Validation of Dynamic Natural Ventilation Protocols for Optimal Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Adaptive Comfort during the Winter Season in Subtropical-Climate School Buildings

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Energy Efficiency, Thermal Comfort and Indoor Air Quality

1.2. Indoor Air Quality

1.3. Recent Evolution of the Indoor Air Quality Standards

1.4. Minimum Natural Ventilation to Ensure Indoor Air Quality

1.5. Adaptive Thermal Comfort Model

1.6. Aims and Novelty of This Research

- Using Designbuilder simulations of this case study, obtain the WWeqR that provides enough air renovation to fulfill the CO2 levels under the required limits:

- ◦

- For the steady natural ventilation protocols (SNVPs), it describes a WWeqR that allows the achievement of the required CO2 all the time.

- ◦

- For the dynamic natural ventilation protocol (DNVP), it describes the functioning of the dynamic WWeqR according to the indoor CO2 sensors, to minimize the outdoor air infiltration.

- Using the monitoring data from this case study, validate the proper functioning of the WWeqR in buildings with manual operation, providing enough air renovation to fulfill the CO2 levels requested.

- Considering adaptive models, anticipate the TC outcomes that may arise due to the introduction of outdoor air without heat-recovery units.

- Provide a summary of design-and-management rules of thumb for scholar buildings in a subtropical climate to achieve acceptable IAQ during the operational time as an alternative to installing mechanical ventilation systems.

2. Materials and Methods

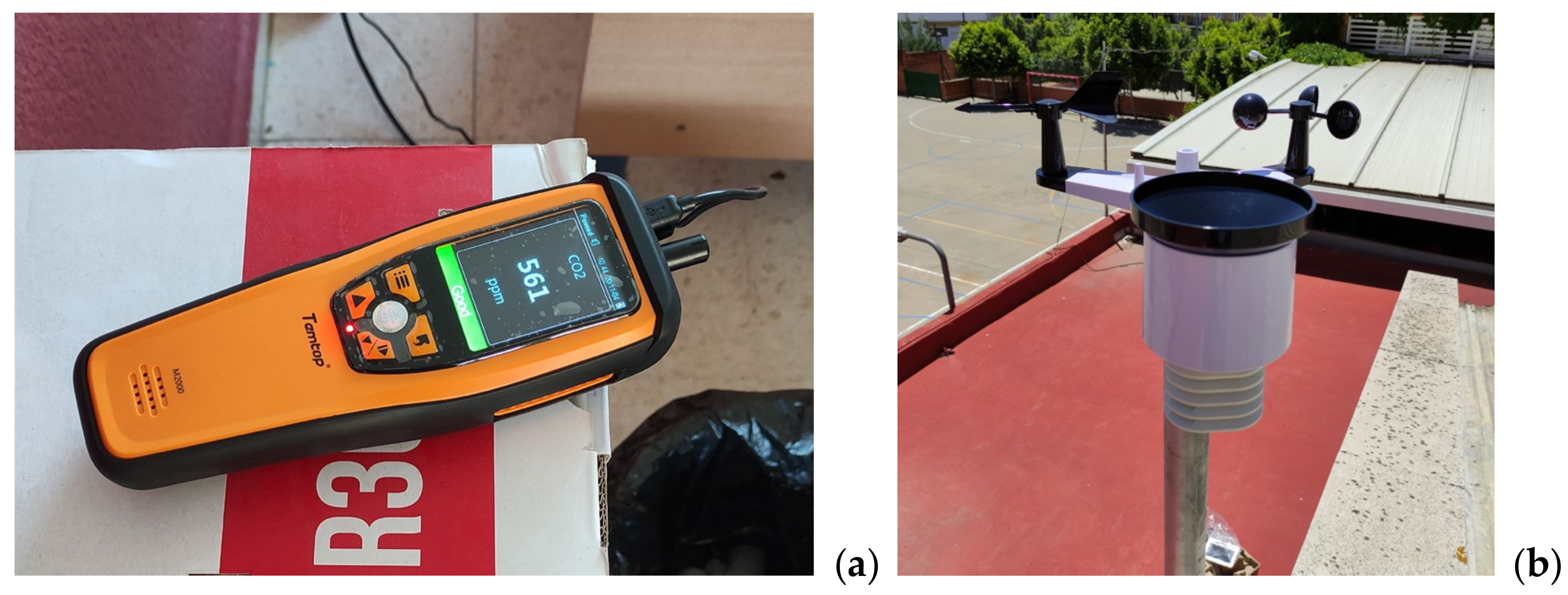

2.1. Monitoring Materials

- A TEMTOP M2000C 2nd CO2 Air Quality Monitor (orange). This includes a Sensair nondispersive infrared CO2 sensor, a sensirion SHT31-ARP sensor for temperature and relative humidity, and an NDIR CO2 sensor.

- A meteorological station, Froggit HP 1000SE PRO (white), includes a set of sensors to provide a full description of weather data in real time, as well as an indoor hydrothermal sensor able to measure humidity and temperature, and a central console. All of them are connected via radio at 868 MHz.

