Abstract

The protection and utilization of architectural heritage requires the synergistic cooperation of multiple interest groups. Tourists’ perception of the value of architectural heritage will determine how much attention and support they pay to heritage protection, which in turn affects their participation and willingness to pay. This paper establishes the value perception evaluation system of architectural heritage for Kumbum Monastery in China, quantifies tourists’ willingness to pay for heritage protection, and applies an interpretable machine learning model to analyze the causal relationship between value perception and willingness to pay, thereby providing a scientific basis for architectural heritage protection and utilization. According to the findings, tourists’ perceptions of the value of Kumbum Monastery are significantly differentiated, with a willingness to pay for the preservation of its architectural heritage ranging from RMB (China’s currency) 136 to RMB 203. The value perception of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery has a non-linear and complex influence on the willingness of tourists to pay. Engineers responsible for heritage protection projects, heritage managers (government), and tourism development companies should establish a design system for architectural heritage protection and utilization based on value perception over time and introduce positive design, negative design, and zero design strategies as needed to enhance the willingness of tourists to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

As an important material carrier of Tibetan culture, Tibetan religious buildings carry profound religious beliefs, historical memories, and artistic value. They not only serve as places for the religious activities of the Tibetan people but are also important bases for the inheritance and promotion of Tibetan culture. With the development of urban tourism and the expansion of its types, Tibetan religious buildings have gradually highlighted their tourism functions in recent years and have been favored by more tourists, thus introducing greater challenges in the protection of this architectural heritage [1]. It has become a basic rule for cultural heritage protection to take the necessary means to ensure that Tibetan religious buildings and their surroundings are not changed or are changed to a lesser extent so that people can truly feel their historical, cultural, and scientific value. Against the background of the pursuit of experience consumption, tourism has become an effective way to stimulate the vitality of Tibetan religious buildings and revive their historical and cultural blocks. Studies on tourists’ perception of architectural heritage value and willingness to pay have played a key role in improving tourism experiences and promoting the protection of historical buildings and cultural heritage [2].

Value perception is the subjective cognition and evaluation of the value of things, directly affecting the behavioral decisions of people. In the field of cultural heritage protection, the public perception of the value of Tibetan religious buildings will determine how much attention and support they provide for their preservation and thus affect their willingness to pay in this regard. Understanding the value perception of the public, especially tourists, and its relationship with willingness to pay is important for the development of scientific and rational cultural heritage conservation planning. Taking the Kumbum Monastery as an example, exploring the differences in tourists’ perception of the value of different buildings in the Chinese Tibetan historical and cultural blocks and analyzing their impact on the willingness to pay for heritage protection will profoundly reveal tourists’ travel preferences and provide a basis for the protection and utilization planning of architectural heritage [3]. It can also help fully understand the willingness of tourists to participate in the protection of architectural cultural heritage and lay a foundation for different stakeholders to jointly build a heritage protection community [4].

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Research Context on the Attributes of Architectural Heritage Value

Heritage value is an important issue in heritage conservation science. Heritage is the essence of the natural evolution of the Earth and the historical accumulation of human development, which is inherited or transmitted by future generations in a purposeful and selective manner in accordance with prevailing values. Axiology, as commonly interpreted, is the science of value in human life and its laws of consciousness and practice and is a comprehensive discipline consisting of the study of value in philosophy and the specific sciences. The value of architectural heritage usually refers to the historical, artistic, and scientific value of architecture, evaluated based on important indicators such as performance, features, and the extent to which it meets human needs. In past studies, some scholars have adhered to the theory of objective values. In the process of discussing architectural heritage, they often conclude that it has multiple values such as historical witness, social emotional bearing, and urban landscape shaping [5,6]. These values are regarded as objective, not dependent on subjective human perceptions, and are attributes inherent in the built heritage itself. Value cannot be separated from people and their needs. More and more scholars believe that the value of architectural heritage is a perceptual and comprehensive judgment of its inherent attributes, promoting the birth of the subjective value theory of architectural heritage [7]. In this process, the study of value shifts from an objective paradigm to a subjective one, and the value of architectural heritage is no longer limited to the realm of physical entities but is expanded to the realm of social relations. In conclusion, the value of architectural heritage is the result of the intertwining of objective inherent properties and subjective cognitive constructs. The objective value theory of architectural heritage emerged early, and the research system is well-developed. In contrast, although the subjective value theory of architectural heritage has attracted increasing attention, its research theory and technical methods are still gradually improving. It should be noted that the value of architectural heritage from a subjective perspective presents differences due to different research perspectives and cognitive subjects, and the perception of the value of architectural heritage by relevant subjects of interest directly affects their attitudes toward heritage protection. Experts and scholars can dig out unique values such as scientific rationality, artistic aesthetics, and cultural heritage significance from archaeological, historical, artistic, architectural, and other professional perspectives. For society at large, the complexity of judging value issues and the diversity of value subjects, based on daily experiences and emotional associations, lead to large differences in the values felt by different subjects, further prompting them to produce completely different attitudes and behaviors toward architectural heritage conservation [8,9]. Public perceptions and attitudes, in turn, also influence the direction of conservation and utilization of architectural heritage, thus contributing to the growing importance of research based on the subjective value theory of society at large [10,11].

1.2.2. Research on the Perception Method of Architectural Heritage Value

The study of value perception has its origins in economics and was initially used to analyze the trade-offs that customers make between the costs they pay for a product and the benefits they receive from it. In recent years, the research method of value perception has been gradually introduced into the field of architecture. For example, Kurnaz [12] analyzed the relationship between architectural visual perception and context in different periods, and Lipczynska [13] studied the impact of indoor green wall design on users’ environmental perception and happiness. The value perception method is increasingly used in the study of historical buildings and cultural heritage [14]. Ullauri [15] discussed the relationship between heritage values and citizens’ perceptions based on a case study of the Historic Center of Cuenca (Ecuador). Omiecinski [16] focused on the perception of technical equipment in historical buildings and analyzed their interference with the display of historical features and landscape characteristics of buildings. Petrevska [17] explored from the perspective of the local population whether tourism development has a positive impact on World heritage sites but negatively affects the ecological environment with outstanding universal value and residents’ perception of life quality, arguing that managers should be responsible for the outstanding universal value resources and take the necessary actions to improve the sustainability of tourism at the site. Fouad [18] analyzed the public perception of the visual characteristics and architectural features of the buildings in Port Said Historic Quarters, Egypt, using a visual preference survey and investigated the impact of public perception on the remodeling of the city’s heritage and historical image. Fang [19] conducted a study on local residents involved in tourism management and quantitatively analyzed the factors affecting local residents’ perception of responsibility for world heritage conservation based on a structural equation analysis model, finding that the recognition of heritage value and positive tourism impacts have an important influence on the formation of residents’ sense of responsibility to protect world heritage. Purwantiasning [20] found that local governments’ encouragement of local communities to raise awareness of cultural heritage protection in the form of seminars or forum group discussions effectively reduces opposition to urban heritage tourism and enhances community residents’ willingness to protect and preserve heritage. It should be noted that most of the studies suggest that residents’ perception of heritage value helps to enhance their willingness to participate in heritage conservation, but not all scholars support this view. For example, Wei [21] found that community residents’ perception of heritage did not enhance their willingness to protect it. To sum up, the study of value perception originating from economics has been widely applied in the field of architecture in recent years, and researchers of historical buildings and cultural heritage have explored the value perception of architectural heritage in depth from different perspectives, such as citizens’ perceptions, tourism influences, and visual preferences. However, the influence of value perception on the willingness to protect is still controversial.

1.2.3. Research on the Willingness to Pay for the Protection of Architectural Heritage

The willingness-to-pay method is the most commonly used tool for evaluating the economic value of goods and resources in non-market environments. Architectural heritage, as a public good, has great externality and cannot be valued by earning data from market transactions. Therefore, revealing people’s preferences for architectural heritage preservation and deriving their willingness to pay for its preservation and improvement by the willingness-to-pay method has grown to be another new frontier research field in historical and cultural heritage preservation [22]. Li [23] conducted a study on Nara, Japan, based on an ordered logistic regression model and found that residents’ attitudes toward the adaptive reuse of cultural heritage and the awareness of heritage preservation in historical and cultural cities enhance their willingness to pay. Nguyen [24] analyzed tourists’ preferences for protecting world heritage sites from coastal erosion and calculated their willingness to pay for different measures against coastal erosion. Kim [25] investigated the effect of perceived images and knowledge on willingness to pay for world cultural sites in Korea. Benedetto [26] analyzed tourists’ preferences and willingness to pay and estimated the monetary value of Italian karst caves. Jurado-Rivas [27] conducted a comprehensive analysis of survey data from different periods and discussed the change law of the willingness to pay for heritage protection over time and the role it plays in the life cycle of heritage tourism. Some scholars analyzed the impact of economic and social factors on the willingness to pay based on linear regression models or correlation coefficients, with a focus on factors such as gender, income, occupation, education, regional industrial structure, industrialization, and urbanization level of tourists [28,29]. In summary, more and more scholars have introduced the willingness-to-pay method into the study of architectural heritage protection and explored the willingness to pay of different subjects of interest, as well as the influence of their population characteristics on the willingness to pay. However, how value perception affects willingness to protect or willingness to pay has still not been effectively addressed.

1.3. Research Gaps and Goals

Overall, papers related to the perceived value of architectural heritage and willingness to pay for heritage conservation are still not particularly numerous but are being published at an increasing rate. As a new research field, it still has some shortcomings, mainly shown in the following three areas.

First, in terms of building types, there are fewer studies dedicated to religious architectural heritage. Different types of architectural heritage vary considerably in their characteristics, and their value perception and the willingness to pay for their protection are also different. The studies available have focused on historical and cultural cities, historical and cultural neighborhoods, and industrial and agricultural heritage. For example, Song [30] and Santoro [31] focused on the value perception of agricultural heritage systems, while García-Ruiz [32] and Bockelmann [33] turned to industrial heritage. Moreover, Pappalardo [34] and Park [35] discussed the willingness of different stakeholders to pay for the sustainability of world agricultural heritage sites. Religious architectural heritage carries historical, artistic, environmental, technological construction, and symbolic values, which makes it an important branch and frontier in the study of architectural heritage [36,37]. For example, Castillo [38] proposed a method to evaluate the cultural significance of religious architectural heritage built in stone and mud in Nicaragua. In comparison with agricultural and industrial heritage, only Falk discussed the willingness to pay for the heritage protection of Islamic religious architecture (Lahor) in a special study on the heritage value of religious architecture [39].

