Refining Oxide Ratios in N-A-S-H Geopolymers for Optimal Resistance to Sulphuric Acid Attack

Abstract

:1. Introduction

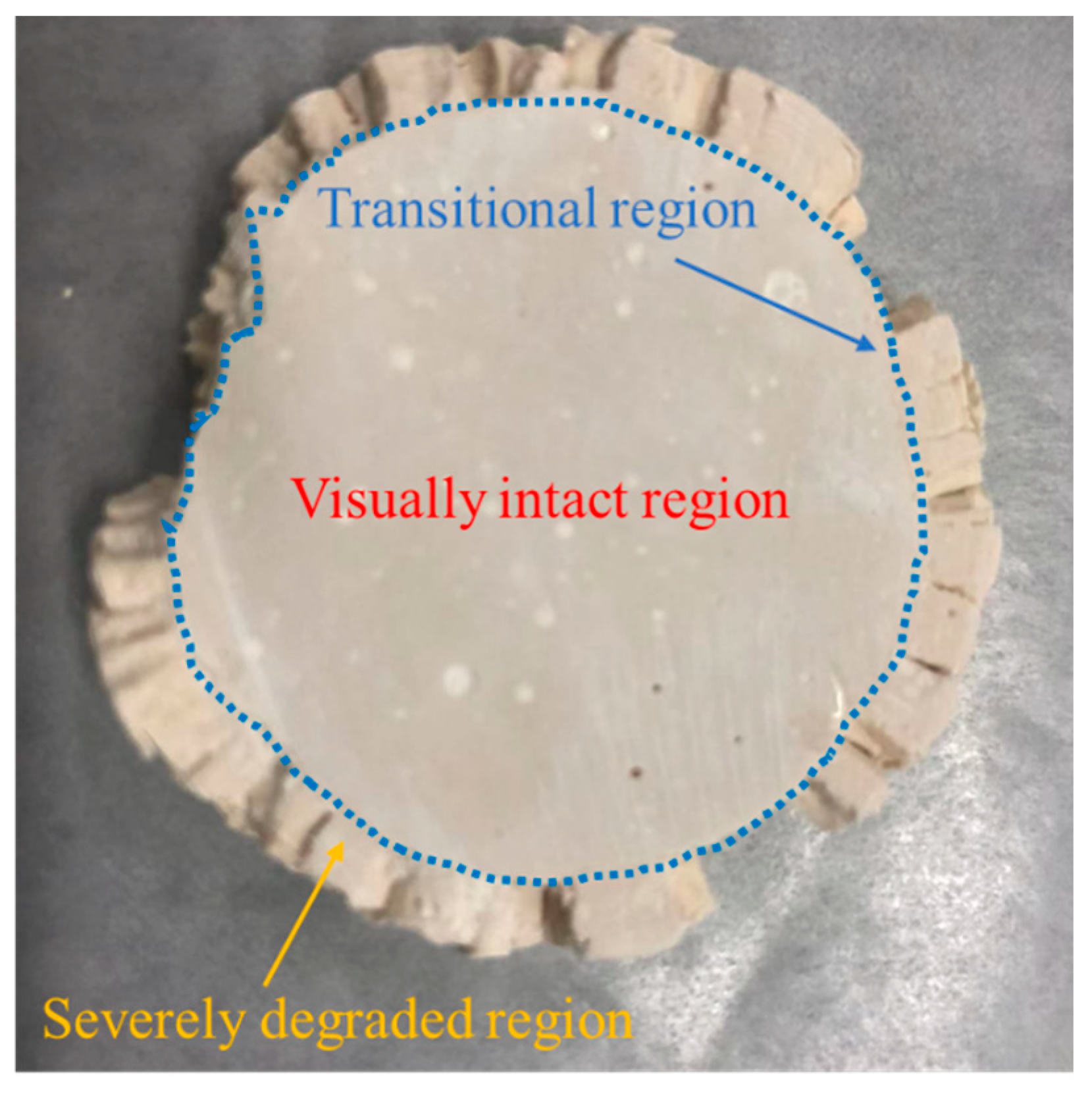

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportions and Specimens

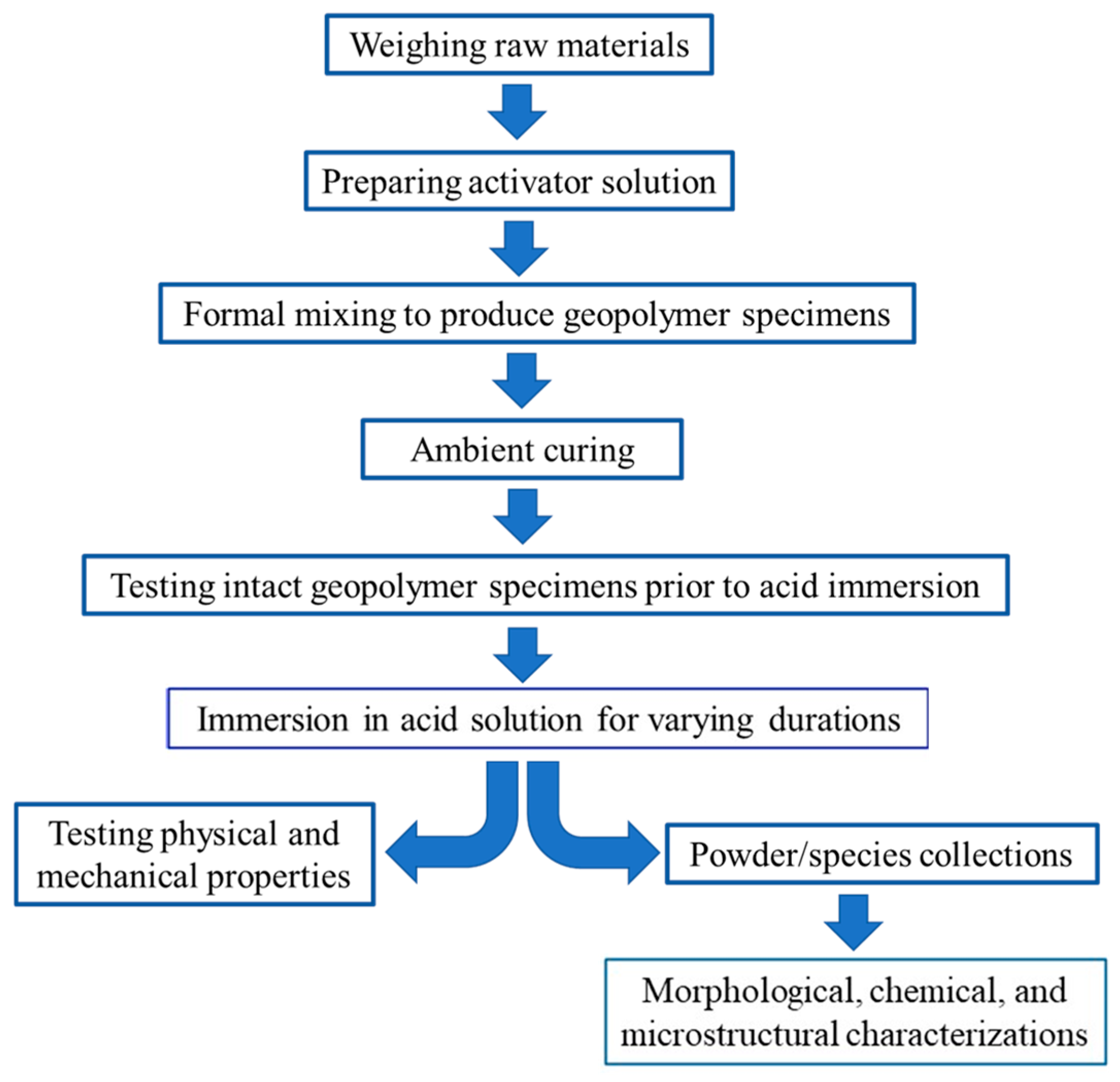

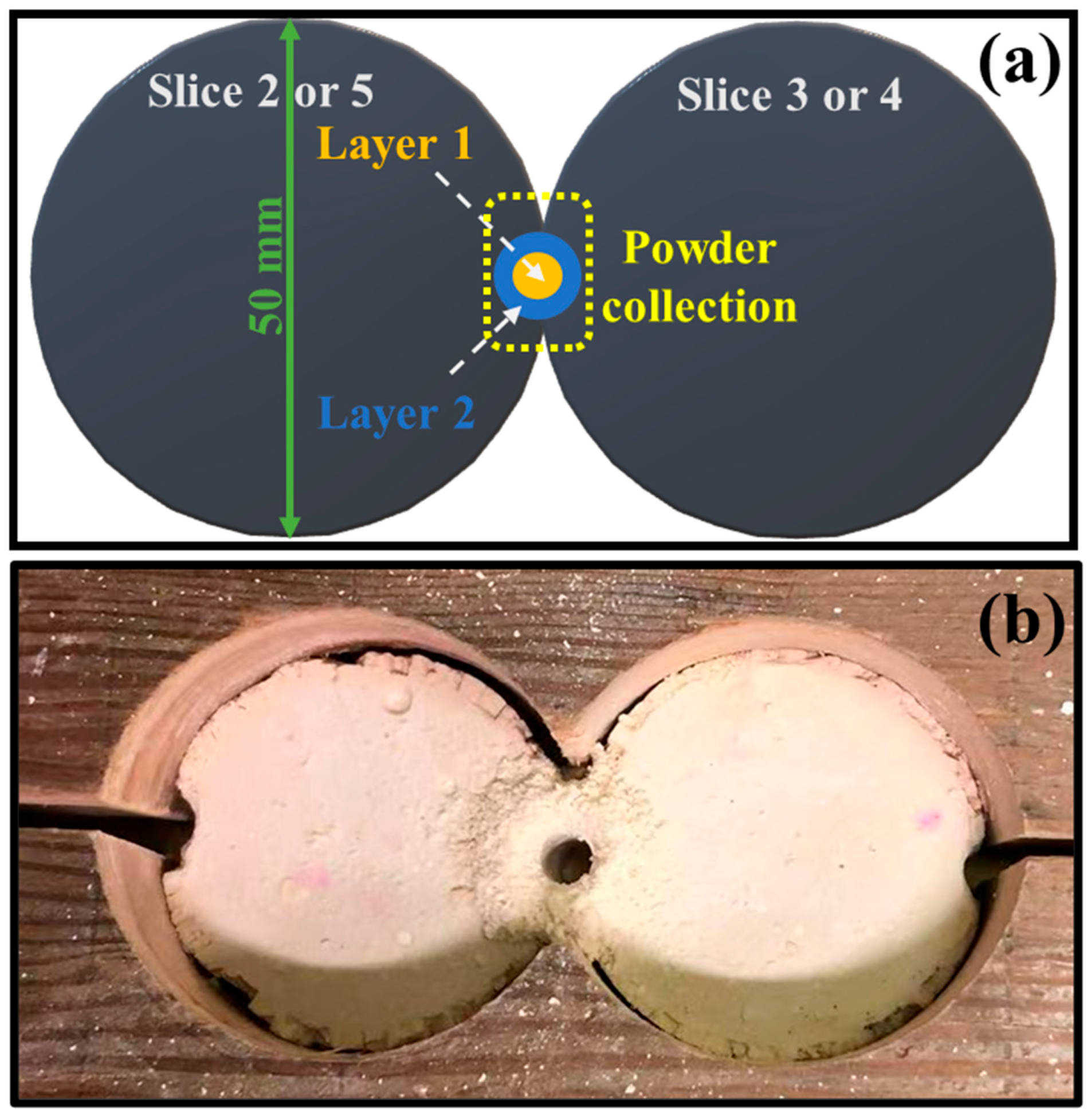

2.3. Test Protocols and Sample Collections

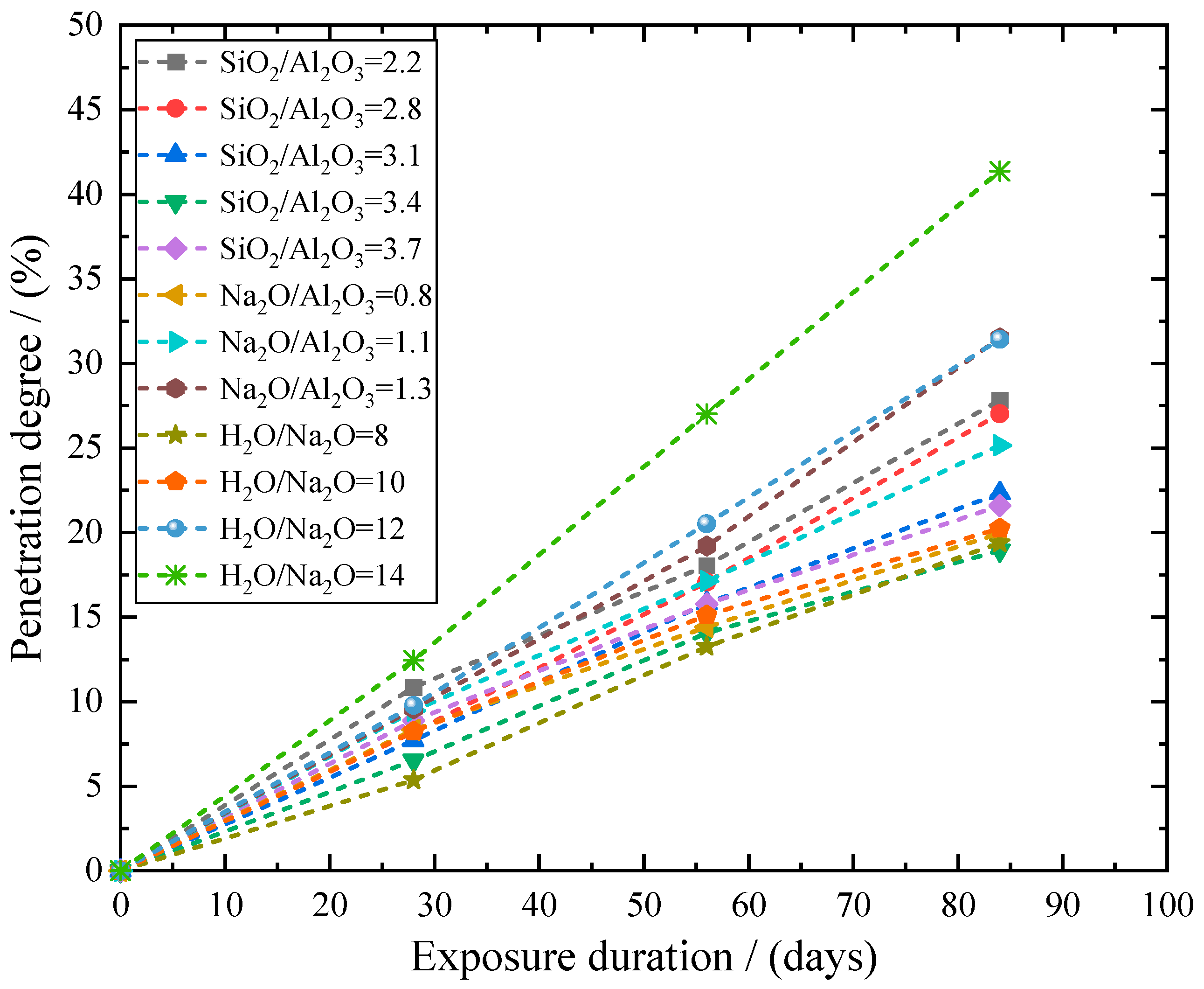

2.4. Testing Program

3. Experimental Results and Analyses

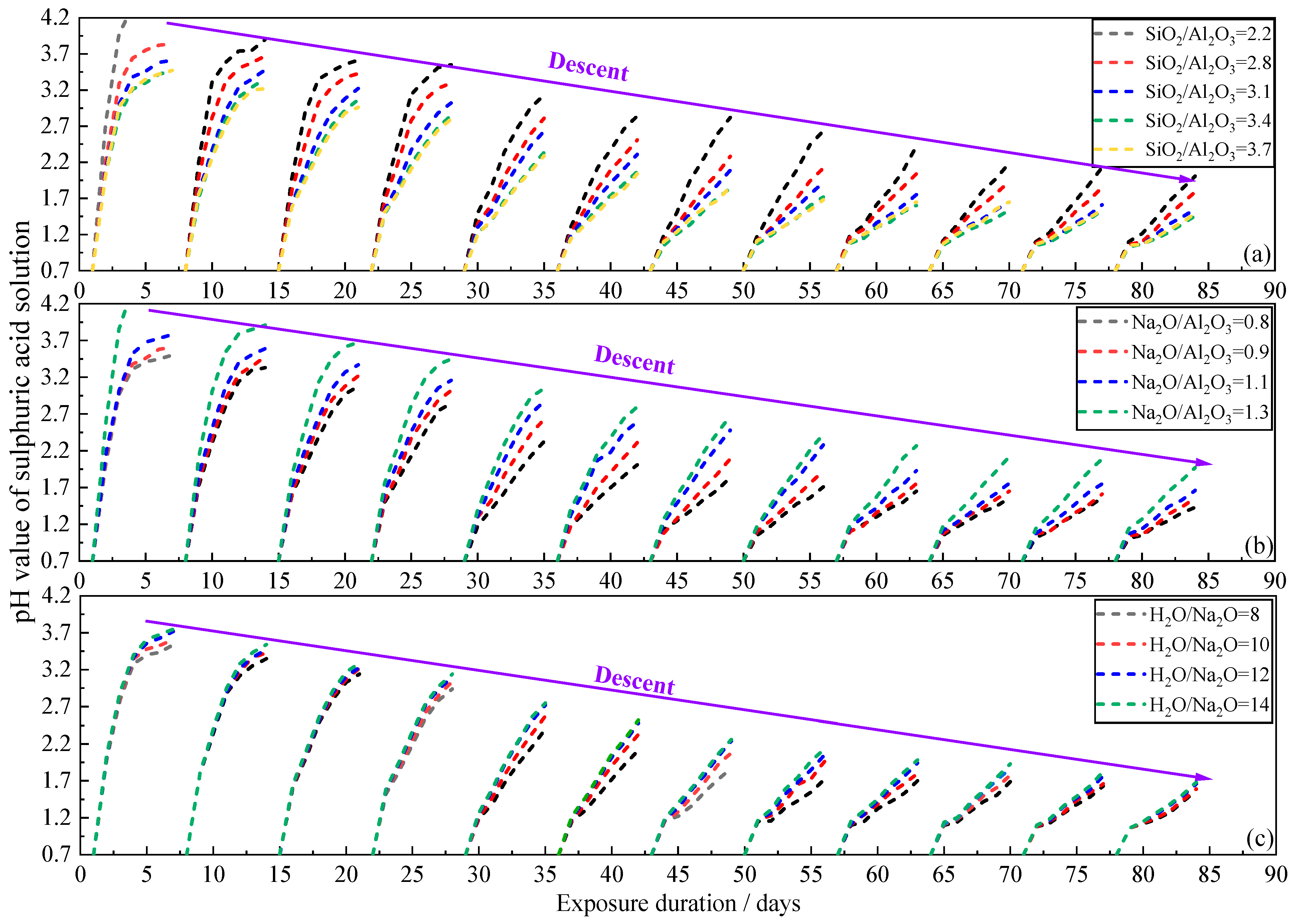

3.1. pH Evolution of Sulphuric Acid Solution

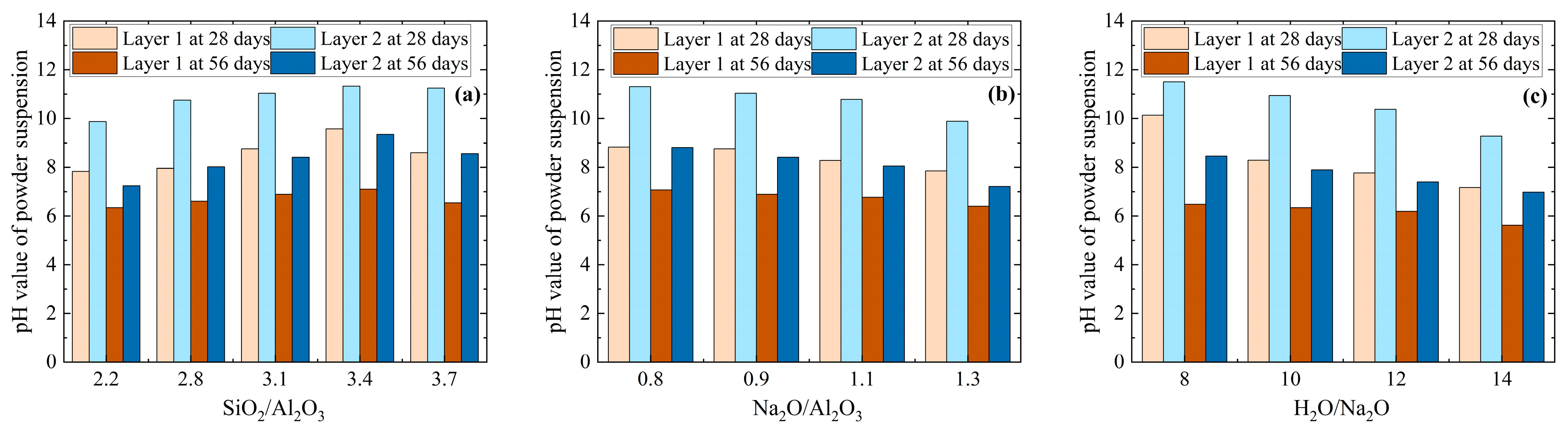

3.2. Loss in Alkalinity

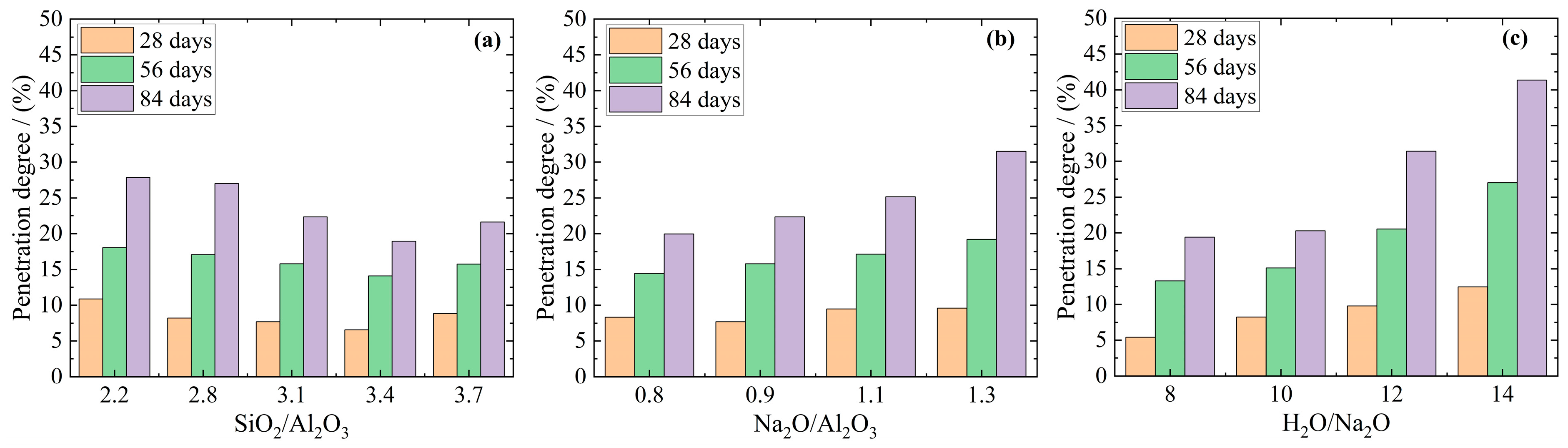

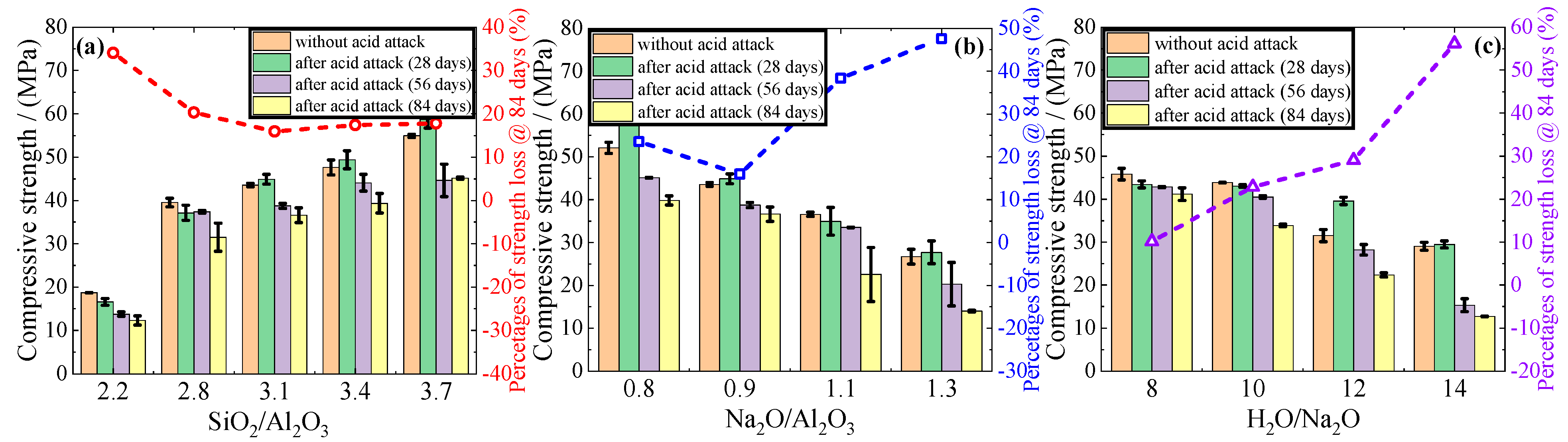

3.3. Changes in Mass, Diameter, and Compressive Strength

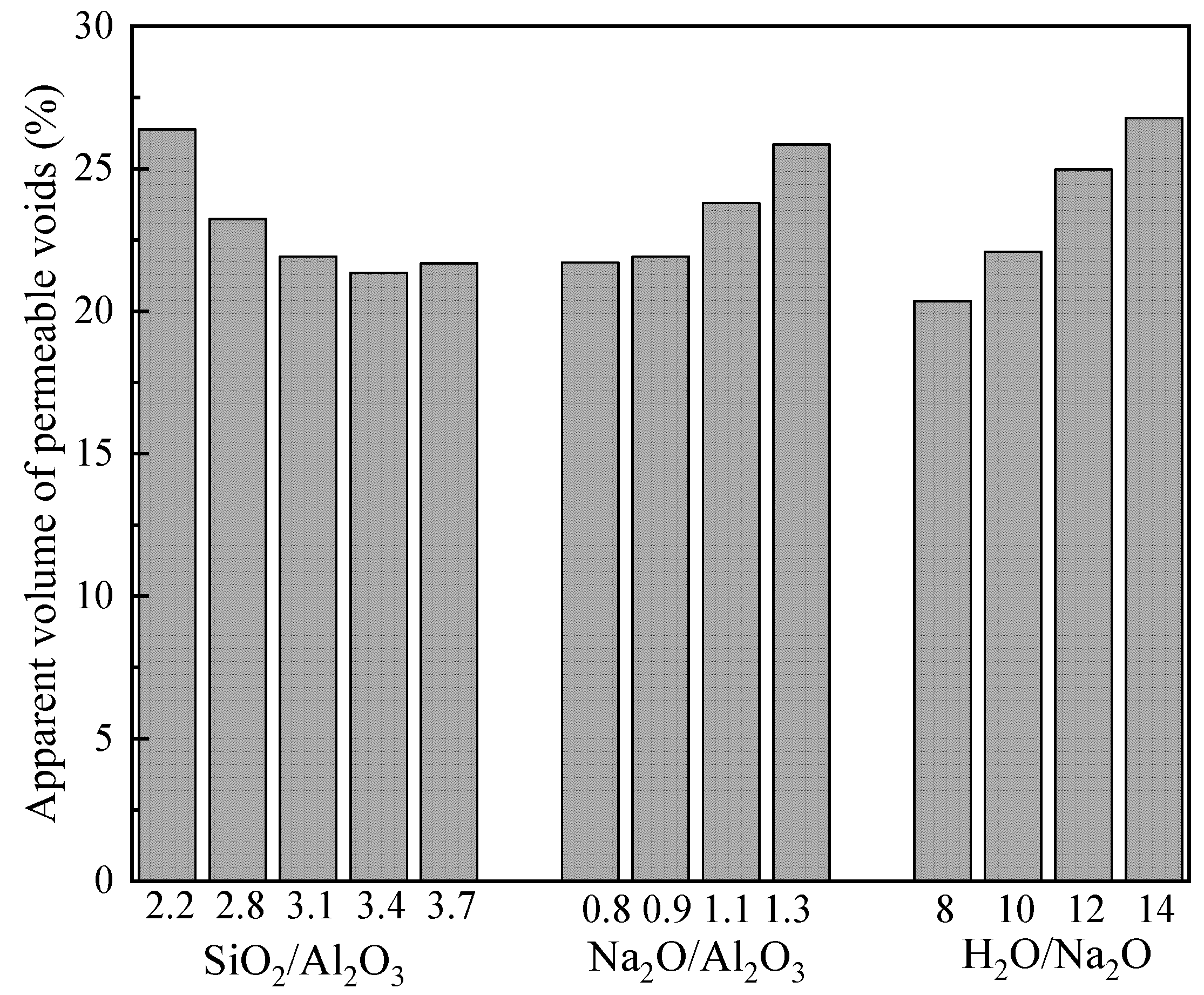

3.4. Apparent Volume of Permeable Voids

3.5. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

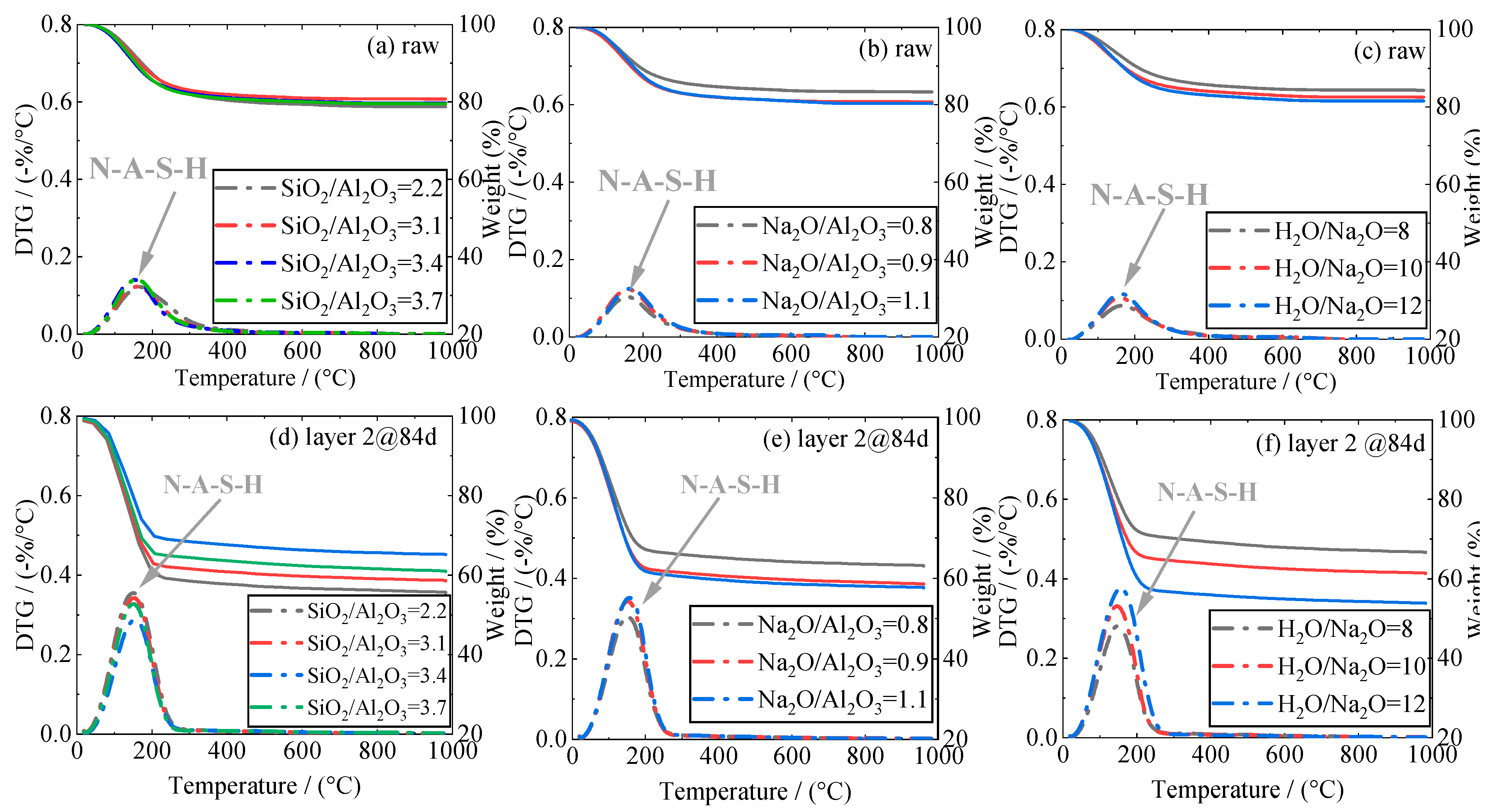

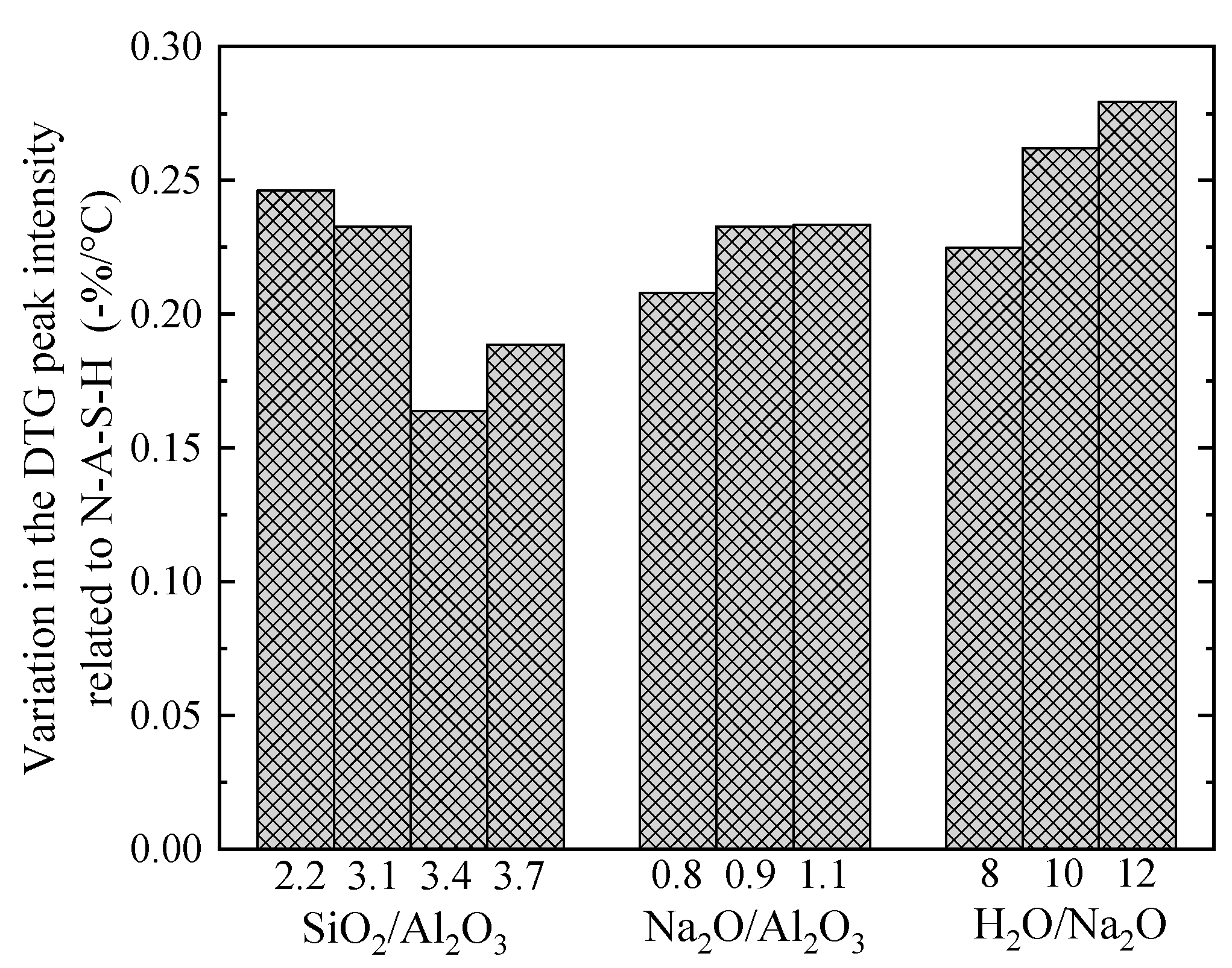

3.6. Thermo-Gravimetric Analysis (TGA)

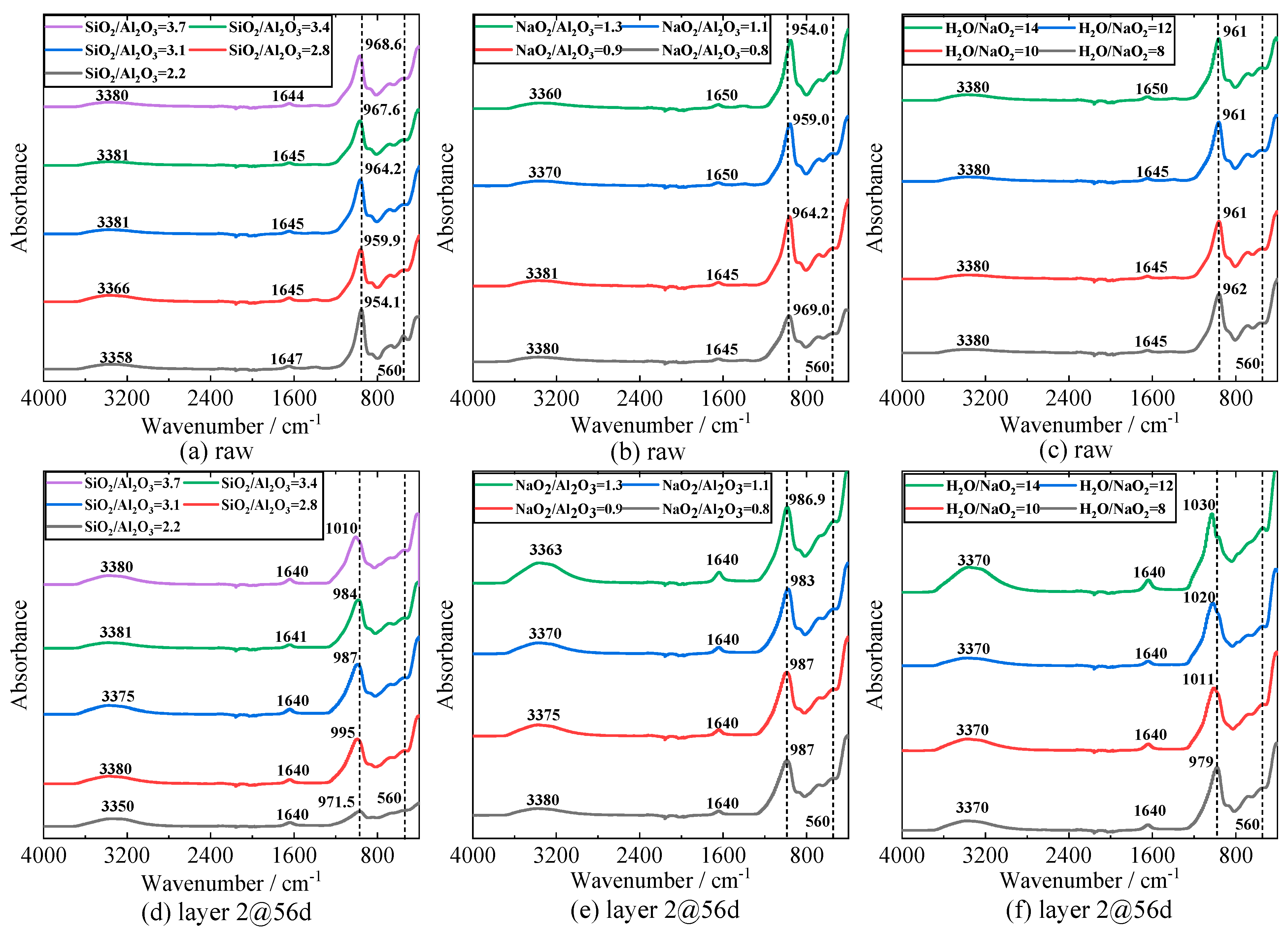

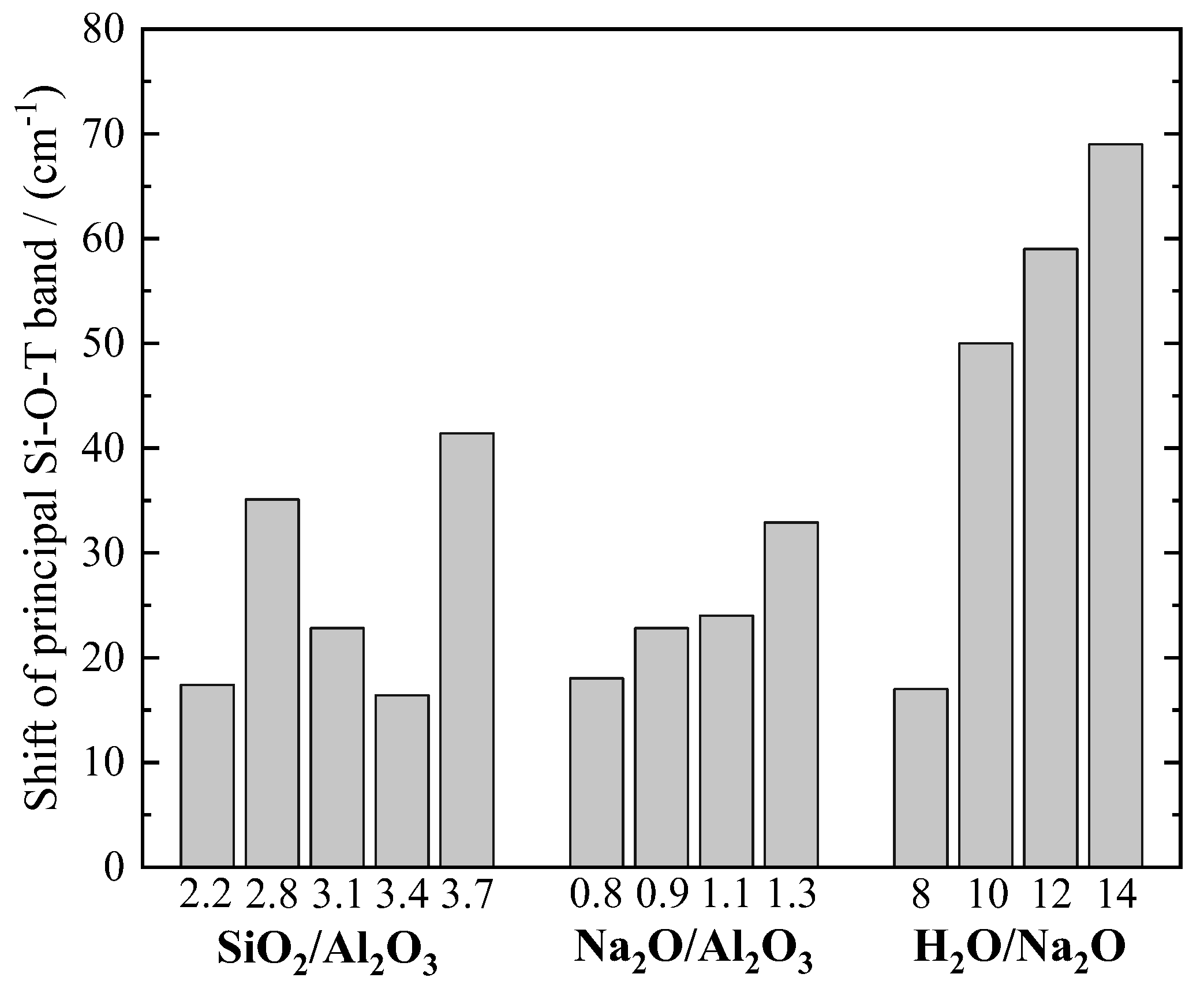

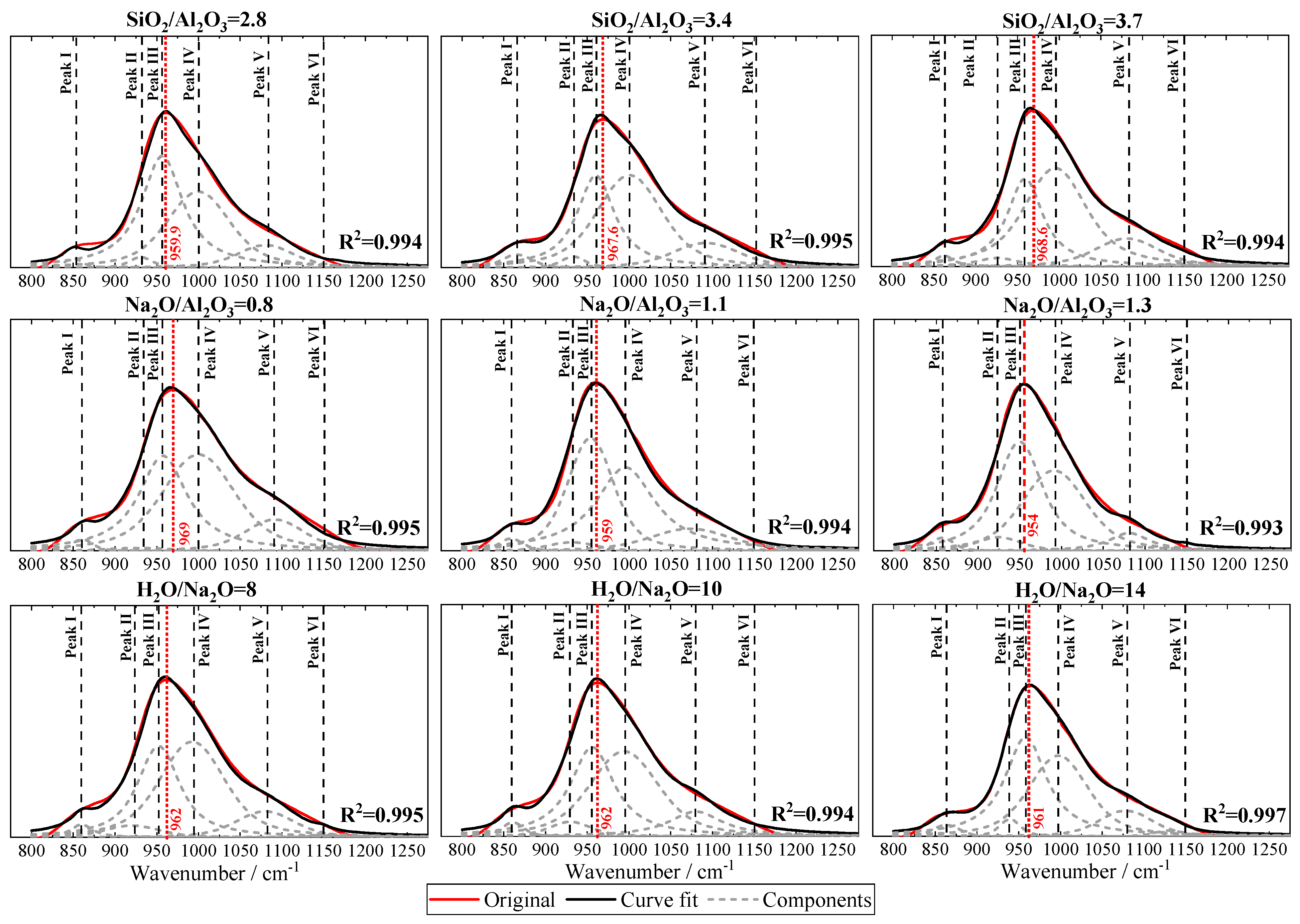

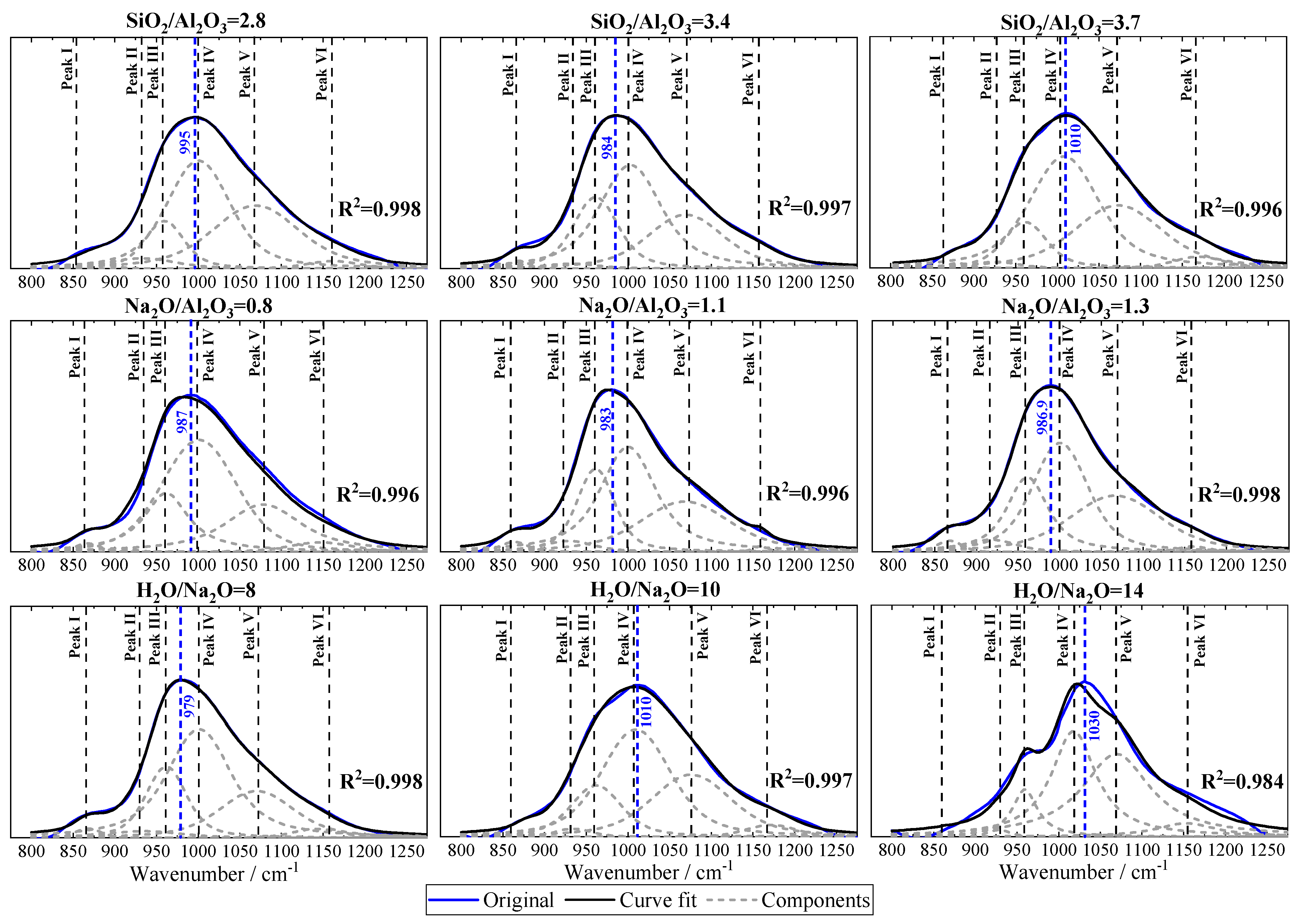

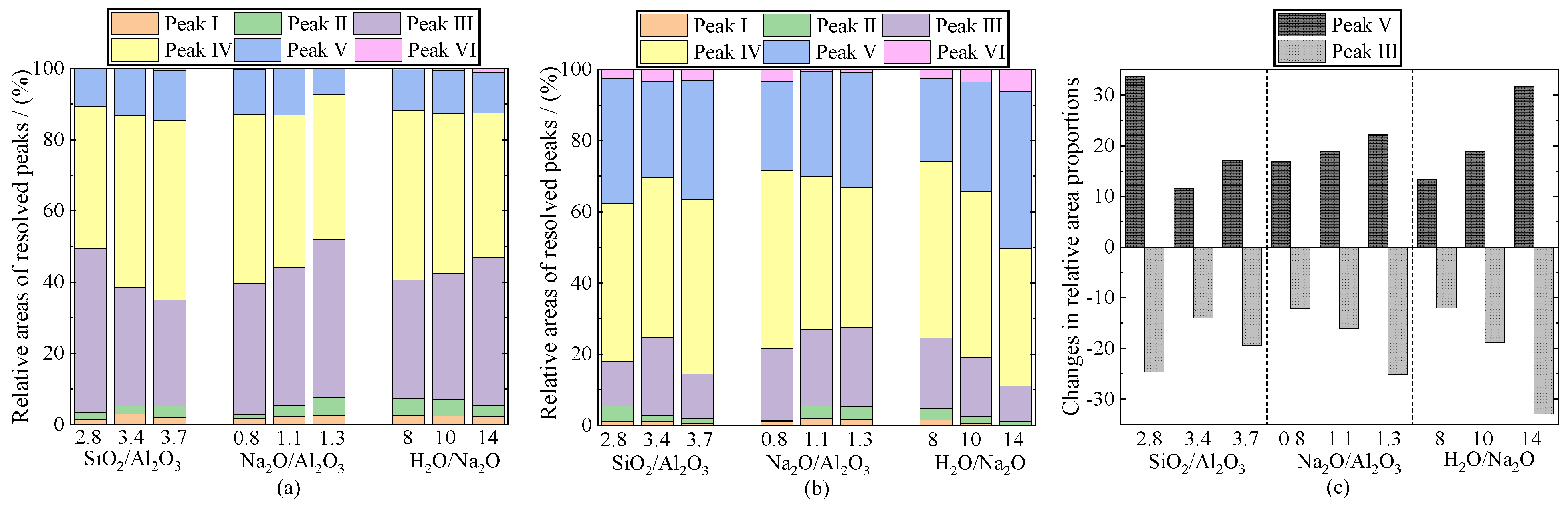

3.7. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

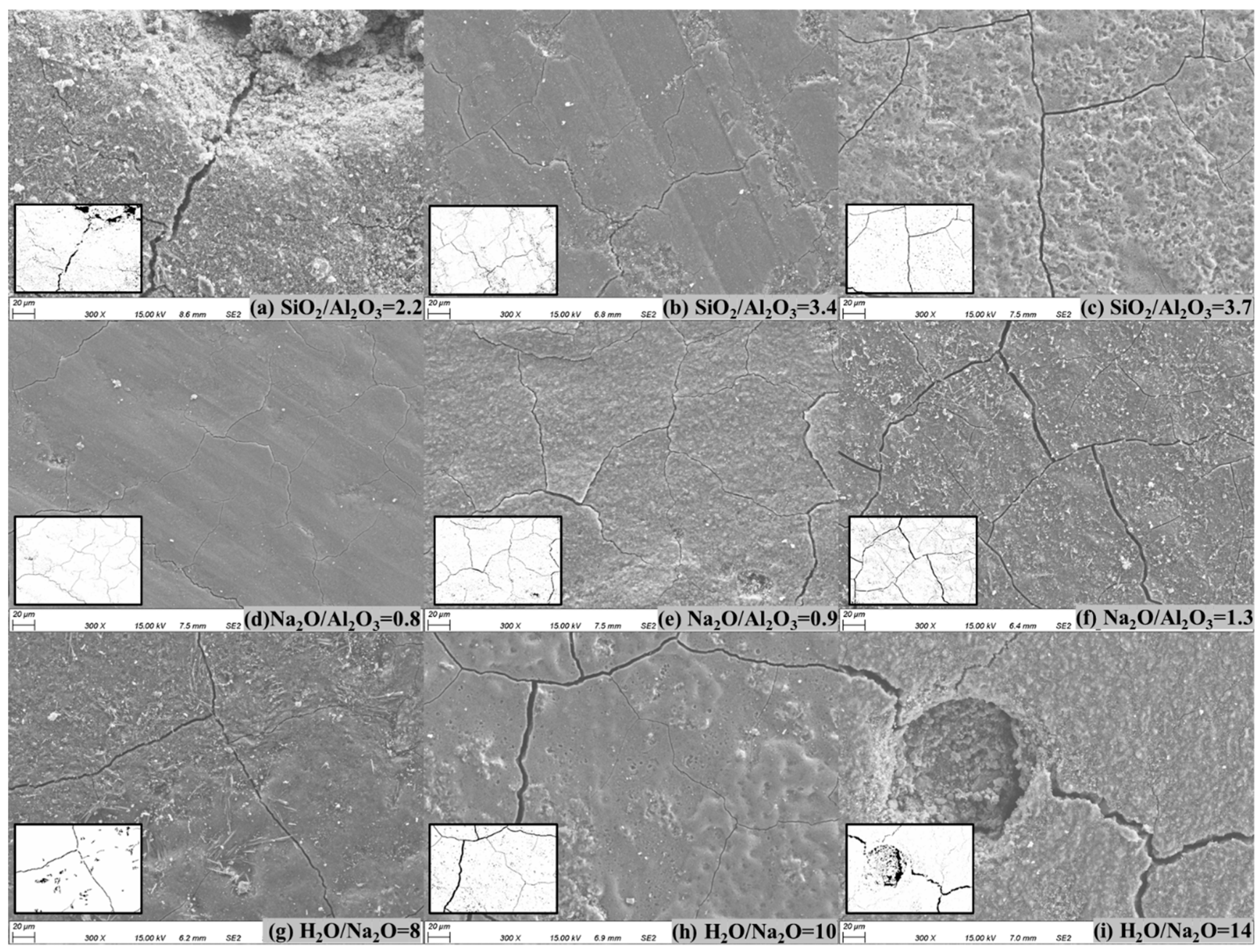

3.8. Scanning Electron Microscope and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

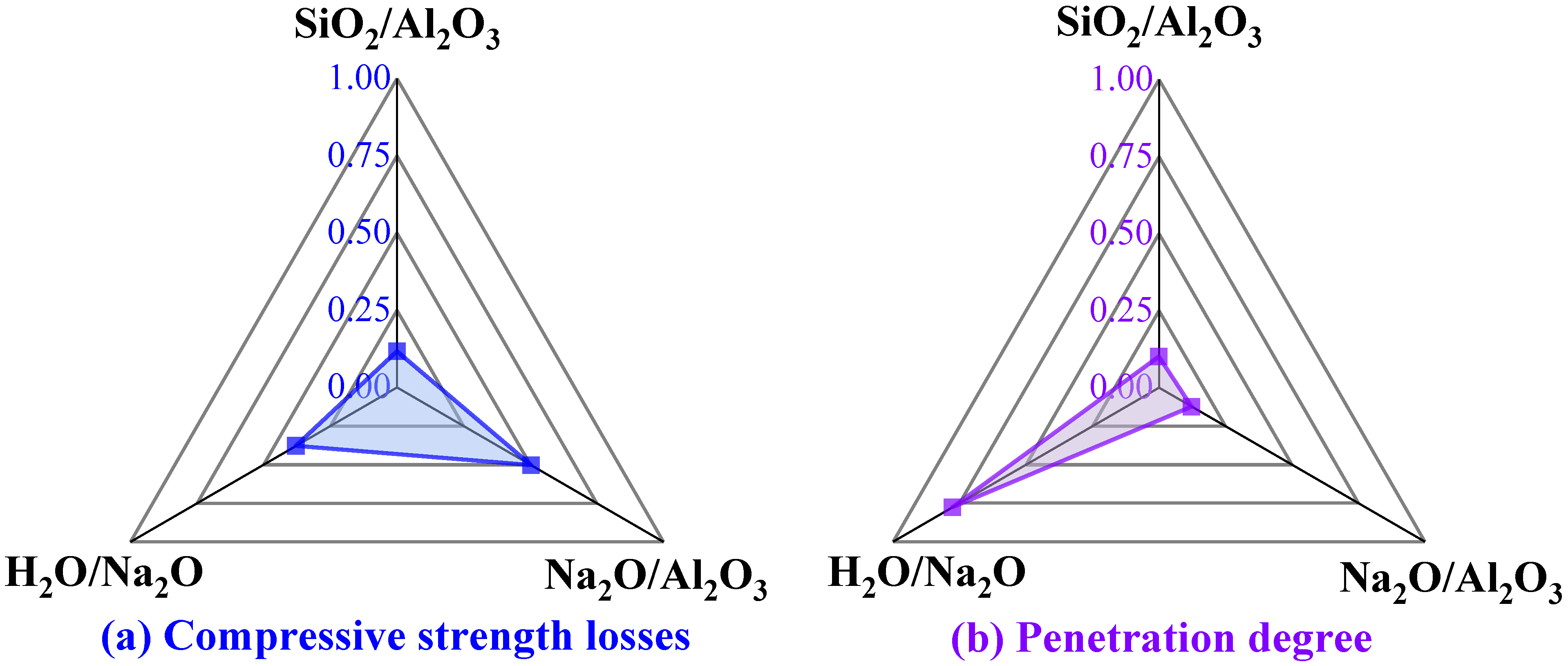

3.9. Sensitivity Analysis

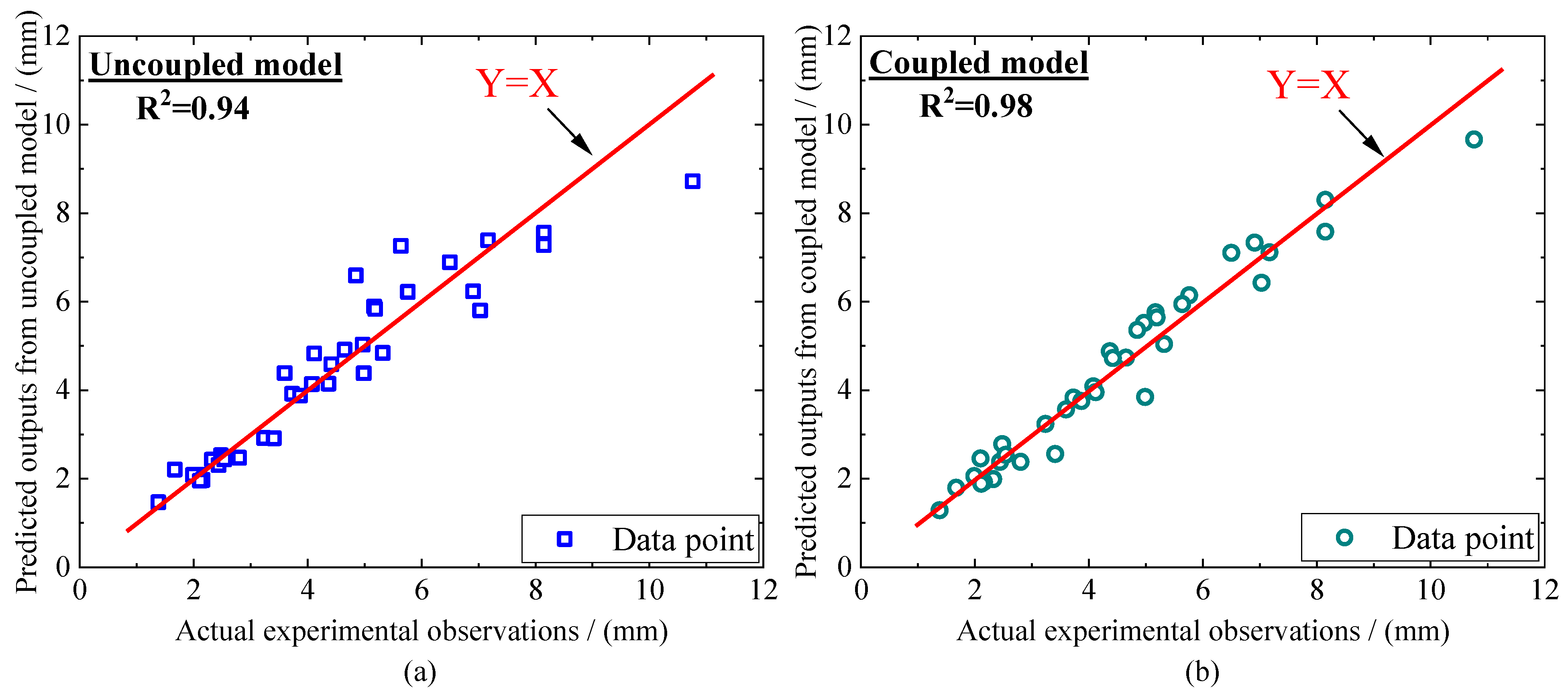

4. Multi-Factor Modelling

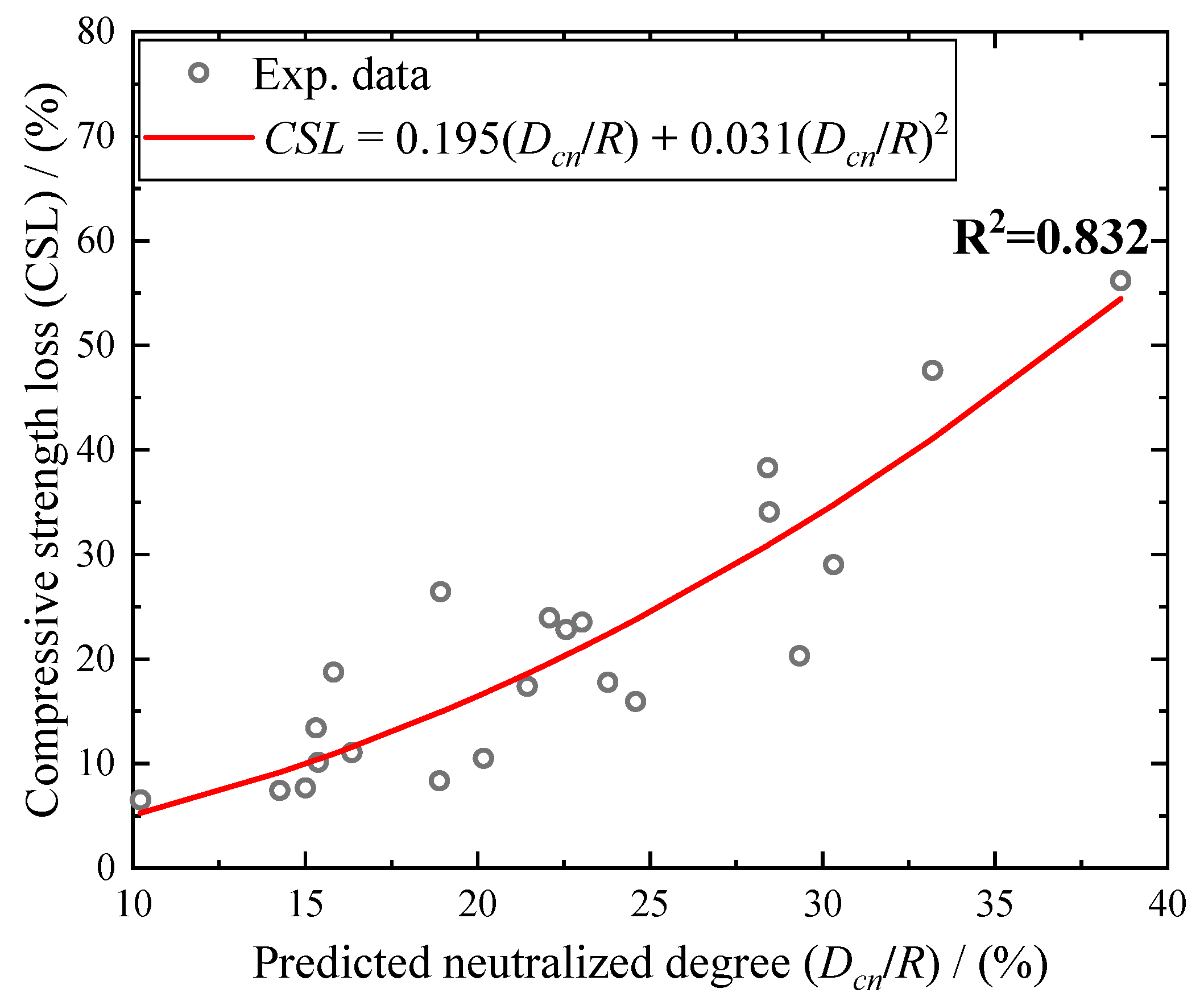

5. Correlation Between Dcn/R and Losses in Compressive Strength

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gartner, E. Industrially interesting approaches to “low-CO2” cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damtoft, J.S.; Lukasik, J.; Herfort, D.; Sorrentino, D.; Gartner, E.M. Sustainable development and climate change initiatives. Cem. Concr. Res. 2008, 38, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, A.M.; Zeedan, S.R. The effect of activator concentration on the residual strength of alkali-activated fly ash pastes subjected to thermal load. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 3098–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLellan, B.C.; Williams, R.P.; Lay, R.V.; Corder, G.D. Costs and carbon emissions for geopolymer pastes in comparison to ordinary portland cement. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar, R. Geopolymer: Cement for low carbon economy. Indian Concr. J. 2014, 88, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Duxson, P.S.W.M.; Mallicoat, S.W.; Lukey, G.C.; Kriven, W.M.; van Deventer, J.S. The effect of alkali and Si/Al ratio on the development of mechanical properties of metakaolin-based geopolymers. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 292, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; He, D.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H. Durability of geopolymers and geopolymer concretes: A review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, D.L.; Sanjayan, J.G.; Sagoe-Crentsil, K. Comparative performance of geopolymers made with metakaolin and fly ash after exposure to elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 37, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.; Li, Z. Composition design and microstructural characterization of calcined kaolin-based geopolymer cement. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 47, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.D.; Scrivener, K.L.; Pratt, P.L. Factors affecting the strength of alkali-activated slag. Cem. Concr. Res. 1994, 24, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T.W.; Chiu, J.P. Fire-resistant geopolymer produced by granulated blast furnace slag. Miner. Eng. 2003, 16, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsa, A.; Kunthawatwong, R.; Naenudon, S.; Sata, V.; Chindaprasirt, P. Natural fiber reinforced high calcium fly ash geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 241, 118143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.S.; Sen, A.; Seshu, D.R. Shear Strength of Fly Ash and GGBS Based Geopolymer Concrete. Advances in Sustainable Construction Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Nie, Q.; Huang, B.; Shu, X.; He, Q. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of geopolymers derived from red mud and fly ashes. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 186, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, C.; Pecina, E.T.; Torres, R.; Gómez, L. Geopolymer synthesis using alkaline activation of natural zeolite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2084–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, A.; Soriano, L.; de Moraes Pinheiro, S.M.; Tashima, M.M.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Payá, J. Design and properties of 100% waste-based ternary alkali-activated mortars: Blast furnace slag, olive-stone biomass ash and rice husk ash. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, Y.M.; Heah, C.Y.; Kamarudin, H. Structure and properties of clay-based geopolymer cements: A review. