Challenges and Perspectives for Integrating Quinoa into the Agri-Food System

Abstract

1. Quinoa’s Superiority over Other Cereals

1.1. Extraordinary Nutritional Properties

| Quinoa | Wheat | Maize | Rice | Publication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional profile | |||||

| Crude protein (% dry weight) | 12–20 | 12 | 8.7 | 7.3 | [19,20,21,22] |

| Total fat (% dry weight) | 5 | 1.6 | 3.9 | 0.4 | |

| Fiber (% dry weight) | 5–10 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 0.4 | |

| Total Carbohydrates (% dry weight) | 59.7 | 70 | 70.9 | 80.4 | |

| Gluten presence | Gluten free | 12–14% | Gluten free | Gluten free | |

| Glycemic index | 53 | 43 | 66 | 56 | |

| Minerals (mg/100 g dry weight) | |||||

| Magnesium | 249.6 | 169.4 | 137.1 | 73.5 | [23,24] |

| Calcium | 148.7 | 50.3 | 17.1 | 6.9 | |

| Iron | 13.2 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 0.7 | |

| Potassium | 926.7 | 578.3 | 377.1 | 118.3 | |

| Phosphorus | 383.7 | 467.7 | 292.6 | 137.8 | |

| Vitamins | |||||

| Niacin | 0.5–0.7 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 | [25] |

| Thiamine | 0.2–0.4 | 0.45–0.49 | 0.42 | 0.06 | |

| Folic Acid | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| Riboflavin | 0.2–0.3 | 0.17 | 0.1 | 0.06 | |

| Global production perspective | |||||

| Global market price (USD Tons−1) | 3580 | 205.76 | 143.91 | 376.00 | [26,27,28] |

| Grain yield (tons ha−1) | 0.76 | 3.49 | 5.87 | 4.76 | |

| Global production (million tons) | 147 | 770 | 1210 | 787 | |

| Global cultivated area (million ha) | 0.191 | 220.75 | 205.87 | 165.25 | |

| Genome organization | |||||

| Ploidy level | Allotetraploid | Tetraploid | Diploid | Diploid | [29,30] |

| Genome size | 1.5 Gb | ~17 Gb | 2.4 Gb | 2.4 Gb | |

| Chromosome no. | 36 | 42 | 20 | 24 | |

| Genes annotated | 62,512 | 3685 | 330 | 56,284 | |

| Abiotic stress tolerance | |||||

| Salinity stress | 150–750 mM NaCl | 125 mM NaCl | ModeratelySensitive to salt stress | 4–8 dSm−1 | [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39] |

| Heat stress | 35 °C | 32 °C | 36 °C | 40–45 °C | |

| Drought stress (water requirement) | 300–400 mm | 325–450 mm | 500–800 mm | 450–700 mm | |

1.2. Resistance to Adverse Environmental Conditions

1.3. Adaptability to Agro-Ecological Extremes

2. Challenges

2.1. High Weeds Infestation

2.2. Disease and Insect Pest Attack

| Disease/Insect Pest | Reporting Area | Effects | Growth Stage | Management | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western flower thrips (Frankliniella occidentalis, N. capsiformis) | Peru | Discoloration, distortion, premature drying, and shedding of leaves, flowers, and buds. | Late crop stages. | Methomyl + emamectin benzoate | [76] |

| Serpentine leaf minor (Liriomyza huidobrensis) | Italy | Premature leaf drop. | Middle crop maturation stages. | Methomyl + dimethoate | [76] |

| Potato aphid/aphid complex (Liriomyza huidobrensis, R. rufiabdominale, Myzus sp., and Macrosiphum sp.) | Italy, Peru | The development of sooty mold on the leaves. | 60 days after sowing. | Methomyl + dimethoate | [76] |

| Hemipteran Pests (L. hyalinus, N. simulans) | Italy, Peru | Seed- or leaf-feeding insects. | Grain-filling stage. | Dimethoate and methomyl | [79] |

| The noctuid complex (Helicoverpa, Copitarsia, Copitarsia, and Agrotis genera) | Chile, Argentina, Ecuador, and Colombia | Adult insects feed only on flowers’ nectar and other sweet secretions. Major damage has been observed during the flowering and physiological maturity stages. Because these pests enter into the panicle rachis leading it to break off, resulting in defoliation. Noctuid species also feed on developing grains. | The flowering and dough stages are the most sensitive stages for these insect attacks. | 1. Crop rotation. 2. Using light traps. 3. Using pheromones traps. 4. Preventive treatment (use of lime sulfur which effects the insects’ central nervous system). 5. Use of insecticide (spinosad). | |

| Quinoa moth complex (Eurysacca melanocampta, E. quinoae, and E. media) | Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Bolivia, and Peru | Photosynthetic area is reduced and first-generation larvae feed on the leaves’ parenchyma, roll leaves, and tender shoots, and destroy the developing inflorescences. Second-generation larvae damage the developed inflorescences, milk and dough stage grains, and mature grains, and ultimately cause a 15–60% reduction in yield. | Grain development and physiological maturity. | Use of spinosad as an eco-friendly insecticide. | [80,81] |

| Quinoa crop diseases | |||||

| Downy mildew | Argentina, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, Peru, Canada, Mexico, USA, Portugal, the Netherlands, France, UK, Sweden, Denmark, Italy, Kenya, and India | Primary effect of this disease is on the leaves but symptoms can also appear on the stems, inflorescences, branches, and on the grains. Initial symptoms appear on the leaves as small, irregular spots that may be chlorotic, yellow, grey, pink, orange, or red, depending on the plant color. | The initial developmental stages are mostly affected by this disease. Optimal conditions for downy mildew development are relative humidity (>80%) and temperatures of 18–22 °C. | 1. Genetic resistance. 2. Use of quality seed. 3. Use of eco-friendly fungicides (liquid extracts of horsetail and garlic). 4. Use of fungicide (metalaxyl). | [82] |

