Non-Native Marine Macroalgae of the Azores: An Updated Inventory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Species Invetory

3.2. Species Composition

- Five brown algae (5% of the Ochrophyta reported in the Azores);

- Thirty-three red algae (9% of the Rhodophyta reported in the Azores);

- Four green algae (5% of the Chlorophyta reported in the Azores);

- Therefore, 12% of the non-native macroalgal species belong to the Ochrophyta, 79% to the Rhodophyta, and 9% to the Chlorophyta.

- Four of the five (80%) Ochrophyta species belong to the Ectocarpales, characterized by isomorphic gametophyte and sporophyte composed of uniseriate, branched, or unbranched filaments [28];

- 25 of the 33 (76%) Rhodophyta species belong to the Ceramiales, an order characterized by isomorphic gametophyte and sporophyte of widely varying morphology of uniaxial structure [28];

- All four (100%) Chlorophyta species belong to the Bryopsidales, an order characterized by simple to complex siphonous thalli [28].

3.3. Non-Native Species Distribution

3.3.1. General Distribution

- Formigas, São Miguel, Santa Maria, Terceira, Graciosa, and Pico present similar percentage of NNS (8.44–9.74%);

- The most isolated islands in the Western Group (Flores and Corvo) present lower percentages of NNS (6.25% and 4.25%, respectively);

- The islands with the most used marina for transatlantic recreational sailing (São Jorge and Faial) present higher percentages of NNS (12.90% and 16.87%, respectively).

3.3.2. Specific Distribution (Maps in Supplementary Material File S2)

- Antithamnionella elegans, Antithamnionella ternifolia, Corynomorpha prismatica, Grallatoria reptans, and Gymnophycus hapsiphorus in São Miguel;

- Acrothamnion preissii, Halimeda incrassata, and Scinaia acuta in Santa Maria;

- Hypoglossum heterocystideum in Graciosa;

- Antithamnion densum in Pico;

- Antithamnion nipponicum and Caulerpa webbiana in Faial.

- Antithamnion hubbsii, Lophocladia trichoclados, and Scytosiphon dotyi in the Eastern Group;

- Aglaothamnion cordatum, Laurencia chondrioides, and Laurencia minuta in the Central Group;

- No species is exclusively found in the Western Group.

3.4. Species Introduction

3.4.1. Native Range

- 7% from the Pacific Ocean, 7% from the Western Pacific, and 17% from the Northwestern Pacific;

- 31% from the Indo-Pacific;

- 17% from the Indian Ocean;

- 2% from the Northeastern Atlantic, and 19% from the Western Atlantic.

3.4.2. Introduction Vectors

- 68% from shipping, i.e., through hull fouling or ballast water;

- 5% due to escape from confinement, i.e., from aquarium or aquaculture;

- 27% unknown.

