1. Introduction

Subject clitics in northern Italo-Romance are an ideal testing ground to assess theory-driven hypotheses. Hundreds of genealogically-related vernaculars provide us with a quasi-laboratory environment in which variables can be pinned down with all other conditions being equal.

The occurrence of expletive subject clitics in impersonal

1 clauses;

The co-occurrence of subject clitics and operator-like subjects;

The presence vs. absence of subject clitic forms for each person of the paradigm;

The presence of patterns of syncretism.

The analysis relies on the statistical analysis of data from 350 dialects gathered from

Manzini and Savoia (

2005) and the ASIt database http://asit.maldura.unipd.it/ (accessed on 9 October 2022) (Syntactic Atlas of Italy). The dataset analyzed in this work can be downloaded from the open access repository Zenodo (

Supplementary Materials). Statistical analyses show that some of the above variables are, to different extents,

associated, thus confirming

Renzi and Vanelli’s (

1983) view that microvariation can be captured by higher-grade generalizations in the form of entailments. The kind of variation we observe in northern Italo-Romance recalls analogous patterns of variation that are found across ‘major’ languages and linguistic families. The factors determining variation, however, are partially hidden by a kaleidoscope of microparametric variants, which may well originate from “modes of PF-realization” (

Roberts 2014, p. 177). This microparametric noise is particularly persistent when genealogically-related languages (viz. dialects) are compared (from now on, the terms

language and

dialect are used as synonyms). For this reason, in-depth analyses of single varieties risk being misleading, whereas simple quantitative measurements are key to discovering new trends or validating previous generalizations. The fact that certain clusters of syntactic variables are found in a statistically significant sample of languages/dialects cannot be a mere historical accident.

In testing the associations between syntactic variables, the goal of the present work is twofold: theoretically, it aims to engage with the formal literature on subject clitics and related issues; methodologically, it aims to illustrate the benefits of quantitative, data-driven approaches to syntactic microvariation.

The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 overviews some properties of subject clitics in northern Italo-Romance dialects;

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5 deal with the empirical variables under examination: expletives, doubling, and paradigmatic arrays (i.e., person-driven gaps and syncretisms).

Section 6 summarizes the results of previous sections;

Section 7 elaborates on the relationship between subject clitics and verbal agreement.

Section 8,

Section 9 and

Section 10 address theoretical questions.

Section 8 focuses on the role of the Extended Projection Principle (EPP) in accounting for northern Italo-Romance clitic systems.

Section 9 compares two alternative approaches to clitic dependencies.

Section 10 elaborates on the nature of subject clitic doubling; it is argued that variation does not necessarily result from the inner composition of subject clitic formatives but the syntactic encoding of associated DP subjects.

Section 11 concludes.

2. Syntactic and Morphological Properties of Subject Clitics

Northern Italo-Romance dialects are characterized by the presence of elements that, etymologically, derive from Latin nominative personal pronouns. These elements are nowadays

clitic, i.e., they cannot bear stress and must be adjacent to the inflected verb as in (1a). Other clitic elements such as object clitics and negation heads can occur between subject clitic formatives and the inflected verb as in (1b), whereas phrasal constituents cannot.

| (1) | a. | la | ˈriva | doˈmaŋ | (Veronese, Veneto) |

| | | 3sg.f.nom= | arrive.3sg | tomorrow | |

| | | ‘She arrives tomorrow.’ |

| | b. | la | te | ˈriva | doˈmaŋ |

| | | 3sg.f.nom= |

2sg.dat= | arrive.3sg | tomorrow |

| | | ‘You will receive it tomorrow.’ (lit. ‘It/her will arrive to you tomorrow’) |

In main interrogatives, subject clitics are placed postverbally (i.e., in

enclisis, see (2a)), whereas object clitics remain preverbal (in

proclisis, see (2b)):

| (2) | a. | ̍riv- | ela | doˈmaŋ | (Veronese) |

| | | arrive.3sg | =3sg.f.nom= | tomorrow | |

| | | ‘Does she/it arrive tomorrow?’ |

| | b. | te | ̍riv- | ela | doˈmaŋ |

| | |

2sg.dat= | arrive3sg | =3sg.f.nom | tomorrow |

| | | ‘Will you receive it tomorrow?’ (lit. ‘Will it/she arrive to you tomorrow?) |

Two properties of northern Italo-Romance subject clitics have been extensively debated, often in comparison with French subject clitics. First, Italo-Romance subject clitics can co-occur with non-topicalized phrasal subjects, see (3).