| Brown stalk rot | Peru, North America, and UK | A dark-brown lesion of 5–15 cm length appears on the stem and inflorescence portion. A shrunken stem, defoliation, and chlorosis are some other symptoms that may occur with this disease. Pathogens are mostly located in the stem and inflorescence. | Mostly occurs in the early developmental stages. | 1. Spray with carbendazim. 2. Mancozeb solution (70% mancozeb diluted to 1000 times). | [83] |

| Root rot | South American regions | The major symptom of this disease is black rot on the quinoa root. This causes the very low supply of water and nutrients to the roots and results in yellowing and ultimately death. | It is a soil-borne disease. | 1. Use of hymexazol (50% content is diluted 1200–1500 times). 2. Soaking of quinoa seed in thiram for ten hours before sowing. | [83] |

| Leaf spot | Major quinoa disease | High temperature favors this disease. Initially there is the formation of light spots on the leaves’ surface; later the leaves dry out and fall off. | Seed-borne disease. | Use of diniconazole powder (12.5% diniconazole is 30–40 g per 667 m2 for spray). | [47] |

| Gray mold | Cambridge | The stem and inflorescence of quinoa are mostly effected by this disease. | Stem elongation and panicle formation are the most sensitive stages. | Spray of iprodione diluted 1000–1500 times. | [83] |

| Quinoa Diamond Black Stem | Puno, Peru | Ascochyta leaf spot and stem necroses. | Stem-specific fungal agents. | Mancozeb and azoxystrobin fungicides. | [70,84] |

| Sclerotium | Cuzco, Peru | Whitish-to-grey stem lesions and sometimes conjugated ones. | Infected seeds and soil and crop debris. | Methyl benzimidazole carbamates and dicarboxamides. | [70] |

| Damping-off | Southern California, Nihon (Japan), and Peru | High moisture causes lesions on the quinoa leaves. High soil moisture causes the formation of diseased seedlings and wilting. | Seed- and soil- borne disease. | Phenyl-pyrroles (P.P. fungicides) and dimethylation inhibitors (DMIs). | [70] |

| Viral diseases | Peru, Bolivia | Chlorotic local lesions and severe systemic mosaic, leaf deformation, wilting, stunning and, finally, the collapse of the plants. | Seed-borne virus. | Seed sanitation. | [70,84] |

