Abstract

Land disputes have significantly disrupted legal order, production, and social harmony, and has been regarded as a quintessential challenge in public governance, attracting worldwide attentions from scholars. As an emblematic feature of China’s latest reform and opening-up strategy, the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) in China has experienced rapid development after entering the new era (2012–2021) alongside substantial risks and challenges, particularly regarding land disputes. Better understanding of the manifestation and formation mechanism of new characteristics of land disputes is beneficial for contemporary public governance and for achieving a high-quality development of the YREB, whose Gross Domestic Product (GDP) accounted for 46.3% of the national GDP in 2023. A total of 325,105 land dispute cases in 11 provinces or municipalities of the YREB from 2012 to 2021 were collected and analyzed. On this basis, an evaluation index system of the new characteristics of land disputes, named the overall land dispute (OLD) index, was constructed according to measurement theory by coupling the interactions of quantity, claim amounts, duration periods, and the appeal rate of land dispute. Then, the OLD index was evaluated by descriptive statistical methods, a geographic information system (GIS) spatial analysis, a center of gravity model, kernel density estimation, and Theil index methods, to reveal the new characteristics and formation mechanisms of land disputes in the YREB from 2012 to 2021. The results indicated that: (1) The OLD index exhibited a trend of an initial increase followed by a decline, indicating that land disputes in the YREB showed signs of alleviation. (2) The government’s capacity for resolving land disputes was significantly improved, as evidenced by the decline in the OLD index from 0.59 in 2018 to 0.51 in 2021. This improvement could be attributed to the effectiveness of enhanced governmental working mechanisms, regulatory standards, and the integration of digital technologies. (3) The analysis of the center of gravity model indicated that the focus of land disputes shifted westward, propelled by national policy support for upstream regions of the YREB and the need for land ecological protection. (4) The analysis of kernel density estimation indicated that regional disparities in land disputes within the YREB had declined, driven by a positive trend toward balanced regional development and rural governance. This study provides scientific insights into the new characteristics of land disputes in the YREB and guidance for policy decision making on effective land dispute management.

1. Introduction

Land disputes have significantly disrupted legal order, production, and social harmony and was regarded as a quintessential challenge in public governance, attracting worldwide attention from scholars [1]. As an emblematic feature of China’s latest reform and opening-up strategy, the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) in China has experienced rapid development after entering the new era (2012–2021), but also alongside substantial risks and challenges, particularly regarding land disputes [2]. According to statistics from the Ministry of Land and Resources of the People’s Republic of China, rural mass incidents caused by land have accounted for more than 65% of all rural mass incidents, and mass incidents of land disputes have become a prominent problem affecting social stability [3]. After 2012, China entered into a new era, as China was at the inflection point, shifting from high-speed development to high-quality development [4]. Such a new era typically accompanies intricate social structures and urbanization processes, the evolution of land use and environmental issues, the widespread application of digitization and technological advancements, shifting cultural and societal values, as well as adjustments in laws and policies. The Chinese government unveiled the “Outline of the Yangtze River Economic Belt Development” in October 2016, reflecting the region as possessing the greatest developmental potential within China [5]. A better understanding of the manifestation and formation mechanism of new characteristics of land disputes in this new era is beneficial for contemporary public governance and for achieving a high-quality development of the YREB, whose GDP accounted for 46.3% of the national GDP in 2023.

The land issue is one of the most controversial issues [6], which has attracted considerable worldwide attention. The concept of land disputes was a subject of considerable debate among scholars. Campbell et al. (2000) defined land disputes as conflicts that arise during the process of land resource utilization [7]. Alston et al. (2000) described land disputes as conflicts or property infringements occurring between farmers, the government, and other stakeholders over land ownership and usage rights [8]. Wehrmann (2008) believed that land dispute was a social fact involving at least two parties [9]. In fact, scholars have not established a clear conceptual distinction between land disputes and land conflicts. However, compared with land conflicts, which are often framed in socio-political terms, land disputes are typically characterized by more legalistic language [10]. Although there is no universally accepted definition of land disputes, the academic consensus is that they fundamentally involve the contestation of land-related interests [11]. Current studies on the characteristics of land disputes often involve theoretical discussions based on regional investigations. For example, Kansanga et al. (2019) examined three case studies in the Upper West Region of Ghana and found that customary land boundary conflicts between communities were intensifying [12]. Mugizi and Matsumoto (2021) conducted household surveys in post-war Northern Uganda and concluded that land conflicts negatively impacted agricultural productivity [13]. Bekele et al. (2022) used cross-sectional household surveys of 870 households in Ethiopia and discovered that land conflicts increased with land investment [14]. Recently, the widespread application of quantitative modeling methods has inspired academic research on the spatiotemporal evolution of land disputes. For instance, Lin et al. (2018) utilized exploratory spatial data analysis to reveal the spatiotemporal characteristics of land expropriation conflicts in China from 2006 to 2016 [15]. Tan et al. (2021) employed descriptive statistics, a GIS spatial analysis, and Markov chains to uncover the spatiotemporal evolution of land contract disputes in the YREB from 2016 to 2021 [16]. However, these studies typically summarized the characteristics of land disputes through theoretical discussions or quantitative analyses of the number of land disputes, neglecting the fact that land disputes are an abstract concept encompassing various attributes such as quantity, claim amounts, and duration periods. It is difficult to establish a comprehensive and objective overall understanding of the characteristics of land disputes and their underlying dynamics from a single dimension measure.

Currently, quantitative modeling of social conflict risk has become a standard approach in social conflict research [17], e.g., the Global Conflict Risk Index [18], the Financial Risk Culture Intensity Index [19], and the Internal Armed Conflict Risk Index [20]. These studies provided valuable insights for the quantitative modeling of land disputes, but few were devoted to constructing the quantity index for land disputes when considering multi-dimensional factors and applying the index for further study. In this study, a total of 325,105 land dispute cases in 11 provinces or municipalities of the YREB from 2012 to 2021 were collected and analyzed. The case numbers, claim amounts, and duration were extracted from the case repository to construct an extensive and substantial database of land dispute cases. On this basis, an evaluation index system of the new characteristics of land disputes, named the overall land dispute (OLD) index, was constructed according to measurement theory by coupling the interactions of quantity, claim amounts, duration periods, and appeal rate of land disputes. Then, the OLD index was evaluated by descriptive statistical methods, a GIS spatial analysis, a center of gravity model, kernel density estimation, and Theil index methods to reveal the new characteristics and formation mechanisms of land disputes in the YREB from 2012 to 2021. As an important branch of social conflict and dispute studies, the novel research approaches and methodologies proposed in this study on land dispute characteristics provide valuable reference paradigms and research experiences for the investigation of other social conflicts and disputes.

2. Study Area, Data, and Methods

2.1. Study Area

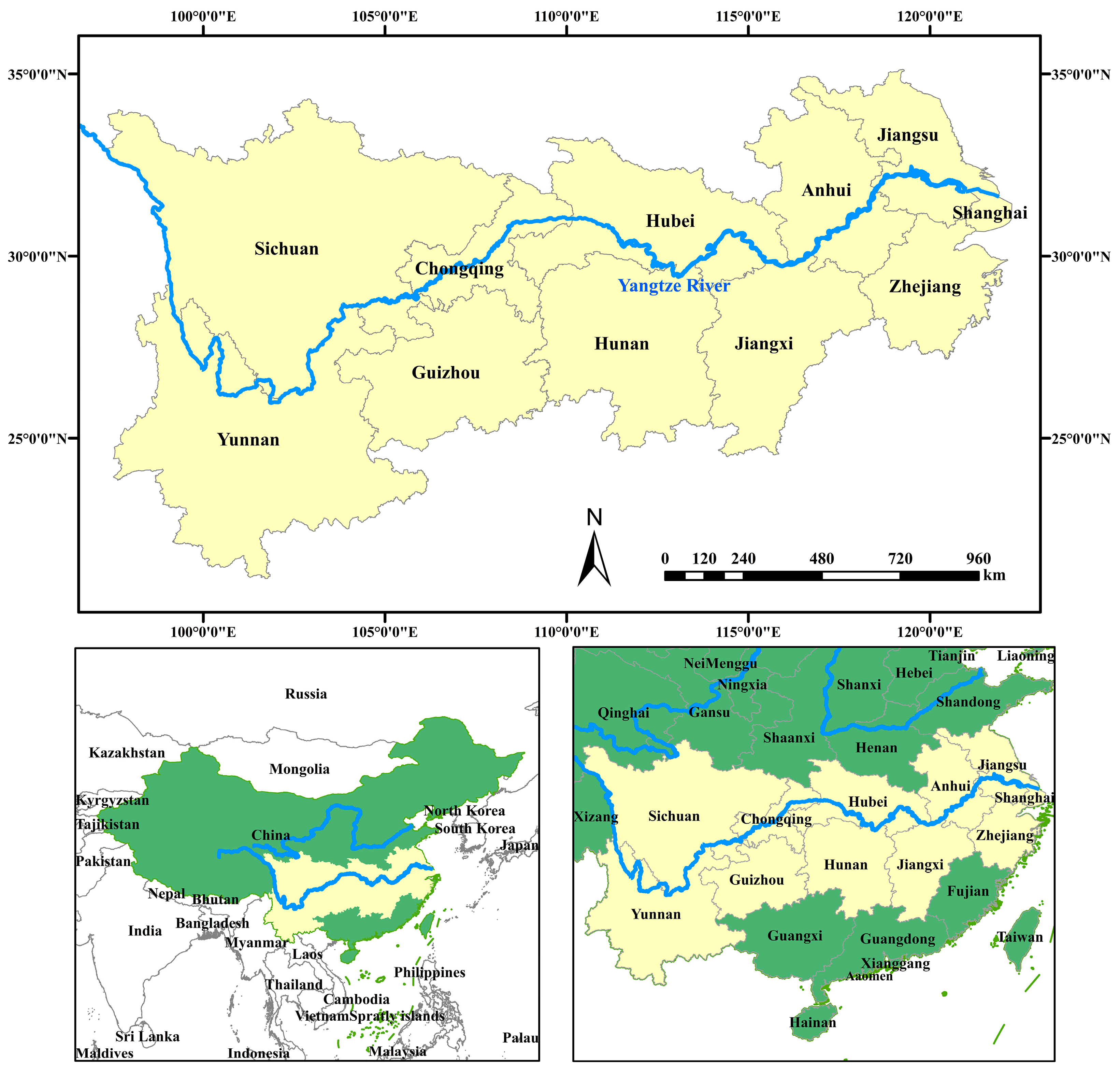

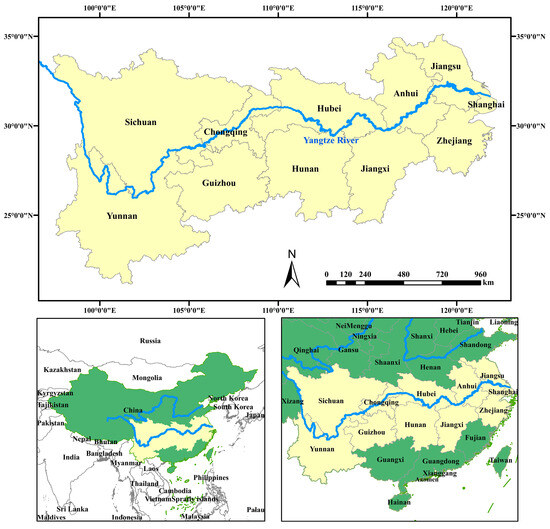

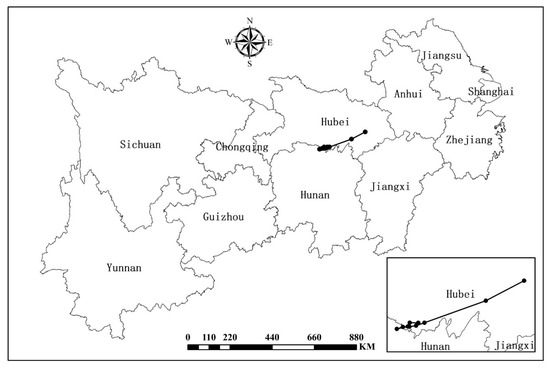

The Yangtze River, renowned as the third longest river globally and the lengthiest within China, holds historical significance as the cradle of Chinese civilization and is often referred to as the “golden waterway”. The Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) is located alongside the Yangtze River, covering nine provinces—Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Hubei, Hunan, Sichuan, Yunnan, and Guizhou—and two cities—Shanghai and Chongqing—as shown in Figure 1. The YREB spans approximately 2.05 million square kilometers, constituting 21% of China’s territory [21]. In 2022, the YREB’s GDP surged to CNY 56 trillion, contributing to 46.5% of the national economy, with a per capita GDP exceeding the national average by CNY 7541, totaling CNY 93,239. Moreover, the YREB is home to approximately 599 million inhabitants, representing 42.9% of China’s total population [22].

Figure 1.

Study area.

In recent years, China has promulgated a series of policy directives to propel the development of the YREB, including the “Guiding Opinions on Leveraging the Golden Waterway to Promote the Development of the Yangtze River Economic Belt” (2014) and the “Outline of the Development Plan for the Yangtze River Economic Belt” (2016). As part of China’s new wave of reform and opening up, coupled with the high-quality development strategies, the YREB has been treated as a pivotal area for national strategic development. Nevertheless, with the rapid economic growth in the accelerated urbanization process, the prominence of land disputes has arisen with the appreciating land values. Thus, a better understanding of the manifestation and formation mechanism of new characteristics of land disputes is beneficial for contemporary public governance and for achieving high-quality development of the YREB.

2.2. Data

The land dispute case dataset utilized in this paper was obtained from China Judgment Online (https://wenshu.court.gov.cn, accessed on 1 March 2023). The data acquisition process involved keyword searches for essential case documents using terms such as “land dispute”, “land contract management”, “land contract agreement”, “land transfer”, “land expropriation”, and “distribution of land expropriation compensation”. Subsequently, regular expressions were employed to parse and extract requisite information for the study, including case causes, trial periods, judicial reasoning, and verdicts. This paper adopted the provincial level within the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) as its research scale, encompassing a total of 11 provinces or municipalities. The temporal scope was restricted to the years 2012 to 2021, resulting in the accumulation of 325,105 land dispute cases.