| (3) | la ˈletara | la | ̍riva | doˈmaŋ | (Veronese) |

| | the letter | 3sg.f.nom= | arrive.3sg | tomorrow | |

| | ‘The letter (it) will arrive tomorrow.’ |

Second, the proclitic and the enclitic series of subject clitics are not isomorphic. Proclitics often differ from enclitics; additionally, some pronouns, either proclitic or enclitic, are missing as shown in (4) (

from Benincà 1994, pp. 41–42):

| (4) | a. | __ | magno | a’. | (cosa) | magno-(i)? |

| | | | eat.1sg | | (what) | eat.1sg=1sg |

| | b. | te | magni | b’. | (cosa) | magni-to? |

| | | 2sg= | eat.2sg | | (what) | eat.2sg=2sg |

| | c. | el/la | magna | c’. | (cosa) | magne-lo/la? |

| | | 3sg.m/f = | eat.3sg | | (what) | eat.3sg=3sg.m/f |

| | d. | __ | magnèmo | d’. | (cosa) | magnèmo-(i)? |

| | | | eat.1pl | | (what) | eat.1pl=1pl |

| | e. | __ | magnè | e’. | (cosa) | magnè-o? |

| | | | eat.2pl | | (what) | eat.2pl=2pl |

| | f. | i/le | Magna | f’, | (cosa) | magne-li/le? |

| | |

3pl.m/f = | eat.3pl | | (what) | eat.3pl=3pl.m/f |

The data in (3) and (4) led scholars to hypothesize that Italo-Romance clitics are better analyzed as agreement markers, rather than fully-fledged pronouns. In fact, bona fide inflectional endings deriving from enclitic pronouns are attested, especially in Lombard dialects. In some of these dialects—especially those in which final vowels (but -

a) are systematically lost—enclitic pronouns were turned into agreement suffixes such as 1sg -

i < Lat.

ego ‘I’ in (5a), 2sg -

t <

tu ‘you’ in (5b), 2pl -

v/f <

vos ‘you.

pl’.

2 However, this evolution is not widespread in the whole northern Italo-Romance area. Moreover, endings deriving from the reanalysis of enclitic pronouns co-occur with subject proclitics as in (5). Hence, although one can safely conclude that certain enclitics have been turned into affixes, the same analysis cannot be extended to all clitic forms and all languages.

Other phenomena militate against an analysis of subject clitics as inflectional endings.

First, it is true that certain enclitics have been reanalyzed as suffixes as in (5) or that the shape of proclitics and enclitics is often irregular, cf. (4). However, the fact remains that the mechanism of subject inversion in (2) is a hallmark of pronominal syntax. Given (2), the hypothesis that all enclitics have been uniformly reanalyzed, yielding an ‘interrogative conjugation’ in all dialects, raises more problems than it solves, from both typological and theoretical standpoints.

Second, in some dialects (noticeably, in central Venetan, cf.

Benincà 1994;

Benincà and Poletto 2004) the syntax of clitic pronouns is sensitive to discourse, a behavior that cannot be predicted under an inflectional analysis of subject clitics. In Paduan, for instance, third person subject proclitics are mandatory when a preverbal subject is topicalised (i.e., when a preverbal subject precedes another topic constituent a in (6a)). Otherwise, in a context where we cannot establish whether the subject is topicalized or not, subject clitics can be omitted, see (6b).

| (6) | a. | a ˈletara | a ˈmarjo | *(e󠅠̯a) | ̍riva | doˈmaŋ | (Pad.) |

| | | the letter | to Mario | 3sg.f.nom= | arrive.3sg | tomorrow | |

| | | ‘The letter, to Mario, (it) will arrive tomorrow.’ |

| | b. | a ˈletara | (e󠅠̯a) | ̍riva | doˈmaŋ | | |

| | | the letter | 3sg.f.nom= | arrive.3sg | tomorrow | | |

| | | ‘The letter, (it) will arrive tomorrow.’ |

Third,

Poletto (

2000) shows that non-topical, operator-like elements such as wh pronouns and (bare) quantifiers are doubled more rarely than nominal and pronominal subjects (more on this in

Section 3). If clitics were agreement heads, they should occur across the board, regardless of the nature of the doubled phrasal element.

Fourth, the distribution of subject clitics in impersonal constructions is particularly problematic for the analysis of subject clitics in terms of inflection. In most northern Italian dialects, expletive subject clitics occur with various classes of nonthematic verbs (e.g., weather verbs) or in sentences containing postverbal/clausal subjects. However, the distribution of expletive clitics across dialects and clausal contexts is subject to a high degree of variation that is incompatible with a uniform inflectional analysis of subject clitics (more on this in

Section 4).

3. Doubling

As mentioned in

Section 2, most northern Italian dialects allow the co-occurrence of subject clitics and phrasal subjects. However, not all subjects can be doubled by clitic formatives.

Poletto (

2000) shows that, whereas pronominal and DP subjects are doubled quite systematically (see (7a)), operator-like subjects such as wh elements and bare quantifiers are doubled less frequently; see (7b).