2.3. Stand Establishment

2.4. Saponin-Free Quinoa

2.5. Seed Longevity after Harvest

2.6. Photoperiod Sensitivity

2.7. Stem Resistance

2.8. Heat Stress at Reproductive Stage

2.9. Agronomic and Socio-Economic Constraints to Its Cultivation

3. Opportunities

3.1. Breeding Opportunities

Modern Biotechnology Techniques

3.2. Quality Seed Production (Management Practices)

3.3. Plant Genetic Resources (Seed Supply System in Developing Countries)

3.4. Dry Chain Technology for Seed Preservation

3.5. Seed and Grain Quality Evaluation

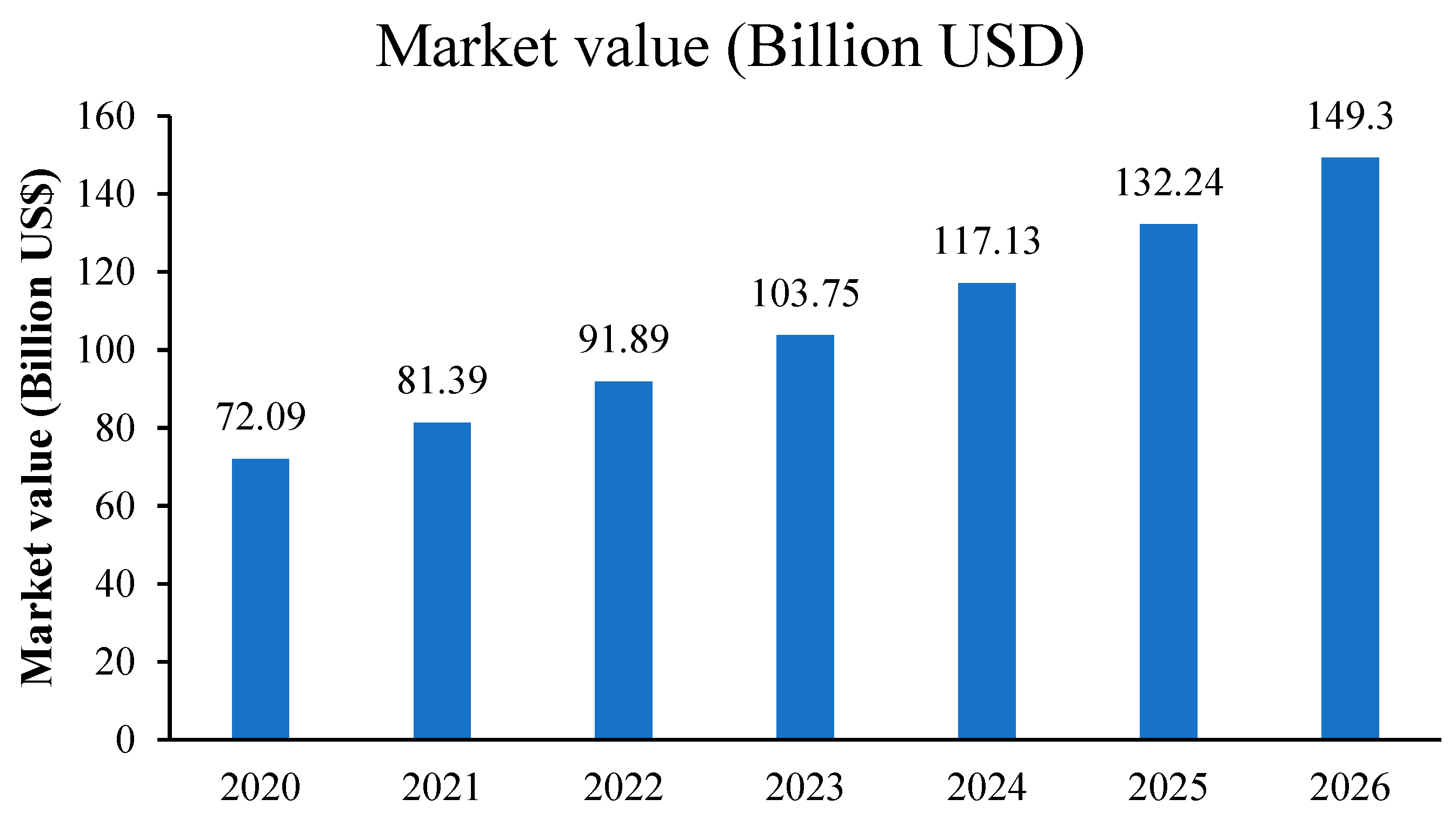

3.6. Quinoa Market

4. Conclusions and Future Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bhargava, A.; Shukla, S.; Srivastava, J.; Singh, N.; Ohri, D. Genetic diversity for mineral accumulation in the foliage of Chenopodium spp. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 118, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louafi, S.; Bazile, D.; Noyer, J.-L. Conserving and Cultivating Agricultural Genetic Diversity: Transcending Established Divides. In Cultivating Biodiversity to Transform Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 181–220. [Google Scholar]

- Thiam, E.; Allaoui, A.; Benlhabib, O. Quinoa productivity and stability evaluation through varietal and environmental interaction. Plants 2021, 10, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, S.; Bhargava, A.; Chatterjee, A.; Pandey, A.C.; Mishra, B.K. Diversity in phenotypic and nutritional traits in vegetable amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor), a nutritionally underutilised crop. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.S.; Redden, R.J.; Hatfield, J.L.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Hall, A.E. Crop Adaptation to Climate Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pulvento, C.; Bazile, D. Worldwide evaluations of quinoa—Biodiversity and food security under climate change pressures: Advances and perspectives. Plants 2023, 12, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelaziz, H.; Redouane, C.-A. Phenotyping the Combined Effect of Heat and Water Stress on Quinoa. In Emerging Research in Alternative Crops; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Bazile, D.; Fuentes, F.; Mujica, Á. Historical Perspectives and Domestication; CABI Publisher: Wallingford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Eisa, S.; Hussin, S.; Geissler, N.; Koyro, H. Effect of NaCl salinity on water relations, photosynthesis and chemical composition of Quinoa (‘Chenopodium quinoa’ Willd.) as a potential cash crop halophyte. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2012, 6, 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Jaikishun, S.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Song, S. Quinoa: In perspective of global challenges. Agronomy 2019, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolf, V.I.; Shabala, S.; Andersen, M.N.; Razzaghi, F.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Varietal differences of quinoa’s tolerance to saline conditions. Plant Soil 2012, 357, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, K.B.; Biondi, S.; Oses, R.; Acuña-Rodríguez, I.S.; Antognoni, F.; Martinez-Mosqueira, E.A.; Coulibaly, A.; Canahua-Murillo, A.; Pinto, M.; Zurita-Silva, A. Quinoa biodiversity and sustainability for food security under climate change. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 34, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, V.; Du, J.; Charrondière, U.R. Assessment of the nutritional composition of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Food Chem. 2016, 193, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.E.A. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.): Composition, chemistry, nutritional, and functional properties. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2009, 58, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, A.; Rana, T.S.; Shukla, S.; Ohri, D. Seed protein electrophoresis of some cultivated and wild species of Chenopodium. Biol. Plant. 2005, 49, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo-Carrasco, R.; Espinoza, C.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Nutritional value and use of the Andean crops quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) and kañiwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule). Food Rev. Int. 2003, 19, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, I.; Tenore, G.C.; Dini, A. Nutritional and antinutritional composition of Kancolla seeds: An interesting and underexploited andine food plant. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Shukla, S.; Ohri, D. Chenopodium quinoa—An Indian perspective. Ind. Crops Prod. 2006, 23, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Xue, S.; Sun, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, D.; Wei, J. Research Progress of Quinoa Seeds (Chenopodium quinoa Wild.): Nutritional Components, Technological Treatment, and Application. Foods 2023, 12, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Tsao, R. Phytochemicals in quinoa and amaranth grains and their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and potential health beneficial effects: A review. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61, 1600767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niro, S.; D’Agostino, A.; Fratianni, A.; Cinquanta, L.; Panfili, G. Gluten-free alternative grains: Nutritional evaluation and bioactive compounds. Foods 2019, 8, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster-Powell, K.; Miller, J.B. International tables of glycemic index. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 62, 871S–890S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazile, D.; Bertero, H.D.; Nieto, C. State of the Art Report on Quinoa around the World in 2013; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kozioł, M.J. Chemical composition and nutritional evaluation of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). J. Food Compos. Anal. 1992, 5, 35–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gálvez, A.; Miranda, M.; Vergara, J.; Uribe, E.; Puente, L.; Martínez, E.A. Nutrition facts and functional potential of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.), an ancient Andean grain: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 2541–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alandia, G.; Rodriguez, J.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Bazile, D.; Condori, B. Global expansion of quinoa and challenges for the Andean region. Glob. Food Secur. 2020, 26, 100429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maliro, M.F.; Abang, M.; Mukankusi, C.; Lung’aho, M.; Fenta, B.; Wanderi, S.; Kapa, R.; Okiro, O.A.; Koma, E.; Mwaba, C. Prospects for Quinoa Adaptation and Utilization in Eastern and Southern Africa: Technological, Institutional and Policy Considerations; Food & Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAOSTAT. Statistical Database; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahesh, H.; Shirke, M.D.; Singh, S.; Rajamani, A.; Hittalmani, S.; Wang, G.-L.; Gowda, M. Indica rice genome assembly, annotation and mining of blast disease resistance genes. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niroula, R.K.; Subedi, L.P.; Sharma, R.C.; Upadhyaya, M. Ploidy level and phenotypic dissection of Nepalese wild species of rice. Sci. World 2005, 3, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, I.; Rauf, S.; Basra, S.; Murtaza, G. Halopriming improves vigor, metabolism of reserves and ionic contents in wheat seedlings under salt stress. Plant Soil Environ. 2008, 54, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Hussain, M.; Wakeel, A.; Siddique, K.H. Salt stress in maize: Effects, resistance mechanisms, and management. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adolf, V.I.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Shabala, S. Salt tolerance mechanisms in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Environ. Exp. Bot. 2013, 92, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenda, T.; Wang, N.; Dong, A.; Zhou, Y.; Duan, H. Reproductive-Stage Heat Stress in Cereals: Impact, Plant Responses and Strategies for Tolerance Improvement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taaime, N.; Rafik, S.; El Mejahed, K.; Oukarroum, A.; Choukr-Allah, R.; Bouabid, R.; El Gharous, M. Worldwide development of agronomic management practices for quinoa cultivation: A systematic review. Front. Agron. 2023, 5, 1215441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, C.; Heibloem, M. Irrigation Water Management: Training Manual no. 3: Irrigation Water Needs. In Irrigation Water Management: Training Manual no. 3; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.I.; Saddique, Q.; Zhu, X.; Ali, S.; Ajaz, A.; Zaman, M.; Saddique, N.; Buttar, N.A.; Arshad, R.H.; Sarwar, A. Establishment of Crop Water Stress Index for Sustainable Wheat Production under Climate Change in a Semi-Arid Region of Pakistan. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRRI. Annual Report. Breaking New Ground. 2018. Available online: https://www.irri.org/annual-report-2018 (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies 2017–2018; Food Surveys Research Group: Beltsville, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Alam, M.M.; Roychowdhury, R.; Fujita, M. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9643–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrientos, E.; Carevic, F.; Delatorre, J. The sustainability of the southern highlands of Bolivia and its relationship with the expansion of quinoa growing areas. Idesia 2017, 35, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.; Eisa, S.; Hussin, S.; Prado, F.; Murphy, K.; Matanguihan, J. Quinoa: Improvement and Sustainable Production; World Agriculture Series; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Geerts, S.; Raes, D.; Garcia, M.; Vacher, J.; Mamani, R.; Mendoza, J.; Huanca, R.; Morales, B.; Miranda, R.; Cusicanqui, J. Introducing deficit irrigation to stabilize yields of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bascuñán-Godoy, L.; Reguera, M.; Abdel-Tawab, Y.M.; Blumwald, E. Water deficit stress-induced changes in carbon and nitrogen partitioning in Chenopodium quinoa Willd. Planta 2016, 243, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, A.; Gelani, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Heat tolerance in plants: An overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.-E.; Liu, F.; Jensen, C.R. Does root-sourced ABA play a role for regulation of stomata under drought in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Sci. Hortic. 2009, 122, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, F.; Abbas, G.; Saqib, M.; Amjad, M.; Farooq, A.; Ahmad, S.; Naeem, M.A.; Umer, M.; Khalid, M.S.; Ahmed, K. Comparative effect of salinity on growth, ionic and physiological attributes of two quinoa genotypes. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 57, 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, S.; Quispe, H.; Mujica, A. Quinoa: An alternative crop for saline soils in the Andes. In Scientist and Farmer-Partners in Research for the 21st Century; CIP Program Report; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 1999; Volume 2000, pp. 403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, C.; Read, J.J.; Abo-Kassem, E. Effect of mixed-salt salinity on growth and ion relations of a quinoa and a wheat variety. J. Plant Nutr. 2002, 25, 2689–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, F.E.; Boero, C.; Gallardo, M.R.A.; González, J.A. Effect of NaCl on growth germination and soluble sugars content in Chenopodium quinoa Willd. seeds. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 2000, 41, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, S.-E.; Monteros, C.; Corcuera, L.J.; Bravo, L.A.; Christiansen, J.L.; Mujica, A. Frost resistance mechanisms in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Basra, S.M.; Afzal, I.; Wahid, A.; Saddiq, M.S.; Hafeez, M.B.; Jacobsen, S.E. Yield potential and salt tolerance of quinoa on salt-degraded soils of Pakistan. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2019, 205, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, T.J.; Colmer, T.D. Salinity tolerance in halophytes. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, S.-E.; Monteros, C.; Christiansen, J.; Bravo, L.; Corcuera, L.; Mujica, A. Plant responses of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) to frost at various phenological stages. Eur. J. Agron. 2005, 22, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacher, J.-J. Responses of two main Andean crops, quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) and papa amarga (Solanum juzepczukii Buk.) to drought on the Bolivian Altiplano: Significance of local adaptation. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1998, 68, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, A. Interspecific and Intergeneric Hybridization in Chenopod Species; Department of Botany and Range Sciences, Brigham Young University: Provo, UT, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bazile, D. Le Quinoa, les Enjeux D’une Conquête; Agritrop Archive Ouverte du Cirad: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 1–112. [Google Scholar]

