Number Morphology and Bare Nouns in Some Romance Dialects of Italy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| (1) | a. | J’ai | vu | *(des) | étudiants | dans | l’ | édifice |

| I have | seen | of.the.pl | student | in | the.sg | building | ||

| ‘I saw students in the building’ | ||||||||

| b. | Jean | a | bu | *(de l’) | eau | |||

| Jean | has | drunk | of | the.sg water | ||||

| ‘Jean drunk water’ | ||||||||

| (2) | Italian |

| a. student-e | |

| student-m.sg | |

| b. student-i | |

| student-m.pl |

| (3) | Spanish |

| a. estudiant-e | |

| student-wm | |

| b. estudiant-e-s | |

| student-wm-pl |

- (a)

- languages where there is regular/systematic number exponence on nouns have bare nouns;

- (b)

- the absence of suffixes on nouns seems to correlate with the absence of argument bare nouns.

2. The Dataset

| (4) | a. | six “Gallo-Italic”8 dialects of northern Italy (Lombardia: Casalmaggiore;9 Emilia: Parma,10 Reggio Emilia,11 Novellara,12 Correggio;13 Romagna: Savignano sul Rubicone)14 |

| b. | ten “upper” southern dialects (Abruzzo: Teramo;15 Campania: Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Amalfi and Palma Campania;16 Cilento: Felitto;17 Puglia: Bari,18 Barletta,19 Taranto;20 Lausberg area: Francavilla in Sinni,21 Verbicaro)22 | |

| c. | twelve “extreme” southern dialects (Salento:23 Cellino San Marco, Mesagne, Botrugno; Calabria:24 Cutro,25 Nicastro,26 Catanzaro,27 Reggio Calabria;28 Sicily:29 San Filippo del Mela, Ragusa, Ribera, Mussomeli, Trapani) | |

| d. | one “Gallo-Italic”30 dialect of Sicily (Aidone) |

| (5) | a. | nu | kwatrarə | bbjeddə |

| a.m | boy | beautiful | ||

| ‘a beautiful boy’ | ||||

| b. | na | kwatrara | bbɛdda | |

| a.f | girl.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | ||

| ‘a beautiful girl’ | ||||

| c. | tʃɛrtə | kwatrarə | bbjeddə | |

| some | boy | beautiful | ||

| ‘some beautiful girls/boys’ | ||||

| (6) | a. | u | ddibbrə | nuvə |

| the.m.sg | book | new | ||

| ‘the new book’ | ||||

| b. | i | ddibbrə | nuvə | |

| the.pl | book | new | ||

| ‘the new books’ | ||||

| (7) | a. | a | kasa | nuva |

| the.f.sg | house.f.sg | new.f.sg | ||

| ‘the new house | ||||

| b. | i | kasə | nuvə | |

| the.pl | house | new | ||

| ‘the new houses’ | ||||

| (8) | a. | vasə | kiss.sg | vs. | visə | kiss.pl | |

| b. | nasə | nose.sg | vs. | nisə | nose.pl |

| (9) | a. | Ferrara | spoz | groom.sg | vs. | spuz | groom.pl |

| b. | Bologna | bon | good.sg | vs. | bun | good.pl | |

| pa | foot.sg | vs. | pi | foot.pl | |||

| an | year.sg | vs. | en | year.pl | |||

| gras | fat.sg | vs. | gres | fat.pl | |||

| Fusignano (Badini 2002, p. 381) | kan | dog.sg | vs. | ken | dog.pl |

| (10) | singular | plural | meaning | ||

| a. | bikir | bikir | glass | ||

| b. | i. | fnestra | fnestri | window | |

| ii. | kriatura | kriatur | person | ||

| c. | i. | lamp | lɛmp | lightning | |

| ii. | kapɛl | kapel | hat | ||

| iii. | kapɔt | kapot | coat | ||

| iv. | fjor | fjur | flower |

3. Number in Nominal Structures

3.1. Number in DPs

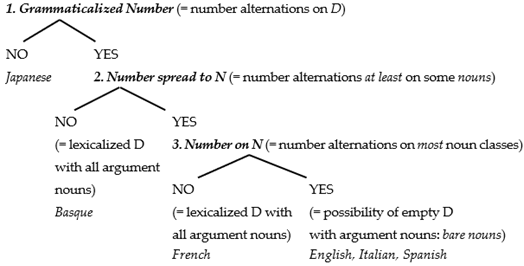

| (11) | Grammaticalized Number (adapted from Crisma et al. 2020) |

| a. Nominal arguments display bound morpheme alternations (on the head noun and/or on a definite article/demonstrative/quantifier/adjective) that oppose singular to non-singular interpretation. | |

| b. There is agreement in number between a singular/non-singular nominal argument and the verb. | |

| c. There is agreement in number between a singular/non-singular noun (or a definite article/demonstrative/quantifier) and adjectives (within the same nominal structure). | |

| d. There is agreement in number between a 3rd person reflexive and its antecedent. |

| (12) | Number in DPs: three parameters |

|

3.2. Parameter Manifestations in the Dialect Dataset

| (13) | Casalmaggiore (Vezzosi 2019, p. 26) | |||||||

| a. | la | bɛla | ragasa | l | ɛ | andada | via | |

| the.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | girl.f.sg | subj.cl | be.3 | gone.f.sg | away | ||

