Population and Conservation Status of Buxbaumia viridis (DC.) Moug. & Nestl. in Romania

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

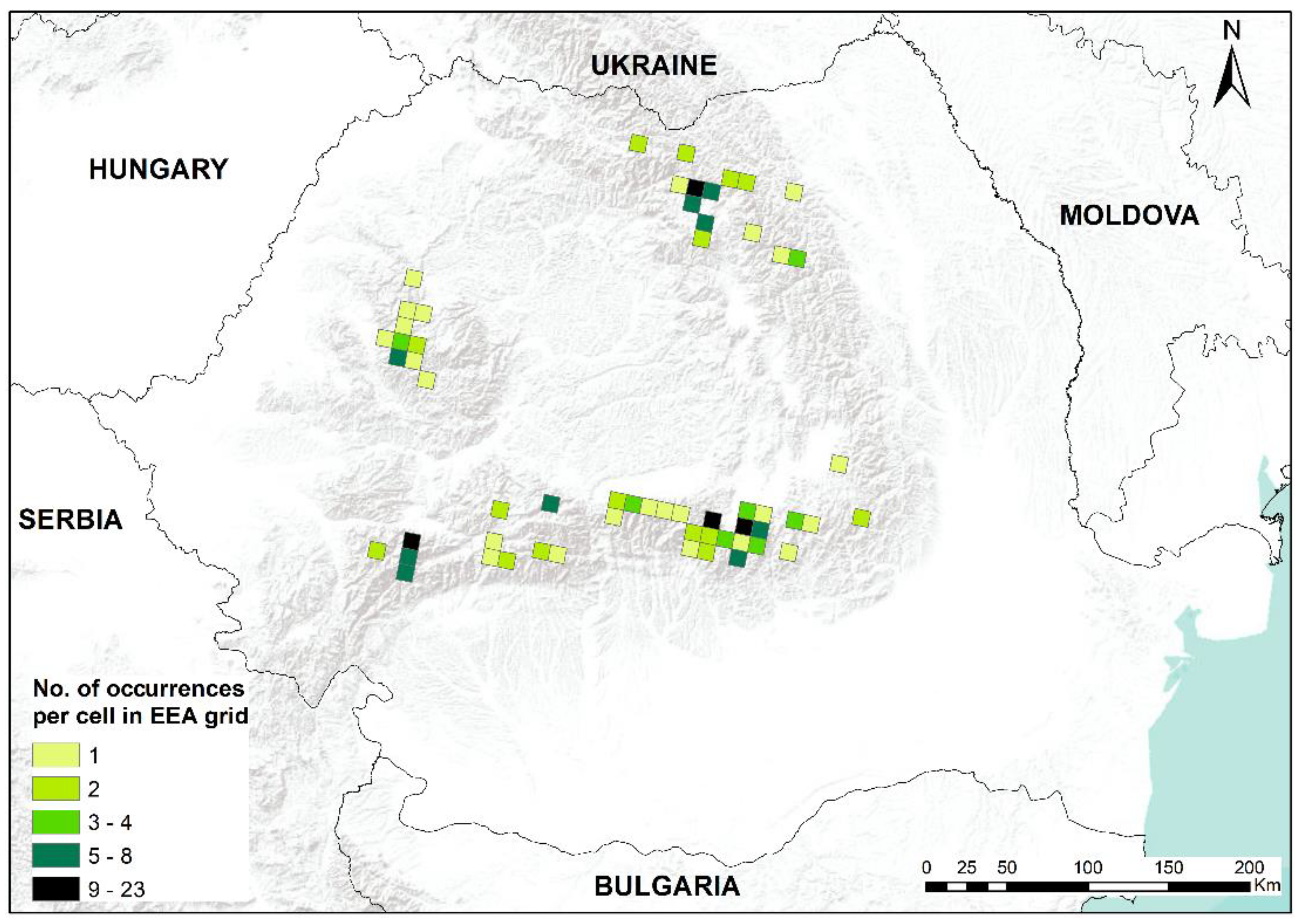

2.1. Current Species Distribution

- Suceava County, Obcina Mestecăniș, Cârlibaba Valley [17];

- Bistrița Aurie Valley [18];

- Munceii Rarăului, Dea, 850 m a.s.l., Valea Seacă, Poiana Mândrilă, 900–1000 m a.s.l. [7];

- Bârgău Mountains, Cucureasa Valley, 930–1230 m a.s.l. [20];

- Bistrița Mountains, Cristișor Peatbog [21];

- Neamț County, Olaru Hill, 450 m a.s.l., leg. C. Petrescu [24];

- Piatra Mare Mountain, 1200 m a.s.l., 13 September 1962, leg. & det. L. Vajda, sub B. indusiata Brid. [BP 66521], 1100 m a.s.l., 17 July 1963, leg. & det. L. Vajda, sub B. indusiata Brid. [BP 69257], “Șapte Scări” Waterfall, Tamina Waterfall, 1000–1600 m a.s.l. [25];

- Brașov County, Predeal, 1200 m a.s.l. [26];

