Abstract

The energy consumed by building is more than the energy consumed by transportation. The windows are found to be a weak thermal link through which heat is gained in the summer and lost in the winter, consequently increasing the building’s energy consumption. This study focuses on the impact of window to wall area ratio (WWR) and orientation of the building on energy consumption under typical Karachi climate conditions. The energy analysis is conducted using Green Building Studio (GBS). The space cooling consumption is observed considerably higher than space heating consumption. It is found that WWR and orientation have a significant influence on the heating and cooling demands of the building. Large openings have been shown to have a negative impact on energy consumption. The north-south axis orientation is determined as the most optimal orientation of the building in this specific climate.

1. Introduction

Buildings utilise 40% of the world’s energy, which is more than the energy consumed by transportation. This percentage will surely climb, as it is the greatest wave of urban expansion. Currently, more than half of the population lives in cities, and it is estimated that by 2060s two-thirds of the global population will start living in urban areas. As a result, there are more people, more buildings, and more consumption, which leads to greater emission [1].

The Facade opening is the most vulnerable portion of the building envelope. The window, in particular, is the weakest thermal link in buildings envelop. [2]. The main source of heat gain is solar gain coming through a window, which raises the inside temperature above the external air temperature [3]. According to Halder [4], windows are a poor insulator and hence account for 25–30% of a building’s heat loss. As a result, windows configuration has a significant influence on a building’s overall energy usage.

Generally, architects preoccupied with aesthetic and architectural aspects during the design process, whereas sustainability aspects and energy efficiency are often overlooked [5]. The effect of windows on energy efficiency of buildings is substantial; therefore, this research is conducted to investigate the impact of windows configuration on the energy consumption of residential building in Karachi. Three criteria determine the amount of heat gain and loss through windows: the window to wall area ratio (WWR), the orientation of the window, and the thermal properties of the glass material; however, this study is limited to the first two parameters only.

