Abstract

This article investigates the role of the model of family and their savings as a support to growth and source of economic sustainability. The central objective of the present article was to determine the impact of the model of a family on the propensity to save money in the population of Poland. As indicated by independence tests, in most studied cases, the model of a family does not have a key role in sustainable consumption and saving behavior. The only exception are the forms of allocation of the saved capital. The study results suggest that households in Poland hold traditional views on the family model and the allocation of their savings. Decisions in everyday life are often reached together with the partner, which may attest to the growing egalitarian tendencies in Polish families. The research shows that the funds saved monthly by households are not planned in advance but constitute a financial surplus after all the expenses have been paid, which is then set aside as a reserve for the future. Partners usually prefer to have separate bank accounts with funds for day-to-day spending. However, the awareness concerning the forms of allocating capital is still poor, which is confirmed by the fact that most of the financial surplus is kept in the current account. The funds saved this way are spent to satisfy current needs, such as holidays or durable goods, and cover expenses in emergencies, which may be particularly important in the context of minimizing the risk of poverty and social exclusion, which should be prevented in line with the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030.

1. Introduction

Fluctuations in the global economy observed in recent years and the need to increase efforts for sustainable development have necessitated a change in the approach to risk and uncertainty assessment for all business entities operating within the global market economy. The COVID-19 pandemic forced many entities, both on the supply and the demand sides, to change the way of thinking about the structure of production, its diversification, and the structure of consumption over time. COVID-19 has impacted household income, savings, consumption, and poverty [1]. Malter et al. [2] highlighted the importance of future research on the impact of the pandemic on buyer behavior and on sustainability values. Social conviction on economic stability has led to an increase in the size of consumption bubbles and, in consequence, a decrease in household savings and an increase in their debt. An avalanche of destabilizing events in recent years in eastern and central European countries—the COVID-19 pandemic [3,4], the war in Ukraine [5], and a high inflation rate [6] which has been a catalyst for a drop in the real income of households, undoubtedly resulted in increasing uncertainty about the nearest future, both in an economic and in a social and existential sense. Sustainable consumption is currently one of the main topics of debate, both in public and in academia [7]. In the literature, authors attempt to determine the impact of various factors influencing sustainable consumption, including behavioral intention, environmental knowledge, perception of consequence, environmental responsibility, environmental value, perceived behavioral control, response efficacy, environmental sensitivity, and also the contextual factors [8]. Bogusz et al. [9] emphasized that the functioning of individual households in terms of sustainable consumption is influenced by the age, education, location, and wealth of individual respondents. Others have considered sustainable consumer decisions in terms of factors such as product availability, price, location, habits, convenience, environmental pressure, and emotional attractiveness [10]. Regardless of the factors examined, sustainable consumption implies changing the consumption patterns of households through changes in lifestyles and individual consumer behavior and choices [11]. It requires prioritizing our present needs and changing current lifestyles for the benefit of future generations [12]. A traditional approach to the Polish lifestyle, based on the family and the need to provide for it, not only in the material but also in the physical sense, enabled the authors to claim that the family model can be one of the key determinants affecting the households’ consumption and propensity for saving. This article tries to fill the research gap in this area. This is especially the case in regions with family traditions, in the traditional sense of the word, having been observed for years—i.e., the future being based on procreation and raising children. The Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship is one such region, and its characteristic features include a low level of urban and industrial development, a low level of household income and a high unemployment rate. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to determine the impact of the family model on the propensity for saving in households in the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodship. This subject has been the focus of recent discussions at the Department of Economic Theory at the University of Warmia and Mazury through a series of unpublished research projects conducted with the involvement of students for their thesis work. These investigations, conducted by multiple independent research teams, unveiled an initial depiction indicating a prevailing low inclination towards saving. Furthermore, it was highlighted that the deficiency in savings primarily stems from the inclination to fulfill various needs that emerged within Polish households following the economic transformation period, largely driven by the increased frequency of international travels and the observation of the living standards in more affluent economies. The significant influence of assertive promotional strategies in the Polish media, advocating for a consumer-driven way of life, was also emphasized. Moreover, a pattern of imitative conduct was identified, characterized by the aspiration to match others in terms of material possessions. Taking into account the picture emerging from the above observations and the literature search, the authors formulated the following research hypotheses:

- -

- households in Poland, especially in regions with low household income, have a low propensity for saving, which is not only a consequence of a low income but also of a high level of needs one is aware of (a will to fulfill their needs, even at the expense of savings);

- -

- a family model has a significant impact on the level of household savings and the purpose they are earmarked for—households based on formal relationships and a traditional family model have a greater propensity for saving than the others;

- -

- the savings of Polish households are based on bank deposits, cash, and on buying real estate, material goods, and financial instruments, such as shares, for cash.

The phenomenon of financial stability of households is extremely important from the point of view of the stability of the financial of and the implementation of the concept of sustainable development [13]. Excessive debt of households may lead to their insolvency, which becomes particularly important in periods of economic instability, crises, and recession. From a microeconomic perspective, this may mean an increase in the risk of poverty and social exclusion, which should be prevented in line with the implementation of the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 [14]. Nowadays, the problem of excessive debt and its poor structure seems to be a global problem affecting, in particular, highly developed countries characterized by a high level of prosperity of their inhabitants and entrepreneurs [15]. The instability in the Polish economy raises concerns that the findings of the authors’ studies may differ from those conducted in more stable economies around the world and in Central and Eastern Europe. This highlights the importance and necessity of conducting studies within the specific scope outlined by the authors.

2. Literature Review

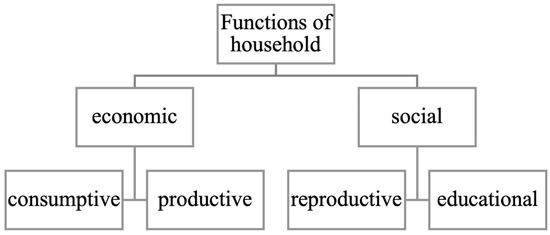

In economics, the household is defined as a cooperating micro-cell, which generates income and decides how it will be distributed. It produces goods, provides services, and collects supplies [16,17,18], [19] (pp. 1010–1011), [20] (p. 131), [21] (p. 34), [22] (p. 3), [23] (pp. 1225–1273), [24] (p. 91, 408), [25] (p. 315), [26] (pp. 45–61). The SNA (System of National Accounts) definition of a household is “a small group of persons who share the same living accommodation, who pool some, or all, of their income and wealth and who consume certain types of goods and services collectively, mainly housing and food.” [27]. According to Statistics Poland (former Central Statistical Office, in Poland, GUS), the household is defined as “a congregation of persons living and making a living together. Single, self-sustaining persons form single-person households. Households are distinct from the population of residents of apartments (without the facilities of collective housing). We divide households into single-person and multi-person (two or more persons), as well as family and non-family households.” [28]. In the present-day context, the household plays a significant role in the economic framework of a nation, with the efficacy and standard of household functions being critical elements in the overall prosperity of a country [29]. Most households are formed by families whose members are tied by biological and emotional bonds [30] (pp. 161–205). Regardless of the form of the household, their overriding goal is to satisfy mental and material needs. As such, these forms of behavior are intertwined with social and economic functions (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Functions pursued in households. Source: [31] (p. 82).

The main economic functions of households include consumption, which is defined as the use of goods by a household to satisfy the needs of its members, and production, which involves the generation of goods [24,32,33,34,35]. Currently, special attention is paid to sustainable consumption, which is becoming the main goal of local authorities, modern societies, and enterprises [36]. Sustainable consumption is a term used in the context of issues concerning human needs, quality of life, resource efficiency and waste minimalization, consumer health and safety, and consumer sovereignty [9]. In turn, the key social functions determine procreation and education with a view to preserving biological continuity. The cultural values and traditions held by household members develop ties between them, which leads to the formation of a community [37] (pp. 222–223), [38] (p. 5).

Households are usually formed by people tied by biological bonds who live together and identify as a family. This term is well-known and deeply embedded in social consciousness. The family is defined as both an institution and a social group based on marriage bonds, a relation of blood, affinity, or adoption [39,40,41,42,43,44]. The term “family model/model of family” encompasses the connections between family origins, indirect family settings, and direct family settings [45]. Family models can be divided into those that concern the emergent characteristics of the group and those that concern the characteristics and interactions of individual members [46]. Family models analyze the interactions within a family unit, most often as a husband and wife, that lead to purchasing decisions, influencing perceptions of priority, utility, and debt [47].

Depending on the number of family members, the form of marriage, sources of income, location of residence or the leading role of one family member, we can identify various types of family (Table 1). Today, it is also important to remember that, in addition to the traditional family consisting of a heterosexual married couple with biologically related children, an increasing number of households consist of adults without children or children raised by cohabiting parents, single parents, and stepparents. These families are often collectively referred to as “non-traditional families” and are formed mainly as a result of parental separation or divorce and the formation of a new marriage or cohabitation [48].

Table 1.

Classification of family types by criteria.

