Investigating the Effect of Consumers’ Knowledge on Their Acceptance of Functional Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

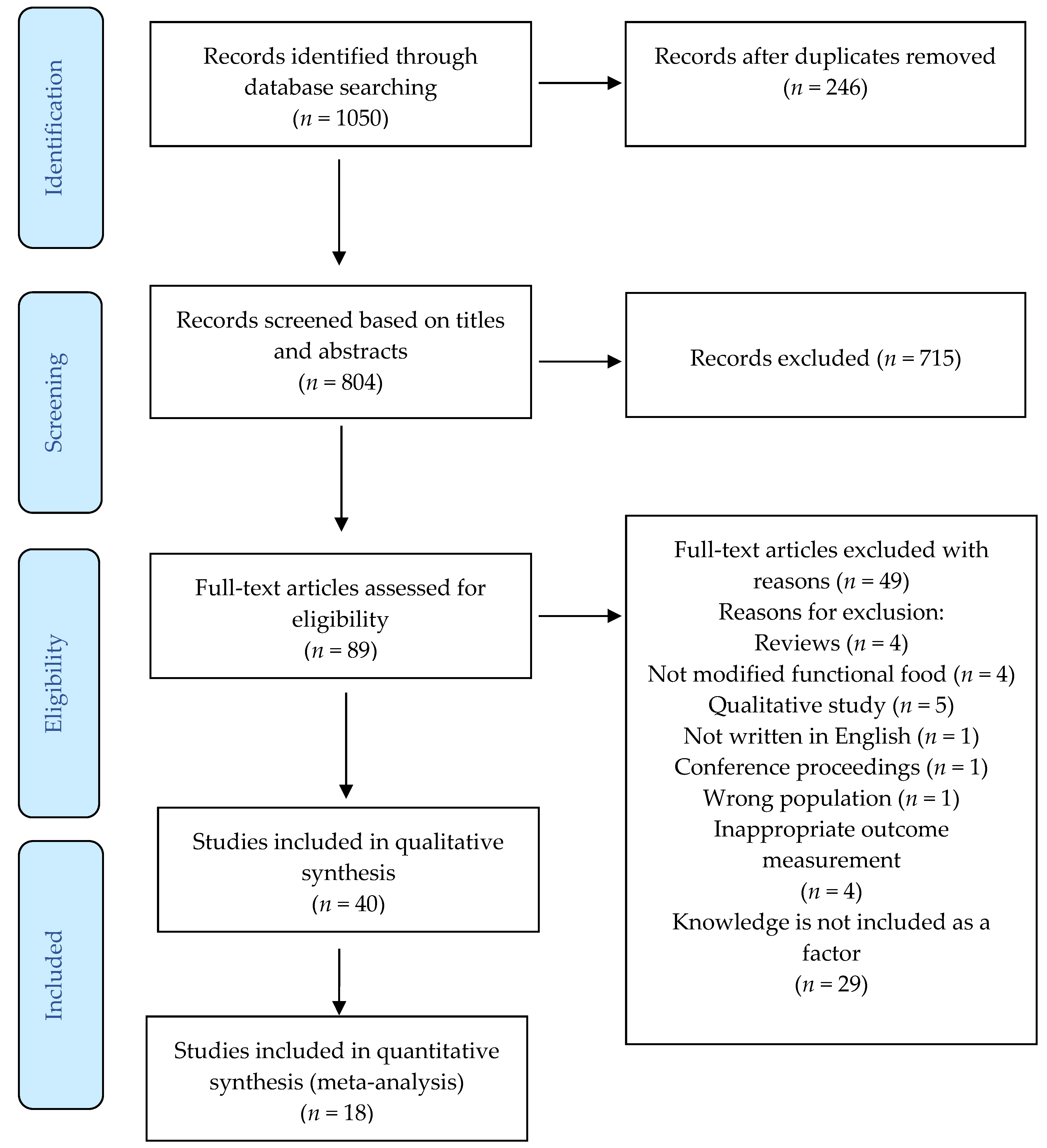

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Database and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Synthesis

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.2. Qualitative Systematic Review Findings

3.2.1. Consumers’ Knowledge of the Concept of Functional Foods

3.2.2. Consumers’ Knowledge about Nutrition of Functional Foods

3.2.3. Consumers’ Knowledge of Specific Functional Foods

3.2.4. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Knowledge of Functional Foods

