Abstract

Healthy community assessment standards significantly influence community design and planning and are an important measure of a community’s ability to support health and well-being. Previous studies have mostly focused on built-environment indicators. However, building a healthy community is a complex issue involving multiple dimensions and factors. The consideration of the full range of health promotion factors is the key to determining their potential impact on individuals’ health. It is necessary to consider multiple perspectives to deepen the understanding of community health influences and enhance the effectiveness of the implementation of the assessment standards. The socio-ecological model (SEM) provides a critical framework for understanding the multiple influences on individual health. In this study, a two-dimensional interdisciplinary analytical framework of “socio-ecological factors–development goals” is developed by integrating development goals that summarize building considerations in assessment standards. Contextual analysis is used to examine the provisions of the following assessment standards: Assessment Standard for Healthy Community (ASHC), Assessment Standard for Healthy Retrofitting of Existing Residential Area (ASHRERA), WELL Community Standard (WELL), and Fitwel Certification System of Community (Fitwel). The results show that community and organization factors are used more than interpersonal and policy factors among the four standards. Humanistic constructions lack attention in the ASHC and ASHRERA standards compared with the other standards. The differences between the four standards indicate that there is a need to focus on regional features and develop locally adapted interventions. This study offers a novel exploration of the potential effectiveness of healthy community assessment standards from a multidisciplinary perspective. The results of this study support standard-setters and planners in the development of interventions to improve building healthy communities using intersectionality frameworks.

1. Introduction

The acceleration of urbanization and the pursuit of a higher quality of life have created an urgent need to build more healthy urban environments [1,2,3,4]. Building healthy communities has become an important component of healthy cities and the promotion of residents’ health [5,6]. Healthy community assessment standards are one of the key tools for realizing the aim of healthy urban environments [7].

Some countries have developed assessment standards for healthy community development or have added the assessment of community health performance to existing standards. Assessment standards are developed based on different sources of evidence-based rationale, and their indicator content, threshold requirements, and strategy recommendations vary. However, some of the standards are applied internationally, which raises a question: can healthy community assessment standards be applied to community development in countries with different climatic, social, cultural, or economic contexts? This study examines this question by comparing the differences between a selection of existing assessment standards.

The assessment standards investigated in this study focus on built environment indicators that cover a wide range, such as air, water, nutrition, and exercise, which significantly influence the design and planning of communities. However, building a healthy community is a complex issue that involves multiple dimensions and factors [8,9]. It is difficult to fully realize the promotion of residents’ health by focusing solely on the dimension of architectural and environmental design [10]. Therefore, in this study, in-depth research on how healthy community assessment standards consider multiple influencing factors related to health promotion will be conducted to evaluate their potential effectiveness in promoting residents’ health.

There have been significantly fewer studies addressing healthy community assessment standards than those addressing green building or sustainable development standards over the past few years. The existing research mainly focuses on exploring the diversity [11,12,13], thresholds [14,15], and weights [16] of the built environment indicators [17], comparing assessment methods and indicator systems of different standards [18,19]. Previous studies have lacked systematic consideration of factors affecting health from multidisciplinary perspectives, such as social aspects, economic aspects, and cultural aspects. The lack of comprehensive consideration from multiple perspectives in assessment standards makes it difficult to achieve the expected intervention effectiveness on individual health. Therefore, it is necessary to break through single perspectives and utilize multidisciplinary approaches to study these assessment standards [20,21].

The socio-ecological model provides a critical conceptual framework to understand the multiple influences on individual health [22]. This model provides a holistic understanding of individual health promotion and focuses on the interconnections between individuals, organizations, communities, and societies [23]. The socio-ecological model has been widely used in public health studies and for various health promotion projects, such as rural health [24,25], healthy campus [26], and the HEART project [27]. The concept of development goals summarizes several major building considerations in assessment standards. A matrix analysis of development goals using the socio-ecological model can refine interventions from a practice-combined perspective. However, how the socio-ecological factors operate in assessment standards and how they contribute to development goals remains unclear.

In this context, the purpose of this study lies in exploring the mechanism of mainstream healthy community assessment standards from the socio-ecological point of view, identifying the differences, limitations, and potential optimization spaces. The following three research questions are discussed in this study:

- How are socio-ecological factors and their measures proportionally distributed in the provisions of assessment standards?

- How is the corresponding proportion of socio-ecological factors in the development goal sections distributed in different assessment standards?

- What are the characteristics of the distribution of socio-ecological factors and their measures in the detailed development goals of different assessment standards?

This study develops a two-dimensional analytical framework based on the socio-ecological model and development goals. Contextual analysis is used to conduct a comparative study of four mainstream healthy community assessment standards. This work generates fresh insight into an interdisciplinary theoretical point of view on the study of assessment standards. The results of this study contribute to the development and governance of healthy communities moving in a more comprehensive and sustainable direction.

2. Background

This section provides a brief introduction to valid healthy community assessment standards and provides a review of the literature on assessment standards, development goals in healthy communities, and the socio-ecological model.

2.1. Healthy Community Assessment Standards

The concept of healthy communities has gradually developed with the advancement of global public health concepts and the acceleration of urbanization. Countries and international organizations have developed certain evaluation measures to assess and promote the construction of healthy communities. There are currently two common forms of community health assessment (Table 1): The first form is the development of independent systematic assessment standards, such as the WELL community standard (WELL) [28], Fitwel certification system of community (Fitwel) [29], the assessment standard for healthy community (ASHC) [30], and the assessment standard for healthy retrofitting of existing residential area (ASHRERA) [31]. The second form is the integration of the evaluation of healthy communities into existing sustainable development standards or green community standards or in cooperation with independent healthy community assessment standards, such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) [32], Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) [33], Haute Qualité Environnementale (HQE) [34]. Considering the impact of the inconsistent proportions of health assessment content in the overall content of standards that include health assessment content, this study only focuses on independent healthy community assessment standards. The following section briefly introduces the four healthy community assessment standards.

Table 1.

Information on mainstream assessment standards, including health assessment.

2.1.1. WELL Community Standard

The WELL Community Standard (WELL) was launched by the International WELL Building Institute (IWBI) in 2017. It aims to build community environments that support the overall health and well-being of residents through specific performance requirements and design strategies [28]. Currently, a total of 83 community projects in the United States, Mauritius, China, Spain, Brazil, Australia, Italy, Luxembourg, Switzerland, France, Ireland, Sweden, Egypt, the United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates, Canada, Philippines, Ireland, Germany, Rwanda, Thailand, and Poland have been certified by the WELL Community Standard [37]. The standard is based on ten core concepts: air, water, nourishment, light, movement, thermal comfort, sound, materials, mind, and community. The ten concepts are composed of 110 features. Every feature addresses specific aspects of the health and well-being of community members. Each feature is divided into parts and then further into requirements [28].

2.1.2. Fitwel Certification System of Community

The Fitwel Certification System of Community (Fitwel) was created by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) and is administered by the Centre for Active Design (CfAD). The standard aims to enhance the health and well-being of residents by optimizing the built and community environments [38]. The Fitwel certification system is based on a significant body of scientific research and evidence and provides a set of flexible, actionable guidelines for communities and buildings of all sizes and types [29]. At present, 37 community projects have been registered and certified by the Fitwel system in the United States, the United Kingdom, China, Canada, and Brazil [39]. Fitwel addresses health holistically as an interconnected system. Its strategies link to at least one of seven Health Impact Categories: increase physical activity, promote occupant safety, reduce morbidity and absenteeism, support social equity for vulnerable populations, instill feelings of well-being, impact surrounding community health, and enhance access to healthy foods [29]. The project worksheet for the community assessment contains 12 chapters of strategy requirements for achieving Fitwel certification [40]. The Fitwel chapter names are listed in Section 3.1.

