Abstract

Background: While there is evidence on the effectiveness of optimized treatment processes for patients receiving hip and knee endoprostheses, feasibility in various settings has not been adequately investigated. The multicenter PROMISE Trial (Process optimization by interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral care using the example of patients with hip and knee prostheses) was set up to fill this gap. Methods: A complex optimized process was implemented in three German hospitals offering different levels of care and five cooperating rehabilitation centers. For the feasibility question, data on 19 parameters characterizing the defined process were collected. The extent of cross-sectoral collaboration was a special focus. Results: The data show, for almost all parameters in all facilities, an implementation rate of more than 80% with missing data below 5%, n = 1887 study participants. A total of 96.8% attended a rehabilitation program, and for 29.2% rehabilitation took place in a PROMISE-collaborating facility. Conclusions: Adherence to the defined and well-documented process was very high in all three organizationally very different hospitals, so that feasibility is given and transferability of the concept can be assumed. An exception was the targeted integration of rehabilitation into the treatment process. The goal of cross-sectoral networking could only be partially achieved.

1. Introduction

For quality purposes, the German Federal Joint Committee (Available online: https://www.g-ba.de/ (accessed on 25 February 2022)) sets minimum requirements for the quality of structures, processes and outcomes for certain treatments in Germany. However, a generally binding standard of care for patients undergoing hip (THA) or knee replacement (TKA) is missing so far and AWMF guidelines exist only for indication for THA [1] and TKA [2]. This is not an unimportant deficit, as in Germany alone, >200,000 initial hip arthroplasties [3] and >150,000 initial knee arthroplasties [4] were conducted in 2020, making THA and TKA among the most common surgeries. Process optimization can improve outcomes after surgery [5] and due to the large number, even small clinical and economic improvements can add up to very relevant factors. A prerequisite for implementing an optimized treatment pathway on a broad scale is that it must be independent of specific conditions. To this end, it must be equally feasible in very different settings. This question has not yet been sufficiently investigated to the best of the authors’ knowledge. Therefore, the PROMISE multicenter trial [6] was designed to develop and prove a complex cross-sectoral optimized protocol for THA and TKA that meets this requirement.

In Germany, the possibility of rehabilitation (usually a 3-week program [7]) following THA and TKA is set out in law (§ 40 Sozialgesetzbuch). However, this takes place in separate rehabilitation facilities, which carries the risk of insufficient coordination, a lack of common therapeutic goals, incomplete information flow, and separate data collection. To avoid this risk, the PROMISE Trial aimed at cross-sectoral care, implemented jointly by hospitals and rehabilitation facilities.

In this paper, we present whether the process was successfully established equally in hospitals offering different levels of care at various locations in Germany and how the integration of various rehabilitation facilities and the cross-sectoral collaboration succeeded.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