3.2.5. Relationship between Consumers’ Knowledge and Their Acceptance of Functional Foods

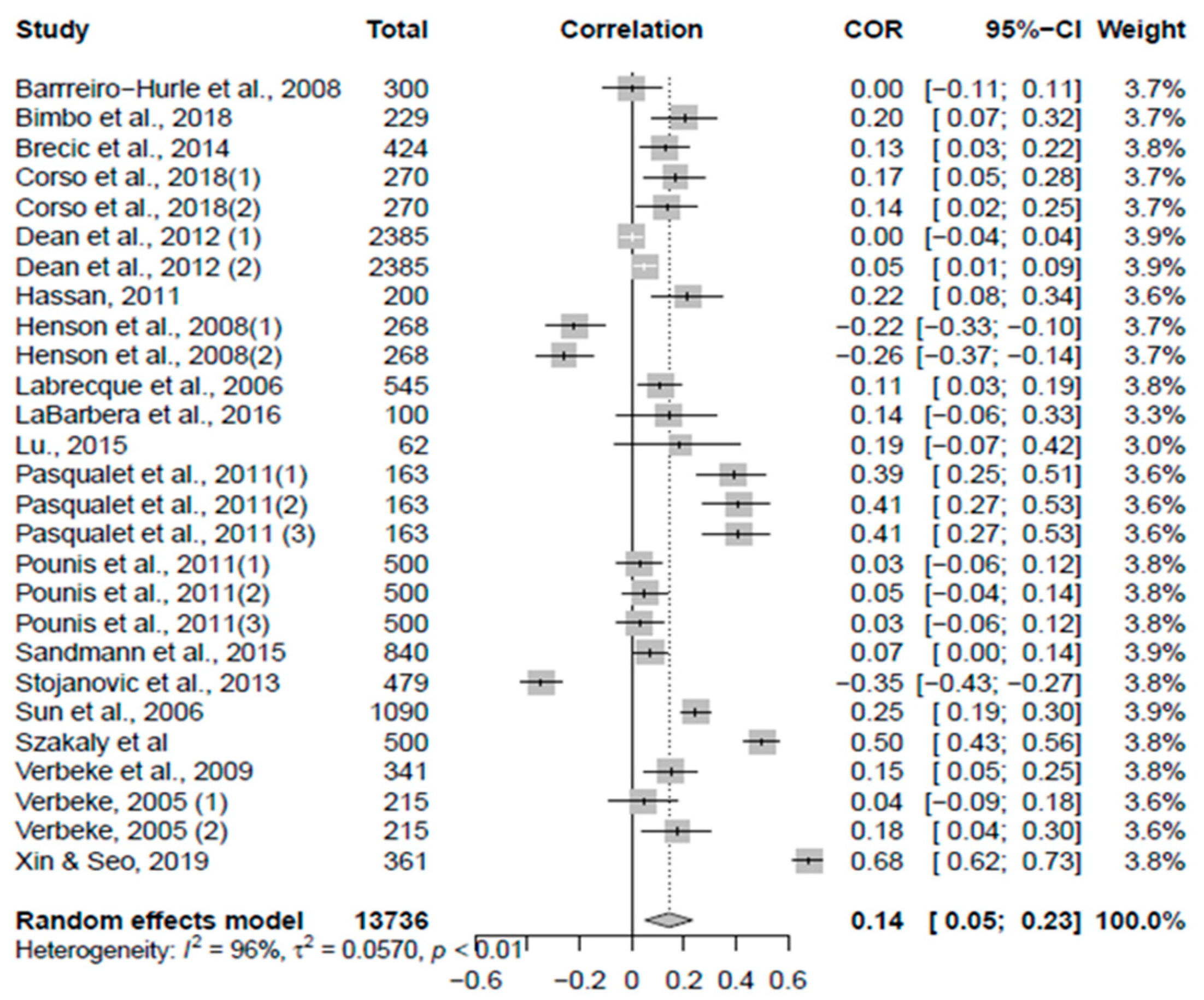

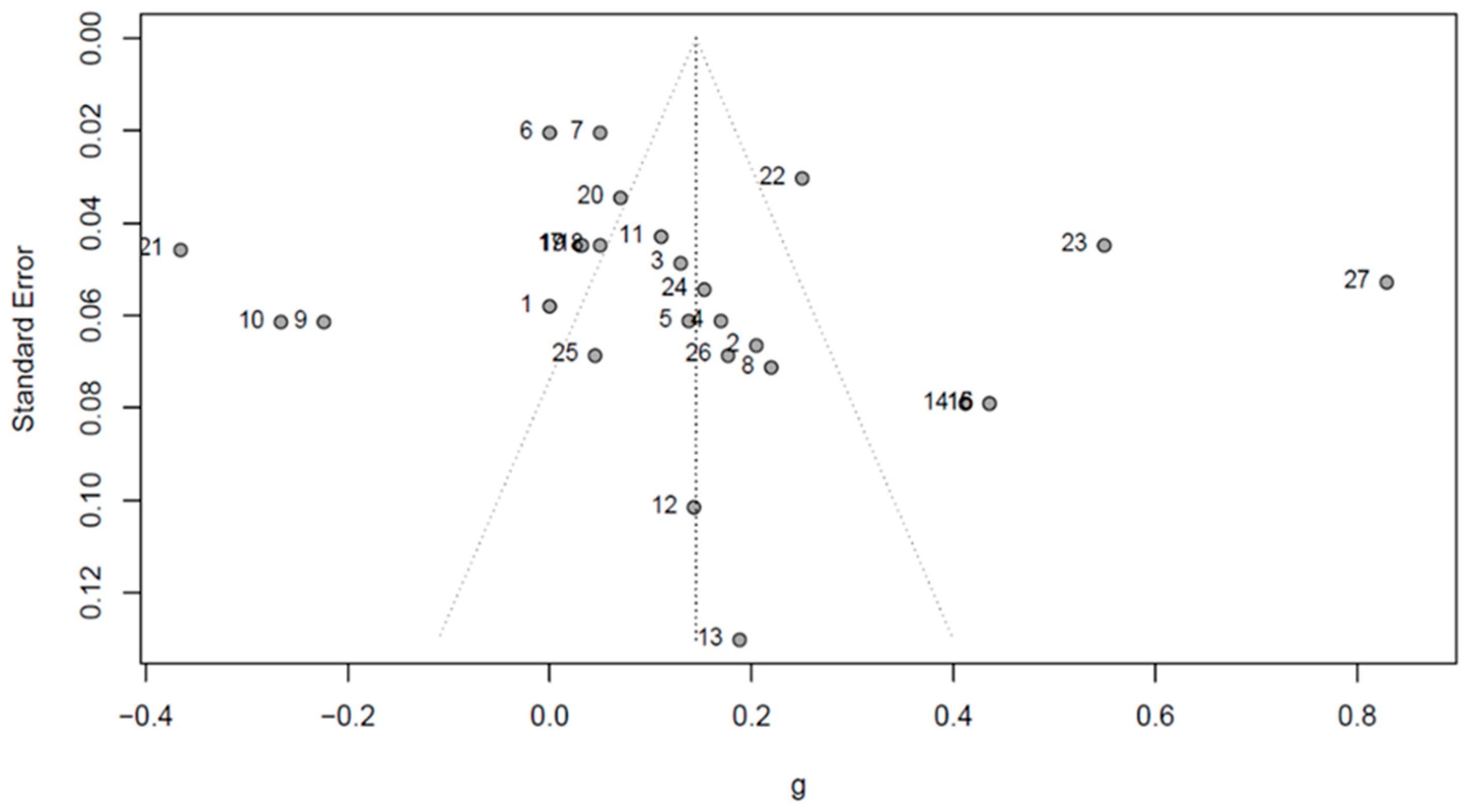

3.3. Meta-Analysis Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Country | Functional Foods Type | Study Design | Knowledge Type | Outcome Variable | Correlation | Sample Size | Age of Participants | Risk of Bias | Main Findings about Knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arenna et al., 2019 [56] | Canada | Enhanced carnosine in pork | Surveyed-based choice experiment | Nutrition knowledge | Willingness to pay | Data was unusable | 992 | 18+; Average age = 52.6 | Low | Participants’ average nutrition knowledge score was 15.8 (ranging from 5–25); Participants’ level of nutrition knowledge is significantly, positively associated with their willingness to pay for functional foods. |

| Ares et al., 2008 [66] | Uruguay (South America) | 16 functional foods concepts | Survey | Nutrition knowledge (nutrient content; antioxidants; connection between diet and diseases) | Willingness to try | Data was unusable | 104 | 18–81; Average age = 34.3 | Low | Nutrition knowledge significantly affected participants’ willingness to try functional foods; Nutrition knowledge significantly affected participants’ perceived healthiness of functional foods; Participants who had a low level of nutrition knowledge were not interested in consuming functional foods; Participants with a high level of nutrition knowledge were interested in healthy foods enriched with fiber or antioxidants. |

| Barreiro-Hurlé et al., 2008 [30] | Spain | Resveratrol-enriched red wine | Surveyed-based choice experiment | Nutrition knowledge | Willingness to pay | r = −0.01 | 300 | Average age = 46.5 | Low | 45% of participants had nutrition knowledge regarding fat and cholesterol content and daily caloric recommendations; Participants who know the relationship between health and diet are more likely to buy functional wine. |

| Bimbo et al., 2018 [43] | Italian | Functional yogurts | Post-purchased survey | Knowledge about leading functional yogurt brands | The numbers of functional yogurt packages purchased | r = 0.2019 | 229 | 18–60 | Low | Participants with more knowledge of leading functional yogurt brands purchased a higher number of functional yogurt packages; Regardless of participants’ level of knowledge of leading functional yogurt brands, those who did not like their own bodies were less likely to purchase functional yogurt packages. |