- Xiu-shi, Y.; Pei-you, Q.; Hui-min, G.; Gui-xing, R. Quinoa industry development in China. Cienc. Investig. Agrar. Rev. Latinoam. Cienc. Agric. 2019, 46, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, I.; Basra, S.M.A.; Rehman, H.U.; Iqbal, S.; Bazile, D. Trends and limits for quinoa production and promotion in Pakistan. Plants 2022, 11, 1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujica, A.; Jacobsen, S.; Izquierdo, J.; Marathee, J. Resultados de la Prueba Americana y Europea de la Quinua; FAO; UNA: Puno, Peru, 2001; Volume 51. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, S.-E. The worldwide potential for quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Food Rev. Int. 2003, 19, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oustani, M.; Mehda, S.; Halilat, M.T.; Chenchouni, H. Yield, growth development and grain characteristics of seven Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) genotypes grown in open-field production systems under hot-arid climatic conditions. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeroodi, A.r.S.; Mancinelli, R.; Radicetti, E. How Do Intensification Practices Affect Weed Management and Yield in Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Crop? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakabouki, I.; Karkanis, A.; Travlos, I.S.; Hela, D.; Papastylianou, P.; Wu, H.; Chachalis, D.; Sestras, R.; Bilalis, D. Weed flora and seed yield in quinoa crop (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) as affected by tillage systems and fertilization practices. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2015, 61, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.L.d.B.; Spehar, C.R.; Vivaldi, L. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) reaction to herbicide residue in a Brazilian Savannah soil. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2003, 38, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilalis, D.J.; Travlos, I.S.; Karkanis, A.; Gournaki, M.; Katsenios, G.; Hela, D.; Kakabouki, I. Evaluation of the allelopathic potential of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Rom. Agric. Res. 2013, 30, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Bilalis, D.; Karkanis, A.; Savvas, D.; Kontopoulou, C.-K.; Efthimiadou, A. Effects of fertilization and salinity on weed flora in common bean (‘Phaseolus vulgaris’ L.) grown following organic or conventional cultural practices. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2014, 8, 178–182. [Google Scholar]

