Fungal Pathogens and Seed Storage in the Dry State

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Seed-Borne Fungi

2.1. Types of Seed-Borne Fungi

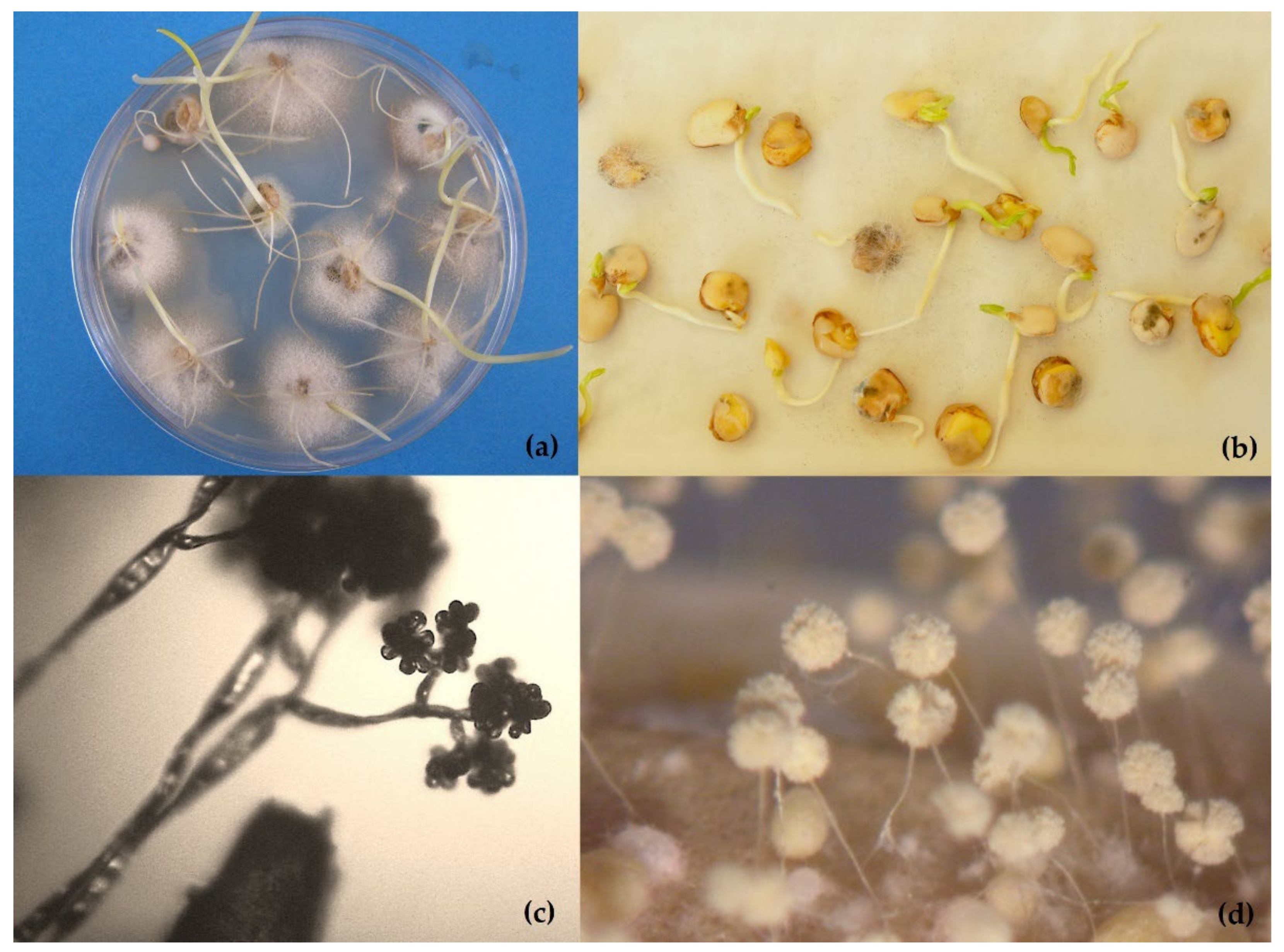

- (a)

- Seed-transmitted pathogens can be categorized into two broad groups—biotrophs and necrotrophs—[1]. Biotrophs are obligate parasitic organisms that develop specialized infection structures (haustoria) and live on nutrients provided by the living host. They have a narrow host range and usually cannot be grown in pure culture. Necrotrophic organisms destroy the host cells and then live saprophytically on the dead tissues. They kill their hosts by secreting toxins or cell-wall degrading enzymes and eliciting reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [16]. Necrotrophs frequently have a wide host range and can be grown in pure culture.

- (b)

- Seed fungi that reduce seed and grain quality are commonly divided into two ecological general groups—field fungi and storage fungi—depending on whether the infection occurs mostly before or after harvest. Field fungi invade seeds before harvest when seeds are developing on mother plants in the field or after they have matured. In order to grow, these fungi require a seed moisture content in equilibrium with a relative humidity of at least 90–95%. This would correspond to a “water activity” (aw) equivalent to 0.90–0.95. Water activity is a criterion often preferred to seed moisture content and corresponds to the relative humidity of the air in equilibrium with the seeds (divided by 100) [6]. Alternaria, Fusarium, Cladosporium or Helminthosporium (Bipolaris/Deschlera) are very common field fungi [7]. Damage caused by field fungi usually occurs before harvest and does not increase in storage. Field fungi may discolor seeds, cause the weakening or the death of embryos and generate compounds toxic to man and animals. Some of them can also be transmitted and cause diseases on new seedlings or growing plants.

- (c)

- A large number of seed-borne fungi have never been shown to cause damage as a result of their presence in seeds [36]. In fact, many of them have a positive relationship with plants, such as some endophytes of grasses [37,38]. Others compete with pathogenic microorganisms [39,40,41]. Finally, some fungi, such as Trichoderma spp., are even used as seed treatments to control diseases enhancing plant growth [42]. Although beyond the scope of this review, seed microbiome is an emerging field of study that should be investigated in depth [43].