| Brečić et al., 2014 [17] | Croatia | The concept of functional foods | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Functional foods consumption frequency | r = 0.129 | 424 | 18+; Average age = 47.6 | Low | 6% of participants reported themselves as “fully informed” about functional foods; 21% reported themselves as “very well informed” about functional foods; A significant, positive relationship existed between participants’ knowledge of functional foods and their consumption of functional foods. |

| Chammas et al., 2019 [52] | Lebanon | Prebiotic yogurt; Protein bars; Protein shakes; Cereal bars | Survey | Knowledge of functional foods and functional ingredients | Functional foods acceptance | Data was unusable | 251 | 34.5 ± 12.1 | Low | 40.6% of participants were knowledgeable about functional foods; 32% of participants were knowledgeable about functional ingredients; Participants between the ages of 18 and 29 had a higher knowledge level of functional foods; Single participants had a higher knowledge level of functional foods; Participants who went to the gym had a higher knowledge of functional foods. |

| Clark et al., 2019 [48] | England | Vitamin D fortified foods | Mixed methods (focus groups and survey) | Knowledge of vitamin D | Perceptions of fortified foods | Data was unusable | 109 | 16+ | Low | Participants had basic knowledge of vitamin D; Participants lacked knowledge about the health benefits of vitamin D sufficiency. |

| Corso et al., 2018 [21] | Brazil | Coffee enriched with antioxidants | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Functional foods acceptance | r = 0.168 (“if they taste good”); r = 0.137 (“if they taste worse than their conventional counterpart foods”) (p. 5) | 270 | Average age = 39.1 | Low | Participants’ knowledge of functional foods was significantly, positively associated with their acceptance of functional coffee; 49.6% of participants knew the benefits of coffee ingestion; 60.7% of participants knew the benefits of antioxidants ingestion; 5.6% of participants knew the benefits of consuming soluble coffee. |