Second, from the perspective of survey respondents, there are few special studies on architectural heritage tourists. The utilization and preservation of religious architectural heritage involves multiple interest groups such as governments, enterprises (e.g., tourism companies), neighboring residents, and foreign tourists, whereas the attitudes of locals and local community aborigines [40], and heritage administrators [41,42] have been given more importance in the past studies. Tourist perception is the direct or indirect experience and subjective impression produced by the two-way interaction between visitors and architectural heritage. The identification and evaluation of tourist perception is a new direction in architectural heritage conservation protection, which is attracting more and more attention from scholars [43,44]. Tourism and architectural heritage conservation are in a close and complex relationship. First of all, tourism development plays a significant role in promoting the protection of architectural heritage. For example, tourism brings more funds to the restoration and protection of heritage, increases public attention, and stimulates enthusiasm for protection. Secondly, tourism development is also detrimental to the value of architectural heritage, as over-commercialization is eroding the landscape and reducing the value of heritage, and the influx of tourists exceeding the carrying capacity is accelerating the damage and disappearance of architectural heritage. As discussed above, some scholars have analyzed the value perception of agricultural and industrial heritage and the willingness to pay for its protection from the perspective of tourists, but it is still very rare in the field of religious architectural heritage, which is why it is worth attempting to make a breakthrough in this study.

Third, regarding the research methodology, there are few studies based on nonlinear emerging econometric models such as machine learning. Most of the current papers are based on traditional statistical analysis or qualitative analysis methods such as questionnaires [45], the eschatological approach [46], structural equations [47], and linear regression modeling [48]. Only a few scholars have proposed models of cultural heritage perception using new technologies, such as eye-tracking technology [49] and visual acuity [50]. These methods are still limited to the underlying logic of traditional statistical principles and are linear models in nature. However, there is a complex and nonlinear relationship between value perception and willingness to pay, and different elements of architectural heritage also influence each other in terms of perception, leading to biased analysis results based on linear models. In addition, scholars using regression model analysis pay more attention to external economic and social factors, and there is a need for studies on the impact of heritage value perception on willingness to pay.

This study conducted a questionnaire survey on Kumbum Monastery in Qinghai Province, China, to learn about tourist perceptions of the value of religious buildings, explore their willingness to pay for the protection of architectural heritage, and reveal the relationship between the two through a nonlinear model of machine learning. It provides a basis for the planning of historical and cultural heritage protection and the establishment of a community of interest groups. This study aims to address the following issues: the first is to gather general information about tourists and their perception of the value of Kumbum Monastery’s architectural heritage through questionnaires; the second is to calculate the willingness of tourists to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery using the conditional valuation method; and the third is to analyze the correlation between perceived value and willingness to pay through machine learning nonlinear algorithms.

Machine learning is an emerging method that is widely used and has many advantages over traditional regression models, highlighted in two ways. First, machine learning has a strong ability to fit nonlinear relationships, unlike regression models, which are often limited to linear assumptions and perform poorly when dealing with complex data. Second, machine learning allows the automatic learning of complex data patterns, the automatic screening and combination of important features, and a reduction in the manual feature construction workload, thereby eliminating the need to transitionally rely on the researcher’s a priori knowledge for cumbersome feature design and addressing the researcher’s interference with the model to a greater extent. There are many algorithms used for machine learning, such as SHAP, which can provide a visual interpretation of the model output, showing how much each feature contributes to the predicted result. Regression model explanations often rely on complex coefficients, which are hard to intuitively understand. The relationship between the perceived value of architectural heritage and individuals’ willingness to protect and pay for it is significantly nonlinear, and the interaction between the perceived elements and the willingness to act is exceptionally complex. Therefore, this paper creatively introduces a SHAP-based machine learning method, which not only enables us to effectively explain this complex nonlinear action process but also better provides guidance for decision makers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

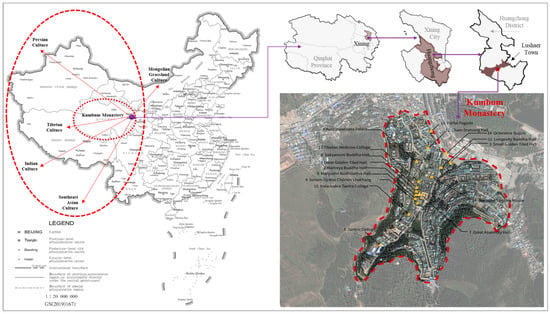

Tibetan Buddhist culture is the essence of Tibetan traditional culture and is an irreplaceable cultural feature and cultural advantage in Tibetan tourism. In Tibetan Buddhism, monasteries are the most important cultural carriers and places of inheritance, holding a special and significant position in Tibetan Buddhist culture [51]. Kumbum Monastery is one of these Tibetan Buddhist monasteries with a special historical position. It is located in Lusha’er Town, Huangzhong County, eastern Qinghai Province, 27 km away from Xining, the provincial capital. Founded in 1379 AD, it is the birthplace of Master Tsongkhapa, the founder of the Gelug School of Tibetan Buddhism, and is one of the six major Gelug monasteries (Ganden Monastery, Drepung Monastery, Sera Monastery, Tashilhunpo Monastery, Labrang Monastery, and Kumbum Monastery). Kumbum Monastery is surrounded by mountains, with the eight peaks surrounding it looking like an eight-petaled lotus flower. It is the result of the fusion of Tibetan and Han cultures, with a Han-style palace roof and flat-topped blockhouse-style Tibetan architecture, imposing and magnificent. The Monastery covers an area of 143 hectares with 52 halls, more than 10,000 rooms of monk apartments and other buildings, more than 100,000 cultural relics, and more than 800 monks. Recognized by the State Council as one of the first batches of China’s national key cultural relic protection units in 1961 and named a national 5A-level tourist attraction in 2015, Kumbum Monastery is the center of Tibetan Buddhism activities in Northwest China and enjoys a reputation in Southeast Asia and Central Asia, with a strong regional representation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cultural location and typical buildings of Kumbum Monastery.

2.2. Theoretical Logic and Research Steps

The basic elements for organizing perceptual processes are present in the structure of consciousness. The perception of complex space is the capturing of these basic elements, which elicits a predictable response in the healthy nervous system of the perceived object through subjective stimuli [52]. “Sensation” is the basis of human cognitive activity and is influenced by psychological and physiological factors. “Consciousness” is a complex sensation, which is the comprehensive knowledge and overall impression of what is perceived. “Perception” is a collective term for “sensation” and “consciousness”, mainly referring to the direct response of objective things in the human brain through sensory organs. The Value–Attitude–Behavior (VAB) model is a classic cognitive hierarchy model in social psychology research. It is a common theoretical framework used to analyze the influence of value perception on behavioral intention through attitude structure [53]. The VAB model explains the existence of complex causal relationships from abstract cognition (values) to intermediate cognition (attitudes) and from intermediate cognition to specific behaviors [54]. Based on the VAB’s theoretical logic, we know that tourist perceptions of the value of architectural heritage will determine their attitudes toward heritage protection and further shape their behavioral willingness to get involved and pay [55,56].

Therefore, this study can be broken down into the following key steps: The first step is to investigate tourists’ perception of the architectural heritage value of Kumbum Monastery, including the familiarity, channels to learn about it, and value grade evaluation. Only when tourists have a fundamental recognition of the cultural and historical values of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery can they arouse their willingness to protect the heritage. The second step is to investigate the willingness of tourists to protect the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery and analyze the ways they are willing to participate or the obstacles blocking their participation, so as to provide a basis for future protection measures. The third step is to estimate the willingness of tourists to pay for the preservation of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery using the contingent valuation method and further estimate the total value of the heritage. The fourth step is to quantitatively reveal the causal relationship between the perceived heritage value measured in the first step and the willingness to pay for heritage protection measured in the third step using machine learning models. The fifth step is to make recommendations for policy design based on the results of the analysis regarding the real needs for the conservation and utilization of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery.

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. Contingent Valuation Method: CVM

The CVM is one of the most commonly used tools to evaluate the non-use value of non-market environmental goods and resources. It has been widely used in recent years in the fields of historical and cultural heritage preservation and eco-environment conservation, such as architectural heritage preservation or green buildings [57,58]. The theoretical foundations of the CVM are rooted in the theory of public goods and are particularly closely related to the neoclassical economic theory of welfare analysis developed by Arthur Cecil Pigou and John Richard Hicks. The CVM is based on the principle of utility maximization and it usually directly asks people about their willingness to pay (WTP) or minimum willingness to accept (WTA) to compensate for heritage damage in the simulated market by means of questionnaires, so as to reveal the respondents’ preference for the protection and inheritance of historical and cultural heritage. This study is dedicated to providing a basis for the protection of Tibetan religious architectural heritage, so WTP is more suitable. The currently popular CVM questionnaire design methods include the payment card approach, the open-ended approach, and the binary approach. To obtain more standard analysis results, the payment card approach is used in this study. The willingness to pay is calculated based on the average value of the respondents, that is, after eliminating those who are unwilling to pay, the average value of all respondents willing to pay is calculated. The protection value of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery is calculated by probability statistics as follows [59]:

where refers to the willingness to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, represents the total number of participants in the survey, represents the number of respondents willing to pay for the protection of the Kumbum Monastery heritage, represents the monetary amount each person is willing to pay (an interval value in this study), represents the proportion of respondents willing to pay (that is, the probability of tourists willing to pay in the sample), represents the total value of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, and represents the total number of tourists in Kumbum Monastery throughout the year.