| ‘The beautiful girl has left’ | ||||||||

| b. | li | bɛli | ragasi | li | ɛ | andadi | via | |

| the.f.pl | beautiful.f.pl | girl.f.pl | subj.cl | be.3 | gone.f.pl | away | ||

| ‘The beautiful girls have left’ | ||||||||

| (14) | Teramo (Mantenuto 2015a, pp. 2–3) | |||||

| a. | lu | kanə | roʃʃə | ɛ | bbellə | |

| the.m.sg | dog.m.sg | red.m.sg | be.3sg | beautiful.m.sg | ||

| ‘The red dog is beautiful’ | ||||||

| b. | li | kinə | ruʃʃə | so | bbillə | |

| the.m.pl | dog.m.pl | red.m.pl | be.3pl | beautiful.m.pl | ||

| ‘The red dogs are beautiful’ | ||||||

| (15) | Santa Maria Capua Vetere | |||||

| a. | o | waʎʎonə | roʃə | a | partutə | |

| the.m.sg | young person.m.sg | sweet.m.sg | have.3sg | left | ||

| ‘The sweet boy has left’ | ||||||

| b. | e | waʎʎunə | ruʃə | annə | partutə | |

| the.m.pl | young person.m.pl | sweet.m.pl | have.3pl | left | ||

| ‘The sweet boys have left’ | ||||||

| (16) | Trapani | ||||||||

| a. | u | pittʃottu | mirikanu | paittiu | |||||

| the.m.sg | young person.m.sg | American.m.sg | leave.3sg.past | ||||||

| ‘The American boy has left’ | |||||||||

| b. | i | pittʃotti | mirikani | paitteru | |||||

| the.pl | young person.pl | American.pl | leave.3pl.past | ||||||

| ‘The American boys/girls left’ | |||||||||

| (17) | Reggio Calabria | ||||||||

| a. | lu | figgjɔlu | mirikanu | partiu | |||||

| the.m.sg | young person.m.sg | American.m.sg | leave.3sg.past | ||||||

| ‘The American boy has left’ | |||||||||

| b. | i | figgjɔli | mirikani | partɛru | |||||

| the.pl | young person.pl | American.pl | leave.3pl.past | ||||||

| ‘The American boys/girls left’ | |||||||||

| (18) | Cellino San Marco | ||||||||

| a. | lu | kane | bjanku | se | fatʃe | sempre | kkju | jɛrtu | |

| the.m.sg | dog.sg | white.m.sg | SI | do.3sg | always | more | tall.m.sg | ||

| ‘The white dog is becoming increasingly taller’ | |||||||||

| b. | li | kani | bjanki | se | fannu | sempre | kkju | jɛrti | |

| the.pl | dog.pl | white.m.pl | SI | do.3pl | always | more | tall.pl | ||

| ‘The white dogs are becoming increasingly taller’ | |||||||||

| (19) | Aidone | |||||

| a. | i. | vinnə | na | pəttʃidda | səmpatəka | |

| come.3sg.past | a.f | child.f.sg | nice.f.sg | |||

| ‘A nice girl came’ | ||||||

| ii. | vinnə | nu | pəttʃiddə | səmpatəkə | ||

| come.3sg.past | a.m | child | nice | |||

| ‘A nice boy came’ | ||||||

| b. | vinnərə | (tʃɛrtə) | pəttʃiddə | səmpatəkə | ||

| come.3pl.past | some | child | nice | |||

| ‘Some nice girls/boys came’ | ||||||

3.3. Morphological Exponence of Number in the Dataset

3.3.1. Nouns (and Adjectives)

| (20) | Reggio Calabria (adapted from Falcone 1976, p. 68) | |||

| a. | u | mulu | bbɔnu | |

| the.m.sg | mule.m.sg | good.m.sg | ||

| ‘the mule of good quality’ | ||||

| b. | i | muli | bbɔni | |

| the.pl | mule.pl | good.pl | ||

| ‘the mules of good quality’ | ||||

| (21) | San Filippo Del Mela | |||

| a. | a | figgjɔla | mirikana | |

| the.f.sg | young person.f.sg | American.f.sg | ||

| ‘the American girl’ | ||||

| b. | u | figgjɔlu | mirikanu | |

| the.m.sg | young person.m.sg | American.m.sg | ||

| ‘the American boy’ | ||||

| c. | i | figgjɔli | mirikani | |

| the.pl | young person.pl | American.pl | ||

| ‘the American boys/girls’ | ||||

| (22) | Casalmaggiore (Vezzosi 2019, p. 26) | |||

| a. | i. | sotana | dʒalda | |

| gown.f.sg | yellow.f.sg | |||

| ‘yellow gown’ | ||||

| ii. | sotani | dʒaldi | ||

| gown.f.pl | yellow.f.pl | |||

| ‘yellow gowns’ | ||||

| b. | ragas | grand | ||

| boy | tall | |||

| ‘tall boy/s’ | ||||

| (23) | Verbicaro (adapted from Loporcaro and Silvestri 2015, p. 69) | ||||

| a. | i. | na | bbɛlla | kasa | |

| a.f | beautiful.f.sg | house.f.sg | |||

| ‘a beautiful house’ | |||||

| ii. | na | kasa | bbɛdda | ||

| a.f | house.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | |||

| ‘a beautiful house’ | |||||

| b. | i. | tʃɛrtə | bbɛllə | kasə | |

| some | beautiful.f.pl | house.pl | |||

| ‘some beautiful houses’ | |||||

| ii. | tʃɛrtə | kasə | bbɛddə | ||

| some | house.pl | beautiful.f.pl | |||

| ‘some beautiful houses’ | |||||

| c. | i. | nu | bbwellə54 | kwatrarə | |

| a.m | beautiful.m | young person | |||

| ‘a beautiful boy’ | |||||

| ii. | nu | kwatrarə | bbjeddə | ||

| a.m | young person | beautiful.m | |||

| ‘a beautiful boy’ | |||||

| d. | i. | na | bbɛlla | kwatrara | |

| a.f | beautiful.f.sg | young person.f.sg | |||

| ‘a beautiful girl’ | |||||

| ii. | na | kwatrara | bbɛdda | ||

| a.f | young person.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | |||

| ‘a beautiful girl’ | |||||

| e. | i. | tʃɛrtə | bbellə | kwatrarə | |

| some | beautiful | young person | |||

| ‘some beautiful boys/girls’ | |||||

| ii. | tʃɛrtə | kwatrarə | bbjeddə | ||

| some | young person | beautiful.m | |||

| ‘some beautiful boys/girls’ | |||||

| iii. | tʃɛrtə | kwatrarə | bbɛddə | ||

| some | young person | beautiful.f.pl | |||

| ‘some beautiful girls’ | |||||

| (24) | Aidone | ||||

| a. | i. | na | bbrava | karuza | |

| a.f | good.f.sg | young person.f.sg | |||

| ‘a good girl’ | |||||

| ii. | na | karuza | bbrava | ||

| a.f.sg | young person.f.sg | good.f.sg | |||

| ‘a good girl’ | |||||

| b. | i. | un | bravə | karuzə | |

| a.m | good | young person.sg | |||

| ‘a good guy’ | |||||

| ii. | un | karuzə | bbravə | ||

| a.m | young person.sg | good | |||

| ‘a good guy’ | |||||

| c. | i. | tʃɛrtə | bbravə | karuʒə | |

| some | good | young person.pl | |||

| ‘some good guys’ | |||||

| ii. | tʃɛrtə | karuʒə | bbravə | ||

| some | young person.pl | good | |||

| ‘some good guys’ | |||||

| (25) | Francavilla in Sinni | ||||

| a. | i. | a | makəna | bbellə | |

| the.f.sg | car.f.sg | beautiful | |||

| ‘the beautiful car’ | |||||

| ii. | i | makənə | bbellə | ||

| the.pl | car | beautiful | |||

| ‘the beautiful cars’ | |||||

| b. | i. | a | bbella57 | makənə | |

| the.f.sg | beautiful.f.sg | car | |||

| ‘the beautiful car’ | |||||

| ii. | i | bbellə | makənə | ||

| the.pl | beautiful | car | |||

| ‘the beautiful cars’ | |||||

| c. | i. | u | pallonə | bbellə | |

| the.m.sg | ball.sg | beautiful | |||

| ‘the beautiful ball’ | |||||

| ii. | i | pallunə | bbellə | ||

| the.pl | ball.pl | beautiful | |||

| ‘the beautiful balls’ | |||||

| d. | i. | u | bbellə | pallonə | |

| the.m.sg | beautiful | ball.sg | |||

| ‘the beautiful ball’ | |||||

| ii. | i | bbellə | pallunə | ||

| the.pl | beautiful | ball.pl | |||

| ‘the beautiful balls’ | |||||

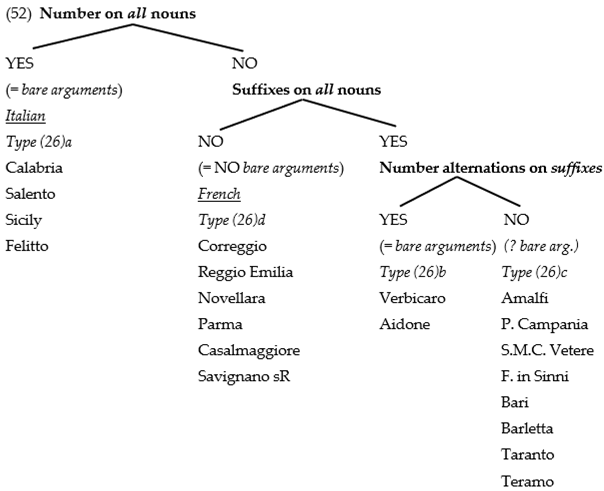

| (26) | a. | Languages where number distinctions are visible on suffixes on all noun classes as a rule (with spare lexical exceptions), and all noun classes have suffixes. The extreme southern dialects (group (4c)) belong to this type, as well as Felitto (4b). |

| b. | Languages (i.e., Verbicaro and Aidone) where number alternations are visible on suffixes only on one class (i.e., nouns originally ending in -A), and suffixes appear on all nouns. In these languages, the suffix -a encodes feminine gender and singular number; masculine nouns and plurals have the suffix -ə. | |

| c. | Languages where no number alternations are visible on suffixes, and suffixes appear on all nouns. In some nouns, number distinctions are realized through alternations of the stressed vowel. Dialects of group (4b), except for Felitto and Verbicaro, belong to this type. | |

| d. | Languages where suffixes encode number alternations only on a subset of nouns (i.e., those ending in -a/-al/-el), while the other nouns do not display any suffix. Dialects of group (4a) belong to this type. In some such dialects (e.g., Savignano sul Rubicone), number alternations are also realized through alternations of the stressed root vowel. |

3.3.2. Definite Articles

3.3.3. Demonstratives

| (27) | Casalmaggiore (adapted from Vezzosi 2019, p. 55) | |||||

| a. | kul | lebar | ke/le | |||

| dem.m.sg | book | here/there | ||||

| ‘this/that book’ | ||||||

| b. | ki | lebar | ke/le | |||

| dem.m.pl | book | here/there | ||||

| ‘these/those books’ | ||||||

| c. | kla | duna | ke/le | |||

| dem.f.sg | woman.f.sg | here/there | ||||

| ‘this/that woman’ | ||||||

| d. | kli | duni | ke/le | |||

| dem.f.pl | woman.f.pl | here/there | ||||

| ‘these/those women’ | ||||||

| (28) | Palma Campania | |||||

| a. | stu | / | killu | maʎʎonə | ||

| this.m.sg | that.m.sg | sweater.sg | ||||

| ‘this/that sweater’ | ||||||

| b. | sti | / | killi | maʎʎunə | ||

| this.pl | that.m.pl | sweater.pl | ||||

| ‘these/those sweaters’ | ||||||

| c. | sta | / | kella | kandzonə | ||

| this.f.sg | that.f.sg | song.sg | ||||

| ‘this/that song | ||||||

| d. | sti | / | kelli | kkandzunə | ||

| this.pl | that.f.pl | song.pl | ||||

| ‘these/those songs’ | ||||||

| (29) | Francavilla in Sinni | ||||

| a. | i. | kwistə | kwestə | kistə | |

| this.m.sg | this.f.sg | this.pl | |||

| ii. | kwillə | kwellə | killə | ||

| that.m.sg | that.f.sg | that.pl | |||

| b. | stu / | kwillu | waʎʎonə | ||

| this.m.sg | that.m.sg | young person.sg | |||

| ‘this/that boy’ | |||||

| c. | sta / | kwella | waʎʎonə | ||

| this.f.sg | that.f.sg | young person.sg | |||

| ‘this/that girl’ | |||||

| d. | sti / | killi | waʎʎunə | ||

| this.pl | that.pl | young person.pl | |||

| ‘these/those boys’ | |||||

| (30) | Casalmaggiore | ||||

| a. | kul | ragas | grand | ke/le | |

| dem.m.sg | boy | tall | here/there | ||

| ‘this/that tall boy’ | |||||

| b. | ki | ragas | grand | ke/le | |

| dem.m.pl | boy | tall | here/there | ||

| ‘these/those tall boys’ | |||||

| (31) | Parma | |||||

| a. | i. | sto/kol | gat | |||

| this.m.sg/that.m.sg | cat | |||||

| ‘this/that cat’ (M) | ||||||

| ii. | sta/kla | gata | ||||

| this.f.sg/that.f.sg | cat.f.sg | |||||

| ‘this/that cat’ (F) | ||||||

| iii. | sti/kil | gati | ||||

| this.pl/that.pl | cat.f.pl | |||||

| ‘these/those cats’ (F) | ||||||

| b. | i. | koste (ki) / | kol (la) | l | ɛ | |

| this.m.sg here | that.m.sg there | 3sg.cl.subj | be.3sg | |||

| l | me | libor | ||||

| the.m.sg | my | book | ||||

| ‘This/that is my book’ | ||||||

| ii. | kosti (ki) / | koi (la) | i | in | ||

| this.pl here | that.m.pl there | 3pl.cl.subj | be.3pl | |||

| li | me | libor | ||||

| the.m.pl | my | book | ||||

| ‘These/those are my books’ | ||||||

| iii. | kosta (ki) / | kola (la) | l | ɛ | ||

| this.f.sg here | that.f.sg there | 3sg.cl.subj | be.3sg | |||

| la | me | kamiza | ||||

| the.f.sg | my | blouse.f.sg | ||||

| ‘This/that is my blouse’ | ||||||

| iv. | kosti (ki) / | koli (la) | i | in | ||

| this.pl here | this.f.pl there | 3pl.cl.subj | be.3pl | |||

| al | me | kamizi | ||||

| the.f.pl | my | blouse.f.pl | ||||

| ‘These/those are my blouses’ | ||||||

| (32) | Teramo (Mantenuto 2016, pp. 35–39) | |||

| a. | ʃtu/llu | libbrə | (kwaʃtə)/(kwallə) | |

| this.m.sg /that.m.sg | book | this.m.sg/that.m.sg | ||

| ‘this/that book (here)/(there)’ | ||||

| b. | ʃta/lla | parnindzə | (kaʃtə)/(kallə) | |

| this.f.sg/that.f.sg | apron.f.sg | this.f.sg/that.f.sg | ||

| ‘this apron (here)’ | ||||

| c. | ʃti/lli | kinə | (kəʃtə)/(kəllə) | |

| this.pl/that.pl | dog.pl | this.pl/that.pl | ||

| ‘these/those dogs (here)/(there)’ | ||||

3.3.4. Possessives

4. The Distribution of Bare Nouns

| (33) | a | Concerning the realization of number on nouns, type (26a), where number alternations are systematically realized on suffixes on all classes of nouns, does not display significant differences with respect to Italian; hence, it is expected that these languages allow bare nouns, arguably with a distribution similar to that observed in Italian. |

| b | Type (26b) displays number alternations (on suffixes) on a subset of nouns (the -A class). Similarly, in type (26d), number distinctions are realized only on a subset of classes (-a, -al, -el). The difference between the two types is that in type (26b) all nouns have a suffix, while in type (26d) there are noun classes that do not display any suffix. One might wonder whether the “partial” encoding of the feature Number on nouns is sufficient to license empty Ds (i.e., bare nouns) or, by contrast, whether, for the licensing mechanisms described in Delfitto and Schroten (1991) and Crisma and Longobardi (2020) to be activated, it is necessary that Number be systematically realized on all noun classes. | |

| c | In type (26c), all nouns have suffixes, but the latter are never overtly specified for Number. However, number alternations are realized through (semi-)productive introflexive strategies. According to Crisma and Longobardi (2020, p. 52), “for an empty D the value of Number is recovered via formal agreement between such a D and some category on which it is spelt out”. Thus, these languages should, in principle, license bare nouns. Yet, the fact that, in most languages of this type, number marking is not systematically realized on all noun classes raises the same issues as in (33b). |

