Abstract

Anthocyanins are water-soluble pigments found in plants. They exist in various colors, including red, purple, and blue, and are utilized as natural colorants in the food and cosmetics industries. The pharmaceutical industry uses anthocyanins as therapeutic compounds because they have several medicinal qualities, including anti-obesity, anti-cancer, antidiabetic, neuroprotective, and cardioprotective effects. Anthocyanins are conventionally procured from colored fruits and vegetables and are utilized in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. However, the composition and concentration of anthocyanins from natural sources vary quantitively and qualitatively; therefore, plant cell and organ cultures have been explored for many decades to understand the production of these valuable compounds. A great deal of research has been carried out on plant cell cultures using varied methods, such as the selection of suitable cell lines, medium optimization, optimization culture conditions, precursor feeding, and elicitation for the production of anthocyanin pigments. In addition, metabolic engineering technologies have been applied for the hyperaccumulation of these compounds in varied plants, including tobacco and arabidopsis. In this review, we describe various strategies applied in plant cell and organ cultures for the production of anthocyanins.

1. Introduction

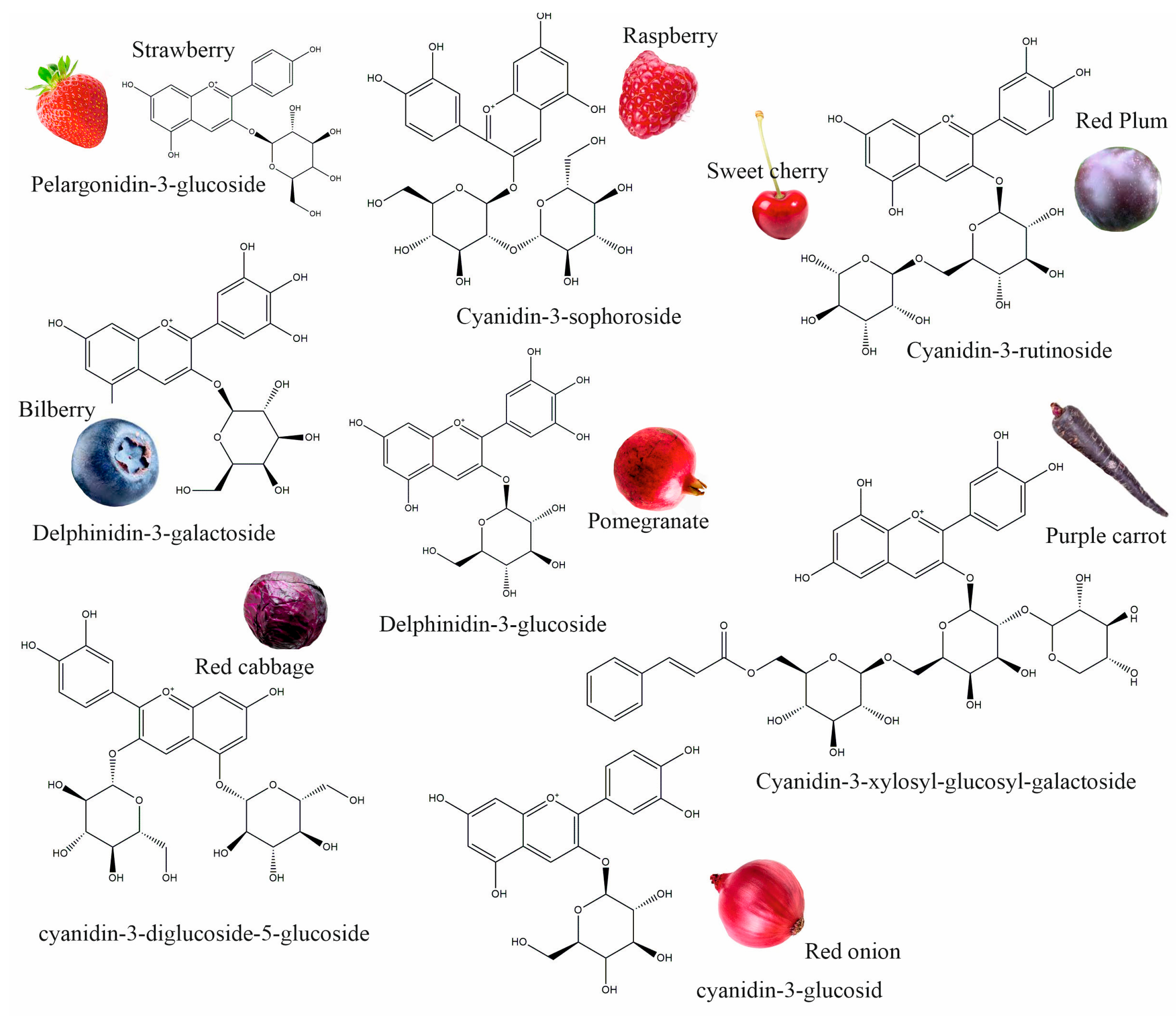

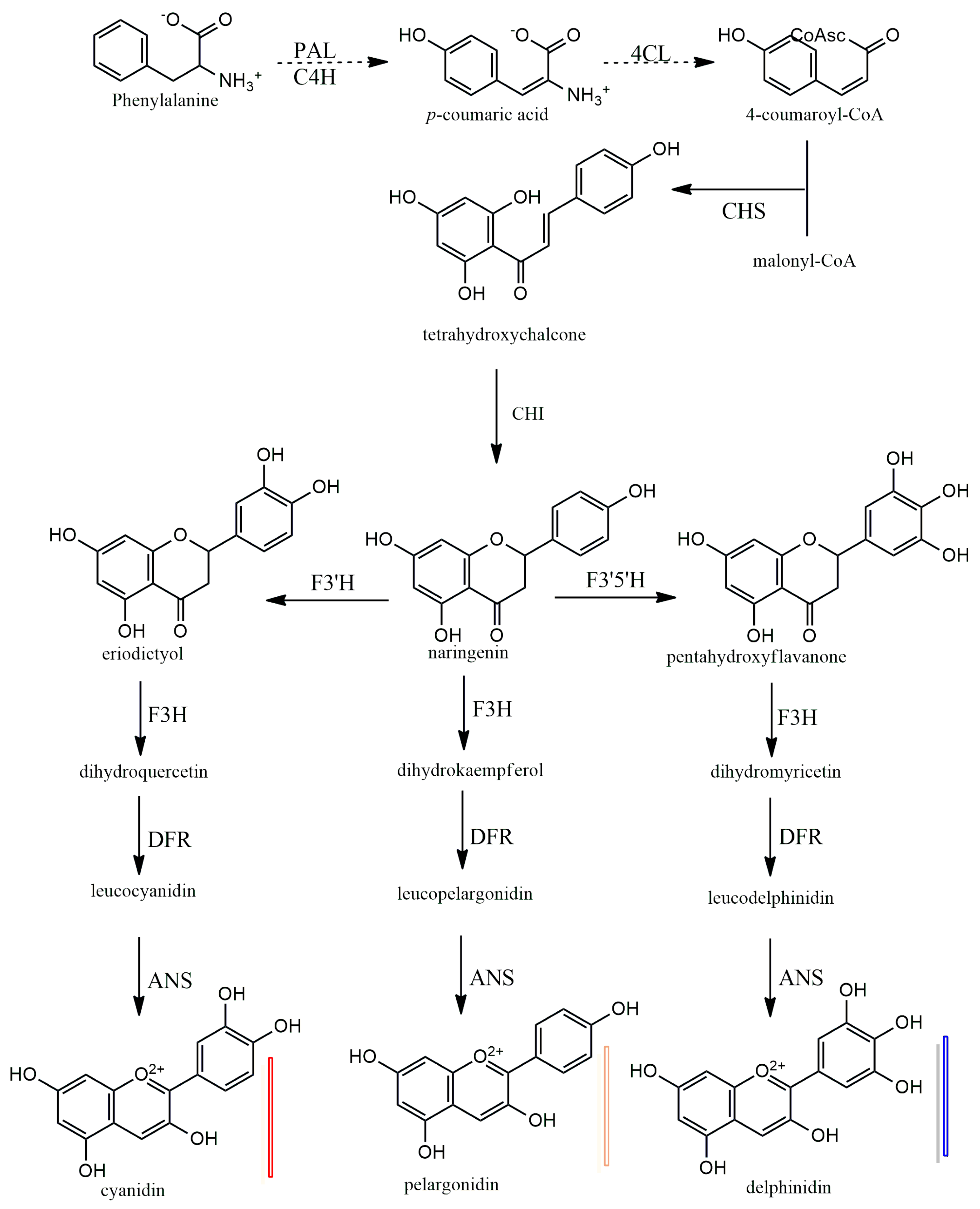

Anthocyanins are flavonoid compounds that contain water-soluble pigments in red, pink, purple, and blue colors. They are naturally found in plants, especially flowers, fruits, and tubers, such as red rose, blue rosemary, lavender, grapes, strawberries, raspberries, red plums, bilberries, blackberries, pomegranates, sweet cherry, eggplant, red onions, red cabbage, purple carrots, and others (Figure 1) [1,2]. Additionally, black grains and cereals, including black rice, black bean, and black soybean, and leaf vegetables, such as red amaranth, red spinach, and red leaf lettuce, are rich in anthocyanins; these could be used as a source of natural colorants and functional foods [3,4]. As natural colorants, anthocyanins have demonstrated many health benefits; they have antioxidant, anticancer, antidiabetic, anti-obesity, antimicrobial, neuroprotective, and cardioprotective properties, and can improve vision health; therefore, anthocyanins extracted from edible plants have been used in pharmaceuticals [5].

Figure 1.

Different plant sources of anthocyanins.

