Abstract

Intonational plateaus exist in Chilean Spanish in contexts in which they do not exist in any other variety of Spanish. Mapudungun, which has been in contact with Chilean Spanish for centuries, also has plateaus in similar contexts, although for years, the possibility of any influence of Mapudungun on Spanish has been largely dismissed. The present study examines the discourse contexts in which intonational plateaus occur in both Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun and finds that their pragmatic function is similar, with the vast majority of cases highlighting information based on the subjective communicative desire of the speaker rather than falling into established syntactic or pragmatic categories such as narrow focus. However, while the pragmatic function is similar between the languages, Mapudungun has a wider use of the plateaus, indicating a likely longer presence in this language. Based on the similarities in pragmatic function, the absence of such plateaus in any other variety of Spanish, and the wider use of plateaus in Mapudungun, this paper argues that the Chilean Spanish plateaus originate from Mapudungun due to their centuries-long history of intense language contact.

Keywords:

Chilean Spanish; Mapudungun; intonation; plateaus; prosody; pragmatics; language contact; focus; highlighting 1. Introduction

Currently, only five surviving indigenous languages are spoken in Chile (Aymara, Quechua, Mapudungun, Rapa Nui, and Kawésqar), all of which are in different states of decline within Chile. Six others (Chango, Atacameño, Diaguita, Selk’nam, Yagán, and Chono) are extinct (Salas 2001). For decades, the idea that Chilean Spanish has been affected in any meaningful way by contact with Southern Cone Amerindian languages has been widely rejected, and arguments in favor of contact-induced change have been met with stiff resistance. Because of this opposition, and the subsequent relative rapid decline of Amerindian languages in Chile when compared to neighboring countries such as Peru and Bolivia, it is currently challenging to empirically prove (or disprove) any theory for or against the possibility that Chilean Spanish has been impacted or changed via contact with any indigenous language.

The most widely spoken Amerindian language in Chile is Mapudungun. Early on, Lenz (1893) claimed that Mapudungun had influenced much of the phonetic inventory of Chilean Spanish. However, subsequently, many linguists asserted that, besides lexical borrowings and toponyms, Mapudungun has had no notable influence on the Spanish of Chile (e.g., Alonso 1953; Lipski 2002; Salas 1992). Despite the lack of agreement among linguists, Alonso (1953) left room for the possibility that Mapudungun has had some influence on Chilean Spanish prosody. More recent studies (e.g., Sadowsky 2013; Sadowsky and Aninao 2013; Sadowsky 2020; Olate and Pineda 2021) assert that Mapudungun’s influence has been much more profound, demonstrating Mapudungun influence that has extended to subsystems, such as phonetics and morphosyntax, that the traditional language-contact literature has considered to be more resistant to contact-induced change than prosody (e.g., Silva-Corvalán 1994; Thomason and Kaufman 1988).

The present study examines the possible influence of contact with Mapudungun on an intonational phenomenon in Chilean Spanish, documented in detail in Rogers (2013, 2016, 2020b), who refers to it as an intonational plateau pattern. While intonational plateau patterns have been previously documented in Chilean Spanish and other dialects of Spanish, principally in different interrogative contexts (e.g., Armstrong 2010; Ortiz et al. 2010; Willis 2010), Chilean and Mapudungun intonational plateaus are different as they have been proposed to be a way that speakers extend focus to an entire idea or concept rather than a single lexical item or syllable (Rogers 2020a, 2020b). In both languages, plateaus have been shown to exhibit many similar behaviors at different prosodic, syntactic, and pragmatic levels. The present investigation, unlike previous studies on plateaus in both languages, further examines these patterns and their contact-induced origins primarily from a pragmatic lens. We propose that while Spanish intonational phonology does permit the production of plateaus, Mapudungun has contributed to Chilean Spanish the innovative pragmatic and prosodic device of extending emphasis and prosodic salience as well as highlighting varying quantities of information through these plateau patterns.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows: Section 2 covers the previous literature on the history of the Mapuche people, Mapudungun, and contact with Chilean culture, and Spanish, including DNA evidence indicative of prolonged cultural contact, as well as previous studies on Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish prosody and intonation; Section 3 summarizes data collection and analysis methods; Section 4 presents the results of the data analysis and describes the plateaus found in each language, their contexts and their possible pragmatic functions; Section 5 discusses the linguistic, and sociohistorical evidence that these patterns originated in Mapudungun, how they are possibly the result of the polysynthetic structure of the grammar of Mapudungun, and how they potentially were integrated into Chilean Spanish intonation through centuries of contact with the Mapuche people; and Section 6 concludes the study with a summary of the contribution of this research, its limitations, and possible future avenues of related inquiry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Mapuche

According to Bengoa (2004), archaeological evidence indicates the presence of the Mapuche, or “people of the/this land/Earth” (mapu ‘land/Earth’ + che ‘person/people’), in what is now Southern Chile and Argentina since around 500–600 B.C.E. Bengoa (2011) states that, prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the Mapuche lived in what he calls a “stateless society” (p. 93; translation ours) and lived relatively peacefully. When the Spanish arrived, they were able to subjugate most of the indigenous people living in what is contemporarily known as Northern and Central Chile, but they never conquered the Mapuche people as a whole nor the Mapuche heartlands (Richards 2013). Rather, they opted to negotiate with the Mapuche, with both groups eventually agreeing to establish that the Biobío River would be the official border between the Spanish and Mapuche territories (Bengoa 2011; Richards 2013).

During the fight for Chilean independence, despite centuries-long conflict with Spain, many Mapuche sided with Spain, largely due to the fact that Spain had generally respected previously established treaties (Richards 2013). After Chile gained its independence in 1818, there was a period of relative peace between the new Chilean nation and the Mapuche (Richards 2013); however, this fragile arrangement was short-lived, with the Chilean government electing to seize and incorporate Mapuche lands into the new Chilean state beginning in the mid-19th century (Olate et al. 2017). The Mapuche were relegated to reservations, commonly referred to as reducciones, and their traditional lands that had been seized were repurposed for urban and agricultural development (Richards 2013; Smeets 2008). Today, while accurate and reliable numbers regarding the Mapuche population are difficult to come by, many of the remaining speakers of Mapudungun, the Mapuche language, are bilingual, also speaking Spanish, and are rural farmers (Smeets 2008), although, in recent years, there has been a sharp increase of immigration to urban areas, especially Santiago (Sadowsky and Aninao 2019). Zúñiga and Olate (2017) state that Mapudungun is in an even greater state of sociolinguistic precarity than it was 10 years ago. Despite these potentially discouraging assertions and reports on the vitality of Mapudungun and its speakers, there have been a number of continued initiatives, both social and political, geared toward reviving Mapudungun and raising greater awareness of the language and its current situation, such as the formation of la Red por los Derechos Educativos y Lingüísticos de los Pueblos Indígenas de Chile or REDIB (The Network for the Educational and Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous People of Chile) in 2007, as well as the establishment of la Academia Nacional de la Lengua Mapuche (The National Academy of the Mapuche Language) in 2013. Additionally, during the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual revitalization initiatives such as workshops, online classes, and even meme pages in Mapudungun grew in popularity (e.g., Alvarado 2022).

2.2. Mapudungun: The Language of the Mapuche

2.2.1. History of Mapudungun

As has been the tendency with numerous Amerindian groups, the Mapuche have suffered significant discrimination over the centuries, which has helped contribute to a notable decline in the number of native Mapudungun speakers. The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (2015) states:

”The loss of Mapuche culture and language go hand in hand. While the older generations still converse in Mapudungun, many children do not learn their ancestral language as they are educated in Chilean schools where the curriculum is in Spanish. The Mapuche indigenous language is a language [of] resistance…which has led to a general loss of identity as some Mapuche youth come to consider themselves Chilean rather than Mapuche, especially because of the suffering endured due to widespread discrimination.”(p. 8)

Respecting language attitudes of Chileans toward Mapudungun, Salas (1992) indicates that in the vast majority of daily interactions, the preferred language between Chileans and the Mapuche has always been Spanish. He affirms that “La población no mapuche residente de La Araucanía ni habla ni entiende el mapudungu. No tiene necesidad de hacerlo, ya que, como componente mayoritario, vive en su mundo propio y puede prescindir de la sociedad mapuche e ignorarla” ‘The non-Mapuche population of La Araucanía does not speak or understand Mapudungun. There is no need for them to, given that, being the majority demographic, they live in their own world, and they can ignore Mapuche society’ (pp. 43–44, authors’ translation). However, according to Salas, the Mapuche do not have the same privilege of ignoring the monolingual Chilean population: “es la que impone, sin concesión alguna, las reglas de la interacción, entre otras, la de hablar castellano” ‘it imposes, without any concessions, the norms of interaction, which includes, among others, speaking Spanish’ (Salas 1992, p. 44, authors’ translation). Zúñiga and Olate (2017) report overall higher daily usage of Mapudungun by rural speakers than by urban speakers as well as greater levels of intergenerational transfer from parents to children in rural contexts than in urban sectors. Despite this, in both rural and urban areas, the authors report decreases in intergenerational transfer as well as usage and fluency from 2006–2016. While much of this is a consequence of the overall historical and contemporary dominance of Spanish in Chile, part of it is likely a result of longstanding general language attitudes toward those who speak Mapudungun. Salas (1992) states that bilinguals who are more dominant in Mapudungun than Spanish are generally received negatively by monolingual Spanish-speaking Chileans.

Over roughly the last century, these negative attitudes toward Mapudungun unfortunately influenced contact studies on Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun. As a result, for much of the 19th and 20th centuries there were not only limited studies on contact between Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish, but also a notable lack of general linguistic studies on Mapudungun.

2.2.2. Structure of Mapudungun

Typologically, Mapudungun is a polysynthetic agglutinating language (Smeets 2008; Zúñiga 2006; Zúñiga and Olate 2017; among others). Many linguistic studies on Mapudungun have focused on teaching and describing its grammar (e.g., Moesbach 1962; Catrileo 1987; Salas 1992; Zúñiga 2007; Smeets 2008). Of note, and relevant to any prosodic studies on the topic, is its highly complex verbal system, with most other derived word classes having a verbal base, and its lack of contrastive lexical stress. Verbs in Mapudungun all consist of a root which can be followed by derivational and/or inflectional suffixes (Smeets 2008), as seen in example (1). However, in most cases, Mapudungun verbs contain a number of morphemes attached to different “slots” that follow the root (Smeets 2008). These morphemes indicate an ample array of meanings such as location, movement toward or away from an object, mood, instrumentality, habituality, agent, recipient, beneficiary, etc. Example (2) illustrates the complexities of Mapudungun verbal morphology. Many verbs, both transitive and intransitive, can be turned into adjectives as well, as seen in example (3).

| (1) | Adümimi | |||

| Adüm | -i | -m | -i | |

| to understand | -indicative | -2nd person | -singular | |

| ‘You understand/understood’ | ||||

| (2) | Chillkatumekerparkeafiyiñ | ||

| Chillka- | -tu | -meke | |

| page/book | -verbalizer | -progressive | |

| -rpa | -rke | -a | |

| -cislocative | -evidential | -unrealized action | |

| -fiyiñ | |||

| -first person plural agent and third person dative subject | |||

| ‘We will be intensely studying it on the way here’ | |||

| (3) | Ti kutrankülechi che | ||||

| ti | kutran -küle | -chi | che | ||

| the | to be sick | -stative | -adjectivizer | person | |

| ‘the sick person’ | |||||

| Füta lladkükalu | |||||

| füta | lladkü | ka | -lu | ||

| big/old | to afflict/become sad | -continuative | -nominalizer | ||

| ‘the big/old afflicted/angry one’ | |||||

Very few studies have focused on prosody, and most that exist give only a brief overview of certain prosodic factors, such as stress. Mapudungun, unlike Spanish, lacks contrastive lexical stress. For example, the word kofke ‘bread’ can be pronounced as both [ˈkof.ke] and [kof.ˈke] without changing its meaning. However, Zúñiga (2007) asserts that in some cases, primary stress can change the pragmatic meaning of a word. For example, with the word chadi ‘salt’, according to Zúñiga, primary stress on the first syllable occurs primarily in declarative contexts, while stress on the final syllable occurs in interrogatives, as seen in example (4) from Zúñiga (2007, p. 65). It must be noted that it is unclear if this is an obligatory process for all nouns in declarative and interrogative contexts. Likewise, only one of Zúñiga’s (2007) informants exhibited this behavior, and thus, it cannot be considered a general prosodic behavior in Mapudungun.

| (4a) | Ngillamean CHAdi fewla. | |||||

| Ngilla | -me | -a | -n | chadi | fewla | |

| -to buy | -andative | -unrealized action | -1.ind sing | salt | now | |

| ‘I will go and buy salt now’. | ||||||

| (4b) | Ngelay chaDI tachi ruka mew? | |||||

| Nge | -la | -y | chadi | tachi | ruka | |

| -to be | -negation | -ind.3 sing | salt | this | house | |

| mew | ||||||

| in | ||||||

| ‘Is there not salt in the house?’ | ||||||

With regard to words with more than two syllables, Zúñiga (2007) states that the penultimate syllable has the tendency to attract primary stress if neither of the two final syllables is closed. In the case of longer polysyllabic words, a secondary accent is generally observed on one of the first two syllables, with preference being given to whichever ends in a consonant. However, Zúñiga (2007) emphasizes that these “rules” for accentuation in Mapudungun are not rigid, stating that just like in Spanish, Mapudungun accentuation can vary in real speech according to the specific syntactic and semantic context.

Molineaux (2017) shows evidence that the variability of stress corresponds with the limited agreement between native speakers as to which syllable is stressed (especially in vowel-final, disyllabic words), with participants indicating that words like ruka ‘house’ are correctly pronounced with stress being placed on either the first or last syllable. Despite this data, Molineaux claims that while the reason behind the disyllabic alternation of stress prominence in Mapudungun remains unknown, the phenomenon appears to be limited to words that end in open syllables. Molineaux (2018) examines Mapudungun stress both synchronically and diachronically and indicates that at the word level, there appears to be no real consistency with how Mapudungun speakers treat stress and concludes that Mapudungun might not place as much importance on the salience of speech rhythm and linguistic culminativity. Rather, it appears that Mapudungun shows a tendency to employ stress to highlight elements of its polysynthetic and agglutinative morphological structure and grammar. In other words, stress in Mapudungun becomes more systematic when the internal morphological structures of words are considered (Molineaux 2023). Thus one of the limits of the few studies on stress in Mapudungun, with the exception of Molineaux (2018, 2023), is that they tend to focus on uninflected nouns and other words that contain a limited amount of morphosyntactic agglutination.

There has yet to be an extensive study on Mapudungun intonation. Salas (2006) indicates that Mapudungun WH-questions tend to have an overall falling intonation, while Echeverría and Contreras (1965) state that interrogatives without WH-particles have a tendency to end in a rise. Likewise, Echeverría (1964) shows that declaratives end in a falling intonation. According to Echeverría and Contreras (1965), words preceding syntactic breaks can also end on a rise. While authors like Molineaux (2014) classify the intonation of Mapudungun as “uncontroversial”, more recently Retamal (2023) asserts that Mapudungun intonation is more difficult to document and untangle precisely due to the variability of stress placement. He illustrates this by showing examples of the same broad focus phrases with the lexical stress being placed on different syllables, which ultimately manipulates the shape of the fundamental frequency (F0) contour.

While intonational studies on Mapudungun are limited, Rogers (2020a, 2020b) documents the presence of intonational plateaus in both controlled and spontaneous Mapudungun. While no other studies show the same for Mapudungun, different types of intonational plateaus have been documented in other agglutinating languages, such as Guaraní (Clopper and Tonhauser 2011), Ki’che’ (Yasavul 2013), and Basque (Elordieta 2003), albeit in different pragmatic contexts than the Mapudungun plateaus documented in the current study and in Rogers (2020a, 2020b).

2.3. Contact between Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun

Early on, Lenz (1940) suggested that many of the phonetic particularities observed in Chilean Spanish were the result of contact-based influence from Mapudungun. Alonso (1953) describes Lenz’s theory as the dehispanization and araucanization of Chilean Spanish. Alonso (1953) strongly disregards any possibility that Mapudungun influenced Chilean Spanish and argues the phenomena that Lenz had observed in Chilean Spanish are the result of endogenous, or language-internal, language change. However, he does cede that Chilean Spanish prosody may contain Mapudungun influence.

Despite strong assertions from linguists, such as Alonso, that Mapudungun has had little influence on Chilean Spanish, more contemporary evidence indicates that there has traditionally been a high level of social and cultural contact between Chileans and the Mapuche. For example, according to the 2002 Chilean census, 87.3% of the Chilean population that reported having some degree of indigenous origin indicated that they had some level of Mapuche background (Comisión Nacional del XVII Censo de la Población y VI de Vivienda 2002). Likewise, studies have found high levels of Amerindian admixture in the Chilean population. Cruz-Coke and Moreno (1994) studied the nuclear DNA of male and female subjects from Santiago and Valparaiso. They not only report an elevated level of indigenous admixture but also show that this admixture increases in those that make up the middle and lower socioeconomic strata of both cities. In another study that used mitochondrial DNA, Rocco et al. (2002) show that 84% of the population of Santiago has varying levels of Amerindian mitochondrial DNA. Because Santiago is further north, the term “Amerindian” includes individuals of Atacameño and Aymara descent as well as Mapuche; however, Mapuche is the largest of the indigenous origins documented in the study. More recently, Eyheramendy et al. (2015) indicate that, similarly to Peru and Bolivia, Chileans show high levels of Indigenous heterogeneity and imply that due to historical factors and lower levels of immigration into the southern regions of Chile occupied principally by the Mapuche, levels of Mapuche admixture are likely higher in the south than in central Chile.

Despite traditional resistance to the idea of Mapudungun’s influence on Chilean Spanish, recent studies have found intriguing evidence of Mapudungun’s influence on deeper linguistic subsystems of Chilean Spanish. Sadowsky (2013, 2020) examined the Spanish vowels of 61 speakers from the city of Concepción and the Mapudungun vowel systems of 10 bilingual Mapudungun-Spanish speakers from Isla Huapi. He shows that the vowel space and distribution of Mapudungun are strikingly similar to those of speakers in Concepción. He hypothesizes that, while the Spanish vowel system of his speakers is phonologically Spanish in that it only has five vowel phonemes, the vowel quality of those vowels resembles those of Mapudungun, which echoes Lenz’s (1940) earlier claims. Sadowsky concludes that Chilean Spanish vowels may have undergone “rephonetization” as a result of influence from Mapudungun. Sadowsky and Aninao (2013) present evidence that historically intense contact in what are now largely monolingual Spanish-speaking communities in the south of Chile has resulted in a variety of Chilean Spanish frequently written off as “uneducated” and “incorrect,” sometimes referred to negatively as castellano mapuchizado ‘Mapuche Spanish’. They show evidence that contact between Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun may have resulted in a number of morphosyntactic features of Mapudungun (e.g., lack of subject-verb number agreement and grammatical gender) having potentially grammaticalized and perpetuated themselves in the monolingual Spanish of the province of Cautín. Likewise, Olate and Pineda (2021) found gender disagreement in the monolingual Spanish of several communities in Southern Chile and proposed that this is a code-copying process mapped onto the Spanish of these communities from Mapudungun, a language that lacks grammatical gender. Olate et al. (2022) provide additional documentation of Mapudungun’s evidential and negation influence on Chilean Spanish.

These findings are significant because morphosyntax is traditionally one of the deeper subsystems of language and has typically been considered to be more resistant to exogenous change in cases of maintained community bilingualism (e.g., Silva-Corvalán 1994; Thomason and Kaufman 1988; Van Coetsem 2000). However, Thomason and Kaufman (1988) also indicate that in situations of language shift, where a linguistic community replaces one language with another, changes to deeper linguistic subsystems are more common. If Mapudungun has indeed impacted the phonology and the morphosyntax of Chilean Spanish, then, given how intonation has been shown to be much more vulnerable to contact-induced change in situations of both long-term bilingualism as well as language shift (e.g., Alvord 2010; Gabriel and Kireva 2014; Grünke 2022; Hualde and Schwegler 2008; O’Rourke 2005; Simonet 2011), there is an ongoing possibility that evidence of language contact with Mapudungun can be found in the prosody of Chilean Spanish.