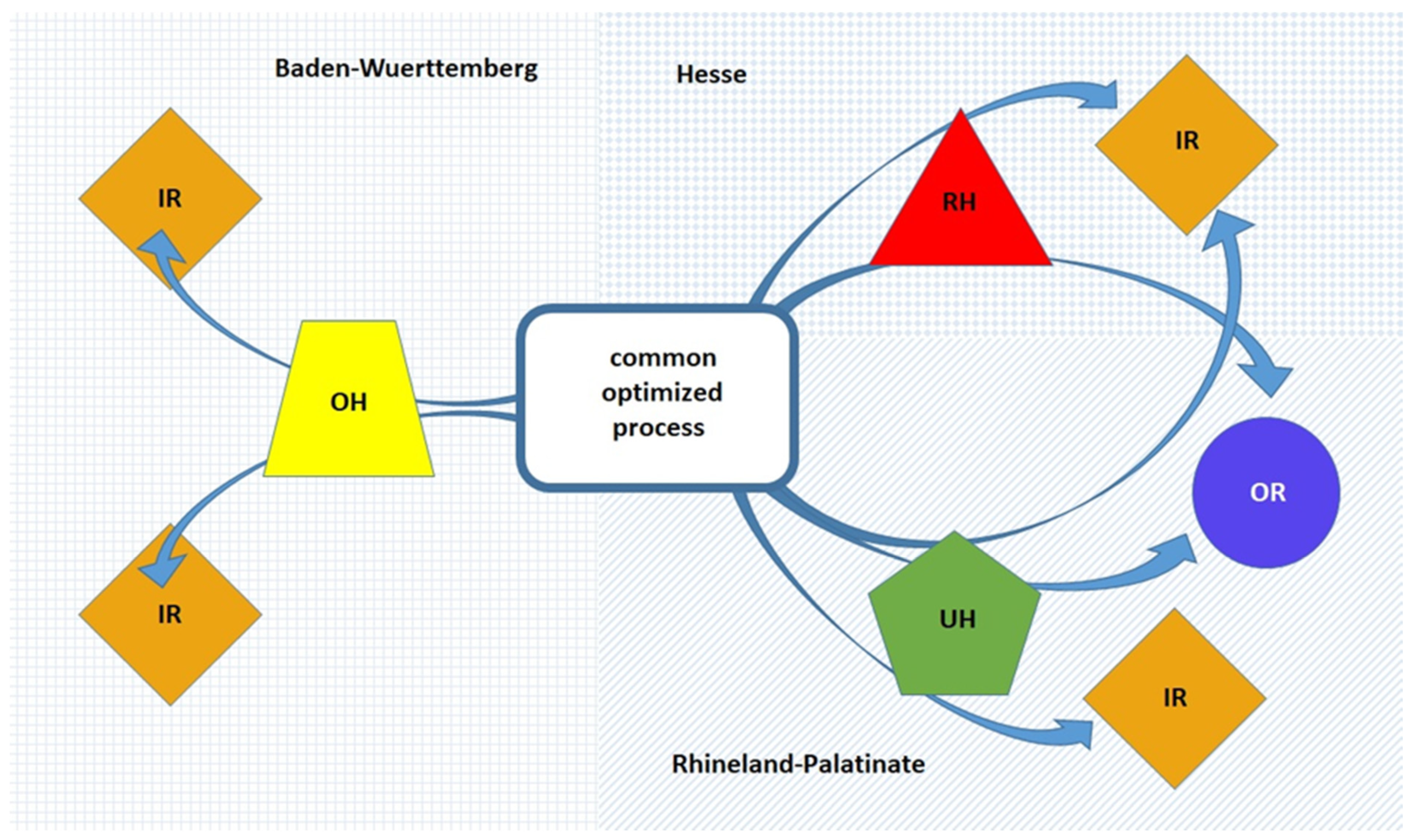

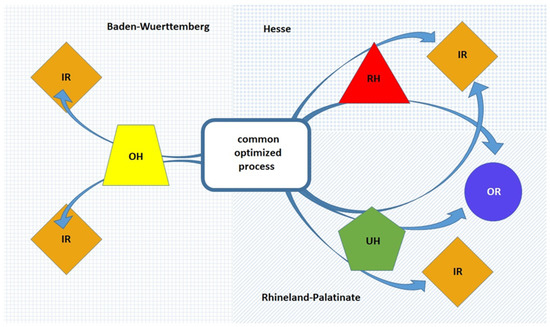

In order to prove the requirement of transferability, three hospitals offering different levels of care, a regional hospital (RH), an orthopedic specialist hospital (OH), and a tertiary referral university hospital (UH), including all required clinical departments, and five rehabilitation facilities (one inpatient and four outpatient) were involved in the trial. The facilities were located in three different parts of Germany (Rhineland-Palatinate, Baden-Wuerttemberg, and Hesse) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of patient flows in the PROMISE project. RH = regional hospital, OH = orthopedic-specialist hospital, UH = tertiary referral university hospital, IR = inpatient rehabilitation facility, OR = outpatient rehabilitation facility, located in three different parts of Germany (Rhineland-Palatinate, Baden-Wuerttemberg, and Hesse).