2.2. Simulation Software

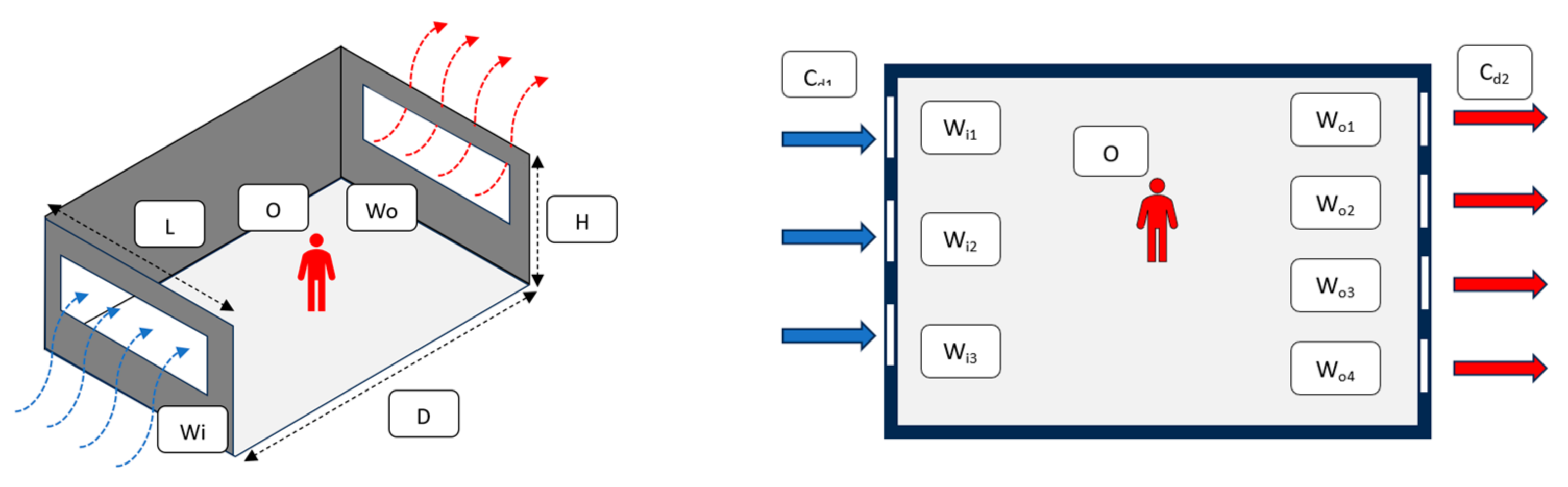

2.3. Methodology

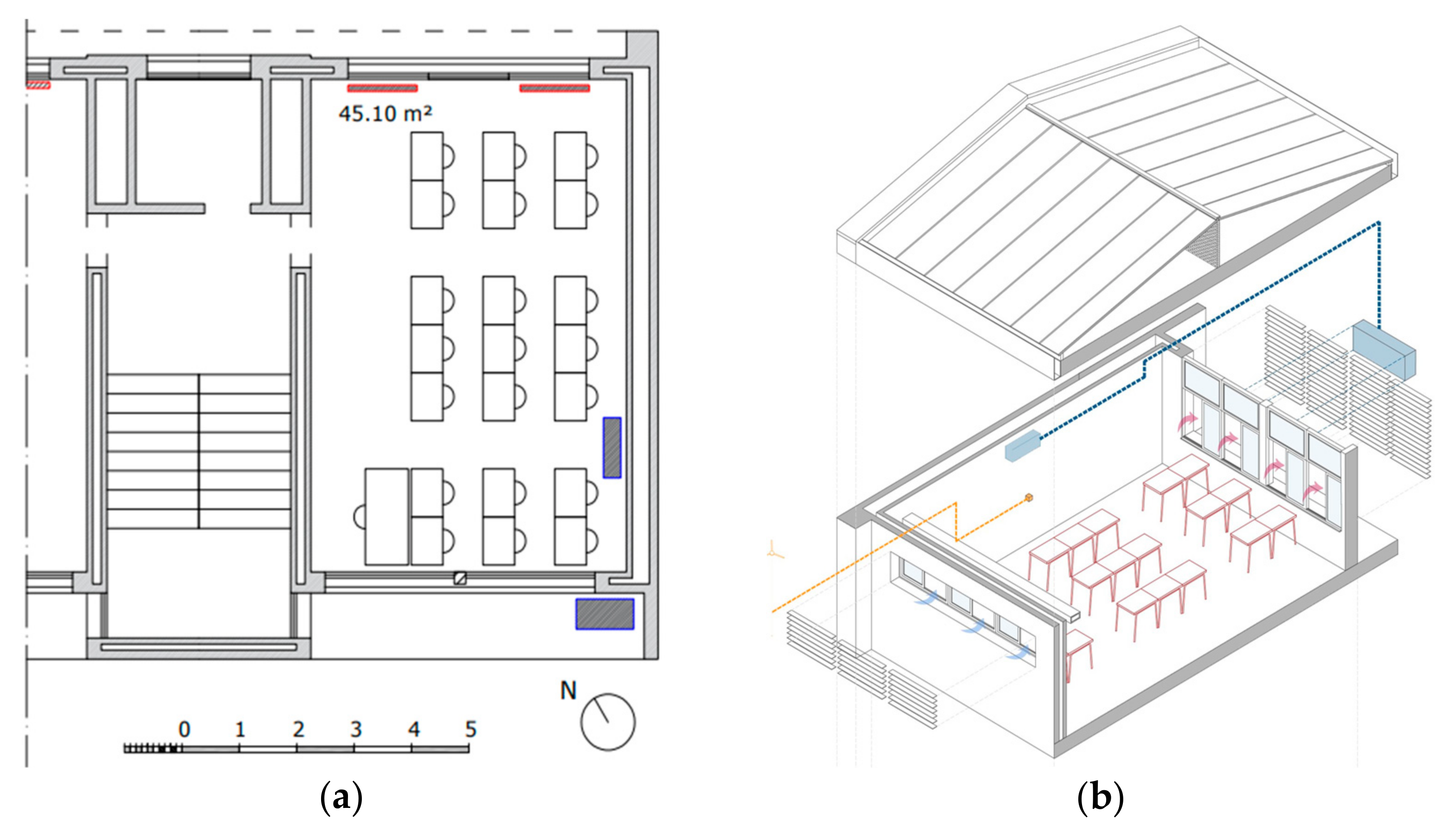

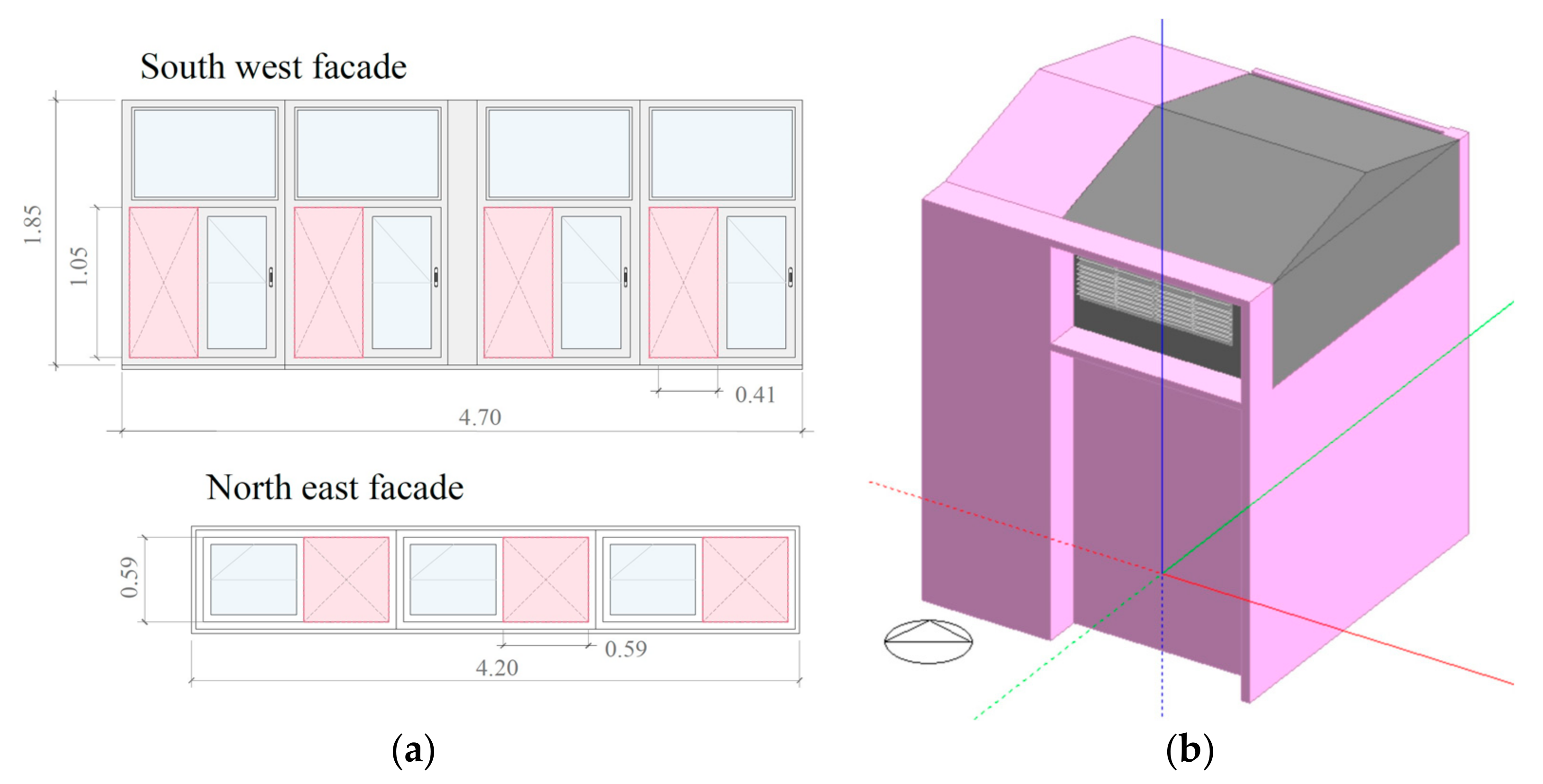

2.3.1. Case Study

- Figure 3a provides a layout with the position of the openings and the seats for the occupants. It also contains the position of the radiators (in red) and the heat pump (in blue). There is only 1 entrance to the classroom, which was always closed during the experimentations. The graphic scale and the north compass sign are included to classify the window openings as north/south. The north façade can be described as windward, while the south façade is considered leeward for the purposes of cross-ventilation analysis.