2.4. Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun Intonational Plateaus

Several studies have documented different aspects of Chilean Spanish intonation (e.g., Cepeda 1997; Cid Uribe and Ortiz-Lira 1998; Fuentes 2012; Ortiz et al. 2010; Silva-Corvalán 1983). Given that the focus of the current study is a specific type of intonational plateau pattern, a detailed discussion of Chilean intonation is beyond the scope of this paper. Different authors have documented a small number of intonational plateau patterns in different contexts; for example, Cid Uribe and Ortiz-Lira (1998) briefly mention a plateau pattern produced in some vocative contexts, while Ortiz et al. (2010) also show that a limited number of interrogatives in Chilean Spanish can be produced as plateaus.

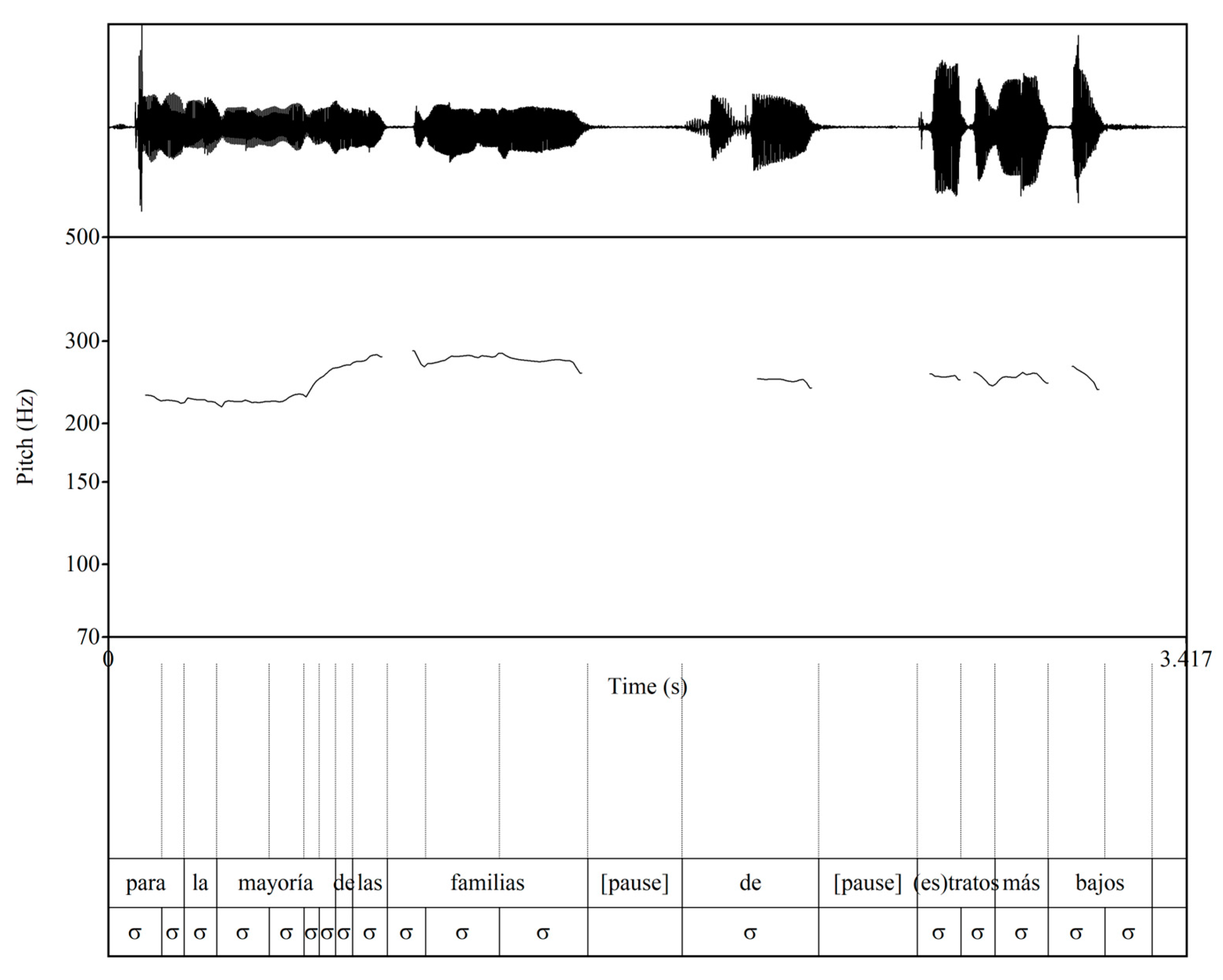

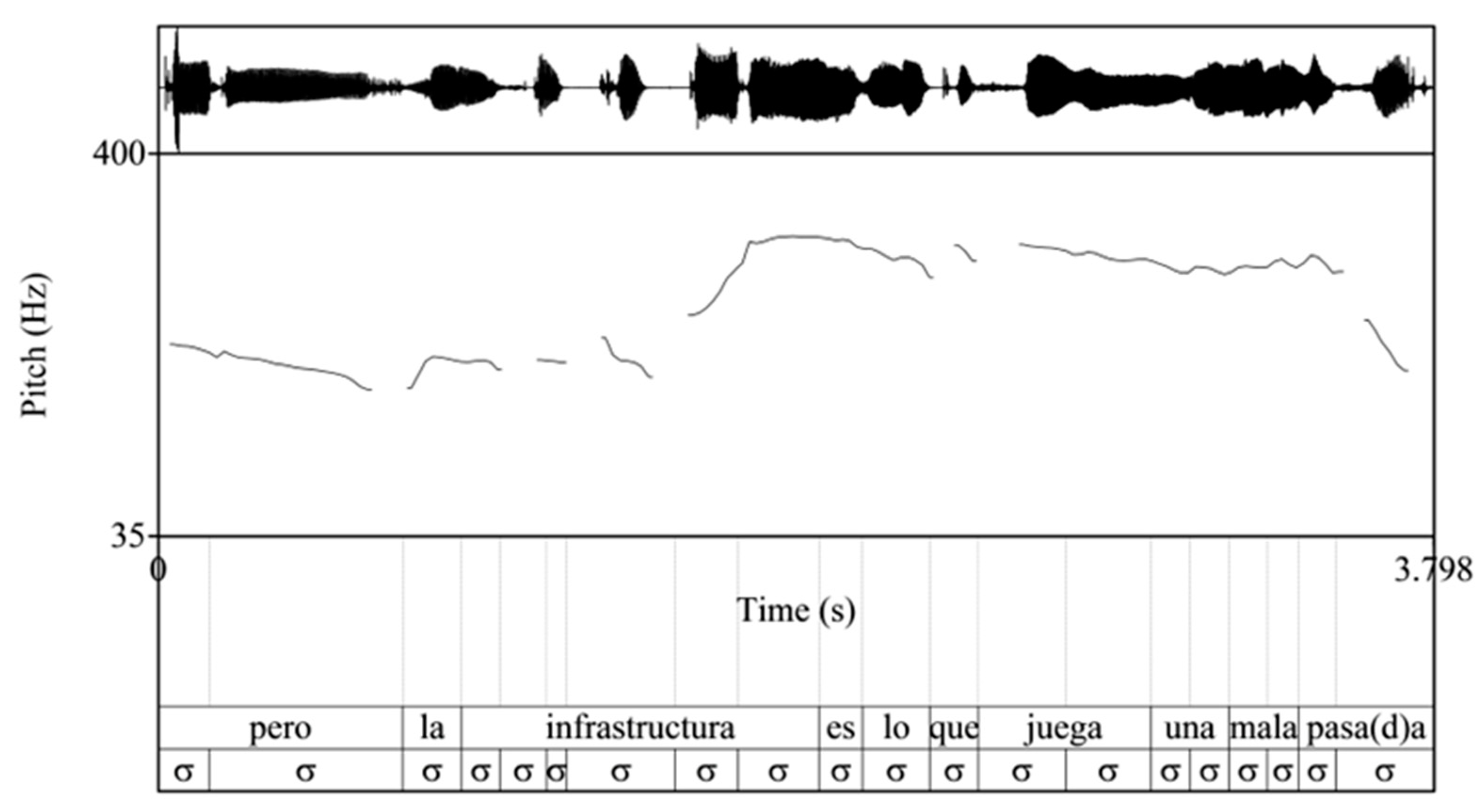

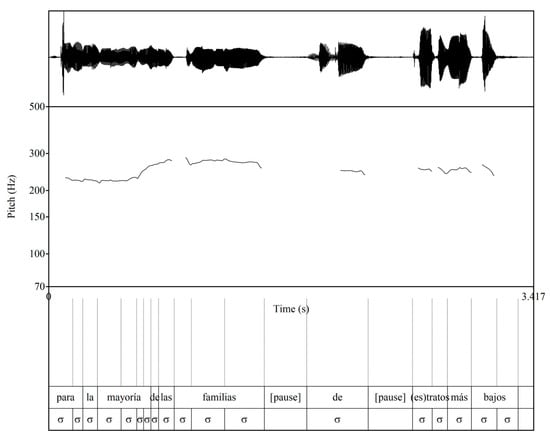

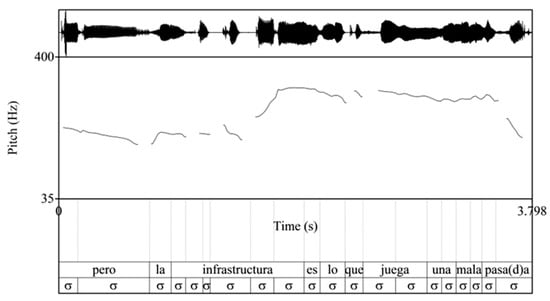

Rogers (2013, 2016) first described the Chilean Spanish intonational plateau patterns that we analyze in the current study as appearing in contexts that pragmatically resemble broad focus statements. In most cases, they are preceded by a low tonal valley in which all phonetic content is realized at the same low F0 register. The valleys are not always present, but when they are, they can be as short as a single syllable or may extend for multiple function and/or content words. The valleys end in an abrupt rise, usually on the stressed syllable of the final valley-internal word, although the rise can occur on unstressed syllables or function words. The rise continues to a higher pitch level, where the speaker maintains the high F0 for anywhere between two or three syllables to multiple stressed and unstressed words. Finally, the contour ends in a sudden descent. The phonetic content of these final descents can vary, and, in some cases, they can occur over multiple syllables and/or words. In other cases, the F0 rises above the plateau on the final stressed syllable and falls on all subsequent syllables. Most of these plateaus have been documented in utterance-final position, although they can also occur in utterance-internal contexts. Some plateau patterns extend for entire utterances. Hence, the size, phonetic content, and duration vary greatly and appear to be acutely related to the conversational goals and/or desires of speakers (Rogers 2013, 2020b). Figure 1 and Figure 2 are examples of the plateau patterns in Chilean Spanish.

Figure 1.

Plateau on the Chilean Spanish phrase para la mayoría de las familias de estratos más bajos ‘for the majority lower class families’.

Figure 2.

Plateau on the Chilean Spanish phrase pero la infraestructura es lo que juega una mala pasada ‘but what is unpredictable/dangerous is the infrastructure’.

Several attempts have been made to phonologically analyze these patterns from within the current Sp_ToBI and Autosegmental Metrical (AM) frameworks (Prieto and Roseano 2010), but none have come to what can be considered a meaningful consensus, suggesting that the proper phonological analysis has to be investigated outside of AM due to atypical behavior such as rising on non-prosodic content, high tonal maintenance over content not traditionally considered stressed, and the lack of pitch reset through breaks. Rogers (2013) proposes several AM-centered explanations, such as considering all tonal material in the low and high portions as either chains of monotonal pitch accents or deaccented material. Another proposal that Rogers (2013) puts forth is that the individual pitch accents do not create meaning in either the low or high portions but rather the entirety of each portion. In other words, both the low and high portions are single phonological tonal events. Rogers (2016) likewise offers several possible AM analyses of Chilean Spanish plateaus but ultimately concludes that the patterns present problems for the current Sp_ToBI and AM frameworks and indicates that a more speaker-centered, pragmatics-based approach would hold superior explanatory power. Finally, Rogers et al. (2020) propose that the high tonal portions could be a form of tonal compression. However, tonal compression cannot explain instances of “broken plateaus” attested by Rogers (2016), that continue through breaks, stuttering, pauses, and self-corrections without exhibiting pitch reset. While a phonological analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, Rogers’ (2016) suggestion to pursue a more speaker-centered, pragmatics-based approach drives the present study.