The nuclear family consists of a husband, wife, and children, who live together and maintain the household. An extended family (multi-generational) includes several nuclear families, where the power is vested in the oldest family member. On the other hand, in a modified extended family, also composed of several nuclear families, there is no hierarchy of authority, which is why they are economically independent of each other [50] (p. 300), [51] (pp. 23–24), [52] (p. 34), [53] (pp. 26–27), [54] (p. 127), [55] (p. 275). While a monogamous family is based on the marriage of one man to one woman, a polygamous family is composed of one person of one gender with at least two persons of the opposite gender [51] (p. 24), [52] (p. 34), [54] (pp. 118–119), [55] (p. 276), [56]. The source of income in farmer’s families is the farm, whereas the income of white-collar families involves clerical, administrative, or intellectual work [51] (p. 24), [52] (p. 35), [53] (p. 28). An urban family is formed by city dwellers and a rural family by people living in the countryside [52] (p. 36), [53] (p. 28), [57,58]. In a matriarchal family, the power is vested in a woman, and in a patriarchal family, in a man. An egalitarian family is characterized by equality and cooperation among its members [51] (p. 25), [54] (p. 130), [55] (p. 276), [59,60].

Households have a certain available budget, which they spend to satisfy the needs of their members. The unused part of this money is defined as savings [61]. In the relevant literature, this surplus is the non-consumed part of income [62,63]. In a broad sense, this may be defined as financial and non-financial assets not used to satisfy the needs; in a more narrow definition, this only refers to financial assets [64,65].

The propensity for saving in households is defined as the ability to suspend day-to-day consumption for the sake of future consumption. This ability may be studied through the rate of saving or the share of savings in the disposable income [66,67,68,69]. The propensity to build sustainable saving attitudes is directly related to influencing sustainable development by increasing the level of savings in society. According to Viswanath, P.V., an important determinant of the propensity to save is the degree to which an individual feels connected to the broader economy and the manifestation of his or her economic optimism. This interpretation is supported by the relationship between the propensity to save and variables such as consumption patterns and asset ownership, which may also reflect sustainable attitudes [70]. According to Keynes, the propensity for saving is the ability to delay consumption in time. This process is a function of the magnitude of income; the higher the income, the greater the ability to save [61]. Several factors determine the level of savings set aside by households, the most important of which should be identified as [71]:

- -

- external macroeconomic, such as the rate of inflation, the demographic situation, the rate of GDP growth, the GDP per capita, the level of real interest rates following from the monetary policy, the level of fiscal burdens following from the fiscal policy, the level of development of the financial system, and the market of financial products, etc.;

- -

- internal, such as the attained level of consumption, amount of disposable income, household structure (number of children, number of persons in education), etc.

Malter et al. (2020), already at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasized the importance of future research on the impact of the pandemic on buyer behavior and, at the same time, on values, which include sustainable development among the main future questions regarding consumer and household behavior [2]. The results of research conducted by Jia, H. et al. [72] showed that households’ allocation of financial assets has changed significantly before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has caused increased uncertainty about economic and social development where people’s psychological expectations about economic development play an important role in the allocation of household financial assets. Consumers’ tendency to change their behavior in times of economic uncertainty was also demonstrated by Nikodemska et al. [7] in research showing that during the pandemic, regardless of cultural differences, the behavior of middle-class consumers did not differ significantly, and the first reason for changing the shopping habits of buyers was the desire to save money. Also, the research of Zhang, Y. et al. [73] confirmed that households were generally saving more during the COVID-19 pandemic, adapting to more conservative asset allocation strategies, with increased demand for low-risk assets and reduced demand for high-risk, highly liquid assets. But, they also pointed out that households in the hardest-hit cities saved more during the COVID-19 pandemic, but tended to save less as the disaster began to fade.

According to research conducted by Waliszewski and Wachlewska [74] in Poland, as a result of the pandemic, there was a decline in spending compared to the period before the pandemic, which may explain the inability to spend money, decline in income, and freezing of expenses for fear of an uncertain future. Consumers tried to save more, but not everyone could afford it. Szustak et al. elucidated that the findings of investigations carried out by diverse establishments in Poland revealed that a majority of Polish individuals were experiencing favorable financial conditions and did not express dissatisfaction regarding the status of their household finances amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, notwithstanding the fact that the pandemic eroded a portion of their reserves. The rationale behind the decrease in savings could potentially stem from the Polish population’s aversion to incurring debts in periods of economic instability, leading to a preference for depleting savings excessively rather than resorting to credit or loans for funding substantial purchases [75]. Polish households have a low propensity for saving money, but the willingness to collect funds for future consumption is constantly increasing. Most often, the capital is held in savings accounts or as cash [76] (p. 106). The research corroborates the assumption of Keynes that the level and rate of savings increase along with the magnitude of income. Based on the study by Fatuła [77], it can be concluded that most households do not expect any limitations in the current consumption for the sake of building their savings and, at the same time, define their material situation as good. It should be noted that the studied households could not precisely state the aim of the capital building, which is mostly held in bank accounts.

According to research by Lerman [78] (p. 10), conducted in the USA, people who remain in a marriage enjoy a several times higher standard of living than those living in informal relations. The income of married couples is four times higher than their current needs. The income ratio of the people living in informal relations is between 20% and 70% of that of married couples. Additionally, due to the planned future and childbearing, married couples are more inclined to save funds than households based on informal relations [79]. This is also supported by the studies commissioned by the Polish central bank, which indicate that households formed by married couples have a greater propensity for saving funds (40%). Most often, they invest these funds in real estate, material goods, stocks, and shares. In addition, it should be noted that 35% of single people declare savings, of which as much as 40% have more savings than their annual income. It is estimated that 45% of childless households, 39% of married couples with two children, and 25% of married couples with three or more children have some savings. Most frequently, these savings equal the income generated within 1–3 months [76] (pp. 55–60).

3. Materials and Methods

The current study aimed to determine the impact of a family model on the inclination for saving funds in households. Based on the analysis of the literature on the subject, the following family models were taken into account as the independent variable in the study: monogamous family (two spouses), egalitarian family, endogamous family, patrilinear family, patriarchal family, matriarchal family, exogamous family, matrilineal family, and polygamous family. The study was conducted with the help of the CAWI (computer-assisted web interview) method via an online questionnaire at the turn of 2022 and 2023. The selection of this approach was based on its potential to guarantee the highest level of anonymity for participants in relation to delicate matters (pertaining to both their familial circumstances and financial status), a factor believed by the researchers to enhance the dependability of the responses.

To verify the purpose of the research, a survey questionnaire was prepared containing 19 substantive questions and a summary. The questionnaire used single- and multiple-choice questions and a 5-point Likert scale examining the frequency of selected consumer behaviors and the intensity of respondents’ beliefs. The survey questionnaire was comprised of questions categorized into various thematic domains. The initial section of the questionnaire endeavored to elucidate the Polish perspective on family, beyond the realm of scientific discourse. The divergence between the conservative societal views ingrained in Polish heritage [80,81,82,83] and the scientific standpoint leads to a notable disparity in the perception of family, especially concerning contemporary family structures. Consequently, the scientific exposition in the article and the resultant family paradigms may not always resonate with the surveyed participants (ex. Questions: What type of relationship between people would you consider a family? Which of the following situations best describes your family and relationship?). Subsequently, the questionnaire’s second segment sought to discern the family model to which the participants resonated, not solely from an academic standpoint, but also in light of their personal interpretations of family dynamics (ex. question: What family model does your household represent?). These inquiries specifically focused on identifying the familial decision-makers, encompassing financial aspects and ideological influences on consumption patterns (ex. questions: Who is the head of the family in your household? Who makes decisions in your household?). Subsequent sections expound on topics related to saving practices and preferences regarding investment strategies for these savings. Furthermore, an analysis of the underlying factors driving the observed consumption and saving patterns was also conducted (ex. questions: What type of bank account do you have? Who in your household decides on the purchase of products/services from the mentioned categories? How do you mainly save? What percentage of your monthly income do you save? For what reasons do you save? In what form do you have savings? etc.). The final part of the questionnaire was dedicated to establishing the socio-demographic profile of the respondents.

Statistical tests for many variables were used to elaborate the data. In most examinations, the Chi-square independence test was used; this test is frequently used for measuring dependent quality variables (1).

At number (r − 1)(w − 1) levels of liberty, where:

—observed numbers in i-th row and j-th column,

—expected numbers in i-th row and j-th column,

r—number of rows,

k—number of columns.

The use of the Chi-square test makes it possible to obtain information of the potential relationship between the variables. The strength of this relationship is measured with the V Cramér coefficient (2).

This indicator takes values from 0 (no relation between the variables) to 1 (total dependence between the studied variables), where k and p are the dimensions of the contingency table. The respondents filled in the questionnaire without assistance from the interviewer.