2.1.3. Assessment Standard for Healthy Community

The Assessment Standard for Healthy Community (ASHC0), was issued by the China Association for Engineering Construction Standardization and the Chinese Society for Urban Studies in 2020. The ASHC focuses on providing healthier environments, facilities, and services that promote physical and mental well-being and achieve improved health performance. The standard covers six aspects: air, water, comfort, exercise, humanity, and service. The air aspect consists of four dimensions: pollution source, concentration limits, monitoring, and greening. The water aspect consists of three dimensions: water quality, safety, and environment. The comfort aspect consists of three dimensions: noise control and soundscape, light environment and view, and thermal comfort and microclimate. The exercise aspect consists of sports venues, fitness spaces, and playground dimensions. The humanity aspect consists of three dimensions: communication, psychology, and suitable strategies for the elderly and children. The service aspect consists of management, food, and activities dimensions. Each dimension consists of several requirements [30].

2.1.4. Assessment Standard for Healthy Retrofitting of Existing Residential Area

The Assessment Standard for Healthy Retrofitting of Existing Residential Area (ASHRERA) was issued by the Chinese Society for Urban Studies in 2020. The ASHRERA aims to standardize the assessment procedure and to achieve an improvement in the health performance of existing residential areas. The ASHRERA proposes that the assessment of the healthy retrofitting of existing residential areas should follow the principle of multidisciplinary integration. Moreover, the assessment should consider the current context of the existing residential areas and the objectives of the transformation, as well as the climate, environment, resources, economy, and culture of the region in which they are situated. The standard carries out a comprehensive evaluation of the air, water, comfort, exercise, humanity, and service [31]. The framework of assessment dimensions is similar to the ASHC, but it proposes an evaluation of the retrofitting effect.

2.2. Healthy Community Assessment Standards Studies

At present, academic research has begun to pay attention to these standards. Most of the literature focuses on the assessment content of the standards. The focus on the physical environment mainly explores the impact of factors such as green space area [41,42], air quality [43], and water quality [44,45] on residents’ health. The focus on basic community service facilities mainly explores the impact of the number of medical facilities [46,47] and the accessibility of medical services [48,49] on the health of community residents. Research on the social environment focuses on the impact of community cohesion [50], neighborhood relations [51], and community security [52] on residents’ mental health and satisfaction. These studies provide strong support for the composition of the assessment system and the indicator limits. At the same time, some studies compare different assessment standards. For example, Antonio Marotta [53] compared the strategies developed by WELL, Fitwel, and LEED regarding responses to infectious diseases and underlined several limitations. Xinzheng Zhao [54] used Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs to compare WELL, LEED-ND, the Taiwan Healthy Community Six-Star Program Promotion Plan, the Details of the Guidance Standards for the “Six Types” of Communities in Beijing (Trial Implementation), and some other standards to analyze the trends and shortcomings of current evaluation system research.

The core of the current research on healthy community assessment standards is the impact of the built environment on health. Different standards have their own relatively systematic assessment content, and the indicator system has not yet been completely unified. In addition, there is a lack of research considering the applicability in cross-cultural and different socioeconomic backgrounds. There is also the challenge of cost-effectiveness in practical applications. Therefore, future research should focus on integrating multidisciplinary theories and methods to establish more comprehensive healthy community assessment standards and explore best practices in different socioeconomic contexts.

2.3. Development Goals in Healthy Communities

In recent years, scholars have proposed some built environment frameworks for healthy cities and communities from different perspectives [10,55,56]. For example, Lan Wang [57] identified resources, land use, urban form and design, transport and movement networks, as well as green blue and public open spaces as urban and territorial planning influences in the WHO report. Yuyang Zhang [58] proposed that neighborhood risk factors include five domains: physical environment, service and commercial environment, pollution and hazards, social environment, and safety and injury. Altaf Engineer’s [59] built environment considerations for health and well-being consist of environmental control, biophilia, air quality, views, light, social spaces, and spatial layout.

The existing studies have not yet formed a unified framework due to different research focuses, sources of evidence, and perspectives. However, the studies share some indicators, such as the physical environment and social environment. Meanwhile, it can be seen that these frameworks have discrepancies with established healthy community assessment standards and are not fully compatible.

2.4. Socio-Ecological Model

The socio-ecological model (SEM) of health behavior, which mainly guides behavioral intervention, was put forward by McLeroy and his colleagues in 1988. The SEM posits that health is not solely determined by biological factors but instead is influenced by a collection of influences that occur at various levels [60]. The model considers the major contributors including intrapersonal factors, interpersonal processes and primary groups, institutional factors, community factors, and public policy [61]. The strength of the SEM lies in its ability to deeply analyze interactions at various levels, revealing how multiple factors work together to shape an integrated system, in which changes in any of the parts may have far-reaching impacts on the overall system [23,62].

The SEM describes the interactive characteristics of individuals and environments that underlie health outcomes, which have long been recommended to guide public health practices [63,64,65]. For example, sedentary behaviors are related to sex, professions, urban locations, physical activity, environmental characteristics, community attributes, etc. [66]. In the discipline of the built environment, research using the SEM has just begun. Some studies only focus on the community dimension in the SEM, which explores the association of the built environment with certain health behaviors. For example, the leisure physical activity of the elderly in Nanjing is closely related to street pavement slope, street connectivity, and geographic location [67]. Few studies have systematically explored the role of all dimensions of the SEM in the construction of the built environment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Standards and Text Selection

This study selected WELL (version v2 Q4 2022-Q4 2023) [28], Fitwel (version v2.1) [29], ASHC (version T/CECS 650-2020 and T/CSUS 01-2020) [30], and ASHRERA (version T/CSUS 08-2020) [31] as research subjects to explore community-scale healthy construction. There are two reasons for the selection of these standards: 1. The standards are independent and systematic tools that only focus on health and well-being performance; 2. the standards target the community dimension.

Only the main assessment parts of ASHC, ASHRERA, WELL, and Fitwel were reviewed in this study. The introduction, terms, promotion, or innovation chapters of all four standards were not included (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chapters selected in assessment standards.

3.2. Development of a Two-Dimensional Analytical Framework

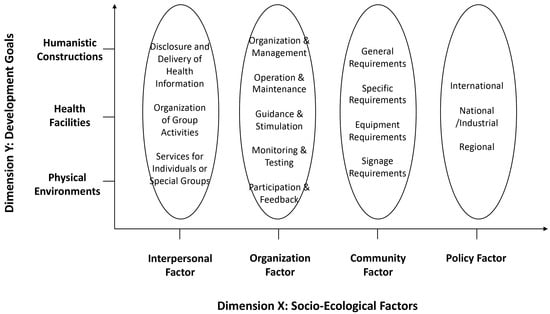

This study develops a two-dimensional analytical framework of “socio-ecological factors–development goals” from the perspective of the socio-ecological model of health promotion and development goals for building healthy communities.

3.2.1. Dimension X: Socio-Ecological Factors

Socio-ecological models have the potential to guide comprehensive population-wide approaches to changing behaviors in order to reduce serious and prevalent health problems. The core concept is that behavior has multiple levels of influence, including intrapersonal, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy levels. The influences interact across these different levels. Multi-level interventions could maximize changes in behavior. The socio-ecological model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the multiple influences that affect health behaviors [68]. Applying the socio-ecological model in assessment standard research can support the development of an improved understanding of the direct interaction of assessment standards with community residents, social organizations, and the entire community ecosystem.

