Abstract

The spatial heterogeneity of plant diversity at the neighborhood scale has less been understood, although it is very important for the planning and management of neighborhood landscape. In this case study of Beijing, we conducted intensive investigations of the plant diversity in different neighborhoods along a rural–urban gradient. The results showed that the mean numbers of plant species per neighborhood were 30.5 for trees, 18.8 for shrubs, and 31.9 for herbs, respectively. There were significant logarithmic relationships between the numbers of species and patch area, indicating that larger patches within neighborhoods could harbor more plant species. Hierarchical linear modeling showed that the variations in plant diversity within neighborhoods were higher than those between neighborhoods. The number of species increased logistically with both the number of patches within neighborhoods and the number of neighborhoods, suggesting that it is important to sample a sufficient number of patches within neighborhoods, as well as a sufficient number of neighborhoods in order to sample 90% of the plant species during the investigation of plant diversity in urban neighborhoods. So the hierarchical design of sampling should be recommended for investigating plant diversity in urban areas.

1. Introduction

Urban green spaces provide a wealth of available habitats for plants and animals, as well as multiple ecosystem services for residents by mitigating heat stress and the occurrence of flooding, reducing air and water pollution, enhancing carbon sequestration and aesthetic value, and promoting human health [1,2]. Because of easy accessibility, green spaces have increased rapidly in neighborhoods, especially in recently developed neighborhoods with high-rise residential buildings in modern cities [3,4,5]. The green spaces within neighborhoods account for 13% of the total area of the green spaces in Beijing, China [6]. The increases in green spaces within neighborhoods from 1989 to 2004 exceeded those in other urban functional units, such as roadsides, riparian zones, and scenic spots, in Jinan, China [7]. Thus, many studies of green spaces in neighborhoods have been conducted in urban areas [3,8].

Plant diversity as a fundamental element of green spaces determines the ecosystem functions and services that can be derived directly by residents. Green spaces in neighborhoods host a substantial level of plant diversity, especially for the native species that contributed 52.4% of the total number of tree species of neighborhoods in Beijing, China [9,10]. In addition, green spaces in neighborhoods often have a higher percentage of native species than those in other land-use types, such as roadsides, institutional areas, community parks, and commercial areas [10]. However, alien species, such as Buchloe dactyloides native to America, have invaded the green spaces in neighborhoods in Beijing [9]. Thus, the survey of plant diversity in neighborhoods is of great significance for the protection of native species and the application of native species to create new urban landscapes. The plant diversity in neighborhoods has been investigated widely at the city scale, country scale, and continental scale to optimize biodiversity conservation strategies, enhance ecosystem services, and improve the quality of life for city dwellers [1]. At the city scale, it was demonstrated that the plant diversity varied with gradients in terms of land use, population density, and biophysical conditions (e.g., air temperature) [3,11], as well as according to socio-economic factors [5,12] and landscape features [13]. At the country or continental scales, the homogenization of plant diversity has been confirmed due to the dominant effects of human activities [14,15,16].

Homogenization of residential plant compositions has been demonstrated based on genetic, taxonomic, and functional similarities [15,16,17,18] across large spatial scales, such as country and continent scales, because of similarities in the management and preferences of residents [17,18], as well as the planning and development of neighborhoods [3,19], and/or the microenvironments among neighborhoods [14,20]. Taxonomic homogenization has been reported frequently. Neighborhood-adaptable species have become increasingly widespread in neighborhoods [16]. For example, Lolium perenne was found in 90% of the residential lawns surveyed in Boston, USA [16], more than 50% of the lawns in Paris, France [21], and more than 80% of the lawns in Christchurch, New Zealand [22]. Residential plant communities generally comprise few species, with a greater proportion of individuals from certain species relative to those in natural plant communities [21,22,23,24].

The homogenization of plant species compositions or heterogeneity of plant diversity indices has been demonstrated by comparing the species compositions and diversity among neighborhoods at the city scale, country scale, and/or continental scale [3,12,14,24]. However, the plant compositions and diversity within neighborhoods have been analyzed less frequently, although they are spatially heterogeneous. In old cities, the front and back yards differ in terms of their vegetation composition and structure [25]. Front yards host more ornamental species with high ornamental value compared with backyards, and the latter contains more food plants for consumption by city dwellers [1]. In new or intensively developed urban areas, the neighborhoods comprise mosaic patches of buildings, paved lands, and green spaces [3,19]. The green patches within these neighborhoods vary in terms of their size, shape, and distance from the nearest green patches and the boundaries of neighborhoods [26,27], but they are also designed with various species compositions in order to create diverse landscape appearances with high aesthetic value and multiple services [12,27]. The variations in the species compositions and plant diversity among patches within neighborhoods directly determine the diversity level and management practices for the whole neighborhood. Thus, it is important to improve the accuracy of plant diversity assessments to enhance the effectiveness of residential green spaces to protect urban biodiversity and provide ecosystem services to residents.

In this study, we intensively investigated the green spaces in 12 neighborhoods in the urban areas of Beijing, China, in order to determine the heterogeneity of the species composition and plant diversity in this urban environment. In particular, we addressed the following questions. (1) Is the plant diversity within neighborhoods significantly heterogeneous? (2) Do significant species–patch area relationships exist in neighborhoods? (3) How many patches and neighborhoods need to be investigated to assess the plant diversity in Beijing?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

This study was conducted in the built-up area of Beijing, China (40°00′ N, 116°20′ E). The study area located in the northeast of the Huabei Plain in north China is characterized by warm temperate deciduous broad-leaved forests [28]. Beijing has a temperate, humid, monsoonal continental climate characterized by hot and rainy summers, cold and dry winters, and short spring and autumn seasons [6]. The average annual precipitation and temperature are around 500 mm and 11–12 °C, respectively [6].

