Optimal Contribution Selection Improves the Rate of Genetic Gain in Grain Yield and Yield Stability in Spring Canola in Australia and Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Terminology

2.2. Founder Population, Crossing and Selfing to Begin Cycle 1

2.3. Cycles of Augmented S0,1 Family Selection

2.4. Pedigree Structure and Relationships

2.5. Field Trials and Phenotyping

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Preliminary Single Site Analysis

2.6.2. Base Univariate Model Across-Sites

2.6.3. Factor Analytic Modelling of Each Trait across Sites

2.6.4. Genotype Overall Performance and Stability

2.7. Economic Index

2.8. Optimal Contributions Selection and Crossing

2.9. Assessment of Genetic Gain

3. Results

3.1. Environmental Trends over Cycles and Countries

3.2. Genetic Relationships of Genotypes within and across Cycles

3.2.1. Connectivity of Genotypes within and across Cycles

3.2.2. Inbreeding Coefficients and Coefficients of Coancestry

3.3. Analysis of Sites and Cycles

3.3.1. Base Across-Sites Model

3.3.2. Optimum MMM-FA Models

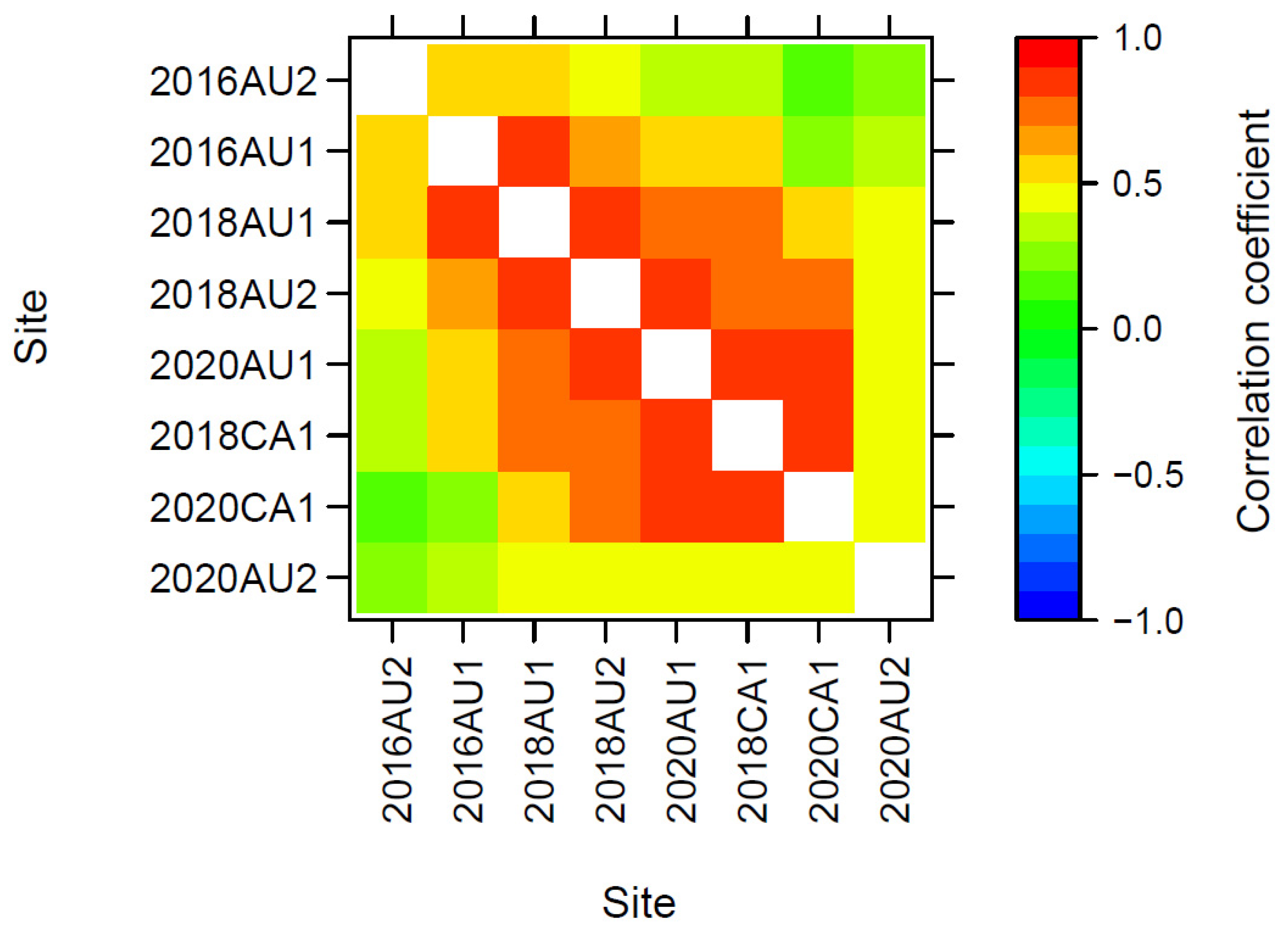

3.3.3. Genetic Correlations across Trials

3.4. Pairwise Correlations of PBV across Traits

3.5. PBV, Overall Performance and Yield Stability for GY

3.6. Genetic Gain across Cycles

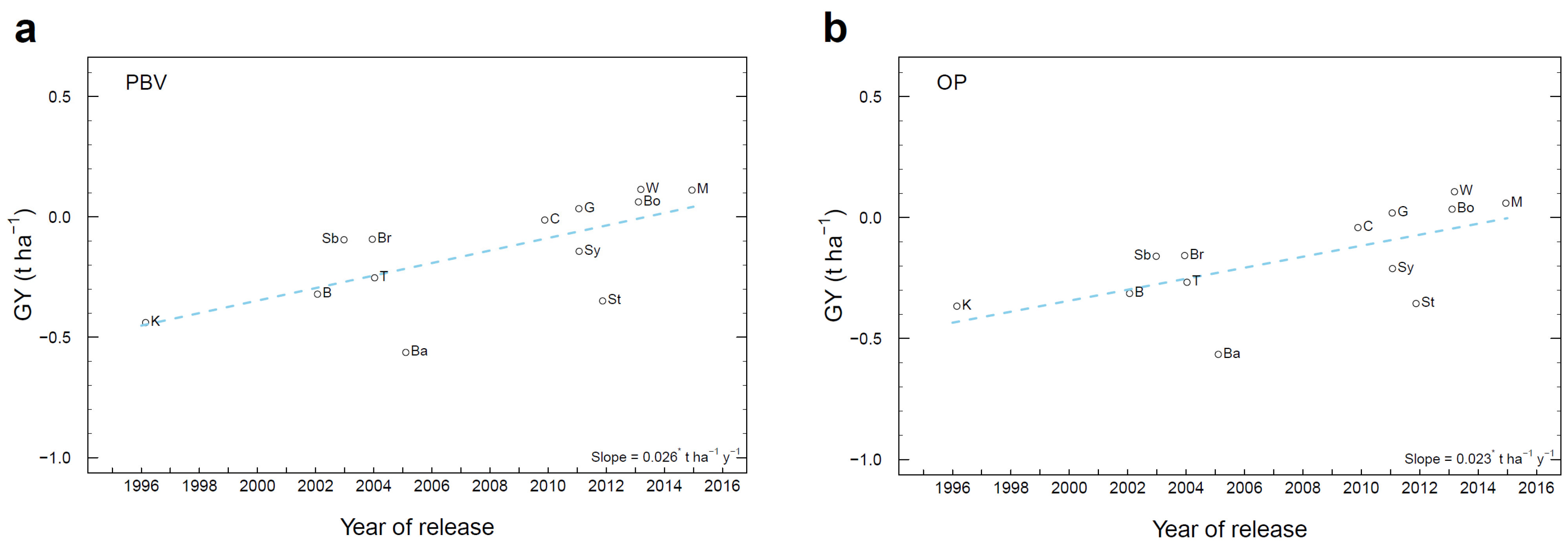

3.7. Genetic Gain in Historical Cultivars

3.8. Impact of Genetic Correlations between Traits on Genetic Gain

3.9. Predictions from OCS in Cycle 5 with and without RMSD GY in the Economic Index

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lenaerts, B.; Collard, B.C.; Demont, M. Review: Improving global food security through accelerated plant breeding. Plant Sci. 2019, 287, 110207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, D.K.; Ramankutty, N.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.; Foley, J.A. Recent patterns of crop yield growth and stagnation. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, D.K.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A. Yield trends are insufficient to double global crop production by 2050. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochman, Z.; Gobbett, D.L.; Horan, H. Climate trends account for stalled wheat yields in Australia since 1990. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, J.N.; Juma, R.U.; Biswas, P.S.; Arbelaez, J.D.; Rutkoski, J.; Atlin, G.; Hagen, T.; Quinn, M.; Ng, E.H. Enhancing the rate of genetic gain in public-sector plant breeding programs: Lessons from the breeder’s equation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2019, 132, 627–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlin, G.N.; Cairns, J.E.; Das, B. Rapid breeding and varietal replacement are critical to adaptation of cropping systems in the developing world to climate change. Glob. Food Secur. 2017, 12, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, D.; Li, Y.; Crossa, J.; Dreisigacker, S.; Basnet, B.; Pérez-Rodríguez, P.; Alvarado, G.; Jannink, J.L.; Poland, J.; Sorrells, M. Response to Early Generation Genomic Selection for Yield in Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 12, 718611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, K.J.; Holland, J.B. Nine cycles of recurrent selection for increased groat-oil content in oat. Crop Sci. 1999, 39, 1636–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, W.; Li, L.; Siddique, K.; Henryon, M.; Berg, P.; Banks, R.; Kinghorn, B. Evolving gene banks: Improving diverse populations of crop and exotic germplasm with optimal contribution selection. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1927–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, W.A.; Li, L.; Siddique, K.; Banks, R.G.; Kinghorn, B.P. Modeling crop breeding for global food security during climate change. Food Energy Secur. 2019, 8, e00157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkoski, J.E. A practical guide to genetic gain. Adv. Agron. 2019, 157, 217–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkoski, J.E. Estimation of Realized Rates of Genetic Gain and Indicators for Breeding Program Assessment. Crop. Sci. 2019, 59, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.; Chen, P.; Shi, A.; Zhang, B.; Scaboo, A.; Smith, S.F.; Zeng, A. Agronomic performance and genetic progress of selected historical soybean varieties in the southern USA. Plant Breed. 