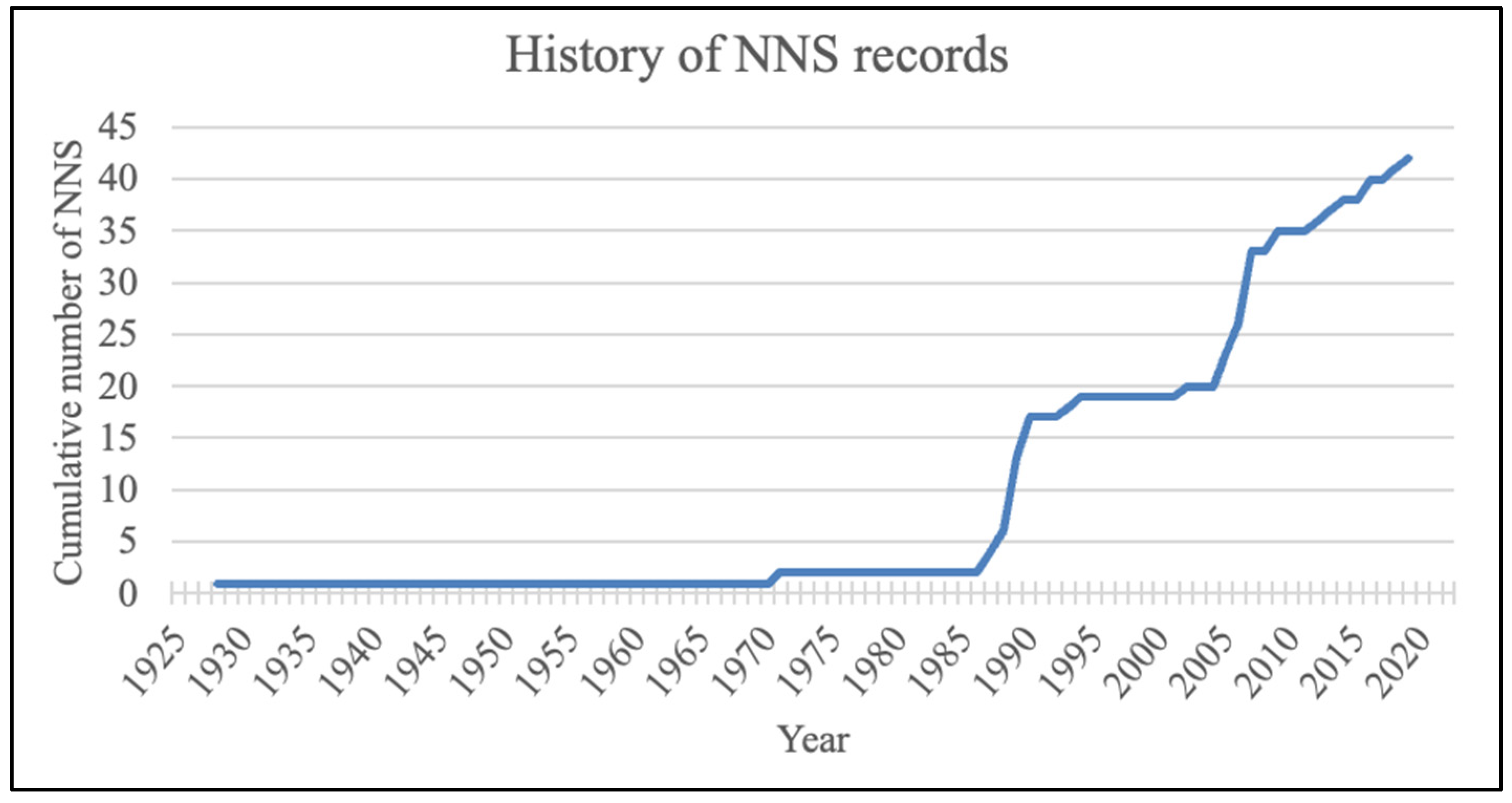

3.4.3. History of First Reports

- First NNS reported in 1928;

- First surge of NNS reports in the late 1980s;

- Second surge of NNS reports in the mid-2000s;

- Steady increase in the number of NNS reports in the last 15 years.

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN. The Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 and the Aichi Biodiversity Targets; Document UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/X/2; Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Nagoya, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Geng, Y.; Shi, H.; Wu, C.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Xing, R. Biological Mechanisms of Invasive Algae and Meta-Analysis of Ecological Impacts on Local Communities of Marine Organisms. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 146, 109763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, Q.J.; Adriaens, T.; Desmet, P.; Simpson, A.; De Wever, A.; Bazos, I.; Cardoso, A.C.; Charles, L.; Christopoulou, A.; Gazda, A.; et al. Seven Recommendations to Make Your Invasive Alien Species Data More Useful. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Cisneros, K.; Tittley, I.; Terra, M.R.; Nogueira, E.M.; Neto, A.I. The Marine Algal (Seaweed) Flora of the Azores: 4, Further Additions. Arquipel. Life Mar. Sci. 2012, 29, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Meirelles, M.; Carvalho, F.; Porteiro, J.; Henriques, D.; Navarro, P.; Vasconcelos, H. Climate Change and Impact on Renewable Energies in the Azores Strategic Visions for Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito de Azevedo, E.; Rodrigues, M.; Fernandes, J. O Clima Dos Açores. In Atlas Básico dos Açores; Forjaz, V.H., Ed.; Observatório Vulcanológico e Geotérmico dos Açores: Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 2004; pp. 25–48. ISBN 9729746648. [Google Scholar]