- Colque-Little, C.; Abondano, M.C.; Lund, O.S.; Amby, D.B.; Piepho, H.-P.; Andreasen, C.; Schmöckel, S.; Schmid, K. Genetic variation for tolerance to the downy mildew pathogen Peronospora variabilis in genetic resources of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsen, S.; Mercado, V.; Ames, T.; Munk, L. Seed transmission of downy mildew (Peronospora farinosa f. sp. chenopodii) in quinoa and effect of relative humidity on seedling infection. Seed Sci. Technol. 2004, 32, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colque-Little, C.; Amby, D.B.; Andreasen, C. A review of Chenopodium quinoa (Willd.) diseases—An updated perspective. Plants 2021, 10, 1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, S.; Lübeck, M. Universally Primed-PCR indicates geographical variation of Peronospora farinosa ex. Chenopodium quinoa. J. Basic Microbiol. 2010, 50, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, J. The Chenopodium grains of the Andes: Inca crops for modern agriculture. Adv. Appl. Biol. 1984, 10, 145–216. [Google Scholar]

- Dřímalková, M. Mycoflora of Chenopodium quinoa Willd. seeds. Plant Prot. Sci. 2003, 39, 146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dřímalková, M.; Veverka, K. Seedlings damping-off of Chenopodium quinoa Willd. Plant Prot. Sci. 2004, 40, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alandia Borda, S.; Cardozo Gonzáles, A.; Gandarillas Santa Cruz, H.; Mujica Sanchez, Á.; Ortiz Romero, R.; Otazu Monzón, V.; Rea Clavijo, J. Quinoa y Kañiwa. Cultivos Andinos; Centro Internacional de Investigaciones para el Desarrollo: Bogotá, Colombia, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Cruces, L.; Peña, E.d.l.; De Clercq, P. Seasonal phenology of the major insect pests of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) and their natural enemies in a traditional zone and two new production zones of Peru. Agriculture 2020, 10, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, C.; Lagnaoui, A.; Esbjerg, P. Advances in the knowledge of quinoa pests. Food Rev. Int. 2003, 19, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaritopoulos, J.; Tzortzi, M.; Zarpas, K.; Tsitsipis, J.; Blackman, R. Morphological discrimination of Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae) populations feeding on Compositae. Bull. Entomol. Res. 2006, 96, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioli, P.; Colamartino, A.D.; Negri, M.; Limonta, L. Hemiptera and coleoptera on Chenopodium quinoa. Redia 2016, 99, 139–141. [Google Scholar]

- Valoy, M.E.; Bruno, M.A.; Prado, F.E.; González, J.A. Insectos asociados a un cultivo de quinoa en Amaicha del Valle, Tucumán, Argentina. Acta Zool. Lilloana 2011, 55, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.P.; Crespo, L.V.; Colmenarez, Y.C.; Lenteren, J.V. Biological Control in Bolivia. In Biological Control in Latin America and the Caribbean: Its Rich History and Bright Future; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2020; pp. 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mujica, A.; Suquilanda, M.; Chura, E.; Ruiz, E.; León, A.; Cutipa, S.; Ponce, C. Producción Orgánica de Quinua (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.); Universidad Nacional del Altiplano, FINCAGRO: Puno, Perú, 2013; p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Huang, H.; Li, G. Diseases Characteristic and Control Measurements for Chenopodium quinoa Willd. In Proceedings of the 2017 6th International Conference on Energy and Environmental Protection (ICEEP 2017), Zhuhai, China, 29–30 June 2017; pp. 305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Zhou, J.; Lv, H.; Qin, N.; Chang, F.J.; Zhao, X. Identification, pathogenicity, and fungicide sensitivity of Ascochyta caulina (Teleomorph: Neocamarosporium calvescens) associated with black stem on quinoa in China. Plant Dis. 2020, 104, 2585–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bois, J.-F.; Winkel, T.; Lhomme, J.-P.; Raffaillac, J.-P.; Rocheteau, A. Response of some Andean cultivars of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) to temperature: Effects on germination, phenology, growth and freezing. Eur. J. Agron. 2006, 25, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Parra, M.; Roa-Acosta, D.; Stechauner-Rohringer, R.; García-Molano, F.; Bazile, D.; Plazas-Leguizamón, N. Effect of temperature on the growth and development of quinoa plants (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.): A review on a global scale. Sylwan 2020, 164, 5. [Google Scholar]

- González, J.A.; Buedo, S.E.; Bruno, M.; Prado, F.E. Quantifying cardinal temperatures in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) cultivars. Lilloa 2017, 54, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M.; Hilal, M.; González, J.A.; Prado, F.E. Changes in soluble carbohydrates and related enzymes induced by low temperature during early developmental stages of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 2004, 161, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigstad, E.E.; Prado, F.E. A microcalorimetric study of Chenopodium quinoa Willd. seed germination. Thermochim. Acta 1999, 326, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufhammer, W.; Kaul, H.-P.; Kruse, M.; Lee, J.; Schwesig, D. Effects of sowing depth and soil conditions on seedling emergence of amaranth and quinoa. Eur. J. Agron. 1994, 3, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnitskiy, S.; Plaza, G. Physiology of recalcitrant seeds of tropical trees. Agron. Colomb. 2007, 25, 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Castellión, M.; Matiacevich, S.; Buera, P.; Maldonado, S. Protein deterioration and longevity of quinoa seeds during long-term storage. Food Chem. 2010, 121, 952–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comai, S.; Bertazzo, A.; Bailoni, L.; Zancato, M.; Costa, C.V.; Allegri, G. The content of proteic and nonproteic (free and protein-bound) tryptophan in quinoa and cereal flours. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1350–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.G.; Park, H.M.; Yoon, K.S. Analysis of saponin composition and comparison of the antioxidant activity of various parts of the quinoa plant (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, S.; Konishi, Y. Nutritional characteristics within structural part of quinoa seeds. J. Jpn. Soc. Nutr. Food Sci. 2003, 56, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gomez-Pando, L.R.; Aguilar-Castellanos, E.; Ibañez-Tremolada, M. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) Breeding. In Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Cereals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; Volume 5, pp. 259–316. [Google Scholar]