2015, 134, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Terán, H.; Lema, M.; Webster, D.M.; Strausbaugh, C.A.; Miklas, P.N.; Schwartz, H.F.; Brick, M.A. Seventy-five Years of Breeding Dry Bean of the Western USA. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 981–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, I.; Horwell, A.; Garner, J.; White, J.; McKee, J.; Philpott, H. Reanalyses of the historical series of UK variety trials to quantify the contributions of genetic and environmental factors to trends and variability in yield over time. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2011, 122, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piepho, H.-P.; Laidig, F.; Drobek, T.; Meyer, U. Dissecting genetic and non-genetic sources of long-term yield trend in German official variety trials. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Postma, E. Implications of the difference between true and predicted breeding values for the study of natural selection and micro-evolution. J. Evol. Biol. 2006, 19, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrick, D.J. An animal breeding approach to the estimation of genetic and environmental trends from field populations. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88 (Suppl. E), E3–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, E.; Charmantier, A. What ‘animal models’ can and cannot tell ornithologists about the genetics of wild populations. J. Ornithol. 2007, 148 (Suppl. 2), 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, B.; Lynch, M. Evolution and Selection of Quantitative Traits; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanova, K.T.; Buirchell, B. Multiplicative Mixed Models for Genetic Gain Assessment in Lupin Breeding. Crop Sci. 2010, 50, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.B.; Cullis, B.R. Plant breeding selection tools built on factor analytic mixed models for multi-environment trial data. Euphytica 2018, 214, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowling, W.A.; Stefanova, K.T.; Beeck, C.P.; Nelson, M.N.; Hargreaves, B.L.W.; Sass, O.; Gilmour, A.R.; Siddique, K. Using the Animal Model to Accelerate Response to Selection in a Self-Pollinating Crop. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2015, 5, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldenbroek, K.; van der Waaij, L. Textbook Animal Breeding and Genetics for BSc students. Centre for Genetic Resources, The Netherlands and Animal Breeding and Genomics Centre. 2015. Available online: https://wiki.groenkennisnet.nl/display/TAB/ (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Gorjanc, G.; Gaynor, R.C.; Hickey, J.M. Optimal cross selection for long-term genetic gain in two-part programs with rapid recurrent genomic selection. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2018, 131, 1953–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinghorn, B.P.; Kinghorn, A.J. Instructions for MateSel. 2022. Available online: https://matesel.une.edu.au/content/documentation/MateSelInstructions.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Kinghorn, B.P.; Banks, R.; Gondro, C.; Kremer, V.D.; Meszaros, S.A.; Newman, S.; Shepherd, R.K.; Vagg, R.D.; Van Der Werf, J.H.J. Strategies to Exploit Genetic Variation While Maintaining Diversity. In Adaptation and Fitness in Animal Populations; van der Werf, J., Graser, H.-U., Frankham, R., Gondro, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinghorn, B.P. An algorithm for efficient constrained mate selection. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2011, 43, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salisbury, P.A.; Cowling, W.A.; Potter, T.D. Continuing innovation in Australian canola breeding. Crop Pasture Sci. 2016, 67, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.S.; Kharbanda, P.D.; Barbetti, M.J.; Fitt, B.D.L. Epidemiology and management of Leptosphaeria maculans (phoma stem canker) on oilseed rape in Australia, Canada and Europe. Plant Pathol. 2001, 50, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, B.; Edriss, V.; Akdemir, D.; Autrique, E.; Bonnett, D.; Crossa, J.; Janss, L.; Singh, R.; Jannink, J.