Synthesis of Bithiophene-Based D-A1-D-A2 Terpolymers with Different A2 Moieties for Polymer Solar Cells via Direct Arylation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Polymers (P1, P2, P3, P4)

2.3. Measurement

2.4. Fabrication of Devices and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis and Thermal Property

3.2. Optical and Electrochemical Properties

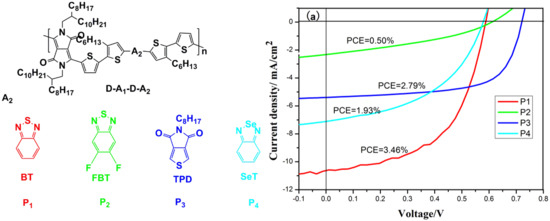

3.3. Photovoltaic Properties

3.4. Active Layer Morphology

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y. Molecular design of photovoltaic materials for polymer solar cells: Toward suitable electronic energy levels and broad bsorption. Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhu, R.; Yang, Y. Polymer solar cells. Nat. Photonics 2012, 6, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, H.; Zhao, W.; Ye, L.; Hou, J. High-efficiency polymer solar cells enabled by environment-friendly single-solvent processing. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1502177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Melkonyan, F.S.; Facchetti, A.; Marks, T.J. All-polymer solar cells: Recent progress, challenges, and prospects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhao, F.; He, Q.; Huo, L.; Wu, Y.; Parker, T.C.; Ma, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhu, D. High-performance electron acceptor with thienyl side chains for organic photovoltaics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 4955–4961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierini, F.; Lanzi, M.; Nakielski, P.; Pawłowska, S.; Urbanek, O.; Zembrzycki, K.; Kowalewski, T.A. Single-material organic solar cells based on electrospun fullerene-grafted polythiophenenanofibers. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 4972–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Dou, L.; Yoshimura, K.; Kato, T.; Ohya, K.; Moriarty, T.; Emery, K.; Chen, C.C.; Gao, J.; Li, G. A polymer tandem solar cell with 10.6% power conversion efficiency. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, W.; Hendriks, K.H.; Furlan, A.; Roelofs, W.S.C.; Wienk, M.M.; Janssen, R.A.J. Universal correlation between fibril width and quantum efficiency in diketopyrrolopyrrole-based polymer solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18942–18948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, D.; Chen, W.; Yang, R.; Zhu, W.; Mammo, W.; Wang, E. Fluorine substitution enhanced photovoltaic performance of a D-A1-D-A2 copolymer. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 9335–9337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Ma, Z.; Dang, D.; Zhu, W.; Andersson, M.R.; Zhang, F.; Wang, E. An alternating D-A1-D-A2 copolymer containing two electron-deficient moieties for efficient polymer solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 11141–11144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshtov, M.; Kuklinm, S.A.; Godovsky, D.Y.; Khokhlov, A.R.; Kurchania, R.; Chen, F.C.; Koukaras, E.N.; Sharma, G.D. New alternating D-A1-D-A2 copolymer containing two electron-deficient moieties based on benzothiadiazole and 9-(2-Octyldodecyl)-8H-pyrrolo[3,4-b]bisthieno[2,3-f:3′,2′-h]quinoxaline-8,10(9H)-dione for efficient polymer solar cells. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2016, 54, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthi, N.; Gunasekar, K.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, D.H.; Song, M.; Park, Y.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Shin, Y.; Kang, I.N.; Jin, S.H. Synthesis, characterization, and photovoltaic properties of 4,8-dithienylbenzo[1,2-b:4,5-b]dithiophene-based donor-acceptor polymers with new polymerization and 2D conjugation extension pathways: A potential donor building block for high performance and stable inverted organic solar cells. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2454–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohra, H.; Wang, M.F. Direct C–H arylation: A “Greener” approach towards facile synthesis of organic semiconducting molecules and polymers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 11550–11571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolka, M.; Nasrallah, I.; Rose, B.; Ravva, M.K.; Broch, K.; Sadhanala, A.; Harkin, D.; Charmet, J.; Hurhangee, M.; Brown, A.; et al. High operational and environmental stability of high-mobility conjugated polymer field-effect transistors through the use of molecular additives. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierini, F.; Nakielski, P.; Urbanek, O.; Pawłowska, S.; Lanzi, M.; Sio, L.D.; Kowalewski, T.A. Polymer-based nanomaterials for photothermal therapy: FROM light-responsive to multifunctional nanoplatforms for synergistically combined technologies. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 4147–4167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, L.G.; Leclerc, M. Direct (hetero) arylation: A new tool for polymer chemists. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 1597–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lombeck, F.; Matsidik, R.; Komber, H.; Sommer, M. Simple synthesis of P(Cbz-alt-TBT) and PCDTBT by combining direct arylation with Suzuki polycondensation of heteroaryl chlorides. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015, 36, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homyak, P.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Russel, T.P.; Coughlin, E.B. Systematic variation of fluorinated diketopyrrolopyrrole low bandgap conjugated polymers: Synthesis by direct arylation polymerization and characterization and performance in organic photovoltaics and organic field-effect transistors. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 6978–6986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouliot, J.R.; Mercier, L.G.; Caron, S.; Leclerc, M. Accessing new DPP-Based copolymers by direct heteroarylation polymerization. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013, 214, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakioka, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Wang, Q.; Ozawa, F. Direct arylation of 2-methylthiophene with isolated [PdAr(μ-O2CR)(PPh3)]n complexes: Kinetics and Mechanism. Organometallics 2012, 31, 4810–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.X.; Wang, W.; Lv, W.; Yan, S.H.; Zhang, T.; Zhen, H.Y.; Ling, Q.D. Simple synthesis of novel terthiophene-based D-A1-D-A2 polymers for polymer solar cells. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 86276–86284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Uddin, M.A.; Lee, C.; Kim, K.H.; Nguyen, T.L.; Lee, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Woo, H.Y. Determining the role of polymer molecular weight for high-performance all-polymer solar cells: Its effect on polymer aggregation and phase separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2359–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; An, Y.; Dutta, G.K.; Kim, Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Li, Y.F.; Yang, C. A synergetic effect of molecular weight and fluorine in all-polymer solar cells with enhanced performance. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 27, 1603564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.M.; Wang, W.; Lv, W.; Lu, M.X.; Yan, S.H.; Liang, L.Y.; Ling, Q.D. Synthesis of regular D-A1-D-A2 copolymers via direct arylation polycondensation and application in solar cells. Synth. Met. 2015, 209, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Fang, J.; Yan, H.; Zhu, X.; Yi, Y.; Wei, Z. A facile strategy to enhance absorption coefficient and photovoltaic performance of two-dimensional benzo[1,2-b:4,5-b]dithiophene and thieno[3,4-c]pyrrole-4,6-dione polymers via subtle chemical structure variations. Org. Electron. 2013, 14, 2652–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, K.H.; Li, W.; Wienk, M.M.; Janssen, R.A. Small-bandgap semiconducting polymers with high near-infrared photoresponse. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12130–12136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Tang, S.W.; Zhang, W.; Tao, Y.; Wong, M.S. Naphthodithiophene-2, 1, 3-benzothiadiazole copolymers for bulk heterojunction solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 9471–9473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Chen, Z.; Wei, W.; Jiang, Z. Fluorinated benzothiadiazole-based conjugated polymers for high-performance polymer solar cells without any processing additives or post-treatments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 17060–17068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Ju, X.; Zhao, J. Effects of fluoro substitution on the electrochromic performance of alternating benzotriazole and benzothiadiazole-based donor–acceptor type copolymers. Polymers 2018, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.D.; Fan, J.; Seifter, J.; Lim, B.; Hufschmid, R.; Heeger, A.J.; Wudl, F. High performance weak donor-acceptor polymers in thin film transistors: Effect of the acceptor on electronic properties, ambipolar conductivity, mobility, and thermal stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 20799–20807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröter, S.; Stock, C.; Bach, T. Regioselective cross-coupling reactions of multiple halogenated nitrogen-, oxygen-, and sulfur-containing heterocycles. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyan, S.; Kim, F.; Ren, G.; Li, H. JenekheA. High mobility thiazole–diketopyrrolopyrrole copolymer semiconductors for high performance field-effect transistors and photovoltaic devices. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 9029–9037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleeuw, D.; Simenon, M.; Brown, A.; Einerhand, R. Stability of n-type doped conducting polymers and consequences for polymeric microelectronic devices. Synth. Met. 1997, 87, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, H.; Shacklette, L.W.; Jen, K.Y.; Elsenbaumer, R.L. The electronic and electrochemical properties of poly (phenylene vinylenes) and poly (thienylene vinylenes): An experimental and theoretical study. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 91, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hendriks, K.H.; Furlan, A.; Zhang, A.; Wienk, M.; Janssen, R.A. A regioregular terpolymer comprising two electron-deficient and one electron-rich unit for ultra small band gap solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 4290–4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Polymer | Solution (nm) a | Film (nm) b | Egopt | Ered | Eoxd | HOMO | LUMO | Egcv | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λmax | λonset | λmax | Fwhm c | λonset | eV d | eV | eV | eV | eV | eV e | |

