How Do Smut Fungi Use Plant Signals to Spatiotemporally Orientate on and In Planta?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

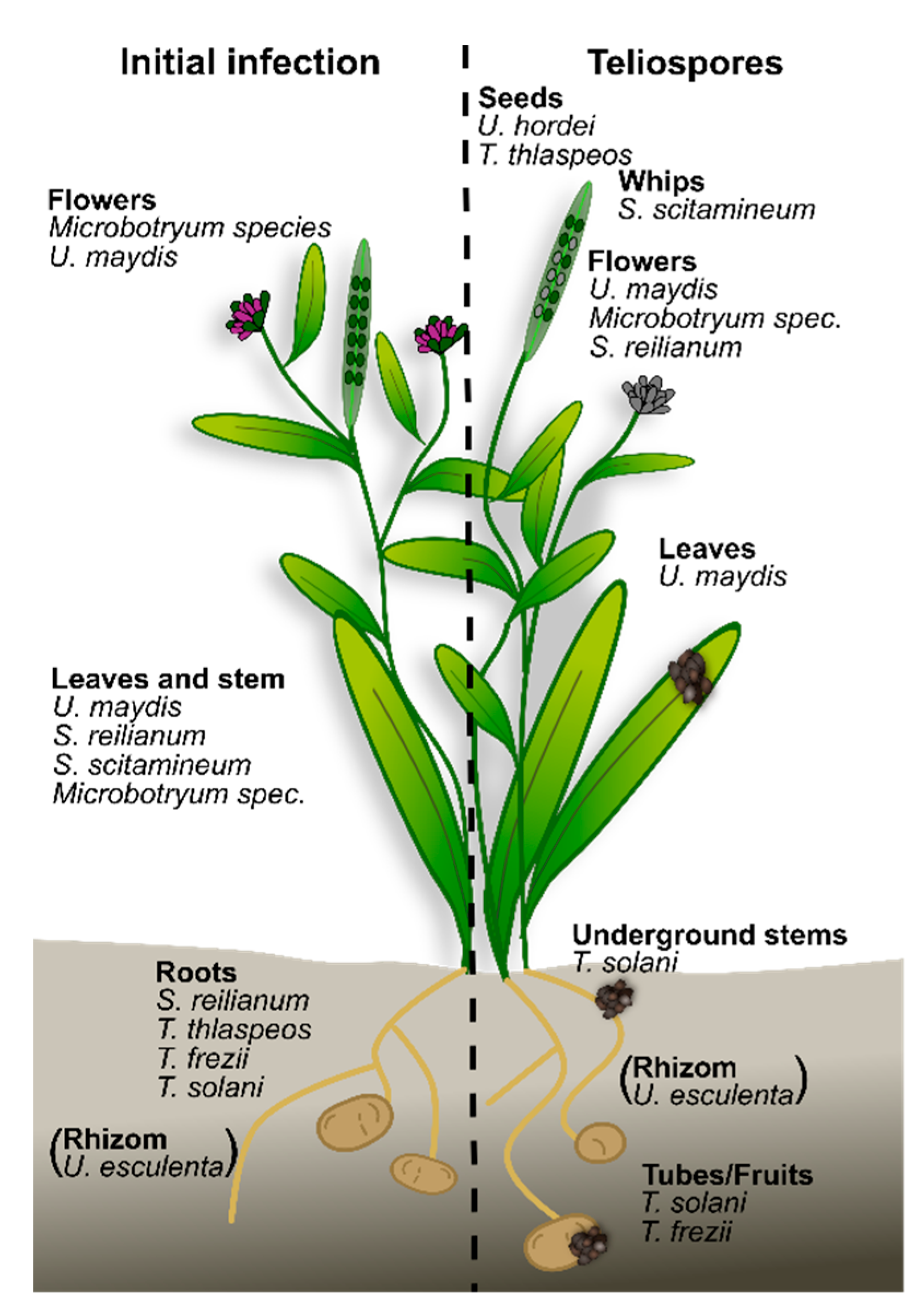

2. Smut Fungi Differ in Their Infection Strategies

3. Signals Directing Growth and Development

3.1. Signals on Planta

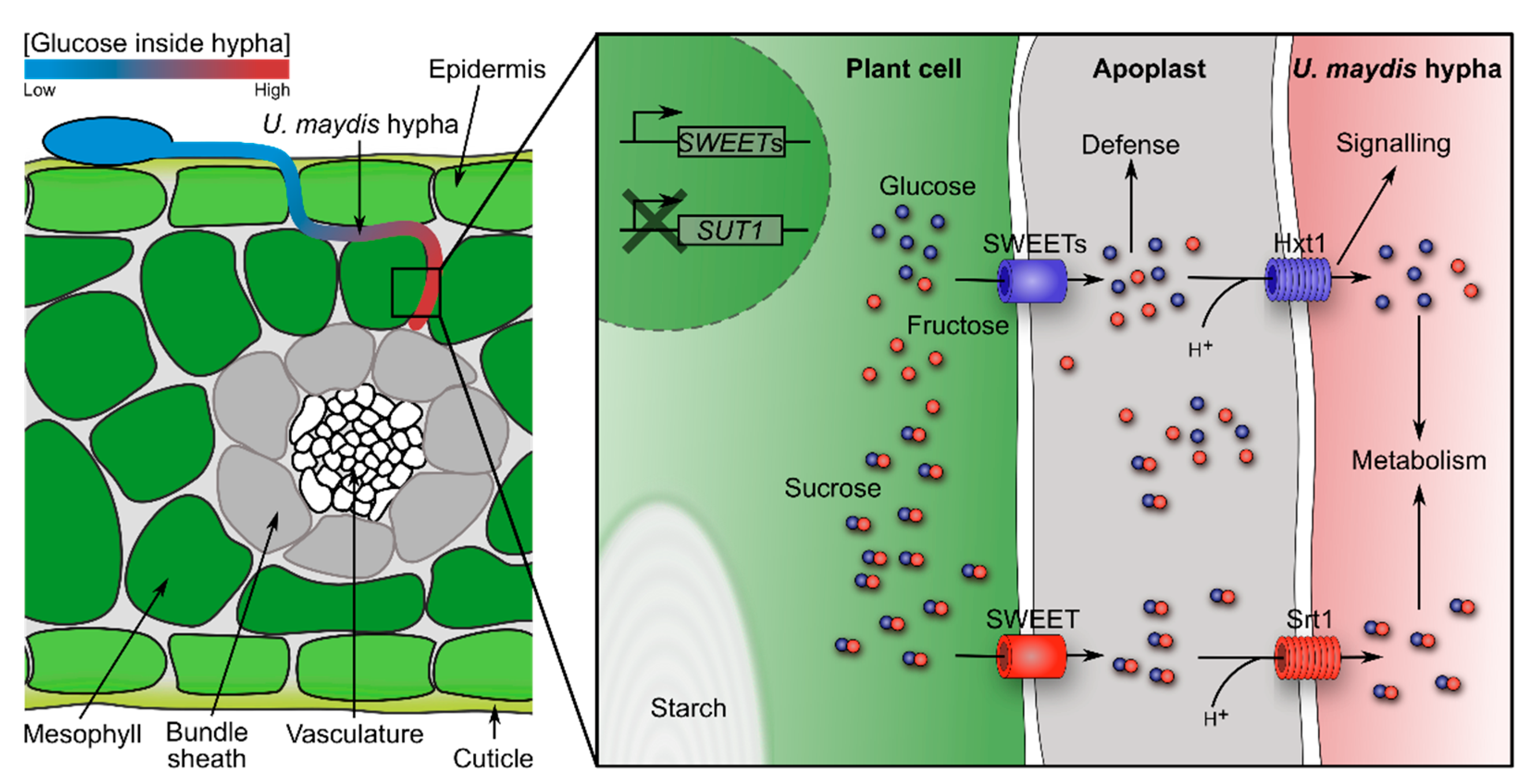

3.2. Nutrition as Signals for Directional Growth

3.3. Signals Involved in Morphological Changes of the Host

3.4. Signals for Teliospore Formation