2. Methodology

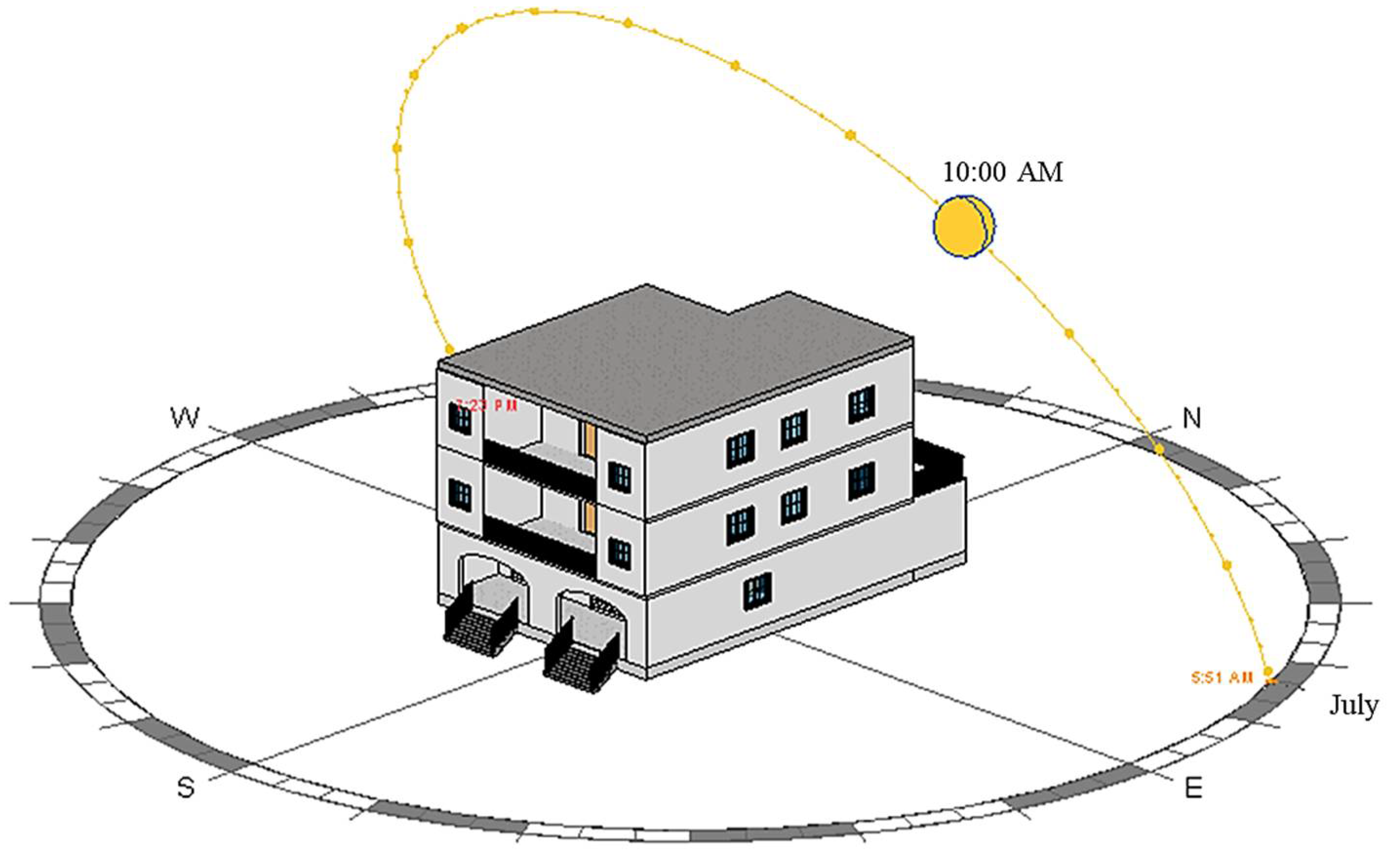

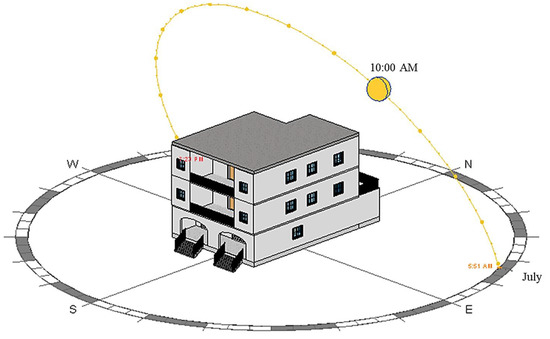

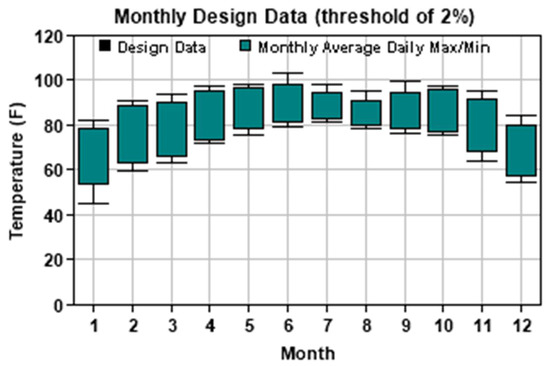

A BIM model of a commercial-residential building in Karachi (24°57′17.5″ N, 67°08′35.1″ E) is developed using Autodesk Revit, as shown in Figure 1. The defined window in the model is 1/8 in Pilkington single glazing with U value 3.69 W/(m2-K). The energy model is created and exported to Autodesk Green Building Studio (GBS) for analysis. GBS is a cloud-based application that allows you to conduct building performance simulations early in the design phase to increase energy efficiency and achieve carbon neutrality. The weather data used in the analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

3D intelligent model of Building located in Karachi.