4.1. Data Collection

| (34) | a | Singular count nouns cannot be bare in any argument position (35). |

| b | Plural (and mass) nouns cannot be bare in pre-verbal subject position (36a), unless they are modified by an adjective, a PP or a relative clause, (36b). | |

| c | Plural (and mass) nouns can be bare in post-verbal subject position (37), as pivots of existential clauses (38), and in object position (39). |

| (35) | a. | * | ho | visto | studente | (americano) | |

| have.1sg | seen | student.m.sg | American.m.sg | ||||

| Intended: ‘I saw a(n American) student/the (American) student’ | |||||||

| b. | * | studente | (americano) | è | arrivato | ||

| student.m.sg | American.m.sg | be3sg | arrived m.sg | ||||

| Intended: ‘A(n American) student/the American student has arrived’ | |||||||

| (36) | a. | * | studenti | sono | entrati | nell’ | edificio |

| student.m.pl | be.3pl | entered.m.pl | in.the.sg | building.m.sg | |||

| ‘Students have entered the building’ | |||||||

| b. | studenti | da | ogni | parte | del | ||

| student.pl | from | every | part | of.the.m.sg | |||

| mondo | sono | entrati | nell’ | edificio | |||

| world.m.sg | be.3pl | entered.m.pl | in.the.sg | building.m.sg | |||

| ‘Students from all over the world have entered the building’ | |||||||

| (37) | a. | sono | entrati | studenti | nell’ | edificio | |

| be.3pl | entered.m.pl | student.m.pl | in.the.sg | building.m.sg | |||

| ‘Students have entered the building’ | |||||||

| b. | è | caduta | acqua | sul | tavolo | ||

| be.3sg | fallen.f.sg | water.f.sg | on.the.m.sg | table.m.sg | |||

| ‘Water has dropped on the table’ | |||||||

| (38) | a. | ci | sono | studenti | nell’ | edificio | |

| there | be.3pl | student.m.pl | in.the.sg | building.m.sg | |||

| ‘There are students in the building’ | |||||||

| b. | c’ | è | acqua | sul | tavolo | ||

| there | be.3sg | water.f.sg | on.the.m.sg | table.m.sg | |||

| ‘There is water on the table’ | |||||||

| (39) | a. | ho | visto | studenti | nell’ | edificio | |

| have.1sg | seen | student.m.pl | in.the.sg | building.m.sg | |||

| ‘I saw students in the building’ | |||||||

| b. | ho | bevuto | acqua | ||||

| have.1sg | drunk | water.f.sg | |||||

| ‘I drank water’ | |||||||

| (40) | a. | Object |

| b. | Post-verbal subject | |

| c. | Pivot of existential clause: | |

| i. with a “locative” coda | ||

| ii. with a relative clause as the coda | ||

| d. | Pre-verbal subject |

4.2. Data Description

| (41) | Ragusa | ||||||

| a. | * | priparai | tɔrta | (bwonissima) | |||

| prepare1sg.past | cake f.sg | excellent | |||||

| Intended: ‘I prepared an excellent cake’ | |||||||

| b. | * | pittʃɔtta | (mirikana) | arruvau | |||

| young person.f.sg | American.f.sg | arrive.3sg.past | |||||

| Intended: ‘A(n American)/the American girl arrived’ | |||||||

| c. | * | arruvau | pittʃɔtta | (mirikana) | |||

| arrive.3sg.past | young person.f.sg | American.f.sg | |||||

| Intended: ‘A(n American)/the American girl arrived’ | |||||||

| d. | * | pittʃwɔtti | arruvarru | ri | |||

| young people.pl | arrive.3pl.past | from | |||||

| tutta | a | Sitʃilja | |||||

| all.f.sg | the.f.sg | Sicily | |||||

| Intended: ‘Young people arrived from all over Sicily’ | |||||||

| e. | ?? | turisti | spaɲɲwɔli | arruvarru | ajɛri | ||

| tourist.pl | Spanish.pl | arrive.3pl.past | yesterday | ||||

| Intended: ‘Spanish tourists arrived yesterday’ | |||||||

| f. | ddʒɔvanni | vinniu | libbra | ppi | na | ||

| Giovanni | sell.3sg.past | book.pl | for | a.f | |||

| vita | |||||||

| life.f.sg | |||||||

| ‘Giovanni sold books for his entire life’ | |||||||

| g. | ddʒɔvanni | fabbrika | kasi | ranni | |||

| Giovanni | build.3sg | house.pl | big | ||||

| ‘Giovanni builds big houses’ | |||||||

| h. | ri | tutta | a | Sitʃilja | arruvarru | ||

| from | all.f.sg | the.f.sg | Sicily | arrive.3pl.past | |||

| pittʃwɔtti | |||||||

| young people.pl | |||||||

| ‘There arrived young people from all over Sicily’ | |||||||

| i. | ajɛri | arruvarru | turisti | spaɲɲwɔli | |||

| yesterday | arrive.3pl.past | tourist.pl | Spanish.pl | ||||

| ‘There arrived Spanish tourists yesterday’ | |||||||

| j. | ttʃi | su | ffurmikuli | nta | tutta | ||

| there | be.3pl | ant.pl | into | all | |||

| a | kasa | ||||||

| the.f.sg | house.f.sg | ||||||

| ‘There are ants all over the house’ | |||||||

| k. | ttʃi | su | pittʃwɔtti | ka | |||

| there | be.3pl | young people.pl | that | ||||

| nun | vwɔnu | sturjari | |||||

| neg | want.3pl | study | |||||

| ‘There are young people who do not want to study’ | |||||||

| (42) | Novellara | ||||||||

| a. | dʒwani | al | kunteva | *(dal) | buzɛi | ||||

| Gianni | 3sg.cl.subj | tell.3sg.past | of.the.f.pl | lie.f.pl | |||||

| ‘Gianni used to tell lies’ | |||||||||

| b. | dʒwani | al | kunteva | *(dal) | grand | buzɛi | |||

| Gianni | 3sg.cl.subj | tell.3sg.past | of.the.f.pl | big | lie.f.pl | ||||

| ‘Gianni used to tell big lies’ | |||||||||

| c. | i | in | rivè | *(di) | turesta | ||||

| 3pl.cl.subj | be.3pl | arrived | of.the.m.pl | tourist | |||||

| ‘Tourists have arrived’ | |||||||||

| d. | i | in | rivè | *(di) | turesta | spaɲol | |||

| 3pl.cl.subj | be.3pl | arrived | of.the.m.pl | tourist | Spanish | ||||

| ‘Spanish tourists have arrived’ | |||||||||

| e. | a | g | ɛ | *(dal) | matʃi | ||||

| cl.subj | there | be.3 | of.the.f.pl | stain. f.pl | |||||

| insema | al | vistì | |||||||

| above | the.m.sg | dress | |||||||

| ‘There are stains on the dress’ | |||||||||

| f. | a | g | ɛ | *(dal) | matʃi | ||||

| cl.subj | there | be.3 | of.the.f.pl | stain. f.pl | |||||

| k | i | van | mia | via | |||||

| that | 3pl.cl.subj | go.3pl | neg | away | |||||

| ‘There are stains which never go away’ | |||||||||

| (43) | Aidone, Verbicaro | ||||||||

| a. | ajə | ləddʒutə | libbrə | Verbicaro | |||||

| have.1sg | read | books | |||||||

| ‘I have read books’ | |||||||||

| b. | a | skɔla | vɔ | pəggjà | Verbicaro | ||||

| the.f.sg | school.f.sg | want.3sg | hire | ||||||

| pruvəssurə | ddʒugənə | ||||||||

| teacher | young | ||||||||

| ‘The school wants to hire young teachers’ | |||||||||

| c. | an | a | vənì | a | Aidone | ||||

| have.3sg | to | come | to | ||||||

| ferə-mə | visəta | amiʒə | |||||||

| do-1sg.cl.dat | visit.f.sg | friend.pl | |||||||

| ‘Friends are coming to visit me’ | |||||||||

| d. | an | a | vənì | a | Aidone | ||||

| have.3sg | to | come | to | ||||||

| ferə-mə | visəta | amiʒə | fədzjunarə | ||||||

| do-1sg.cl.dat | visit.f.sg | friend.pl | beloved | ||||||

| ‘Beloved friends are coming to visit me’ | |||||||||

| e. | ggjə | su | bbeddə | karuʒə | Aidone | ||||

| there | be.3pl | nice | to | ||||||

| nt | a | fotografia | young person.pl | ||||||

| in | the.f.sg | picture.f.sg | |||||||

| ‘There are nice boys in the picture’ | |||||||||

| (44) | Francavilla in Sinni | ||||||||

| a. | i. | Pumbejə | vennə | pummədorə | ka | ||||

| Pompea | sell.3sg | tomato | that | ||||||

| so | ddietʃ | annə | |||||||

| be.3pl | ten | year | |||||||

| ‘Pompea has been selling tomatoes for ten years’ | |||||||||

| ii. | ajierə | i | tsijə | ennə | munnætə | ||||

| yesterday | the.pl | uncle | have.3pl | peeled | |||||

| fasulə | tutt | a | jurnætə | ||||||

| bean | all | the.f.sg | day | ||||||

| ‘Yesterday my uncles were peeling beans all day long’ | |||||||||

| b. | kwella | dittə | frabbəkə | kæsə | grannə | ||||

| that.f.sg | firm | build.3sg | house | big | |||||

| ‘That firm builds big houses’ | |||||||||

| c. | ennə | arrəvætə | (tʃertə) | furəstjerə | utəmamendə | ||||

| have.3pl | arrived | some | foreigner.3pl | recently | |||||

| ‘Foreigners have arrived recently’ | |||||||||

| d. | sopə | u | vəstitə | tʃə | so | ||||

| above | the.m.sg | dress | there | be.3pl | |||||

| makkjə | |||||||||

| stain | |||||||||

| ‘There are stains on the dress’ | |||||||||

| e. | tʃ | arənə | waɲɲunə70 | ka | |||||

| there | be.3pl.past | young person.pl | who | ||||||

| kurrijənə | sendza | maʎʎə | |||||||

| run.3pl.past | without | shirt | |||||||

| ‘There were children running without their shirts’ | |||||||||

| (45) | Taranto | ||||||||

| a. | aggjə | vənnutə | patånə | pə | ttrɛndə | annə | |||

| have.1sg | sold | potato | for | thirty | year | ||||

| ‘I have been selling potatoes for thirty years’ | |||||||||

| b. | passənə | makənə | tuttə | lə | ddʒurnə | sus | |||

| pass.3pl | car | all | the.pl | day | on | ||||

| ɔ | pɔndə | ||||||||

| to.the.m.sg | bridge | ||||||||

| ‘Cars cross the bridge every day’ | |||||||||

| c. | jɛssə | fumə | da | susə | |||||

| go.out.3sg | smoke | from | above | ||||||

| ‘Smoke comes out from above’ | |||||||||

| (46) | Amalfi | ||||||||

| a. | kella | dittə | frabbəkə | kasə | grɔssə | ||||

| that.f.sg | firm | build.3sg | house | big.f | |||||

| ‘That firm builds big houses’ | |||||||||

| b. | ennə | vənutə | ??(tʃertə) | turistə | spaɲɲwolə | ind | |||

| have.3pl | come | some | tourist | Spanish.m | in | ||||

| o | paesə | ||||||||

| the.m.sg | |||||||||

| ‘Spanish tourists have arrived at the village’ | |||||||||

| c. | tʃə | stannə | sturjendə | ka | nu | vɔnnə | |||

| there | stay.3pl | student.pl | that | neg | want.3pl | ||||

| fa | njendə | ||||||||

| do | nothing | ||||||||

| ‘There are students who do not want to do anything’ | |||||||||

| (47) | Teramo | |||||||

| a. | *(li) | ʃtudintə | annə | skrittə | *(li) | latterə | ||

| the.pl | student.pl | have.3pl | written | the.pl | letter | |||

| ‘(The) students wrote (the) letters’ | ||||||||

| b. | tʃi | ʃta | *(i) | sidʒə | dentra | la | kasə | |

| there | stay.3sg | the.pl | chair.pl | inside | the.f.sg | house | ||

| ‘There are chairs in the house’ | ||||||||

| c. | so | arrivitə | *(li) | pittsə | ||||

| be.3pl | arrived | the.pl | pizza | |||||

| ‘Pizzas have arrived’ | ||||||||

| (48) | Abruzzese (19th century) | |||||||

| a. | è | ddispiacere | chi | pèrdə | parèndə | |||

| be.3sg | pain | who | lose.3sg | relative | ||||

| ‘It is painful for those who lose their relatives’ | ||||||||

| b. | se | métt’ | a | lett’ | e | ccèrche | ||

| SE | put.3sg | on | bed | and | search.3sg | |||

| medecine | ||||||||

| medication | ||||||||

| ‘He goes to bed and looks for medications’ | ||||||||

| (49) | Palma Campania | |||||||

| a. | ʧǝ | stannǝ | sturjendǝ | ʃfatikatǝ | ||||

| there | stay.3pl | student.pl | laggard | |||||

| ‘There are laggard students (= there exist students who are laggard)’ | ||||||||