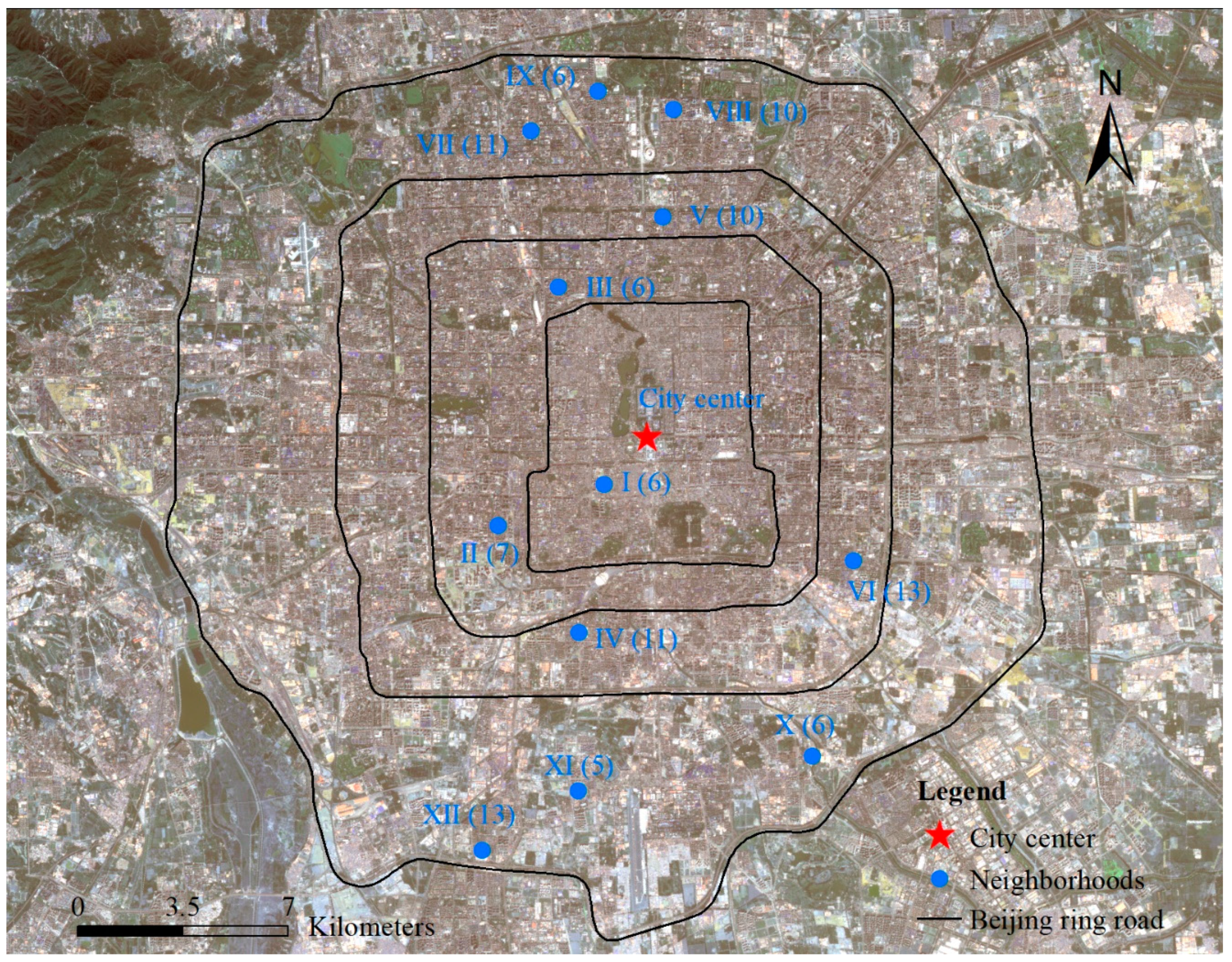

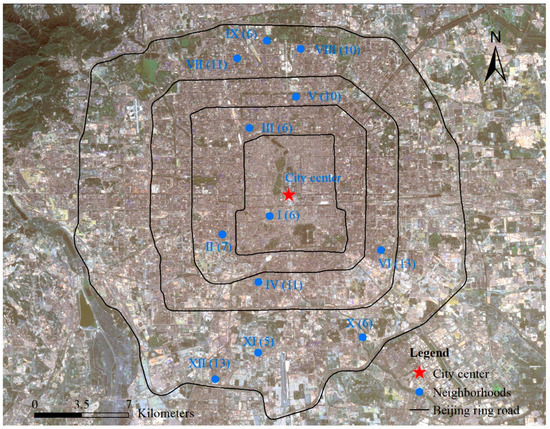

Twelve neighborhoods were selected from south to north throughout the urban area of Beijing (Figure 1 and Table 1) based on the following criteria: (1) the surveyed sites were spatially distributed in a balanced manner in the south–north direction (Figure 1), with different degrees of urbanization [29,30]; (2) the sites covered the common sizes of the neighborhoods in Beijing [31], where the areas of the neighborhoods ranged from 3.29 ha to 22.11 ha (Table 1); (3) the whole range of house prices in Beijing was covered [32] in the house transaction price range from 41,901 yuan/m2 to 118,947 yuan/m2 (Table 1) during 2018; and (4) the neighborhoods covered the 30 years when Beijing was developing rapidly [33,34] from 1980 to 2011 (house ages from 7 years to 38 years) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

The location of neighborhoods investigated along the urban-rural gradient in Beijing. The numbers in parentheses indicate the numbers of patches investigated in the neighborhood. I: Chunshuyuan; II: Xiaohongmiao; III: Jindianhuayuan; Ⅳ: Jiayuanerli; Ⅴ: Anzhenxili; Ⅵ: Songyudongli; Ⅶ: Dongwangzhuang; Ⅷ: Huizhongbeili; Ⅸ: Lincuixili; Ⅹ: Delinyuan; Ⅺ: Nantingxinyuan; Ⅻ: Ruihaijiayuan.

Table 1.

Basic information of neighborhoods investigated.

2.2. Field Survey

The green spaces within neighborhoods were designed as fragmented units in different patches for construction and management purposes. Thus, the green patches were assigned as sampling units or plots in the present study [6]. The number of patches surveyed per neighborhood ranged from five to 13 (Figure 1 and Appendix A Figure A1). All patches surveyed are artificial green spaces [35], and there is no natural or semi-natural vegetation. The patches surveyed in each neighborhood were spatially balanced and they covered more than 55% of the green patches with sizes larger than 400 m2 (except in Jiayuanerli, which contained an excessive number of patches). Plant species were investigated in August and September during 2017. The species was identified and named based on the Flora of China [36] and the Flora of Beijing [37]. The life form and source of species were determined according to the Flora of China [36], the Flora of Beijing [37], and Zhao et al. [6]. In each plot, we recorded all tree and shrub species as well as their abundances, and three to five herb quadrats (1 m × 1 m) were randomly selected to record all herb species and their coverage levels. In total, 104 patches were investigated in 12 neighborhoods. The areas and locations of patches were measured using a global positioning system device (Unistrong Industrial Co. Ltd., Beijing, China).

2.3. Plant Diversity Indices

The commonly used plant diversity indices [5,38] comprising the species number, Gleason index, and Shannon index were calculated for each patch and each neighborhood. Equations (1) and (2) were used to calculate the Gleason index and Shannon index [39,40]:

where S is the number of species in each patch or each neighborhood, A is the area of each patch or each neighborhood, Pi is ni/N where ni is the number of an individual species i, N is the individual number of all species, and the individual number of herbs was replaced by the coverage with herbs.

2.4. Species–Area Relationship

The relationships between the number of species in patches and the areas of patches were modeled for trees, shrubs, and herbs using a power function (Equation (3)) [41,42]:

where S is the number of species, A is the area of patches, z is the slope, and c is the intercept of the log–log regression equation.

2.5. Species Accumulation Curve

Species accumulation curves were modeled using a power function (Equation (4)) between the number of species and area of the green patches surveyed and the area of the neighborhood surveyed [41,42] in order to compare the species turnover between patches and between neighborhoods:

where S′ is the cumulative number of species, A′ is the cumulative area of patches or the cumulative survey area of neighborhoods, z is the slope, and c is the intercept of the log–log regression equation.

Species accumulation curves also were modeled using a logistic function (Equation (5)) between the number of species and number of patches and the number of neighborhoods [41] because the logistic curves could be used to test whether the curves reached an asymptote:

where S′ prime is the cumulative number of species, N is the cumulative number of patches or the cumulative number of neighborhoods, a represents the upper asymptote of the curves, and k and b are parameters that both affect the curvature of the curves. The minimal number of patches and the minimal number of neighborhoods were estimated at the point on the logistic curves where 90% of the theoretical species pool in the patch and neighborhood were found.

2.6. Data Analysis

Plant diversity indices were calculated using the diversity function in the “vegan” package in R software [43]. Our data were hierarchical with patches “nested” within neighborhoods. Hence, we performed hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) using HLM software version 6 [44] to test whether there were significant differences in the plant diversity indices between neighborhoods and to decompose the variance in the plant diversity indices into between patches within neighborhoods and between neighborhoods [45].

The relationship between the number of species and the patch area was fitted with SPSS 22.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Species accumulation curves were fitted using OriginPro software (OriginLab, OriginPro 2018, Northampton, MA, USA) with a repeated and random ordering of all the samples [42,46] in R version 3.3.1 [47]. We conducted t-tests to compare the slopes of the species–area accumulation curves between patches within neighborhoods and between neighborhoods with SPSS 22.0 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Species Diversity at Neighborhood Scale