| Cukelj et al., 2016 [7] | Croatia | Flaxseed-enriched cookies | Online survey | Nutrition knowledge about lignans and omega-3 fatty acids (ingredients) | Purchase interests | Data was unusable | 1035 | 15–65 | Moderate | Female participants had a higher level of nutrition knowledge compared to male participants; Participants’ age was not associated with their knowledge level; Female participants’ educational level was significantly, positively associated with their level of nutrition knowledge; Participants with a higher level of nutrition knowledge consumed more functional cookies compared to those with a lower level of nutrition knowledge. |

| Dean et al., 2012 [34] | Finland; the UK; Germany; Italy | Bread, cake, and cereal-containing yogurt + benefit claim, risk reduction claim, and nutrition claim | Paper and pencil survey | Subjective knowledge | Likelihood to buy | r = 0.05 (nutrition claim); r = 0.04 (risk reduction claim) | 2385 | 35–95; Average age = 52.1 | Low | Participants’ subjective knowledge was a significant predictor of their likelihood to buy functional foods with a nutrition claim; Participants’ subjective knowledge did not increase their likelihood to buy functional foods with risk reduction claims. |

| Di Talia et al., 2018 [49] | Italy; Germany | The term functional foods | Survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Attitudes toward functional foods | Data was unusable | 230 | Data was not available | Moderate | Participants’ level of knowledge of functional foods was low; 68% of participants were informed consumers who had knowledge of functional foods. |

| Grochowska-Niedworok et al., 2017 [53] | Poland | The concept of functional foods | Survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Functional foods consumption | Data was unusable | 300 | Data was not available | Moderate | Participants’ level of knowledge about functional foods was low; 83.3% of participants did not know the amount of functional foods available on the market; 43.1% of healthy participants and 53.97% of participants with diseases had no knowledge regarding their consumption of functional foods. |

| Hasnah 2011 [35] | Malaysia | The concept of functional foods | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Functional foods consumption | r = 0.216 | 200 | 18–54 | Low | Participants’ knowledge of functional foods positively influenced their functional foods consumption; Participants were knowledgeable about functional foods. |

| Hayat et al., 2010 [58] | Pakistan | Nutrient enriched designer eggs | Survey | Knowledge about designer eggs (type of functional food) | Perception and willingness to buy | Data was unusable | 262 | 18+; Median age = 37 | Moderate | 14.2% of participants knew of nutrient-enriched designer eggs, and 85.7% did not; Male participants had slightly more knowledge than female participants; Participants’ marital status and occupation were significantly associated with their level of knowledge. |

| Henson et al., 2008 [22] | Canada | Tomato juice and a snack bar containing lycopene | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of medicine, nutrition, or health care | Purchase intention | r = −0.22 (tomato juice); r = −0.26 (snack bar) | 268 | 18+ | Low | Participants’ knowledge of medicine, nutrition, or health care was significant, and negatively associated with their intent to buy functional foods. |

| Herath et al., 2008 [83] | Canada | Food/beverage containing desirable nutritional qualities (fiber, antioxidants, essential fatty acids) | Survey | Knowledge about food-health linkages | Functional food receptiveness | Data was unusable | 1753 | 18+ | Low | Participants who had a higher level of knowledge of age-related diseases had greater receptivity toward functional foods. |

| Hung et al., 2016 [59] | Belgium; Netherlands; Italy; Germany | Meat products processed with natural compounds and a reduced level of nitrite | Survey | Objective knowledge about the purpose of adding nitrite to meat | Purchase intention | Data was unusable | 2057 | 18–75; Average age = 45.5 | Low | 54.9% of participants had no knowledge about nitrite added to processed meats product. |

| Kolodinsky et al., 2008 [50] | Canada; United States; France | Eggs with omega-3; milk with calcium; orange juice with calcium | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Purchase intention | Data was unusable | 811 | 22.4 ± 3.3 | Low | 33.1% of participants had good knowledge of functional foods; 28.1% had partial knowledge; 38.3% had no knowledge; Participants from the United States had greater knowledge about functional foods than French and Canadian participants. |

| Labrecque et al., 2006 [36] | Canada; United States; France | Milk with Omega-3; egg with Omega-3 | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of the term ‘functional foods’ | Functional food acceptance | r = 0.11 | 545 | 18–25 | Low | 56.9% of American participants, 45.8% of Canadian participants, and 10.6% of French participants knew the term functional foods; Participants’ level of functional foods knowledge was significantly, positively associated with their acceptance of functional foods. |

| La Barbera et al., 2016 [5] | Italian | Crushed tomatoes enriched with lycopene | Surveyed-based experimental auction | Subjective knowledge about lycopene | Willingness to pay | r = 0.1423 | 100 | Average age = 23.06 | Low | Participants’ level of knowledge about lycopene was significantly, positively associated with their willingness to pay a higher premium price for functional foods. |

| Lu., 2015 [20] | Canada | 30 hypothetical functional foods | Surveyed-based experimental auction | Nutrition knowledge | Purchase intention | r = 0.1862 | 62 | 18–55 | Low | Participants’ level of nutrition knowledge was significantly, positively associated with their intent to purchase functional foods; Participants’ level of nutrition knowledge significantly moderated the relationship between their perceived carrier-ingredient fit of a functional food and their purchase intention. |