- Figure 3b provides an axonometric 3D view of the room, which adds extra information. Both windward and leeward openings include a set of solar-protection louvres, but during winter they are always set at a horizontal position. Therefore, it is considered that they have no influence on the ventilation process. Blue boxes describe the split heat-pump system. The yellow dot describes the approximate position of the IAQ monitoring devices (Figure 4a), while the yellow line describes the wireless connection with the central console (Figure 4b).

2.3.2. Natural-Ventilation Protocols

- CO2 concentration that can be obtained through CO2 sensors. They are cheap and easy to find and allow any worker in an educational building to have a real-time IAQ assessment. Even more, they can be connected remotely to cloud control via an app, so anyone can access the IAQ data report. In DesignBuilderTM the CO2 is obtained through virtual sensors, as described in Section 3.1.

- The opening factor described as a WWeqR, which can be manually or mechanically operated on site, following any of the suggested algorithm rules. It is also possible to model it in DesignBuilderTM through EMS scripting, as described in Section 3.1.

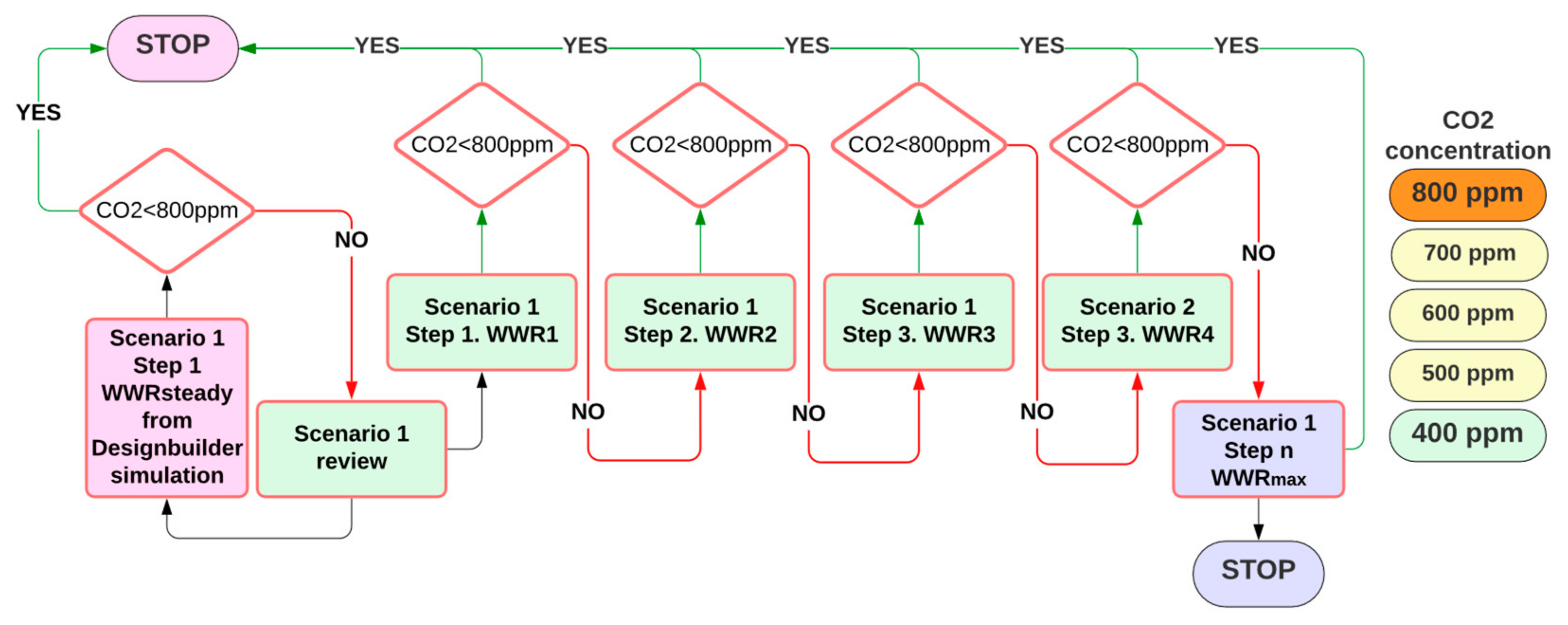

The Steady Natural-Ventilation Protocol

- The WWeqR is calculated via DesignbuilderTM simulations to maintain the CO2 concentration under 800 ppm.

- The WWeqR obtained is then applied on-site to the case study in scenario 1. If the CO2 concentration is below 800 ppm during this time, then the objective is accomplished and the WWeqR can be maintained while the rest of the conditions remain the same.

- On the contrary, if the CO2 concentration is not below 800 ppm, then the WWeqR must be revised in several steps, until it finally decreases to under 800 ppm.

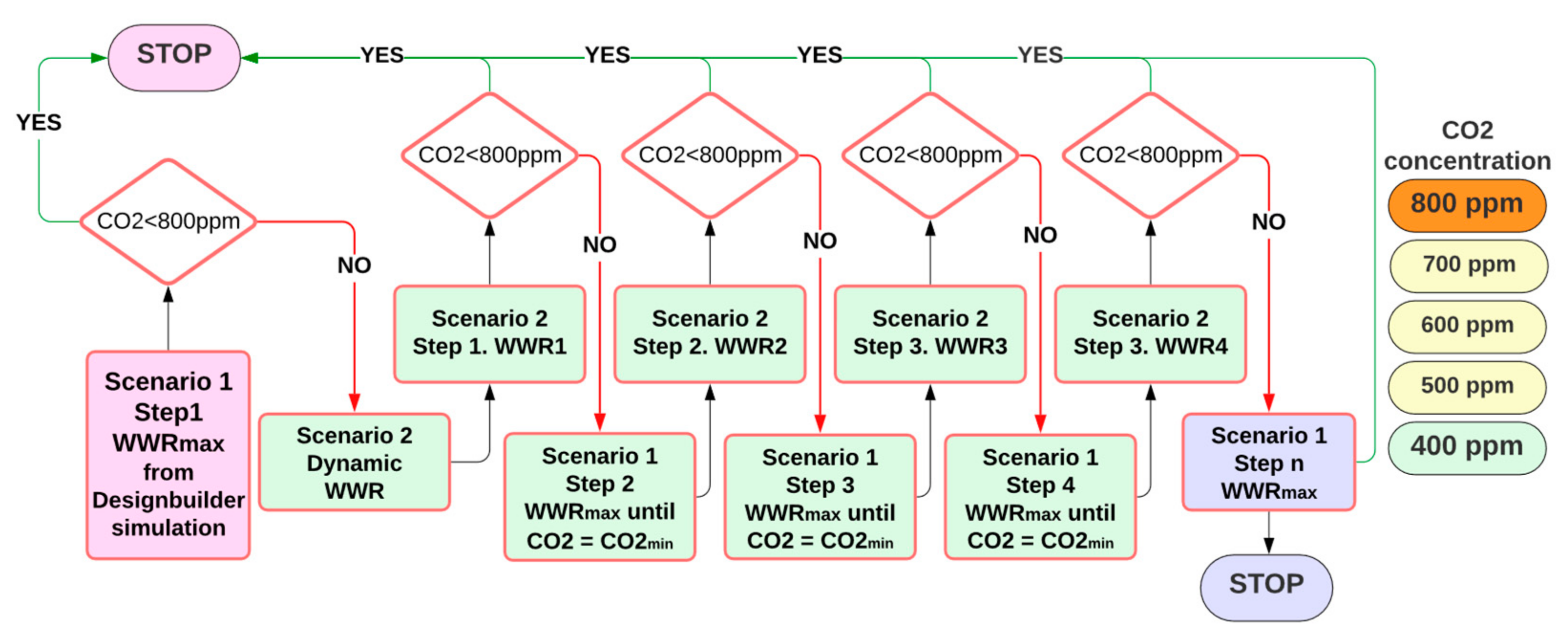

The Dynamic Natural-Ventilation Protocol

- In the first step, if the CO2 concentration is above 800 ppm, then windows must be fully opened to maintain the CO2 as low as possible.