-L. Genomic Prediction using Phenotypes from Pedigreed Lines with No Marker Data. Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saradadevi, R.; Mukankusi, C.; Li, L.; Amongi, W.; Mbiu, J.P.; Raatz, B.; Ariza, D.; Beebe, S.; Varshney, R.K.; Huttner, E.; et al. Multivariate genomic analysis and optimal contributions selection predicts high genetic gains in cooking time, iron, zinc and grain yield in common beans in East Africa. Plant Genome 2021, 14, e20156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beversdorf, W.D.; Weiss-Lerman, J.; Erickson, L.R.; Souza Machado, V. Transfer of cytoplasmically-inherited triazine resistance from bird’s rape to cultivated oilseed rape (Brassica campestris and B. napus). Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 1980, 22, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, D.G.; Cullis, B.R.; Gilmour, A.R.; Gogel, B.J.; Thompson, R. ASReml-R Reference Manual Version 4; VSN International Ltd.: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IP Australia. Plant Breeder’s Rights Database. 2022. Available online: http://pericles.ipaustralia.gov.au/pbr_db/ (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Cullis, B.R.; Smith, A.B.; Coombes, N.E. On the design of early generation variety trials with correlated data. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2006, 11, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petisco, C.; García-Criado, B.; Vázquez-de-Aldana, B.R.; de Haro, A.; García-Ciudad, A. Measurement of quality parameters in intact seeds of Brassica species using visible and near-infrared spectroscopy. Ind. Crops Prod. 2010, 32, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeck, C.P.; Cowling, W.; Smith, A.B.; Cullis, B.R. Analysis of yield and oil from a series of canola breeding trials. Part I. Fitting factor analytic mixed models with pedigree. Genome 2010, 53, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullis, B.; Smith, A.; Beeck, C.; Cowling, W. Analysis of yield and oil from a series of canola breeding trials. Part II. Exploring variety by environment interaction using factor. Genome 2010, 53, 1002–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, A.M.; Smith, A.B.; Eccleston, J.A.; Cullis, B.R. The Accuracy of Varietal Selection Using Factor Analytic Models for Multi-Environment Plant Breeding Trials. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakey, H.; Verbyla, A.P.; Cullis, B.R.; Wei, X.; Pitchford, W.S. Joint modeling of additive and non-additive (genetic line) effects in multi-environment trials. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2007, 114, 1319–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.; Cullis, B.; Thompson, R. Analyzing Variety by Environment Data Using Multiplicative Mixed Models and Adjustments for Spatial Field Trend. Biometrics 2001, 57, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, H.D.; Thompson, R. Recovery of inter-block information when block sizes are unequal. Biometrika 1971, 58, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, C.R. Applications of Linear Models in Animal Breeding; University of Guelph: Guelph, ON, Canada, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour, A.R.; Gogel, B.J.; Cullis, B.R.; Welham, S.J.; Thompson, R. ASReml User Guide Release 4.1 Structural Specification; VSN International Ltd.: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmour, A.R.; Cullis, B.R.; Verbyla, A.P. Accounting for Natural and Extraneous Variation in the Analysis of Field Experiments. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 1997, 2, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanova, K.T.; Smith, A.B.; Cullis, B.R. Enhanced diagnostics for the spatial analysis of field trials. J. Agric. Biol. Environ. Stat. 2009, 14, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike; Parzen, E., Tanabe, K., Kitagawa, G., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 199–213. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 1978, 6, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Oilseeds Federation. AOF Standards Manual 2021/22–Section 1: Quality Standards, Technical In-formation & Typical Analysis. Issue 20. 2021. Available online: http://www.australianoilseeds.com/Technical_Info/standards_manual (accessed on 8 June 2022).