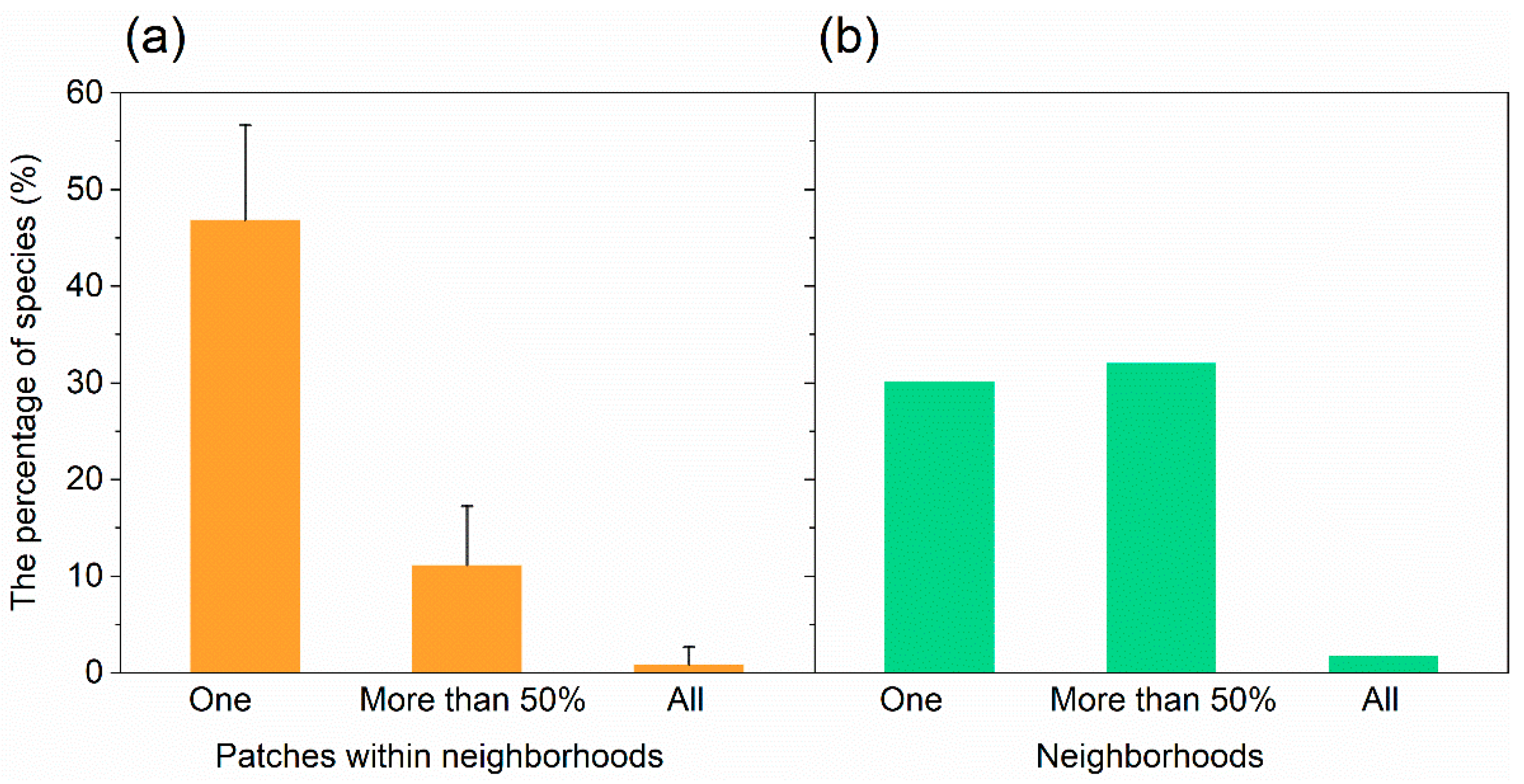

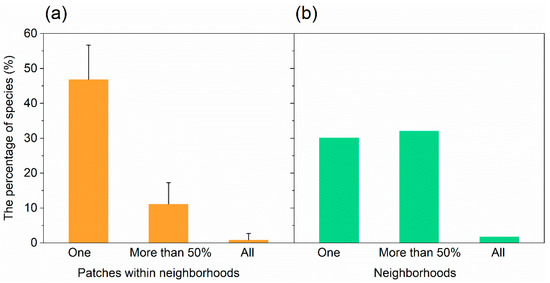

Within a neighborhood, 46.9% of the species occurred only in one patch, 11.2% in more than half of the patches, and 0.89% in all investigated patches (Figure 2a). For one patch, the average species number was 6.11 for trees, 3.84 for shrubs, and 8.00 for herbs. The average Gleason index was 0.95 for trees, 0.60 for shrubs, and 1.27 for herbs. The average Shannon index was 1.35 for trees, 0.95 for shrubs, and 1.32 for herbs (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The percentage of species were found (a) in one, more than 50% and all patches within neighborhoods and (b) in one, more than 50% and all neighborhoods investigated.

Table 2.

Diversity index statistics within and between neighborhoods.

For one neighborhood, the average total number of species was 87, with 30.5 for trees, 18.8 for shrubs, and 31.9 for herbs (Table 2). The average Gleason index was 3.33 for trees, 2.07 for shrubs, and 3.47 for herbs. The average Shannon index was 2.83 for trees, 2.20 for shrubs, and 2.58 for herbs (Table 2).

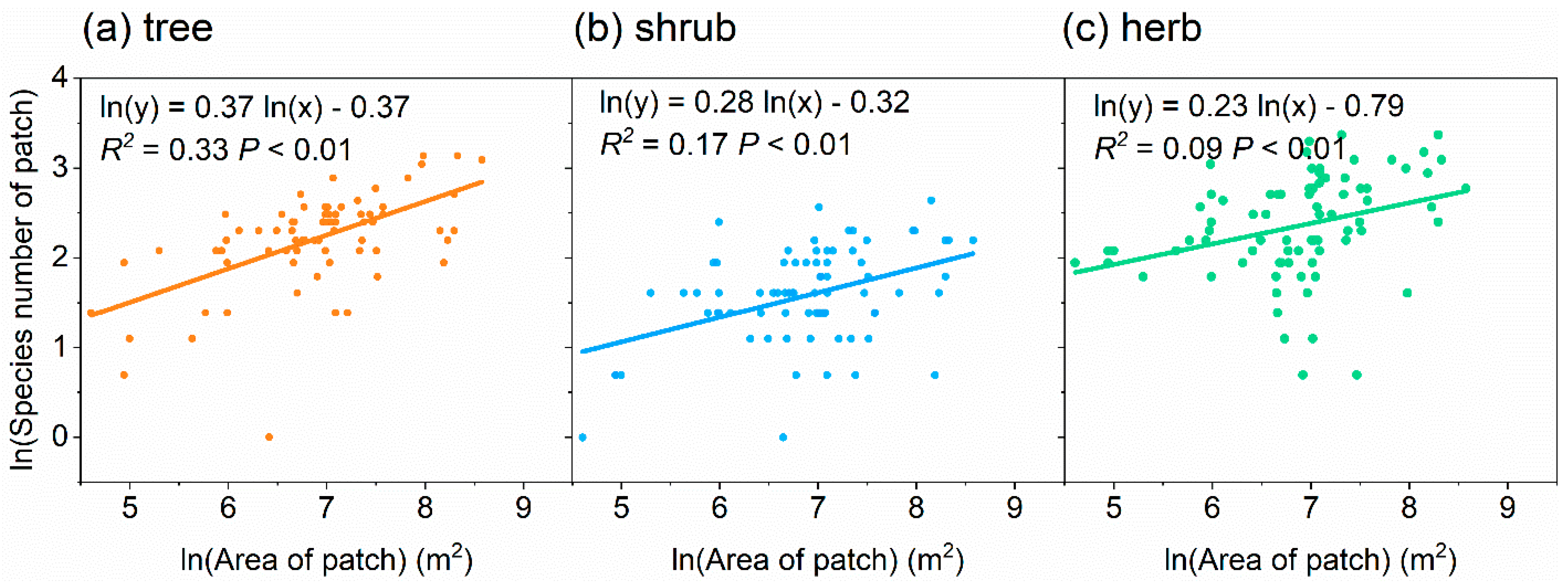

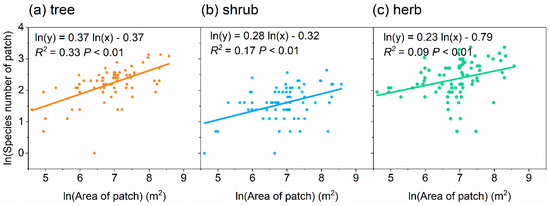

The number of species per patch for trees, shrubs, and herbs increased significantly and logarithmically with the patch area (Figure 3). The number of species–patch area relationship had a lower slope (0.23, R2 = 0.09) for herbs compared with trees (0.37, R2 = 0.33) and shrubs (0.28, R2 = 0.17) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Relationships between patch area and number of species of the patch for trees (a), shrubs (b) and herbs (c).