- Tittley, I.; Neto, A.I. The Marine Algal (Seaweed) Flora of the Azores: Additions and Amendments. Bot. Mar. 2005, 48, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.; Romeiras, M.; Silva, L.; Cordeiro, R.; Madeira, P.; González, J.A.; Wirtz, P.; Falcón, J.M.; Brito, A.; Floeter, S.R.; et al. Restructuring of the ‘Macaronesia’ Biogeographic Unit: A Marine Multi-Taxon Biogeographical Approach. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardigos, F.; Tempera, F.; Ávila, S.; Gonçalves, J.; Colaço, A.; Santos, R.S. Non-Indigenous Marine Species of the Azores. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2006, 60, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micael, J.; Parente, M.I.; Costa, A.C. Tracking Macroalgae Introductions in North Atlantic Oceanic Islands. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2014, 68, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, N.; Carlton, J.T.; Costa, A.C.; Marques, C.S.; Hewitt, C.L.; Cacabelos, E.; Lopes, E.; Gizzi, F.; Gestoso, I.; Monteiro, J.G.; et al. Diversity and Patterns of Marine Non-native Species in the Archipelagos of Macaronesia. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 667–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, M.I.; Gabriel, D.; Micael, J.; Botelho, A.Z.; Ballesteros, E.; Milla, D.; dos Santos, R.; Costa, A.C. First Report of the Invasive Macroalga Acrothamnion preissii (Rhodophyta, Ceramiales) in the Atlantic Ocean. Bot. Mar. 2018, 61, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos, E.; Faria, J.; Martins, G.M.; Mir, C.; Parente, M.I.; Gabriel, D.; Sánchez, R.; Altamirano, M.; Costa, A.C.; Prud’homme van Reine, W.; et al. First Record of Caulerpa prolifera in the Azores (NE Atlantic). Bot. Mar. 2019, 62, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Moreu, I.; Martins, G.M.; Neto, A.I.; Cacabelos, E. Arrival and Proliferation of the Invasive Seaweed Rugulopteryx okamurae in NE Atlantic Islands. Bot. Mar. 2022, 65, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittley, I.; Neto, A.I. The Marine Algal Flora of the Azores: Island Isolation or Atlantic Stepping-Stones? Occas. Publ. Ir. Biogeogr. Soc. 2006, 9, 40–54. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, A.I.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Azevedo, J.M.N.; Resendes, R.; Álvaro, N.; Neto, R.M.A.; Moreu, I. Marine Algal Flora of Formigas Islets, Azores. Biodivers. Data J. 2020, 8, e57510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.I.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Resendes, R.; Neto, R.M.A.; Moreu, I. Marine Algal (Seaweed) Flora of Faial Island, Azores. 2020. Sampling Event Dataset. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/jnkr5k (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Neto, A.I.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Resendes, R.; Neto, R.M.A.; Moreu, I. Marine Algal (Seaweed) Flora of São Jorge Island, Azores. 2020. Available online: https://doi.org/10.15468/93phf6 (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Neto, A.I.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Álvaro, N.; Resendes, R.; Neto, R.M.A.; Moreu, I. Marine Algal (Seaweed) Flora of Terceira Island, Azores. Biodivers. Data J. 2020, 8, e57462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neto, A.I.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Álvaro, N.; Resendes, R.; Neto, R.M.A.; Tittley, I.; Moreu, I. Marine Algal Flora of Pico Island, Azores. Biodivers. Data J. 2020, 8, e57461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.I.; Parente, M.I.; Botelho, A.Z.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Resendes, R.; Afonso, P.; Álvaro, N.V.; Milla-Figueras, D.; Neto, R.M.A.; Tittley, I.; et al. Marine Algal Flora of Graciosa Island, Azores. Biodivers. Data J. 2020, 8, e57201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.I.; Parente, M.; Cacabelos, E.; Costa, A.; Botelho, A.; Ballesteros, E.; Monteiro, S.; Resendes, R.; Afonso, P.; Prestes, A.; et al. Marine Algal Flora of Santa Maria Island, Azores. Biodivers. Data J. 2021, 9, e61909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.I.; Parente, M.; Tittley, I.; Fletcher, R.; Farnham, W.; Costa, A.; Botelho, A.; Monteiro, S.; Resendes, R.; Afonso, P.; et al. Marine Algal Flora of Flores and Corvo Islands, Azores. Biodivers. Data J. 2021, 9, e60929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.I.; Moreu, I.; Rosas Alquicira, E.; León-Cisneros, K.; Cacabelos, E.; Botelho, A.; Micael, J.; Costa, A.; Neto, R.; Azevedo, J.; et al. Marine Algal Flora of São Miguel Island, Azores. Biodivers. Data J. 2021, 9, e64969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, R.; Ferreira, A.; Micael, J.; Gil-Rodríguez, M.C.; Machín, M.; Costa, A.C.; Gabriel, D.; Costa, F.O.; Parente, M.I. Genetic Characterization of the Red Algae Asparagopsis armata and Asparagopsis taxiformis (Bonnemaisoniaceae) from the Azores. Genome 2015, 58, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.I.; Cacabelos, E.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Díaz-Tapia, P.; Moreu, I. New Records of Marine Macroalgae for the Azores. Bot. Mar. 2022, 65, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz-Pinto, F.; Torrontegi, O.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Álvaro, N.V.; Neto, A.I.; Martins, G.M. Invasion Success and Development of Benthic Assemblages: Effect of Timing, Duration of Submersion and Substrate Type. Mar. Environ. Res. 2014, 94, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-Wide Electronic Publication. National University of Ireland, Galway. 2023. Available online: http://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Tittley, I.; Neto, A.I.; Parente, M.I. The Marine Algal (Seaweed) Flora of the Azores: Additions and Amendments 3. Bot. Mar. 2009, 52, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, A.Z.; Dionísio, M.A.; Cunha, A.; Monteiro, S.; Geraldes, D.; Hipólito, C.; Parente, M.; Angélico, M.M.; Costa, A.C. Contributo Para a Inventariação da Biodiversidade Marinha da ilha de Santa Maria; Relatórios e Comunicações do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade dos Açores 36; Universidade dos Açores: Ponta Delgada, Protugal, 2009; pp. 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wallenstein, F. Rocky Shore Macroalgae Communities of the Azores (Portugal) and the British Isles: A Comparison for the Development of Ecological Quality Assessment Tool. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, A.I.d.M.A. Studies on Algal Communities of São Miguel, Azores. Ph.D. Thesis, University of the Azores, Ponta Delgada, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Parente, M.I.; Neto, A.I.; Fletcher, R.L. Morphology and Life History Studies of Endarachne binghamiae (Scytosiphonaceae, Phaeophyta) from the Azores. Aquat. Bot. 2003, 76, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittley, I.; Neto, A.I. “Expedition Azores 1989”: Benthic Marine Algae (Seaweeds) Recorded from Faial and Pico. Archipélago. Life Mar. Sci. 1994, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Verlaque, M.; Ruitton, S.; Mineur, F.; Boudouresque, C.F. CIESM Atlas of Exotic Macrophytes in the Mediterranean Sea. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer. Médit. 2007, 38, 14. [Google Scholar]