- Piatra Craiului Mountains, Gulimana (Bulimani) Valley, 1000 m a.s.l., as B. indusiata Brid., on rotten wood, 1100 m a.s.l., on rotten wood, 1150 m a.s.l., on rotten wood, Podul lui Călineț, western slope, 1020 m a.s.l., as B. indusiata, on rotten wood, Podul lui Călineț, 1050 m a.s.l., on soil [28,29], Curmătura, towards Poiana Zănoaga, 1300–1600 m a.s.l., as B. indusiata [15,19], Poiana Zănoaga, 1500 m a.s.l., 2 September 1962, leg. & det. L. Vajda, sub B. indusiata [BP 66520], Poiana Zănoaga, 1300 m a.s.l., 2 September 1962, leg. & det. L. Vajda, sub B. indusiata [BP 66522], Șpirlea Valley, leg. O.G. Pop, det. R. Wallfisch [19];

- Cibin Mountains, Păltiniș, 1100 m a.s.l. [30], Bătrâna Mountains, 1700 m a.s.l., 11 July 1963, leg. & det. L. Vajda [BP 69255];

- Căpățânii Mountains, Repedea Valley [31];

- Parâng Mountains, Mija Stream [32];

- Apuseni Mountains, Vlădeasa Mountains, Valea Seacă, Între Munți, 19 September 1902, leg. & det. I. Györffy, sub B. indusiata Brid. [BP 88988] [33]; near Lăpuș, 900–1000 m a.s.l. [34]; Drăganului Valley, Trainișu, 6 June 1963, leg. & det. L. Vajda, sub B. indusiata [BP 69375] [25]; Vârciorog Valley, Arieşeni, 780 m a.s.l., 13 September 1996, leg. & det. I. Goia, Scărișoara Cave, 950 m a.s.l., 11 August 1996, leg. & det. I. Goia, Morii Valley, 950 m a.s.l., 7.08.1994, leg. & det. I. Goia, Goieștilor Valley, 1340 m a.s.l., 15.04.1994, leg. & det. I. Goia, Șaua Ursoaia, 900 m a.s.l., 12 August 1996 [35]; Galbena Valley, 780, 900 m a.s.l., 12 September 1996 [35,36]; Someșul Cald River, on decaying wood, 1998–2000 [37]; Vârciorog Valley, Arieşeni, 950 m a.s.l., 3 June 1995, leg. & det. I. Goia, between Gheţar and Ocoale, 1230 m a.s.l., 12 August 1996, leg. & det. I. Goia, Galbena Valley, Arieșeni, 870 m a.s.l., 1150 m a.s.l., 12 September1996, leg. & det. I. Goia, Iarba Rea Valley, Gârda, 980 m a.s.l., 25 August 1996, leg. & det. I. Goia [37,38];

- Rodna Mountains, Pietroasa, 47°36′35.3″ N, 24°39′01.3″ E, 1500 m a.s.l., 10 September 2021, det. G. Tamas;

- Suceava County, Dorna Valley, Poiana Stampei Peatbog, 47°18′10.86″ N, 25°08′03.84″ E, 905 m a.s.l., det. G. Tamas, C.-C. Bîrsan & M.C. Ion, on spruce rotten woods, 3 logs, 47°18′10.5″ N, 25°08′04.1″ E, 906 m a.s.l., 23 September 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, F.-E. Helepciuc, A.-M. Moroșanu, C.-C. Bîrsan, M.-M. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas & G-R. Nicoară; on spruce rotten woods, 4 logs, 47°17′40″ N, 25°07′14″ E, 920 m a.s.l., 17 October 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-M. Ion, C.-C. Bîrsan & M.-M. Ștefănuț, 13 December 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț & A.-M. Moroșanu (Figure 7); Bahnele Bancului 2, Bancului Valley, on rotten wood, one log, 47°23′43.8″ N, 25°11′27.2″ E, 895 m a.s.l., 23 June 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț & C.-C. Bîrsan; Teșna Valley, on rotten wood, 4 logs, 47°21′38.3″ N, 25°06′10.8″ E, 885 m a.s.l., 24 September 2022, det. M.-M. Ștefănuț, A.-M. Moroșanu, F.-E. Helepciuc, C.-C. Bîrsan & S. Ștefănuț; Cucureasa Valley, on rotten woods, spruce wood: 20 logs, beech tree wood: one log, alder tree wood (Alnus incana (L.) Moench): one log, 47°22′18″ N, 25°05′31″ E, 848–910 m a.s.l., 24 September 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, A.-M. Moroșanu, F.-E. Helepciuc, C.-C. Bîrsan & M.-M. Ștefănuț; Oușoru Mountain, on spruce rotten woods, 4 logs, 47°22′53″ N, 25°13′51″ E, 1070 m a.s.l., 4 logs, 47°22′31″ N, 25°14′13″ E, 944 m a.s.l., 16 October 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-M. Ion, C.-C. Bîrsan & M.-M. Ștefănuț;

- Giumalău Mountain, Codrul Secular Giumalău Reserve, 47°26′40.53″ N, 25°27′39.78″ E, 1240 m a.s.l., 1 September 2008, det. S. Ștefănuț, Codrul Secular Giumalău Reserve, 47°26′45.3″ N, 25°27′49.4″ E, 1294 m a.s.l., 19 September 2018, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas & C.-C. Bîrsan (Figure 8);