| b. | ʧǝ | stannǝ | makkjǝ | kǝ | nun | sǝ | llɛvǝnǝ | |

| there | stay.3pl | stain | that | not | SI | go-away.3pl | ||

| ‘There are stains which don’t fade away (= there exist stains…)’ | ||||||||

| (50) | Napoli (adapted from Ledgeway 2009, p. 191) | |||||||

| a. | facevano | pertose | alle | mure | ||||

| make.3pl.past | hole | to.the.pl | wall | |||||

| ‘They made holes in the walls’ (16th cent.) | ||||||||

| b. | cuoglie | fasule | e | torna | fra | doje | ore | |

| pick.2sg | bean | and | come.back.2sg | in | two.f | hour | ||

| ‘Go pick beans and come back in two hours’ (17th cent.) | ||||||||

| c. | quannə | vedə | uommənə | sə | ncə | mena | ncuollə | |

| when | see.3sg | man.pl | SI | loc | throw.3sg | in.neck | ||

| ‘When she sees men, she jumps in their arms’ (19th cent.) | ||||||||

| d. | ce | sta | casə | si | vulitə | |||

| there | stay.3sg | cheese | if | want.2pl | ||||

| ‘There is cheese if you want’ (20th cent.) | ||||||||

| (51) | Bari (Lacalendola 1972, p. 22, in Andriani 2017, p. 76) | |||||||

| a. | ji | akkattə | sèmbə | cosə | mərcàtə | |||

| 1sg | buy.1sg | always | thing | cheap | ||||

| ‘I always buy cheap stuff’ | ||||||||

| b. | u | cùddə | c’ | avànzə | tərrìsə, | tə | préchə | |

| the | that.m | that | exceeds | money.pl | 2sg.cl.dat | praises | ||

| la | vìtə | |||||||

| the.f.sg | life | |||||||

| ‘The person who is owed (by you) will praise your life’ | ||||||||

4.3. A Summary of the Results

5. Summary

|

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Map

Appendix B. Tables

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | |

| Casalmaggiore74 | al | la | i | li |

| Parma | al | la | i | al |

| Reggio Emilia75 | al | la | i | al |

| Novellara | al | la | i | al |

| Correggio | al | la | i | al |

| Savignano s. Rubicone76 | e(l) | la | i | li |

| Teramo77 | lu | la | li | li |

| S.M. Capua Vetere78 | o | a | e[-RF] | e[+RF] |

| Amalfi | o | a | e[-RF] | e[+RF] |

| Palma Campania | o | a | e[-RF] | e[+RF] |

| Felitto79 | (l)u | (l)a | (l)i | (l)i |

| Bari80 | u | la | lə | lə |

| Barletta81 | u | a | i | i |

| Taranto82 | u | a | lə | lə |

| Francavilla in Sinni83 | u | a | i | i |

| Verbicaro84 | u | a | i | i |

| Cellino San Marco85 | lu | la | li | li |

| Mesagne86 | lu | la | li | li |

| Botrugno87 | u | a | i | e |

| Cutro88 | u | a | i | i |

| Nicastro | u | a | i | i |

| Catanzaro | u | a | i | i |

| Reggio Calabria89 | (l)u | (l)a | (l)i | (l)i |

| San Filippo del Mela | u | a | i | i |

| Ragusa | u | a | i | i |

| Ribera | u | a | i | i |

| Mussomeli | u | a | i | i |

| Trapani90 | u | a | i | i |

| Aidone | u | a | i | i |

| (a) Adnominal demonstratives | ||||

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | |

| Casalmaggiore91 | kul … ke kul … le | kla … ke kla … le | ki … ke ki … le | kli … ke kli … le |

| Parma | sto kol | sta kla | sti kil | sti kil |

| Reggio Emilia92 | kost, ste kol, kal kal … ke kal … le/la | kosta / sta kola, kla kla … ke kla … le/la | sti ki ki … ke ki … le/la | ste(l) kal, koli kal … ke kal … le/la |

| Novellara | kəl … ke kəl … le | kla … ke kla … le | ki … ke ki … le | kal … ke kal … le |

| Correggio | kal … ke kal … le/la | kla … ke kla … le/la | ki … ke ki … le/la | kal … ke kal … le/la |

| Savignano s. Rubicone93 | ste ke(l) | sta kla | sti /stal kli | sti kli |

| Teramo94 | ʃtu ssu llu | ʃta ssa lla | ʃti ssi lli | ʃti ssi lli |

| S.M. Capua Vetere95 | stu ssu killu | sta ssa kella | sti[-RF] ssi[-RF] killi[-RF] | sti[+RF] ssi[+RF] kelli[+RF] |

| Amalfi | stu ssu killu | sta ssa kella | sti[-RF] ssi[-RF] killi[-RF] | sti[+RF] ssi[+RF] kelli[+RF] |

| Palma Campania | stu ssu killu | sta ssa kella | sti[-RF] ssi[-RF] killi[-RF] | sti[+RF] ssi[+RF] kelli[+RF] |

| Felitto96 | stu ssu kiru | sta ssa kera | sti ssi kiri | sti ssi kiri |

| Bari97 | stu kuddə | sta kɛdda | sti kiddə | sti kiddə |

| Barletta98 | stu kuddə | sta kɛdda | sti kiddə | sti kiddə |

| Taranto99 | stu kwiddə | sta kwɛdda | sti kiddə | sti kiddə |

| Francavilla in Sinni100 | stu ssu kwillu | sta ssa kwella | stə/-i ssə/-i killə/-i | stə/-i ssə/-i killə/-i |

| Verbicaro101 | stu ssu kwiddə | sta ssa kwidda | stə ssə kwiddə | stə ssə kwiddə |

| Cellino San Marco102 | ʃtu ddu | ʃta dda | ʃti ddi | ʃti ddi |

| Mesagne103 | ʃtu ddu | ʃta dda | ʃti ddi | ʃti ddi |

| Botrugno104 | stu ddu | sta dda | sti ddi | ste dde |

| Cutro105 | ssu kiru | ssa kira | ssi kiri | ssi kiri |

| Nicastro | stu ssu killu | sta ssa killa | sti ssi killi | sti ssi killi |

| Catanzaro | stu ssu kiru | sta ssa kira | sti ssi kiri | sti ssi kiri |

| Reggio Calabria106 | stu ddu | sta dda | sti ddi | sti ddi |

| San Filippo del Mela | stu ssu ddu | sta ssa dda | sti ssi ddi | sti ssi ddi |

| Ragusa | stu ssu ddu | sta ssa dda | sti ssi ddi | sti ssi ddi |

| Ribera | stu ssu ddu | sta ssa dda | sti ssi ddi | sti ssi ddi |

| Mussomeli | stu ssu ddu | sta ssa dda | sti ssi ddi | sti ssi ddi |

| Trapani107 | stu ssu ddu | sta ssa dda | sti ssi ddi | sti ssi ddi |

| Aidone | stu ssu ddu | sta ssa dda | stə ssə ddə | stə ssə ddə |

| (b) Pronominal demonstratives.108 | ||||

| Singular | Plural | |||

| Masculine | Feminine | Masculine | Feminine | |

| Casalmaggiore | kostu (ke) kol (le) | kosta (ke) kola (le) | kosti (ke) koli (le) | kosti (ke) koli (le) |

| Parma | koste (ki) kol (la) | kosta (ki) kola (la) | kosti (ki) koi (la) | kosti (ki) koli (la) |

| Reggio Emilia | kost/ste/kus ke kol le/li lor | kosta/sta/kosta ke kola le | kost/sti/kwis ke kwi le | kosti/ste/kosti ke koli le/kwi le/li lor |

| Novellara | kus ke kul le | kosta ke kola le | kwis ke kwi le | kosti ke koli le |

| Correggio | kost ke kol le/la | kosta ke kola le/la | kwis ke kwi le/la | kosti ke koli le/la |

| Savignano sul Rubicone | kwest kwel | kwesta kwela | kwest kwei | kwesti kwei |

| Teramo109 | kwaʃtə kwassə kwallə | kaʃtə kassə kallə | kəʃtə kəssə kəllə | kəʃtə kəssə kəllə |

| S.M. Capua Vetere | kistə kissə killə | kestə kessə kellə | kistə kissə killə | kestə kessə kellə |

| Amalfi | kistə kissə killə | kestə kessə kellə | kistə kissə killə | kestə kessə kellə |

| Palma Campania | kistə kissə killə | kestə kessə kellə | kistə kissə killə | kestə kessə kellə |

| Felitto | kistu kissu kiru | kesta kessa kera | kisti kissi kiri | keste kesse kere |

| Bari110 | kussə kuddə | kɛssə kɛddə | kissə kiddə | kissə kiddə |

| Barletta | kussə kuddə | kɛssə kɛddə | kissə kiddə | kissə kiddə |

| Taranto111 | kwistə kwiddə | kwɛstə kwɛddə | kistə kiddə | kistə kiddə |

| Francavilla in Sinni | kwistə kwissə kwillə | kwestə kwessə kwellə | kistə kissə killə | kistə kissə killə |

| Verbicaro | kwistə kwissə kwiddə | kwista kwissa kwidda | kwistə kwissə kwiddə | kwistə kwissə kwiddə |

| Cellino San Marco | kwiʃtu kwidda | kwiʃta kwidda | kwiʃti kwiddi | kwiʃti kwiddi |

| Mesagne112 | kuʃtu kuddu/kwiru | kweʃta kwedda/kwera | kwiʃti kwiddi/kwiri | kwiʃti kwiddi/kwiri |

| Botrugno113 | kwistu kwiddu | kwista kwidda | kwisti kwiddi | kwiste kwidde |

| Cutro | kistu kiru | kista kira | kisti kiri | kisti kiri |

| Nicastro | kistu kissu killu | kista kissa killa | kisti kissi killi | kisti kissi killi |