| (7) | a. | ˈmarjo | el | ˈriva | doˈmaŋ | (Veronese) |

| | | Mario | 3sg.m.nom= | arrive.3sg | Tomorrow | |

| | | ‘Mario (he) will arrive tomorrow.’ |

| | b. | ʧi | ˈriv(a) | *elo | | |

| | | who | arrive.3sg | =3sg.m.nom | | |

| | | ‘Who will arrive?’ |

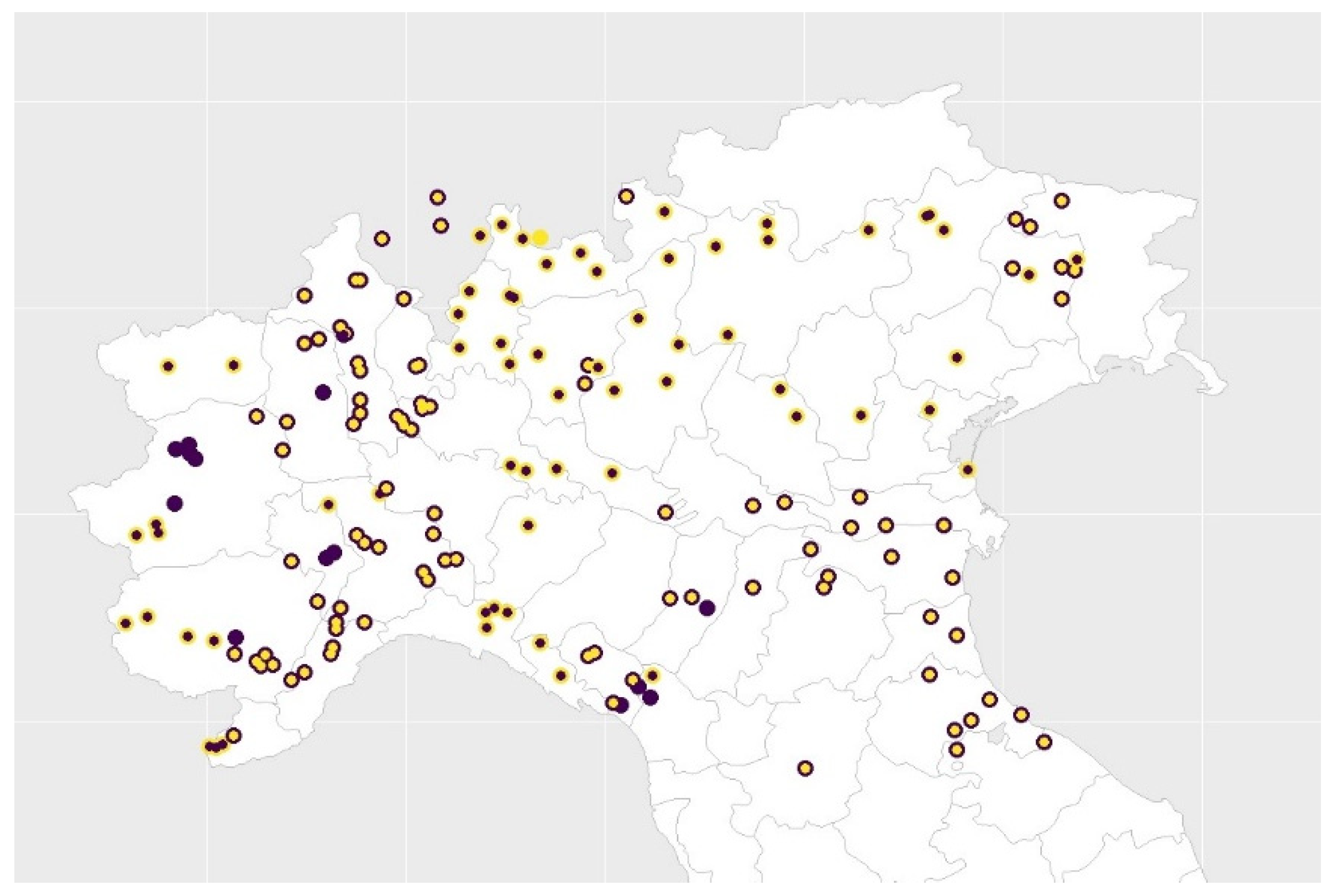

The geographical distribution of dialects allowing the doubling of operator-like subjects is illustrated in

Figure 1, which shows the presence (purple) vs. absence (yellow) of subject clitics in co-occurrence with the interrogative pronoun

who (squares indicate the datapoints in which doubling is restricted to certain clausal environments such as clefts).

The map in

Figure 1 shows that doubling is widespread in the mountain areas, both on the Alps and the Apennines, whereas the dialects spoken in southern Liguria and the eastern part of the Po River valley tend to drop subject clitics when the phrasal subject is a wh element. It is worth noting that the doubling of operator-like elements is systematically barred in the Venetan dialects, in which the doubled DP must be a topic as shown in (6).

Notice that the restriction is relaxed if the subject is a complex wh, e.g., which + DP. It is well known that complex wh elements have a different syntax as they may co-occur with preverbal subjects, whereas bare wh elements tend to occur immediately before the verb.

5. Dummies

In many northern Italian dialects, some subject clitics are either missing or

syncretic, i.e., different bundles of person and number features are externalized by the same exponent, e.g.,

a in the dialect of Olivone in

Table 2. The gaps and syncretisms are illustrated in

Table 2.

Gaps and syncretisms are sensitive to person. Previous studies on Italo-Romance revealed some robust trends, e.g., if a variety has at least one subject clitic, it is 2sg; if a variety has two subject clitics, they are 2sg and 3sg; if a variety has three subject clitics, they are 2sg, 3sg, and 3pl (

Renzi and Vanelli 1983). Theoretical works tried to formulate higher-grade generalizations by modeling person features (

Heap 2002;

Cabredo Hofherr 2004 ;

Benincà and Poletto 2005;

Oliviéri 2011;

Calabrese 2011). Clitic inventories, however, are likely governed by principles of externalization, rather than principles of narrow syntax (they are ‘modes of PF externalization’ in

Roberts’ (

2014) terms). If we look beyond the kaleidoscope of externalization patterns, however, a solid distinction emerges from

Table 2 which might be symptomatic of a more general principle. As Calabrese 2011 points out, the dialects that are characterized by a complete set of clitics tend to exhibit

dummy clitics (i.e., uninflected forms) precisely in the same slots of the paradigm where clitics are missing in the other dialects. In

Table 2, for instance, the clitic

a in Olivonese and the clitic

i in Piveronese occur in the same cells of the paradigm in which the dialect of Verona displays no clitic.