2.3.2. Explainable Machine Learning: Integrating SHAP and Light GBM

Machine learning models are based on the assumption of nonlinearity between variables and are capable of handling more complex data relationships. Compared with the traditional statistical linear regression model, machine learning has many advantages; however, the difficulty of interpretation is a challenge to be addressed in use. The Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) used in this article is a method for explaining the predictions of machine learning models. It is based on the concept of Shapley values in game theory. The core idea of SHAP is to decompose the prediction results of the model into the contribution value of each feature to the prediction results, so that the importance and role of each feature in the decision-making process of the model can be intuitively understood, thus providing a unified framework for the interpretability of the model [60].

A variety of algorithms such as decision trees, random forests, neural networks, XGBoost, and the light gradient-boosting machine (LightGBM) have been developed to explain machine learning, and there are differences when analyzing the results of different algorithms. After comparing and analyzing the algorithms, we selected the output results of the LightGBM algorithm for analysis in this study as it showed the best performance. The goodness of fit was 0.52 for the random forest algorithm, 0.64 for the XGBosoot algorithm, and 0.71 for the LightGBM algorithm. LightGBM is a fast and efficient gradient-boosting framework developed by Microsoft and is a member of the boosting tree family of integrated learning algorithms. It is based on a decision tree algorithm and combines a series of weak classifiers (decision trees) into a strong classifier via iterative training [61]. LightGBM works well with large datasets and is used in data mining, machine learning competitions, and different types of predictive tasks in the industry. The data analysis is performed by Python 3.8, with the willingness to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery used as the dependent variable and the perception of architectural heritage value used as the independent variable.

2.4. Data Source and Processing

Most of the data came from the questionnaire survey administered by the author, and a small amount came from the information provided by the managers of the Kumbum Monastery scenic spot during the interview. The questionnaire is the basis of the survey, and an on-site survey method was used in this study. The survey was performed between 1 and 8 August 2023, with a total of 300 questionnaires distributed, 247 collected, and 201 valid. The KMO coefficient of the questionnaire was 0.77 (0.000 for Bartlett’s test of significance), which is much higher than 0.6. Furthermore, Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.87, indicating the sound reliability and validity of the questionnaire and the high credibility of the survey results. A total of 22 questions were designed in the questionnaire, including “How much do you know about the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery?”, “What are your sources of knowledge about the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery?”, “What do you consider to be the most iconic public space at Kumbum Monastery?”, “How well do you think the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery is preserved?”, and “What do you think as the difficulties in preserving the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery?”. The questionnaire consisted of 4 parts, as outlined in the subsections below.

The first part was the beginning of the questionnaire, which briefly described the background information on the protection, development, and utilization of the architectural heritage and scenic area of Kumbum Monastery. It was very short, consisting of about 300 words, explaining the construction time, history, major events, cultural and regional influence, area and level of the scenic spot, important protection measures taken in the past, and capital investment of Kumbum Monastery.

The second part was a survey of the general information about the participants, including social and economic characteristics such as gender, age, occupation, education, and income. Scholars have analyzed the impact of these factors on willingness to pay by using them as independent variables in traditional studies, and there is a broad consensus in the academic community [62,63]. Therefore, this study no longer analyzed their effects on willingness to pay but rather used them as auxiliary analysis indicators for the overall situation, validity, and reliability of the questionnaire. Regarding the respondents, females accounted for 56.22% while males accounted for 43.78%, and they were predominantly young and middle-aged, with the highest proportion of those aged 30 and below (58.21%) and about 33% of those aged 30–50. The respondents had relatively high educational backgrounds, with 55% holding associate or bachelor’s degrees and 35% having a history of junior or senior high school education. They were mainly self-employed individuals, business and service industry practitioners, government workers, and enterprise managers, accounting for nearly 50%. In addition, respondents included farmers, migrant workers (those with agricultural household registration but working in cities), and students. The respondents were highly influenced by the regional culture, with the majority being tourists from local or neighboring regions and about 30% coming from other places. Our analysis of tourism statistics and interviews with managers showed that during the “May Day” and “National Day” holidays, visitors to Kumbum Monastery mainly come from Qinghai and neighboring provinces (Tibet and Gansu). During the non-holiday period, Kumbum Monastery tourists are mainly from Huangzhong County and its surrounding counties (such as Huangyuan County, Haiyan County, Guide County, Hualong County, and Datong County). Kumbum Monastery has been deeply embedded in the daily lives of local and surrounding residents. About 50% of the questionnaires were obtained in Kumbum Monastery and about 31% were obtained in the nearby villages, towns, and block shops outside the Kumbum Monastery Scenic Area. The rest of the questionnaires were mainly from the staff of Huangzhong County’s culture, religion, tourism, and other involved government departments, as well as urban residents.

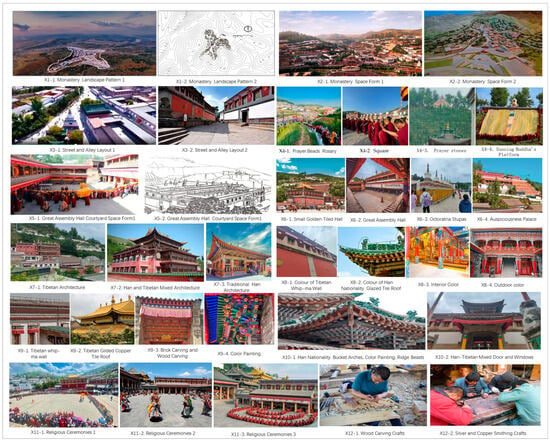

The third part was a survey on the participants’ value perception of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, including the familiarity of the respondents with the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, the channels to learn about it, the attitude toward protection, and the value perception of the key buildings. Kumbum Monastery is a building group composed of many temples, sutra halls, stupas, and monk apartments. There are great differences in the perception of different buildings, and the recreational preferences of tourists are also completely different. Based on the analysis of the pre-survey, we focused the value perception on 12 dimensions. In machine learning regression analysis, their codes were marked as –. The names and codes of 12 perceptual elements are given in Table 1, and their images are shown in Figure 2. Most of the pictures are from official and tourist WeChat Service Accounts, with a small portion taken by the author. In addition, Figure 2(X5-2) is derived from Li Qun’s Ancient Architecture in Qinghai, and Figure 2(X12-2) is derived from Chen Meimei’s paper Research on Silver and Copper Smithing Crafts and Craftsmen in Huangzhong, Qinghai province.

Table 1.

The 12 important perceptual elements and their codes.

Figure 2.

Images of 12 important perceptual elements of Kumbum Monastery.

The fourth part was an exploration of the willingness of the participants to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, including the method and amount of respondent participation in the protection of the Monastery. Willingness to pay was based on a payment card questionnaire, and the core valuation question of the payment card was “How much would you be willing to donate if you are asked to pay for the protection of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery (mark “√” on the selected amount)?”. According to the analysis of the results, we set the bid card values for willingness to pay as 0 yuan, 0–50 yuan, 50–100 yuan, 100–200 yuan, 200–300 yuan, 300–400 yuan, 400–500 yuan, and 500 yuan or more. A separate conversation about the reasons for opposing payment was held among those who were willing to pay zero yuan.

3. Results

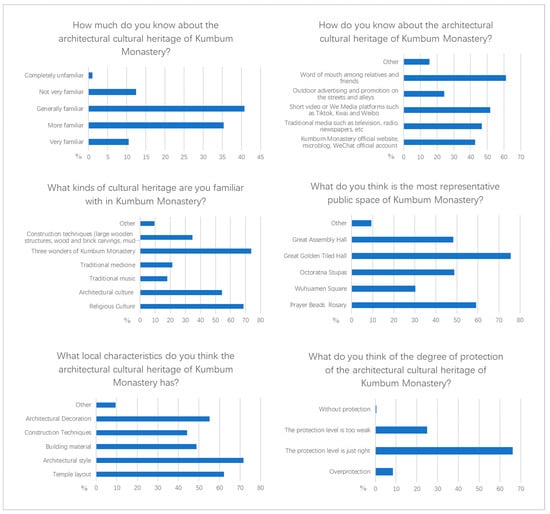

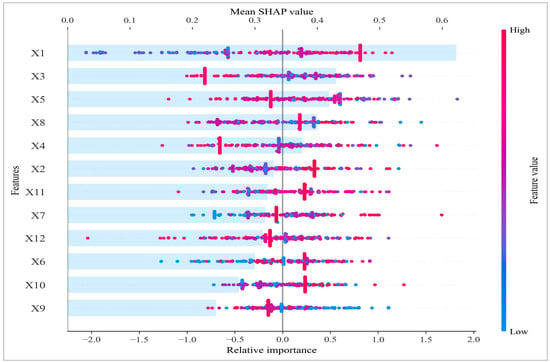

3.1. Heritage Familiarity Analysis

In terms of familiarity, most of the respondents in the survey were familiar with the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, and most of them were attracted by its fame. Only two respondents (less than 1%) were completely unfamiliar with it and were traveling with friends. The information acquisition channels of the respondents regarding the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery were very diversified. The proportion of those obtaining information on the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery through word of mouth from relatives and friends was highest, reaching 61.19%. With the advent of the information age, we-media platforms and short videos are playing an increasingly important role. Those who acquired information on the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery from Tiktok, Kuaishou, Weibo, and other channels accounted for 51.74%. The power of traditional media should not be overlooked, with TV, radio, and newspapers contributing 46.77%. The self-built official publicity channel of Kumbum Monastery also played an irreplaceable role, with its official website, microblog, and WeChat official account contributing 42.79% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Analysis of tourists’ familiarity with the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery.

From the perspective of cultural heritage types, “the three masterpieces of Kumbum Monastery (frescoes, barbola, and butter sculpture)” were the most familiar characteristic field, accounting for 73.63% of the total. Religious culture was the second label of Kumbum Monastery, with a recognition rate of 68.66%. The architectural culture label ranked third, with recognition reaching 54.23%. The architectural construction techniques (carpentry work structures, wood and brick carvings, clay tiles, colorful paintings, and roof decorations) amounted to 34.83%, indicating that the architecture is one of the core features of Kumbum Monastery. The recognition of cultural characteristics such as traditional music and medicine was at a low level at around 20%. Of the landmark buildings, the Great Assembly Hall was the most represented, with a recognition rate of 75.62%. The Prayer Beads Rosary ranked second, with a recognition rate of nearly 60%. The Great Golden Tiled Hall and Octoratna Stupas enjoyed the same representativeness, with recognition of around 50%. The recognition of Wuhuamen Square needs to be improved, currently at only 30%.