2.2. Paths of Infection, Inoculum Location and Disease Transmission

3. Seed Health Methods: An Outline

3.1. Conventional Methods

3.2. Serological and Molecular Methods

3.3. Other Methods

4. Fungi in Seed Germplasm Collections

4.1. Effect of Cold and Dry Storage on Fungi Longevity

4.2. Risk of Pathogen Dissemination

4.3. Effects of Fungi on Seed Longevity

5. Procedures to Reduce Harmful Effects of Fungi in Gene Banks

- Material acquisition:

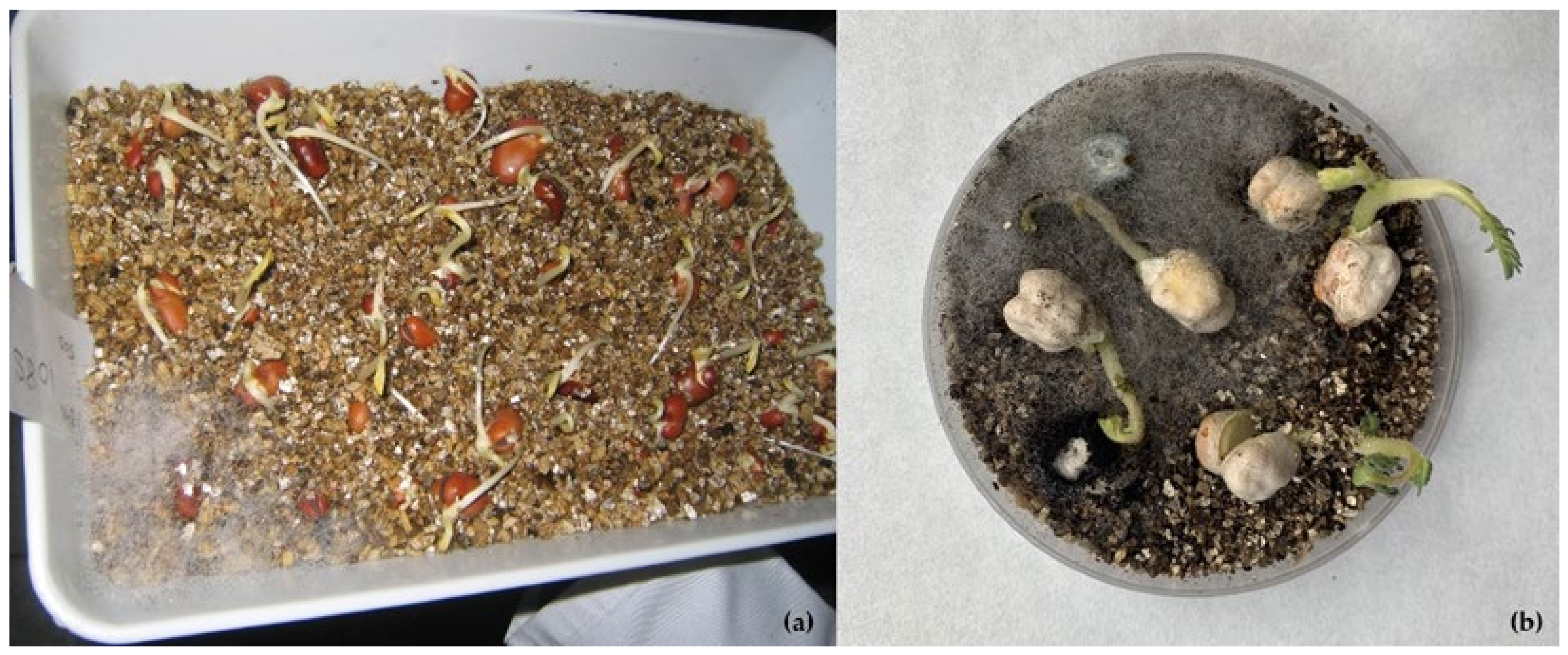

- Regeneration/Multiplication:

- Seed processing:

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maude, R.B. Seedborne Diseases and Their Control: Principles and Practice; CAB International: Warwick, UK, 1996; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Elmer, W.H. Seeds as vehicles for pathogen importation. Biol. Invasions 2001, 3, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergaard, P. Seed Pathology Vols. 1 and 2; The MacMillan Press: London, UK, 1977; p. 839. [Google Scholar]

- Plucknett, D.L. Quarantine and the exchange of crop genetic resources. Bioscience 1989, 39, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.L.; Cuervo, M.; Kreuze, J.F.; Muller, G.; Kulkarni, G.; Kumari, S.G.; Massart, S.; Mezzalama, M.; Alakonya, A.; Muchugi, A. Phytosanitary interventions for safe global germplasm exchange and the prevention of transboundary pest spread: The role of CGIAR germplasm health units. Plants 2021, 10, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magan, N.; Sanchis, V.; Aldred, D. Role of spoilage fungi in seed deterioration. In Fungal Biotechnology in Agricultural, Food and Environmental Applications; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 311–323. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; Meronuck, R.A. Quality Maintenance in Stored Grains and Seeds; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1986; p. 152. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.J.; Ryu, D. Worldwide occurrence of mycotoxins in cereals and cereal-derived food products: Public health perspectives of their co-occurrence. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 7034–7051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desjardins, A.E. Fusarium Mycotoxins: Chemistry, Genetics, and Biology; American Phytopathological Society Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pickova, D.; Ostry, V.; Toman, J.; Malir, F. Aflatoxins: History, significant milestones, recent data on their toxicity and ways to mitigation. Toxins 2021, 13, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Stamatelopoulou, E.; Varzakas, T. Advances in occurrence, importance, and mycotoxin control strategies: Prevention and detoxification in foods. Foods 2020, 9, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.J. An Annotated List of Seed-Borne Diseases, 4th ed.; International Seed Testing Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, J.R.; Diekmann, M.; Berjak, P. Forest Tree Seed Health; IPGRI Technical Bulletin Nº. 6; International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 2002; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, D.J.; Hibbett, D.S.; Lutzoni, F.; Spatafora, J.W.; Vilgalys, R. The search for the fungal tree of life. Trends Microbiol. 2009, 17, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalier-Smith, T. What are Fungi? In The Mycota, Systematics and Evolution; McLaughlin, D.J., McLaughlin, E.G., Lemke, P.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; Volume 7A, pp. 3–37. [Google Scholar]