- Călimani Mountains, Haita Valley, on rotten woods, 4 logs, 47°11′21″ N, 25°15′04″ E, 1096–1102 m a.s.l., 4 logs, 47°10′15″ N, 25°14′44″ E, 1132–1170 m a.s.l., 25 September 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, A.-M. Moroșanu, F.-E. Helepciuc, C.-C. Bîrsan, M.-M. Ștefănuț & G. Tamas; Călimani National Park, on rotten wood, one log, 47°06′30.9″ N, 25°14′39.8″ E, 1297 m a.s.l., one logs, 47°07′44.4″ N, 25°14′56.7″ E, 1545 m a.s.l., 14 October 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-M. Ion, C.-C. Bîrsan, M.-M. Ștefănuț & G. Tamas;

- Ceahlău Mountain, Ceahlău Peak, 46°59′39.1″ N, 26°13′30.2″ E, 948 m a.s.l., Bucur Valley, 46°59′45.5″ N, 25°55′52.3″ E, 948 m a.s.l., Durău Valley, 46°59′51.8″ N, 25°56′06.7″ E, 922 m a.s.l., 11 August 2021, det. G. Tamas & C.-C. Bîrsan;

- Vrancea Mountains, Covasna Valley, 45°49′32.3″ N, 26°13′30.2″ E, 819 m a.s.l., 29 May 2021, det. G. Tamas;

- Penteleu Mountain, Brebu Valley, on rotten wood, two logs, 45°35′09.9″ N, 26°27′42.7″ E, 1105 m a.s.l., 11 July 2022, det. C.-C. Bîrsan & S. Ștefănuț;

- Siriu Mountain, Siriu Mare Valley, 45°29′34.3″ N, 26°05′11.8″ E, 975 m a.s.l., on rotten alder wood (Alnus incana (L.) Moench), one log, 7 October 2021, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan, G. Tamas & G.-R. Nicoară;

- Ciucaș Mountains, Prundului Valley, on rotten wood, two logs, 45°32′32.0″ N, 25°55′26.5″ E, 1014 m a.s.l., 45°32′30.6″ N, 25°55′26.0″ E, 1066 m a.s.l., Strâmbu Valley, on rotten wood, two logs, 45°32′15.9″ N, 25°57′59.0″ E, 1209 m a.s.l., 45°32′15.4″ N, 25°57′54.2″ E, 1246 m a.s.l., 9 September 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan & G.-R. Nicoară;

- Grohotiș Mountains, Bobului Valley, on rotten wood, one log, 45°24′12.0″ N, 25°53′14.2″ E, 1200 m a.s.l., 1 July 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan & G. Tamas;

- Piatra Mare Mountain, 45°32′08.3″ N, 25°35′27.8″ E, 869 m a.s.l., 45°32′08.2″ N, 25°35′28.0″ E, 871 m a.s.l., 45°32′06.2″ N, 25°35′34.6″ E, 905 m a.s.l., 45°32′05.0″ N, 25°35′37.0″ E, 912 m a.s.l., 45°32′05.1″ N, 25°35′37.9″ E, 914 m a.s.l., 45°32′04.9″ N, 25°35′37.6″ E, 916 m a.s.l., 17 December 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan & G. Tamas.

- Brașov County, Predeal, 45°31′26.5″ N, 25°33′08.6″ E, 1065 m a.s.l., 17 December 2020, det. C.-C. Bîrsan, G. Tamas & S. Ștefănuț;

- Postăvaru Mountain, Lamba Mare Valley, on rotten wood, one log, 45°34′47.3″ N, 25°34′30.9″ E, 1082 m a.s.l., one log, 45°34′46.9″ N, 25°34′28.4″ E, 1097 m a.s.l., 29 July 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas & C.-C. Bîrsan; Vanga Mare Valley, 45°34′05.0″ N, 25°33′20.0″ E, 1608 m a.s.l., 7 June 2021, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan G. Tamas & G.-R. Nicoară;

- Baiului Mountains, Rea Valley, on rotten wood, one log, 45°21′52.9″ N, 25°36′00.4″ E, 1076 m a.s.l., two logs, 45°21′53.1″ N, 25°35′59.8″ E, 1077 m a.s.l., 45°21′54.2″ N, 25°36′00.1″ E, 1087 m a.s.l., two logs, 45°21′54.8″ N, 25°36′00.3″ E, 1089 m a.s.l., 3 September 2020, det. C.-C. Bîrsan, G. Tamas, G.-R. Nicoară & S. Ștefănuț;