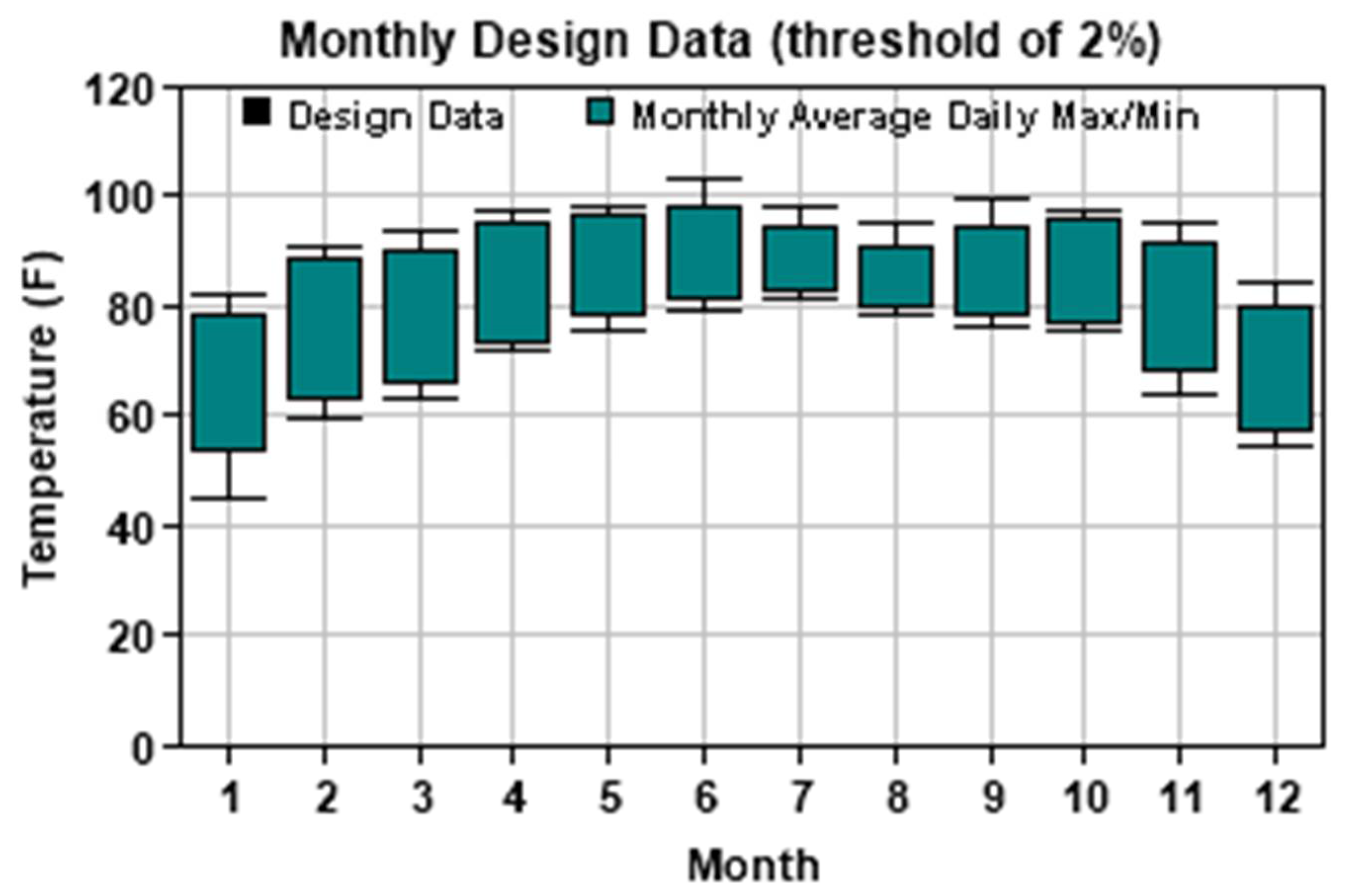

Figure 2.

Monthly design data for Karachi (Source: GBS database).

Design alternatives are defined and analyzed. Four (04) different WWR (15%, 40%, 65%, 80%) are defined with respect to different orientations of the building as given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Window Wall Ratio (WWR) with respect to orientation.

