Abstract

Sociophonetic competence—a component of sociolinguistic and, thus, communicative competence—has been explored in both learner production and perception. Still, little is known about the relationship between learners’ ability to account for sociophonetic variability in the input and their likelihood to produce such variation in output. The present study explores 21 learners’ preference for a specific sociophonetic variant on an aural preference task and the same learners’ patterns of production of the variant in semi-spontaneous speech. The sociolinguistic variable considered is Spanish intervocalic /d/, variably realized as approximant [ð] or deleted based on numerous (extra)linguistic factors, including the speaker’s gender, the vowel that precedes /d/, and the grammatical category and lexical frequency of the word containing /d/. Results reveal that preference for and production of a deleted variant increased with learner proficiency. Moreover, regardless of proficiency, learners generally selected deleted /d/ more than they produced it, suggesting that sociophonetic awareness precedes reliable production. Learners’ production of a deleted variant was influenced by the preceding vowel, the grammatical category of the word containing /d/, and the word’s lexical frequency, and sensitivity to these predictors was especially observed as proficiency increased. Learners produced the deleted variant more after /o/, in adjectives and nouns, and in frequent words.

1. Introduction

Sociolinguistic competence encompasses, among other things, knowledge about linguistic forms whose use varies systematically according to linguistic, geographic, social, and contextual factors. Such knowledge contributes to language users’ ability to interpret social cues embedded in linguistic messages and to deploy their own linguistic resources to manage social relationships (e.g., Geeslin & Long, 2014). The present study focuses on sociophonetic variation—that is, sociolinguistic variation at the level of the sound. A growing body of research has documented second language (L2) learners’ ability to produce sociophonetic variation as well as their ability to perceive it (as detailed in next section); nevertheless, few studies have explored the relationship between such perception and production. Understanding how perception or interpretation of such variation is related to learners’ productive patterns is important for understanding the process of developing sociophonetic competence more broadly. This project explores the relationship between learners’ ability to account for sociophonetic variation in the input and their likelihood of producing such variation in their own speech.

2. Research Background

2.1. L2 Sociophonetic Competence

Sociolinguistic competence—a key component of communicative competence (Canale & Swain, 1980; see Kanwit & Solon, 2023)—comprises knowledge about language use and discourse rules that enables language users to employ and interpret language for social meaning. Agile communication in a L2 thus often requires (deploying) knowledge about variable, context-dependent features of that language in both comprehension and expression. Research on L2 variation often distinguishes between Type I or vertical variation—that is, developmental variation between “targetlike” and “nontargetlike” forms (e.g., variation between “went” and regularized *“goed”, respectively)—and Type II or horizontal variation—that is, variation in response to linguistic, social, and geographic factors that is also found in native (i.e., first-language (L1)) speech (Adamson & Regan, 1991; Rehner, 2002). It is acquisition of Type II variation that is of interest in the present study. Although much early work on Type II variation focused on L2 morphosyntactic variation, a sizable and growing body of research has analyzed L2 sociophonetic variation, exploring aspects related both to the production and perception of variation and of specific variable features of the target language.

2.1.1. Production

Research on L2 sociophonetic competence has often explored learners’ production of particular target language variants, typically reporting rates of and constraints on use of regional variants or of sociolinguistically variable phonetic features (e.g., L2 Spanish: Peninsular /θ/: Geeslin & Gudmestad, 2008; George, 2014; Knouse, 2012; Pope, 2023; Ringer-Hilfinger, 2012; Peninsular [χ]: George, 2014; Pope, 2023; /s/ weakening: Escalante, 2018b, 2021; Geeslin & Gudmestad, 2008; /d/ deletion: Solon et al., 2018; Argentine sheísmo/zheísmo: Pozzi, 2022; Pozzi & Bayley, 2021; L2 French: /l/ elision: Howard et al., 2006; Kennedy Terry, 2017; Regan et al., 2009; schwa realization: Kennedy Terry, 2022; Uritescu et al., 2002; phrase-final vowel devoicing: Dalola & Bullock, 2017; L2 Arabic: Cairene [g]: Raish, 2015). Many studies have found low rates of production of region-specific or socially constrained variants by L2 learners. For example, after a semester abroad in Madrid, Ringer-Hilfinger (2012) reported that her 15 learners produced Peninsular Spanish /θ/ in only 2.8% of possible contexts, and all of these cases were produced by just two learners (with the other 13 learners exhibiting no use of /θ/). Geeslin and Gudmestad (2008) found that only five of their 130 L2 Spanish learners exhibited any /s/ weakening, a common regionally and socially constrained variable phonetic feature of Spanish. Nevertheless, other studies uncover substantial learner adoption of region-specific variation. For example, Pozzi and Bayley’s (2021) learners exhibited high rates of use of Argentine sheísmo/zheísmo (i.e., [ʃ] or [ʒ] for the graphemes <ll> and <y>) by the end of their semester in Buenos Aires (i.e., in 89% of possible contexts as compared to 4.7% of contexts at the beginning of their sojourn). Similarly, the learners investigated in Raish (2015) used the Cairene [g] in 62% of possible contexts by the end of their time in Cairo (either one semester or a full academic year). Thus, rates of adoption of phonetic variants that encode regional and/or social information vary widely across languages, learners, and segments.

2.1.2. Perception

Research has also explored L2 sociophonetic competence with regard to learners’ perceptual abilities and patterns. Research in this vein has explored such topics as the categorical perception of a regional variant (e.g., whether L2 learners categorize a regional variant as the intended phoneme or as a variant of another phoneme; Del Saz, 2019; Escalante, 2018b; Schmidt, 2018), the influence of regional/dialectal input on L2 phonemic discrimination (e.g., Baker & Smith, 2010; Smith & Baker, 2011); L2 comprehension as related to dialectal phonetic/phonological features present in speech (e.g., Schmidt, 2009; Schoonmaker-Gates, 2017; Trimble, 2014); L2 learners’ dialect identification abilities (e.g., Schmidt, 2022; Schoonmaker-Gates, 2017); and learner attitudes toward and attachment of meanings to specific varieties (Geeslin & Schmidt, 2018; Grammon, 2024; Schmidt & Geeslin, 2022) and variants (Chappell & Kanwit, 2022). In general, this body of research points to learners’ development of perceptual and interpretive acumen related to a wide range of sociophonetic variants and information as learner proficiency and experience with the language increase. The question remains, however, of how learners’ abilities to perceive and interpret sociophonetic variation are related to their production patterns.

2.1.3. Perception–Production Link

To our knowledge, only one study to date has explored both perception and production of a sociolinguistically variable phonetic feature in the same sample. Escalante (2018a) examined the perception and production of Spanish /s/ weakening by 14 humanitarian volunteers during a year abroad in coastal Ecuador. Spanish /s/ weakening refers to the production of a, typically coda, Spanish /s/ as [h] or [Ø] as in casas “houses” produced as [kasah] or [kasa] rather than [kasas]. Escalante found that nearly all learners exhibited gains in perceiving aspirated /s/ (i.e., [h]) as /s/ during time abroad. Nevertheless, in terms of production, only 4.6% of all /s/ tokens collected over the entire year abroad exhibited weakening, and 74.1% of all weakened tokens were produced by just one speaker. Of this finding, Escalante wrote, “This suggests that gains in perception are not necessarily reflective of gains in production and that learners can still show evidence of gains in sociolinguistic competence even if they do not produce the local [variants]” (p. v).

Understanding the link between production and perception is a central goal of the larger field of L2 speech research (Nagle & Baese-Berk, 2022). For example, L2 speech researchers, broadly speaking, are interested in understanding such questions as whether there is a certain “threshold” of perception accuracy needed before the production of a certain phone improves, whether changes in perception are reflected in production, and whether the link between perception and production (as well as the strength of such a link) changes over time. When applied to questions related to the acquisition of variation in sounds, similar as well as different questions are of interest. For example, we want to know whether perception of a particular variant is necessary before a learner might produce such a variant. We also ask whether there is a perception threshold that is necessary prior to the appearance of the variant in speech and, if so, what type of perceptual knowledge or ability is necessary. Finally, we are interested in whether learners who show perceptual knowledge of a variant also produce it and why or why not. Research investigating this perception-production link has the potential to shed light on how the acquisition of sociophonetic variation proceeds. This study thus aims to explore these questions using the perception and production of variable Spanish intervocalic /d/ deletion as the sociophonetic variant of interest.

2.2. Spanish Intervocalic /d/ Deletion

2.2.1. L1 Spanish

The target feature explored in this study is the variable realization of Spanish intervocalic /d/ as an approximant (e.g., cantado “sung” as [kanáðo]) or deleted (e.g., [kanáo]). Deletion of Spanish intervocalic /d/ in L1 Spanish has been widely investigated in the sociolinguistic literature since at least the mid-1980s and is well documented in numerous regional varieties of Spanish. Table 1 summarizes several major findings regarding the presence and rate of intervocalic /d/ deletion in Spanish.

Table 1.

Rates of intervocalic /d/ deletion across studies and varieties of Spanish.

This literature has shown that L1 Spanish patterns of intervocalic /d/ deletion versus realization are affected by various linguistic factors (e.g., grammatical category, phonetic context, lexical frequency) as well as social factors (e.g., speaker gender, socioeconomic status). For example, deletion has been shown to be favored in past participles (e.g., Blas Arroyo, 2006; Díaz-Campos & Gradoville, 2011; Samper Padilla, 1996), in more frequent lexical items and types (e.g., Alba, 1999; Bedinghaus & Sedó, 2014; Blas Arroyo, 2006; Díaz-Campos & Gradoville, 2011; Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, 2009), and when the /d/ is preceded by /a/ and followed by /o/ (though the confounding role of past participles has not always been fully considered; Moya Corral & García Wiedemann, 2009). In terms of social factors, deletion has been found to be more prevalent among men (e.g., Samper Padilla, 1996; Uruburu Bidaurrázaga, 1994) and among speakers of lower socioeconomic status (e.g., Alba, 1999; D’Introno & Sosa, 1986; Uruburu Bidaurrázaga, 1994; although see an exception in Hernández-Campoy & Jiménez-Cano, 2003).

2.2.2. L2 Spanish

Research that has explored the acquisition of /d/ among L2 learners of Spanish has mainly focused on the targetlike production of /d/ as an approximant as compared to as a stop (often in conjunction with /b/ and /ɡ/; e.g., Alvord & Christiansen, 2012; Face & Menke, 2009; Lord, 2010; Zampini, 1994). A few studies have explored the acquisition of intervocalic /d/ variation. With regard to production, Solon et al. (2018) compared /d/ production in the speech of 13 advanced L2 learners of Spanish to that of 13 L1 Spanish speakers. They found that the advanced L2 learners did exhibit /d/ deletion in their speech but at much lower rates than the L1 Spanish speakers (i.e., 18.0% vs. 44.5%, respectively). They also observed a wide range of rates of deletion among individual learners (i.e., from 1.2% to 68.4%). With regard to the factors observed to influence /d/ realization versus deletion, Solon et al. found that L1 Spanish speakers’ patterns were affected by several independent variables including preceding and following vowels, grammatical category of the word containing /d/, and stress. The L2 learners, in contrast, were mostly influenced by the frequency of the lexical items containing /d/.