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 83, 595–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuewangkam, N.; Kidkhunthod, P.; Pinitsoontorn, S. Direct evidence for the mechanism of early-stage geopolymerization process. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J.G. Geopolymer Chemistry and Applications; Institute Geopolymer: Saint-Quentin, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sadat, M.R.; Bringuier, S.; Muralidharan, K.; Runge, K.; Asaduzzaman, A.; Zhang, L. An atomistic characterization of the interplay between composition, structure and mechanical properties of amorphous geopolymer binders. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 434, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboutalebi, S.H.; Ganjkhanlou, Y.; Kamalloo, A.; Nuranian, H. Modeling of Compressive Strength of Metakaolin Based Geopolymers by The Use of Artificial Neural Network Research Note. Int. J. Eng. 2010, 23, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, P.; Sagoe-Crenstil, K.; Sirivivatnanon, V. Kinetics of geopolymerization: Role of Al2O3 and SiO2. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozumder, R.A.; Laskar, A.I. Prediction of unconfined compressive strength of geopolymer stabilized clayey soil using artificial neural network. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 69, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovnaník, P. Effect of curing temperature on the development of hard structure of metakaolin-based geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1176–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, A.; Harmuth, H. Investigation of geopolymer binders with respect to their application for building materials. Ceram. Silikáty 2004, 48, 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto, S.; Minagawa, H.; Hisada, M. Deterioration rate of hardened cement caused by high concentrated mixed acid attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 67, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, T.A.; Kwasny, J.; Sha, W.; Soutsos, M.N. Effect of slag content and activator dosage on the resistance of fly ash geopolymer binders to sulfuric acid attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 111, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutberlet, T.; Hilbig, H.; Beddoe, R.E. Acid attack on hydrated cement—Effect of mineral acids on the degradation process. Cem. Concr. Res. 2015, 74, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafaei, M.; Allahverdi, A.; Dong, P.; Bassim, N. Acid attack on geopolymer cement mortar based on waste-glass powder and calcium aluminate cement at mild concentration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 193, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Zhang, S.; Sheng, D. Performance deterioration of fly ash/slag-based geopolymer composites subjected to coupled cyclic preloading and sulfuric acid attack. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, G.; Liu, W.V. Effects of calcium aluminate cement on the acid resistance of metakaolin-based geopolymer. Adv. Cem. Res. 2021, 33, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewayde, E.; Nehdi, M.; Allouche, E.; Nakhla, G. Effect of geopolymer cement on microstructure, compressive strength and sulphuric acid resistance of concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2006, 58, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Kumala, D. Behaviour of a sustainable concrete in acidic environment. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araghi, H.J.; Nikbin, I.M.; Reskati, S.R.; Rahmani, E.; Allahyari, H. An experimental investigation on the erosion resistance of concrete containing various PET particles percentages against sulfuric acid attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 77, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassuoni, M.T.; Nehdi, M.L. Resistance of self-consolidating concrete to sulfuric acid attack with consecutive pH reduction. Cem. Concr. Res. 2007, 37, 1070–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatina, T.; Sugama, T. Acid resistance of calcium aluminate cement–fly ash F blends. Adv. Cem. Res. 2016, 28, 433–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahverdi, A.; Skvara, F. Sulfuric acid attack on hardened paste of geopolymer cements-Part 1. Mechanism of corrosion at relatively high concentrations. Ceram. Silik. 2005, 49, 225. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.X.; Michaud, P.; Joussein, E.; Rossignol, S. Behavior of metakaolin-based potassium geopolymers in acidic solutions. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2013, 380, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakharev, T. Resistance of geopolymer materials to acid attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thokchom, S.; Ghosh, P.; Ghosh, S. Effect of water absorption, porosity and sorptivity on durability of geopolymer mortars. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2009, 4, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.K.; Lee, H.K. Influence of the slag content on the chloride and sulfuric acid resistances of alkali-activated fly ash/slag paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 72, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, O.