Among the respondents, 71.64% believed that the architectural style was the biggest feature of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, and the characteristics of the layout of the temple ranked second, with recognition accounting for 62.19%. The features of architectural decoration and building materials should not be overlooked, with recognition at around 50%. The degree of uniqueness in construction techniques was at the lowest level at 44.28%. Moreover, 66.17% of the respondents believed that the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery was satisfactory, which is the view with the highest support. Those who thought that the protection was less intensive accounted for 24.88%, indicating that there is still room for improvement in the protection of the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery in the future.

3.2. Value Perception and Willingness to Pay Survey

In this paper, value perception is divided into five levels using the Likert scale development method, with 1 being the lowest and 5 being the highest. We calculate the value perception of the different dimensions of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery using the mean value method. Overall, the respondents’ perception of the architectural cultural heritage value of Kumbum Monastery was 3.97. In 2 of the 12 dimensions, local perception is higher than global perception, including landscape pattern integrity (the relationship between mountains, water, and the location of the monastery), environmental pattern integrity (paved areas, trees, prayer stones, and other scenic and material elements), courtyard layout integrity (the layout of temples, sutra halls, and other spaces), architectural pattern authenticity (such as the patterns of the Buddhist halls, sutra halls, pagoda, living Buddha’s residence, and other buildings), architectural style authenticity (traditional Tibetan style, Tibetan–Han style, and local architecture), architectural color authenticity (the original local ethnic characteristics), architectural material authenticity (materials used in buildings), architectural decoration authenticity (carving of doors and windows, capitals, roof charms, and color paintings), and construction technique inheritance (large wooden structures, wood and brick carvings, tiles, color paintings, and roof decorations). The average satisfaction of tourists with the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery was 3.92, with the highest level of satisfaction for architectural style authenticity () and the lowest for street and alley layout integrity () (Table 2).

Table 2.

Value perception of Kumbum Monastery’s historical and cultural heritage.

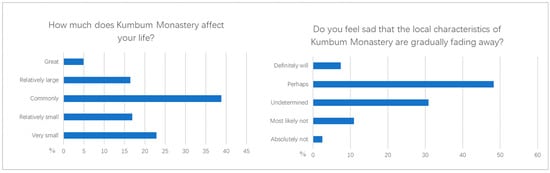

From the attitude of the respondents, 38.81% believed that the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery had affected their lives to a certain extent, with a relatively low proportion believing that the impact was significant in general. According to the survey, less than 5% of the respondents considered the impact to be significant, but those who considered the impact to be very low accounted for 23%. Furthermore, 48.26% of the respondents said they would be saddened by the destruction or dilution of the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery (Figure 4). Since this survey was designed primarily for tourists and not for the indigenous people around Kumbum Monastery, it is logical that a low proportion thought it had a big impact on their lives. Tourists expressed sadness at the destruction of heritage or the dilution of its characteristics, indicating to a certain extent that the subsequent survey of ways to participate in the protection of Kumbum Monastery and the willingness to pay is based more on their responsibility or sentiment than on their own economic interests.

Figure 4.

Attitude toward the protection of architectural cultural heritage in Kumbum Monastery.

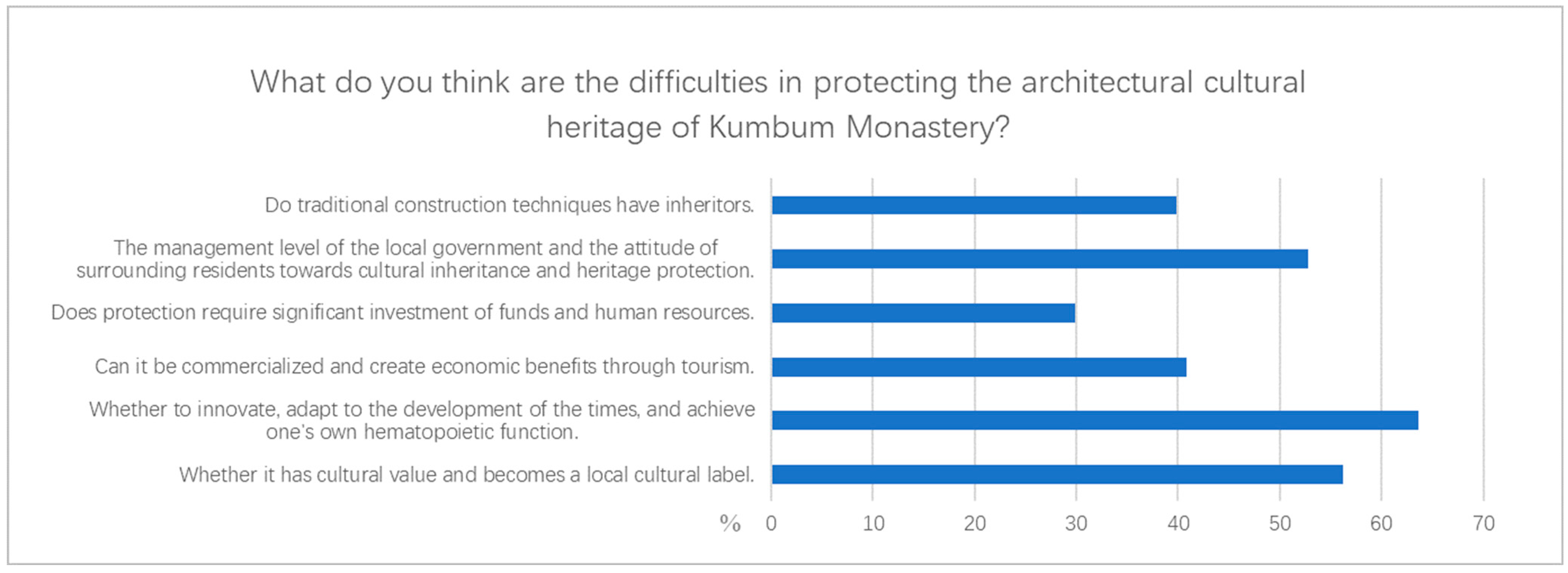

Full awareness of the difficulties in heritage conservation is key to a shift in attitude to behavior. According to the survey results, 63.68% of the respondents believed that the biggest dilemma in the protection of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery is whether it can continue to innovate and realize its own hematopoietic function so as to better adapt to the development needs of the new era. Kumbum Monastery is the first pilot attraction to open and implement the policy of “supporting temples with temples” after China’s launch of reform and opening up. Although it has established a diversified income system over the years, including religious activities, tourism income, commercial activities, and the development of cultural industries, the protection of its architectural cultural heritage requires a large amount of financial investment, and its ability to be self-sufficient remains an issue that must be given sustained attention in the future. Whether or not Kumbum Monastery has cultural value or the potential to be a local cultural label is a second key difficulty in the protection of its architectural heritage, with 56.22% of respondents supporting this view. The management level of the local government and the attitudes of the neighboring residents toward cultural inheritance and heritage protection are the third difficulty, which is also supported by more than 50%. The economic benefits created by commercialization, especially tourism, and the availability of sufficient cultural inheritors also received widespread attention, both supported by about 40% (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Difficulties toward the protection of architectural cultural heritage in Kumbum Monastery.