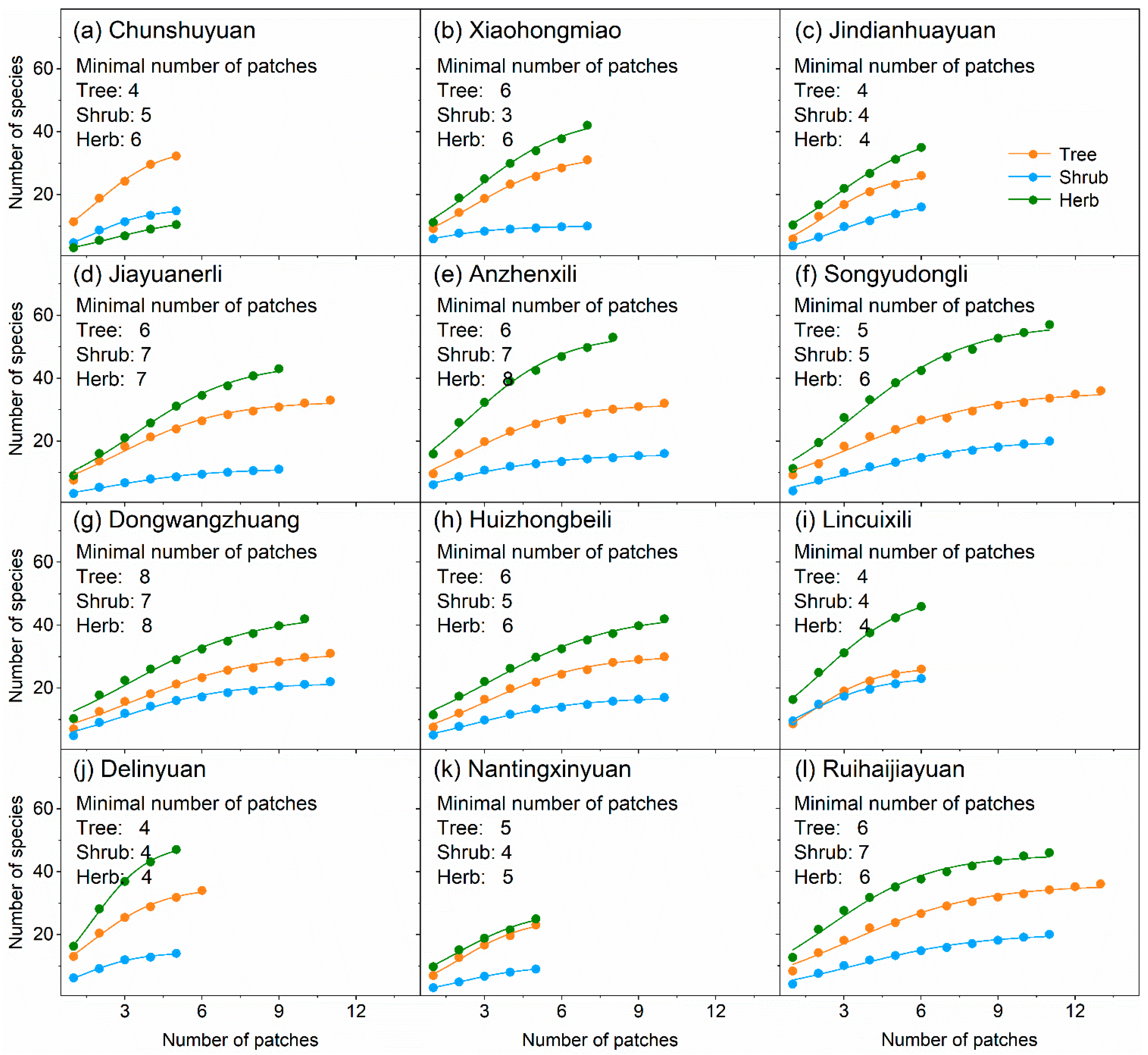

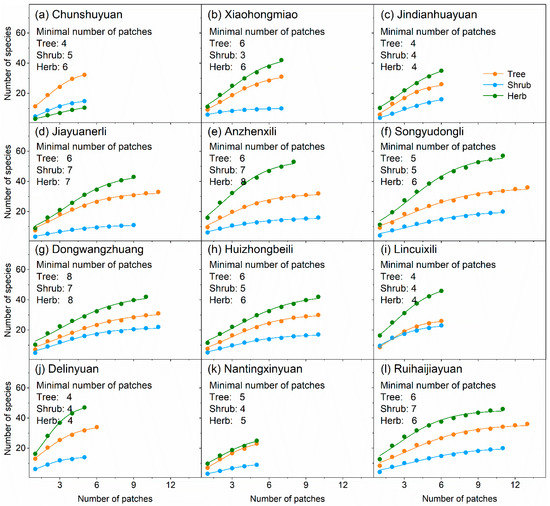

The number of species for trees, shrubs, and herbs increased significantly and logistically with the number of patches within each neighborhood (Figure 4). We estimated that the minimum number of patches required for investigating plant diversity at the neighborhood scale ranged between 4–8 for trees, 3–7 for shrubs, and 4–8 for herbs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Number of species-number of patches accumulation curves based on logistic function. Adjusted R2 for all curves was more than 0.98. F value for all curves was extremely significant.

3.2. Differences in Plant Diversity between Neighborhoods

In the 12 neighborhoods, we recorded 218 species (Appendix A Table A1) belonging to 153 genera and 68 families. The most common plant species belonged to Rosaceae (including 27 species), followed by Asteraceae (24), Oleaceae (11), and Poaceae (10). The genera with the highest number of species were Prunus, followed by Populus, Malus, and Viola. Trees, shrubs (including lianas), and herbs comprised 72 (33.03% of all species), 46 (21.10%), and 100 (45.87%) species, respectively. For trees, shrubs, and herbs, there were 36, 16, and 53 native species, 22, 18, and 13 alien species from other areas of China, 14, 11, and 25 alien species from abroad, and 0, 1, and 9 invasive species, respectively.

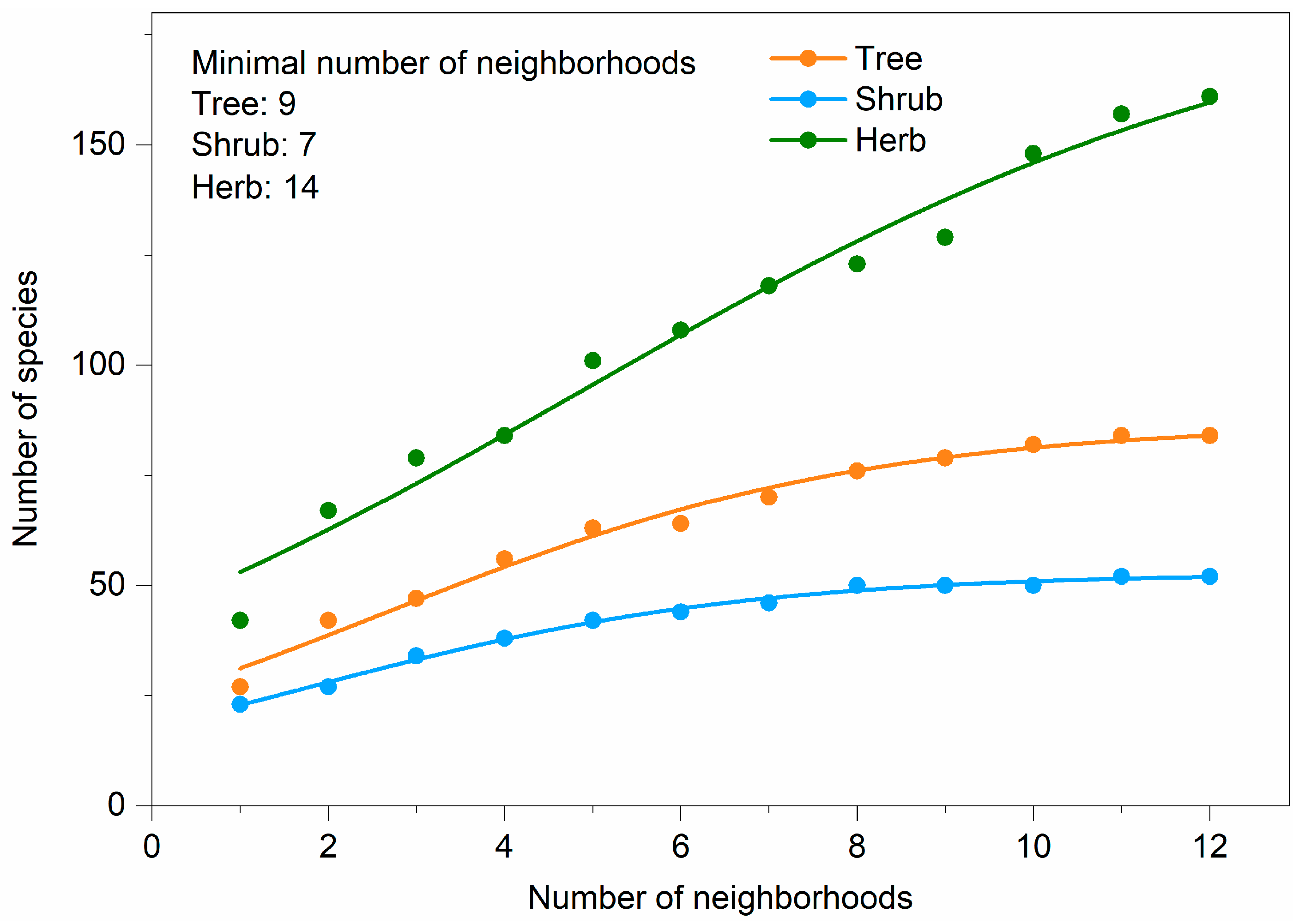

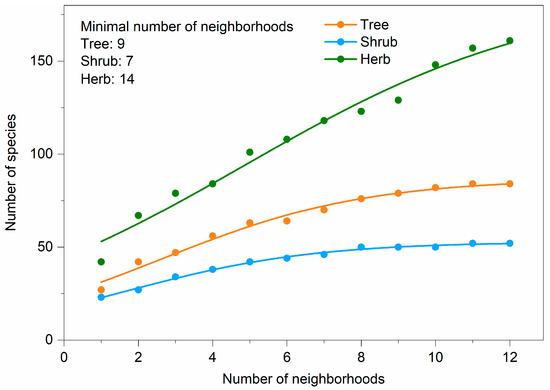

We found that there were 66 species (30.3% of all species) occurring in just one neighborhood, and 70 species (32.1%) occurring simultaneously in more than half of all the neighborhoods (Figure 2b). The most common species that occurred in all neighborhoods were Ginkgo biloba L., Toona sinensis (A. Juss.) Roem., Euonymus japonicus Thunb., and Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. The number of species increased significantly and logarithmically with the number of neighborhoods (Figure 5). We estimated that the minimum number of neighborhoods required for sampling was 9 for trees, 7 for shrubs, and 14 for herbs (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Number of species—number of neighborhoods accumulation curves based on logistic function. Adjusted R2 for all curves was more than 0.97. F value for all curves was extremely significant.