Starting in March 2017, an interdisciplinary panel, including experts from all professions and facilities involved, defined a common optimized standard of care. Subsequently, the protocol was established and consolidated in the different facilities equally.

At its core, the optimized PROMISE process consists of evidence-based interventions that are also recommended by the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society for the treatment of TKA and THA [8,9]. Only preoperative optimization advice of smoking cessation for 4 weeks or more prior to surgery and alcohol cessation programs for alcohol abusers were not part of the PROMISE Trial. These two components could not be subsequently included in the study protocol, as patient inclusion was already well under way at the time the recommendations were published. The ERAS recommendations on preoperative fasting, standard anesthetic protocol, perioperative oral analgesia, maintaining normothermia, antithrombotic prophylaxis treatment, perioperative fluid management, postoperative nutritional care, criteria-based discharge and continuous improvement and audit are already firmly established standards and have been set as SOPs without alternatives. Compliance with these recommendations was therefore not recorded in detail during the trial.

The ERAS recommended measures are accompanied by interventions that support the process (patient specifies a specific activity/participation goal; patient has a coach, a personal confidant, who accompanies him through the process; patient management and social services incorporated are in the process) and that reduce barriers to mobility (no urinary catheter, no pneumatic tourniquet [TKA], no drains). In order to reduce the possible risks of poor results, screening was performed to identify seniors at risk (ISAR screening [10]) and psychosomatic risk (Patient Health Questionnaire-4 [11]). To bridge the gap between hospitals and rehabilitation centers, a common central database was established under the rules of the German Federal Data Protection Act (Bundesdatenschutzgesetz). Here, all patient-related study data were available electronically. Some of the data were entered directly into the system, some were recorded paper-based and transferred, and some were automatically imported from other databases.

For process evaluation in the different hospitals, data were collected on adherence to the defined process by 19 parameters (see Tables 2 and 3 and [6]). The extent of cross-sectoral collaboration between hospitals and rehabilitation centers was measured by how many patients started their rehabilitation program in one of the participating rehabilitation centers and how often the common database was used.

Preconditions for inclusion were that the patient suffering from osteoarthritis met standardized criteria for elective THA or TKA [12] and that they were able to understand the nature and extent of the study.

Exclusion criteria were: life expectancy less than 1 year (e.g., advanced cancer), any conditions that might preclude elective surgical intervention, and medical or psychological factors that would prevent them from participating or providing written informed consent.

The PROMISE Trial is described in detail in the study protocol [6]. The protocol was approved by the ethics committees of Rhineland-Palatinate [837.533.17 (11367)], Baden-Wuerttemberg [B-F-2018-042], and Hesse [MC 84/2018] and registered within the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00013972). The trial was supported by a grant from the German Federal Joint Committee (01NVF16015).

2.2. Statistical Methods

For presentation of the study population at baseline, descriptive statistics (mean, median, and percentages) were used. For the evaluation of the feasibility, descriptive statistics of the 19 parameters were performed; presented are the percentages for confirmed and missing cases. Percentages for non-confirmed cases can been calculated as 100% minus confirmed and missing cases.

3. Results

3.1. Study Subjects

After implementation of the process, 1887 patients indicated for joint replacement due to arthritis of the hip or knee were enrolled between May 2018 and March 2020: in RH, n = 441 (23.4%); in OH, n = 916 (48.5%); and in UH n = 530 (28%) patients; 951 (50.4%) with THA and 922 (49.4%) with TKA.

Patients were 67 years old on average (range 23–93 years, standard deviation [SD] 10.1); 837 (44%) patients were male and 1050 (56%) female. The BMI on average was 29.3 (SD 5.7) and the ASA score was on average 2.2 (SD 0.6) across all centers; this was approximately the same for both TKA and THA patients in each of the hospitals. In RH, the ASA average was 2.2, in OH it was 2.1, and in UH 2.5. The median was 2 in all hospitals for both patient categories, except for THA patients from UH (ASA 3).