To better understand learners’ sociophonetic competence, Solon and Kanwit (2022) used an aural contextualized preference task to explore whether L2 learners exhibit sensitivity to the sociolinguistic constraints on /d/ realization versus deletion in Spanish (regardless of learners’ production of the phone). The 50 learners participating in Solon and Kanwit (2022) read a “movie script” representing a dialogue between two characters (siblings). When prompted, they would listen to two different “takes” of an isolated word within one particular scene of the movie. The two takes were identical except for the realization of the intervocalic /d/ (one included an approximant realization of /d/, the other a deleted /d/). Participants were instructed to imagine that they were film directors and had to select which of the two takes (or stimuli) best fit within the scene (or context). Contexts were systematically manipulated to control for/explore speaker gender (man, woman), grammatical category of the word containing /d/ (noun, adjective, verb, participle), vowel preceding /d/ (high /i/, low /a/), and lexical frequency of the word containing /d/ (high versus low as determined following Erker & Guy, 2012; lexical items constituting 1% or more of the tokens with relevant characteristics in the Davies’ Corpus del español: Web/Dialects (Davies, 2016) were categorized as high-frequency; those constituting less than 1% were categorized as low frequency). More specific information about the task can be found in Solon and Kanwit (2022). Results revealed that five learners categorically selected realized /d/, and one learner categorically selected the token with a deleted /d/. All other learners exhibited variation in their selection. Table 2 summarizes the rates of selection of realized versus deleted /d/ across the three learner proficiency groups.

Table 2.

Selection of responses in the contextualized preference task in Solon and Kanwit (2022); adapted from Solon and Kanwit (2022, p. 814).

As shown in Table 2, as learner proficiency increased (as determined by a Spanish elicited imitation task (EIT); Solon et al., 2019), so too did rates of selecting the deleted /d/. Table 3 summarizes the results of Solon and Kanwit’s mixed-effects binomial regression to explore the factors constraining learner selection of deletion.

Table 3.

Summary of Solon and Kanwit’s (2022) regression results.

As shown in Table 3, the factors constraining learners’ selection of a deleted /d/ differed by learner proficiency group, with the most advanced learners in the sample selecting a deleted /d/ more often when the speaker was a man, when the vowel preceding /d/ was the low vowel /a/, and when the word containing /d/ was an adjective or a participle.

3. Present Study

The present study extends Solon and Kanwit (2022) and broadly seeks to understand how patterns of preference relate to what the same learners produce in oral speech. For example, to what extent do learners who prefer deleted /d/ in certain contexts also produce it (and in what contexts), and do learners who produce deleted /d/ in speech also show preference for the variant in an offline task? Specifically, this study is guided by four research questions:

- With what frequency do (a subset of) the L2 learners of Spanish from Solon and Kanwit (2022) produce a deleted intervocalic /d/?

- What factors constrain production of the deleted variant for these learners?

- To what extent are differences observed (in frequency and constraining factors) as proficiency increases?

- What is the relationship between preference for and production of deleted intervocalic /d/ across individual learners and as proficiency increases?

3.1. Materials and Method

3.1.1. Participants

The participants of the present study are 21 learners of Spanish; they represent the subset of the 50 learners examined in Solon and Kanwit (2022) who completed both the preference task and a production task (described in the next subsection). Learners from each of the three proficiency groups described in Solon and Kanwit (2022) are represented in this subset, although the present study will operationalize proficiency via EIT scores as a continuous measure rather than grouping learners categorically to more fully and faithfully capture and account for learner proficiency (Pfenninger & Festman, 2021). Table 4 summarizes the language background characteristics of the present subset of learners, also making reference to their proficiency group in Solon and Kanwit (2022). All names provided are pseudonyms and reflect the gender identity of the participant.

Table 4.

Summary of participant characteristics.

If participants reported time abroad, they were asked to provide information about where abroad they had spent time and for how long (e.g., “Spain for one month, Dominican Republic for 3 months”). Nevertheless, because learners varied in the level of regional detail they provided and because /d/ deletion is a widespread phenomenon across Spanish varieties and its prevalence varies both across and within Spanish-speaking regions, we consider time abroad holistically rather than according to time in specific (e.g., /d/-deleting) regions.

3.1.2. Tasks

Participants completed a language background questionnaire; a monologic narrative “role-play” task; the 32-item contextualized preference task with an aural component, described previously and in detail in Solon and Kanwit (2022); and the Spanish EIT (Bowden, 2016; Ortega et al., 2002; Solon et al., 2019). In the narrative (production) task, participants were presented with five scenarios one at a time and were asked to speak as much as they could about each scenario. They were given 1 min to read each prompt and 3 min and 45 s to speak. The task was programmed into Powerpoint, and the slides automatically advanced at the end of the allotted time; this was instituted to encourage participants to speak until the slide advanced (rather than having participants advance themselves when finished). An example prompt is included in Appendix A.

3.1.3. Coding

All tokens of intervocalic /d/ in the narrative data were identified and coded by the first author as deleted versus realized; in the present study, we did not distinguish between different types of /d/ realization (e.g., stop versus approximant). Additionally, the contexts in which the /d/s occurred were coded for preceding vowel (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/), grammatical category (adjective, noun, participle, verb, pronoun, adverb), and lexical frequency (frequent, not frequent; determined in the same manner as Solon & Kanwit, 2022, described previously). Note that, because this was production, the possible categories for the extralinguistic factors investigated were broader than those included in the preference task and were determined by what appeared in the production data.

3.1.4. Analysis

Frequency analyses were used to account for rates of production of realized versus deleted /d/ across learner groups. A mixed-effects regression was run to determine significant predictors constraining production of one variant over another (i.e., deletion over realization). Finally, to answer the overarching question of the present study, we compared learners according to EIT score, time abroad, rate of production of deletion, and rate of selection of deletion. We performed Pearson correlations to see if any pairs of the four aforementioned characteristics correlated, and we supplement this analysis with qualitative consideration of how individual learners fit these overarching patterns.

4. Results

We begin by reporting the overall rates of realization and deletion for our three participant groups. We then turn to the role of independent predictors in the conditioning of deletion in a mixed-effects regression. Finally, we make comparisons between the production data and the previously reported preference data.

4.1. Production

Overall, our learners produced 1665 tokens of intervocalic /d/ (M number of /d/ tokens per participant = 79.33; range 9–150): 88.7% of these (1477/1665) were realized and 11.3% (188) were deleted. Individual rates of deletion across the 21 participants ranged from 0% (with four learners categorically producing a realized /d/) to 29.49%.

To determine the possible role of contextual factors on /d/ deletion, we then performed a mixed-effects binomial regression. The four categorical participants were excluded from the regression analysis, which thus includes the 17 learners who demonstrated variation. Of the predictors considered, four were significant and included in the best-fit model: preceding vowel, grammatical category, lexical frequency, and the learner’s EIT score. Other predictors that were considered but were not significant included the learner’s rate of selection of /d/ (continuous value) in the prior study’s preference task, the number of months the learner had spent abroad (continuous value),1 and the learner’s gender. The individual participant and the lexical item in which the word appeared were entered as random effects. We also tested for interactions among the predictors, none of which were significant.

The output of the best-fit model is summarized in Table 5. Deletion is the variant being predicted, so positive estimates and z-values indicate greater deletion, whereas negative values indicate more realization. Values further from 0 indicate stronger effects. Standard errors refer to the level of variability within a particular category. P-values below 0.05 indicate that a particular comparison is statistically significant and correspond with 95% confidence intervals that do not cross 0 (i.e., that have two positive or two negative values). For each categorical predictor, one category serves as the reference level and is the point of comparison for the other value(s). For instance, in the second bolded results row, we see that lexical items classified as “not frequent” have a negative estimate and z-value, meaning that relative to frequent lexical items, non-frequent were significantly less likely to result in deleted /d/.

Table 5.

Mixed-effects binomial regression of learner /d/ deletion (reference level: realization).

