Abstract

We investigate an optimal reinsurance problem for an insurance company taking into account subscription costs: that is, a constant fixed cost is paid when the reinsurance contract is signed. Differently from the classical reinsurance problem, where the insurer has to choose an optimal retention level according to some given criterion, in this paper, the insurer needs to optimally choose both the starting time of the reinsurance contract and the retention level to apply. The criterion is the maximization of the insurer’s expected utility of terminal wealth. This leads to a mixed optimal control/optimal stopping time problem, which is solved by a two-step procedure: first considering the pure-reinsurance stochastic control problem and next discussing a time-inhomogeneous optimal stopping problem with discontinuous reward. Using the classical Cramér–Lundberg approximation risk model, we prove that the optimal strategy is deterministic and depends on the model parameters. In particular, we show that there exists a maximum fixed cost that the insurer is willing to pay for the contract activation. Finally, we provide some economical interpretations and numerical simulations.

MSC:

93E20; 91B30; 60G40; 60J60

1. Introduction

The insurance business requires the transfer of risks from the policyholders to the insurer, who receives a risk premium as a reward. In some cases, it could be convenient to cede these risks to a third party, which is the reinsurance company. From the operational viewpoint, a risk-sharing agreement helps the insurer reducing unexpected losses, stabilizing operating results, increasing business capacity and so on. By means of a reinsurance treaty, the reinsurance company agrees to indemnify the primary insurer (cedent) against all or part of the losses which may occur under policies which the latter issued. The cedent will pay a reinsurance premium in exchange for this service. Roughly speaking, this is an insurance for insurers. When subscribing a reinsurance treaty, a natural question is to determine the (optimal) level of the retained losses. Optimal reinsurance problems have been intensively studied by many authors under different criteria, especially through expected utility maximization and ruin probability minimization (see, e.g., [1,2,3,4,5,6] and references therein).

The main novelty of this article is that subscription costs are considered. Transaction costs represent the bureaucratic fixed costs necessary to run and manage an insurance company. The empirical impact of these costs on insurances choices has been highlighted in the actuarial literature (see, e.g., [7,8]). In practice, in the reinsurance context, when the agreement is signed, a fixed cost is usually paid in addition to the reinsurance premium. This aspect has not been investigated by nearly all the studies, except for those in [9,10]. In the former work, the authors discussed the reinsurance problem subject to a fixed cost for buying reinsurance and a time delay in completing the reinsurance transaction. They solved the problem considering a performance criterion with linear current reward and showed that it is optimal to buy reinsurance when the surplus lies in a bounded interval depending on the delay time. In the latter paper, under the criterion of minimizing the ruin probability, the original problem is reduced to a time-homogeneous optimal stopping problem. In particular, the authors showed that the fixed cost forces the insurer to postpone buying reinsurance until the surplus process hits a certain level.

Hence, the presence of a fixed cost is closely related to the possibility of postponing the subscription of the reinsurance agreement. This, in turn, involves an optimal stopping problem, which is attached to the optimal choice of the retention level, which is a well known stochastic control problem. The novelty of our paper consists in considering this mixed stochastic control problem under the criterion of maximizing the expected utility of terminal wealth. The strategy of the insurance company consists of the retention level of a proportional reinsurance and the subscription timing. When the contract is signed, a given fixed cost is paid and the optimal retention level is applied. For the purpose of mathematical tractability, we use a diffusion approximation to model the insurer’s surplus process (see [11]). The insurance company has exponential preferences and is allowed to invest in a risk-less bond.

As already mentioned, this setup leads to a combined problem of optimal stopping and stochastic control with finite horizon, which we solve by a two-step procedure. For theoretical studies on mixed control-stopping problems, we refer to, e.g., the works in [12,13,14]. First, we provide the solution of the pure reinsurance problem (with starting time equal to zero). Next, we discuss an optimal stopping time problem with a suitable reward function depending on the value function of the pure reinsurance problem. Differently to the works in [9,10], the associated optimal stopping problem turns out to be time-inhomogeneous and with discontinuous stopping reward with respect to the time. We provide an explicit solution, also showing that the optimal stopping time is deterministic. Moreover, we find that there are only two possible cases, depending on the model parameters. When the fixed cost is greater than a suitable threshold (whose analytical expression is available), the optimal choice is not to subscribe the reinsurance; otherwise, the insurer immediately subscribes the contract.

A recent related research can be found in [15] (see also references therein), where the problem of optimal dividends and reinsurance is formulated as a mixed classical-impulse stochastic control problem. The authors considered a fixed transaction cost when the dividends are paid out and solved the problem using the method of quasi-variational inequalities.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we describe the model and formulate the problem as a mixed stochastic control problem, i.e., a problem which involves both optimal control and stopping. In Section 3, we discuss the pure reinsurance problem (without stopping) by solving the associated Halmilton–Jacobi–Bellman equation. Section 4 is devoted to the reduction of the original (mixed) problem to a suitable optimal stopping problem, which is then investigated in Section 5. Here, we provide a verification theorem and solve the associated variational inequality. In Section 6, we give the explicit solution to the original problem and we discuss some economic implications of our results. Finally, in Section 7, some numerical simulations are performed in order to better understand the economic interpretation of our findings.