- Horbach, R.; Navarro-Quesada, A.R.; Knogge, W.; Deising, H.B. When and how to kill a plant cell: Infection strategies of plant pathogenic fungi. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfect, S.E.; Green, J.R. Infection structures of biotrophic and hemibiotrophic fungal plant pathogens. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2001, 2, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, J.S.; Owen, B.; Higgins, V.J. The role of the jasmonate response in plant susceptibility to diverse pathogens with a range of lifestyles. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münch, S.; Lingner, U.; Floss, D.S.; Ludwig, N.; Sauer, N.; Deising, H.B. The hemibiotrophic lifestyle of Colletotrichum species. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, C.W.; Yates, I.E. Endophytic root colonization by Fusarium species: Histology, plant interactions, and toxicity. In Microbial Root Endophytes; Schulz, B.J.E., Boyle, C.J.C., Sieber, T.N., Eds.; Springer-Verlag Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; Schäfer, P.; Hückelhoven, R.; Langen, G.; Baltruschat, H.; Stein, E.; Nagarajan, S.; Kogel, K.H. Bipolaris sorokiniana, a cereal pathogen of global concern: Cytological and molecular approaches towards better control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2002, 3, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, N.P.; Mehrabi, R.; Lütken, H.; Haldrup, A.; Kema, G.H.; Collinge, D.B.; Jørgensen, H.J.L. Role of hydrogen peroxide during the interaction between the hemibiotrophic fungal pathogen Septoria tritici and wheat. New Phytol. 2007, 174, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balducchi, A.; McGee, D. Environmental factors influencing infection of soybean seeds by Phomopsis and Diaporthe species during seed maturation. Plant Dis. 1987, 71, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuite, J.; Shaner, G.; Everson, R.J. Wheat scab in soft red winter wheat in Indiana in 1986 and its relation to some quality measurements. Plant Dis. 1990, 74, 959–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, W.J. Fungi associated with the seeds of commercial lentils from the US Pacific Northwest. Plant Dis. 1992, 76, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.; Clarke, J.; DePauw, R.; Irvine, R.; Knox, R. Black point and red smudge in irrigated durum wheat in southern Saskatchewan in 1990–1992. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1994, 16, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-del-Bosque, L. Impact of agronomic factors on aflatoxin contamination in preharvest field corn in northeastern Mexico. Plant Dis. 1996, 80, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Munkvold, G. Effects of planting date and environmental factors on Fusarium ear rot symptoms and fumonisin B1 accumulation in maize grown in six North American locations. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploper, L.; Abney, T.; Roy, K. Influence of soybean genotype on rate of seed maturation and its impact on seedborne fungi. Plant Dis. 1992, 76, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, G.; Kushalappa, A.; Choo, T.; Dion, Y.; Rioux, S. Differential metabolic response of barley genotypes, varying in resistance, to trichothecene-producing and-nonproducing (tri5−) isolates of Fusarium graminearum. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Palmero, D.; Cara, M.D.; Cruz, A.; González Jaén, M. Fungal microbiota associated with black point disease on durum wheat. Effects of irrigation, nitrogen fertilization and cultivar. ITEA 2012, 108, 343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Meronuck, R. The significance of fungi in cereal grains. Plant Dis. 1987, 71, 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Duncan, H.; Hamilton, P. Planting date, harvest date, and irrigation effects on infection and aflatoxin production by Aspergillus flavus in field corn. Phytopathology 1981, 17, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehan, V.; Mayee, C.; Jayanthi, S.; McDonald, D. Preharvest seed infection by Aspergillus flavus group fungi and subsequent aflatoxin contamination in groundnuts in relation to soil types. Plant Soil 1991, 136, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betran, F.; Isakeit, T. Aflatoxin accumulation in maize hybrids of different maturities. Agron. J. 2004, 96, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, D.C. Seed pathology: Its place in modern seed production. Plant Dis. 1981, 65, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabalgogeazcoa, I. Fungal endophytes and their interaction with plant pathogens: A review. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2008, 6, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bastias, D.A.; Martínez-Ghersa, M.A.; Ballaré, C.L.; Gundel, P.E. Epichloë fungal endophytes and plant defenses: Not just alkaloids. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rheeder, J.; Marasas, W.; Van Wyk, P. Fungal associations in corn kernels and effects on germination. Phytopathology 1990, 80, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zummo, N.; Scott, G. Interaction of Fusarium moniliforme and Aspergillus flavus on kernel infection and aflatoxin contamination in maize ears. Plant Dis. 1992, 76, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo-Prieto, S.; Campelo, M.; Lorenzana, A.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Reinoso, B.; Gutiérrez, S.; Casquero, P. Antifungal activity and bean growth promotion of Trichoderma strains isolated from seed vs. soil. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 158, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastouri, F.; Björkman, T.; Harman, G.E. Seed treatment with Trichoderma harzianum alleviates biotic, abiotic, and physiological stresses in germinating seeds and seedlings. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 1213–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samreen, T.; Naveed, M.; Nazir, M.Z.; Asghar, H.N.; Khan, M.I.; Zahir, Z.A.; Kanwal, S.; Jeevan, B.; Sharma, D.; Meena, V.S.; et al. Seed associated bacterial and fungal endophytes: Diversity, life cycle, transmission, and application potential. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 168, 104191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, V.K.S.; Sinclair, J.B. Principles of Seed Pathology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Nallathambi, P.; Umamaheswari, C.; Lal, S.K.; Manjunatha, C.; Berliner, J. Mechanism of seed transmission and seed infection in major agricultural crops in India. In Seed-Borne Diseases of Agricultural Crops: Detection, Diagnosis & Management; Kumar, R., Gupta, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 749–791. [Google Scholar]

- Gagic, M.; Faville, M.J.; Zhang, W.; Forester, N.T.; Rolston, M.P.; Johnson, R.D.; Ganesh, S.; Koolaard, J.P.; Easton, H.S.; Hudson, D. Seed transmission of Epichloë endophytes in Lolium perenne is heavily influenced by host genetics. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, J.; Zhang, G.; Yu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, W.; Zhao, J. The colonization process of sunflower by a green fluorescent protein-tagged isolate of Verticillium dahliae and its seed transmission. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1772–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halfon-Meiri, A.; Rylski, I. Internal mold caused in sweet pepper by Alternaria alternata: Fungal ingress. Phytopathology 1983, 73, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, S.; Koudsieh, S.; Najjar, D. Improved method for detecting Ustilago nuda in barley seed. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2014, 47, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G. Mechanisms of seed infection and pathogenesis. Phytopathology 1983, 73, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, G.; Pfleger, F. Pathogenicity and infection sites of Aspergillus species in stored seeds. Phytopathology 1974, 64, 1339–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, A. Opening addresses. Seed Sci. Technol. 1983, 11, 464–475. [Google Scholar]