| Nguyen, 2020 [84] | Vietnam | The term functional foods | Survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Functional food acceptance | Data was unusable | 260 | 20+ | Low | Participants’ level of functional foods knowledge was significant, and positively associated with their acceptance of functional foods. |

| O’Connor & Venter, 2012 [54] | South Africa | Ten bioactive food ingredients (functional ingredients) | Survey | Health and wellness knowledge; Nutrition knowledge | Perceived interest | Data was unusable | 139 | 25–65 | Low | 22.3% of participants perceived their level of health and wellness knowledge to be well informed; 66.9% of participants perceived their level of health and wellness knowledge to be moderately informed; 17.3% of participants perceived their level of nutrition knowledge to be well informed; 65.5% of participants perceived their level of nutrition knowledge to be moderately informed; Participants who had higher knowledge of Omega-3 fatty acids, probiotics, and soy protein tended to adopt functional foods. |

| Di Pasquale et al., 2011 [37] | Italy | Milk, butter, and yogurt fortified with conjugated linoleic acid | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of the relationship between diet and health; Knowledge of functional foods | Willingness to pay | r = 0.39 (milk); r = 0.41; (yogurt); r = 0.41 (butter) | 163 | 20–80; Average age = 43 | Low | Participants’ knowledge of functional foods significantly influenced their willingness to pay for functional foods; 29% of participants had no knowledge of functional foods or the relationship between diet and health; 29% of participants knew the major functional foods product categories and some knowledge of the relationship between diet and health; 28% of participants had some knowledge of functional foods that was greatly influenced by advertising and no knowledge of the relationship between diet and health; 14% of participants knew of (were familiar with) functional foods and knew (good awareness) of the relationship between diet and health. |

| Pounis et al., 2011 [38] | Greece | Iron-fortified foods | Survey | Overall nutrition knowledge; general nutrition knowledge; iron nutrition knowledge | Iron fortified foods perception and consumption | r = 0.03 (overall nutrition); r = 0.05 (general nutrition); r = 0.032 (iron deficiency) | 500 | 30 ± 12 | Low | Increasing participants’ overall nutrition knowledge improved their perception of iron-fortified foods; Participants’ overall nutrition knowledge, general nutrition knowledge, and iron nutrition knowledge were significantly, positively associated with their consumption of iron-fortified foods. |

| Sääksjärvi et al., 2009 [85] | Finland | The term functional foods | Survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Purchase behavior | Data was unusable | 409 | 18+ | Low | Participants’ attitudes toward health mediated the effect between their knowledge of functional foods and purchase behavior; Female participants had more knowledge of functional foods than male participants; Participants aged 55 to 65 had the most knowledge of functional foods; Participants’ income was significantly, positively associated with their knowledge of functional foods; University-educated participants had more knowledge of functional foods than high school-educated participants. |

| Sandmann et al., 2015 [8] | Germany | Vitamin D-fortified foods (i.e., juice, cereals, butter, milk, yogurt) | Online survey | General knowledge of vitamin D | Acceptance of vitamin D-fortified foods | r = 0.07 | 840 | 19+ | Low | Participants’ general knowledge about vitamin D was not significantly related to their acceptance of vitamin D-fortified foods; Most participants lacked general knowledge about vitamin D; 22% of participants reported that their vitamin D-related knowledge was good. |

| Schnettler et al., 2015 [86] | Chile | Functional foods with 18 health benefits | Survey | Knowledge of functional food | Willingness to buy | Data was unusable | 400 | <35 (34.5%); 35–54 (42.0%); 55 + (23.5%) | Low | Participants’ level of functional foods knowledge positively influenced their willingness to buy. |

| Schnettler et al., 2016 [51] | Chile | Data was not available | Survey | Knowledge of functional food | Attitude | Data was unusable | 372 | Average age = 20.4 | Low | Most participants (83.6%) had no prior knowledge of functional foods. |

| Sparke et al., 2009 [60] | Germany; Poland; Spain; United Kingdom | Orange juice enriched with functional ingredients recombined with different health claims | Survey | Knowledge of functional food | Functional food purchase frequency | Data was unusable | 590 | Data was not available | Low | There was no correlation between participants’ knowledge of functional foods and their purchase frequency. |

| Spiroski et al., 2013 [55] | Republic of Macedonia | Data was not available | Survey | Nutrition knowledge | Attitude | Data was unusable | 518 | 18+ | Low | Participants’ nutrition knowledge was at a moderate level. |

| Stojanovic et al., 2013 [39] | Montenegro | Products with health claims (e.g., the benefits of high calcium) | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of foods with health claims | Consumption frequency | r = −0.35 | 479 | 18+ | Low | 52% of participants were moderately informed about foods with health claims; 1.9% of participants were fully informed; 8.6% of participants were not informed at all; Participants’ level of knowledge of foods with health claims is a predictor of their functional food consumption. |

| Sun et al., 2006 [31] | China | Iron-fortified soy sauce | Survey | Knowledge of iron-fortified soy sauce | Purchase intention | r = 0.245 | 1090 | Average age = 37.33 | Low | Participants had limited knowledge of iron-fortified soy sauce; 3% of participants from rural areas and 15% of participants from urban areas had heard of iron-fortified soy sauce; Participants’ knowledge of iron-fortified soy sauce was significant, and positively associated with their intention to purchase. |

