Impact of Aerosol-Cloud Cycling on Aqueous Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation

Abstract

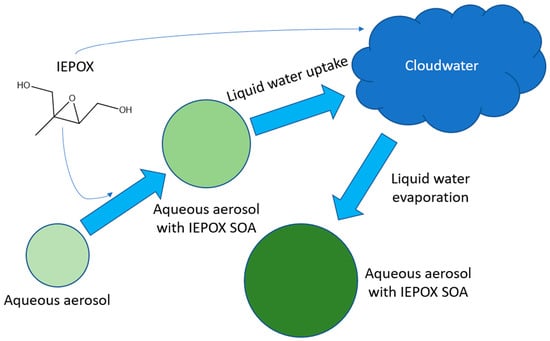

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. GAMMA 5.0

2.2. Simulation Conditions

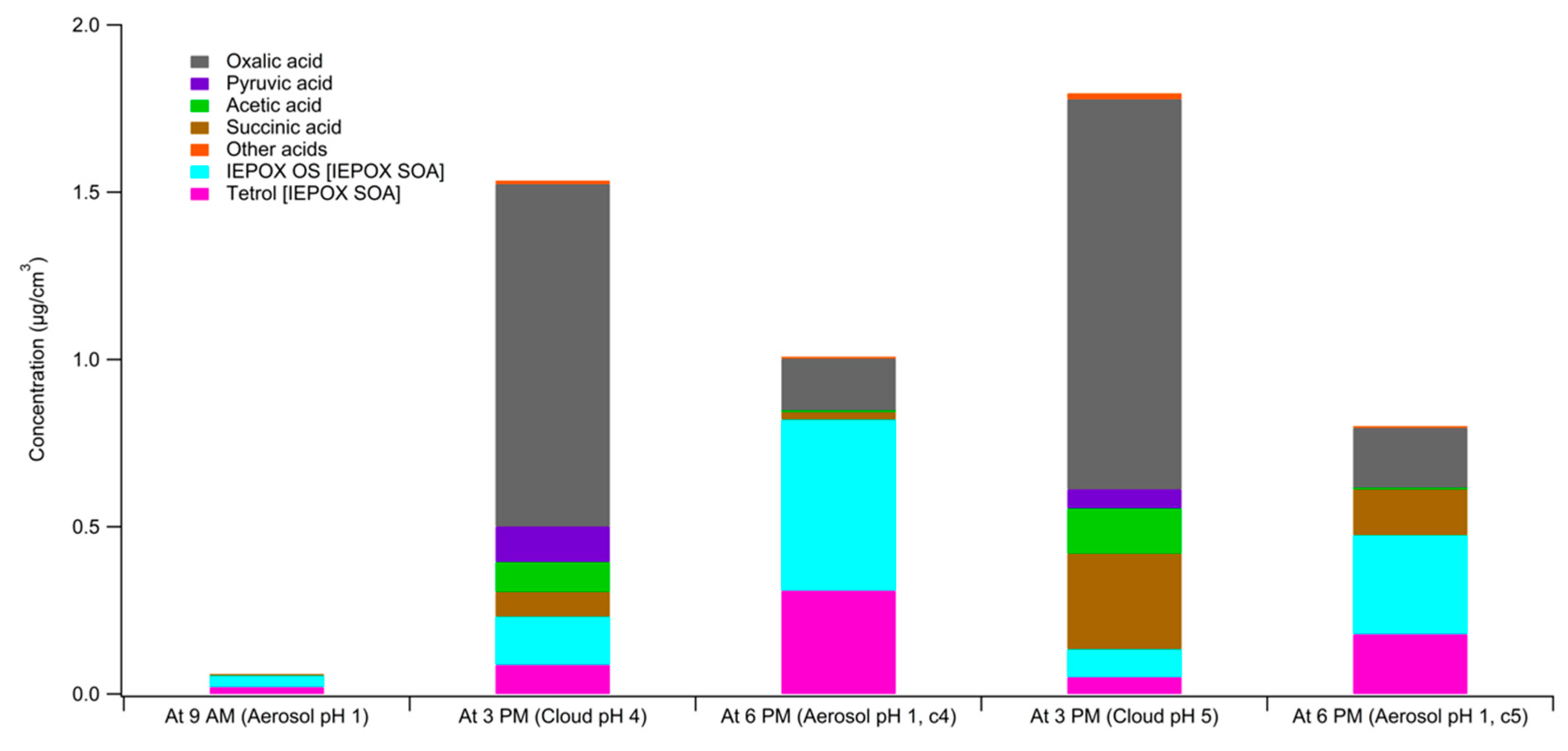

3. Results

4. Atmospheric Implications

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanakidou, M.; Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N.; Barnes, I.; Dentener, F.J.; Facchini, M.C.; Van Dingenen, R.; Ervens, B.; Nenes, A.; Nielsen, C.J.; et al. Organic aerosol and global climate modelling: A review. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2005, 5, 1053–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.V.; Zhang, Q.; Jimenez, J.L.; Pike, M.; Carlton, A.G. Liquid Water: Ubiquitous Contributor to Aerosol Mass. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2016, 3, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, J.L.; Canagaratna, M.R.; Donahue, N.M.; Prévôt, A.S.H.; Zhang, Q.; Kroll, J.H.; DeCarlo, P.F.; Allan, J.D.; Coe, H.; Ng, N.L.; et al. Evolution of Organic Aerosols in the Atmosphere. Science 2009, 326, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Gouw, J.A.; Jimenez, J.L. Organic Aerosols in the Earth’s Atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 7614–7618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, P.Y. Measurement of the timescale of hygroscopic growth for atmospheric aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, D.J. Introduction to Atmospheric Chemistry; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1999; ISBN 9781680159073. [Google Scholar]