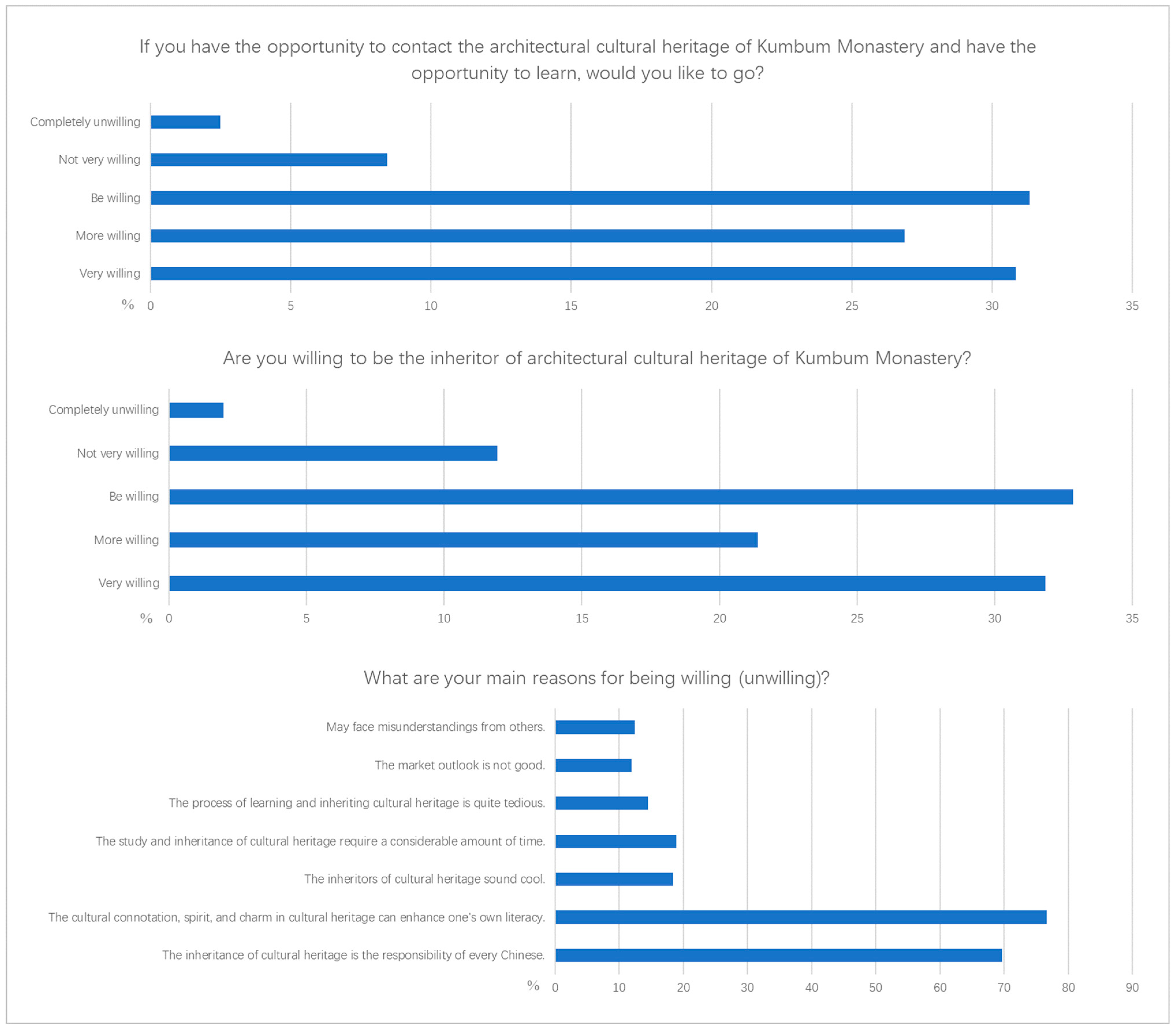

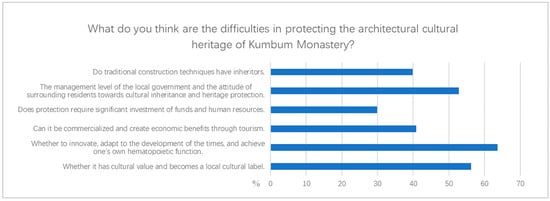

In general, personnel and money are the core challenges faced by Kumbum Monastery, and they correspond to the participatory approach and willingness to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage. In terms of personnel, first of all, more people need to be involved in publicizing Kumbum Monastery and driving the wider public to learn and understand it so as to create a sufficient number of heritage cultural inheritors. Regarding money, it is necessary to define the responsibilities and rights of different stakeholders and enhance the willingness of tourists to pay for the protection of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, thus further expanding the funding channels. The survey showed that more than 80% of the respondents were willing to participate in publicizing the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, and 31.84% were very willing. It can be seen that tourists have a high willingness to publicize Kumbum Monastery, and its managers should provide timely cooperation as appropriate. The results of the survey showed that more than 85% were willing to learn and understand the cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery, which laid a good foundation for the effective implementation of publicity work. More than 70% of the respondents were willing to be the inheritors of the cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery. The most essential reason is that the cultural connotation, spirit, and charm of heritage may enhance their self-education and they are firmly convinced that it is the responsibility of every Chinese person to pass on cultural heritage. With the rejuvenation of China, cultural confidence and the rise of culture have received widespread attention. The cultural heritage of the nation is the cultural heritage of the world. Kumbum Monastery is a Tibetan Buddhist temple with great influence in both Southeast Asia and Central Asia. As a result, about 20% of the respondents thought it would be cool to be an inheritor of the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery. Of note, there were still more than 25% of respondents less willing or even not willing at all to be an inheritor, mainly because the study and inheritance of the cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery was boring and time-consuming with an unclear market prospect. The attitudes of those around them also interfere with the training of the inheritors, mainly due to the negative impact brought by misunderstanding or incomprehension (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Promotion and inheritance in the protection of architectural cultural heritage in Kumbum Monastery.

From the willingness-to-pay survey, respondents willing to pay RMB 0–50 accounted for 10.95%, those willing to pay RMB 50–100 accounted for 38.31%, those willing to pay RMB 100–200 accounted for 19.4%, those willing to pay RMB 200–300 accounted for 8.46%, those willing to pay RMB 300–400 accounted for 9.45%, those willing to pay RMB 400–500 accounted for 4.98%, and those willing to pay more than RMB 500 accounted for 6.47%. We can calculate the willingness to pay for the protection of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery as RMB 136–203 using Equation (1) with the proportion as the weight. At the time of the survey, the managers reported that the average number of tourists in Kumbum Monastery in the past five years was 3 million, and those willing to pay accounted for 98%. Therefore, according to Equations (2) and (3), the value of willingness to pay for the protection of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery is calculated as RMB 400–600 million. Tourists refused to pay mainly because they believed that they had already paid for the ticket and that the protection of the architectural cultural heritage was the responsibility of the government and the tourism development company. Moreover, the low income of tourists, who did not have sufficient ability to pay, was also an important factor. Of note, some tourists explained that they chose not to pay, not because they were unwilling to do so but rather because the current donation system was not transparent. They believed that the money donated to Kumbum Monastery would not be used for the special purpose of protecting the architectural cultural heritage.