2. Problem Formulation

2.1. Model Formulation

Let be a finite time horizon and assume that is a complete probability space endowed with a filtration satisfying the usual conditions.

Let us denote by the surplus process of an insurance company. There is a wide range of risk models in the actuarial literature (see, e.g., [11,16]). In the Cramér–Lundberg risk model, the claims arrival times are described by the sequence of claims arrival times , with -almost everywhere , while the corresponding claim sizes are given by . In particular, the number of occurred claims up to time is equal to

and it is assumed to be a Poisson process with constant intensity , independent of the sequence . Moreover, are independent and identically distributed random variables with common probability distribution function , , having finite first and second moments denoted by and , respectively. In this context, the surplus process is given by

where is the initial capital and denotes the gross risk premium rate. We can show that for any

In this paper, we use the diffusion approximation of the Cramér–Lundberg model (1) (see, e.g., [16]). Precisely, we assume that the surplus process follows this stochastic differential equation (SDE):

where is a standard Brownian motion, and p denotes the insurer’s net profit, that is . In particular, under the expected value principle (see, e.g., [11]), we have that and hence , with representing the insurer’s safety loading.

We allow the insurer to invest her surplus in a risk-free asset with constant interest rate :

hence the wealth process evolves according to

The explicit solution of the SDE (2) is given by the following equation:

Now, let denote an -stopping time. At time , the insurer can subscribe a proportional reinsurance contract with retention level , transferring part of her risks to the reinsurer. More precisely, u represents the percentage of retained losses, so that means full reinsurance, while is equivalent to no reinsurance. To buy a reinsurance agreement, the primary insurer pays a reinsurance premium . When the reinsurance contract is signed at time , the Cramér–Lundberg risk model (1) is replaced by the following equation:

Under the expected value principle, we have that , , with the reinsurer’s safety loading satisfying (preventing the insurer from gaining a risk-free profit).

Let us denote by the reserve process in the Cramér–Lundberg approximation associated with a given reinsurance strategy when the reinsurance contract is signed at time . Following Eisenberg and Schmidli [17], under the expected value principle, follows

where denotes the reinsurer’s net profit. We set (non-cheap reinsurance). The wealth process under the strategy evolves according to this SDE:

which admits this explicit representation:

We assume that a constant fixed cost is paid when the reinsurance contract is subscribed. The insurer decides when the reinsurance contract starts and which retention level is applied. Hence, the insurer’s strategy is a couple , with . Let be the indicator process of the contract starting time. For -a.s., the total wealth associated with a given strategy is given by

while on the event we have that

where X satisfies Equation (2).

Equation (7) can be written more explicitly as

where X and satisfy Equations (2) and (5), respectively.

In our setting, the null reinsurance corresponds to the choice , -a.s., to which we associate the strategy and

2.2. The Utility Maximization Problem

The insurers’ objective is to maximize the expected utility of the terminal wealth:

where is the utility function representing the insurer’s preferences and the class of admissible strategies (see Definition 1).

We focus on CARA (Constant Absolute Risk Aversion) utility functions, whose general expression is given by

where is the risk-aversion parameter. This utility function is highly relevant in economic science and particularly in insurance theory. Indeed, it is commonly used for reinsurance problems (e.g., see [5] and references therein).

The optimization problem is a mixed optimal control problem. That is, the insurer’s controls involve the timing of the reinsurance contract subscription and the retention level to apply.

Definition 1

(Admissible strategies). We denote by the set of admissible strategies , where τ is an -stopping time such that and is an -predictable process with values in . Let us observe that the null strategy is included in . When we want to restrict the controls to the time interval , we use the notation .

Proposition 1.

Let , then

Proof.

Taking into account the expression (3), we get

and denoting by C a generic constant (possibly different from each line to another)

□

3. The Pure Reinsurance Problem

To have a self-contained article, in this section, we briefly investigate a pure reinsurance problem, which corresponds to the problem (10) with fixed starting time . Precisely, we deal with

where denotes the class of admissible strategies , which are all the -predictable processes with values in . Let us denote by the value function associated to this problem, that is

with denoting the restriction of to the time interval and denotes the process satisfying Equation (5) with initial data . It is well known that the value function (13) can be characterized as a classical solution to the associated Hamilton–Jacobi–Bellman (HJB) equation:

where, using Equations (4) and (5), the generator of the Markov process is given by

with denoting the class of continuous functions, with continuous first-order partial derivative with respect to the first (time) variable and continuous second-order derivative with respect to the second (space) variable.

Under the ansatz , the HJB equation reads as

where

Solving the minimization problem, we find the unique minimizer:

Under the additional condition

simplifies to

Using this expression, we readily obtain that

4. Reduction to an Optimal Stopping Problem

We can show that the mixed stochastic control problem (11) can be reduced to an optimal stopping problem. Let us denote by is the set of -stopping times such that .

Theorem 1.

Proof.

We first prove the inequality

Taking the infimum over on both side leads to the desired inequality. The other side of the inequality is based on the fact that there exists , given in (16) optimal for the problem (13). Indeed, consider the strategy where is arbitrary chosen in . Then,

Taking the infimum over on the right-hand side gives that

and hence the equality (24).

5. The Optimal Stopping Problem

In this section, we discuss the optimal stopping problem (24):

Now, denote by the Markov generator of the process :

with .