- Cowling, W.A. Genetic diversity in Australian canola and implications for crop breeding for changing future environments. Field Crops Res. 2007, 104, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACIAR Research. Rapid Cooking Bean Project. BRÍO. 2022. Available online: https://research.aciar.gov.au/rapidcookingbeans/brio (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Meuwissen, T.H.E.; Sonesson, A.K.; Gebregiwergis, G.; Woolliams, J.A. Management of Genetic Diversity in the Era of Genomics. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolliams, J.A.; Berg, P.; Dagnachew, B.S.; Meuwissen, T.H.E. Genetic contributions and their optimization. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2015, 132, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, R.K.; Roorkiwal, M.; Sun, S.; Bajaj, P.; Chitikineni, A.; Thudi, M.; Singh, N.P.; Du, X.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Khan, A.W.; et al. A chickpea genetic variation map based on the sequencing of 3366 genomes. Nature 2021, 599, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaynor, R.C.; Gorjanc, G.; Bentley, A.R.; Ober, E.S.; Howell, P.; Jackson, R.; Mackay, I.J.; Hickey, J.M. A Two-Part Strategy for Using Genomic Selection to Develop Inbred Lines. Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 2372–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, L.N.; Lush, J.L. The efficiency of three methods of selection. J. Hered. 1942, 33, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.; Rempel, C.B.; Wanasundara, J.P. Canola/Rapeseed Protein: Future Opportunities and Directions—Workshop Proceedings of IRC 2015. Plants 2016, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Genotypes in Trial | ||||||||||||||