3.3. Comparison of the Variations in Plant Diversity within and between Neighborhoods

Based on the power function, the slopes of accumulation curves for species number–area of the green patches surveyed ranged from 0.49 to 0.81 for trees, from 0.27 to 0.79 for shrubs, and from 0.53 to 0.76 for herbs, and were significantly higher than the slopes for species number–area of the neighborhood surveyed (for trees, t = 9.34, p < 0.01; for shrubs, t = 2.23, p < 0.05; for herbs, t = 4.75, p < 0.01). These results indicated that the species turnover between patches was significantly stronger than that between neighborhoods.

HLM detected significant differences in the shrub and herb diversity indices between neighborhoods (p < 0.01), but not between the tree diversity indices (p > 0.05, Table 3). The percentage of the variance of plant diversity within neighborhoods was higher than that between neighborhoods, ranging from 99.94% to 99.98% for trees, from 54.34% to 81.20% for shrubs, and from 52.33% to 72.83% for herbs (Table 3), indicating that the heterogeneity of plant diversity within neighborhoods was higher than that between neighborhoods.

Table 3.

Variance in diversity index within and between neighborhoods based on hierarchical linear modeling.

4. Discussion

4.1. Homogeneity of Plant Species Compositions and Diversity between Neighborhoods

In this study, we found that Rosaceae, Asteraceae, Oleaceae, and Poaceae were the most common families in the 12 neighborhoods investigated. Similarly, Song [27] found that these families were the most common families in 92 neighborhoods in Beijing. Zhao, et al. [6] also found that these four families and Liliaceae were the most common families in six types of green spaces in Beijing comprising park green spaces, protection green spaces, institutional green spaces, street green spaces, vacant land spaces, and residential green spaces.

Plant assemblages are similar between neighborhoods [15,17,20]. In the present study, 32% of the total species detected occurred in more than half of all the neighborhoods (Figure 2b). Similarly, in previous studies, 10% of the species occurred in more than 40% of all residential yards (424 yards) along the Río Piedras watershed in Puerto Rico [1], and 18% of the species were shared among residential lawns (174 lawns) in the USA [16]. We found that Ginkgo biloba L., Toona sinensis (A. Juss.) Roem., Euonymus japonicus Thunb., and Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. occurred in all neighborhoods investigated. Song [27] also reported that Ginkgo biloba and Euonymus japonicus occurred in more than 60% of all the quadrats (345 quadrats) sampled in neighborhoods of Beijing. Certain species occur simultaneously in different neighborhoods [1,16,27], possibly because most of the residents living in different neighborhoods prefer species with brightly colored flowers or leaves, those that provide food or medical materials, or plants that are easy to manage due to their resistance to adverse environments [14,17,18,20,23].

The level of the homogenization of plant diversity varies among habitat types [48,49]. Green spaces in neighborhoods might harbor more similar plant diversity compared with other habitats, such as wasteland with little disturbance and those abandoned for many years [49]. The following three causes might contribute to these similarities. First, similarities in plant diversity may be attributed to the management and preferences of residents. Residents with similar lifestyle characteristics (e.g., age, socioeconomic status, life stage, and ethnicity) and social preferences (e.g., values and interests) across different neighborhoods have similar landscaping preferences and practices. For example, there is little variation in fertilization regardless of the differences in climate or other environmental conditions [17]. Residents also prefer trees to herbs as well as plants with ornamental traits compared with plants lacking these traits [18,23]. Second, similarities in plant diversity may be related to the planning and development of neighborhoods. Neighborhoods are usually implemented by local real estate developers to meet the similar requirements imposed by the government and city dwellers, and thus, the neighborhoods comprise pavements, housings, grasses, shrubs, and trees with similar landscape structures and available habitats for plants [3,19]. Third, similarities in plant diversity may be related to the microenvironment. The soil in residential landscapes is often lacking in nutrients with high alkalinity. The microclimate is also similar in residential ecosystems, especially the high air temperatures caused by the urban heat island effect [14,20]. Thus, the similar microenvironment may act as a key filter to ensure that residential flora is under similar effects imposed by natural selection, and thus homogenization can occur [50].

The spatial homogenization of plant species compositions between neighborhoods depends on the different plant life forms. The increase in the number of species with the number of neighborhoods saturated for trees and shrubs but not for herbs (Figure 5) because of the following reasons: (1) the total numbers of tree and shrub species are lower than those of herb species (Figure 4 and Figure 5); (2) herbs with smaller sizes require less space to grow than trees and shrubs, and they are also disturbed less by human activities [23,51]; and (3) trees and shrubs are mostly planted in special patches by managers, who are highly focused on landscape architecture for aesthetic and recreational values rather than their intrinsic ecological value, whereas herbs are more likely to disperse and grow spontaneously within various patches [52].

4.2. Heterogeneity of Plant Species Compositions and Diversity within Neighborhoods

The green patches within neighborhoods vary in terms of their isolation, size, and ecosystem function, thereby leading to variations in plant migration, resource availability for plants, and the ecosystem services provided by plants [1,26]. Hence, the plant species compositions can vary among patches [1,25]. In the present study, 46.9% of the species in each neighborhood occurred in only a single patch (Figure 2a) and the number of species increased logistically with the number of patches (Figure 4).

Neighborhoods provide green spaces for residents to enjoy [2,19]. Neighborhoods generally contain many small green patches with different features in order to provide multiple services for residents and to adapt to the altered habitat due to the influence of roads, buildings, and pre-existing physical conditions [1,2,50]. These green patches differ in terms of their plant diversity, where they range from patches with a few plant species (e.g., newly built patches) to those with high plant diversity (e.g., remnant patches of native habitat). Thus, the plant diversity within neighborhoods is spatially heterogeneous.

The variations in shrub and herb diversity between neighborhoods were significant in the present study, but the contributions of the variations in plant diversity for trees, shrubs, and herbs to the total variation were higher between patches within neighborhoods than those between neighborhoods (Table 3). Similar differences in plant diversity were found previously where the within-yard variation in the species compositions was higher than that among yards [1]. These results can probably be explained by the similar green space configurations between neighborhoods [27], although there may be differences in terms of isolation, size, and the functions of green spaces within neighborhoods [1,26,27]. Designers and managers often prefer to grow different plants in each patch to increase the number of ecosystem services provided by green spaces [1,27,53]. Thus, understanding the heterogeneity of plant diversity within neighborhoods is essential for plant diversity assessments, landscape design, and managing and maintaining neighborhoods.

4.3. Effect of Patch Area on the Number of Species

The importance of patch characteristics, such as the patch area and patch isolation, for plant composition and diversity has been highlighted in previous theoretical and empirical ecological studies [54,55,56]. The number of species was dependent on the patch area in the present study (Figure 3). Similar relationships between the number of plant species and the area of urban forest patches were obtained in the Twin Cities of Minnesota, USA [57], Hannover in Germany, Haifa in Israel [43,58], and in the northern part of Belgium [59].

Angold, et al. [60] suggested that the patch size is positively correlated with the diversity and richness of patches. Thus, small patches harbor fewer species than large patches, probably because small patches contain less diverse habitats or the populations in small patches may be influenced by density-dependent, stochastic extinction processes [45,61].

The relationship between the species number and patch area was weaker for herbs than trees and shrubs (Figure 3), possibly because herbs are more sensitive to unpredictable disturbances by residents and they regenerate more readily [49,62]. The species–area curves is universal and suitable for urban neighborhoods, and it can be constructed to describe and predict the relationship between the number of species and patch size based on knowledge of the pre-disturbance species richness [58].

4.4. Implications for Plant Diversity Surveys

Previous investigations of residential plants [12,19,50] rarely considered the allocation of efforts to surveys within and between neighborhoods. In Beijing, we surveyed 12 neighborhoods (the average survey area in each neighborhood was 12,495 m2), whereas 32 (2400 m2) were sampled by Lang, et al. [63], 92 (400 m2) were sampled by Song [27], and 83 (1002 m2) were sampled by Wang, et al. [5]. We recorded 218 species, whereas 273 were recorded by Lang, et al. [63], 315 were recorded by Song [27], and 369 were recorded by Wang, et al. [5]. In the present study, we constructed the accumulation curves for the numbers of species versus the number of patches and neighborhoods, before estimating the number of patches within neighborhoods and the number of neighborhoods that need to be sampled. Due to the high similarity of the species compositions between neighborhoods (Figure 2b and Figure 5), it would be useful to investigate more patches within neighborhoods to assess the plant diversity in cities, which may reduce the time and money spent traveling to and from neighborhoods as well as reducing the effort required to access neighborhoods.