- Doyer, L.C. Manual for the Determination of Seed-Borne Diseases; International Seed Testing Association: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1938; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.B.; Kongsdal, O. Common Laboratory Seed Health Testing Methods for Detecting Fungi; International Seed Testing Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 2003; p. 399. [Google Scholar]

- ISTA. Chapter 7: Seed Health Testing. In ISTA Rules 2022; International Seed Testing Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.seedtest.org/en/international-rules-for-seed-testing/chapter-7-seed-health-testing-product-1010.html (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Kumar, R.; Gupta, A.; Srivastava, S.; Devi, G.; Singh, V.K.; Goswami, S.K.; Gurjar, M.S.; Aggarwal, R. Diagnosis and detection of seed-borne fungal phytopathogens. In Seed-Borne Diseases of Agricultural Crops: Detection, Diagnosis & Management; Kumar, R., Gupta, A., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 107–142. [Google Scholar]

- Werres, S.; Steffens, C. Immunological techniques used with fungal plant pathogens: Aspects of antigens, antibodies and assays for diagnosis. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1994, 125, 615–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerberg, C.; Gripwall, E.; Wiik, L. Detection and quantification of seed-borne Septoria nodorum in naturally infected grains of wheat with polyclonal ELISA. Seed Sci. Technol. 1995, 23, 609–615. [Google Scholar]

- Walcott, R.R. Detection of seedborne pathogens. HortTechnology 2003, 13, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afouda, L.; Wolf, G.; Wydra, K. Development of a sensitive serological method for specific detection of latent infection of Macrophomina phaseolina in cowpea. J. Phytopathol. 2009, 157, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, J.M.; French, R. The polymerase chain reaction and plant disease diagnosis. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1993, 31, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISF. International Seed Federation. Available online: https://worldseed.org/our-work/seed-health (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Prasannakumar, M.; Parivallal, P.B.; Pramesh, D.; Mahesh, H.; Raj, E. LAMP-based foldable microdevice platform for the rapid detection of Magnaporthe oryzae and Sarocladium oryzae in rice seed. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, G.; Kapoor, R. Nested PCR assay for specific and sensitive detection of Alternaria carthami. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, V.; Murolo, S.; Romanazzi, G. Diagnostic methods for detecting fungal pathogens on vegetable seeds. Plant Pathol. 2016, 65, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Rai, A.; Dubey, S.C.; Akhtar, J.; Kumar, P. DNA barcode, multiplex PCR and qPCR assay for diagnosis of pathogens infecting pulse crops to facilitate safe exchange and healthy conservation of germplasm. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 2575–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walcott, R.; Gitaitis, R.; Langston, D. Detection of Botrytis aclada in onion seed using magnetic capture hybridization and the polymerase chain reaction. Seed Sci. Technol. 2004, 32, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecchia, S.; Caggiano, B.; Da Lio, D.; Cafà, G.; Le Floch, G.; Baroncelli, R. Molecular detection of the seed-borne pathogen Colletotrichum lupini targeting the hyper-variable IGS region of the ribosomal cluster. Plants 2019, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hariharan, G.; Prasannath, K. Recent advances in molecular diagnostics of fungal plant pathogens: A mini review. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 600234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, K.-S.; Wechter, W.; Somai, B.; Walcott, R.; Keinath, A. An improved real-time PCR system for broad-spectrum detection of Didymella bryoniae, the causal agent of gummy stem blight of cucurbits. Seed Sci. Technol. 2010, 38, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkvold, G.P. Seed pathology progress in academia and industry. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009, 47, 285–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Wurzbacher, C.; Baldrian, P.; Tedersoo, L. Mycobiome diversity: High-throughput sequencing and identification of fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragona, M.; Haegi, A.; Valente, M.T.; Riccioni, L.; Orzali, L.; Vitale, S.; Luongo, L.; Infantino, A. New-Generation Sequencing technology in diagnosis of fungal plant pathogens: A dream comes true? J. Fungi 2022, 8, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Huhndorf, S.; Robert, V.; Spouge, J.L.; Levesque, C.A.; Chen, W.; Bolchacova, E.; Voigt, K.; Crous, P.W. Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6241–6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lievens, B.; Thomma, B.P. Recent developments in pathogen detection arrays: Implications for fungal plant pathogens and use in practice. Phytopathology 2005, 95, 1374–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Choudhary, P.; Singh, B.N.; Chakdar, H.; Saxena, A.K. DNA barcoding of phytopathogens for disease diagnostics and bio-surveillance. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPPO. PM 7/129 (2) DNA barcoding as an identification tool for a number of regulated pests. EPPO Bull. 2021, 51, 100–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.; Gopal, J.; Muthu, M. A consolidative synopsis of the MALDI-TOF MS accomplishments for the rapid diagnosis of microbial plant disease pathogens. Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 156, 116713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, M.K.; Sedaghatjoo, S.; Maier, W.; Killermann, B.; Niessen, L. Discrimination of Tilletia controversa from the T. caries/T. laevis complex by MALDI-TOF MS analysis of teliospores. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 1257–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França-Silva, F.; Rego, C.H.Q.; Gomes-Junior, F.G.; Moraes, M.H.D.; Medeiros, A.D.; Silva, C.B. Detection of Drechslera avenae (Eidam) Sharif [Helminthosporium avenae (Eidam)] in black oat seeds (Avena strigosa Schreb) using multispectral imaging. Sensors 2020, 20, 3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekmann, M. Seed health testing and treatment of germplasm at the International Center for Agricultural Reseach in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). Seed Sci. Technol. 1988, 16, 405–417. [Google Scholar]