- Bucegi Mountains, Mălăiești Valley, on rotten woods, 45°29′18.9″ N, 25°28′27.0″ E, 973 m a.s.l., 45°29′19.2″ N, 25°28′26.6″ E, 990 m a.s.l., 45°29′18.0″ N, 25°28′26.7″ E, 999 m a.s.l., 45°29′03.8″ N, 25°28′30.8″ E, 1051 m a.s.l., 45°29′03.7″ N, 25°28′31.0″ E, 1058 m a.s.l., 45°29′03.5″ N, 25°28′30.7″ E, 1060 m a.s.l., 45°29′02.5″ N, 25°28′29.6″ E, 1063 m a.s.l., 45°29′00.5″ N, 25°28′29.1″ E, 1067 m a.s.l., 45°29′00.3″ N, 25°28′28.6″ E, 1067 m a.s.l., 45°28′59.0″ N, 25°28′26.8″ E, 1076 m a.s.l., 17 June 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas & C.-C. Bîrsan; Guțanu Valley, one log, 45°25′05.2″ N, 25°23′50.3″ E, 1573 m a.s.l., one log, 45°25′06″ N, 25°23′50.2″ E, 1573 m a.s.l., Culmea Grohotișului, one log, 45°24′12.5″ N, 25°23′04.1″ E, 1520 m a.s.l., 10 October 2020, det. G. Tamas; Cota 1400, one log, 45°21′14.6″ N, 25°30′55.5″ E, 1440 m a.s.l., 12 August 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, M.-M. Ștefănuț; Peleș Valley, one log, 45°21′41.5″ N, 25°31′44.2″ E, 1044 m a.s.l., 13 August 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, M.-M. Ștefănuț; near Cuibul Dorului chalet, two logs, 45°19′12.7″ N, 25°30′51.5″ E, 1427 m a.s.l., 6 Sptember 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas, Nicoară G.-R. & C.-C. Bîrsan;

- Leaota Mountain, Crovului Gorges, one log, 45°24′04.0″ N, 25°15′38.5″ E, 1012 m a.s.l., 30 October 2021, det. G.-R. Nicoară, one log, 45°23′31.9″ N, 25°16′36.9″ E, 1295 m a.s.l., 24 July 2022, det. G. Tamas;

- Piatra Craiului Mountains, near Garofița Pietrei Craiului chalet, beech forest, on soil, 45°30′45.74″ N, 25°10′23.57″ E, 1120 m a.s.l., Piscul Rece, 45°30′39.77″ N, 25°11′10.04″ E, 1350 m a.s.l., 9 July 2003, det. S. Ștefănuț; Șpirlea Valley, on rotten wood, one log, 45°32′25.80″ N, 25°11′38.40″ E, 1077 m a.s.l., 25 June 2019, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas, C-C. Bîrsan & M.C. Ion; Vlădușca Valley, on rotten wood, 3 logs, 45°32′52.20″ N, 25°11′45.30″ E, 1029 m a.s.l., on rotten wood, one log, 45°32′50.90″ N, 25°11′49.50″ E, 1040 m a.s.l., 16 July 2019, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas, C.-C. Bîrsan & M.-M. Ștefănuț (Figure 9); Podurilor Valley, 45°32′36.00″ N, 25°12′30.00″ E, 1360 m a.s.l., 17 July 2019, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas, C.-C. Bîrsan & M.-M. Ștefănuț; Padina Lancii Valley, 45°30′39.3″ N, 25°11′23.9″ E, 1417 m a.s.l., 27 July 2022, det. G. Tamas;

- Făgăraș Mountains, below Bârcaciu chalet, 45°36′58.30″ N, 24°28′45.00″ E, 1226 m a.s.l., 26 August 2015, det. S. Ștefănuț; Podragu Valley, near Turnuri chalet, 45°37′35.25″ N, 24°40′34.20″ E, 1500 m a.s.l., 29 August 2017, Arpașul Mare Valley, 45°38′32.91″ N, 24°40′19.88″ E, 1140 m a.s.l., 29 August 2017, det. S. Ștefănuț & C.-C. Bîrsan; Breaza Valley, 45°38′17.54″ N, 24°52′28.74″ E, 1103 m a.s.l., 25 July 2019, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas & C.-C. Bîrsan; Viștișoara Valley, 45°38′58.9″ N, 24°45′56.0″ E, 1120 m a.s.l., 19 August 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, G. Tamas, M. Vladimirescu & C.-C. Bîrsan; Boia Valley, 45°32′37″ N, 24°26′58″ E, 1610 m a.s.l., 28 September 2020, det. G.-R. Nicoară; Șerbota Valley, 45°36′35.8″ N, 23°57′14.2″ E, 1163 m a.s.l., 23 May 2021, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan, A.-M. Moroșanu, F.-E. Helepciuc & G. Tamas; Arpășel Valley, 45°39′19.6″ N, 24°37′34.4″ E, 921 m a.s.l., 9 September 2021, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan, A.-M. Moroșanu & F.-E. Helepciuc; Dâmbovița Valley, 45°34′14.4″ N, 25°03′36.9″ E, 1163 m a.s.l., 11 November 2022, det. S. Ștefănuț;

- Iezer-Păpușa Mountains, Păpușa Mountain, Cuca Valley, on rotten wood, one log, 45°28′23.9″ N, 25°02′40.1″ E, 1180 m a.s.l., 8 July 2020, det. C.-C. Bîrsan, G. Tamas & S. Ștefănuț; Valea Rea, 45°26′31.6″ N, 25°03′23″ E, 1080 m a.s.l., 31 October 2021, det. G. Tamas;

- Cindrel Mountains, Steaza Valley, 45°40′07.4″ N, 23°57′17.4″ E, 1122 m a.s.l., 45°40′07.3″ N, 24°31′14.2″ E, 1131 m a.s.l., Valea lui Andrei, 45°39′16.1″ N, 23°57′11.8″ E, 1263 m a.s.l., 22 May 2021, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan, A.-M. Moroșanu, F.-E. Helepciuc & G. Tamas;