Fourteen comorbidities were recorded: heart disease, hypertension, stroke, leg pain on walking due to poor circulation, lung disease, diabetes, kidney disease, nervous system disease (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis), liver disease, cancer within the past 5 years, depression, spinal disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and anemia. Overall, 1472 (78%) patients reported suffering from at least one comorbidity; on average, they suffered from 1.6 comorbidities (median 1). In RH the average was 2.0 comorbidities (median 2), in OH 1.3 (median 1), and in UH 1.9 (median 2). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

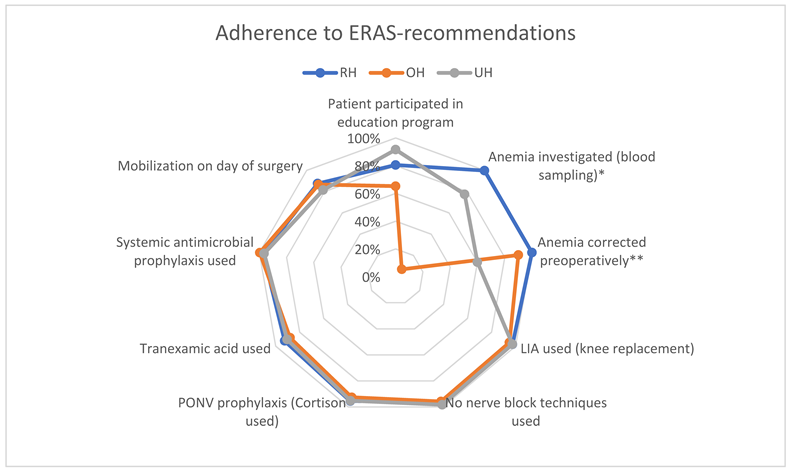

3.2. ERAS Recommendations

Adherence to the ERAS recommendations in the three different hospitals and overall recorded in our trial is shown in Table 2, by confirmed parameter data. The data show an implementation rate of >80% and missing data of <5% for almost all parameters at all centers. For the parameters ‘Participation in educational program’ (OH, 65.2%), ‘Anemia investigated’ (OH, 6.9%; UH, 77.5%) and ‘Anemia corrected preoperatively’ (UH, 60%), the confirmation was <80%. For the parameter ‘Anemia investigated’, a blood draw was defined in the data collection. In OH, a bloodless hemoglobin determination was performed before the blood draw. Only patients whose bloodless measurement shows a Hb < 13 gm/dL received a blood draw for anemia diagnostics there.

Table 2.

Overview of adherence to ERAS recommendations by parameters screened, both overall and in the various hospitals (missing values in brackets). Implementation rates less than 80% and missing data over 5% are highlighted in gray.

For the parameters ‘Participation in educational program’ (OH) and ‘Mobilization on day of surgery’ (OH) missings were >5%.