Remark 2.

From the theory of optimal stopping (see, e.g., [18]), when the cost function is continuous and the value function

is sufficiently regular, it can be characterized as a solution to the following variational inequality:

This is a free-boundary problem, whose solution is the function and the so-called continuation region, which is defined as

Moreover, it is known that the first exit time of the process from the region

provides an optimal stopping time.

In our optimal stopping problem (24), the cost function is

which is not continuous on , hence the classical theory on optimal stopping problems does not directly apply.

In view of the preceding remark, we now prove a verification theorem which applies to our specific problem.

Theorem 2 (5)

(Verification Theorem). Let be a function satisfying the assumptions below and (the continuation region) be defined by

Suppose that the following conditions are satisfied.

There exists such that .

, φ is w.r.t t in and , separately, and with respect to ;

and ;

φ is a solution to the following variational inequality

The family is uniformly integrable.

Moreover, let be the first exit time from the region of the process , that is

with the convention if the set on the right-hand side is empty. Then, on and is an optimal stopping time for problem (24).

Proof.

For any , let us take the sequence of stopping times such that . We first prove that

Due to the specific form of the continuation region, we have two cases. If , since , applying Dynkin’s formula (notice that we use a localization argument, so that is the first exit time of a bounded set and, as a consequence, is not required to have a compact support (see [18], Theorem 7.4.1)), we get that for any arbitrary stopping time

If , we have again by Dynkin’s formula, since , that

and, similarly, since ,

hence (31) is proved.

Now, letting in (31), recalling that , and using Fatou’s Lemma, we get that

hence , . To prove the opposite inequality, we consider four different cases.

- If the stopping region is not empty, that is , , we know that , hence , which implies and is optimal for problem (24).

- If the stopping region is not empty, for , we have that , otherwise, by continuity of both the functions, if (or ), the same inequality holds in a neighborhood of , which contradicts that , . Then, and is optimal for problem (24).

- If the continuation region is not empty, that is , , repeating the localization argument with the stopping time , we getas a consequence and is optimal for problem (24).

- Finally, for , by assumption, , , is optimal for problem (24) and this concludes the proof.

□

Lemma 1.

Let g be as defined in Equation (22). The families and are uniformly integrable.

Proof.

Recalling that by (19), we have that , hence the statement follows by the uniformly integrability of the family

It is well known that, if for any arbitrary and any stopping time ,

then the proof is complete. To this end, we observe that

□

The guess for the continuation region given in Assumption 1 of the verification Theorem follows by the next result.

Lemma 2.

The set

is included in the continuation region, that is

Moreover, the following equation holds:

where

In particular, only three cases are possible, depending on the model parameters:

- 1.

- Ifthen and , so that , implying that .

- 2.

- Ifthen and ; in this case .

- 3.

- Ifthen and , so that .

Proof.

First, let us observe that and the family is uniformly integrable by Lemma 1. Now, choose and let be a neighborhood of with , where denotes the first exit time of from B. Then, by Dynkin’s formula

Hence, and .

Using a change of variable , we can rewrite the inequality as

Since , the associated equation admits two different solutions, so that the inequality (34) is satisfied by

Depending on the model parameters, we can see that only the three cases above are possible. Equivalently, if and only if . □

Remark 3.

We need the following preliminary result to provide an explicit expression for the value function of the problem (24).

Lemma 3.

The function , , with C any positive constant and g as given in Equation (22), is a solution to the partial differential equation (PDE) , .

In particular, g is a solution to the PDE with boundary condition .

Proof.

Using the ansatz , we can reduce the PDE to the following equation:

which is equivalent to this ordinary differential equation (ODE):

where the function h is given in (21).

Since the solution of the ODE is , we get the expression of as above. Finally, setting , g satisfies the PDE above with the terminal condition . □

Before proving the main result of this section, which is Theorem 3, we compare , given in (22), with .

Lemma 4.

Let

then we distinguish two cases:

- If , then .

- If , then there exists such that and .

Proof.

Let us observe that the inequality can be written as

that is

We distinguish three cases:

- (i)

- When , we have that by Remark 3 and it easy to verify that H is increasing in , while it is decreasing in . Hence, it takes the maximum value at . As a consequence, if we have that , being .Otherwise, if there exists such that , that is , and , that is .

- (ii)

- When , by Lemma 2 we get that H is increasing in and we can repeat the same arguments as in the previous case to distinguish the two casese and , obtaining the same results.

- (iii)

- When , by Remark 3, we know that H is decreasing in , so that , that is , . Moreover, in this case, .

Summarizing, we obtain our statement. □

We now prove some properties of the continuation region.

Proposition 2.

Let

Then, we distinguish two cases:

- If , then .

- If , then , where is the unique solution to equation

Proof.

We apply Lemma 4. In Case 1, we have that , that is . In Case 2, we have that , which implies , and this concludes the proof. □

Now, we are ready for the main result of this section.

Theorem 3.

Let H be given in (35). The solution of the optimal stopping problem (24) takes different forms, depending on the model parameters. Precisely, we have two cases:

- (1)

- If , then the continuation region is , the value function isand is an optimal stopping time.

- (2)

- If , then , where is the unique solution to , the value function isand , given byis an optimal stopping time.

Proof.