- Higley, P.; McGee, D.; Burris, J. Development of methodology for non-destructive assay of bacteria, fungi and viruses in seeds of large-seeded field crops. Seed Sci. Technol. 1993, 21, 399–409. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.J.; Brough, J.; Chakrabarty, S. Non-destructive seed testing for bacterial pathogens in germplasm material. Seed Sci. Technol. 2002, 30, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R. Longevity studies with wheat seed and certain seed-borne fungi. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1958, 38, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiewióra, B. Long-time storage effect on the seed heath of spring barley grain. Plant Breed. Seed Sci. 2009, 59, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, N.K.; Hanson, J.; Dulloo, M.E.; Ghosh, K.; Nowell, A. Manual of Seed Handling in Genebanks; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2006; p. 147. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Genebank Standards for Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; p. 166. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, P. Pathogen viability on seed in deep freeze storage. Seed Sci. Technol. 1987, 15, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, W.J.; Hannan, R.M. Incidence of seedborne Ascochyta lentis in lentil germplasm. Phytopathology 1986, 76, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzies, J.; Nielsen, J.; Thomas, P. The conservation of Ustilago tritici in infected seed. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 32, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodal, G.; Asdal, Å. Longevity of plant pathogens in dry agricultural seeds during 30 years of storage. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, J.; Tekauz, A.; Woods, S. Effect of storage on viability of Fusarium head blight-affected spring wheat seed. Plant Dis. 1997, 81, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaiser, W.; Stanwood, P.; Hannan, R. Survival and pathogenicity of Ascochyta fabae f. sp. lentis in lentil seeds after storage for four years at 20 to 196 °C. Plant Dis. 1989, 73, 762–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Girish, A.; Rao, N.; Bramel, P.; Chandra, S. Survival of Rhizoctonia bataticola in groundnut seed under different storage conditions. Seed Sci. Technol. 2003, 31, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunfer, B.M. Survival of Septoria nodorum in wheat seed. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1981, 77, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, J.; Woods, S.; Turkington, T.; Tekauz, A. Effect of heat treatment to control Fusarium graminearum in wheat seed. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2005, 27, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.S.; Colyer, P.D. Dry heat and hot water treatments for disinfesting cottonseed of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.; Meng, S.; Xie, X.; Chai, A.; Li, B. Dry heat treatment reduces the occurrence of Cladosporium cucumerinum, Ascochyta citrullina, and Colletotrichum orbiculare on the surface and interior of cucumber seeds. Hortic. Plant J. 2016, 2, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erley, D.; Mycock, D.; Berjak, P. The elimination of Fusarium moniliforme Sheldon infection in maize caryopses by hot water treatments. Seed Sci. Technol. 1997, 25, 485–501. [Google Scholar]

- Hoekstra, F.A. Pollen and spores: Desiccation tolerance in pollen and the spores of lower plants and fungi. In Desiccation and Survival in Plants: Drying without Dying; Pritchard, H.W., Black, M., Eds.; CABI Publishing: Wallington, UK, 2002; pp. 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, T.; Ellis, R.; Moore, D. Development of a model to predict the effect of temperature and moisture on fungal spore longevity. Ann. Bot. 1997, 79, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ellis, R.; Roberts, E. Improved equations for the prediction of seed longevity. Ann. Bot. 1980, 45, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitell, L. Effects of relative humidity on viability of conidia of Aspergilli. Am. J. Bot. 1958, 45, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, T.J.; Holloway, G.; Hill, G.A.; Pugsley, T.S. Effect of conditions and protectants on the survival of Penicillium bilaiae during storage. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2006, 16, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.; Martín, I.; Guerrero, M.; Palmero, D. Microbiótica Fúngica y Viabilidad de Semillas de Judía, Sometidas a Diferentes Tratamientos de Desecación; Actas Asociación Española de Leguminosas: Pontevedra, Spain, 2012; pp. 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Hume, D.; Schmid, J.; Rolston, M.; Vijayan, P.; Hickey, M. Effect of climatic conditions on endophyte and seed viability in stored ryegrass seed. Seed Sci. Technol. 2011, 39, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheplick, G.P. Persistence of endophytic fungi in cultivars of Lolium perenne grown from seeds stored for 22 years. Am. J. Bot. 2017, 104, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gundel, P.E.; Martínez-Ghersa, M.A.; Garibaldi, L.A.; Ghersa, C.M. Viability of Neotyphodium endophytic fungus and endophyte-infected and noninfected Lolium multiflorum seeds. Botany 2009, 87, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Second Report on the State of the World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture; Commision on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega, I.L.; Halewood, M.; Abberton, M.; Amri, A.; Angarawai, I.I.; Anglin, N.; Blümmel, M.; Bouman, B.; Campos, H.; Costich, D. CGIAR operations under the plant treaty framework. Crop Sci. 2019, 59, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisey, P.; Day-Rubenstein, K. Using Crop Genetic Resources to Help Agriculture Adapt to Climate Change: Economics and Policy, EIB-139; USDA-Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2015.

- Leppik, E.E. Gene centers of plants as sources of disease resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1970, 8, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, W.J. Inter-and intranational spread of ascochyta pathogens of chickpea, faba bean, and lentil. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 1997, 19, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faiad, M.; Wetzel, M.; Salomao, A.; Cunha, R. Evaluation of fungi in seed germplasm before long term storage. Seed Sci. Technol. 1996, 24, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Girish, A.; Singh, S.; Chakrabarty, S.; Prasada Rao, R.; Surender, A.; Varaprasad, K.; Bramel, P. Seed microflora of five ICRISAT mandate crops. Seed Sci. Technol. 2001, 29, 429–443. [Google Scholar]

- Asaad, S.; Abang, M.M. Seed-borne pathogens detected in consignments of cereal seeds received by the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA), Syria. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2009, 55, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Akhtar, J.; Kandan, A.; Kumar, P.; Chand, D.; Maurya, A.K.; Agarwal, P.C.; Dubey, S.C. Risk of pathogens associated with plant germplasm imported into India from various countries. Indian Phytopathol. 2018, 71, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frison, E.; Bos, L.; Hamilton, R.; Mathur, S.; Taylor, J. FAO/IBPGR Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Legume Germplasm; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, International Board for Plant Genetic Resources: Rome, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, M.; Putter, C.A.J. FAO/IPGRI Technical Guidelines for the Safe Movement of Small Grain Temperate Cereals. Nº 14; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez, Y.; Smale, M.; Jamora, N.; Hossain, M.; Kumar, P.L. The Economic Contribution of CGIAR Germplasm Health Units to International Agricultural Research: The Example of Rice Blast Disease in Bangladesh; Genebank Impacts Working paper Nº 15; CGIAR Genebank Platform, IRRI, and the Crop Trust: Lima, Peru, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B.; Pardey, P.G.; Wright, B. Saving Seeds: The Economics of Conserving Crop Genetic Resources Ex Situ in the Future Harvest Centres of the CGIAR; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- López Noriega, I.; Galluzzi, G.; Halewood, M.; Vernooy, R.; Bertacchini, E.; Gauchan, D.; Welch, E. Flows under Stress: Availability of Plant Genetic Resources in Times of Climate and Policy Change; Working paper 18, CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change; Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, J. Phomopsis seed decay of soybeans: A prototype for studying seed disease. Plant Dis. 1993, 77, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.; Dutta, A.K.; Pradhan, P. ‘Bipolaris sorokiniana’(Sacc.) Shoem.: The most destructive wheat fungal pathogen in the warmer areas. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2011, 5, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Haile, J.K.; N’Diaye, A.; Walkowiak, S.; Nilsen, K.T.; Clarke, J.M.; Kutcher, H.R.; Steiner, B.; Buerstmayr, H.; Pozniak, C.J. Fusarium head blight in durum wheat: Recent status, breeding directions, and future research prospects. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, A.C.; Gundel, P.E.; Seal, C.E.; Ghersa, C.M.; Martínez-Ghersa, M.A. The negative effect of a vertically-transmitted fungal endophyte on seed longevity is stronger than that of ozone transgenerational effect. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 175, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J.J.; Pryor, B.M.; Davis, R.M. Alternaria diseases of carrot. Plant Dis. 2004, 88, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Saharan, G.S.; Mehta, N.; Meena, P.D.; Dayal, P. Alternaria Diseases of Crucifers: Biology, Ecology and Disease Management; Springer: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rude, S.; Duczek, L.; Seidle, E. The effect of Alternaria brassicae, Alternaria raphani and Alternaria alternata on seed germination of Brassica rapa canola. Seed Sci. Technol. 1999, 27, 795–798. [Google Scholar]