The 1sg clitic is identical to the 1pl clitic in 80% of the dialects surveyed in

Manzini and Savoia (

2005). A total of 67% of the dialects have a single syncretic exponent for the 1sg, 1pl, and 2pl clitic. The 3pl clitic is involved in several patterns of syncretism, whereas the 3sg element is syncretic only with the 3pl one. Lastly, the 2sg pronoun, which is almost never missing, is involved in only two (very complex) patterns of syncretism. This situation is the mirror image of

Renzi and Vanelli’s (

1983) implicational statements about the distribution of gaps.

In

Figure 3, four types of systems are plotted, depending on whether the paradigm of subject clitics is characterized by gaps and/or syncretisms: the inner dot signals if clitics are missing (purple) or not (yellow), while the outer circle indicates if the attested clitics are dummies (i.e., identical exponents, purple) or not (yellow).

The map shows that, with a few exceptions, gaps and syncretism are in complementary distribution: syncretic dummies are in fact attested in the dialects with a full array of subject clitics. Complementary distribution means that gaps and syncretism can be regarded as two faces of the same coin or, theoretically speaking, that both may result from a single binary parameter establishing whether a language allows gaps or not. If a language cannot admit gaps, then dummies must be merged when a dedicated pronominal form is missing for historical reasons. Hence, besides the multitude of paradigmatic arrays (which nonetheless exhibit some regularities), a more general constraint can be detected that, with fewer exceptions, distinguishes dialects with or without a full array of subject clitics.

This further parameter distinguishes two (discontinuous) linguistic areas: the area in which gaps are allowed includes eastern Lombard, Venetan, and southern Ligurian dialects and Gallo-Romance dialects spoken at the Italy/France border (on Occitan, see

Oliviéri et al. 2020); the area exhibiting dummies includes Piedmont, Emilia-Romagna, Friuli, and western Liguria. This distinction partially overlaps with the syntactic isoglosses discussed in

Section 3 and

Section 4.

6. Quantitative Analysis

Three properties of subject clitics have been examined so far:

Doubling, i.e., whether the wh element meaning ‘who’ is doubled by a subject clitic or not;

Expletives, i.e., whether weather verbs occur with a subject clitic or not;

Gaps and dummies, i.e., whether languages allow gaps or dummies (for the sake of simplicity, from now on the analysis of gaps and dummies will be conducted in the first person singular for reasons that will be clarified in

Section 7).

The maps in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show that these properties tend to covariate. However, to prove that associations are statistically significant, the above properties were examined pairwise, and associations were confirmed by means of chi-square tests

The association between gaps and expletives was tested first. The number of dialects exhibiting gaps and/or expletives in our dataset is reported in

Table 3. The chi-square statistic with Yates correction is 14.4885. The p-value is 0.000141, which means that the association between gaps and expletives is significant at

p < 0.05. The data in

Table 3 confirm the impressionistic observation that the incidence of gaps is higher in languages that do not display expletives. An anonymous reviewer noticed that it is surprising that, notwithstanding the above conclusion, so many varieties with gaps have expletives (100 out of 147). However, it is worth noting that dialects with expletives are over-represented in the dataset for historical reasons that are not relevant here. With an unbalanced sample, what really matters is that the probability of finding expletives is much lower in dialects without the 1sg clitics (100 out of 147) than in dialects with 1sg (129 out of 133).

The second association that is put at proof is the one between expletives (with weather verbs) and doubling (of the subject

who), see

Table 4. The association is statistically significant (the chi-square statistic is 9.0933 and the p-value 0.002565 is significant at p < 0.05), showing that expletives are more likely to occur in languages with generalized doubling and vice versa.

The third association is the one between doubling and gaps. The data, summarized in

Table 5, are not statistically significant (the chi-square statistic is 0.9159, but the p-value of 0.338567 is not significant at p < 0.05.)

To summarize, the chi-square tests confirm that gaps are (negatively) associated with expletives. This result confirms

Renzi and Vanelli’s (

1983) empirical findings and, from a theoretical standpoint, it is an expected result. In fact, dummies can be regarded as expletives of a special kind that are merged in personal clauses when etymological clitic forms are missing.

In turn, expletives are positively associated with doubling; in fact, doubling is rarely found in languages without expletives. Lastly, no direct association is found between the paradigmatic structure of clitics (i.e., gaps and syncretism) and doubling. Associations are schematized in (10).

| (10) | gaps/dummies | ↔ | expletives | ↔ | doubling |

In addition to statistics,

Garzonio and Poletto (

2018) suggest that associations between syntactic variables can be tentatively established on the basis of syntactic isoglosses. In particular, they argue that when the area of diffusion of phenomenon A is contained in the area of diffusion of phenomenon B, then one can conclude that “the phenomenon that is more largely represented is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the occurrence of the second”.

