Automated Geographic Information System Multi-Criteria Decision Tool to Assess Urban Road Suitability for Active Mobility

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Framework

1.2. Objective and Structure of the Article

1.3. Walkability and Bikeability: Approaches and Variables

| Citation Year Study Category | Method | Spatial Unit | Variables Used in the Analysis | Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [38] 2005 Public Health | Multiple linear regression. Weight considered through variables with normalized distribution (z-score). Local perspective considered through characteristics of 357 citizens. | 1 km grid. | Road intersection, density, residential density, land-use mix. | Atlanta, United States of America |

| [33] 2007 Public Health | Additive method. Each variable reclassified into deciles to provide a standard score from 1 to 10. Local perspective considered through a survey issued to 2650 citizens. | Districts (each with approximately 250 households). | Residential density, road network connectivity, land use, net retail area. | Adelaide, Australia |

| [31] 2011 Public Health | Multicriteria spatial analysis including the evaluation of spatial autocorrelation of data using GISs. Local perspective considered through a survey issued to 733 citizens. | Street network buffers of 50 m around street center lines that extend along the network 400, 800 and 1600 m from geocoded home addresses. | Facilities density, median pedestrian route directness, density of parks, intersection density, number of cul de sacs, average speed limit, highway density, residential density, population density. | Four metropolitan cities, United States of America |

| [42] 2012 Public Health | Principal component analysis. Factor analysis used to identify index candidate variables and weights. Local perspective considered through survey data from Census of Canada, Transportation Tomorrow Survey, and the Canadian Community Health Survey. | Census tracks. | Population density, residential density, availability of walkable destinations (sum of retail stores, services, public recreation centers and schools), road network connectivity. | Toronto, Canada |

| [34] 2013 Public Health | Additive method (based on [49]). Variables’ values reclassified into deciles with a scale from 1 to 10. Walkability measure obtained with available official data. | Two Australian administrative spatial units: Collection District (CD) and State-Derived Suburb (SSC). Three road buffer walkable built environments: 500 m (5–7 min walk), 1000 m (10–12 min walk), and 1600 m (15–18 min walk). | Intersection density, dwelling density, land use, net retail area. | Adelaide, Australia |

| [39] 2014 Transportation | Sum of 12 weighted regression sub-models. Note: no statistically significant regression model was yielded for sub-model 7; thus, it was not considered. Sub-models weighted in proportion to the walker perception survey results. Sub-models: For sense of safety: 1. Pedestrian crossing affected by traffic speed; 2. Pedestrian crossing affected by facilities; 3. Walking on the sidewalk affected by nearby traffic. For sense of security (from crime): 4. Existence of others; 5. Affected by visibility at night; 6. Visual surveillance from nearby buildings. For comfort: 7. Sidewalk level of service and continuity; 8. Buffering negative environmental effects; 9. Sense of street scale and enclosure. For convenience: 10. Ease of pedestrian crossing; 11. Easy access to local stores. Visual interest: 12. Visual variety; 13. Visual attractiveness. | Road segment or route (combination of segments). | Age, pedestrian crossing coverage rate, average number of through-traffic lanes, commercial use of adjacent buildings, average ground-level luminosity, existence of on-street parking, average width of buffer zone, percentage of walking-conducive commercial areas, average building width, residential use of adjacent buildings, gender, average number of upper-level windows/500 ft, average building height, existence of sidewalk, street enclosure index II (3.3), average pedestrian-level façade transparency, type of on-street parking, percentage of first-floor residential uses, fence coverage rate, percentage of sidewalk faced with building façades, type of sidewalk pavement, average number of street trees/500 ft. | California, United States of America (in a station area) |

| [23] 2014 Public Health | Multicriteria analysis with additive method. Aggregation of the standardized variables with double weighting for the connectivity index. Local perspective considered through the geo-referenced household survey data collected by Verband Region Sttuttgard (regional authority). | Sub-districts (each with approximately 500 households). | Connectivity index or intersection index, Shannon’s entropy index (level of mixed land use), floor area ratio (intensity of shopping opportunities), household density index. | Stuttgart, Germany |

| [22] 2014 Public Health | Additive method. Variables equally weighted. Local perspective considered through survey data collected by Canada census, Statistics Canada, DMTI Spatial Inc. Enhanced Points of Interest, City of Toronto, and the Ministry of Education. | 800 m geographic buffers around dissemination blocks’ residentially weighted centroids. Dissemination block is the smallest geographic unit for which census population and dwelling data are available. | Population density, residential density, availability of walkable destinations (sum of all retail, service, and recreation centers, and school destinations), street connectivity. | Toronto, Canada |

| [35] 2016 Public Health | Additive method (based on [49]). Variables’ values reclassified into deciles with a scale from 1 to 10. Three walkability models were developed for each spatial unit, differing in the land uses included in the analysis. Walkability measure obtained from Census and Whitehall II Study sample data (sample size of 10,308). | Three spatial units of contiguous administrative areas: 21,140 output areas, 633 census area statistics, and 33 local authorities. | Residential dwelling density, street connectivity, land-use mix. | London, United Kingdom |

| [40] 2018 Transportation | Linear regression analysis. Weight considered through variables normalized distribution (z-score). Individual models by trip purpose: job, educational, shopping, and all trips. Information about the Rasht Household Travel Survey—RHTS—was used. Local perspective considered through a survey that was randomly distributed among more than 5000 households. | 112 Traffic Analysis Zones—TAZs (defined by the Rasht Household Travel Survey—RHTS). | 21 street design variables, 4 diversity indices (entropy, Herfindal–Hershman index, mixed-use index, job–population balance), population density, destination accessibility indices (aerial distance to Central Business District (CBD) and network distance to CBD). Criteria studied for the trip share: job, educational, shopping, and all trips. | Rasht, Iran |

| [36] 2018 Public Health | Additive method. Weight considered through the normalized distribution of variables (z-score). Local information obtained from census data. | Census tracts (neighborhoods). | Residential density, street connectivity, destination-based entropy index. | Porto, Portugal |

| [37] 2019 Public Health | Additive method. Variables’ weights defined based on the results of surveys conducted with 66 experts. The sum of the weights equals 1. Official open access data provided by Madrid City Council (National Institute of Statistics, Municipal Cartography, National Land Registry, General Directorate of Sustainability and Environmental Control and Municipal Register) | Sections of the sidewalk. | Population density, diversity of business activities, connectivity, noise, sun/shade. | Madrid, Spain |

| [25] 2021 Transportation | Spatial multicriteria analysis with weighted linear method. Variables’ weights defined based on the opinion of 15 urban mobility experts and local authorities. Sub-variables’ weights defined by the stated preferences of 275 citizens (survey). | Road segment. | Population density, location, and attractiveness (service areas) of the main trip-generation points, road hierarchy, slope, and cross-section geometry. | Covilhã, Portugal |

| [41] 2023 Transportation | Multiple linear regression. (based on [38]) Weight considered through the normalized distribution of variables (z-score). Double weighting for the intersection density variable. Walkability measure obtained with available official data. | 100 m grid. | Geometrical characteristics of sidewalks (length and slope), intersection density, Shannon’s entropy index (level of mixed land use), floor area ratio index (FAR—ratio of commercial building area to total commercial land use area) and household density. | Seoul, Republic of Korea |

| Citation Year Study Category | Method | Spatial Unit | Variables Used in the Analysis | Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] 1998 Transportation | Weighted regression. | Road segment. | Presence of a bicycle lane or paved shoulder, bicycle lane or paved shoulder width, curb lane width, curb lane volume, other lane(s) volume, 85th percentile speed of traffic, presence of a parking lane, type of roadside development (residential or other type), combined adjustment factor for truck volumes, parking turnover, right-turn volumes. | Olympia, Austin, and Chapel Hill, United States of America |

| [44] 2013 Transportation | Weighted regression. Variables’ weights defined using a multilevel logistic regression. Variables’ information obtained from surveys, focus groups, and expert knowledge of local users (914 participants). | 50 m grid. | Infrastructure factor, topographical factor, security factor, environmental factor. | Cali, Colombia |

| [45] 2015 Transportation | Additive method. Variables’ values reclassified into deciles with a scale from 1 to 10. Variables’ information from 278 bike trips was used in the study. | 100 m grid. | Cycling infrastructure, presence of separated bicycle pathways, main roads without any parallel bicycle infrastructure, green and aquatic areas, topography, land use. | Graz, Austria |

| [32] 2017 Transportation | Spatial analysis. Factor analysis used to perform the variables’ weight distribution. Local perspective considered through a survey issued to 231 citizens. | 10 m grid. | Residencial density, mixed land use, topography, safety, types of infrastructure. | Curitiba, Brazil |

| [43] 2020 Urban Planning | Additive method. Based on Copenhagenize Index. Variables’ values rated with a scale from 1 to 4. Local perspective considered through a survey issued to 406 city center citizens. | City. | Advocacy, bicycle culture, bicycle facilities, bicycle infrastructure, bike-sharing programs, gender split, modal share for bicycles, modal share increase since 2006, safety perception, politics, social acceptance, urban planning, traffic calming, bonus points (awarded for particularly impressive efforts/results towards re-establishing the bicycle as a feasible, acceptable, and practical form of transport). | Shanghai, China |