The socio-economic data utilized in this paper of formation mechanisms were sourced from a variety of official statistical publications, including the China Rural Operation and Management Statistical Yearbook (2012–2018), China Rural Policy Reform Statistical Yearbook (2019–2021), China Statistical Yearbook (2013–2022), China Environmental Statistical Yearbook (2013–2022), China Natural Resources Statistical Yearbook (2013–2022), China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook (2013–2022), China Urban Statistical Yearbook (2013–2022), China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook (2013–2022), and China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook (2013–2022). Additionally, data from the official statistical yearbooks of the 11 provinces (or cities) within the Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB), as well as publicly available data from the judicial department websites of the corresponding years, were incorporated. Due to discrepancies in statistical methodologies and data availability, obtaining complete datasets for certain provinces and municipalities posed challenges. In such instances, interpolation methods were employed to address missing data points.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Calculation of the Land Dispute Index

To evaluate the new characteristics of land disputes in the YREB comprehensively and quantitively, this paper utilizes the comprehensive index method to establish a new characteristic evaluation index system based on the textual information from the constructed land dispute case database and the current status of the YREB [23]. Four indicators, including the land dispute quantity, claim amounts, duration, and appeal rate, are coupled for the calculation of the land dispute index as follows:

where represents the land dispute index for province (or city) in year . , , , and denote the quantity and claim amounts, duration, and plaintiff’s appeal rate in province (or city) in year , respectively.

As the quantity of land disputes, claim amounts, duration, and appeal rate increase, the magnitude of land disputes also grows. Following the principle of multiplying similar factors and adding dissimilar ones, this study defines the expression for the land dispute index as:

where , , , and represent the weights of the quantity, claim amounts, duration, and plaintiff’s appeal rate, respectively. Adopting the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) method [24], the weights of the aforementioned four indicators are calculated as 50.54%, 39.29%, 4.35%, and 5.82%, respectively. serves as the standardized adjustment coefficient. The variable ranges between 0 and 1.

This paper calculated the land dispute index of various provinces (or cities) in the YREB from 2012 to 2021 based on Equation (2). Subsequently, the spatiotemporal evolution of the land dispute index was calculated for analyzing the new characteristics of land disputes in the YREB.

2.3.2. The Center of Gravity Model

The center of gravity model was employed for the examination of the spatial movement and evolutionary processes of the specific elements within a defined geographical area [25]. This paper employed ArcGIS10.2 software to achieve a spatial visualization and quantitative analysis of the evolution patterns of land dispute centroids in the YREB. Assuming each province (or city) within the YREB constitutes a uniformly textured plane, geographic positions of provinces (or cities) were represented by latitude and longitude. Utilizing the center of gravity model, the centroids of land dispute indices for various provinces (or cities) within the YREB were computed over the years, thereby deriving the spatiotemporal evolution of land dispute centroids. The center of gravity model is calculated by:

where Xt and Yt represent the longitude and latitude coordinates, respectively, of the centroid of land disputes in the tth year; Pti denotes the land dispute index of province (or city) i. xi and yi denote the longitude and latitude coordinates of the geometric center of province (or city) i, respectively.

2.3.3. Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel density estimation (KDE) is a non-parametric method used for estimating probability density curves, and it is capable of describing the distributional shape of random variables with continuous density curves [26]. It is widely employed in studying the dynamic evolution characteristics of sample data [27,28]. The equation of the kernel density function for the land dispute index is:

where f (x) represents the density function of the land dispute index. x denotes the mean and N represents the number of observations; Xi signifies independently and identically distributed observations; K(·) stands for the kernel function, and h denotes the bandwidth. Additionally, the kernel function must satisfy conditions , , , . The Gaussian kernel function, adopting a random variable x following a normal distribution, was employed in this study. The expression for the Gaussian kernel function is:

In this paper, the regional disparities in land disputes in the YREB was evaluated based on the distribution analysis of the kernel density curve of the land dispute index. Within the overall shape of the variable distribution, the height and width of peaks indicate the magnitude of disparities, while the number of peaks reflects polarization phenomena [29].

2.3.4. Theil Index

The Theil index, proposed by the economist Theil in the 1960s, is an important metric for measuring income disparities among individuals or regions [30]. It is widely used in various fields, such as land use efficiency or the distribution of social resources [31,32]. This paper calculated the Theil index for economic development, rural governance level, and land dispute index by

where T represents the overall Theil index for the economic development level, rural governance level, and land dispute index within the YREB, T ∈ [0, 1]. A higher value of T indicates greater overall disparity, while a lower value suggests lesser disparity. Sq denotes the specific values of these indicators for each province or municipality, signifies the average value of these indicators, and n represents the number of provinces (or cities) within the YREB.

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Evolution of the Land Dispute Index

3.1.1. Temporal Evolution

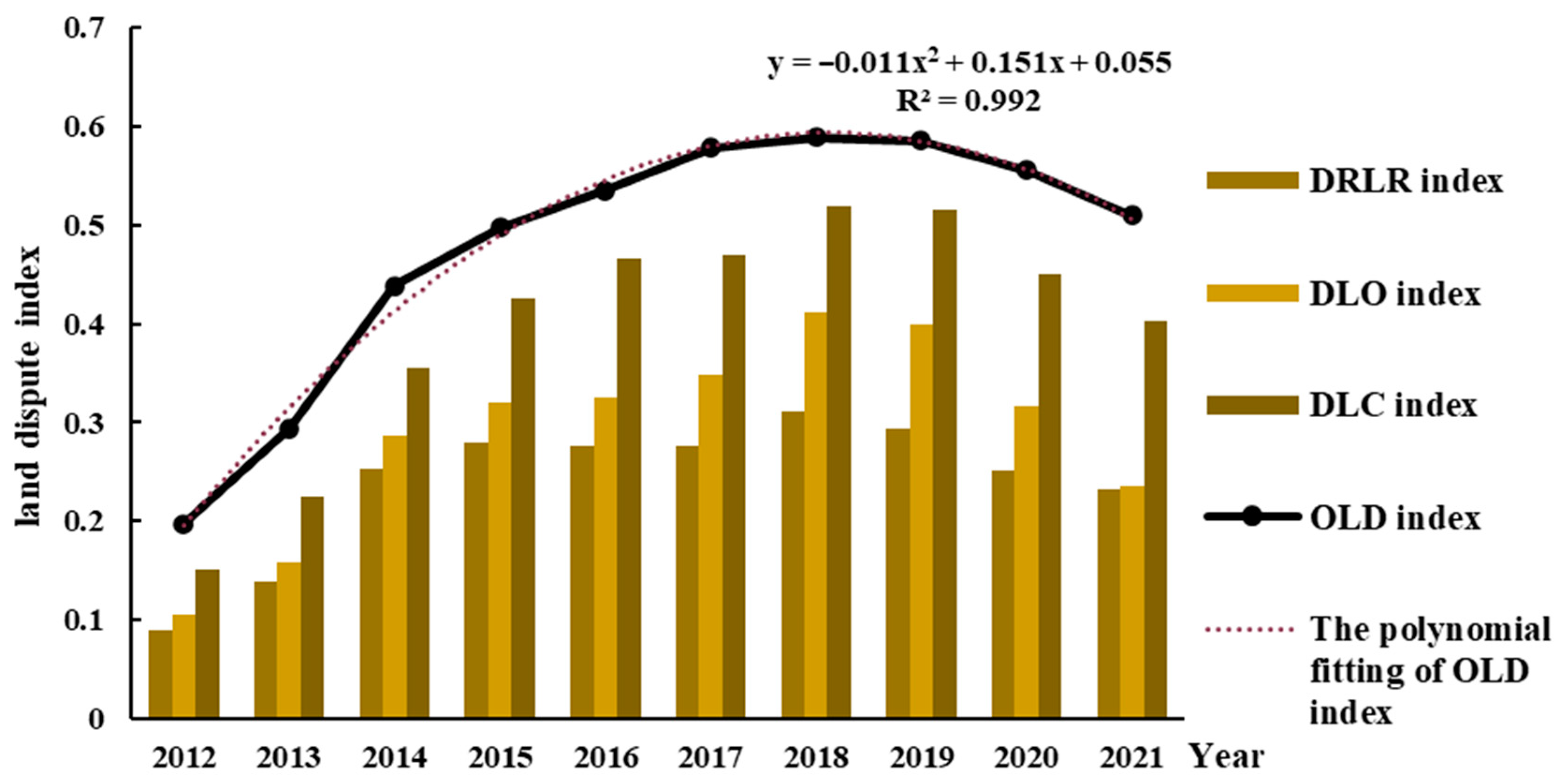

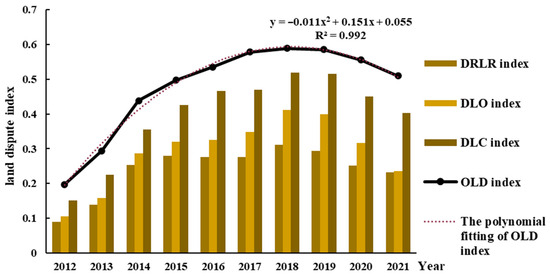

The overall land dispute (OLD) was classified into three categories in this study, including disputes of requisited land remuneration (DRLR), disputes of land ownership (DLO), and disputes of land contract (DLC) [11]. The temporal evolution of the land dispute index (LDI) for the YREB from 2012 to 2021 is presented in Figure 2, including the indicators of the overall land dispute and the categorical indicators of DRLR, DLO, and DLC. The results indicated that the OLD index of the YREB increased from 0.198 in 2012 to 0.590 in 2018, which was also the peak value during the research period, and then decreased to 0.510 at the end of 2021. The value of the OLD index increased by 2.58 times, which increased from 2012 to 2018 at the beginning and then decreased from 2018 to 2021. The polynomial relationship model for the OLD index was fitted as follows:

where y is the OLD index and x refers to the year. The R2 of the fitted equation is 0.992, showing a reliable matching. It is worth noting that although the OLD index has begun to decline in the new era; its absolute value was still above 0.510 and remained relatively high.

y = −0.011x2 + 0.151x + 0.055

Figure 2.

The indices of OLD, DRLR, DLO, and DLC in the Yangtze River Economic Belt from 2012 to 2021.

Specifically, the DRLR index fluctuated upward from 0.090 in 2012 to 0.311 in 2018 and then downward to 0.233 in 2021; the DLO index increased from 0.105 in 2012 to 0.412 in 2018 and then decreased to 0.235 in 2021; the DLC index increased from 0.152 in 2012 to 0.519 in 2018 and then decreased to 0.403 in 2021. The index value of DLCs was the largest, followed by that of DRLR and DLO, all of which show the same tendency as the OLD index from 2012 to 2021. However, it should be noted that the conflicts caused by the DLCs were more serious and, which suggests that they require more attention.