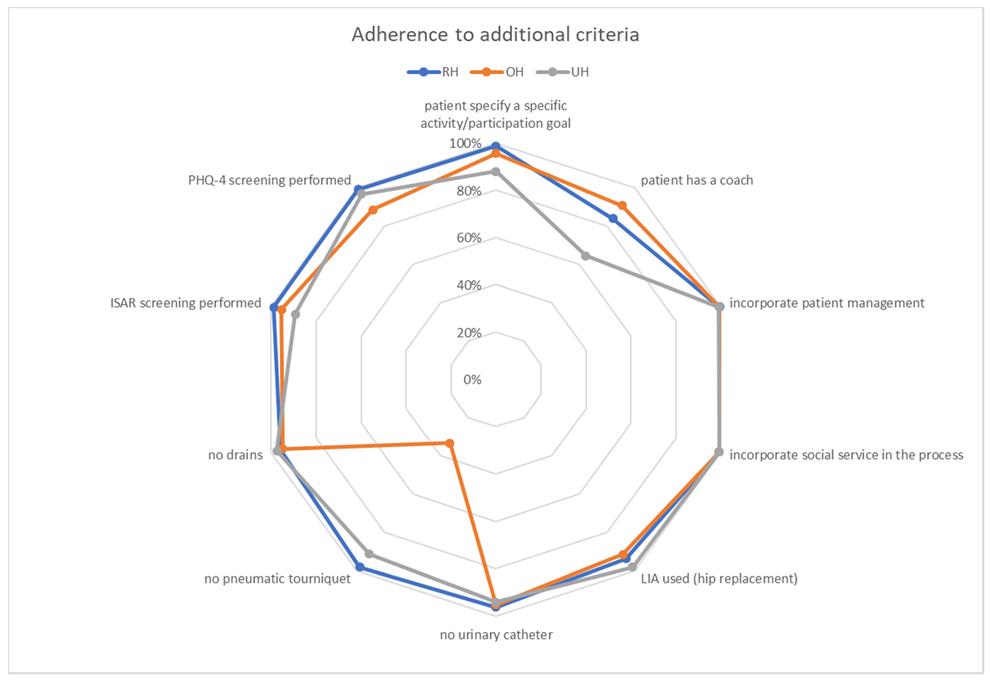

3.3. Additional PROMISE Criteria

For adherence to additional criteria overall and in the three different hospitals, see Table 3. These data also show implementation rates of >80% and missing data of <5% for almost all parameters at all centers. For the parameters ‘Patient has a coach’ (UH, 64.5%) and ‘No pneumatic tourniquet (TKA)’ (OH, 33.3%) the confirmation was <80%. In OH, 63% of knee arthroplasties were unicompartimental. Here, the tourniquet is used, since the operation takes place on the hanging leg and thus the overview is disturbed without tourniquet.

Table 3.

Overview of adherence to additional criteria overall and in the various hospitals. Implementation rates of less than 80% and missing data over 5% are highlighted in gray.

For the parameters ‘LIA used (THA)’ (RH), ‘No pneumatic tourniquet (TKA)’ (OH), ‘ISAR screening performed’ (UH) and ‘PHQ-4 screening performed’ (OH) the missings were >5%.

3.4. Participation in a Rehabilitation Program

Overall, 96.8% of patients participated for a mean of 23.1 days in a rehabilitation program. The results for the different hospitals varied between 92.8% and 98.5%. The remaining patients were transferred home (n = 34; 1.85%), to other specialized departments (n = 5; 0.3%) or to a nursing home (n = 3, 0.2%) without a rehabilitation program. Most patients participated in an inpatient rehabilitation program: 62.8–83.8% depending on the hospital. Of these patients, 31.9% were discharged home before the inpatient rehabilitation program, 68.1% were transferred directly from the hospital to the rehabilitation facility. In total, 29.8% of patients ran their rehabilitation program in a facility that was a collaborating partner of the PROMISE project. The data for the different hospitals to the different programs (inpatient and outpatient) in a PROMISE-cooperating partner institution differed markedly (0–50.2%; Table 4).

Table 4.

Overview of participation in a rehabilitation program overall and in the various hospitals. The data are differentiated according to outpatient/inpatient program and PROMISE cooperation partner/no PROMISE cooperation partner.

3.5. Use of Common Database

The hospitals added a total of 766,000 items and the rehabilitation facilities added another 48,000 to the common database. Both resulted in a comprehensive data set for each patient, which, beside the purpose of study evaluation, was available to the partners involved for project management, evaluation, and cross-sectoral communication purposes. The extent to which this information was used to optimize treatment could not be evaluated, since only the entry of data, but not its use, was documented.