| Szakály et al., 2019 [40] | Hungary | Dairy-based probiotic products (e.g., yogurt, cheese, muesli) | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Willingness to pay | r = 0.5 | 500 | 18–69 | Low | Participants’ subjective knowledge of functional foods was significant, and positively associated with their purchase patterns of functional dairy products. |

| Verbeke et al., 2009 [42] | Belgium | Calcium-enriched fruit juice; Omega-3 enriched spread; fiber-enriched cereal | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Intention to buy product | r = 0.15 | 341 | Average age = 37.4 | Low | There was no significant relationship between participants’ knowledge of functional foods and their acceptance. |

| Verbeke, 2005 [18] | Belgium | The concept of functional foods | Self-administered survey | Knowledge of functional foods | Functional foods acceptance | Data was unusable | 215 | Average age = 39.1 | Low | There was no significant relationship between participants’ knowledge of functional foods and their acceptance. |

| Verneau et al., 2019 [87] | Italy | Canned crushed tomatoes enriched with lycopene | Experimental auction | Knowledge about lycopene (ingredients) | Willingness to pay | Data was unusable | 100 | Average age = 23.88 | Low | Participants with low knowledge of lycopene increased their willingness to pay after receiving information about the product. |

| Wansink et al., 2005 [16] | Canada; United States | The term functional foods | Mail survey | Knowledge of soy (attribute-related knowledge; consumption consequence-related knowledge) | Functional foods consumption | Data was unusable | 606 | Data was not available | Low | 74.4% of participants had attribute-related knowledge, consumption consequence-related knowledge, or both; participants with attribute-related knowledge and consequence-related knowledge were more likely to consume soy products. |

| Xin & Seo, 2019 [32] | China | Korean functional foods (e.g., red ginseng, ginseng, vitamin, tonic, calcium, fish oil) | Online survey | Subjective knowledge of Korean functional foods | Purchase intention | r = 0.68 | 361 | 20–60 | Low | Participants’ subjective knowledge about Korean functional foods was significant, and positively associated with their purchase intention. |

| Yalçın et al., 2020 [57] | Turkey | Foods with dietary fibers | Survey | Knowledge of dietary fibers and foods; knowledge of dietary fibers and health effects | Attitude | Data was unusable | 293 | 18–71; Average age = 34.8 | Low | 65.7% of participants had a high level of knowledge about dietary fibers and foods; 59.1% of participants had a high level of knowledge about dietary fibers and health effects. |

References

- Plasek, B.; Lakner, Z.; Kasza, G.; Temesi, Á. Consumer evaluation of the role of functional food products in disease prevention and the characteristics of target groups. Nutrients 2020, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Chronic Disease Overview. 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm (accessed on 1 September 2021).

- Stover, P.J.; Garza, C.; Durga, J.; Field, M.S. Emerging concepts in nutrient needs. J. Nutr. 2020, 150 (Suppl. S1), 2593S–2601S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasler, C.M. Functional foods: Benefits, concerns and challenges—A position paper from the American Council on Science and Health. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 3772–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- La Barbera, F.; Amato, M.; Sannino, G. Understanding consumers’ intention and behavior towards functionalized food. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diplock, A.T.; Aggett, P.J.; Ashwell, M.; Bornet, F.; Fern, E.B.; Roberfroid, M.B. Scientific concepts in functional foods in Europe: Consensus document. Br. J. Nutr. 1999, 81, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukelj, N.; Putnik, P.; Novotni, D.; Ajredini, S.; Voŭcko, B.; Duška, C. Market potential of lignans and omega-3 functional cookies. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2420–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandmann, A.; Brown, J.; Mau, G.; Saur, M.; Amling, M.; Barvencik, F. Acceptance of vitamin D-fortified products in Germany—A representative consumer survey. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Barba, F.J.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Cruz, A.G.; Putnik, P. Functional foods: Product development, technological trends, efficacy testing, and safety. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 11, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Consumer acceptance of novel food technologies. Nat. Food 2020, 1, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, J.; Parmenter, K.; Waller, J. Nutrition knowledge and food intake. Appetite 2000, 111, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topolska, K.; Florkiewicz, A.; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, A. Functional food—Consumer motivations and expectations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annunziata, A.; Vecchio, R. Functional foods development in the European market: A consumer perspective. J. Funct. Food 2011, 3, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; West, G.E.; Wang, C. Consumer attitudes and acceptance of CLA-enriched dairy products. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 54, 663–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urala, N.; Lähteenmäki, L. Attitudes behind consumers’ willingness to use functional foods. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wansink, B.; Westgren, R.E.; Cheney, M.M. Hierarchy of nutritional knowledge that relates to the consumption of a functional food. Nutrition 2005, 21, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brečić, R.; Gorton, M.; Barjolle, D. Understanding variations in the consumption of functional foods–evidence from Croatia. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 662–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W. Consumer acceptance of functional foods: Socio-demographic, cognitive and attitudinal determinants. Food Qual. Prefer. 2005, 16, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiné, R.P.F.; Florença, S.G.; Barroca, M.J.; Anjos, O. The link between the consumer and the innovations in food product development. Foods 2020, 9, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. The effect of perceived carrier-ingredient fit on purchase intention of functional food moderated by nutrition knowledge and health claim. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1872–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, M.P.; Kalschne, D.L.; Benassi, M.D.T. Consumer’s attitude regarding soluble coffee enriched with antioxidants. Beverages 2018, 4, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henson, S.; Masakure, O.; Cranfield, J. The propensity for consumers to offset health risks through the use of functional foods and nutraceuticals: The case of lycopene. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, E.; Kang, H. Introduction to systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J. Anesth. 2018, 71, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Impellizzeri, F.M.; Bizzini, M. Systematic review and meta-analysis: A primer. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 7, 493–503. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23091781/ (accessed on 12 April 2022). [PubMed]