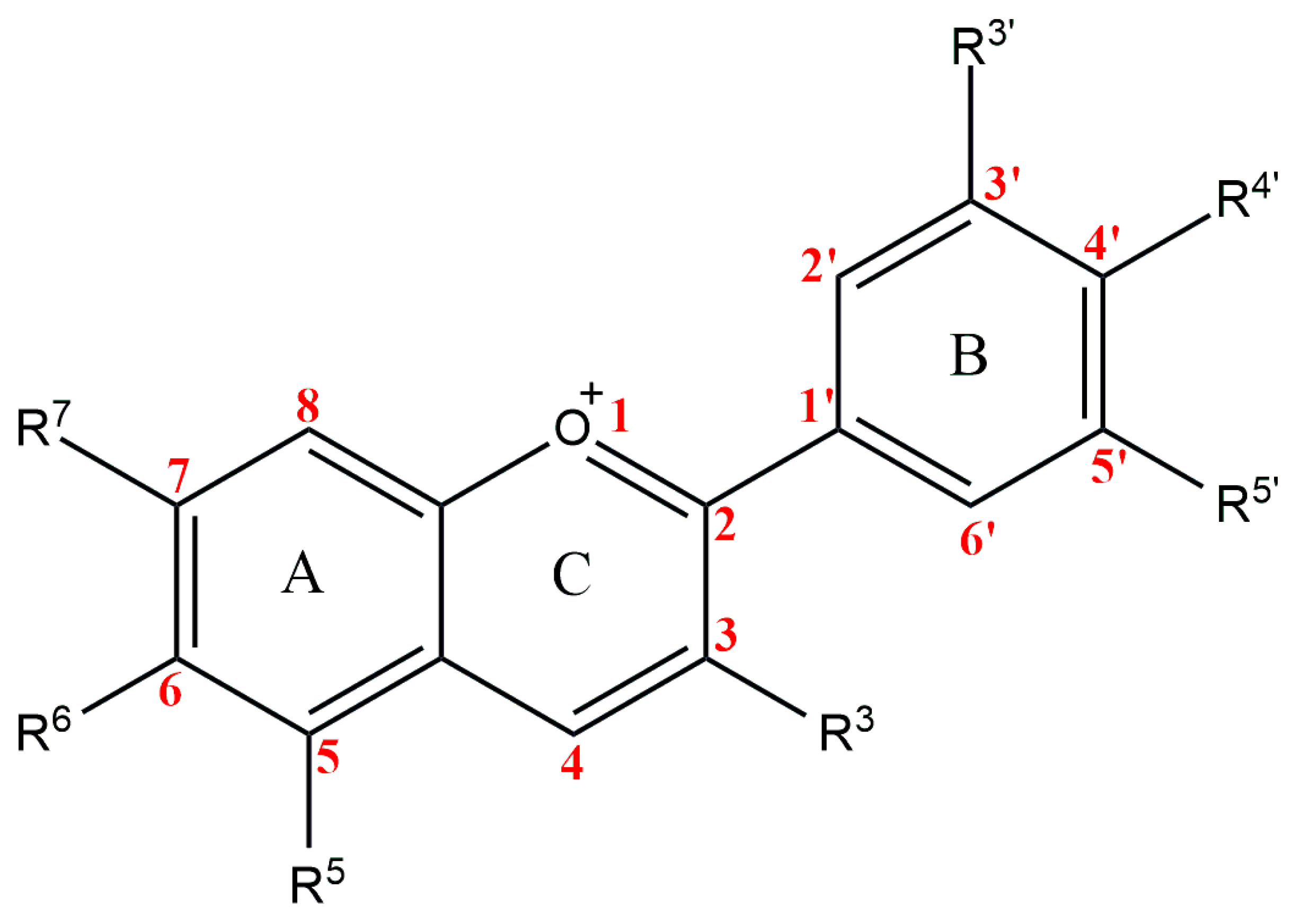

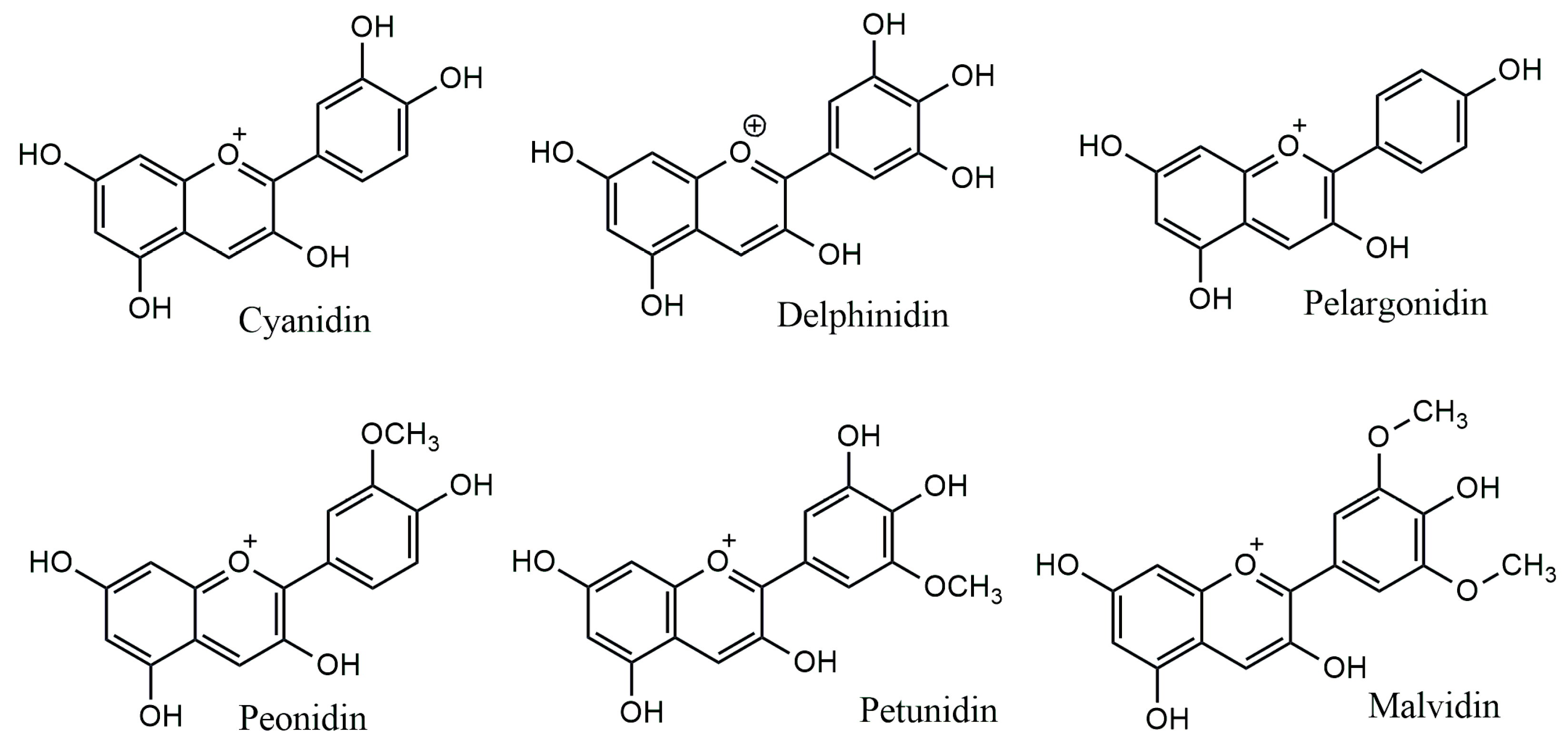

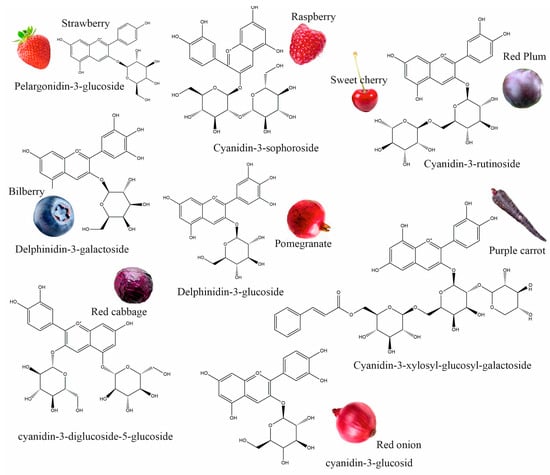

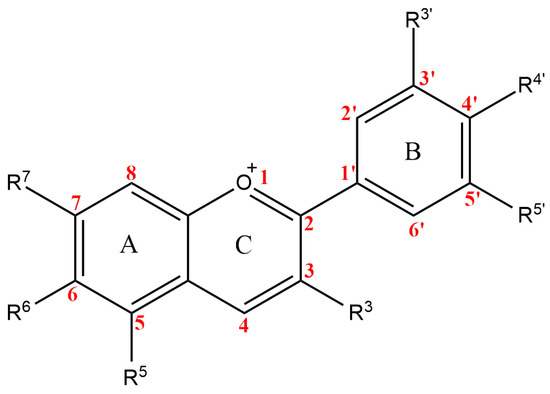

The anthocyanidins are made up of an aromatic ring [A] bound to an oxygen-containing heterocyclic ring [C], which is surrounded by a third aromatic ring through a carbon–carbon bond [B] [6] (Figure 2). The term “anthocyanins” refers to the glycoside form of anthocyanidins. Several anthocyanidins have been reported in plants; they differ in terms of the number and position of hydroxyl and/or methyl ether groups [7]. The predominant anthocyanidins found in plants are cyanidin, delphinidin, malvidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, and petunidin (Figure 3), which are present in 80% of pigmented leaves, 69% of pigmented fruits, and 50% of flowers [8]. In nature, these aglycones are attached to sugars and can potentially be further acylated by aliphatic or aromatic acids. The fact that simple anthocyanidins are rarely encountered in nature can be explained by the fact that both glycosylation and acylation increase anthocyanin stability [9].

Figure 2.

Basic anthocyanin structure.

Figure 3.

Major anthocyanidins from plants.