| Cycle | Trial Code | Trial Location | Country | Ranges | Rows | Plots | Total | Single Replicate | S0 | S1 | S2 | S4 | F2 | F3 |

| 1 | 2014AU1 | West Dale, WA | Australia | 24 | 89 | 2136 | 1557 | 1080 | 668 | 250 | 0 | 0 | 577 | 52 |

| 2 | 2016AU1 | York, WA | Australia | 24 | 68 | 1632 | 1175 | 898 | 511 | 0 | 569 | 0 | 11 | 55 |

| 2 | 2016AU2 | Rutherglen, VIC | Australia | 24 | 68 | 1632 | 1174 | 899 | 511 | 0 | 568 | 0 | 11 | 55 |

| 3 | 2018AU1 | York, WA | Australia | 24 | 88 | 2112 | 1919 | 1769 | 1565 | 0 | 151 | 166 | 13 | 0 |

| 3 | 2018AU2 | Rutherglen, VIC | Australia | 24 | 88 | 2112 | 1912 | 1771 | 1566 | 0 | 151 | 166 | 13 | 0 |

| 3 | 2018CA1 | Sun Valley, MB | Canada | 24 | 88 | 2112 | 1919 | 1772 | 1566 | 0 | 151 | 166 | 13 | 0 |

| 4 | 2020AU1 | Williams, WA | Australia | 24 | 40 | 960 | 674 | 436 | 653 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 2020AU2 | Wonwondah, VIC | Australia | 24 | 38 | 912 | 625 | 386 | 604 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 2020CA1 | Sun Valley, MB | Canada | 24 | 34 | 816 | 555 | 308 | 528 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||||

| Connectivity of Genotypes across Trials | ||||||||||||||

| Cycle | Trial Code | 2014AU1 | 2016AU1 | 2016AU2 | 2018AU1 | 2018AU2 | 2018CA1 | 2020AU1 | 2020AU2 | 2020CA1 | ||||

| 1 | 2014AU1 | 1556 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 2 | 2016AU1 | 3 | 1175 | 886 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| 2 | 2016AU2 | 3 | 886 | 1174 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 5 | ||||

| 3 | 2018AU1 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 1911 | 1911 | 1911 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 3 | 2018AU2 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 1911 | 1912 | 1912 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||||

| 3 | 2018CA1 | 2 | 13 | 13 | 1911 | 1912 | 1919 | 4 | 4 | 9 | ||||

| 4 | 2020AU1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 674 | 625 | 548 | ||||

| 4 | 2020AU2 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 625 | 625 | 548 | ||||

| 4 | 2020CA1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 548 | 548 | 555 | ||||

| Trait a | Population Mean (Units of Trait) | Range of PBV in Population (Units of Trait) | PBV of the Individual (Units of Trait) | Total GY of Individual (t ha−1) | Grain Price (US$ t−1) | Economic Weight for +1 PBV Unit | Contribution to Economic Index of the Individual (US$ ha−1) | Calculation of Economic Index (US$ ha−1) (Based on Economic Weight for +1 PBV in US$ t−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | % Grain Price | US$ t−1 | |||||||

| GY | 2.020 | −0.910 | +0.644 | +0.322 | 2.342 | 550.00 | $1288.10 | (Total GY of Individual) × (Grain Price) | ||

