A Revised Taxonomy of the Bassia scoparia Complex (Camphorosmoideae, Amaranthaceae s.l.) with an Updated Distribution of B. indica in the Mediterranean Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

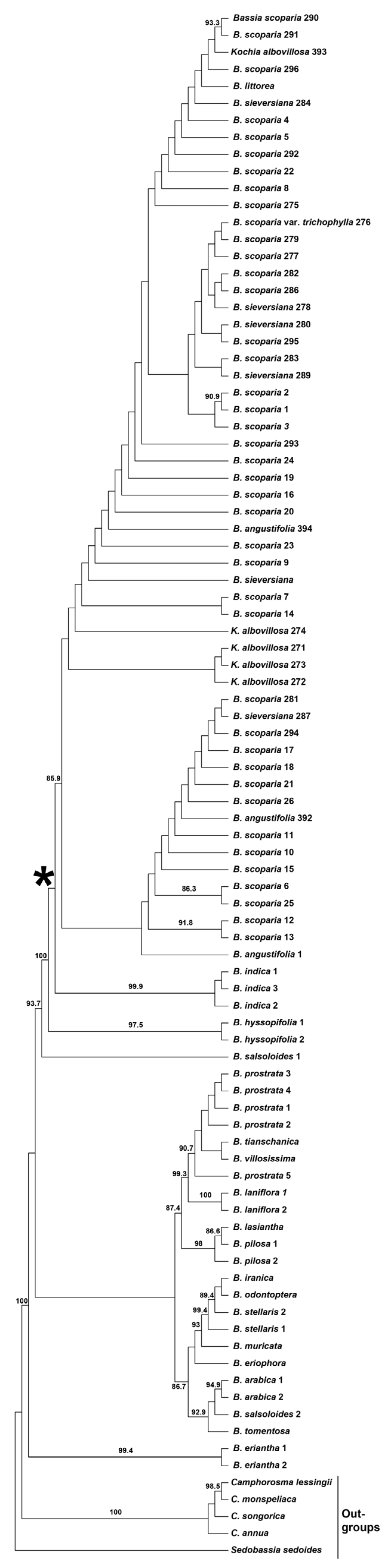

2.1. Phylogenetic Study of Bassia scoparia

- (1)

- Bassia angustifolia (three accessions), B. littorea (one accession), B. scoparia s. str. (incl. B. scoparia var. trichophila) (41 accessions), B. sieversiana (six accessions), and Kochia albovillosa + K. scoparia subsp. hirsutissima (five accessions) are all nested in the moderately supported (aLTR = 80.8) Bassia scoparia clade (Figure 1) that strictly corresponds to the B. scoparia taxonomic alliance. Neither of these segregate species (including narrowly defined B. scoparia) appears monophyletic.

- (2)

- The single accession of B. littorea is defined as a non-supported sister of a clade containing three accessions of B. scoparia (290, 291, and 296) and one accession of K. albovillosa (393).

- (3)

- The latter taxon is monophyletic with the exclusion of accession 393. However, the clade with four samples of K. albovillosa (271–274) received no aLRT support.

- (4)

- The monophyletic B. indica is confirmed as a moderately supported sister of broadly defined B. scoparia (aLTR = 100 and 80.8) (Figure 1).

- (5)

- The monophyletic B. hyssopifolia is a strongly supported sister of the clade (B. scoparia s.l. plus B. indica) (aLTR = 100 and 98) (Figure 1).

- (6)

- The short lengths of all branches of the obtained ML phylogenetic tree within the B. scoparia clade (Figure S1) imply a high degree of genetic similarity among the analyzed individuals from all the species listed above.