| P1 | 750 | 981 | 748 | 280 | 1018 | 1.23 | −0.94 | 0.74 | −5.16 | −3.48 | 1.68 |

| P2 | 720 | 967 | 719 | 266 | 986 | 1.26 | −0.70 | 0.80 | −5.22 | −3.72 | 1.50 |

| P3 | 691 | 890 | 751 | 260 | 1019 | 1.22 | −0.78 | 0.82 | −5.24 | −3.64 | 1.60 |

| P4 | 567 | 890 | 734 | 298 | 1019 | 1.22 | −0.93 | 0.77 | −5.19 | −3.49 | 1.70 |

| Polymer | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | ELUMOpolymer–ELUMOPC71BM (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 0.59 | 10.70 b (10.30) c | 54.8 b (54.2) c | 3.46 b (3.29) c | 0.52 |

| P2 | 0.61 | 2.32 (2.22) | 35.4 (35.1) | 0.50 (0.48) | 0.28 |

| P3 | 0.72 | 5.93 (5.62) | 65.3 (64.3) | 2.79 (2.60) | 0.36 |

| P4 | 0.58 | 7.08 (6.51) | 47.2 (46.8) | 1.93 (1.77) | 0.53 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, J.; Lin, Z.; Feng, W.; Wang, W. Synthesis of Bithiophene-Based D-A1-D-A2 Terpolymers with Different A2 Moieties for Polymer Solar Cells via Direct Arylation. Polymers 2019, 11, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11010055

Huang J, Lin Z, Feng W, Wang W. Synthesis of Bithiophene-Based D-A1-D-A2 Terpolymers with Different A2 Moieties for Polymer Solar Cells via Direct Arylation. Polymers. 2019; 11(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Jinfeng, Zhenkun Lin, Wenhuai Feng, and Wen Wang. 2019. "Synthesis of Bithiophene-Based D-A1-D-A2 Terpolymers with Different A2 Moieties for Polymer Solar Cells via Direct Arylation" Polymers 11, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11010055