The research conducted in this study is based on McLeroy et al.’s ecological model of health behavior [60] and is adapted to include the spheres of interpersonal, organization, community, and policy. The intrapersonal level is excluded from this study because it refers to individual biological and psychological states. The measures related to each factor were summarized and extracted from the assessment provisions of the four selected assessment standards.

In this study, the interpersonal factors focus on interventions that can contribute to personal literacy and interpersonal interactions. The factors were divided into three types of measures, namely the disclosure and delivery of health information, the organization of group activities, and the services for individuals or special groups. The organization factors focus on the organization and management, operation and maintenance, guidance and stimulation, monitoring and testing, and participation and feedback measures provided by the property management unit. The community factors focus on community creation, such as parks, transportation, and cyclist infrastructure. The community factors consist of general requirements, specific requirements, equipment requirements, and signage requirements. The general requirements refer to broad guidance for the development of community spaces or environments. The specific requirements refer to detailed guidance including the number or extent of a space or environment. The policy factors refer to public policies, guidelines, standards, laws, or regulations that a healthy community needs to meet. The policy factors were divided into three levels: international, national or industrial, and regional. Table A1 in Appendix A provides specific divisions and examples.

3.2.2. Dimension Y: Development Goals

The development goal framework is summarized and extracted from the assessment provisions of the four selected assessment standards and comprehensively considers the opinions of the previous scholars. The establishment of this framework allows for a systematic comparison of the assessment contents of these four standards.

The healthy community development goals are divided into three sections: physical environments, health facilities, and humanistic constructions. The physical environments comprise five categories: air, water, sound, light, and thermal comfort. Health facilities refer to roads and transportation, sports facilities, public spaces, healing environments, and food environments. Roads and transportation include the design requirements for community roadways, fitness trails, cycling paths, parking lots, and public transit and bicycle-sharing operation requirements. Sports facilities refer to indoor and outdoor sports venues, child- and senior-friendly spaces, pet activity spaces, and supporting fitness equipment. Public spaces refer to social spaces, gathering spaces, primary medical spaces, educational places, art and cultural venues, etc. Healing environments refer to places that contribute to residents’ mental healthcare and restorative blue-green spaces and building spaces. Food environments refer to community food sales, nutrition education, community farms, alcoholic environments, breastfeeding support, etc. The humanistic constructions include local character, materials and safety, hygiene and cleanliness, and public services. The public services include community conventions, volunteering, information surveys and feedback, health impact assessments, community recovery, participatory development, etc. Table A2 in Appendix A provides specific divisions and examples.

3.2.3. The Two-Dimensional Analytical Framework of “Socio-Ecological Factors-Development Goals”

The four factors and measures of the socio-ecological model propose interventions for individual health from different dimensions. The development goal framework shows the development direction that needs to be accomplished in building a healthy community. All factors and their measures in dimension X have corresponding performance in each development goal section and their detailed development goals in dimension Y.

The matrix cross-matching reveals the proportional distribution of different socio-ecological factors and measures in each development goal. The distribution analysis helps us gain a multidimensional understanding and formulate targeted improvement and enhancement suggestions. Figure 1 illustrates the two-dimensional analytical framework of the “socio-ecological factors–development goals”.

Figure 1.

A two-dimensional analytical framework of the “socio-ecological factors–development goals”.

3.3. Contextual Analysis

3.3.1. Coding

The assessment provisions were broken down into analysis units, which had distinct meanings and therefore could not be further subdivided. Each analysis unit was classified into the corresponding nodes of dimension X and dimension Y. In total, 277 analysis units of WELL, 177 analysis units of Fitwel, 250 analysis units of ASHC, and 235 analysis units of ASHRERA were identified. Table 3 presents part of the ASHC coding sheet as an example.

Table 3.

Part of the ASHC coding sheet.

3.3.2. Statistical Analysis

A total of 7 nodes and 36 descendant nodes (Table 4) were manually coded using Nvivo 11 Plus analysis software following the two-dimensional analytical framework.

Table 4.

Number of reference points of the nodes and descendant nodes.

Two types of matrix-coding analysis were performed. The first is a matrix consisting of dimension X nodes to dimension Y nodes according to different standards. The second matrix consists of dimension X nodes and their descendant nodes to dimension Y descendant nodes of different standards.

Then, the number of reference points was obtained, and the percentage of reference points was calculated in Excel 16.84.

4. Results

4.1. Proportional Distribution of Socio-Ecological Factors and Their Measures in Standards

The first research question asked how the socio-ecological factors and their measures are proportionally distributed in the provisions of assessment standards. Table 5 displays the results obtained from the preliminary analysis of the socio-ecological factors.

Table 5.

Proportional distribution of socio-ecological factors and their measure.

It is apparent from this table that the community factors represent the largest proportion of the four standards, exceeding all other factors. The community factors category occupies 63.20% in ASHC with the highest percentage and 40.79% in WELL with the lowest percentage among the four standards. The percentage of reference points of the community factors far exceeds the second factor’s in ASHC (46.00%); however, the difference is not that apparent in ASHRERA (24.25%), WELL (9.02%), and Fitwel (18.64%). Statistics at the measure level show that general requirements and specific requirements account for the main proportion of the four standards. The difference between the percentage of general and specific requirements in ASHC, ASHRERA, and Fitwel does not exceed 2.20%; however, specific requirements in WELL account for 7.22% more than the general requirements.

The second-largest factor category among the four standards is the organization factor. It occupies 31.77% in WELL, 30.51% in Fitwel, 28.09% in ASHRERA, and only 17.20% in ASHC. In terms of measures, the percentages of organization and management and operations and maintenance together account for 12.40% of ASHC and 21.46% of Fitwel, both of which are over 70% of its total community factors. These two measures dominate the community factors in ASHC and Fitwel. ASHRERA emphasizes applying monitoring and testing measures, at 12.77%, in order to continuously observe community dynamics and respond in a timely manner [31]. While the measures used the most in WELL are organization and management (10.83%) and monitoring and testing (9.75%), this standard also utilizes guidance and stimulation (5.42%) measures more effectively than the other standards.

The third-largest factor is the interpersonal factor. The total percentage in WELL is over 4.40% higher than that of the other three standards. Even though the total percentages in ASHC, ASHRERA, and Fitwel are around 10%, the three measures are applied inconsistently. Organization of group activities is more commonly used in ASHRERA (5.96%) and Fitwel (6.78%); WELL is good at using the disclosure and delivery of health information (6.86%) and services for individuals or special groups (6.14%); and ASHC is more balanced in the three measures.

As for policy factors, the total percentages of the four standards are around 10%. However, more than 87.50% of articulations with standards or regulations in ASHC and ASHRERA are at the national or industry level, while WELL and Fitwel have more connections with international regulations.

In summary, the results show that the four standards have overall similarities in the distribution of socio-ecological factors. However, there are differences in the choice of measures, especially in the organization and interpersonal factors, which are further analyzed in the following chapters.

4.2. Proportional Distribution of Socio-Ecological Factors in Development Goal Sections

The next research question asked how the corresponding proportion of socio-ecological factors in the development goal sections is distributed in different assessment standards. Table 6 shows the matrix coding of the socio-ecological factors with the development goals sections.

Table 6.

Proportional distribution of socio-ecological factors in development goal sections.