- Șureanu Mountain, Cugir Valley, 45°35′43.6″ N, 23°30′52.3″ E, 1484 m a.s.l., 45°35′42.3″ N, 23°30′50.6″ E, 1486 m a.s.l., 29 July 2021, det. G. Tamas, S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan & G.-R. Nicoară;

- Căpățânii Mountains, Repedea Valley, 45°19′59.0″ N, 23°52′27.1″ E, 1245 m a.s.l., 45°19′58.1″ N, 23°52′25.2″ E, 1279 m a.s.l., 26 July 2021, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan, G. Tamas & G.-R. Nicoară;

- Parâng Mountains, Lotru Valley, on rotten woods, two logs, 45°21′52.21″ N, 23°37′16.45″ E, 1637 m a.s.l., one log, 45°21′55.26″ N, 23°37′14.20″ E, 1626 m a.s.l., 29 August 2020, det. G. Tamas & G.-R. Nicoară; Roșiile Valley, 45°21′52.21” N, 23°37′16.45″ E, 1637 m a.s.l., one log, 45°22′10.24″ N, 23°33′53.51″ E, 1510 m a.s.l., 25 August 2022, det. G. Tamas;

- Retezat Mountains, Pietrele Valley, on rotten woods, 45°24′20.5″ N, 22°53′11.7″ E, 1432 m a.s.l., 45°24′25.4″ N, 22°53′17.0″ E, 1451 m a.s.l., Galeș Valley, on rotten woods, 45°24′19.6″ N, 22°53′28.0″ E, 1461 m a.s.l., 45°24′19.7″ N, 22°53′28.3″ E, 1465 m a.s.l., 45°24′17.2″ N, 22°53′28.7″ E, 1480 m a.s.l., 45°24′17.3″ N, 22°53′29.0″ E, 1479 m a.s.l., 45°24′16.9″ N, 45°24′16.9″ N, 1481 m a.s.l., 45°24′15.1″ N, 22°53′29.6″ E, 1487 m a.s.l., 45°24′07.4″ N, 22°53′35.3″ E, 1509 m a.s.l., 45°24′05.2″ N, 22°53′39.7″ E, 1527 m a.s.l., 45°24′09.6″ N, 22°53′45.2″ E, 1562 m a.s.l., on soil, 45°24′05.5″ N, 22°53′38.8″ E, 1521 m a.s.l., 23 July 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, C.-C. Bîrsan, G. Tamas & G.-R. Nicoară; Scorota Valley, on rotten woods, 45°16′51.0″ N, 22°53′42.5″ E, 1168 m a.s.l., 45°16′55.3″ N, 22°53′30.4″ E, 1206 m a.s.l., 45°16′55.1″ N, 22°53′30.4″ E, 1210 m a.s.l., 45°16′56.0″ N, 22°53′28.8″ E, 1215 m a.s.l., 45°17′00.1″ N, 22°53′29.3″ E, 1227 m a.s.l., 45°17′05.6″ N, 22°53′34.1″ E, 1240 m a.s.l., 45°17′06.0″ N, 22°53′33.8″ E, 1241 m a.s.l., 45°17′06.9″ N, 22°53′35.7″ E, 1245 m a.s.l., Iarului Valley, 45°16′05.3″ N, 22°51′18.1″ E, 1332 m a.s.l., 45°16′07.3″ N, 22°51′12.9″ E, 1357 m a.s.l., 45°16′07.3″ N, 22°51′12.1″ E, 1359 m a.s.l., 45°16′09.4″ N, 22°51′10.7″ E, 1369 m a.s.l., 45°16′12.6″ N, 22°51′10.8″ E, 1374 m a.s.l., 45°16′12.9″ N, 22°51′10.8″ E, 1382 m a.s.l., 45°16′13.1″ N, 22°51′10.4″ E, 1381 m a.s.l., 13 August 2020, det. C.-C. Bîrsan;

- Țarcu Mountains, Mătania Valley, on rotten woods, two logs, 45°18′18.26″ N, 22°39′16.1″ E, 1241 m a.s.l., 45°18′17.6″ N, 22°39′15.0″ E, 1257 m a.s.l., 15 September 2020, det. S. Ștefănuț, G.-R. Nicoară, C.-C. Bîrsan & G. Tamas;

- Bihor County, Buciniș Valley, 46°26′31.2” N, 22°44′20.8″ E, 1227 m a.s.l., 18 July 2021, det. G. Tamas;

- Apuseni Mountains, Padiș, 46°34′33.99″ N, 22°42′12.31″ E, 1110 m a.s.l., 3 September 2007, det. S. Ștefănuț; Peștera Coiba Mare, 46°32′14.6″ N, 22°46′40.7″ E, 1100 m a.s.l., 19 July 2021, det. G. Tamas; Ghețarul Focul Viu, 46°34′30.01″ N, 22°40′54.2″ E, 1162 m a.s.l., 20 July 2021, det. G. Tamas; Avenul Bortig, 46°33′34.3″ N, 22°41′50.5″ E, 1164 m a.s.l., 20 July 2021, det. G. Tamas.