- Hallquist, M.; Wenger, J.C.; Baltensperger, U.; Rudich, Y.; Simpson, D.; Claeys, M.; Dommen, J.; Donahue, N.M.; George, C.; Goldstein, A.H.; et al. The formation, properties and impact of secondary organic aerosol: Current and emerging issues. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 5155–5236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, V.F. Aqueous Organic Chemistry in the Atmosphere: Sources and Chemical Processing of Organic Aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jimenez, J.L.; Canagaratna, M.R.; Allan, J.D.; Coe, H.; Ulbrich, I.M.; Alfarra, M.R.; Takami, A.; Middlebrook, A.M.; Sun, Y.L.; et al. Ubiquity and dominance of oxygenated species in organic aerosols in anthropogenically-influenced Northern Hemisphere midlatitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2007, 34, L13801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herckes, P.; Valsaraj, K.T.; Collett, J.L. A review of observations of organic matter in fogs and clouds: Origin, processing and fate. Atmos. Res. 2013, 132–133, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervens, B.; Sorooshian, A.; Aldhaif, A.M.; Shingler, T.; Crosbie, E.; Ziemba, L.; Campuzano-Jost, P.; Jimenez, J.L.; Wisthaler, A. Is there an aerosol signature of chemical cloud processing? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 16099–16119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics; European Geophysical Society: Munich, Germany, 1998; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Lance, S.; Barth, M.; Carlton, A.; Lance, S.; Barth, M.; Carlton, A. Multiphase Chemistry: Experimental Design for Coordinated Measurement and Modeling Studies of Cloud Processing at a Mountaintop. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2017, 98, ES163–ES167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adirondack Lakes Survey Corporation-Whiteface Mountain Cloud Monitoring. Available online: http://www.adirondacklakessurvey.org/wfc.shtml (accessed on 25 September 2019).