- Tekauz, A.; McCallum, B.; Gilbert, J. Fusarium head blight of barley in western Canada. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2000, 22, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, K. Influence of harvest date and geographical location on kernel symptoms, fungal infestation and embryo viability of malting barley. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 113, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulajić, A.; Djekić, I.; Lakić, N.; Krstić, B. The presence of Alternaria spp. on the seed of Apiaceae plants and their influence on seed emergence. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2009, 61, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Ning, H.; Li, W.; Bai, Y.; Li, Y. Evaluation and management of fungal-infected carrot seeds. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, J.; Van Tongeren, C.; Groenenboom-de Haas, B.; Van Hoof, R.; Driessen, R.; Van Der Heijden, L. Epidemiology of dark leaf spot caused by Alternaria brassicicola and A. brassicae in organic seed production of cauliflower. Plant Pathol. 2010, 59, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Ghafoor, A.; Bashir, M. Effect of seed borne pathogens on seed longevity in chickpea and cowpea under storage at 25 °C to 18 °C. Seed Sci. Technol. 2006, 34, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Mishra, N.; Sahu, K. Effect of some fungi associated with farmers’ saved groundnut seeds on seed quality. J. Plant Prot. Environ. 2014, 11, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.K.; Basandrai, A.K. Will Macrophomina phaseolina spread in legumes due to climate change? A critical review of current knowledge. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundel, P.E.; Martinez-Ghersa, M.A.; Ghersa, C.M. Threshold modelling Lolium multiflorum seed germination: Effects of Neotyphodium endophyte infection and storage environment. Seed Sci. Technol. 2012, 40, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, J.; Bolkan, H.; Shi, Q. The mycoflora of perennial ryegrass seed and their effects on the germination and seedling vigour. Seed Sci. Technol. 2006, 34, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, I.; Arnold, J.; Hinton, D.; Basinger, W.; Walcott, R. Fusarium verticillioides induction of maize seed rot and its control. Can. J. Bot. 2003, 81, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjorin, S.T.; Makun, H.A.; Adesina, T.; Kudu, I. Effects of Fusarium verticilloides, its metabolites and neem leaf extract on germination and vigour indices of maize (Zea mays L.). Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 2402–2406. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, A.L.; Shu, X.; OBrian, G.R.; Nielsen, D.M.; Woloshuk, C.P.; Boston, R.S.; Payne, G.A. Aspergillus flavus infection induces transcriptional and physical changes in developing maize kernels. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, C.D.S.; Barrocas, E.N.; Machado, J.D.C.; Silva, U.A.D.; Dias, I.E. Effects of Stenocarpella maydis in seeds and in the initial development of corn. J. Seed Sci. 2014, 36, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekle, S.; Skinnes, H.; Bjørnstad, Å. The germination problem of oat seed lots affected by Fusarium head blight. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2013, 135, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, A.S.; Muhammad, I.; Safdar, A.A.; Raza, M.M.; Zubair, A.N. Effect of Alternaria sp. on seed germination in rapeseed, and its control with seed treatment. J. Cereals Oilseeds 2020, 11, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gopalakrishnan, C.; Kamalakannan, A.; Valluvaparidasan, V. Effect of seed-borne Sarocladium oryzae, the incitant of rice sheath rot on rice seed quality. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2010, 50, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanck, A.A.; Meneses, P.R.; Farias, C.R.; Funck, G.R.; Maia, A.H.; Del Ponte, E.M. Bipolaris oryzae seed borne inoculum and brown spot epidemics in the subtropical lowland rice-growing region of Brazil. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 142, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yago, J.; Roh, J.; Bae, S.; Yoon, Y.; Kim, H.; Nam, M. The effect of seed-borne mycoflora from sorghum and foxtail millet seeds on germination and disease transmission. Mycobiology 2011, 39, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrović, K.; Skaltsas, D.; Castlebury, L.A.; Kontz, B.; Allen, T.W.; Chilvers, M.I.; Gregory, N.; Kelly, H.M.; Koehler, A.M.; Kleczewski, N.M. Diaporthe seed decay of soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] is endemic in the United States, but new fungi are involved. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengistu, A.; Castlebury, L.A.; Morel, W.; Ray, J.D.; Smith, J.R. Pathogenicity of Diaporthe spp. isolates recovered from soybean (Glycine max) seeds in Paraguay. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 36, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Kim, M.Y.; Chaisan, T.; Lee, Y.W.; Van, K.; Lee, S.H. Phomopsis (Diaporthe) species as the cause of soybean seed decay in Korea. J. Phytopathol. 2013, 161, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, M.B.D.S.; Resende, M.L.V.; Pozza, E.A.; da Cruz Machado, J.; de Resende, A.R.M.; Cardoso, A.M.S.; da Silva Costa Guimarães, S.; dos Santos Botelho, D.M. Effect of temperature on Colletotrichum truncatum growth, and evaluation of its inoculum potential in soybean seed germination. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2021, 160, 999–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrozo, R.; Little, C.R. Fusarium verticillioides inoculum potential influences soybean seed quality. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2017, 148, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivic, D. Pathogenicity and potential toxigenicity of seed-borne Fusarium species on soybean and pea. J. Plant Pathol. 2014, 96, 541–551. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R.E.; Ebelhar, M.W.; Wilkerson, T.; Bellaloui, N.; Golden, B.R.; Irby, J.; Martin, S. Effects of purple seed stain on seed quality and composition in soybean. Plants 2020, 9, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, T. Effect of black point on seed germination parameters in popular wheat cultivars of Northern India. Indian Phytopathol. 