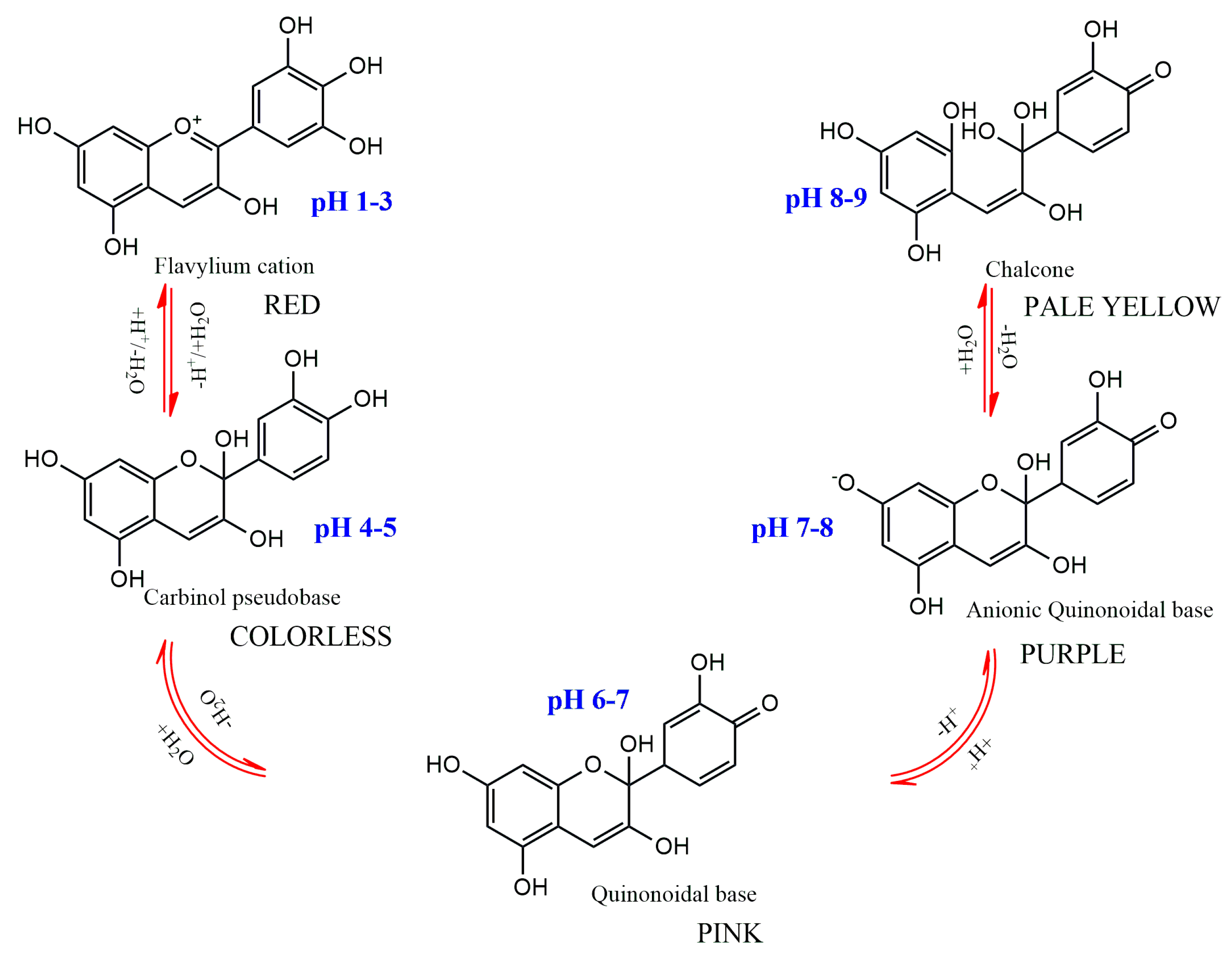

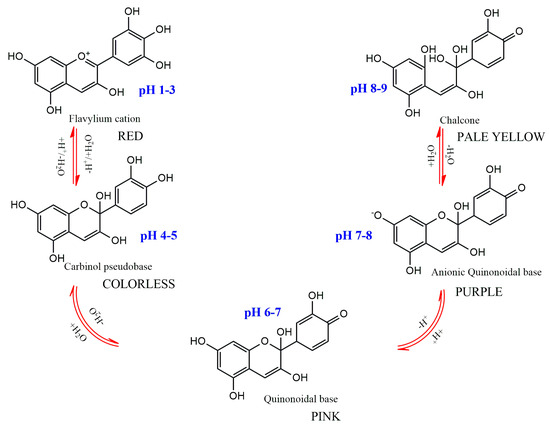

The substitution pattern of the anthocyanidin’s B-ring, the degree of glycosylation, the type and degree of esterification of the saccharides with aliphatic and aromatic acids, as well as the pH, temperature, solvent, and presence of other pigments, are the primary factors influencing color variations among anthocyanins [7]. The pH dependence of anthocyanins’ color is one of their main traits (Figure 4). They have a red hue in an aqueous solution at pH 1–3, produce a colorless carbinol pseudo base at pH 5, are pink at pH 6–7, are blue-purple quinoidal bases at pH 7–8, and are pale yellow at pH 8–9. A number of enzymes, light, oxygen, metal ions, and other variables can potentially affect color alteration [1,7].

Figure 4.

Structural transformations of anthocyanins in aqueous medium with different pH.

Since anthocyanins are naturally occurring food colorants with appealing properties, the food industry has long used them. Due to legislative limitations on some synthetic red dyes, the food industry is especially in need of water-soluble natural red colorants [10]. Anthocyanins’ relative volatility and interactions with other food matrix elements have hindered their commercial use as food colorants. The structure and concentration of anthocyanin, as well as pH, temperature, light, oxygen, solvents, and the presence of other flavonoids, proteins, and metallic ions, all have an impact on its stability [1]. This is why a major area of recent research has been the chemical stabilization of anthocyanins.

It has been demonstrated that acylation and co-pigmentation improve anthocyanin stability. The stability of anthocyanins can be increased by a number of techniques, including light preservation and oxygen exclusion. New food colorants with improved stability, bioavailability, and solubility have been made possible in recent years by the microencapsulation of anthocyanins [1,11].

Due to their many applications, anthocyanins are typically isolated from a variety of vegetables (like purple/black carrots) and fruit pulp (like grapes) and are used in the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries. However, cultivars, growing conditions, area, cultivation methods, maturity, processing, and storage all affect the anthocyanin content of fruits and vegetables [1]. Due to the conventional method’s inability to complete direct extraction from plant raw materials and meet the growing global demand for anthocyanins, significant research efforts have resulted in the development of more effective alternative plant in vitro cultures as well as the novel production of anthocyanins through the use of metabolic engineering [12,13]. We present here an overview of the different methods that have been discovered and applied to enhance anthocyanin synthesis through the use of plant in vitro cultures and metabolic engineering.

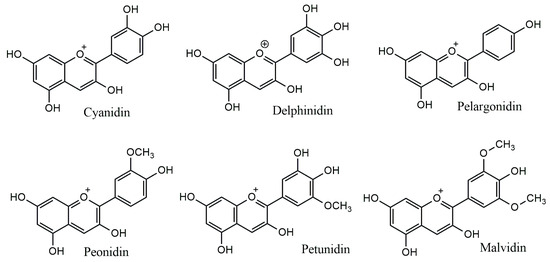

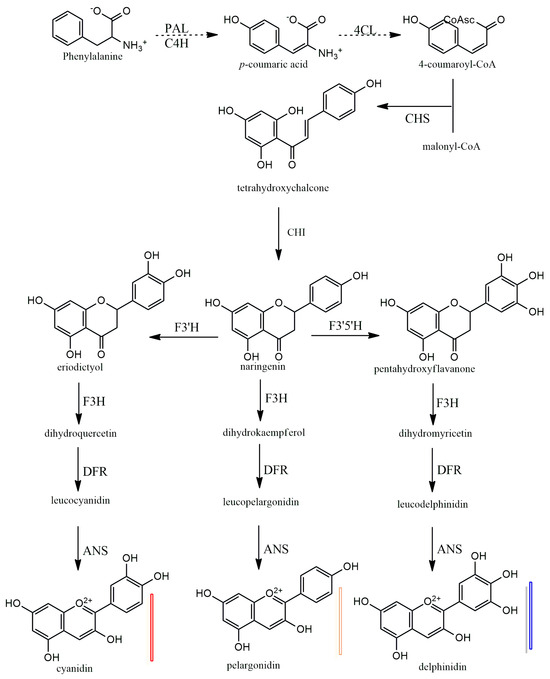

2. Biosynthesis of Anthocyanins

Anthocyanins have a 15-carbon base structure comprised of two phenyl rings (called A- and B-rings) connected by a three-carbon bridge that usually forms a third ring (called the C-ring) (Figure 2). Most anthocyanins are derived from just three basic anthocyanidin types: pelargonidin, cyanidin, and delphinidin. The precursor molecule for anthocyanin biosynthesis is phenylalanine; initially, phenylalanine is converted into 4-coumaroyl-coenzyme A, which is the key substrate for the biosynthesis of flavonoids, the synthesis of 4-coumaroyl-coenzyme A is catalyzed by the phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), cinnamate-4-hydroxylase (C4H) and 4-coumaroyl: CoA ligase (4CL) enzymes (Figure 5). Subsequently, there will be a synthesis of a chalcone molecule, usually naringenin-chalcone (2′,4,4′,6-tetrahydroxychalcone, THC), which is formed by the condensation of one molecule of 4-coumaroyl-CoA and three molecules of malonyl-CoA that are catalyzed by chalcone synthase (CHS). THC is an unstable molecule that is involved in isomerization for the formation of naringenin-flavanone; this reaction is catalyzed by chalcone isomerase (CHI). Naringenin-flavanone is the base molecule for the synthesis of flavones and flavanols. In the subsequent steps, there will be hydroxylation of the B ring of naringenin-flavanone, which is responsible for coloration, and an increase in hydroxylation, which causes a significant change in color from the extreme magenta to the blue end of the spectrum [14,15,16]. Hydroxylation of naringenin-flavanone is catalyzed by flavanone-3-hydroxylase (F3′H) and flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylases (F3′5′H); both are members of the Cytochrome P450 family (Cyt P450). Cyt P450 uses molecular oxygen and NADPH as cofactors and dihydroflavonol dihydrokaempferol (DHK) as a substrate to catalyze hydroxylation at 3- and 5- of the B ring to produce dihydroquercetin (DHQ, which is a precursor of cyanidin), dihydrokaempferol (DHK, which is the precursor of pelargonidin), and dihydromyricetin (DHM, which is the precursor of delphinidin), respectively (Figure 5). Both F3H and F3′5′H hydroxylases play a major role in the metabolism of flavonoids (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Biosynthesis of plant anthocyanidins. PAL—phenylalanine amino-lyase, C4H—cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, 4CL—4-coumarate: CoA ligase, CHS—chalcone synthase, CHI—chalcone isomerase, F3H—flavanone 3-hydroxylase, F3′H—flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase, F3′5′H—flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase, DFR—dihydro flavanol 4-reductase, ANS—anthocyanidin synthase.