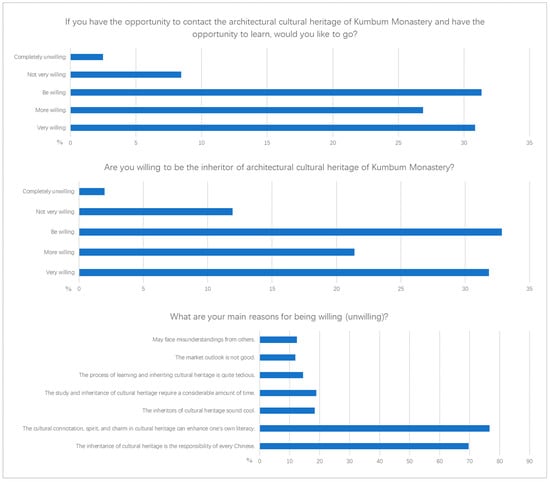

3.3. Influencing Factors Analysis

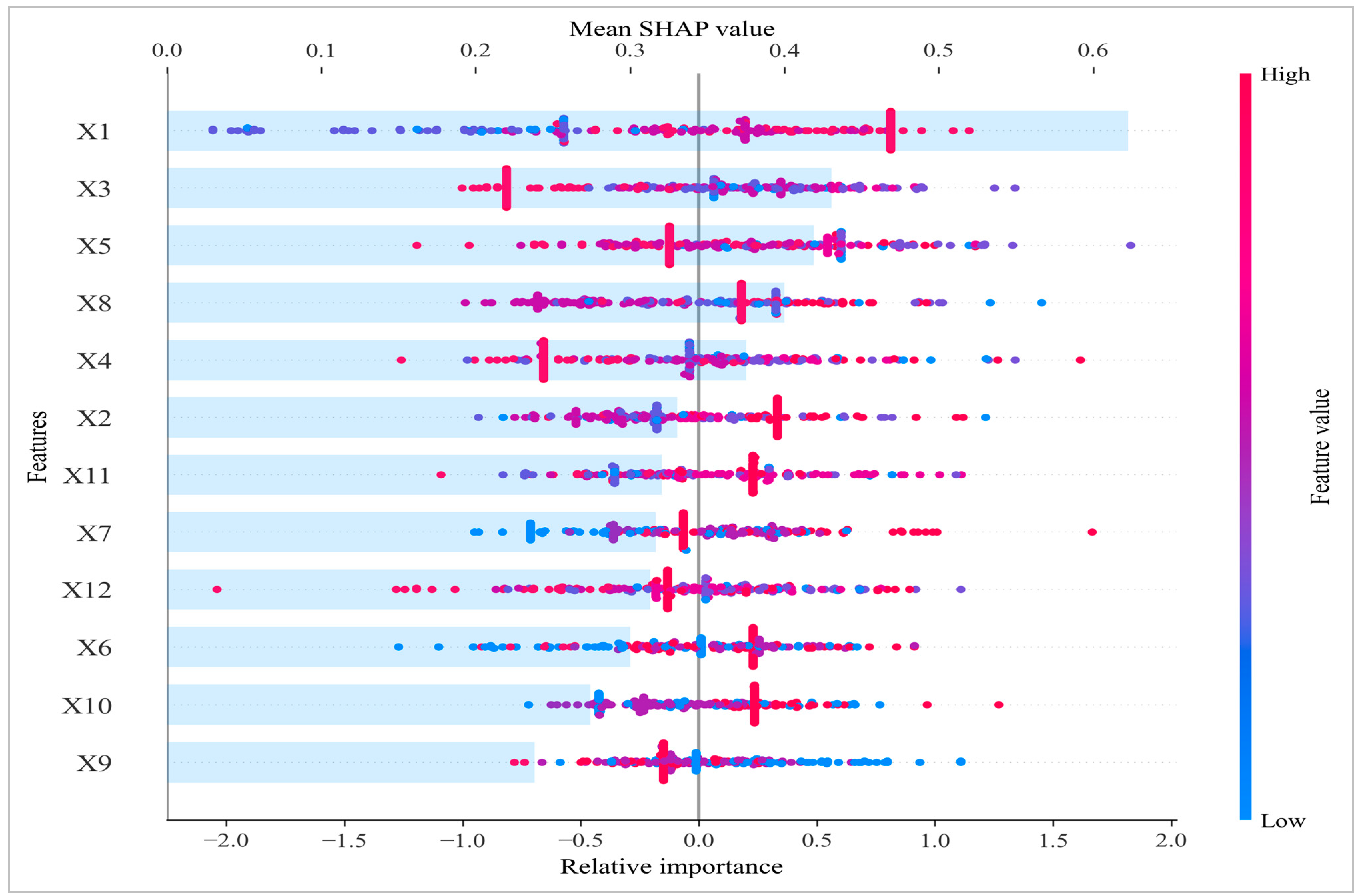

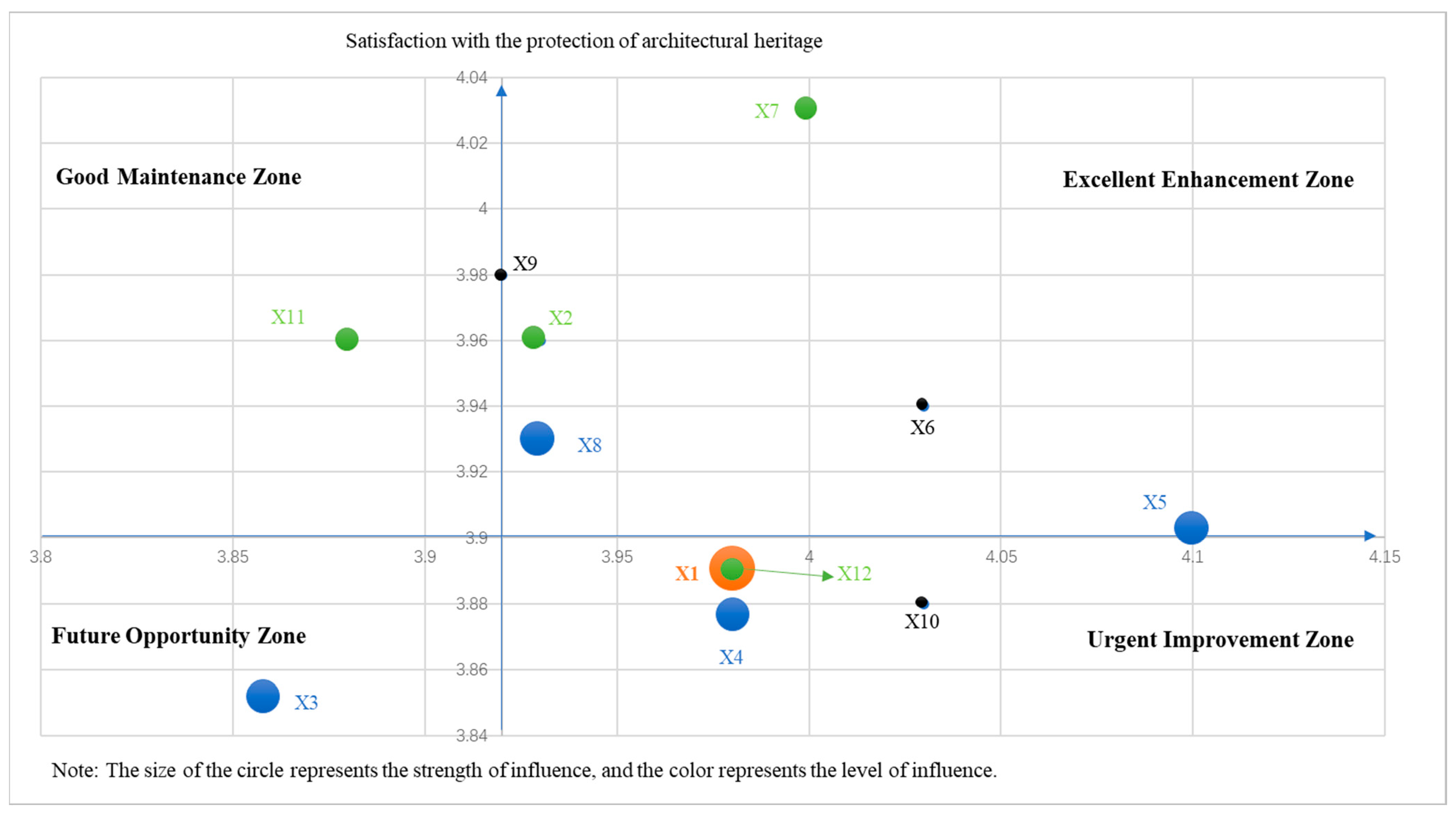

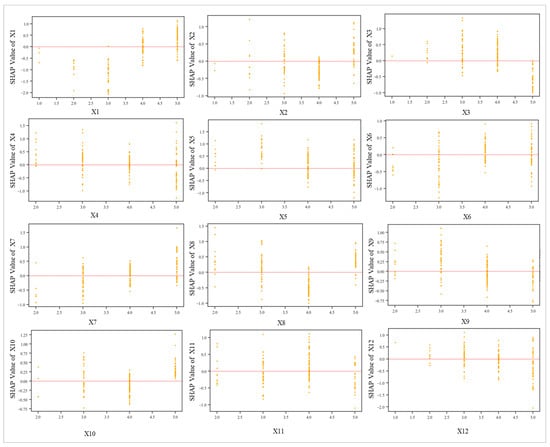

According to machine learning regression analysis, the value perception of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery across the 12 dimensions shows significant differences in the impact on willingness to pay. In terms of influence intensity, landscape pattern integrity () has the highest influence, which is much higher than other factors, and plays a key role in the willingness to pay. Kumbum Monastery was built in the mountains, characterized by the spatial pattern of a lotus shape, which is publicized as the highlight of tourism and has attracted many tourists. Architectural material authenticity () has the lowest influence, much lower than the other factors, with a largely negligible direct effect on willingness to pay. Both architectural pattern authenticity () and architectural decoration authenticity () have a low influence. Tourists have the initial intention of a cultural experience and lack attention to architectural material authenticity, decorations, and styles and do not have sufficient knowledge to identify them so their low influence is justified. The value perception of street and alley layout integrity (), courtyard layout integrity (), architectural color authenticity (), and environmental pattern integrity () also plays an important role in influencing willingness to pay and can be classified together in the second tier. The influence of monastery form integrity (), public space liveliness (), architectural style authenticity (), and construction technique inheritance () should not be ignored (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Feature importance and SHAP summary plot in Kumbum Monastery.

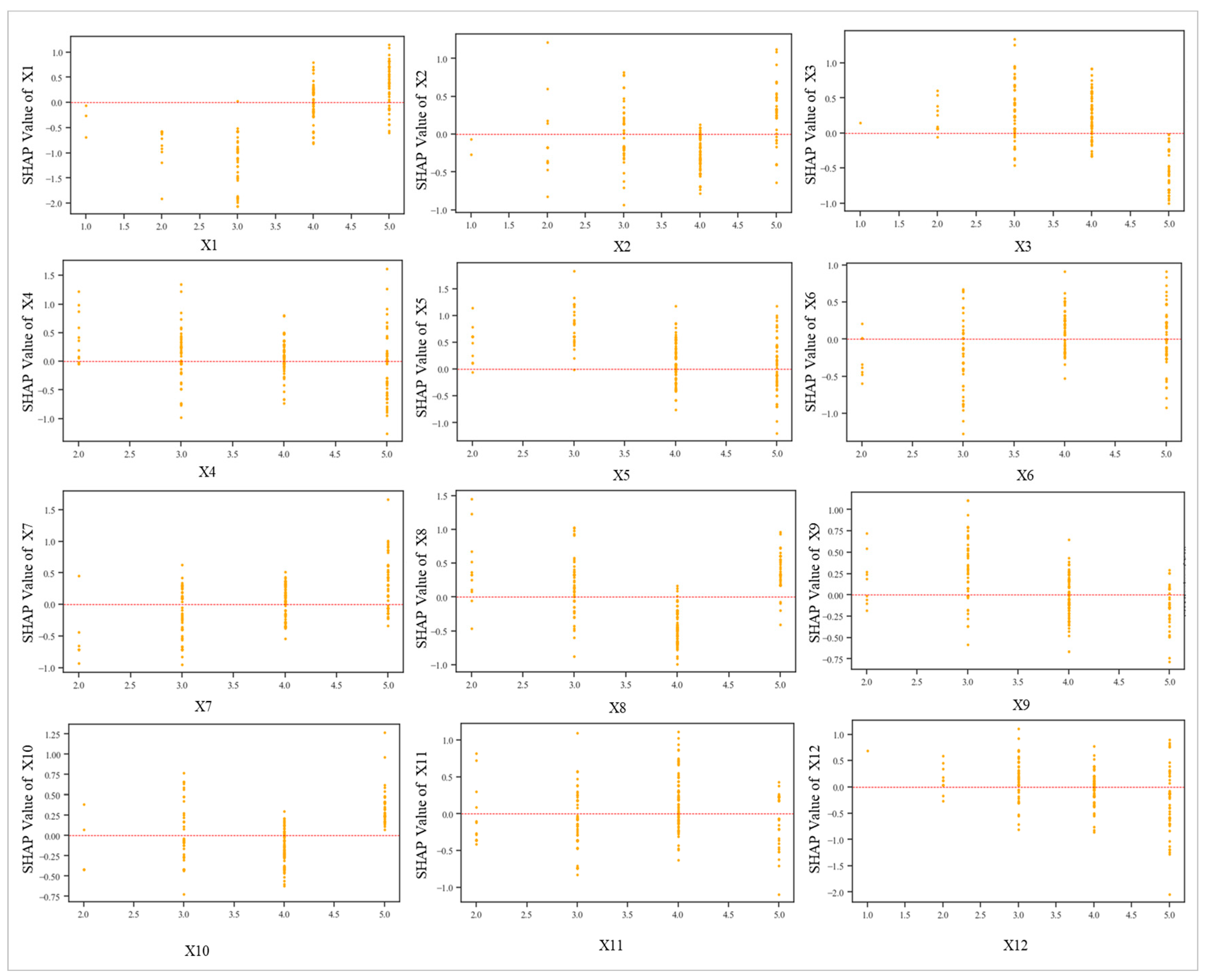

Figure 8 shows the local dependence of the value perception of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery on the willingness to pay, which provides an intuitive method to clarify the nonlinear causal relationship between the two. The relationship in the figure helps us evaluate whether the value perception of each dimension of architectural cultural heritage has a linear or non-linear impact on the willingness to pay and whether it has any inflection points or thresholds. There is an inflection point in the influence of landscape pattern integrity () and environmental pattern integrity () on the willingness to pay. The former plays an inhibitory role when the perception is medium to low and a mixed role when the perception is high (i.e., positive promotion and negative inhibition). The latter plays a positive promoting role at low perception and then changes to a mixed role. Courtyard layout integrity () and environmental pattern integrity () share a similar mechanism, but the inflection point is further delayed. There are two inflection points in the influence of street and alley layout integrity () on the willingness to pay, with a positive role at low perceptions, a mixed role at medium perceptions, and a shift to a negative role at high perceptions. The influence mechanisms of monastery form integrity (), architectural pattern authenticity (), architectural style authenticity (), architectural color authenticity (), architectural material authenticity (), and public space liveliness () have a high degree of similarity. Regardless of any changes in perception, their influence is mixed and relatively balanced at different perception levels. Architectural decoration authenticity () plays a mixed role at low levels of perception, gradually transforming into a positive effect as perception increases. The influence of construction technique inheritance () on the willingness to pay gradually shifts from positive to mixed, and the group size of the variable gradually increases. In general, the influence of value perception of the 12 dimensions on the willingness to pay for the protection of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery is non-linear, and there is an inflection point of positive to negative and negative to positive.