For ease of comparison, the maps in

Figure 4 summarize the geographic distribution of the syntactic variables under examination. The contrast between dialects with gaps vs. dummies is represented in

Figure 4c with a map showing the presence/absence of subject clitics in the first person singular. The maps show a relationship of inclusion: if we focus on purple dots, we can see that dialects with expletives in

Figure 4a are more largely represented than dialects allowing doubling (in

Figure 4b) and subject clitic forms at the first person singular (in

Figure 4c). Then, in Garzonio and Poletto’s terms, expletives are a necessary but not sufficient condition for doubling and the occurrence of dummies, a conclusion that is in line with the generalization in (10).

Statistical and geolinguistic analyses converge to show that, behind superficial microvariation, Italo-Romance dialects cluster around two main prototypes, distinguished by a single pivotal property (having expletives), which is in turn associated with two other “secondary” properties: having dummies and exhibiting generalized doubling. Both dummies and doublers can be subsumed under a wide notion of ‘expletive’, encompassing not only expletive subject clitics stricto sensu (i.e., those appearing in impersonal constructions), but also the invariable clitic form that occurs in personal constructions (e.g., at the 1sg, 1pl, 2pl) and, by extension, the subject clitics that double operator subjects. Given this state of affairs, northern Italian dialects tend to fall into two idealized macro-types:

Type A languages where subject clitics are always mandatory, regardless of the thematic status, nature, and person of the subject;

Type B languages in which subject clitics are missing under certain conditions, e.g., non-thematic predicates, with certain persons, or with operator-like subjects.

This is precisely the situation that is predicted by a model of UG in which micro and macroparameters co-exist. Following remarks by

Baker (

2008),

Roberts (

2014, p. 186) argues that “combining macroparameters and microparameters, we expect to find a bimodal distribution: languages should tend to cluster around one type or another, with a certain amount of noise and a few outliers from either one of the principal patterns.” In fact, the amount of noise in our dataset is relatively high because the languages under examination are closely-related dialects and, as a consequence, microparametric effects tend to hide macroparametric choices such as the one distinguishing Type A from Type B languages.

Before modeling the distinction between Type A and Type B languages,

Section 7 offers some data concerning the association between the syntactic properties examined so far and verbal inflection, which is often regarded as a key factor in the emergence (or loss) of subject clitics.

7. The Role of Verbal Inflection

The relationship between the richness of verbal inflection, the syntax of subject clitics, and the licensing of null subjects have been debated since the 19th century (

Meyer-Lübke 1895; within the generative framework, see

Perlmutter 1971;

Taraldsen 1980; on northern Italo-Romance, see

Roberts 2014). Despite long-continuing research on the topic, however, the relationship between verbal morphology and the syntax of subject clitics remains elusive.

This section aims to tackle this problem from a quantitative point of view, by examining the distribution of the syntactic variables discussed in

Section 4 and

Section 5 (namely the presence of expletives and dummies) and two groups of languages exhibiting poor or rich agreement.

3As for syntactic variables, the 186 languages examined by

Manzini and Savoia (

2005) were organized into three groups: dialects exhibiting both expletives and dummies; dialects exhibiting either expletives or dummies; and dialects exhibiting neither expletives nor dummies. The three groups are plotted on the X-axis of

Figure 5.

The two lines in

Figure 5 represent the incidence of dialects with poor and rich inflection (I keep using this intuitive terminology), which was calculated on the basis of the number of distinctive endings in the paradigm of the present indicative of regular verbs. Agreement endings, however, are not the only way in which person distinctions are encoded in the verbal system. In fact, both regular and irregular verbs show systematic patterns of stem allomorphy and suppletion that set apart 1pl and 2pl forms, where stress shifts to the thematic vowel preceding inflectional endings. Since root allomorphy in the verbal paradigm is a trait that the Romance languages have inherited from Latin, 1pl and 2pl verbs are (and have always been) also clearly distinguishable from the rest of the paradigm in dialects with ‘poor’ inflection. For this reason, 1pl and 2pl verbs were discarded. In drawing the distinction between poor and rich inflectional systems, I focused on the number of contrasts within a four cell sub-paradigm including the three persons of the singular and the third person of the plural. Languages with poor inflection range from 0 contrasts (meaning that all four forms have identical exponence) to 1, whereas languages with rich inflection range from 2 to 3 (3 means that all four forms are different). The incidence of dialects with poor/rich inflection is plotted on the Y-axis of

Figure 5. The data in

Table 6 shows the number of dialects with poor/rich inflection in each of the three groups that are identified on the basis of syntactic variables.

The data in

Table 6, after being translated into percentages, were plotted in

Figure 5, which shows a clear correlation between syntactic and morphological factors: the incidence of expletives and/or dummies is higher in languages with poor inflection (blue line) and, vice versa, subject clitics are missing, under the appropriate syntactic conditions, in languages with rich inflection (orange line).

To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time that the correlation between verbal agreement morphology and subject clitic syntax is proved on the basis of solid quantitative data. Some theoretical consequences of the findings presented in

Section 6 and

Section 7 will be explored in

Section 8,

Section 9 and

Section 10.