- In the next step, when CO2 is below 800 ppm, the windows on both sides of the room will be opened according to a rising scale of WWeqR. The WWeqR is the average number of the WWR in the case of cross ventilation with different window sizes in the windward and leeward facade. For each of these openings, the CO2 concentration is measured. If the value remains below 800 ppm, then the process is stopped.

- If the CO2 rises above 800 ppm, then a full opening must be applied to quickly remove pollutants until the CO2 approaches the CO2 min. The CO2 is the result of the natural ventilation according to the maximum WWeqR of each case. Then, the CO2 concentration can be considered as around 550 ppm. The WWeqR is then set to the next higher value from the previous step. Again, if the value remains below 800 ppm, then the process is stopped. On the contrary, if the CO2 rises above 800 ppm, then the full opening scenario must be applied to repeat the flush process and the WWeqR applied for the next corresponding value.

- The process must be repeated in several steps until the CO2 remains below 800 ppm or, alternatively, the CO2 is above 800 ppm, but the windows remain fully open.

- In the next step, when CO2 is below 800 ppm, the windows in both sides are opened according to the increasing scale of WWeqR. The WWeqR is the average number of the WWR in the case of cross ventilation with different window sizes in the windward and leeward side. To ease the process for the school buildings management team, the WWeqR used came from an easy-to-remember opening width: 2-4-8-10-15-22 cm in each of the windows at the same time.