| [26] 2020 Transportation | Weighted additive function. Discrete choice model used to estimate variable weights based on users’ perception results from ranking surveys issued to 336 bicycle users. | Road segment. | Directness and coherence, comfort and attractiveness, traffic safety, security, climate, presence of bicycle infrastructure, cost of the trip. | Barranquilla, Colombia |

| [27] 2020 Transportation | Additive method with spatial analysis. Four sub-indices are considered: accessibility, suitability, perceptibility, prevailing air quality in the vicinity of cycling routes. Variables’ weights: air quality evaluated by varying weight from 0% to 12.5% to 25%, and all other three sub-indices with the same weights of 33.3%, 29.2%, and 25%. | Road segment. | For accessibility—points of interest (POI): leisure, transport, commercial, daily routine. For suitability: slope, sinuosity, bike route. For perceptibility: greenery, crowdedness, outdoor enclosure. For air quality: PM2.5 (particulate matter), BC (black carbon). | Singapore |

| [28] 2021 Transportation | Weighted overlay of linear criteria in GIS. Weights of 50% for bicycle infrastructure, 25% for speed limit, and 25% for bicycle parking (variables rated with a scale from 1 to 10). Variables’ weights defined based on interviews conducted with active local cyclists. | Road segment and intersection. | Existence and type of bike path, speed limit, parking facilities for bicycles, quality of intersection infrastructure for bicycles. | Munich, Germany |

| [29] 2022 Transportation | Spatial multicriteria analysis with weighted linear method. Variables’ weights defined based on the opinion of eight urban mobility experts and local authorities. Sub-criterion’s weight defined from the citizens’ stated preferences survey issued to 92 participants. | Road segment. | Population density, service areas of trip-generation points, road hierarchy, slope and cross-section geometry, type of bicycle (conventional and electric). | Covilhã, Portugal |

| [47] 2023 Transportation | Additive method. Combination of 13 variables that translate four subindices: safety, comfort, accessibility, and vitality. Variables’ weight defined using principal component analysis (PCA). Use of spatio-temporal open-source big data from Digital China Innovation Contest 2021, Geospatial Data Cloud, China Unicom, Baidu Map, Ecology and Environment Agency, European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, and Copernicus. | Road segment. | Safety variables: wind speed, road slope, precipitation. Comfort variables: temperature, sky view index, green view index, trajectory sinuosity, air pollution. Accessibility variables: average speed of trajectory, public transportation accessibility, commercial accessibility. Vitality variables: number of trajectories, crowdedness. | Xiamen, China |

| [48] 2024 Transportation | Additive method. Indicator selection and model parametrization performed by iterative refinement and adjustment based on the scientific literature, knowledge of local experts in planning, and user feedback. Variables’ value within 0–1 with weighted average computed across all indicators. For steep gravel segments, an increased weight for slope and surface was considered. Use of open and globally available data sets. | Road segment. | Road category, bicycle infrastructure, maximum speed, gradient, type of pavement, designated bicycle route. | Salzburg, Austria Wuppertal, Germany |