- ICES. Working Group on Introductions and Transfers of Marine Organisms (WGITMO); ICES Scientific Reports; ICES: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; Volume 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Cisneros, K.; Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Neto, A.I. A Re-Evaluation of Scinaia (Nemaliales, Rhodophyta) in the Azores. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2011, 65, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.I. Algas Marinhas do Litoral da Ilha Graciosa. Graciosa/88, Relatório Preliminar; Relatórios e Comunicações do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade dos Açores 17; Universidade dos Açores: Ponta Delgada, Protugal, 1989; pp. 61–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, O.C. Beitrage Zur Kenntnis Der Meeresalgen Der Azoren II. Hedwigia 1929, 69, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, P.; Lopes, C.; Dionísio, M.A.; Costa, A.C. Espécies Exóticas Invasoras Marinhas da Ilha de Santa Maria, Açores; Relatórios e Comunicações do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade dos Açores 36; Universidade dos Açores: Ponta Delgada, Protugal, 2010; pp. 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Dionísio, M.A.; Micael, J.; Parente, M.I.; Norberto, R.; Cunha, A.; Brum, J.M.M.; Cunha, L.; Lopes, C.; Monteiro, S.; Palmero, A.M.; et al. Contributo Para o Conhecimento da Biodiversidade Marinha da Ilha das Flores; Relatórios e Comunicações do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade dos Açores 35; Universidade dos Açores: Ponta Delgada, Protugal, 2008; pp. 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, A.I. Checklist of the Benthic Marine Macroalgae of the Azores. Arquipel. Life Mar. Sci. 1994, 12A, 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Athanasiadis, A.; Tittley, I. Antithamnioid Algae (Rhodophyta, Ceramiaceae) Newly Recorded from the Azores. Phycologia 1994, 33, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. European Commission, Joint Research Centre, European Alien Species Information Network (EASIN). 2023. Available online: https://easin.jrc.ec.europa.eu (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Marchini, A.; Ferrario, J.; Sfriso, A.; Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A. Current Status and Trends of Biological Invasions in the Lagoon of Venice, a Hotspot of Marine NIS Introductions in the Mediterranean Sea. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 2943–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.L.; Viegas, M.C. Contribuição Para o Estudo da Zona Intertidal (Substrato Rochoso) da Ilha de São Miguel-Açores. Fácies de Corallina elongata Ellis & Solander. Resultados Preliminares. Cuad. Marisq. 1987, 11, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- Golo, R.; Vergés, A.; Díaz-Tapia, P.; Cebrian, E. Implications of Taxonomic Misidentification for Future Invasion Predictions: Evidence from One of the Most Harmful Invasive Marine Algae. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 191, 114970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICES. Interim Report of the Working Group on Introductions and Transfers of Marine Organisms (WGITMO); Document CM 2018/HAPISG; ICES: Madeira, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ardré, F.; Bouderesque, C.; Cabioch, J. Présence Remarquable Du Symphyocladia marchantioides (Harvey) Falkenberg (Rhodomélacées, Céramiales) Aux Açores. Bull. Soc. Phycol. Fr. 1974, 19, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fralick, R.A.; Hehre, E.; Mathieson, A. Observations on the Marine Algal Flora of the Azores I: Notes of the Epizoic Algae Occurring on the Marine Molluscs Patella spp. Arquipel. Life Mar. Sci 1985, 6, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Tapia, P.; Maggs, C.A.; Macaya, E.C.; Verbruggen, H. Widely Distributed Red Algae Often Represent Hidden Introductions, Complexes of Cryptic Species or Species with Strong Phylogeographic Structure. J. Phycol. 2018, 54, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredericq, S.; Serrão, E.; Norris, J. New Records of Marine Red Algae from the Azores. Arquipel. Life Mar. Sci. 1992, 10, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cardigos, F.; Tempera, F.; Fontes, J.; Ribeiro, P.; Sala, I.; Caldeira, R.; Santos, R.S. Relatório Sobre a Presença de Uma Nova Espécie No Norte da Ilha do Faial; Departamento de Oceanografia e Pescas da Universidade dos Açores: Horta, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Amat, J.N. The Recent Northern Introduction of the Seaweed Caulerpa webbiana (Caulerpales, Chlorophyta) in Faial, Azores Islands (North-Eastern Atlantic). Aquat. Invasions 2008, 3, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alós, J.; Tomas, F.; Terrados, J.; Verbruggen, H.; Ballesteros, E. Fast-Spreading Green Beds of Recently Introduced Halimeda incrassata Invade Mallorca Island (NW Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2016, 558, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulletquer, P.; Bachelet, G.; Sauriau, P.G. Noel P Open Atlantic Coast of Europe a Century of Introduced Species into French Waters. In Invasive Aquatic Species of Europe. Distribution, Impacts and Management; Leppäkoski, E., Gollasch, S., Olenin, S., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 276–290. ISBN 978-90-481-6111-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gavio, B.; Fredericq, S. Grateloupia turuturu (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) Is the Correct Name of the Non-Native Species in the Atlantic Known as Grateloupia doryphora. Eur. J. Phycol. 2002, 37, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gain, L. Algues Provenant Des Campagnes de l’Hirondelle II (1911–1912). Bull. L’Institut Océanogr. Monaco 1914, 279, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes, R.J.; McIvor, L.M.; Guiry, M.D. Using RbcL Sequence Data to Reassess the Taxonomic Position of Some Grateloupia and Dermocorynus Species (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) from the North-Eastern Atlantic. Eur. J. Phycol. 2005, 40, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiry, M.D. How Many Species of Algae Are There? J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micael, J.; Rodrigues, P.; Gíslason, S. Native vs. Non-Indigenous Macroalgae in Iceland: The State of Knowledge. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 47, 101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.L.; Smith, J.E. A Global Review of the Distribution, Taxonomy, and Impacts of Introduced Seaweeds. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2007, 38, 327–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, R.; Dubinsky, Z. Invasive and Alien Rhodophyta in the Mediterranean and along the Israeli Shores. In Red Algae in the Genomic Age; Seckbach, J., Chapman, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 45–60. ISBN 978-90-481-3794-7. [Google Scholar]