The physical environment is the most concentrated development goal section of ASHC, ASHRERA, and WELL; the health facilities ranked second with about 5% fewer in total. However, the distribution of Fitwel is quite different; Fitwel allocated more than 50% of its provisions to healthy facilities and then concentrated on humanistic constructions with an allocation of 25.99%.

The interpersonal factors are allocated more in health facilities in ASHC, ASHRERA, and Fitwel. The percentage of interpersonal factors allocated to health facilities in ASHC (6.40%) exceeds the combined percentages of physical environments and humanistic constructions; this phenomenon also appears in ASHRERA (8.09%) and Fitwel (6.78%).

As for the organization factors, except for Fitwel, which mainly allocated its provisions to healthy facilities (12.99%) and humanistic constructions (12.43%), the other three standards allocate more organizational measures to physical environments.

The community factors are used mostly in physical environments and health facilities in ASHC, ASHRERA, and WELL. ASHC allocates similar percentages to these two goals; meanwhile, ASHRERA and WELL allocate a larger number of provisions to health facilities compared with physical environments. The majority of provisions using community factors in Fitwel relate to healthy facilities (35.59%).

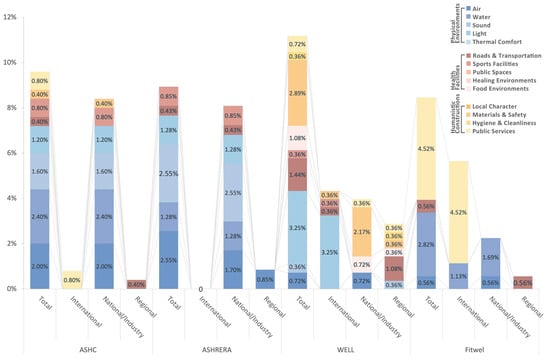

The physical environment is the development goal section with the most intensive direct alignment to policies and regulations in ASHC, ASHRERA, and WELL. Fitwel allocates more policy regulations to humanistic constructions, with 4.52%, and physical environments, with 3.39%.

The results show that the application of socio-ecological factors to development goal sections in Fitwel varies considerably from the other standards. To comprehensively understand the relationship between socio-ecological factors and development goals, detailed distributions of measures and specific goals need to be discussed.

4.3. Characteristics of the Distribution of Socio-Ecological Factors in Development Goals

The third research question aims to identify the characteristics of the distribution of socio-ecological factors and their measures in the detailed development goals of different assessment standards. The four factors of interpersonal, organization, community, and policy are explained in the subsequent sections.

4.3.1. Proportional Distribution of Interpersonal Factors in Development Goals

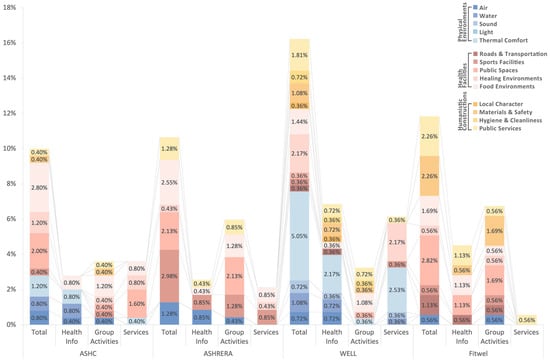

Figure 2 compares the application of interpersonal factor measures to different development goals in the different standards. The results show obvious differences among the four standards.

Figure 2.

Percentage of reference points of interpersonal factors allocated to development goals.

In ASHC, organizing group activities in food environments (1.20%) and providing services for individuals or special groups in public spaces (1.60%) are relatively prominent. Moreover, there is no application of interpersonal factors in sound, light, roads and transportation, local character, and hygiene and cleanliness.

ASHRERA uses the organization of group activities, with a larger proportion in public spaces (2.13%), sports facilities (1.28%), and food environments (1.28%). Although the total amount of interpersonal factors is not small, the distribution of development goals is very uneven, for it only focuses on six development goals. There is no application in the other eight development goals, which are water, sound, light, thermal comfort, roads and transportation, local character, materials and safety, and hygiene and cleanliness.

WELL allocates larger total percentages of interpersonal factors than the other standards. Its measures of specialization are the disclosure and delivery of health information and services for individuals or special groups. All development goals except light are intervened by interpersonal measures, and the most focused are thermal comfort (5.05%) and healing environment (2.17%).

The total percentage of applying interpersonal factors in Fitwel ranks second among the four standards. The organization of group activities is the most used measure, which focuses more on public spaces (1.69%) and materials and safety (1.69%). The only physical environment goal focused on is air (0.56%). The percentage of services for individuals or special groups is minimal compared with the other standards, and it is only used in public services.

Table 7 summarizes specifications derived from the matrix intersection of the three measures of interpersonal factors with development goals. Several specifications are mentioned in more than one standard, while some specifications appear in only one assessment standard. The different specifications would be useful for examining the differences between the standards [6]. Some of the distinguished specifications are described below.

Table 7.

Specification summary of matrix research on individual factors.

ASHC mostly provides lectures to improve residents’ knowledge of nutrition, physiology, psychology, and safety. ASHC provides daycare services to people such as children, the elderly, and the disabled and also offers special food for dietary control users [31].

ASHRERA enhances advertising and implements complementary fitness programs to promote residents’ motivation and participation [30].

WELL provides hearing health education, hearing protection programs, legionella risk management plans, and dialog with professionals to improve energy efficiency. Also, WELL proposes to educate residents and visitors about the design and operation of local culture and history to enhance the sense of local identity [28].

Fitwel improves air quality through community participation, such as tree planting, air quality counseling and education, and clean air action days. Fitwel enhances community vibrancy while increasing street utilization by supporting streetscape activities [40].

4.3.2. Proportional Distribution of Organization Factors in Development Goals

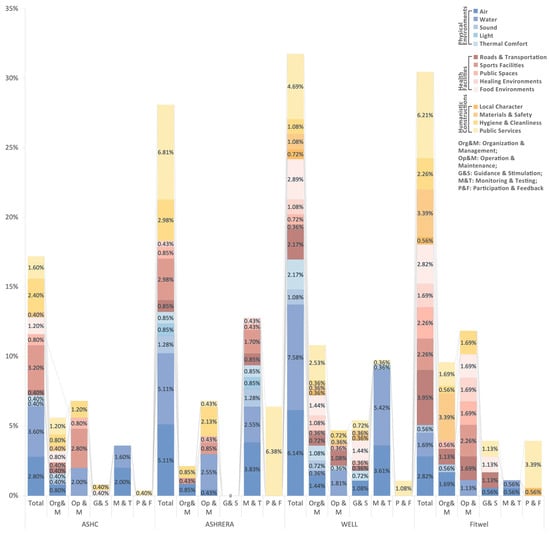

Figure 3 compares the application of organization factor measures with different development goals in the different standards. The five measures of organization factors are unevenly applied among the four standards. Each standard has its focused measures and their corresponding development goals.

Figure 3.

Percentage of reference points of organization factors allocated to development goals.

ASHC concentrates on organization and management and operation and maintenance, which covers all the development goals except light, healing environment, and local character. Operation and maintenance are highly used in sports facilities (2.80%) and water (2.00%). Guidance and stimulation are rarely used compared with WELL.

ASHRERA specializes in monitoring and testing. It is applied in all physical environments and public facilities development goals except the food environments, and it has especially great attention on air (3.83%) and water (2.55%). It also allocated a great percentage of participation and feedback to public services (6.38%) to realize post-retrofit surveys [31].