In the last stages of anthocyanidin formation, dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) enzyme converts dihydromyrcetin (DHM), dihydroquercetin (DHQ), and dihydrokaempferol (DHK) to produce the corresponding luecoanthocyanidins (Figure 5). Another enzyme, anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), in the last step reactions, catalyzes the conversion leucoanthocyanidins into cyanidin, pelarogondin, and delphnidin which are colored compounds. The synthesized anthocyanidins are then modified by a series of glycosylations and methylations that are catalyzed by UPD-glucose, flavonoid-3-glucosyl transferase (UFGT), and methyltransferase (MT), to form stable anthocyanins [15,17,18,19].

3. Production of Anthocyanins Using Plant Cell and Organ Cultures

For five to six decades, plant cell cultures have been studied to understand their part in in vitro production of anthocyanins for use in food, nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries, and cell or organ cultures have been initiated in more than 50 plant species [20]. Researchers experienced pigmentation in cell cultures regardless of the plant, species, source of explants, and types of cultures established since the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway is common to all flowering plants. Three significant plant species—carrot (Daucus carota), grape (Vitis vinifera), and strawberry (Fragaria ananassa)—have been the subject of in-depth research on in vitro cell cultures for the production of anthocyanins, among others. Several excellent review articles have been published and innumerable patents have been granted from time to time on anthocyanin production from in vitro cultures [20,21,22,23,24]. The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway is generally well-studied and established. In recent times, scientists have been working on genetic engineering and production-engineered plants and cell lines by cloning the regulatory genes and pathway genes involved in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway. They have also been using RNA interference to control the flavonoid flux in experimental plants like Nicotiana tabacum and Arabidopsis thaliana in order to produce anthocyanins for commercial use [12,24]. In the current review, we attempted to generalize the plant cell culture techniques and strategies used for a hyperaccumulation of anthocyanins by using well-studied systems like grape, carrot, and strawberry as well as model systems, like tobacco and arabidopsis, despite the difficulty of summarizing extensive research and comparing one cell culture system with others.

3.1. Strategies Applied for the Production of Anthocyanins in Cell and Organ Cultures

In many species, adventitious root, callus, cell, and hairy root cultures have been established (Table 1); strategies for biomass and anthocyanin production have been applied, including line/clone improvement or callus/cell/organ lines selection, culture medium selection, optimization of nutrient medium, phytohormones, and optimization of physical factors like light, temperature, hydrogen ion concentration (pH), precursors, and elicitors. In the section that follows, these strategies have been explained with appropriate examples.

Table 1.

Successful examples of anthocyanin production from in vitro cell and organ cultures.

3.1.1. Selection of Cell Lines

It has been shown that the capacity of plant cells to produce secondary metabolites varies significantly. The majority of cell culture research begins with the selection of a high-quality cell line for the accumulation of secondary metabolites [70]. To develop high anthocyanin-yielding cell lines, for instance, cell line selection for Euphorbia milli was done over numerous callus subcultures, choosing cells with increased anthocyanin content in each subculture [22]. Two cultivars of grapes, Vitis hybrid Baily Alicant A and V. vinifera cv. Gamy Freaux, have been routinely utilized to establish cell suspension cultures [71]. Excellent results have been obtained once again through the careful selection of cell clusters over repeated sub-cultures of higher-performing cells [71,72]. A further illustration of the significance of effective lines is provided by the hairy root cultures of black carrots. Barba-Espin et al. [41] used wild-type Rhizobium rhizogenes to produce 93 lines of hairy roots in black carrots. Three fast-growing hairy root lines were chosen, two of which were from root explants (NB-R and 43-R lines) and one from a hypocotyl explant (43-H line). They showed that, in comparison to the original carrot line, the chosen lines produced 25–30 times more biomass and nine distinct anthocyanins.

3.1.2. Optimization of Nutrient Medium

Establishing cell and organ cultures for the synthesis of plant secondary metabolites requires careful screening and the selection of appropriate media [70]. Different media formulations, with varying modifications, have been tested for establishing cell and organ cultures in various species for the production of anthocyanin (Table 1). These include Gamborg’s B5 medium [73], Linsmaier and Skoog or LS medium [74], Murashige and Skoog or MS medium [75], Shenk and Hildebrand or SH medium [76], and Woody plant medium or WPM [77]. In general, cell suspension cultures of Angelica archangelica, Aralia cordata, Cleome rosea, Daucus carota, Melostoma malabathricum, Oxalis linearis, Panax sikkimensis, and Prunus cersus could be established using MS media. It was discovered that LS medium was appropriate for cultivating cell cultures of Perilla frutesens and Fragaria annanasa; B5 medium was found to be appropriate for Vaccinium macrocorpon and Vitis vinifera; and WPM medium was found to be beneficial for Ajuga pyramidalis cell cultures (Table 1). The physiological state of the plant species and the kind of culture determine whether a certain medium is appropriate for a given species [78,79,80,81]. When Narayan et al. [39] tested B5, LS, MS, and SH media for their ability to grow Daucus carota cell cultures, they found that MS medium produced the most biomass and anthocyanin synthesis, while SH medium supported biomass and inhibited anthocyanin synthesis, and other media had lower levels of both biomass and anthocyanin. In hairy root cultures of carrots, Barba-Espin et al. [41] investigated the effects of 1/4, 1/2, and full-strength MS medium on biomass and anthocyanin accumulation. They found that, while full and 1/2 MS were beneficial for biomass accumulation, 1/2 MS was responsible for 4- to 6-fold higher anthocyanin production in various hairy root lines than full MS. They recommended a 1/2 MS medium for the accumulation of biomass and anthocyanin.

3.1.3. Influence of Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorous

Optimization of medium, especially with respect to carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous, has shown a significant impact on the growth of cultured cells and anthocyanin synthesis. The type and concentration of sugars in the medium have demonstrated a profound influence on the growth and synthesis of anthocyanins in cell cultures of varied species (Table 1). It was demonstrated with grape cell cultures that simple sugars, such as glucose, galactose, and sucrose, or metabolizable sugars support the growth of the cells and accumulation of biomass, whereas non-metabolizable sugars, such as mannitol, are responsible for osmotic stress, which triggers the accumulation of anthocyanins [82,83]. Rajendran et al. [84] subjected carrot callus cultures to high concentrations of both sucrose and mannitol and showed that such conditions resulted in an increase in anthocyanin production because of enhanced osmotic conditions. Such carbon effects have been also demonstrated in Ajuga pyramidalis [25], Cleome rosea [30], and Rosa hybrida [58]. In more recent studies, Dai et al. [85] displayed the effect of sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) on in vitro cultured grape berries (in vitro culturing of intact detached grape berries that were grown in greenhouse conditions); their work showed that glucose, fructose, and sucrose increased anthocyanin accumulation, with glucose and fructose being more effective than sucrose. Through molecular analysis, Dai et al. [85] illustrated that sugar induced enhanced anthocyanin accumulation in in vitro-grown grape berries, which resulted from altered expression of regulatory and structural genes, including CHS, CHI, F3′H, F3H, DFR, LAR, LDOX, and ANR.

Plant cell culture medium consists of both nitrate and ammonium forms of nitrogen, and the concentration of these two types of nitrogen has been shown to have profound influence on the growth of biomass and anthocyanin synthesis. It has been shown that the reduction of the ammonium form of nitrogen in the medium and enhancement of nitrate nitrogen favored cell growth and anthocyanin accumulation in many types of cell cultures (Table 1). The concentration of total nitrogen is 60 mM, and the ratio of NH4+ and NO3− is 1: 2 in MS medium; when the ratio of NH4+ to NO3- was varied from 1:1 to 1:32, keeping nitrogen concentration at 60 mM, there was increased production of anthocyanin (6.8% increment) in carrot cell suspension cultures [37]. However, they recorded optimal cell growth with the medium containing a 1:2 ratio of NH4+ to NO3−; therefore, this medium was responsible for a reduction in anthocyanin production of 3.5%. It was reported that cell growth and anthocyanin production was maximized when the ratio of NH4+ to NO3− was 1:1 at 60 mM in grape [86], 1:16 at 30 mM in Christ plant [87], 2:28 at 30 mM in strawberry [43], and 1:16 at 30 mM in spikenard [88] cell cultures. These results indicate that the reduction of ammonium nitrogen and increment in nitrate nitrogen favors anthocyanin synthesis in cell cultures of several plants. Another contrasting study by Hirasuna et al. [60] showed that the limitation of overall nitrogen concentration in the culture medium and the increment in sugar levels resulted in a ‘switch-like’ (rather than gradual) enhancement of anthocyanin production in grape cell cultures, which may be equivalent to the removal of an inhibitory effect. The possible explanation given for this short phenomenon is in line with the result which stated that elevated sugars are responsible for increment osmotic potential and concomitant reduction in cell division; this makes nutrient resources more available for secondary metabolism, leading to enhanced biosynthesis of anthocyanin. In contrast, the opposite situation is true for cell growth when higher concentrations of nitrogen levels and appropriate concentration of sugars. Recent studies by Saad et al. [40] have also shown a similar phenomenon in carrot cell suspension cultures. They demonstrated that an altered concentration of NH4NO3 and KNO3 (20:37.6 mM) of MS medium affected the transcription levels of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes, including PAL, 4CL, CHS, CHI, LDOX, and UFGT, which is accountable for the increased concentration of anthocyanin content.

Another element that has been demonstrated to have a significant impact on the synthesis of anthocyanins in Vitis vinifera [63] and Daucus carota [84] is the phosphorus level in the cell culture medium. In Vitis vinifera cell cultures, phosphate levels were reduced from 1.1 mM to 0.25 mM, and without phosphorus. This resulted in increased anthocyanin synthesis by 32% and 46%, respectively [63]. During the culture period, they observed a simultaneous rise in dihydroflavonol reductase activity. Yin et al. [69] investigated the impact of phosphate deficiency on the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in Vitis vinifera cv. Baily Alicante in a different study. Increases in the expression of transcription factor-encoding gene VvMybA1 and the flavonoid 3-O-glucosyl transferase (UFGT) gene are implicated in the pathway leading to anthocyanin production.

