Value of Ultrasound Super-Resolution Imaging for the Assessment of Renal Microcirculation in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

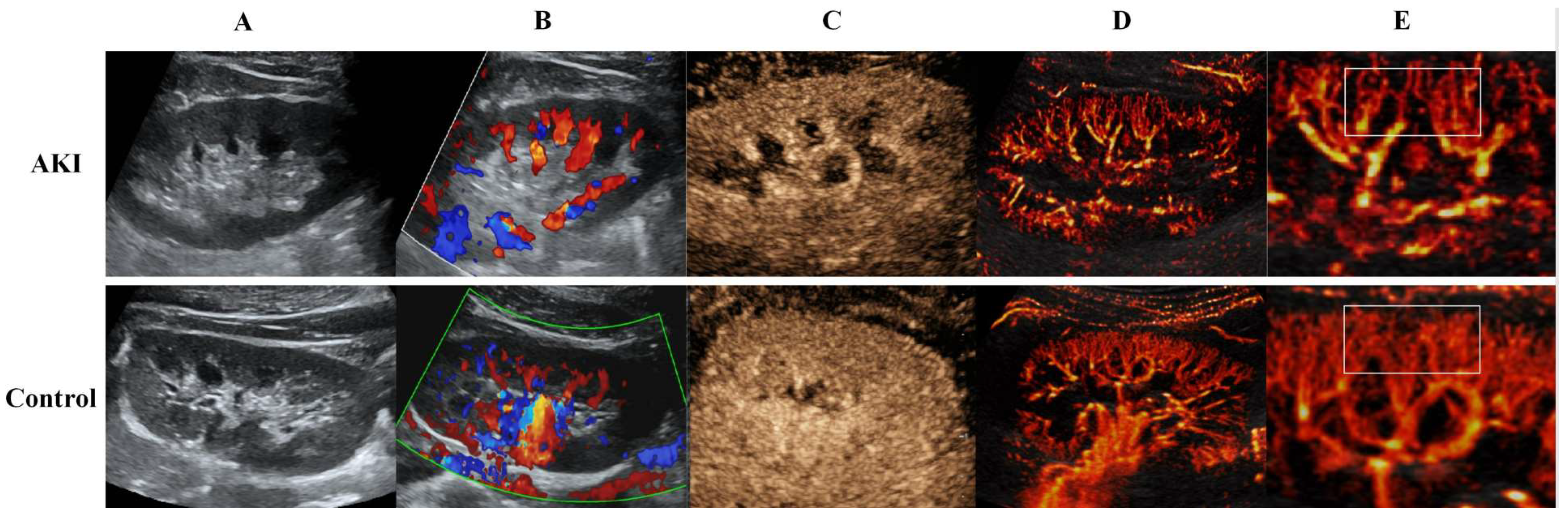

2.2. US Image Acquisition

2.3. CEUS Image Acquisition

2.4. US SRI Acquisition

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. US and CEUS Parameters

3.3. US SRI Parameters

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Basile, D.P.; Bonventre, J.V.; Mehta, R.; Nangaku, M.; Unwin, R.; Rosner, M.H.; Kellum, J.A.; Ronco, C.; ADQI XIII Work Group. Progression after AKI: Understanding Maladaptive Repair Processes to Predict and Identify Therapeutic Treatments. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, M.T.; Bhatt, M.; Pannu, N.; Tonelli, M. Long-term outcomes of acute kidney injury and strategies for improved care. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, E.J.; Jayasinghe, K.; Glassford, N.; Bailey, M.; Johnson, D.W.; Polkinghorne, K.R.; Toussaint, N.D.; Bellomo, R. Long-term risk of adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies using consensus definitions of exposure. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basile, D.; Yoder, M. Renal Endothelial Dysfunction in Acute Kidney Ischemia Reperfusion Injury. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Disord. Targets 2014, 14, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.E.; Kim, D.W.; Kim, D.; Kim, Y.; Shin, S.J.; Shin, Y.R. A pilot trial to evaluate the clinical usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in predicting renal outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Søgaard, S.B.; Andersen, S.B.; Taghavi, I.; Schou, M.; Christoffersen, C.; Jacobsen, J.C.B.; Kjer, H.M.; Gundlach, C.; McDermott, A.; Jensen, J.A.; et al. Super-Resolution Ultrasound Imaging of Renal Vascular Alterations in Zucker Diabetic Fatty Rats during the Development of Diabetic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis, L.; Bodard, S.; Hingot, V.; Chavignon, A.; Battaglia, J.; Renault, G.; Lager, F.; Aissani, A.; Hélénon, O.; Correas, J.-M.; et al. Sensing ultrasound localization microscopy for the visualization of glomeruli in living rats and humans. EBioMedicine 2023, 91, 104578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Annane, D.; Bauer, M.; Bellomo, R.; Bernard, G.R.; Chiche, J.-D.; Coopersmith, C.M.; et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levey, A.S.; Eckardt, K.-U.; Dorman, N.M.; Christiansen, S.L.; Hoorn, E.J.; Ingelfinger, J.R.; Inker, L.A.; Levin, A.; Mehrotra, R.; Palevsky, P.M.; et al. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: Report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int. 2020, 97, 1117–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, X.; Wen, Y.; Du, B.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Yin, Y.; Zhu, B.; Xi, X.; et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in intensive care units in Beijing: The multi-center BAKIT study. BMC Nephrol. 2019, 20, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peerapornratana, S.; Manrique-Caballero, C.L.; Gómez, H.; Kellum, J.A. Acute kidney injury from sepsis: Current concepts, epidemiology, pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Su, T. Evaluating renal microcirculation in patients with acute kidney injury by contrast-enhanced ultrasonography: A protocol for an observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2022, 23, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Yu, J.; Lei, Y.-M.; Hu, J.-R.; Hu, H.-M.; Harput, S.; Guo, Z.-Z.; Cui, X.-W.; Ye, H.-R. Ultrasound super-resolution imaging for the differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules: A pilot study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 978164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Lei, Y.-M.; Li, N.; Yu, J.; Jiang, X.-Y.; Yu, M.-H.; Hu, H.-M.; Zeng, S.-E.; Cui, X.-W.; Ye, H.-R. Ultrasound super-resolution imaging for differential diagnosis of breast masses. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1049991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Yu, J.; Rush, B.M.; Stocker, S.D.; Tan, R.J.; Kim, K. Ultrasound super-resolution imaging provides a noninvasive assessment of renal microvasculature changes during mouse acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2020, 98, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.-M.; Lowerison, M.R.; Song, P.-F.; Zhang, W. A Review of Clinical Applications for Super-resolution Ultrasound Localization Microscopy. Curr. Med Sci. 2022, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, L.; Yang, Y.; Qiu, L.; He, Q.; Liu, J.; Qian, L.; Luo, J. Evaluation of Early Diabetic Kidney Disease Using Ultrasound Localization Microscopy: A Feasibility Study. J. Ultrasound Med. 2023, 42, 2277–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Yan, J.; Morris, M.; Sinnett, V.; Somaiah, N.; Tang, M.-X. Acceleration-Based Kalman Tracking for Super-Resolution Ultrasound Imaging In Vivo. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2023, 70, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon, J.N.; Khaing, Z.Z.; Hyde, J.E.; Hofstetter, C.P.; Tremblay-Darveau, C.; Bruce, M.F. Quantitative tissue perfusion imaging using nonlinear ultrasound localization microscopy. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, E.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Dziedziejko, V.; Tomasiewicz, I.; Domański, L. Renal Microcirculation Injury as the Main Cause of Ischemic Acute Kidney Injury Development. Biology 2023, 12, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AKI Group | Control Group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 38 | n = 24 | ||