| Catanzaro114 | kistu kissu kiru | kista kissa kira | kisti kissi kiri | kisti kissi kiri |

| Reggio Calabria115 | kistu kissu kiddu | kista kissa kidda | kisti kissi kiddi | kisti kissi kiddi |

| San Filippo del Mela | kistu kissu kiddu | kista kissa kidda | kisti kissi kiddi | kisti kissi kiddi |

| Ragusa | kistu kissu kiddu | kista kissa kidda | kisti kissi kiddi | kisti kissi kiddi |

| Ribera | kistu kissu kiddu | kista kissa kidda | kisti kissi kiddi | kisti kissi kiddi |

| Mussomeli | kistu kissu kiddu | kista kissa kidda | kisti kissi kiddi | kisti kissi kiddi |

| Trapani | kistu kissu kiddu | kista kissa kidda | kisti kissi kiddi | kisti kissi kiddi |

| Aidone | kustə kussə kuu | kusta kussa kudda | kustə kussə kuddə | kustə kussə kuddə |

| Language | Person | Singular M/F | Plural M/F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casalmaggiore117 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | me / mia to so nɔster / nɔstra vɔster / vɔstra lor | me to so nɔster / nɔstri vɔster / vɔstri lor |

| Parma | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | me / mea to so / so, sua, soa nɔster / nɔstra vɔster / vɔstra lor | me to so nɔster / nɔstri vɔster / vɔstri lor |

| Reggio Emilia118 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mio / mia tuo, to(vo) / tua, to(va) suo, so(vo) / sua, so(va) nɔster / nɔstra vɔster / vɔstra lor | me to so nɔster / nɔstri vɔster / vɔstri lor |

| Novellara119 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mio / mia tuo, to / tua, to suo, so / sua, so nɔster / nɔstra vɔster / vɔstra lor | me to so nɔster / nɔstri vɔster / vɔstri lor |

| Correggio | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | me / mia (mea) to so / so, sua, soa nɔster / nɔstra vɔster / vɔstra lor | me to so nɔster / nɔstri vɔster / vɔstri lor |

| Savignano sul Rubicone | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mi / mi(a) tuv / tua suv / sua nɔstre / nɔstra vɔstre / vɔstra suv | mi tu su nɔstre vɔstre su |

| Teramo120 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mi to so nɔstrə vɔstrə so | mi tu su nustrə vustrə su |

| Santa Maria Capua Vetere121 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mijə / mija twojə / toja swojə / soja nwostə / nɔsta vwostə / vɔsta lɔrə | mjejə / mɛjə twojə / tojə swojə / sojə nwostə / nɔstə vwostə / vɔstə lɔrə |

| Amalfi | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mijə / mijə twojə / tojə swojə / sojə nwostə / nɔstə vwostə / vɔstə lɔrə | mjejə / mɛjə twojə / tojə swojə / sojə nwostə / nɔstə vwostə / vɔstə lɔrə |

| Palma Campania | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mijə / mijə twojə / tojə swojə / sojə nwostə / nɔstə vwostə / vɔstə lɔrə | mjejə / mɛjə twojə / tojə swojə / sojə nwostə / nɔstə vwostə / vɔstə lɔrə |

| Felitto | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mmiu / meja twoju / toja swoju / soja nwostu / nɔsta vwostu / vɔsta lɔru | mi(e)i / me(j)e t(w)oi / to(j)e s(w)oi / so(j)e nwosti / nɔste vwosti / vɔste lɔru |

| Bari122 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mi(jə) / me tu(jə) / to su(jə) / so n(w)ɛstə / nɔstə (v)wɛstə / vɔstə (də) lorə | mi(jə) / me tu(jə) / to su(jə) / so n(w)ɛstə / nɔstə (v)wɛstə / vɔstə (də) lorə |

| Barletta123 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mejə / ma towə sowə nɔstə vɔstə lorə | mejə / ma towə sowə nɔstə vɔstə lorə |

| Taranto124 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | miə / me(ə) tuə / to(ə) suə / so(ə) nwɛstə / nɔstə vwɛstə / vɔstə lorə | miə tuə suə nwɛstə vwɛstə lorə |

| Francavilla in Sinni125 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mijə tujə sujə nwostə / nɔstə vwostə / vɔstə lorə | mejə tojə sojə nwostə vwostə lorə |

| Verbicaro126 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mija tuwa suwa nwostə / nɔsta vwostə / vɔsta lɔrə | mija tuwa suwa nwostə / nɔstə vwostə / vɔstə lɔrə |

| Cellino San Marco127 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mia tua sua nweʃʃu / nɔʃʃa vweʃʃu / vɔʃʃa lɔru | mei toi soi nweʃʃi vweʃʃi lɔru |

| Mesagne128 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mia tua sua nweʃtru / nɔʃtra vweʃtru / vɔʃtra lɔru | mia tua sua nweʃtri vweʃtri lɔru |

| Botrugno129 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mɛu / mia tɔu / tɔa sɔu / sɔa nɔstru / nɔstra vɔstru / nɔstra lɔru | mɛi tɔi sɔi nɔstri / vɔstre vɔstri / vɔstre lɔru |

| Cutro130 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mia tua sua nwastru / nɔstra vwastru / vɔstra sua | mia tua sua nwastri vwastri sua |

| Nicastro | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | miu / a mia tua sua nwastru vwastru lɔru | mia tua sua nuastri vuastri lɔru |

| Catanzaro131 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mɛu / mia tɔu (tɔi) / tua sɔu (sɔi) / sua nɔstru / nɔstra vɔstru / vɔstra lɔru | mɛi tɔi sɔi nɔstri vɔstri lɔru |

| Reggio Calabria132 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mɛu / mia tɔu / tua sɔu / sua nɔstru /nɔstra vɔstru / vɔstra lɔru | mɛi tɔi sɔi nɔstri vɔstri lɔru |

| San Filippo del Mela | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mɛ tɔ sɔ nɔstru / nɔstra vɔstru / vɔstra sɔ | mɛ tɔ sɔ nɔstri vɔstri sɔ |

| Ragusa | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | miu / mia tuu (twɔu) / tua suu (swɔu) / sua nwɔstru / nɔstra vwɔstru / vɔstra sɔ | miei twɔi swɔi nwɔstri vwɔstri sɔ |

| Ribera | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mɛ tɔ sɔ nɔstru / nɔstra vɔstru / vɔstra sɔ | mɛ tɔ sɔ nɔstri vɔstri sɔ |

| Mussomeli | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mia tua sua nwastru / nwastra vwastru / vwastra lɔru (di iddi) | mia tua sua nwastri vwastri lɔru (di iddi) |

| Trapani133 | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | meu / mia tou / tua sou / sua nostru /nostra vostru / vostra loru | mei toi soi nostri vostri loru |

| Aidone | 1 sg 2 sg 3 sg 1 pl 2 pl 3 pl | mia tɔ sɔ nɔstrə / nɔstra vɔstrə / vɔstra sɔ | mia tɔ sɔ nɔstrə vɔstrə sɔ |

| Language | Class | Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casalmaggiore135, Parma, Reggio Emilia, Novellara, Correggio | -U -A -E -Vl | ragas, gat ragasa, gata krus kaval kapel | boy, cat girl.f.sg, cat.f.sg cross horse.sg hat.sg | ragas, gat ragasi, gati krus kavai kapei | boy, cat girl.f.pl, cat.f.pl cross horse.pl hat.pl |

| Savignano s. R.136 | -U -A -E | kavɛstar zriʒ klɔmb lamp[-metaph] kapɛl[-metaph] kapɔt[-metaph] fnestra dʒurneda kriatura bikir kanon kan[-metaph] fjor[-metaph] pɛdar[-metaph] | Halter, cherry tree dove lightning.sg hat.sg coat.sg window.f.sg day.f.sg person.f.sg glass cannon dog.sg flower.sg father.sg | kavɛstar zriʒ klɔmb lɛmp[+metaph] kapel[+metaph] kapot[+metaph] fnestri dʒurnedi kriatur bikir kanon kɛn[+metaph] fjur[+metaph] pedar[+metaph] | halter, cherry tree dove lightning.pl hat.pl coat.pl window.f.pl day.f.pl person.pl glass cannon dog.pl flower.pl father.pl |

| Teramo137 | -U -A -E | fijjə vaʃə[-metaph] lettə[-metaph] mɔnəkə[-metaph] fijjə fulmənə petə[-metaph] dulorə[-metaph] | child kiss.m.sg bed.m.sg friar.m.sg child thunder foot.m.sg pain.m.sg | fijjə viʃə[+metaph] littə[+metaph] munəkə[+metaph] fijjə fulmənə pitə[+metaph] dulurə[+metaph] | child kiss.pl bed.pl friar.pl child thunder foot.pl pain.pl |

| S.M. Capua Vetere, Palma Campania, Amalfi | -U -A -E | fiʎʎə fiʎʎə ʃpitalə mesə[-metaph] pɛrə[-metaph] məlonə[-metaph] | child child hospital month.m.sg foot.m.sg melon.m.sg | fiʎʎə fiʎʎə ʃpitalə misə[+metaph] pjerə[+metaph] məlunə[+metaph] | child child hospital month.pl foot.pl melon.pl |

| Felitto138 | -U -A -E | fiʎʎu fiʎʎa spitale mese[-metaph] pɛre[-metaph] piʃkone[-metaph] | child.m.sg child.f.sg hospital.sg month.m.sg foot.m.sg stone.m.sg | fiʎʎi fiʎʎe/ə spitali misi[+metaph] pjeri[+metaph] piʃkuni[+metaph] | child.m.pl child.f.pl hospital.pl month.m.pl foot.m.pl stone.m.pl |

| Barletta | -U -A -E | figgjə figgjə spətålə masə[-metaph] påtə[-metaph] waɲɲɔnə[-metaph] | child child hospital month.m.sg foot.m.sg boy.m.sg | figgjə figgjə spətålə misə[+metaph] pitə[+metaph] waɲɲɔunə[+metaph] | child child hospital month.pl foot.pl boy.pl |

| Bari, Taranto | -U -A -E | figgjə figgjə spətalə mesə[-metaph] petə[-metaph] waɲɲonə[-metaph] | child child hospital month.m.sg foot.m.sg boy.m.sg | figgjə figgjə spətalə misə[+metaph] pitə[+metaph] waɲɲunə[+metaph] | child child hospital month.pl foot.pl boy.pl |

| Francavilla in Sinni | -U -A -E | fiʎʎə fiʎʎə spətælə mesə[-metaph] pedə[-metaph] waɲɲonə[-metaph] | child child hospital month.m.sg foot.m.sg boy.m.sg | fiʎʎə fiʎʎə spətælə misə[+metaph] pjedə[+metaph] waɲɲunə[+metaph] | child child hospital month.pl foot.pl boy.pl |

| Verbicaro139 | -U -A -E | kwatrarə stəndɛnə kwatrara misə məlunə | child gut child.f.sg month melon | kwatrarə stəndɛna kwatrarə misə məlunə | child gut.pl child month melon |