2.2. Revised Taxonomy and Nomenclature of Bassia scoparia

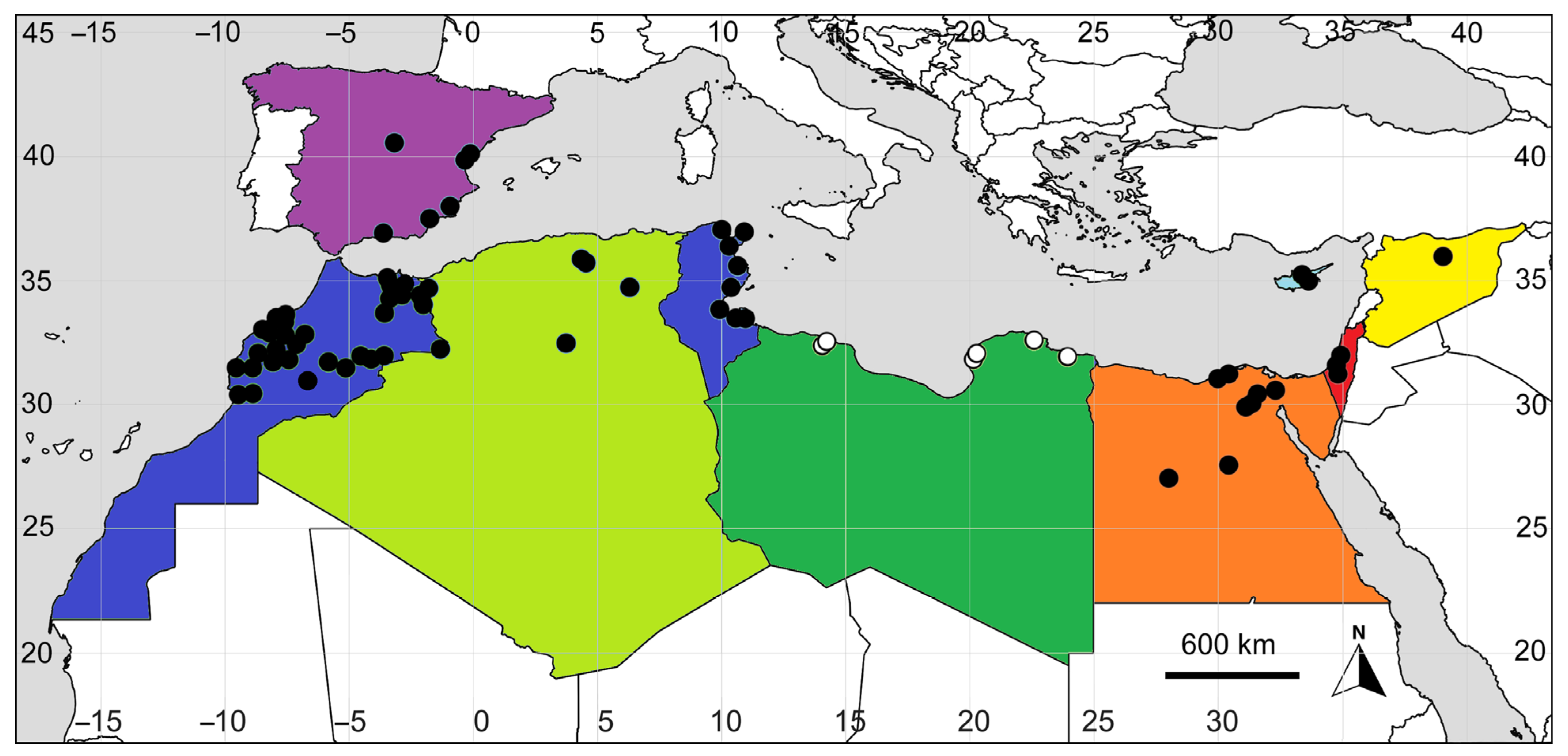

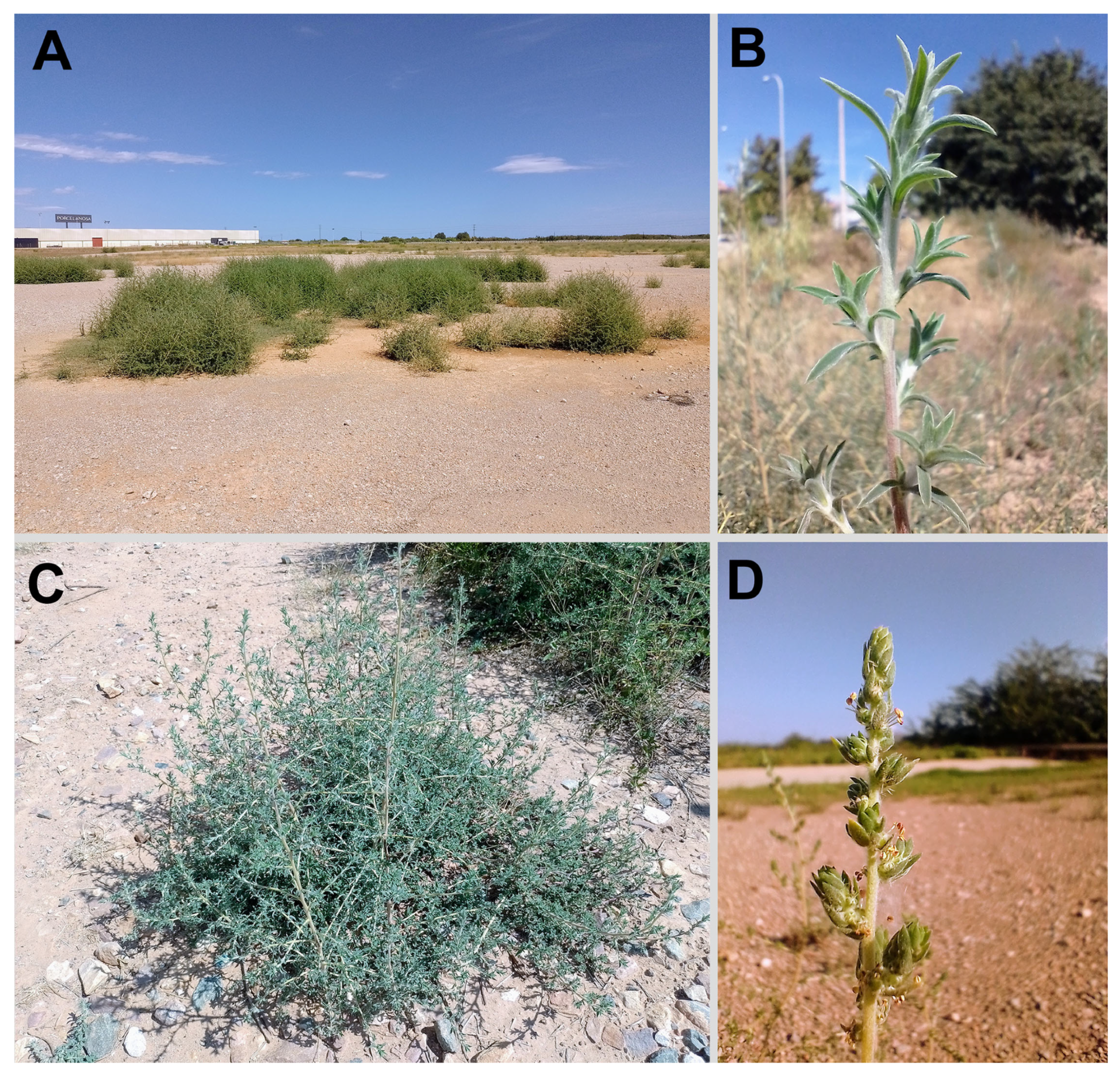

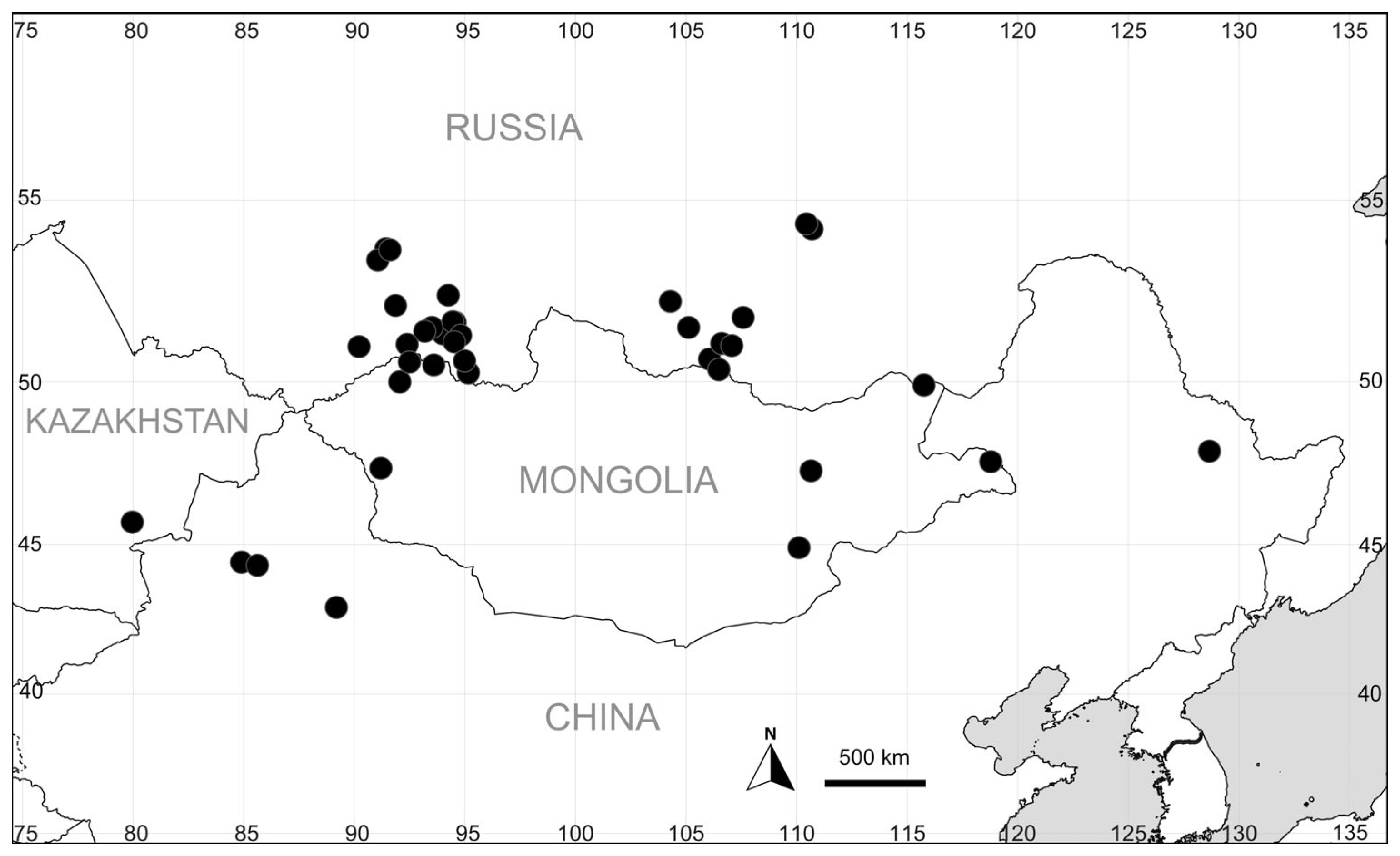

2.3. Updated Diagnostic Characters and Distribution of Bassia indica in the Mediterranean

3. Discussion

3.1. Taxonomic Circumscription of Bassia scoparia

3.2. Valid Publication of Bassia scoparia

3.3. Type Variant of Bassia scoparia

3.4. More Pubescent Variant of Bassia scoparia

3.5. Halophytic Variant of Bassia scoparia

3.6. Ornamental Variant of Bassia scoparia

3.7. Hirsute Variant of Bassia scoparia

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Molecular Phylogenetic Analysis and Related Procedures

4.2. Morphological Study: Taxonomy and Distributions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Sukhorukov, A.P. The Carpology of the Chenopodiaceae with Reference to the Phylogeny, Systematics and Diagnostics of Its Representatives; Grif & Co.: Tula, Russia, 2014; pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Aellen, P. Ergebnisse einer Botanisch-Zoologischen Sammelreise durch Iran. Botanische Ergebnisse IV: Chenopodiaceae: Kochia. Mitt. Basler Bot. Ges. 1954, 2, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, K.M. Phenotypic Variations of Kochia Scoparia. Master’s Thesis, Utah State Agricultural College: Logan, UT, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Iljin, M.M. Chenopodiaceae. In Flora of USSR; Shishkin, B.K., Ed.; Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR: Moscow, Russia; Leningrad, Russia, 1936; Volume 6, pp. 2–354. [Google Scholar]