2.2. Habitat Suitability

2.3. Population and Conservation Status

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Occurrence Records

4.2. Model Preparation and Procedure

4.3. Conservation Status Assessment

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Directive Habitats. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1992, 206, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- Deme, J.; Erzberger, P.; Kovács, D.; Tóth, I.Z.; Csiky, J. Buxbaumia viridis (Moug. ex Lam. & DC.) Brid. ex Moug. & Nestl. in Hungary predominantly terricolous and found in managed forests. Cryptogam. Bryol. 2020, 41, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goia, I.; Gafta, D. Beech versus spruce deadwood as forest microhabitat: Does it make any difference to bryophytes? Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2019, 153, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Holá, E.; Vrba, J.; Linhartová, R.; Novozámská, E.; Zmrhalová, M.; Plasek, V.; Kucera, J. Thirteen years on the hunt for Buxbaumia viridis in the Czech Republic: Still on the tip of the iceberg? Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2014, 83, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hodgetts, N.G.; Lockhart, N. Checklist and country status of European bryophytes–update 2020. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 123. In National Parks and Wildlife Service; Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht: Dublin, Ireland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WWF Calls for A Public Debate on the Results of the Romanian National Forest Inventory. 2019. Available online: https://wwf.panda.org/wwf_news/?357022/debated-nfi (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Tarnavschi, I. Beitrag zur Oekologie und Phytosoziologie der Buxbaumia indusiata Bridel sowie zur Verbreitung von Buxbaumia aphylla L. und Buxbaumia indusiata Brid. Bul. Fac. De Ştiinţe Din Cernăuţi 1936, 10, 281–290. (In Romanian) [Google Scholar]

- Papp, C. Briofitele din Republica Socialistă România (determinator). Anal. Şti. Univ. "Al.I. Cuza" Iaşi–Biol. Monogr. 1967, 3, 1–319. [Google Scholar]

- Plămadă, E.; Dumitru, C. Flora Briologică a României. Clasa Musci 1; Presa Universitară Clujeană: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, G. Catalogul briofitelor din România. In Acta Botanica Horti Bucurestiensis; Lucrările Grădinii Botanice; University of Bucharest: București, Romania, 1998; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Mihăilescu, S.; Anastasiu, P.; Popescu, A. Ghidul de Monitorizare a Speciilor de Plante de Interes Comunitar din România; Editura Dobrogea: Constanta, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanut, S.; Goia, I. Checklist and Red List of Bryophytes of Romania. Nova Hedwig. 2012, 95, 59–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgetts, N.G. Checklist and Country Status of European Bryophytes–towards a New Red List for Europe: National Parks and Wildlife Service; Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht: Dublin, Ireland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brewczyński, P.; Grałek, K.; Bilański, P. Occurrence of the Green Shield-Moss Buxbaumia viridis (Moug.) Brid. in the Bieszczady Mountains of Poland. Forests 2021, 12, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pax, F. Grundzüge der Pflanzenverbreitung in den Karpathen; Engelmann: Leipzig, Germany, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ştefănuț, S. The Bryophytes of Rodna Mountains National Park (Transylvania-Maramureş, Romania). Transylv. Rev. Syst. Ecol. Res. 2010, 9, 53–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefureac, T.; Pascal, P. Contribuţion à la bryoflore de la Bukovine (Roumanie). Rev. Roum. Biol. Série Bot. 1970, 15, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, P.; Mititelu, D. Contribuţie la studiul vegetaţiei din bazinul Bistriţei Aurii (Jud. Suceava). Comunic. Şti. Inst. Pedagog. 1971, 331–363. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefureac, T. Cercetări sinecologice şi sociologice asupra bryophytelor din Codrul Secular Slătioara (Bucovina). An. Acad. Române. Mem. Secţiunii Ştiinţifice. 1941, 16, 1–197. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefureac, T.; Mihai, G.; Pascal, P. Cercetări briologice în rezervaţia forestieră Cucureasa (Vatra Dornei). St. Cerc. Biol. Ser. Biol. Veg. 1976, 28, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lungu, L. Analiza brioflorei din lunca Borcutului de la Cristişor-Neagra Broştenilor (Carpaţii Orientali). An. Univ. Bucureşti. Ser. Biol. Veg. 1973, 22, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Pascal, P.; Toma, M. Contribuţii la cunoaşterea brioflorei bazinelor Suha Mare şi Suha Mică (jud. Suceava). Anu. Muz. Ştiinţe Nat. Piatra Neamţ. Ser. Bot. Zool. 1977, 3, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefureac, T.; Pascal, P. Conspectul briofitelor din Bucovina. Stud. Comunicări Ocrotirea Nat. 1981, 5, 471–544. [Google Scholar]

- Papp, C. Contribution à la systématique des bryophyttes de la Moldavie, suivie de quelques considérations bryogéographiques. Ann. Sci. L’Université Jassy 1931, 17, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Boros, Á.; Vajda, L. Bryologische beiträge zur Kenntnis der Flora Transsilvaniens. Rev. Bryol. Lichénologique 1967, 35, 216–253. [Google Scholar]

