates. Adv. Sci. Lett. 2014, 20, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, M.E.A.; Araújo, S.G.; Morais, M.I.; Sá, N.P.; Lima, C.M.; Rosa, C.A.; Siqueira, E.P.; Johann, S.; Lima, L.A.R.S. Antifungal and antioxidant activity of fatty acid methyl esters from vegetable oils. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2017, 89, 1671–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhat, M.Y.; Talie, M.D.; Wani, A.H.; Lone, B.A. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of essential oil of Rhizopogon species against fungal rot of apple. J. Appl. Biol. Sci. 2020, 14, 296–308. [Google Scholar]

- Vambe, M.; Naidoo, D.; Aremu, A.O.; Finnie, J.F.; Van Staden, J. Bioassay-guided purification, GC-MS characterization and quantification of phyto-components in an antibacterial extract of Searsia lancea leaves. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.J.; Yoo, J.-S.; Lee, T.-G.; Cho, H.-Y.; Kim, Y.-H.; Kim, W.-G. Fatty acid synthesis is a target for antibacterial activity of unsaturated fatty acids. FEBS Lett. 2005, 579, 5157–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Ruan, W.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J. Biological Control of Phytopathogenic Fungi by Fatty Acids. Mycopathologia 2008, 166, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu-Ingok, A.; Devecioglu, D.; Dikmetas, D.N.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Capanoglu, E. Antibacterial, antifungal, antimycotoxigenic, and antioxidant activities of essential oils: An updated review. Molecules 2020, 25, 4711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza, S.M.; Monache, F.D.; Smânia, A. Antibacterial activity of coumarins. Z. Nat. C 2005, 60, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagner, C.; de Souza, S.M.; Groposo, C.; Delle Monache, F.; Smânia, E.F.A.; Smânia, A., Jr. Antifungal activity of coumarins. Z. Nat. C 2008, 63, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbwirth, H.; Fischer, T.C.; Roemmelt, S.; Spinelli, F.; Schlangen, K.; Peterek, S.; Sabatini, E.; Messina, C.; Speakman, J.-B.; Andreotti, C. Induction of antimicrobial 3-deoxyflavonoids in pome fruit trees controls fire blight. Z. Nat. C 2003, 58, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flachowsky, H.; Halbwirth, H.; Treutter, D.; Richter, K.; Hanke, M.-V.; Szankowski, I.; Gosch, C.; Stich, K.; Fischer, T.C. Silencing of flavanone-3-hydroxylase in apple (Malus× domestica Borkh.) leads to accumulation of flavanones, but not to reduced fire blight susceptibility. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 51, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrancken, K.; Holtappels, M.; Schoofs, H.; Deckers, T.; Valcke, R. Pathogenicity and infection strategies of the fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora in Rosaceae: State of the art. Microbiology 2013, 159, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, D.; Wang, Z.; James, N.R.; Voss, J.E.; Klimont, E.; Ohene-Agyei, T.; Venter, H.; Chiu, W.; Luisi, B.F. Structure of the AcrAB–TolC multidrug efflux pump. Nature 2014, 509, 512–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Salih, D.A.A.K.; Aziz, F.M.; Mshimesh, B.A.R.; Jehad, M.T. Antibacterial effects of vitamin E: In vitro study. J. Biotechnol. Res. Cent. 2013, 7, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, R.; Thomas, L. Combination of fluconazole and alpha-tocopherol in the treatment of yellow nail syndrome. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2009, 8, 276–278. [Google Scholar]

- Pejin, B.; Savic, A.; Sokovic, M.; Glamoclija, J.; Ciric, A.; Nikolic, M.; Radotic, K.; Mojovic, M. Further in vitro evaluation of antiradical and antimicrobial activities of phytol. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzón-Durán, L.; Langa-Lomba, N.; González-García, V.; Casanova-Gascón, J.; Martín-Gil, J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E.; Martín-Ramos, P. On the applicability of chitosan oligomers-amino acid conjugate complexes as eco-friendly fungicides against grapevine trunk pathogens. Agronomy 2021, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langa-Lomba, N.; Buzón-Durán, L.; Martín-Ramos, P.; Casanova-Gascón, J.; Martín-Gil, J.; Sánchez-Hernández, E.; González-García, V. Assessment of conjugate complexes of chitosan and Urtica dioica or Equisetum arvense extracts for the control of grapevine trunk pathogens. Agronomy 2021, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Moriano, P.; Fernandez-Arrojo, L.; Mengibar, M.; Belmonte-Reche, E.; Peñalver, P.; Acosta, F.N.; Ballesteros, A.O.; Morales, J.C.; Kidibule, P.; Fernandez-Lobato, M.; et al. Enzymatic production of fully deacetylated chitooligosaccharides and their neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2017, 36, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buzón-Durán, L.; Martín-Gil, J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E.; Ruano-Rosa, D.; Revuelta, J.L.; Casanova-Gascón, J.; Ramos-Sánchez, M.C.; Martín-Ramos, P. Antifungal agents based on chitosan oligomers, ε-polylysine and Streptomyces spp. secondary metabolites against three Botryosphaeriaceae species. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Laere, K.; Van Huylenbroeck, J.M.; Van Bockstaele, E. Interspecific hybridisation between Hibiscus syriacus, Hibiscus sinosyriacus and Hibiscus paramutabilis. Euphytica 2007, 155, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, H.F. Our hardy Hibiscus species as ornamentals. Econ. Bot. 1970, 24, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punasiya, R.; Devre, K.; Pillai, S. Pharmacognostic and pharmacological overview on Hibiscus syriacus L. Int. J. Pharm. Life Sci. 2014, 5, 3617–3621. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.T.; Cobos, R. Identification of fungi associated with grapevine decline in Castilla y León (Spain). Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2007, 46, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Talwalkar, A.T. IGT/DOE Coal-Conversion Systems Technical Data Book; Institute of Gas Technology: Chicago, IL, USA, 1981; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Dudonné, S.; Vitrac, X.; Coutière, P.; Woillez, M.; Mérillon, J.M. Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 1768–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 11th ed.; CLSI Standard M07; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Hope, W. EUCAST technical note on the EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.2: Method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts EDef 7.2 (EU-CAST-AFST). Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, E246–E247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Levy, Y.; Benderly, M.; Cohen, Y.; Gisi, U.; Bassand, D. The joint action of fungicides in mixtures: Comparison of two methods for synergy calculation. EPPO Bull. 1986, 16, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).