- Peschkova, G.A. Stepnaya Flora Baikalskoy Sibiri [The Steppe Flora of the Baikal Siberia]; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1972; pp. 1–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov, M.S. Chenopodiaceae. In Sosudistye Rasteniya Sovetskogo Dal’nego Vostoka; Kharkevich, S.S., Ed.; Nauka: Leningrad, Russia, 1988; Volume 3, pp. 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lomonosova, M.N. Chenopodiaceae. In Flora Sibiri; Krasnoborov, I.M., Malyshev, L.I., Eds.; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1992; Volume 5, pp. 135–183. [Google Scholar]

- Mavrodiev, E.V.; Sukhorukov, A.P. Systematische Beiträge zur Flora von Kasachstan. Ann. Naturhistorischen Mus. Wien 2003, 104, 699–703. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, T.; Honda, M.; Satake, Y.; Kitagawa, M. Report of the First Scientific Expedition to Manchoukuo Under the Leadership of Shigeyasu Tokunago, June–October 1933. Section IV; Waseda University: Shinjuku, Japan, 1936; Volume 4, pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kadereit, G.; Freitag, H. Molecular Phylogeny of Camphorosmeae (Camphorosmoideae, Chenopodiaceae): Implications for Biogeography, Evolution of C4-photosynthesis and Taxonomy. Taxon 2011, 60, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck-Mannagetta, G.; Lerchenau. Icones Florae Germanicae et Helvetiacae Simul Terrarum Adjacentium Ergo Mediae Europae; Zezschwitz: Leipzig & Gera, Germany, 1909; Volume 24, pp. 1–222. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.J. A Revision of the Camphorosmioideae (Chenopodiaceae). Feddes Repert. 1978, 89, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.A. New Names and Combinations, Principally in the Rocky Mountain Flora—VII. Phytologia 1989, 67, 425–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Kushunina, M.A. Morphology, Nomenclature and Distribution of Bassia monticola (Chenopodiaceae-Amaranthaceae), a poorly known species from Western Asia. Novit. Syst. Plant Vasc. 2020, 51, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, H.; Kadereit, G. C3 and C4 Leaf Anatomy Types in Camphorosmeae (Camphorosmoideae, Chenopodiaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 2014, 300, 665–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, W.H.; Baechle, M.D.; Williamson, G. Synopsis of Kochia (Chenopodiaceae) in North America. Sida 1978, 7, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Turki, Z.; El-Shayeb, F.; Shehata, F. Taxonomic Studies in the Camphorosmeae (Chenopodiaceae) in Egypt. 1. Subtribe Kochiinae (Bassia, Kochia and Chenolea). Fl. Medit. 2006, 16, 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen, L.F.; Beckie, H.J.; Warwick, S.I.; van Acker, R.C. The Biology of Canadian Weeds. 138. Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrad. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2009, 89, 141–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschkova, G.A. Chenopodiaceae. In Flora Tsentral’noy Sibiri; Malyshev, L.I., Peschkova, G.A., Eds.; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1979; Volume 1, pp. 282–305. [Google Scholar]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisimova, M.; Gascuel, O. Approximate Likelihood-Ratio Test for Branches: A Fast, Accurate, and Powerful Alternative. Syst. Biol. 2006, 55, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, M. Lineamenta Florae Manshuricae or, an Enumeration of All the Indigenous Vascular Plants Hitherto Known from Manchurian Empire Together with Their Synonymy, Distribution and Utility; Institute of Scientific Research, Manchoukuo: Hsinking, China, 1939; pp. 1–487. [Google Scholar]