The organization and management measure covers all development goals except light and public spaces in WELL. Its highest proportion was allocated to public services (2.53%). Monitoring and testing is the second most used measure, which has a great percentage of water (5.42%) and air (3.61%). What stands out in the figure is guidance and stimulation. This measure is used more in WELL than the other three standards, with unique provisions on thermal comfort, public spaces, local character, and materials and safety.

In Fitwel, the operation and maintenance measure is the most used and has a higher percentage compared with the other standards. Moreover, this measure is relatively balanced in different development goals of health facilities. The second most widely used measure is organization and management, which is more prominent in materials and safety (3.39%).

Table 8 summarizes specifications derived from the matrix intersection of the five measures of organization factors with development goals. Some of the distinguished specifications are described below.

Table 8.

Specifications summary of matrix research on organization factors.

ASHC proposes to encourage online linkages between the community residents and produce distributors to advance residents’ efforts to purchase produce online [31].

ASHRERA proposes to strengthen the continuous maintenance of the social and health information service network platform or application [30].

WELL provides financial assistance to low-income households for energy use and administers public services to reduce people’s low-temperature environmental exposure conditions. WELL also meets residents’ access to healthcare facilities by providing non-emergency medical transportation services, public transportation discounts, and shuttle services. Also, WELL promotes local retail to enliven the local economy [28].

Fitwel suggests that communities should establish and implement construction safety programs to safeguard safety issues throughout all phases of development. And placemaking plans should be made for community streetscape activities [40].

4.3.3. Proportional Distribution of Community Factors in Development Goals

Figure 4 compares the application of community factor measures with different development goals in the different standards. There is a clear trend of decreasing the total percentage of general requirements, specific requirements, equipment requirements, and signage requirements in ASHC, ASHRERA, and Fitwel. However, in WELL, specific requirements occupy a higher percentage than general requirements. However, the application of different measures focuses on different development goals in different standards.

Figure 4.

Percentage of reference points of community factors allocated to development goals.

ASHC has a higher percentage of general requirements in water (3.60%) and roads and transportation (3.60%) than other development goals. Specific requirements (7.20%) and equipment requirements (4.00%) are highly used in sports facilities.

ASHRERA has more general requirements in roads and transportation (3.83%) and materials and safety (2.55%) than other development goals. Specific requirements are more used in sports facilities (5.11%) and thermal comfort (5.11%). Equipment requirements are highly used in sports facilities (3.40%).

WELL strengthened materials and safety (3.25%) by using general requirements. Its specific requirements are used more in roads and transportation (3.61%) and healing environments (3.61%). It also used equipment requirements in food environments (0.36%), hygiene and cleanliness (0.36%), and public services (0.72%), which are not seen in the other standards.

Fitwel has a strong focus on roads and transportation, with general requirements (6.21%), specific requirements (3.95%), and signage requirements (4.52%). Public spaces (4.52%) also have many specific requirements.

Table 9 summarizes specifications derived from the matrix intersection of the four measures of community factor with development goals. Some of the distinguished specifications are described below.

Table 9.

Specifications summary of matrix research on community factors.

ASHC put forward higher requirements for indoor and outdoor air-quality-monitoring systems, intelligent lighting systems, and rainwater- and sewage-discharge-monitoring systems [31].

ASHRERA and ASHC take more requirements to reduce the heat island effect and optimize the wind environment, such as the requirement that under typical wind speed and direction in winter, the wind speed in the pedestrian area around the building is less than 5 m/s at 1.5 m from the ground height [30,31].

WELL proposes distribution distances for different healthy facilities as a way to control accessibility and realize mixed development of residential land. For example, blue–green spaces and restorative built spaces, such as houses of worship, meditation or prayer spaces, historic sites, or promenades, are called for within the project boundary or a 400 m (0.25 mile) walking distance of the project boundary. Particularly, in the roads and transportation section, pedestrian-scale design is proposed to enliven streets, such as active façades, street furniture, and artistic installations. Breastfeeding spaces are the most extensive requirements compared to the other standards [28].

Fitwel proposes site remediation and redevelopment, especially underutilized or underbuilt lots, which would make a significant positive impact on reducing land contamination, increasing land-use efficiency, enhancing community vitality, and strengthening community identity. To improve open spaces’ visibility, it proposes to remove all physical barriers or limit the height of walls, fences, bollards, concrete barriers, and other physical barriers to a maximum of 4 feet or 1.2 m [40].

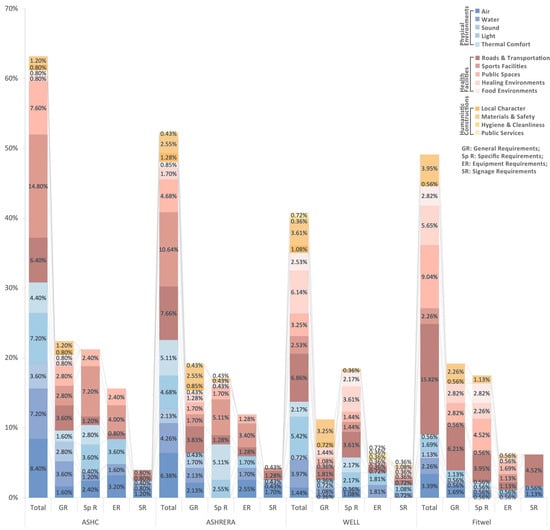

4.3.4. Proportional Distribution of Policy Factors in Development Goals

Figure 5 compares the application of policy factor measures with different development goals in the different standards. This figure shows that ASHC and ASHRERA have similar characteristics.

Figure 5.

Percentage of reference points of policy factors allocated to development goals.

The application of policy factors focuses on the national/industry level in ASHC and ASHRERA. It is involved in air, water, sound, light, and sports facilities in both standards. The only provision connected to international policies in ASHC is in public services (0.80%).

WELL has a more balanced distribution of policy factors than the other standards. The total proportions at the international, national/industry, and local levels do not significantly vary. The international policies are mostly used in light (3.25%). The materials and safety (2.17%) measure has a strong focus on national/industry legal prohibitions or restrictions on lead, asbestos, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and mercury [28]. As for the regional policies, it requires more on roads and transportation (1.08%). Compared with the other standards, only WELL has policy provisions on food environments and hygiene and cleanliness. WELL also requires at least two levels of regulations in roads and transportation, food environments, materials and safety, and public services.

Fitwel utilizes the policy factors less heavily compared with the other standards. The policy factors are only used in air (0.56%), water (1.13% at international and 1.69% at national/industry level), roads and transportation (0.56%), and public services (4.52%).

Table 10 summarizes specifications derived from the matrix intersection of the three levels of policy factors with development goals. Some of the distinguished specifications are described below.

Table 10.

Specifications summary of matrix research on policy factors.

ASHC requires community property management units to meet ISO management system certification [31]. ASHRERA requires the green space ratio to be no less than regional requirements [30].

WELL has more connections with international guidelines or standards, such as LEED, Joint IDA-IES Model Lighting Ordinance (MLO), and WHO [28]. Fitwel requires a healthy building certification, which is obtained as a scoring component of a healthy community certification rather than an innovation practice [40].

5. Discussion

By introducing the socio-ecological model into a study of assessment standards and combining it with healthy community development goals, a two-dimensional analytical framework was formed. This framework provided an interdisciplinary perspective of the potential effectiveness of each of the healthy community assessment standards in promoting individual health. Based on the results of our analysis, we can draw some considerations for future development.

5.1. Interpersonal and Policy Factors Should Be Strengthened

The first research question in this study sought to determine how the proportion of socio-ecological factors and their measures is distributed in the provisions of assessment standards.