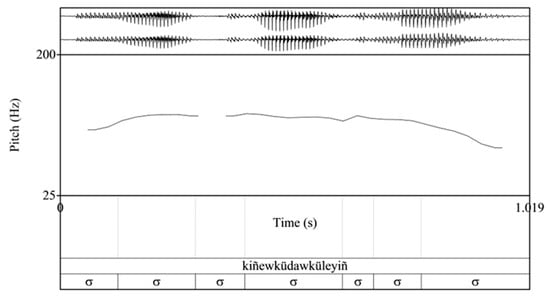

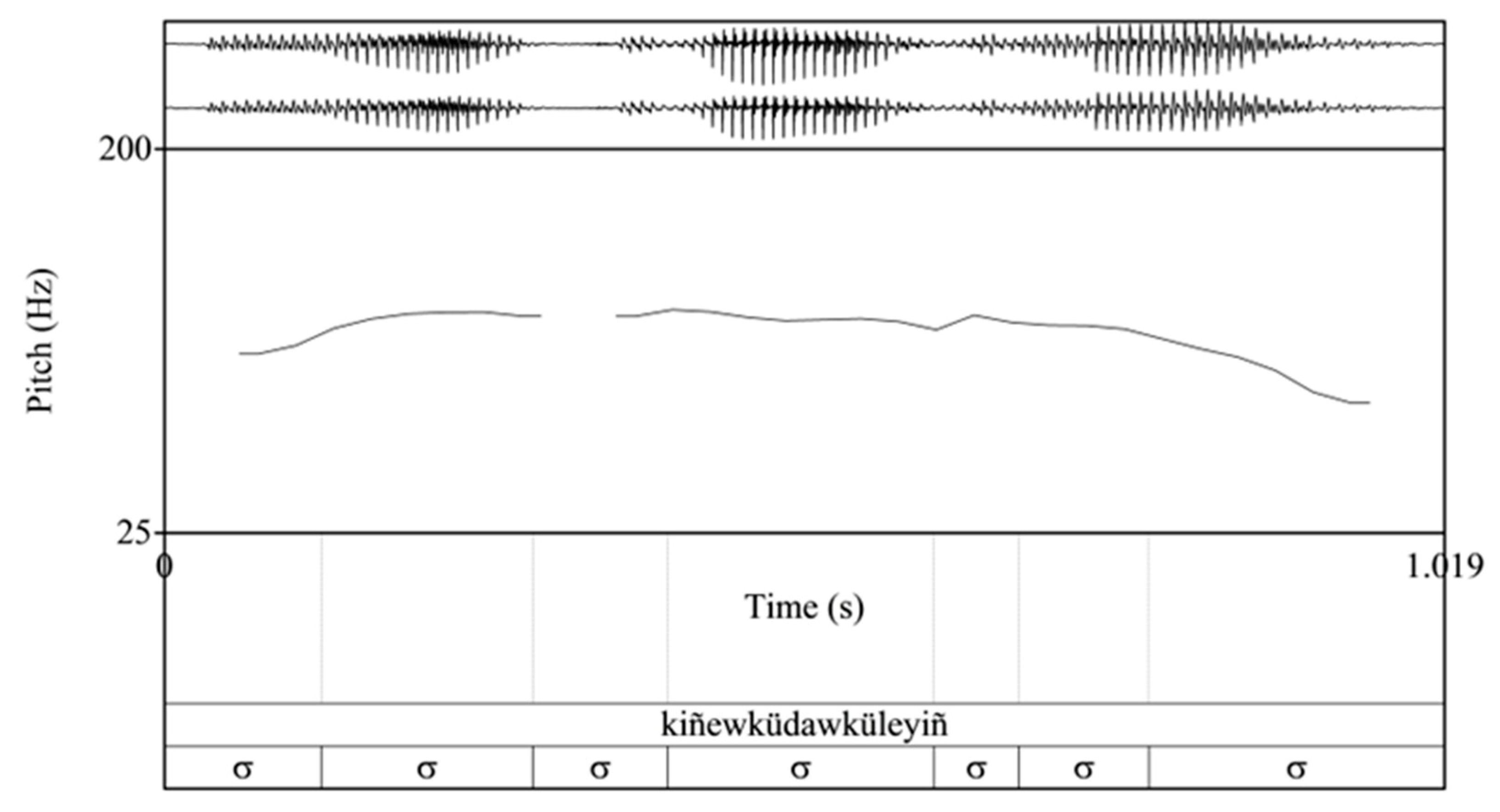

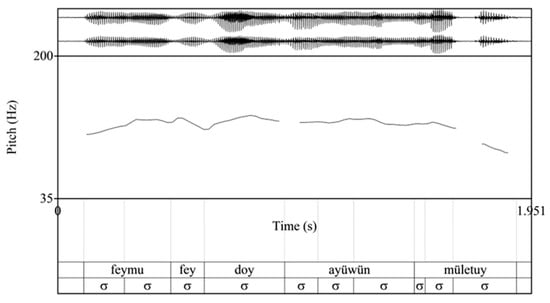

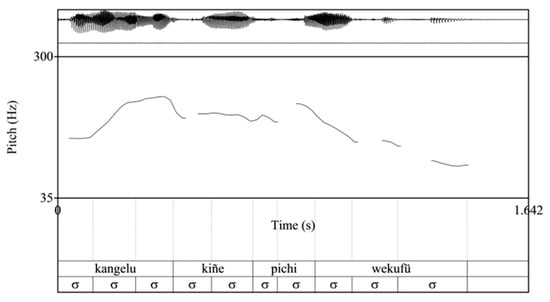

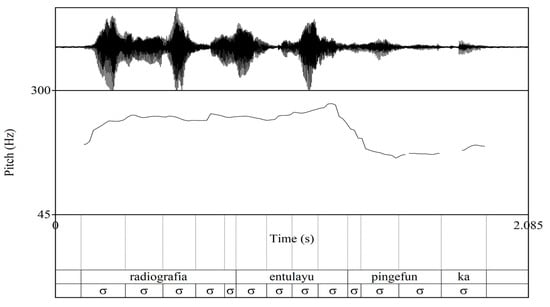

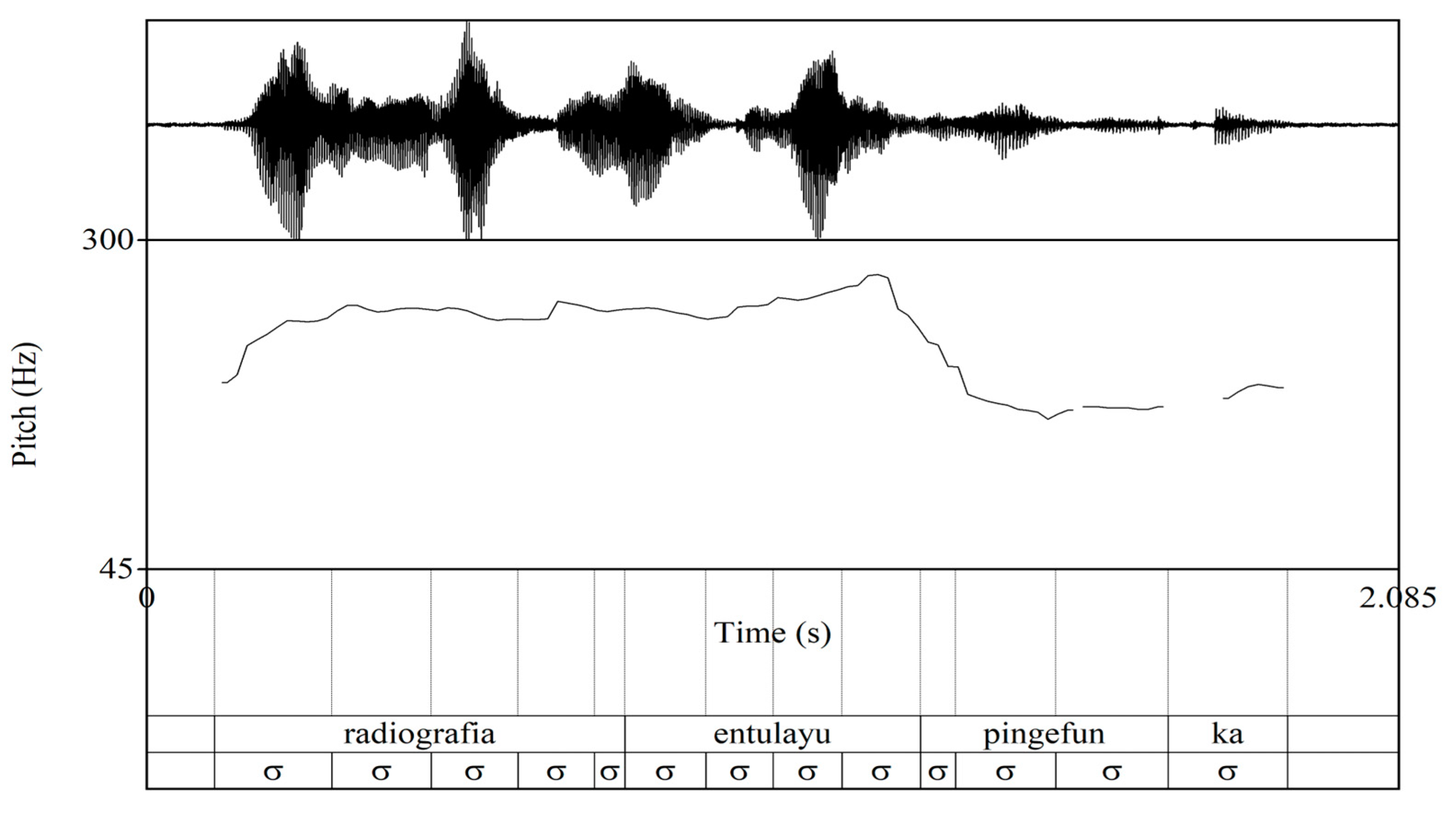

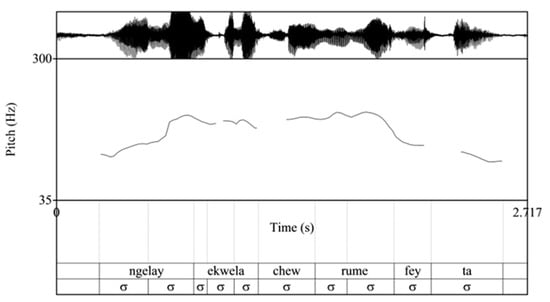

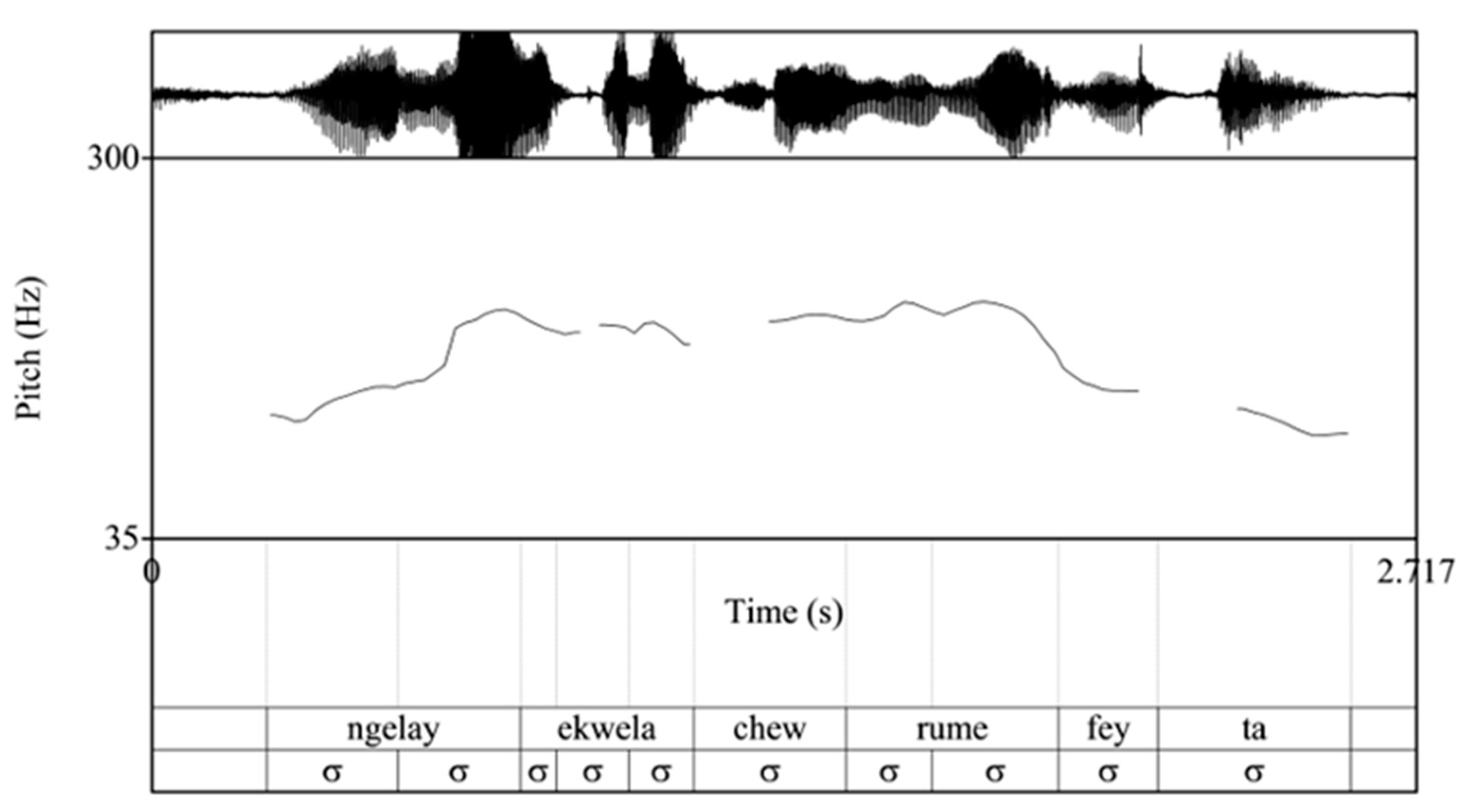

Rogers (2016, 2020b) documented similar intonational plateau patterns in Mapudungun. As has been described for Chilean Spanish, the patterns in Mapudungun also vary in their phonetic content and duration. Likewise, they often present information that appears to be broad focus in nature, and their content and duration appear to be similarly tied to the communicative desires of the interlocutors and conversational context. Rogers (2020b) hypothesizes that these patterns in both languages are a mechanism for speakers to extend focal salience across larger amounts of content rather than just highlighting single syllables or words. Figure 3 and Figure 4 are examples of intonational plateaus from Mapudungun.

Figure 3.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase kiñewküdawküleyiñ.

Figure 3.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase kiñewküdawküleyiñ.

| Kiñe | w | küdaw | -küle | -y | -iñ |

| one | -reflexive | -to work | -stative | -indicative | -3 pl |

| ‘We work together’ | |||||

Figure 4.

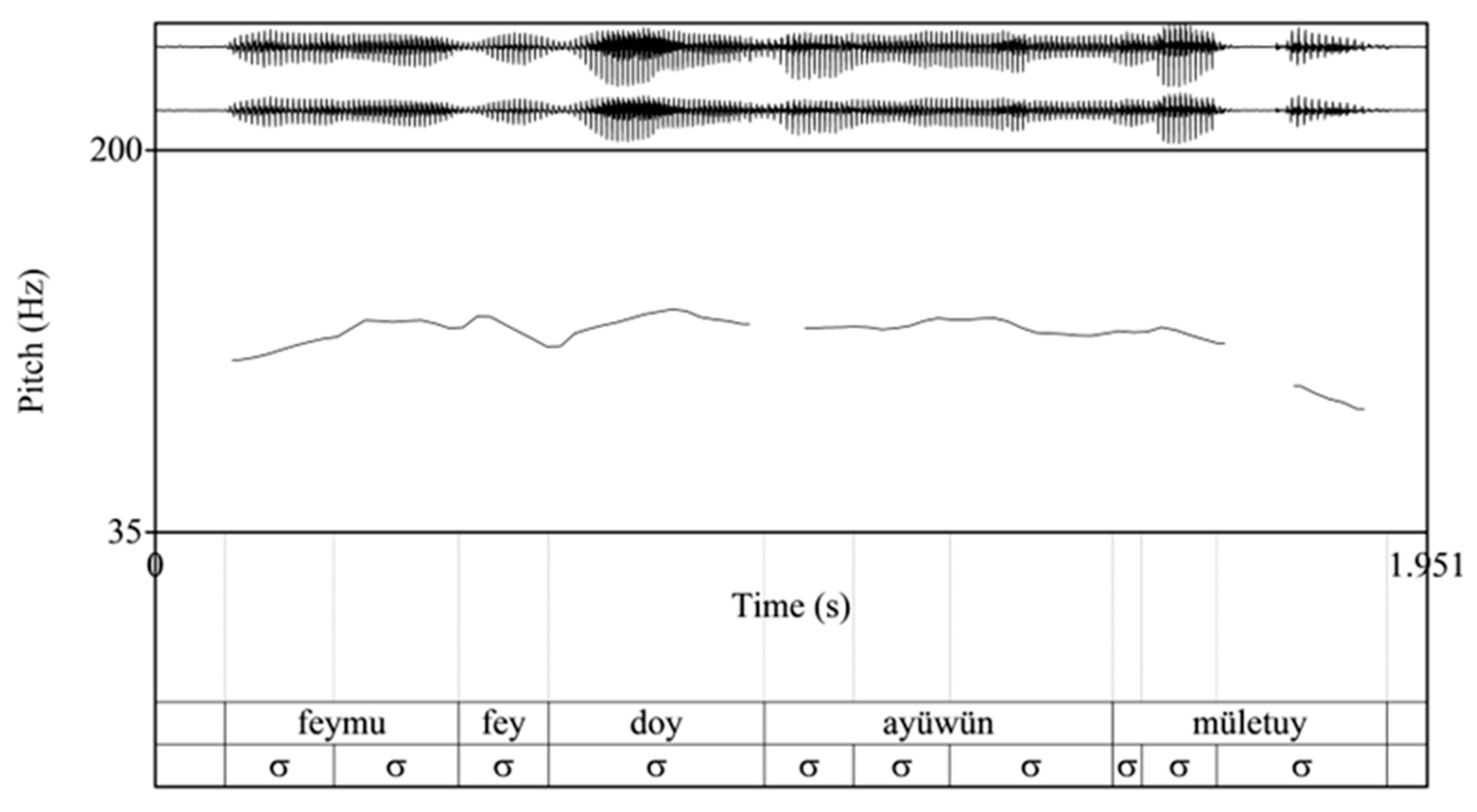

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase feymu fiy doy ayüwün muletuy.

Figure 4.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase feymu fiy doy ayüwün muletuy.

| feymu | fey | doy | ayü | -w | -ün |

| so | therefore | more | to love | reflexive -plain verbal noun | |

| müle | -tu | -y | |||

| to be | -restorative | -ind.3 pl | |||

| ‘Therefore, there is more happiness once again’ | |||||

The present study is part of an ongoing analysis of Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish intonational plateaus and their contact-induced origins and was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1: What are the pragmatic functions of Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun intonational plateaus in terms of the types of utterances in which they are used and the discourse meanings that they communicate?

RQ2: What information can be gleaned about the origins of the Chilean Spanish intonational plateaus, as either endogenous or resulting from contact with Mapudungun, from the similarities and differences in pragmatic functions of intonational plateaus in the two languages?

3. Methodology

The Chilean Spanish data was taken from a corpus of 70 sociolinguistic interviews conducted in the Biobío and Araucanía regions of Chile. Of the 70 interviews, a subset of 40 was analyzed. Of the 40 interviews, 34 were made in the cities of Talcahuano and Concepción and the surrounding neighborhoods of Villa San Pedro, Michaihue, Lomas Coloradas, Hualpen, Candelaria, and Boca Sur. The remaining six interviews were collected in Temuco at La Universidad de la Frontera (UFRO). Four of these speakers were from the Araucanía region, and two were from Santiago. None of the speakers speak Mapudungun. A total of 551 plateaus were coded and extracted from 40 interviews for an average of 13.78 plateaus per speaker. The interviews in and around Concepción and Talcahuano were recorded using a Marantz PMD660 digital recorder and a head-mounted microphone or a Fostex FR-2LE digital recorder with an Audix HT5 head-mounted microphone. These interviews were carried out in the participants’ homes, places of work, local churches, and municipal buildings. The Temuco data was collected using a Fostex FR-2LE digital recorder with an Audix HT5 head-mounted microphone in a recording room at UFRO. Speakers ranged from ages 18 to 55 and were from a variety of socioeconomic strata, ranging from low to upper-middle class.

The Mapudungun data was pulled from 4 different corpora. This is mostly due to the scarcity of recorded Mapudungun data. The four corpora were Zúñiga (2006), Smeets (2008), Olate (2015), and Caniupil et al. (2019). The Mapudungun data from Zúñiga (2006) consist of smaller audio clips the author recorded for his Mapudungun grammar book. Smeets (2008) recorded various sociolinguistic interviews with 4 Mapuche political refugees living in the Netherlands in the 1980s who had fled the military regime in Chile. Olate (2015) consists of a collection of informal interviews and recorded readings in Mapudungun. The largest corpus is Caniupil et al. (2019) and contains 142 h of recorded interviews with Mapudungun speakers from 3 different Mapuche groups: Pewenche, Nguluche, and Lafkenche. It must be noted that for the Zúñiga (2006) and Olate (2015) corpora, the data used was from a variety of speakers due to the fact that many of these clips were recorded as supplemental material for Mapudungun grammar books and for teaching Mapudungun. Smeets (2008) and Caniupil et al. (2019) consist of longer interviews with the speakers. Additionally, Caniupil et al. (2019) indicate that the interviews they conducted were done by Mapuche interviewers and that most of the interviews discussed traditional Mapuche health beliefs and experiences of individuals in both the Chilean health care system and through the lens of the Mapuche beliefs and customs regarding health and illness. Speakers are all native speakers of Mapudungun, although most are bilingual, which reflects the overall norms among contemporary Mapuche speakers in both Chile and Argentina. However, the creators of this corpus have not provided any data on the speakers other than gender. Thus, it is impossible to determine how many are bilingual and their exact ages. What can be said is that all of the interviews analyzed from the Caniupil et al. (2019) corpus contain various different types of codeswitching between Mapudungun and Spanish at different junctures, indicating that most, if not all, the speakers included in the current study exist along a continuum of Mapudungun/Spanish bilingualism. The interviews were conducted using a Sony DAT TCD-D8 recorder (48 kHz) and Sony DCM-E70P digital stereo microphone, and speakers range from 16 to 100 years of age (Duan et al. 2020). For the current study, 201 plateaus were extracted and analyzed from the Mapudungun corpora from a total of 12 speakers, for an average of 16.75 plateaus per speaker per file. The glosses used for the Mapudungun data in the present study are based on Zúñiga’s (2007) and Smeets’ (2008) grammatical categorizations with slight modifications made by the authors.

The intonational plateaus extracted from both language corpora were identified through a combination of impressionistic and acoustic analyses. That is, they were identified by noting the aural contrast between the high portions and preceding low portions of the pitch contour and verifying in Praat a rise in F0 that was then sustained. All rises to plateaus were far above the 7 Hz threshold that has been used as the minimum to be considered a rise in previous studies (e.g., Willis 2003; O’Rourke 2006; Rao 2009; see O’Rourke 2006 for an explanation of how this threshold was determined) and often exceeded 100 Hz and even 200 Hz in speakers with large pitch ranges.

As previously mentioned, the current study is part of an ongoing series of inquiries into the functions of the intonational plateau in both Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish. Given that one of the research questions deals with the possibility of the Chilean Spanish plateaus entering the language through contact with Mapudungun, it was deemed necessary to verify that the plateaus in the two languages are similar prior to investigating their pragmatic functions. To this end, the duration of each plateau was measured in terms of the number of syllables contained, and the preceding and following prosodic contexts were identified. In this way, it could be determined whether the plateaus are similar in size and context of use, providing further insight into the possible relatedness of the plateaus in the two languages regardless of any similarities or differences in their pragmatic functions. With respect to the preceding and following prosodic contexts, it was noted whether each plateau was preceded and followed by an utterance-final pause, a prosodic phrase-final (but not utterance-final) pause, or continued discourse, with no break between preceding or following information and the plateau.

As Rogers (2020b) has hypothesized that the plateaus in both languages are used to mark focal prominence over an extended stretch of speech, the discourse contexts of the plateaus in the present study were examined to determine if they fit into established categories of focus. Specifically, contrastive and new information narrow focus were considered. A plateau was identified as communicating contrastive focus if the information directly contrasted with other information in the discourse, whether in the speech of the speaker or the interlocutor. A plateau was identified as communicating new information narrow focus if all of the content in the plateau was information that was new to the discourse. Other clear categories were observed in the data as well. These were yes/no questions, information-seeking questions, and direct discourse. Mapudungun does not have an equivalent of the conjunction that (que in Spanish) that introduces subordinated noun clauses. For example, if one were to say My friend told me that I was lazy, the construction in Mapudungun would be notably different. One strategy that Mapudungun employs in these contexts is direct discourse. In other words, speakers directly quote whatever was said to them, followed by a form of the verb pin ‘to say’ to indicate that what they said was information that another party communicated to them. When plateaus were used for such cases, they were categorized as direct discourse. Plateaus that did not fall into one of these established focal categories or the other clear categories seen in the data were labeled as other. In the case of plateaus in this ‘other’ category, the discourse contexts in which the plateaus occur were examined to determine possible contextual clues to the speakers’ motivations for their use, following Rogers’ (2013, 2020b) suggestion that use of the plateau is related to the subjective communicative desire of the speaker to highlight information. These possible contextual motivations were then examined to understand the pragmatic functions of the intonational plateaus and to compare their use in Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun.

4. Results

4.1. Prosodic Contexts of the Plateaus

The primary focus of this paper is on the meanings communicated by the plateaus, as evidenced through an examination of their pragmatic functions in their discourse contexts. However, given that the plateaus in question occur in both Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun, and a question of interest is whether the Chilean Spanish plateaus have their origin in Mapudungun through centuries of intense contact, it is relevant to first establish whether or not the plateaus in the two languages are comparable in terms of the prosodic contexts in which they occur. Results were obtained for both the preceding and following prosodic contexts and are presented in Table 1. Here, it can be seen that while there are some differences in the specifics–primarily that Mapudungun plateaus follow an utterance-final pause more often while Chilean Spanish plateaus show more balance between following utterance-final pauses and prosodic phrase-final pauses–the similarities are striking. Combining the two categories of pauses, we can see that both Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun plateaus follow a pause over 82% of the time. In addition, the plateaus in both languages precede a pause more than 93% of the time, with the vast majority of plateaus occurring at the end of an utterance.

Table 1.

Preceding and following prosodic contexts for the plateaus.

The results for the prosodic contexts in which the plateaus occur show that the Chilean Spanish plateaus and the Mapudungun plateaus are extremely similar to each other. These findings add to the similarities between the plateaus in the two languages reported by Rogers (2016, 2020b) and further motivate examining the similarities and differences between them in other aspects, such as in their pragmatic functions.

4.2. Chilean Spanish Plateaus and Their Pragmatic Functions

Table 2 presents the categories into which the 551 Chilean Spanish plateaus fall. As can be seen in the table, about 19% of the plateaus fall into one of the narrow focus categories, either contrastive focus or new information focus, with a higher percentage marking contrastive as opposed to new information focus. Approximately 1% fall into other established categories (i.e., direct discourse and yes/no questions). That leaves just over 80% of the plateaus in the ‘other’ category. Given that Rogers (2013, 2020b) suggests that the plateaus are related to the subjective communicative desires of speakers to highlight information, we conducted an analysis of the context surrounding the content communicated in intonational plateaus in order to gain insight into the reasons that a speaker might want to highlight the information produced with the plateau. Throughout this section, we will look at several examples of content produced with an intonational plateau and note the reasons for highlighting content that can be gleaned from the context of the surrounding discourse. As there is only one plateau used in a question, and therefore no possibility of examining the pragmatic function of plateaus within Chilean Spanish questions, we focus on the pragmatic function of plateaus in declaratives and do not examine the lone question.

Table 2.

Classification of Chilean Spanish plateaus by pragmatic function.