The sample selection was conducted based on the issue of small area statistics, which involve utilizing statistical data derived from the entire population to make inferences about the characteristics of smaller subpopulations known as small regions [84]. Within this framework, a subpopulation is regarded as a secondary small area, with a prevalence ranging from 1% to 10% of the primary subpopulation. The computation of the minimum sample size utilized the formula for determining the confidence interval for a binomial proportion [85]. The research utilized a confidence level of 0.95 and a maximum allowable estimation error of 6%. Given these parameters, the minimum sample size necessary was determined. Subsequently, after filtering out incomplete questionnaires, a sample size of 300 households was established for the research. Participants were duly informed that the investigation pertained to family behavior and that only one member per family could partake in the study. A total of 300 people participated in the study (175 women and 125 men). They were divided into six age groups. Most of the participants were aged 20–25 (46%), 25–35 (22%), and 35–45 (18%). In the context of people in these age groups, who will be the main purchasing power in the next twenty years, special attention was paid to linking their consumer behavior with the assumptions of the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 [69]. More than half had higher education—183 people, and 96 people had secondary education. Most respondents lived in the countryside (30%) and in smaller towns of up to 50,000 residents (25%). Most worked full-time (60%); the second most numerous group were students (23%). In total, 39% of the participants lived in two-person households, the lowest number of people (6%) were single. In total, 165 participants did not have children, 66 had one child, and 48 had two. The largest group of the participants declared a net monthly income of PLN 2000–3000 (28%) and monthly expenses of PLN 1000–2000 (49%).

4. Results

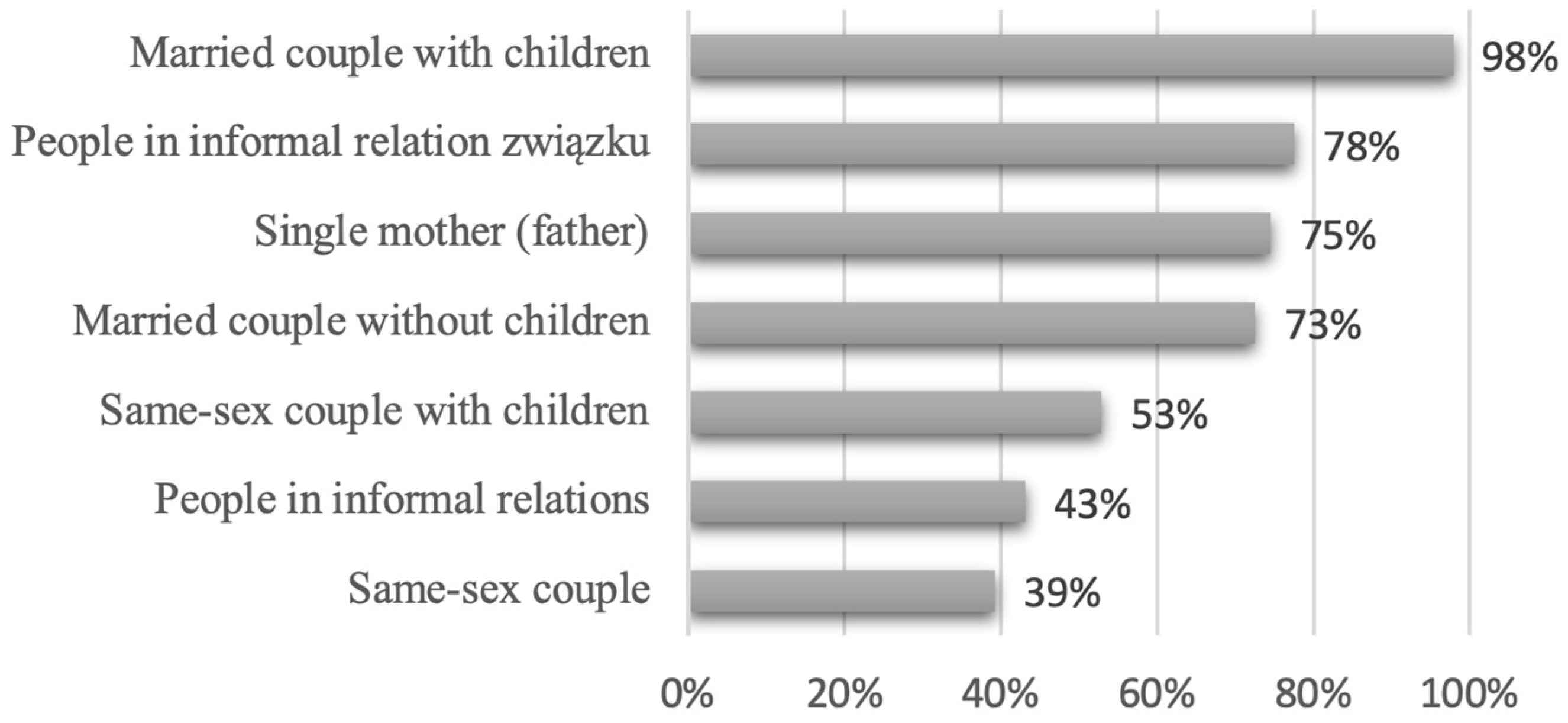

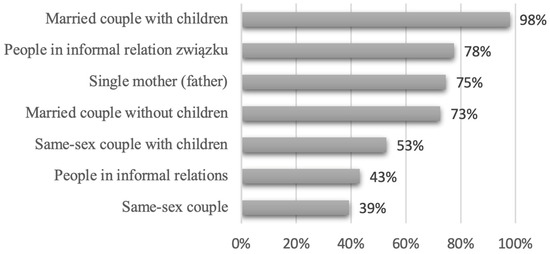

The study indicated that most Poles hold a traditional vision on family forming, which confirms the observations of a number of studies defining Polish society as a society with conservative views [80,81,82,83]. Most respondents defined the family as a married couple with children (98%) or mother/father as a single parent (75%); alternatively, this could be cohabiting parents in an informal relationship, bringing up children from this relationship (78%), or a married couple with no children (approximately 73%). The lowest number of the respondents regarded the family as a bond between people of the same sex (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Type of relationship considered as family by the respondents. Source: developed by the authors.

Households mostly rely on the cooperation of both partners/spouses. Most respondents declared that as a husband/wife/partner, they spend as much time working as each other and take an equal share of time to look after the home and children (62%). Much less numerous (25%) were the households where both man and woman worked, but the man focused mainly on professional duties, and the woman looked after the home and children on top of her job. Only 33 participants declared that only the man earned a living in their households, and the woman was a full-time housewife. There is a clear tendency to break with the tradition of large, multi-generational families (27% of the participants) towards households based on the model of a family composed solely of parents and children (30%) or childless families of one generation (21% of the participants).

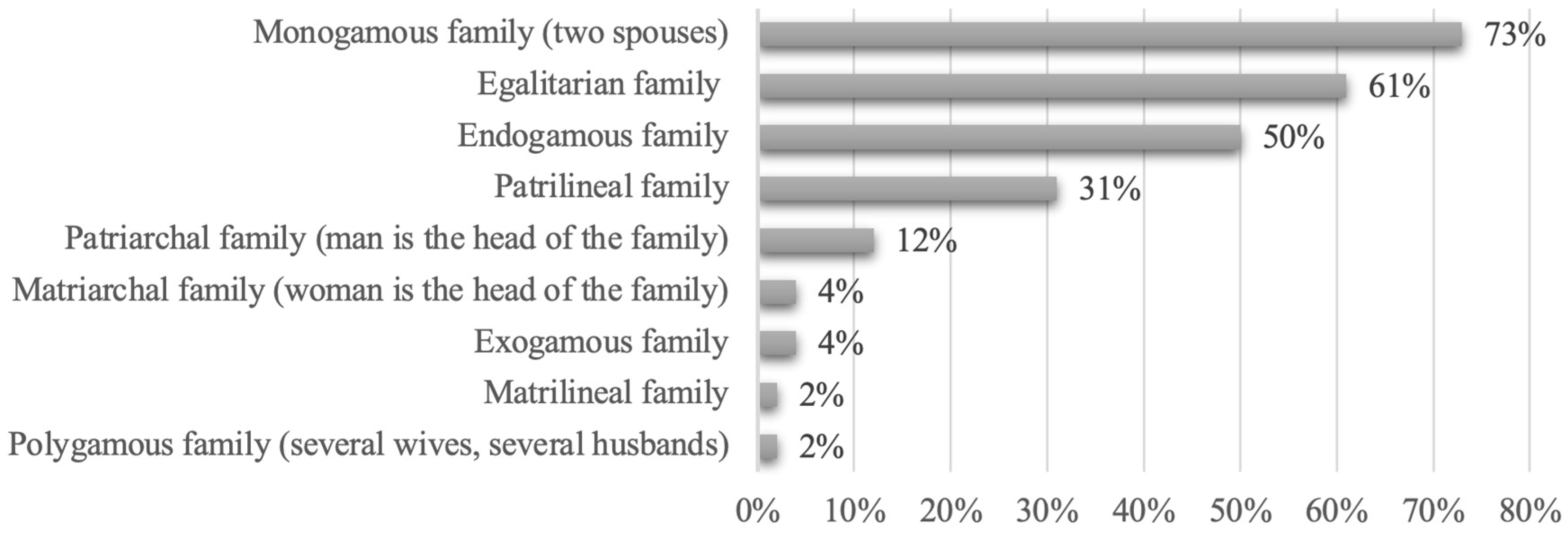

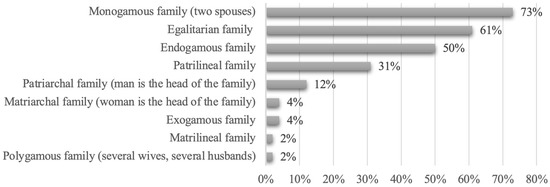

The participants in the study most often declared their model of the family to be two spouses of the same nationality running the household together, where the woman and children assume the family name and the property of the father (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Family model declared by the participants. Source: developed by the authors.