This study found that the socio-ecological factors in the four standards showed a uniform trend. The distribution of the socio-ecological factors from largest to smallest was as follows: community factors, organization factors, interpersonal factors, and policy factors in all four standards. Community and organization factors account for a distinctive larger proportion than the other two factors.

According to the data, we can infer that there is a preliminary consensus on the distribution of current community health interventions from the socio-ecological point of view. The community and organization factors are the main intervention dimensions of a healthy community, which are related to the fact that the compilation and implementation of healthy community assessment standards originated in the planning and development field. Moreover, urban governance has long been considered an effective approach to achieving a healthy urban environment [69,70,71]. Meanwhile, the interpersonal and policy dimensions are reflected in the standards, but to a lesser extent, and there is still potential to fully utilize the power of these two dimensions.

It can be suggested that interpersonal and policy factors need to be strengthened to achieve better effects during assessment standard updates, especially in ASHC, ASHRERA, and Fitwel. Strengthening interpersonal factors will help to promote individual health awareness and group health behavior choices, thus spontaneously realizing health promotion [72]. Strengthening policy factors can promote the standardization of healthy communities through the interface with multidisciplinary professional standards, breaking down disciplinary barriers and realizing the construction of healthy communities in an integrated and synergistic manner [73,74].

In summary, these results draw our attention to the importance of considering the full use of different socio-ecological factors, especially in terms of strengthening interpersonal and policy factors. This approach should be applied to future revisions of the assessment standards.

5.2. Humanistic Constructions Require More Attention in ASHC and ASHRERA

The second research question in this study was how the corresponding proportion of socio-ecological factors in the development goal sections is distributed in different assessment standards.

The most obvious finding to emerge from the results is that in terms of total percentage, ASHC, ASHRERA, and WELL emphasize physical environments and health facilities, while Fitwel focuses most on health facilities, followed by humanistic constructions.

There is a similarity in the distribution of different socio-ecological factors in the development goal sections in ASHC and ASHRERA. Interpersonal factors are mostly applied to health facilities, while organization and policy factors are mostly applied to physical environments. Moreover, there is no significant difference in the distribution of community factors to health facilities and to physical environments. The reason for the similarity may be that they are possibly cross-referenced during the compilation process because the two standards have the same compiling organization and the publication dates are close to each other.

Different from ASHC and ASHRERA, WELL has the greatest application of interpersonal factors on physical environments, which indicates that WELL attaches great importance to reducing adverse environmental exposures by improving individuals’ understanding of pollution in the environment.

The most prominent feature of Fitwel is that humanistic constructions occupy a higher proportion compared with the other standards. Fitwel has a significant difference in the distribution of total socio-ecological factors compared with ASHC and ASHRERA. This difference means that humanistic constructions require more attention in these two standards. Compared with WELL, the difference in the distribution of socio-ecological factors is not very significant, which shows that WELL and Fitwel have formed a more consistent consensus on the concern for humanistic constructions.

These results suggest that ASHC and ASHRERA lack attention to humanistic constructions or might have some limitations that cannot be easily solved in the early stage of building healthy communities. However, humanistic constructions can improve humanistic care and community character, thus maintaining residents’ sense of community identity and pride [75,76]. The emphasis on humanistic constructions needs to be reinforced by all socio-ecological factors in future updates of the assessment standards.

5.3. Regional Features May Be a Major Factor for Differences and Development Consideration

The third research question explores the characteristics of the distribution of socio-ecological factors and their measures in the detailed development goals in different assessment standards. The results show the differences among the four standards.

The most obvious differences between the standards in the allocation of interpersonal factors are found in sound, local character, and hygiene and cleanliness. WELL specializes in the disclosure and delivery of health information and public services in these development goals, while the other three standards have almost no provisions. Furthermore, in roads and transportation, WELL and Fitwel use the disclosure and delivery of health information measures, while the ASHC and ASHRERA use no measures. In food environments, ASHC and ASHRERA have more requirements than WELL and Fitwel. The reasons for these differences are that, on the one hand, the standard itself slightly lacks emphasis on applying interpersonal factors; on the other hand, the strengthening of interpersonal factors places higher demands on community property managers. Many property managers in China have difficulty accomplishing high-level education and popularizing community work [77], which may be a concern during the compilation of healthy community standards and an impediment to practice.

The difference between the standards in organization factor allocation is primarily in the application of monitoring and testing measures to sound, light, thermal comfort, roads and transportation, sports facilities, public spaces, and healing environments. ASHRERA used the measure in these development goals, while the other standards use the measure only in air and water. It is assumed that ASHRERA widely uses the measure because the assessment subject of this standard is existing communities that need to be upgraded. ASHRERA checks the transformation effect by comparing before and after the implementation. Simultaneously, other standards do not have the problem of improving the historical status of a community. However, regular monitoring and testing of operations help cyclically improve a community. In addition, guidance and stimulation measures are more widely used in WELL than in ASHC and ASHRERA, which can serve as points for subsequent consideration.

The most notable difference between the standards in community factors application is that WELL and Fitwel apply specific requirements more to healing environments and public spaces, while ASHC and ASHRERA focus more on sports facilities. The main reason for this difference may be that the public health risk factors in the two countries are different. Lack of physical activity is an important current risk factor for Chinese residents [78,79]. Sufficient public sports facilities need to be built urgently to meet the needs of residents in China, and public programs should be facilitated to promote physical activity. Mental health and substance addiction [80,81] in the United States require more attention at present, as healthcare and support services are being used more as interventions. In addition, the roads and transportation goal is the one that the four standards all focus on. The difference is that ASHC and ASHRERA mainly apply general requirements to illustrate, while WELL and Fitwel strengthen specific requirements to constrain, which provides better guidance for construction practice; this issue is what ASHC and ASHRERA need to address in the future.

The difference is noticeable in policy factors between the Chinese standards ASHC and ASHRERA and the American standards WELL and Fitwel. Provisions in ASHC and ASHRERA are closely articulated with national or industry standards, and provisions in WELL and Fitwel are more diversified to different levels. The reason for this difference might be, on the one hand, that the standards are targeted at different markets. The American standards WELL and Fitwel need to be adapted to the different government administration and urban planning systems in each state [82]. Meeting the requirements of internationalization in the formulation of the standards can increase their effectiveness, while ASHC and ASHRERA aim to be used in the Chinese national context, which has the same system domestically. On the other hand, urban development in China is government-driven, and the interface with existing national standards is conducive to satisfying the top-down implementation process [83,84,85]. The American standards are market-driven and on the opposite process [83]. In addition to the above differences, the results show that ASHC, ASHRERA, and Fitwel are not as diverse as WELL in terms of the number of development goals associated with policies and the corresponding policy types, which is a worthy reference for other standards.

These results suggest that the differences in the provisions of different standards may be influenced by regional features, such as urban construction foundation, public health risks, community characteristics, multi-agency cooperation foundation [86], construction concepts, urban development paths, and economic level.

Different countries and regions have different social, historical, economic, cultural, and climatic environments and need to face different current problems and fundamental conditions. When a country or a region is developing new healthy community standards, it is necessary to focus on formulating appropriate intervention measures based on regional features. Moreover, countries should fully consider and evenly take advantage of socio-ecological factors and conduct comprehensive interventions at multiple levels to obtain the most effective results. When selecting an existing healthy community assessment standard, it is necessary to examine whether it is adapted to regional features, as inappropriate assessment standards may not provide optimal guidance.