Figure 8.

The nonlinear impact of value perception on willingness to pay in Kumbum Monastery.

4. Discussion

Multi-sensory analysis is used in the architectural design and conservation research of historical and cultural neighborhoods to enhance the public perception of space and heritage. It also meets the needs of the public through behavioral guidance, showing a trend of “neural shift”, which increasingly emphasizes the subjective characteristics of emotion, body, and “irrationality” [64,65]. The storage of historical information and the inheritance of cultural characteristics are important symbols that distinguish historical and cultural districts from other tourist destinations in tourism development. Authenticity and integrity, as the core characteristics of architectural cultural heritage, are the initial motives to attract tourists to recreation and experience. Exploring the differentiated characteristics tourists present in their perception of architectural heritage value and the mechanisms that cause such differentiated characteristics is a scientific question that needs to be addressed and resolved. We found in this study that tourists have significant differences in their perception of the value of architectural heritage and that these differences are gradually transferred to the domain of willingness to pay for heritage protection, which is in agreement with the findings of other scholars.

It is worth noting that different from the findings of scholars in previous studies, this study found that the influence of value perception on willingness to pay is nonlinear, which is an innovative observation. Numerous studies have shown a significant positive correlation between the perceived value of architectural heritage and willingness to pay for architectural heritage conservation. The public is more willing to pay for the preservation of architectural heritage when they have a deeper perception of the historical, artistic, and cultural value of the architectural heritage. For example, Lin et al. [66] found that enhancing tourists’ perception of the sanctity of the destination and real tourism experience and enhancing believers’ ability to participate in local residents’ religious activities significantly improve the perception and experience of the authenticity of religious architectural cultural heritage tourism, and it is the key for tourists to participate in the protection of local traditional cultural landscape and related commercial activities. Whether using causal decision analysis models or questionnaires and interviews, scholars’ data analyses show that tourists’ willingness to pay for heritage preservation is stronger when they have a higher perception of heritage value. In previous statistical modeling studies, scholars believed that there was a linear relationship between the two. We have always expected heritage managers to further increase tourists’ perception of positive value; in contrast, we hope to take some design measures to reduce tourists’ perception [17]. Research on machine learning has shown that willingness to pay does not necessarily increase or decrease monotonically with value perception and that there is a clear inflection point between them. Since the influence of value perception on the willingness to pay for architectural heritage protection is always in a state of dynamic change [27], managers need to carry out special research on their own heritage to develop differentiated response strategies over time. This differentiation should take into account the multi-dimensional differences of region, heritage type, and development period.

The inspirational value of this study lies in the fact that tourists build differentiated value perceptions based on their existing knowledge and experience through imagery cognition and experiential interactions with architectural heritage, where the results of these perceptions are nonlinearly counteracted in the preservation and utilization of architectural heritage itself. Value perception plays a key mediating role between heritage protection and tourist satisfaction. The sustainable development of architectural heritage can be promoted by reasonably building a bridge between heritage protection and heritage consumption [67,68]. First, for heritage conservation, tourists are more aware of the urgency and importance of conservation when they have a deeper sense of the value of architectural heritage. For example, tourists will have a strong desire to protect it in their hearts when they have a deep understanding of the historical context of the century-old religious and cultural heritage and the unique architectural skills carried out in Kumbum Monastery. This willingness may then translate into practical actions, such as voluntary compliance with conservation rules, donations to conservation projects, and tangible contributions to heritage conservation. Second, value perception is the core influencing factor in tourist satisfaction. Visitors judge the tour experience based on their own insights into the historical, artistic, cultural, and other diverse values of the heritage of Kumbum Monastery. Tourists will greatly improve their satisfaction with the tour during their visit when they understand the social significance of Kumbum Monastery in the intersection of ethnic cultures such as Han, Tibetan, and Hui and appreciate the aesthetic style of the integration of architectural appearance and interior. In contrast, when tourists are ignorant of the value of heritage, they tend to turn the visit into a superficial formality, thus making it difficult to access deep satisfaction. Overall, strengthening tourists’ perception of the value of architectural heritage will inject momentum into heritage protection and significantly improve tourist satisfaction, thereby achieving a win–win result for heritage protection and tourism development. It is crucial to focus on promoting the sustainable development of cultural heritage as an important entry point for future design.

Therefore, it is necessary to establish a new model of sensory element-oriented architectural heritage conservation and utilization based on the complex relationship between value perception and willingness to pay. Tourists place themselves in architectural heritage through excursions and cultural experiences, and their perception of heritage elements such as the natural landscape, spatial patterns, iconic architecture, scenic facilities, cultural activities, consumption services, time arrangement, and characteristic atmosphere is direct feedback on the effect of architectural heritage protection and utilization. For the future protection and utilization of architectural heritage, designers and managers should design spatial expressions oriented to sensory preferences based on the feedback of tourists’ whole-sensory and whole-process experience [69]; in other words, carrying out the design of heritage conservation and utilization based on tourists’ perceived preferences to effectively control the key perceptual elements so as to stimulate tourists’ willingness to pay and promote heritage protection on the path of positive circular sustainable development. There are three modes of sensory-oriented architectural heritage protection and utilization design: (1) positive design—adding new elements of tourists’ perception preferences to the original architectural heritage; (2) negative design—removing elements of architectural heritage that do not match tourists’ perception preferences; and (3) zero design—protecting and preserving heritage elements that have already met the preferences of tourists in their original state without any changes. Notably, designers should not be bottomless in accommodating tourists but rather should be guided by the reasonable preservation of architectural heritage. To ensure that there is no human-induced developmental damage to architectural heritage, designers must be cautious when adopting positive and negative design strategies so as to coordinate the conflict between cultural protection and tourism development for cultural protection and inheritance, as well as economic and social advances [70]. Before proceeding to positive or negative design, planners need to control potential damage through two necessary steps. First, they need to organize and conduct extensive questionnaire surveys and interviews with key figures to extract commonalities among different stakeholders, especially their action logic or core motivations [71]. Secondly, in response to tourist preferences, designers need to invite experts and managers of architectural heritage protection to conduct special demonstration studies and an in-depth analysis of the feasible means to meet certain preferences, possible hazards, and necessary measures to reduce the impact [72].

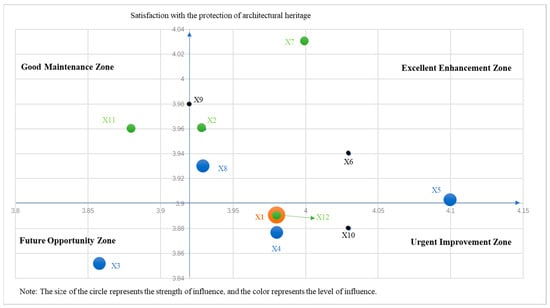

For example, for Kumbum Monastery, the perception elements across the 12 dimensions are classified into 4 categories by integrating value perception, willingness to pay, and the relationship between them, and differentiated design strategies are adopted in future architectural heritage protection and utilization planning. The Excellent Enhancement Zone has a high level of value perception and protection satisfaction, and its members include monastery form integrity (), architectural pattern authenticity (), architectural style authenticity (), and architectural color authenticity (). They are areas that should be focused on and improved in future design, especially as has a high influence on the willingness to pay. Members of the Good Maintenance Zone include public space liveliness (), which is characterized by a high level of protection satisfaction with low value perception. A zero-design strategy should be employed in the future, with the goal of maintaining the status quo and requiring no additional investment. The only member of the Future Opportunity Zone is street and alley layout integrity (), which has low value perception and protection satisfaction. When there are limited funds, negative design should be prioritized to remove inhibitions, and zero design should be adopted more often than positive design, thus leaving opportunities for the future. The members of the Urgent Improvement Zone include landscape pattern integrity (), environmental pattern integrity (), architectural decoration authenticity (), and construction technique inheritance (). They have high value perception but low satisfaction. In the future, positive design and negative design should be integrated to improve the perception elements that fit tourists’ preferences, while controlling those that do not fit, so as to enhance satisfaction and willingness to pay. It is worth noting that courtyard layout integrity () and architectural material authenticity () are on the coordinate axes, indicating that they can be used in both zoning strategies (Figure 9). In addition, some of the views found in the questionnaire survey also provide a reference for decision-making on the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery. For example, tourists have a high willingness to publicize Kumbum Monastery and learn about the architectural heritage. Therefore, managers should strengthen the design of publicity to enhance the perception of the value of architectural heritage and the sense of mission in protecting architectural heritage. Again, tourists who refuse to pay have concerns about the financial transparency of Kumbum Monastery. Therefore, an open and transparent system for the use of funds should be established over time so that the funds can be earmarked for specific purposes, which can effectively catalyze and enhance the willingness of tourists to pay for the protection of the heritage.

Figure 9.

Decision basis for the protection of the architectural and cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery.

Of note, although the willingness-to-pay method was used to estimate the non-use value of the architectural cultural heritage of Kumbum Monastery in this study, the value is only of the reference value, and decision makers need to conduct more surveys to improve the accuracy of the data before applying it in reality [73]. The perceived value of architectural heritage is highly subjective and complex, making it difficult for respondents to measure it accurately, so they can only bid on the basis of a vague sense of goodwill. Moreover, respondents do not have to actually pay money, so they are more than happy to give higher values to show their support for heritage preservation [74,75]. The problem of respondents’ overestimation can be solved in future research through the following measures: The first is to optimize the questionnaire design, which can be conducted in an anonymous and weakly guided way to reduce social expectation bias, such as setting situational assumptions to make respondents make more real choices. The second is to strengthen the popularization of information, provide detailed information on architectural heritage protection in advance, cover maintenance costs and expected benefits, and assist respondents in making rational bids so that the assessment of willingness to pay more accurately reflects reality. The third is to carry out regular surveys with the aim of identifying common characteristics of the same population through a wide range of surveys of several different populations and comparing them with the results of other analyses of similar architectural heritage in order to determine the final conclusions. Of course, decision makers can also correct willingness-to-pay data by directly applying relevant research findings; for example, Kon believes that it may be overestimated by 12% in general [76].