- Aellen, P. Über einige Kochia-Formen aus Argentinien. Darwiniana 1941, 5, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- De Bolòs, O.; Vigo, J. Notes sobre Taxonomia i Nomenclatura de Plantes, I. Butlletí La Inst. Catalana D’història Nat. 1974, 38, 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Aellen, P.; Edmondson, J.R.; Townsend, C.C. Chenopodiaceae Vent. In Flora of Iraq; Ghazanfar, S.A., Edmondson, J.R., Eds.; Bell and Bain Ltd.: Glasgow, UK, 2016; Volume 5, pp. 164–256, part 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wight, R. Icones Plantarum Indiae Orientalis: Or Figures of Indian Plants; J.B. Pharoah: Madras, India, 1852; Volume 5, pp. 1–35, + Tab.1622–1920. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Liu, P.-L.; Kushunina, M. Taxonomic Revision of Chenopodiaceae in Himalaya and Tibet. PhytoKeys 2019, 116, 1–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedge, I. Kochia. In Flora Iranica; Rechinger, K.H., Ed.; Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt: Graz, Austria, 1997; Volume 172, pp. 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, D.; Heyn, C.C. Conspectus Florae Orientalis; The Israel Academy of Sciences & Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1994; Volume 9, pp. 1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.G.; Cope, T.A. Flora of the Arabian Peninsula and Socotra; University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1996; Volume 1, pp. 1–586. [Google Scholar]

- Germishuizen, G.; Meyer, N.L. (Eds.) Plants of Southern Africa: An Annotated Checklist; National Botanical Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2003; pp. 1–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Kushunina, M.; El Mokni, R.; Sáez Goñalons, L.; El Aouni, M.H.; Daniel, T.F. Chorological and Taxonomic Notes on African Plants, 3. Bot. Lett. 2018, 165, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odorico, D.; Nicosia, E.; Datizua, C.; Langa, C.; Raiva, R.; Souane, J.; Nhalungo, S.; Banze, A.; Caetano, B.; Nhauando, V.; et al. An Updated Checklist of Mozambique’s Vascular Plants. PhytoKeys 2022, 189, 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ghazali, G.E.B. An Annotated Checklist to the Chenopod Flora of Sudan. Int. J. Sci. 2020, 9, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uotila, P. Chenopodiaceae (pro parte majore). In Euro+Med Plantbase—The Information Resource for Euro-Mediterranean Plant Diversity. Available online: http://www.europlusmed.org (accessed on 20 May 2024).

- Jafri, S.M.H.; Rateeb, F.B. Chenopodiaceae. In Flora of Libya; Jafri, S.M.H., El-Gadi, A., Eds.; Al-Faateh University: Tripoli, Libya, 1978; Volume 58, pp. 1–109. [Google Scholar]

- Boulos, L. Flora of Egypt. Checklist; Al Hadara Publishing: Cairo, Egypt, 1995; pp. 1–283. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary, M. Flora Palaestina; The Israel Academy of Sciences & Humanities: Jerusalem, Israel, 1966; Volume 1, pp. 1–346. [Google Scholar]

- Hand, R. Supplementary Notes to the Flora of Cyprus III. Willdenowia 2003, 33, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taifour, H.; El-Oqlah, A. The Plants of Jordan. An Annotated Checklist; Kew Publishing: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–171. [Google Scholar]

- Draz, O. Some Desert Plant and Their Uses in Animal Feeding; Institut du Desert d’Egypte: Cairo, Egypt, 1954; Volume 2, pp. 1–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bornmüller, J. Zwei Neue Arten aus Süd-Palästina: Centaurea calcitrapella und Bassia joppensis Bornm. et Dinsmore. Repert. Specierum Nov. Regni Veg. 1921, 17, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Eig, A.A. Revision of the Chenopodiaceae of Palestine and Neighbouring Countries. Palest. J. Bot. 1945, 3, 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Amer, W.M. The Worst Invasive Species to Egypt. In Invasive Alien Species: Observations and Issues from Around the World; Pullaiah, T., Ielmini, M.R., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 112–138. [Google Scholar]

