OsRCI-1-Mediated GLVs Enhance Rice Resistance to Brown Planthoppers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Overexpressing OsRCI-1 Enhances Production of Mechanical Damage-Induced GLVs in Rice

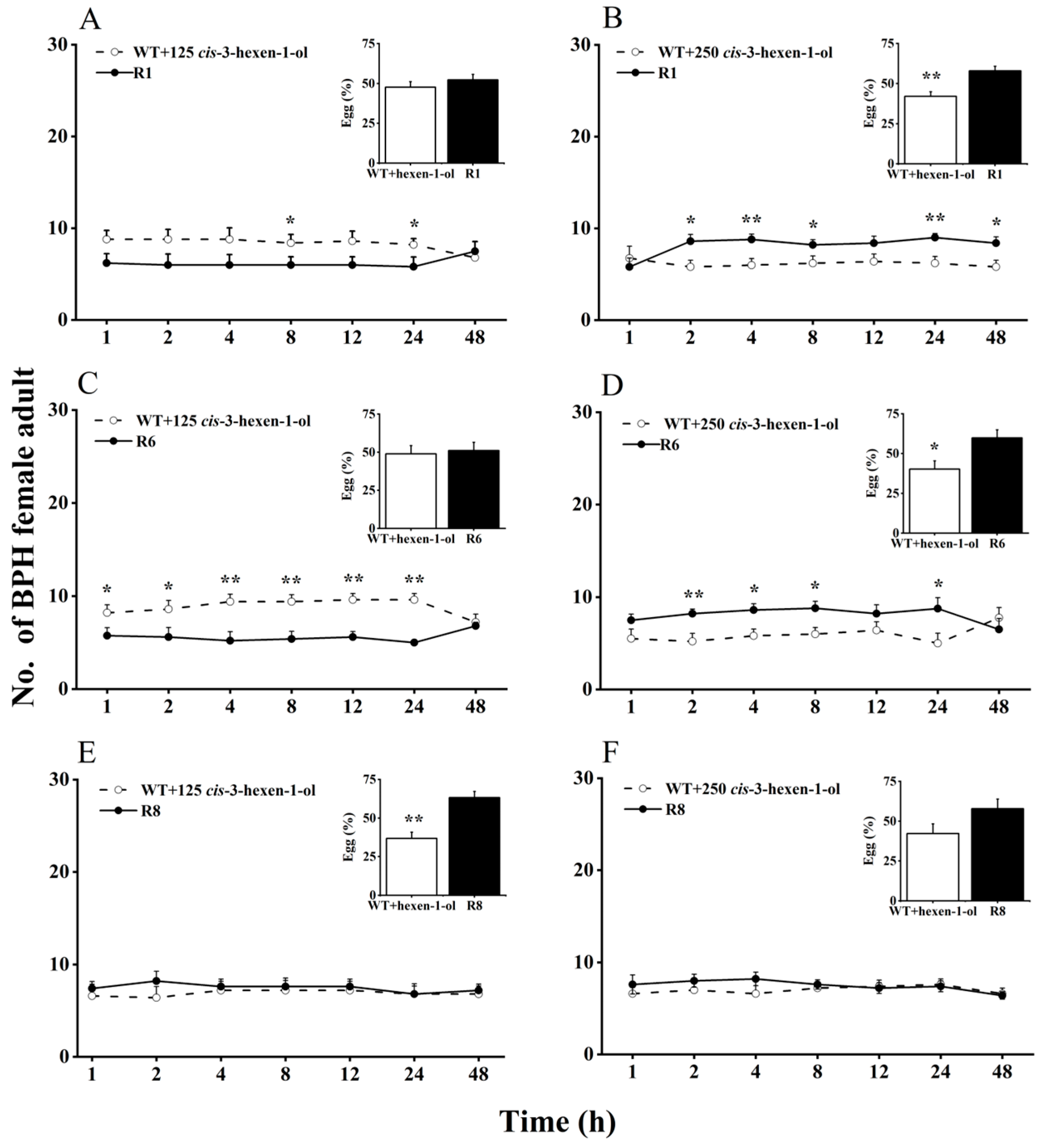

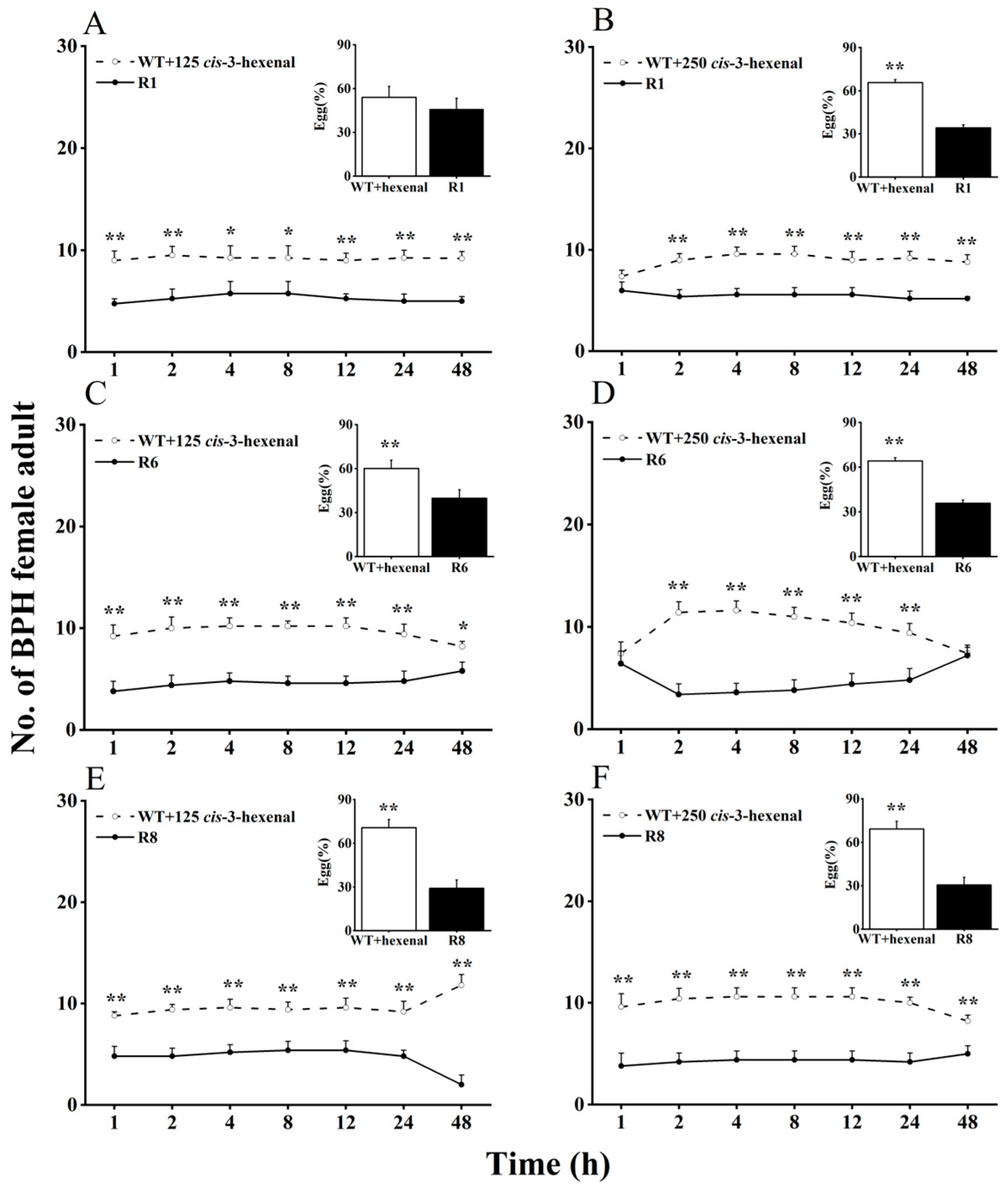

2.2. Effects of cis-3-hexen-1-ol and cis-3-hexenal on Feeding and Oviposition Preferences of BPH