1.4. Process Automation with ArcGIS Model Builder

2. Method

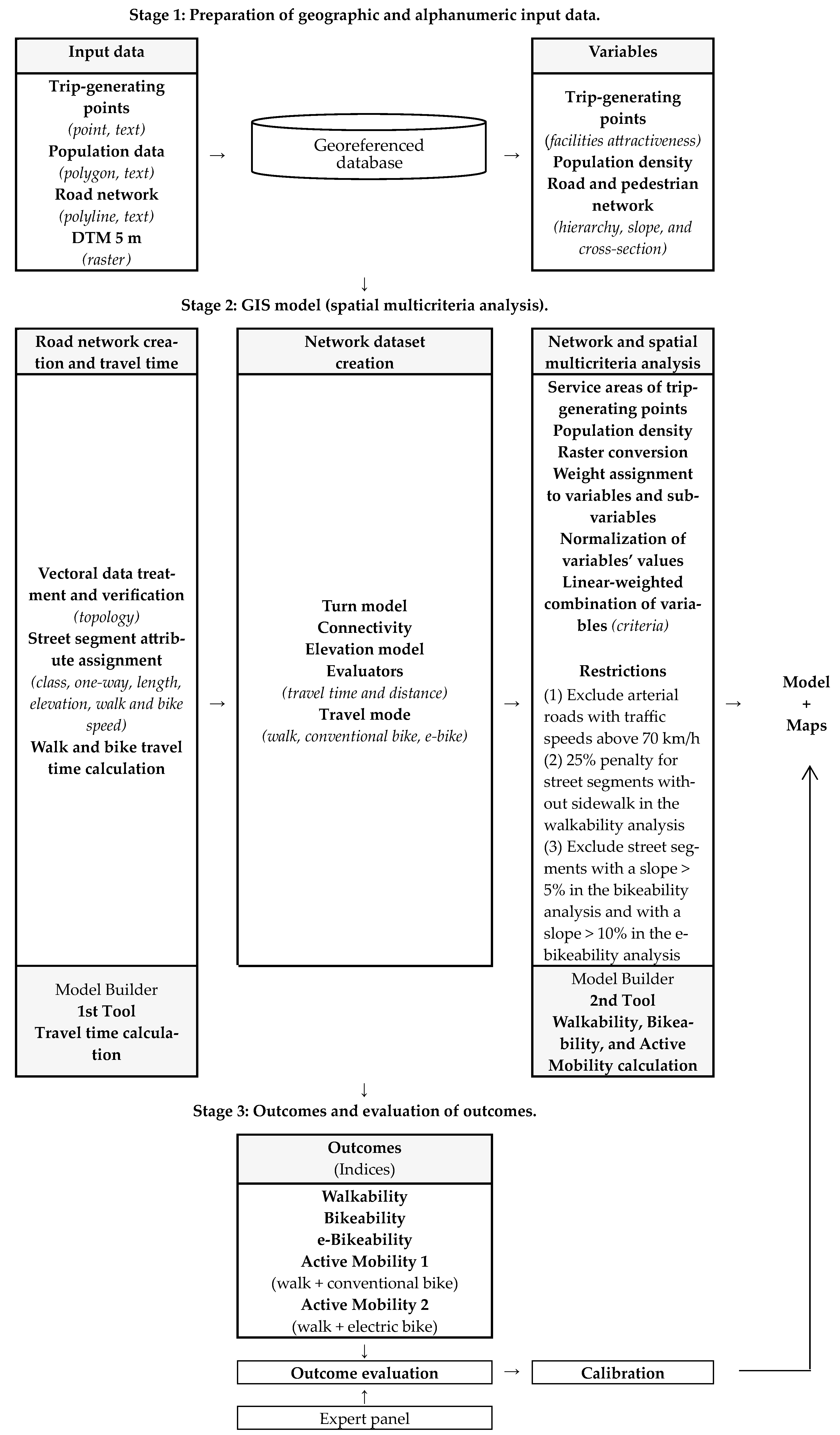

2.1. Stage 1: Preparation of Geographic and Alphanumeric Input Data

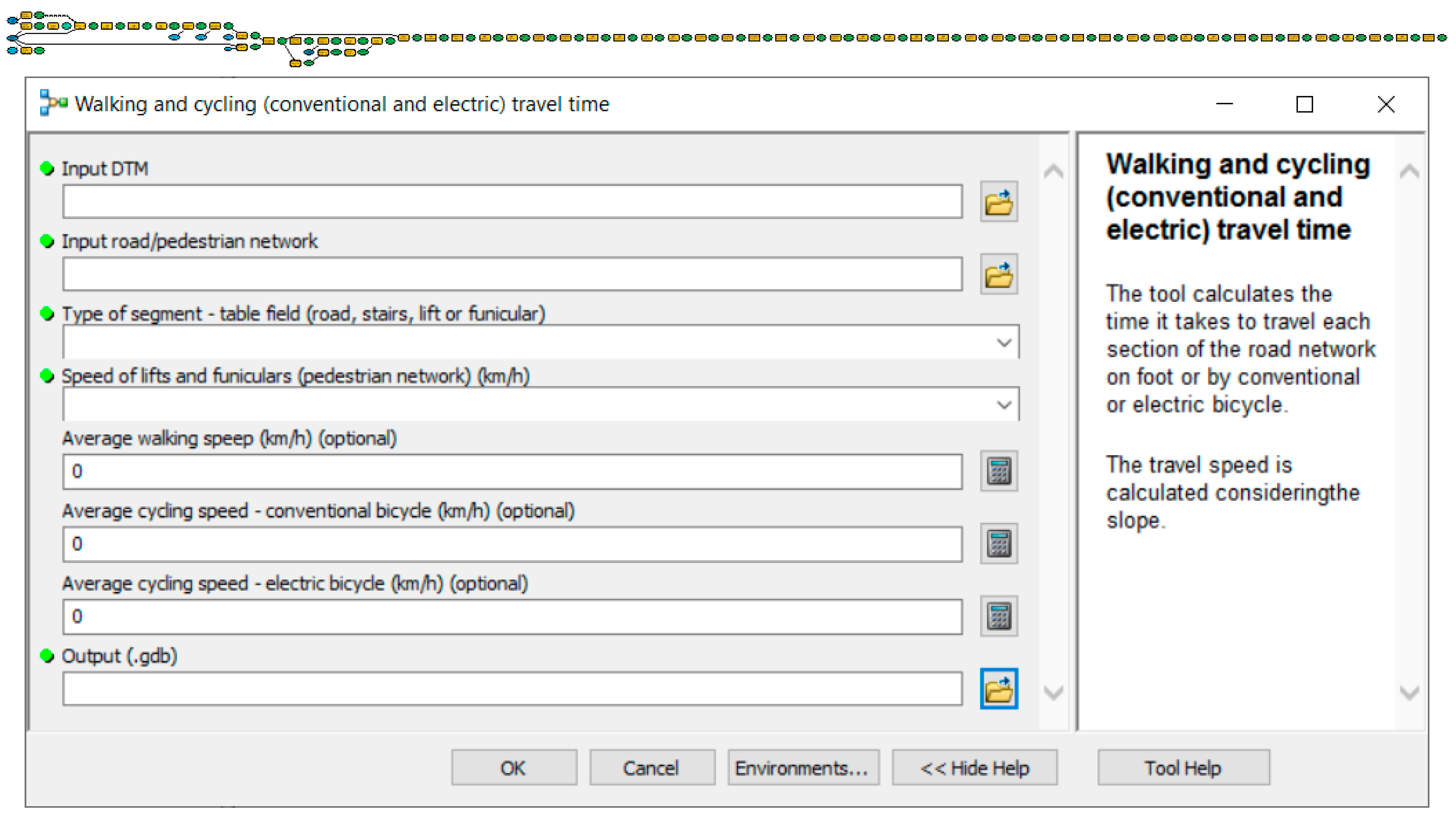

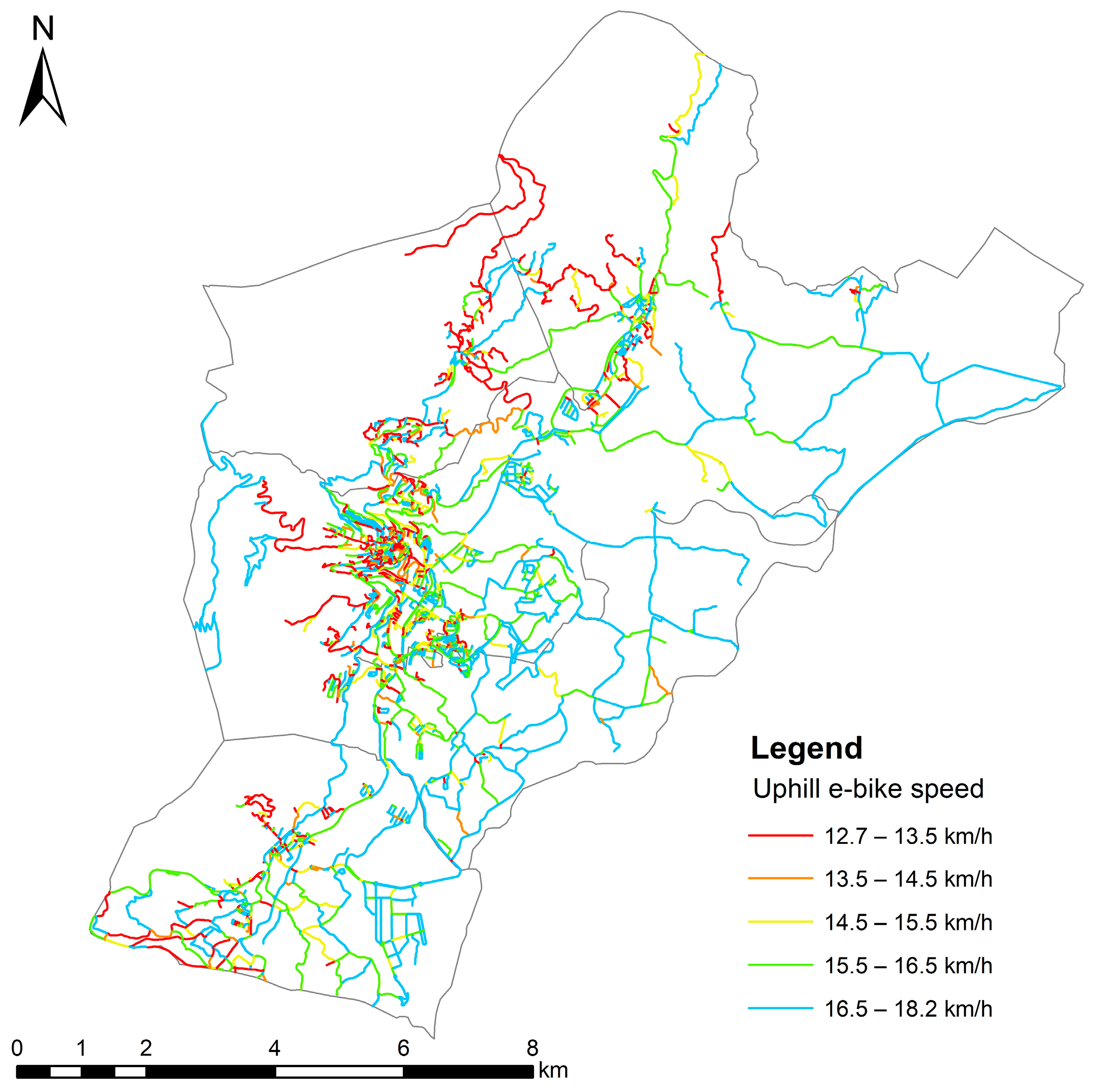

2.2. Stage 2: GIS Model (Spatial Multicriteria Analysis)

- where

- Tm is the travel time of the mode m in minutes;

- m is equal to w for walking, bc for conventional cycling, and be for electric cycling;

- Vm is the speed of mode m in km/h;

- L is the street segment length in km;

- dh is the elevation difference between the start and the end point of the street segment in meters;

- dx is the street segment length in meters;

- S is the street segment slope (decimal value);

- θ is the angle of the slope.

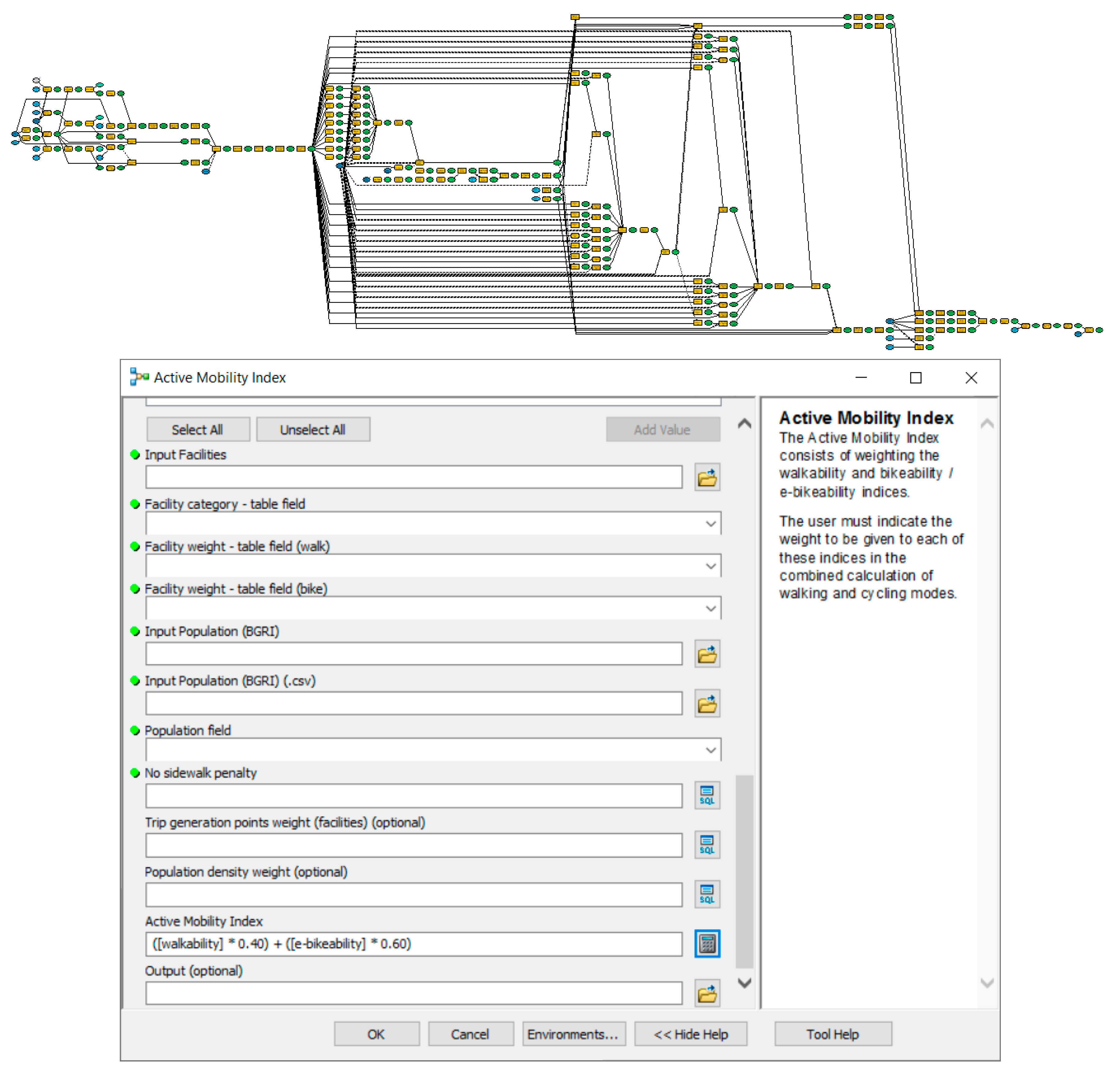

- The walkability index, which refers to the attractiveness and suitability of an urban area for walking.