- Pye, H.O.T.; Nenes, A.; Alexander, B.; Ault, A.P.; Barth, M.; Clegg, S.; Collett, J.L., Jr.; Fahey, K.M.; Hennigan, C.J.; Herrmann, H.; et al. The Acidity of Atmospheric Particles and Clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2019. in review. [Google Scholar]

- Henze, D.K.; Seinfeld, J.H. Global secondary organic aerosol from isoprene oxidation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L09812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, A.; Karl, T.; Harley, P.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Palmer, P.I.; Geron, C. Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using MEGAN (Model of Emissions of Gases and Aerosols from Nature). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2006, 6, 3181–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, A.G.; Wiedinmyer, C.; Kroll, J.H. A Review of Secondary Organic Aerosol (SOA) Formation from Isoprene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2009, 9, 4987–5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surratt, J.D.; Lewandowski, M.; Offenberg, J.H.; Jaoui, M.; Kleindienst, T.E.; Edney, E.O.; Seinfeld, J.H. Effect of acidity on secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 5363–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surratt, J.D.; Chan, A.W.H.; Eddingsaas, N.C.; Chan, M.; Loza, C.L.; Kwan, A.J.; Hersey, S.P.; Flagan, R.C.; Wennberg, P.O.; Seinfeld, J.H. Reactive intermediates revealed in secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, V.F.; Woo, J.L.; Kim, D.D.; Schwier, A.N.; Wannell, N.J.; Sumner, A.J.; Barakat, J.M. Aqueous-Phase Secondary Organic Aerosol and Organosulfate Formation in Atmospheric Aerosols: A Modeling Study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8075–8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, C.J.; Riedel, T.P.; Zhang, Z.; Gold, A.; Surratt, J.D.; Thornton, J.A. Reactive Uptake of an Isoprene-Derived Epoxydiol to Submicron Aerosol Particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 11178–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, H.O.T.; Murphy, B.N.; Xu, L.; Ng, N.L.; Carlton, A.G.; Guo, H.; Weber, R.J.; Vasilakos, P.; Appel, K.W.; Budisulistiorini, S.H.; et al. On the implications of aerosol liquid water and phase separation for organic aerosol mass. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 343–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmedding, R.; Ma, M.; Zhang, Y.; Farrell, S.; Pye, H.O.T.; Chen, Y.; Wang, C.T.; Rasool, Q.Z.; Budisulistiorini, S.H.; Ault, A.P.; et al. α-Pinene-Derived organic coatings on acidic sulfate aerosol impacts secondary organic aerosol formation from isoprene in a box model. Atmos. Environ. 2019, 213, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraiwa, M.; Berkemeier, T.; Schilling-Fahnestock, K.A.; Seinfeld, J.H.; Pöschl, U. Molecular corridors and kinetic regimes in the multiphase chemical evolution of secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 8323–8341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liu, P.F.; Hanna, S.J.; Li, Y.J.; Martin, S.T.; Bertram, A.K. Relative humidity-dependent viscosities of isoprene-derived secondary organic material and atmospheric implications for isoprene-dominant forests. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 5145–5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, J.P.; Bertram, A.K.; Topping, D.O.; Laskin, A.; Martin, S.T.; Petters, M.D.; Pope, F.D.; Rovelli, G. The viscosity of atmospherically relevant organic particles. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’ambro, E.L.; Schobesberger, S.; Gaston, C.J.; Lopez-Hilfiker, F.D.; Lee, B.H.; Liu, J.; Zelenyuk, A.; Bell, D.; Cappa, C.D.; Helgestad, T.; et al. Chamber-based insights into the factors controlling epoxydiol (IEPOX) secondary organic aerosol (SOA) yield, composition, and volatility. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 11253–11265. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Palm, B.B.; Day, D.A.; Campuzano-Jost, P.; Krechmer, J.E.; Peng, Z.; de Sá, S.S.; Martin, S.T.; Alexander, M.L.; Baumann, K.; et al. Volatility and lifetime against OH heterogeneous reaction of ambient isoprene-epoxydiols-derived secondary organic aerosol (IEPOX-SOA). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 11563–11580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Lambe, A.T.; Olson, N.E.; Lei, Z.; Craig, R.L.; Zhang, Z.; Gold, A.; Onasch, T.B.; Jayne, J.T.; et al. Effect of the Aerosol-Phase State on Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation from the Reactive Uptake of Isoprene-Derived Epoxydiols (IEPOX). Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2018, 5, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, Z.; Olson, N.E.; Boyer, H.C.; Narayan, S.; Yee, L.D.; Green, H.S.; Cui, T.; et al. Increasing Isoprene Epoxydiol-to-Inorganic Sulfate Aerosol Ratio Results in Extensive Conversion of Inorganic Sulfate to Organosulfur Forms: Implications for Aerosol Physicochemical Properties. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 8682–8694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.W.; Campuzano-Jost, P.; Palm, B.B.; Day, D.A.; Ortega, A.M.; Hayes, P.L.; Krechmer, J.E.; Chen, Q.; Kuwata, M.; Liu, Y.J.; et al. Characterization of a real-time tracer for isoprene epoxydiols-derived secondary organic aerosol (IEPOX-SOA) from aerosol mass spectrometer measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 11807–11833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Coggon, M.M.; Bates, K.H.; Zhang, X.; Schwantes, R.H.; Schilling, K.A.; Loza, C.L.; Flagan, R.C.; Wennberg, P.O.; Seinfeld, J.H. Organic aerosol formation from the reactive uptake of isoprene epoxydiols (IEPOX) onto non-acidified inorganic seeds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014, 14, 3497–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddingsaas, N.C.; VanderVelde, D.G.; Wennberg, P.O. Kinetics and Products of the Acid-Catalyzed Ring-Opening of Atmospherically Relevant Butyl Epoxy Alcohols. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 8106–8113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, C.L.; Jacob, D.J.; Park, R.J.; Russell, L.M.; Huebert, B.J.; Seinfeld, J.H.; Liao, H.; Weber, R.J. A large organic aerosol source in the free troposphere missing from current models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L18809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blando, J.D.; Turpin, B.J. Secondary organic aerosol formation in cloud and fog droplets: A literature evaluation of plausibility. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 1623–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, A.G.; Turpin, B.J.; Altieri, K.E.; Seitzinger, S.P.; Mathur, R.; Roselle, S.J.; Weber, R.J. CMAQ Model Performance Enhanced When In-Cloud Secondary Organic Aerosol is Included: Comparisons of Organic Carbon Predictions with Measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 8798–8802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervens, B.; Turpin, B.J.; Weber, R.J. Secondary organic aerosol formation in cloud droplets and aqueous particles (aqSOA): A review of laboratory, field and model studies. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 11069–11102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervens, B. Modeling the Processing of Aerosol and Trace Gases in Clouds and Fogs. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4157–4198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.L.; McNeill, V.F. simpleGAMMA v1.0–A reduced model of secondary organic aerosol formation in the aqueous aerosol phase (aaSOA). Geosci. Model. Dev. 2015, 8, 1821–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budisulistiorini, S.H.; Nenes, A.; Carlton, A.G.; Surratt, J.D.; McNeill, V.F.; Pye, H.O.T. Simulating Aqueous-Phase Isoprene-Epoxydiol (IEPOX) Secondary Organic Aerosol Production During the 2013 Southern Oxidant and Aerosol Study (SOAS). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 5026–5034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budisulistiorini, S.H.; Li, X.; Bairai, S.T.; Renfro, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Mckinney, K.A.; Martin, S.T.; Mcneill, V.F.; Pye, H.O.T.; et al. Examining the effects of anthropogenic emissions on isoprene-derived secondary organic aerosol formation during the 2013 Southern Oxidant and Aerosol Study (SOAS) at the Look Rock, Tennessee ground site. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 8871–8888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, M.; Andreae, M.O.; Artaxo, P.; Barbosa, H.M.J.; Berg, L.K.; Brito, J.; Ching, J.; Easter, R.C.; Fan, J.; Fast, J.D.; et al. Urban pollution greatly enhances formation of natural aerosols over the Amazon rainforest. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.E. Mass-Transport Considerations Pertinent to Aqueous Phase Reactions of Gases in Liquid-Water Clouds; Jaeschke, W., Ed.; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1986; Volume G6, pp. 425–471. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, J.L.; Kim, D.D.; Schwier, A.N.; Li, R.; Faye McNeill, V. Aqueous aerosol SOA formation: Impact on aerosol physical properties. Faraday Discuss. 