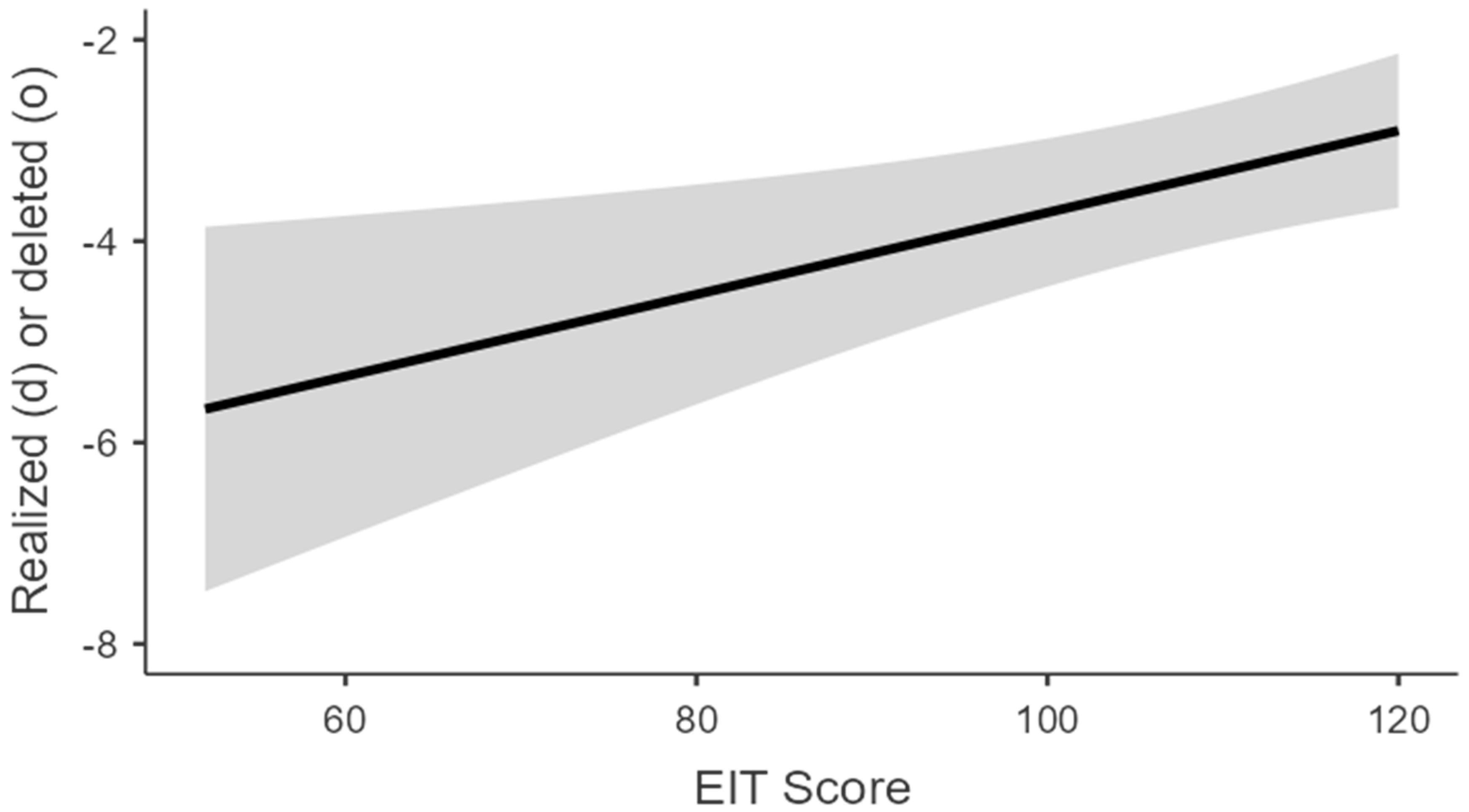

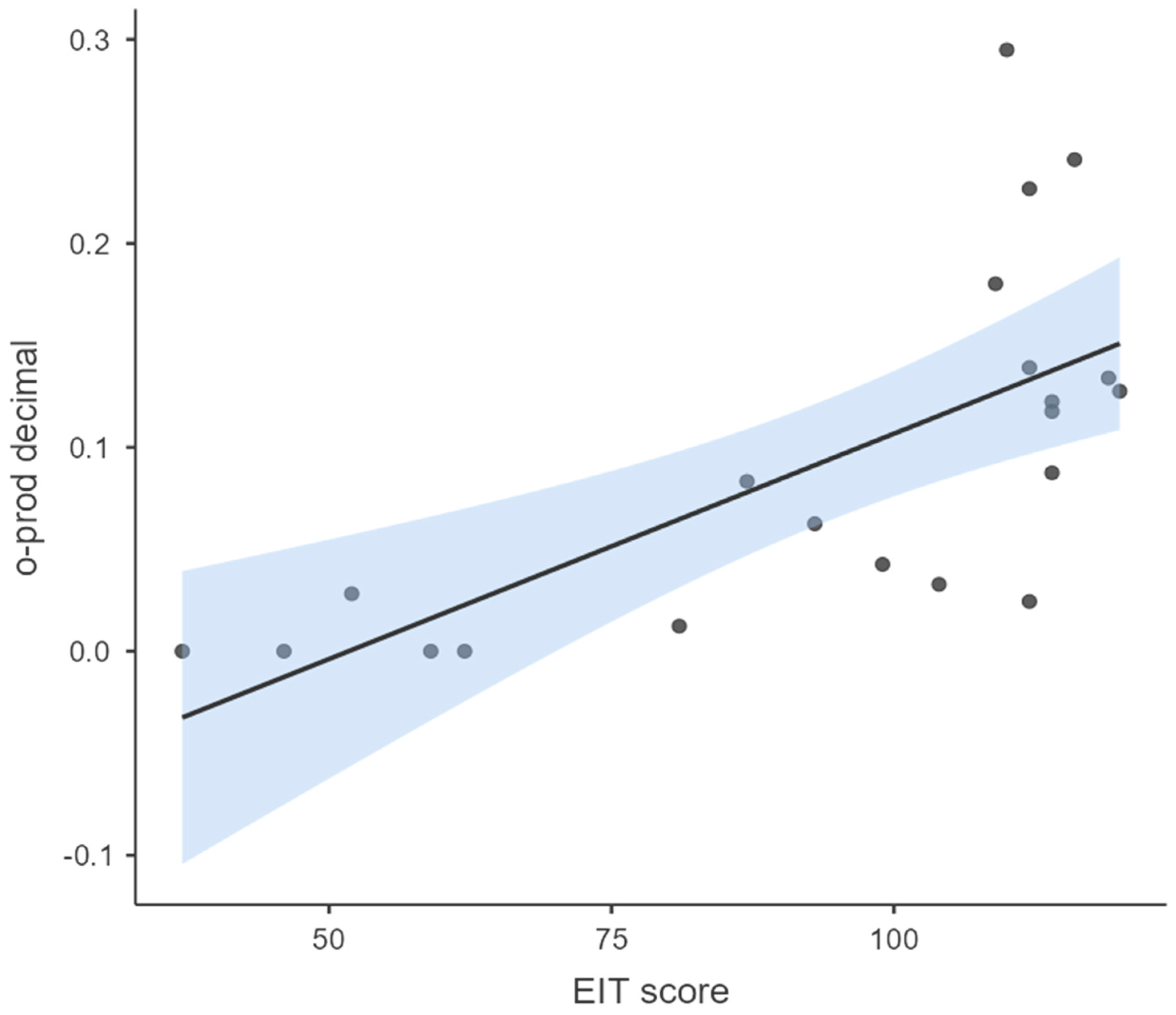

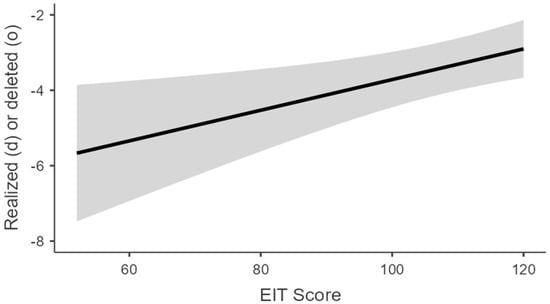

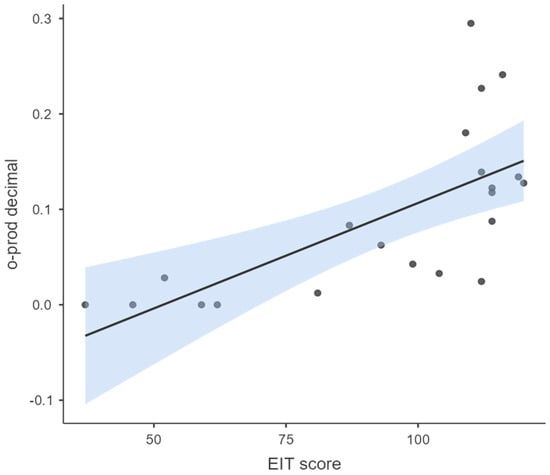

Learners’ Spanish proficiency, as measured by their EIT score (a continuous value), significantly predicted /d/ deletion. The positive value of the estimate (0.05) and z (3.49) indicate that as EIT score increased the likelihood of deleting /d/ also increased. Figure 1 illustrates this pattern, plotting the relationship between EIT score (with 95% confidence interval shaded) and deletion of /d/ from our model. The upward slope of the line follows the fact that as EIT score increased, so too did the rate of deletion. Nevertheless, the negative values on the y-axis for deletion of /d/ serve as a reminder that even learners who were more likely to delete (i.e., had higher EIT scores), still produced /d/ more often than they deleted it. For instance, a value of −4 on the y-axis indicates that learners were four times less likely to delete /d/ than to produce it (i.e., 20% deletion and 80% realization). EIT score did not significantly interact with any of the other predictors. Nevertheless, as we explain the results of the regression, we also present figures for the other predictors that show further information divided according to EIT score (p < 0.001), given our interest in visualizing the extent to which learners showed sensitivity to contextual linguistic factors as EIT scores increased. As will be seen in the subsequent figures, the greater rate of deletion exhibited by learners with higher EIT scores was usually the result of a more extreme effect for categories that favored deletion for our learners overall.

Figure 1.

Production of /d/ by EIT score (95% confidence interval shaded).

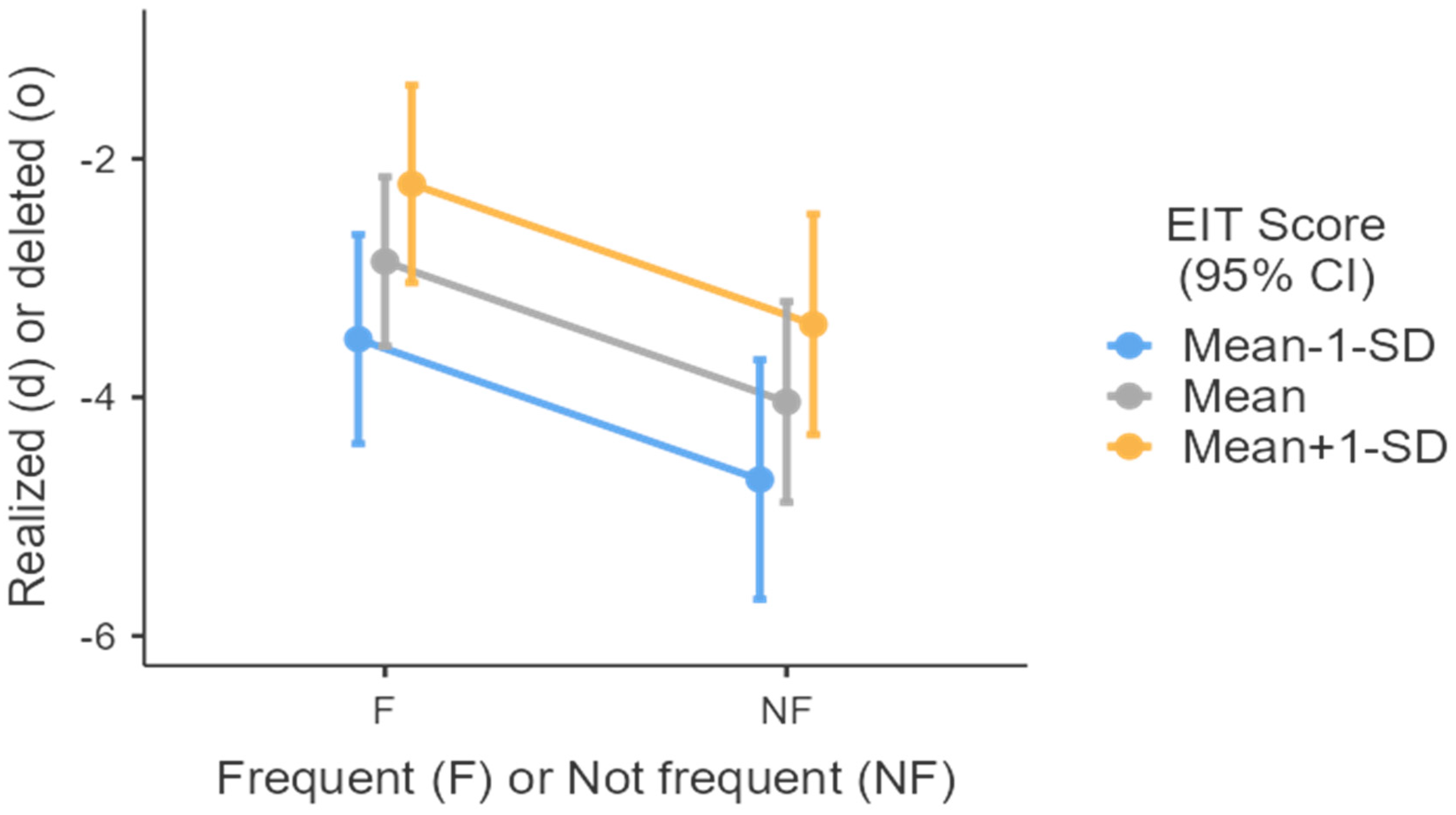

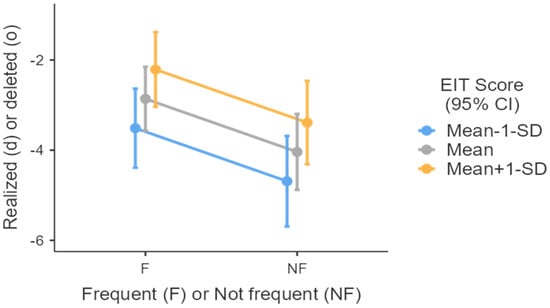

Lexical frequency was also a significant predictor of /d/ deletion; learners were significantly less likely to delete /d/ when words were infrequent as compared to frequent (Table 5). Figure 2 illustrates this pattern, while showing additional detail according to EIT score. Namely, although learners overall deleted /d/ significantly more with frequent lexical items, we can see that this was especially driven by learners with higher EIT scores. When learners’ EIT scores were more than one standard deviation above the mean, we note that they showed the highest likelihood of deleting /d/ with frequent lexical items, followed by learners whose EIT scores were within one standard deviation of the EIT mean, and lastly by learners whose EIT scores were more than one standard deviation below the mean.

Figure 2.

Production of /d/ by lexical frequency across EIT scores.