- Maggs, C.A.; Stegenga, H. Red Algal Exotics on North Sea Coasts. Helgol. Mar. Res. 1998, 52, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.V.; Beltrán, J.; Santelices, B. Colonisation and Growth Strategies in Two Codium Species (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) with Different Thallus Forms. Phycologia 2014, 53, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, T.; Payri, C.; Draisma, S.G.A.; van Reine, W.F.P.; Verbruggen, H.; Belton, G.S.; Gurgel, C.F.D.; Gabriel, D.; Sherwood, A.R.; Fredericq, S. Molecular Diversity of the Caulerpa racemosa—Caulerpa peltata Complex (Caulerpaceae, Bryopsidales) in New Caledonia, with New Australasian Records for C. racemosa var. cylindracea. Phycologia 2013, 52, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RAA Resolução n.o 15/2012/A da Assembleia Legislativa da Região Autónoma dos Açores de 2 de Abril de 2012. Regime Jurídico da Conservação da Natureza e da Proteção da Biodiversidade. Diário da República. 2012, pp. 1625–1713. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/decreto-legislativo-regional/15-2012-553893 (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- García-Gómez, J.C.; Sempere-Valverde, J.; González, A.R.; Martínez-Chacón, M.; Olaya-Ponzone, L.; Sánchez-Moyano, E.; Ostalé-Valriberas, E.; Megina, C. From Exotic to Invasive in Record Time: The Extreme Impact of Rugulopteryx okamurae (Dictyotales, Ochrophyta) in the Strait of Gibraltar. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704, 135408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, J.; Prestes, A.C.L.; Moreu, I.; Cacabelos, E.; Martins, G.M. Dramatic Changes in the Structure of Shallow-Water Marine Benthic Communities Following the Invasion by Rugulopteryx okamurae (Dictyotales, Ochrophyta) in Azores (NE Atlantic). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 175, 113358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC European Commission Implementing Regulation 2022/1203 of 12 July 2022. Amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1141 to Update the List of Invasive Alien Species of Union Concern. Off. J. Eur. Union 2022, 186, 10–13.