3. Results and Discussion

The analyses’ findings are tabulated in Table 2. It can be noticed that space cooling consumption is considerably greater than the space heating consumption. The worst-case scenario for space heating consumption is when WWR is 80 percent in north direction, whereas the ideal scenario is when WWR is 80 percent in west orientation. The worst-case scenario for space cooling consumption is when WWR is 80 percent in west direction, whereas the ideal scenario is when WWR is 15 percent in north direction.

Table 2.

Space energy consumption.

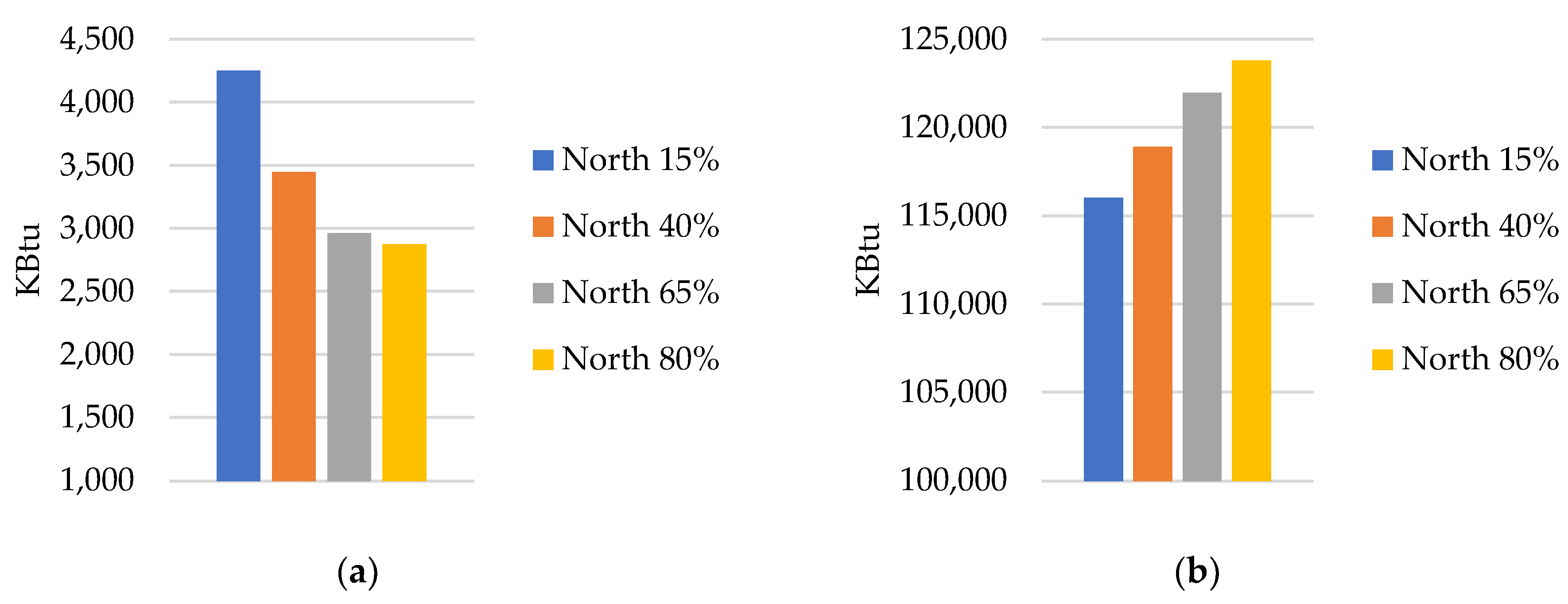

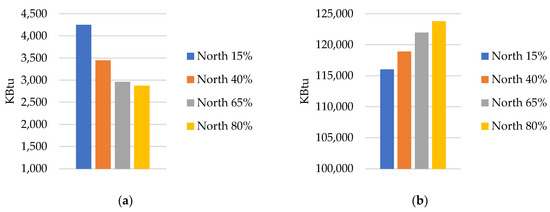

With an increase in WWR, the heating demand for the building facing north decreases while the cooling load increases, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Space (a) heating and (b) cooling consumption in north facing orientation.