8. Expletive Clitics and the Extended Projection Principle

It is a widely held view that subject clitics are merged with the I(nflectional) head, although there is no consensus regarding the nature of the dependency established between I and subject clitics: Are clitics probed by I? Do they carry a D feature? Is I endowed with an EPP in all languages with subject clitics?

Since the distinction between Type A and Type B languages regards the degree of obligatoriness of subject clitics, it is tempting to account for the observed variation by parametrizing the Extended Projection Principle (EPP, i.e., the requirement that every sentence must have a subject). The EPP requirement is normally satisfied by raising a D(eterminer) Phrase (DP) to the specifier of I, but in languages such as French and Italo-Romance dialects, the requirement is arguably fulfilled by subject clitics, which, syntactically, can be read as either heads or phrases (more on this in

Section 9).

As for null subject languages such as Italian, the role and existence of an EPP requirement have been largely debated, but, since the earliest formulations of the Null Subject Parameter (see

Rizzi 1982), it has been proposed that in languages such as Spanish or Italian, the verbal agreement (Agr) is sufficiently “rich” to satisfy the EPP. In minimalist terms, the relationship between Agr and the EPP can be modeled in two ways (see

Holmberg 2005):

Hypothesis 1. Agr is interpretable (Alexiadou and Anagnostopoulou 1998), it can absorb theta-roles and/or satisfy the EPP; preverbal subjects do not move to satisfy the EPP but for information-structural reasons. Hypothesis 2. Agr is uninterpretable (see Holmberg 2005), the EPP is satisfied by a pronoun that can be deleted under appropriate conditions, i.e., if it is probed by rich I/Arg; preverbal subjects and overt expletives are merged with I to satisfy the EPP; null and explicit subjects (including expletives) are therefore in complementary distribution. It seems to me that evidence from subject clitics brings support to Hypothesis 1. First, expletive subject clitics in Type A dialects show that the EPP can be satisfied by heads. This is an implicit assumption under Hypothesis 1, whereas Hypothesis 2 makes no specific prediction in this sense. By assuming that the EPP can be satisfied by heads, we can model the variation in Italo-Romance by arguing that the EPP can be satisfied by either Agr or D heads, namely subject clitics. Then, the distinction between northern Italo-Romance (Type A and Type B) and the rest of the Italo-Romance varieties (which do not exhibit subject clitics) can be parametrized as shown in

Table 7. In Type A dialects, the EPP is satisfied by D, which is generalized in all contexts. In Type B languages, Agr can satisfy the EPP, but SCLs and Agr work in tandem to satisfy the theta criterion, thus triggering the occurrence of referential (but not expletive) subject clitics for certain combinations of phi features. In the other Italo-Romance dialects, as in standard Italian, Agr is sufficiently “rich” to satisfy both the EPP and the theta criterion.

9. Expletive Clitics and the Representation of Clitic Dependencies

This section aims to compare two alternative analyses of subject clitics in light of the data discussed in

Section 3,

Section 4,

Section 5 and

Section 6. The two specific models that are compared here are recent reformulations of two competing approaches distinguishing ‘movement’ from ‘base-generation’ accounts.

Roberts (

2010) revives the movement analysis of clitics. Head movement, including clitic climbing, is regarded as an epiphenomenon: clitic heads spell-out agreement features on a probe (I in the case of subject clitics), while the matching goal at the foot of the agree chain is deleted. In particular, subject clitics are an extra bundle of phi features resulting from the agreement relation established between I and a deficient pronominal subject. The deletion of the latter gives the impression that the clitic has been moved from an argument position. Roberts does not develop a thorough analysis of expletive subject clitics, but he contends that, as a corollary of his theory, cliticization to a probe is in principle incompatible with an EPP feature on the same probe (

Roberts 2010, p. 32). He then argues that northern Italo-Romance dialects have an EPP requirement on I (

Roberts 2010, p. 103), but no conclusive analysis of expletive subject clitics is advanced, “owing to the general difficulty of deciding whether subject clitics in these varieties are pronouns or a manifestation of uninterpretable φ-features”. In fact, to account for the bona fide expletives in Roberts’ model, one needs to postulate that certain clitics are actually weak pronouns, which is the customary analysis of subject clitics in Gallo-Romance non-null subject languages (see

Section 10). However, this analysis cannot account for Type A languages, i.e., bona fide null subject languages with clitic expletives.

An alternative analysis of cliticization, which revives base-generation accounts of clitics, is offered by

Manzini and Pescarini (

forthcoming). They claim that subject clitics are first merged with I—more precisely, they are pair-merged with I—in order to satisfy the EPP; subject clitics may receive a referential reading when an unsaturated thematic role “accrues to them via predication”. In this view, all northern Italo-Romance (and Gallo-Romance) languages are regarded as EPP languages and no ad hoc distinction between weak pronouns and bundles of φ-features is invoked. In Manzini and Pescarini’s view, however, the distinction between Type A and Type B cannot be predicted. In particular, their model runs into difficulties in accounting for Type B languages in which subject clitics are found only/mainly in thematic environments. If subject clitics are merged exclusively to satisfy the EPP, then expletive clitics should be attested across the board in all dialects. To account for Type B languages, Manzini and Pescarini’s analysis should be modified along the lines proposed in

Table 7, by hypothesizing that in certain northern Italo-Romance dialects agreement can satisfy the EPP but cannot absorb theta-roles by itself, thus triggering the occurrence of referential (but not expletive) subject clitics.