3.1.4. Influence of Plant Growth Regulators

Plant cell cultures are normally supplemented with varied growth regulators, including auxins such as 2,4-D, IAA, IBA, and NAA, and cytokinins, such as BAP/BA, KN, 2-iP. In several cases, a combination of several auxins with cytokinins has been tested and used efficiently to increase the cell biomass and anthocyanin production. Less frequently, researchers have tested the impact of gibberellic acid (GA3) and abscisic acid (ABA) in cell cultures of some species. Overall comparative analysis of the impact of growth regulators reveals that the effect of auxins and cytokinins varies from species to species. Among the varied auxins tested, 2,4-D showed promotive effects at lower concentrations, triggering cell growth; however, at elevated concentrations it was found to be inhibitory for anthocyanin production (Table 1). In carrot (Daucus carota cv. Kurodagosun) cell suspension cultures, Ozeki and Komamine [33] initially demonstrated that anthocyanin formation was induced by transferring the cells from 2,4-D containing medium to 2,4-D lacking medium. In subsequent studies, Ozeki et al. [89] showed that the carrot cell suspension involved in activities of phenyl ammonia-lyase (PAL), chalcone synthase (CHS), and chalcone-flavanone isomerase (CHFI) activities decreased when they were transferred to the cells from 2,4-D containing medium to 2,4-D lacking medium. Liu et al. [28] demonstrated the function of various auxin concentrations (0, 0.2, 0.4, 2.2, 9, 18, and 27 µM) in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana, including IAA, NAA, and 2,4-D. Among transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana, these auxins variably regulated the expression of genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis, including four pathway genes (PAL1, CHS, DFR, and ANS) and six transcription factors (TTG1, EGL3, MYBL2, TT8, GL3, and PAP1).

Narayan et al. [39] studied the influence of 2,4-D, IAA, and NAA at different levels and recorded the decreased anthocyanin productivity with the increase in 2,4-D levels, and among the three auxins tested, they showed maximum biomass as well as anthocyanin production only when IAA was present in the medium. In addition, Narayan et al. [39] tested the influence of BAP, KN, and 2-iP (0.1–0.4 mg/L) in combination with IAA (2 mg/L), and again, a low level of KN (0.2 mg/L) showed the highest productivity of anthocyanin. Cytokinin’s effect on the gene expression involved in the process of anthocyanin biosynthesis, including PAL, CHS, CHI, and DFR genes, has been demonstrated by Deikman and Hammer [90]. The addition of KN encouraged the growth of biomass, whereas the substitution of BAP for KN reduced the formation of anthocyanins. In addition to auxins and cytokinins, Gagne et al. [65] have demonstrated the impact of the growth regulator ABA on the formation of anthocyanins in grape cell cultures. Research revealed that the expression of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, such as PAL, C4H, CHI1, and CHI2, could be induced when ABA was supplemented in the medium. The findings presented above imply that choosing the right combination and concentration of plant growth regulators is essential for producing anthocyanins and cell biomass in plant cell cultures.

3.1.5. Influence of Light, Temperature, and Medium pH

Varied factors, including light, temperature, and medium pH, are reported to be useful components that should be optimized before using the cultures to scale up the process, and these factors influence both biomass and secondary metabolite accumulation in plant cell and organ cultures [70,78]. Fluorescent light, when applied to callus or cell suspension cultures of carrot [91], grape [24], strawberry [92], perilla [53], senduduk [50], and cranberry [59], demonstrated a stimulatory effect on biosynthesis and accumulation of anthocyanins (Table 1). The positive effect of light in relation to PAL activity has been shown by Takeda et al. [91]. The influence of UV-A, UB-B, and UV-C lights has been demonstrated in grape berries; their effect is correlated with the stimulation of expression of the structural genes that encode the enzymes in the shikimate pathway [93].

Studies on Perilla furtescens [53], and Melastoma malbarthricum [50] have examined the effects of temperature regimes during in vitro cell cultures. Generally, relatively higher temperature levels (25 to 30 °C) favored cell growth and biomass accumulation, while relatively lower temperatures (20 °C) facilitated the synthesis of anthocyanins. Zhang et al. [94] used a two-stage culture strategy, maintaining the cultures at 30 °C for three days before moving them to 20 °C. This allowed them to achieve an optimal anthocyanin content of 270 g/L, which was higher than what they would have obtained with a constant temperature treatment. Research conducted by Yamane et al. [95] on the anthocyanin accumulation in berries of the Vitis hybrid (V. labrusca × V. vinifera) revealed that 20 °C is preferred above 30 °C for a higher anthocyanin accumulation. Although the exact mechanism underlying the temperature effect is yet unknown, Azuma et al. [96] demonstrated the differential expression of MYB-related transcription factors that are temperature-regulated using qRT-PCR study. Additional research is required in this area of study.

The pH or hydrogen ion concentration of the culture media is another crucial element that promotes cell growth and metabolite accumulation. Extreme pH values should be avoided; generally, cells growing in the medium may absorb nutrients efficiently and participate in growth, development, and metabolism at a pH of 5.8 [70]. Numerous groups have conducted research on the effects of medium pH on cell proliferation and anthocyanin production. In Vitis hybrid Baily Alicant A, Suzuki et al. [97] examined cell growth, biomass accumulation, and anthocyanin synthesis in media with varying pH levels, ranging from 4.5 to 8.5. They found that the medium with a pH of 4.5 produced better cell growth and anthocyanin synthesis. Iercan and Nedelea [98] observed a comparable phenomenon in callus cultures of Vitis vinifera cultivars. The callus cultures of Feteasca neagra with the highest anthocyanin content (13.5 mg/g FW) were found on the medium with pH = 4.5, whereas the medium with pH = 7.5 revealed 3.3 mg/g FW of anthocyanin. Hagendoorn et al. [99] showed that, in a number of plant species, such as Morinda citrifolia, Petunia hybrida, and Linum flavum, cytoplasmic acidification promoted the formation of secondary metabolites. They demonstrated a rise in PAL activity in response to the culture medium’s cytoplasmic acidification. Numerous studies have shown that higher medium sugar concentrations and nitrate-to-ammonium ratios promote the accumulation of anthocyanins in cell cultures of different species. These characteristics are also responsible for the medium’s pH reduction and the acidification of cultured cells (Table 1).

3.1.6. Elicitation

Elicitors are molecules of biotic and abiotic origin or physical stimuli, such as pulsed electric field or UV irradiation, that can trigger the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in plant cell and organ cultures [100]. Elicitors such as methyl jasmonate, jasmonic acid, and salicylic acid have been used efficiently in plant in-vitro cultures to activate the biosynthesis of anthocyanins (Table 1). The extracts of bacterial and fungal origin; insect saliva/varied components of insect saliva; complex polysaccharides, such as chitosan, pectin, alginate, and cyclodextrin; high concentration varied salts, such as CaCl2, MnSO4, ZnSO4, CoCl2, FeSO4, VoSO4, CuSO4, NH4NO3, and KnO3; ethephon (ethylene producer); UV irradiation; and pulsed electric field stimulus have been tested as elicitors in cell and organ cultures to enhance the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway (Table 1).

Treatment of cell suspension cultures of Vitis vinifera with methyl jasmonate (MeJA) has triggered a 2.9 to 4.1-fold increment in anthocyanin content [64,101]. Similarly, MeJA has been shown to enhance the anthocyanin accumulation in callus cultures of Malus sieversii [49]. However, the efficiency of the elicitation process depends on the plant material, culture conditions, contact time, and elicitor concentration. In another study, Qu et al. [64] tested the combined effect of precursor feeding (phenylalanine) treatment with MeJA treatment in grape cell cultures, and they achieved a 4.6-fold increment in anthocyanin accumulation with the addition of 5 mg/L phenylalanine and 50 mg/L MeJA. Sun et al. [49] showed that expression of anthocyanin regulatory (MdMYB3, MdMYBB9, and MdMYB10) and structural (MdCHS, MdDFR, MdF3H, and MdUFGT) genes increased in Malus sieversii in response to MeJA elicitation. In addition, Wang et al. [102] demonstrated the upregulation of MdMYB24L gene in response to MeJA treatment in apple cell cultures, which positively regulates the transcription of MdDFR and MdUGFGT genes. The molecular mechanism of JA elicitation is also in line with MeJA action, and Shan et al. [103] deciphered the role of F-box protein CO11 in regulating the transcription factors PAP1, PAP2, and GL3, which were responsible for the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes DFR, LDOX, and UF3GR in Arabidopsis thaliana.

4. Application of Metabolic Engineering

The biosynthetic pathway involved in the production of anthocyanins has been thoroughly investigated, and the genes involved in the conversion of the precursors to final products have been elucidated [104,105]. The anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway genes have been cloned into Nicotiana tabacum and Arabidopsis thaliana. Strategies used during metabolic engineering to improve anthocyanin production include: (1) cloning regulatory genes that control the pathway genes, (2) cloning pathway genes involved in various steps of anthocyanin biosynthesis, (3) utilizing RNA interference (RNAi) for gene silencing, and (4) utilizing the clustered regulatory interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas system for gene knockout [12,23,104,105,106,107,108].

Transcription factors (TF) of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, such as MYB (myeloblastosis family), bHLH (basic helix-loop-helix family), and WD40/WDR (beta-transducin repeat family), have been suggested to regulate anthocyanin production in plants. For example, MdMYB1 in Malus domestica, R2R3-MYBs like PAP1, PAP2, MYB113, and MYB114 in Arabidopsis thaliana, and VvMYBA1 and VvMYBA2 in Vitis vinifera all regulate the production of anthocyanin [104]. Liu et al. [109] proposed that the transcription of many structural genes is regulated by the MYB, bHLH, and WD40 (MBW) complex, which binds to and activates their promoters. Here, we are highlighting the research carried out by Appelhagen et al. [12], who have cloned the two MYB transcription factors from Antirrhinum majus namely MYB Rosea1 (AmRos1) and bHLH Delila (AmDel) to Nicotiana tabacum cv. Sumsun. They raised calli and cell suspension cultures generated from AmDel/AmRos1 plants and reported the accumulation of 30 mg/g DW of cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside (C3R) with such cultures. They maintained the engineered tobacco AmDel/AmRos1 cultures for more than 10 years without substantial reduction in anthocyanin production, demonstrating its stability without aging or silencing of the transgenes.