We prove the two cases separately, applying Theorem 2 to each one.

Case 1

The continuation region is by Proposition 2, hence Assumption 1 of Theorem 2 is fulfilled. Moreover, . Observing that

Assumption 2 of Theorem 2 is clearly matched. Assumption 3 is implied by Lemma 4. Moreover, the variational inequality (30) (Assumption 4) is fulfilled by Lemma 3. Finally, by Lemma 1, the last condition in Theorem 2 is fulfilled.

Case 2

clearly satisfies the first assumption of Theorem 2. Taking

observing that Lemma 4 ensures the existence of such that when , the smoothness conditions of the second assumption are matched. Moreover, according to Lemma 4, and Assumption 3 is fulfilled. That the variational inequality (30) is satisfied by is a consequence of the results of Section 3 and Lemma 3. Finally, Lemma 1 implies Assumption 5 of Theorem 2 and the proof is complete. □

6. Solution to the Original Problem

As a direct consequence of the results obtained in the previous section and Theorem 1, we provide an explicit solution to the optimal reinsurance problem under fixed cost given in (11).

Theorem 4.

Let us define

Two cases are possible, depending on the model parameters:

Proof.

Let us observe that, using Remark 1,

and the condition is equivalent to

while the condition can be written as . Thus, follows by Remark 1. Then, the statement is a consequence of Theorem 3. □

Let us briefly comment the two cases of Theorem 4. Case 1 corresponds to no reinsurance. That is, the insurer is not willing to subscribe a contract at any time of the selected time horizon. Besides the insurer, this result is relevant for the reinsurance company. We prove that there exists a threshold (see Equation (39)), which represents the maximum initial cost that the insurer is willing to pay to buy reinsurance. If the reinsurer chooses a subscription cost higher than , then the insurer will not buy protection from her.

In Case 2, at any time , the insurer immediately subscribes to the reinsurance agreement if the time instant has not passed, applying the optimal retention level from that moment on; otherwise, if , no reinsurance will be bought.

We notice that it is never optimal to wait for buying reinsurance. That is, it is convenient either to immediately sign the contract, or not to subscribe at all.

In particular, at the starting time , given an initial wealth , we have these cases:

- (1)

- If , then , that is no reinsurance is purchased.

- (2)

- If , then , that is the optimal choice for the insurer consists in stipulating the contract at the initial time, selecting the optimal retention level (as in the pure reinsurance problem).

By Expression (39), we can show that is increasing with respect to and , while it is decreasing with respect to q. More details are given in the next section by means of numerical simulations.

Another relevant result for the reinsurance company is the following.

Proposition 3.

For any fixed cost , there exists (depending on K) such that

- If , thenand , that is no reinsurance is purchased.

Proof.

Following Theorem 4 and its proof, we can write the condition as

To simplify our computations, let us consider this inequality for any . The discriminant must be positive, otherwise the existence of in Theorem 4 is no long guaranteed. The solutions of the associated equations are

Since

only is relevant because of Condition (15). is a consequence of the existence of in Theorem 4. If was not positive, then for any value of and this would contradict Theorem 4. Setting concludes the proof. □

The last result is interesting for the reinsurer. In Section 3, we state that the condition (see Equation (15)) is required in order that the reinsurance agreement is desirable. In presence of a fixed initial cost, we now know that there exists a threshold , which is smaller than , such that the insurer will never subscribe the contract if .

Remark 4.

Recalling that (see Section 2), we can give a deeper interpretation of the previous result. Indeed, we prove the existence of a maximum safety loading , which cannot be exceeded by the reinsurer, otherwise the reinsurance contract will not be subscribed.

7. Numerical Simulations

In this section, we use some numerical simulations to further investigate the results obtained in Section 6. Unless otherwise specified, all simulations are performed according to the parameters of Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