- Loitlesberger, K. Verzeichnis der gelegentlich einer Reise im Jahre 1897 in den rumänischen Karpathen gesammelten Kryptogamen. Ann. Nat. Mus. Wien 1900, 15, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Radian, S.Ş. Contribuţiuni la flora bryologică a Romaniei. Bul. Erb. Inst. Bot. Din Bucureşti 1901, 1, 132–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefureac, T. Consideraţii bryologice asupra rezervaţiei naturale. Bul. Ştiinţific. Secţiunea Ştiinţe Biol. Agron. Geol. Geogr. 1951, 3, 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Dihoru, G.; Ștefănuț, S.; Wallfisch, R.; Pop, O.G. Bryophytes Flora of the Piatra Craiului Massif. In Research in the Piatra Craiului National Park 1; Pop, O.G., Vergheleţ, M., Eds.; Phoenix: Braşov, Romania, 2003; pp. 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gündisch, F. Beitrag zu einer Moosflora des Zibin-Gebirges. Stud. Comunicări. Ştiinţe Nat. 1977, 21, 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefureac, T.; Popescu, A.; Lungu, L. Noi contribuţii la cunoaşterea florei şi vegetaţiei bryophytelor din Valea Lotrului. Studii şi cercetări de biologie. Ser. Biol. Veg. 1959, 11, 7–61. [Google Scholar]

- Péterfi, M. Hunyadmegye lombosmohai. Hunyadmegyei Történelmi Régészeti Társulat Évkönyve 1904, 14, 73–116. [Google Scholar]

- Györffy, I. Négy ritkább növény új termőhelye Erdélyben.-Vier neue Standorte seltenerer Pflanzen in Siebenbürgen. Magy. Bot. Lapok 1903, 2, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Péterfi, M. Adatok a Biharhegység mohaflorájának ismeretéhez. Math. Természettudományi Közlemények 1908, 30, 261–332. [Google Scholar]

- Goia, I. Moosgesellschaften des Faulen Holzen im oberen Arieş-Becken (Kreis Alba, Rumänien). In Naturwissenschaftliche for-chungen über Siebenbürgen VI. Beiträge zur Geographie, Botanik, Zoologie und Paläontologie; Heltmann, H., Von Killyen, H., Eds.; Böhlau Verlag Köhn & Weimar: Vienna, Austria, 2000; pp. 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Goia, I.; Schumacker, R. Decaying wood communities from the upper basin of the Arieș River conserving rare and vulnerable bryophytes. Contrib. Bot. 2003, 38, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Goia, I.; Mătase, D. Bryofloristical research in the Someşul Cald Gorges. Contrib. Bot. 2001, 36, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Goia, I.; Schumacker, R. The Bryophytes from rotten wood in the Arieşului Mare Basin. Contrib. Bot. 2002, 37, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ştefănuț, S. Dinamica colonizării lemnului mort de către briofite în pădurile de molid. In Programul de Cercetare de Excelenţă 2005–2008. Mener 2008. Mediu; Universităţii Politehnice Bucureşti: București, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boros, Á. Briológiai adatok a Kárpátokból. Bot. Közlemények 1941, 38, 96–97. [Google Scholar]

- Boros, Á. Der Flora von Ungarn und der Karpaten. Acta Biol. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1951, 2, 369–409. [Google Scholar]

- IFN. The National Forest Inventory. 2019. Available online: https://roifn.ro/site/en/ (accessed on 9 May 2020).