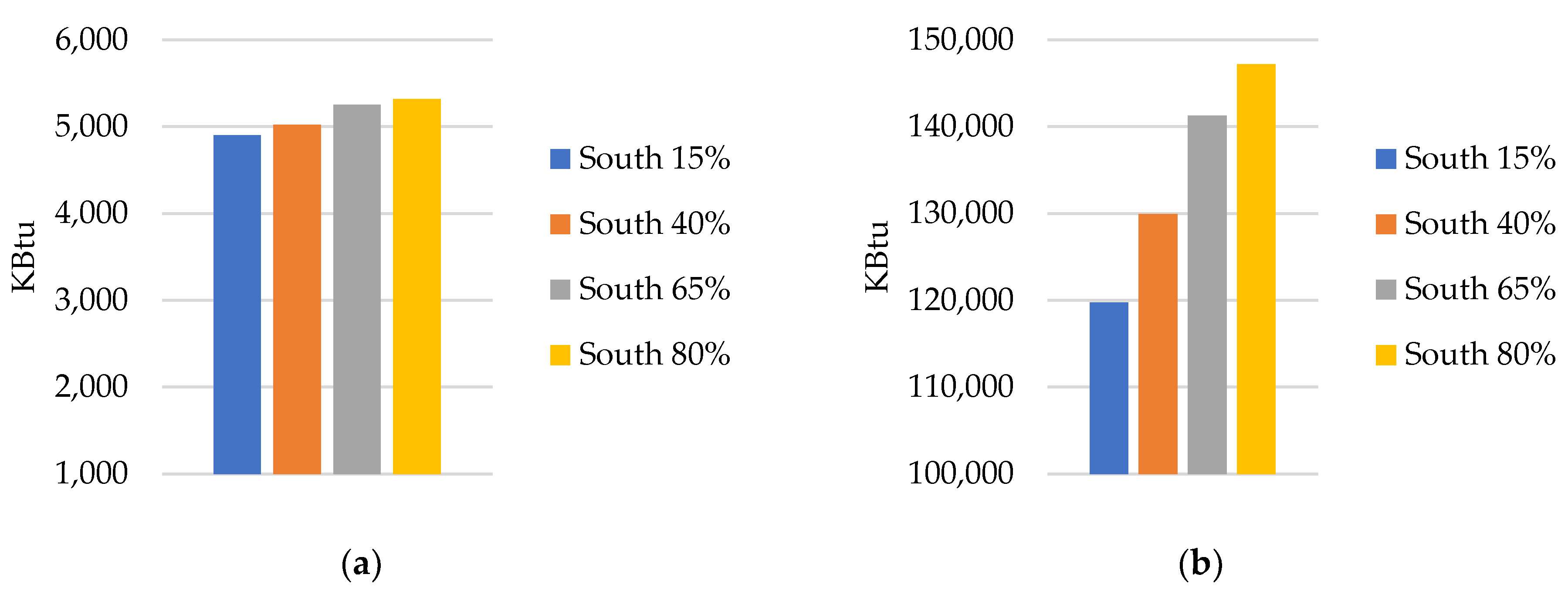

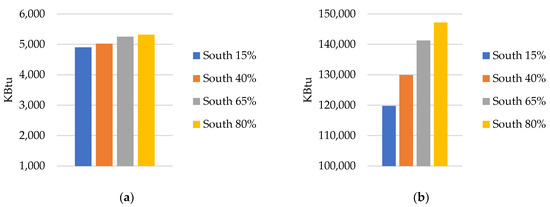

With an increase in WWR, there is a modest increase in heating load but a considerable increase in cooling load for the building facing south, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Space (a) heating and (b) cooling consumption in south facing orientation.