3.1.2. Spatial Evolution

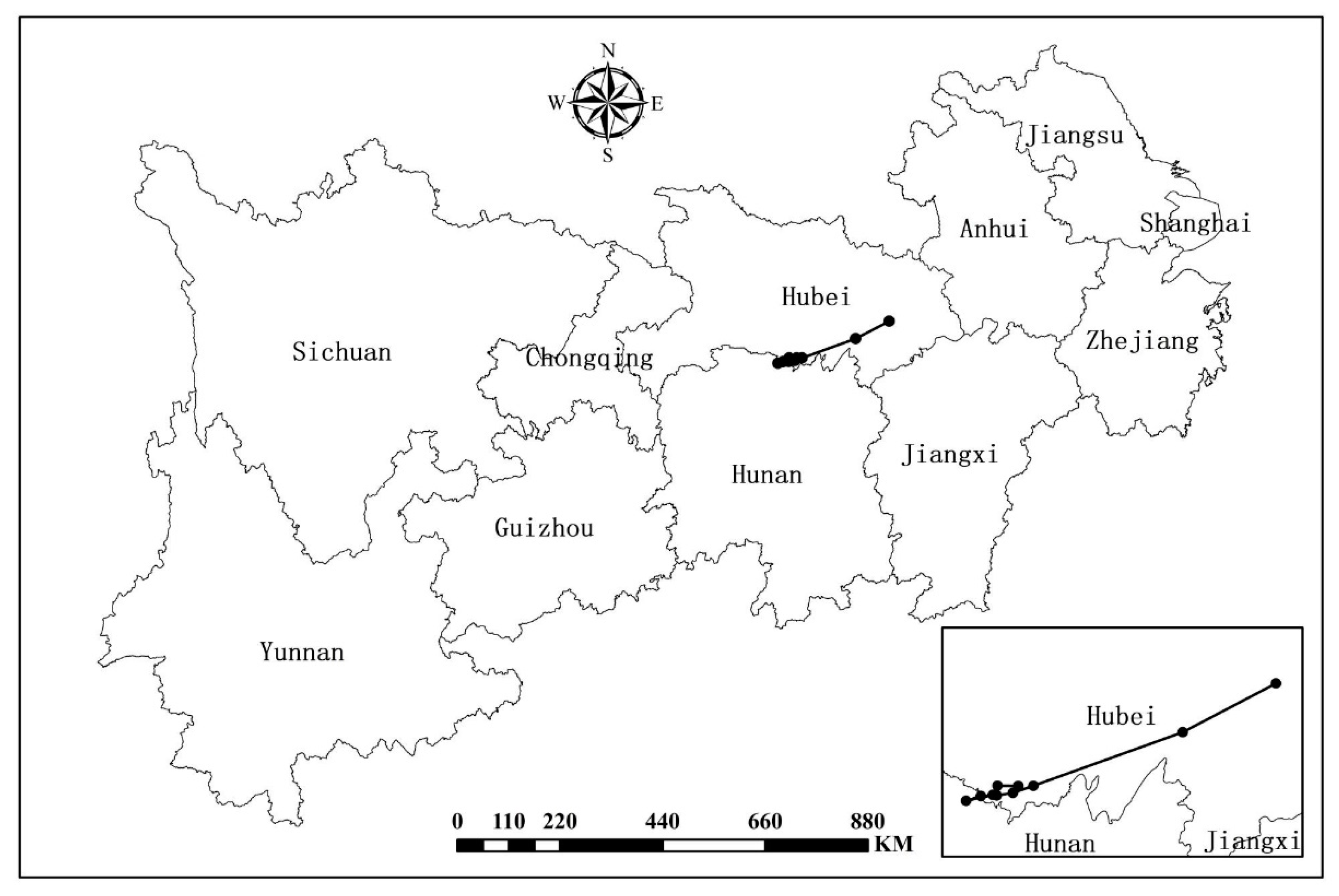

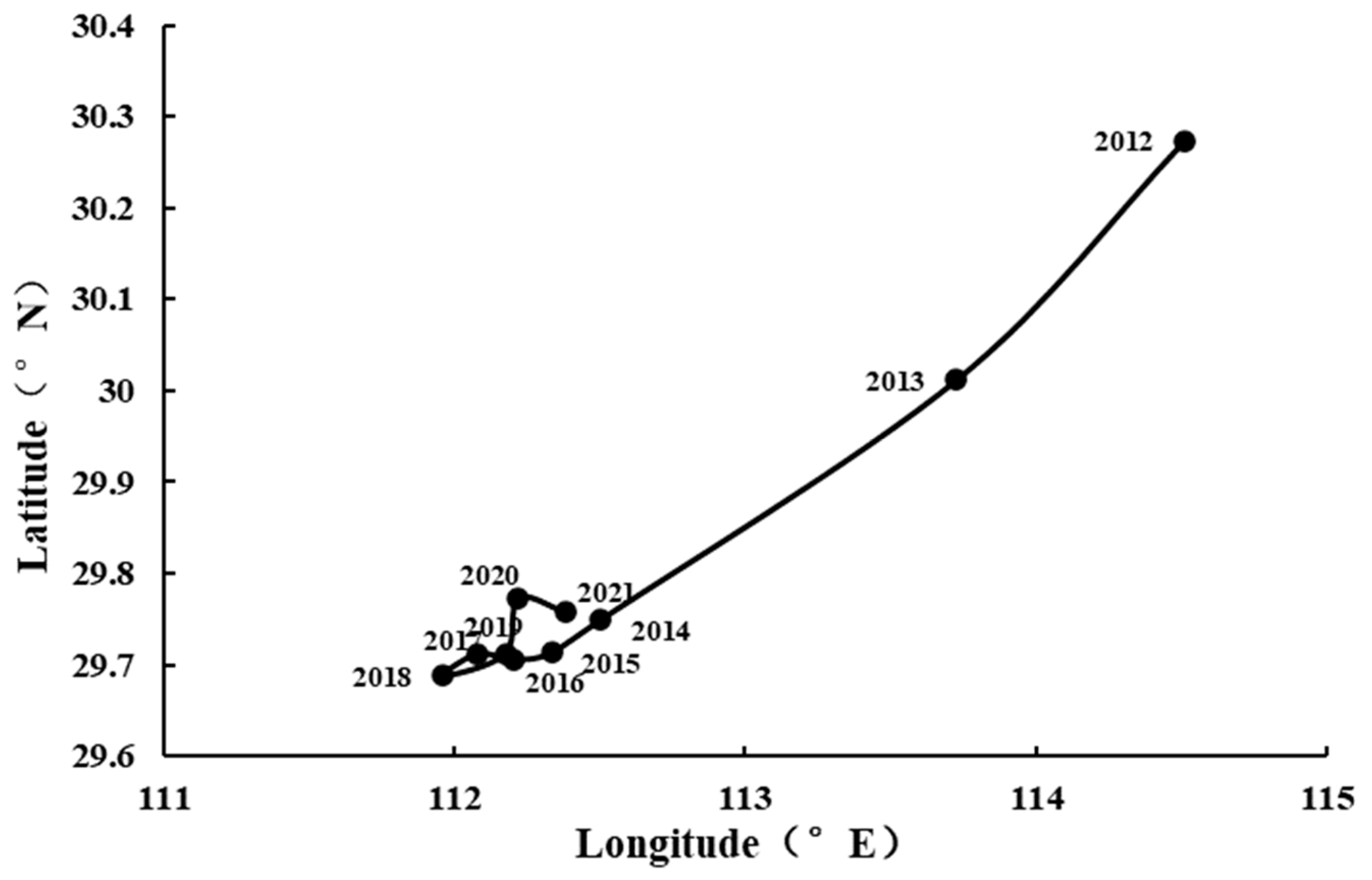

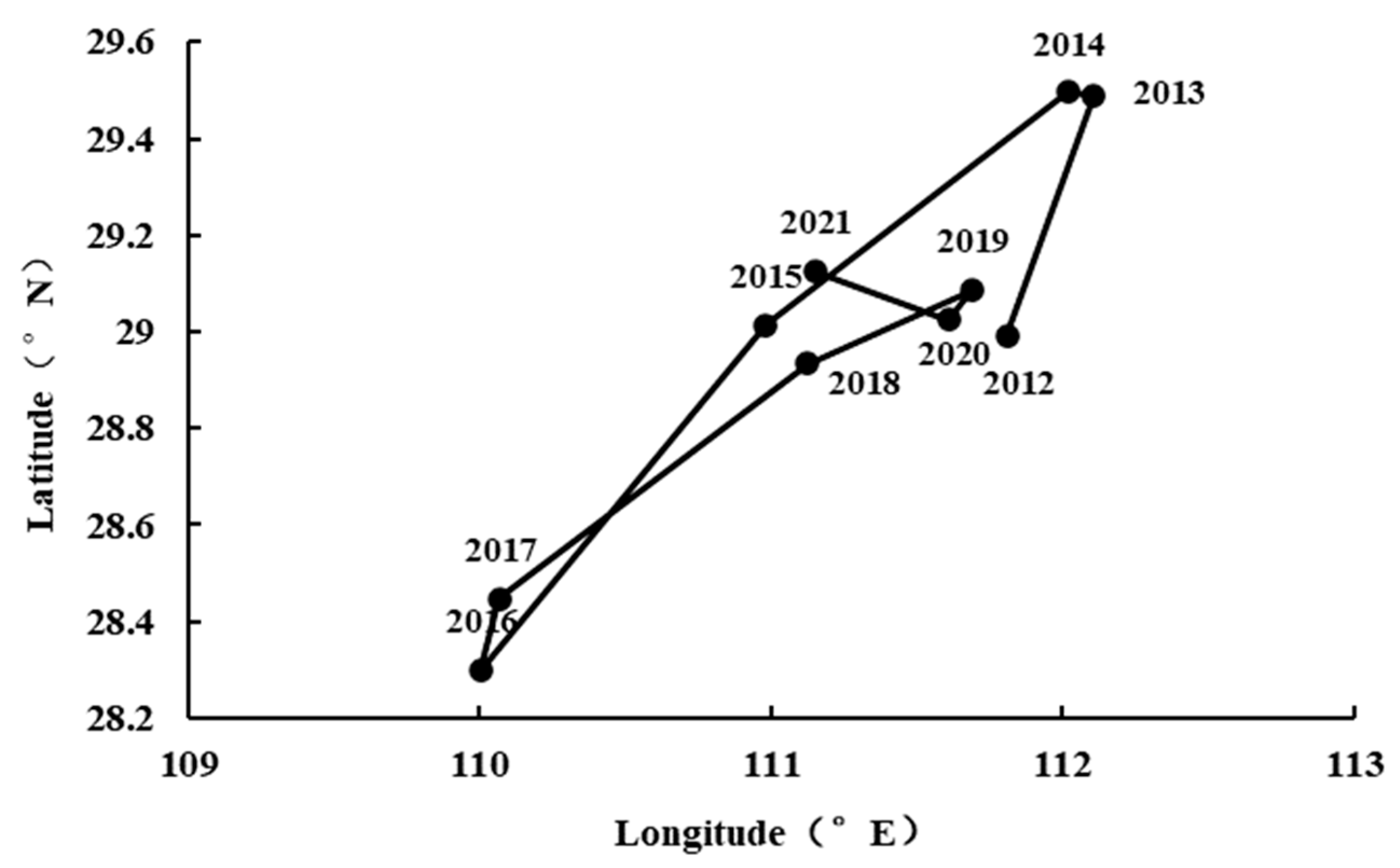

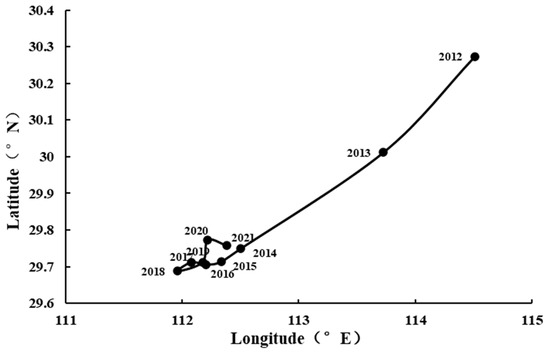

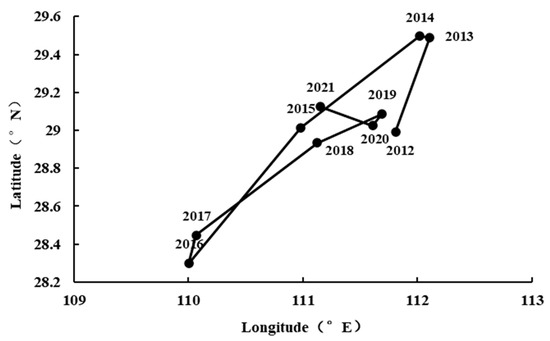

The focus of the OLD index in the YREB from 2012 to 2021 was evaluated by a center of gravity approach and illustrated on the provincial (city) map, as shown in Figure 3. And the focus evolution of longitude and latitude was presented in Figure 4. The results indicated that the focus of the OLD index in the YREB moved from Jiangxia district, Wuhan, Hubei Province, in 2012 to Gong’an County, Jingzhou, Hubei Province, China, in 2016. The moving trajectory covered a distance of 167.4 km along the southwest direction during this period, and the largest moving distance per year occurred in 2013–2014. From 2016 to 2018, the focus of the OLD index in the YREB moved from Gong’an County, Jingzhou, Hubei Province, to Linli County, Changde, Hunan Province. Since then, the focus of the OLD index in the YREB moved back to Gong’an County, Jingzhou, Hubei Province, China. The moving trajectory covered a distance of 24.18 km along the northwest direction initially and then the southwest direction during this period. The moving trajectory initially covered a distance of 41.63 km along the northeast direction and then the southeast direction during this period. Generally speaking, during the period from 2012 to 2021, the focus of the OLD index in the YREB moved westward significantly with a slightly southward tendency.

Figure 3.

The migration trajectory of the focus of the OLD index in the Yangtze River Economic Belt from 2012 to 2021.

Figure 4.

Details of the migration trajectory of the focal point of land disputes in the Yangtze River Economic Belt from 2012 to 2021.

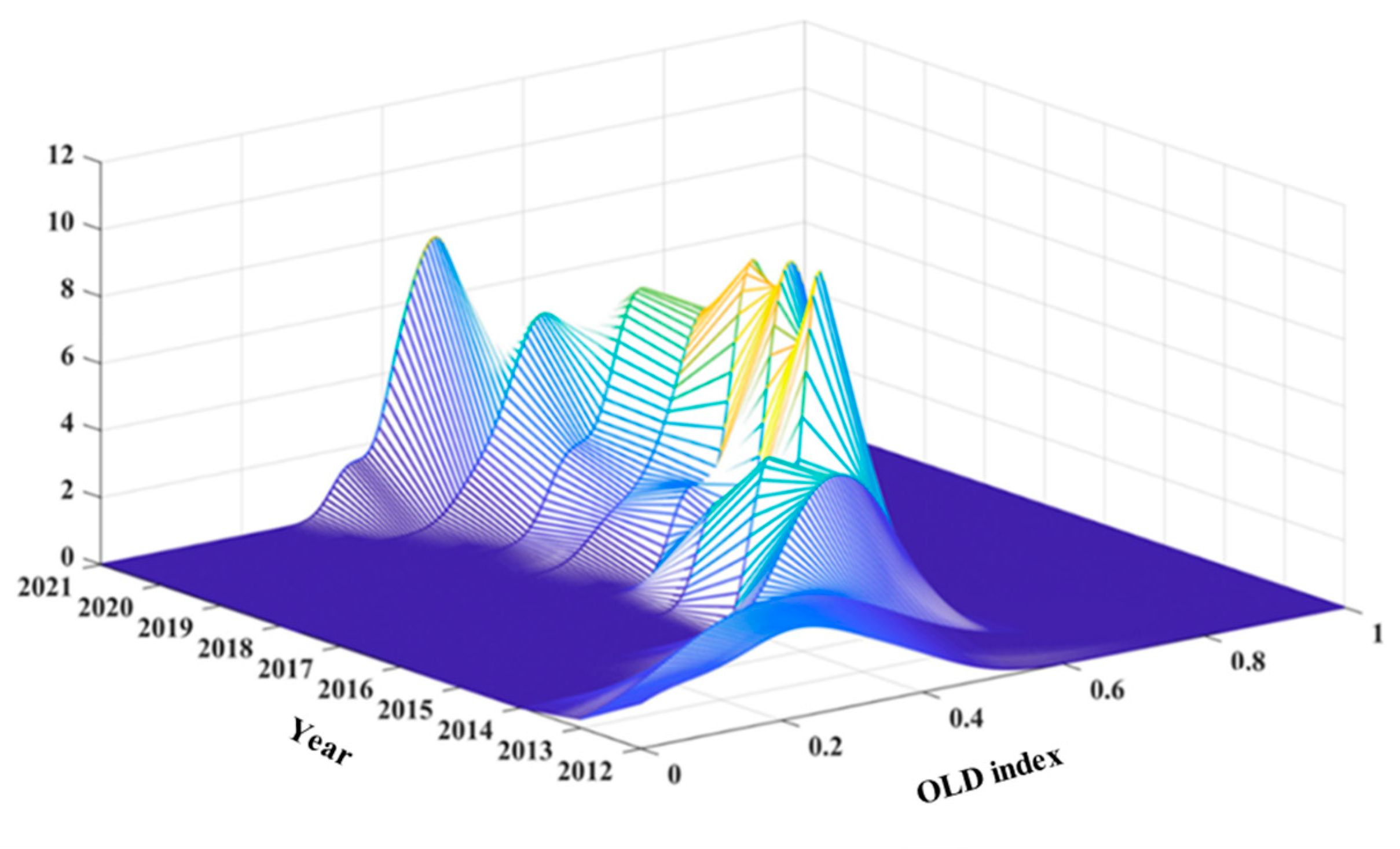

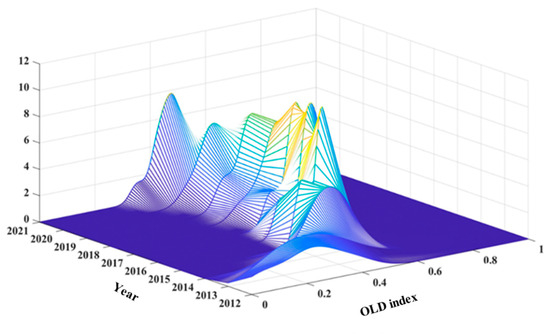

The kernel density estimation of the OLD index in the YREB from 2012 to 2021 was calculated and presented in Figure 5. The center of the kernel density distribution moved to the right over time during 2012–2018, and then to the left during 2018–2021, indicating that the OLD index initially increased and then decreased during the research period. Overall, the peak value of the kernel density estimation showed a fluctuating upward tendency, which rapidly increased during 2012–2018 and gradually decreased during 2018–2021, rebounding during 2020–2021. The fluctuating tendency indicated that the regional disparity of the OLD index initially decreased, then increased, and then decreased again. In addition, only one peak was presented in the curve of the kernel density estimation in the early stage of the research period, but there were two peaks, including one main peak and one secondary peak, after 2017. During the research period, there was an unclear polarization phenomenon in land disputes within the YREB. Generally speaking, during the period from 2012 to 2021, there was an unclear polarization phenomenon in land disputes within the YREB, but regional disparities have been generally decreased.