- Viney, D.E. An Illustrated Flora of North Cyprus; Koelz Scientific Books: Vaduz, Liechtenstein, 1994; Volume 1, pp. 1–697. [Google Scholar]

- Della, A.; Iatrou, G. New Plant Records from Cyprus. Kew Bull. 1995, 50, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrtek, J.; Slavík, B. Contribution to the Flora of Cyprus. 4. Fl. Medit. 2001, 10, 235–259. [Google Scholar]

- Hand, R. Various Noteworthy Records of Flowering Plants in Cyprus (1996–2019) and Some Status Clarifications. Cypricola 2020, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Biodiversity of Libya Electronic Resource 2022. Available online: https://biodiversity.ly (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Ali Nafea, E.M. Floristic Composition of the Plant Cover at Surt Region of Libya. Catrina 2015, 12, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Mahklouf, M.H.; Shakman, E.A. Invasive Alien Species in Libya. In Invasive Alien Species: Observations and Issues from Around the World; Pullaiah, T., Ielmini, M.R., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Le Floc’h, É.; Boulos, L.; Véla, E. Catalogue Synonymique Commenté de La Flore de Tunisie, 2nd ed.; Banque Nationale de Gènes de la Tunisie: Tunis, Tunisia, 2010; pp. 1–500. [Google Scholar]

- Benmeddour, T.; Fenni, M. Biologie et Écologie de Ganida (Kochia scoparia (L.) Schrad): Plante Envahissante Du Périmètre de l’Ouatya, Biskra. Aridoculture 2008, 1, 341–356. [Google Scholar]

- Quezel, P.; Santa, S. Nouvelle Flore d’Algerie et Des Regions Desertiques Meridionales; Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique: Paris, France, 1962; Volume 1, pp. 1–565. [Google Scholar]

- El Mokni, R.; Iamonico, D. Bassia scoparia (Amaranthaceae s.l.) and Sesuvium portulacastrum (Aizoaceae), Two New Naturalized Aliens to the Tunisian Flora. Fl. Medit. 2019, 29, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Zahran, M.A. Forage Potentialities of Kochia indica and K. scoparia in Arid Lands with Particular Reference to Saudi Arabia. Arab. Gulf. J. Sci. Res. 1986, 4, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Jahandiez, É.; Maire, R.C.J.E. Catalogue des Plantes du Maroc; Imprimerie Minerva: Algiers, Algeria, 1934; Volume 3, pp. 1–559. [Google Scholar]

- Molero, B.; Montserrat, M. Quenopodiáceas Nuevas o Raras para la Flora de Marruecos. Lagascalia 2006, 26, 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chambouleyron, M.; Léger, J.-F. Contribution à la Connaissance de la Flore du Maroc Oriental—Moitié Orientale des Monts de Debdou et Environs d’Aïn Bni Mathar. Travaux l’Institut Sci. Série Bot. 2021, 43, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Tanji, A.; Taleb, A. New Weed Species Recently Introduced into Morocco. Weed Res. 1997, 37, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Kushunina, M.A.; Stepanova, N.Y.; Kalmykova, O.G.; Golovanov, Y.M.; Sennikov, A.N. Taxonomic Inventory and Distributions of Chenopodiaceae (Amaranthaceae s.l.) in Orenburg Region, Russia. Biodivers. Data J. 2024, 12, e121541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calonje, M.; Sennikov, A.N. In the Process of Saving Plant Names from Oblivion: The Revised Nomenclature of Ceratozamia fuscoviridis (Zamiaceae). Taxon 2017, 66, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennikov, A.N. The Taxonomic Circumscription and Nomenclatural History of Pilosella suecica (Asteraceae): A Special Case of Grey Literature in Taxonomic Botany. Plants 2024, 13, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennikov, A.N. Taraxacum stepanekii, a Replacement Name for Taraxacum roseolum Kirschner & Štěpánek Non Charit., with Nomenclatural Notes on the Taxonomic Legacy of Boris S. Kharitontsev in the Digital Era. Botanica 2024, 30, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, A. Vilmorin’s Blumengärtnerei, 3rd ed.; P. Parey: Berlin, Germany, 1896; Volume 1, pp. 1–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, A. On Kochia trichophylla. Dtsch. Gartenrat 1905, 140, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Stapf, O. Kochia scoparia, forma trichophila. Curtis’s Bot. Mag. 1919, 145. unpaginated text to Table 8808. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J.; Knees, S.G.; Cubey, H.S. (Eds.) The European Garden Flora, Flowering Plants: A Manual for the Identification of Plants Cultivated in Europe, Both out-of-Doors and Under Glass, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; Volume 2, pp. 1–652. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P. Gardeners Dictionary; C. Rivington: London, UK, 1735; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, O. Andreas Voß. Ein Nachruf für den Forscher und Reformator. Gartenwelt 1924, 28, 238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Post, T.; Kuntze, O. Lexicon Generum Phanerogamarum; Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt: Stuttgart, Germany, 1903; pp. 1–714. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, A. Garten-Botanik Nr. 2799. Bassia scoparia A. Voss. Dtsch. Gartenrat 1904, 2. Extra-Beilage 132. [Google Scholar]