- Two bikeability indices (for conventional and electric bikes), which reflect the comfort, safety, attractiveness, and suitability of an urban area for cycling.

- Two combinations of the previous: the Active Mobility 1 (walking and conventional cycling) and Active Mobility 2 (walking and e-cycling) indices.

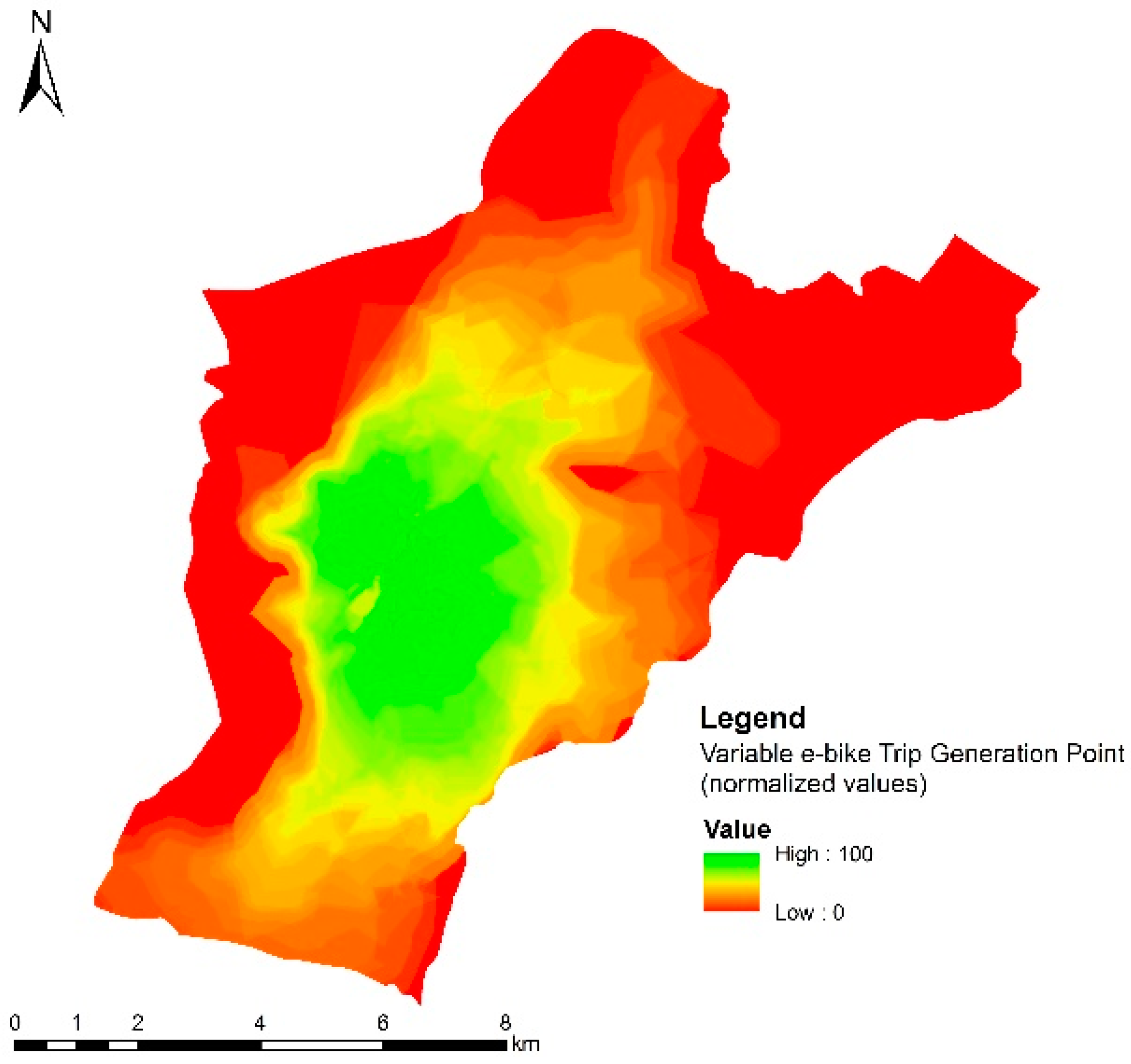

- TGPm is the value of the trip-generation point variable for mode m (w for walkability, bc for conventional bike, and be for electric bike) (pixel, not normalized);

- n is the number of sub-variables (number of facility categories, such as health, educational, services, etc.);

- j is the score assigned to the service areas, and it represents the level of demand for walking or cycling (defined as a function of travel time, 0–100);

- wn is the n sub-variable’s weight (defined from the inhabitants’ stated preferences survey, 0–1);

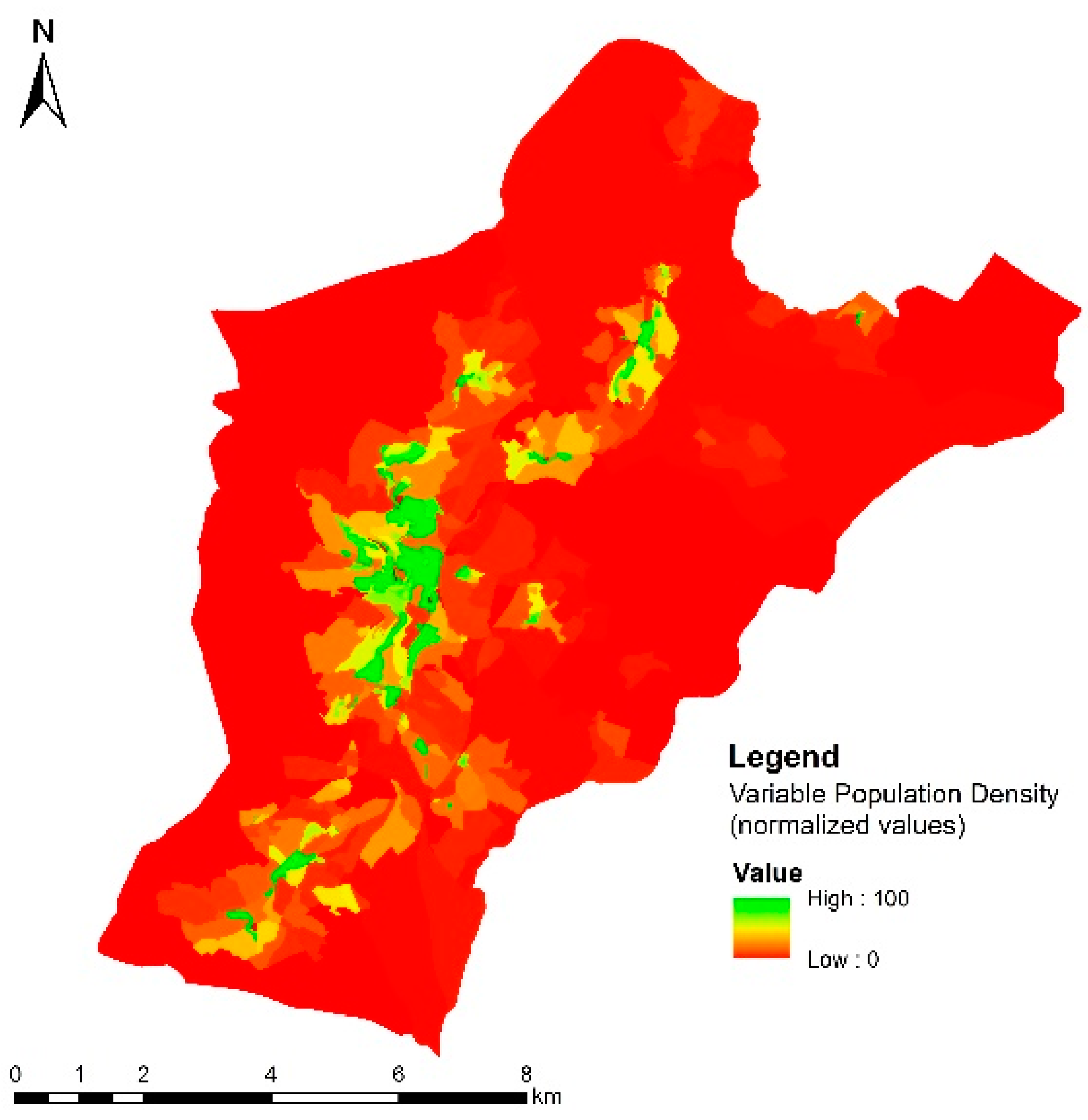

- PD is the value of the population density variable in inhabitants/ha or inhabitants/km2 (pixel, not normalized);