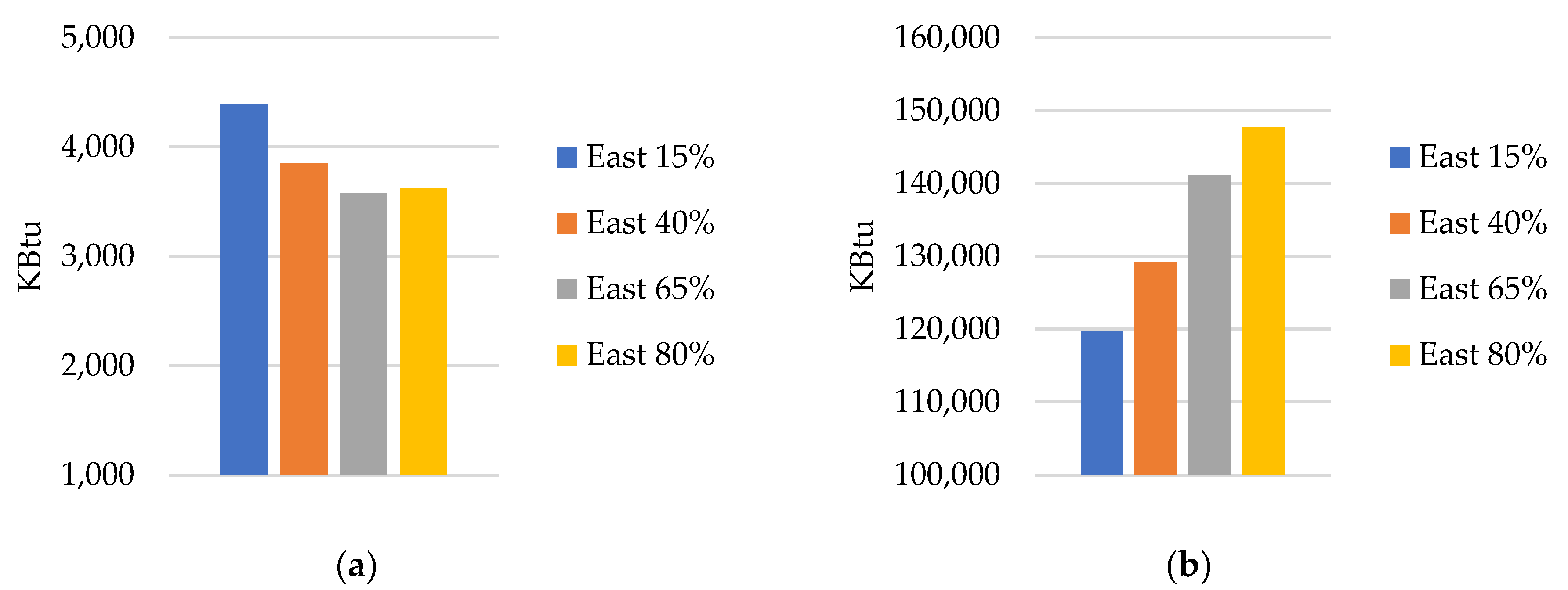

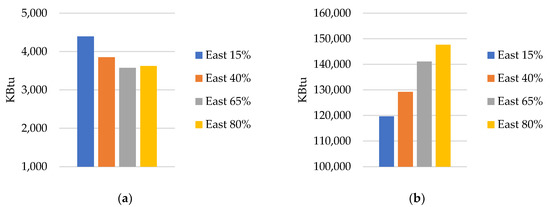

With an increase in WWR, the heating demand for the building facing east decreases while the cooling load increases, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Space (a) heating and (b) cooling consumption in east facing orientation.