Figure 5.

Kernel density estimation of the OLD index in the YREB from 2012 to 2021.

3.2. Analysis of New Characteristics and Formation Mechanisms

3.2.1. Land Disputes Have Been Alleviated

For a long time, land disputes have shown an increasing trend in terms of quantity, scale, and degree, exerting increasingly significant impacts on social and political stability [33], which were prone to incite collective events, posing as the foremost challenge to rural social stability and development [34]. However, the temporal evolution analysis on the spatiotemporal evolution of the land dispute index of the YREB showed a significant decline in the land dispute index in the new era. The results could be concluded as a new characteristic that the land disputes have been alleviated in the new era. The formation of this new characteristic is attributed to the coupled effects of the continuous optimization of land utilization structure, gradual improvement of land utilization systems, and ongoing enhancement of public legal awareness in the transition of the YREB towards high-quality development.

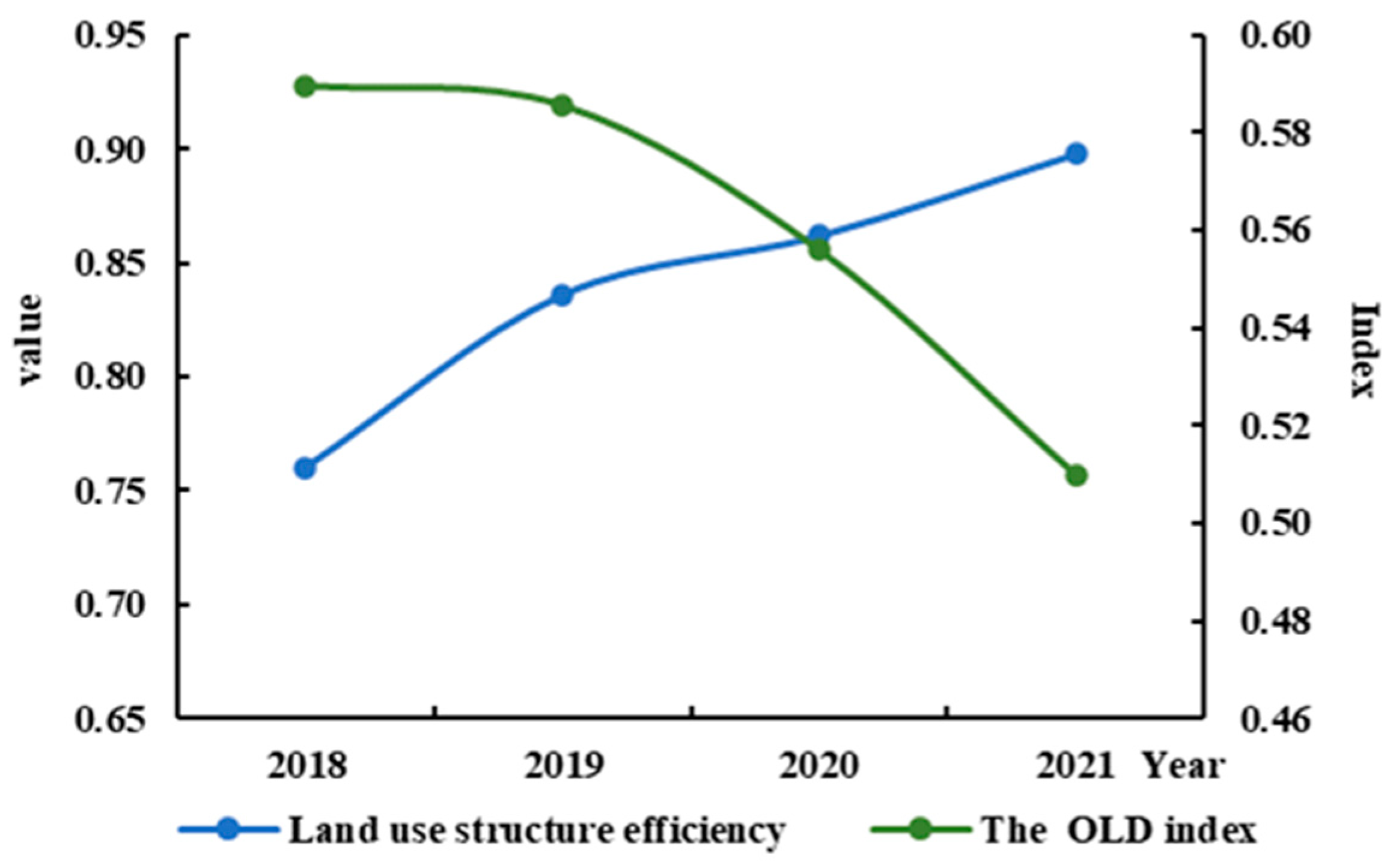

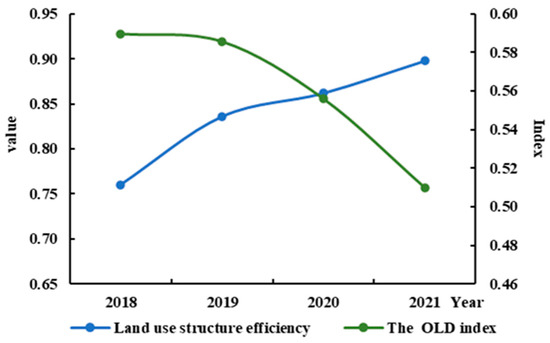

(1) The optimization of land utilization structure has led to the alleviation of conflicts arising from land disputes. The stakeholder theory posited that the fundamental reason of conflicts lays in the divergent interests of various parties and the local government’s need to balance the needs of all stakeholders through rational resource allocation and management [35]. The strategically planned land use and optimizing land utilization structure were beneficial for balancing the land utilization needs of all stakeholders, including local governments, residents, developers, farmers, and so on [36], thereby reducing potential risks of land disputes. In the new era, various local governments of the YREB continuously optimized the land structure within administrative boundaries through new policy implementation including, adjusting land use planning, activating idle land, and addressing land pollution. For example, the Government of Zaoyang City in Hubei Province issued the “Management Measures for the Change of Use of State-Owned Construction Land in Zaoyang City”; the Natural Resources and Planning Bureau of Huai’an City in Jiangsu Province exceeded its targets for revitalizing and disposing of idle land, and fifteen departments in Mianyang City, Sichuan Province, jointly released the “14th Five-Year Plan for Soil Pollution Prevention and Control in Mianyang City” [37]. According to the index system proposed by Zhu et al. (2021) [38], the average efficiency of land utilization structure in the YREB during the period of 2018–2021, when the land dispute index declined, is calculated and presented in Figure 6. It was evident that the average efficiency values of land utilization structure in the YREB increased with time and was negatively correlated with the OLD index. The results indicated that the land utilization structure in the YREB was becoming more reasonable and the land use demands of various industries were better balanced, thereby alleviating land disputes.

Figure 6.

Land use structure efficiency and OLD index in the YREB from 2018 to 2021.

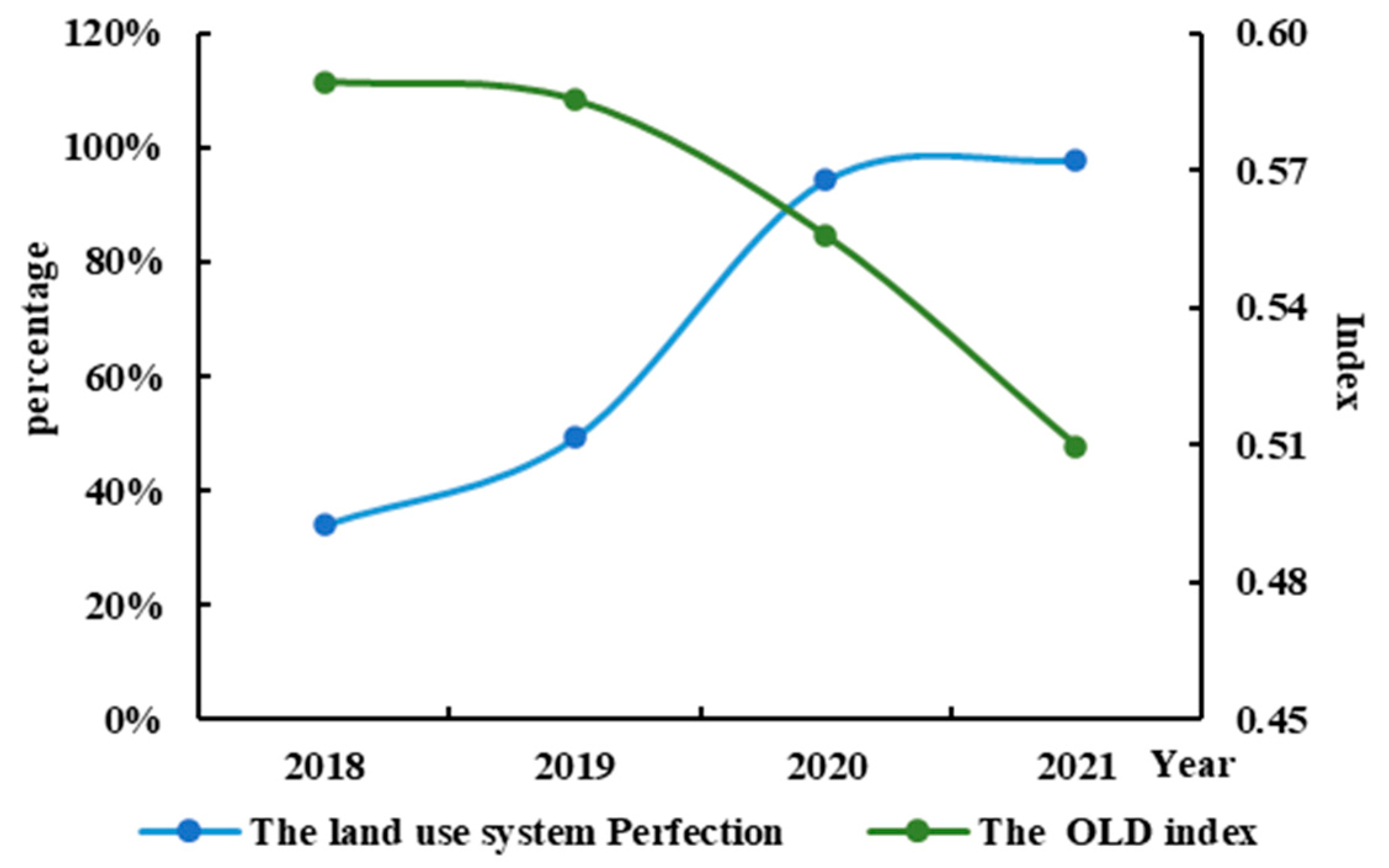

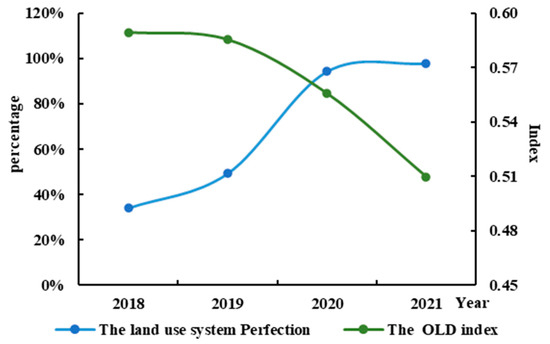

(2) The improvement of land utilization systems led to the alleviation of land disputes. According to institutional change theory, institutional change begins with society’s perception of problems. When existing institutional frameworks fail to effectively address or adapt to new social issues, the reduction of social conflicts can be achieved through adjustments and improvements to the institutions [39]. The continuous adaptation of land utilization systems to the changes in social economy, technology, and culture can effectively advance the smooth operation of the land market and thereby lead to the alleviation of land disputes. Previous studies have pointed out that the deficiencies in land regulations, e.g., the deficiencies in the land acquisition system, the ambiguity in agricultural land ownership, the incomplete contracting rights of agricultural land, the ambiguous delineation of collective member entitlements, the deficiencies in land conflict mediation systems, etc., were important causes of land disputes in the past [40]. After entering the new era, the utilization system in China was improved continuously, including establishing the separation system of ownership, contracting rights, and management rights for rural land; extending the second round of land contracting for another thirty years upon expiration; promoting the market entry of collectively owned commercial construction land and reforming the homestead system; improving the rural land property rights transfer and transaction system; and so on [41]. Furthermore, the percentage of villages in the YREB that have completed property rights system reforms was adopted in this study as a measuring index of perfection in land utilization systems, which is calculated and presented in Figure 7. The perfection of land utilization systems in the YREB has been significantly improved, with an increase of 187.7% over the four-year period, while the land dispute index was continuously decreased by about 13.50%. The results indicate that as the land utilization systems in the YREB was improved contentiously, more flexible, fair, and sustainable solutions to land utilization have been achieved, thereby alleviating land disputes in the YREB.

Figure 7.

Land use system perfection and OLD index in the YREB from 2018 to 2021.