Comprehensive investigations of all the green patches in a neighborhood would be the ideal approach, but the cost could be prohibitive. The numbers of patches sampled previously within neighborhoods ranged from one to 10 or more, and the areas from 100 m2 to 4000 m2 or more [5,11,64,65,66]. A low sampling intensity might lead to a high likelihood of missing rare or even moderately rare species in a neighborhood [67]. By contrast, a high sampling intensity might incur high costs in terms of time, energy, and money. In the present study, we found that the spatial heterogeneity of the plant diversity was higher between green patches within neighborhoods than between neighborhoods (Table 3), thereby suggesting the possibility of reducing the total effort if adequate sampling is conducted in each neighborhood investigated.

Given the important effects of the specific survey methods employed when assessing plant diversity [42,67], it is essential to identify an adequate sampling approach in terms of balancing the data quality and the amount of money and time available, as well as considering the characteristics of species compositions and plant diversity at the patch and neighborhood scales.

5. Conclusions

In this study, based on intensive investigations of 12 neighborhoods in Beijing, we analyzed the variations in the plant species compositions and diversity within and between neighborhoods. Neighborhoods shared more plant species with ornamental, medicinal, or edible value and/or diverse ecological niches than patches. The homogeneity of the species composition and plant diversity was lower within neighborhoods than between neighborhoods, thereby suggesting that more effort should be made to increase the sampling number or area of patches within neighborhoods. We tentatively recommended the numbers of patches that should be sampled both within neighborhoods and between neighborhoods to assess the plant diversity in urban areas based on species–patch and –neighborhood accumulation curves established in our study based on Beijing. However, in future research, it will be important to balance the number of neighborhoods sampled and the numbers of patches sampled within neighborhoods under the constraints of limited resources, as well as considering additional factors that might influence the heterogeneity of plant compositions and diversity when designing urban biodiversity surveys.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., Z.O. and X.W.; Funding acquisition, Z.O. and X.W.; Investigation, Y.S. and P.G.; Methodology, Y.S., C.G. and B.C.; Visualization, Y.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.S.; Writing—review & editing, Y.S. and X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFE0127700) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71533005 and 41571053).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their valuable comments, which improved the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The list of the collected species.

Table A1.

The list of the collected species.

| Scientific Name | Life Form | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Sabina chinensis (L.) Ant. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Prunus cerasifera Ehrhar f. atropurpurea (Jacq.) Rehd. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Magnolia denudata Desr. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Ginkgo biloba L. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Toona sinensis (A. Juss.) Roem. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Malus × micromalus Makino | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Amygdalus persica L. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Zanthoxylum bungeanum Maxim. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Juglans regia | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Juniperus formosana Hayata | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Paulownia tomentosa (Thunb.) Steud. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Amygdalus persica L. var. persica f. atropurpurea Schneid. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Albizia julibrissin Durazz. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Prunus salicina Lindl. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Eucommia ulmoides Oliver | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Pinus bungeana Zucc. ex Endl. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Fontanesia fortunei Carr. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Phyllostachys propinqua McClure | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Pinus armandii Franch. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Ligustrum lucidum Ait. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Armeniaca vulgaris Lam. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Robinia pseudoacacia | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Cedrus deodara (Roxb.) G. Don | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Platanus occidentalis L. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Cerasus serrulata (Lindl.) G. Don ex London var. lannesiana (Carr.) Makino | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Fraxinus pennsylvanica Marsh. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Platanus orientalis L. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Punica granatum L. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Populus × canadensis Moench | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Cerasus yedoensis (Matsum.) Yu et Li | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Fraxinus americana Linn. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Platanus acerifolia Willd. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Malus pumila Mill. | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Populus alba | Tree | Alien species from abroad |

| Acer truncatum Bunge | Tree | Native species |

| Ulmus pumila L. | Tree | Native species |

| Populus tomentosa | Tree | Native species |

| Salix matsudana var. matsudana f. pendula Schneid. | Tree | Native species |

| Diospyros kaki Thunb. | Tree | Native species |

| Crataegus pinnatifida | Tree | Native species |

| Amygdalus davidiana (Carrière) de Vos ex Henry | Tree | Native species |

| Morus alba L. | Tree | Native species |

| Koelreuteria paniculata Laxm. | Tree | Native species |

| Sophora japonica Linn. var. japonica f. pendula Hort. | Tree | Native species |

| Malus spectabilis (Ait.) Borkh. | Tree | Native species |

| Sophora japonica Linn. | Tree | Native species |

| Broussonetia papyrifera (Linn.) L’Hér. ex Vent. | Tree | Native species |

| Syringa pekinensis Rupr. | Tree | Native species |

| Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle | Tree | Native species |

| Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco | Tree | Native species |

| Amygdalus persica L. var. persica f. duplex Rehd. | Tree | Native species |

| Fraxinus chinensis Roxb. | Tree | Native species |

| Salix babylonica | Tree | Native species |

| Salix matsudana | Tree | Native species |

| Diospyros lotus L. | Tree | Native species |

| Pyrus ussuriensis Maxim. | Tree | Native species |

| Pinus tabuliformis Carr. | Tree | Native species |

| Amygdalus triloba (Lindl.) Ricker | Tree | Native species |

| Ziziphus jujuba Mill. var. spinosa (Bunge) Hu ex H. F. Chow | Tree | Native species |

| Ziziphus jujuba Mill. | Tree | Native species |

| Picea wilsonii Mast. | Tree | Native species |

| Picea meyeri Rehd. et Wils. | Tree | Native species |

| Larix principis-rupprechtii Mayr | Tree | Native species |

| Ulmus pumila L. ‘Tenue’ | Tree | Native species |

| Syringa oblata Lindl. | Tree | Native species |

| Acer palmatum Thunb. | Tree | Native species |

| Cotinus coggygria Scop. | Tree | Native species |

| Populus hopeiensis | Tree | Native species |

| Firmiana platanifolia (L. f.) Marsili | Tree | Native species |

| Tamarix chinensis Lour. | Tree | Native species |

| Juglans mandshurica | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Malus spectabilis (Ait.) Borkh. var. riversii (Kirchn.) Rehd. | Tree | Alien species from other area of China |

| Lagerstroemia indica L. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Jasminum nudiflorum Lindl. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Hibiscus syriacus Linn. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Sorbaria sorbifolia (L.) A. Br. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Kerria japonica (L.) DC. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Buxus sinica (Rehd. et Wils.) Cheng subsp. sinica var. parvifolia M. Cheng | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Cercis chinensis Bunge | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Viburnum opulus Linn. var. calvescens (Rehd.) Hara | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Buxus sinica (Rehd. et Wils.) Cheng | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Paeonia suffruticosa Andr. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Philadelphus incanus Koehne | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Spiraea vanhouttei (Briot) Zabel | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Ligustrum quihoui Carr. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Berberis thunbergii var. atropurpurea Chenault | Shrub | Alien species from abroad |

| Ficus carica Linn. | Shrub | Alien species from abroad |

| Buxus megistophylla Levl. | Shrub | Alien species from abroad |

| Rosa multiflora Thunb. | Shrub | Alien species from abroad |

| Sabina procumbens (Endl.) Iwata et Kusaka | Shrub | Alien species from abroad |

| Ligustrum × vicaryi Rehder | Shrub | Alien species from abroad |

| Lonicera maackii (Rupr.) Maxim. | Shrub | Native species |

| Forsythia suspensa (Thunb.) Vahl | Shrub | Native species |

| Rosa chinensis Jacq. | Shrub | Native species |

| Weigela florida (Bunge) A. DC. | Shrub | Native species |

| Rosa xanthina Lindl. | Shrub | Native species |

| Sorbaria kirilowii (Regel) Maxim. | Shrub | Native species |

| Swida alba | Shrub | Native species |

| Lycium chinense Mill. | Shrub | Native species |

| Lespedeza bicolor Turcz. | Shrub | Native species |

| Sambucus williamsii Hance | Shrub | Native species |

| Sabina vulgaris Ant. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Kerria japonica (L.) DC. f. pleniflora (Witte) Rehd. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Hibiscus rosa-sinensis Linn. | Shrub | Alien species from other area of China |