4. Discussion

The UK Department of Health implemented an ERAS Partnership Programme [13] 2009–2011 to optimize treatment in THA and TKA. The report describes some positive effects, especially on LOS and patient experience. However, information about the program’s characteristics and statements on feasibility in different settings are missing [13]. This is a known problem in other large registry studies as well [14,15,16]. This is not negligible, as the degree of implementation of a program influences the results [5]. An optimized care process will only be effective for a health system if it can be transferred to different regions and service providers. Therefore, the funding announcement from the German Federal Joint Committee explicitly called for the transferability of the funded processes. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no publication to date that focuses on this issue for THA or TKA. In order to close this gap, the PROMISE Trial was conducted in three hospitals offering different levels of care and facilities in three different German regions. The subgroups in the different hospitals varied in size, but even the smallest group can be considered representative. The mean age, BMI and sex distribution were typical for a TKA/THA patient group [3,4]. Furthermore, the amount of registered comorbidities and results for ASA score are indicators that there was no preselection of particularly healthy patients, but that typical, perhaps even overall rather less healthy, persons were treated. With the PROMISE process already developed and implemented, the ERAS Society published its Consensus Statement on the Treatment of TKA and THA [8,9]. This contains the most evidence-based recommendations that also form the basic framework of the PROMISE process. The study can therefore also be seen as an evaluation of the ERAS recommendations in the German health care system. The PROMISE project verified implementation for 7/17 ERAS recommendations and the others are already firmly established standards without alternative in the included institutions. It should be noted, however, that in the PROMISE process the ERAS recommendations were expanded with further defined measures designed to reduce stress and expand activity. Overall, this has resulted in a particularly complex treatment process, which makes the task of implementation in different settings equally not self-evident.

In the scientific literature, references can be found for different patient groups demonstrating positive effects depending on 67–75% adherence to the ERAS protocol [5,17,18,19]. With this in mind, the adherence achieved in the PROMISE project for almost every single parameter, despite the completely different organizational circumstances at the various locations, were predominantly very high. Only two parameters (Anemia investigated, OH; No pneumatic tourniquet (TKA), OH) were implemented on a low level. However, this does not reflect reduced adherence to the PROMISE process. Instead, the process was sensibly adapted to local conditions (see results). The adaptation, however, cannot be represented by the choice of parameters. RH had implementation rates of >80% for all 19 parameters screened, OH and UH had three parameters with implementation rates of <80% (OH two because of process adaptation). Perhaps this demonstrates that the implementation of new, interdisciplinary processes is more complicated and error-prone in more complex facilities than in smaller ones. However, even in the most complex institution, the implementation was convincingly realized. An influence on feasibility due to the localization of the facilities in different German states is not apparent. All results indicate that the PROMISE process is feasible in very different settings and therefore transferability is given.

In the opinion of Henrik Kehlet ‘…more focus should be made on the different barriers to post-discharge functional recovery and the choice of (pre- and postoperative) rehabilitation’ [20]. This need is met by the fact that in Germany all patients capable of rehabilitation are entitled to participate in a rehabilitation program (§ 40 Sozialgesetzbuch V). This internationally specific situation was used as an opportunity for integration of rehabilitation into the optimized process. Since rehabilitation does not take place in hospitals but in special facilities, cooperation had to take place across the care sectors. This corresponds to a well-known demand for further development in the healthcare system [21]. In fact, the vast majority of all study participants participated in a rehabilitation program. However, since the German funding agencies decide on the facility in which the rehabilitation is carried out, only an unexpected small portion of the participants were treated in cooperative facilities. Thus, structural barriers have meant that the cross-sectoral integration of rehabilitation targeted in the PROMISE trial could only be partially achieved. Only when these obstacles are overcome can the integration of the rehabilitation sector be satisfactorily implemented and further evaluated. The willingness to cooperate across the sectors was high. This is also evident from extensive data that both hospitals and rehabilitation facilities entered into the common database. The fact that the proportion of rehabilitation facilities was smaller is due to the smaller number of participants there and the much smaller number of parameters to be entered. The extent to which the available information was used for optimizing therapy cannot be evaluated, since only the entry of data, but not its viewing or use, was documented. In practice, it could be that a common database is used more intensively for therapy, so long as the data set is concentrated on necessary information and is not overextended for study reasons.