In conclusion, evidence for expletive subject clitics can be accounted for within base generation accounts, while an analysis à la

Roberts (

2010), in which cliticization is reduced to agree, runs into difficulties.

10. Expletives and the Null Subject Parameter

The analysis of subject clitics relates to the debate around the so-called Null Subject Parameter (

Brandi and Cordin [1981] 1989;

Rizzi 1986). The null subject parameter, in its earliest formulation, was meant to account for the correlation between four syntactic properties: in addition to the presence of expletives and/or referential subjects, the parameter has cascading effects on other syntactic phenomena such as extraction and free inversion of subjects.

Gilligan (

1987) tested Rizzi’s early formulation of the Null Subject Parameter against a sample of one hundred languages, showing that the correlations between extraction, inversion, expletives, and null subjects are not bidirectional. Instead, only four one-way implications were confirmed, which, by transitivity, can be summarized as follows:

| (11) | a. | Free Inversion → subject extraction → no expletive |

| | b. | Referential null subjects → no expletive |

Notice that the status of expletive clitics in northern Italo-Romance dialects is quite controversial, as expletive subject clitics violate not only Rizzi’s theoretical formulation of the parameter but also Gilligan’s empirical generalizations. In fact, northern Italo-Romance dialects behave like null-subject languages (for instance, they allow inversion, cf. (12a)), yet some of them display clitic expletives as in (12b), apparently

contra (11).

| (12) | a. | al | g | ε | ruˈat | na ˈletera |

| | | 3sg.nom= | 3sg.dat= | aux.3sg | arrive.pst.ptcp | a letter |

| | | ‘A letter arrived to him’ (Albosaggia, Lombardy) |

| | b. | el | piof | | | |

| | | 3sg.nom= | rain.3sg | | | |

| | | ‘It rains’ | | | | |

Given (11) and (12), we either contend that northern Italo-Romance is typologically unparalleled or, more plausibly, we conclude that the null subject parameter and/or Gilligan’s generalizations regard only

phrasal expletives, which, in fact, are systematically barred in northern Italo-Romance. This amounts to saying that, even if subject clitics are involved in the EPP mechanism (see

Section 8), they are orthogonal to the phenomena associated with the null subject parameter.

Hence, since subject clitics are read as heads, they are inert to phrasal syntax. Phrasal subjects are therefore expected to occur with subject clitics, as is the case in northern Italo-Romance dialects. This, however, does not hold true for all types of subjects (cf.

Section 3) and all languages with subject clitics. In this respect, previous works on subject clitics have discussed at length the difference between northern Italo-Romance, where doubling is allowed, cf. (13a), and French, where doubling is barred, as in (13b), or can be better analyzed as a form of resumption. This holds particularly true in examples such as (13) which contain subjects that cannot naturally function as topics.

| (13) | a. | Nessuno | gli4 | ha | detto | nulla. (Florentine) |

| | | no-one | 3sg.nom= | aux.3sg | say.pst.ptcp | nothing |

| | b. | *Personne | il | n’ | a | rien | dit. (French) |

| | | no-one |

3sg.nom= | neg= | aux.3sg | nothing | say.pst.ptcp |

| | | ‘Nobody has said anything.’ |

As shown in

Section 3, however, variation in doubling is very nuanced (see also

Poletto 2000). It is worth recalling that in certain Italo-Romance dialects doubling (of third person subjects) can be better analyzed as a resumption of topicalized subjects (

Benincà and Poletto 2004, cf. (6)) as it is the case in standard French. At the same time, corpus studies have shown that in French varieties (i.e., sociolects), such as colloquial metropolitan French as well as in Quebec, Ontario, and Swiss varieties of French (see

Culbertson 2010;

Palasis 2015 and references therein), subject clitics and DP subjects (including strong pronouns) co-occur even if the latter are not left-dislocated. Given such a rich spectrum of variation, we can advocate a richer taxonomy of subject clitics, following the hypothesis that pronouns, and functional elements in general, have a layered inner structure (

Cardinaletti and Starke 1999;

Déchaine and Wiltschko 2002).

Instead, I would argue that variation with respect to doubling does not follow from inherent properties of clitic elements, but from the syntactic encoding of associate DP subjects. In this alternative explanation, clitic heads are inert to variation as witnessed by their occurrence in both null and non-null subject languages. Doubling would result from the availability of a dedicated discourse position, dubbed Subj(ect)P, that, unlike I, is not headed by a probe of agreement. SubjP hosts the

subject of predication (

Calabrese 1986), which does not necessarily correspond to the grammatical subject (experiencers and locatives can be subjects of predications) and does not correspond to the Topic position that is located in the left periphery, although the two are often mistaken (

Rizzi 2018).

In

Rizzi and Shlonsky’s (

2006) formulation of the Null Subject Parameter, SubjP accounts for the two prongs of the null subject conundrum: (a) the requirement of filling the subject position and (b) the impossibility of displacing the subject via extraction or inversion.