2.3.3. Opening Considerations for This Case Study

2.3.4. Calculation of Indoor Carbon Dioxide Concentration

3. Results

3.1. Simulation Stage

3.2. Monitoring Results

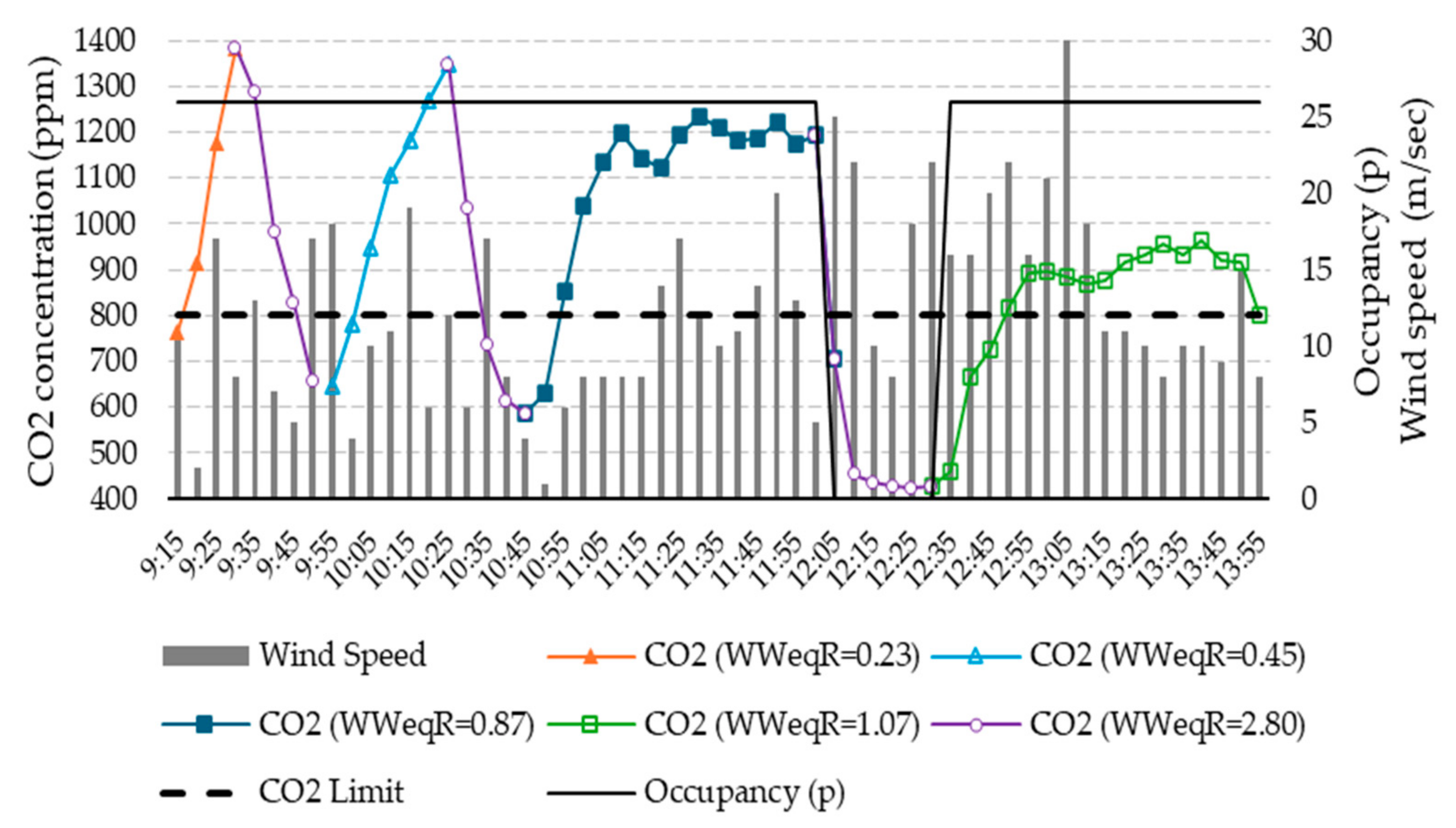

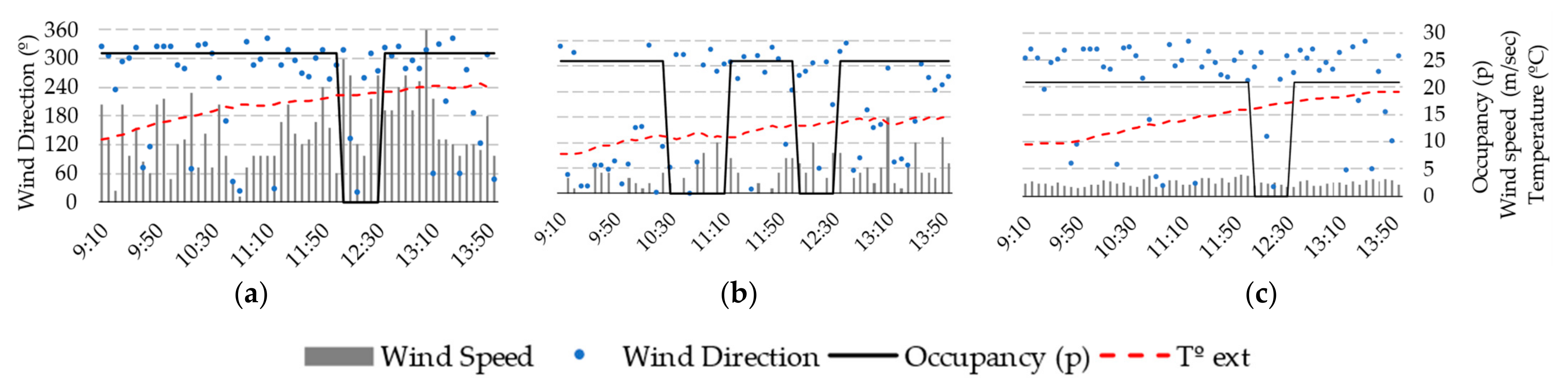

3.2.1. Monitoring of CO2 Concentration through Different WWeqRs with DNVP

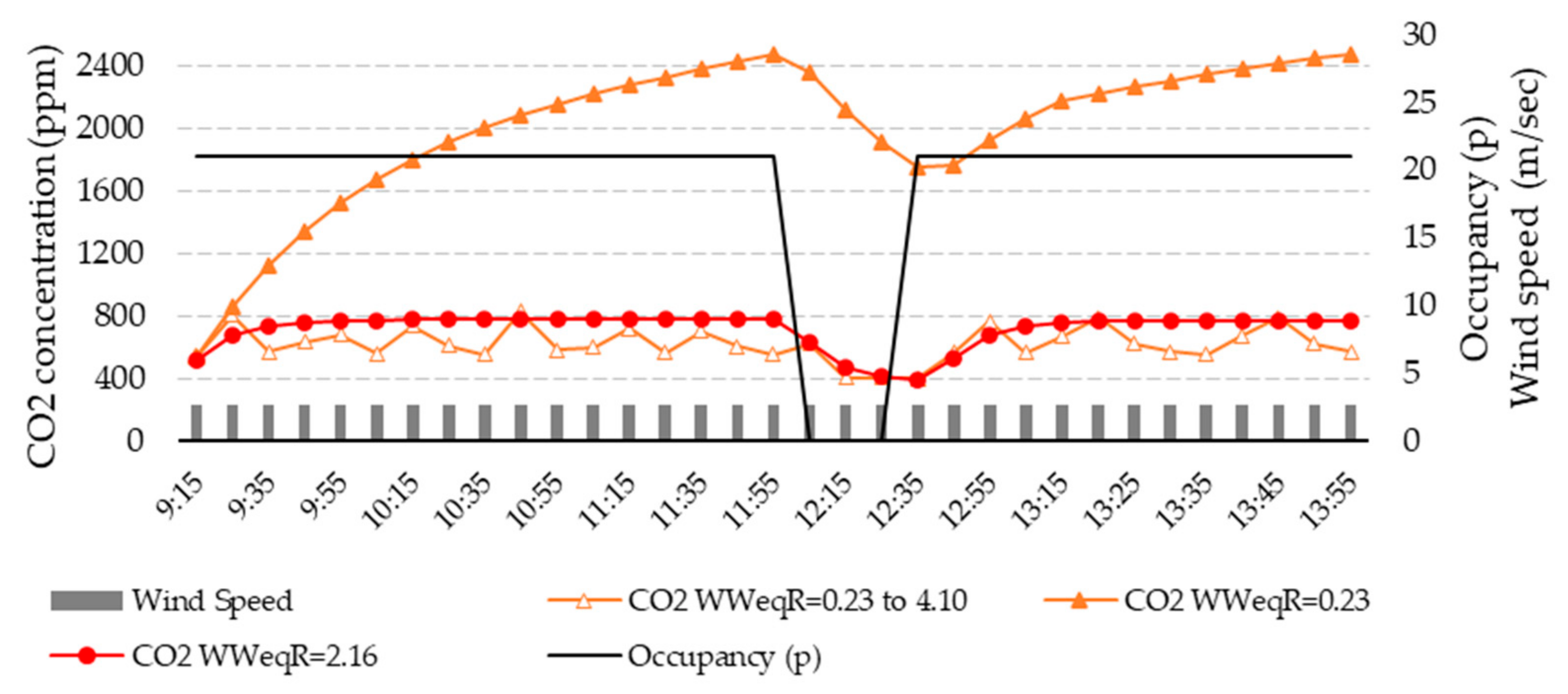

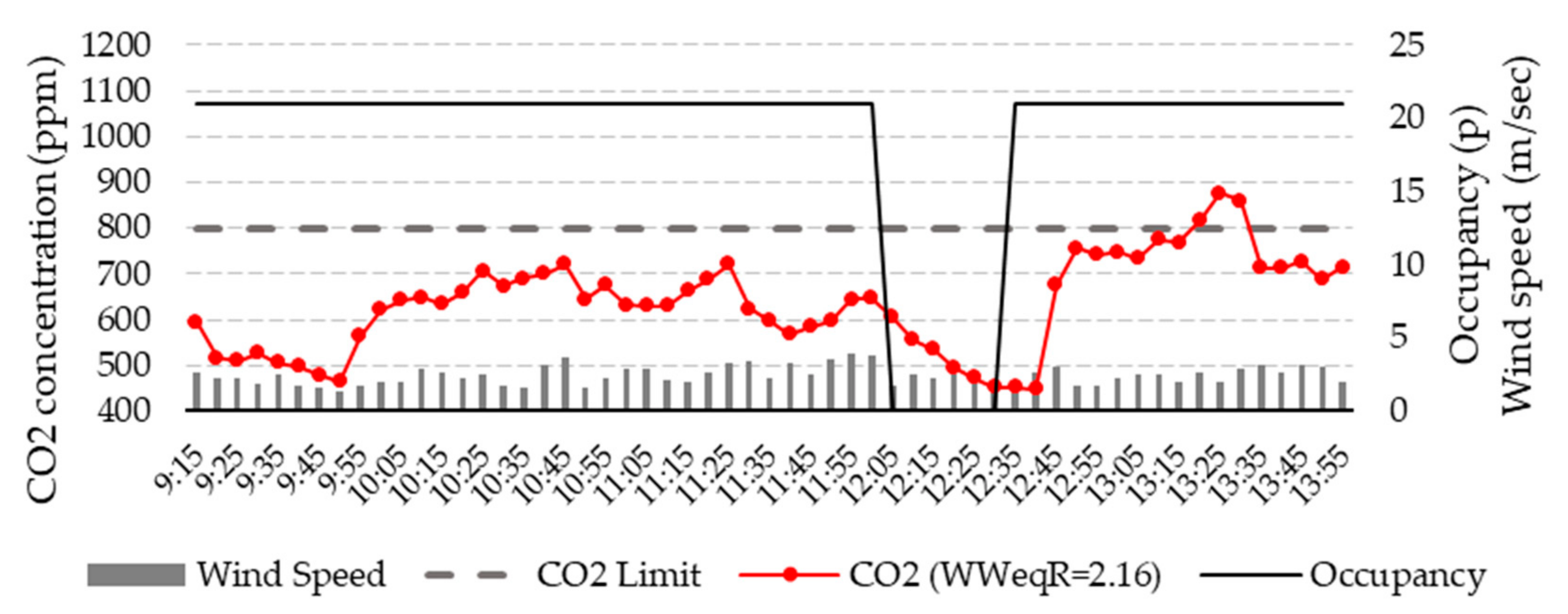

3.2.2. Monitoring of CO2 Concentration through 2.16% WWeqR with SNVP

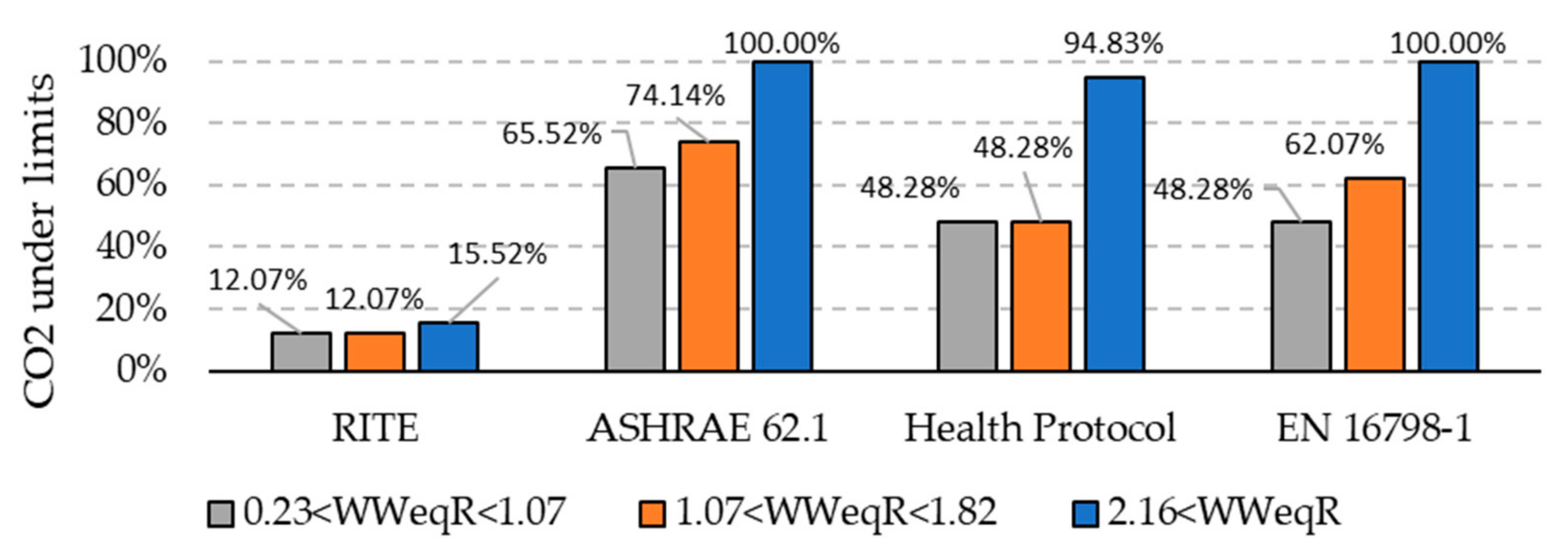

3.2.3. Summary of CO2 Assessment for DNVP and SNVP

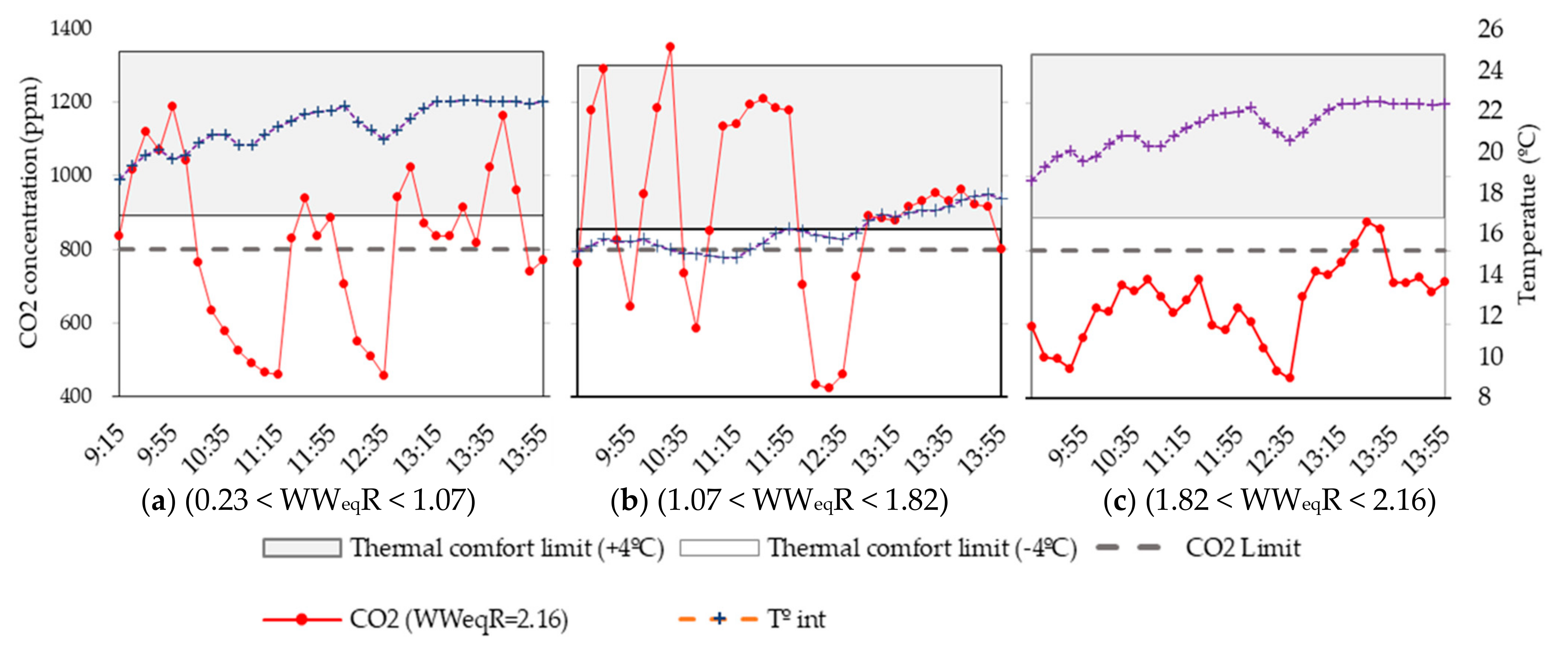

3.2.4. Temperature Monitoring during the Activation of the DNVP

4. Discussion

4.1. The Convenience of Natural vs. Mechanical Ventilation in Achieving Adequate IAQ

4.2. Dynamic vs. Steady Ventilation Controls

4.2.1. Simulation Results

4.2.2. Monitoring Results

4.3. Adaptive Comfort with Natural Ventilation

5. Conclusions

- Two different ventilation control algorithms, the SNVP and DNVP, were developed by the contribution of the software simulation to guarantee an acceptable IAQ, according to the most-accepted standards.

- For this case study simulation, the SNVP provides a 2.16% WWeqR to maintain CO2 below 800 ppm for a typical winter day in a subtropical climate, with 2.6 m/s wind and a northeast direction, when the occupancy is twenty-one students.

- The simulation of the DNVP anticipates that any WWeqR below 2.16% can maintain CO2 below 800 ppm if it increases the WWeqR to remove the unwanted CO2.