- Paul, M.; Leibovici, L. Systematic review or meta-analysis? Their place in the evidence hierarchy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sears, K.; Sfetcu, R.; Currie, M.; Qureshi, R.; Mattis, P.; Lisy, K.; et al. Systematic Reviews of Etiology and Risk. In Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2017; Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc. Probl. 1965, 12, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; Colombo, S.; Cantos-Villar, E. Is there a market for functional wines? Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for resveratrol-enriched red wine. Food Qual. Prefer. 2008, 19, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Sun, J. Predicting iron-fortified soy sauce consumption Intention: Application of the theory of planned behavior and health belief model. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2006, 38, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Seo, S.S. The role of consumer ethnocentrism, country image, and subjective knowledge in predicting intention to purchase imported functional foods. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Brown, S.P. On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dean, M.; Lampila, P.; Shepherd, R.; Arvola, A.; Saba, A.; Vassallo, M.; Claupein, E.; Winkelmann, M.; Lähteenmäki, L. Perceived relevance and foods with health-related claims. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 24, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnah Hassan, S. Consumption of functional food model for Malay Muslims in Malaysia. J. Islam. Mark. 2011, 2, 104–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, J.; Doyon, M.; Bellavance, F.; Kolodinsky, J. Acceptance of functional foods: A comparison of French, American, and French Canadian consumers. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 54, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasquale, J.; Adinolfi, F.; Capitanio, F. Analysis of consumer attitudes and consumers’ willingness to pay for functional foods. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounis, G.D.; Makri, S.; Gougias, L.; Makris, H.; Papakonstantinou, M.; Panagiotakos, D.B.; Kapsokefalou, M. Consumer perception and use of iron fortified foods is associated with their knowledge and understanding of nutritional issues. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, Z.; Filipovic, J.; Mugosa, B. Consumer acceptance of functional foods in Montenegro. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2013, 9, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Szakály, Z.; Kovács, S.; Pető, K.; Huszka, P.; Kiss, M. A modified model of the willingness to pay for functional foods. Appetite 2019, 138, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, M.; Hedges, L.; Higgins, J.; Rothstein, H. Introduction to Meta-Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, W.; Scholderer, J.; Lähteenmäki, L. Consumer appeal of nutrition and health claims in three existing product concepts. Appetite 2009, 52, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimbo, F.; Bonanno, A.; Van Trijp, H.; Viscecchia, R. Body image dissatisfaction and health-enhancing food choices: A pilot study from a sample of Italian yogurt consumers. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2778–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A.P.; Gillett, R. How to do a meta-analysis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2010, 63, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, D.S. From pre-registration to publication: A non-technical primer for conducting a meta-analysis to synthesize correlational data. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ioannidis, J.P.; Patsopoulos, N.A.; Evangelou, E. Uncertainty in heterogeneity estimates in meta-analyses. BMJ 2007, 335, 914–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clark, B.; Hill, T.; Hubbard, C. Consumers’ perception of vitamin D and fortified foods. Br. Food J. 2019, 121, 2205–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Talia, E.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Consumer acceptance and consumption of functional foods. An attempt of comparison between Italy and Germany. Qual. Access Success 2018, 19, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodinsky, J.; Labrecque, J.; Doyon, M.; Reynolds, T.; Oble, F.; Bellavance, F.; Marquis, M. Sex and cultural differences in the acceptance of functional foods: A comparison of American, Canadian, and French college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2008, 57, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Adasme-Berríos, C.; Grunert, K.G.; Márquez, M.P.; Lobos, G.; Salinas-Onate, N.; Orellana, L.; Sepulveda, J. The relation between attitudes toward functional foods and satisfaction with food-related life. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 2234–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chammas, R.; El-Hayek, J.; Fatayri, M.; Makdissi, R.; Bou-Mitri, C. Consumer knowledge and attitudes toward functional foods in Lebanon. Nutr. Food Sci. 2019, 49, 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochowska-Niedworok, E.; Brukało, K.; Kardas, M. Consumer choice determinants in context of functional food. Int. J. Nutr. Food Eng. 2017, 11, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.; Venter, I. Awareness, knowledge, understanding and readiness to adopt bioactive food ingredients as part of functional food consumption by health-conscious consumers of the City of Cape Town. J. Consum. Sci. 2012, 40, 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Spiroski, I.; Gjorgjev, D.; Milosevic, J.; Kendrovski, V.; Naunova-Spiroska, D.; Barjolle, D. Functional Foods in Macedonia: Consumers Perspective and Public Health Policy. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 1, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arenna; Goddard, E.; Muringai, V. Consumer purchase intentions for pork with enhanced carnosine-A functional food. Can. J. Agr. Econ. Rev. Can. Agroecon. 2019, 67, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçln, E.; Kösemeci, C.; Correia, P.; Karademir, E.; Ferreira, M.; Florenca, S.G.; Guiné, R.P.F. Evaluation of consumer habits and knowledge about dietary fibre and fibre-rich products in Turkish population. Open Agric. 2020, 5, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, Z.; Pasha, T.N.; Khattak, F.M.; Jabbar, M.A.; Nasir, Z.; Samiullah, S. Consumer’s perception and willingness to buy nutrient enriched designer eggs in Pakistan. Archiv. Fur Geflugelkunde 2010, 74, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, Y.; de Kok, T.M.; Verbeke, W. Consumer attitude and purchase intention towards processed meat products with natural compounds and a reduced level of nitrite. Meat Sci. 2016, 121, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparke, K.; Menrad, K. Cross-European and Functional Food related consumer segmentation for new product development. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2009, 15, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Funder, D.C.; Ozer, D.J. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 2, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G.E.; Szodorai, E.T. Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, M.N.; Stratton, L.M.; Sheeshka, J.; Duncan, A.M. Functional food awareness and perceptions in relation to information sources in older adults. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, M.; Venter, I. Awareness and knowledge of phytonutrient food sources and health benefits for functional food application among health food store customers in the Cape Town city bowl. J. Consum. Sci. 2008, 36, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollet, B.; Rowland, I. Functional foods: At the frontier between food and pharma. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2002, 13, 483–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Giménez, A.; Gámbaro, A. Influence of nutritional knowledge on perceived healthiness and willingness to try functional foods. Appetite 2008, 51, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siro, I.; Kápolna, E.; Kápolna, B.; Lugasi, A. Functional food. Product development, marketing and consumer acceptance—A review. Appetite 2008, 51, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Herrera, K.; Morales, I.V.; Ocampo-Granados, M.E.; Reyes-Morales, H.; Arce-Amaré, F.; Barquera, S. An overview of social media use in the field of public health nutrition: Benefits, scope, limitations, and a Latin American experience. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2020, 17, E76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellefson, M.; Paige, S.R.; Chaney, B.H.; Chaney, J.D. Evolving role of social media in health promotion: Updated responsibilities for health education specialists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foodintegrity.org. A Dangerous Food Disconnect When Consumers Hold You Responsible but Don’t Trust You; Technical Report; The Center for Food Integrity: Gladstone, MO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri, N.; Stefanoni, W.; Latterini, F.; Pari, L. Factors influencing Italian consumers’ willingness to pay for eggs enriched with omega-3-fatty acids. Foods 2022, 11, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.G.; Donnelly, J.K.; Jones, S.; Cade, J.E. Effect of educational interventions on understanding and use of nutrition labels: A systematic review. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Katz, D.L.; Treu, J.A.; Ayettey, R.G.; Kavak, Y.; Katz, C.S.; Njike, V. Testing the effectiveness of an abbreviated version of the nutrition detectives program. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, P.; Schroeder, S.; Burris, S.; Rayfield, J.; Baker., M. The effectiveness of a metacognitive strategy during the reading process on cognitive allocation and subject matter retention. J. Agric. Educ. 2022. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, E.; Varela, P.; Fiszman, S. Influence of nutritional knowledge on the use and interpretation of Spanish nutritional food labels. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, H1–H8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers. Available online: https://eurlex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32011R1169 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Sassi, F.; Cecchini, M.; Lauer, J.; Chisholm, D. Improving Lifestyles, Tackling Obesity: The Health and Economic Impact of Prevention Strategies; OECD Health Working Papers, No. 48; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahyoun, N.R.; Pratt, C.A.; Anderson, A. Evaluation of nutrition education interventions for older adults: A proposed framework. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, R.; Dooley, K.; Murphrey, T.; Strong, J.; Elbert, C.; Baker, M. The EVAL framework: Developing impact evaluation scholars. Adv. Agric. Dev. 2021, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The health belief model: A decade later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Consumer acceptance toward functional foods: A scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herath, D.; Cranfield, J.; Henson, S. Who consumes functional foods and nutraceuticals in Canada? Results of cluster analysis of the 2006 survey of Canadians’ demand for food products supporting health and wellness. Appetite 2008, 51, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T. Attitudes and repurchase intention of consumers towards functional foods in Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam. Int. J. Anal. Appl. 2020, 18, 212–242. [Google Scholar]