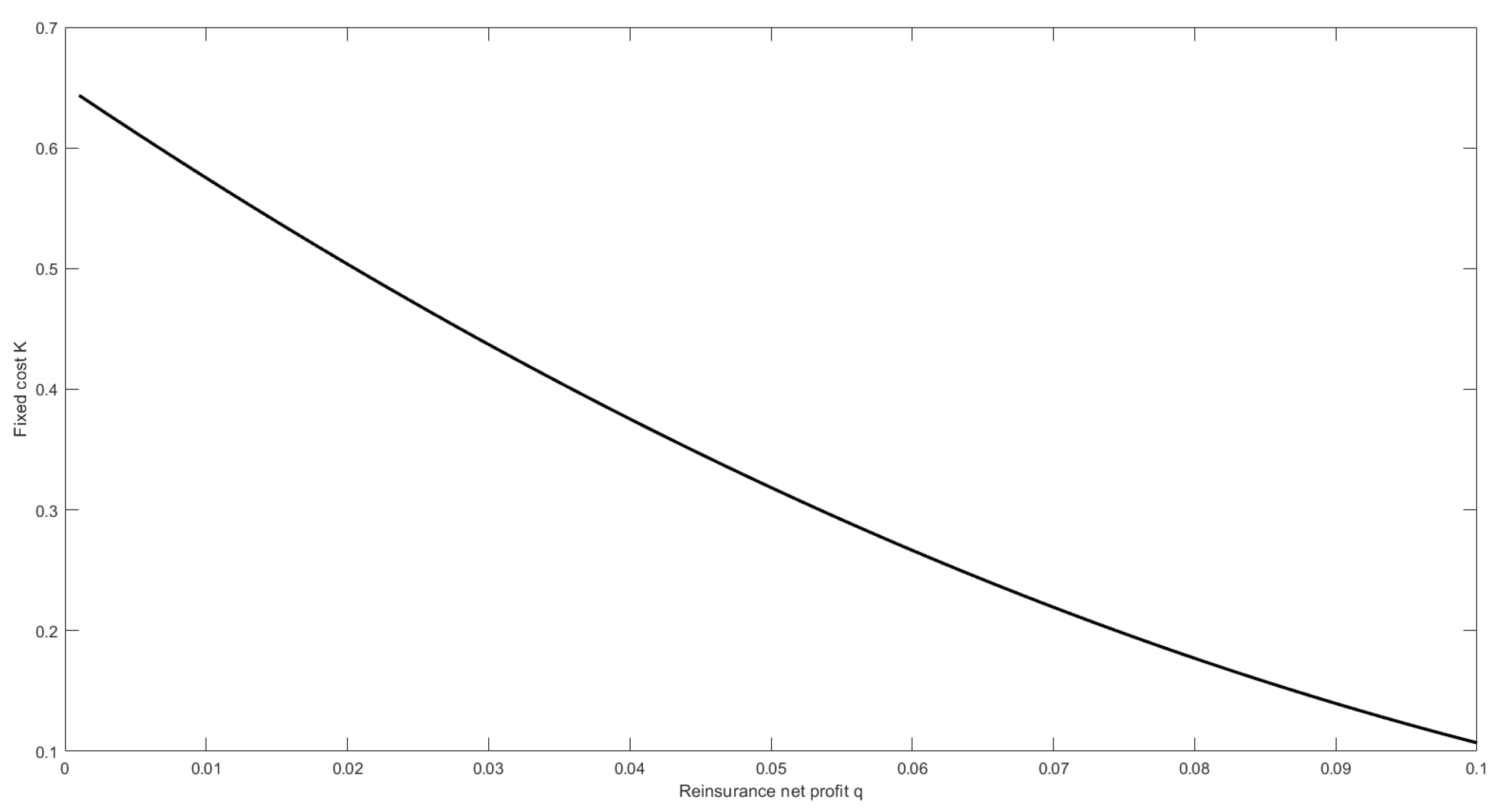

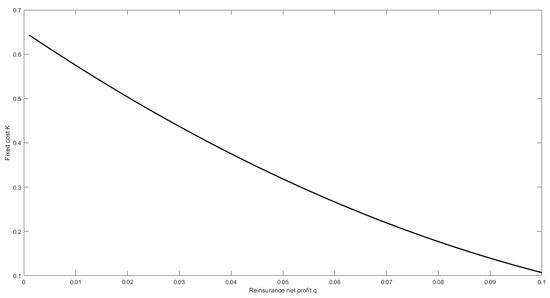

We illustrate above how the threshold in Equation (39) is relevant for the insurer as well as for the reinsurer. Indeed, turns out to be the maximum subscription cost that the insurer is willing to pay. The next pictures show how this threshold is influenced by the model parameters. As expected, if the reinsurer increases her net profit q, then the fixed cost should decrease (see Figure 1). In practice, recalling that , if the reinsurer increases her safety loading , the subscription cost should be selected from a smaller range . Otherwise, no reinsurance contract will be stipulated. Let us notice that, according to Equation (16), any increase of implies a larger retention level as well.

Figure 1.

The effect of the reinsurer’s net profit q on .