Such conservative views may result from deeply embedded traditions passed between Poles from generation to generation. New types of families [48] such as: self-declared polygamous or matrilineal families (where children assume the family name and the mother’s property) are the least frequent in the country.

Most respondents declared having separate, individual bank accounts (64%). They explained that most of their income comes into these individual accounts, from where most of their expenses are covered (in this case, most of the expenses in the product category are paid from individual accounts). The only aim on which money was spent from joint accounts was free time activities. The respondents most often reach decisions together with the partner on home maintenance and its equipment (72%), health services (55%), manner of spending free time (83%), and grocery purchases (68%). However, in the case of clothing and footwear, decisions were taken together or only by the woman (71%). It was only expenses on car maintenance that the participants declared that decisions are made mostly by the man (84%).

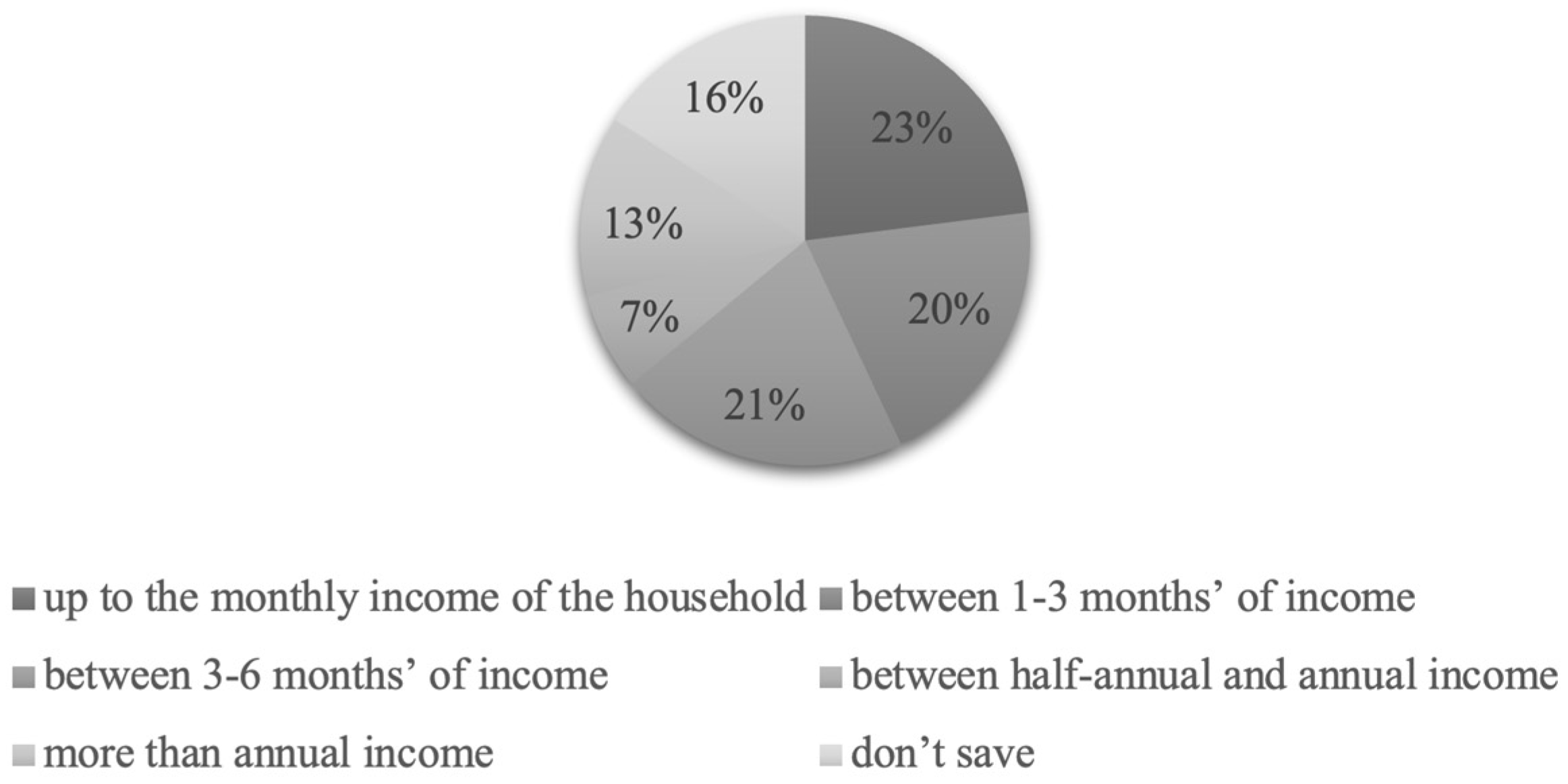

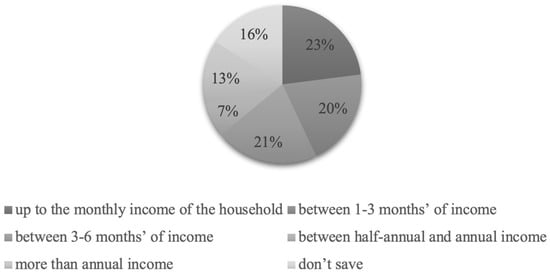

The respondents evaluated their financial situation as good (47%) or sufficient (31%). The smallest group described their situation as poor (3%). More than half declared that saving money is necessary. Although people are generally reluctant to save money, there is growing awareness of this necessity. This tendency was also visible in studies conducted, among others, in Polish society [74], demonstrating a surge in the inclination towards saving amidst the COVID-19 crisis due to escalated risks in the consumer landscape. There was a great variety in the amount of the declared savings. It may be noted that the largest percentage of the respondents said their financial reserve was at the level of their monthly income (23%)—Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Amount of savings in the surveyed households. Source: developed by the authors.

A slightly smaller number of respondents (20%) declared savings between one and three months’ worth of income, and between three and six months’ income (21%). In addition, it should be noted that as many as 16% did not save at all. The amount of money set aside after each month is the surplus of funds after all the expenses are covered (34%). A total of 25% of the respondents saved a planned amount of money, between 10% and 25% of their income. This finding validates the continued limited propensity of Poles to engage in saving, as evidenced in previous studies predating the pandemic (wherein, in 2016, 65% of Polish citizens possessed the capacity to save nominal sums, while 35% managed to amass financial reserves amounting to no more than PLN 250 per month) [71]. The amount and frequency of the saved income cannot be defined precisely, as the household did not exercise systematic discipline in this behavior. The conducted research did not indicate statistically significant dependence in the determinants of the total amount of savings (Table 2).

Table 2.

Analysis of dependence between the amount of savings and the variables in the matrix of the questionnaire.

It was found, however, that one factor determining the amount of monthly savings (the only one statistically significant) was the net monthly income (Table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of dependence between the amount of monthly savings and the variables in the matrix of the questionnaire.

The respondents largely declared their monthly income to be between PLN 2000 and 3000. It should be stressed that most of the respondents, regardless of their income (in the PLN 1000–5000 bracket), saved money irregularly, which may be due to unforeseen current expenses. In addition, some people whose monthly income was in the PLN 2000–3000 bracket admitted to regular savings of 10–25% of their monthly income.