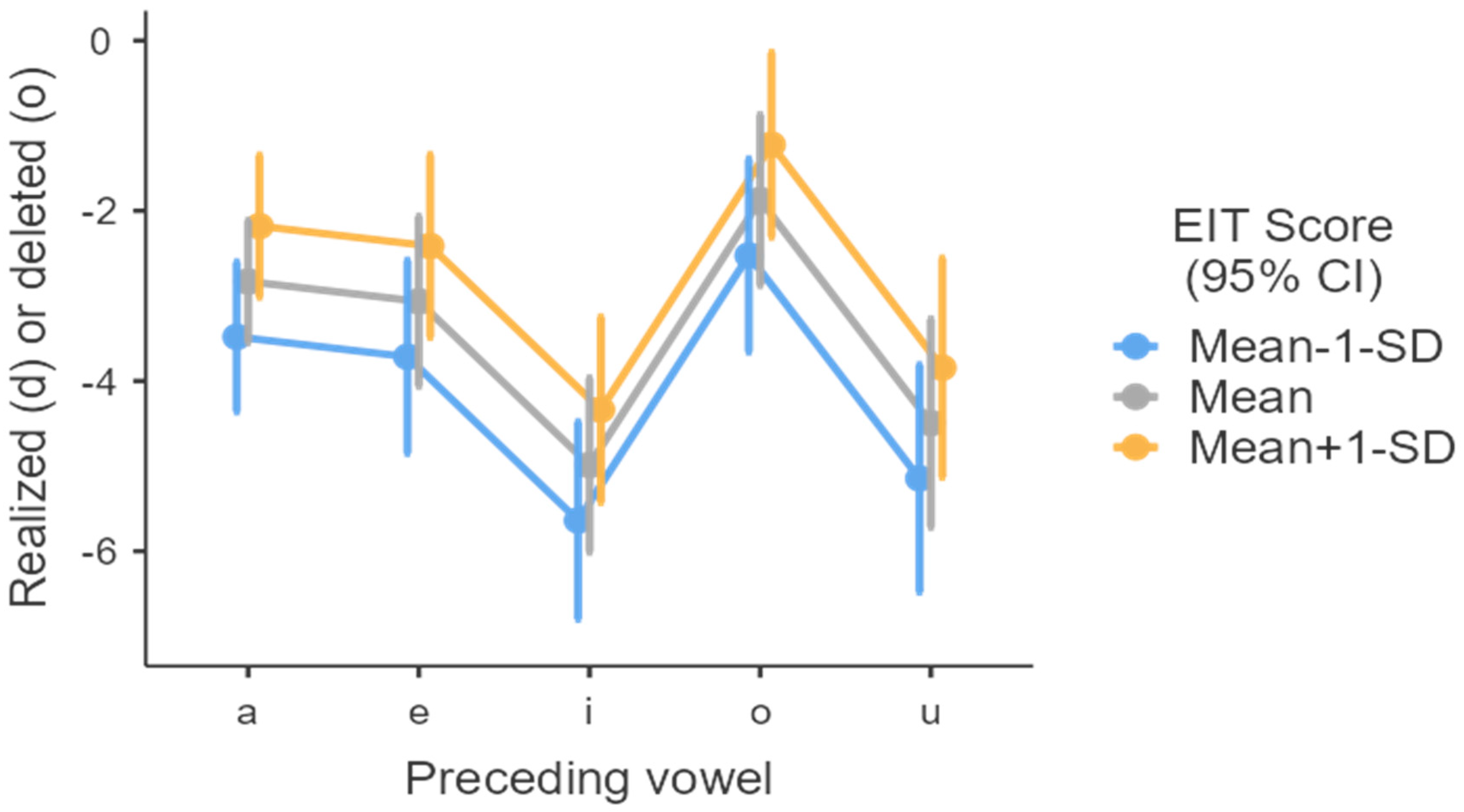

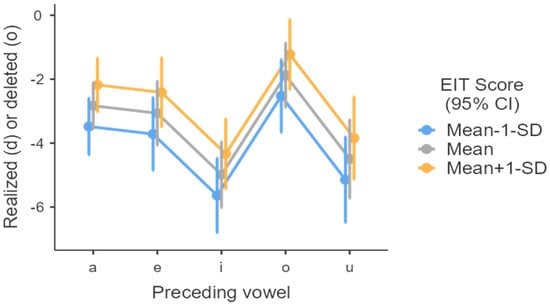

With respect to the preceding vowel (Table 5), compared to the reference level of a preceding /a/, learners deleted /d/ significantly less when the preceding vowel was /i/ or /u/. Comparisons with /e/ and /o/ were not significant. A closer look using EIT score (Figure 3) revealed that the higher rates of deletion for preceding /o/ and low rates for /u/ and /i/ were again driven by learners with EIT scores more than one SD above the mean and those within one SD of the mean, although once again, differentiation was greater for the former group, who showed especially high deletion with preceding /o/.

Figure 3.

Production of /d/ by preceding vowel across EIT scores.

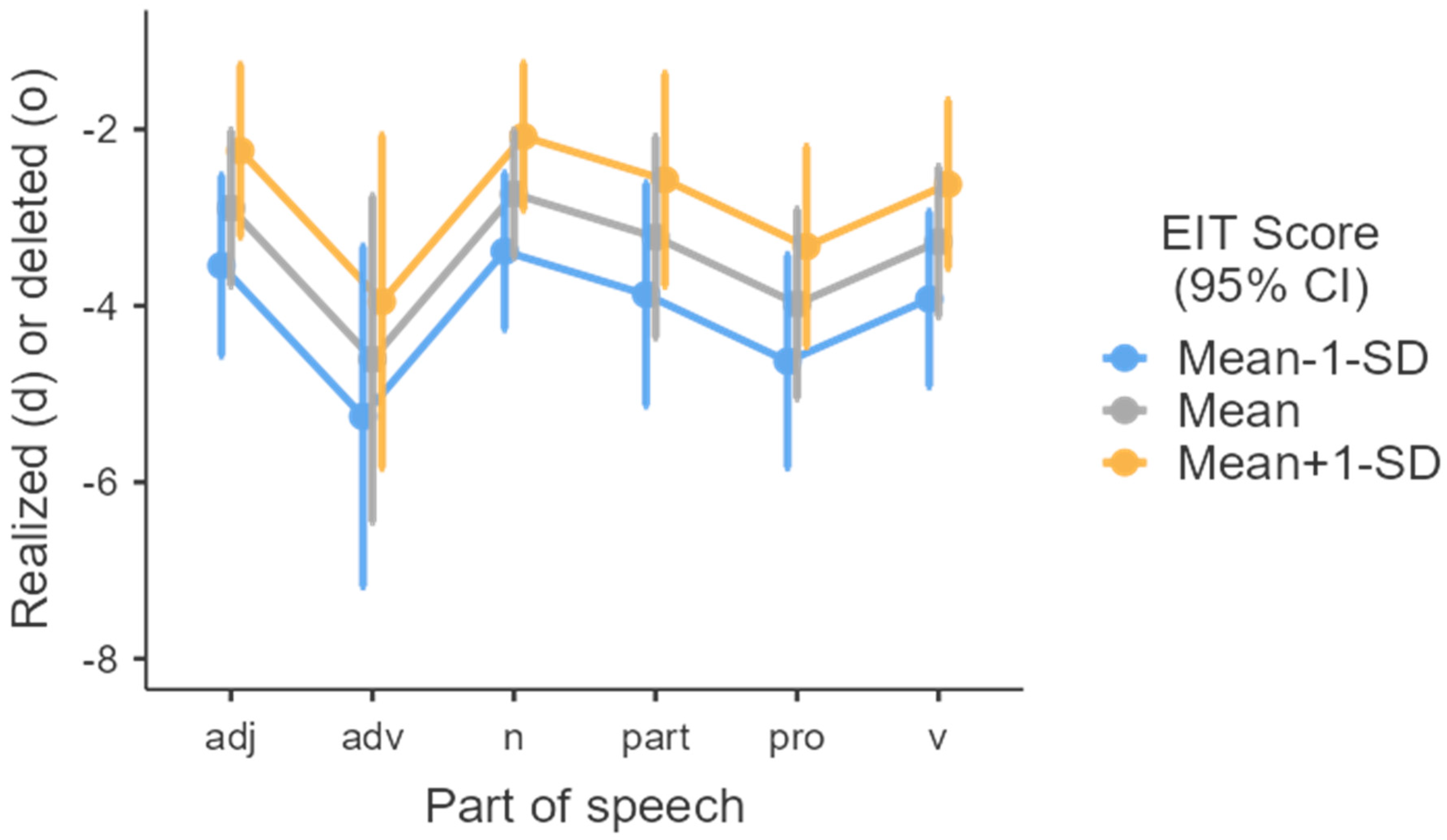

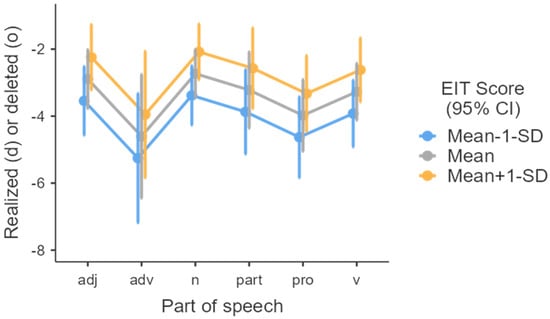

For the final predictor, the grammatical category of the word that contained /d/, learners deleted /d/ significantly less when the word was a pronoun, compared to when it was an adjective (Table 5). They also deleted less when the word was an adverb (although this comparison was not statistically significant: p = 0.073). Figure 4 illustrates that deletion occurred at the highest rates with adjectives and nouns and at the lowest rates with adverbs, pronouns, and verbs, and that learners with EIT scores more than one standard deviation above the mean again showed greater differentiation across categories, especially driving the overall higher rates of deletion in adjectives and nouns.

Figure 4.

Production of /d/ by grammatical category across EIT scores.

We now turn to consideration of individual participants across our production and preference data.

4.2. Preference–Production

In Table 6, we present individual data arranged in ascending order of EIT score. For the 21 participants, we tested for the Pearson correlation between the following variables in pairs: EIT score, production of deletion, selection of deletion, and months abroad. We note the result of each test and provide visualizations in the subsequent scatterplot figures.

Table 6.

Individual rates of production, selection, and other attributes.

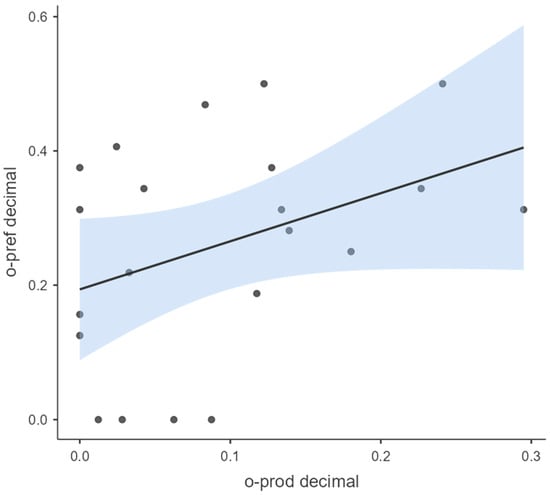

For one, Table 6 serves as a reminder that participants who did not produce deleted /d/ were those with the lowest EIT scores. We can also note that, in general, participants with the highest EIT scores tended to produce deleted /d/ at least 10% of the time, although Maddie was an exception to this pattern, with a rather high EIT score (112) and a rate of deletion of just 2.44%. Figure 5 shows a scatterplot of the learners by EIT score and rate of production of deletion. A Pearson correlation revealed a significant, positive correlation between EIT score and production of deletion, r(19) = 0.68 [95% CI: 0.35, 0.86], p < 0.001. Consequently, in Figure 5, we can note how the learners who produced higher rates of deletion tended to have EIT scores above 100, with those scoring above 109 the only to show rates of deletion at or above 8.75% (see Table 6). This positive correlation is exemplified by learners who had high (although not necessarily the very highest) EIT scores and produced deletion at relatively high rates. For instance, the three highest individual rates of production of a deleted /d/ belonged to Tiff (29.49%), Steph (24.11%), and Lainey (22.68%). Their respective EIT scores of 110, 116, and 112 were high albeit still not at the extreme end of the EIT scale in the high group.