| Dioscorea nipponica Makino | Liana | Alien species from other area of China |

| Parthenocissus quinquefolia (L.) Planch. | Liana | Alien species from abroad |

| Luffa cylindrica (L.) Roem. | Liana | Alien species from abroad |

| Pharbitis nil (L.) Choisy | Liana | Invasive species |

| Vitis vinifera L. | Liana | Alien species from abroad |

| Phaseolus vulgaris Linn. | Liana | Alien species from abroad |

| Cucurbita moschata (Duch. ex Lam.) Duch. ex Poiret | Liana | Alien species from abroad |

| Metaplexis japonica (Thunb.) Makino | Liana | Native species |

| Rubia cordifolia L. | Liana | Native species |

| Humulus scandens | Liana | Native species |

| Cynanchum chinense R. Br. | Liana | Native species |

| Lonicera japonica Thunb. | Liana | Native species |

| Clematis intricata Bunge | Liana | Native species |

| Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Thunb.) Makino | Liana | Alien species from other area of China |

| Perilla frutescens (L.) Britt. | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Teucrium tsinlingense C. Y. Wu et S. Chow var. porphyreum C. Y. Wu et S. Chow | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Iris tectorum | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Hemerocallis fulva (L.) L. | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Impatiens balsamina L. | Herb | Invasive species |

| Hylotelephium erythrostictum (Miq.) H. Ohba | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Ixeris denticulata (Houtt.) Stebb. | Herb | Native species |

| Ixeris polycephala Cass. | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Viola verecunda A. Gray | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Calystegia sepium (L.) R. Br. | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Urtica fissa E. Pritz. | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Malva crispa Linn. | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Cleome spinosa Jacq. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Mirabilis jalapa L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Phytolacca americana L. | Herb | Invasive species |

| Pharbitis hederacea (L.) Choisy | Herb | Invasive species |

| Helianthus tuberosus L. | Herb | Invasive species |

| Glechoma longituba (Nakai) Kupr | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Cosmos bipinnata Cav. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Amaranthus retroflexus | Herb | Invasive species |

| Capsicum annuum L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Amaranthus viridis | Herb | Invasive species |

| Chloris virgata Sw. | Herb | Invasive species |

| Trifolium repens L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Euphorbia maculata L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Aster subulatus Michx. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Galinsoga parviflora Cav. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Viola tricolor L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Datura stramonium Linn. | Herb | Invasive species |

| Pharbitis purpurea (L.) Voisgt | Herb | Invasive species |

| Solanum melongena L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Symphyotrichum novi-belgii (L.) G.L.Nesom | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Rudbeckia hirta L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Portulaca grandiflora Hook. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Dahlia pinnata Cav. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Lactuca sativa L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Helianthus annuus L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Physostegia virginiana Benth. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Echinacea purpurea (Linn.) Moench | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Oxalis corniculata L. | Herb | Native species |

| Viola philippica | Herb | Native species |

| Hosta plantaginea (Lam.) Aschers. | Herb | Native species |

| Leonurus artemisia (Laur.) S. Y. Hu | Herb | Native species |

| Acalypha australis L. | Herb | Native species |

| Duchesnea indica (Andr.) Focke | Herb | Native species |

| Taraxacum mongolicum Hand.-Mazz. | Herb | Native species |

| Euphorbia humifusa Willd. ex Schlecht. | Herb | Native species |

| Ophiopogon japonicus | Herb | Native species |

| Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop. | Herb | Native species |

| Kalimeris indica (L.) Sch. -Bip. | Herb | Native species |

| Portulaca oleracea L. | Herb | Native species |

| Solanum nigrum L. | Herb | Native species |

| Chenopodium glaucum L. | Herb | Native species |

| Arthraxon hispidus (Thunb.) Makino | Herb | Native species |

| Zoysia japonica Steud. | Herb | Native species |

| Setaria viridis (L.) Beauv. | Herb | Native species |

| Trigonotis peduncularis (Trev.) Benth. ex Baker et Moore | Herb | Native species |

| Calystegia hederacea Wall.ex.Roxb. | Herb | Native species |

| Plantago asiatica L. | Herb | Native species |

| Mentha haplocalyx Briq. | Herb | Native species |

| Pinellia ternata | Herb | Native species |

| Chenopodium album L. | Herb | Native species |

| Tribulus terrester L. | Herb | Native species |

| Bidens pilosa L. | Herb | Native species |

| Artemisia annua | Herb | Native species |

| Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaetn.) Libosch. ex Fisch. et Mey. | Herb | Native species |

| Potentilla chinensis Ser. | Herb | Native species |

| Commelina communis | Herb | Native species |

| Inula japonica Thunb. | Herb | Native species |

| Myosoton aquaticum (L.) Moench | Herb | Native species |

| Lythrum salicaria L. | Herb | Native species |

| Oplismenus undulatifolius (Arduino) Beauv. | Herb | Native species |

| Aster tataricus L. f. | Herb | Native species |

| Polygonum aviculare L. | Herb | Native species |

| Convolvulus arvensis L. | Herb | Native species |

| Poa annua L. | Herb | Native species |

| Paeonia lactiflora Pall. | Herb | Native species |

| Dendranthema morifolium (Ramat.) Tzvel. | Herb | Native species |

| Melica scabrosa Trin. | Herb | Native species |

| Viola pekinensis | Herb | Native species |

| Potentilla supina L. | Herb | Native species |

| Cyperus nipponicus Franch. et Savat. | Herb | Native species |

| Cirsium setosum (Willd.) MB. | Herb | Native species |

| Iris lactea Pall. var. chinensis (Fisch.) Koidz. | Herb | Native species |

| Cyperus fuscus L. | Herb | Native species |

| Achyranthes bidentata Blume | Herb | Native species |

| Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A. DC. | Herb | Native species |

| Belamcanda chinensis (L.) Redouté | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn. | Herb | Native species |

| Allium tuberosum | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Hylotelephium pallescens (Freyn) H. Ohba | Herb | Native species |

| Ixeridium sonchifolium (Maxim.) Shih | Herb | Native species |

| Artemisia argyi Levl. et Van. | Herb | Native species |

| Ophiopogon bodinieri | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Erigeron annuus (L.) Pers. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Axyris amaranthoides L. | Herb | Alien species from other area of China |

| Conyza canadensis (L.) Cronq. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Beta vulgaris L. var. cicla L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Canna indica L. | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

| Amaranthus tricolor | Herb | Alien species from abroad |

Figure A1.

The location of patches investigated in each neighborhood. The red stars indicate the location of patches. The dotted blue lines indicate the boundaries of the neighborhoods.

Figure A1.

The location of patches investigated in each neighborhood. The red stars indicate the location of patches. The dotted blue lines indicate the boundaries of the neighborhoods.