- Sääksjärvi, M.; Holmlund, M.; Tanskanen, N. Consumer knowledge of functional foods. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2009, 19, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnettler, B.; Miranda, H.; Lobos, G.; Sepúlveda, J.; Orellana, L.; Mora, M.; Grunert, K. Willingness to purchase functional foods according to their benefits. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 1453–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verneau, F.; La Barbera, F.; Furno, M. The role of health information in consumers’ willingness to pay for canned crushed tomatoes enriched with Lycopene. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baker, M.T.; Lu, P.; Parrella, J.A.; Leggette, H.R. Investigating the Effect of Consumers’ Knowledge on Their Acceptance of Functional Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11081135

Baker MT, Lu P, Parrella JA, Leggette HR. Investigating the Effect of Consumers’ Knowledge on Their Acceptance of Functional Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods. 2022; 11(8):1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11081135

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaker, Mathew T., Peng Lu, Jean A. Parrella, and Holli R. Leggette. 2022. "Investigating the Effect of Consumers’ Knowledge on Their Acceptance of Functional Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Foods 11, no. 8: 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11081135

APA StyleBaker, M. T., Lu, P., Parrella, J. A., & Leggette, H. R. (2022). Investigating the Effect of Consumers’ Knowledge on Their Acceptance of Functional Foods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods, 11(8), 1135. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11081135