- Woldemichael, G.M.; Wink, M. Identification and biological activities of triterpenoid saponins from Chenopodium quinoa. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 2327–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanschewski, C.S.; Rey, E.; Fiene, G.; Craine, E.B.; Wellman, G.; Melino, V.J.; SR Patiranage, D.; Johansen, K.; Schmöckel, S.M.; Bertero, D. Quinoa phenotyping methodologies: An international consensus. Plants 2021, 10, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, I.; Tenore, G.C.; Trimarco, E.; Dini, A. Two novel betaine derivatives from Kancolla seeds (Chenopodiaceae). Food Chem. 2006, 98, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Chamorro, S. Quinoa. Encyclopedia of Food Science and Nutrition; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- El Hazzam, K.; Hafsa, J.; Sobeh, M.; Mhada, M.; Taourirte, M.; El Kacimi, K.; Yasri, A. An insight into saponins from Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.): A review. Molecules 2020, 25, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Ramirez, A.; Salas-Veizaga, D.M.; Grey, C.; Karlsson, E.N.; Rodriguez-Meizoso, I.; Linares-Pastén, J.A. Integrated process for sequential extraction of saponins, xylan and cellulose from quinoa stalks (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 121, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irigoyen, R.T.; Giner, S. Extraction kinetics of saponins from quinoa seed (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Int. J. Food Stud. 2018, 7, 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- De Santis, G.; Maddaluno, C.; D’Ambrosio, T.; Rascio, A.; Rinaldi, M.; Troisi, J. Characterisation of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) accessions for the saponin content in Mediterranean environment. Ital. J. Agron. 2016, 11, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Fuentes, I.; Vega-Gálvez, A.; Miranda, M.; Lemus-Mondaca, R.; Lozano, M.; Ah-Hen, K. A kinetic approach to saponin extraction during washing of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) seeds. J. Food Process Eng. 2013, 36, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, D.; Delatorre-Herrera, J.; Burrieza, H.; Bertero, H.D.; Martinez, E.A.; Delfino, I.; Moncada, S.; Bazile, D.; Castellión, M. Seed Physiology and Response to Germination Conditions. In State of the Art Report on Quinoa around the World in 2013; FAO/CIRAD: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spehar, C. Quinoa: An Alternative for Agricultural and Food Diversification; Embrapa Cerrados: Planaltina, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, R.; Hong, T.; Roberts, E.; Tao, K.-L. Low moisture content limits to relations between seed longevity and moisture. Ann. Bot. 1990, 65, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, R.; Hong, T.; Roberts, E. A low-moisture-content limit to logarithmic relations between seed moisture content and longevity. Ann. Bot. 1988, 61, 405–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenske, A.; Vasconcelos, E.S.d.; Egewarth, V.A.; Herzog, N.F.M.; Malavasi, M.d.M. Responses of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) seeds stored under different germination temperatures. Acta Sci. Agron. 2017, 39, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibar, H.; Sönmez, F.; Temel, S. Effect of storage conditions on nutritional quality and color characteristics of quinoa varieties. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2021, 91, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazile, D.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Verniau, A. The global expansion of quinoa: Trends and limits. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.M.; Bazile, D.; Kellogg, J.; Rahmanian, M. Development of a worldwide consortium on evolutionary participatory breeding in quinoa. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.E. The scope for adaptation of quinoa in Northern Latitudes of Europe. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2017, 203, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, V.I.; Goessling, J.W.; Duarte, B.; Caçador, I.; Liu, F.; Rosenqvist, E.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Combined effects of soil salinity and high temperature on photosynthesis and growth of quinoa plants (Chenopodium quinoa). Funct. Plant Biol. 2017, 44, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.; Akhtar, S.; Amjad, M.; Iqbal, S.; Jacobsen, S.E. Growth and physiological responses of quinoa to drought and temperature stress. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2016, 202, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunce, J.A. Variation in yield responses to elevated CO2 and a brief high temperature treatment in quinoa. Plants 2017, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojosa, L.; Matanguihan, J.B.; Murphy, K.M. Effect of high temperature on pollen morphology, plant growth and seed yield in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2019, 205, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendevis, M.; Sun, Y.; Rosenqvist, E.; Shabala, S.; Liu, F.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Photoperiodic effects on short-pulse 14C assimilation and overall carbon and nitrogen allocation patterns in contrasting quinoa cultivars. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014, 104, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, J.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Jørgensen, S. Photoperiodic effect on flowering and seed development in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B Soil Plant Sci. 2010, 60, 539–544. [Google Scholar]