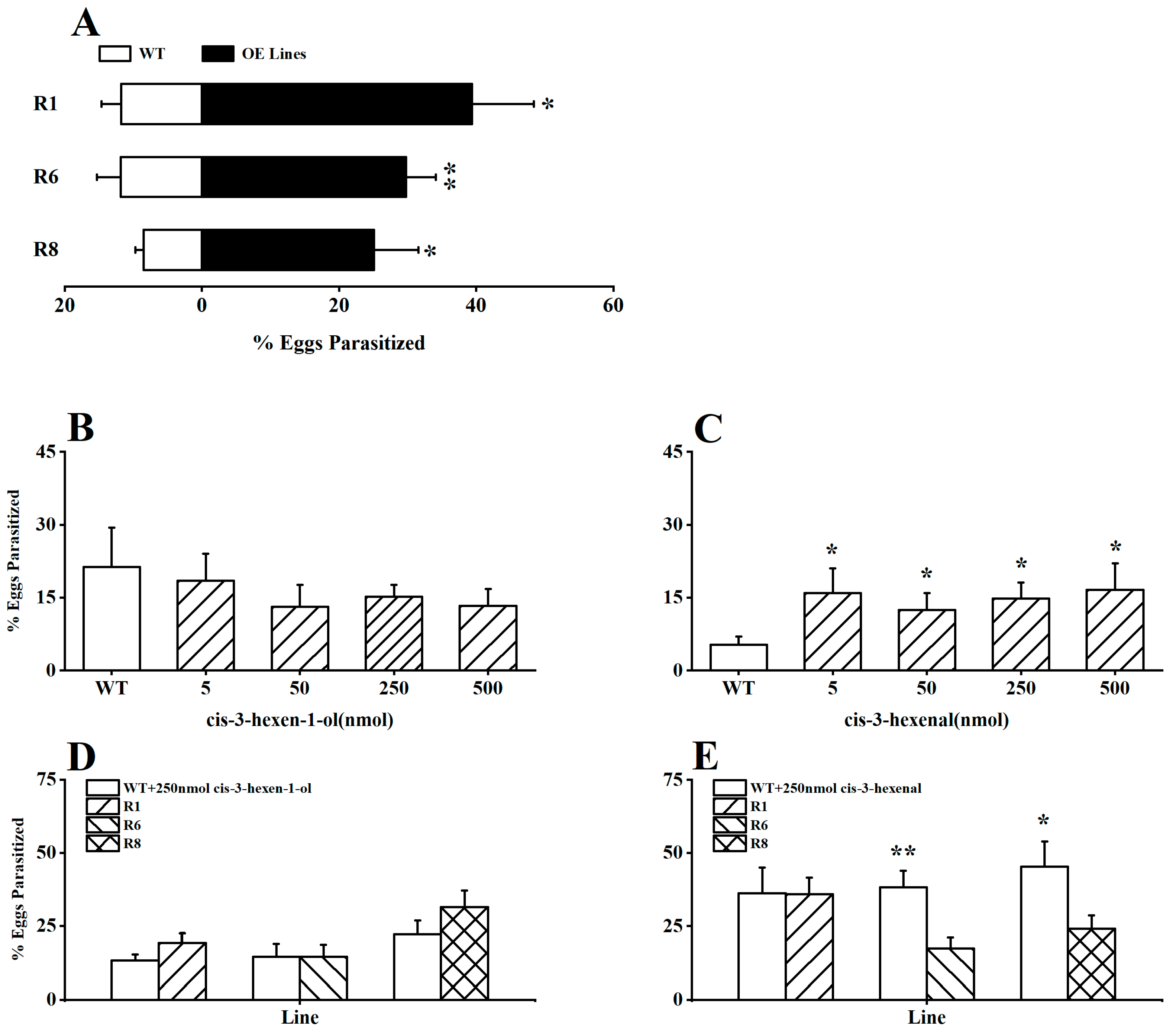

2.3. GLVs Modify Rice’s Attractiveness to Parasitoids after BPH Infestation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Rice Materials