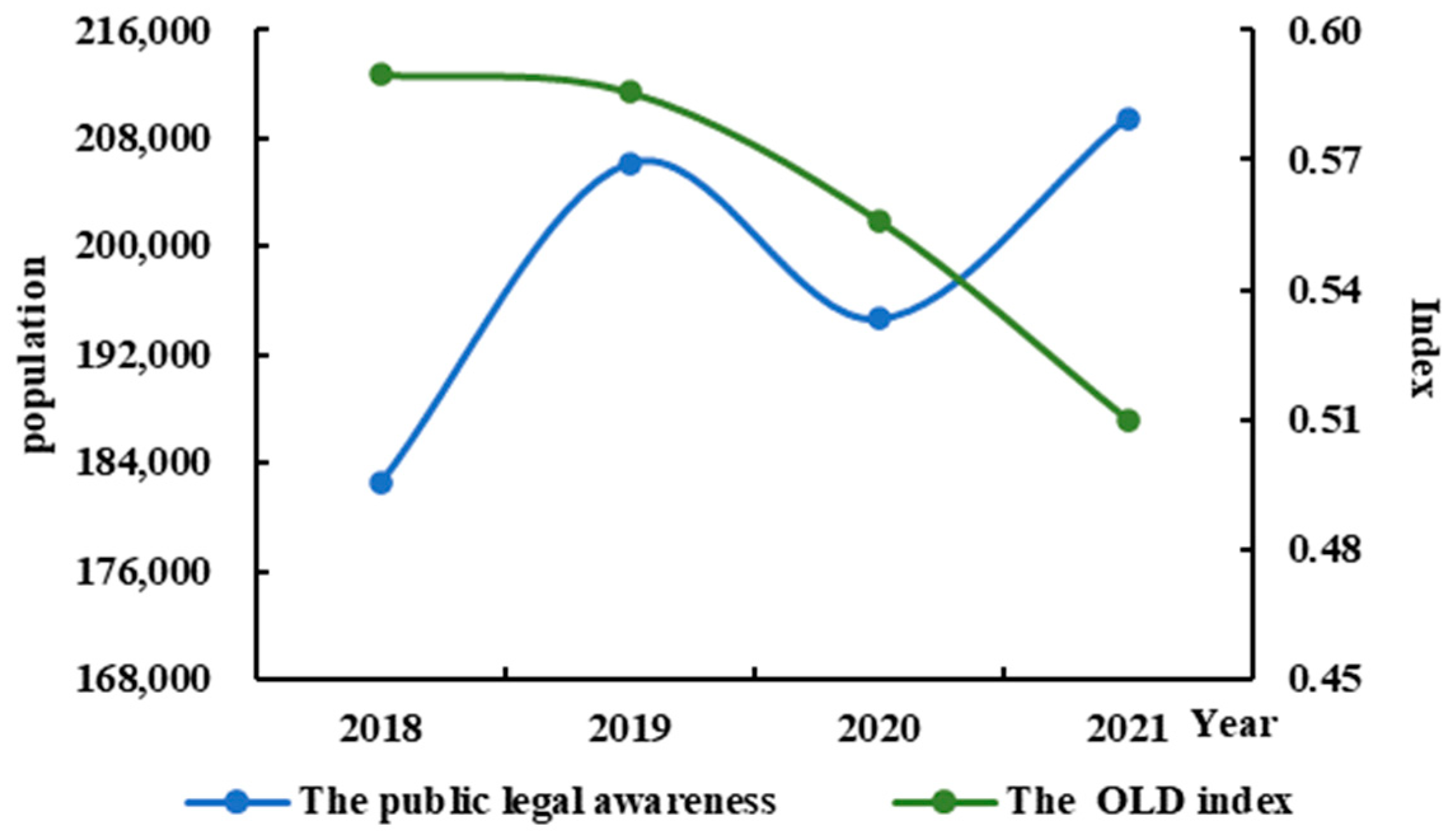

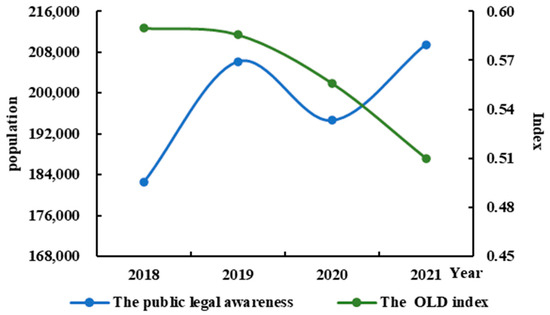

(3) Enhancing public legal awareness facilitated the alleviation of land disputes. The legal sociology theory by Max Weber posited that enhancing public legal awareness allowed individuals to a deeper understanding that the law was not merely a transcendent set of rules but rather a product of collective social organization. This awareness was helpful for understanding the legitimacy and authority of law, thereby urging them to abide by regulations and restrain their own unlawful behaviors [42]. In land utilization activities, enhancing public legal awareness could assist individuals in better understanding the societal background and purposes of the land regulations, which could strengthen the normative cognition of lawful land utilization activities, thus alleviating land disputes. Inspired by the new era’s rural revitalization strategy, various local governments in the YREB were eager to enhance farmers’ legal awareness. For instance, in Pengxi County, Sichuan Province, the “Rule of Law Services for Rural Revitalization” tour has been launched to provide a common show on a popularization performance with vivid and simple language. Additionally, six departments in Yunnan Province jointly formulated the “Three-Year Action Plan for Legal Propaganda and Education to Support Rural Revitalization”, providing legal guarantees for rural revitalization. Meanwhile, the Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of Jiangxi Province has launched the “Rural Revitalization, Legal Primacy” for popularizing law, which ignited the public enthusiasm of legal learning throughout the province’s rural areas. According to Silbey (2005) [43], the number of practicing lawyers was adopted as the index of public legal awareness and was calculated. As shown in Figure 8, the public legal awareness in the YREB increased with time in 2018–2021, showing a negative correlation with the OLD index. The results indicated that as public legal awareness improved, the land utilization activities of the farmers were further regulated, which significantly alleviated land disputes.

Figure 8.

The public legal awareness and OLD index in the YREB from 2018 to 2021.

3.2.2. The Capacity for Resolving Land Disputes Has Been Enhanced

The temporal evolution of the land dispute index from 2012 to 2021 in Section 3.1.1 showed a significant decline during the new era, which could be concluded as the governmental capacity for resolving land disputes having been enhanced. The reason for this new characteristic in the new era lay in the continuous refinement of governmental operation, the gradual application of digital technologies into governance practices, and the enhancement of governmental regulatory standards.

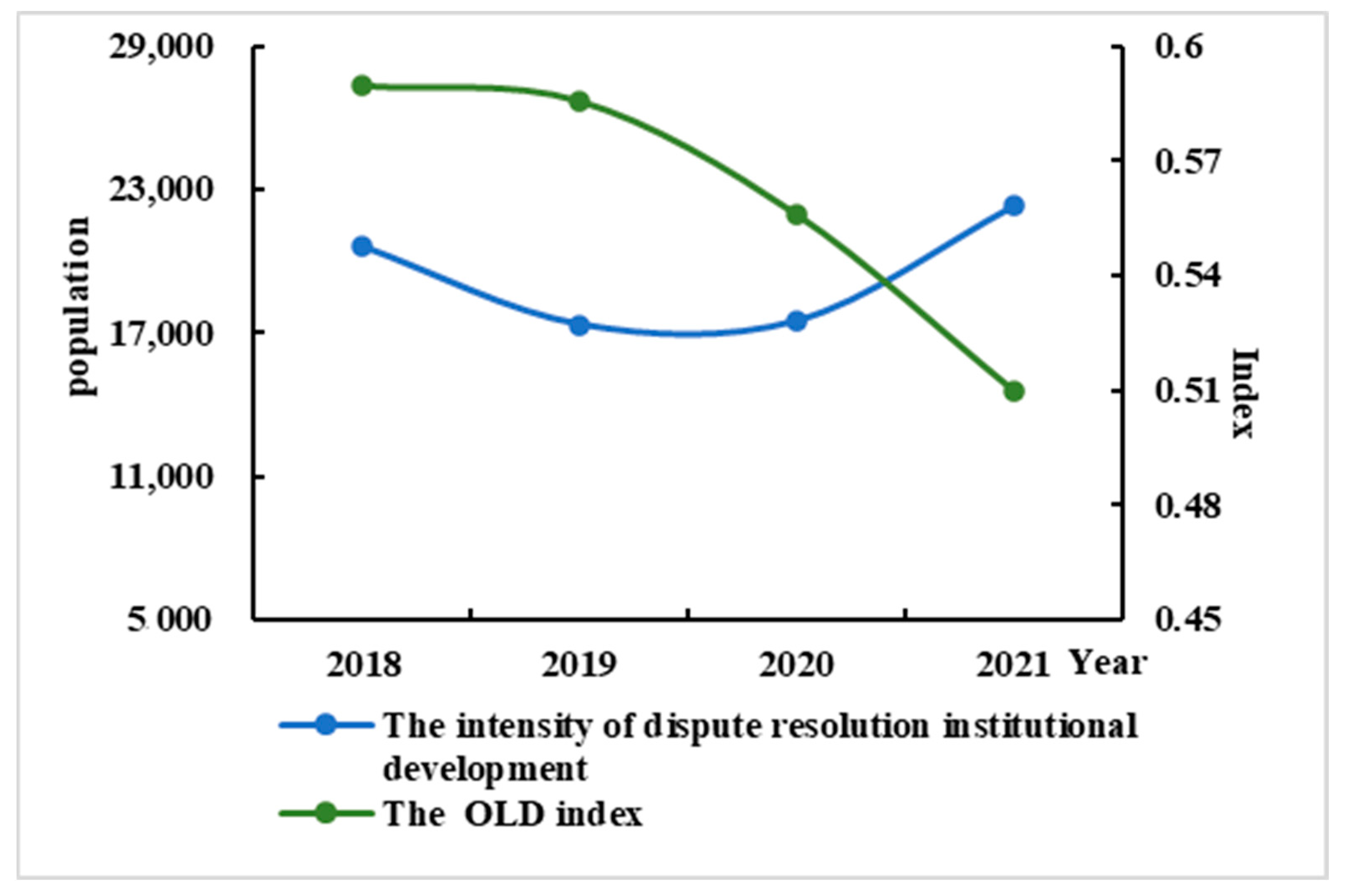

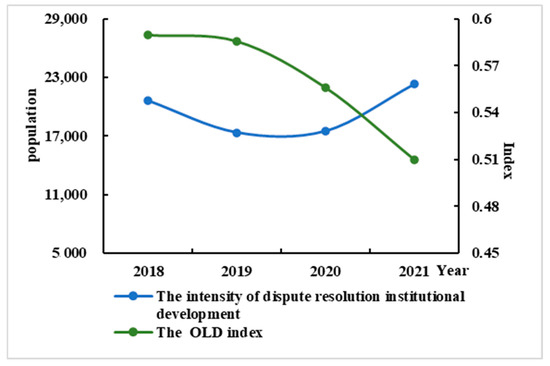

(1) Strengthening institutional development enhanced the capacity for resolving land disputes. The new institutionalism theory holds that institutions play a normative role. Through the reinforcement of institutional development, governments could improve their internal structures and operations to enhance governance efficacy and better fulfill their responsibilities [44]. In the operation of the land market, the governments could establish clearer and more comprehensive rules and procedures for dispute resolution in order to resolve or prevent land disputes by diversified approaches. It was helpful in the prompt and accurate coordination among relevant departments in resolving land disputes [45], resulting in the promotion of the governmental efficiency of land affairs governance and facilitating the fulfillment of its responsibilities in social governance. Entering the new era, General Secretary Xi Jinping has repeatedly emphasized the importance of adhering to and developing the “Fengqiao Experience”, providing guidance for the construction of the diversified prevention and resolution mechanism for land disputes for local governments in the YREB. This study adopted the number of arbitration committee members as the intensity measure of the dispute resolution institutional development, according to Tan and Zou (2022) [46]. As shown in Figure 9, the overall intensity of dispute resolution institutional development among provinces (or cities) in the YREB exhibited an upward trend. The results indicate that with the enhancement of the dispute resolution institutional development in the YREB, as well as the diversified mechanisms for the prevention and resolution of land dispute, the government’s capacity for resolving land disputes was enhanced.

Figure 9.

The intensity of dispute resolution institutional development and OLD index in the YREB from 2018 to 2021.