In another set of experiments, Appelhagen et al. [12] expressed a pathway gene encoding flavonoid 3′,5′-hydroxylase from Petunia × hybrida (PhF3′5′H) or a gene encoding an anthocyanin 3-O-rutinoside-4″hydoxycinnmoyl transferase from Solanum lycopersicum (Sl3AT) in AmDel/AmRos1 tobacco lines. They demonstrated that the cell lines that were expressing AmDel/AmRos1 and PhF3′5′H were purple due to the production of delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside (D3R) in addition to C3R. Appelhagen et al. [12] displayed that the engineered tobacco lines AmDel/AmRos1-PhF3′5′H and AmDel/AmRos1-Sl3AT were quite stable and produced 4-fold higher (20 mg/g DW) anthocyanins (C3R) when compared to wild grape cell cultures (5 mg/g DW). Through high-performance liquid chromatography analysis, Appelhagen et al. [12] deciphered that the anthocyanin extract of the AmDel/AmRos1 line contained almost exclusively C3R, with minor amounts of cyanidin 3-O-glucoside (C3G), pelargonidin 3-O-rutinoside (Pel3R), and peonidin 3-O-rutinoside (Phe3R). They recorded similar profiles with AmDel/AmRos1-PhF3′5′H except for the additional production of delphinidin 3-O-rutinoside (D3R). Meanwhile, they reported aromatically acylated compounds with coumaroyl- or feruloyl-moieties, with cyanidin 3-O-(coumaroyl) rutinoside (C3couR) and cyanidin 3-O-(feruloyl) rutinoside (C3ferR) with AmDel/AmRos1- Sl3AT line. Similar to these findings, Shi and Xie [110] generated plants and cell lines in Arabidopsis thaliana by cloning the pap1-D gene. Mono et al. [111] demonstrated the overexpression of the IBMYB1 gene in Ipomea batatus calli.

Nakatsuka et al. [112] have used an RNAi-mediated gene silencing technique to generate red-flower transgenic tobacco by suppressing two endogenous genes (FLS, F3′H) along with overexpression of a foreign DFR gene in gerbera, which shits the flux toward pelargonidin synthesis. Khusnutdinov et al. [105] discussed varied examples of the phenotypic effect of CRISPR/Cas in editing the pap1, DFR, F3H, and F3′H genes of several distinct plant species.

5. Scale-Up Process

Numerous species, including Aralia cordata, Daucus carota, Nicotiana tabacum, Perilla frutescens, Vaccinium pahale, and Vitis vinifera (Table 2), have been the subject of studies aimed at scale-up cell or callus suspension cultures, and a number of bioprocess parameters have been optimized [113,114,115,116]. Kobayashi et al. [113] used Aralia cordata cell suspension cultures to evaluate a 500-L pilot-scale bioreactor culture for the synthesis of anthocyanins. After 16 days of cultivation, and with the provision of a carbon dioxide supply in the culture vessel, they obtained a fresh weight cell yield of 69.2 kg, an anthocyanin yield of 545 g, and an anthocyanin content of 17.2% in the dried cells. Although these experiments have been conducted in bioreactors ranging in size from small to large, the technology of bioreactors has not been applied further for the synthesis of anthocyanins. The selection of species with a higher anthocyanin content and the optimization of all bioprocess parameters, such as nutrient medium, physical characteristics, and other parameters that drive biomass growth and pigment accumulation, are prerequisites for successful bioreactor applications for the production of pigments. Highly promising recent investigations were conducted by Appelhagen et al. [12], who employed a transformed tobacco line (AmDel*/AmRos1) that was cultivated in 2 L stirred tank commercial fermenters using LS media containing 1 mg/L 2,4-D and 100 mg/L kanamycin for 14 days at 23 °C. They were able to achieve 180 mg per bioreactor run and 90 mg/L of cyanidin 3-O-rotinoside (C3G) with such refined procedures.

Table 2.

Successful examples of anthocyanin production from scale-up cultures.

6. Extraction of Anthocyanins

Anthocyanins from plant sources have been extracted using a variety of conventional and sophisticated techniques. Anthocyanins are typically extracted using solvent extraction, which generally involves the use of polar solvents, such as methanol, ethanol, acetone, water, and alcohol [117]. Maximum recovery of anthocyanins from plant tissues has generally been found to be possible with polar solvents at concentrations of 60–80%. Choosing appropriate extraction solvents is essential because anthocyanins are extremely reactive compounds [118]. The extraction of anthocyanins from plant material has typically involved the use of acidified solvents; modest acetic acid and hydrochloric acid concentrations have been shown to increase the extraction yield. However, using acids with higher concentrations should be avoided as this could cause the glycosidic linkages to partially hydrolyze [118]. Typically, 1–2% of an acidic agent, such as citric acid, formic acid, or phosphoric acid, is utilized together with organic solvents, such as methanol, ethanol, and acetonitrile. It was recommended that GRAS solvent be used to prevent the health concerns associated with different organic solvents [117]. As a result, several researchers have adhered to the two-phase aqueous extraction method [119,120]. As an alternative, scientists have experimented with high hydrostatic pressure [121], pulsed electric field extraction [122], microwave-assisted extraction [123], pressurized liquid extraction [124], and supercritical CO2 extraction [125]. All of these methods have been successfully used to extract anthocyanins from various plant materials. In conclusion, based on the source of material, appropriate processes that are effective, safer, and can adopt reduced solvent usage and higher extraction yield could be utilized.

7. Conclusions

A growing number of food and cosmetic companies are using anthocyanins as natural colorants since they offer a number of advantageous dietary and therapeutic benefits. In order to produce anthocyanins for use as natural colorants in the food and cosmetic industries, researchers are focusing on plant cell and organ cultures as a viable alternative due to the limited availability and variability of anthocyanins’ quality and quantity from natural resources, like fruits and vegetables. Despite five or six decades of study on plant cell and organ cultures, commercial production of anthocyanin has not proven successful. However, anthocyanins may now be obtained in greater amounts because of advancements in metabolic engineering and the cloning of regulator and pathway genes in model plants like Arabidopsis and tobacco. Notwithstanding the abundance of studies conducted in the field of plant cell and organ cultures, appropriate plant system selection, metabolic engineering implementation, and RNA interference, CRISPR/Cas technologies have the potential to generate valuable transgenic lines that exhibit elevated concentrations of particular anthocyanin compounds. It is necessary to conduct more studies in the following areas: cell line selection, culture condition optimization, elicitation, and bioprocess technology optimization utilizing bioreactor cultures. The development of extraction technologies and increasing the bioavailability of anthocyanins by encapsulation and other techniques are two more areas that require coordinated efforts. The application of plant cell and organ cultures to meet the rapidly expanding market demand for natural colorants in the food and cosmetic industries may be made possible by advancements in the aforementioned technologies.

Author Contributions

H.N.M.: conceptualization; H.N.M., K.S.J. and K.Y.P.: investigation, data curation, and formalization; S.-Y.P.: resources and validation; H.N.M., K.S.J., K.Y.P. and S.-Y.P.: writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

H.N.M. is thankful to the National Research Foundation of Korea for the award of the Brain Pool Fellowship (2022H1D3A2A02056665).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Natural food pigments and colorants. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 7, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdson, G.T.; Tang, P.; Giusti, M.M. Natural colorants: Food colorants from natural sources. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Dash, U.; Mahanand, S.S.; Nayak, P.K.; Kesavan, R.K. Black rice: A comprehensive review on its bioactive compounds, potential health benefits and food applications. Food Chem. Adv. 2023, 3, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, L.; Berhow, M.; Mejia, E.F.D. Black bean anthocyanin-rich extracts as food colorants: Physiochemical stability and antidiabetic potential. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 628–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoo, H.E.; Azlan, A.; Tang, S.T.; Lim, S.M. Anthocyanidins and anthocyanins: Colored pigments as food, pharmaceutical ingredients, and the potential health benefits. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 61, 1361779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konczak, I.; Zhang, W. Anthocyanins—More than nature’s colours. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2004, 2004, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaneda-Ovando, A.; Paceco-Hernandez, M.D.L.; Paez-Hernandez, M.E.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Galan-Vidal, C.A. Chemical studies of anthocyanins: A review. Food Chem. 2009, 113, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, P.M.; Harborne, J.B. Plant phenolics in Plant Biochemistry. Academic Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1997; pp. 326–341. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Giusti, M.M. Anthocyanins: Natural colorants with health-promoting properties. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernadez-Lopez, J.A.; Fernadez-Lledo, V.; Angosto, J.M. New insights into red plant pigments: More than just natural colorants. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 24669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khayri, J.M.; Asghar, W.; Akhtar, A.; Ayub, H.; Aslam, I.; Khalid, N.; Al-Mssllem, M.Q.; Alessa, F.M.; Ghazzawy, H.S.; Attimard, M. Anthocyanin delivery systems: A critical review of recent research findings. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelhagen, I.; Wulff-Vester, A.K.; Wendell, M.; Hvoslef-Eide, A.K.; Russell, J.; Oertel, A.; Martens, S.; Mock, H.P.; Martin, C.; Matros, A. Colour bio-factories: Towards scale-up production of anthocyanins in plant cell cultures. Metab. Eng. 2018, 48, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, X.; Lyu, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, W.; Ye, L.; Yang, R. Biotechnological advances for improving natural pigment production: A state-of-the-art review. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, S.; Tanaka, Y. Genetic modification in floriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2007, 26, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinn, K.; Davies, K. “Flavonoids” In Plant Pigments and Their Manipulation; Davies, K.M., Ed.; CRC Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; Volume 14, pp. 92–136. [Google Scholar]