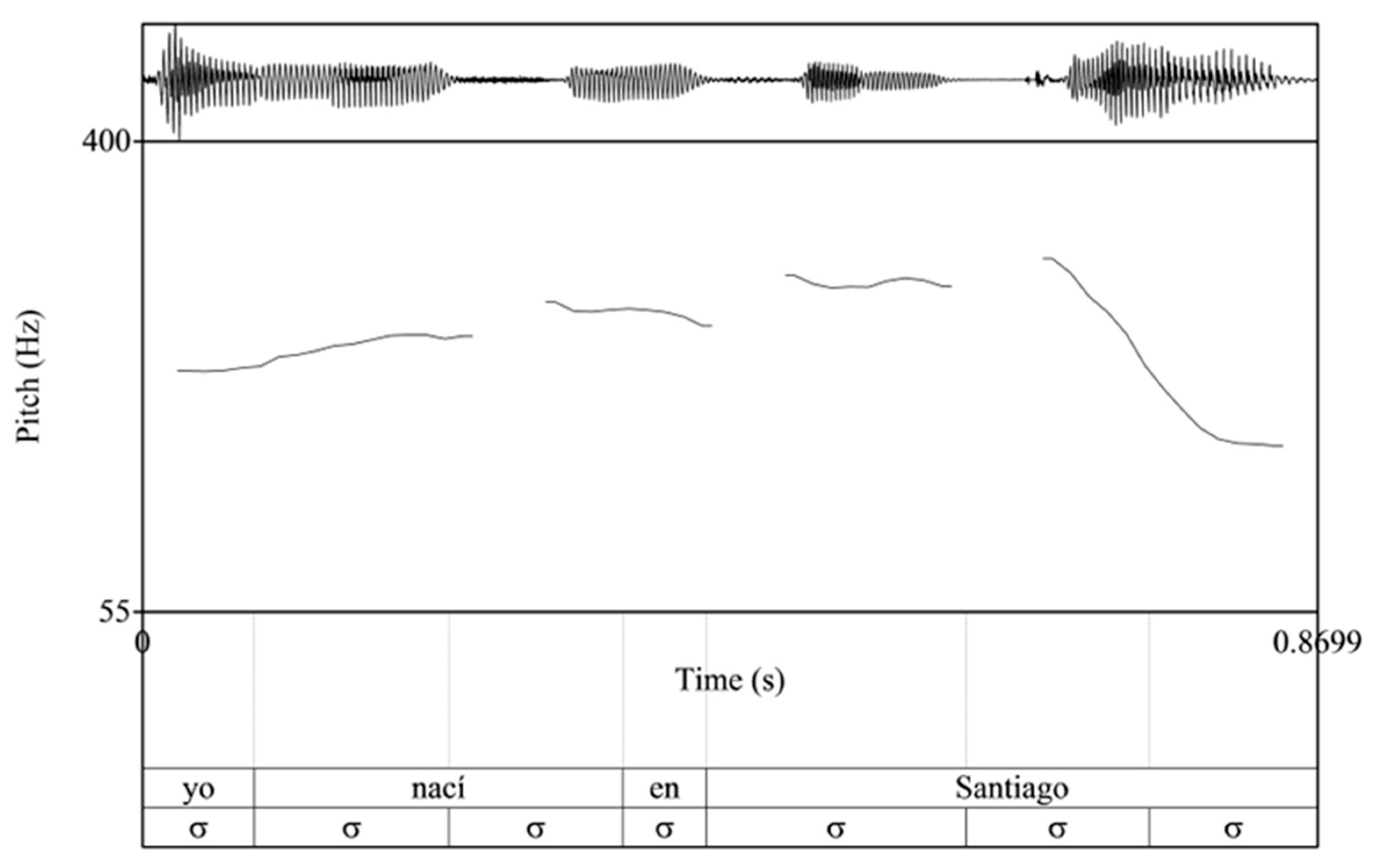

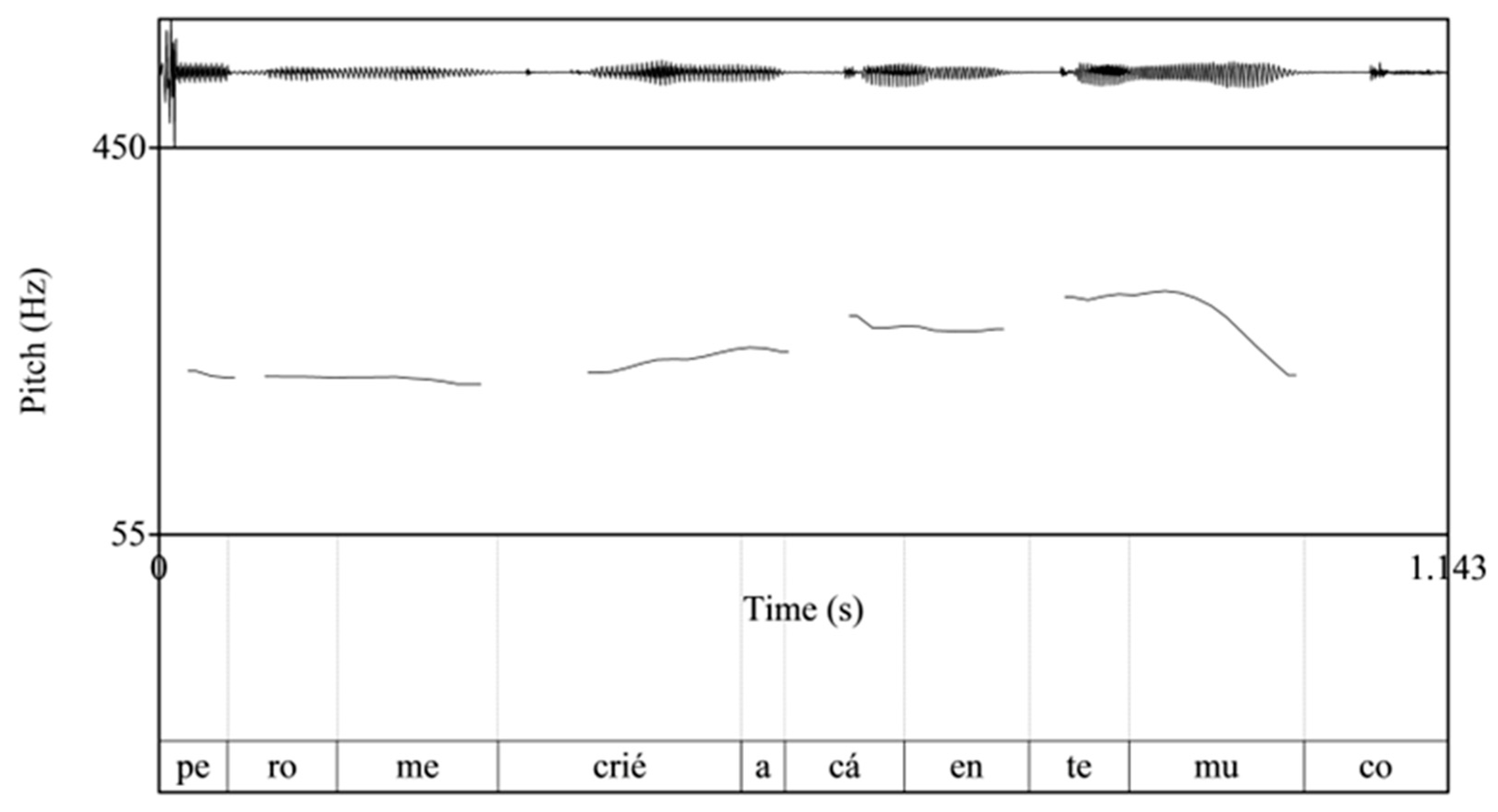

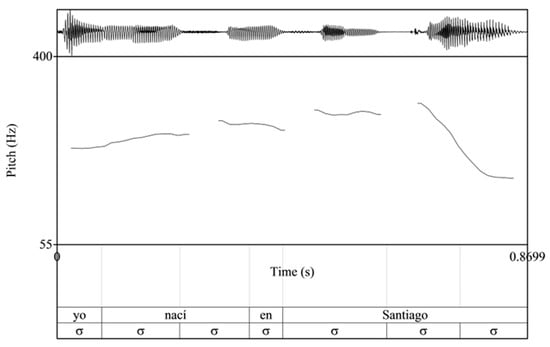

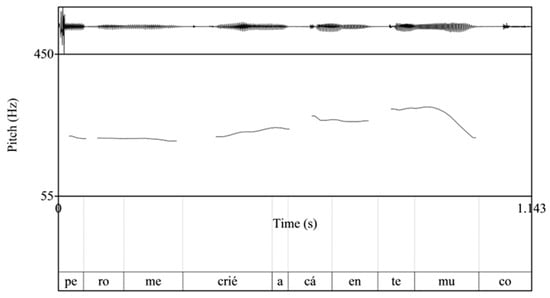

The first examples we will examine are cases where the plateaus are used on content that would typically be considered to be in narrow focus. In Figure 5, the speaker produces a relatively short plateau on the phrase yo nací en Santiago ‘I was born in Santiago’. The conversation is taking place between the interviewer and a speaker who lives in Temuco, and the interviewer asks if the speaker was born there in Temuco. In this case, then, the answer to the question contrasts the place where the speaker was born with the place asked about by the interviewer. In the figure, we can see an F0 rise on the verb nací ‘was born’ and the high F0 maintained, creating a plateau, through the following preposition and the beginning of the word Santiago. The F0 then falls through the stressed syllable of Santiago to the end of the word, which is also the end of the utterance. The interviewer then repeats the word Santiago, and there is a pause of about a second. Then, the speaker contrasts where she was raised with where she was born. She has just stated that she was born in Santiago, and now she says pero me crié acá en Temuco ‘but I was raised here in Temuco’. This time, the contrast is with what she just said, but like the previous contrast, the content is produced with an intonational plateau. The F0 rises on the verb crié ‘was raised’ and continues to be high, producing a plateau through the next words until it again falls through the stressed syllable of Temuco to the end of the word and utterance. This example is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase yo nací en Santiago ‘I was born in Santiago’.

Figure 6.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase pero me crié acá en Temuco ‘but I was raised here in Temuco’.

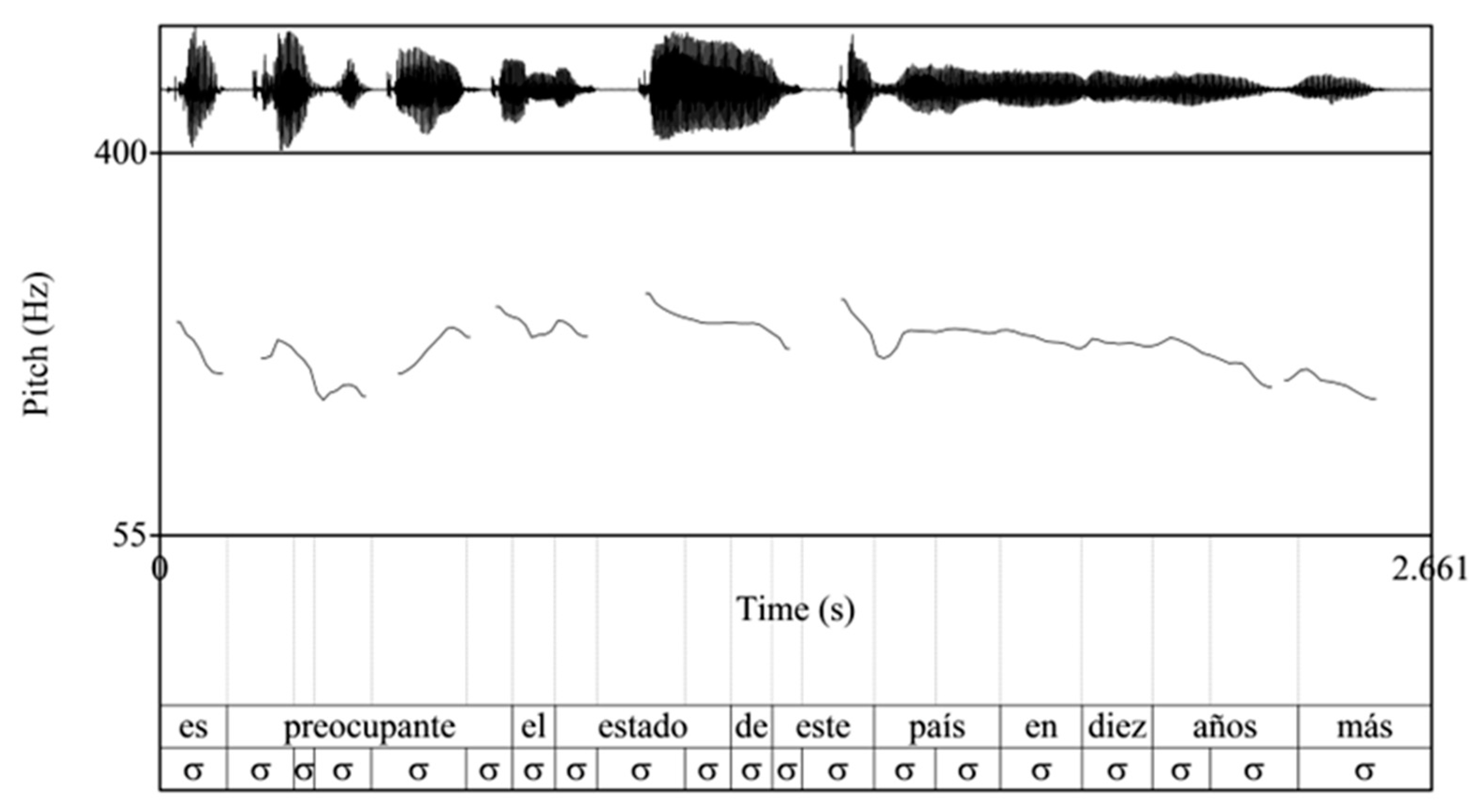

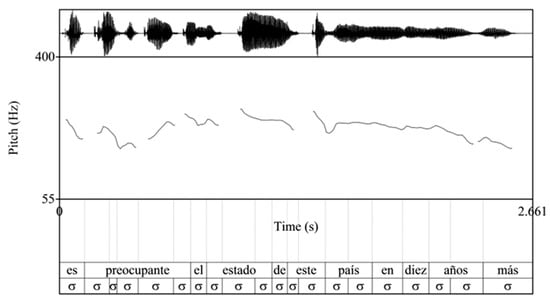

Another example of a plateau on information that can be considered to be in narrow focus is produced by a different speaker and is seen in Figure 7. In this case, the amount of content contained within the plateau is much greater, and this is an example of new information rather than contrastive focus. Immediately prior to this statement, the interviewer asks the speaker how she sees the state of Chile changing over the next ten years, whether she thinks it will get better, worse, or stay the same. In response, the speaker says es preocupante el estado de este país en diez años más ‘the state of this country in ten years is concerning’. The F0 rises on the stressed syllable of precoupante ‘concerning’ and remains high through the rest of the utterance, only falling on the very last syllable. Unlike the previous two examples, here, the information contained within the plateau is not being contrasted with anything else but is simply new information, as well as some repetition of language from the question. It could be that a plateau is used because it is new information, but it also might be that the speaker feels strongly about what she is saying here and, therefore, is choosing to use the plateau to highlight it. As mentioned above, while some plateaus occur on information that can be seen as focal, often they seem to occur because, for one reason or another, the speaker feels the need to highlight this information. We will now examine several such cases.

Figure 7.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase es preocupante el estado de este país en diez años más ‘the state of this country in ten years is concerning’.

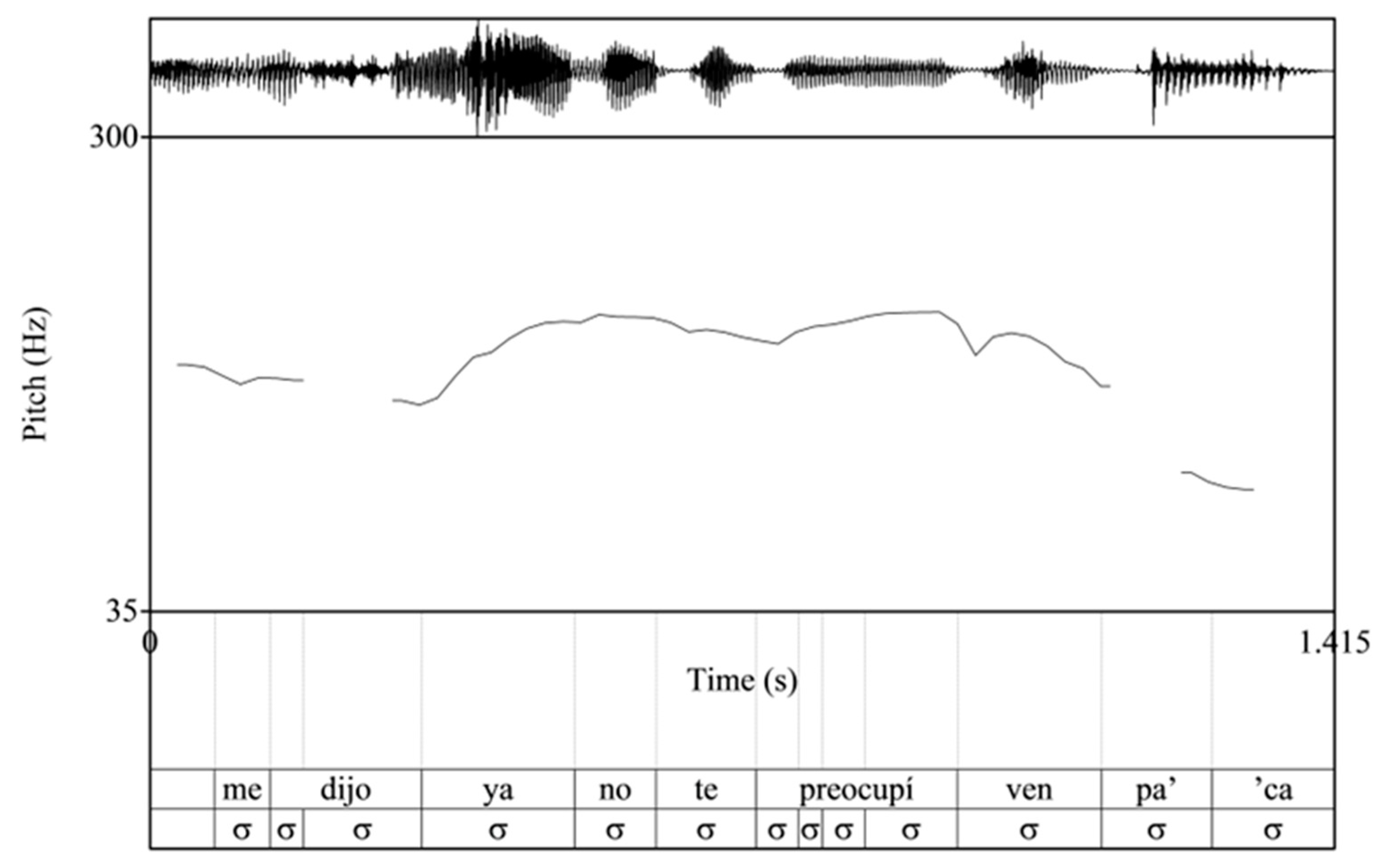

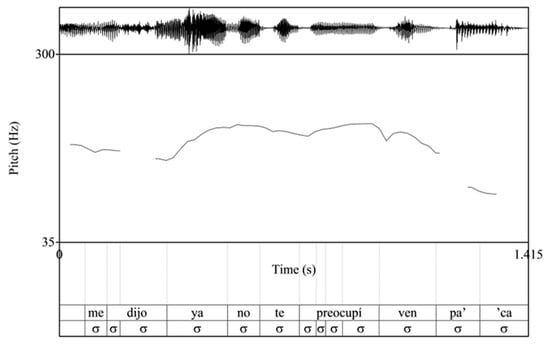

The example in Figure 8 is an instance of direct discourse in Spanish. At this point in the interview, the interviewer had asked the speaker about a mutual friend and how they knew one another. The speaker states that they had a common friend who introduced them when the speaker needed help with a school project. The speaker then proceeds to narrate the experience and explains that they spoke by phone and he told him he was having trouble. The speaker then narrates the answer using direct discourse. Most Mapudungun examples place the verb for “to say” after the reported discourse which is not included in the high tonal register of the plateau portion. In the case of the Chilean Spanish examples, Figure 8 included decir ‘to say’, at the beginning, but it is not included in the high portion. The speaker says me dijo ‘he told me in a low tonal register, which would be considered a preceding valley, and then begins to rise on the first syllable, ya ‘I understand/sounds good’, maintains the high tonal register through the next 6 syllables no te preocupí ‘don’t worry’, and then falls through the final 3 syllables ven pa’ ca’ ‘come over here’, which ends the direct discourse portion of the narration. The highlighted information is the discourse, while the verb “to say” remains at a low level and is excluded from the plateau.