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Koenders, E. Effect of Silica Fume on Metakaolin Geopolymers’ Sulfuric Acid Resistance. Materials 2021, 14, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguermouh, K.; Bouzidi, N.; Mahtout, L.; Pérez-Villarejo, L.; Martínez-Cartas, M.L. Effect of acid attack on microstructure and composition of metakaolin-based geopolymers: The role of alkaline activator. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2017, 463, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abora, K.; Beleña, I.; Bernal, S.A.; Dunster, A.; Nixon, P.A.; Provis, J.L.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Winnefeld, F. Durability and testing–Chemical matrix degradation processes. In Alkali Activated Materials; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2014; pp. 177–221. [Google Scholar]

- Teshnizi, E.S.; Karimiazar, J.; Baldovino, J.A. Effect of Acid and Thermo-Mechanical Attacks on Compressive Strength of Geopolymer Mortar with Different Eco-Friendly Materials. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhu, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Ge, W.; Hua, M. Resistance to Sulfuric Acid Corrosion of Geopolymer Concrete Based on Different Binding Materials and Alkali Concentrations. Materials 2021, 14, 7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fan, Z.; Li, X.; Kong, L.; Zhang, L. Characterization and Comparison of Corrosion Layer Microstructure between Cement Mortar and Alkali-Activated Fly Ash/Slag Mortar Exposed to Sulfuric Acid and Acetic Acid. Materials 2022, 15, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, B.; Gao, H.; Lin, Y. Resistance of Soda Residue–Fly Ash Based Geopolymer Mortar to Acid and Sulfate Environments. Materials 2021, 14, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, R.; Ebid, A.A.K.; Huseien, G.F.; Mohammadhosseini, H.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Poi Ngian, S.; Mohamed, A.M. Effects of Sulfate and Sulfuric Acid on Efficiency of Geopolymers as Concrete Repair Materials. Gels 2022, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukrainczyk, N. Simple Model for Alkali Leaching from Geopolymers: Effects of Raw Materials and Acetic Acid Concentration on Apparent Diffusion Coefficient. Materials 2021, 14, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, O.; Ballschmiede, C.; Ukrainczyk, N.; Koenders, E. Evaluation of Sulfuric Acid-Induced Degradation of Potassium Silicate Activated Metakaolin Geopolymers by Semi-Quantitative SEM-EDX Analysis. Materials 2020, 13, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.S. Durability