- RP is the resident population of a considered urban area (pixel, inhabitants);

- A is the urban area under study in ha or km2; the A unit should be chosen according to the administrative territory division dimension that is considered (for example, neighbourhoods (ha) or parishes (km2));

- Pm_nor_i is the normalized pixel value for TGPm_nor or PDnor (0–100);

- Pi is the not-normalized pixel value for TGPm or PD;

- Pmin and Pmax are the variable (pixel) minimum and maximum values (not normalized);

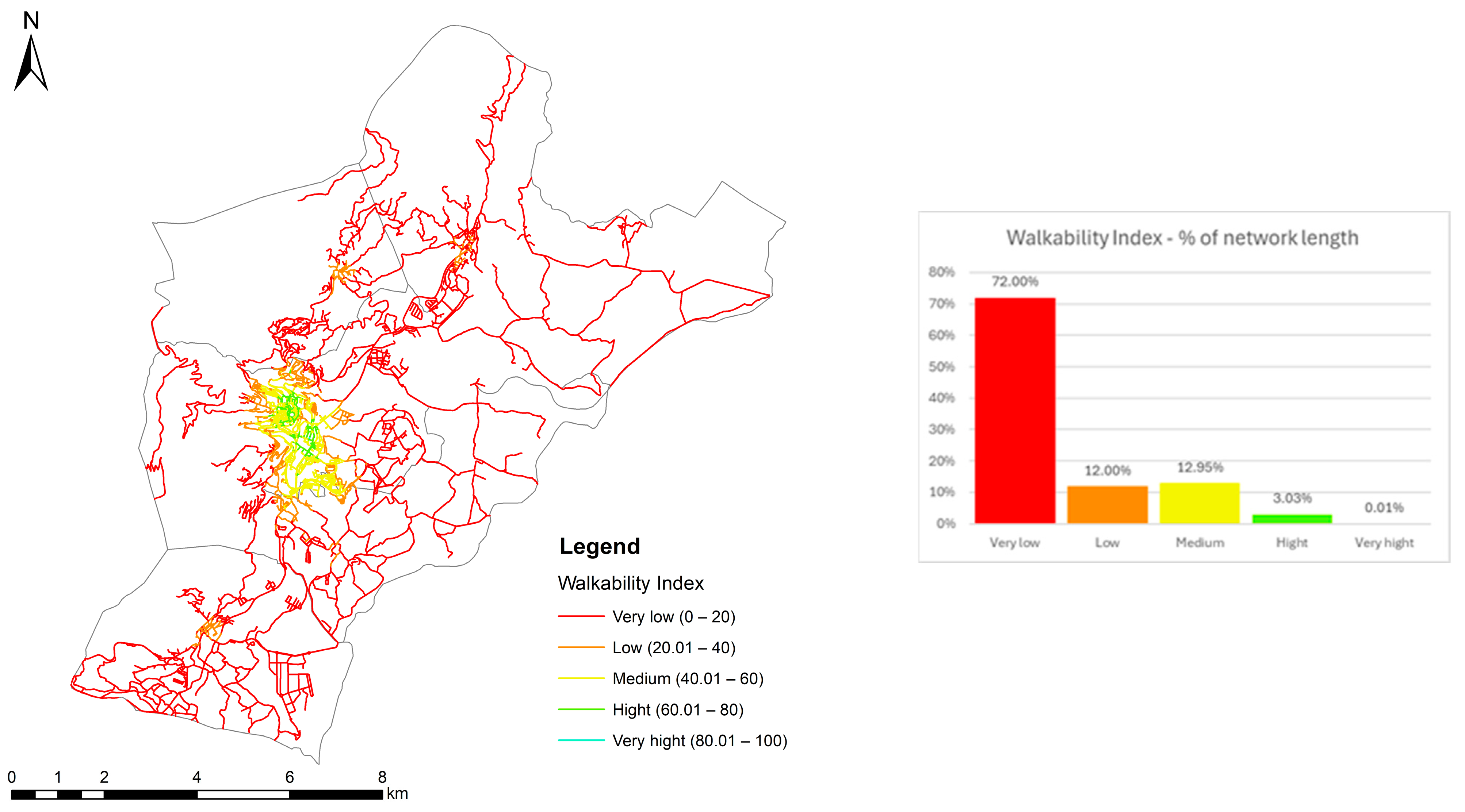

- Ii_m is the network suitability index for pixel i on a 0–100 scale by transport mode m (very high: 80 < Ii_m ≤ 100; high: 60 < Ii_m ≤ 80; medium: 40 < Ii_m ≤ 60; low: 20 < Ii_m ≤ 40; and very low: 0 < Ii_m ≤ 20 suitability);

- pTGP and pPD are the weights assigned to the trip-generation points and to the population density variable, defined by a panel of experts (0–1);

- TGPnor is the value of the trip-generation point variable (pixel, normalized, 0–100);

- PDnor is the value of the population density variable (pixel, normalized, 0–100);

- NSi is the value of the road network characteristics variable for street segment i (0 for segments not adequate for walking or cycling, 0.75 for segments without a sidewalk that are adequate for walking, 1 for segments with a sidewalk that are adequate for walking, and 1 for segments adequate for cycling);

- IAM_1 is the active mobility index, which is determined considering the walk and conventional bike modes on a 0-100 scale (very high: 80 < Ii_m ≤ 100; high: 60 < Ii_m ≤ 80; medium: 40 < Ii_m ≤ 60; low: 20 < Ii_m ≤ 40; and very low: 0 < Ii_m ≤ 20 suitability);

- pw, pbc, and pbe are the weights to be assigned to the contribution of each mode to active mobility suitability, being defined by the panel of transportation experts and local authorities (0–1);

- IAM_2 is the active mobility index, which is determined considering the walk and electric bike modes.

2.3. Stage 3: Outcomes and Their Evaluation

2.4. Automation of the Spatial Analysis Model in GIS

3. Case Study

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dekoster, J.; Schollaert, U. Cidades Para Bicicletas, Cidades de Futuro; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2000. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- IMTT. Guia Para a Elaboração de Planos de Mobilidade e Transportes. 2011. Available online: https://www.imt-ip.pt/sites/IMTT/Portugues/Planeamento/DocumentosdeReferencia/PacotedaMobilidade/Documents/Pacote%20da%20Mobilidade/Guia%20PMT_Mar%C3%A7o_2011.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2020). (In Portuguese).

- European Commission. New EU Urban Mobility Framework—Commission Communication. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transport/themes/urban/urban_mobility_en (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Southworth, M. Designing the Walkable City. J. Urban. Plan. Dev. 2005, 131, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, D. The city and the bicycle: An analitycal reading. Finisterra 2016, 51, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paglione, L.; Donato, M.; Cofone, L.; Sabato, M.; Appolloni, L.; D’Alessandro, D. The Healthy City Reimagined: Walkability, Active Mobility, and the Challenges of Measurement and Evaluation. Urban. Sci. 2024, 8, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enab, D.; Zawawi, Z.; Qanazi, S.; Shahrour, I. Socio-Spatial Analysis of Schools Based on Neighborhood Planning of the 15-min City. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Transport in the European Union Current Trends and Issues; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/new-eu-transport-report-current-trends-and-issues-2024-06-27_en (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- European Platform of Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans. Guidelines for Developing and Implementing a Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan, Germany. 2021. Available online: https://urban-mobility-observatory.transport.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2023-09/sump_guidelines_2019_second%20edition.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions—Together Towards Competitive and Resource-Efficient Urban Mobility; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52013DC0913 (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- European Commission. A European Strategy for Low-Emission Mobility; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_16_2497 (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. Paris Declaration: City in Motion, People First; UNECE: New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/792596 (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Urban Agenda for the EU. Partnership for Urban Mobility Final Action Plan. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/2018-11-14_pum_final_action_plan.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Duany, A.; Steuteville, R. Defining the 15-Minute City, Public Square, A CNU Journal. Available online: https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2021/02/08/defining-15-minute-city (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Caetano, L. A Cidade de 15 Minutos, W2G Consultoria e Investigação em Mobilidade e Transportes (in Portuguese). 2021. Available online: https://www.w2g.pt/2020/08/a-cidade-de-15-minutos-747/ (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- IMTT. Diretrizes Nacionais para a Mobilidade. 2012. Available online: https://www.imt-ip.pt/sites/IMTT/Portugues/Planeamento/DocumentosdeReferencia/PacotedaMobilidade/Documents/Pacote%20da%20Mobilidade/Directrizes_vposconsultapublica_abril2012.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2020). (In Portuguese).