Different regional features require different interventions [87,88] to meet their current situations, and some interventions may not deliver operational effects when applied to different contexts. There might be challenges related to regional adaptability in the implementation of assessment standards. Therefore, the assessment standards should be set with appropriate interventions based on local characteristics to more accurately and effectively solve the urgent crises in the status of local public health and urban construction.

In this regard, we believe that the regionalization, typology, or hierarchy of the interventions will help to improve the regional relevance of the assessment standards and have an important impact on the non-homogenized construction of healthy communities. Regional precision and efficiency may be the next goals of the assessment standard.

6. Conclusions

This study set out to gain a deeper understanding of the potential effectiveness of healthy community assessment standards from a multidisciplinary perspective of socio-ecological factors and development goals. This study aimed to answer the questions of how the proportion of socio-ecological factors and their measures is distributed in the provisions, how the corresponding proportion of socio-ecological factors in the development goal sections is distributed, and what the characteristics of the distribution of socio-ecological factors and their measures in the detailed development goals are in different assessment standards. The WELL, Fitwel, ASHC, and ASHRERA standards were selected, and a contextual analysis was used with the two-dimensional analytical framework of “socio-ecological factors–development goals”. This study presents differences, limitations and potential optimization spaces for future applications.

This study found that, generally, the “socio-ecological factors–development goals” framework provides strong support for analyzing the multi-level impacts of assessment standards. Therefore, the following conclusions corresponding to the three research questions can be drawn: first, community and organization factors are mostly used in current standards, while interpersonal and policy factors should be strengthened to fully utilize their power. Second, as for the application in development goal sections, humanistic constructions have received less attention in the ASHC and ASHRERA compared with Fitwel. Third, differences in provisions due to regional features remind us to focus on locally adapted interventions when optimizing and promoting standards.

This study contributes a deeper insight into healthy community assessment standards from a socio-ecological perspective. By providing a “socio-ecological factors–development goals” two-dimensional analytical framework, this work offers a novel exploration of the potential effectiveness of standards on individual health promotion. The findings provide a new understanding of the characteristics and differences among selected standards, which are important references to standard-setters, government and local authorities, and standard-users. Based on the results of this study, we present the following recommendations:

- For standard-setters: When formulating new standards, it is necessary to consider and apply socio-ecological factors in a balanced manner to maximize the effectiveness of the intervention effect. The development goals that can improve local public health crises should be strengthened, and changing public health risks can be addressed by setting phased improvement goals, mid-term improvement goals, and long-term goals. While drawing on existing assessment standards, it is necessary to pay attention to the impact of local characteristics and fundamental conditions to improve regional adaptability and enhance the intervention effect.

- For government and local authorities: Coordinate the participation of multiple levels of society in the development of healthy communities; coordinate multiple departments to build professional standards and norms for different aspects of achieving a healthy community; promote multidisciplinary exchanges and cooperation through effective management mechanisms; and support and improve the development of healthy communities and the awareness and acceptance of community residents on healthy community assessment standards through policy incentives, thereby improving the implementation effect of standards.

- For standard-users: Select appropriate healthy community assessment standards. On this basis, fine-tune the standards in combination with regional or community characteristics. Leverage the strengths and address the weaknesses of different levels of socio-ecological factors and avoid the impact of short board effects.

However, this study still has some limitations. Four standards specifically developed for health and well-being were selected. However, the other standards integrate the assessment of health performance into existing sustainability assessment systems by adding provisions, which makes it difficult to distinguish health and well-being goal-oriented provisions. These standards have not yet been considered. This study mainly focused on the proportional distribution of socio-ecological factors, development goals, and provisions with distinctive features. Commonalities among standards are less discussed. This article focused on the social aspect of improving community health; however, economic and cultural aspects also influence residents’ health.

We call for future research to include community health assessment standards with added health performance assessment factors and identify the common parts of different standards. More importantly, future research should reveal the mechanism among standards from different multidisciplinary perspectives related to individual health promotion and explore how to improve interventions using intersectionality frameworks.

Author Contributions

J.Z.: Conceptualization, software, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition; Y.C.: writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration; P.Z.: software, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the State Scholarship Fund by the China Scholarship Council. The funding number is 202206280186.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the China Scholarship Council for funding the program. We are also grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions, which greatly improved the quality of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Definition and example of socio-ecological factors.

Table A1.

Definition and example of socio-ecological factors.

| Coding | Classification Definition * | Example ** |

|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Factor | Measures that can be used to improve personal health literacy and promote interpersonal activities | |

| The Disclosure And Delivery Of Health Information | Publicize and push air quality, weather information, test results, community activities and information, health knowledge, etc. | The community air pollution index is publicized in the community. |

| The Organization Of Group Activities | Organize or carry out education training, health talks, community activities, community meetings, etc. | Carry out publicity lectures on nutrition, physical and mental health, and publicize knowledge and concepts such as healthy diet, exercise and fitness, disease prevention and treatment, and mental health. |

| Services For Individuals Or Special Groups | Provide psychological medical care, emergency rescue, food supply, adverse environmental protection, and other services for individuals or special groups | Public and private homeless shelters, if present, provide connection services to find vacancies to accommodate all homeless persons. |

| Organization Factor | Rules and regulations that restrict or promote the construction and operation of a healthy community environment by the community property management department | |

| Organization and Management | Coordinate all resources through planning, organization, and governance to achieve a healthy and orderly development of the community | The community formulates a management system for garbage sorting and recycling and implements garbage sorting and recycling measures for garbage cans and garbage stations. |

| Operation and Maintenance | Measures to ensure the long-term good operation of the community, such as maintenance and repair, daily inspection, and resolution of faults and problems | Street cleaning, including cleaning of designated bike lanes, is performed regularly. |

| Guidance and Stimulation | Appropriate guidance through economic subsidies, rule-making, etc., to incentivize healthy behaviors or reduce health inequalities | Cooling assistance is provided for energy use in low-income households. |

| Monitoring and Testing | Monitoring and testing of community air quality, water environment, sound environment, etc. | Spot-check the quality of all kinds of water within the community, including domestic drinking water, direct drinking water, domestic hot water, swimming pool water, and non-traditional water sources, at least once a quarter. |

| Participation and Feedback | Residents’ participation and feedback on community development | A representative sample of at least 30% of occupants is surveyed annually(starting within one year of achieving 50% occupancy). |

| Community Factor | The requirements and objectives of public environment construction that affect the health and well-being of residents in community space | |

| General Requirements | General, broad requirements to guide the development of community space or environment | Landscaping measures should be taken to optimize the air environment in residential areas. |

| Specific Requirements | Ability to indicate the number or extent of requirements for the construction of a space or environment | Locate a minimum of two qualifying on-site non-residential uses within a 1/2 mile or 800 m walking distance from 51% of all residential buildings. |

| Equipment Requirements | Requirements for required monitoring systems, smart lighting systems, lighting equipment, promotional equipment, fitness equipment, urban furniture, etc. | The air-quality-monitoring system and air quality control equipment in the building of community public service facilities form an automatic control system and have the function of setting the limits of major pollutant concentration parameters. |

| Signage Requirements | Requirements for the content and location of the signage system such as non-smoking, noise emission, wayfinding, and public space usage information | No smoking signs should be set up within a radius of 10 m from the population of buildings in residential areas and the population attracted by fresh air, in residential-service-supporting buildings, as well as in public activity spaces such as patios, parks in residential areas, and children’s entertainment areas. |

| Policy Factor | Regional, industry/national, or international standards, guidelines, or regulations that are directly identified in the text to regulate or support the construction and operation of healthy communities | |

| International | The text directly indicates the internationally accepted guidelines or standards that need to be met | The community property management agency obtained ISO 14001 environmental management system certification. |

| National Or Industrial | The text directly indicates the national regulations or industry standards to be met | Monthly housing costs (including any utility allowances) paid by the tenant are in accordance with those set under the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program based on Section 42 of the Internal Revenue Code. |

| Regional | Local regulations or requirements to be met are directly indicated in the text | Installation of street trees and other green landscaping on project roadways in accordance with local street tree planting codes and requirements. |

* The socio-ecological factors are based on McLeroy et al.’s ecological model of health behavior [60]. The measures of each factor are summarized and extracted from the assessment provisions of the selected four assessment standards. ** Examples are from ASHC [31], ASHRERA [30], WELL [28] and Fitwel [40] assessment standards.