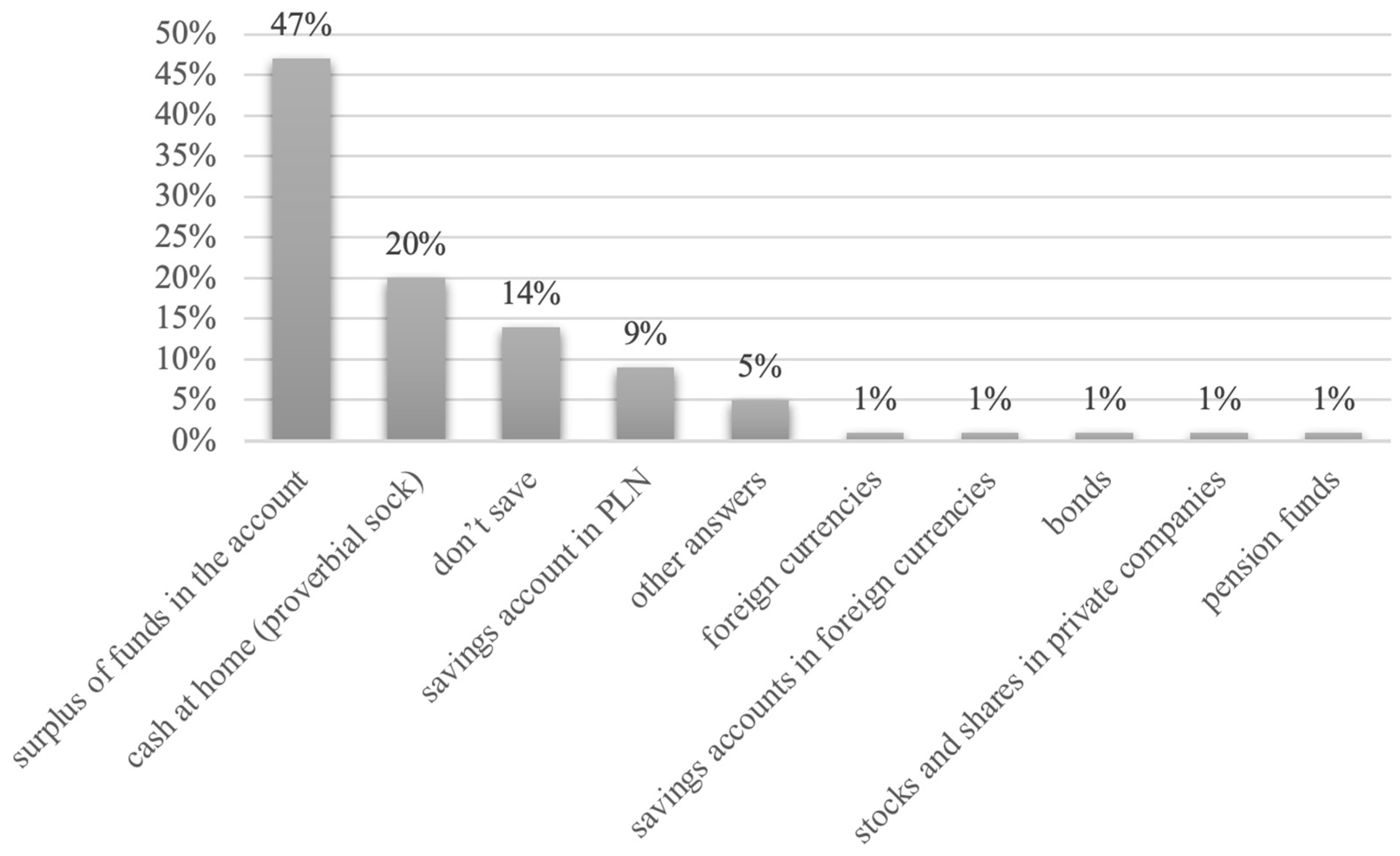

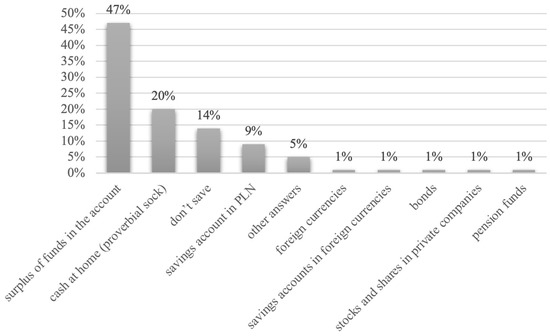

Less than half of the respondents (47%) kept their savings as a surplus in a bank account (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Preferred form of saving allocation in the surveyed households. Source: developed by the authors.

Saving money in the traditional way, as cash kept under a mattress, was preferred by as many as 20% of the respondents, while 9% used savings accounts for this purpose. This research demonstrates a lack of variation in this aspect dating back to 2016, a time when the primary method of saving was depositing funds into a bank account, with cash ranking as the secondary option within the savings framework [71]. It should be noted here that Polish society is not fully aware of the options for capital savers or is afraid of the risk of money allocation. Consequently, they limit themselves to the best-known and safest forms of fund saving. Most often, the manner, form, and aim of saving is negotiated with the partner.

Among the studied determinants, those which had a statistically significant impact on the selected forms of saving were the net monthly expenses of the household, the education, and the model of the family (Table 4).

Table 4.

Dependence analysis between the form of saving and the variables in the matrix of the questionnaire.

A surplus in the current account is the most common form of saving money. This way was preferred by the respondents with higher and secondary education. Moreover, it must be noted that this form of saving allocation is most frequently chosen by the people whose net monthly expenses reach the level of PLN 3000. This form of saving allocation was most often used by most households, regardless of their family model. Moreover, such behavior can be explained by a reluctance to take on risk or the lack of adequate financial knowledge.

Single-person households display a rather low propensity for saving money. The people with primary or basic vocational education prefer to keep cash at home. The respondents whose monthly expenses exceeded PLN 3000 did not precisely define their preferred form of capital allocation.

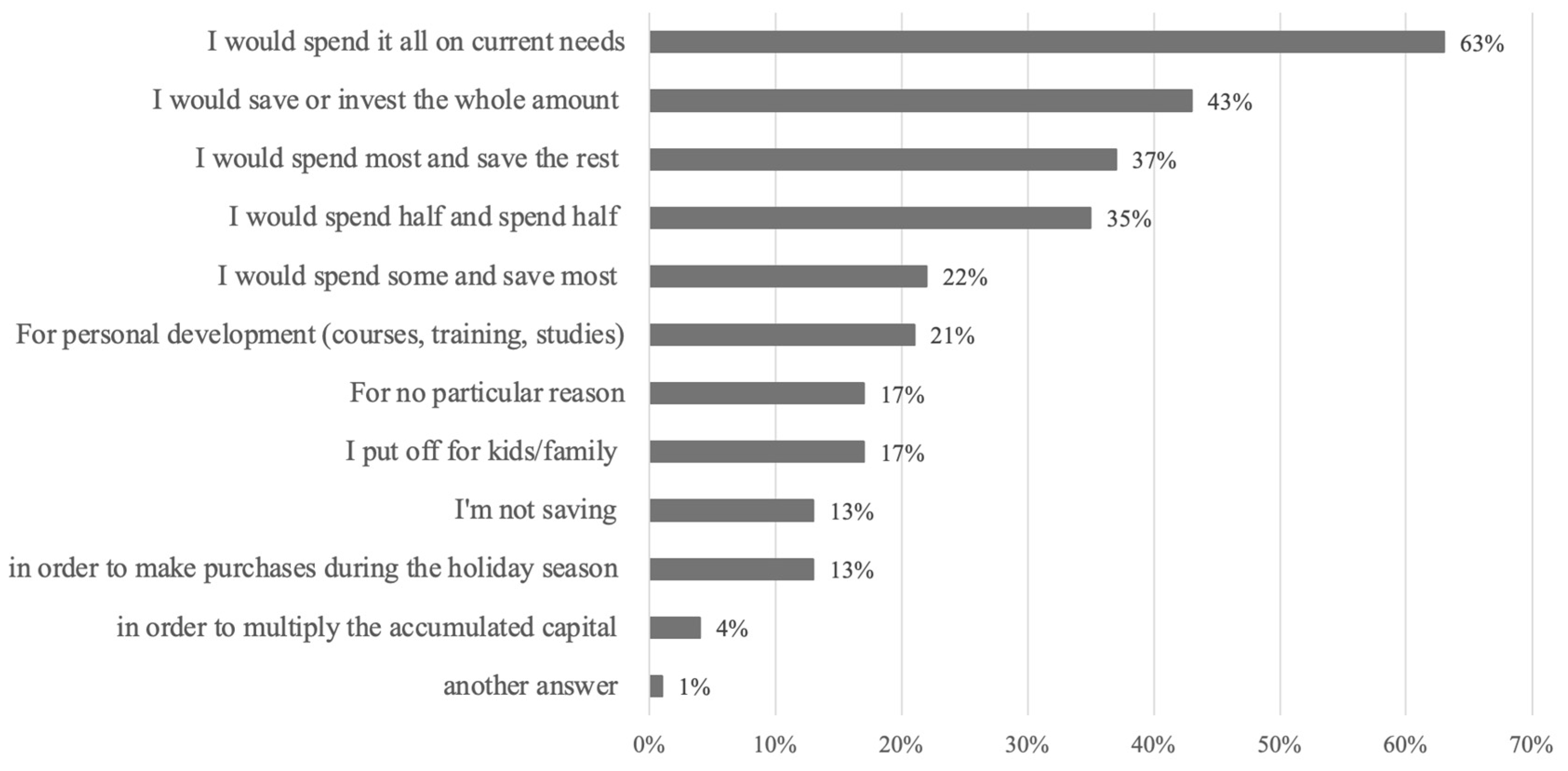

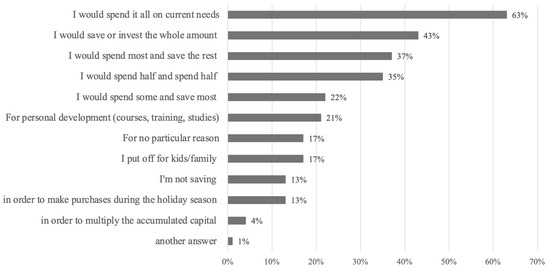

The main reasons for saving money identified by the respondents were risk reduction (63%), planned purchase of durable goods (43%), holidays (37%), and better living standards (35%)—Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Purposes of saving in the surveyed households. Source: developed by the authors.