Figure 5.

Scatterplot of individual participants by EIT score and rate of deletion (production task).

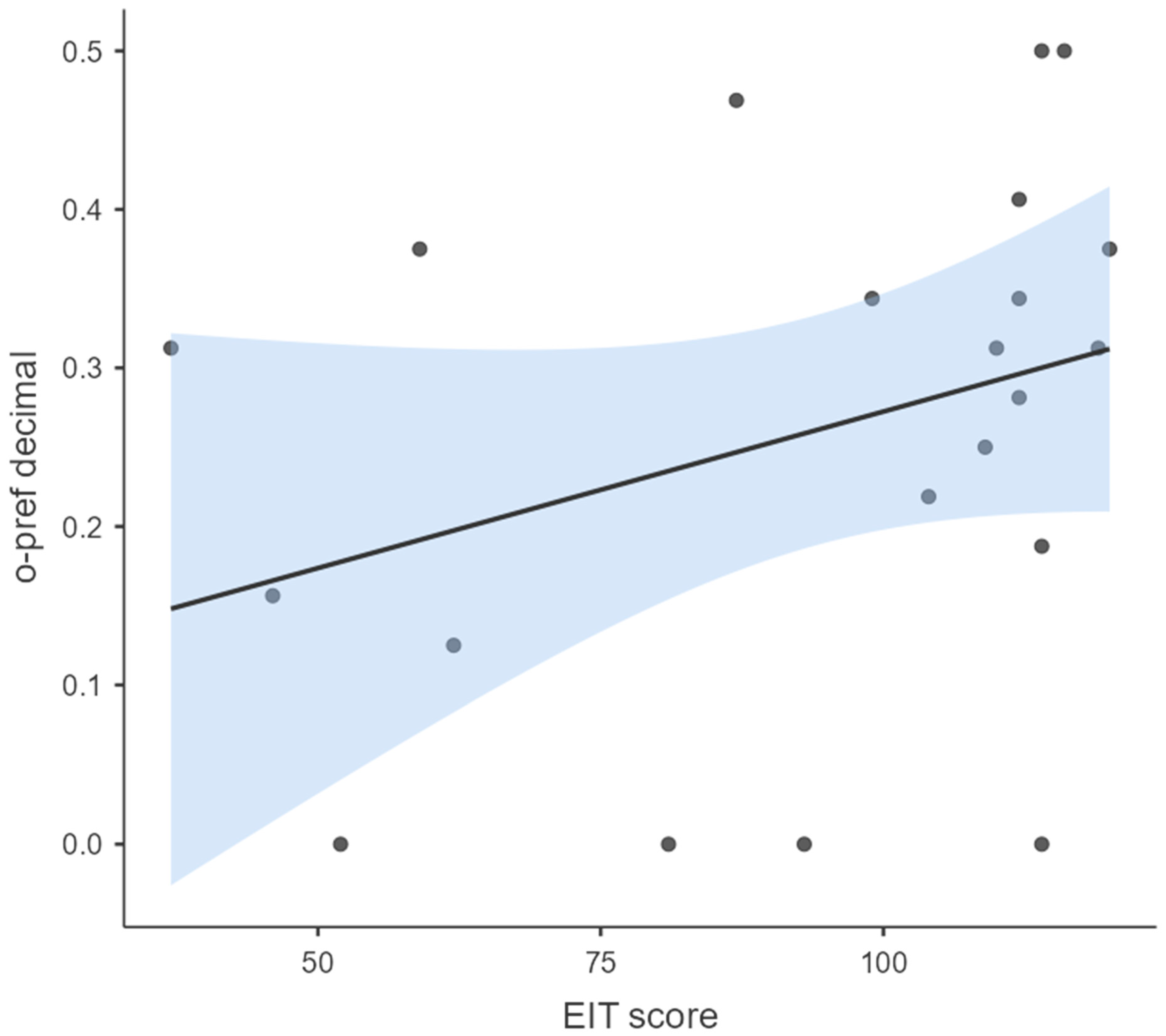

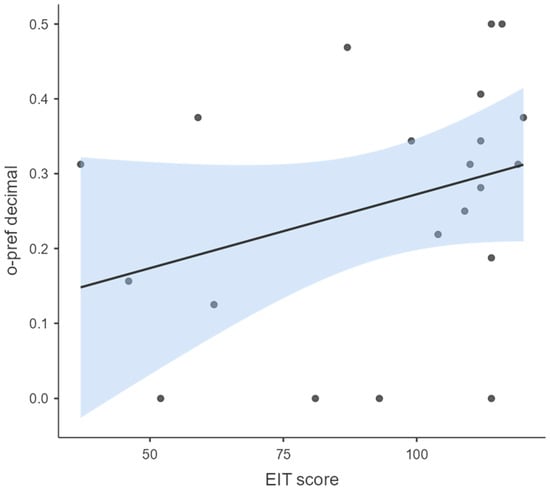

Although greater rates of selection of deletion in the preference task tended to occur with higher EIT scores (i.e., a positive relationship), there was no significant correlation between EIT score and selection of deletion, r(19) = 0.32 [95% CI: −0.12, 0.66], p = 0.153. In Figure 6, we can observe generally higher selection of deletion for the higher EIT scores; however, note that some learners with high scores selected little deletion and some learners with lower scores yielded rather high rates of deletion, contributing to the overall lack of correlation.

Figure 6.

Scatterplot of individual participants by EIT score and rate of selection of deletion (preference task).

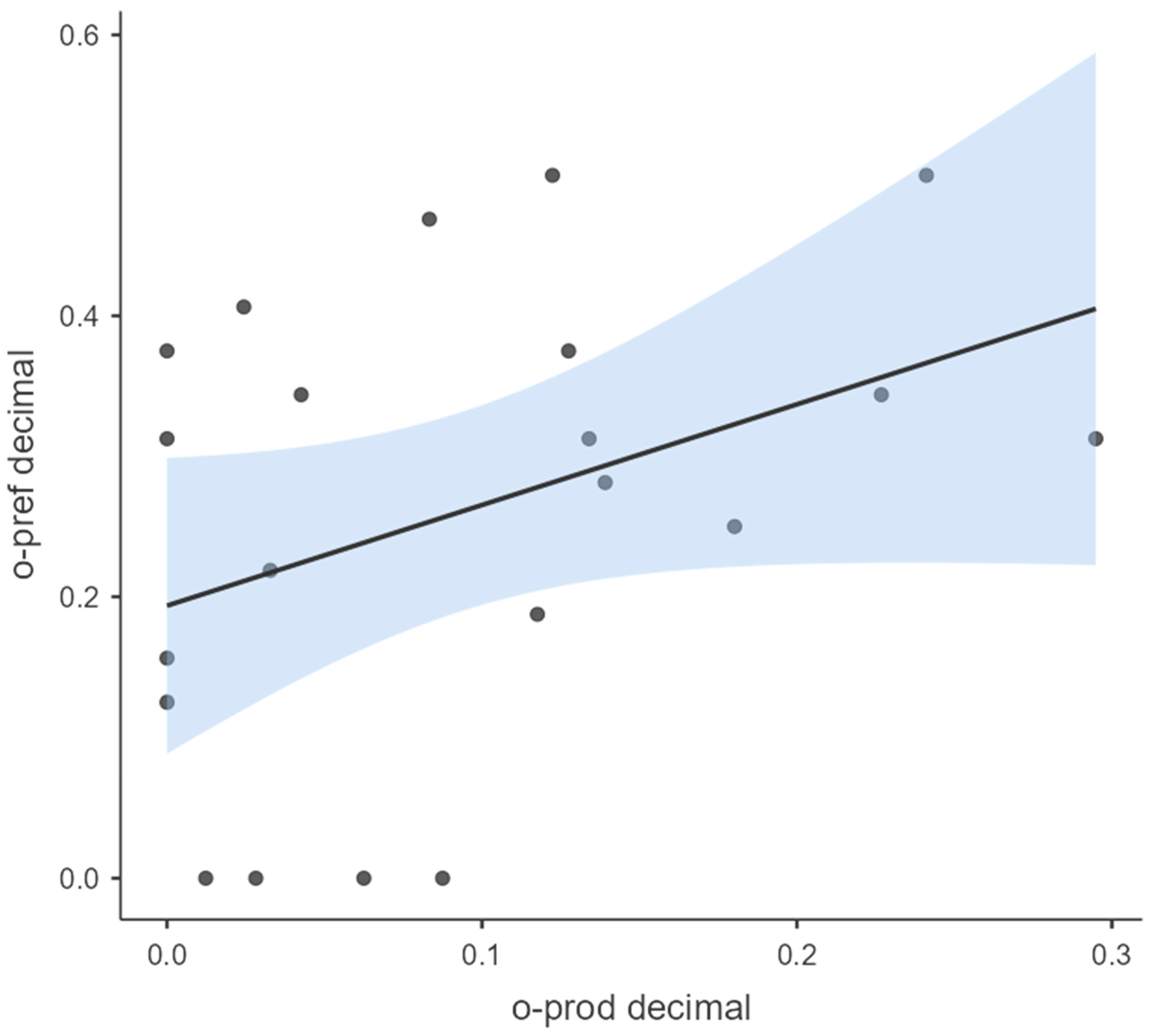

Learners with higher rates of production of deletion tended to also have higher rates of selection, although there was no significant correlation between production and selection of deletion, r(19) = 0.38 [95% CI: −0.06, 0.70], p = 0.088 (see Figure 7). For instance, the aforementioned Tiff, Steph, and Lainey, who most produced deleted /d/, selected deletion in 31.25%, 50.00%, and 34.38% of contexts, respectively, which were among the higher rates of selection but only one of these was at the highest rates, with another learner (Mark) also selecting the deleted variant at a rate of 50% and a pair of other learners with rates above 40%. Mark exhibited deletion in production at a rate of 12.24%, and the two other learners with selection rates above 40% also had lower production rates (Maddie, at only 2.44% deleted /d/ in production, and Lauren at 8.33%; see again Figure 5 for production), helping to further exemplify why production and selection did not significantly correlate. It is worth noting that these two learners with disparate production and preference rates were not among those with the most study abroad experience (Lauren, at only 0.75 months, and Maddie, a bit more in the middle of the group at 10 months).

Figure 7.

Scatterplot of individual participants by rate of production and rate of selection of deletion.