4.2. Insect Materials

4.3. Reagents and Instruments

4.4. GLV Analysis

4.5. BPH Bioassays

4.6. Field Experiment

4.7. Wasp Bioassays in Controlled Climate Chamber

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feussner, I.; Wasternack, C. The lipoxygenase pathway. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002, 53, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, M.; Chiappetta, A.; Bruno, L.; Bitonti, M.B. In Posidonia oceanica cadmium induces changes in DNA methylation and chromatin patterning. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selli, S.; Kelebek, H.; Ayseli, M.T.; Tokbas, H. Characterization of the most aroma-active compounds in cherry tomato by application of the aroma extract dilution analysis. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameye, M.; Allmann, S.; Verwaeren, J.; Smagghe, G.; Haesaert, G.; Schuurink, R.C.; Audenaert, K. Green leaf volatile production by plants: A meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.; Zhou, G.; Yang, L. The chloroplast-localized phospholipases D α4 and α5 regulate herbivore-induced direct and indirect defense in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 1987–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Sun, X. A tea hydroperoxide lyase gene, CsiHPL1, regulates tomato defense response against Prodenia litura (Fabricius) and Alternaria alternata f. sp. Lycopersici by modulating green leaf volatiles (GLVs) release and jasmonic acid (JA) gene expression. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 32, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Yao, Q.; Chen, G.; Tong, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Su, Q.; Zhang, Y. Direct and indirect plant defenses induced by (Z)-3-hexenol in tomato against whitefly attack. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 1243–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Qi, J.; Zhu, X.; Mao, B.; Zeng, L.; Wang, B.; Li, Q.; Zhou, G.; Xu, X.; Lou, Y.; et al. The rice hydroperoxide lyase OsHPL3 functions in defense responses by modulating the oxylipin pathway. Plant J. 2012, 71, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhou, G.; Xin, Z.; Ji, R.; Lou, Y. (Z)-3-hexenal, one of the green leaf volatiles, increases susceptibility of rice to the white-backed planthopper Sogatella furcifera. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 33, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.L.; Shirano, Y.; Ohta, H.; Hibino, T.; Tanaka, K.; Shibata, D. A novel lipoxygenase from rice: Primary structure and specific expression upon incompatible infection with rice blast fungus. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 3755–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, H.; Shirano, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Morita, Y.; Shibata, D. cDNA cloning of rice lipoxygenase L-2 and characterization using an active enzyme expressed from the cDNA in Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992, 206, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Miura, K.; Shigemune, A.; Sasahara, H.; Ohta, H.; Uehara, Y.; Ishikawa, T.; Hamada, S.; Shirasawa, K. Marker-assisted breeding of a LOX-3-null rice line with improved storability and resistance to preharvest sprouting. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2015, 128, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Qi, J.; Ren, N.; Cheng, J.; Erb, M.; Mao, B.; Lou, Y. Silencing OsHI-LOX makes rice more susceptible to chewing herbivores, but enhances resistance to a phloem feeder. Plant J. 2009, 60, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, K.; Iida, T.; Takano, A.; Yokoyama, M.; Fujimura, T. A new 9-lipoxygenase cDNA from developing rice seeds. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 1168–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaffrath, U.; Zabbai, F.; Dudler, R. Characterization of RCI-1, a chloroplastic rice lipoxygenase whose synthesis is induced by chemical plant resistance activators. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 5935–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Shen, W.; Liu, L.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Su, N.; Wan, J. A novel lipoxygenase gene from developing rice seeds confers dual position specificity and responds to wounding and insect attack. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2008, 66, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabbai, F.; Jarosch, B.; Schaffrath, U. Over-expression of chloroplastic lipoxygenase RCI1 causes PR1 transcript accumulation in transiently transformed rice. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2004, 64, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Cao, M.; Wang, J.; Yao, Z.; Zhou, S.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, D.; Lou, Y. The lipoxygenase gene OsRCI-1 is involved in the biosynthesis of herbivore-induced JAs and regulates plant defense and growth in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 2827–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K. Green leaf volatiles: Hydroperoxide lyase pathway of oxylipin metabolism. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006, 9, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Cao, M.; Wang, X.; Miao, J.; Shen, L.; Deng, J.; Wu, H.; Xu, Z.; Lou, Y.; Zhou, G. Rice lipoxygenase gene OsRCI-1 mediated pathway positively regulates resistance to rice striped stem borer. J. Environ. Entomol. 2014, 36, 507–515. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Y.; Tan, H.; Jian, G.; Zhou, X.; Huo, L.; Jia, Y.; Zeng, L.; Yang, Z. Herbivore-induced (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol is an airborne signal that promotes direct and indirect defenses in tea (Camellia sinensis) under light. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelberth, J.; Alborn, H.T.; Schmelz, E.A.; Tumlinson, J.H. Airborne signals prime plants against insect herbivore attack. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1781–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelberth, J.; Contreras, C.F.; Dalvi, C.; Li, T.; Engelberth, M.; Heil, M. Early transcriptome analyses of Z-3-hexenol-treated Zea mays revealed distinct transcriptional networks and anti-herbivore defense potential of green leaf volatiles. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farag, M.A.; Fokar, M.; Abd, H.; Zhang, H.; Allen, R.D.; Pare, P.W. (Z)-3-Hexenol induces defense genes and downstream metabolites in maize. Planta 2005, 220, 900–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamy, F.; Dugravot, S.; Cortesero, A.M.; Chaminade, V.; Faloya, V.; Poinsot, D. One more step toward a push-pull strategy combining both a trap crop and plant volatile organic compounds against the cabbage root fly Delia radicum. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 29868–29879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, S.; Nandi, O.I.; Kang, L. Plants attract parasitic wasps to defend themselves against insect pests by releasing hexenol. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mao, K.; Li, C.; Zhai, H.; Wang, Y.; Lou, Y.; Xue, W.; Zhou, G. OsRCI-1-Mediated GLVs Enhance Rice Resistance to Brown Planthoppers. Plants 2024, 13, 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13111494

Mao K, Li C, Zhai H, Wang Y, Lou Y, Xue W, Zhou G. OsRCI-1-Mediated GLVs Enhance Rice Resistance to Brown Planthoppers. Plants. 2024; 13(11):1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13111494

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Kaiming, Chengzhe Li, Huacai Zhai, Yuying Wang, Yonggen Lou, Wenhua Xue, and Guoxin Zhou. 2024. "OsRCI-1-Mediated GLVs Enhance Rice Resistance to Brown Planthoppers" Plants 13, no. 11: 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13111494

APA StyleMao, K., Li, C., Zhai, H., Wang, Y., Lou, Y., Xue, W., & Zhou, G. (2024). OsRCI-1-Mediated GLVs Enhance Rice Resistance to Brown Planthoppers. Plants, 13(11), 1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13111494