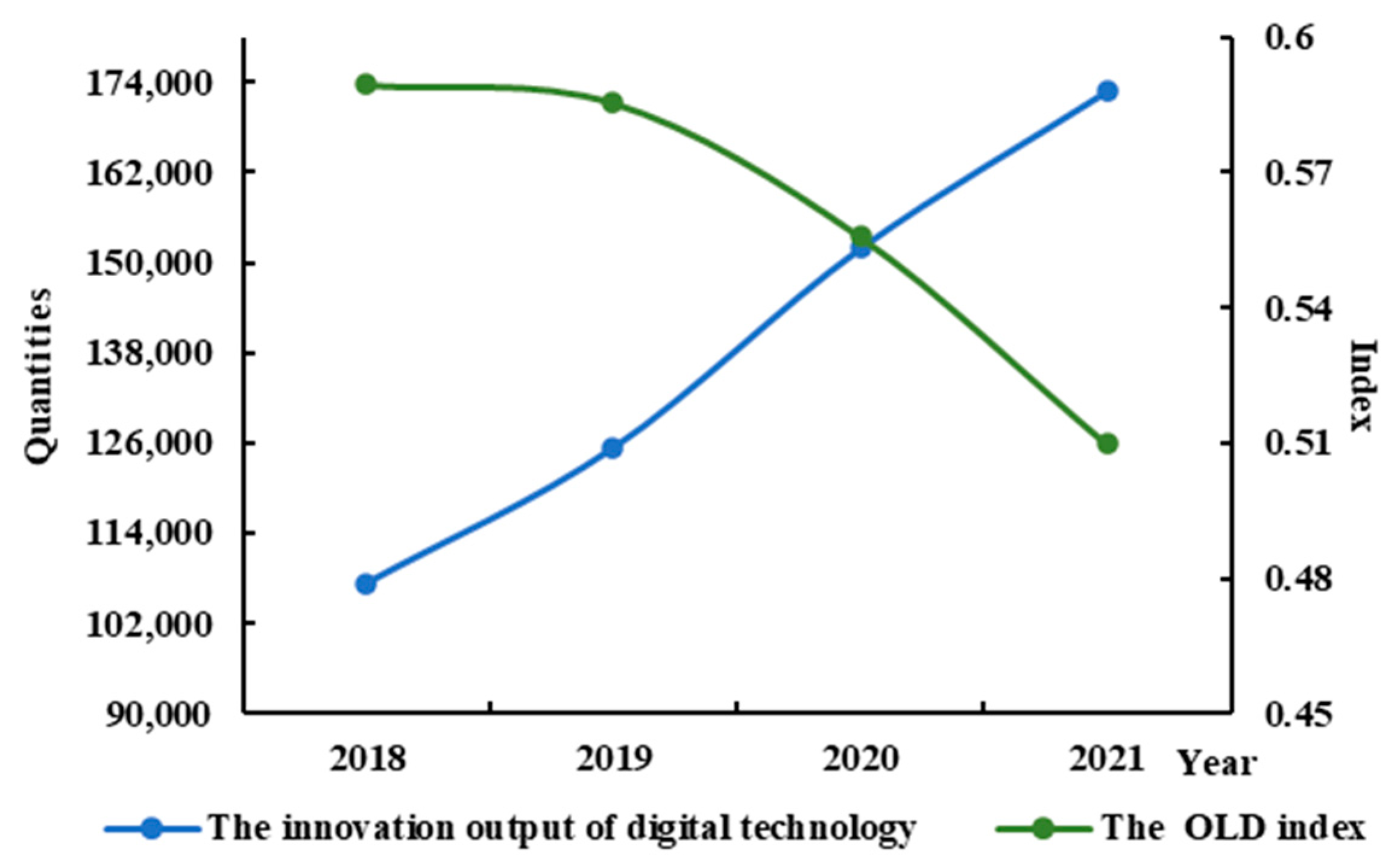

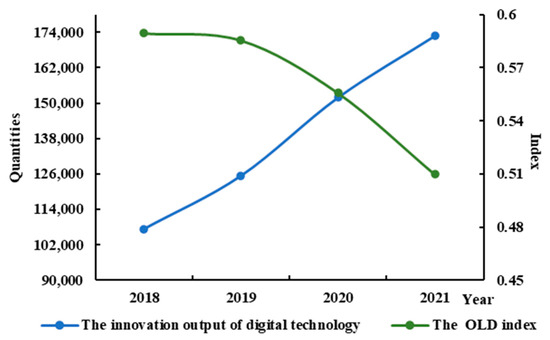

(2) Utilizing digital technology enhanced land dispute resolution capability. The theory of new public services posited that public service providers were supposed to continuously enhance the quality and efficiency of services using new technologies. The application of digital technology was believed to offer a more intelligent, efficient, and service-oriented governance approach, which contributed to the improvement of public service capabilities [43]. In contemporary society, governments serve as public service providers. By integrating digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and big data analytics into land management, governments could not only facilitate the efficient management and sharing of land information [47] but also provide intelligent decision support systems for resolving land disputes [48], which prompted the governmental capacities in land dispute resolution. Entering the new era, General Secretary Xi Jinping proposed that “We must utilize big data to enhance the modernization of national governance, and establish sound operations for big data-assisted scientific decision-making and social governance”. Various local governments in the YREB have acted on the national call. For instance, Xiaoshan District in Zhejiang Province has implemented a new digitalized grassroots social governance model. The Shanghai courts have embedded “digital court” applications into case handling systems to provide decision-making references for judicial trials. Additionally, Xuzhou in Jiangsu Province has embraced a new model of social governance, combining big data analytics and artificial intelligence applications. This paper adopted the annual counts of patent applications in high-tech industries as a metric for measuring the innovative output of digital technology. As in Figure 10, there was a significant increase in the innovation output of digital technology in the YREB during the periods when the land dispute index declined. The results indicated that the application of digital technology was beneficial in resolving conflicts and disputes, with land disputes serving as a representative example.

Figure 10.

The innovation output of digital technology and OLD index in the YREB from 2018 to 2021.

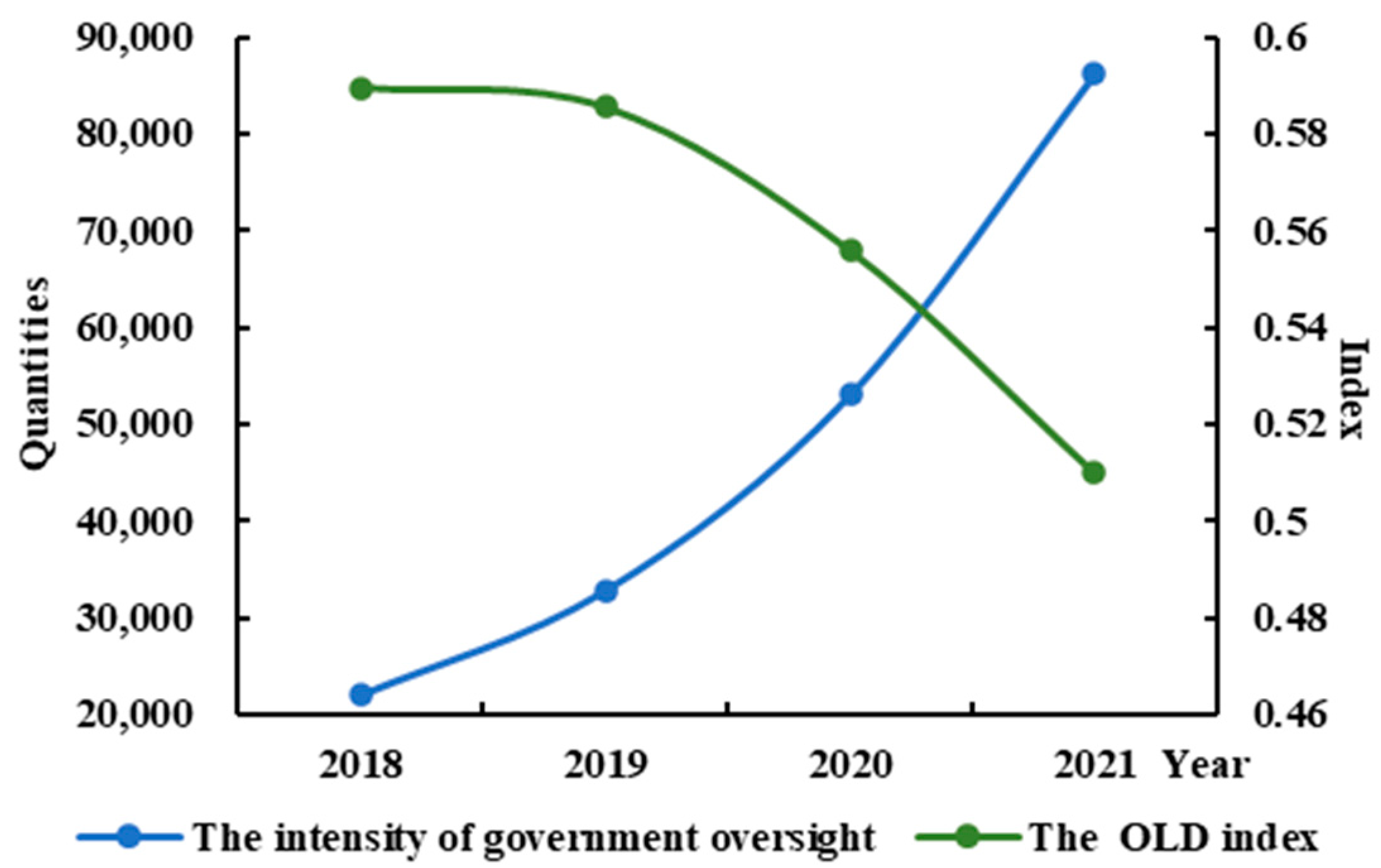

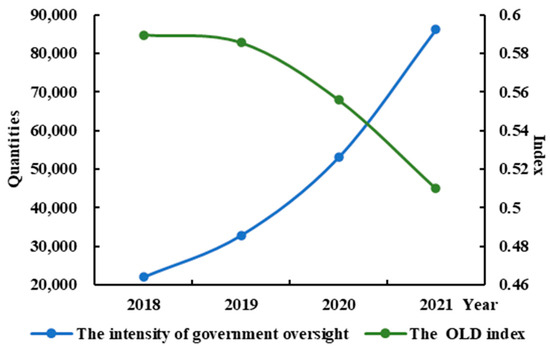

(3) Strengthening government oversight enhanced the land dispute resolution capability. According to the theory of agency, agents might not always act in accordance with the rule of maximizing the principal’s interests, which require government oversight or incentive operations to address agency problems [49]. In the governance of land disputes specifically, agents (the government) might not fully fulfill the expectations of the principal (the public) due to their own interests. In this case, government oversight could be considered an effective supervisory mechanism, which enables the public to effectively access, assess, and rectify the information asymmetries in government behaviors [50]. This was helpful in enhancing the government’s capability to resolve land disputes. Entering the new era, local governments in the YREB were continuously strengthening government oversight and vigorously combating land-related illegal activities in order to promote the modernization of the land dispute governance system and governance capabilities. In this study, the annual quantity of land violation disposals was used as a measure of the intensity of government oversight. As in Figure 11, the intensity of the government oversight in land management in the YREB was continuously strengthened during the periods when the land dispute index declined, resulting in a significant enhancement in land dispute resolution capability.

Figure 11.

The intensity of government oversight and OLD index in the YREB from 2018 to 2021.

3.2.3. The Focus of Land Disputes Moved to the West in the YREB

Previous studies indicated that the land disputes were severe in the developed coastal areas in the east during periods of rapid economic development in China [51]. However, the spatial analysis of land dispute index in the YREB from 2012 to 2021 highlighted a new characteristic of land disputes where the focus of land disputes in the YREB moved to the west. This new characteristic was attributed to the influence of national policies supporting the upstream regions of the YREB. These regions were entrusted with more significant tasks related to land ecological protection as the economic developed rapidly, which resulted in more conflicts when compromising the balance between economic development and land ecological conservation compared with other regions.

(1) Urgent requirements for the increased demand for land led to the focus of land disputes towards the west. According to the theory of supply and demand, land was one of the factors of production under market economy conditions, which was influenced by supply and demand dynamics [52]. When the increasing demand for land resources in the market exceeded its supply, land prices increased and competition for land and its associated benefits intensified accordingly [53]. In the new era, the center of the regional development in the YREB exhibited accelerated westward migration characteristics [54]. Economic development served as the primary driver of urban expansion. Local governments in the upstream regions of the YREB were eager to promote urban expansion to accelerate regional economic development. In this study, the annual area of the requisitioned collective land was used as a metric for land demand. As in Figure 12, the focus of the land demand in the YREB showed a trajectory of “northeast-southwest-northeast-southwest”. Overall, there was a westward trend, consistent with the OLD index. The results indicate that as urban expansion accelerated in the upstream regions of the YREB, the focus of land demand moved westward, leading to an increase in land disputes and a westward shift in the focus of land disputes.

Figure 12.

The migration trajectory of the focus of land demand in the Yangtze River Economic Belt from 2012 to 2021.

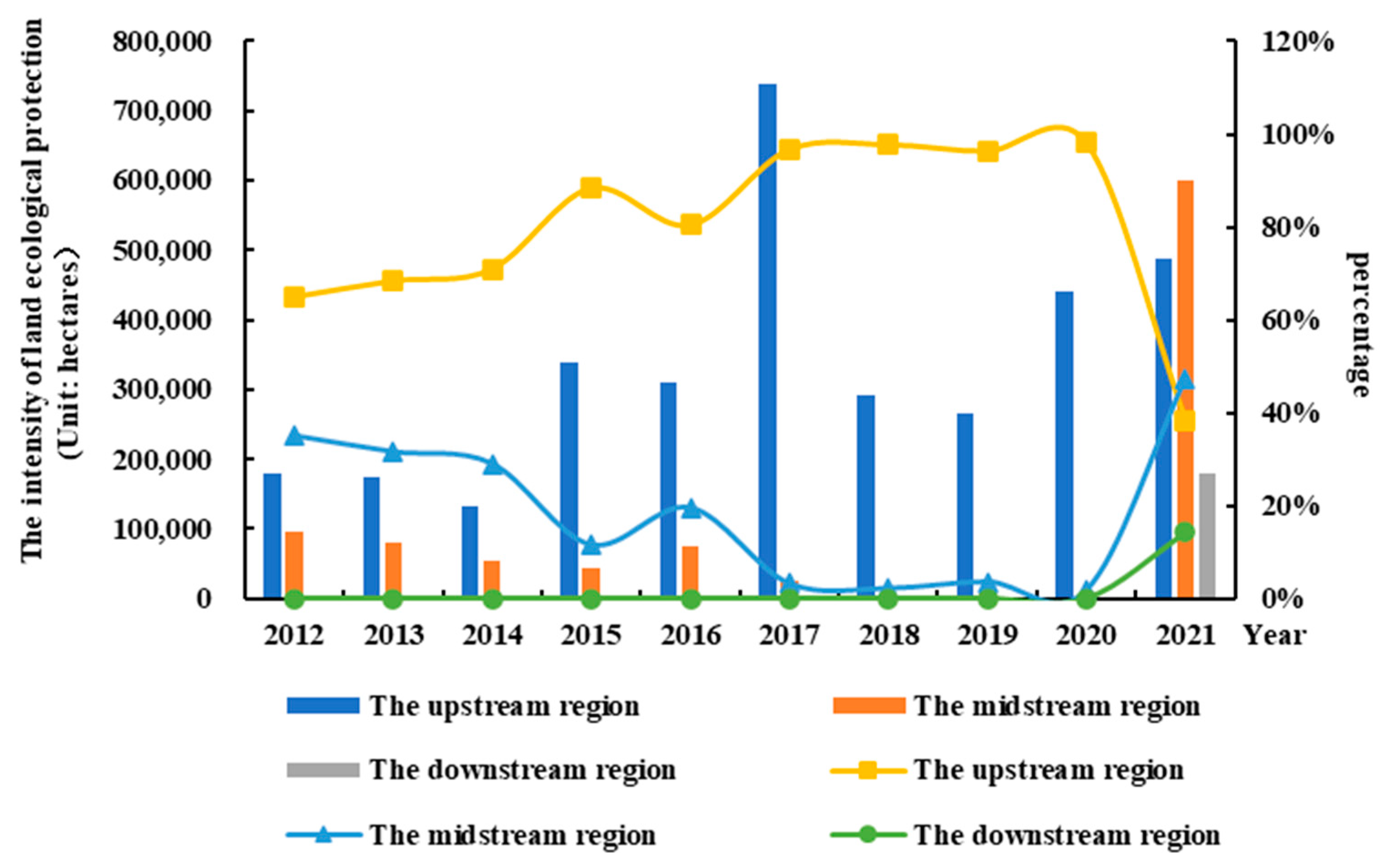

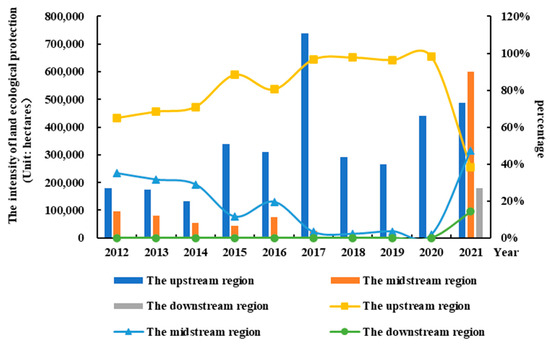

(2) Urgent requirements for land ecological protection caused the focus and disputes to move to the west. Spatial conflict theory suggested that spatial conflicts arise from the opposition and competition among stakeholders for resources (assets) [55] or from the overlapping of spatial utilization in an irrational manner [56]. The limited land space and the increasing diverse land demands led to conflicts. In the new era, General Secretary Xi Jinping emphasized the development principle of the YREB as “pursuing green development and rejecting large-scale unsustainable development”. Located in Western China, the upstream area of the YREB serves as a crucial ecological barrier zone for the Yangtze River basin and even the whole nation, where the restricted ecological area by the government is 804.3 km2, accounting for 67.7% of the total restricted ecological area of the YREB [57]. While promoting economic development, local governments in the upstream YREB have also strengthened the protection and restoration of land resources. In this study, the annual area of forestland converted from cropland in 2012–2021 was treated as a metric to measure the intensity of land ecological protection, and that of the upstream, midstream, and downstream areas of the YREB is calculated and presented in Figure 13. The intensity of land ecological protection in the upstream area of the YREB has consistently remained the highest in 2012–2020 with an average of 80%, followed by the midstream area at 18% and the downstream area at 1%. Consequently, with the implementation of measures such as restricting land use, restoring polluted land, and converting cropland to forest, more land space was required for land ecological protection, resulting in land utilization conflicts and a tendency of the focus of land disputes to move westward.