References

- Vila-Ruiz, C.; Meléndez-Ackerman, E.; Santiago-Bartolomei, R.; Garcia-Montiel, D.; Lastra, L.; Figuerola, C.; Fumero-Caban, J. Plant species richness and abundance in residential yards across a tropical watershed: Implications for urban sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.W.; Jenerette, G.D. Biodiversity and direct ecosystem service regulation in the community gardens of Los Angeles, CA. Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 30, 637–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization, Biodiversity, and Conservation: The impacts of urbanization on native species are poorly studied, but educating a highly urbanized human population about these impacts can greatly improve species conservation in all ecosystems. Bioscience 2002, 52, 883–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaston, K.J.; Warren, P.H.; Thompson, K.; Smith, R.M. Urban domestic gardens (IV): The extent of the resource and its associated features. Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 3327–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.F.; Qureshi, S.; Knapp, S.; Friedman, C.R.; Hubacek, K. A basic assessment of residential plant diversity and its ecosystem services and disservices in Beijing, China. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 64, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Zhou, W.; Wang, X.; Xu, W.; Ni, Y. Plant species composition in green spaces within the built-up areas of Beijing, China. Plant Ecol. 2010, 209, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Nakagoshi, N. Spatial-temporal gradient analysis of urban green spaces in Jinan, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, M.F.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; MacIvor, J.S.; Nilon, C.H.; Vargo, T. Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Species Composition and Spatial Distribution of Urban Plants within the Built-Up Areas of Beijing, China. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2010. (In Chinese, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Su, Y.; Wan, W.; Liu, W.; Zhang, H.; Sun, X.; Ouyang, Z.; Wang, X. Urban plant diversity in relation to land use types in built-up areas of Beijing. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinzig, A.P.; Warren, P.; Martin, C.; Hope, D.; Katti, M. The effects of human socioeconomic status and cultural characteristics on urban patterns of biodiversity. Ecol. Soc. 2005, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, D.; Gries, C.; Zhu, W.X.; Fagan, W.F.; Redman, C.L.; Grimm, N.B.; Nelson, A.L.; Martin, C.; Kinzig, A. Socioeconomics drive urban plant diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8788–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, U. Landscape structure, landscape metrics and biodiversity. Living Rev. Landsc. Res. 2011, 5, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groffman, P.M.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Bettez, N.D.; Grove, J.M.; Hall, S.J.; Heffernan, J.B.; Hobbie, S.E.; Larson, K.L.; Morse, J.L.; Neill, C.; et al. Ecological homogenization of urban USA. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearse, W.D.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Hobbie, S.E.; Avolio, M.; Bettez, N.; Chowdhury, R.R.; Groffman, P.M.; Grove, M.; Hall, S.J.; Heffernan, J.B.; et al. Ecological homogenisation in North American urban yards: Vegetation diversity, composition, and structure. bioRxiv 2016, 061937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.M.; Neill, C.; Groffman, P.M.; Avolio, M.; Bettez, N.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Chowdhury, R.R.; Darling, L.; Grove, M.; Hall, S.J.; et al. Continental-scale homogenization of residential lawn plant communities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsky, C.; Grove, J.M.; Knudson, C.; Groffman, P.M.; Bettez, N.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Hall, S.J.; Heffernan, J.B.; Hobbie, S.E.; Larson, K.L.; et al. Assessing the homogenization of urban land management with an application to US residential lawn care. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4432–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.S.G.; Hahs, A.K.; Vesk, P.A. Urbanisation, plant traits and the composition of urban floras. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2015, 17, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groffman, P.M.; Avolio, M.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Bettez, N.D.; Grove, J.M.; Hall, S.J.; Hobbie, S.E.; Larson, K.L.; Lerman, S.B.; Locke, D.H.; et al. Ecological homogenization of residential macrosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 127, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoncini, A.P.; Machon, N.; Pavoine, S.; Muratet, A. Local gardening practices shape urban lawn floristic communities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.H.; Ignatieva, M.E.; Meurk, C.D.; Buckley, H.; Horne, B.; Braddick, T. Urban Biotopes of Aotearoa New Zealand (URBANZ)(I): Composition and diversity of temperate urban lawns in Christchurch. Urban Ecosyst. 2009, 12, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.S.; Grimm, N.B.; Briggs, J.M.; Gries, C.; Dugan, L. Effects of urbanization on plant species diversity in central Arizona. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; La Sorte, F.A.; Pyšek, P.; Yan, P.; Nowak, D.; McBride, J. The compositional similarity of urban forests among the world’s cities is scale dependent. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2015, 24, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaire, J.A.; Westphal, L.M.; Minor, E.S. Different social drivers, including perceptions of urban wildlife, explain the ecological resources in residential landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faeth, S.H.; Bang, C.; Saari, S. Urban biodiversity: Patterns and mechanisms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1223, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, A.C. Study on Plant Diversity and Landscape of Residential Green Area in Beijing Built-Up District. Master’s Thesis, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China, 2014. (In Chinese, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Qi, G.; Knapp, B.O. Topography affects tree species distribution and biomass variation in a warm temperate, secondary forest. Forests 2019, 10, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Fang, C.; Lin, G.; Gong, H.; Qiao, B. Tempo-spatial patterns of land use changes ansd urban development in globalizing China: A study of Beijing. Sensors 2007, 7, 2881–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, Y.; Tian, L. Identifying the urban-rural fringe using wavelet transform and kernel density estimation: A case study in Beijing City, China. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2016, 83, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.L. Quantifying the Fine-Scale Spatiotemporal Pattern of Vegetation Cover and Its Socioeconomic Drivers in Beijing Urban Areas. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2016. (In Chinese, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W.; Zheng, S.; Geltner, D.M.; Wang, R. The Housing Market Effects of Local Home Purchase Restrictions: Evidence from Beijing. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2016, 55, 288–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.M.; Li, S.M. Commercial housing affordability in Beijing, 1992–2002. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, F.; Wu, Y. One decade of urban housing reform in China: Urban housing price dynamics and the role of migration and urbanization, 1995–2005. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Cui, Y.; Li, N.; Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Run, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, G.; Dong, J. Human activities enhance radiation forcing through surface albedo associated with vegetation in Beijing. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora of China. Compilation Committee of the Flora of China, 1959–2004; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Xing, Q.; Yin, Z.; Jiang, X. Beijing Flora, 3rd ed.; Beijing Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1993. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Legendre, P.; De Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: Dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gleason, H.A. On the relation between species and area. Ecology 1922, 3, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1984, 27, 379–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheiner, S.M. Six Types of Species-Area Curves. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2003, 12, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Xu, W.; Zheng, H.; Meng, X. Sampling adequacy estimation for plant species composition by accumulation curves—A case study of urban vegetation in Beijing, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.; Wagner, H. Vegan: Community Ecology Package; R Package Version, 2.0-2; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush, S.W. HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling; Scientific Software International: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Woltman, H.; Feldstain, A.; MacKay, J.C.; Rocchi, M. An introduction to hierarchical linear modeling. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2012, 8, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotelli, N.J.; Colwell, R.K. Quantifying biodiversity: Procedures and pitfalls in the measurement and comparison of species richness. Ecol. Lett. 2001, 4, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; The R Foundation: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, H.; Guo, Q. Linking biotic homogenization to habitat type, invasiveness and growth form of naturalized alien plants in North America. Divers. Distrib. 2010, 16, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lososová, Z.; Chytrý, M.; Tichý, L.; Danihelka, J.; Fajmon, K.; Hájek, O.; Kintrová, K.; Láníková, D.; Otýpková, Z.; Řehořek, V. Biotic homogenization of Central European urban floras depends on residence time of alien species and habitat types. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 145, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.S.; Schwartz, M.W.; Vesk, P.A.; McCarthy, M.A.; Hahs, A.K.; Clemants, S.E.; Corlett, R.T.; Duncan, R.P.; Norton, B.A.; Thompson, K.; et al. A conceptual framework for predicting the effects of urban environments on floras. J. Ecol. 2009, 97, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S.; von Wehrden, H.; Poirazidis, K.; Wrbka, T.; Kati, V. Multiscale performance of landscape metrics as indicators of species richness of plants, insects and vertebrates. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 31, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ouyang, Z.; Meng, X.; Wang, X. Plant species composition in relation to green cover configuration and function of urban parks in Beijing, China. Ecol. Res. 2006, 21, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.W.; Li, L.; Jenerette, G.D.; Yu, Z. Drivers of plant biodiversity and ecosystem service production in home gardens across the Beijing Municipality of China. Urban Ecosyst. 2014, 17, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szlavecz, K.; Warren, P.; Pickett, S. Biodiversity on the Urban Landscape Human Population; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 75–101. [Google Scholar]

- Beninde, J.; Veith, M.; Hochkirch, A. Biodiversity in cities needs space: A meta-analysis of factors determining intra-urban biodiversity variation. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, J.P.; Cousins, S.A. Island biogeography theory outweighs habitat amount hypothesis in predicting plant species richness in small grassland remnants. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 1895–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, E.R. Species richness of urban forest patches and implications for urban landscape diversity. Landsc. Ecol. 1988, 1, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkinson, D.; Kopel, D.; Wittenberg, L. From rural-urban gradients to patch–matrix frameworks: Plant diversity patterns in urban landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 169, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honnay, O.; Endels, P.; Vereecken, H.; Hermy, M. The role of patch area and habitat diversity in explaining native plant species richness in disturbed suburban forest patches in northern Belgium. Divers. Distrib. 1999, 5, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angold, P.G.; Sadler, J.P.; Hill, M.O.; Pullin, A.; Rushton, S.; Austin, K.; Small, E.; Wood, B.; Wadsworth, R.; Sanderson, R.; et al. Biodiversity in urban habitat patches. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 360, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O.; MacArthur, R.H. The Theory of Island Biogeography; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Brice, M.H.; Pellerin, S.; Poulin, M. Environmental filtering and spatial processes in urban riparian forests. J. Veg. Sci. 2016, 27, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.D.; Liu, Y.H.; Meng, F.G. Study on Plant Composition and Species Diversity of Residential Greenbelt in Beijing City. Forest Inventory Plan. 2007, 32, 17–21, (In Chinese, with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.A.; Warren, P.S.; Kinzig, A.P. Neighborhood socioeconomic status is a useful predictor of perennial landscape vegetation in residential neighborhoods and embedded small parks of Phoenix, AZ. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.; Lefler, L.; Freedman, B. Plant communities of selected urbanized areas of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 71, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, M.; Pataki, D.E.; Gillespie, T.; Jenerette, G.D.; McCarthy, H.R.; Pincetl, S.; Weller-Clarke, L. Tree diversity in southern California’s urban forest: The interacting roles of social and environmental variables. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 3, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnussen, S.; Smith, B.; Uribe, A.S. National Forest Inventories in North America for monitoring forest tree species diversity. Plant Biosyst. 2007, 141, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).