2013, 165, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, W.G.; Rao, Y.; Dai, H.-L.; McNeill, V.F. Modeling Photosensitized Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation in Laboratory and Ambient Aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 7496–7501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.L.; Brimblecombe, P.; Wexler, A.S. Thermodynamic Model of the System H + -NH4 + -SO42−NO3 −H2O at Tropospheric Temperatures. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 2137–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, S.L.; Seinfeld, J.H.; Brimblecombe, P. Thermodynamic modelling of aqueous aerosols containing electrolytes and dissolved organic compounds. J. Aerosol Sci. 2001, 32, 713–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Lee, P.B.; Updyke, K.M.; Bones, D.L.; Laskin, J.; Laskin, A.; Nizkorodov, S.A. Formation of nitrogen- and sulfur-containing light-absorbing compounds accelerated by evaporation of water from secondary organic aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D01207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, D.O.; Corrigan, A.L.; Tolbert, M.A.; Jimenez, J.L.; Wood, S.E.; Turley, J.J. Secondary organic aerosol formation by self-reactions of methylglyoxal and glyoxal in evaporating droplets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 8184–8190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacman-VanWertz, G.; Yee, L.D.; Kreisberg, N.M.; Wernis, R.; Moss, J.A.; Hering, S.V.; de Sá, S.S.; Martin, S.T.; Alexander, M.L.; Palm, B.B.; et al. Ambient Gas-Particle Partitioning of Tracers for Biogenic Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 9952–9962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasio, C.; Faust, B.C.; Rao, C.J. Aromatic carbonyl compounds as aqueous-phase photochemical sources of hydrogen peroxide in acidic sulfate aerosols, fogs, and clouds. 1. Non- phenolic methoxybenzaldehydes and methoxyacetophenones with reductants (phenols). Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997, 31, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.J.; Guo, H.; Russell, A.G.; Nenes, A. High aerosol acidity despite declining atmospheric sulfate concentrations over the past 15 years. Nat. Geosci. 2016, 9, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Feingold, G.; Xue, H.; Feingold, G. Large-Eddy Simulations of Trade Wind Cumuli: Investigation of Aerosol Indirect Effects. J. Atmos. Sci. 2006, 63, 1605–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feingold, G.; McComiskey, A.; Rosenfeld, D.; Sorooshian, A. On the relationship between cloud contact time and precipitation susceptibility to aerosol. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2013, 118, 10544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen, N.; Waxman, E.M.; Turpin, B.J.; Volkamer, R.; Carlton, A.G. Potential of aerosol liquid water to facilitate organic aerosol formation: Assessing knowledge gaps about precursors and partitioning. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 3327–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Guo, H.; Boyd, C.M.; Klein, M.; Bougiatioti, A.; Cerully, K.M.; Hite, J.R.; Isaacman-VanWertz, G.; Kreisberg, N.M.; Knote, C.; et al. Effects of anthropogenic emissions on aerosol formation from isoprene and monoterpenes in the southeastern United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aqueous Aerosol | Cloudwater | |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid water fraction | 1.36 × 10−11 cm3 cm−3 | 8.0 × 10−7 cm3 cm−3 |

| Water concentration | 46.1 mol L−1 | 55.5 mol L−1 |

| Relative humidity | 80% | 100% |

| Radius of particle or cloud droplet | 48 nm | 10 μm |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsui, W.G.; Woo, J.L.; McNeill, V.F. Impact of Aerosol-Cloud Cycling on Aqueous Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10110666

Tsui WG, Woo JL, McNeill VF. Impact of Aerosol-Cloud Cycling on Aqueous Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation. Atmosphere. 2019; 10(11):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10110666

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsui, William G., Joseph L. Woo, and V. Faye McNeill. 2019. "Impact of Aerosol-Cloud Cycling on Aqueous Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation" Atmosphere 10, no. 11: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10110666

APA StyleTsui, W. G., Woo, J. L., & McNeill, V. F. (2019). Impact of Aerosol-Cloud Cycling on Aqueous Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation. Atmosphere, 10(11), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10110666