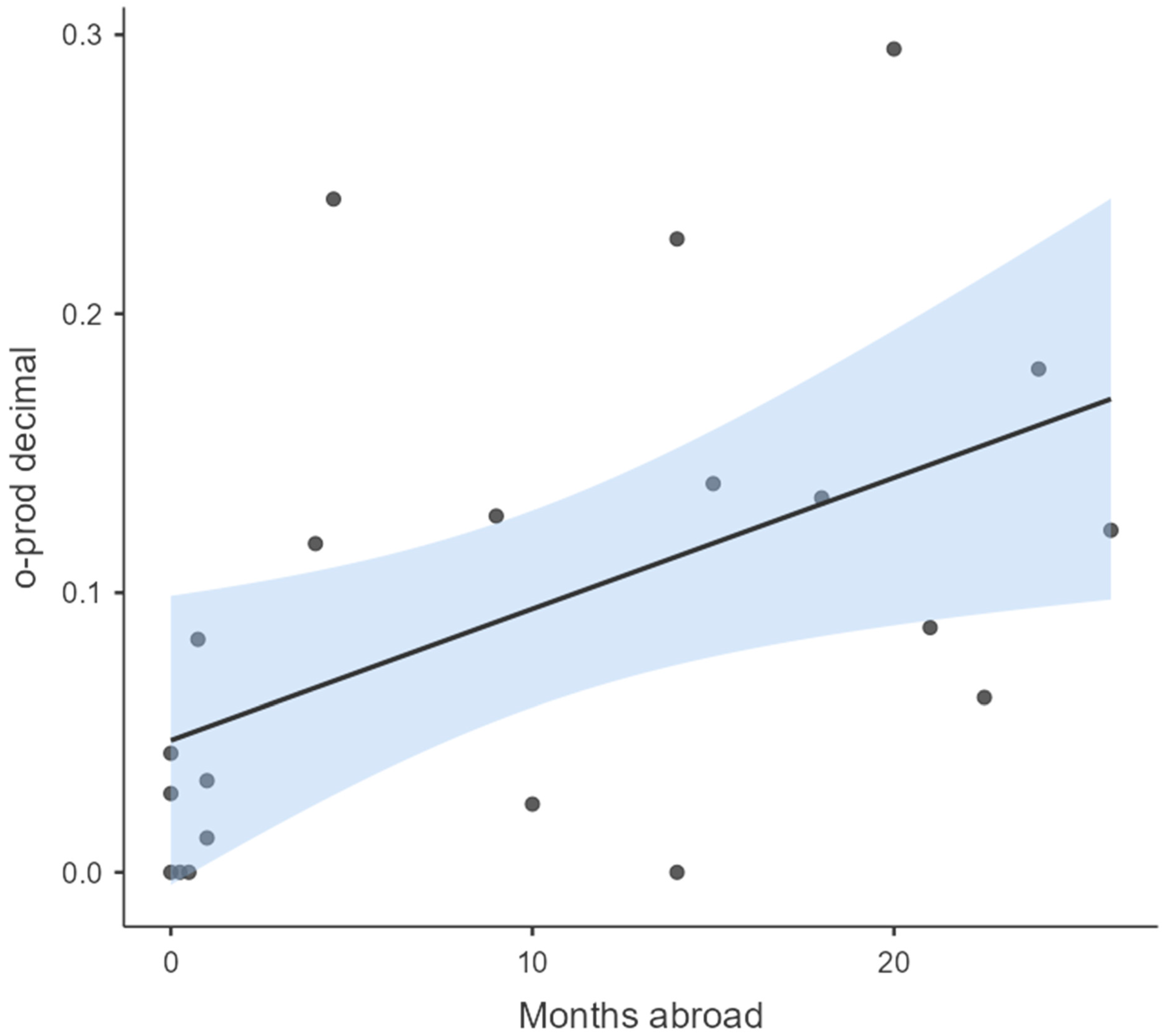

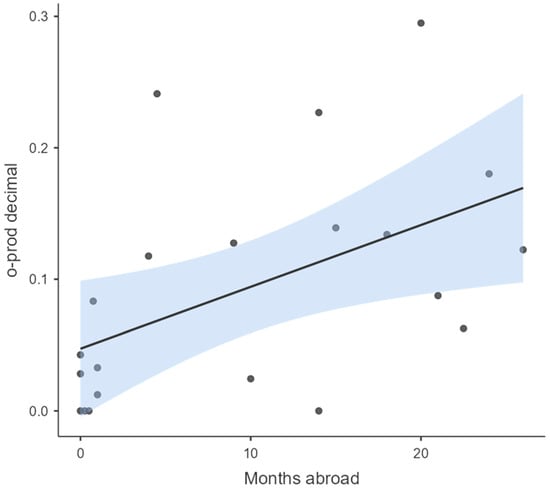

With respect to experience abroad, there was a significant, positive correlation between production of deleted /d/ and months spent abroad, r(19) = 0.51 [95% CI: 0.09, 0.77], p = 0.020. This is supported, for instance, by the learners with little to no abroad experience who did not produce deletion or who did so at very low rates (see Table 6 and lower left corner of Figure 8). In fact, learners with less experience abroad tended to be those with the lower EIT scores and with very low rates of deleted /d/: Jen, Anna, Emma, Kara, and Jeff (though Jeff’s EIT score was rather higher than the others). Of course, despite the correlation between time abroad and production of deleted /d/, some of the learners with the longer stays abroad (Ty (22.5 months) and Kenzie (21 months)) showed low rates of production of deleted /d/.2

Figure 8.

Scatterplot of individual participants by months abroad and rate of production of deletion.

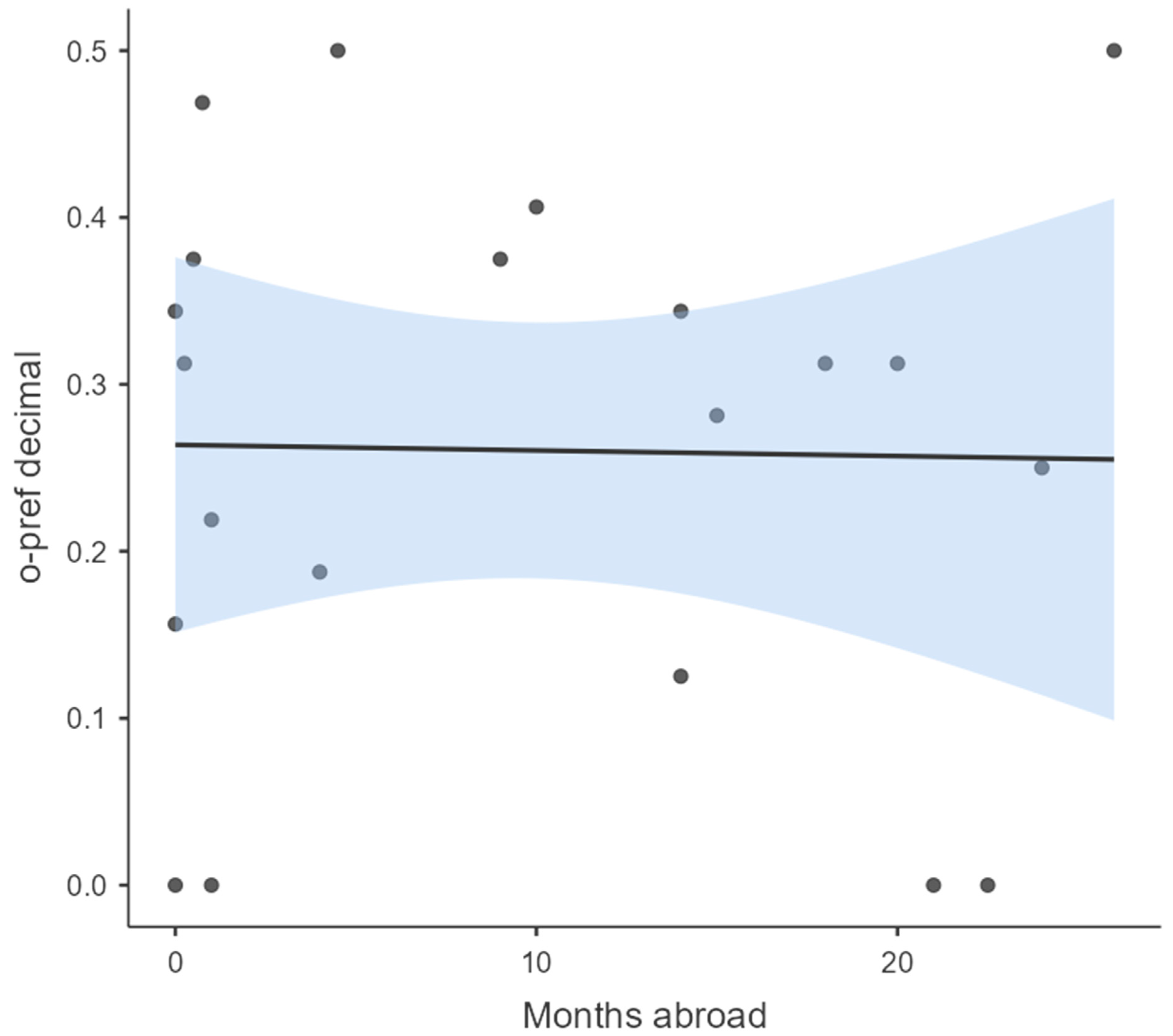

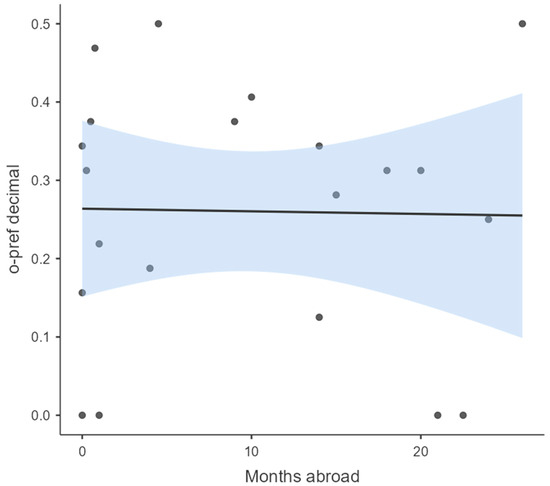

Unlike production and time abroad, selection and time abroad did not correlate (and actually showed a negative, albeit nonsignificant, relationship), r(19) = −0.19 [95% CI: −0.45, 0.42], p = 0.934 (see Figure 9). The lack of relationship between months abroad and rate of selection of deletion is exemplified in a few individual cases. For instance, Mark, who was among the highest choosers of deletion, at 50%, was the learner who had spent the greatest amount of time abroad (26 months), whereas Steph, the other learner who selected deletion at 50%, had relatively limited experience abroad (4.5 months). On the other end of the spectrum, some learners with little to no experience abroad selected deletion upwards of 30% of the time (e.g., Jen, Kara, Stacy), and the aforementioned longer sojourners—Ty and Kenzie (both above 20 months)—showed zero preference for deleted /d/.3

Figure 9.

Scatterplot of individual participants by months abroad and rate of selection of deletion.

5. Discussion

The overarching goal for the present study was to explore and elucidate the potential link between L2 perception of a sociolinguistic variant and the production of that variant by the same L2 learners. The results of the study suggest some indication of awareness of intervocalic /d/ variation in Spanish by L2 learners prior to the appearance of a deleted /d/ in production. In the present study, four of the five least proficient learners selected a deleted /d/ at least occasionally in the preference task even though they did not produce it at all. Likewise, most learners exhibited higher rates of selection of /d/ deletion than production of a deleted variant. These results echo Escalante’s (2018a) findings of perceptual knowledge of Spanish /s/ weakening among her learners without concomitant production of this phenomenon. Nevertheless, rate of selection of /d/ deletion was not a significant predictor of production of a deleted /d/ (and was thus not included in the best-fit regression model reported in Table 5). There were also four different learners who exhibited some deletion in their production task despite never selecting a deleted variant in the preference task. As such, the present results cannot point to a concrete perception/selection threshold that precedes production. Still, learner awareness of /d/ deletion appears to generally precede deletion of /d/, which is also predicted by learner language proficiency and correlated with time spent abroad. Scatterplots and individual analyses helped reveal that, among our learners, only those with EIT scores at or above 109 produced deletion at or above 8.75% of the time.