Figure 8.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase Me dijo ‘ya no te preocupí, ven pa’ ca’ ‘Don’t worry, come on over’.

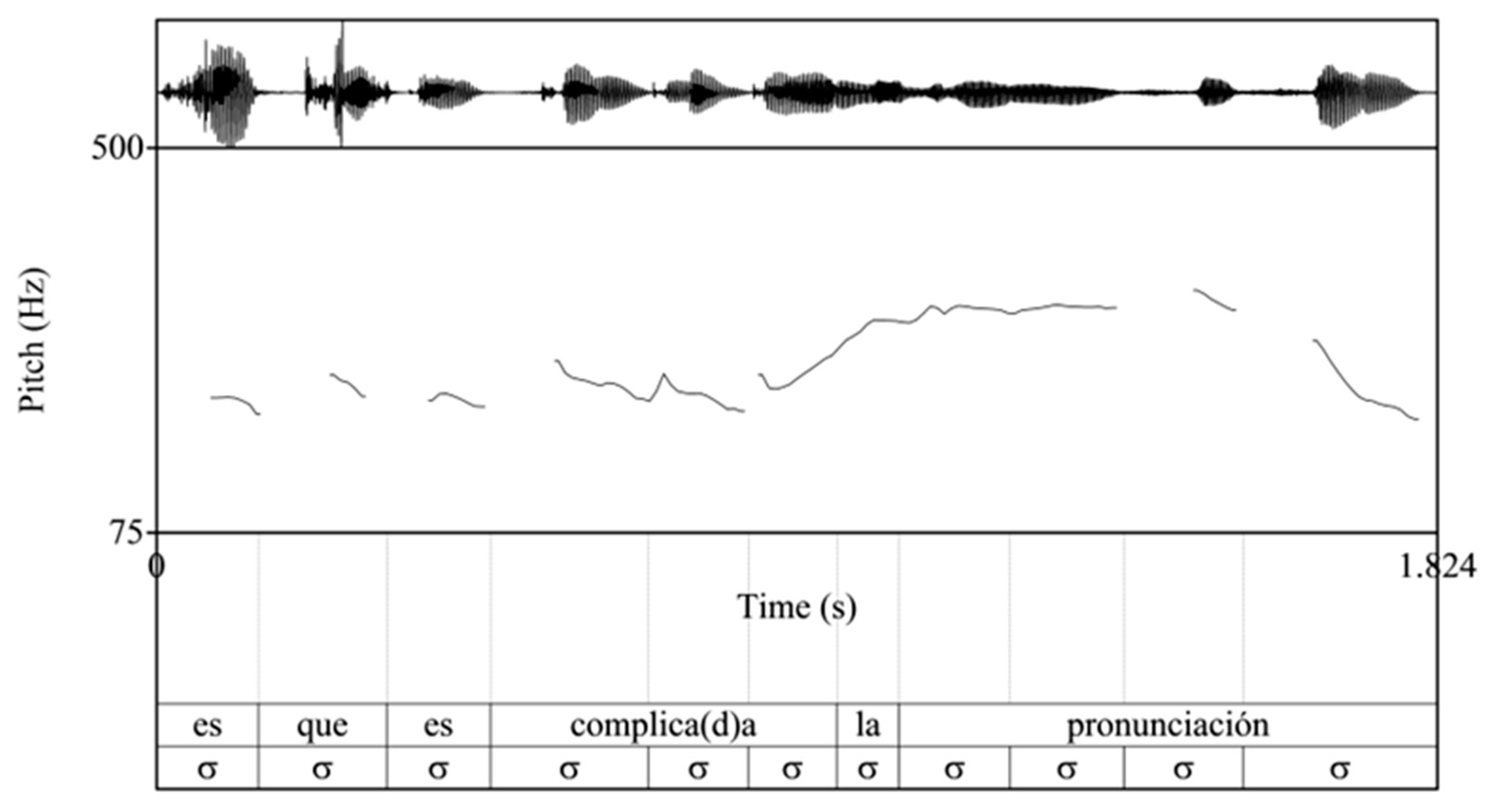

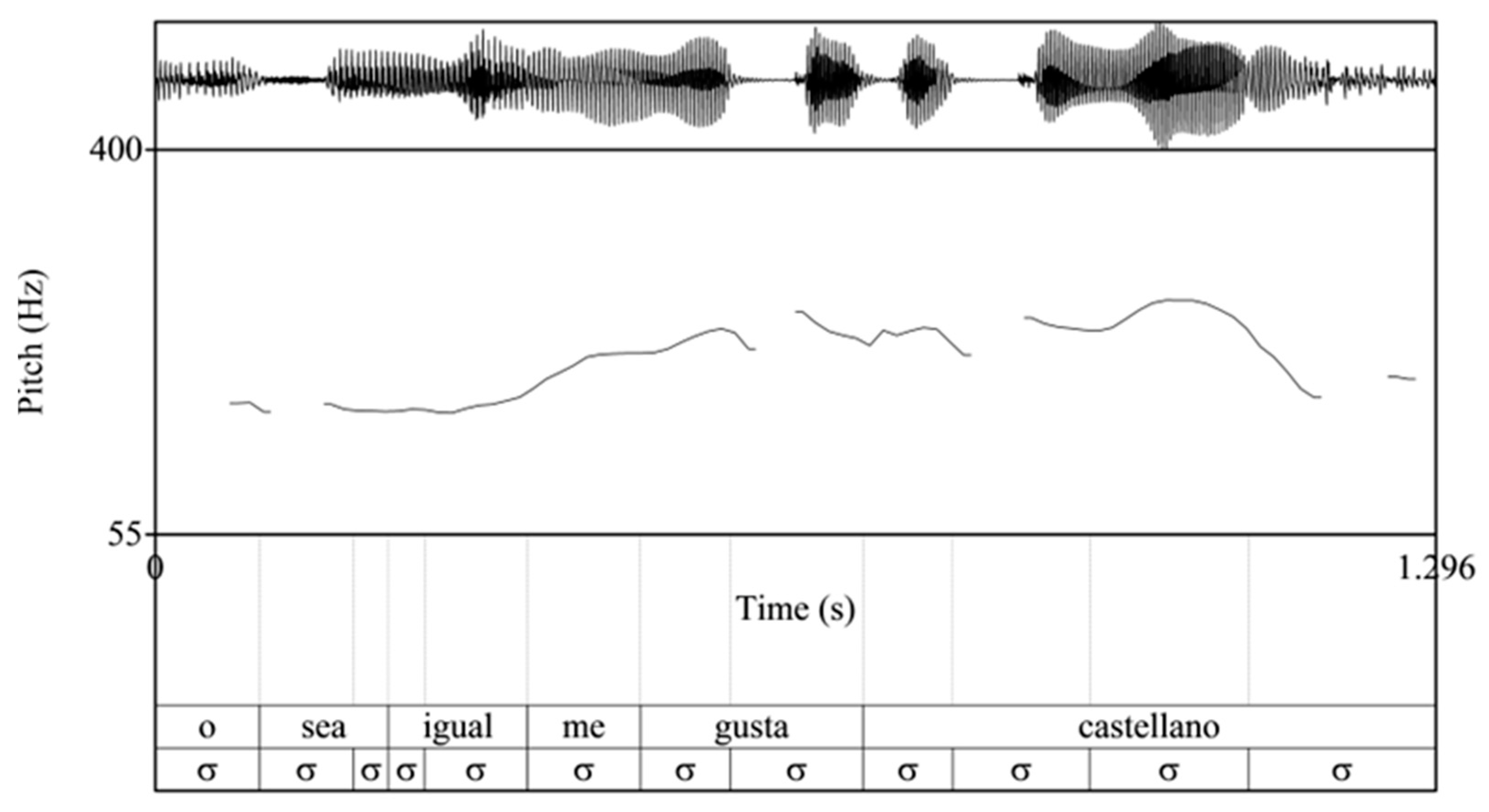

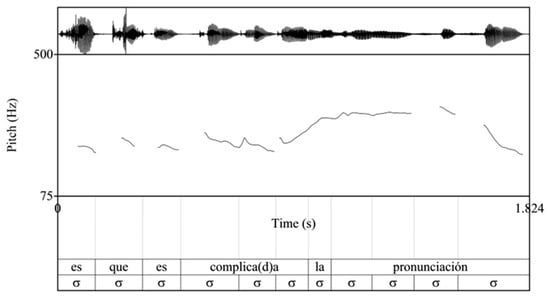

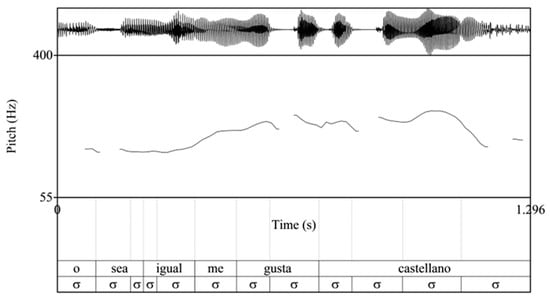

The remaining examples are of plateaus that fall into the ‘other’ category rather than any of the previously established categories. The example in Figure 9 is an example of a speaker feeling the need to highlight information. The interviewer and speaker have been talking about Mapudungun, which the interviewer has been studying, and he comments on some of the difficult sounds that he struggles with. The speaker says Es complicada ‘It’s complicated’, but then feels the need to clarify what she is talking about and says Es que es complicada la pronunciación ‘It’s that the pronunciation is complicated’ with an intonational plateau on complicada la pronunciación. The use of the plateau here appears to be for the purpose of clarifying. The speaker realizes that the first statement (i.e., Es complicada ‘It’s complicated’) might have been unclear, so she clarifies that she is talking about the pronunciation specifically and uses the plateau pattern to highlight this content. Note that while the mention of pronunciation is new in her speech (though it was mentioned by the interviewer), the rest of the content in the plateau (the mention of it being complicated) is old information. As such, this is categorized as ‘other’ because it is a mix of old and new information and does not clearly fit into the new information category. A similar but slightly different case is seen in an example from another speaker in Figure 10. Unlike the previous example, where the plateau was used on information to clarify something that might have been unclear, in this case, a plateau is used to clarify information that the speaker realizes could easily be misunderstood. The interviewer asked the speaker why she chose to study pedagogy and Spanish, and when talking about Spanish, she said that it was a decision made under pressure and that she was not sure what happened at that moment because she was originally planning to study math. After stating this, she appears to realize that she could have given the impression that she likes math and that Spanish isn’t something she likes as much. So, she immediately adds igual me gusta castellano ‘I like Spanish just as much’, using an intonational plateau on this phrase to emphasize it, and then goes on to expand on her specific interests within the subject.

Figure 9.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase Es que es complicada la pronunciación ‘It’s the pronunciation that is complicated’.

Figure 10.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase igual me gusta castellano ‘I like Spanish just as much’.

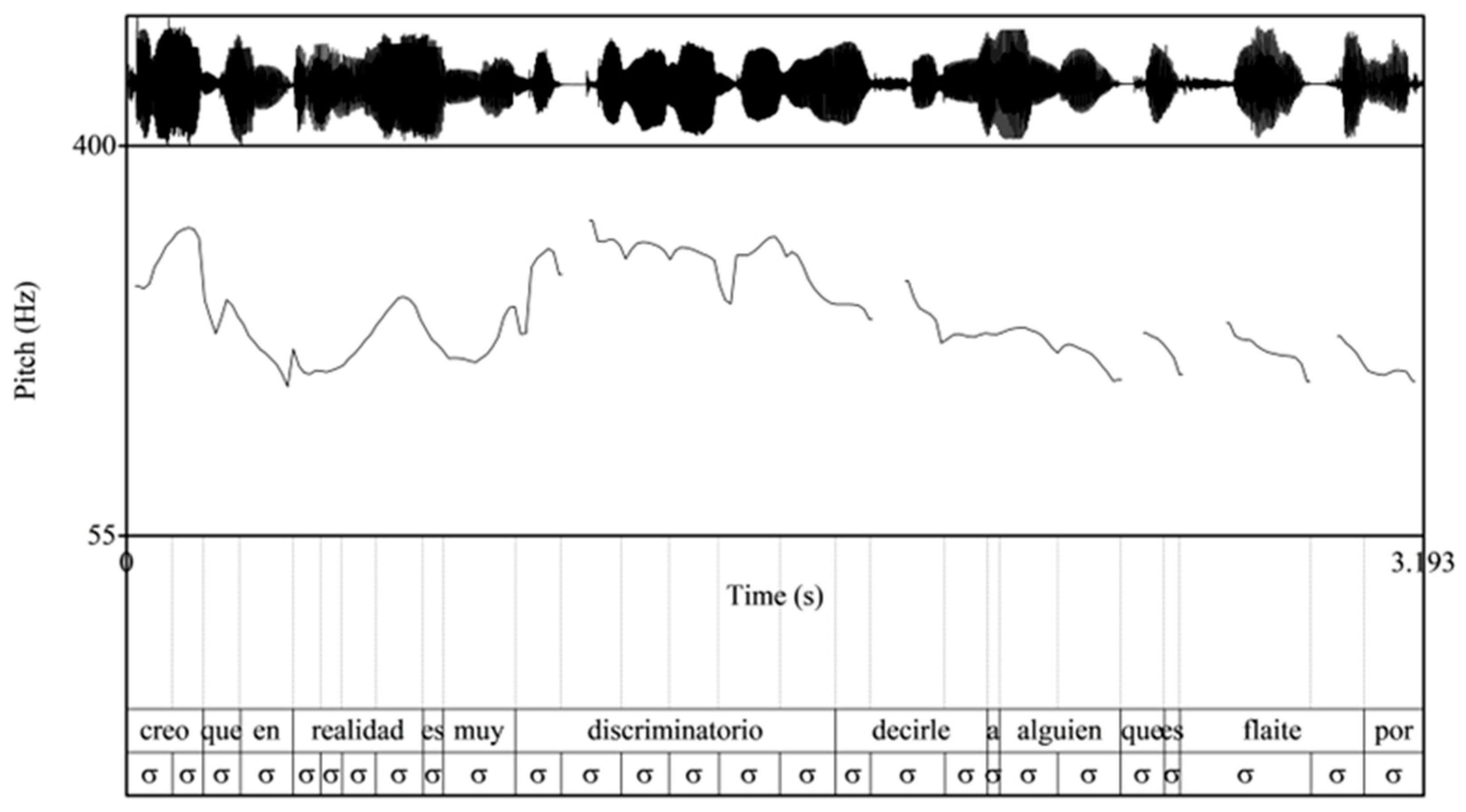

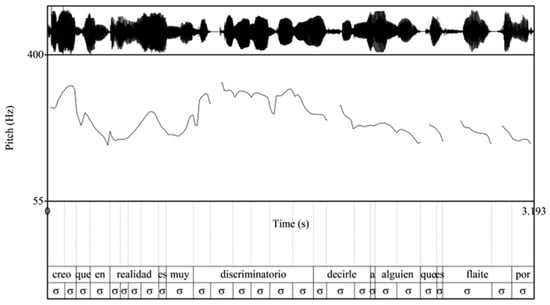

In Figure 11, we see an example of a plateau being used by a speaker to highlight something that she already said, emphasizing the point. The interviewer asked her what the word flaite ‘riffraff (slang)’ means to her. In first answering the question, she talks about it being a way to discriminate based on the way people dress and talk and that the term is applied to young people of about her age. Having made this statement, she comes back to emphasize that, in her view, it is a term used to discriminate. She says Creo que en realidad es muy discriminatorio decirle a alguien que es flaite por cómo se viste y por cómo habla ‘I think in reality, it is very discriminatory to tell someone they’re flaite because of how they dress and talk’. The speaker emphasizes her view that this term is discriminatory by adding en realidad ‘in reality’, the adverb muy ‘very’ and by using an intonational plateau over the phrase muy discriminatorio ‘very discriminatory’. Here, there is no new information and nothing being contrasted; the speaker is simply emphasizing information that she feels needs to be emphasized, even though it is old information in the discourse.

Figure 11.

Plateau in the Spanish phrase creo que en realidad es muy discriminatorio decirle a alguien que es flaite por ‘I think, in reality it is very discriminatory to call someone flaite because…’.

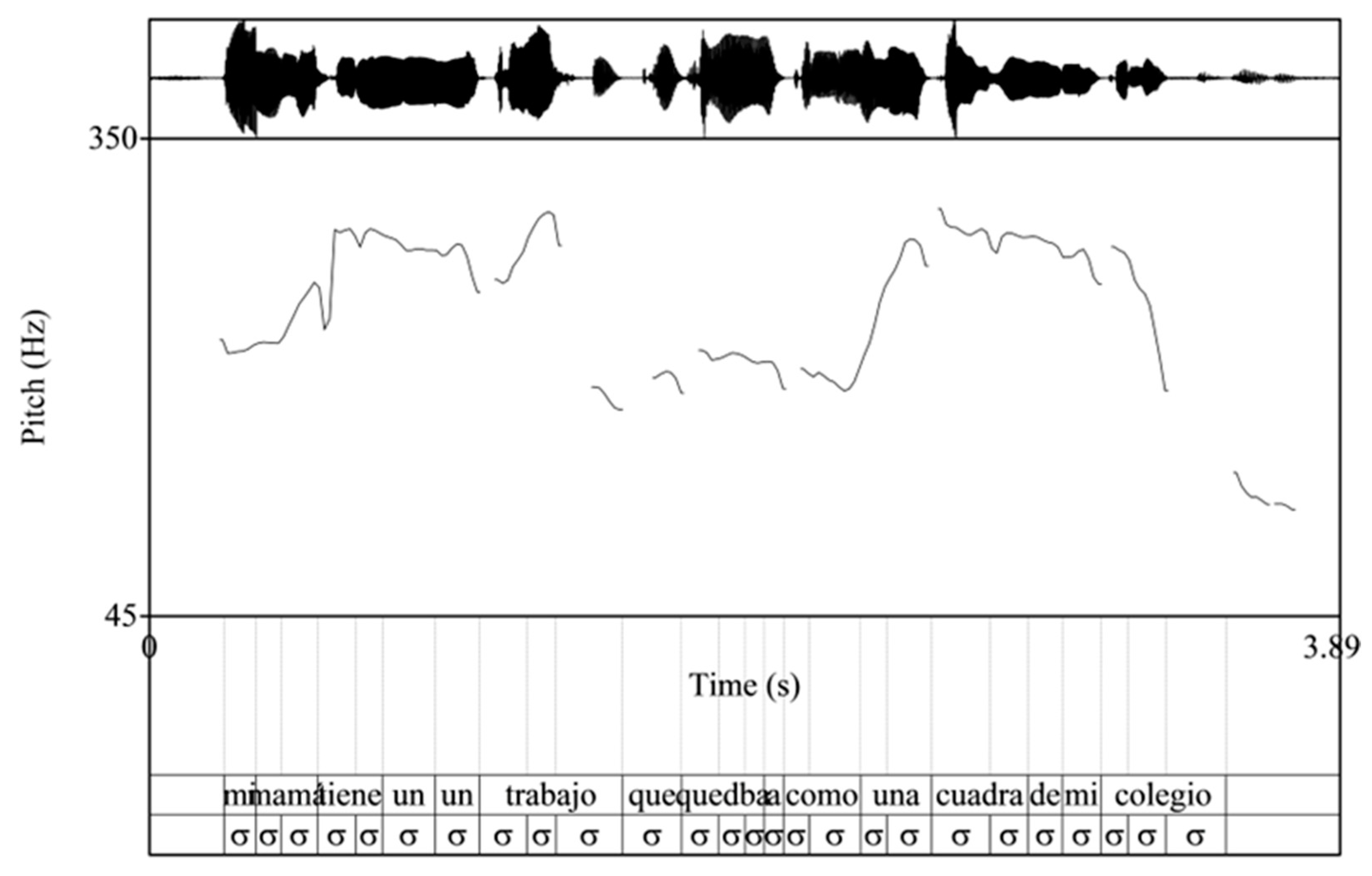

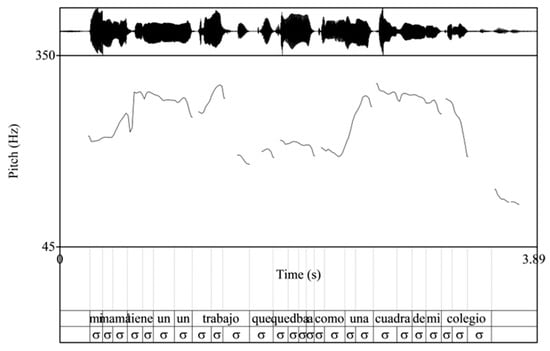

Figure 12 presents another speaker highlighting information with a plateau, in this case, because the information contained is particularly relevant to understanding the rest of the utterance. Interestingly, this plateau communicates new information but also seems to be used because of the particular relevance of this information presented. After all, most cases of new information are not produced with plateaus, so it would make sense that, in many cases, it is the combination of the information being new and some additional communicative reason that explains the use of the plateau. In this case, the interviewer asked the speaker what she did as a child for fun. The speaker responds by stating that her mother had a job that was only a block from the speaker’s school, and so she went there after school, entertained herself with her imagination, and played with dolls, but she had minimal interaction with other children. When the speaker starts off by talking about her mother’s work being only a block from the school, she uses an intonational plateau over this information (una cuadra de mi colegio ‘a block from my school’). It is of interest that it is the rest of the utterance that answers the interviewer’s question, stating what the speaker did for fun as a child, with the plateau highlighting content that is important to understand why the answer is what it is, with her having spent much of her time by herself rather than with other children.