- Fundo para o Serviço Público de Transportes. Apoio à Aquisição e Instalação de Equipamentos Destinados ao Estacionamento de Bicicletas; Fundo para o Serviço Público de Transportes: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Diário da República n.º 253/2021; Série, I. Lei n.º 98/2021—Lei de Bases do Clima. Assembleia da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. (In Portuguese)

- Diário da República n.º 45/2021; Série II. Despacho n.º 2535/2021—Regulamento de Atribuição do Incentivo Pela Introdução no Consumo de Veículos de Baixas Emissões. Assembleia da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. (In Portuguese)

- Diário da República n.º 147/2019; Série, I. Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.º 131/2019—Estratégia Nacional para a Mobilidade Ativa Ciclável 2020–2030. Assembleia da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. (In Portuguese)

- ZERO. ZERO Quer Verdadeiros Planos de Mobilidade Urbana Sustentável. 2020. Available online: https://zero.ong/noticias/zero-quer-verdadeiros-planos-de-mobilidade-urbana-sustentavel-pmus-obrigatorios/ (accessed on 19 December 2023). (In Portuguese).

- Glazier, R.; Creatore, M.; Weyman, J.; Fazli, G.; Matheson, F.; Gozdyra, P.; Moineddin, R.; Shriqui, V.; Booth, G. Density, destinations or both? A comparison of measures of walkability in relation to transportation behaviors, obesity and diabetes in Toronto, Canada. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyer, M.; Fina, S.; Siedentop, S.; Schlicht, W. Walkability is only part of the story: Walking for transportation in Stuttgart, Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 5849–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschinsky, J.; Talen, E.; Alfonzo, M.; Lee, S. How walkable is Walker’s paradise? Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2017, 44, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, A.; Santos, B.; Gonçalves, J.; Kempa, J.; Chmielewski, J. Transportation Network Spatial Analysis to Measure Pedestrian Suitability. The Case of Hilly Cities. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1203, 022107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellana, J.; Saltarín, M.; Larrañaga, A.; González, V.; Henao, C. Developing an urban bikeability index for different types of cyclists as a tool to prioritise bicycle infrastructure investments. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 139, 310–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, P.; Zhao, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Minet, L.; Nguyen, T.; Balasubramanian, R. Cyclists’ personal exposure to traffic-related air pollution and its influence on bikeability. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2020, 88, 102563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Querg, J.; Keler, A.; Grigoropoulos, G. The munich bikeability index: A practical approach for measuring urban bikeability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B.; Passos, S.; Gonçalves, J.; Matias, I. Spatial Multi-Criteria Analysis for Road Segment Cycling Suitability Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J. GIS-based multicriteria decision analysis: A survey of the literature. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2006, 20, 703–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, D.; Aldstadt, J.; Whalen, J.; Melly, S.; Gortmaker, S. Validation of Walk Score® for estimating neighborhood walkability: An analysis of four US metropolitan areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2011, 8, 4160–4179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, B. A Bikeability Index for Curitiba (Brazil). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Twente: Twente, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, N.; Cerin, E.; Leslie, E.; duToit, L.; Coffee, N.; Frank, L.; Bauman, A.; Hugo, G.; Saelens, B.; Sallis, J. Neighborhood Walkability and the Walking Behavior of Australian Adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coffee, N.; Howard, N.; Paquet, C.; Hugo, G.; Daniel, M. Is walkability associated with a lower cardiometabolic risk? Health Place. 2013, 21, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockton, J.C.; Duke-Williams, O.; Stamatakis, E.; Mindell, J.S.; Brunner, E.J.; Shelton, N.J. Development of a novel walkability index for London, United Kingdom: Cross-sectional application to the Whitehall II Study. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Hoffimann, E. Development of a neighbourhood walkability index for Porto metropolitan area. How strongly is walkability associated with walking for transport? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shammas, T.; Escobar, F. Comfort and time-based walkability index design: A GIS-based proposal. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.; Schmid, T.; Sallis, J.; Chapman, J.; Saelens, B. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: Findings from SMARTRAQ. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Deakin, E.; Lee, J. Perception-based walkability index to test impact of microlevel walkability on sustainable mode choice decisions. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2464, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibian, M.; Hosseinzadeh, A. Walkability index across trip purposes. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 42, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.; Choi, M.; Kwak, J.; Ku, D.; Lee, S. A comprehensive walkability evaluation system for promoting environmental benefits. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier, R.; Weyman, J.; Creatore, M.; Gozdyra, P.; Moineddin, R.; Matheson, F.; Dunn, J.; Booth, G. Development and Validation of an Urban Walkability Index for Toronto, Canada, Toronto, Canada. 2012. Available online: https://www.torontohealthprofiles.ca/a_documents/aboutTheData/12_2_AboutTheData_Walkability_WKB_2006-2008.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Leslie, E.; Coffee, N.; Frank, L.; Owen, N.; Bauman, A.; Hugo, G. Walkability of local communities: Using geographic information systems to objectively assess relevant environmental attributes. Health Place 2007, 13, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostensen, A. The Bicycle Compatibility Index: A level of Service Concept, Implementation Manual (FHWA-RD-98-095), USA. 1998. Available online: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/tools/docs/bci.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Urrego, N.; Páez, D.; Guzmán, V. Cali Bikeability Index Map: A Tool for Evaluating Public Investment and Future Needs, Engineering Department, Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia. 2014. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1992/19831 (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Krenn, P.; Oja, P.; Titze, S. Development of a Bikeability Index to Assess the Bicycle-Friendliness of Urban Environments. Open J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 5, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, A.; Xu, L. On the Applicability of a Western Bikeability Index in the Chinese Context. Int. Rev. Spat. Plan. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 8, 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Chen, Z.; Lei, J. Assessing spatiotemporal bikeability using multi-source geospatial big data: A case study of Xiamen, China. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 125, 103539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Van der Meer, L.; Kaziyeva, D.; Stutz, P.; Wendel, R.; Loidl, M. Bikeability of road segments: An open, adjustable and extendible model. J. Cycl. Micromobility Res. 2024, 2, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI. Use ModelBuilder. Available online: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/latest/help/analysis/geoprocessing/modelbuilder/modelbuilder-quick-tour.htm (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Leite, M.; Ferreira, J. Application of GIS in Public Transportation. In Proceedings of the 7th VCT (Virtual Cities and Territories), Lisboa, Portugal, 11–13 October 2011; pp. 439–446. Available online: https://e-geo.fcsh.unl.pt/sites/default/files/dl/artigos/JF_Paper_Ferreira_Jorge&Leite_Ines_FinalVersion.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- King, G. A Spatial Framework Supports Road Investment Decisions, Esri. 2016. Available online: https://www.esri.com/about/newsroom/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/a-spatial-framework-supports-road-investment-decisions.pdf?srsltid=AfmBOoplyhjBwA0OCzQE86h2sRXLeQj9r8-hbgDdIp4YPkRyQkE-IUwr (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Perera, P.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Electric vehicle recharging infrastructure planning and management in urban communities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, B.; Nielsen, P. Analysing transport costs of Danish forest wood chip resources by means of continuous cost surfaces. Biomass Bioenergy 2007, 31, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenson, I.; Martens, K.; Rofé, Y. Measuring the gap between car and transit accessibility: Estimating access using a high-resolution transit network geographic information system. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2144, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, E.; Carpentieri, G.; Guida, C. Measuring walking accessibility to public transport of the elderly: The case of Naples. J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2018, 17, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Tseng, M. Evaluating disparities in elderly community care resources: Using a geographic accessibility and inequality index. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolny, A.; Ogryzek, M.; Źróbek, R. Towards sustainable development and preventing exclusions-determining road accessibility at the sub-regional and local level in rural areas of Poland. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadi, P.; Murad, A. Modelling sustainable urban transport performance in the Jakarta city Region: A GIS approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, Y. Effect of terrain relief on the transport cost on road of biomass raw materials: Energy conservation study of 9 cities and counties in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 274, 111212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irtenkauf, E. Analyzing Tobler’s Hiking Function and Naismith’s Rule Using Crowd-Sourced GPS Data. Pennsylvania State University, USA. 2014. Available online: https://handbook.geospatial.psu.edu/sites/default/files/capstone/Irtenkauf_596B_20140430.docx (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Fruin, G.; Strakosch, J. Pedestrian, Planning and Design; Elevator World: Mobile, AL, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Flügel, S.; Hulleberg, N.; Fyhri, A.; Weber, C.; Ævarsson, G. Empirical speed models for cycling in the Oslo road network. Transportation 2019, 46, 1395–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation Year | Study | Case Study | Model Builder Function | Network Analyst Extension Use | Model Builder Tool-Based |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [54] 2007 | Cost map for woody biomass transport | Denmark | Intermediate processes | No | No |

| [55] 2010 | Transit- and car-based accessibility | Tel Aviv, Israel | Model | Yes | Yes |

| [51] 2011 | Supply and demand for public transport | Almada, Portugal | Model | Yes | No |

| [52] 2016 | Economic impacts of unplanned road closures | Queensland, Australia | Model | Yes | No |

| [56] 2018 | Walking accessibility to public transport | Naples, Italy | Intermediate processes | Yes | No |

| [57] 2018 | Elderly community center accessibility | Taiwan | Model | Yes | No |

| [58] 2019 | Road accessibility in rural areas | Warmia and Mazury, Poland | Intermediate processes | Yes | No |

| [37] 2019 | Walkability index | Madrid, Spain | Intermediate processes | No | No |

| [59] 2019 | Sustainable urban transport performance | Jakarta, Indonesia | Intermediate processes | No | No |

| [53] 2020 | Planning and management of vehicle recharging infrastructure | Kelowna, Canada | Model | Yes | No |

| [60] 2020 | Effect of terrain relief on transport cost | 9 Chinese cities | Intermediate processes | No | No |