Table A2.

Definition and example of development goals.

Table A2.

Definition and example of development goals.

| Coding | Classification Definition * | Example ** |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Environments | The elements of the urban physical environment that affect the health of community residents include all provisions related to air quality, water environment, sound environment, light environment, and thermal environment | |

| Air | Targets and responses related to community air quality | Annual fourth-highest daily average 24 h concentration (99th percentile) PM2.5 less than 50 µg/m3. |

| Water | Objectives, requirements, and responses related to the water environment of the community | Conduct and demonstrate regular water quality testing that is conducted at all outdoor drinking water supplies and stations within the project boundary. |

| Sound | Objectives, requirements, and countermeasures related to the community acoustic environment | On the side of the traffic artery adjacent to the community, noise reduction measures such as setting up sound barriers and greening noise reduction are adopted. |

| Light | Objectives, requirements, and countermeasures related to the light environment of the community | In public activity areas, the color temperature of functional lighting should not be higher than 5000K, and the color tolerance should not be greater than 7SDCM; |

| Thermal Comfort | Objectives, requirements, and responses related to the thermal environment of the community | The average heat island intensity of the settlement shall not be higher than 3 °C. |

| Health Facilities | The elements of community infrastructure construction that affect the health of residents include road transportation, sports facilities, public spaces, healing environment, and food environment | |

| Roads and Transportation | It includes the design requirements of community roadways, fitness trails, cycling paths, parking lots, and the operation requirements of public transportation and bicycle-sharing operation requirements | In total, 75% of all buildings are within 400 m [0.25 mi] cycling distance of an existing or planned (with funding commitments) bicycle network that connects riders to at least 10 diverse uses that are within a 4.8 km [3 mi] cycling distance. |

| Sports Facilities | This includes requirements for indoor and outdoor sports venues, child- and senior-friendly spaces, pet activity spaces, and supporting fitness equipment | There are no less than 40 m2 of health clubs per 0.2 km community. |

| Public Spaces | It includes requirements for social spaces, gathering spaces, primary medical spaces, educational places, care centers, art and cultural venues, etc. | Cultural and sports activity centers are set up in the residential area, which can be used for residents to carry out team activities such as exhibitions, network information services, leisure and entertainment, education, and training. |

| Healing Environments | Contribute to residents’ mental healthcare services and restorative blue-green space and building space construction requirements | At least 75% of dwelling units are within 300 m [1000 ft] of public use green spaces that total a minimum size of 0.5 hectare [1.25 acre] or greater. |

| Food Environments | Requirements for community food sales, nutrition education, community farms, alcoholic environments, breastfeeding support, etc. | The sale of alcohol and alcoholic products to minors is prohibited. |

| Humanistic Constructions | The factors that affect the quality of community health construction include local characteristics, materials and safety, sanitation and cleanliness, and public services | |

| Local Character | It includes the local characteristics of the community and the construction of public art | Adoption of vernacular design strategies that honor local architecture and material supply. |

| Materials and Safety | It includes requirements related to the personal safety of residents, such as community construction materials, barrier-free systems, brownfield remediation, construction safety, and hazardous materials management | A plan that includes information on deposit locations and hours of operation governs the management of the following hazardous wastes, as defined per regulations/guidelines in Table A1. |

| Hygiene and Cleanliness | Garbage disposal, disinfection and cleaning of utilities and equipment, and beautification of the community | Residents and businesses are invited to participate in beautification initiatives that are held, at minimum, annually. |

| Public Services | It includes community conventions, volunteering, information surveys and feedback, health impact assessments, community recovery, participatory development, etc. | A representative sample of at least 30% of occupants is surveyed annually (starting within one year of achieving 50% occupancy). |

* The development goals are summarized and extracted from the assessment provisions of the selected four assessment standards. ** Examples are from ASHC [31], ASHRERA [30], WELL [28] and Fitwel [40] assessment standards.

References

- Xiao, J.; Zhao, J.; Luo, Z.; Liu, F.; Greenwood, D. The impact of built environment on mental health: A COVID-19 lockdown perspective. Health Place 2022, 77, 102889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelgrims, I.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Guyot, M.; Keune, H.; Nawrot, T.S.; Remmen, R.; Saenen, N.D.; Trabelsi, S.; Thomas, I.; Aerts, R.; et al. Association between urban environment and mental health in Brussels, Belgium. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, K.; Lee, S. Study on building plan for enhancing the social health of public apartments. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 1551–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, L.C.; Maxson, P.; Miranda, M.L. The Urban Built Environment and Associations with Women’s Psychosocial Health. J. Urban Health 2013, 90, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Feldman, P.J. Neighborhood problems as sources of chronic stress: Development of a measure of neighborhood problems, and associations with socioeconomic status and health. Ann. Behav. Med. 2001, 23, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Huo, Q.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, H. Comparative study of Chinese, European and ISO external thermal insulation composite system (ETICS) standards and technical recommendations. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 68, 105687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Moudon, A.V.; Lowe, M.; Cerin, E.; Boeing, G.; Frumkin, H.; Salvo, D.; Foster, S.; Kleeman, A.; Bekessy, S. What next? Expanding our view of city planning and global health, and implementing and monitoring evidence-informed policy. Lancet Glob. Health 2022, 10, e919–e926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, V.J.; Burke, T.J.; Curran, M.A. Interpersonal effects of health-related social control: Positive and negative influence, partner health transformations, and relationship quality. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 3986–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, J.; Thompson, S. Health and the built environment: Exploring foundations for a new interdisciplinary profession. J. Environ. Public Health 2012, 2012, 958175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frehlich, L.; Christie, C.D.; Ronksley, P.E.; Turin, T.C.; Doyle-Baker, P.; McCormack, G.R. The neighbourhood built environment and health-related fitness: A narrative systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, E.L.; Ige, J.O.; Pilkington, P.; Pinto, A.; Petrokofsky, C.; Burgess-Allen, J. Built and natural environment planning principles for promoting health: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Long, Y. Research on Healthy Neighborhood Evaluation System Based on the Combined Perspectives of Urban Planning and Public Health. Landsc. Archit. 2020, 2020, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Huang, L. Air Pollution and Human Health: Investigating the Moderating Effect of the Built Environment. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, S.; Hu, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, W. Effects of spatial scale on the built environments of community life circles providing health functions and services. Build. Environ. 2022, 223, 109492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ige-Elegbede, J.; Pilkington, P.; Orme, J.; Williams, B.; Prestwood, E.; Black, D.; Carmichael, L. Designing healthier neighbourhoods: A systematic review of the impact of the neighbourhood design on health and wellbeing. Cities Health 2022, 6, 1004–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Braver, N.; Lakerveld, J.; Rutters, F.; Schoonmade, L.; Brug, J.; Beulens, J. Built environmental characteristics and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2018, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]