Similar to the preference task data in Solon and Kanwit (2022), the linguistic factors of preceding vowel, grammatical category, and lexical frequency influenced learner production patterns of /d/ in largely expected directions. Interestingly, frequency was a significant predictor of the production of a deleted variant in the present study (similar to Solon et al., 2018, where frequency was the most influential factor for learners’ /d/ deletion patterns), even though frequency did not significantly constrain learners’ selection of a deleted versus a realized /d/ in the preference task (Solon & Kanwit, 2022). These findings not only point to potential important differences in the development of perceptual and productive knowledge and abilities as related to sociophonetic variation but also to the importance of eliciting different types of data. Understanding the development of a L2 sociolinguistic repertoire requires data that examine numerous aspects of learners’ understanding, abilities, patterns, and environment. By recognizing the value of broad and numerous research tools and the limitations of each, we can better paint a picture of L2 learners’ sociolinguistic systems and how they develop.

It is important, thus, to recognize some of the limitations of the present study to better contextualize what can be taken away from the present results and what provides motivation for future investigation. Most notably, although the present study’s comparison of preference and production data provides unique insight into the potential relationship between these two components of sociophonetic knowledge, we want to acknowledge that the two types of data do not represent ideal comparison partners. First, selecting a deleted variant uttered by another speaker is a different process than producing a deleted /d/ in one’s own speech, especially if /d/ deletion indexes social information related to prestige or social class (e.g., Alba, 1999; Díaz-Campos et al., 2011; D’Introno & Sosa, 1986; Uruburu Bidaurrázaga, 1994). Future research that explores what /d/ deletion means to L2 speakers will offer additional insight into the relationship between perception and production. Subsequent work could thus make connections between social meanings that learners associate with /d/ deletion and the ways in which learners act as agents in choosing or using deleted /d/ to express affiliation with particular groups or to assert relevant aspects of their identities (for instance, see Grammon, 2024 for connections among social meaning, language attitudes and ideologies, and L2 usage of morphosyntactic features of Cuzco Spanish). Second, given the extensive control of the preference task and the relative open-endedness of the production task, we would not necessarily expect rates of selection to mirror rates of production, and differences observed therein can be due not just to differences in the development of these types of knowledge/abilities but also to differences between the tasks. Thus, we encourage caution in the interpretation of the higher rates of selection than production as conclusive evidence that perceptual abilities precede productive ones; higher rates are likely also influenced by the fact that in the preference task, learners must select one of only two choices on any particular task item.

We stand by the novelty and contribution of the preference task for the different perspective it can offer regarding learners’ sociophonetic knowledge. Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge that, given the preference task’s design, we have no information about how learners are categorizing a deleted /d/ (even when they do select it). Likewise, we did not collect information regarding learners’ knowledge of the lexical items into which the /d/ tokens were embedded. Given that participants in Solon and Kanwit (2022) were making decisions on a small number of lexical items (32), the specific properties of just one of those words (or participants’ (lack of) knowledge or understanding of a particular lexical item) may impact the results in an outsized way.

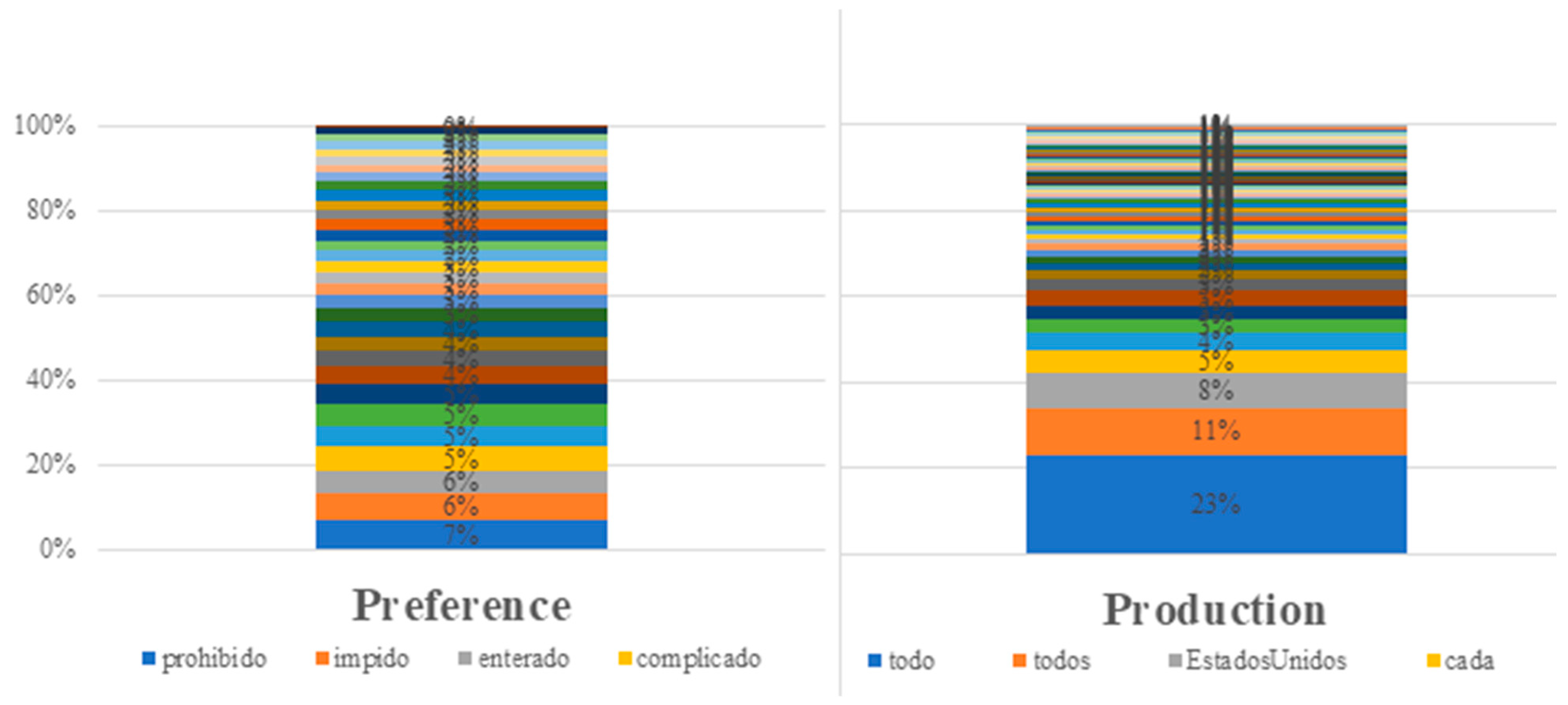

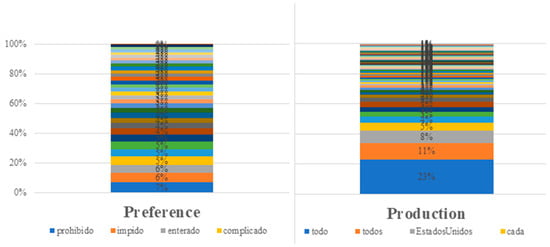

Still, we argue that these differences between tasks are important and may, in fact, help clue us into mechanisms for learning as long as we recognize, acknowledge, and account for how such differences affect the data collected. For example, if we return to the different findings related to the role of frequency between the preference and the production data, considering the differences between the two tasks can reveal important paths of influence for the factors explored. The preference task carefully controlled the lexical items used, ensuring that half were “high frequency” and the other half “low frequency”. The production data included no such control, and categorization of words by frequency was post hoc. Thus, if we explore which specific lexical items exhibited deletion most often (in both the selection and production tasks, see Figure 10), we can see that whereas for the preference data, deletion is spread across numerous tokens included in the task, in the production data, the lexical items todo and todos “all” constitute 34% of all deleted tokens.

Figure 10.

Percentage of deleted tokens constituted by certain lexical items by task; each color/bar represents a distinct lexical item. Only the four most deleted lexical items for each task are included in the legend to illustrate the differences in distribution across the tasks.

Given that todo and todos are frequent lexical items, it may be that the effect of frequency is led by a small number of certain very frequent items rather than the property of frequency as an abstract whole.4 This pattern, which warrants future investigation, is thus revealed by carefully considering, comparing, and exploring the differences between data types and the findings that are drawn from them.

6. Conclusions

The present study explored sociophonetic competence, a component of sociolinguistic and, thus, communicative competence (Canale & Swain, 1980; Geeslin et al., 2018; Kanwit & Solon, 2023). Whereas our predecessors have explored sociophonetic competence in learner production (Geeslin & Gudmestad, 2008; Kennedy Terry, 2017; Raish, 2015) or perception (Chappell & Kanwit, 2022; Schmidt, 2018), these abilities have typically been explored separately. This study aimed to explore production and perception of sociophonetic variation by the same learners so as to illuminate the relationship between learners’ ability to account for sociophonetic variability in the input and their likelihood to produce such variation in output. Despite limitations in the tasks employed and their comparison, the present findings reveal important trends regarding sociophonetic development. Overall, this study’s findings suggest that learner perceptual knowledge of a sociophonetic variant (as tracked via preference in the present study) tends to precede productive use of that variant in speech. As the learners’ L2 proficiency increases, so too do general rates of selection and production of the variant in question. Nevertheless, in addition to these overall group patterns observed, the present data revealed substantial individual variation, with some highly proficient learners exhibiting sociophonetic knowledge on the preference task but never producing such variation in their own speech. Despite limitations, these findings offer one of few side-by-side comparisons of learners’ sociolinguistic perception and production data and, thus, contribute to our understanding of sociophonetic competence and its development in a L2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.; methodology, M.S. and M.K.; software, M.K. and M.S.; formal analysis, M.S. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and M.K.; visualization, M.K. and M.S.; project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University at Albany, SUNY (protocol 17-X-029-01, approved 17 February 2017)

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/guesb/, accessed on 10 December 2024.

Acknowledgments

This project was heavily inspired by the research and mentoring of Kimberly Geeslin, who first motivated our interest in sociolinguistic competence. She is truly missed. We are grateful to four anonymous reviewers and special issue editors Vera Regan and Kristen Kennedy Terry for their useful feedback, which strengthened the manuscript. All errors are ours alone.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Sample prompt from the production task.

Translation of sample prompt:

- (1)

- You are in an airport waiting for a plane. A person sits beside you and begins to speak with you. (S)he is from the Dominican Republic and doesn’t know much about university life in the United States. You tell him/her about your daily life and your impressions of university life according to your current experience.

- Describe your daily life or what you do routinely.

- What do you do on weekends?

- What do you think of the university? What do you like? What don’t you like?

- What do professors expect from students?

- What do students expect from professors?

- In general, what worries do university students have?

- What doubts do they have with respect to university life?

- How do you feel at the beginning of a semester?

- How do you feel at the end of a semester?