Figure 13.

The land ecological protection intensity and its proportion in the upstream, midstream, and downstream regions of the YREB from 2012 to 2021.

3.2.4. Regional Disparities in Land Disputes Have Declined

According to research conducted by the groups at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, the land dispute occurrence rates across different regions in China have shown significant disparities since 2005 [58]. However, the spatial evolution analysis of the OLD index in the YREB revealed a new characteristic: the regional disparity in land disputes has declined. This new characteristic was attributed to the regional disparity of both land disputes and the governance level being decreased as a result of reduced regional disparities in economic development and inputs into rural governance in the accelerated pace of integrated development in the YREB in the new era.

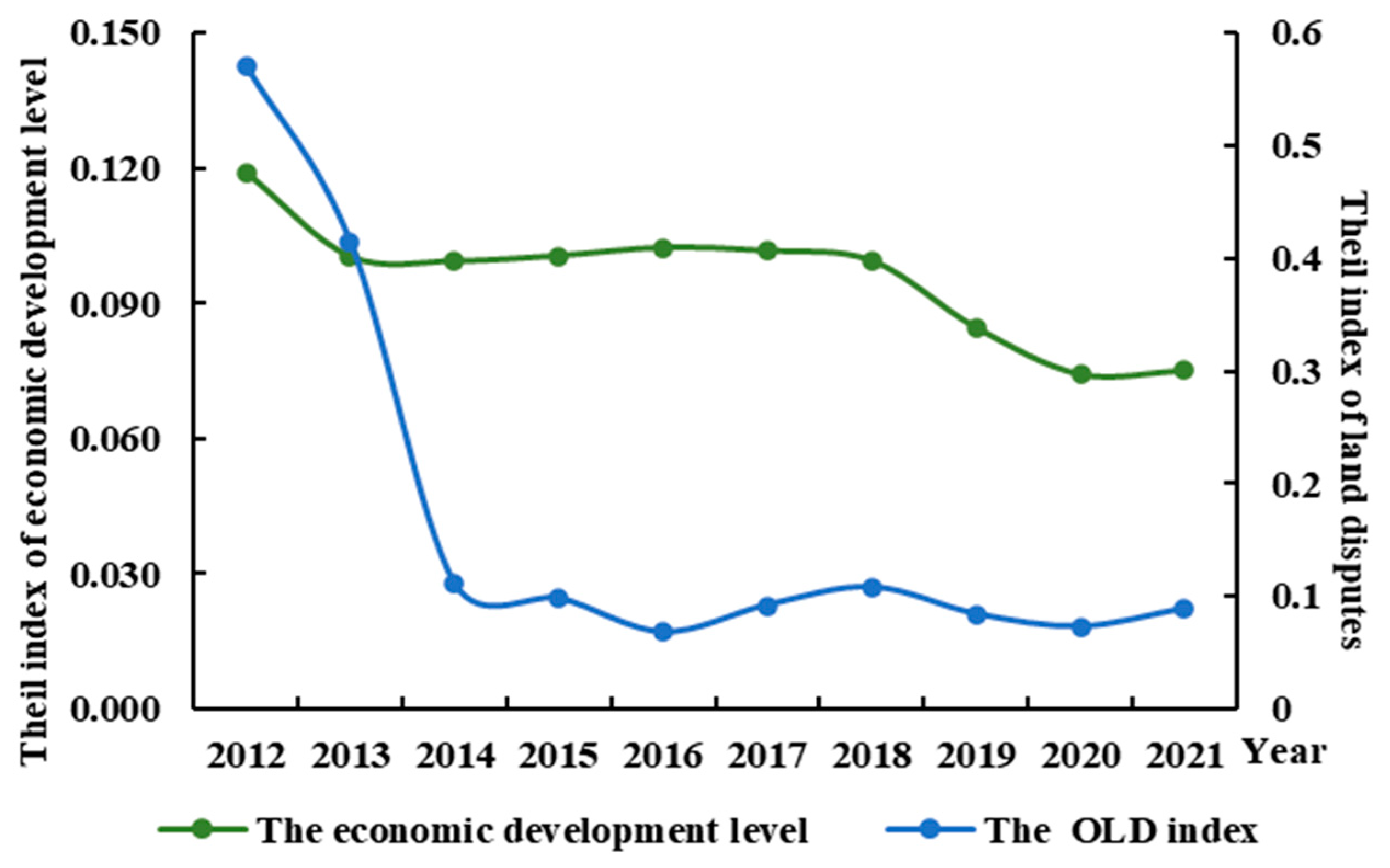

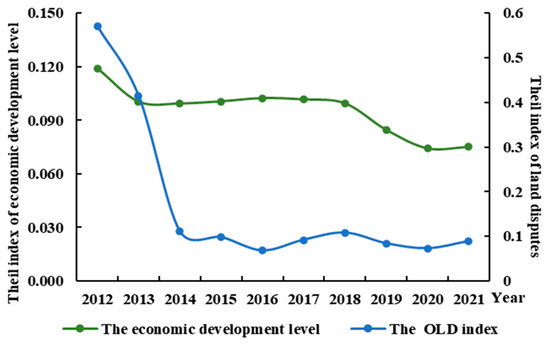

(1) The decline in the regional disparity of the economic development led to a decrease in the regional disparity of land disputes. The theory of growth poles posits that as the initial growth pole regions developed, their diffusion effects in economic activities, including technology diffusion, talent migration, and the expansion of industrial chains, would reduce regional development disparities [59]. Many research studies have revealed the significant correlation between economic growth and land disputes [60,61]. As economic activities in growth pole regions spread, the reduction in regional development disparities also led to a decrease in regional disparities in land disputes and their spread. A previous study indicated that the disparities in high-quality economic development in the YREB have been continuously diminishing and the imbalances within urban agglomerations gradually decreased, and the disparities in the development capabilities among cities decreased as well [62]. In this study, the per capita GDP was employed as a measure of economic development level, while its Theil index calculation was used for the measure of the internal economic development disparities within the YREB, both of which showed a declining trend from 2012 to 2021, as in Figure 14. The Theil index of the YREB decreased from 0.119 in 2012 to 0.075 in 2021. The results indicated that the internal economic development disparities within the YREB decreased consistently, aligning with the trend observed in the Theil index of OLD index. Thus, the decline in the regional disparity of the economic development led to a decrease in the regional disparity of land disputes.

Figure 14.

The Theil index of economic development level and land disputes within the YREB from 2012 to 2021.

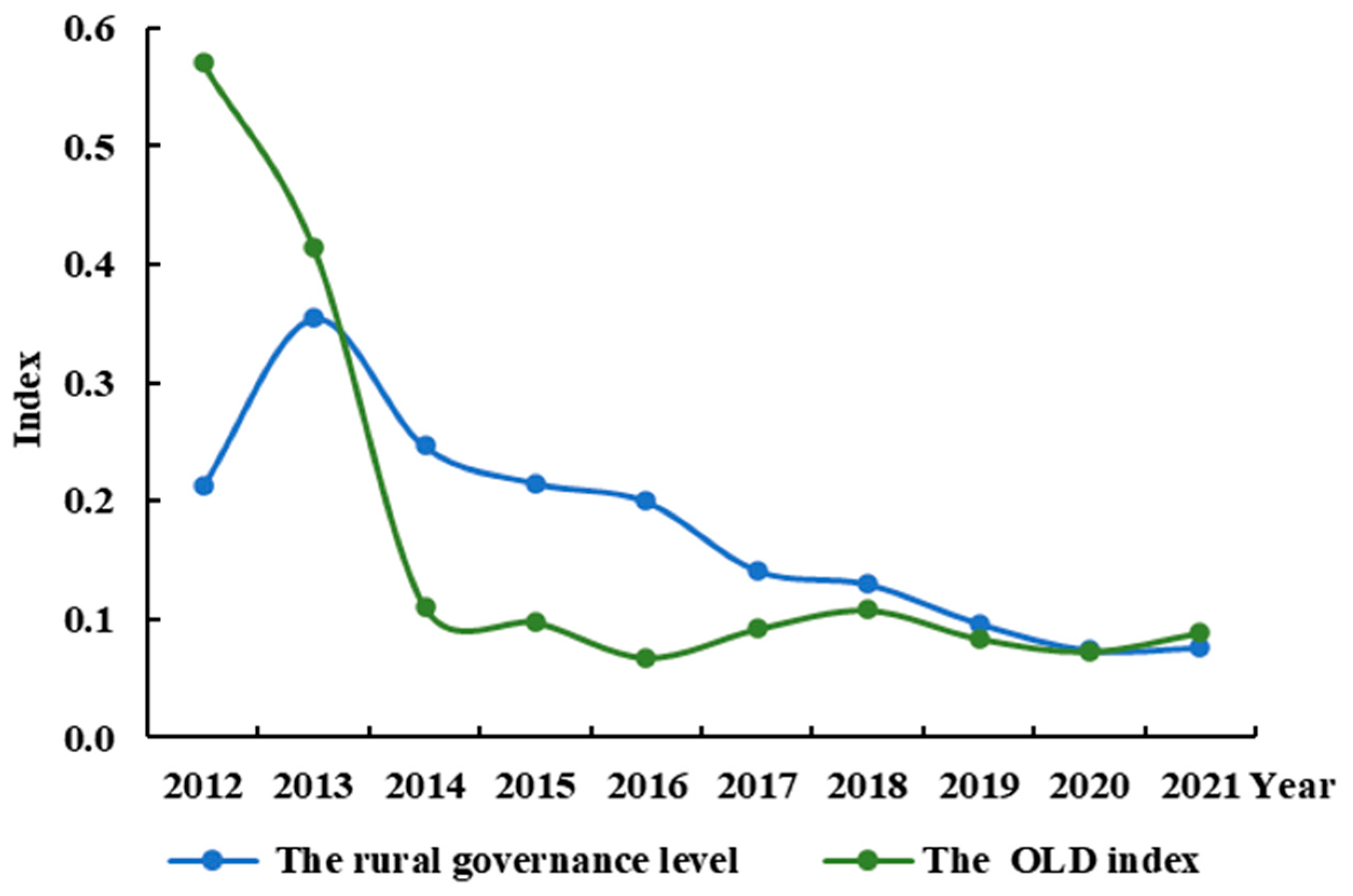

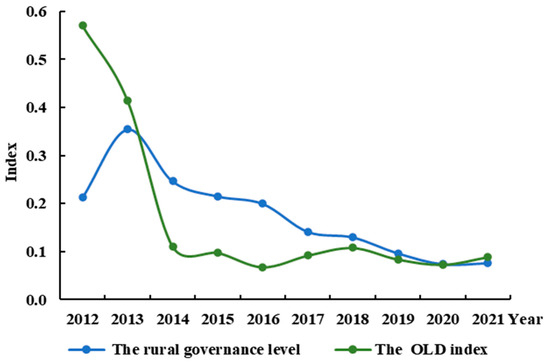

(2) The decline in the regional disparity of the rural governance level led to a decrease in the regional disparity of land disputes. The theory of public governance suggests that improving the government public services could promote the governance capacity and reduce the uncertainty and probability of conflicts [63]. Previous studies have stated that the modernization level of rural governance in East China was higher than that in West China. However, the regional disparities in governance level have been gradually diminishing [64], which consequently led to a reduction in the regional disparity of land conflicts. In the new era, local governments in the YREB are continuously enhancing governance capacity, especially rural governance capacity. This study adopted the success rate of dispute mediation in the rural governance capacity evaluation index, proposed by Gao et al. (2024) [65], as a quantitative indicator of the rural governance level. The Theil index of the rural governance level within the YREB from 2012 to 2021 is calculated and shown in Figure 15, as well as the Theil index of land disputes. The Theil index of rural governance level within the YREB decreased from 0.212 in 2012 to 0.076 in 2021, showing a downward trend on the whole, which was consistent with the trend in the Theil index of the OLD index. Thus, the decline in the regional disparity of the rural governance level led to a decrease in the regional disparity of land disputes.

Figure 15.

The Theil index of the rural governance level and land disputes in the YREB from 2012 to 2021.

4. Discussion

This study aims to provide a tool for characterizing and analyzing land disputes in the YREB in China, which is beneficial for contemporary public governance and for achieving a high-quality development of the YREB. Some meaningful and new achievements have been acquired. For example, this study found that the number of land acquisition conflicts in the YREB first increased and then decreased over time, which was similar to the result in previous studies [15,46]. Meanwhile, a previous study also revealed that the number of land disputes in western regions surpassed that in eastern regions [16], which also corroborated the observation that the focus of land disputes has shifted westward in this study, as evidenced in our research from one aspect. However, this study also indicated that these disparities declined over time, although there were significant regional disparities in current land disputes. This positive progress indicated an overall improvement in land disputes in the YREB. Furthermore, an evaluation index system of the new characteristics of land disputes, named the overall land dispute (OLD) index, was constructed according to measurement theory by coupling the interactions of quantity, claim amounts, duration periods, and the appeal rate of land disputes. The OLD index was evaluated by descriptive statistical methods, a GIS spatial analysis, a center of gravity model, kernel density estimation, and Theil index methods. Then, the new characteristics of the land disputes in the YREB were acquired through quantitative analysis.

Faced with land disputes accompanying economic growth in the new era, government intervention played an important role in land dispute resolution [66]. A set of land dispute resolution mechanisms including legislation, propaganda, negotiations, mediation, litigation, arbitration, administrative reconsideration, and petitions have been established [44,45]. These mechanisms have led to the emergence of new characteristics in the YREB, such as the alleviation of land disputes and the enhancement of dispute resolution capabilities, indicating that the overall situation regarding land disputes in the YREB shows improvement. However, due to the increasing cross-border, interconnected, and complex nature of land dispute issues [67], the absolute level of land disputes in the YREB remains relatively high, and the focus of land disputes has shifted westward. Thus, some policy implications are recommended in the prevention and resolution of land disputes, as follows:

(1) The land disputes remain at a high level in both complexity and quantity, which requires the government to construct a multi-level and multi-faceted dispute resolution mechanism, not just solve cases using the judicial system. Considering that the judicial system was overwhelmed by a high volume of cases and small-scale disputes [68], the optimized dispute resolution system should offer multiple remedies for the parties, fully utilize various dispute resolution methods, and strive to resolve disputes quickly and properly.