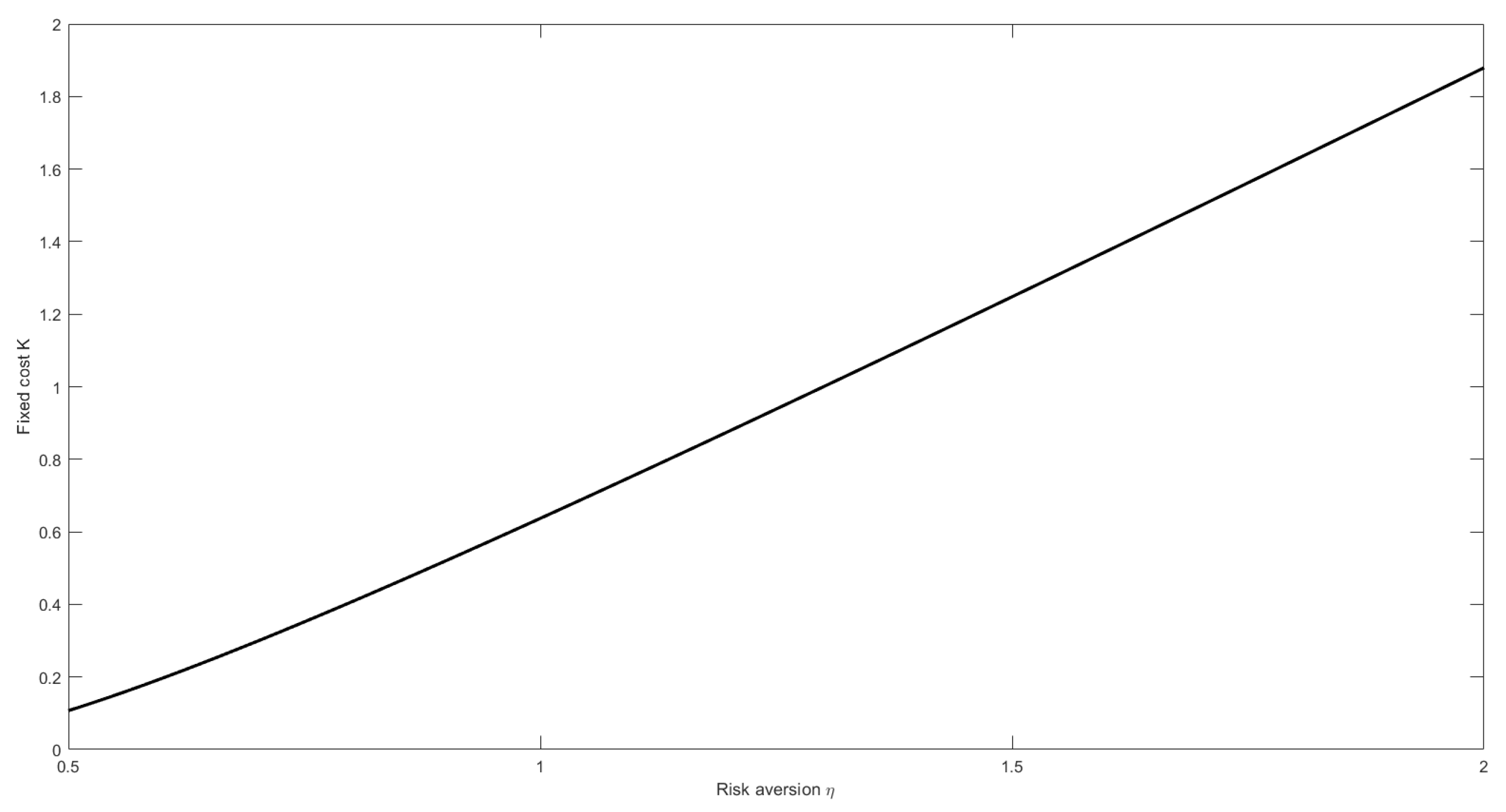

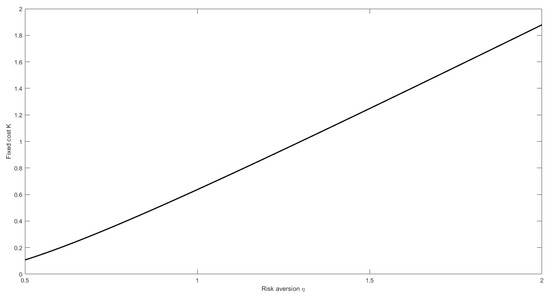

As illustrated in Figure 2, when the insurer is more risk averse, she is willing to pay a higher fixed cost. This result reinforces the practical implications of Equation (16), which implies that the more risk averse is the insurer, the larger protection she will buy.

Figure 2.

The effect of the risk-aversion parameter on .