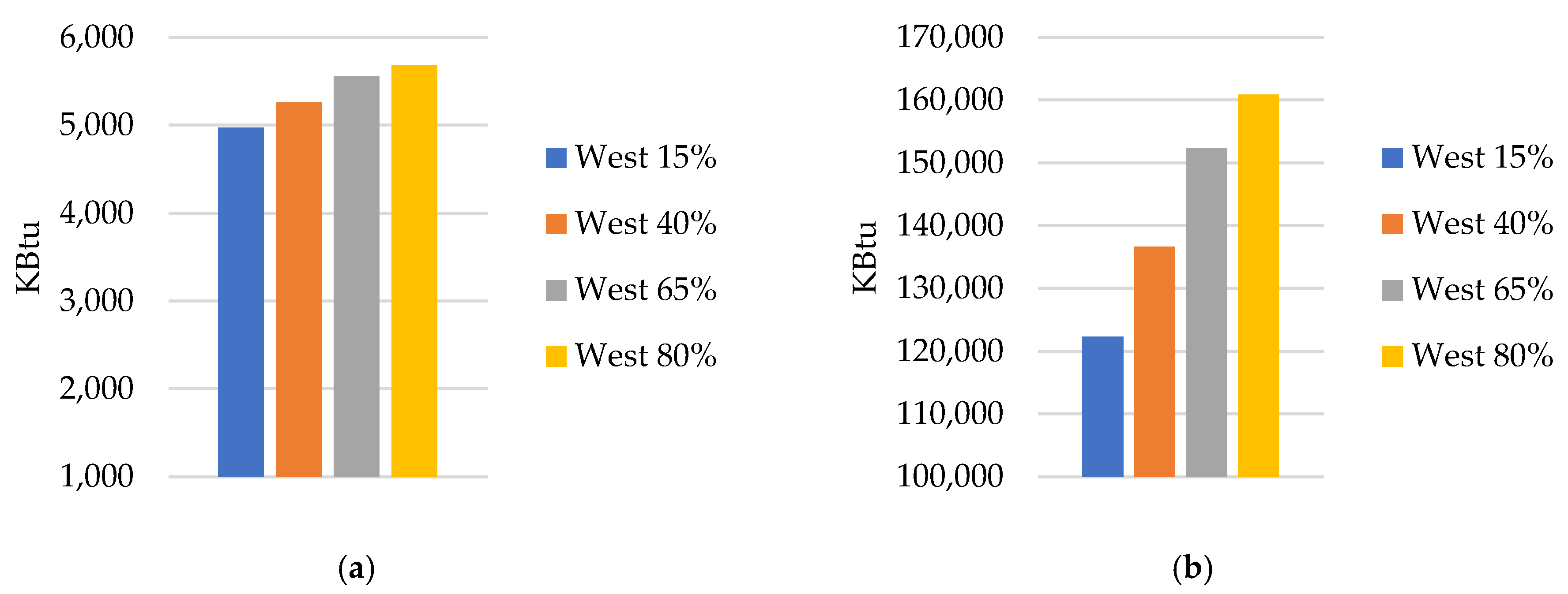

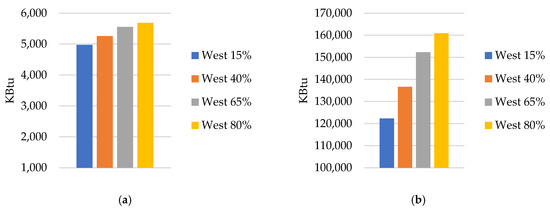

With an increase in WWR, the heating demand for the building facing west increases modestly while the cooling load increases considerably, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Space (a) heating and (b) cooling consumption in west facing orientation.