- The simulations, run in DesignbuilderTM, obtain a different grade of validation for the SNVP. The results, with a steady 2.16% WWeqR, shown in Figure 9, are similar to the monitored results in Figure 12. However, the accuracy of the simulated DNVP is reduced because of a lack of accuracy in the opening management. The DNVP simulation describes double the WWeqR modifications compared to the DNVP monitoring. The implementation of manual proceedings applied by the building staff seem to be less effective than mechanical controls. This may be considered in future studies.

- According to the results obtained in the monitoring process, the application of the SNVP maintains the CO2 concentration under 800 ppm during 100% of the operational time when the WWeqR was 2.16%, but failed during part of the study when the DNVP was applied. That suggests the need to implement better WWeqR controls to increase the efficiency of the protocols, as described in the simulation process.

- The CO2 limits proposed by RITE, 500 ppm, were only achieved for 15.52% of the time with the maximum WWeqR applied, which demonstrates the inadequacy of the natural ventilation to fulfil the standard.

- When the DNVP is used with a WWeqR below 2.16%, it can partially maintain CO2 under the required limits for those standards different to RITE. The analysis demonstrates compliance for 48.28% to 65.52% of the monitored time if the WWeqR is between 0.23 and 1.07, and a compliance for 48.28% to 74.14% of the monitored time if the WWeqR is between 1.07 and 1.82.