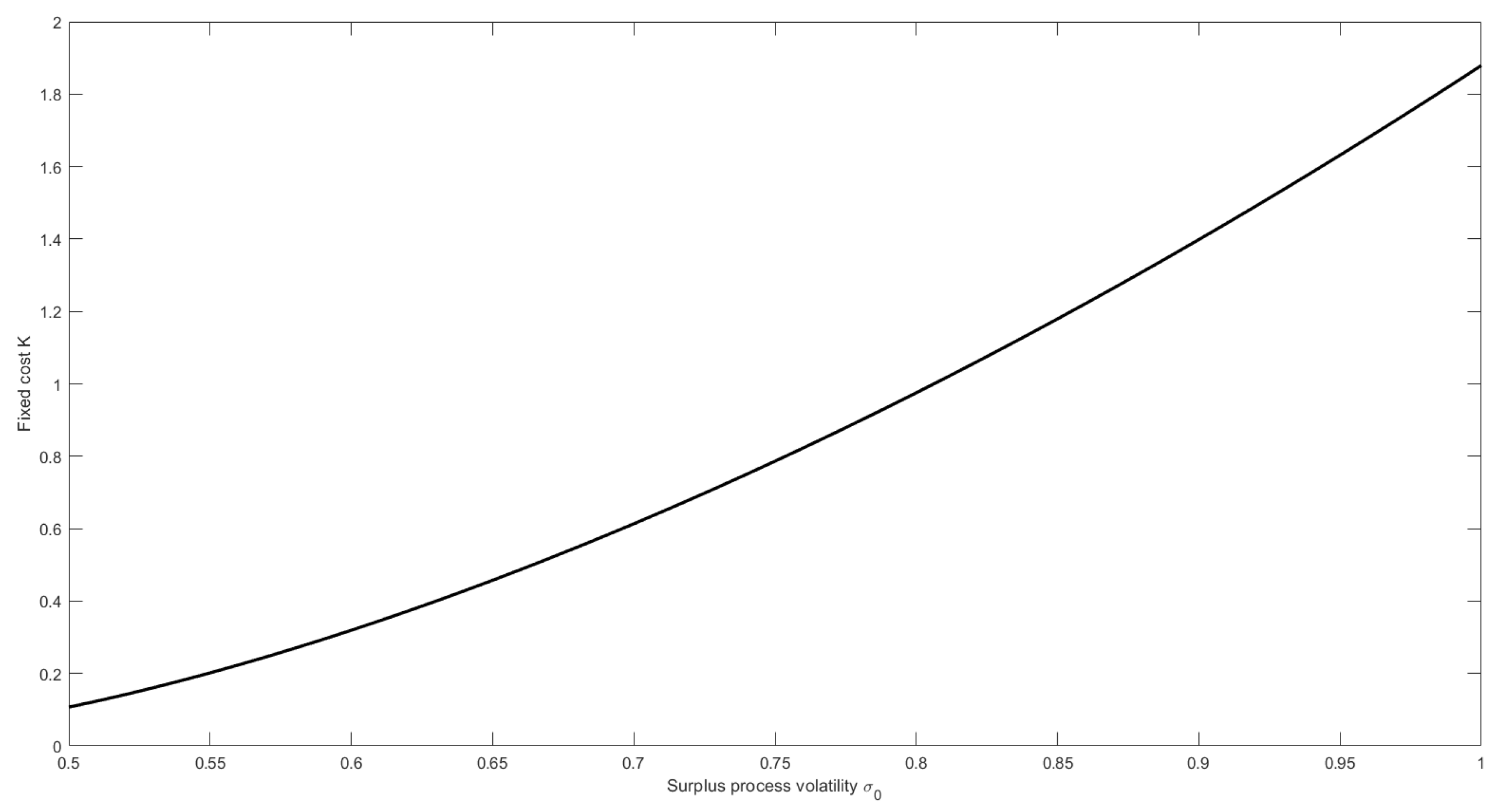

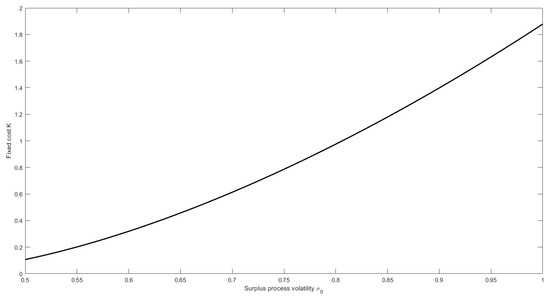

Figure 3 shows the effect of the potential losses. When they increase, that is is high, then the insurer is going to pay high fixed cost in order to obtain protection.

Figure 3.

The effect of the volatility parameter on .