- RAA Resolução n.o 33/2022/A da Assembleia Legislativa da Região Autónoma dos Açores de 10 de Outubro de 2022 Número 195. Implemen-Tação Urgente de Medidas Para Combater o Impacto da Alga Rugulopteryx okamurae nos Ecossistemas Marinhos. Diário da República. 2022, pp. 5–7. Available online: https://files.dre.pt/gratuitos/1s/2022/10/19500.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2023).

- Ribeiro, C.; Sauvage, T.; Ferreira, S.; Haroun, R.; Silva, J.; Neves, P. Crossing the Atlantic: The Tropical Macroalga Caulerpa ashmeadii Harvey 1858 as a Recent Settler in Porto Santo Island (Madeira Archipelago, North-Eastern Atlantic). Aquat. Bot. 2023, 184, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangil, C.; Martín-García, L.; Afonso-Carrillo, J.; Barquín, J.; Sansón, M. Halimeda incrassata (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) Reaches the Canary Islands: Mid- and Deep-Water Meadows in the Eastern Subtropical Atlantic Ocean. Bot. Mar. 2018, 61, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiessling, T.; Gutow, L. Thiel M Marine Litter as Habitat and Dispersal Vector. In Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Bergmann, M., Gutow, L., Klages, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 141–181. ISBN 978-3-319-16509-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tempesti, J.; Mangano, M.C.; Langeneck, J.; Lardicci, C.; Maltagliati, F.; Castelli, A. Non-Indigenous Species in Mediterranean Ports: A Knowledge Baseline. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 161, 105056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiamis, K.; Azzurro, E.; Bariche, M.; Çinar, M.E.; Crocetta, F.; De Clerck, O.; Galil, B.; Gómez, F.; Hoffman, R.; Jensen, K.R.; et al. Prioritizing Marine Invasive Alien Species in the European Union through Horizon Scanning. Aquat. Conserv. 2020, 30, 794–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seubert, M. Flora Azorica; Apud Adolphum Marcum: Bonna, Germany; Hong Kong, China, 1844. [Google Scholar]

- Cardigos, F.; Monteiro, J.; Fontes, J.; Parretti, P.; Santos, R.S. Fighting Invasions in the Marine Realm, a Case Study with Caulerpa webbiana in the Azores. In Biological Invasions in Changing Ecosystems; Canning-Clode, J., Ed.; De Gruyter Open: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; pp. 279–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. EC Directive 56/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008. Establishing a Framework for Community Action in the Field of Marine Environmental Policy (Marine Strategy Framework Directive). Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 164, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Copp, G.; Vilizzi, L.; Tidbury, H.; Stebbing, P.; Tarkan, A.S.; Miossec, L.; Goulletquer, P. Development of a Generic Decision-Support Tool for Identifying Potentially Invasive Aquatic Taxa: AS-ISK. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2016, 7, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, G.H.; Vilizzi, L.; Wei, H.; Li, S.; Piria, M.; Al-Faisal, A.J.; Almeida, D.; Atique, U.; Al-Wazzan, Z.; Bakiu, R.; et al. Speaking Their Language—Development of a Multilingual Decision-Support Tool for Communicating Invasive Species Risks to Decision Makers and Stakeholders. Environ. Model. Softw. 2021, 135, 104900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Taxon | Native Range | Distribution in the Azores | Possible Vector | First Record for the Azores |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum Ochrophyta Class Phaeophyceae Order Dictyotales Family Dictyotaceae | ||||

| Rugulopteryx okamurae + | Subtropical to temperate Western Pacific Ocean [14] | São Miguel [14]; Faial [14] | Ballast waters, Hull fouling [14] | 2019 [14] |

| Order Ectocarpales Family Chordariaceae | ||||

| Papenfussiella kuromo | Northwestern Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,11,24,29]; Santa Maria [10,11,22,30]; Terceira [10]; Graciosa [10,11,21,29,31]; Pico [10]; Faial [10,11,29]; Flores [23] | Unknown [10] | 1990 [29] |

| Family Scytosiphonaceae | ||||

| Hydroclathrus tilesii + | Pacific Ocean (based on [28]) | Formigas [16]; Santa Maria [22]; Graciosa [21]; Pico [20]; Faial [17]; Flores [23] | Unknown | 1989 [20] |