(2) The government should pay attention to the shifting focus of land disputes towards the west in recent years. The western region of the YREB was at a relatively low economic development level, where the government heavily relied on land-based fiscal income due to a lack of diversified revenue sources, and it had also been assigned a crucial role in national ecological protection [69]. The local governments are suggested to vigorously support the development of innovative economies in this region and reduce reliance on land finance. At the same time, the land protection and governance should be strengthened to promote the sustainable development of land resources and reduce the possibility of potential land disputes as well.

(3) Currently, as a positive tendency, the regional disparities in land disputes are declining. The establishment of a unified information sharing platform is essential for further decreasing the regional disparities [70]. In this case, the platform not only enables the effective sharing of resources relevant to land dispute governance but also facilitates the expeditious resolution of inter-provincial and inter-municipal land dispute cases. It is instrumental in proactively preventing and mitigating the adverse consequences that may arise from land disputes.

(4) The overall capacity for resolving land disputes has been constantly improved. Nowadays, artificial intelligence and big data provide new tools for local governments in the YREB to monitor and manage the land dispute information [71]. It would facilitate the integration and management of collected land dispute information, enabling real-time updates and queries. And the assisted decision-making system using AI and big data would be recommended for highlighting and solving the higher levels of dispute and prominent issues noted by public feedback.

It should be noted that more details, such as the number of individuals involved in the disputes, the area of disputed land, whether legal representation was sought, or whether the disputes constituted collective events, were difficult to extract from court judgments, which were omitted by the current technologies. Furthermore, future research should focus on enhancing the evaluation system of land disputes comprehensively by coupling augmented discussions on relevant land dispute cases in representative regions.

5. Conclusions

A better understanding of the manifestation and formation mechanism of new characteristics of land disputes is beneficial for contemporary public governance and for achieving a high-quality development of the YREB. A total of 325,105 land dispute cases in 11 provinces or municipalities of the YREB from 2012 to 2021 were collected and analyzed. On this basis, an evaluation index system of the new characteristics of land disputes, named the overall land dispute (OLD) index, was constructed according to measurement theory by coupling the interactions of quantity, claim amounts, duration periods, and the appeal rate of land disputes. Then, the OLD index was evaluated by descriptive statistical methods, a GIS spatial analysis, a center of gravity model, a kernel density estimation, and Theil index methods, to reveal the new characteristics and formation mechanisms of land disputes in the YREB from 2012 to 2021. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

(1) Land disputes have been alleviated, as evidenced by the trends of the OLD, DRLR, DLO, and DLC indices, all of which initially increased but have subsequently declined in the new era. However, the OLD index remained above 0.510, indicating a relatively high level, with conflicts stemming from DLCs appearing to be more severe compared with other types of disputes. The alleviation of land disputes in the YREB could be attributed to the collective effects of the region transitioning into a phase of high-quality development, characterized by the continuous optimization of land utilization structure, gradual improvement of land utilization systems, and the ongoing enhancement of public legal awareness.

(2) The capacity for resolving land disputes has been enhanced. The OLD index exhibited a significant decline, decreasing from 0.59 in 2018 to 0.51 in 2021, reflecting a notable promotion in the government’s land dispute resolution capabilities. This promotion was attributed to the continuous improvement of governmental working mechanisms, the gradual integration of digital technologies into governance, and the steady enhancement of governmental regulatory standards.

(3) The focus of land disputes moved to the west in the YREB. Based on the analysis of the spatial evolution of the OLD index from 2012 to 2021, the focus of the index in the YREB exhibited a significant westward shift along with a slight southward tendency. Urgent requirements for land ecological protection led to more severe conflicts between economic development and land ecological preservation compared with other regions due to the national policy support for the upstream regions of the YREB.

(4) Regional disparities in land disputes have declined. According to the kernel density estimation of the OLD index, the overall rise in the peak of the kernel density curve indicated the new characteristic of reduced regional disparities in land disputes within the YREB. This characteristic was attributed to the reduction in regional disparities in both land disputes and governance levels. The reduction was a result of the decreased regional disparities in economic development and investments in rural governance, driven by the accelerated pace of integrated development in the YREB in the new era.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z. and S.T.; methodology, Y.Z.; validation, S.Z. and S.T.; formal analysis, S.Z.; investigation, Q.H.; resources, M.Z.; data curation, S.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, S.T.; visualization, S.Z.; supervision, S.T.; project administration, S.T.; funding acquisition, S.T.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (Grant Number 20BZZ099).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gong, X. Non-traditional security cooperation between China and south-east Asia: Implications for Indo-Pacific geopolitics. Int. Aff. 2020, 96, 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L. The Politics of Harmony: Land Dispute Strategies in Swaziland; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wen, T. The Economic Fluctuations, the Change in Taxation Institution, and the Capitalization of Land Resources: A Case Study on the Problems with “The Three Times of Enclosing Land” since China’s Reform. Manag. World 2010, 4, 32–41+187. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Wang, J.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. High-quality development in China: Measurement system, spatial pattern, and improvement paths. Habitat Int. 2021, 118, 102458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Chen, L.; Tian, Y. Study on the urban state carrying capacity for unbalanced sustainable development regions: Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 89, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platteau, J. The evolutionary theory of land rights as applied to sub-Saharan Africa: A critical assessment. Dev. Change 1996, 27, 29–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.; Gichohi, H.; Mwangi, A.; Chege, L. Land use conflict in Kajiado district, Kenya. Land Use Policy 2000, 17, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alston, L.; Libecap, G.; Mueller, B. Land reform policies, the sources of violent conflict, and implications for deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2000, 39, 162–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrmann, B. Land Conflicts: A Practical Guide to Dealing with Land Disputes; GTZ: Eschborn, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X. Power and Justice: Dispute Resolution and Pluralistic Authority in Rural Society; Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House: Tianjin, China, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. Types, causes and solutions of rural land disputes. Academics 2008, 1, 171–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kansanga, M.; Arku, G.; Luginaah, I. Powers of exclusion and counter-exclusion: The political ecology of ethno-territorial customary land boundary conflicts in Ghana. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugizi, F.M.; Matsumoto, T. From conflict to conflicts: War-induced displacement, land conflicts, and agricultural productivity in post-war Northern Uganda. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, A.E.; Drabik, D.; Dries, L.; Heijman, W. Large-scale land investments and land-use conflicts in the agro-pastoral areas of Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Tan, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Wei, C.; Li, Y. Conflicts of land expropriation in China during 2006–2016: An overview and its spatio-temporal characteristics. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Tong, B.; Zhang, J. How Did the Land Contract Disputes Evolve? Evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land 2023, 12, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkia, M.; Ferri, S.; Schellens, M.; Papazoglou, M.; Thomakos, D. The Global Conflict Risk Index: A quantitative tool for policy support on conflict prevention. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Cao, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, X.; Yang, R.; Gong, P. Future global conflict risk hotspots between biodiversity conservation and food security: 10 countries and 7 Biodiversity Hotspots. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 34, e02036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, C. Development of a risk culture intensity index to evaluate the financial market in Germany. In Proceedings of the FIKUSZ’14 Symposium for Young Researcher, Budapest, Hungary, 2014; pp. 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Burnley, C.; Buda, D.; Kayitakire, F. Quantifying the Risk of Armed Conflict at Country Level—A Way Forward. In Proceedings of the 3 Treaty Monitoring Based on Geographic Information Systems and Remote Sensing, Bonn, Germany, 2008; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, G.; Zhao, Y. Ecology versus economic development: Effects of China’s Yangtze River Economic Belt strategy. Int. Stud. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, M.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, C. Fostering inclusive green growth in China: Identifying the impact of the regional integration strategy of Yangtze River Economic Belt. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ting, H.; Liangen, Z.; Yan, Z.; Chuanying, Z.; Jing, L. Water quality comprehensive index method of Eltrix River in Xin Jiang Province using SPSS. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2012, 5, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutadian, A.; Muttil, N.; Yilmaz, A.; Perera, B. Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process to identify parameter weights for developing a water quality index. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 75, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. Analysis of the distribution and evolution of energy supply and demand centers of gravity in China. Energy Policy 2012, 49, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Ao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wan, Q.; Liu, X. Spatiotemporal variations of cultivated land use efficiency in the Yangtze River Economic Belt based on carbon emission constraints. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Song, C.; Chan, C.-S.; Pei, T.; Wenting, Y.; Xin, Z. Spatial-temporal distribution characteristics and evolution mechanism of urban parks in Beijing, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 64, 127265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, J.; Calvo, B.; Perez, A. Supervised non-parametric discretization based on Kernel density estimation. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2019, 128, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Hu, B.; Kuang, B.; Zhou, M. Regional differences and dynamic evolution of urban land green use efficiency within the Yangtze River Delta, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, J. Globalization—Entropy unification through the Theil index. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2008, 387, 6595–6604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.; Lauk, C.; Kastner, T.; Erb, K.; Haberl, H. Global inequalities in food consumption, cropland demand, and land-use efficiency: A decomposition analysis. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 64, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Ao, Y.; Peng, P.; Bahmani, H.; Han, L.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Q. Resource allocation of rural institutional elderly care in China’s new era: Spatial-temporal differences and adaptation development. Public Health 2023, 223, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, M. From “Land Conflict” to “Land Risks”: Theoretical Prospect on Land Issues in Rural China. China Land Sci. 2012, 26, 23–28+35. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J. The land issue has become the focus of the peasants’ struggle to protect their rights—A special research on the current social situation in rural China. World Surv. Res. 2005, 03, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bridges, S.; Harrison, J.K. Employee perceptions of stakeholder focus and commitment to the organization. J. Manag. Issues 2003, 15, 498–509. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, W.; Wang, T. Logical Problems on the Evaluation of Resources and Environment Carrying Capacity for Territorial Spatial Planning. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Qiao, Y.; Zhou, Q. Analysis of China’s industrial green development efficiency and driving factors: Research based on MGWR. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Tu, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, K.; Mei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, M. Spatio-temporal pattern for the coordination degree between industrial structure and land use efficiency of Yangtze River Economic Zone. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 235–246. [Google Scholar]

- North, D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Tan, S.; Peng, K. Analysis on the defects of land laws and regulations that induce rural land conflicts. Reform Econ. Syst. 2007, 01, 90–95. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C. The Reform of China’s Rural Land System. Issues in Agricultural Economy 2019, 1, 001. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, S.; Factor, R. Max Weber: The Lawyer as Social Thinker; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Silbey, S. After legal consciousness. Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2005, 1, 323–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immergut, E. The theoretical core of the new institutionalism. Politics Soc. 1998, 26, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, B.; Li, S. Governance Mechanism on Land-expropriation Conflicts in the Minorities Areas of Western China. China Land Sci. 2013, 36, 008. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Zou, S. Study on the Evolution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Land Disputes in the Yangtze River Economic Belt. China Land Sci. 2022, 36, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ai, G.; Yuan, Z. Research on the Development of China Land Information Science from 1980 to 2017. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, C. Big Data Empowering the Governance of Multiple Contradictions and Disputes in China’s New Era: Practice-Driven, Problem Challenges and Mechanism Optimization. Chin. Public Adm. 2023, 3, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, R.; Cuevas-Rodríguez, G.; Gomez-Mejia, L. Towards a social theory of agency. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J. The Role of the Judiciary in Implementing an Agency Theory of Government. NYUL Rev. 1989, 64, 1239. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, D. Analysis of Rural Land Conflicts in China during the Period of Social Transformation: Status, Types, and Trends. Southeast Acad. Res. 2008, 6, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, B. Land Use Regulation: A Supply and Demand Analysis of Changing Property Rights. J. Libert. Stud. 1981, 5, 435–451. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.; Yan, J.; Chen, H. Risk Management Research on Rural Homestead Transfer Based on Supply and Demand Theory. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2017, 5, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, H. County-Level Land Use Carbon Budget in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China: Spatiotemporal Differentiation and Coordination Zoning. Land 2024, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Lin, Z.; Lim, S. Spatial characteristics and risk factor identification for land use spatial conflicts in a rapid urbanization region in China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, A. Identification of land use conflicts and dynamic response analysis of Natural-Social factors in rapidly urbanizing areas−a case study of urban agglomeration in the middle reaches of Yangtze River. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 112009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Duan, Y.; Jiang, P.; Li, M. Spatial zoning to enhance ecosystem service co-benefits for sustainable land-use management in the Yangtze River economic Belt, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNRC. Why do rural land disputes occur frequently? Land Resour. 2016, 09, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y.; Lin, L. Border effect on migrants’ settlement pattern: Evidence from China. Habitat Int. 2023, 136, 102813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, B.; Lengoiboni, M.; Zevenbergen, J.; Simane, B. Rethinking the Impact of Land Certification on Tenure Security, Land Disputes, Land Management, and Agricultural Production: Insights from South Wello, Ethiopia. Land 2023, 12, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Jin, X.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, H. Spatiotemporal patterns and mechanisms of land-use conflicts affecting high-quality development in China. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 155, 102972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, N. Differences in High-Quality Development and Its Influencing Factors between Yellow River Basin and Yangtze River Economic Belt. Land 2023, 12, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazmand, A. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, X.; Pang, Z. Measurement and Spatial Convergence of Chinese Modernization of Rural Governance. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2023, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, B. Research on China Rural Governance Evaluation and Its Influence Mechanism. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2024, 3, 94–113. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, M. Contesting land rights in a post-conflict environment: Tenure reform and dispute resolution in the centre-West region of Côte d’Ivoire. Land Use Policy 2016, 54, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A. Challenges and Opportunities of Chinese International Arbitral Institutions and Courts in a New Era of Cross-Border Dispute Resolution. BU Int’l LJ 2020, 38, 352. [Google Scholar]

- He, X. Pressures on Chinese judges under Xi. China J. 2021, 85, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Guan, D.; He, X.; Yin, B.; Zhou, L.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y. Quantification of the coupling relationship between ecological compensation and ecosystem services in the Yangtze River Economic Belt, China. Land Use Policy 2022, 114, 105995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Ren, F.; Wan, F. Sharing benefits? The disparate impact of home-sharing platform on industrial and social development. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2022, 53, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Dhunny, Z. On big data, artificial intelligence and smart cities. Cities 2019, 89, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).