Rizzi and Shlonsky (

2006) argue that both conditions result from Criterial Freezing: SubjP is endowed with a Criterial Feature (corresponding to an EPP feature) attracting subjects (of predication). Extraction is therefore barred because subjects are frozen in the criterial position. In null subject languages, however, the Subject Criterion is satisfied by a null expletive (

pro), while overt subjects can be extracted, see (14).

| (14) | a. | Chi credi [che [pro Subj vincerà tchi]] |

| | b. | *Qui pensez-vous [que [qui Subj va gagner]] |

The crucial point of Rizzi and Shlonsky’s analysis is that the EPP is severed from the agree/case mechanism assumed in most minimalist analyses, including those briefly mentioned in

Section 8 and

Section 9. Further research will probably clarify the division of labor between probing and discourse heads in the licensing of (null) subjects. In this perspective, data concerning northern Italo-Romance expletives can bring compelling evidence for hybrid systems in which I’s uninterpretable features are valued by clitic heads, whereas doubled DPs can occur in an extra dedicated position such as SubjP. By modeling the Criterion endowed in SubjP, we will eventually be able to capture the fine-grained variation exhibited by Italo-Romance dialects with respect to doubling phenomena, cf. (13) and

Section 3. In a nutshell, the doubling of subjects can be reframed within a much more exhaustive explanation in which (micro)variation does not result from the inner (and invisible) structure of clitic heads, but the syntactic and pragmatic encoding of doubled phrasal constituents.

Before concluding, a brief remark is in order concerning the comparison between northern Italian dialects and

partial Null Subject Languages that, according to

Holmberg’s (

2005) analysis, lack a D(efinite)-feature in I. In these languages, e.g., Icelandic, overt subjects are not always required; the presence of overt subjects depends on person and control. At first sight, the distribution of null subjects in partial Null Subject Languages resembles that of Type B dialects, which show person-driven gaps and do not exhibit expletive subject clitics. Aside from this elusive resemblance, however, partial NS languages display some extra properties that northern Italo-Romance does not exhibit:

The subject pro-drop is sensitive to differences in clause type, main/embedded configuration, and register;

When the subject pro-drop is dependent on an antecedent (a ‘controller’), the controller needs to be strictly local;

There is a null third person singular inclusive generic pronoun.

Northern Italo-Romance languages do not exhibit the above properties: subject clitics are regularly found in both main and embedded clauses (save for certain wh clauses in Type B dialects, e.g., restrictive relatives) and null subjects always receive a definite interpretation (whereas the arbitrary interpretation is triggered by the clitic

se, as in the majority of the Romance languages). In

Holmberg’s (

2005) analysis, the definite reading of null subjects results from the presence of a D feature on I, which is lacking in partial NS languages such as Icelandic. This conclusion indirectly supports the hypothesis advanced in

Section 8 that Italo-Romance clitics are better analyzed as D heads (hence, goals of agreement), rather than bundles of φ-features.

11. Conclusions

This article examined a well-known domain of microvariation, i.e., the syntax of subject clitics in northern Italian dialects. I found that the kind of microvariation exhibited by northern Italian dialects is less kaleidoscopic than part of the recent literature suggests. In keeping with

Renzi and Vanelli (

1983), I showed that statistical analysis allows us to prove significant associations between syntactic variables such as the occurrence of subject clitics with non-dislocated subjects (e.g., the wh element

who); the occurrence of subject clitics with nonthematic predicates (e.g., weather verbs); and the occurrence of subject clitics in all persons of the paradigm. Chi-square tests showed that these properties are associated, thus indicating that, if microvariation could be factored out, Italo-Romance would display two main patterns: Type A dialects, where subject clitics occur across the board, and Type B dialects, where only referential subject clitics are attested.

I then elaborated on the possible theoretical interpretation of the dichotomy between Type A and Type B languages. Building on the hypothesis that the EPP is a universal requirement, I proposed that subject clitics are D heads first-merged with I (

Manzini and Pescarini, forthcoming) when a thematic role needs to be discharged (in Type B dialects) and/or to satisfy an EPP feature on I (in Type A languages). The distinction between Type A and Type B languages depends on the verbal agreement; subject clitic expletives tend to occur in languages with poor inflection, in which Agr cannot satisfy the EPP.

Concerning the status of phrasal subjects that, under certain conditions, co-occur with subject clitics, this paper offered no conclusive analysis. However, instead of focusing on the inner properties of clitic elements, I suggest that more attention has to be paid to the syntactic encoding of associated DPs, which are not necessarily displaced in the same syntactic position where the case/agreement mechanism takes place.

absence of doubling vs.

absence of doubling vs.  presence of doubling (squares: in clefts).

presence of doubling (squares: in clefts).

absence of doubling vs.

absence of doubling vs.  presence of doubling (squares: in clefts).

presence of doubling (squares: in clefts).

absence of expletives vs.

absence of expletives vs.  presence of expletives.

presence of expletives.

absence of expletives vs.

absence of expletives vs.  presence of expletives.

presence of expletives.

no gap, no dummy;

no gap, no dummy;  gaps, no dummy;

gaps, no dummy;  gaps and dummies;

gaps and dummies;  no gap, dummies.

no gap, dummies.

no gap, no dummy;

no gap, no dummy;  gaps, no dummy;

gaps, no dummy;  gaps and dummies;

gaps and dummies;  no gap, dummies.

no gap, dummies.