| Mesagne140 | -U -A -E | libbru makina fukaliri mesi[-metaph] peti[-metaph] kulɔri[-metaph] | book.m.sg car.f.sg fireplace month.m.sg foot.m.sg colour.m.sg | libbri makini fukaliri misi[+metaph] pjeti[+metaph] kuluri[+metaph] | book.pl car.pl fireplace month.pl foot.pl colour.pl |

| Cellino S. Marco141 | -U -A -E | libbru makina mise pete kulure | book.m.sg car.f.sg month.m.sg foot.m.sg colour.m.sg | libbri makine misi pjeti kuluri | book.m.pl car.f.pl month.m.pl foot.m.pl colour.m.pl |

| Botrugno142 | -U -A -E | libbru makina mese pete kulure | book.m.sg car.f.sg month.m.sg foot.m.sg colour.m.sg | libbri makine mesi peti kuluri | book.m.pl car.f.pl month.m.pl foot.m.pl colour.m.pl |

| Cutro | -U -A -E | figgju figgja misi niputi | child.m.sg child.f.sg month nephew | figgji figgji misi niputi | child.pl child.pl month nephew |

| Nicastro | -U -A -E | higgju higgja misi niputi | child.m.sg child.f.sg month nephew | higgji higgji misi niputi | child.pl child.pl month nephew |

| Catanzaro | -U -A -E | pittʃuliru pittʃulira paisa prɛvita lutʃa | child.m.sg child.f.sg village.sg priest.sg light.sg | pittʃuliri pittʃuliri paisi prɛviti lutʃi | child.pl child.pl village.pl priest.pl light.pl |

| Reggio Calabria143 | -U -A -E | figgjɔlu figgjɔla misi pɛri | child.m.sg child.f.sg month foot | figgjɔli figgjɔli misi pɛri | child.pl child.pl month foot |

| San Filippo del Mela, Ribera | -U -A -E | karusu karusa misi niputi | child.m.sg child.f.sg month nephew | karusi karusi misi niputi | child.pl child.pl month nephew |

| Ragusa | -U -A -E | pittʃwɔttu pittʃɔtta misi niputi | child.m.sg child.f.sg month nephew | pittʃwɔtti pittʃwɔtti misi niputi | child.pl child.pl month nephew |

| Mussomeli | -U -A -E | pittʃwattu pittʃwatta misi niputi | child.m.sg child.f.sg month nephew | pittʃwatti pittʃwatti misi niputi | child.pl child.pl month nephew |

| Trapani | -U -A -E | pittʃottu pittʃotta misi rendi | child.m.sg child.f.sg month tooth | pittʃotti pittʃotti misi rendi | child.pl child.pl month tooth |

| Aidone | -U -A -E -ng-ə -z-ə | ddibbrə makəna sarturə tavulingə karuzə | book car.f.sg taylor table.sg boy.sg | ddibbrə makənə sarturə tavulij karuʒə | book car.f.sg taylor table.pl boy.pl |

| Language | Class | Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Casalmaggiore145, Parma, Reggio Emilia, Novellara, Correggio | -U -A -E -Vl | rus rusa bɛla grand bel | red red.f.sg nice.f.sg big nice | rus rusi bɛli grand bei | red red.f.pl nice.f.pl big nice.pl |

| Savignano s. R. | -U -A -E | kativ, furb elt[-metaph] amɛr kativa elta grand afabil[-metaph] | bad, shrewd tall.m.sg bitter.m.sg bad.f.sg tall.f.sg big outgoing.m.sg | kativ, furb ilt[+metaph] amer kativi elti grand afebil[+metaph] | bad, shrewd tall.m.pl bitter.m.pl bad.f.pl tall.f.pl big outgoing.m.pl |

| Teramo146 | -U -A -E | ɲɲutə bjangə[-metaph] grossə[-metaph] ɲɲutə bjangə[-metaph] grossə[-metaph] karnalə[-metaph] | naked white.sg big.sg naked white.sg big.sg carnal.sg | ɲɲutə bjingə[+metaph] grussə[+metaph] ɲɲutə bjingə[+metaph] grussə[+metaph] karnilə[+metaph] | naked white.pl big.pl naked white.pl big.pl carnal.pl |

| S.M. Capua Vetere, Palma Campania, Amalfi | -U -A -E | vaʃʃə vjekkjə[+metaph] grwossə[+metaph] vaʃʃə vɛkkjə[-metaph] grɔssə[-metaph] grannə roʃə[-metaph] fətɛndə[-metaph] | low old.m big.m low old.f big.f big sweet.sg stinky.sg | vaʃʃə vjekkjə[+metaph] grwossə[+metaph] vaʃʃə vɛkkjə[-metaph] grɔssə[-metaph] grannə ruʃə[+metaph] fətjendə[+metaph] | low old.m big.m low old.f big.f big sweet.pl stinky.pl |

| Felitto | -U -A -E | vaʃʃu vjekkju[+metaph] grwossu[+metaph] vaʃʃa vɛkkja[-metaph] grɔssa[-metaph] mbortande arotʃe[-metaph] | low.m.sg old.m.sg big.m.sg low.f.sg old.f.sg big.f.sg important.sg sweet.sg | vaʃʃi vjekkji[+metaph] grwossi[+metaph] vaʃʃe/ə vɛkkje/ə[-metaph] grɔsse/ə[-metaph] mbortandi arutʃi[+metaph] | low.m.pl old.m.pl big.m.pl low.f.pl old.f.pl big.f.pl important.pl sweet.pl |

| Barletta | -U -A -E | bbellə bbellə grɛnnə ddʒavənə[-metaph] | beautiful beautiful big young.sg | bbellə bbellə grɛnnə ddʒɔuvənə[+metaph] | beautiful beautiful big young.pl |

| Bari | -U -A -E | vaʃʃə apirtə[+metaph] grwɛssə[+metaph] vaʃʃə apɛrtə [-metaph] grɔssə[-metaph] grannə dotʃə[-metaph] fətɛndə[-metaph] | low open.m big.m low open.f big.f big sweet stinky | vaʃʃə apirtə[+metaph] grwɛssə[+metaph] vaʃʃə apɛrtə [-metaph] grɔssə[-metaph] grannə dutʃə[+metaph] fətində[+metaph] | low open.m big.m low open.f big.f big sweet.m.pl stinky.m.pl |

| Taranto | -U -A -E | vaʃʃə apirtə[+metaph] grwɛssə[+metaph] vaʃʃə apɛrtə [-metaph] grɔssə[-metaph] grannə doʃə[-metaph] fətɛndə[-metaph] | low open.m big.m low open.f big.f big sweet.sg stinky.sg | vaʃʃə apirtə[+metaph] grwɛssə[+metaph] vaʃʃə apirtə[+metaph] grwɛssə[+metaph] grannə duʃə[+metaph] fətində[+metaph] | low open.pl big.pl low open.pl big.pl big sweet.pl stinky.pl |

| Francavilla in Sinni | -U -A -E | vaʃʃə apjertə[+metaph] grwossə[+metaph] vaʃʃə apɛrtə [-metaph] grɔssə[-metaph] grannə ddʒɔvənə[-metaph] pəttsendə[-metaph] | low open.m big.m low open.f old.f big young.sg scrooge.sg | vaʃʃə apjertə[+metaph] grwossə[+metaph] vaʃʃə apjertə[+metaph] grwossə[+metaph] grannə ddʒuvənə[+metaph] pəttsjendə[+metaph] | low open.pl big.pl low open.pl old.pl big young.pl scrooge.pl |

| Verbicaro147 | -U -A -E | vaʃʃə vaʃʃə vaʃʃa grannə ddʒugənə | low low low.f.sg big young | vaʃʃə vaʃʃa vaʃʃə grannə ddʒugənə | low low.pl low big young |

| Mesagne | -U -A -E | vaʃʃu vaʃʃa krandi tɔʃi[-metaph] | low.m.sg low.f.sg big sweet.sg | vaʃʃi vaʃʃi krandi tuʃi[+metaph] | low.pl low.pl big sweet.pl |

| Cellino S. Marco148, Botrugno | -U -A -E | (v)aʃʃu (v)aʃʃa krande | low.m.sg low.f.sg big.sg | (v)aʃʃi (v)aʃʃe krandi | low.m.pl low.f.pl big.pl |

| Catanzaro | -U -A -E | vaʃʃu vaʃʃa granda | low.m.sg low.f.sg big.sg | vaʃʃi vaʃʃi grandi | low.pl low.pl big.pl |

| Reggio Calabria | -U -A -E | vaʃʃu vaʃʃa grandi | low.m.sg low.f.sg big | vaʃʃi vaʃʃi grandi | low.pl low.pl big |

| Cutro, Nicastro, Sicily | -U -A -E | vaʃʃu vaʃʃa (g)ranni | low.m.sg low.f.sg big | vaʃʃi vaʃʃi (g)ranni | low.pl low.pl big |

| Aidone | -U -A -E -ng-ə | nuvə nuva grannə ddʒuvənə bungə | new new.f.sg big young good.sg | nuvə nuvə grannə ddʒuvənə bunə | new new.f.pl big young good.pl |

Appendix C. List of Patterns for Data Collection (Bare Nouns)

| Italian Version | English Translation | |

|---|---|---|

| Plural object | ||

| (1) | Ieri zia Maria e zio Giovanni hanno sbucciato fagioli per tutto il pomeriggio | Yesterday Aunt Maria and Uncle Giovanni peeled beans all afternoon long |

| (1) | Gianni vende patate | Gianni sells potatoes |

| (2) | Quel negozio vende frigoriferi? | Does that shop sell fridges? |

| (3) | L’altro giorno ho trovato formiche nel salone | The other day I found ants in the living room |

| Plural object modified by an adjective | ||

| (4) | Zia Maria e zio Giovanni sbucciano fagioli bianchi da quando erano piccoli | Aunt Maria and Uncle Giovanni have been peeling white beans since they were young |

| (5) | La polizia ha interrogato Gianni e lui ha raccontato bugie enormi | The police questioned Gianni and he told huge lies |

| (6) | Quella ditta costruisce/ha costruito case grandissime | That firm builds/built huge houses |

| (7) | Ho comprato pomodori maturi per fare la salsa | I bought ripe tomatoes to make the sauce |

| Mass object | ||

| (8) | Ho trovato polvere da tutte le parti | I found dust everywhere |

| (9) | Hai farina? | Do you have flour? |

| Mass object modified by an adjective | ||

| (10) | Ieri alla fiera hanno distribuito vino rosso per tutti | Yesterday at the fair they distributed red wine for everyone |

| (11) | Hai pesce fresco? | Do you have any fresh fish? |

| Singular object | ||

| (12) | Ho preparato torta | I prepared a cake |

| Singular object modified by an adjective | ||

| (13) | Ho preparato torta buonissima | I prepared a very good cake |

| Plural subject | ||

| (14) | Turisti sono arrivati in città | Tourists arrived in town |

| (15) | Foglie sono cadute su tutta la strada | Leaves have fallen all over the road |

| Plural subject modified by an adjective | ||

| (16) | Turisti spagnoli sono arrivati in città | Spanish tourists have arrived in town |

| (17) | Rami secchi sono caduti sulla strada | Dead branches have fallen on the road |