- Maire, R.C.J.E. Flore de l’Afrique Du Nord; Lechevalier: Paris, France, 1962; Volume 8, pp. 1–303. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, A. Internationale Einheitliche Pflanzenbenennung. Dtsch. Gartenrat 1903, 1, 289–290. [Google Scholar]

- Moquin-Tandon, A. Chenopodiarum Monographica Enumeratio; P.-J. Loss: Paris, France, 1840; pp. 1–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Jha, P.; Jugulam, M.; Yadav, R.; Stahlman, P.W. Herbicide-Resistant Kochia (Bassia scoparia) in North America: A Review. Weed Sci. 2019, 67, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, J.; Randall, R. Eradication of Kochia (Bassia scoparia (L.) A.J.Scott, Chenopodiaceae) in Western Australia; Spafford, J.H., Dodd, J., Moore, J.H., Eds.; Shannon Books: Perth, Australia, 2002; pp. 300–303. [Google Scholar]

- Brignone, N.F.; Denham, S.S. Toward an Updated Taxonomy of the South American Chenopodiaceae I: Subfamilies Betoideae, Camphorosmoideae, and Salsoloideae. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2021, 106, 10–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimdahl, R.L. Weeds and Words: The Etymology of the Scientific Names of Weeds and Crops; Iowa State University Press: Ames, IA, USA, 1989; pp. 1–125. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, W.S.; Ferguson, I.K. The Genera of Chenopodiaceae in the Southeastern United States. Harv. Pap. Bot. 1999, 4, 365–416. [Google Scholar]

- Clemants, S.E. Chenopodiaceae. In Flora of Kanagawa; Association, F.K., Ed.; Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Natural History: Odawara, Japan, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cinq-Mars, L.; van den Hende, R. Kochia scoparia (L.) Roth (Chénopodiacées) Envahit Le Québec. Agriculture 1969, 26, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman, J.W. Another Ornamental Kochia. Gard. Chron. 1906, 39, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn, A. Kochia scoparia var. trichophylla. Gard. Chron. 1906, 39, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska, K.; Buzdygan, W.; Galanty, A.; Wróbel-Biedrawa, D.; Sobolewska, D.; Podolak, I. Current Knowledge on Genus Bassia All.: A Comprehensive Review on Traditional Use, Phytochemistry, Pharmacological Activity, and Nonmedical Applications. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22, 1197–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, A.J. The Kochias. Gardening 1906, 14, 188. [Google Scholar]

- Haage & Schmidt. Kochia trichophila. Möllers Dtsch. Gärtner-Ztg. 1906, 21, 219. [Google Scholar]

- Mabberley, D. The Plant-Book: A Portable Dictionary of the Vascular Plants; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997; pp. 1–858. [Google Scholar]

- Schmeiss, O. Kochia trichophylla. Möllers Dtsch. Gärtner-Ztg. 1906, 21, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Turland, N.; Wiersema, J.; Barrie, F.; Greuter, W.; Hawksworth, D.; Herendeen, P.; Knapp, S.; Kusber, W.-H.; Li, D.-Z.; Marhold, K.; et al. (Eds.) International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants; Koeltz Botanical Books: Glashütten, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–254. ISBN 978-3-946583-16-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters, A.J. Kochia trichophylla = K. scoparia. Möllers Dtsch. Gärtner-Ztg. 1906, 21, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Kochia trichophila. Gardening 1905, 14, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, G.F.; Figueiredo, E.; Bischofberger, M.; Eggli, U. Nomenclature of the Nothogenus Names × Graptophytum Gossot, × Graptoveria Gossot, and × Pachyveria Haage & Schmidt (Crassulaceae). Bradleya 2018, 36, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haage & Schmidt. Neuheiten von Samen Eigener Züchtung oder Einführung für 1904. Gartenflora 1904, 52, 576–577. [Google Scholar]

- Schalldach, I.; Wimmer, C.A. Die Erfurter Handelsgärtnerei Haage & Schmidt und Ihre Kataloge. Zandera 2012, 27, 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, L. Nachschrift der Redaktion. Möllers Deutsche Gärtn. Zeitung 1906, 21, 187. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, L.H. Manual of Cultivated Plants; The Macmillan Company: New York, NY, USA, 1924; pp. 1–851. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, A. Eine Sogenannte “Neue” Kochia trichophylla. Dtsch. Gartenrat 1905, 3, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Graebner, P. Chenopodiineae. In Synopsis der Mittereuropäischen Flora; Ascherson, P., Graebner, P., Eds.; Verlag von Gebrüder Borntraeger: Leipzig, Germany, 1919; Volume 5, pp. 1–219. [Google Scholar]

- POWO Plants of the World Online; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: London, UK, 2024.