- Bendevis, M.A.; Sun, Y.; Shabala, S.; Rosenqvist, E.; Liu, F.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Differentiation of photoperiod-induced ABA and soluble sugar responses of two quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) cultivars. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014, 33, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, P.X.; Zhang, B.; Hernandez, M.; Zhang, H.; Marcone, M.F.; Liu, R.; Tsao, R. Lipids, tocopherols, and carotenoids in leaves of amaranth and quinoa cultivars and a new approach to overall evaluation of nutritional quality traits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 12610–12619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Shukla, S.; Ohri, D. Genetic variability and interrelationship among various morphological and quality traits in quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Field Crops Res. 2007, 101, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Jeon, Y.A.; Cha, M.-K.; Park, S.; Cho, Y.-Y. Effects of Photoperiod, Light Intensity and Electrical Conductivity on the Growth and Yield of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) in a Closedtype Plant Factory System. Hortic. Sci. Technol. 2016, 34, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, R.; Bhandari, K.; Nayyar, H. Temperature stress and redox homeostasis in agricultural crops. Front. Environ. Sci. 2015, 3, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bita, C.E.; Gerats, T. Plant tolerance to high temperature in a changing environment: Scientific fundamentals and production of heat stress-tolerant crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2013, 4, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danielsen, S.; Bonifacio, A.; Ames, T. Diseases of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). Food Rev. Int. 2003, 19, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliani, A.; Hintermann, F.; Rojas, W.; Padulosi, S. Biodiversity of Andean Grains: Balancing Market Potential and Sustainable Livelihoods; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, S.E. The situation for quinoa and its production in southern Bolivia: From economic success to environmental disaster. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2011, 197, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerssen, T.M. Food sovereignty and the quinoa boom: Challenges to sustainable re-peasantisation in the southern Altiplano of Bolivia. Third World Q. 2015, 36, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitabile, E. Value Chain Analysis, Social Impact and Food Security. The Case of Quinoa in Bolivia; Università Degli Studi Roma Tre: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Apaza, D.; Carceres, G.; Estrada, R.; Pinedo, R. Catalogue of Commercial Varieties of Quinoa in Peru: A Future Planted Thousands of Years Ago; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejos Mamani, P.R.; Navarro-Fuentes, Z.; Ayaviri-Nina, D. Medio Ambiente y Produccion de Quinua: Estrategias de Adaptacion a los Impactos del Cambio Climatico; Fundacion Pieb: La Paz, Bolivia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rafik, S.; Chaoui, M.; Assabban, Y.; Jazi, S.; Choukr-Allah, R.; El Gharouss, M.; Hirich, A. Quinoa value chain, adoption, and market assessment in Morocco. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 46692–46703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katwal, T.B.; Bazile, D. First adaptation of quinoa in the Bhutanese mountain agriculture systems. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0219804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel, T.; Bertero, H.D.; Bommel, P.; Bourliaud, J.; Chevarría Lazo, M.; Cortes, G.; Gasselin, P.; Geerts, S.; Joffre, R.; Léger, F. The sustainability of quinoa production in southern Bolivia: From misrepresentations to questionable solutions. Comments on Jacobsen (2011, J. Agron. Crop Sci. 197: 390–399). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2012, 198, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narloch, U.; Pascual, U.; Drucker, A.G. Collective action dynamics under external rewards: Experimental insights from Andean farming communities. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2096–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Pando, L. Development of Improved Varieties of Native Grains through Radiation-Induced Mutagenesis. In Mutagenesis: Exploring Novel Genes and Pathways; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 760–766. [Google Scholar]

- Spehar, C.R.; Santos, R.L.d.B. Agronomic performance of quinoa selected in the Brazilian Savannah. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2005, 40, 609–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.E.; Christiansen, J. Some agronomic strategies for organic quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2016, 202, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.; Jacobsen, S.-E.; Bonifacio, A.; Murphy, K. A crossing method for quinoa. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3230–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, K.; Biondi, S.; Martínez, E.; Orsini, F.; Antognoni, F.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Quinoa—A model crop for understanding salt-tolerance mechanisms in halophytes. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2016, 150, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soplin Caballero, B. Estudios Preliminares Para la Inducción de Callos a Partir del Cultivo In Vitro de Anteras de Quinua (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.); Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina: Lima, Peru, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Quinoa, F. An Ancient Crop to Contribute to World Food Security. In Agroecological and Agronomic; Garcia, M., Condori, B., Castillo, C.D., Eds.; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaghi, F.; Bahadori-Ghasroldashti, M.R.; Henriksen, S.; Sepaskhah, A.R.; Jacobsen, S.E. Physiological characteristics and irrigation water productivity of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) in response to deficit irrigation imposed at different growing stages—A field study from Southern Iran. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2020, 206, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-L.; Wang, F.-X.; Shock, C.C.; Yang, K.-J.; Kang, S.-Z.; Qin, J.-T.; Li, S.-E. Influence of different plastic film mulches and wetted soil percentages on potato grown under drip irrigation. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 180, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, S.-E.; Jørgensen, I.; Stølen, O. Cultivation of quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa) under temperate climatic conditions in Denmark. J. Agric. Sci. 1994, 122, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, M.; Abou-Hussein, S.; El-Tohamy, W. Tomato yield, nitrogen uptake and water use efficiency as affected by planting geometry and level of nitrogen in an arid region. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 169, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gaelen, H.; Tsegay, A.; Delbecque, N.; Shrestha, N.; Garcia, M.; Fajardo, H.; Miranda, R.; Vanuytrecht, E.; Abrha, B.; Diels, J. A semi-quantitative approach for modelling crop response to soil fertility: Evaluation of the AquaCrop procedure. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 1218–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, T.L.; Johnson, B.L.; Schneiter, A.A. Row spacing, plant population, and cultivar effects on grain amaranth in the northern Great Plains. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimplinger, D.; Dobos, G.; Kaul, H.-P. Optimum crop densities for potential yield and harvestable yield of grain amaranth are conflicting. Eur. J. Agron. 2008, 28, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, J.; Mujica, A.; Marathee, J.; Jacobsen, S.-E. Horizontal, technical cooperation in research on quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.). Food Rev. Int. 2003, 19, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudebjer, P.; Meldrum, G.; Padulosi, S.; Hall, R.; Hermanowicz, E. Realizing the promise of neglected and underutilized species: Policy Brief; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2014; 12p. [Google Scholar]