| Oil | 44.757 | −6.673 | +3.686 | +1.383 | 1.50% | $8.25 | $26.72 | (PBV Oil) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| ProM | 41.088 | −4.062 | +5.508 | +0.554 | 3.00% | $16.50 | $21.41 | (PBV ProM) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| DTF | 80.180 | −13.507 | +15.639 | +2.213 | −1.00% | −$5.50 | −$28.51 | (PBV DTF) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| PlHt | 122.675 | −29.380 | +26.952 | +3.561 | −0.50% | −$2.75 | −$22.93 | (PBV PlHt) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| BL | 5.089 | −1.996 | +2.671 | +1.297 | 2.00% | $11.00 | $33.41 | (PBV BL) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| GSL | 11.297 | −5.637 | +16.325 | −1.749 | −1.50% | −$8.25 | $33.79 | (PBV GSL) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| SW100 | 0.325 | −0.030 | +0.039 | +0.024 | 0.20% | $1.10 | $0.06 | (PBV SW100) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| OL | 61.670 | −8.132 | +8.939 | +2.328 | 0.00% | $0.00 | $0.00 | (PBV OL) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| RMSD GY | 0.096 | 0.000 | +0.411 | +0.215 | −20.0% | −$110.00 | −$55.39 | (PBV RMSD GY) × (Total GY) × (Econ Wt +1 unit PBV) | ||

| Economic index excluding RSMD GY | $1352.06 | sum of above excluding RMSD GY (t ha−1) | ||||||||

| Economic index including RMSD GY | $1296.67 | sum of above including RMSD GY (t ha−1) | ||||||||

| MMM-FA Model | Number of Estimated Variance Components | RLL | AIC | BIC | %VAF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grain yield (t ha−1) | |||||

| Base | 44 | 8455.622 | −16,823.2 | −16,497.2 | |

| FA(1) | 53 | 8635.382 | −17,164.8 | −16,772.1 | 63.31 |

| FA(2) a | 59 | 8647.610 | −17,177.2 | −16,740.1 | 68.33 |

| FA(3) | 65 | 8656.074 | −17,182.2 | −16,700.5 | 70.97 |

| Days to 50% flower | |||||

| Base | 25 | −11,863.700 | 23,777.41 | 23,950.84 | |

| FA(1) a | 31 | −11,642.660 | 23,347.32 | 23,562.38 | 96.22 |

| FA(2) | 34 | −11,638.730 | 23,345.45 | 23,581.33 | 96.40 |

| Plant height (cm) | |||||

| Base | 24 | −15,452.09 | 30,952.18 | 31,110.93 | |

| FA(1) | 29 | −15,392.17 | 30,842.34 | 31,034.16 | 31.83 |

| FA(2) a | 31 | −15,382.06 | 30,826.13 | 31,031.18 | 93.52 |

| Seed oil (%) at 6% moisture | |||||

| Base | 34 | −8169.558 | 16,407.12 | 16,649.38 | |

| FA(1) | 41 | −7836.272 | 15,754.54 | 16,046.69 | 81.46 |

| FA(2) a | 45 | −7825.844 | 15,741.69 | 16,062.33 | 94.57 |

| Protein in meal (%) at 10% moisture | |||||

| Base | 33 | −7462.394 | 14,990.79 | 15,225.92 | |

| FA(1) | 40 | −7189.898 | 14,459.80 | 14,744.80 | 32.24 |

| FA(2) a | 44 | −7188.877 | 14,465.75 | 14,779.26 | 84.99 |

| Glucosinolates (μmole g−1 seed) | |||||

| Base | 33 | −12,630.21 | 25,326.41 | 25,561.54 | |

| FA(1) | 40 | −12,121.96 | 24,323.92 | 24,608.93 | 75.34 |

| FA(2) a | 44 | −12,118.56 | 24,325.12 | 24,638.63 | 94.77 |

| Oleic acid (% of total fatty acids) | |||||

| Base | 22 | −5873.146 | 11,790.29 | 11,938.68 | |

| FA(1) | 27 | −5556.775 | 11,167.55 | 11,349.66 | 90.85 |

| FA(2) a | 29 | −5554.522 | 11,167.04 | 11,362.64 | 97.22 |

| Phoma stem canker (blackleg) disease score: 1 (very susceptible) to 9 (very resistant) | |||||