Figure 12.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase mi mamá tiene un, un trabajo que que quedaba a como una cuadra de mi colegio ‘My mom has a job that was about a block from my school’.

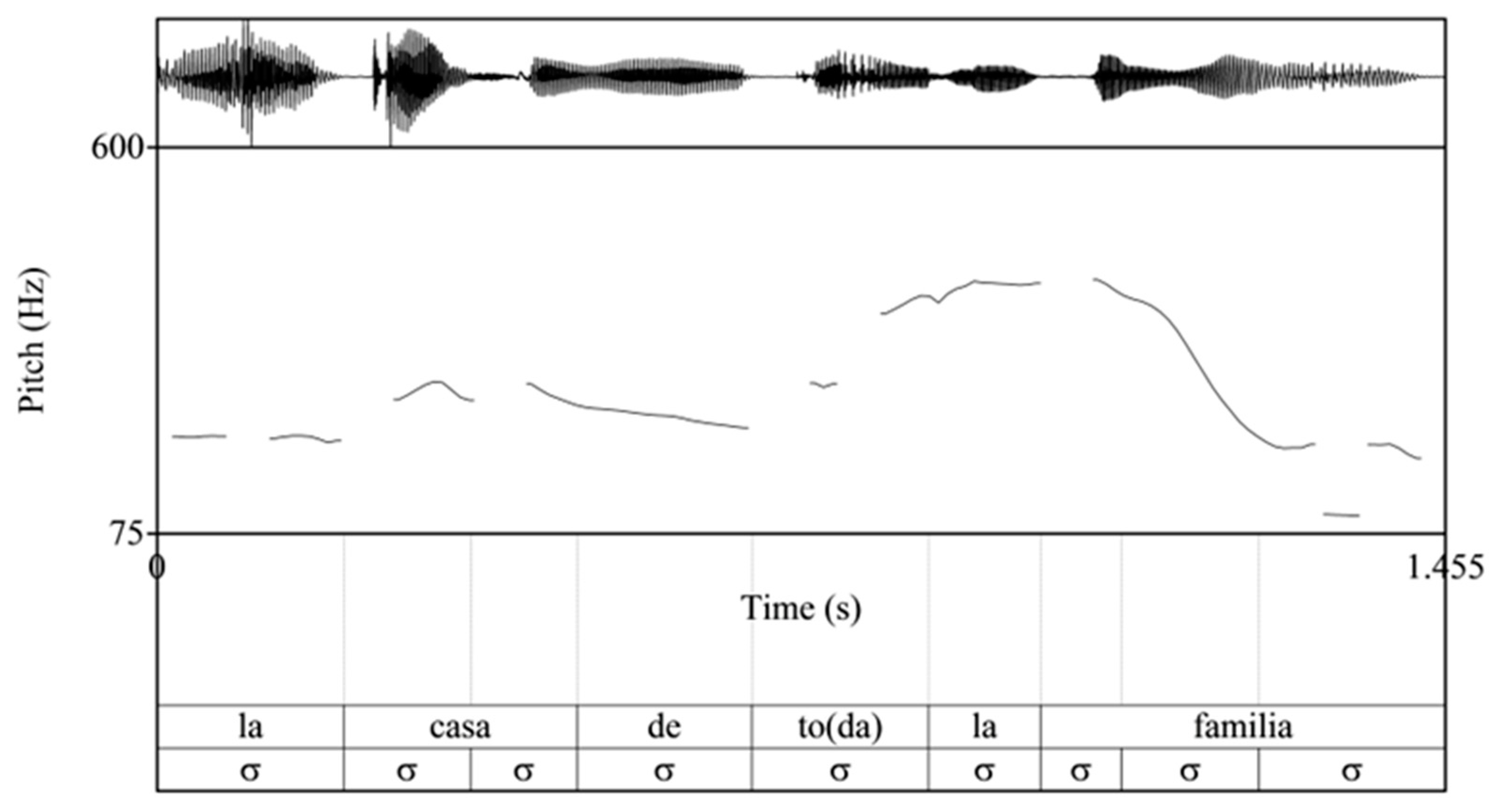

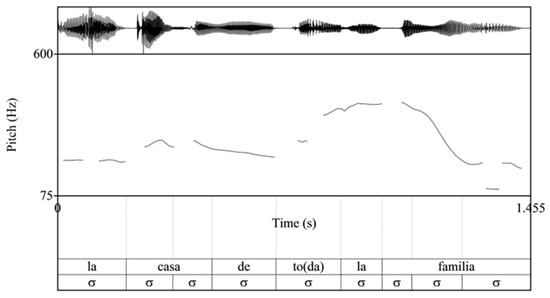

While Figure 12 presents an example using a plateau on information relevant to understanding the rest of the utterance, Figure 13 presents an example from another speaker where a plateau is used on information that provides information on why what has been said previously is important. The speaker is talking about a major earthquake that hit Chile in 2010 and the destruction she observed in some places. In talking about an area where many houses were leveled, she comments that this is an area with a lot of immigrants and, as if to clarify why the leveling of houses is so catastrophic in this area, uses a plateau to state that these houses tend to be la casa de toda la familia ‘the house for the whole family’, with the plateau over toda la familia ‘the whole family’, and then adds that these whole families were now practically living in the street. Like in Figure 12, this is another case where a plateau appears to be used not only because the information is new but also because of the need to highlight the importance of information presented in the discourse.

Figure 13.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase toda la familia ‘the whole family’ in the larger phrase la casa de toda la familia ‘the house for the whole family’.

4.3. Mapudungun Plateaus and Their Pragmatic Functions

While analyzing the Mapudungun data, it became apparent that speakers produce plateaus in a wider variety of contexts than Chilean Spanish speakers do, producing them in both yes/no and information-seeking questions and producing them more often in cases of direct discourse. As in the Chilean Spanish data, there are cases in the Mapudungun data where intonational plateaus are clearly used to communicate narrow focus, both to contrast with previous information and to introduce new information. However, as was also the case with the Chilean Spanish data, the range of pragmatic meanings attached to the emphatic nature of the plateaus does not always fit neatly into a pre-established category, and the use of the plateaus appears to be subjective and dependent on the conversational and pragmatic desires of the speakers who produce them. Table 3 presents the breakdown of the 201 Mapudungun plateaus by pragmatic function. As was the case with the previous section on the Chilean Spanish data, our analysis of the context surrounding the content communicated with intonational plateaus in Mapudungun brings to light a number of reasons that Mapudungun speakers would choose to highlight the information contained in intonational plateaus beyond the focal categories. Similar to Chilean Spanish, each speaker’s motives are often subjective reasons based on the speaker’s communicative desire. As in the previous section, we will focus here on the function of the plateaus in declaratives.

Table 3.

Classification of Mapudungun plateaus by pragmatic function.

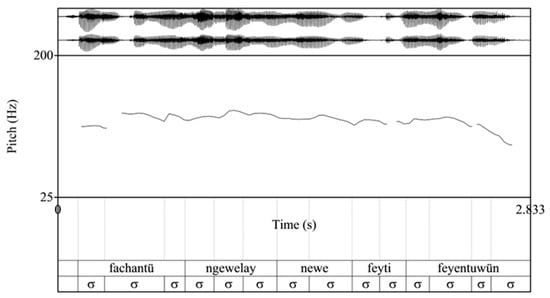

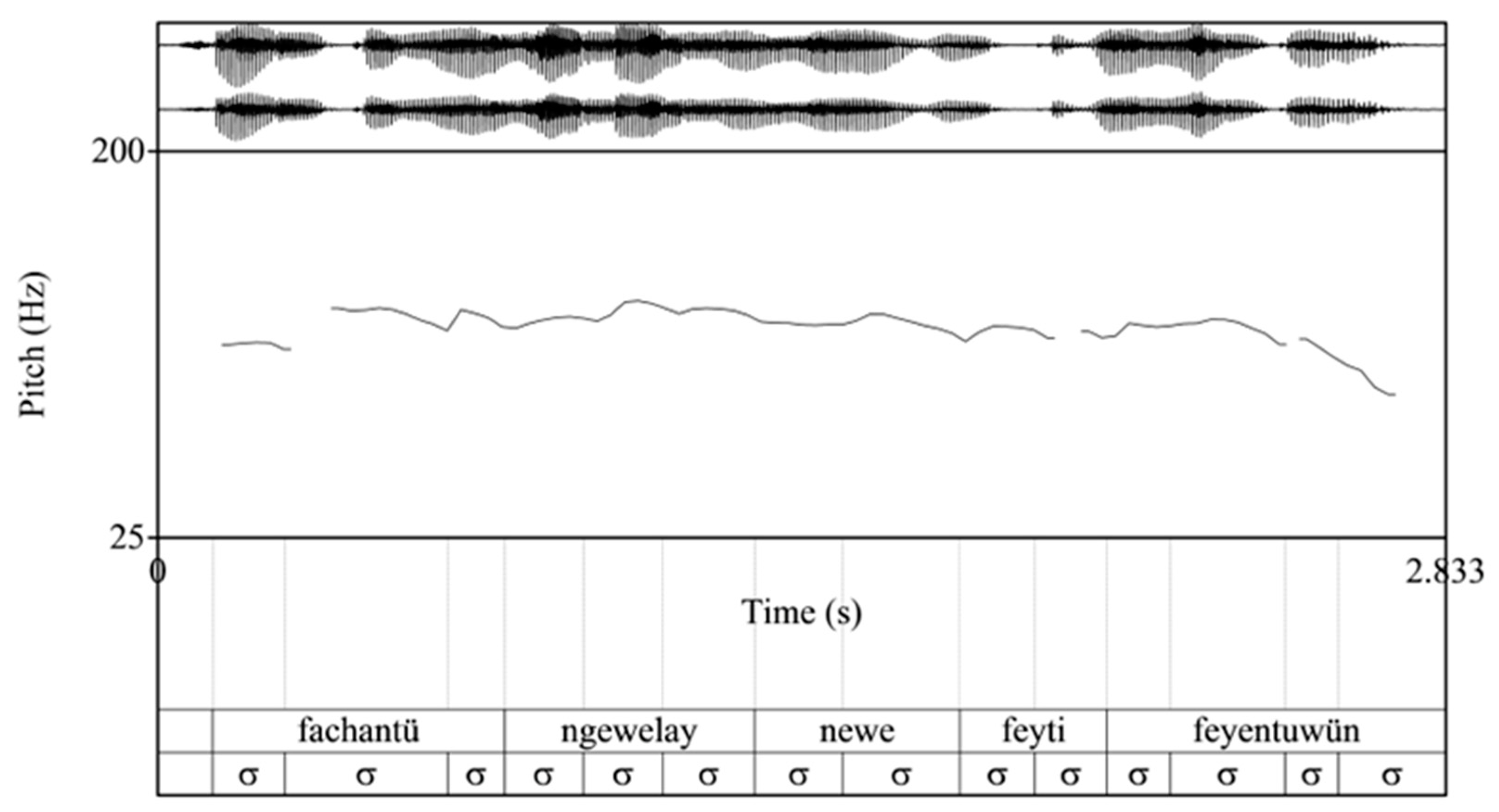

In Figure 14, the speaker produces a rather extended plateau as a mechanism of contrastive focus. In this interview, taken from Smeets (2008), the Mapudungun speaker is talking to the interviewer about how he and his friends had to come together and find ways to make money due to the economic circumstances and high unemployment levels suffered by the Mapuche community in the 1970s and 1980s, due in large part to the economic and social policies of the military dictatorship. Previous to the plateau, the speaker was talking to the interviewer about how, years before the interview, the Mapuche people used to come together more and communally help one another out. He mentions that contemporarily, there still remain some Mapuche who believe in this practice, but there is a notable portion of Mapuche who don’t ascribe to the same idea. In fact, he twice contrasts how things were earlier with how they are now, producing the plateau in Figure 14 in the second instance. The first time he contrasts, he does so with no plateau. He states Adümfiyiñ dewma feytachi trawüluwün taiñ kiñewael, doy kimuwael doy kelluael…Fachantü…femngechi, iñchiñ taiñ mapuchengen am kiñeke newe ayükenulu ka fey tüfachi trawüluewün dungu ‘We learned how to come together, to get to know each other better and to better help one another…Today…there are some of us Mapuche who do not ascribe to this practice as much’. He then reiterates how there was more union between the Mapuche before saying Welu kuifi piy am taiñ pu küpalme küme ‘In earlier times there was more trust within our families’. Finally, he contrasts previous cultural norms with contemporary ones with a plateau stating: Fachantü ngewelay newe feyti feyentuwün ‘Today there is no longer so much trust’. The F0 stays low on the first syllable fach of fachantü ‘today/now’ and then rises on the second syllable an. Once the high F0 level is attained, the speaker maintains the high F0 through the rest of the utterance, a total of 12 syllables, until the final syllable wün. In this instance, the speaker appears to consider this contrast important enough to state it twice and utilizes a plateau to markedly emphasize that, in his opinion, contemporary conditions in the Mapuche community are not what they once were.

Figure 14.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Fachantü ngewelay newe feyti feyentuwün.

Figure 14.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Fachantü ngewelay newe feyti feyentuwün.

| Fach | -antü | nge | -we | -la | -y |

| this | -day/sun | -to be | -persistence | -negation | -ind.3 sing |

| newe | fey | ti | feyentu | -w | -ün |

| barely | this | the | to believe | -reflexive | -plain verbal noun |

| ‘Today there is no longer so much trust’ | |||||

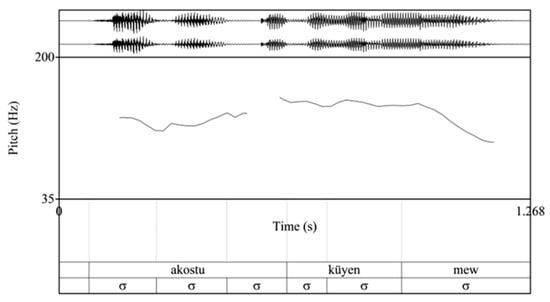

The plateau in Figure 15, taken from Olate’s (2015) corpus, is an example of a speaker using a plateau as a mechanism of narrow focus to introduce new information. In this specific case, the interviewer asked the speaker when her birthday is. The speaker says akostu küyen mew ‘in August’. The F0 stays low on the first two syllables of akostu ‘August’, rising on the final syllable tu. The F0 remains at this level for the duration of the word küyen ‘moon/month’ and then falls on the postposition mew ‘in’.