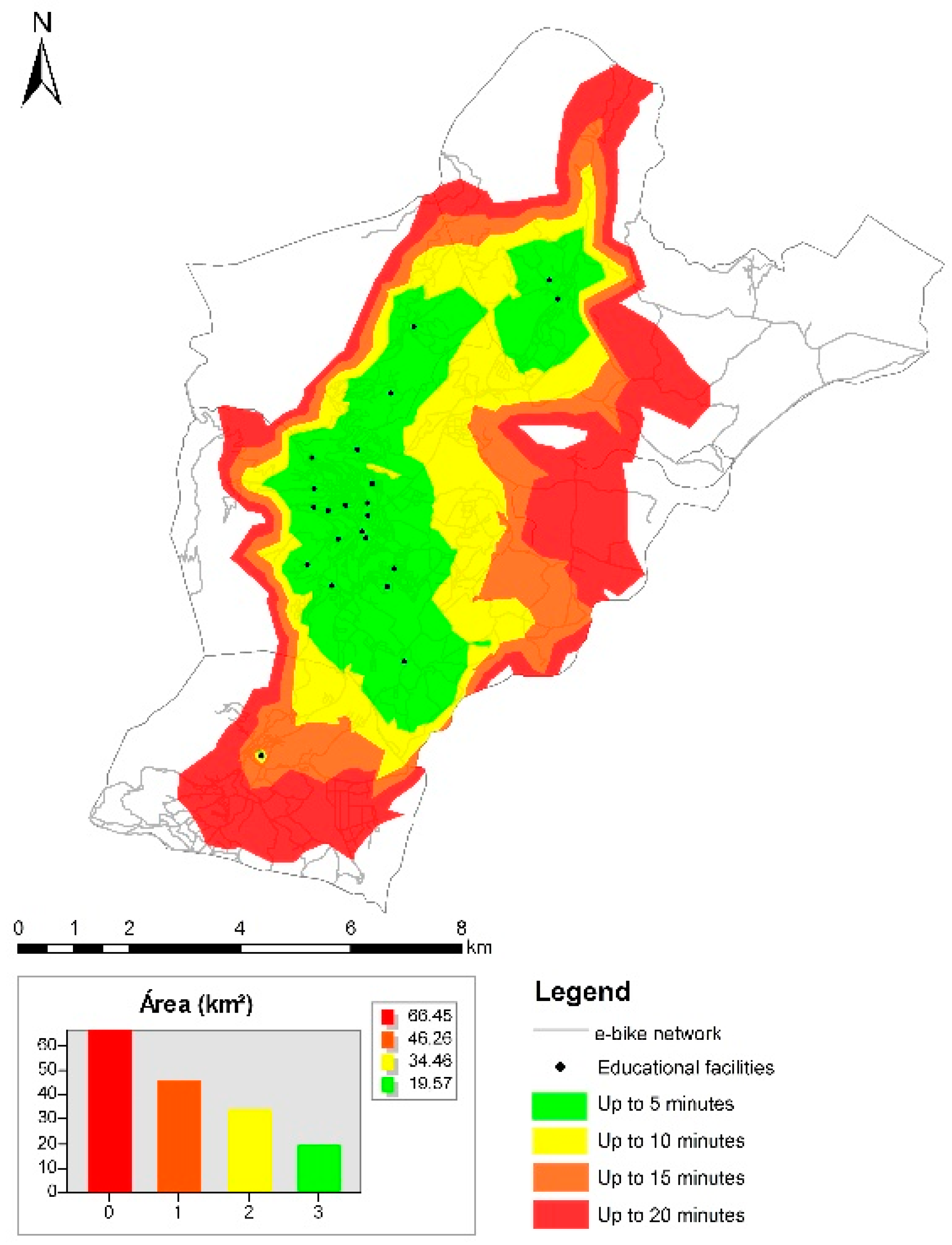

| Trip-Generation Point Service Areas | Trip-Generation Point Sub-Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Travel Time (Minutes) | Score (0–100) | Facility Category | Weight for Walk Mode | |

| Weight for Walk Mode [25] | Weight for Bike Mode (Conventional and Electric) [29] | |||

| 0–5 | 100 | Transportation | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| 5–10 | 75 | Health | 0.68 | 0.70 |

| 10–15 | 50 | Educational | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| 15–20 | 25 | Services | 0.62 | 0.68 |

| +20 | 1 | Commercial | 0.63 | 0.71 |

| Tourism | 0.60 | 0.80 | ||

| Culture | 0.54 | 0.73 | ||

| Recreation | 0.65 | 0.82 | ||

| Sport | 0.58 | 0.78 | ||

| Suitability | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index | Network Length | Not Suitable | Very Low | Low | Reasonable | High | Very High |