Performance of Geopolymer Concrete: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumaa, N.H.; Ali, I.M.; Nasr, M.S.; Falah, M.W. Strength and microstructural properties of binary and ternary blends in fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Boluk, Y.; Bindiganavile, V. Experimental Characterization and Multi-Factor Modelling to Achieve Desired Flow, Set and Strength of N-A-S-H Geopolymers. Materials 2022, 15, 5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C39/C39M-18; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Chang, C.F.; Chen, J.W. The experimental investigation of concrete carbonation depth. Cem. Concr. Res. 2006, 36, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.A.; Castel, A.; Khan, M.S. Corrosion investigation of fly ash based geopolymer mortar in natural sewer environment and sulphuric acid solution. Corros. Sci. 2020, 168, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räsänen, V.; Penttala, V. The pH measurement of concrete and smoothing mortar using a concrete powder suspension. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C642–13; Standard Test Method for Density, Absorption, and Voids in Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- Garcés, P.; Andrade, M.C.; Sáez, A.; Alonso, M.C. Corrosion of reinforcing steel in neutral and acid solutions simulating the electrolytic environments in the micropores of concrete in the propagation period. Corros. Sci. 2005, 47, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, V.F.; MacKenzie, K.J.; Thaumaturgo, C. Synthesis and characterisation of materials based on inorganic polymers of alumina and silica: Sodium polysialate polymers. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2000, 2, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, A.; Aslani, F.; Panah, N.G. Effects of initial SiO2/Al2O3 molar ratio and slag on fly ash-based ambient cured geopolymer properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 293, 123527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tao, Y.; Zhuang, E.; Cui, X.; Yu, K.; Yu, B.; Boluk, Y.; Bindiganavile, V.; Chen, Z.; Yi, C. Optimal amorphous oxide ratios and multifactor models for binary geopolymers from metakaolin blended with substantial sugarcane bagasse ash. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.P.; Zong, L. Evaluation of relationship between water absorption and durability of concrete materials. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 2014, 650373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, P. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials; McGraw-Hill. Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Rocha, T.; Dias, D.P.; França, F.C.C.; de Salles Guerra, R.R.; de Oliveira, L.R.D.C. Metakaolin-based geopolymer mortars with different alkaline activators (Na+ and K+). Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 178, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchakouté, H.K.; Rüscher, C.H.; Kong, S.; Kamseu, E.; Leonelli, C. Thermal behavior of metakaolin-based geopolymer cements using sodium waterglass from rice husk ash and waste glass as alternative activators. Waste Biomass Valorization 2017, 8, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Provis, J.L.; Bullen, F.; Reid, A.; Zhu, Y. Quantitative kinetic and structural analysis of geopolymers. Part 1. The activation of metakaolin with sodium hydroxide. Thermochim. Acta 2012, 539, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Zhu, G.R.; Ding, S.; Zhang, H.Y.; Xia, F.Y. Mechanical Properties and Mechanisms of Polyacrylamide-Modified Granulated Blast Furnace Slag–Based Geopolymer. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04018347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, W.; Ye, G. Chemical deformation of metakaolin based geopolymer. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 120, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, G.; Mann, D.; Lumsden, K.; Tao, M. Durability of red mud-fly ash based geopolymer and leaching behavior of heavy metals in sulfuric acid solutions and deionized water. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 124, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, P.P.; Luna, K.C.; Garcia, J.I.E. Alkali-activated limestone/metakaolin cements exposed to high temperatures: Structural changes. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.; Chen, Z.; Bindiganavile, V. Crack growth prediction of cement-based systems subjected to two-dimensional sulphate attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 222, 814–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yi, C.; Chen, Z.; Cao, W.; Yin, S.; Huang, H.; Hu, J.; Yu, Q. Relationships between reaction products and carbonation performance of alkali-activated slag with similar pore structure. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 45, 103605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fan, Z.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, D.; Wu, Q. Experiment research on multi-factor model for chloride migration coefficient within concrete. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Changsha, China, 3 February 2021; Volume 676, p. 012108. [Google Scholar]