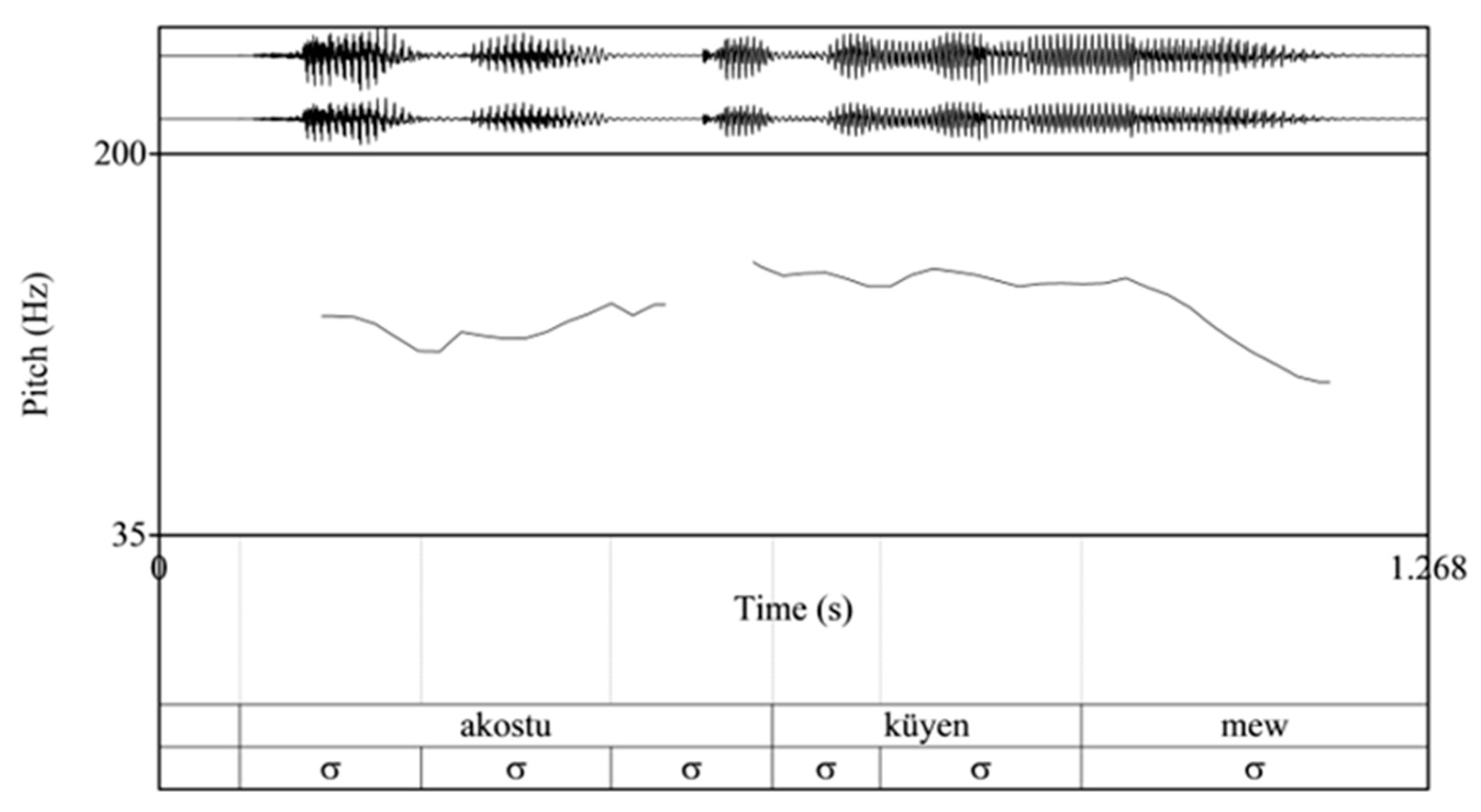

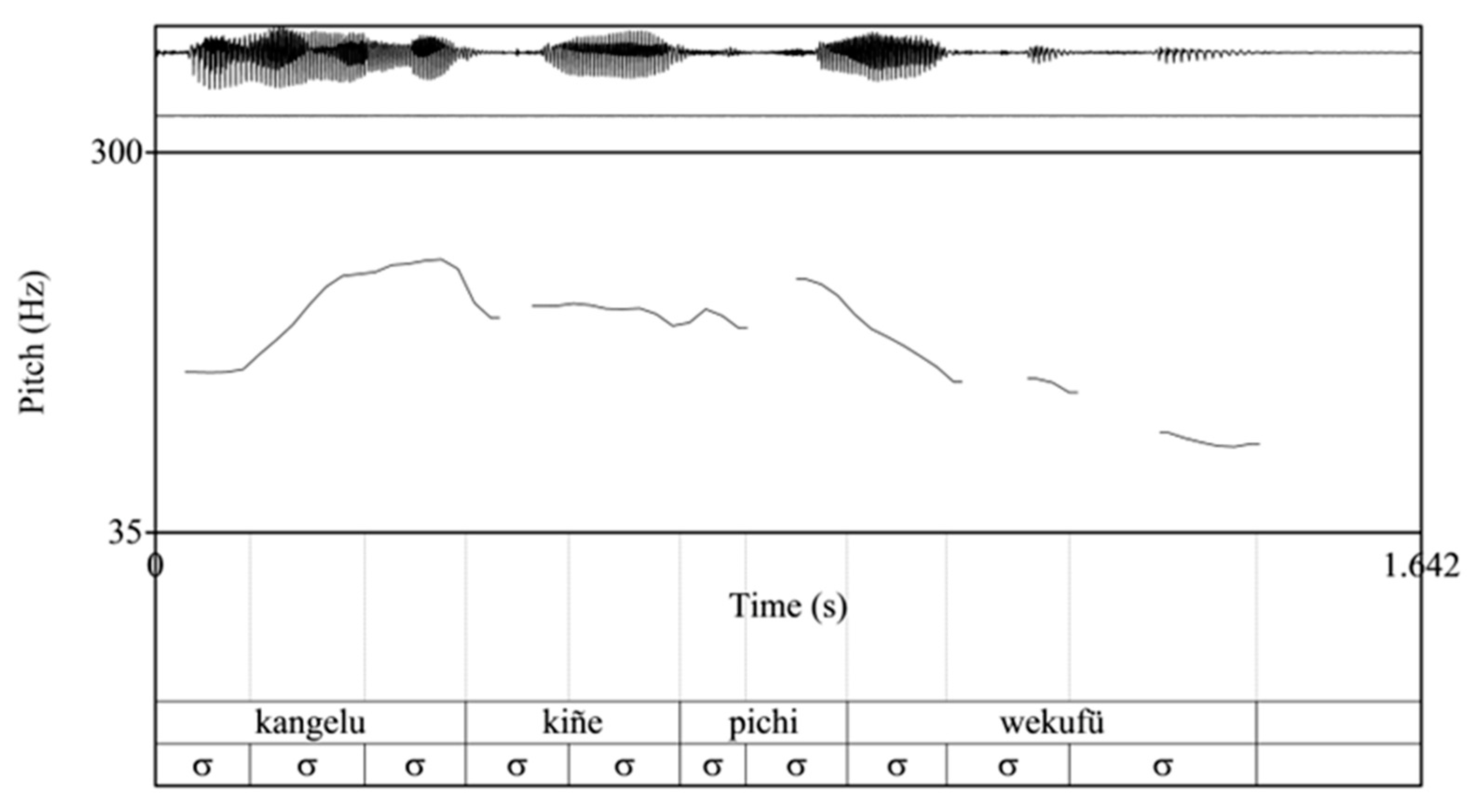

The example seen in Figure 16, taken from Smeets’ (2008) corpus of interviews, is a case where the use of the plateau marks content that is clearly in narrow focus, although in this case, the speaker is both presenting new information and contrasting it with previous information in the discourse. Here, the speaker is reading an account he wrote down earlier of wekufü, or negative spirits/demons, to the interviewer. During the course of the interaction, he describes different types of these spirits; he mentions a type of wekufü called a witranalwe and specifies that they are large in size (Feytichi witranalwe rume füchakeyngün ‘These witranalwe are very large’). After describing the witranalwe in more detail, he transitions to another class of wekufü, with the sentence Kangelu kiñe pichi wekufü ‘There is another smaller wekufü’. This transition begins the plateau seen in Figure 16, which extends for the entirety of the utterance. The F0 is low on the first syllable ka ‘another’ and then rises through the next two syllables nge ‘to be’ and lu (subjective verbal noun). The F0 achieves the high portion of the plateau on lu, and it is maintained through the following words: kiñe ‘one/a’, pichi ‘small’, and the first syllable of wekufü before falling on the final two syllables. In the high plateau portion, the speaker mentions both new information (the new type of wekufü) and contrasts the size of the new wekufü with the previous, the witranalwe. Furthermore, he reiterates the diminutiveness of this new category of wekufü saying tremkelay ‘It does not grow’. The high F0 of the plateau is used as a mechanism of narrow, albeit extended, focus that both introduces new information and contrasts with a physical quality mentioned previously to distinguish two types of supernatural entities within the Mapuche cosmovision.

Figure 15.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase akostu küyen mew.

Figure 15.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase akostu küyen mew.

| akostu | küyen | mew |

| August | month/moon | in |

| ‘in August’ | ||

Figure 16.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Kangelu kiñe pichi wekufü.

Figure 16.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Kangelu kiñe pichi wekufü.

| ka- | -nge | -lu | pichi | wekufü |

| other | -to be | -subject verbal noun | small | negative spirit/demon |

| ‘There is another smaller wekufü’ | ||||

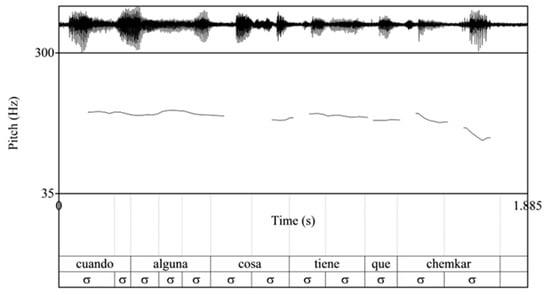

Figure 17 provides an example of direct discourse taken from Caniupil et al. (2019). The speaker talks about an instance where she had to receive care at the hospital. At some point, the attending doctor told her they needed to take an X-ray of her to help evaluate her condition. The speaker relates this information and produces a plateau stating “Radiografía entulayu” pingefun ka ‘“I am going to take an X-ray of you” I was told/they told me’. The plateau starts on the word radiografía ‘X-ray’, an obvious borrowing from Spanish, with the F0 rising on the first syllable and staying at the same level through the entire quote from the doctor up until the penultimate syllable a, where the F0 rises slightly, then falls on the final syllable yu, and continues to drop through the syllables pi and nge, where it then stays at the same low tonal register through the final two syllables fun and ka. While it could be argued that this is simply another example of narrow focus since the information about the X-ray being needed is new information, the fact that the speaker produces the plateau only on the direct quote portion of the sentence could be indicative that aside from highlighting new information, the speaker is also using the plateau to distinguish the direct quote from her continued narration of the events. If true, then the speaker is using both the verb pingefun ‘I was told’ and the intonational cues of the plateau to help the interviewer distinguish between her narration and the direct quote of the doctor.

Figure 17.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Radiografía entulayu pingefun ka ‘.

Figure 17.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Radiografía entulayu pingefun ka ‘.

| radiografía | entu | -l | -a | -(e) | |

| X-ray | to take out | benefactive | -unrealized action | -internal direct object | |

| -y | -u | pi | |||

| -indicative | -1st person singular agent 2nd person singular dative subject | to say | |||

| -nge | -fu | -n | ka | ||

| -to be | -past | -1st person singular | and/discourse marker | ||

| “I am going to take an X-ray of you” I was told/they told me’ | |||||

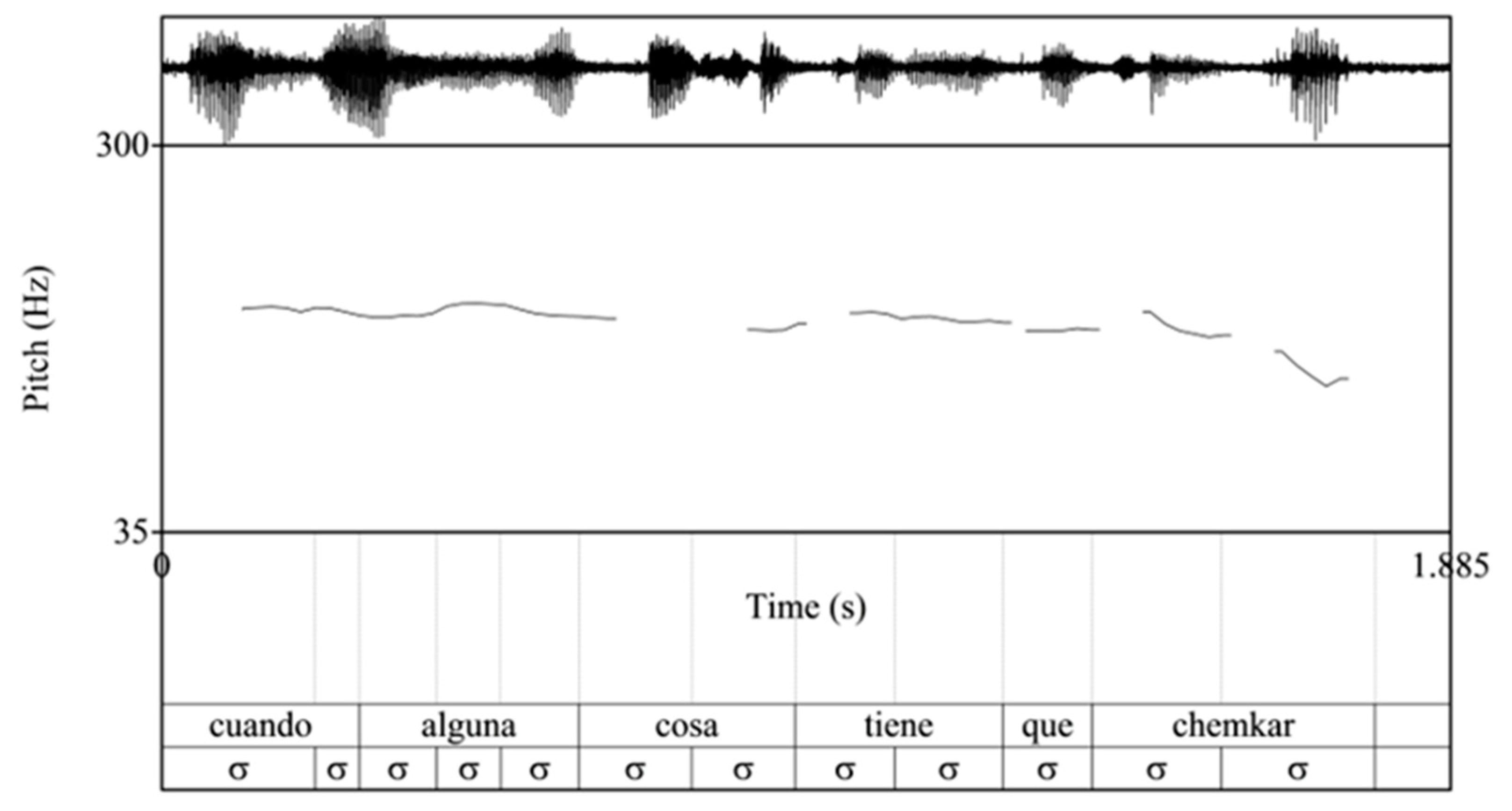

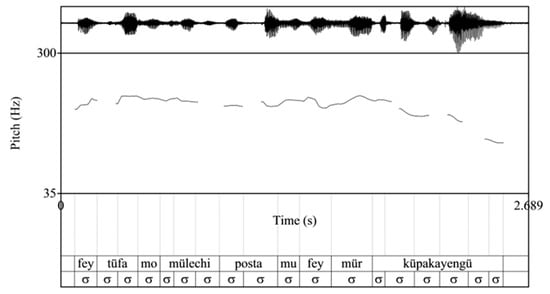

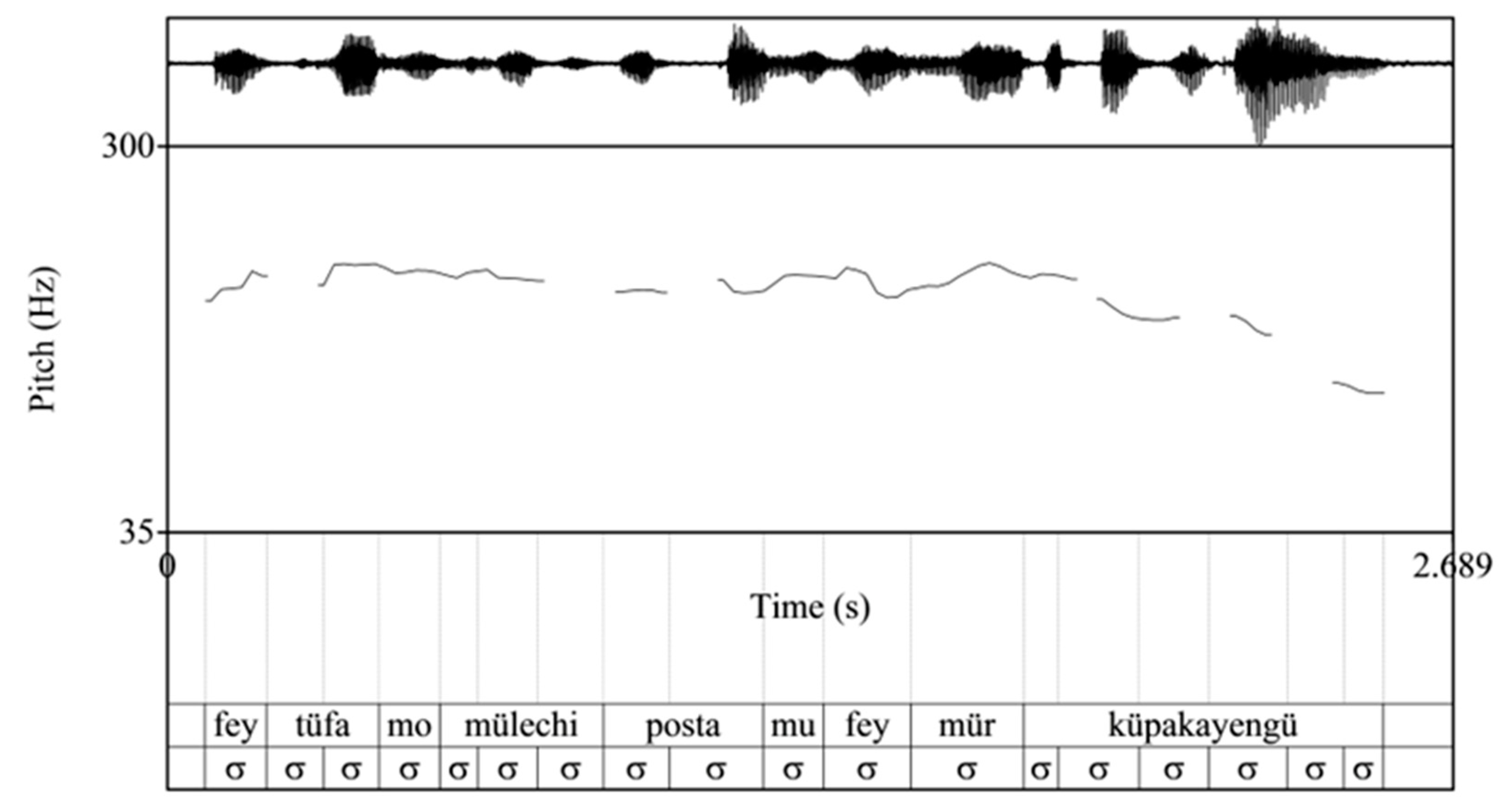

While the previous examples can be argued to fit into previously established pragmatic categories, many of the uses of plateaus could not be neatly categorized as specific types of focus or speech acts. In fact, most plateaus are very closely dependent on and subjective to the specific communicative desires of speakers. The examples in Figure 18 and Figure 19 are taken from a conversation in Caniupil et al. (2019). At this juncture of the conversation, the speaker has been talking to the interviewer about how well she was tended to in a hospital in the small town of Lonquimay in southeastern Chile. She mentions that one of the reasons that Mapuche patients like this hospital is the fact that there is a Mapudungun-speaking woman who interprets for Mapudungun-speaking patients as well as relays health-related information to local Mapuche communities, stating Küme atendengeken. Müley kiñe lamngen amuldungun mu ‘I was well cared for. There is a woman who relays information in Mapudungun’. The interviewer, seemingly intrigued by this, prompts the speaker to elaborate and speak about the interpreter in more detail. The speaker goes on to give the interpreter’s name and talks about how she visits different Mapuche communities to relay information. She does so accompanied by a doctor in order to care for people in the community. The interviewer asked if she had ever come to the speaker’s community, which the speaker confirmed. Then, interestingly, the speaker produces two consecutive plateaus: one mostly in Spanish and the following in Mapudungun. In the first plateau (Figure 18), the speaker code switches to Spanish and says Cuando alguna cosa tiene que chemkar ‘Whenever there is something that needs to get done’. The F0 rises on the first syllable of cuando ‘when’ and remains at that high level until the final syllable of the final word chemkar ‘get done’, which is a Mapudungun stem with a Spanish inflection, maintaining the high tonal register for a total of 10 syllables. Next, the speaker switches back to Mapudungun and produces another plateau (Figure 19) and states Fey tüfa mo mülechi posta fey mür küupakekayngu ‘So both of them (interpreter and doctor) regularly come to this clinic’. In this case, the fundamental frequency begins to rise on the first word fey ‘so’ and is maintained at the same high register until the final two syllables kay and ngu. In total, the high F0 extends through 14 syllables. In both of these cases, there is no new information, nor contrasting information, presented by the speaker; rather, the speaker seems to be highlighting both what the woman does when she visits the Mapuche communities and that she regularly comes to the speaker’s community as well.

Figure 18.

Plateau on the mostly Spanish phrase Cuando alguna cosa tiene que chemkar ‘Whenever there is something that needs to get done’.

Figure 18.

Plateau on the mostly Spanish phrase Cuando alguna cosa tiene que chemkar ‘Whenever there is something that needs to get done’.

Figure 19.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Fey tufa mo mülechi posta fey mür küupakekayngu.