- Chevarria-Lazo, M.; Bazile, D.; Dessauw, D.; Louafi, S.; Trommetter, M.; Hocdé, H. Quinoa and the Exchange of Genetic Resources: Improving the Regulation Systems; FAO/CIRAD: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, W.; Pinto, M.; Alanoca, C.; Gomez Pando, L.; Leon-Lobos, P.; Alercia, A.; Diulgheroff, S.; Padulosi, S.; Bazile, D. Quinoa Genetic Resources and Ex Situ Conservation; FAO/CIRAD: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bakhtavar, M.A.; Afzal, I. Climate smart Dry Chain Technology for safe storage of quinoa seeds. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groot, S.P.; de Groot, L.; Kodde, J.; van Treuren, R. Prolonging the longevity of ex situ conserved seeds by storage under anoxia. Plant Genet. Resour. 2015, 13, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carimentrand, A.; Baudoin, A.; Lacroix, P.; Bazile, D.; Chia, E. Quinoa Trade in Andean Countries: Opportunities and Challenges for Family. In State of the Art Report on Quinoa around the World in 2013; FAO/CIRAD: Rome, Italy, 2015; 589p. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.; Raes, D.; Allen, R.; Herbas, C. Dynamics of reference evapotranspiration in the Bolivian highlands (Altiplano). Agric. For. Meteorol. 2004, 125, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, S.; Sumnu, S. Physical Properties of Foods; Springer Science & Business Media: Greer, SC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prego, I.; Maldonado, S.; Otegui, M. Seed structure and localization of reserves in Chenopodium quinoa. Ann. Bot. 1998, 82, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tari, T.A.; Annapure, U.S.; Singhal, R.S.; Kulkarni, P.R. Starch-based spherical aggregates: Screening of small granule sized starches for entrapment of a model flavouring compound, vanillin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 53, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamed, N.T.; Singhal, R.S.; Kulkarni, P.R.; Pal, M. Physicochemical and functional properties of Chenopodium quinoa starch. Carbohydr. Polym. 1996, 31, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlopicka, J.; Pasko, P.; Gorinstein, S.; Jedryas, A.; Zagrodzki, P. Total phenolic and total flavonoid content, antioxidant activity and sensory evaluation of pseudocereal breads. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, C.M.; Cortez, G.; Repo-Carrasco, R. Breadmaking use of andean crops quinoa, kañiwa, kiwicha, and tarwi. Cereal Chem. 2009, 86, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, T.P.; Jupe, F.; Bemm, F.; Motley, S.T.; Sandoval, J.P.; Lanz, C.; Loudet, O.; Weigel, D.; Ecker, J.R. High contiguity Arabidopsis thaliana genome assembly with a single nanopore flow cell. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafik, S.; Rahmani, M.; Rodriguez, J.P.; Andam, S.; Ezzariai, A.; El Gharous, M.; Karboune, S.; Choukr-Allah, R.; Hirich, A. How does mechanical pearling affect quinoa nutrients and saponin contents? Plants 2021, 10, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimentarius, C. Codex Standard for Quinoa—CXS 333—2019; FAO: Roma, Italy, 2019; pp. 2–4. [Google Scholar]

| Technique Used | Seed Source/Origin | Findings | Publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not mentioned | Quinoa seed is classified as sweet if it has a foam height of 1.3 cm or less. One commercial seed-washing procedure removed about 72% of the saponin contents. The initial saponin content (6.34%) reached a level as low as 0.25–0.01% during the first half hour of washing. Approximately 96% of saponin contents are removed from quinoa seed with washing for 60 min. The widely used methods are the conventional technologies of maceration, Soxhlet, and extraction using reflux. | [25,101] |

| Hongcheon River Farming Union (Hongcheon, Korea) | Its accuracy, repeatability, and high linearity were appropriate for analyzing the saponins in quinoa with this method. The amounts of oleanolic acid, phytolaccagenic acid, and hederagenin were different among the different parts of the quinoa, including the sprouts and the fully grown quinoa plant parts. The saponin contents were highest in the quinoa seed bran and lowest in the quinoa leaves and roots. | [94] |

| Pressurized hot water extraction method (PHWE). | Andean plateau in Bolivia | There is a remarkable increase in saponin yield when the temperature exceeds 110 °C, with the highest amounts obtained at 195 °C (15.4 mg/g raw material). | [102] |

| Spectrophotometric analysis. | Provided by the INTA EEA Famailla’ | The experimental extraction kinetics of the saponin contents from the quinoa seeds were studied at different water temperatures to improve the understanding of this process. From this study, the treatment carried out at 40 °C for 6 min can be considered the optimum one with which to reach a satisfactory level of saponins for human consumption without visible seed damage. | [103] |

| Gas chromatographic procedure. | Bio-Bio (Chile) Colorado (USA) Chile Maule (Chile) | Two-season trials support the low potential of the saponin contents for some of the selected quinoa accessions; however, this was strongly determined by the specific climatic conditions: higher saponins content in the rainy year and lower in the drier one. The large differences between the climatic conditions over the two seasons of the experimental trial allowed the assessment of plant behavior under drought stress. | [104] |

| Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). | Central Chile | The experimental data were obtained through batch extraction with a ratio of quinoa to water of 1:10 under constant agitation, with a processing time between 15 and 120 min at 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 °C. It was found that the residual saponin concentration in the quinoa seeds decreased as the washing temperature increased. | [105] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Afzal, I.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Ahmed, S.; Hirich, A.; Bazile, D. Challenges and Perspectives for Integrating Quinoa into the Agri-Food System. Plants 2023, 12, 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12193361

Afzal I, Haq MZU, Ahmed S, Hirich A, Bazile D. Challenges and Perspectives for Integrating Quinoa into the Agri-Food System. Plants. 2023; 12(19):3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12193361

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfzal, Irfan, Muhammad Zia Ul Haq, Shahbaz Ahmed, Abdelaziz Hirich, and Didier Bazile. 2023. "Challenges and Perspectives for Integrating Quinoa into the Agri-Food System" Plants 12, no. 19: 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12193361

APA StyleAfzal, I., Haq, M. Z. U., Ahmed, S., Hirich, A., & Bazile, D. (2023). Challenges and Perspectives for Integrating Quinoa into the Agri-Food System. Plants, 12(19), 3361. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12193361