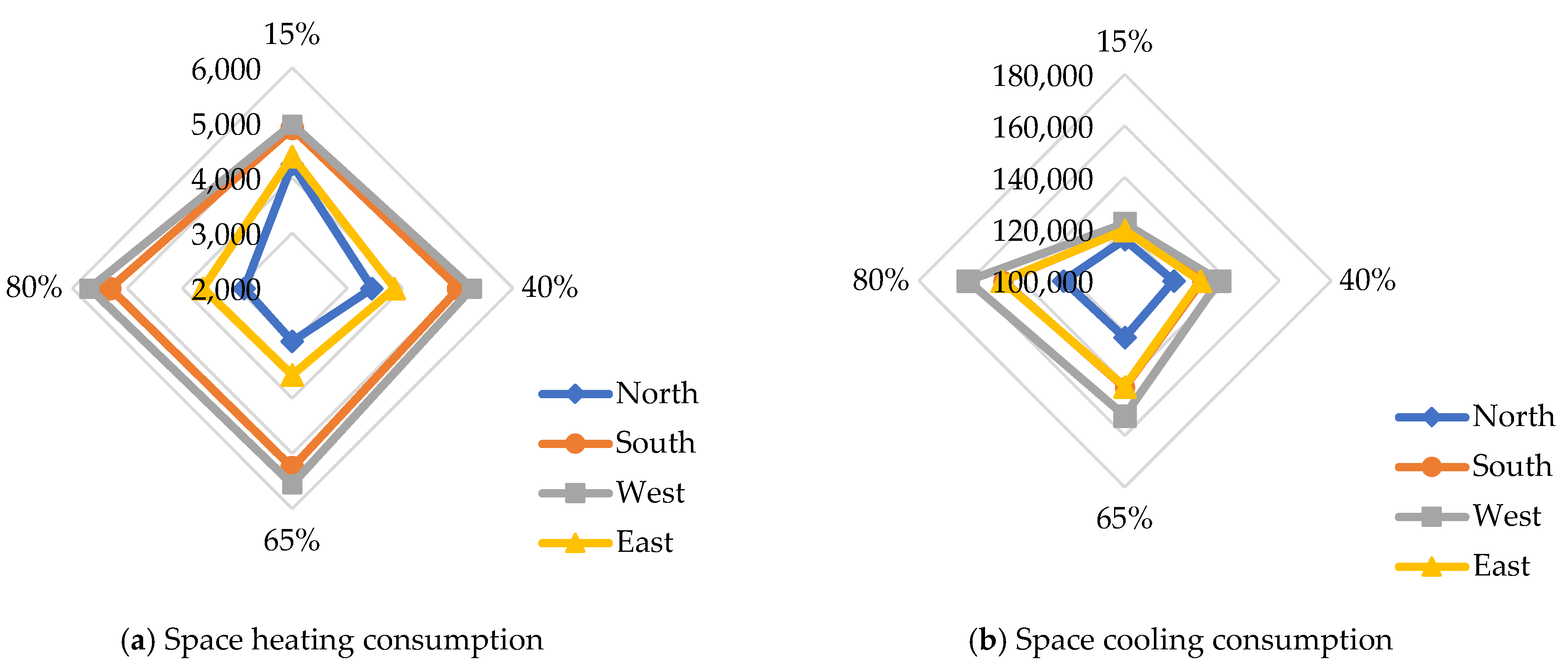

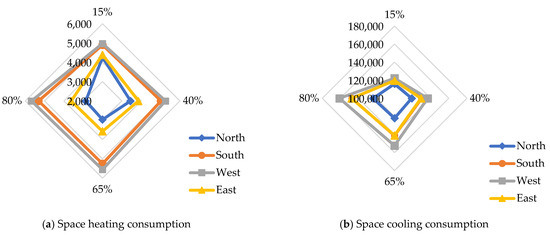

Figure 7 depicts multivariate data, WWR in relation to the building’s orientation, using radar plots. In terms of energy consumption, it indicates that the optimal building orientation in this specific region is north direction, whereas the worst is west orientation.

Figure 7.

Space (a) heating and (b) cooling consumption according to WWR and orientation.

4. Conclusions

Based on the study, the following conclusions and outcomes have been drawn:

- WWR and orientation have a significant influence on the overall energy demands for heating and cooling in buildings under typical Karachi climatic conditions. It is found large openings increase the overall energy consumption of the building.

- The space cooling consumption is found considerably higher than the space heating consumption.

- The best orientation of the building in this specific region is North while the worst orientation is West in terms of energy consumption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft preparation, M.S.I.; Methodology, Validation, Writing—review and editing, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no outside funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Architecture 2030. (n.d.) The 2030 Challenge. Available online: https://architecture2030.org/2030_challenges/2030-challenge/ (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Djamel, Z.; Noureddine, Z. The Impact of Window Configuration on the Overall Building Energy Consumption under Specific Climate Conditions. Energy Procedia 2017, 115, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, V. Upgrading a Broad Area Illuminating Integrating Sphere and Solar Transmittance Measurement of a Sheer Blind. Master’s Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koeigsberger, O.H. Manual of Tropical Housing and Building: Part One: Climatic Design; Longman: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ryghaug, M.; Sorensen, K.H. How energy efficiency fails in the building industry. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).