| Petalonia binghamiae | Western Pacific [10] | São Miguel [9,10,11,24,31,32,33], Terceira [9,10,11,19,31,32]; Graciosa [10,11,21,31]; Pico [9,10,11,20,31,32]; Faial [9,10,11,32,34] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 1989 [34] |

| Scytosiphon dotyi + 1 | Indo-Pacific [35] | Formigas [16]; São Miguel [26] | Hull fouling [36] | 1990 [26] |

| Phylum Rhodophyta Class Florideophyceae Order Nemaliales Family Liagoraceae | ||||

| Neoizziella divaricata + | Indo-Pacific (based on [28]) | Formigas [16]; São Miguel [24]; Flores [23] | Unknown | 1989 [24] |

| Family Scinaiaceae | ||||

| Scinaia acuta * | Australia, New Zealand [11] | Santa Maria [11,22,37] | Unknown | 2005 [37] |

| Order Bonnemaisoniales Family Bonnemaisoniaceae | ||||

| Asparagopsis armata | Australia, New Zealand [9] | Formigas [16]; São Miguel [9,10,11,24,31,32]; Santa Maria [9,10,11,22,31]; Terceira [9,10,11,19,31]; Graciosa [9,10,11,21,31,38]; São Jorge [9,11,18,31]; Pico [9,10,11,20,31]; Faial [9,10,11]; Flores [9,10,11,23]; Corvo [9,10,11,23] | Hull fouling [10] | 1988 [38] |

| Asparagopsis taxiformis | Indo-Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,11,31,32,39]; Santa Maria [9,10,11,31,40]; Terceira [39]; Graciosa [9]; Pico [9,10,11,31]; Faial [9,11,39]; Flores [9,10,11,41] | Hull fouling [10] | 1928 [39] |

| Bonnemaisonia hamifera | Northwestern Pacific [10] | São Miguel [24]; Santa Maria [22]; Terceira [10,11,19,31]; Graciosa [9,10,11,38]; Faial [9,10,11,34]; Flores [9] | Ballast water or Hull fouling [10] | 1988 [38] |

| Order Ceramiales Family Callithamniaceae | ||||

| Aglaothamnion cordatum + | Indian Ocean [10] | Graciosa [10,21,31]; Pico [10,20,31] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 2006 [31] |

| Scageliopsis patens | Indo-Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,11,24,32]; Faial [10,11,42,43] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 1989 [43] |

| Family Ceramiaceae | ||||

| Acrothamnion preissii * | Indo-Pacific [12] | Santa Maria [11,12,22] | Hull fouling [12] | 2009 [12] |

| Antithamnion densum * | Indo-Pacific [10] | Pico [10,11,31] | Hull fouling [44] | 2007 [31] |

| Antithamnion diminuatum | Indo-Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,11,24,31,32]; Graciosa [10,11,21,31]; São Jorge [10,11,31]; Pico [10,11,20,31]; Faial [10,11,34,42,43] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 1989 [43] |

| Antithamnion hubbsii + | Indian Ocean [45] | São Miguel [24]; Santa Maria [22] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [45] | 1989 [22] |

| Antithamnion nipponicum + * ° | Northwestern Pacific [10] | Faial [9,10,42,43] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 1989 [43] |

| Antithamnionella elegans + * ° | Indo-Pacific [35] | São Miguel [26] | Hull fouling [26] | 2018 [26] |

| Antithamnionella spirographidis + | Indo-Pacific [35] | São Miguel [24]; Graciosa [21] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [45] | 2012 [21] |

| Antithamnionella ternifolia * 2 | Indo-Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,11,24,27,46] | Hull fouling [10] | 1987 [46] |

| Ceramium cingulatum | Indian Ocean [10] | São Miguel [10,11,31]; Terceira [10,11,19,31]; São Jorge [10,11,31]; Pico [10,11,20,31] | Unknown [10] | 2007 [31] |

| Family Delesseriaceae | ||||

| Hypoglossum heterocystideum + * | Indo-Pacific (based on [28]) | Graciosa [21] | Unknown | 2014 [21] |

| Family Rhodomelaceae | ||||

| Laurencia brongniartii + 3 | Pacific Ocean [10] | São Miguel [24]; Graciosa [10,31]; São Jorge [10,18,31]; Pico [10,20,31] | Unknown [10] | 1994 [24] |

| Laurencia chondrioides + | Western Atlantic [10] | Terceira [10,19,31]; Graciosa [10,31]; São Jorge [10,18,31]; Pico [10,20,31] | Unknown [10] | 2006 [31] |

| Laurencia dendroidea + | Indian Ocean [10] | Formigas [16]; São Miguel [10,24,31]; Graciosa [10,21,31]; São Jorge [10,31]; Pico [10,20,31]; Faial [17] | Unknown [10] | 1990 [16] |