| Base | 16 | −3164.365 | 6360.730 | 6463.844 | |

| FA(1) | 20 | −3149.209 | 6338.417 | 6467.310 | 74.05 |

| FA(2) a | 21 | −3149.208 | 6340.417 | 6475.754 | 83.74 |

| 100 seed weight (g) | |||||

| Base | 22 | 19,743.45 | −39,442.91 | −39,294.51 | |

| FA(1) a | 27 | 19,808.11 | −39,562.21 | −39,380.09 | 51.93 |

| Trait a | Population Mean | Units | Method of Breeding Value Assessment | Mean PBV of Candidate Genotypes in each Cycle (Number of Candidates in each Cycle) | Linear Regression of PBV of Candidate Genotypes from Cycles 2 to 4 | Annual Genetic Gain from Cycles 2 to 4b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 2 (1426) | Cycle 3 (1896) | Cycle 4 (653) | Coefficient | Intercept | ||||||

| Units Cycle−1 ± SE | Units ± SE | Change in Coefficient (units y−1) | Change in Coefficient (% y−1) | |||||||

| Index | 963.8 | US$ ha−1 | PBV | 857.309 | 994.828 | 1106.341 | 139.910 ± 2.424 | 593.210 ± 7.008 | 69.955 | 7.26 |

| 944.6 | OP | 868.862 | 961.426 | 1061.069 | 95.430 ± 2.316 | 676.870 ± 6.696 | 47.714 | 5.05 | ||

| GY | 2.02 | t ha−1 | PBV | −0.207 | 0.026 | 0.113 | 0.1741 ± 0.0095 | −0.5321 ± 0.0033 | 0.0870 | 4.31 |

| OP | −0.188 | −0.04 | 0.032 | 0.1172 ± 0.0030 | −0.4099 ± 0.0087 | 0.0585 | 2.90 | |||

| DTF | 80.2 | days | PBV | 1.872 | 2.135 | 0.474 | −0.5150 ± 0.0932 | 3.2127 ± 0.2695 | −0.258 | −0.32 |

| OP | 1.793 | 1.945 | 0.343 | −0.5580 ± 0.0888 | 3.1916 ± 0.2568 | −0.279 | −0.35 | |||

| PlHt | 122.7 | cm | PBV | 0.254 | 2.923 | −1.275 | −0.1711 ± 0.1776 | 1.7305 ± 0.5133 | −0.0860 | −0.07 |

| OP | 0.212 | 2.927 | −1.419 | −0.1406 ± 0.1857 | 1.6337 ± 0.5369 | −0.0705 | −0.06 | |||

| Oil | 44.8 | % | PBV | −0.996 | −0.366 | 0.070 | 0.5517 ± 0.0267 | −2.0681 ± 0.0772 | 0.2760 | 0.62 |

| OP | −0.978 | −0.421 | −0.012 | 0.4970 ± 0.0261 | −1.9479 ± 0.0754 | 0.2485 | 0.55 | |||

| ProM | 41.1 | % | PBV | 0.255 | 0.433 | 0.995 | 0.3331 ± 0.0268 | −0.4730 ± 0.0776 | 0.167 | 0.41 |

| OP | 0.256 | 0.508 | 1.059 | 0.3729 ± 0.0264 | −0.5380 ± 0.0762 | 0.187 | 0.45 | |||

| GSL | 11.3 | μmole g−1 | PBV | 0.314 | −0.859 | −1.030 | −0.7680 ± 0.0452 | 1.6885 ± 0.1306 | −0.384 | −3.40 |

| OP | 0.290 | −0.910 | −1.075 | −0.7820 ± 0.0444 | 1.6868 ± 0.1284 | −0.391 | −3.46 | |||

| OL | 61.7 | % | PBV | −0.194 | −0.541 | −0.645 | −0.2483 ± 0.0433 | 0.2629 ± 0.1253 | −0.124 | −0.20 |

| OP | −0.181 | −0.585 | −0.671 | −0.2755 ± 0.0431 | 0.3190 ± 0.1245 | −0.138 | −0.22 | |||

| BL | 5.1 | units | PBV | −0.283 | 0.911 | 1.234 | 0.8417 ± 0.0151 | −1.8255 ± 0.0437 | 0.421 | 8.25 |

| OP | −0.239 | 0.739 | 1.057 | 0.7114 ± 0.0136 | −1.5556 ± 0.0393 | 0.356 | 6.97 | |||

| SW100 | 0.325 | g | PBV | −0.003 | −0.005 | −0.006 | −0.0019 ± 0.0002 | 0.0010 ± 0.0005 | −0.001 | −0.30 |

| OP | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.0008 ± 0.0000 | −0.0020 ± 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.15 | |||

| (a) MateSel Output | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without RMSD GY in index | With RMSD GY in Index | Notes | |||||

| No. male candidates | 653 | 653 | |||||

| No. female candidates | 653 | 653 | |||||

| No. selected males | 44 | 41 | moderate weighting against reciprocal matings, selfings and duplicates | ||||