4. Summary and Open Questions

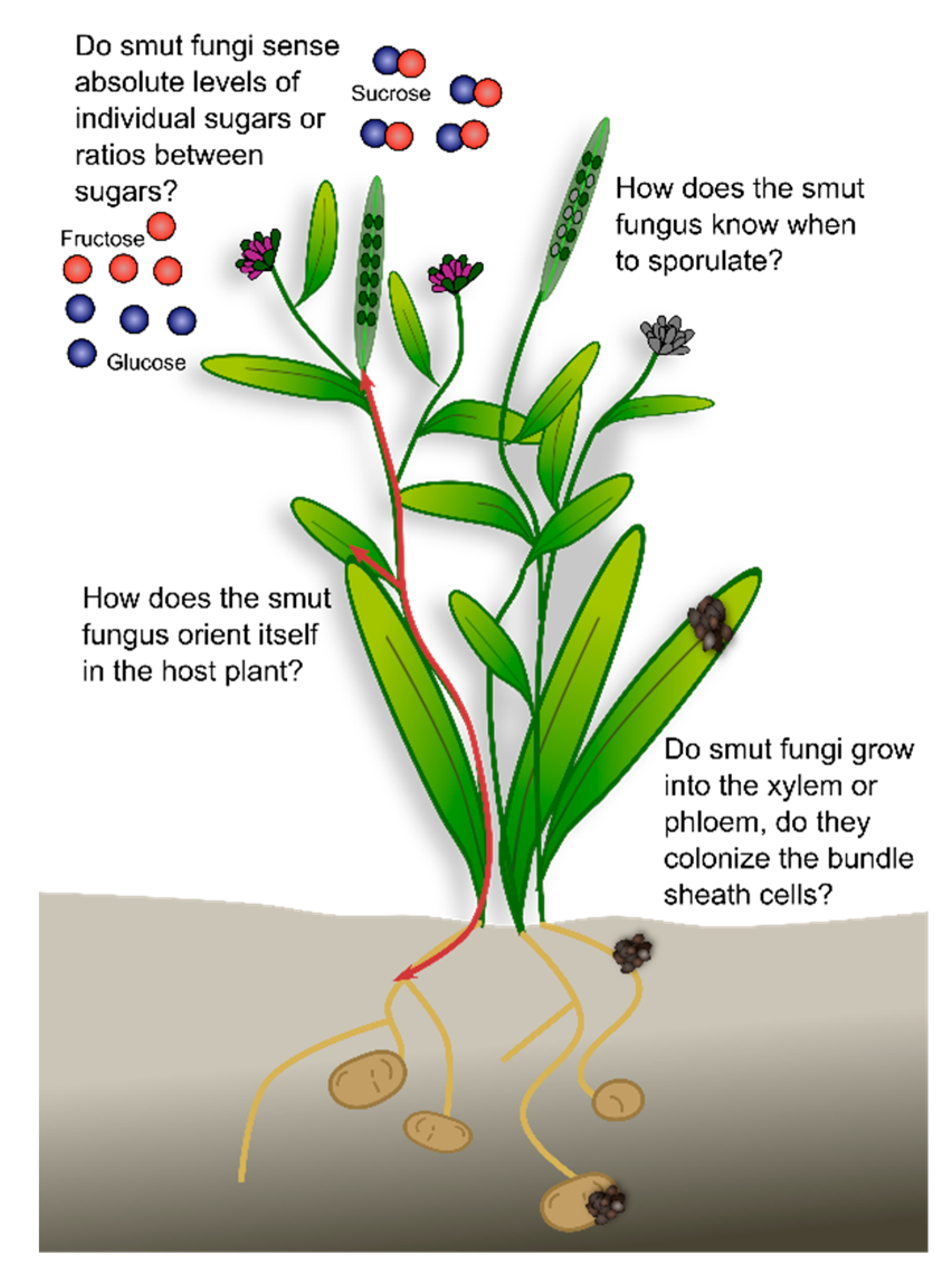

- How does the smut fungus orient itself in the host plant? For successful proliferation, it is essential that the fungus perceives plant cues as to what stage the plant is in, where it penetrated the host plant, and where to grow next. Nutrient availability might contribute to this, since it is an easy signal that could have evolved from saprophytes that follow nutrient gradients in their environment.

- Do smut fungi that follow the vasculature grow into the xylem or phloem, do they colonize the bundle sheath cells, or do they remain in the apoplastic space? Which feeding structure do the different fungi use at the different timepoints during infection? For many species, the existing microscopic data do not allow answering this question. Advanced imaging techniques combined with genetically modified reporter strains and plant lines will enable time-resolved high-resolution tracking of the fungal infection process.