2021, 74, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, F.; Zare, L.; Khaledi, N. Evaluation of germination and vigor indices associated with Fusarium-infected seeds in pre-basic seeds wheat fields. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2019, 59, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- El-Gremi, S.M.; Draz, I.S.; Youssef, W.A.-E. Biological control of pathogens associated with kernel black point disease of wheat. Crop Prot. 2017, 91, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, I.; Jenkinson, P.; Hare, M. The effect of a mixture of seed-borne Microdochium nivale var. majus and Microdochium nivale var. nivale infection on Fusarium seedling blight severity and subsequent stem colonisation and growth of winter wheat in pot experiments. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2009, 124, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudec, K.; Muchová, D. Influence of temperature and species origin on Fusarium spp. and Microdochium nivale pathogenicity to wheat seedlings. Plant Prot. Sci. 2010, 46, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharafi, Z.; Sadravi, M.; Abdollahi, M. Impact of 29 seed-borne fungi on seed germination of four commercial wheat cultivars. Seed Sci. Technol. 2017, 45, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perello, A.E.; Larran, S. Nature and effect of Alternaria spp. complex from wheat grain on germination and disease transmission. Pak. J. Bot. 2013, 45, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, C.X.; Wang, X.M.; Zhu, Z.D.; Wu, X.F. Testing of seedborne fungi in wheat germplasm conserved in the National Crop Genebank of China. Agric. Sci. China 2007, 6, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, J.; Kobayashi, T.; Natsuaki, K. Seed-borne fungi on genebank-stored cruciferous seeds from Japan. Seed Sci. Technol. 2014, 42, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.; Gupta, S.K.; Swapnil, P.; Zehra, A.; Dubey, M.K.; Upadhyay, R.S. Alternaria toxins: Potential virulence factors and genes related to pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burmeister, H.; Hesseltine, C. Biological assays for two mycotoxins produced by Fusarium tricinctum. Appl. Microbiol. 1970, 20, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, H.A.H. Phytotoxicity of pathogenic fungi and their mycotoxins to cereal seedling viability. Mycopathologia 1999, 148, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylkowska, K.; Grabarkiewicz-Szczesna, J.; Iwanowska, H. Production of toxins by Alternaria alternata and A. radicina and their effects on germination of carrot seeds. Seed Sci. Technol. 2003, 31, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Hao, J.; Mayfield, D.; Luo, L.; Munkvold, G.P.; Li, J. Roles of genotype-determined mycotoxins in maize seedling blight caused by Fusarium graminearum. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cuervo, M.; Moreno, M.; Flor Payán, N.; Ramírez, J.; Medina, C.; Debouck, D.G.; Martínez, J. Handbook of Procedures of the Germplasm Health Laboratory. Genetic Resources Program; International Center for Tropical Agriculture: Cali, Colombia, 2009; 67p, Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/49630/HANDBOOK%20OF%20PROCEDURES-GHL.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Upadhyaya, H.D.; Gowda, C.L.L. Managing and Enhancing the Use of Germplasm. Strategies and Methodologies; Volume Technical Manual Nº 10; International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics: Patancheru, India, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzalama, M. Seed Health: Rules and Regulations for the Safe Movement of Germplasm, 2nd ed.; CIMMYT: Mexico City, Mexico, 2010; 20p, Available online: https://repository.cimmyt.org/bitstream/handle/10883/1312/93586.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Kulkarni, G.G. Seed Health Testing Guidelines and Operational Manual; International Rice Research Institute (IRRI): LosBaños, Phillipines, 2019; p. 381. Available online: http://books.irri.org/SHU_Operational_Manual.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Jacob, S.R.; Singh, N.; Srinivasan, K.; Gupta, V.; Radhamani, J.; Kak, A.; Pandey, C.; Pandey, S.; Aravind, J.; Bisht, I.S.; et al. Management of Plant Genetic Resources; National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources: New Delhi, India, 2015; p. 323. Available online: http://www.nbpgr.ernet.in/Downloads/cid/Downloadfile.aspx?EntryId=5899 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Klein, R.; Wyatt, S.; Kaiser, W. Effect of diseased plant elimination on genetic diversity and Bean Common Mosaic Virus incidence in Phaseolus vulgaris germplasm collections. Plant Dis. 1990, 74, 911–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, V.; Romanazzi, G. Seed treatments to control seedborne fungal pathogens of vegetable crops. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; You, M.P.; Laudinot, V.; Barbetti, M.J.; Aubertot, J.-N. Revisiting sustainability of fungicide seed treatments for field crops. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- FAO/IPGRI. Genebank Standards; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, L.; Agindotan, B.O.; Burrows, M.E. Antifungal activity of plant-derived essential oils on pathogens of pulse crops. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 1692–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, E.; Roberts, S.J. Non-chemical Seed Treatment in the Control of Seed-Borne Pathogens. In Global Perspectives on the Health of Seeds and Plant Propagation Material. Plant Pathology in the 21st Century; Gullino, M.L., Munkvold, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 6, pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Shim, C.; Lee, J.; Wangchuk, C. Hot Water Treatment as Seed Disinfection Techniques for Organic and Eco-Friendly Environmental Agricultural Crop Cultivation. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrissin, I.; Sano, N.; Seo, M.; North, H.M. Ageing beautifully: Can the benefits of seed priming be separated from a reduced lifespan trade-off? J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2312–2333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Relative Humidity (%) | Fungi | Seed Equilibrium Moisture Content 1 (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starchy Cereals | Soybeans | Sunflower, Safflower, Peanut | ||