| Male gender, n (%) | 17 (44.7%) | 11 (45.8%) | 0.892 |

| Age, years, mean ± S.E. | 62.4 ± 11.7 | 61.8 ± 12.1 | 0.864 |

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 23 (60.5%) | 14 (58.3%) | 0.748 |

| Coronary heart disease | 9 (23.7%) | 6 (25.0%) | 0.815 |

| Diabetes | 14 (36.8%) | 8 (33.3%) | 0.795 |

| Cerebral apoplexy | 6 (15.8%) | 3 (12.5%) | 0.563 |

| Use of vasoactive drugs | 14 (36.8%) | 4 (16.7%) | 0.073 |

| Heart function | |||

| Heart rate (BPM) | 113.2 ± 16.5 | 86.2 ± 13.4 | <0.001 |

| Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 126.7 ± 21.0 | 121.5 ± 19.8 | 0.593 |

| Diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 77.4 ± 15.3 | 79.3 ± 14.2 | 0.772 |

| Left ventricular systolic function (%) | 64.2 ± 6.1 | 66.3 ± 5.7 | 0.648 |

| Renal function | |||

| Scr (μmol/L) | 152.7 ± 44.1 | 81.5 ± 19.1 | <0.001 |

| BUN (μmol/L) | 13.4 (9.5, 18.4) | 5.3 (4.8, 6.9) | <0.001 |

| Urine volume of 24 h (mL) | 347 (271, 649) | 1463 (1283, 1895) | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 59.3 ± 14.7 | 87.2 ± 4.8 | <0.001 |

| AKI Group | Control Group | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 38 | n = 24 | ||

| 2D-US parameters | |||

| Renal size (mm) | 114.6 ± 12.4 | 113.7 ± 13.6 | 0.712 |

| Renal parenchyma thickness (mm) | 14.6 ± 1.9 | 14.3 ± 2.1 | 0.518 |

| Renal cortical thickness (mm) | 8.2 ± 1.2 | 7.9 ± 1.1 | 0.273 |

| Renal blood perfusion | |||

| Grade 2, n (%) | 4 (10.5) | 2 (8.3) | 0.832 |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 34 (89.5) | 22 (91.7) | |

| RI of the interlobar artery | 0.69 ± 0.09 | 0.61 ± 0.08 | 0.003 |

| CEUS parameters | |||

| TTP (s) | 47.1 ± 9.9 | 35.54 ± 5.48 | <0.001 |

| MTT (s) | 80.3 ± 12.4 | 54.2 ± 9.1 | <0.001 |

| PI (dB) | 33.9 ± 5.5 | 43.1 ± 4.6 | <0.001 |

| AUC (dB) | 3198.9 ± 778.5 | 4348.5 ± 539.8 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Deng, Q. Value of Ultrasound Super-Resolution Imaging for the Assessment of Renal Microcirculation in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Preliminary Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111192

Huang X, Zhang Y, Zhou Q, Deng Q. Value of Ultrasound Super-Resolution Imaging for the Assessment of Renal Microcirculation in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Preliminary Study. Diagnostics. 2024; 14(11):1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111192

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Xin, Yao Zhang, Qing Zhou, and Qing Deng. 2024. "Value of Ultrasound Super-Resolution Imaging for the Assessment of Renal Microcirculation in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Preliminary Study" Diagnostics 14, no. 11: 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111192

APA StyleHuang, X., Zhang, Y., Zhou, Q., & Deng, Q. (2024). Value of Ultrasound Super-Resolution Imaging for the Assessment of Renal Microcirculation in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Preliminary Study. Diagnostics, 14(11), 1192. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics14111192