- Do smut fungi sense absolute levels of individual sugars or ratios between sugars? Sugars are important nutrients for both the plant and the fungus. In addition, modification of the sucrose: glucose ratio activates the plant immune system (SWEET immunity). By sensing absolute sugar levels, the fungus would be able to follow sugar gradients to, for example, reach the vasculature or the reproductive organs. By sensing sugar ratios, the fungus might be able to tame its virulence during the biotrophic phase to avoid activation of the plant-immune system.

- How does the smut fungus know when to sporulate? Following spatiotemporal orientation, the fungus needs to decide when to sporulate. In annual plants, a general sporulation signal might be the initiation of the reproductive organs, or fertilization. In perennial host plants, the fungus needs to decide which parts of the mycelium should sporulate. Similar to the case of annual plants, this could be induced by a flowering signal that is absent from the vegetative tissues.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vánky, K. Smut fungi (Basidiomycota P.P., Ascomycota P.P.) of the world. Novelties, selected examples, trends. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2008, 55, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmeister, E.; Schipper, K.; Baumann, S.; Haag, C.; Pohlmann, T.; Stock, J.; Feldbrügge, M. Fungal development of the plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Feldbrügge, M.; Kämper, J.; Steinberg, G.; Kahmann, R. Regulation of mating and pathogenic development in Ustilago maydis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004, 7, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Muse, T.; Steinberg, G.; Pérez-Martín, J. Pheromone-induced G2 arrest in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis. Eukaryot. Cell 2003, 2, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Martín, J.; Castillo-Lluva, S. Connections between polar growth and cell cycle arrest during the induction of the virulence program in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008, 3, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freitag, J.; Lanver, D.; Böhmer, C.; Schink, K.O.; Bölker, M.; Sandrock, B. Septation of infectious hyphae is critical for appressoria formation and virulence in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schirawski, J.; Bohnert, H.U.; Steinberg, G.; Snetselaar, K.; Adamikowa, L.; Kahmann, R. Endoplasmic reticulum glucosidase II is required for pathogenicity of Ustilago maydis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3532–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lanver, D.; Berndt, P.; Tollot, M.; Naik, V.; Vranes, M.; Warmann, T.; Münch, K.; Rössel, N.; Kahmann, R. Plant surface cues prime Ustilago maydis for biotrophic development. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Yu, X.; Ye, Z. Smut fungal strategies for the successful infection. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanver, D.; Tollot, M.; Schweizer, G.; Lo Presti, L.; Reissmann, S.; Ma, L.S.; Schuster, M.; Tanaka, S.; Liang, L.; Ludwig, N.; et al. Ustilago maydis effectors and their impact on virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, L.; Kahmann, R. How filamentous plant pathogen effectors are translocated to host cells. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 38, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redkar, A.; Hoser, R.; Schilling, L.; Zechmann, B.; Krzymowska, M.; Walbot, V.; Doehlemann, G. A secreted effector protein of Ustilago maydis guides maize leaf cells to form tumors. Plant Cell 2015, 27, 1332–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tollot, M.; Assmann, D.; Becker, C.; Altmüller, J.; Dutheil, J.Y.; Wegner, C.-E.; Kahmann, R. The WOPR Protein Ros1 is a master regulator of sporogenesis and late effector gene expression in the maize pathogen Ustilago maydis. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanver, D.; Müller, A.N.; Happel, P.; Schweizer, G.; Haas, F.B.; Franitza, M.; Pellegrin, C.; Reissmann, S.; Altmüller, J.; Rensing, S.A.; et al. The biotrophic development of Ustilago maydis studied by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kawamoto, H.; Hirata, A.; Kawano, S. Three-dimensional ultrastructural study of the anther of Silene latifolia infected with Microbotryum lychnidis-dioicae. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uchida, W.; Matsunaga, S.; Sugiyama, R.; Kazama, Y.; Kawano, S. Morphological development of anthers induced by the dimorphic smut fungus Microbotryum violaceum in female flowers of the dioecious plant Silene latifolia. Planta 2003, 218, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schäfer, A.M.; Kemler, M.; Bauer, R.; Begerow, D. The illustrated life cycle of Microbotryum on the host plant Silene latifolia. Botany 2010, 88, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.; Jauneau, A.; Roux, C.; Savy, C.; Dargent, R. Early infection of maize roots by Sporisorium reilianum f. sp. zeae. Protoplasma 2000, 213, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C.; Roux, C.; Jauneau, A.; Dargent, R. The biological cycle of Sporisorium reilianum f.sp. zeae: An overview using microscopy. Mycologia 2002, 94, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ye, J.; Wei, L.; Zhang, N.; Xing, Y.; Zuo, W.; Chao, Q.; Tan, G.; Xu, M. Inhibition of the spread of endophytic Sporisorium reilianum renders maize resistance to head smut. Crop J. 2015, 3, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghareeb, H.; Becker, A.; Iven, T.; Feussner, I.; Schirawski, J. Sporisorium reilianum infection changes inflorescence and branching architectures of maize. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 2037–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matheussen, A.-M.; Morgan, P.W.; Frederiksen, R.A. Implication of gibberellins in head smut Sporisorium reilianum of Sorghum bicolor. Plant Physiol. 1991, 96, 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ökmen, B.; Mathow, D.; Hof, A.; Lahrmann, U.; Aßmann, D.; Doehlemann, G. Mining the effector repertoire of the biotrophic fungal pathogen Ustilago hordei during host and non-host infection. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 2603–2622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, G.G.; Linning, R.; Bakkeren, G. Sporidial mating and infection process of the smut fungus, Ustilago hordei, in susceptible barley. Can. J. Bot. 2002, 80, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sundar, A.R.; Leonard, B.E.; Malathi, P.; Viswanathan, R. A mini-review on smut disease of sugarcane caused by Sporisorium scitamineum. In Botany; Mworia, J.K., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, J.P.R.; Appezzato-da-Glória, B.; Piepenbring, M.; Massola, N.S., Jr.; Monteiro-Vitorello, C.B.; Vieira, M.L.C. Sugarcane smut: Shedding light on the development of the whip-shaped sorus. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Taniguti, L.M.; Schaker, P.D.C.; Benevenuto, J.; Peters, L.P.; Carvalho, G.; Palhares, A.; Quecine, M.C.; Nunes, F.R.S.; Kmit, M.C.P.; Wai, A.; et al. Complete genome sequence of Sporisorium scitamineum and biotrophic interaction transcriptome with sugarcane. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrell, E.E.; Batra, L.R. Zizania latifolia and Ustilago esculenta, a grass-fungus association. Econ. Bot. 1982, 36, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, K.-R.; Tzeng, D.D. Nutritional requirements of the edible gall-producing fungus Ustilago esculenta. J. Biol. Sci. 2004, 4, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ye, Z.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, H.; Jin, G.; McHardy, A.C.; Fan, L.; Yu, X. Comparative whole-genome analysis reveals artificial selection effects on Ustilago esculenta genome. DNA Res. 2017, 24, 635–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrade, O.; Munoz, G.; Galdames, R.; Duran, P.; Honorato, R. Characterization, in vitro culture, and molecular analysis of Thecaphora solani, the causal agent of potato smut. Phytopathology 2004, 94, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rago, A.M.; Cazón, L.I.; Paredes, J.A.; Molina, J.P.E.; Conforto, E.C.; Bisonard, E.M.; Oddino, C. Peanut smut: From an emerging disease to an actual threat to Argentine peanut production. Plant Dis. 2017, 101, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Torres, H.; Stevenson, W.R.; Loria, R.; Franc, G.D.; Weingartner, D.P. Thecaphora smut. In Compendium of Potato Diseases; APS Press: Saint Paul, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- Cazón, L.I.; Paredes, J.A.; Rago, A.M. The Biology of Thecaphora Frezii Smut and Its Effects on Argentine Peanut Production; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Health, E.; Panel, O.P.; Bragard, C.; Dehnen-Schmutz, K.; Di Serio, F.; Gonthier, P.; Jacques, M.-A.; Jaques Miret, J.A.; Justesen, A.F.; MacLeod, A.; et al. Pest categorisation of Thecaphora solani. Efsa J. 2018, 16, e05445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vánky, K.; Lutz, M.; Bauer, R. About the genus Thecaphora (Glomosporiaceae) and its new synonyms. Mycol. Prog. 2008, 7, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskakis, L.; Courville, K.J.; Pluecker, L.; Kellner, R.; Kruse, J.; Brachmann, A.; Feldbrügge, M.; Göhre, V. The plant-dependent life cycle of Thecaphora thlaspeos: A smut fungus adapted to Brassicaceae. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2017, 30, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vánky, K. The smut fungi of the world. A survey. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2002, 49, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courville, K.J.; Frantzeskakis, L.; Gul, S.; Haeger, N.; Kellner, R.; Heßler, N.; Day, B.; Usadel, B.; Gupta, Y.K.; van Esse, H.P.; et al. Smut infection of perennial hosts: The genome and the transcriptome of the Brassicaceae smut fungus Thecaphora thlaspeos reveal functionally conserved and novel effectors. New Phytol. 2019, 222, 1474–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, R.; Göhre, V. Thecaphora thlaspeos–ein Brandpilz spezialisiert auf Modellpflanzen. Biospektrum 2017, 23, 498–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plücker, L.; Bösch, K.; Geißl, L.; Hoffmann, P.; Göhre, V. Genetic manipulation of the Brassicaceae smut fungus Thecaphora thlaspeos. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Jhooty, J.S. Stimulation of germination in teliospores of Urocystis agropyri by volatiles from plant tissues. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1987, 111, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göhre, V.; HHU, Düsseldorf, Germany. Ethylene was part of a series of plant hormones tested for germination-inducing activity. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Berndt, P.; Djamei, A.; Weise, C.; Linne, U.; Marahiel, M.; Vraneš, M.; Kämper, J.; Kahmann, R. Physical-chemical plant-derived signals induce differentiation in Ustilago maydis. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 71, 895–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanver, D.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Brachmann, A.; Kahmann, R. Sho1 and Msb2-related proteins regulate appressorium development in the smut fungus Ustilago maydis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 2085–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brachmann, A.; Schirawski, J.; Müller, P.; Kahmann, R. An unusual MAP kinase is required for efficient penetration of the plant surface by Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 2199–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kijpornyongpan, T.; Aime, M.C. Investigating the smuts: Common cues, signaling pathways, and the role of MAT in dimorphic switching and pathogenesis. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, W.; Ökmen, B.; Depotter, J.R.L.; Ebert, M.K.; Redkar, A.; Villamil, J.M.; Doehlemann, G. Molecular interactions between smut fungi and their host plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2019, 57, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehlemann, G.; Wahl, R.; Horst, R.J.; Voll, L.M.; Usadel, B.; Poree, F.; Stitt, M.; Pons-Kühnemann, J.; Sonnewald, U.; Kahmann, R.; et al. Reprogramming a maize plant: Transcriptional and metabolic changes induced by the fungal biotroph Ustilago maydis. Plant J. 2008, 56, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matei, A.; Ernst, C.; Gunl, M.; Thiele, B.; Altmüller, J.; Walbot, V.; Usadel, B.; Doehlemann, G. How to make a tumour: Cell type specific dissection of Ustilago maydis-induced tumour development in maize leaves. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 1681–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horst, R.J.; Doehlemann, G.; Wahl, R.; Hofmann, J.; Schmiedl, A.; Kahmann, R.; Kämper, J.; Sonnewald, U.; Voll, L.M. Ustilago maydis infection strongly alters organic nitrogen allocation in maize and stimulates productivity of systemic source leaves. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sosso, D.; van der Linde, K.; Bezrutczyk, M.; Schuler, D.; Schneider, K.; Kämper, J.; Walbot, V. Sugar partitioning between Ustilago maydis and its host Zea mays L during infection. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, R.; Wippel, K.; Goos, S.; Kämper, J.; Sauer, N. A novel high-affinity sucrose transporter is required for virulence of the plant pathogen Ustilago maydis. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8, e1000303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schuler, D.; Wahl, R.; Wippel, K.; Vranes, M.; Münsterkötter, M.; Sauer, N.; Kämper, J. Hxt1, a monosaccharide transporter and sensor required for virulence of the maize pathogen Ustilago maydis. New Phytol. 2015, 206, 1086–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardlaw, I.F. Tansley Review No. 27 The control of carbon partitioning in plants. New Phytol. 1990, 116, 341–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skibbe, D.S.; Doehlemann, G.; Fernandes, J.; Walbot, V. Maize tumors caused by Ustilago maydis require organ-specific genes in host and pathogen. Science 2010, 328, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bezrutczyk, M.; Yang, J.; Eom, J.-S.; Prior, M.; Sosso, D.; Hartwig, T.; Szurek, B.; Oliva, R.; Vera-Cruz, C.; White, F.F.; et al. Sugar flux and signaling in plant–microbe interactions. Plant J. 2018, 93, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naseem, M.; Kunz, M.; Dandekar, T. Plant-pathogen maneuvering over apoplastic sugars. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 740–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doehlemann, G.; Wahl, R.; Vraneš, M.; de Vries, R.P.; Kämper, J.; Kahmann, R. Establishment of compatibility in the Ustilago maydis/maize pathosystem. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirawski, J.; Mannhaupt, G.; Münch, K.; Brefort, T.; Schipper, K.; Doehlemann, G.; Di Stasio, M.; Rössel, N.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Pester, D.; et al. Pathogenicity determinants in smut fungi revealed by genome comparison. Science 2010, 330, 1546–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, Y.; Xu, L.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ling, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J.; Su, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Genome sequencing of Sporisorium scitamineum provides insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of sugarcane smut. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Redkar, A.; Villajuana-Bonequi, M.; Doehlemann, G. Conservation of the Ustilago maydis effector See1 in related smuts. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e1086855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morrison, E.N.; Emery, R.J.N.; Saville, B.J. Phytohormone involvement in the Ustilago maydis–Zea mays pathosystem: Relationships between abscisic acid and cytokinin levels and strain virulence in infected cob tissue. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0130945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walters, D.R.; McRoberts, N. Plants and biotrophs: A pivotal role for cytokinins? Trends Plant Sci 2006, 11, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, M.; Croll, D.; Kronstad, J.W. Maize susceptibility to Ustilago maydis is influenced by genetic and chemical perturbation of carbohydrate allocation. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 1222–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Linde, K.; Walbot, V. Pre-meiotic anther development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2019, 131, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Kelliher, T.; Nguyen, L.; Walbot, V. Ustilago maydis reprograms cell proliferation in maize anthers. Plant J. 2013, 75, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ghareeb, H.; Drechsler, F.; Löfke, C.; Teichmann, T.; Schirawski, J. Suppressor of Apical Dominance1 of Sporisorium reilianum modulates inflorescence branching architecture in maize and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015, 169, 2789–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, X.; McSteen, P. The role of auxin transport during inflorescence development in maize (Zea mays, Poaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2007, 94, 1745–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gardiner, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, F.; Zheng, Y. Floral transition in maize infected with Sporisorium reilianum disrupts compatibility with this biotrophic fungal pathogen. Planta 2013, 237, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walbot, V.; Skibbe, D.S. Maize host requirements for Ustilago maydis tumor induction. Sex Plant Reprod. 2010, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kinoshita, A.; Richter, R. Genetic and molecular basis of floral induction in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 2490–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, L.-H.; Pasriga, R.; Yoon, J.; Jeon, J.-S.; An, G. Roles of sugars in controlling flowering time. J. Plant Biol. 2018, 61, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijser, P.; Schmid, M. The control of developmental phase transitions in plants. Development 2011, 138, 4117–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meitzel, T.; Radchuk, R.; McAdam, E.L.; Thormählen, I.; Feil, R.; Munz, E.; Hilo, A.; Geigenberger, P.; Ross, J.J.; Lunn, J.E.; et al. Trehalose 6-phosphate promotes seed filling by activating auxin biosynthesis. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van der Linde, K.; Göhre, V. How Do Smut Fungi Use Plant Signals to Spatiotemporally Orientate on and In Planta? J. Fungi 2021, 7, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020107

van der Linde K, Göhre V. How Do Smut Fungi Use Plant Signals to Spatiotemporally Orientate on and In Planta? Journal of Fungi. 2021; 7(2):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020107

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan der Linde, Karina, and Vera Göhre. 2021. "How Do Smut Fungi Use Plant Signals to Spatiotemporally Orientate on and In Planta?" Journal of Fungi 7, no. 2: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020107

APA Stylevan der Linde, K., & Göhre, V. (2021). How Do Smut Fungi Use Plant Signals to Spatiotemporally Orientate on and In Planta? Journal of Fungi, 7(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof7020107