| 65–70 | Aspergillus halophilicus | 13.0–14.0 | 12.0–13.0 | 5.0–6.0 |

| 70–75 | A. restrictus, A. glaucus, Wallemia sebi | 14.0–15.0 | 13.0–14.0 | 6.0–7.0 |

| 75–80 | A. candidus, A. ochraceus, plus the above | 14.5–16.0 | 14.0–15.0 | 7.0–8.0 |

| 80–85 | A. flavus, Penicillium, plus the above | 16.0–18.0 | 15.0–17.0 | 8.0–10.0 |

| 85–90 | Penicillium, plus the above | 18.0–20.0 | 17.0–19.0 | 10.0–12.0 |

| Type of Assay | Time Required | Sensitivity | Ease of Application | Specificity | Ease of Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual examination | <10 min | Low | Simple and inexpensive | Low | Mycological skills required |

| Staining method | <10 min | Low–moderate | Simple and inexpensive | Low–moderate | Mycological skills required |

| Embryo extraction | <10 min | Low–moderate | Inexpensive | Low–moderate | Mycological skills required |

| Seed washing test | <30 min | Low | Simple and inexpensive | Low | Mycological skills required |

| Agar plating | 5–7 days | Moderate | Simple and inexpensive | Low–moderate | Mycological skills required |

| Blotter test | 1 week | Moderate | Simple and inexpensive | Moderate | Mycological skills required |

| Seedling symptom test | 2–3 weeks | Low | Simple and inexpensive | Low | Mycological skills required |

| Pathogenicity test | 2–3 weeks | Moderate | Inexpensive | Low | Mycological skills required |

| Serology-based assay (ELISA) | 2–4 h | Moderate-high | Simple, moderately expensive and robust | Moderate-high | Ease of interpretation |

| PCR conventional | 5–6 h | High | Complicated ease of interpretation and expensive | Very high | Molecular biology skills required and ease of interpretation |

| Nested PCR | 5–6 h | Very high | Complicated and expensive | High | Molecular biology skills required and ease of interpretation |

| Multiplex PCR | 5–6 h | High | Complicated ease of interpretation and expensive | Very high | Molecular biology skills required and ease of interpretation |

| Real time PCR | 40–60 min | Very high | Complicated and expensive | Very high | Molecular biology skills required |

| MCR-PCR | 2–5 h | Very high | Complicated and expensive | Very high | Molecular biology skills required |

| Bio-PCR | 5–7 days | Very high | Complicated and expensive | Very high | Molecular biology skills required and ease of interpretation |

| LAMP assay | <4 h | High | Expensive | Very high | Molecular biology skills required and ease of interpretation. Portable devices. |

| HTS | 4–7 days | High | Complicated and very expensive | High | Molecular biology and bioinformatic skills required |

| DNA barcoding | 4–7 days | High | Complicated and expensive | Very high | Molecular biology and bioinformatic skills required |

| MALDI-TOF MS | 5–6 h | High-moderate | Simple, moderately expensive | High | Ease of interpretation |

| MSI | <2 h | Moderate | Simple | Low | Technological skills required |

| Host | Fungus | Country | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brassica rapa | Alternaria brassicae, A. raphani | Canada | Rude et al. [129] |

| Barley | Fusarium graminearum | Canada | Tekauz et al. [130] |

| Fusarium spp. and others | Slovakia | Hudec [131] | |

| Carrot | Alternaria spp. | Serbia | Bulajić et al. [132] |

| Alternaria alternata | China | Zhang et al. [133] | |

| Cauliflower | Alternaria brassicicola, A. brassicae | The Netherlands | Köhl et al. [134] |

| Chickpea | Ascochyta rabiei | Pakistan | Ahmad et al. [135] |

| Groundnut | Aspergillus flavus, A. niger and others | India | Kar et al. [136] |

| Legumes | Macrophomina phaseolina | Review | Pandey et al. [137] |

| Lolium multiflorum | Neotyphodium occultans | Argentina | Gundel et al. [138] |

| Lolium perenne | Fusarium spp., Bipolaris sorokiniana and others | China | Zhang et al. [139] |

| Maize | Fusarium verticilloides | USA | Yates et al. [140] |

| Fusarium verticilloides | Nigeria | Anjorin et al. [141] | |

| Aspergillus flavus | USA | Dolezal et al. [142] | |

| Stenocarpella maydis | Brazil | Siquiera et al. [143] | |

| Oat | Fusarium graminearum | Norway | Tekle et al. [144] |

| Rapeseed (Brassica napus) | Alternaria spp. | Pakistan | Soomro et al. [145] |

| Rice | Sarocladium oryzae | India | Gopalakrishnan et al. [146] |

| Bipolaris oryzae | Brazil | Schwanck et al. [147] | |

| Sorghum and foxtail millet (Setaria italica) | Alternaria, Curvularia, Fusarium and others | South Korea | Yago et al. [148] |

| Soybean | Diaporthe species complex | USA | Petrović et al. [149] |

| Diaporthe species complex | Paraguay | Mengistu et al. [150] | |

| Diaporthe species complex | Korea | Sun et al. [151] | |

| Colletotrichum truncatum | Brasil | Da Silva et al. [152] | |

| Fusarium verticilloides | USA | Pedrozo and Little [153] | |

| Fusarium spp. | Italy | Ivic [154] | |

| Cercospora kukuchii | USA | Turner et al. [155] | |

| Wheat | Black point (Alternaria triticina, Bipolaris sorokiniana, Fusarium graminearum) | India | Sharma et al. [156] |

| Fusarium graminearum | Iran | Hassani et al. [157] | |

| Black point (Alternaria alternata, Bipolaris sorokiniana, Fusarium graminearum) | Egypt | El-Gremi et al. [158] | |

| Fusarium culmorum, Microdochium nivale | UK | Haigh et al. [159] | |

| Fusarium spp., Microdochium nivale | Slovakia | Hudec and Muchová [160] | |

| Bipolaris, Fusarium, Thielavia, and others | Iran | Sharafi et al. [161] | |

| Alternaria spp. Complex | Argentina | Perelló and Larran [162] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martín, I.; Gálvez, L.; Guasch, L.; Palmero, D. Fungal Pathogens and Seed Storage in the Dry State. Plants 2022, 11, 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11223167

Martín I, Gálvez L, Guasch L, Palmero D. Fungal Pathogens and Seed Storage in the Dry State. Plants. 2022; 11(22):3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11223167

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartín, Isaura, Laura Gálvez, Luis Guasch, and Daniel Palmero. 2022. "Fungal Pathogens and Seed Storage in the Dry State" Plants 11, no. 22: 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11223167

APA StyleMartín, I., Gálvez, L., Guasch, L., & Palmero, D. (2022). Fungal Pathogens and Seed Storage in the Dry State. Plants, 11(22), 3167. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11223167