| Walkability | km | 0 | 286.95 | 47.84 | 51.62 | 12.06 | 0.06 |

| % | 0 | 72.00 | 12.00 | 12.95 | 3.03 | 0.01 | |

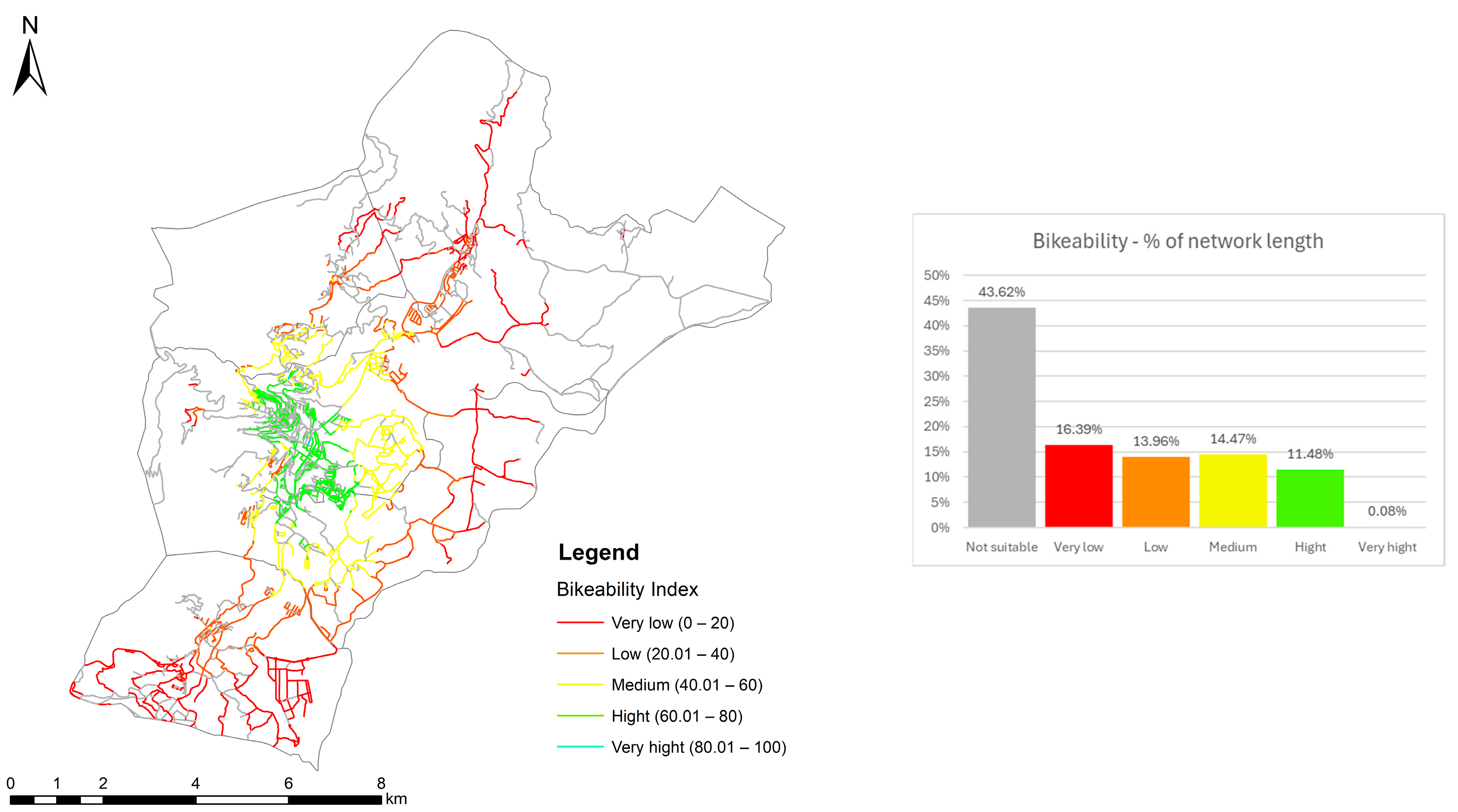

| Bikeability | km | 173.10 | 65.02 | 55.38 | 57.42 | 45.54 | 0.32 |

| % | 43.62 | 16.39 | 13.96 | 14.47 | 11.48 | 0.08 | |

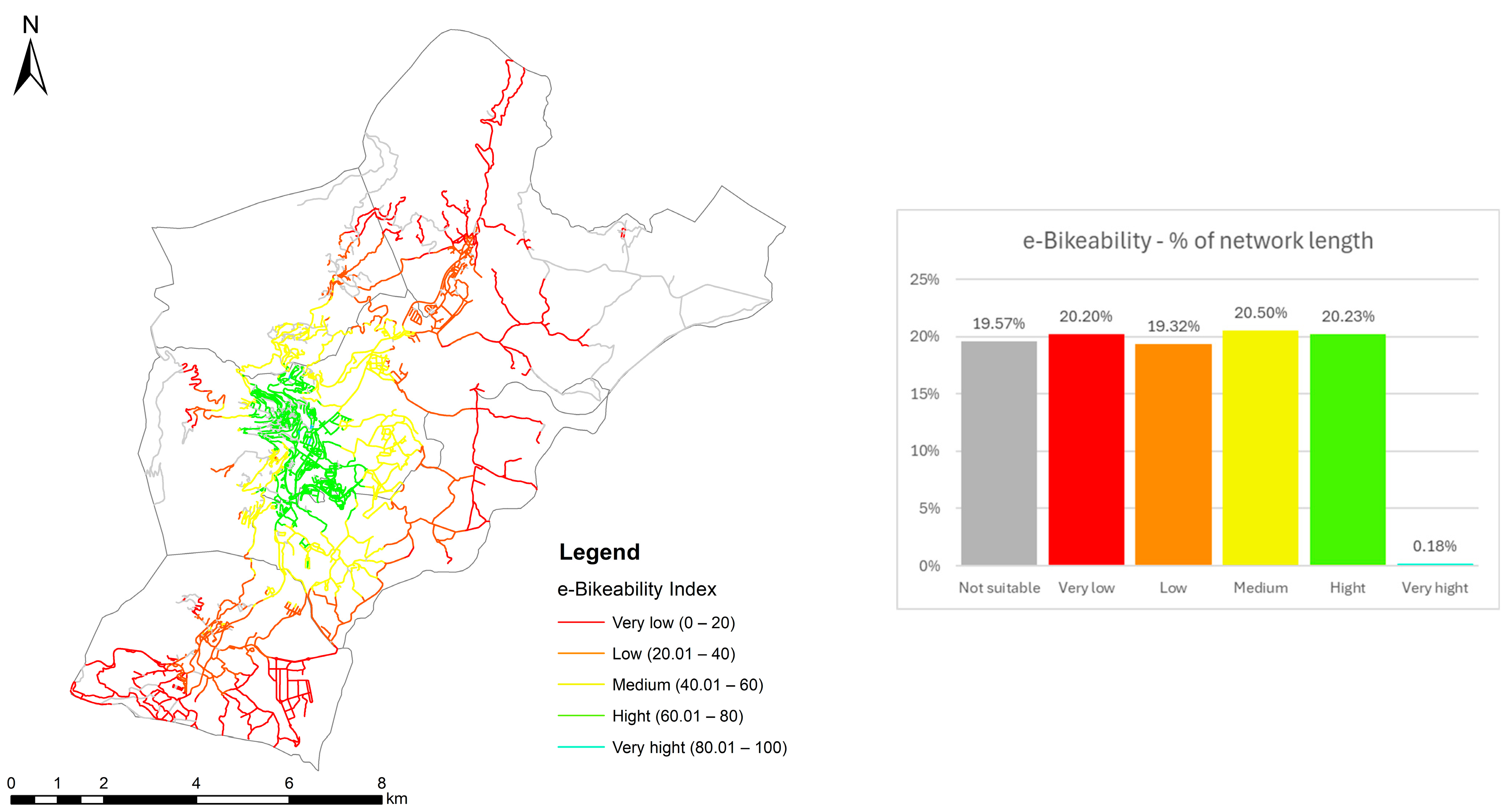

| e-Bikeability | km | 77.67 | 80.14 | 76.68 | 81.33 | 80.28 | 0.68 |

| % | 19.57 | 20.20 | 19.32 | 20.50 | 20.23 | 0.18 | |

| Active Mobility 1 (walk + bike) | km | 0 | 241.06 | 99.66 | 39.87 | 16.02 | 0.16 |

| % | 0 | 60.75 | 25.12 | 10.05 | 4.04 | 0.04 | |

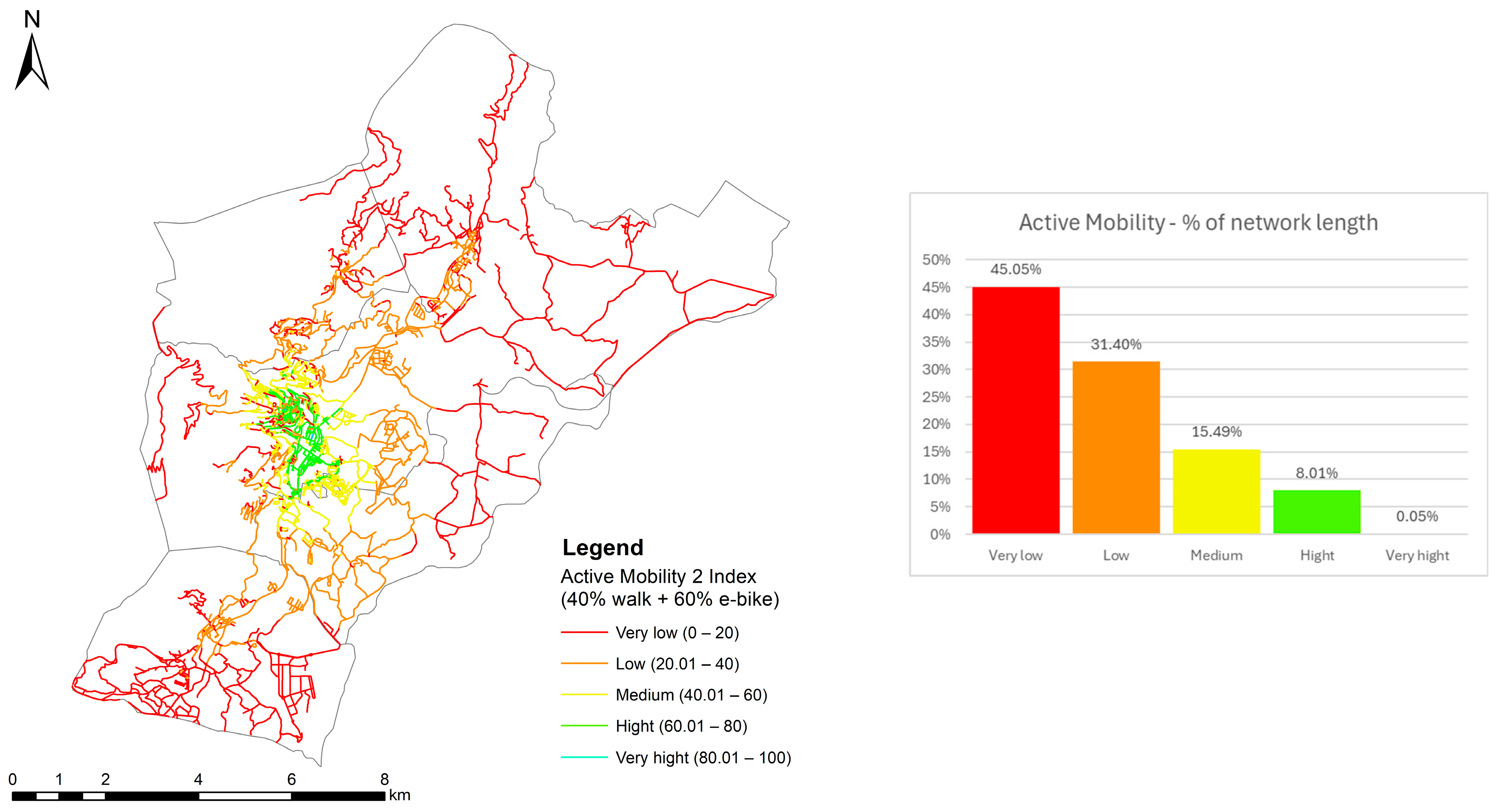

| Active Mobility 2 (walk + e-bike) | km | 0 | 178.77 | 124.60 | 61.48 | 31.77 | 0.16 |

| % | 0 | 45.06 | 31.40 | 15.49 | 8.01 | 0.05 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, B.; Ferreira, S.; Lucena, P. Automated Geographic Information System Multi-Criteria Decision Tool to Assess Urban Road Suitability for Active Mobility. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8040206

Santos B, Ferreira S, Lucena P. Automated Geographic Information System Multi-Criteria Decision Tool to Assess Urban Road Suitability for Active Mobility. Urban Science. 2024; 8(4):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8040206

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Bertha, Sandro Ferreira, and Pollyanna Lucena. 2024. "Automated Geographic Information System Multi-Criteria Decision Tool to Assess Urban Road Suitability for Active Mobility" Urban Science 8, no. 4: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8040206

APA StyleSantos, B., Ferreira, S., & Lucena, P. (2024). Automated Geographic Information System Multi-Criteria Decision Tool to Assess Urban Road Suitability for Active Mobility. Urban Science, 8(4), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci8040206