5. Conclusions

For architectural heritage value perceptions to be explored, which are highly subjective and have a complex and multidimensional structural hierarchy, determining how to perform quantitative analysis and induction and gather feedback has become a key scientific problem that this study attempts to solve. Based on the case study of Kumbum Monastery in China, this paper deeply explores the nonlinear relationship between architectural heritage value perception and willingness to pay using a questionnaire via the CVM and interpretable machine learning methods, providing a rigorous basis for the scientific protection and utilization of architectural heritage.

The main conclusions reached in this study are as follows. First, the channels through which tourists understand Kumbum Monastery are increasingly diversified, and there are significant differences in the value perception of architectural heritage. The perceptions of courtyard layout integrity, architectural pattern authenticity, architectural style authenticity, and architectural decoration authenticity are the highest, while the perceptions of street and alley layout integrity and public space liveliness lag behind significantly. Second, the quantitatively measured willingness of tourists to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery is RMB 136–203, and its non-use value is further estimated to be RMB 400–600 million. Third, the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery has a complex effect on the value perception and tourists’ willingness to pay in a nonlinear way. The intensity, nature, and mechanisms of different factors differ significantly. Architectural material authenticity, street and alley layout integrity, courtyard layout integrity, architectural color authenticity, and environmental pattern integrity are key factors. Fourth, designers and managers should establish an architectural heritage protection and utilization design system based on value perception as soon as possible and enhance the willingness of tourists to pay for the protection of the architectural heritage of Kumbum Monastery by reasonably combining positive design, negative design, and zero-design strategies.

The biggest innovation of this paper is the introduction of a machine learning model to explain the nonlinear and complex relationship between the perceived value of architectural heritage and tourists’ willingness to pay. It pushes the research paradigm from linear to nonlinear analysis and provides heritage managers with a more accurate basis for decision making. It is noteworthy that this study also has shortcomings, which should be circumvented in the application of the analyzed results and can provide a new direction worthy of breakthroughs in future research. On one hand, the self-filling questionnaire method has its own limitations. Architectural heritage protection is a positive individual act, and respondents may fill in options that do not match their actual performance in order to meet social expectations when filling out questionnaires. A combination of experimental methods, field observations, and in-depth interviews can be attempted to reduce such a limitation in future studies. On the other hand, both value perception and willingness to pay are dynamic processes, i.e., people perceive and experience the distinctive elements of architectural heritage through their psychological and physiological issues and engage in spiritual and emotional feedback on the cultural archetypes, symbols, and concepts they carry. The questionnaire survey in this study only reflects the value perception and willingness to pay of tourists according to the cross-section of the survey time point. Therefore, multi-period questionnaire surveys should be conducted regularly or irregularly in the future, and time-series comparative analyses should also be carried out, so as to uncover the patterns of value perception and willingness to pay in different periods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.C. and P.Z.; methodology, Y.Z. and P.Z.; software, Y.Z. and H.C.; validation, H.C. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, P.Z.; investigation, H.C., P.Z. and Y.Z.; resources, H.C. and P.Z.; data curation, H.C. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, P.Z.; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, H.C.; project administration, H.C. and P.Z.; funding acquisition, H.C. and P.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Humanities and Social Sciences Planning Fund of the Ministry of Education (22YJAZH006 and 24YJAZH224)” and the “National Natural Science Foundation of China (51768030)”.

Data Availability Statement

The basic information and tourist data of Kumbum Monastery come from its official website (http://www.kumbum.com, accessed on 13 November 2024), and other data come from the questionnaire organized and implemented by the author, which can be obtained by contacting the author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Xiaoyang Tang, Jie Peng, Xiuzhi Wang, and Tong Xie for their contributions to the questionnaire survey, and would also like to thank Sidong Zhao and Junheng Qi for providing technical guidance for the writing of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, T.H.; Yang, N. Condition Assessment of Timber Beam in a Typical Tibetan Heritage Building Under Crowd Load. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2021, 24, 1910–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandotiya, R.; Aggarwal, A.; Sharma, I. The Paradox of Attraction: Unveiling the Dynamics of Tourist Motivation and Impact Perception at a Dark Heritage Site through Mixed-Method Approach. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2024, 36, 1015–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A. Stakeholders’ Perception Influence in Competitive Heritage Place—Making: Case Study India. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Urban Des. Plan. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.Y.; Kusumo, C.; Tan, K.K.H.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Stakeholders’ Perception on Sustainability Indicators for Urban Heritage Sites in Kuala Lumpur and George Town, Malaysia. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszkiewicz, E.; Nowakowska, A.; Adamus, J. How Valuable is Architectural Heritage? Evaluating a Monument’s Perceived Value with the Use of Spatial Order Concept. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.W.; Zhang, X.M.; Chen, X.L.; Fu, D.; Zhang, B.; Xie, X.B. Study on the Protection of the Spatial Structure and Artistic Value of the Architectural Heritage Xizi Pagoda in Hunan Province of China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.S.; Muhuri, S. Incorporating Perceptions of Multiple Stakeholders while Assessing Architectural Heritage Value: A Case of Odishan Temple Architecture in India. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2022, 44, 1431–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Jaramillo, J.; Joyanes-Díaz, M.D. Value of the Sacred: Perception and spirituality around the common concept of Architectural Heritage. Pasos-Rev. Tur. Patrim. Cult. 2020, 18, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. How Visitors Perceive Heritage Value-A Quantitative Study on Visitors’ Perceived Value and Satisfaction of Architectural Heritage through SEM. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, K.; Menassa, C.C. Modeling the Effect of Building Stakeholder Interactions on Value Perception of Sustainable Retrofits. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2015, 29, B4014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemelniece, A. Transformation of the Historical Heritage and Spatial Perception of Ilūkste. Landsc. Archit. Art 2023, 22, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurnaz, A.; Aniktar, S. Visual Perception and Contextual Relationship of Contemporary Extensions and Historical Buildings. J. Archit. Conserv. 2024, 30, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipczynska, A.; Kaczmarczyk, J.; Dziedzic, B. Effect of Indoor Green Walls on Environment Perception and Well-Being of Occupants in Office Buildings. Energies 2024, 17, 5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamoglu, E.; Yenice, T.K. Cultural Perception Performance Assessment of Adaptively Reused Heritage Buildings: Kilis Eski Hamam Case Study. ICONARP Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2022, 10, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullauri, M.D.A.; Calle, V.C.R.; Reino, P.S.H.; Garnica, E.P.G.; Iñígues, E.A.E. Heritage Context and Citizen Perception: An Approach to the Case of the Historic Center of Cuenca (Ecuador). Territorios 2024, 50, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omiecinski, T. Issues of Perception of Technical Equipment in Historical Buildings and Disturbance of Their Historical Character. Teka Kom. Urban. I Archit. 2023, 51, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrevska, B.; Mihalic, T.; Andreeski, C. Tourism Sustainability Model for a World Heritage Destination: The Case of Residents’ Perception of Ohrid. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 34, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, S.S.; Eldin, S.S. Public Perception Influence on the Reshaping Urban Heritage: A Case Study of Port Said Historic Quarters. Space Cult. 2023, 26, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.N.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, K.N.; Woo, K.S.; Zhang, N. Influencing Factors of Residents’ Perception of Responsibilities for Heritage Conservation in World Heritage Buffer Zone: A Case Study of Libo Karst. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwantiasning, A.W. Revealing the Paradox of a Heritage City Through Community Perception Approach: A Case Study of Parakan, Temanggung, Central Java, Indonesia. J. Urban Cult. Res. 2021, 23, 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, W.; Heerema, H.; Rushfeld, R.; van der Lee, I. Issues in Conservation—Three Value Moments in the Public Perception of Cultural Heritage Objects in Public Spaces. Collabra-Psychology 2021, 7, 21935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britwum, K.; Demont, M. Staging an Experience of Cultural Heritage Preservation: Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Heirloom Rice in the Philippines. Agribusiness 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Chen, J.; Ikebe, K.; Kinoshita, T.; Guarini, M.R.; Mosquera-Adell, E.; Mosquera-Perez, C.; Tapete, D. Survey of Residents of Historic Cities Willingness to Pay for a Cultural Heritage Conservation Project: The Contribution of Heritage Awareness. Land 2023, 12, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.A.; Nguyen, M.H.; Hoang, V.N.; Reynaud, A.; Simioni, M.; Wilson, C. Tourists’ preferences and willingness to pay for protecting a World Heritage site from coastal erosion in Vietnam. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 26, 27607–27628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, W.S. Effects of knowledge and perceived image on willingness-to-pay for access to world cultural heritage sites in Korea: Using the dual coding theory of learning. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetto, G.; Madau, F.A.; Carzedda, M.; Marangon, F.; Troiano, S. Social Economic Benefits of an Underground Heritage: Measuring Willingness to Pay for Karst Caves in Italy. Geoheritage 2022, 14, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Rivas, C.; Sánchez-Rivero, M. Investigating Change in the Willingness to Pay for a More Sustainable Tourist Destination in a World Heritage City. Land 2022, 11, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez-Montenegro, A.; Bedate, A.M.; Herrero, L.C.; Sanz, J.A. Inhabitants’ Willingness to Pay for Cultural Heritage: A Case Study in Valdivia, Chile, Using Contingent Valuation. J. Appl. Econ. 2012, 15, 235–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Wong, K.K.F.; Cho, M. Assessing the economic value of a world heritage site and willingness-to-pay determinants: A case of Changdeok Palace. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.Q.; Chen, P.W.; Zhang, S.N.; Chen, Y.C.; Zhao, W.W. The Impact of the Creative Performance of Agricultural Heritage Systems on Tourists’ Cultural Identity: A Dual Perspective of Knowledge Transfer and Novelty Perception. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 968820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Venturi, M.; Agnoletti, M. Agricultural Heritage Systems and Landscape Perception among Tourists. The Case of Lamole, Chianti (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, A.; Sáez-Pérez, M.P. The Industrial Heritage of Almeria. Social Perception for Tourism Use. Quiroga-Rev. De Patrim. Iberoam. 2024, 23, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockelmann, L. Impacts of Change: Analysing the Perception of Industrial Heritage in the Vogtland Region. Urban Plan. 2023, 8, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]