| Mass subject | ||

| (18) | Polvere piove dappertutto | It is raining/has rained dust |

| Mass subject modified by an adjective | ||

| (19) | Polvere rossa piove dappertutto | It is raining/has rained red dust |

| Singular subject | ||

| (20) | Studentessa è venuta a parlarmi | A student came to talk to me |

| Singular subject modified by an adjective | ||

| (21) | Studentessa americana è arrivata | An American student came |

| Plural postverbal subject | ||

| (22) | Sono arrivati turisti in questo periodo | Tourists arrived in this period |

| (23) | Sono cadute foglie su tutta la strada | Leaves have fallen all over the road |

| Plural postverbal subject modified by an adjective | ||

| (24) | Sono arrivati turisti spagnoli in città | Spanish tourists have arrived in town |

| (25) | Sono caduti rami secchi sulla strada | Dead branches have fallen on the road |

| Mass postverbal subject | ||

| (26) | Piove/Ha piovuto polvere | It is raining/has rained dust |

| Mass postverbal subject modified by an adjective | ||

| (27) | Piove/Ha piovuto polvere rossa | It is raining/has rained red dust |

| Singular postverbal subject | ||

| (28) | È venuta studentessa a parlarmi | A student came to talk to me |

| Singular postverbal subject modified by an adjective | ||

| (29) | È venuta studentessa americana | An American student came |

| Plural subject of existential sentence (with locative coda) | ||

| (30) | Sul vestito ci sono macchie | There are stains on the dress |

| Mass subject of existential sentence (with locative coda) | ||

| (31) | C’è acqua sul tavolo | There is water on the table |

| Plural subject of existential sentence (with locative coda) modified by an adjective | ||

| (32) | Sul vestito ci sono macchie nere | On the dress there are black stains |

| Mass subject of existential sentence (with locative coda) modified by an adjective | ||

| (33) | C’era aria viziata di là | There was spoiled air over there |

| Plural subject of existential sentence (with a relative clause as the coda) | ||

| (34) | Ci sono studenti sfaticati (= esistono studenti che sono sfaticati) | There are laggard students (= there exist students who are laggard) |

| (35) | Ci sono bambini spensierati (= esistono bambini che sono spensierati) | There are carefree children (= there exist children who are carefree) |

| (36) | Ci sono macchie che non se ne vanno | There are stains that do not fade away |

| Mass subject of existential sentence (with a relative clause as the coda) | ||

| (37) | C’è vino che migliora quando invecchia | There is wine that gets better when it gets old |

| Singular subject of existential clause | ||

| (38) | C’è pianta in giardino | There is a plant in the garden |

| (39) | C’è pianta malata | There is a sick plant |

| (40) | C’è pianta che sta appassendo | There is a plant that’s withering |

| 1 | Concerning the relation between the representation of (morphological and semantic) Number and the realization and meaning of bare nouns, see also, among many others, at least Cheng and Sybesma (1999), Munn and Schmitt (2002, 2005), Zamparelli (2000), Dayal (2001), Déprez (2005), Heycock and Zamparelli (2005, p. 234), Tsoulas (2009), Stark (2016), Pinzin and Poletto (2022), and literature therein. |

| 2 | Except for the class of nouns ending in -al (plural -aux) and few other lexical instances. The suffix -s is only pronounced under liaison. We refer to Massot (2014, pp. 1837–40) for a list of the environments where visible traces of number morphology appear on nominal items in French. |

| 3 | wm in the gloss. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | See, on this same topic, recent work by Pinzin and Poletto (2022). |

| 7 | The data were collected from native speakers and, when possible, double-checked against the existing literature. A description of the areas under investigation, with the relevant literature, can be found at http://www.parametricomparison.unimore.it/site/home/projects/prin-2017/documents-and-materials.html (accessed on 18 August 2022; the content of this section is regularly updated as work progresses). For a discussion of their classification and major features, we refer to Pellegrini (1977), Maiden and Parry (1997), Cortelazzo et al. (2002), Manzini and Savoia (2005), Loporcaro (2009), Ledgeway and Maiden (2016), among many others. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | Avolio (1989), Del Puente and Fanciullo (2004). Data collected by G. Silvestri (Santa Maria Capua Vetere), V. Stalfieri (Amalfi) and I. della Corte (Palma Campania). |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | Data collected by V. Stalfieri. |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | |

| 30 | Peri (1959), Varvaro (1981), Trovato (1998, 2013), Raccuglia (2003), Trovato and Menza (2020). For a recent survey, see also Costa (2020). These dialects are assumed to originate from migrations from northern Italy which took place starting from the Norman Conquest of Sicily (1061–1091). Our data were provided by F. Ciantia. |

| 31 | See also Loporcaro (2009, pp. 97–106). |

| 32 | Rohlfs (1966, §§ 141–47), Loporcaro (2009, p. 80), see Cangemi et al. (2010, Section 2) for a discussion and for the literature. |

| 33 | In the transcriptions of the examples, we mark only the allophones which are relevant for the purposes of our description, are peculiar of individual dialects, or oppose different dialects. To signal such phonetic peculiarities, we adopted conventional IPA symbols (https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/content/ipa-chart, accessed on 3 May 2022), with one exception: the symbol <å> signals the low-mid central vowel (allophone of /a/ in open stressed syllable) found in Barletta and Taranto (Mancarella 1998). Vowel length and stress are generally not marked, with the exception of stressed final vowels. Geminates are signalled by the repetition of the relevant symbol. As for affricates, only the occlusive moment is duplicated (e.g., ts → tts). The examples taken from the literature, unless otherwise specified, are reproduced in their original form. |

| 34 | |

| 35 | See also Idone and Silvestri (2018, Section 2), to which we also refer for a description (and examples) of the conditions on metaphony in Verbicarese. |

| 36 | Metaphony has different manifestations across the Romance dialects of Italy. We refer to the literature for more detailed typologies and examples, e.g., among many others, Rohlfs (1966, 1968, 1969), Calabrese (1984–1985, 1998, 2008), Maiden (1991), Fanciullo (1994), De Blasi and Fanciullo (2002), Russo (2007), Barbato (2008), Loporcaro (2016), and literature therein. We also refer to Savoia and Maiden (1997) for a detailed survey of the internal variability concerning these phenomena in the Romance dialects of Italy. For the purposes of the present paper, we want to stress the role of metaphony, originally a phonetic/phonological phenomenon, in preserving morphological number alternations on nominal structures; this, in turn, has consequences on the realization of bare nouns in argument position, i.e., a syntactic process. For this reason, in what follows, we mostly refer to those dialects (especially group (4b) and Savignano sul Rubicone, (4a)), where metaphony impacts the morphological realization of Number. In some dialects, root vowel alternations superficially matching singular vs. plural interpretation also result from propagation (Rizzi and Savoia 1993). Manzini and Savoia (2016, p. 221) describe propagation as “the result of the spreading of [U] properties from an unstressed nucleus to the stressed nucleus (or [a] vowel) immediately to the right”. Phenomena of this type are visible for instance on the stressed vowel of nouns preceded by the masculine singular form of the definite article (e.g, u lwibbrə ‘the book’ vs. i libbrə ‘the books’ in Verbicaro; see also Idone and Silvestri 2018). |

| 37 | Yet, in some dialects (e.g., Francavilla in Sinni, Taranto: see Table A4 and Table A5) adjectives ending in -u/-a developed a different paradigm: in the masculine (-u/-i), as expected, the combination of metaphony and weakening of final -u/-i generated one item undistinguished for singular and plural (e.g., nwovə < novu(m) and novi); in the feminine, the expected form nɔvə (< nova(m) and novae) is only used in the singular, while the plural analogically generalizes nwovə. |

| 38 | Detailed descriptions of these parameters and their internal dependencies, which are summarized in (12), can be found in Longobardi et al. (2013, Appendix) and Crisma and Longobardi (2020). The updated list of their manifestations can be found in Crisma et al. (2020, Supplementary Material). |

| 39 | For a recent description of the featural composition of the head D, see Crisma and Longobardi (2020). |

| 40 | |

| 41 | For the representation of parameter dependencies and implications, see Longobardi and Guardiano (2009), Guardiano and Longobardi (2017), Roberts (2019), and literature therein. |

| 42 | We also refer to Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, chp. 8) for a detailed list of examples. |

| 43 | See also Manzini and Savoia (2005, chps. 2, 4, 5). |

| 44 | See also Bari (Andriani, p.c.): stu pumədorə jɛ da ʃəttà (‘this tomato must be thrown away’) vs. sti pumədurə so da ʃəttà (‘these tomatoes must be thrown away’). |

| 45 | |

| 46 | In the languages of the sample, nouns and adjectives display very similar patterns concerning number marking. In some dialects, metaphony affects the representation of gender on adjectives (on the strict relation between Gender and Number in these dialects see also note 49 below). Here, we focus on nouns only. Examples of number marking on adjectives in the dialects of the sample are reported in Table A5. See also Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 574–660). |

| 47 | However, items exhibiting both strategies are found across Italy (cf. Foresti 1988): see, for instance, fjore vs. fjiuri ‘flower/s’ in Padova (Trumper 1972, pp. 13–18), lɛpre vs. lepri ‘hare/s’ in Macerata (Biondi 2012 cited in Fanciullo 2015, p. 130), fɔrte vs. fuerti ‘strong.sg/pl’ in Central Salento (Fanciullo 1994, p. 574). |

| 48 | See also Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 583–90). |

| 49 | But see Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 642–60) and Pescarini (2020). The literature on Romance nominal systems has shown that the realization of Number on nouns is strongly related to that of Gender: “the assignment of grammatical Number depends on the assignment of a formal class to a linguistic category” (Picallo 2008, p. 47). We refer to Picallo (2008), and to work by (e.g., Manzini and Savoia 2005, 2017, 2018, 2019) and Pinzin and Poletto (2021, 2022) for a discussion and a summary of the literature. To account for the relation between Number, Gender and inflectional Class, and for their morphosyntactic realization, the hypothesis of a “layered view of plural” (Manzini 2020, p. 6), suggesting multiple Number positions, has been variously explored in the literature (see, e.g., Wiltschko 2008; Landau 2016; Manzini 2020 and literature therein). |

| 50 | In some dialects of Sicily, a plural ending -a is visible on nouns ending in -u in the singular: stu rrɔddʒu (this.m.sg clock.m.sg), sti rrɔddʒa (this.pl clock.pl) [Ribera]; u libbru bbɛllu (the.m.sg book.m.sg beautiful.m.sg), i libbra bbɛlli (the.pl book.pl beautiful.pl) [Mussomeli, Ragusa]. Also, some nouns ending in -i (< -E(M)) take the plural affix -a: u prufissuri pittʃwɔttu (the.m.sg professor.m.sg young.m.sg), i prufissura pittʃwɔtti (the.pl professor.pl young.pl). These -a plurals are well-known to the literature: we refer to Rohlfs (1968, § 368) and Sornicola (2010) for an overview. |

| 51 | Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 590–99) suggest that -a is to be analyzed as a noun class morpheme, while -i is a “quantificational denotation morpheme” (“morfema a denotazione quantificazionale”, 596), denoting both plural number and feminine gender. In other items, such as demonstratives and quantifiers, -i would only express quantificational information (i.e., plural number, 596–597). See also Pescarini (2020). It is not unreasonable that the plural suffix -i instantiates an innovation probably introduced after the loss of final -I, -U, and -E. The origin of this suffix is unclear. Rohlfs (1968, § 363) suggests it to be an analogical creation based on Latin feminine nouns ending in -ĬAE (such as in BESTĬAE > bestij), where final -i was reanalyzed as a plural feminine morpheme. Reasonably, the creation of plural -i happened after the loss of final vowels. |