- During the monitoring process, the TC was also monitored to demonstrate the adequacy of the natural ventilation protocols with the adaptive TC described in the UNE-EN 16798 [27], for category III with a ±4 °C of adaptation. The application of the DNVP on a mild winter day achieved 100% TC during the full monitoring period. For schools in colder climatic zones, the TC could be compromised, if the rest of the conditions remain the same. However, passive-design principles could be used.

- Future versions of these ventilation protocols may include temperature sensors to improve the WWeqR control. Therefore, it could lead to an increase in energy efficiency to become nearly zero-energy buildings by means of passive-design techniques.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Huang, L.; Krigsvoll, G.; Johansen, F.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X. Carbon emission of global construction sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1906–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.; Goldberger, I.; Paciuk, M. Improving energy performance of school buildings while ensuring indoor air quality ventilation. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3261–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, A.S.; Melgar, S.G.; Márquez, J.M.A. Green building rating systems and the new framework level(s): A critical review of sustainability certification within Europe. Energies 2019, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisello, A.L.; Castaldo, V.L.; Taylor, J.E.; Cotana, F. The impact of natural ventilation on building energy requirement at inter-building scale. Energy Build. 2016, 127, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.M.; Santos, M.; Gomes, M.G.; Duarte, R. Impact of natural ventilation on the thermal and energy performance of buildings in a Mediterranean climate. Buildings 2019, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.L.; Huang, A.W.; Chen, W.A. Considerations on envelope design criteria for hybrid ventilation thermal management of school buildings in hot–humid climates. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 5834–5845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, S.G.; Cordero, A.S.; Rodríguez, M.V.; Márquez, J.M.A.; Control, T.E.P.; Técnica, E.; De Ingeniería, S.; De Huelva, U.; Huelva, C.P. Influence on indoor comfort and energy demand due to the application of COVID-19 natural ventilation protocols for schools at subtropical climate during winter season. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Architecture Research Frontiers and Ecological Environment (ARFEE 2020), Guangzhou, China, 18–20 December 2020; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García, D.; Bienvenido-Huertas, D.; Rubio-Bellido, C. Computational approach to extend the air-conditioning usage to adaptive comfort: Adaptive-Comfort-Control-Implementation Script. Autom. Constr. 2021, 131, 103900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, D.; Rubio-Bellido, C.; Tristancho, M.; Marrero, M. A comparative study on energy demand through the adaptive thermal comfort approach considering climate change in office buildings of Spain. Build. Simul. 2020, 13, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, S.G.; Cordero, A.S.; Rodríguez, M.V.; Andújar Márquez, J.M. Matching energy consumption and photovoltaic production in a retrofitted dwelling in subtropical climate without a backup system. Energies 2020, 13, 6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, S.G.; Bohórquez, M.Á.M.; Márquez, J.M.A. UhuMEB: Design, construction, and management methodology of minimum energy buildings in subtropical climates. Energies 2018, 11, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar, S.G.; Martínez Bohórquez, M.Á.; Andújar Márquez, J.M. Uhumebr: Energy refurbishment of existing buildings in subtropical climates to become minimum energy buildings. Energies 2020, 13, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, N.; Bastos, J.; Pereira, L.D.; Soares, A.; Amaral, A.R.; Asadi, E.; Rodrigues, E.; Lamas, F.B.; Monteiro, H.; Lopes, M.A.R.; et al. A review on current advances in the energy and environmental performance of buildings towards a more sustainable built environment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 845–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, R.L.; Liao, W.J.; Chen, W.A. Optimization of energy use and academic performance for educational environments in hot-humid climates. Build. Environ. 2022, 222, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Regional Office for Europe. WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Selected Pollutants; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mannan, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Indoor air quality in buildings: A comprehensive review on the factors influencing air pollution in residential and commercial structure. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateson, T.F.; Schwartz, J. Children’s response to air pollutants. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health Part A Curr. Issues 2008, 71, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanovica, S.; Zemitis, J.; Bogdanovics, R. The Effect of CO2 Concentration on Children’s Well-Being during the Process of Learning. Energies 2020, 13, 6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabile, L.; Dell’Isola, M.; Russi, A.; Massimo, A.; Buonanno, G. The effect of natural ventilation strategy on indoor air quality in schools. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 595, 894–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; Llanos, J.; Escandón, R.; Sendra, J.J. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on indoor air quality and thermal comfort of primary schools in winter in a mediterranean climate. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofia, D.; Giuliano, A.; Gioiella, F.; Barletta, D.; Poletto, M. Modeling of an air quality monitoring network with high space-time resolution. Comput. Aided Chem. Eng. 2018, 43, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Amarillo, S.; Fernández-Agüera, J.; González, M.M.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T. Overheating in schools: Factors determining children’s perceptions of overall comfort indoors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawska, L.; Milton, D.K. It Is Time to Address Airborne Transmission of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 2311–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Jimenez, J.L. Exhaled CO2 as a COVID-19 infection risk proxy for different indoor environments and activities. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad Gobierno de España. Medidas de Prevención, Higiene y Promoción de l Salud Frente a COVID-19 Para Centros Educativos en el Curso 2020–2021. Available online: http://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/dam/jcr:7e90bfc0-502b-4f18-b206-f414ea3cdb5c/medidas-centros-educativos-curso-20-21.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Chatzidiakou, L.; Archer, R.; Beale, V.; Bland, S.; Carter, H.; Castro-Faccetti, C.; Edwards, H.; Finneran, J.; Hama, S.; Jones, R.L.; et al. Schools’ air quality monitoring for health and education: Methods and protocols of the SAMHE initiative and project. Dev. Built Environ. 2023, 16, 100266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16798-1:2020; Energy Performance of Buildings—Ventilation for Buildings—Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustic. European Standard: Newark, DE, USA, 2020. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/b4f68755-2204-4796-854a-56643dfcfe89/en-16798-1-2019 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 62.1-2019; Ventilation for Acceptable Indoor Air Quality. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2019.

- RITE. Reglamento de Instalaciones Térmicas en los Edificios. Bol. Estado 2021, 71, 33748–33793. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2021/03/23/178 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- International Well Building Institute. The Well Building Standard V2; International WELL Building Institute (IWBI): New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kapsalaki, M. ASHRAE Position Document on Indoor Carbon Dioxide; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Persily, A.; de Jonge, L. Carbon dioxide generation rates for building occupants. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, S.; O’Brien, W. Natural ventilation usability under climate change in Canada and the United States. Build. Res. Inf. 2021, 49, 367–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daemei, A.B.; Limaki, A.K.; Safari, H. Opening Performance Simulation in Natural Ventilation Using Design Builder (Case Study: A Residential Home in Rasht). Energy Procedia 2016, 100, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Kobayashi, T.; Yamanaka, T.; Sandberg, M. A literature review of cross ventilation in buildings. Energy Build. 2023, 291, 113143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecle, A.; Bitsuamlak, G.T.; Jiru, T.E. Wind-driven natural ventilation in a low-rise building: A Boundary Layer Wind Tunnel study. Build. Environ. 2013, 59, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathirana, S.; Rodrigo, A.; Halwatura, R. Effect of building shape, orientation, window to wall ratios and zones on energy efficiency and thermal comfort of naturally ventilated houses in tropical climate. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2019, 10, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Weerasuriya, A.U.; Wang, J.; Li, C.Y.; Chen, Z.; Tse, K.T.; Hang, J. Cross-ventilation of a generic building with various configurations of external and internal openings. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.; Piette, M.A.; Han, J.M.; Wu, W.; Malkawi, A. Optimization of Window Positions for Wind-Driven Natural Ventilation Performance. Energies 2020, 13, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dear, R.; Schiller Brager, G. The adaptive model of thermal comfort and energy conservation in the built environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2001, 45, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2013; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-conditioning Engineers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- Bienvenido-Huertas, D.; de la Hoz-Torres, M.L.; Aguilar, A.J.; Tejedor, B.; Sánchez-García, D. Holistic overview of natural ventilation and mixed mode in built environment of warm climate zones and hot seasons. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DesignBuilder Software Ltd. DesignBuilder v7. Available online: https://designbuilder.co.uk/download/documents (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Berkeley, L.; Ridge, O.A.K.; Ut-battelle, M.B.Y.; For, A.; Energy, S.; Or, D.; In, T.; Form, A.N.Y.; By, O.R.; Means, A.N.Y.; et al. Application Guide for EMS; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2020.