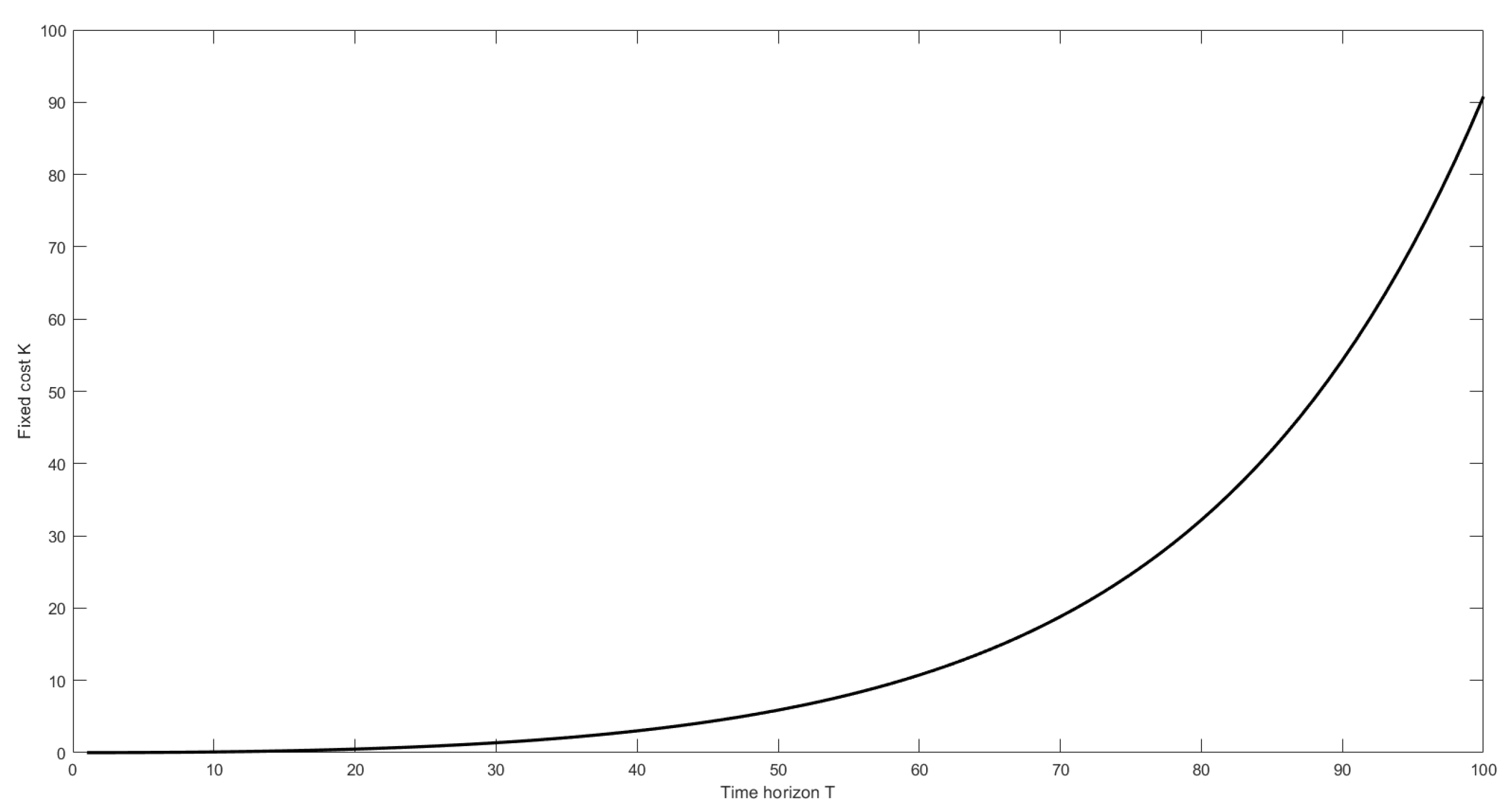

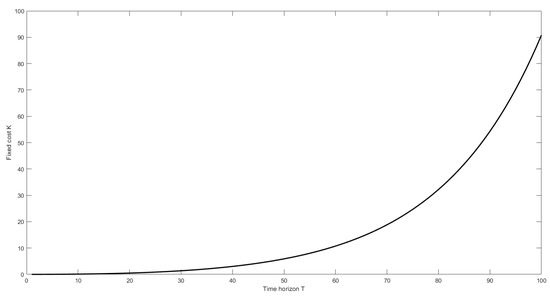

Finally, Figure 4 show that the larger the insurer’s time horizon is, the higher the fixed cost will be.

Figure 4.

The effect of the time horizon T on .

8. Conclusions

We investigate the optimal reinsurance problem under the assumption that a transaction cost is paid when the agreement is signed. The insurer has to choose the optimal starting time of the reinsurance contract, as well as the optimal retention level to be applied from that moment on. We solve the resulting mixed optimal control/optimal stopping time problem using a two-step procedure. We find that the optimal strategy is deterministic (see Theorem 4). Moreover, we prove the existence of a maximum fixed cost (see Equation (39)) that the insurer is willing to pay. That is, whenever a fixed cost is chosen by the reinsurer, the insurer will retain all her losses. In the last section, we further analyze how the model parameters affect that maximum subscription cost.

Some future research could be focused on the study of the optimal reinsurance problem with fixed cost under either different optimization criteria or different types of contract.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and C.C.; Investigation, M.B. and C.C.; Methodology, M.B. and C.C.; Writing—original draft, M.B. and C.C.; Writing—review and editing, M.B. and C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are partially supported by the GNAMPA Research Project 2020 (A class of optimization problems in actuarial and economic field) of INdAM (Istituto Nazionale di Alta Matematica).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- De Finetti, B. Il problema dei “pieni”. G. Ist. Ital. Attuari 1940, 11, 1–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bühlmann, H. Mathematical Methods in Risk Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, H. Entscheidungskriterien für den zusammengesetzten Poisson-Prozess. Schweiz. Verein. Versicherungsmath. Mitt. 1969, 69, 185–228. [Google Scholar]

- Irgens, C.; Paulsen, J. Optimal control of risk exposure, reinsurance and investments for insurance portfolios. Insur. Math. Econ. 2004, 35, 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachetta, M.; Ceci, C. Optimal proportional reinsurance and investment for stochastic factor models. Insur. Math. Econ. 2019, 87, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brachetta, M.; Ceci, C. Optimal Excess-of-Loss Reinsurance for Stochastic Factor Risk Models. Risks 2019, 7, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogh, G. The Transactions Cost Theory of Insurance: Contracting Impediments and Costs. J. Risk Insur. 1989, 56, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braouezec, Y. Public versus private insurance system with (and without) transaction costs: Optimal segmentation policy of an informed monopolist. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 1907–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egami, M.; Young, V.R. Optimal reinsurance strategy under fixed cost and delay. Stoch. Process. Their Appl. 2009, 119, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhou, M.; Yin, C. Optimal reinsurance with both proportional and fixed costs. Stat. Probab. Lett. 2015, 106, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidli, H. Risk Theory; Springer Actuarial, Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Karatzas, I.; Wang, H. Utility maximization with discretionary stopping. Siam J. Control. Optim. 2000, 39, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, C.; Bassan, B. Mixed Optimal Stopping and Stochastic Control Problems with Semicontinuous Final Reward for Diffusion Processes. Stochastics Stoch. Rep. 2004, 76, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, B.; Touzi, N. Weak Dynamic Programming Principle for Viscosity Solutions. Siam J. Control. Optim. 2011, 49, 948–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yuen, K.C.; Wang, W. Optimal reinsurance and dividends with transaction costs and taxes under thinning structure. Scand. Actuar. J. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandell, J. Aspects of Risk Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, J.; Schmidli, H. Optimal control of capital injections by reinsurance in a diffusion approximation. Blätter DGVFM 2009, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ∅ksendal, B. Stochastic Differential Equations; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).