The main motive for saving money is connected with the sense of uncertainty due to the risk of emergencies in the future. This rationale aligns with the findings of previous studies carried out in 2015 and 2016, prior to the onset of the pandemic [71,77]. The saved funds are set aside for the needs to be satisfied in the near future. In most cases, the reason for saving is clearly defined in advance. This means that most households focus on current needs and expenses and the satisfaction of these needs.

Regardless of the family model, the respondents mostly save money to minimize the future risk. Both small and large families also declared that they collected funds to finance holiday expenses. Concerning small families and people in stable relationships, a large portion of savings are set aside with the purchase of durable goods in mind. On the other hand, in multi-child families and among people in steady relationships, the priority was to maintain a reserve capital to improve living conditions.

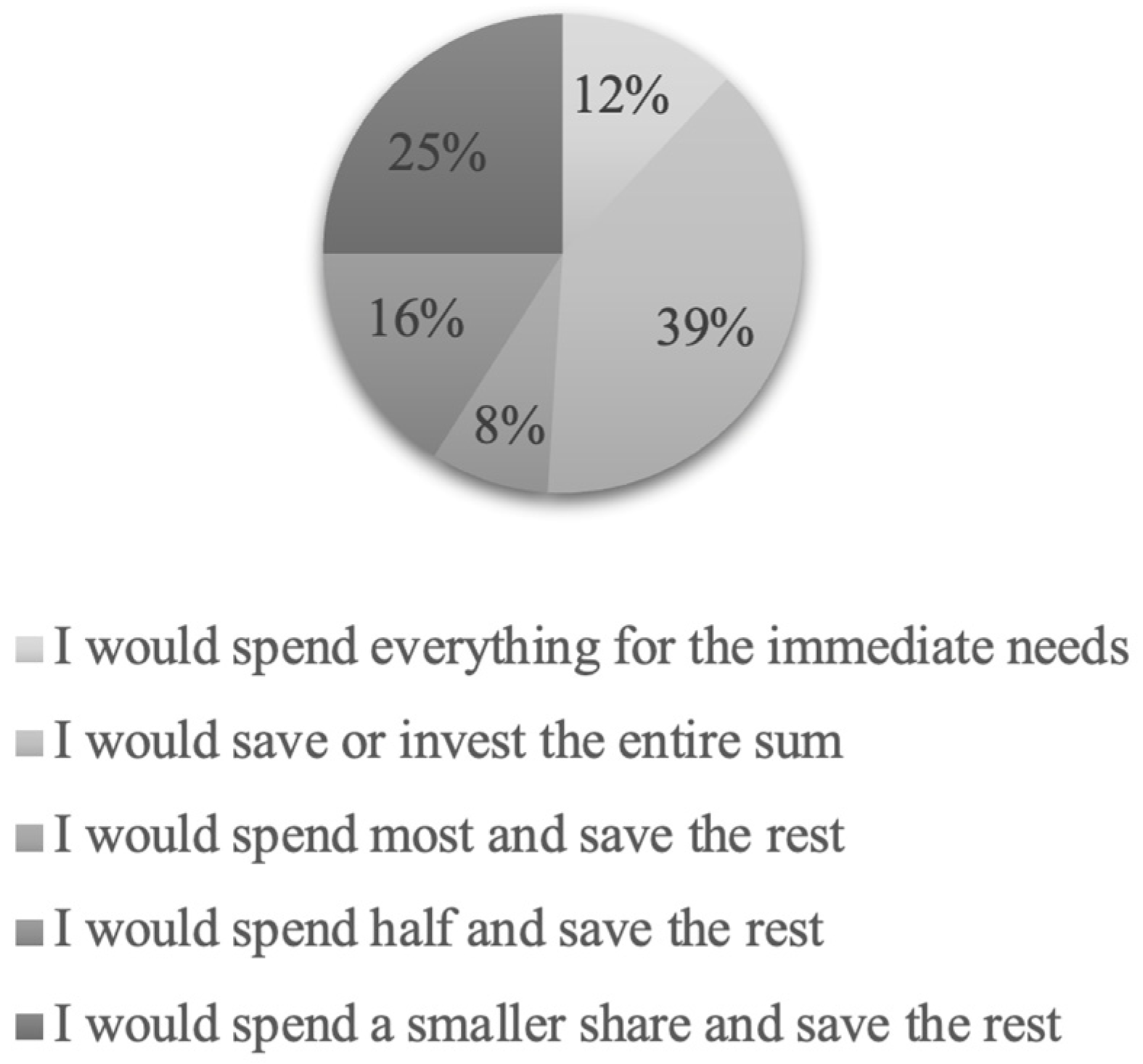

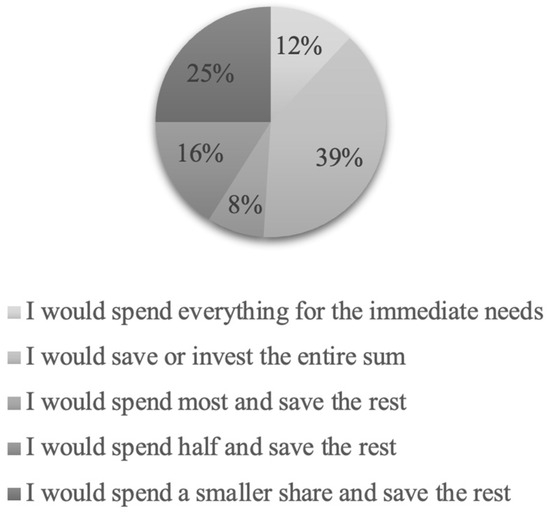

The respondents in their large majority declared that upon receiving PLN 1000, they would set aside, invest the whole amount (39%), or spend a smaller part and save the rest (25%)—Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Predicted behavior of households upon receiving PLN 1000. Source: own elaboration.

The smallest percentage of the respondents would spend most of this extra money and save the rest (8%). Such declarations may speak to the growing awareness of Poles concerning money saving.

More than half the respondents could not decide if they would prefer to stop satisfying their current whims for the sake of future consumption (saving). However, 30% claimed that the current consumption is more important than having reserve funds for the future satisfaction of needs. Only 18% were able to give up buying goods and services for the sake of financial security for the coming years. Over 40% could not unequivocally say if saving money means denying the pleasures of life. Not many less (37%) claimed that saving funds did not mean giving up such pleasures.

5. Discussion

As a result of this study, all three research hypotheses could be verified. Although the study participants usually described their situation as good (and not as “bad”, anyway), they also described their level of savings as low. It must be noted that the way the respondents judged the level of their savings as high/low was totally subjective. They judged it by viewing how many times larger their sum of total savings is than their monthly income. Since the level of income among the respondents is among the lowest in Poland, as it is a specific feature of the Voivodship of Warmia and Mazury, this is confirmed by the low level of their savings, which has corroborated the first hypothesis and the previous study findings of other authors [76] (p. 106), [77]. The reason for this state of affairs may be the still low willingness of Polish society to postpone the benefits of current consumption in favor of increasing consumption in the future, which was indicated by Fatuła in his research [77].

The second hypothesis was only partly verified. No impact of the family model was observed on the level of savings or on the main reason for saving, which was indicated by the previous study conducted by, for example, Lerman [78], Hao [86], and the Polish National Bank’s publication [76]. The level of savings was similar in each case, and putting aside some money was caused by caution which was caused by uncertainty about the near future. Consumers’ tendency to engage in such behavior in times of economic uncertainty was also shown by Nikodemska’s et al. [7] research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic in four countries, where the first reason for changing shopping habits to more sustainable ones was the desire to save money. At the same time, among the respondents of our study, the amount of accumulated cash decreased compared to the study conducted earlier by Anioła and Gołaś [76]. The study findings differ mainly from other economic conditions during the studies (these studies were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukrainian crisis). The observed differences concerned only secondary reasons for the accumulation of savings. Formal couples, especially those with numerous offspring, delay their consumption because they want to raise their living standard in future, whereas others delay because they want to purchase various movable items of property (e.g., a new car). Referring to Biswas and Roy [12], the ability to delay consumption is part of the possibility of changing consumer behavior towards a more sustainable model of household financial management. It is noteworthy that, unlike in Fatuła’s 2015 study [77], the respondents were usually able to specify the purpose for which they wanted to spend their savings. This is probably a consequence of a different temporal and spatial scope of the study. The purpose for which the savings will be spent may be less specified in regions with higher income levels because household needs are satisfied to a greater extent. On the other hand, the level of unsatisfied needs one is aware of is relatively high in poorer regions. Consequently, households can precisely specify what they need and want to spend their accumulated cash on in the future.