- Seitz, C.; Ameres, S.; Forkmann, G. Identification of the molecular basis for the functional difference between flavonoid 3’hydxylase and flavonoid 3’,5’-hydroxylase. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 34293434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Tsuda, S.; Kusumi, T. Metabolic engineering to modify flower color. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998, 39, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Katsumoto, Y.; Brugliera, F.; Mason, J. Genetic engineering in floriculture. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2005, 80, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tao, J. Recent advances on the development and regulation of flower color in ornamental plants. Font Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deroles, S. Anthocyanin biosynthesis in plant cell cultures: A potential source of natural colourants. In Anthocyanins, Biosynthesis, Functions, and Applications; Winefield, C., Davies, K., Gould, K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 108–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sietz, H.U.; Hinderer, W. Anthocyanins. In Cell Culture and Somatic Cell Genetics in Plants; Constabel, F., Vasil, I.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; pp. 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Furusaki, S. Production of anthocyanins by plant cell cultures. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 1999, 4, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belwal, T.; Singh, G.; Jeandet, P.; Pandey, A.; Giri, L.; Ramola, S.; Bhatt, I.D.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Georgiev, M.I.; Clement, C.; et al. Anthocyanins, multi-functional natural products of industrial relevance: Recent biotechnological advances. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananga, A.; Georgiev, V.; Ochieng, J.; Phills, B.; Tsolova, V. Production of anthocyanins in grape cell cultures: A potential source of raw materials for pharmaceutical, food and cosmetic industries. In The Mediterranean Genetic Code—Grapevine and Olive; Poljuha, D., Sladonja, B., Eds.; InTech: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, D.L.; Juthangkoon, S.; Lewen, K.; Berber-Jimenez, M.D.; Smith, M.A.L. Characterization of anthocyanin from Ajuga pyramidalis Metallica Crispa cell cultures. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1170–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siatka, T. Effects of growth regulators on production of anthocyanins in callus cultures of Angelica archangelica. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 2019, 1934578X19857344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.Z.; Xie, D.Y. Features of anthocyanin biosynthesis in pap1-D and wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana plants grown in different light intensity and culture media conditions. Planta 2010, 231, 1385–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Shi, M.Z.; Xie, D.Y. Regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana red pep1-D cells metabolically programmed by auxins. Planta 2014, 239, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, K.; Iida, K.; Sawamura, K.; Hajiro, K.; Asada, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Furuya, T. Anthocyanin production in cultured cells of Aralia cordata Thunb. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1994, 36, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes-Gurgel, C.; Cordeiro, L.D.S.; de Castro, T.C.; Callado, C.H.; Albarello, N.; Mansur, E. Establishment of anthocyanin-producing cell suspension cultures of Cleome rosea Vahl ex DC. (Capparaceae). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011, 106, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnersley, A.M.; Dougall, D.K. Increase in anthocyanin yield from wild-carrot cell cultures by a selection system based on cell-aggregate size. Planta 1980, 149, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dougall, D.K.; Johnson, J.M.; Whitten, G.H. A clonal analysis of anthocyanin accumulation by cell cultures of wild carrot. Planta 1980, 149, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozeki, Y.; Komamine, A.; Noguchi, H.; Sankawa, U. Changes in activities of enzymes involved in flavonoid metabolism during the initiation and suppression of anthocyanin synthesis in carrot suspension cultures regulated by 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Physiol. Plant. 1987, 69, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, R.P.; Keshavarz, E.; Gerson, D.F. Optimization of anthocyanin yield in a mutated carrot cell line (Daucus carota) and its implications in large scale production. J. Fermenta. Bioeng. 1989, 68, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, L.; Suvarnalatha, G.; Ravishankar, G.A.; Venkataraman, L.V. Enhancement of anthocyanin production in callus cultures of Daucus carota L. under the influence of fungal elicitors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1994, 42, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvarnalatha, G.; Rajendran, L.; Ravishankar, G.A.; Venkataraman, L.V. Elicitation of anthocyanin production in cell cultures of carrot (Daucus carota L.) by using elicitors abiotic elicitors. Biotechnol. Lett. 1994, 16, 1275–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, M.S.; Venkataraman, L.V. Effect of sugar and nitrogen on the production of anthocyanin in cultured carrot (Daucus carota) cells. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 84–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudha, G.; Raviashankar, G.A. Elicitation of anthocyanin production in callus cultures of Daucus carota and the involvement of methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2003, 25, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, M.S.; Thimmaraju, R.; Bhagyalakshmi, N. Interplay of growth regulators during solid-state and liquid-state batch cultivation of anthocyanin producing cell line of Daucus carota. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, K.R.; Parvatam, G.; Shetty, N.P. Medium composition potentially regulates the anthocyanin production from suspension culture of Daucus carota. 3 Biotech. 2018, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Espin, G.; Chen, S.T.; Agnolet, S.; Hegelund, J.N.; Stanstrup, J.; Christensen, J.H.; Muller, R.; Lutken, H. Ethephon-induced changes in antioxidants and phenolic compounds in anthocyanin-producing black carrot hairy root cultures. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 7030–7045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, K.R.; Kumar, G.; Mudliar, S.N.; Giridhar, P.; Shetty, N.P. Salt stress-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis genes and MATE transporter involved in anthocyanin accumulation in Daucus carota cell cultures. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24502–24514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Sakurai, M. Production of anthocyanin from strawberry cell suspension cultures: Effects of sugar and nitrogen. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, M.; Seki, M.; Furusaki, S. Enhanced anthocyanin methylation by growth limitation of strawberry suspension culture. Enz. Microb. Technol. 1998, 22, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Jin, M.F.; Yu, X.J.; Yuan, Q. Enhanced anthocyanin production by repeated-batch culture of strawberry cells with medium shift. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 55, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edahiro, J.; Nakamura, M.; Seki, M.; Furusaki, S. Enhanced accumulation of anthocyanin in cultured strawberry cells by repetitive feeding of L-phenylalanine into the medium. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2005, 99, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stickland, R.G.; Sunderland, N. Production of anthocyanins, flavonoids, and chlorogenic acid by cultured callus tissue of Haplopappus gracilis. Ann. Bot. 1972, 36, 443–457. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42752057 (accessed on 20 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.H.; Wang, Y.T.; Zhang, R.; Wu, S.J.; An, M.M.; Li, M.; Wang, C.Z.; Chen, X.L.; Zhang, Y.M.; Chen, X.S. Effect of auxin, cytokinin and nitrogen on anthocyanin biosynthesis in callus cultures of red-fleshed apple (Malus sieversii f. niedzwetzkyana). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015, 120, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Gong, X.; Wang, N.; Ma, L.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fend, S. Effects of methyl jasmonate and abscisic acid on anthocyanin biosynthesis in callus cultures of red-fleshed apple (Malus sieversii f. niedzwetzkyana). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2017, 130, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.K.; Koay, S.S.; Boey, P.L.; Bhatt, A. Effects of abiotic stress on biomass and anthocyanin production in cell cultures of Melastoma malabathricum. Biol. Res. 2010, 43, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, H.J.; Van Staden, J. The in vitro production of an anthocyanin from callus cultures of Oxalis linearis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1995, 40, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Mathur, A.K.; Gangwar, A.; Yadav, S.; Verma, P.; Sagwan, R.S. Anthocyanin production in a callus of Panax sikkimensis Ban. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 2010, 46, 13–21. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40663763 (accessed on 20 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.J.; Yoshida, T. Effects of temperature on cell growth and anthocyanin production in suspension cultures of Perilla frutescens. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1993, 76, 530–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.J.; Yoshida, T. High-density cultivation of Perilla frutescens cell suspensions for anthocyanin production: Effects of sucrose concentration and inoculum size. Enz. Microb. Technol. 1995, 17, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.W.; Xia, Z.H.; Chu, J.H.; Tan, R.X. Simultaneous production of anthocyanin and triterpenoids in suspension cultures of Perilla frutescens. Enz. Microb. Technol. 2004, 34, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blando, F.; Scardino, A.P.; de Bellis, L.; Nicoletti, I.; Giovinazzo, G. Characterization of in vitro anthocyanin-producing sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) callus cultures. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 937–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betsui, F.; Tanaka-Nishikawa, N.; Shimomura, K. Anthocyanin production in adventitious root cultures of Raphanus sativus L. cv. Peking Koushin. Plant. Biotechnol. 2004, 21, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, M.; Prasad, K.V.; Singh, S.K.; Hada, B.S.; Kumar, S. Influence of salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate elicitation on anthocyanin production in callus cultures of Rosa hybrida L. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2013, 113, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavi, D.L.; Smith, M.A.L.; Berber-Jimenez, M.D. Expression of anthocyanin in callus cultures of cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait). J. Food Sci. 1995, 60, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirasuna, T.J.; Shuler, M.L.; Lackney, V.K.; Spanswick, R.M. Enhanced anthocyanin production in grape cell cultures. Plant Sci. 1991, 78, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, C.B.; Cormier, F. Effects of low nitrate and high sugar concentrations on anthocyanin content and composition of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cell suspension. Plant Cell Rep. 1991, 9, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, F.; Do, C.B.; Nicolas, Y. Anthocyanin production in selected cell lines of grape (Vitis vinifera L.). In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 1994, 30, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedaldechamp, F.; Uhel, C.; Macheix, J.J. Enhancement of anthocyanin synthesis and dihydroflavonol reductase (DFR) activity in response to phosphate deprivation in grape cell suspension. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 1357–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, X. A combination of elicitation and precursor feeding leads to increased anthocyanin synthesis in cell suspension cultures of Vitis vinifera. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011, 107, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagne, S.; Cluzet, S.; Merillon, J.M.; Geny, L. ABA initiates anthocyanin production in grape cell cultures. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2011, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Knorr, D.; Smetanska, I. Enhanced anthocyanins and resveratrol production in Vitis vinifera cell suspension culture by indanoyl-isoleucine, N-linolenoyl-L-glutamine and insect saliva. Enz. Microb. Technol. 2012, 50, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Kastell, A.; Mewis, I.; Knorr, D.; Smetanska, I. Polysaccharide elicitors enhance anthocyanin and phenolic acid accumulation in cell suspension cultures of Vitis vinifera. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012, 108, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saw, N.M.M.T.; Riedel, H.; Cai, Z.; Kutuk, O.; Smetanska, I. Stimulation of anthocyanin synthesis in grape (Vitis vinifera) cell cultures by pulsed electric fields and ethephon. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2012, 108, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Borges, G.; Sakuta, M.; Crozier, A.; Ashihara, H. Effect of phosphate deficiency on the content and biosynthesis of anthocyanins and the expression of related genes in suspension-cultured grape (Vitis sp.) cells. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, H.N.; Lee, E.J.; Paek, K.Y. Production of secondary metabolites from cell and organ cultures: Strategies and approaches for biomass improvement and metabolite accumulation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014, 118, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Mu, L.; Yan, G.L.; Liang, N.N.; Pan, Q.A.H.; Wang, J.; Reeves, M.J.; Duan, C.Q. Biosynthesis of anthocyanins and their regulation in colored grapes. Molecules 2010, 15, 9057–9091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Zhang, W.; Yu, X.; Jin, M. Instability of anthocyanin accumulation in Vitis vinifera var. Gamay Freaux suspension cultures. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2005, 10, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamborg, O.L.; Miller, R.A.; Ojima, K. Nutrient requirements of suspension cultures of soybean root cells. Exp. Cell Res. 1968, 50, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsmaier, E.M.; Skoog, F. Organic growth factor requirements of tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1965, 18, 100–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue culture. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, R.U.; Hildebrandt, A.C. Medium and techniques for induction and growth of monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plant cultures. Can. J. Bot. 1972, 50, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, G.; McCown, B. Commercially feasible micropropagation of mountain laurel, Kalmia latifolia, by use of shoot-tip culture. Proc. Intl. Plant Prop. Soc. 1980, 30, 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, H.N.; Dandin, V.S.; Paek, K.Y. Tools for biotechnological production of useful phytochemicals from adventitious root cultures. Phytochem. Rev. 2016, 15, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Paek, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Anthraquinone production from cell and organ cultures of Rubia species: An overview. Metabolites 2022, 13, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Paek, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Production of anthraquinones from cell and organ cultures of Mordinda species. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 2061–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Paek, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Suspension culture of somatic embryos for the production of high-value secondary metabolites. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2023, 29, 1153–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cormier, F.; Crevier, H.A.; Do, C.B. Effects of sucrose concentration on the accumulation of anthocyanin in grape (Vitis vinifera) cell suspension. Can. J. Bot. 1989, 68, 1822–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, C.B.; Cormier, F. Accumulation of anthocyanins enhanced by a high osmotic potential in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cell suspensions. Plant Cell Rep. 1990, 9, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, L.; Ravishankar, G.A.; Venkataraman, L.V.; Prathiba, K.R. Anthocyanin production in callus cultures of Daucus carota as influenced by nutrient stress and osmoticum. Biotechnol. Lett. 1992, 14, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.W.; Meddar, M.; Renaud, C.; Merlin, I.; Hilbert, G.; Delrot, S.; Gomes, E. Long-term in vitro culture of grape berries and its application to assess the effects of sugar supply on anthocyanin accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 4665–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakawa, T.; Kato, S.; Ishida, K.; Kodama, T.; Minoda, Y. Production of anthocyanin by Vitis cells in suspension cultures. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1983, 47, 2185–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Kinoshita, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Yamada, Y. Anthocyanin production in suspension cultures of high producing cells of Euphobia millii. Agic. Biol. Chem. 1989, 53, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, K.; Iida, K.; Sawamura, K.; Hajiro, K.; Asada, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Furuya, T. Effect of nutrients on anthocyanin production in cultured cells of Aralia cordata. Phytochemistry 1993, 33, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozeki, Y.; Komamine, A. Effects of inoculum density, zeatin and sucrose on anthocyanin in a carrot suspension culture. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1985, 5, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deikman, J.; Hammer, P.E. Induction of anthocyanin accumulation by cytokinins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1995, 108, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeda, J. Light-induced synthesis of anthocyanin in carrot cells in suspension. II. Effects of light and 2,4-D on induction and reduction of enzyme activities related to anthocyanin synthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 1990, 41, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Nakayama, M.; Shigeta, J. Culturing conditions affecting the production of anthocyanin in suspended cell cultures of strawberry. Plant Sci. 1996, 113, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Z.; Li, X.X.; Chu, Y.N.; Zhang, M.X.; Wen, Y.Q.; Daun, C.Q.; Pan, Q.H. Three types of ultraviolet irradiation differentially promote expression of shikimate pathway genes and production of anthocyanins in grape berries. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2012, 57, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Seki, M.; Furusaki, S. Effect of temperature and its shift on growth and anthocyanin production in suspension cultures of strawberry cells. Plant Sci. 1997, 127, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Jeong, S.T.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Koshita, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Effects of temperature on anthocyanin biosynthesis in grape berry skins. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 2006, 57, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, A.; Yakushiji, H.; Koshita, Y.; Kobayashi, S. Flavonoid biosynthesis-related genes in grape skin are differentially regulated by temperature and light conditions. Planta 2012, 236, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M. Enhancement of anthocyanin accumulation by high osmotic stress and low pH in grape cells (Vitis hybrids). J. Plant Physiol. 1995, 147, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iercan, C.; Nedelea, G. Experimental results concerning the effect of culture medium pH on the synthesized anthocyanin amount in the callus cultures of Vitis vinifera L. J. Hortic. For. Biotechnol. 2012, 16, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hagendoorn, M.J.M.; Wagner, A.M.; Segers, G.; van der Plas, L.H.W.; Oostdam, A.; van Walraven, H.S. Cytoplasmic acidification and secondary metabolite production in different plant cell suspensions. Plant Physiol. 1994, 106, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Davis, L.C.; Verpoorte, R. Elicitor signal transduction leading to production of plant secondary metabolites. Biotechnol. Adv. 2005, 23, 283–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belhadj, A.; Telef, N.; Saigne, C.; Cluzet, S.; Barrieu, F.; Hamdi, S.; Merillon, J.M. Effect of methyl jasmonate in combination with carbohydrates on gene expression of PR proteins, stilbene and anthocyanin accumulation in grapevine cell cultures. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2008, 46, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Jiang, H.; Mao, Z.; Wang, N.; Jiang, S.; Xu, H.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor MdMYB24-like is involved in methyl-jasmonate anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 139, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, W.; Wang, Z.; Xie, D. Molecular mechanism for jasmonate-induction of anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3849–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yu, W.; Xu, J.; Lu, X.; Liu, Y. Anthocyanin biosynthesis induced by MYB transcription factors in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khusnutdinov, E.; Sukhareva, A.; Panfilova, M.; Mikhaylova, E. Anthocyanin biosynthesis genes as model gene for genome editing in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Ohmiya, A. Seeing is believing: Engineering anthocyanin and carotenoid biosynthesis pathways. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2008, 19, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, H. Anthocyanin in food plants: Current status, genetic modification and future prospects. Molecules 2023, 28, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Butelli, E.; Martin, C. Engineering anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 19, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, K.; Qi, Y.; Lv, G.; Ren, X.; Liu, Z.; Ma, F. Transcriptional regulation of anthocyanin synthesis by MYB-bHLH-WDR complexes in kiwifruit (Actinidia chinensis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 3677–3691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.Z.; Xie, D.Y. Engineering of red cells of Arabidopsis thaliana and comparative genome-wide expression analysis of red cells versus wild-type cells. Planta 2011, 233, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mano, H.; Ogasawara, F.; Sato, K.; Higo, H.; Minobe, Y. Isolation of a regulatory gene of anthocyanin biosynthesis in tuberous roots of purple-fleshed sweet potato. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 1252–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuka, T.; Abe, Y.; Kakizaki, Y.; Yamamura, S.; Nishihara, M. Production of red-flowered plants by genetic engineering of multiple flavonoid biosynthetic genes. Plant Cell Rep. 2007, 26, 1951–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Akita, M.; Sakamoto, K.; Liu, H.; Shigeoka, T.; Koyano, T.; Kawamura, M.; Furuya, T. Large-scale production of anthocyanin by Aralia cordata cell suspension cultures. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1993, 40, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.E.; Pepin, M.F.; Smith, M.A.L. Anthocyanin production from Vaccinium pahalae: Limitations of the physical microenvironment. J. Biotechnol. 2002, 93, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, H.; Thibault, J.; Cormier, F.; Do, C.B. Vitis vinifera culture in a non-conventional bioreactor: The reciprocating plate bioreactor. Bioprocess Eng. 1999, 21, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, H.; Hiraoka, K.; Nagamori, E.; Omote, M.; Kato, Y.; Hiroka, S.; Kobayashi, T. Enhanced anthocyanin production from grape callus in an air-lift type bioreactor using viscous additive-supplemented medium. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2002, 94, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, S.; Shah, M.A.; Siddiqui, M.W.; Dar, B.N.; Mir, S.A.; Ali, A. Recent trends in extraction techniques of anthocyanins from plant materials. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 3508–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongkowijoyo, P.; Luna-Vital, D.A.; de Mejia, E.A. Extraction techniques and analysis of anthocyanins from food sources by mass spectrometry: An update. Food Chem. 2018, 250, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Mu, T.; Sun, H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J. Optimization of aqueous two-phase extraction of anthocyanins from purple sweet potatoes by response surface methodology. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3034–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monrad, J.K.; Suarez, M.; Motilva, M.J.; King, J.W.; Srinvas, K.; Howard, L.R. Extraction of anthocyanins and flavan-3-ols from red grape pomace continuously by coupling hot water extraction with a modified expeller. Food Res. Int. 2014, 65, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ning, C.; Chang, X.; Meng, X. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, and antioxidant capacities of anthocyanin extracts of wild Lonicera caerulea berry. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 36, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertolas, E.; Cregenzan, O.; Luengo, E.; Alvarez, I.; Raso, J. Pulsed-electric-field-assisted extraction of anthocyanins from purple-fleshed potato. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 1330–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, Y.; Lin, Z.; Liu, H. Extraction characteristics and optimal parameters of anthocyanin from blue berry powder under microwave-assisted extraction conditions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 104, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Mendoza, M.D.P.; Espinosa-Pardo, F.A.; Baseggio, A.M.; Barbero, G.F.; Marostica, M., Jr.; Rostagno, M.; Martinez, J. Extraction of phenolic compounds and anthocyanins from jucara (Euterpe edulis Mart.) residues using pressurized liquids and supercritical fluids. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2017, 119, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babova, O.; Occhipinti, A.; Capuzzo, A.; Maffei, M.E. Extraction of bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus) antioxidants using supercritical/subcritical CO2 and ethanol as co-solvent. J. Supercit. Fluids 2016, 107, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).