| 52 | There are exceptions: for example, like in French (see note 2), masculine nouns ending in -al/-el in the singular take the suffix -ai/-ei in the plural (kaval/kavai, ‘horse.sg, horse.pl’; kavel/kavei ‘hair.sg, hair.pl’). |

| 53 | See, for a discussion of these systems, Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 637–42). As it can be seen in the examples (23) and (24), gender alternations are maintained on (some) adjectives. |

| 54 | The form bbwellə results from propagation (see note 36). |

| 55 | See, e.g., Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 637–39), Giuliani (2001, pp. 145–46), Ledgeway (2007, pp. 106–7). |

| 56 | For a discussion of similar phenomena in other Romance dialects of Southern Italy, see Manzini and Savoia (2016, Section 3). |

| 57 | In Francavilla in Sinni, most adjectives are only post-nominal; by contrast, the adjective bbellə (along with few additional others) can be realized either pre- or post-nominally. |

| 58 | |

| 59 | See also Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 574–75). |

| 60 | In several dialects of Campania, the plural form of the definite determiner triggers Rafforzamento Fonosintattico (Fanciullo 1997; Loporcaro 1997) in the feminine: a fiʎʎə ~ e ffiʎʎə ‘the daughter ~ the daughters’ vs. o fiʎʎə ~ e fiʎʎə ‘the son ~ the sons’. On the relation between RF and morphosyntactic structures, see also D’Alessandro and Scheer (2013). |

| 61 | See also Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 582–83). |

| 62 | Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 552–74), Guardiano (2014), Guardiano et al. (2016, 2018), Silvestri (2020), and references therein). |

| 63 | Kinship expressions are exceptional: when a possessive modifies a kinship noun in the singular, and the latter refers to a unique individual, it does not co-occur with any determiner and has a “definite” reading only: mio padre (lit. ‘my father’) vs. *il mio padre (lit. ‘the my father’). In some dialects of our sample (e.g., Salentino, Santa Maria Capua Vetere), when occurring with a kinship noun in the singular, with the interpretation described above, possessives are realized as enclitic (D’Alessandro and Migliori 2017 and literature therein; Manzini and Savoia 2005, vol. III, pp. 660–749). |

| 64 | Il mio libro (lit. ‘the.m.sg my.m.sg book.m.sg’) vs. i miei libri (lit. ‘the.m.pl my.m.pl book.m.pl’), la mia macchina (lit. ‘the.f.sg my.f.sg car.f.sg’) vs. le mie macchine (lit. ‘the.f.pl my.f.pl car.f.pl’). |

| 65 | In several dialects, adnominal possessives display “weaker” morphophonological structure as compared to pronominal ones (Cardinaletti 1998; Cardinaletti and Starke 1994, 1999; Manzini and Savoia 2005, vol. III, pp. 570–74, a.o.). In Table A3, for each dialect, we list the pronominal forms, whose paradigms are more variable than those of articles and demonstratives with respect to the realization of number alternations. |

| 66 | For further examples, see Manzini and Savoia (2005, vol. III, pp. 554–55). |

| 67 | For some dialects (e.g., those used in Guardiano et al. 2016), data concerning the distribution of bare nouns had been collected during previous fieldwork. These data were integrated with novel ones, with the exception of two dialects: Santa Maria Capua Vetere (because the speaker was no more available) and Teramo. For the latter, we found extensive material in the literature, especially Mantenuto (2015a, 2015b, 2016), and the data found in the TerraLing group SSWL (http://test.terraling.com/groups/7, accessed on 3 August 2022; Koopman and Guardiano 2014–2018): properties O 01 1_Indef mass_can be bare to O 09 5_PN+A_Order PN A and S01_Existential constructions to S 04 3_Indef Pl Ns (Subj) must have an article. |

| 68 | The sentences provided by the speakers for each dialect can be found here: http://www.parametricomparison.unimore.it/site/home/projects/prin-2017/documents-and-materials.html; accessed on 18 August 2022 (the content of this section is regularly updated as work progresses). |

| 69 | On the relation between the morphological exponence of gender and number and the realization of nominal determination systems in Romance, see at least Stark (2007, 2016); for a recent analysis of the alternation between bare nouns and partitive articles, Pinzin and Poletto (2021). |

| 70 | Both variants waɲɲunə and waʎʎunə are found in Francavilla. |

| 71 | For older varieties, see also Ugolini (1959, p. 120). |

| 72 | A difference between Italian and the dialects where bare nouns are grammatical concerns the acceptability of bare plurals/mass modified by an adjective, a PP or a relative clause as preverbal subjects. These are grammatical in Italian while they are only marginally accepted in the dialects. |

| 73 | All the paradigms listed in the tables have been provided by our informants and double-checked against the available literature, including Manzini and Savoia (2005, chp. 8). For each dialect, we mention at least one bibliographical source. |

| 74 | |

| 75 | Dialects of Emilia: Badini (2002), Foresti (1988, p. 579), Hajek (1997), Rohlfs (1968, pp. 104–5). Reggio Emilia: Ferretti (2016, p. 10); Parma: Bernini (1942), Michelini (2017). |

| 76 | Pelliciardi (1977). |

| 77 | |

| 78 | |

| 79 | |

| 80 | |

| 81 | |

| 82 | |

| 83 | |

| 84 | |

| 85 | |

| 86 | |

| 87 | |

| 88 | |

| 89 | |

| 90 | |

| 91 | |

| 92 | Dialects of Emilia: Badini (2002), Foresti (1988, p. 581). Reggio Emilia: Ferretti (2016, p. 10); Parma: Bernini (1942), Michelini (2017). |

| 93 | Pelliciardi (1977). |

| 94 | |

| 95 | |

| 96 | Cerullo (2018, p. 165) for distal demonstratives. Cerullo (p.c.) for proximal and medial demonstratives. |

| 97 | |

| 98 | |

| 99 | |

| 100 | Lausberg (1939, p. 143) lists some paradigms of various dialects of the area, which slightly differ from those of Francavilla. |

| 101 | |

| 102 | |

| 103 | |

| 104 | |

| 105 | |

| 106 | |

| 107 | |

| 108 | The references for this table are the same as those for table S2/A, unless otherwise specified. |

| 109 | |

| 110 | |

| 111 | |

| 112 | |

| 113 | |

| 114 | |

| 115 | |

| 116 | |

| 117 | |

| 118 | Dialects of Emilia: Badini (2002), Foresti (1988, pp. 580–81). Reggio Emilia: Ferretti (2016, p. 35); Parma: Bernini (1942), Michelini (2017). |

| 119 | |

| 120 | |

| 121 | Dialects of Campania: Ledgeway (2009, p. 247). |

| 122 | |

| 123 | |

| 124 | |

| 125 | |

| 126 | |

| 127 | |

| 128 | |

| 129 | |

| 130 | |

| 131 | |

| 132 | |

| 133 | |

| 134 | The table provides a selection of examples which show the number marking strategies visible on different noun classes in the dialects of the sample. |

| 135 | |

| 136 | |

| 137 | |

| 138 | In Felitto several nouns have both root vowel alternations and suffixes. |

| 139 | Loporcaro and Silvestri (2015, pp. 69–72). The suffix -a in the word stəndɛna is a residual of the neuter Latin suffix -A. |

| 140 | Mancarella (1998, pp. 89–92, 106–7, 147–48). In Mesagne, final -E and final -I are both realized as -i (Mancarella 1998, pp. 106–7). Thus, there is no suffix alternation between singular and plural on nouns originally ending in -E. In some such nouns, number alternations are realized through metaphonetic alternations of the root vowel, as shown in the examples. This sets a difference with the two other dialects of Salento (Botrugno and Cellino San Marco), where the alternation -E/-I was mantained. |

| 141 | |

| 142 | |

| 143 | |

| 144 | The table provides a selection of examples which show the number marking strategies visible on different adjective classes in the dialects of the sample. |

| 145 | |

| 146 | |

| 147 | Loporcaro and Silvestri (2015, pp. 69–72). The suffix -a in the word vaʃʃa is a residual of the neuter Latin suffix -A. |

| 148 | |

| 149 | Sentences 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 21, 22, 29, 30, 39, 40, 41 are ungrammatical in Italian. Sentences 17, 18 and 20 are marginally accepted by some speakers of Italian. |

References

- Acquaviva, Paolo. 2008. Lexical Plurals. A Morpho-Semantic Approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexiadou, Artemis. 2011. Plural Mass Nouns and the Morpho-syntax of Number. In Proceedings of the 28th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Edited by Mary Byram Washburn, Katherine McKinney-Bock, Erika Varis, Ann Sawyer and Barbara Tomaszewicz. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project, pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasio, Alessandra. 2022. I sintagmi nominali nel dialetto di Cutro. Bachelor’s thesis, Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Andriani, Luigi. 2017. The Syntax of the Dialect of Bari. Doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Avolio, Francesco. 1989. Il limite occidentale dei dialetti lucani nel quadro del gruppo «altomeridionale», con considerazioni a proposito della linea Salerno–Lucera. L’Italia dialettale 52: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Badini, Bruna. 2002. L’Emilia Romagna. In I dialetti italiani. Storia, struttura, uso. Edited by Manlio Cortelazzo, Carla Marcato, Nicola De Blasi and Gianrenzo P. Clivio. Torino: UTET, pp. 375–413. [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, Marcello. 2008. Metafonia napoletana e metafonia sabina. In I dialetti italiani meridionali tra arcaismo e interferenza. Edited by Alessandro De Angelis. Palermo: CSFLS, pp. 275–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bernini, Ferdinando. 1942. Il dialetto parmigiano come linguaggio neo-latino. Quaderni de “La giovane montagna” Volume 19. Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books/about/Il_dialetto_parmigiano_come_linguaggio_n.html?id=-a9wnQEACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 18 August 2022).

- Bernstein, Judy. 1997. Demonstratives and reinforcers in Romance and Germanic languages. Lingua 102: 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, Adriano. 2012. Vocabolario. Il dialetto di San Severino Marche confrontato con altri dialetti marchigiani arcaici e contemporanei. San Severino Marche: Hexagon Group. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, Andrea. 1984–1985. Metaphony in Salentino. Rivista di Grammatica Generativa 9–10: 3–140. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, Andrea. 1998. Metaphony revisited. Rivista di Linguistica 10: 7–68. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, Andrea. 2008. Metaphony. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20130921053600/http://homepages.uconn.edu/~anc02008/Papers/METAPHONY.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2022).

- Cangemi, Francesco, Rachele Delucchi, Michele Loporcaro, and Stephan Schmid. 2010. Vocalismo finale atono “toscano” nei dialetti del Vallo di Diano (Salerno). In Parlare con le persone, Parlare alle Macchine. Edited by Francesco Cutugno, Pietro Maturi, Renata Savy, Giovanni Abete and Iolanda Alfano. Torriana: EDK, pp. 477–90. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinaletti, Anna. 1998. On the deficient/strong opposition in possessive systems. In Possessors, Predicates, and Movement in the Determiner Phrase. Edited by Artemis Alexiadou and Chris Wilder. Amsterdam: Benjamins, pp. 17–53. [Google Scholar]