Figure 19.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase Fey tufa mo mülechi posta fey mür küupakekayngu.

| Fey | tüfa | mo | mule | -chi | posta | mu | fey | mür | küpa | -ke | |

| So here | in | to be | -adjectivizer | clinic | in | them | pair | to come | -habitual | ||

| -ka | yngu | ||||||||||

| continuative | -ind.3 dl | ||||||||||

| ‘Both of them (interpreter and doctor) regularly come to this clinic’ | |||||||||||

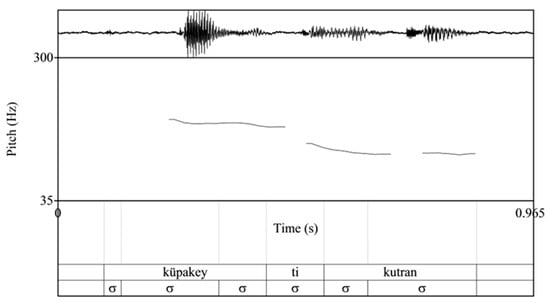

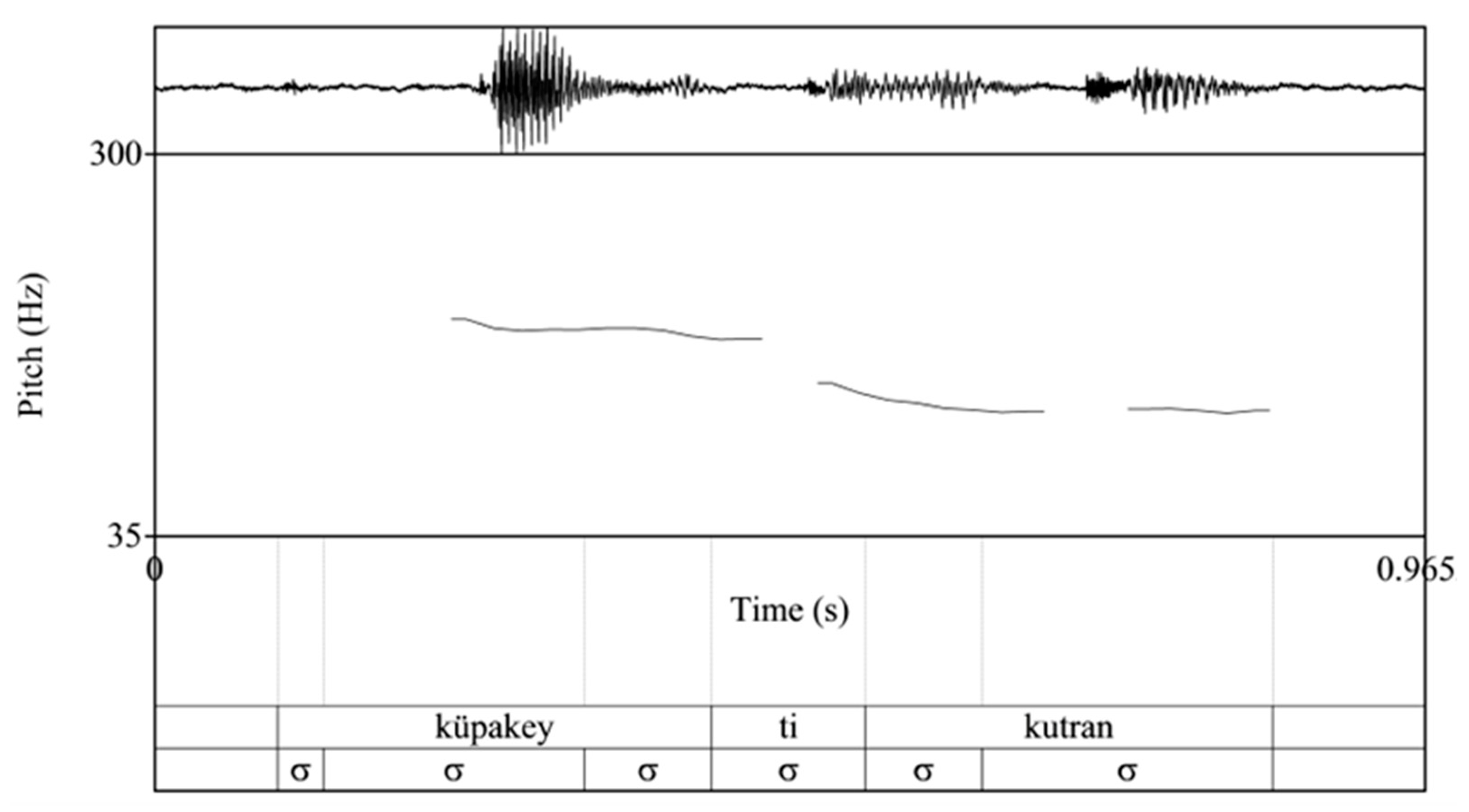

In Figure 20, the interviewer and the speaker are talking about health measures that the Mapuche in the area are taking or should take to prevent sickness. They talk about the various ways outbreaks of different sicknesses can get into the community, such as through areas where livestock frequently are present. At one point, the speaker laments that more people are not taking appropriate measures to help support the overall health of the community. The interviewer then prompts the speaker to reiterate a point that he made earlier about the water being another means through which people can get sick, stating Eymi chempikeymi ta ko mu ka küpakey pi kutran ko ‘You said that it comes in the water, contaminated water’. The speaker then confirms this and states küpakey feyti ko liftungelay…fey fill fichu konüy ‘It comes with unclean water…all sorts of bugs (bacteria and viruses)’. He then reiterates this point, producing a plateau, stating: küpakey ti kutran ‘The sickness tends to enter’. The F0 rises on the second syllable pa of küpakey ‘it/they enter’. There is no F0 visible on the first syllable due to a devoiced vowel after /k/. The F0 is maintained at the same high register for the remaining two syllables, then falls on ti ‘the’ and continues at the same low register through the final word kutran ‘sickness/suffering’. Once again, the information is not new, rather the speaker appears to use the plateau to reiterate that sickness can enter the community through the water, and with the F0 only being maintained for the duration of küpakey ‘it/they enter’, the speaker emphasizes the means (i.e., dirty water) by which some sicknesses enter the community.

Figure 20.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase küpakey ti kutran.

Figure 20.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase küpakey ti kutran.

| Küpa | -ke | -y | ti | kutran |

| to come | -habitual | -ind.3 sing | the | sickness |

| ‘That’s how sickness gets in’ | ||||

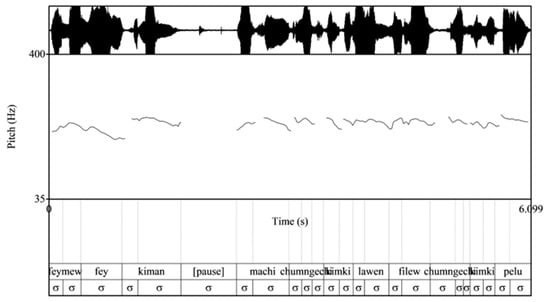

In the next example, shown in Figure 21, the speaker and the interviewer were talking about the struggles that the speaker had with school as a child due to the long distances he had to travel to get to school, as well as the lack of nearby schools. The speaker talks about how he had to travel to different communities throughout his childhood to find schools since there were few schools around, and those few were spread across a large geographic area. He mentions that he was sent to a school in Cabulco, a town in Southern Chile near Puerto Montt. Then, he was sent further north to Pellahuen, which is over 5 h from Cabulco. He also indicates that his experience was not unique, as there were a lot of kids in the school in Pellahuen. He then produces a plateau, stating …ngelay ekwela chew rume fey ta ‘There wasn’t a school anywhere around so…’ The information in the plateau appears to be an explanation for why there were so many kids at the school in Pellahuen. The F0 begins to rise on the first syllable of the verb neglay ‘there weren’t’ and then is maintained at the same high register until the end of the final syllable of rume ‘anywhere’, where it begins to fall and continues at the same low tonal register through the final two words fey ta ‘so’. As has been the case with many of the previous plateaus, the information is not new or contrastive. Rather, the speaker is highlighting not only the reason that there were so many kids in his class in Pellahuen but also appears to be emphasizing how few schooling options there were for rural Mapuche youth at that time.

Figure 21.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase ngelay ekwela chew rume fey ta.

Figure 21.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase ngelay ekwela chew rume fey ta.

| nge | -la | -y | ekwela | chew | rume |

| to be | -negation | -ind.3 sing | school | where | even |

| fey ta | |||||

| so discourse marker | |||||

| ‘There wasn’t a school anywhere around, so…’ | |||||

5. Discussion

Despite resistance to the idea of Mapudungun’s influence on Chilean Spanish, recent studies continue to point to Mapudungun having left a more robust footprint on Chilean Spanish than asserted by previous researchers. One reason there has been resistance to the idea of Mapudungun influence is the fact that, historically, it has been difficult to study Mapudungun in the context of language contact due to political and cultural tensions. Likewise, due to the marginalization of Mapudungun and Mapuche culture, speakers can be reluctant to speak Mapudungun or even to reveal that they speak Mapudungun (Sadowsky, personal communication). Further complicating matters are some of the negative attitudes toward Mapudungun and other Amerindian languages that some early researchers held, which led to an almost complete disregarding of the possibility that languages such as Mapudungun could influence Spanish in any linguistically meaningful way (e.g., Alonso 1953). This has left a dearth of contact studies in the early literature on Mapudungun. Thus, it is difficult to determine if or when certain changes from Mapudungun began to enter Chilean Spanish, and any early changes that may have taken place in Chilean Spanish because of Mapudungun may have become more systematically incorporated into Spanish, possibly becoming standard features of Chilean Spanish. This standardization potentially makes it more difficult to trace their possible contact-induced origins. As a result of this lack of evidence, some researchers have dismissed claims of Mapudungun influence on Chilean Spanish made by early researchers (e.g., Lenz 1893) and argued that many of the particularities in Chilean Spanish that have been attributed to contact with Mapudungun are simply due to endogenous factors and that there is simply not enough data to prove the Mapudungun origins of much more than lexical borrowings and toponyms (e.g., Alonso 1953).

To begin addressing this issue, we now consider our first research question: What are the pragmatic functions of Chilean Spanish and Mapudungun intonational plateaus in terms of the types of utterances in which they are used and the discourse meanings that they communicate? As shown in previous studies (e.g., Rogers 2020a, 2020b) and the current dataset, speakers of both languages use the plateau patterns to highlight a varying, and often syntactically and pragmatically complex, amount of information, regardless of what is traditionally accepted as being stressed content. Likewise, the content and when the fundamental frequency rises and falls appear to be dependent on the communicative goals and desires of the speakers of both languages rather than on any underlying phonological rules or conditions. The pragmatic function of the plateaus is to highlight a varying amount of information that speakers in both languages deem important. What makes it difficult to categorize the function of the plateaus is that the motives of speakers for highlighting information appear to vary greatly. In some cases, the plateaus are clearly produced in traditional contexts of narrow focus. However, in other cases, the plateaus are completely subject to the motives of the speakers and it is difficult to place them into existing pragmatic or prosodic categories. Instead of being mechanisms for specific, pragmatic contexts, we propose that the plateau patterns in both languages are specific prosodic structures with the pragmatic function of highlighting any information that a speaker in either language deems important enough to call to the forefront of the attention of their interlocutor.

The assertion that speakers use prosody according to their own communicative desires rather than following set rules or demonstrating systematic regularities appears to make some linguists uncomfortable but is not without precedent. With regard to current approaches to intonational phonology and its ability to represent pragmatic usages of intonation, Prieto (2015) states that most studies have primarily looked at intonation as a representation of the phonological capabilities of the speakers and have not examined how the phonological representations match up with the communicative and pragmatic goals of speakers. Furthermore, she states that “some of the traditional assumptions on intonational meaning…do not stand well with empirical findings.” (p. 379). One of these discrepancies is the deeply rooted assumption within current intonational phonology studies that there is generally a “one-to-one” relationship between the form that contours take and their meanings, with little or no regard to the context in which speakers produce such contours (p. 374). Similarly, Hirschberg (2002) asserts:

“While students of intonational meaning generally look for the regularities in intonational interpretations such as ‘Increased prominence is interpreted as focus’…there are too many counter-examples in normal speech production to conclude that particular intonational behavior maps simply to clear interpretations. Even when empirical studies have found regular associations between phenomena…these studies also find many occasions when commonly accepted “meanings” of intonational features do not seem to hold.”(pp. 3–4)

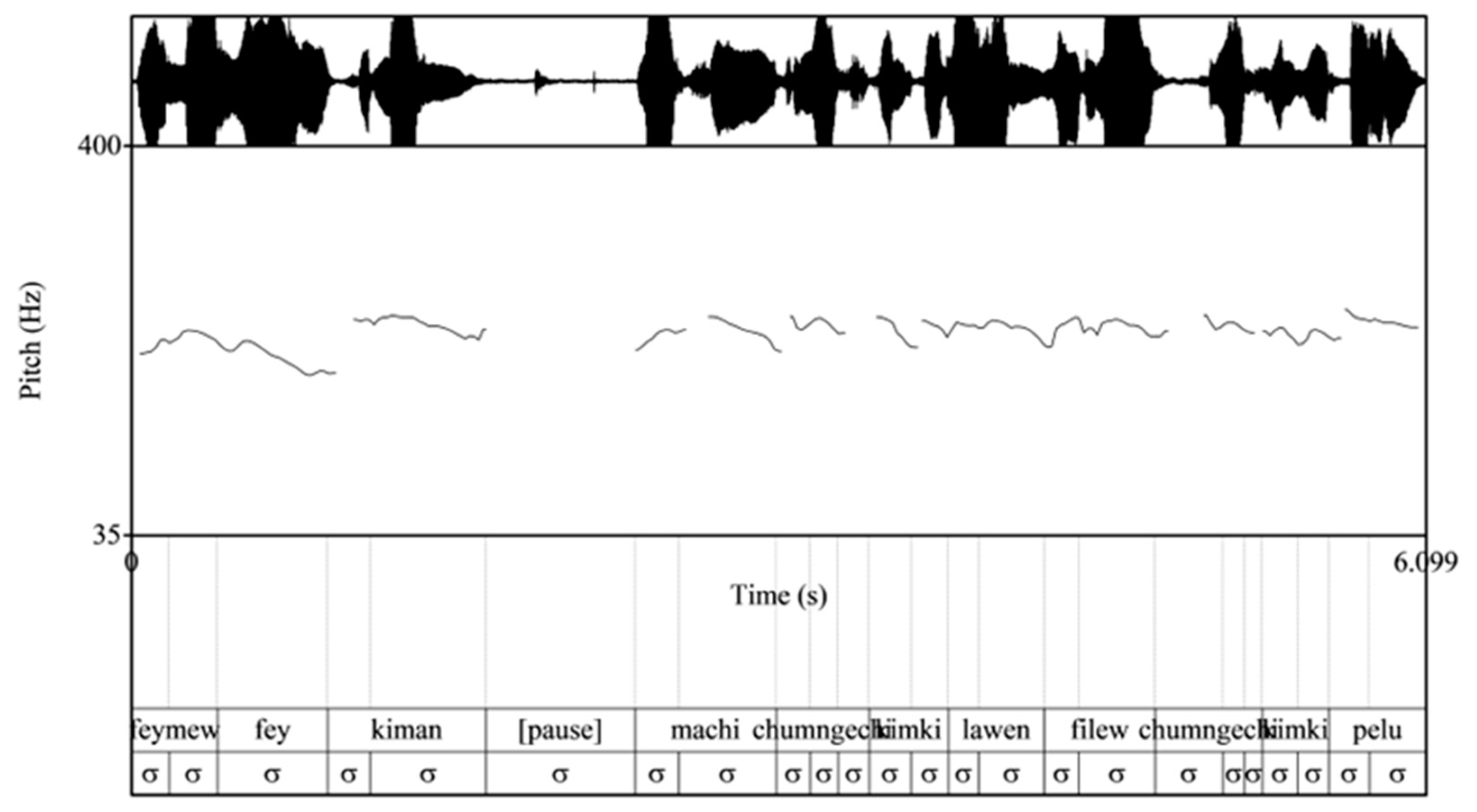

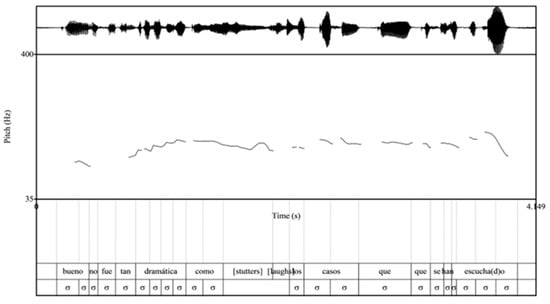

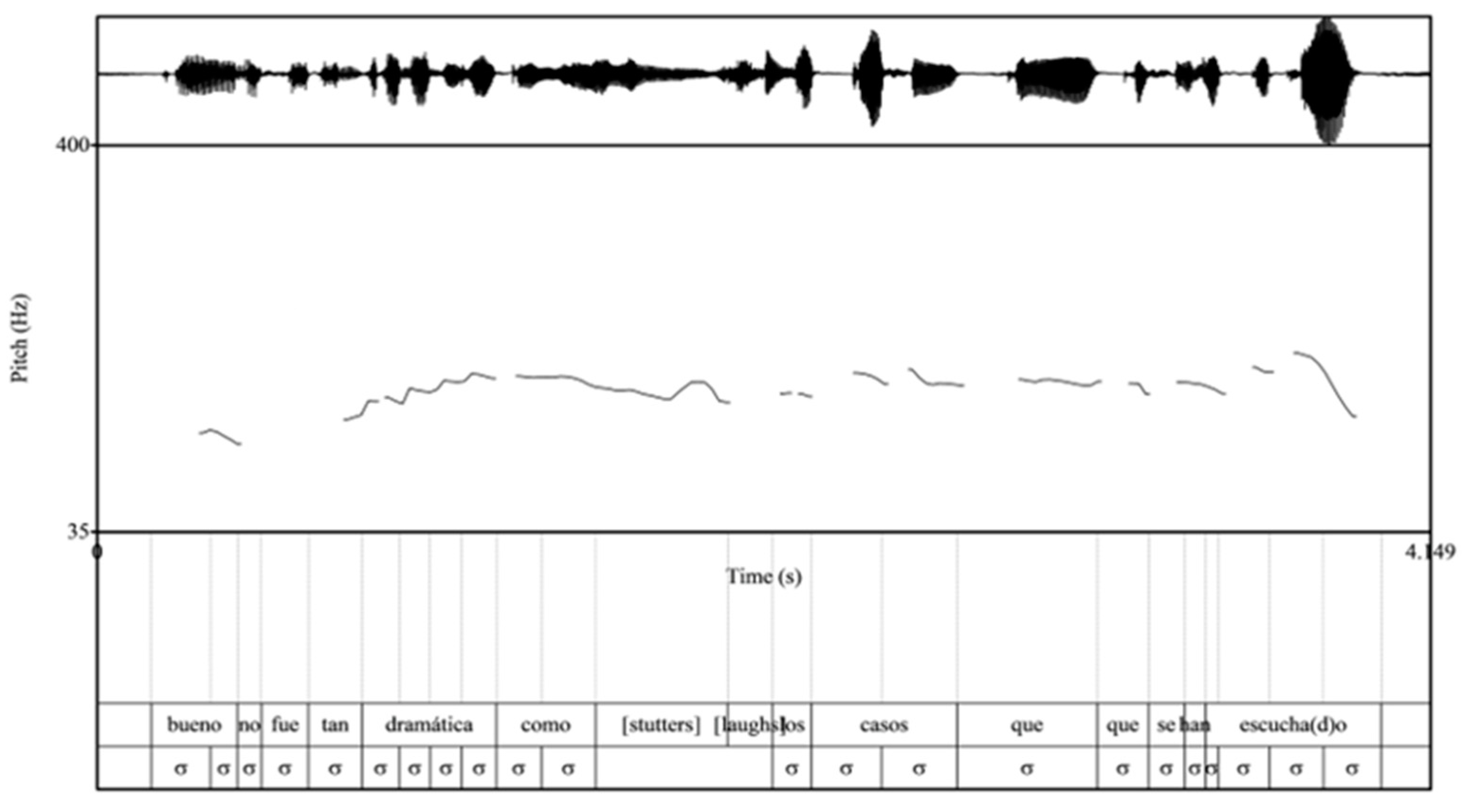

As a result, Hirschberg concludes that intonational meaning is highly dependent on the context in which speakers produce different contours. Ocampo’s (2003, 2010) findings on Spanish support this notion. He asserts that in natural speech, it is often impossible to determine the focus of the utterance by traditional definitions and that speakers often appear to subjectively determine what is important to highlight. Regardless of whether it is new information or contrasts with anything else in the discourse, speakers place prosodic prominence and/or focus wherever they deem appropriate, rather than always placing new or focused information near the end of utterances, as documented in traditional studies that work with grammaticality judgments and more controlled laboratory speech data (e.g., Zubizarreta 1998). In other words, language is adapted by speakers to use according to how they see a need for it. Based on this, in the case of Mapudungun and Chilean Spanish intonational plateaus, it is completely plausible that speakers should be able to highlight any amount of information according to the prominence that they place on any number of contextual and communicative needs regardless of what may be considered conventional. For example, Figure 22 and Figure 23 are examples that show speakers maintaining the high tonal register of the contours through breaks in their stream of speech without pitch reset where pitch reset would be expected.

Figure 22.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase broken by a pause Feymew fey kimam [pause] machi chumngechi kimki lawen filew chumngechi kimki pelu.

Figure 22.

Plateau on the Mapudungun phrase broken by a pause Feymew fey kimam [pause] machi chumngechi kimki lawen filew chumngechi kimki pelu.

| Feymew | fey | kim | -a | -m |

| So/thus | so | to know | unrealized action | -instrumental verbal noun |

| Machi | chumngechi | kim | -k(e) | -i | ||

| healer/spiritual leader | how | -to know | -habitual | -ind.3sing | ||

| lawen | filew | kim | -k(e) | -i | pe | |

| medicine | machi | to know | -habitual | -ind.3 sing | to see | |

| -lu | ||||||

| subject verbal noun | ||||||

| ‘…and, so upon the finding out (of the sickness) the machi, to know- about how to administer medicine, the machi knows how’. | ||||||

Figure 23.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase broken up by stuttering and laughter Bueno, no fue tan dramático como [stutters] [laughs] los casos que se han escuchado ‘well, it wasn’t as dramatic as [stutters] [laughs] some of the other instances that have been mentioned’.

Figure 23.

Plateau on the Spanish phrase broken up by stuttering and laughter Bueno, no fue tan dramático como [stutters] [laughs] los casos que se han escuchado ‘well, it wasn’t as dramatic as [stutters] [laughs] some of the other instances that have been mentioned’.

In Figure 22, the Mapudungun plateau begins to rise on the first syllable of the word kimki ‘s/he knows’, whereafter the speaker pauses and then continues at the same high tonal register without resetting until the final word pelu ‘upon seeing’. In the Spanish plateau in Figure 23, the pitch rises on tan ‘as’ and continues through dramática ‘dramatic’, where they then maintain the same high tonal register through the word como ‘as’, after which they stutter, then laugh, and then without resetting, continue the same high F0 until falling at the end of the word escuchado ‘heard’.