As a further limitation of the study, it must be noted that, in terms of content, all cooperation partners were already convinced of the sense of process optimization before the study and were thus unusually committed to implementing the agreed key points of the process. In addition, they had a role in defining the program, so that it was also “their” program. Whether the implementation under standard conditions also succeeds comparably cannot be proven with it. Strictly, whether a program is feasible is not only decided by the implementation rate of cornerstones, but also by the clinical success. These results will be described with a 1-year follow-up in a subsequent publication.

A strength of this study is that it focuses on feasibility in a wide variety of settings for transferability of an optimized treatment program, an aspect that has been understudied. In addition, the study is prospective, multicentric, externally evaluated, very well documented, and was able to include a relevant number of participants. It takes into account that THA and TKA are done in very different settings in Germany.

5. Conclusions

In the PROMISE Trial, a complex newly defined optimized protocol for unselected patients receiving hip and knee endoprostheses is feasible in hospitals offering different levels of care and with different outpatient and inpatient rehabilitation facilities, in various German states, so that transferability to other centers and regions can be assumed. However, the cross-sectoral cooperation between hospitals and rehabilitation facilities intended in the project was only partially successful. Structural obstacles must be overcome here.

Author Contributions

All authors are members of the PROMISE working group and were involved in the administration of the project in many ways. P.D., U.B. and M.B. created the article concept, M.B. and B.B. were responsible for the data evaluation, U.B. is the main author and responsible for the draft, L.L., F.H., L.S., K.K., M.B., B.B., L.E., T.K. and P.D. participated in the discussion and participated actively in the study. All authors reviewed the entire text. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The trial was supported by a grant from the German Federal Joint Committee (01NVF16015).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The trial was approved by the ethics committees of Rhineland-Palatinate [837.533.17 (11367)], Baden-Wuerttemberg [B-F-2018-042], and Hesse [MC 84/2018].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