- Doyle, J.J.; Doyle, J.L. A Rapid DNA Isolation Procedure for Small Quantities of Fresh Leaf Tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 1987, 19, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, B.G. Phylogenetic Utility of the Internal Transcribed Spacers of Nuclear Ribosomal DNA in Plants: An Example from the Compositae. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1992, 1, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.; Lickey, E.B.; Beck, J.T.; Farmer, S.B.; Liu, W.; Miller, J.; Siripun, K.C.; Winder, C.T.; Schilling, E.E.; Small, R.L. The Tortoise and the Hare II: Relative Utility of 21 Noncoding Chloroplast DNA Sequences for Phylogenetic Analysis. Am. J. Bot. 2005, 92, 142–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T.-Y.; Schaal, B.; Peng, C.-I. Universal Primers for Amplification and Sequencing a Non-Coding Spacer between the atpB and rbcL Genes of Chloroplast DNA. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 1998, 39, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, J.; Zimmer, E.A. Phylogeny and Biogeography of Panax L. (the Ginseng Genus, Araliaceae): Inferences from ITS Sequences of Nuclear Ribosomal DNA. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1996, 6, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukhorukov, A.P.; Fedorova, A.V.; Kushunina, M.; Mavrodiev, E.V. Akhania, a New Genus for Salsola daghestanica, Caroxylon canescens and C. carpathum (Salsoloideae, Chenopodiaceae, Amaranthaceae). PhytoKeys 2022, 211, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadereit, G.; Lauterbach, M.; Pirie, M.D.; Arafeh, R.; Freitag, H. When Do Different C4 Leaf Anatomies Indicate Independent C4 Origins? Parallel Evolution of C4 Leaf Types in Camphorosmeae (Chenopodiaceae). J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 3499–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Felsenstein, J. Evolutionary Trees from DNA Sequences: A Maximum Likelihood Approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981, 17, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for Inference of Large Phylogenetic Trees. In Proceedings of the 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), New Orleans, LA, USA, 14 November 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Findley, D.F. Counterexamples to Parsimony and BIC. Ann. Inst. Stat. Math. 1991, 43, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Character | Bassia scoparia | Bassia indica |

|---|---|---|

| Life form | annual, bushy or not, with lateral branches at an acute angle with the main axis | annual, bushy (tumbleweed) with horizontally spreading or deflexed lateral branches |

| Stem | glabrous to pubescent | pubescent |

| Leaves | linear to oblong, not recurved, glabrous, ciliate, or pubescent | lanceolate to oblong, often recurved, villous |

| Leaf axils | glabrous to pubescent | pubescent |

| Perianth | glabrous, ciliate, or hirsute (Central Asian and Siberian populations) | pubescent |

| Perianth outgrowths at fruiting stage | absent, tuberculate, or winged (plants heterodiasporic) | usually winged |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sukhorukov, A.P.; Wen, Z.; Krinitsina, A.A.; Fedorova, A.V.; Verloove, F.; Kushunina, M.; Léger, J.-F.; Chambouleyron, M.; Tanji, A.; Sennikov, A.N. A Revised Taxonomy of the Bassia scoparia Complex (Camphorosmoideae, Amaranthaceae s.l.) with an Updated Distribution of B. indica in the Mediterranean Region. Plants 2025, 14, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14030398

Sukhorukov AP, Wen Z, Krinitsina AA, Fedorova AV, Verloove F, Kushunina M, Léger J-F, Chambouleyron M, Tanji A, Sennikov AN. A Revised Taxonomy of the Bassia scoparia Complex (Camphorosmoideae, Amaranthaceae s.l.) with an Updated Distribution of B. indica in the Mediterranean Region. Plants. 2025; 14(3):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14030398

Chicago/Turabian StyleSukhorukov, Alexander P., Zhibin Wen, Anastasiya A. Krinitsina, Alina V. Fedorova, Filip Verloove, Maria Kushunina, Jean-François Léger, Mathieu Chambouleyron, Abbès Tanji, and Alexander N. Sennikov. 2025. "A Revised Taxonomy of the Bassia scoparia Complex (Camphorosmoideae, Amaranthaceae s.l.) with an Updated Distribution of B. indica in the Mediterranean Region" Plants 14, no. 3: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14030398

APA StyleSukhorukov, A. P., Wen, Z., Krinitsina, A. A., Fedorova, A. V., Verloove, F., Kushunina, M., Léger, J.-F., Chambouleyron, M., Tanji, A., & Sennikov, A. N. (2025). A Revised Taxonomy of the Bassia scoparia Complex (Camphorosmoideae, Amaranthaceae s.l.) with an Updated Distribution of B. indica in the Mediterranean Region. Plants, 14(3), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14030398