The third hypothesis was also verified only in part. Savings are kept mainly at home and in bank deposits, but the trend of depositing savings in other instruments, such as real estate and financial instruments, like shares, has stopped. It is noteworthy that—on the one hand—the Ukrainian crisis has increased the importance of individual investors earning money by draining the market of apartments for rent, and on the other—it increased the importance of cash fluidity because of the geopolitical instability. This especially applies to the eastern regions of Poland, where the war in Ukraine and its effects have made themselves felt to the greatest extent. Should the conflict escalate, the value of assets of low fluidity and those with high risk can drop rapidly, which already impacts the market on the side of saving households. Additionally, the high inflation rate in Poland, felt to the greatest extent in less wealthy regions (and the Warmińsko-Mazurskie Voivodeship is among them), breeds a tendency to change the purpose for which the saved money is spent—a revision of earlier plans regarding the purchase of material goods, going on an expensive holiday, at the expense of basic household needs, and/or an increase in the amount of financial reserves. Long-term revision of savings in order to meet the basic needs of consumers may result in a significant reduction in the quality of life, which is influenced by environmental, social, and economic conditions inherent in the concept of sustainable development. Achieving stability at the microfinance level by households most often results in an increase in their quality of life [87,88]. Assuming that the financial sector plays a key role in stimulating socio-economic development consistent with the concept of sustainable development, the use of sustainable financing instruments may contribute to the elimination of the negative effects of social and environmental risk [13].

6. Conclusions

Regardless of the changes taking place in households, the traditional model of a family (a married couple with children) is still prevalent in Polish society. Relations between family members have changed over the years, with an increasing role of the woman in the household leading to the progressing egalitarianism of Polish families. Most study participants ran the household in cooperation with the partner and equally shared domestic and professional duties. Most respondents had individual bank accounts, to which most of their income was transferred and from which they made most of the monthly expenses. This is undoubtedly indicative of the need to be financially independent. The household management decisions were usually taken together with the partner. The majority of the respondents declared having savings equal to the amount of their monthly income. Such a low value of savings may expose this group to loss of financial liquidity and even the risk of poverty in the event of sudden changes in the economy. From the perspective of the Sustainable Development Goals, this is a group that undoubtedly requires support both at the level of financial education and the ability to achieve higher income. The amount of savings set aside every month is rarely planned in advance, except for the group whose monthly income was in the range of PLN 2000–3000. They declared regular savings of 10–25% of their monthly income. The preferred form of saving allocation was keeping the surplus in the current account or as cash at home which makes these funds vulnerable to significant loss of value during rising inflation. Most of those with higher or secondary education preferred holding their capital as surplus in a bank account. It should be added here that this was also the form of choice among the individuals whose monthly expenses reached the net sum of PLN 2000, but usually only by married couples with children and people living in a stable relationship with their partner.

On the other hand, the respondents with primary and vocational education most frequently kept their savings as cash at home, which may be explained by their reluctance to take on risk or the lack of adequate knowledge of the financial market. The main reasons for saving money followed from the need to have capital at disposal in case of emergency or to buy durable goods in the future. It should be noted here that saving for children’s future was not the main objective of the studied households. They would rather focus on current problems and expenses and satisfying the present needs. Despite the growing recognition of the need for maintaining a financial reserve, members of households found it difficult to refrain from satisfying current needs for a more secure future.

These phenomena observed by the authors should be taken into consideration by investors—both professional and non-professional ones (households)—in planning their actions in a financial market concerning depositing their savings, as failing to take them into account and benefiting from a speculative bubble can lead to serious financial trouble, not only on a micro- but also on a macro-scale. It is noteworthy that some investors use foreign financing secure by the real property being purchased, which—in the case of adverse geopolitical changes—can result not only in a loss of fluidity but also upset the fluidity of the banking sector caused by failure to repay liabilities and a drop in the value of real property used as security for bank loans. From the perspective of building a society based on the principles of sustainable development, financial education seems to be a priority that allows raising social awareness about sustainable finances and financial resilience, which has a direct impact on the quality of life and indirectly on the related environmental, social, and economic conditions that fit the concept of sustainable development.

7. Limitations of the Research

The presented research results are a preliminary analysis carried out by the authors aimed at verifying the hypotheses. The next step would be a multivariate regression analysis and determining the importance of other factors influencing the propensity to save, which the authors hope to implement in subsequent studies. Due to the limited size of the research sample and the dynamics of changes in the economic environment, the authors see the need for monitoring these issues further because we are currently unable to predict the further development of the political and economic situation, either in central or eastern Europe or in Poland. At the same time, it would be interesting to expand the research to include other regions of Poland and other EU countries in order to capture differences in sustainable finance between societies with different worldviews. Another constraint of this study is the subjective quality of the responses provided by the participants. This aspect holds significance within the context of the polish society as polish households, despite not explicitly acknowledging it, deviate from the global principle of equality. As a result, most financial decisions could be dictated by the household head rather than being a product of familial agreements. Consequently, the spending and saving habits of individual family members might diverge from the officially stated norms upheld by the entire family unit. In this regard, it may be beneficial to enhance this study by incorporating qualitative approaches like conducting in-depth interviews with multiple individuals residing in a single household simultaneously. This could facilitate acquiring a more comprehensive understanding of the family structure and their financial decision-making processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M. and J.M.; methodology, P.M. and J.M.; software, P.M. and J.M.; validation, P.M., J.M. and K.A.; formal analysis P.M., J.M. and K.A.; investigation P.M. and J.M.; resources, P.M. and J.M.; data curation, P.M. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation, P.M., J.M. and K.A.; writing—review and editing, P.M., J.M. and K.A.; visualization, P.M., J.M. and K.A.; supervision, K.A.; project administration, P.M. and J.M.; funding acquisition, P.M., J.M. and K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the students Katarzyna Pawelska and Wiktoria Janicka for their help in carrying out the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martin, A.; Markhvida, M.; Hallegatte, S.; Walsh, B. Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on Household Consumption and Poverty. Econ. Disasters Clim. Chang. 2010, 4, 453–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malter, M.S.; Holbrook, M.B.; Kahn, B.E.; Parker, J.R.; Lehmann, D.R. The past, present, and future of consumer research. Mark. Lett. 2020, 31, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramarova, K.; Švábová, L.; Gabrikova, B. Impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on unemployment in Slovakia: A statistically created counterfactual approach using the time series analysis. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2022, 17, 343–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privara, A. Economic growth and labour market in the European Union: Lessons from COVID-19. Oeconomia Copernic. 2022, 13, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiszeder, P.; Małecka, M. Forecasting volatility during the outbreak of Russian invasion of Ukraine: Application to commodities, stock indices, currencies, and cryptocurrencies. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2022, 17, 939–967. [Google Scholar]

- Price Indices of Consumer Goods and Services in December 2023. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ceny-handel/wskazniki-cen/wskazniki-cen-towarow-i-uslug-konsumpcyjnych-w-grudniu-2023-roku,2,146.html (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Nikodemska-Wołowik, A.; Wach, D.; Andruszkiewicz, K.; Otukoya, A. Conscious shopping of middle-class consumers during the pandemic: Exploratory study in Mexico, Nigeria, Poland, and Sri Lanka. Int. J. Manag. Econ. 2021, 57, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Q.; Qi, Y. Factors Influencing Sustainable Consumption Behaviors: A Survey of the Rural Residents in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, M.; Matysik-Pejas, R.; Krasnodębski, A.; Dziekański, P. Sustainable Consumption of Households According to the Zero Waste Concept. Energies 2023, 16, 6516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajn, N. European Parliament Think Tank. Sustainable Consumption: Helping Consumers Make Eco-Friendly Choices. 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2020)659295 (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Ari, I.; Yikmaz, R.F. Chapter 4—Greening of industry in a resource- and environment-constrained world. In Handbook of Green Economics; Sevil, A., Erinç, Y., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Roy, M. Green products: An exploratory study on the consumer behaviour in emerging economies of the East. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoz, A.; Zioło, M. Zrównoważone finanse a stabilność finansowa gospodarstw domowych. In Finanse Osobiste; Waliszewski, K., Ed.; Polska Akademia Nauk: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; Volume 2, pp. 261–273. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. A/RES/70/1 Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Franc-Dąbrowska, J.; Porada-Rochoń, M.; Świecka, B. Insolvency of enterprieses and households—Comparative analysis. Zeszyty Naukowe SGGW, Polityki Europejskie. Finans. I Mark. 2018, 19, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, H. Economic Problems of the Family; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, H. Economic Responsibilities of Families: Increasing or Diminishing? J. Home Econ. 1952, 44, 616–661. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, H. The Family in the American Economy; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Burgiel, A. Collaborative Consumption as an Alternative Option for the Consumer of the 21st Century. Mark. I Rynek 2014, 8, 1010–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Stępnicka, N.; Wiączek, P. Time Banks vs. Household Production Theory and Threats to The Fiscal Security of The State. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2019, 63, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałaszewska-Reindl, T.; Michna, W. Gospodarstwo domowe—Ekonomiczna i organizacyjna baza rodziny polskiej. In Polskie Gospodarstwa Domowe: Życie Codzienne; Pałaszewska-Reindl, T., Ed.; Studia i Materiały; Wydział Zarządzania UW: Warszawa, Poland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Ironmonger, D. Household Production and the Household Economy. Univ. Melb. Dep. Econ. 2001; Research Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, J.; Seshadri, A. Technological Progress and Economic Transformation. In Handbook of Economic Growth; Aghion, P., Durlauf, S.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 1, pp. 1225–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, M.G. Economics of Household Production; J. Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Forget, E.; Reid, M.G. The Elgar Companion to the Chicago School of Economics; Emmett, R.B., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham/Northampton, UK, 2010; pp. 315–317. [Google Scholar]

- Brettell, C.B. Gendered lives: Transitions and turning points in personal, family, and historical time. Curr. Anthropol. 2002, 43 (Suppl. S4), S45–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Stat. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1255 (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Concepts Used in Public Statistics. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/metainformacje/slownik-pojec/pojecia-stosowane-w-statystyce-publicznej/103,pojecie.html (accessed on 20 November 2023).