Notes

| 1 | Although months abroad was not a significant predictor of deletion for our 17 non-categorical learners in the mixed-effects regression (p = 0.065 when considered with the other predictors of the otherwise best-fit model), we will see that it did reveal a significant correlation with deletion in our Pearson test of all 21 learners in Section 4.2. (The correlation was also significant if the sample was limited to the subset of 17 learners.) That time abroad approached but did not achieve significance in the regression likely relates to a combination of causes, including the relatively small number of participants, the high level of individual variability and the role of the individual as a random effect, and the greater predictiveness of EIT score, which, as we will see in Section 4.2, correlated with time abroad. Recall, nevertheless, that time abroad and EIT score did not significantly interact in the regression, as no interactions were significant. |

| 2 | As previously mentioned, although we collected data on learners’ study abroad destinations, we considered time abroad holistically in the present study. Future examination of the role of time abroad in specific contexts (e.g., to regions where the variable phenomenon is known to be prevalent versus those where it is not) will provide further insight into the role of this experiential predictor. |

| 3 | Although we foreground correlations that included rates of production and/or selection of deleted /d/ in the current section, we performed one other Spearman test for the characteristics mentioned in the section. The test for EIT score and months abroad revealed a significant, positive correlation, r(19) = 0.54 [95% CI: 0.14, 0.79], p = 0.012. This supports patterns that can be gleaned from Table 3 and Table 5: learners with higher EIT scores had generally spent longer periods abroad. |

| 4 | Nevertheless, recall that the individual lexical item was entered as a random effect in the current and prior study’s regression models, which helps to not overly attribute the role of certain categories of predictors (e.g., high frequency, preceding -o as vowel) to (a) particular lexical item(s) (see Chapter 5 of Tagliamonte, 2012). |

References

- Adamson, D., & Regan, V. (1991). The acquisition of community speech norms by Asian immigrants learning English as a second language: A preliminary study. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, O. (1999). Elisión de la/d/intervocálica postónica en el español dominicano. In A. Morales, J. Cardona, H. López Morales, & E. Forastieri (Eds.), Estudios de la lingüística hispánica (pp. 3–21). Homenaje a María Vaquero. [Google Scholar]

- Alvord, S. M., & Christiansen, D. E. (2012). Factors influencing the acquisition of Spanish voiced stop spirantization during an extended stay abroad. Studies in Hispanic and Lusophone Linguistics, 5, 239–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, W., & Smith, L. (2010). The impact of L2 dialect on L2 learning: Leaning Quebecois versus European French. Canadian Modern Language Review, 66, 711–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedinghaus, R., & Sedó, B. (2014). Intervocalic/d/deletion in Málaga: Frequency effects and linguistic factors. IULC Working Papers, 14(2), 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- Blas Arroyo, J. L. (2006). Hasta aquí hemos llega(d)o: ¿Un caso de variación morfológica? Factores estructurales y estilísticos en el español. Southwest Journal of Linguistics, 25(2), 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden, H. W. (2016). Assessing second-language oral proficiency for research: The Spanish elicited imitation task. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 38, 647–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied Linguistics, 1, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravedo, R. (1990). Sociolingüística del español de Lima. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. [Google Scholar]

- Cedergren, H. (1973). The interplay of social and linguistic factors in Panama [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Cornell University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell, W., & Kanwit, M. (2022). Do learners connect sociophonetic variation with regional and social characteristics? The case of L2 perception of Spanish aspiration. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalola, A., & Bullock, B. E. (2017). On sociophonetic competence: Phrase-final vowel devoicing in native and advanced L2 speakers of French. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 39, 769–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. (2016). Corpus del español: Web/Dialects. Available online: http://www.corpusdelespanol.org/web-dial/ (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- Del Saz, M. (2019). Native and nonnative perception of western Andalusian Spanish/s/aspiration in quiet and noise. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41(4), 673–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Introno, F., & Sosa, J. M. (1986). Elisión de la/d/en el español de Caracas: Aspectos sociolingüísticos e implicaciones teóricas. In R. Núñez Cedeño, I. Páez, & J. Guitart (Eds.), Estudios sobre la fonología de español del caribe (pp. 135–163). Casa de Bello. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, M., & Gradoville, M. (2011). An analysis of frequency as a factor contributing to the diffusion of variable phenomena: Evidence from Spanish data. In L. A. Ortiz-López (Ed.), Selected proceedings of the 13th hispanic linguistics symposium (pp. 224–238). Cascadilla. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Campos, M., Fafulas, S., & Gradoville, M. (2011). Going retro: An analysis of the interplay between socioeconomic class and age in Caracas Spanish. In J. Michnowicz, & R. Dodsworth (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 5th workshop on Spanish sociolinguistics (pp. 65–78). Cascadilla. [Google Scholar]

- Erker, D., & Guy, G. R. (2012). The role of lexical frequency in syntactic variability: Variable subject personal pronoun expression in Spanish. Language, 88, 526–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, C. (2018a). The acquisition of a sociolinguistic variable while volunteering abroad: S-weakening among L2 and heritage speakers in coastal Ecuador [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of California]. [Google Scholar]

- Escalante, C. (2018b). ¡ Ya pué [h]! Perception of coda-/s/weakening among L2 and heritage speakers in coastal Ecuador. EuroAmerican Journal of Applied Linguistics and Languages, 5(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalante, C. (2021). Individual differences in dialectal accommodation: Case studies of heritage speakers volunteering in coastal Ecuador. In R. Pozzi, T. Quan, & C. Escalante (Eds.), Heritage speakers of Spanish and study abroad (pp. 77–97). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Face, T. L., & Menke, M. R. (2009). Acquisition of the Spanish voiced spirants by second language learners. In J. Collentine, M. García, B. Lafford, & F. Marcos Marín (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 11th hispanic linguistics symposium (pp. 39–52). Cascadilla. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K. L., & Gudmestad, A. (2008). The acquisition of variation in second-language Spanish: An agenda for integrating studies of the L2 sound system. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 5(2), 137–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geeslin, K. L., & Long, A. Y. (2014). Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition: Learning to use language in context. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K. L., & Schmidt, L. B. (2018). Study abroad and L2 learner attitudes. In C. Sanz, & A. Morales-Front (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of study abroad research and practice (pp. 387–405). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Geeslin, K. L., Gudmestad, A., Kanwit, M., Linford, B., Long, A. Y., Schmidt, L., & Solon, M. (2018). Sociolinguistic competence and the acquisition of speaking. In M. R. Alonso Alonso (Ed.), Speaking in a second language (pp. 1–25). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- George, A. (2014). Study abroad in Central Spain: The development of regional phonological features. Foreign Language Annals, 47, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammon, D. (2024). Ideology, indexicality, and the second language development of sociolinguistic perception during study abroad. L2 Journal, 16(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Campoy, J. M., & Jiménez-Cano, J. M. (2003). Broadcasting standardisation: An análisis of the linguistic normalization process in Murcian Spanish. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 7(3), 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M., Lemée, I., & Regan, V. (2006). The L2 acquisition of a phonological variable: The case of/l/deletion in French. Journal of French Language Studies, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwit, M., & Solon, M. (Eds.). (2023). Communicative competence in a second language: Theory, method, and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Terry, K. (2017). Contact, context, and collocation: The emergence of sociostylistic variation in L2 French learners during study abroad. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 39, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy Terry, K. (2022). Sociolinguistic variation in L2 French: What schwa deletion patterns reveal about language acquisition during study abroad. In R. Bayley, D. R. Preston, & X. Li (Eds.), Variation in second and heritage languages: Crosslinguistic perspectives (pp. 279–310). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Knouse, S. M. (2012). The acquisition of dialectal phonemes in a study abroad context: The case of the Castilian theta. Foreign Language Annals, 45, 512–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, G. (2010). The combined effects of immersion and instruction on second language pronunciation. Foreign Language Annals, 43, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Morales, H. (1983). Estratificación social del español de San Juan de Puerto Rico. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Moya Corral, J. A., & García Wiedemann, E. J. (2009). La elisión de/d/intervocálica en el español culto de Granada: Factores lingüísticos. Pragmalingüística, 17, 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, C. L., & Baese-Berk, M. M. (2022). Advancing the state of the art in L2 speech perception-production research: Revisiting theoretical assumptions and methodological practices. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 44(2), 580–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, L., Iwashita, N., Norris, J. M., & Rabie, S. ((2002,, October 3–6). An investigation of elicited imitation tasks in crosslinguistic SLA research. Second Language Research Forum, Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Pfenninger, S. E., & Festman, J. (2021). Psycholinguistics. In T. Gregerson, & S. Mercer (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of the psychology of language learning and teaching (pp. 74–86). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, J. (2023). Individual differences in the adoption of dialectal features during study abroad. In S. Zahler, A. Y. Long, & B. Linford (Eds.), Study abroad and the second language acquisition of sociolinguistic variation in Spanish (pp. 147–173). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, R. (2022). Acquiring sociolinguistic competence during study abroad: U.S. students in Buenos Aires. In R. Bayley, D. R. Preston, & X. Li (Eds.), Variation in second and heritage languages: Crosslinguistic perspectives (pp. 199–222). John Benjamins. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi, R., & Bayley, R. (2021). The development of a regional phonological feature during a semester abroad in Argentina. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 43, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raish, M. (2015). The acquisition of an Egyptian phonological variant by U.S. students in Cairo. Foreign Language Annals, 48, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, V., Howard, M., & Lemée, I. (2009). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence in a study abroad context. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Rehner, K. (2002). The development of aspects of linguistic and discourse competence by advanced second language learners of French [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto]. [Google Scholar]

- Ringer-Hilfinger, K. (2012). Learner acquisition of dialect variation in a study abroad context: The case of the Spanish [θ]. Foreign Language Annals, 45, 430–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper Padilla, J. A. (1990). Estudio sociolingüístico del español de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. Imprenta Pérez Galdós. [Google Scholar]

- Samper, & Padilla, J. A. (1996). El debilitamiento de-/d/-en la norma culta de las Palmas de Gran Canaria. In M. Arjona Iglesias, J. López Chávez, A. Enríquez Ovando, G. C. López Lara, & M. A. Novella Gómez (Eds.), Actas del X Congreso Internacional de la Asociación de Lingüística y Filología de la América Latina (pp. 791–796). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L. B. (2009). The effect of dialect familiarity via a study abroad experience on L2 comprehension of Spanish. In J. Collentine, M. García, B. Lafford, & F. M. Marín (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 11th hispanic linguistics symposium (pp. 143–154). Cascadilla Proceedings Project. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, L. B. (2018). L2 development of perceptual categorization of dialectal sounds: A study in Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40, 847–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L. B. (2022). L2 development of dialect awareness in Spanish. Hispania, 105(2), 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L. B., & Geeslin, K. L. (2022). Acquisition of linguistic competence: Development of sociolinguistic evaluations of regional varieties in a second language. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada/Spanish Journal of Applied Linguistics, 35(1), 206–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonmaker-Gates, E. (2017). Regional variation in the language classroom and beyond: Mapping learners’ developing dialectal competence. Foreign Language Annals, 50, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. C., & Baker, W. (2011). L2 dialect acquisition of German vowels: The case of Northern German and Austrian dialects. Poznán Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 47, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, M., & Kanwit, M. (2022). New methods for tracking development of sociophonetic competence: Exploring a preference task for Spanish/d/deletion. Applied Linguistics, 43(4), 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, M., Linford, B., & Geeslin, K. L. (2018). Acquisition of sociophonetic variation: Intervocalic/d/reduction in native and non-native Spanish. Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 31(1), 309–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solon, M., Park, H., Henderson, C., & Dehghan-Chaleshtori, M. (2019). Revisiting the Spanish elicited imitation task: A tool for assessing advanced language learners? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41, 1027–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, S. A. (2012). Variationist sociolinguistics: Change, observation, interpretation. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Trimble, J. C. (2014). The intelligibility of Spanish dialects from the L2 learner’s perspective: The importance of phonological variation and dialect familiarity. International Journal of the Linguistic Association of the Southwest, 33(2), 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- Uritescu, D., Mougeon, R., & Handouleh, Y. (2002). Le comportement du schwa dans le français parlé par les élèves des programmes d’immersion française. In C. Tatilon, & A. Baudot (Eds.), La Linguistique fonctionnelle au tournant du siècle. Actes du Vingt-quatrième Colloque international de linguistique fonctionnelle (pp. 335–346). Éditions du GREF. [Google Scholar]

- Uruburu Bidaurrázaga, A. (1994). El tratamiento del fonema/a/en posición intervocálica en la lengua hablada en Córdoba (España). La Linguistique, 30, 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Zampini, M. (1994). The role of native language transfer and task formality in the acquisition of Spanish spirantization. Hispania, 77, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).