See https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00132-022-04247-4. Further data will be provided in subsequent publications.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- DGOU DGfOuUeV. Evidenz- und Konsensbasierte Indikationskriterien zur Hüfttotalendoprothese bei Coxarthrose (EKIT-Hüfte). Version 1.0; DGOU DGfOuUeV: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lützner, J.; Lange, T.; Schmitt, J.; Kopkow, C.; Aringer, M.; Böhle, E.; Bork, H.; Dreinhöfer, K.; Friederich, N.; Gravius, S.; et al. S2k-LL Indikation Knieendoprothese Langversion (AWMF Registernummer: 033-052); DGOOC: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen. Bundesauswertung zum Erfassungsjahr 2019. Hüftendoprothesenversorgung. Available online: Extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Fiqtig.org%2Fdownloads%2Fauswertung%2F2019%2Fhep%2FQSKH_HEP_2019_BUAW_V02_2020-07-14.pdf&clen=1730760&chunk=true (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen. Bundesauswertung zum Erfassungsjahr 2019. Knieendoprothesenversorgung. Available online: Extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/viewer.html?pdfurl=https%3A%2F%2Fiqtig.org%2Fdownloads%2Fauswertung%2F2019%2Fkep%2FQSKH_KEP_2019_BUAW_V02_2020-07-14.pdf&clen=1360691&chunk=true (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Ripollés-Melchor, J.; Abad-Motos, A.; Díez-Remesal, Y.; Aseguinolaza-Pagola, M.; Padin-Barreiro, L.; Sánchez-Martín, R.; Logroño-Egea, M.; Catalá-Bauset, J.C.; García-Orallo, S.; Bisbe, E.; et al. Association between Use of Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Protocol and Postoperative Complications in Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the Postoperative Outcomes within Enhanced Recovery after Surgery Protocol in Elective Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Study (POWER2). JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, e196024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, U.; Langanki, L.; Heid, F.; Spielberger, J.; Schollenberger, L.; Kronfeld, K.; Büttner, M.; Büchler, B.; Goldhofer, M.; Eckhard, L.; et al. The PROMISE study protocol: A multicenter prospective study of process optimization with interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral care for German patients receiving hip and knee endoprostheses. Acta Orthop. 2020, 92, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DRV. Deutsche Rentenversicherung. Reha Therapiestandards Hüft-und Knie-TEP; DRV: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright, T.W.; Gill, M.; A McDonald, D.; Middleton, R.G.; Reed, M.; Sahota, O.; Yates, P.; Ljungqvist, O. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2019, 91, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wainwright, T.W.; Gill, M.; A McDonald, D.; Middleton, R.G.; Reed, M.; Sahota, O.; Yates, P.; Ljungqvist, O. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2020, 91, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McCusker, J.; Bellavance, F.; Cardin, S.; Trepanier, S.; Verdon, J.; Ardman, O. Detection of Older People at Increased Risk of Adverse Health Outcomes after an Emergency Visit: The ISAR Screening Tool. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1999, 47, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. An Ultra-Brief Screening Scale for Anxiety and Depression: The PHQ-4. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 50, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, J.; Lange, T.; Günther, K.-P.; Kopkow, C.; Rataj, E.; Apfelbacher, C.; Aringer, M.; Böhle, E.; Bork, H.; Dreinhöfer, K.; et al. Indication Criteria for Total Knee Arthroplasty in Patients with Osteoarthritis—A Multi-perspective Consensus Study. Z. Orthop. Unfall. 2017, 155, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NHS. Enhanced Recovery Partnership Programme Report—March 2011. Enhanced Recovery Partnership Programme—GOV.UK. 2011. Available online: www.gov.uk (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Grosso, M.J.; Neuwirth, A.L.; Boddapati, V.; Shah, R.P.; Cooper, H.J.; Geller, J.A. Decreasing Length of Hospital Stay and Postoperative Complications after Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Decade Analysis from 2006 to 2016. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 34, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarpong, N.O.; Boddapati, V.; Herndon, C.L.; Shah, R.P.; Cooper, H.J.; Geller, J.A. Trends in Length of Stay and 30-Day Complications after Total Knee Arthroplasty: An Analysis from 2006 to 2016. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 34, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, T.D.; Dvorani, E.; Saskin, R.; Khoshbin, A.; Atrey, A.; Ward, S.E. Temporal Trends and Predictors of Thirty-Day Readmissions and Emergency Department Visits Following Total Knee Arthroplasty in Ontario between 2003 and 2016. J. Arthroplast. 2019, 35, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gustafsson, U.O.; Oppelstrup, H.; Thorell, A.; Nygren, J.; Ljungqvist, O. Adherence to the ERAS protocol is Associated with 5-Year Survival after Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Retrospective Cohort Study. World J. Surg. 2016, 40, 1741–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrick, L.; Mayson, K.; Hong, T.; Warnock, G. Enhanced recovery after surgery in colorectal surgery: Impact of protocol adherence on patient outcomes. J. Clin. Anesth. 2018, 55, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, I.H.; Pappou, E.P.; Smith, J.J.; Widmar, M.; Nash, G.M.; Weiser, M.R.; Paty, P.B.; Guillem, J.G.; Afonso, A.; Garcia-Aguilar, J. Monitoring an Ongoing Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Program: Adherence Improves Clinical Outcomes in a Comparison of Three Thousand Colorectal Cases. Clin. Surg. 2020, 5, 2909. [Google Scholar]

- Kehlet, H. Enhanced postoperative recovery: Good from afar, but far from good? Anaesthesia 2020, 75, e54–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IGES-Institut. Infrastruktur und Gesundheit. Weißbuch Gelenkersatz—Versorgungssituation bei endoprothetischen Hüft- und Knieeingriffen in Deutschland; IGES-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).