- Deme, J.; Csiky, J. Development and survival of Buxbaumia viridis (Moug. ex DC.) Brid. ex Moug. & Nestl. sporophytes in Hungary. J. Bryol. 2021, 43, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Číhal, L.; Fialová, L.; Plášek, V. Species distribution model for Buxbaumia viridis, identifying new areas of presumed distribution in the Czech Republic. Acta Musei Sil. Sci. Nat. 2020, 69, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillet, A.; Hugonnot, V.; Pépin, F. The Habitat of the Neglected Independent Protonemal Stage of Buxbaumia viridis. Plants 2021, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, K. Substratum preference, spore output and temporal variation in sporophyte production of the epixylic moss Buxbaumia viridis. J. Bryol. 2002, 24, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropik, M.; Zechmeister, H.G.; Moser, D. Climate Variables Outstrip Deadwood Amount: Desiccation as the Main Trigger for Buxbaumia viridis Occurrence. Plants 2020, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, K.; Rydin, H. Ecophysiological constraints on spore establishment in bryophytes. Funct. Ecol. 2004, 18, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabovljević, M.S.; Ćosić, M.V.; Jadranin, B.Z.; Pantović, J.P.; Giba, Z.S.; Vujičić, M.M.; Sabovljević, A.D. The Conservation Physiology of Bryophytes. Plants 2022, 11, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infante, M.; Heras, P. Notes on the Herbivory on Buxbaumia viridis Sporophytes in the Pyrenees. Cryptogam. Bryol. 2018, 39, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.G.; Port, G.R.; Emmett, B.J.; Green, D.I. Development of a forecast of slug activity: Models to relate slug activity to meteorological conditions. Crop Prot. 1991, 10, 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, J.M.; Reise, H.; Skujienė, G. Life cycles and adult sizes of five co-occurring species of Arion slugs. J. Molluscan Stud. 2017, 83, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slotsbo, S.; Hansen, L.M.; Holmstrup, M. Low temperature survival in different life stages of the Iberian slug, Arion lusitanicus. Cryobiology 2011, 62, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitale, D.; Mair, P. Predicting the distribution of a rare species of moss: The case ofBuxbaumia viridis(Bryopsida, Buxbaumiaceae). Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. Asp. Plant Biol. 2017, 151, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCune, B. Improved estimates of incident radiation and heat load using non-parametric regression against topographic variables. J. Veg. Sci. 2007, 18, 751–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majasalmi, T.; Rautiainen, M. The impact of tree canopy structure on understory variation in a boreal forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 466, 118100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puletti, N.; Canullo, R.; Mattioli, W.; Gawryś, R.; Corona, P.; Czerepko, J. A dataset of forest volume deadwood estimates for Europe. Ann. For. Sci. 2019, 76, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öder, V.; Petritan, A.M.; Schellenberg, J.; Bergmeier, E.; Walentowski, H. Patterns and drivers of deadwood quantity and variation in mid-latitude deciduous forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 487, 118977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI. ArcGIS Release 10.7.1; ESRI: Redlands, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.L.; Bennett, J.R.; French, C.M. SDMtoolbox 2.0: The next generation Python-based GIS toolkit for landscape genetic, biogeographic and species distribution model analyses. PeerJ 2017, 5, e4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.; Oakleaf, J.; Cushman, S.A.; Theobald, D. An ArcGIS Toolbox for Surface Gradient and Geomorphometric Modeling, Version 2.0-0. 2014. Available online: http://evansmurphy.wix.com/evansspatial (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Naimi, B.; Hamm, N.A.; Groen, T.A.; Skidmore, A.K.; Toxopeus, A.G. Where is positional uncertainty a problem for species distribution modelling? Ecography 2014, 37, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; R version 4.2.1; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Chatterjee, S.; Hadi, A.S. Regression Analysis by Example; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Naimi, B.; Araújo, M.B. sdm: A reproducible and extensible R platform for species distribution modelling. Ecography 2016, 39, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eustace, A.; Esser, L.F.; Mremi, R.; Malonza, P.K.; Mwaya, R.T. Protected areas network is not adequate to protect a critically endangered East Africa Chelonian: Modelling distribution of pancake tortoise, Malacochersus tornieri under current and future climates. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0238669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUCN Standards and Petitions Committee. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Version 15.1. Prepared by the Standards and Petitions Committee. 2022. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/redlistguidelines (accessed on 11 January 2023).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030: Bringing Nature Back into Our Lives. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:a3c806a6-9ab3-11ea-9d2d-01aa75ed71a1.0001.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 11 January 2023).

| Method | MeanAUC | MeanTSS |

|---|---|---|

| GLM | 0.81 | 0.58 |

| RF | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| Maxent | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| BRT | 0.88 | 0.66 |

| MARS | 0.86 | 0.62 |

| SVM | 0.82 | 0.6 |

| Code | Name | Source | Relative Importance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| bio9 * | Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | - |

| bio10 * | Mean Temperature of Warmest Quarter | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | - |

| bio11 | Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | 11.4 |

| bio12 * | Annual Precipitation | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | - |

| bio16 * | Precipitation of Wettest Quarter | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | - |

| bio17 | Precipitation of Driest Quarter | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | 12.9 |

| bio18 | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | 8.1 |

| dem | Elevation | www.worldclim.org (accessed on 16 November 2022) | 16 |

| dist_river | Euclidean distance to nearest river | Calculated in ArcGIS | 1.2 |

| HLI | Heat Load Index | Calculated in ArcGIS | 3.3 |

| LAI | Leaf Area Index | https://land.copernicus.eu (accessed on 16 November 2022) | 3 |

| tree_cover | Percentage tree cover | https://land.copernicus.eu (accessed on 16 November 2022) | 3.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ștefănuț, S.; Ion, C.M.; Sahlean, T.; Tamas, G.; Nicoară, G.-R.; Vladimirescu, M.; Moroșanu, A.-M.; Helepciuc, F.-E.; Ștefănuț, M.-M.; Bîrsan, C.-C. Population and Conservation Status of Buxbaumia viridis (DC.) Moug. & Nestl. in Romania. Plants 2023, 12, 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030473

Ștefănuț S, Ion CM, Sahlean T, Tamas G, Nicoară G-R, Vladimirescu M, Moroșanu A-M, Helepciuc F-E, Ștefănuț M-M, Bîrsan C-C. Population and Conservation Status of Buxbaumia viridis (DC.) Moug. & Nestl. in Romania. Plants. 2023; 12(3):473. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030473

Chicago/Turabian StyleȘtefănuț, Sorin, Constanța Mihaela Ion, Tiberiu Sahlean, Gabriela Tamas, Georgiana-Roxana Nicoară, Mihnea Vladimirescu, Ana-Maria Moroșanu, Florența-Elena Helepciuc, Miruna-Maria Ștefănuț, and Constantin-Ciprian Bîrsan. 2023. "Population and Conservation Status of Buxbaumia viridis (DC.) Moug. & Nestl. in Romania" Plants 12, no. 3: 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030473

APA StyleȘtefănuț, S., Ion, C. M., Sahlean, T., Tamas, G., Nicoară, G.-R., Vladimirescu, M., Moroșanu, A.-M., Helepciuc, F.-E., Ștefănuț, M.-M., & Bîrsan, C.-C. (2023). Population and Conservation Status of Buxbaumia viridis (DC.) Moug. & Nestl. in Romania. Plants, 12(3), 473. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12030473