| Laurencia minuta + | Indian Ocean (based on [28]) | Terceira [19]; Graciosa [21]; Pico [20] | Unknown | 2006 [21] |

| Lophocladia trichoclados 4 | Western Atlantic [47] | São Miguel [11,48]; Santa Maria [11,48] | Hull Fouling [48] | 2016 [48] |

| Melanothamnus harveyi | Northwestern Pacific [10] | Santa Maria [22]; Graciosa [10,11,21,31] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 2005 [31] |

| Melanothamnus sphaerocarpus + | Western Atlantic [10] | São Miguel [10,31]; Terceira [10,19,31]; Pico [10,31] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 2007 [31] |

| Symphyocladia marchantioides | Pacific [10] | Formigas [10,42,49]; São Miguel [10,11,24,31,42,46,49]; Santa Maria [10,11,22,31,42,49]; Terceira [10,11,19,31]; Graciosa [10,11,21,42,49]; São Jorge [10,11,31]; Pico [10,11,20,31,34,42,50]; Faial [9,10,11,34,42,50]; Flores [9,23] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 1971 [49] |

| Xiphosiphonia pennata + 5 | Atlantic and Pacific Oceans [51] | São Miguel [24,31,42,46]; Santa Maria [31]; Graciosa [31]; São Jorge [31] | Unknown | 1987 [46] |

| Xiphosiphonia pinnulata + 6 | Northwestern Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,24,31]; Santa Maria [10,31]; Graciosa [10,21,31] | Hull fouling [10] | 2005 [31] |

| Family Wrangeliaceae | ||||

| Grallatoria reptans + * | Western Atlantic [10] | São Miguel [10,24,31] | Unknown [10,44] | 2007–2008 [31] |

| Gymnophycus hapsiphorus * | Australia, New Zealand [11] | São Miguel [11,24,26,27,48] | Hull fouling [48] | 2009–2010 [27] |

| Spongoclonium caribaeum + | Indo-Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,31]; Pico [10,20,31] | Hull fouling, Aquaculture [10] | 2007 [31] |

| Order Gigartinales Family Cystocloniaceae | ||||

| Hypnea flagelliformis | Indo-Pacific [10] | São Miguel [10,11,31]; Pico [10,11,24,31] | Hull fouling [10] | 2007 [31] |

| Order Halymeniales Family Halymeniaceae | ||||

| Corynomorpha prismatica + * ° | Indian Ocean [10] | São Miguel [10,42,52] | Unknown [10] | 1990 [52] |

| Family Grateloupiaceae | ||||

| Grateloupia turuturu 7 | Northwestern Pacific [10] | São Miguel [11,31]; Pico [11,31] | Hull fouling [10] | 2007 [31] |

| Phylum Chlorophyta Class Ulvophyceae Order Bryopsidales Family Caulerpaceae | ||||

| Caulerpa prolifera | Western Atlantic [13] | São Miguel [11,13,24,48]; Faial [11,48,53] | Rafting, Ballast water [53], Hull fouling, Escape from aquarium [13] | 2013 [53] |

| Caulerpa webbiana * | Indian Ocean [10] | Faial [9,10,11,17] | Hull fouling [54] | 2002 [9] |

| Family Codiaceae | ||||

| Codium fragile | Northwestern Pacific [10] | São Miguel [7,10,11,24]; Santa Maria [11,22]; Graciosa [21]; Pico [20]; Flores [23]; Corvo [7,10,11,23] | Ballast water, Hull fouling [10] | 1993 [7] |

| Family Halimedaceae | ||||

| Halimeda incrassata * | Western Atlantic and Indo-Pacific [55] | Santa Maria [11,48] | Hull Fouling [48] | 2016 [48] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gabriel, D.; Ferreira, A.I.; Micael, J.; Fredericq, S. Non-Native Marine Macroalgae of the Azores: An Updated Inventory. Diversity 2023, 15, 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15101089

Gabriel D, Ferreira AI, Micael J, Fredericq S. Non-Native Marine Macroalgae of the Azores: An Updated Inventory. Diversity. 2023; 15(10):1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15101089

Chicago/Turabian StyleGabriel, Daniela, Ana Isabel Ferreira, Joana Micael, and Suzanne Fredericq. 2023. "Non-Native Marine Macroalgae of the Azores: An Updated Inventory" Diversity 15, no. 10: 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15101089

APA StyleGabriel, D., Ferreira, A. I., Micael, J., & Fredericq, S. (2023). Non-Native Marine Macroalgae of the Azores: An Updated Inventory. Diversity, 15(10), 1089. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15101089