- Schulze, T.; Eicker, U. Controlled natural ventilation for energy efficient buildings. Energy Build. 2013, 56, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Zeitschrift 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Engineering Reference—EnergyPlus™ Version 22.1.0 Documentation. 2022. 1774p. Available online: https://energyplus.net/assets/nrel_custom/pdfs/pdfs_v22.1.0/EngineeringReference.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Department of Energy’s (DOE) Building Technologies Office (BTO). Weather Data Download—Sevilla 083910 (SWEC). 2021. Available online: https://energyplus.net/weather-location/europe_wmo_region_6/ESP/ESP_Sevilla.083910_SWEC (accessed on 1 November 2021).

| Indicator | Protocol 2 | EN 16798-1 | ASHRAE 62.1 | WELL [30] | RITE [29] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | 800 ppm | 900 ppm | 1000 1 ppm | 900 ppm | 500 ppm |

| Main Parameters | Thermal Transmittance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Components | U (W/(m2K)) | ||

| Area | 49.60 m2 | Roof boards | Asbestos + air cavity | 3.077 |

| Height | 2.85 m | Ceiling | Concrete slab | 1.505 |

| Volume | 141.36 m3 | Flooring | Concrete slab | 1.505 |

| Occupancy | 26 pupils + teacher | External wall | 2 brick leaves | 1.390 |

| Occupancy ratio | 0428 p/m2 | Openings | Aluminum frame + 2 panes of glass (3 + 6 + 3) | 1.960 |

| Area | 49.60 m2 | Interior partition | 2 brick leaves | 1.425 |

| Specifications | TEMTOP M2000C 2nd | Froggit HP 1000SE PRO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor | Meteo station | Indoor sensor | |

| Operation frequency | 868 Mhz | 868 Mhz | |

| Temperature range | 0–50 °C | −40–60 °C, | −40–60 °C, |

| Temperature accuracy | ±0.3 °C | ±1 °C | ±1 °C |

| Relative humidity range | 0–90% | 1–99% | 1–99% |

| Relative humidity accuracy | ±3% | ±5% | ±5% |

| CO2 measuring range | 400–5000 ppm | ||

| CO2 accuracy | ±40 ppm | ||

| Windward/Northeast Windows 59 cm Height × 134 cm Wide | WWeqR 1 as Equation (1) | Leeward/Southwest Windows 105 cm Height × 107.5 cm Wide | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opening Conditions | Opening Conditions | |||||

| Wide (cm) | Wide (%) | WWR (%) | WWR (%) | Wide (%) | Wide (cm) | |

| 2 | 1.5% | 0.23% | 0.23% | 0.54% | 1.9% | 2 |

| 4 | 3.0% | 0.46% | 0.45% | 1.07% | 3.0% | 4 |

| 8 | 6.0% | 0.92% | 0.87% | 2.14% | 6.0% | 8 |

| 15 | 7.5% | 1.72% | 1.54% | 4.02% | 11.2% | 15 |

| 22 | 11.2% | 2.53% | 2.16% | 5.90% | 16.4% | 22 |

| 30 | 15.2% | 3.45% | 2.80% | 8.04% | 22.3% | 30 |

| 51 | 47.7% | 6.78% | 4.10% | 10.99% | 44.0% | 41 |

| WWeqR | Protocol | 09:10 09:30 | 09:30 10:00 | 10:00 10:30 | 10:30 11:00 | 11:00 11:30 | 11:30 12:00 | 12:00 12:30 | 12:30 13:00 | 13:00 13:30 | 13:30 14:00 | Peak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.23 (%) | DNVP | 608 | 643 | 637 | 641 | 634 | 620 | 485 | 579 | 627 | 640 | 641 |

| * SNVP | 623 | 1274 * | 1764 * | 2063 * | 2261 * | 2414 * | 2136 * | 1827 * | 2191 * | 2416 * | 2416 * | |

| 0.45 (%) | DNVP | 599 | 642 | 632 | 628 | 630 | 632 | 477 | 581 | 632 | 642 | 642 |

| * SNVP | 613 | 1180 * | 1532 * | 1707 * | 1807 * | 1880 * | 1539 * | 1236 * | 1618 * | 1813 * | 1880 * | |

| 0.87 (%) | DNVP | 593 | 652 | 645 | 647 | 644 | 642 | 427 | 573 | 644 | 649 | 649 |

| * SNVP | 596 | 1037 * | 1229 * | 1292 * | 1320 * | 1340 * | 984 * | 790 * | 1173 * | 1302 * | 1340 * | |

| 1.54 (%) | DNVP | 565 | 653 | 667 | 680 | 668 | 662 | 431 | 574 | 636 | 636 | 680 |

| * SNVP | 569 | 861 * | 927 * | 937 * | 940 * | 943 * | 641 * | 602 * | 893 * | 937 * | 940 * | |

| 2.16 (%) | DNVP | 543 | 729 | 750 | 752 | 755 | 757 | 469 | 544 | 745 | 757 | 757 |

| SNVP | 547 | 749 | 773 | 774 | 774 | 774 | 525 | 551 | 758 | 771 | 774 | |

| 4.10 (%) | DNVP | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SNVP | 544 | 544 | 544 | 544 | 544 | 544 | 481 | 418 | 532 | 544 | 544 |

| WWeqR | Protocol | 09:10 09:30 | 09:30 10:00 | 10:00 10:30 | 10:30 11:00 | 11:00 11:30 | 11:30 12:00 | 12:00 12:30 | 12:30 13:00 | 13:00 13:30 | 13:30 14:00 | Peak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.23–1.07 18th-Nov. | DNVP | 964 * | 880 * | 1106 * | 570 | 1139 * | 1201 * | 607 | 666 | 896 * | 915 * | 1201 * |

| 1.07–1.82 26th-Nov. | DNVP | 880 * | 1114 * | 839 * | 538 | 562 | 888 * | 655 | 767 | 877 * | 912 * | 1114 * |

| 2.16 17th-Dec. | DNVP | 529 | 503 | 652 | 684 | 661 | 603 | 552 | 588 | 787 | 711 | 787 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cordero, A.S.; Melgar, S.G.; Márquez, J.M.A. Validation of Dynamic Natural Ventilation Protocols for Optimal Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Adaptive Comfort during the Winter Season in Subtropical-Climate School Buildings. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114651

Cordero AS, Melgar SG, Márquez JMA. Validation of Dynamic Natural Ventilation Protocols for Optimal Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Adaptive Comfort during the Winter Season in Subtropical-Climate School Buildings. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(11):4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114651

Chicago/Turabian StyleCordero, Antonio Sánchez, Sergio Gómez Melgar, and José Manuel Andújar Márquez. 2024. "Validation of Dynamic Natural Ventilation Protocols for Optimal Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Adaptive Comfort during the Winter Season in Subtropical-Climate School Buildings" Applied Sciences 14, no. 11: 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114651

APA StyleCordero, A. S., Melgar, S. G., & Márquez, J. M. A. (2024). Validation of Dynamic Natural Ventilation Protocols for Optimal Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Adaptive Comfort during the Winter Season in Subtropical-Climate School Buildings. Applied Sciences, 14(11), 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14114651