- Woyciechowski, P.; Woliński, P.; Adamczewski, G. Prediction of carbonation progress in concrete containing calcareous fly ash co-binder. Materials 2019, 12, 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | TiO2 | Fe2O3 | P2O5 | Na2O | K2O | CaO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 53.8% | 43.8% | 0.9% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| SiO2/Al2O3 | Na2O/Al2O3 | H2O/Na2O | Metakaolin (g) | Sodium Silicate (g) | NaOH (g) | Water (g) | Sand (g) | Liquid/Solid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paste | Mortar | ||||||||

| 2.2 | 0.9 | 11 | 500 | 51.5 | 148.7 | 350.6 | 1000 | 1.102 | 0.367 |

| 2.8 | 0.9 | 11 | 500 | 321.0 | 117.8 | 182.2 | 1000 | 1.242 | 0.414 |

| 3.1 | 0.9 | 11 | 500 | 455.7 | 102.3 | 98 | 1000 | 1.312 | 0.437 |

| 3.4 | 0.9 | 11 | 500 | 590.4 | 86.9 | 13.8 | 1000 | 1.382 | 0.461 |

| 3.7 | 0.9 | 11 | 500 | 702.7 | 74.0 | −56.4 | 1000 | 1.441 | 0.480 |

| 3.1 | 0.8 | 11 | 500 | 455.7 | 85.1 | 55.4 | 1000 | 1.193 | 0.398 |

| 3.1 | 0.9 | 11 | 500 | 455.7 | 102.3 | 98.0 | 1000 | 1.312 | 0.437 |

| 3.1 | 1.1 | 11 | 500 | 455.7 | 136.7 | 183.0 | 1000 | 1.551 | 0.517 |

| 3.1 | 1.3 | 11 | 500 | 455.7 | 171.1 | 268.1 | 1000 | 1.790 | 0.597 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 8 | 500 | 455.7 | 119.5 | 24.5 | 1000 | 1.199 | 0.400 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 10 | 500 | 455.7 | 119.5 | 101.8 | 1000 | 1.354 | 0.451 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 12 | 500 | 455.7 | 119.5 | 179.2 | 1000 | 1.509 | 0.503 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 14 | 500 | 455.7 | 119.5 | 256.5 | 1000 | 1.663 | 0.554 |

| Precursors | Properties | Optimal Value/Range | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metakaolin | Acid resistance | SiO2/Al2O3 = 3.1~3.4 Na2O/Al2O3 = 0.8~0.9 H2O/Na2O = 8~10 | Present study |

| Slag | Acid resistance | KOH = 8 M | [45] |

| Fly ash | Acid resistance | NaOH = 12 M | [46] |

| Metakaolin | Compressive strength | SiO2/Al2O3 = 3.6~3.8 Na2O/Al2O3 = 1.0~1.2 H2O/Na2O = 10~11 | [21] |

| Metakaolin | Workability, setting, and compressive strength | SiO2/Al2O3 = 2.8~3.6 Na2O/Al2O3 = 0.75~1.0 H2O/Na2O = 9~10 | [54] |

| Metakaolin | Compressive strength | Si/Al = 1.65 Na/Al = 0.83 | [61] |

| Fly ash | Compressive strength | SiO2/Al2O3 = 3.37 | [62] |

| Metakaolin and Sugarcane bagasse ash | Compressive and flexural strength | SiO2/Al2O3 = 3.1~3.4 Na2O/Al2O3 = 0.8~0.9 H2O/Na2O = 8~10 | [63] |

| Mixture Designations | O (%) | Na (%) | Al (%) | Si (%) | S (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2/Al2O3 = 2.2 | un-exposed (exposed) | 49.42 (43.23) | 13.98 (2.72) | 17.12 (26.83) | 19.48 (21.81) | 0 (5.21) |

| SiO2/Al2O3 = 3.4 | un-exposed (exposed) | 46.96 (44.54) | 11.51 (11.30) | 14.81 (15.49) | 26.71 (28.62) | 0 (0.044) |

| SiO2/Al2O3 = 3.7 | un-exposed (exposed) | 48.39 (40.56) | 12.45 (11.24) | 13.06 (16.07) | 26.10 (31.99) | 0 (0.14) |

| Na2O/Al2O3 = 0.8 | un-exposed (exposed) | 47.22 (40.19) | 12.28 (12.44) | 15.40 (16.71) | 25.09 (30.28) | 0 (0.39) |

| Na2O/Al2O3 = 0.9 | un-exposed (exposed) | 50.00 (48.40) | 10.31 (10.03) | 14.44 (14.43) | 25.24 (26.45) | 0 (0.69) |

| Na2O/Al2O3 = 1.3 | un-exposed (exposed) | 49.62 (39.22) | 18.38 (13.31) | 11.88 (16.48) | 20.11 (27.88) | 0 (3.11) |

| H2O/Na2O = 8 | un-exposed (exposed) | 45.68 (42.54) | 14.28 (12.53) | 14.47 (16.89) | 25.57 (27.91) | 0 (0.13) |

| H2O/Na2O = 10 | un-exposed (exposed) | 49.20 (45.61) | 13.47 (11.72) | 13.07 (15.53) | 24.25 (26.72) | 0 (0.42) |

| H2O/Na2O = 14 | un-exposed (exposed) | 47.81 (42.61) | 12.51 (8.70) | 14.75 (17.90) | 24.93 (30.15) | 0 (0.63) |

| SiO2/Al2O3 | Na2O/Al2O3 | H2O/Na2O | L/S | Exposure Time (yrs) | Tested Depth (mm) | Predicted Depth, Dn (mm) | Predicted Depth, Dcn (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.2 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.102 | 0.077 | 2.80 | 2.47 | 2.38 |

| 2.8 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.242 | 0.077 | 2.10 | 2.09 | 2.45 |

| 3.1 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.312 | 0.077 | 1.99 | 2.08 | 2.06 |

| 3.4 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.382 | 0.077 | 1.67 | 2.20 | 1.79 |

| 3.7 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.441 | 0.077 | 2.32 | 2.43 | 1.99 |

| 3.1 | 0.8 | 11 | 1.193 | 0.077 | 2.16 | 1.97 | 1.93 |

| 3.1 | 1.1 | 11 | 1.551 | 0.077 | 2.44 | 2.31 | 2.38 |

| 3.1 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.790 | 0.077 | 2.48 | 2.53 | 2.78 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 8 | 1.199 | 0.077 | 1.38 | 1.47 | 1.29 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 10 | 1.354 | 0.077 | 2.11 | 1.95 | 1.89 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 12 | 1.509 | 0.077 | 2.54 | 2.44 | 2.54 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 14 | 1.663 | 0.077 | 3.24 | 2.92 | 3.23 |

| 2.2 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.102 | 0.153 | 4.65 | 4.91 | 4.73 |

| 2.8 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.242 | 0.153 | 4.37 | 4.14 | 4.88 |

| 3.1 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.312 | 0.153 | 4.08 | 4.14 | 4.09 |

| 3.4 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.382 | 0.153 | 3.60 | 4.38 | 3.57 |

| 3.7 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.441 | 0.153 | 4.12 | 4.83 | 3.95 |

| 3.1 | 0.8 | 11 | 1.193 | 0.153 | 3.73 | 3.92 | 3.83 |

| 3.1 | 1.1 | 11 | 1.551 | 0.153 | 4.42 | 4.58 | 4.72 |

| 3.1 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.790 | 0.153 | 4.97 | 5.03 | 5.52 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 8 | 1.199 | 0.153 | 3.41 | 2.91 | 2.56 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 10 | 1.354 | 0.153 | 3.87 | 3.88 | 3.75 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 12 | 1.509 | 0.153 | 5.32 | 4.84 | 5.04 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 14 | 1.663 | 0.153 | 7.03 | 5.80 | 6.43 |

| 2.2 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.102 | 0.230 | 7.17 | 7.39 | 7.11 |

| 2.8 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.242 | 0.230 | 6.91 | 6.23 | 7.33 |

| 3.1 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.312 | 0.230 | 5.76 | 6.22 | 6.15 |

| 3.4 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.382 | 0.230 | 4.85 | 6.59 | 5.36 |

| 3.7 | 0.9 | 11 | 1.441 | 0.230 | 5.64 | 7.26 | 5.94 |

| 3.1 | 0.8 | 11 | 1.193 | 0.230 | 5.17 | 5.89 | 5.76 |

| 3.1 | 1.1 | 11 | 1.551 | 0.230 | 6.50 | 6.89 | 7.10 |

| 3.1 | 1.3 | 11 | 1.790 | 0.230 | 8.15 | 7.56 | 8.30 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 8 | 1.199 | 0.230 | 4.99 | 4.38 | 3.84 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 10 | 1.354 | 0.230 | 5.19 | 5.83 | 5.64 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 12 | 1.509 | 0.230 | 8.15 | 7.28 | 7.58 |

| 3.1 | 1.0 | 14 | 1.663 | 0.230 | 10.76 | 8.72 | 9.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yi, C.; Boluk, Y.; Bindiganavile, V. Refining Oxide Ratios in N-A-S-H Geopolymers for Optimal Resistance to Sulphuric Acid Attack. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010044

Yi C, Boluk Y, Bindiganavile V. Refining Oxide Ratios in N-A-S-H Geopolymers for Optimal Resistance to Sulphuric Acid Attack. Journal of Composites Science. 2025; 9(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleYi, Chaofan, Yaman Boluk, and Vivek Bindiganavile. 2025. "Refining Oxide Ratios in N-A-S-H Geopolymers for Optimal Resistance to Sulphuric Acid Attack" Journal of Composites Science 9, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010044

APA StyleYi, C., Boluk, Y., & Bindiganavile, V. (2025). Refining Oxide Ratios in N-A-S-H Geopolymers for Optimal Resistance to Sulphuric Acid Attack. Journal of Composites Science, 9(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs9010044