| No. selected females | 37 | 39 | moderate weighting against reciprocal matings, selfings and duplicates | ||||

| No. matings used | 150 | 150 | |||||

| Target degrees | 45 | 45 | conservative strategy to minimise coancestry and maximise index at 45 degrees | ||||

| Achieved degrees | 45 | 45 | |||||

| Achieved parental coancestry | 0.0850 | 0.0867 | low achieved parental coancestry | ||||

| Starting mean candidate index | 1140.80 | 1106.34 | |||||

| Achieved mean progeny index | 1307.22 | 1282.83 | aim to increase mean progeny index | ||||

| Achieved standard deviation progeny index | 24.31 | 26.78 | |||||

| Lowest selected male index | 1135.55 | 1113.01 | |||||

| Lowest selected female index | 1121.90 | 1036.26 | |||||

| Weighting on progeny mean inbreeding (F) | −1 | −1 | |||||

| Achieved progeny mean inbreeding (F) | 0.0093 | 0.0103 | low due to optimised mating scheme | ||||

| Random mating inbreeding (F) | 0.0779 | 0.0803 | predicted F based on random mating among parents | ||||

| Maximum inbreeding (F) achieved | 0.0788 | 0.0843 | achieved following optimised design | ||||

| (b) Predicted Responses in cycle 5 | |||||||

| Without RMSD GY in Index | With RMSD GY in Index | ||||||

| Units | Population Mean across Cycles 2, 3, 4 | Predicted Response in Cycle 5 (Units) | Predicted Response in Cycle 5 as % Population Mean | Predicted Response in Cycle 5 (Units) | Predicted Response in Cycle 5 as % Population Mean | Selection Aim | |

| Economic index | US$ ha−1 | 166.42 | 176.49 | increase | |||

| GY | t ha−1 | 2.017 | 0.1637 | 8.12% | 0.1696 | 8.41% | increase |

| DTF | days | 80.2 | −2.5512 | −3.18% | −2.1776 | −2.72% | decrease |

| PlHt | cm | 122.7 | −2.9254 | −2.38% | −2.6353 | −2.15% | decrease |

| Oil | % | 44.8 | 0.2626 | 0.59% | 0.2816 | 0.63% | increase |

| ProM | % | 41.1 | 0.4137 | 1.01% | 0.4426 | 1.08% | increase |

| GSL | μmole g−1 | 11.3 | −0.6780 | −6.00% | −0.7987 | −7.07% | decrease |

| OL | % | 61.7 | −0.0923 | −0.15% | −0.2025 | −0.33% | change |

| BL | scale 1−9 | 5.1 | 0.1308 | 2.57% | 0.1820 | 3.57% | increase |

| SW100 | g | 0.325 | 0.0022 | 0.69% | 0.0020 | 0.60% | increase |

| RMSD GY | t ha−1 | 0.160 | −0.0317 | −19.78% | −0.0514 | −32.15% | decrease |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cowling, W.A.; Castro-Urrea, F.A.; Stefanova, K.T.; Li, L.; Banks, R.G.; Saradadevi, R.; Sass, O.; Kinghorn, B.P.; Siddique, K.H.M. Optimal Contribution Selection Improves the Rate of Genetic Gain in Grain Yield and Yield Stability in Spring Canola in Australia and Canada. Plants 2023, 12, 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020383

Cowling WA, Castro-Urrea FA, Stefanova KT, Li L, Banks RG, Saradadevi R, Sass O, Kinghorn BP, Siddique KHM. Optimal Contribution Selection Improves the Rate of Genetic Gain in Grain Yield and Yield Stability in Spring Canola in Australia and Canada. Plants. 2023; 12(2):383. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020383

Chicago/Turabian StyleCowling, Wallace A., Felipe A. Castro-Urrea, Katia T. Stefanova, Li Li, Robert G. Banks, Renu Saradadevi, Olaf Sass, Brian P. Kinghorn, and Kadambot H. M. Siddique. 2023. "Optimal Contribution Selection Improves the Rate of Genetic Gain in Grain Yield and Yield Stability in Spring Canola in Australia and Canada" Plants 12, no. 2: 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020383

APA StyleCowling, W. A., Castro-Urrea, F. A., Stefanova, K. T., Li, L., Banks, R. G., Saradadevi, R., Sass, O., Kinghorn, B. P., & Siddique, K. H. M. (2023). Optimal Contribution Selection Improves the Rate of Genetic Gain in Grain Yield and Yield Stability in Spring Canola in Australia and Canada. Plants, 12(2), 383. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12020383