- Kodolova, I.; Yusupova, L.; Nikonova, T.; Khisamova, E.; Veslogusova, M. Modern methods of managing household finances in Russia. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisako, S.J. Family and household: The analysis of domestic groups. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1979, 8, 161–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalega, T. Konsumpcja Determinanty, Teorie i Modele; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt-Clermont, L. Household Production and Income: Some Preliminary Issues; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ironmonger, D. Household Production; Smelser, N.J., Baltes, P.B., Eds.; International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences: Berlin, Germany, 2001; pp. 6934–6939. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, W.E. Household Production and the Demand for Food and Other Inputs: U.S. Evidence. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2011, 36, 465–487. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23243519 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Urban, S. Farm households in comparison with the other type of households. Probl. Small Agric. Hold. 2016, 4, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, L. The impact of emotions on the intention of sustainable consumption choices: Evidence from a big city in an emerging country. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, J. Społeczne problemy rodziny. In Polityka Społeczna; Rajkiewicz, A., Ed.; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Mbunda, F.D. Cultural values, transition and modernity. In Problems of Culture and Cultural Values in the Contemporary World; Unesco CLT/MD/2; Unesco Digital Library: Paris, France, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Tyszka, Z. The sociology of family in Poland. Ruch Praw. Ekon. I Socjol. 1990, 52, 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A. Help one another, use one another: Toward an anthropology of family business. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2003, 27, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A. Sources of entrepreneurial discretion in kinship systems. In Entrepreneurship and Family Business; Stewart, A., Lumpkin, G.T., Katz, J.A., Eds.; Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth; Emerald Group: Bingley, UK, 2010; Volume 12, pp. 291–313. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, A. The anthropology of family business: An imagined ideal. In SAGE Handbook of Family Business; Melin, L., Nordqvist, M., Sharma, P., Eds.; Newbury Park: Sage, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 66–82. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, S. Human Families; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, M. Concept and conceptual frameworks for understanding family. In Enhancing the Role of the Family as an Agency for Social and Economic Development; Unit for Family Studies Report; TISS: Bombay, India, 1994; pp. 16–41. [Google Scholar]

- Marjoribanks, K. Family Environments and Children’s Outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Commentary: A Family is a Family is a Family. Fam. Process 1984, 23, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollay, R. A model of family decision making. Eur. J. Mark. 1968, 2, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golombok, S. Parenting in new family forms. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 15, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Śmigielski, W. Modele życia rodzinnego. In Studium Demograficzno-Społeczne na Przykładzie Łódzkiej Młodzieży Akademickiej; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Szczepański, J. Elementarne Pojęcia Socjologii; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, A. Rodzina i jej przemiany; Instytut Stosowanych Nauk Społecznych: Warszawa, Poland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Adamski, F.R. Wymiar Społeczno-Kulturowy; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gębuś, D. Rodzina Tak, Ale Jaka? Wydawnictwo Akademickie „Żak”: Warszawa, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Szlendak, T. Socjologia Rodziny. Ewolucja, Historia, Zróżnicowanie; WN PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sztompka, P. Socjologia. Analiza Społeczeństwa; Wydawnictwo Znak: Kraków, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ault, M.K.; Gilder, B.V. Polygamous Family Structure: How Communication Affects the Division of Household Labor. West. J. Commun. 2016, 80, 559–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, K. CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Who Is Included in the Urban Family? Counterpoints 2010, 215, 261–272. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42980450 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Isaacs, J.L. The Urban Family: Urban Marriage and Divorce. Fam. Law Q. 1967, 1, 39–44. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25738769 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Kumagai, F. Family Egalitarianism in Cultural Contexts: High-Variation Japanese Egalitarianism vs. Low-Variation American Egalitarianism. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 1979, 10, 315–329. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41601089 (accessed on 15 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tereškinas, A. Between the egalitarian and neotraditional family: Gender attitudes and values in contemporary Lithuania. Kultūra Ir Visuomenė Soc. Tyrim. Žurnalas 2010, 1, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, J.M. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, G.; Sabelhaus, J. Perspectives on the Household Saving Rate. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 1999, 1999, 181–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hussein, K.; Mohieldin, M.; Rostom, A. Savings. Financial Development and Economic Growth in Egypt. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 2017, No. 8020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2948487 (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- OECD Household Savings (Ed.) OECD Factbook 2015–2016: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Musiał, M. Savings behavior in Poland as opposed to selected European Union countries. Mark. I Rynek 2014, 8, 1147–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, B.; Burtless, G.; Sabelhaus, J. The Decline in Saving: Evidence from Household Surveys. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 1991, 22, 183–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, G.; Piguillem, F. Saving Rates and Savings Ratios. In EIEF Working Papers Series 2116; Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance (EIEF): Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kłopocka, A. Household Propensity to Save and Financial Knowledge. Bank I Kredyt 2018, 49, 461–492. [Google Scholar]

- Kryuchkova, I. The rate of gross saving: Theory and practice. Econ. Forecast. 2019, 3, 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath, P. Connectivity and Savings Propensity among Odisha Tribals. Sustainability 2021, 13, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierzbicka, E. Determinants of Increasing Household Savings in Poland. ZN WSH Zarządzanie 2018, 19, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Fan, S.; Xia, M. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on household financial asset allocation: A China population study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 990610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhong, Q. Pandemic, Precautionary Saving, and Household Portfolio Choice: Evidence from China. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2022, 58, 4338–4349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waliszewski, K.; Warchlewska, A. Comparative analysis of Poland and selected countries in terms of household financial behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic. Equilibrium 2021, 16, 577–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szustak, G.; Gradoń, W.; Szewczyk, Ł. Household Financial Situation during the COVID-19 Pandemic with Particular Emphasis on Savings—An Evidence from Poland Compared to Other CEE States. Risks 2021, 9, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anioła, P.; Gołaś, Z. Zastosowanie Wielowymiarowych Metod Statystycznych w Typologii Strategii Oszczędnościowych Gospodarstw Domowych w Polsce; NBP: Warszawa, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fatuła, D. Resource Allocation for Consumption, Savings and Investments among Polish Households. Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. W Krakowie 2015, 12, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, R.I. Marriage and the Economic Well-Being of Families with Children. A Review of the Literature, Urban Institute and American University. Available online: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/60516/410541-Marriage-and-the-Economic-Well-Being-of-Families-with-Children.PDF (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Andruszkiewicz, K.; Grzybowska-Brzezińska, M.; Grzywińska-Rąpca, M.; Wiśniewski, P.D. Attitudes and Pro-Environmental Behavior of Representatives of Generation Z from the Example of Poland and Germany. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holubec, S.; Rae, G. A conservative convergence? The differences and similarities of the conservative right in the Czech Republic and Poland. Contemp. Politics 2010, 16, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, P.; Lendvai-Bainton, N. Authoritarian Neoliberalism, Radical Conservatism and Social Policy within the European Union: Croatia, Hungary and Poland. Dev. Chang. 2020, 51, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, K.; Varga, M. New Conservatives in Russia and East Central Europe; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Czaputowicz, J.; Ławniczak, K. Poland’s international relations scholarly community and its distinguishing features according to the 2014 trip survey of international relations scholars. Balt. J. Political Sci. 2015, 4, 109–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, E. Statistics of small regions—Methodological aspect. Pr. Nauk. Akad. Ekon. We Wrocławiu Zarządzanie I Mark. 1998, 8, 782. [Google Scholar]

- Zieliński, R. Confidence intervals for a binomial proportion. Mat. Stosow. 2009, 12, 809–824. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L. Family Structure, Private Transfers, and the Economic Well-Being of Families with Children. Soc. Forces 1996, 75, 269–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.I.; Ali, A.I.; Subhan, F. Empirical assessment of the impact of microfinance on quality of life. Pak. Bus. Rev. 2015, 719, 808–828. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, M.S.U.; Lu, W. What impact does microfinance have on rural livelihood? A comparison of governmental and non-governmental microfinance programs in Bangladesh. World Dev. 2015, 68, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).